The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

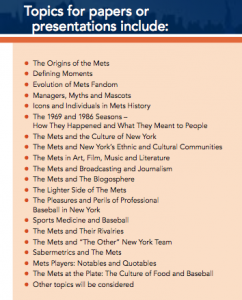

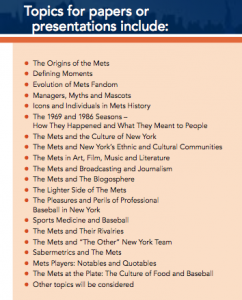

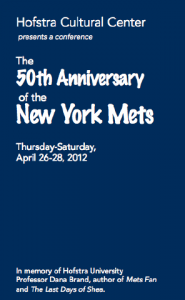

by Greg Prince on 21 November 2011 2:34 pm  Five months from now, I look forward to seeing you, listening to you and learning from you at the Hofstra Cultural Center’s conference honoring The 50th Anniversary of the New York Mets. The event that’s been a half-century in the making is coming to the Hempstead, Long Island, campus, Thursday April 26 through Saturday April 28. Five months from now, I look forward to seeing you, listening to you and learning from you at the Hofstra Cultural Center’s conference honoring The 50th Anniversary of the New York Mets. The event that’s been a half-century in the making is coming to the Hempstead, Long Island, campus, Thursday April 26 through Saturday April 28.

As many of you no doubt know, Hofstra professor Dana Brand — the author of two indispensable volumes on Mets fandom, a blogger of great warmth and passion, and a friend to so many of us — had envisioned this conference for several years and had put a ton of preliminary work into it before his passing last May. I’m happy to report the conference is proceeding in Dana’s memory and is in some very good Hofstra hands. I’m also proud to be working with the organizers on editorial and historical matters and whatever else comes along. I told Dana I’d pitch in in any way I could, and I’m glad I can keep that pledge.

Details continue to coalesce. Key takeaways for the moment are that it is indeed happening (wrapping up on the 50th anniversary of the Mets’ first home win, FYI); that you should spread the word by any means at your disposal; and that if you are so inclined, you should submit your ideas for papers and/or presentations to the folks at Hofstra by January 10. If that interests you, please get in touch with me via e-mail at faithandfear@gmail.com. You can see the working list of topics here (click on image to enlarge).

The aim of this conference is to treat the New York Mets as the cultural institution they have become across 50 endlessly Amazin’ years. Implicit in this framing is recognizing the importance of those who have made the Mets a surpassing presence in so many lives: the fans. Us, in other words. That’s what inspired Dana as much as anything, and that’s the force that will guide this conference into becoming a singular milestone commemoration. Professionals, academics and other interested parties will play a significant role in all of this, but it’s the Mets fan who is at the heart of everything Metsian. That includes the conference. Dana wouldn’t have had it any other way. So please, if you have ideas or questions, do get in touch.

And there will definitely be more to come.

by Jason Fry on 17 November 2011 12:01 pm OK, let’s get the whining out of the way first: I want to unreservedly love the new pinstripes, but they annoy me a little.

The Mets were born in the Jet Age. Fatherly Eisenhower had given way to hip, stylish JFK, soon to announce we were going to the Moon. The Mets set up shop in the Polo Grounds, squashed into a grid of urban streets and thick with the ghosts of Giants past, but that was a temporary arrangement. They were headed for Shea, then a standard bearer for futuristic ovals equally suited for football and baseball and even mop-topped British invaders. Shea was located right by the wonders of the World’s Fair, ringed by parkways fit for bearing Robert Moses’ sojourners from the suburbs in their sleek new automobiles.

We’d change our mind about how much we liked some of that new world, but that’s not the point. The point is that the uniforms should be white. The Mets’ blue and orange caps were nods to the departed Dodgers and Giants, but beyond that, the team wasn’t a sepia-tinged nostalgia exercise. They were the team of the future, and their uniforms were as bright as that future was deemed to be. Don’t be fooled by vintage uniforms on display — they’ve yellowed with age, just like old letters do. Look at old photos, or at Topps baseball cards. The Mets’ uniforms should be white, not off-white or cream or beige or ivory or buff or vanilla or what-have-you. (If Paul Lukas wants to tell me I’m wrong, I’ll listen. Otherwise, I’m not.)

But I’m done whining. Because everything else the Mets unveiled Wednesday, with the other half of Faith and Fear in attendance, was great. The glass, for once, is 95% full.

The Mets and I might argue about the proper Pantones for those pinstripes, but the most important thing is that they’re back in heavy rotation, which is baseball like it oughta be. Shorn of those trying-too-hard black drop shadows, the script Mets looks properly bright and lively, unfussy and optimistic. (I’m equally glad that they lack the racing stripe. If the Mets hadn’t won a championship wearing those things, they’d be understood as the sartorial equivalent of disfiguring “Meet the Mets” with the roll call for “Long Island, New Jersey….”)

The rest of the news was good too. The pinstripes will be joined by the home whites, also boasting additional impact thanks to the subtraction of shadows, and the solid black tops, which I don’t mind for cameos. The road uniforms shown yesterday are similarly classic: gray with blue piping and the simple, shadowless stenciled NEW YORK. On top of that, word is that those the hideous two-toned black-and-blue caps have gone down the memory hole, joining ice cream caps, Bicentennial pillboxes and Mercury Mets lids in never being discussed again. The caps will be solid blue (with orange buttons — a change I actually liked) or solid black.

All of this isn’t just encouraging or a step forward or great — it’s smart, respectful and fan-friendly.

Kudos, too, for the Mets’ 50th anniversary logo. (But wait a minute, wasn’t last year the 50th anniversary season? Whatever. I never could do math.) Not so long ago, the Mets moved into Citi Field with an inaugural-season patch that looked like a Citibank intern had slapped it together using Microsoft Paint before a smoke break. This is so much better — a respectful update of the skyline logo.

Oh, and the Mets did all this without a single shot fired at their own feet. The announcement came on the 50th anniversary of the unveiling of the original logo, the kind of anniversary that has too often has been noticed by fans instead of by the front office. And it came with another fan-friendly gesture — Banner Day is returning.

Banner Day began as New Breed samizdat and flourished as a very Metsian holiday before being sadly banished. It’s great to have it back. The Mets of recent years have often seemed so hypersensitive to the possibility of bad PR or media scoffing that they’ve ignored their own history and muzzled their own fans; resurrecting Banner Day is a welcome sign that the team wants to rebuild that connection. Here’s hoping fans respond in kind, ignoring the current dark clouds. Let’s get this established right now: It would be rude, graceless and self-destructive for fans to make Banner Day 2012 an Occupy Citi Field parade of Wilponzi sloganeering, I’m Calling It Shea revanchism and howls for Reyes revenge, should the worst come to pass.

Heck, the Mets even brought out Ike Davis as one of the uniform models — a crutch- and boot-free Ike Davis who sounded like he was ready to play two.

Could yesterday have been better? Sure, I guess — the Mets could have made the pinstripes white and the home “whites” cream, then trotted out Jose Reyes as a surprise addition as one of the models, with Greg texting me excitedly that Jose Jose Jose was holding a press release about a Madoff settlement in one hand and a new contract in the other. But by those standards you’ll always want more. When a big day is 95% of what you would have asked for, that’s pretty good. In fact, it’s better than pretty good. You might even call it amazin’, amazin’, amazin’.

by Greg Prince on 17 November 2011 6:52 am Taking a brief pause from celebrating the Mets’ welcome decision to celebrate their heritage here to wish the Met of Mets, George Thomas Seaver, a happiest of birthdays. 41 is the new 67 today. We should all wear a commemorative patch.

Seaver, it was announced yesterday amid a flood of upbeat, non-field announcements, is the lead bobblehead of the five the Mets plan to give out next year, each one commemorating a different decade in Mets history (no foolin’). Aside from that being a most understandable and appropriate choice — even if they did a Seaver bobble in 2000 and even if Casey Stengel would be an even more apt subject for the fiftieth anniversary — it’s a reminder that Franchise players can come home again. Seaver has at least three times: in 1983, when he returned to pitch six years after somebody thought he should be traded; in 1987, three years after somebody pulled the clerical boner of the decade; and in 1999, after various post-retirement snits and slights were cleared away. At last check, Tom Seaver is a Mets Ambassador and legend-on-call when he’s not back in California getting his grape on.

As David Gates sang in a song that rode high on the charts as Tom Seaver participated in his first major league Spring Training that wasn’t conducted in blue and orange, baby, goodbye doesn’t mean forever. In March 1978, Seaver was a Red and the Mets were out of the Seaver business. They promoted Craig Swan and Pat Zachry and Nino Espiñosa as the kinds of pitchers you should be excited about. Life went on that way for an overly long and terribly unpleasant interval.

Then Tommy came marching home again (hurrah! hurrah!) and it was like he was never gone…three times. The Mets could sell shirts emblazoned with 41 on them, safe in the knowledge that they weren’t taking their eye off the marketing ball. They could fire up film clips from 1969 and 1973 and not inadvertently advertise that things were indisputably better when Tom Seaver wore their 41, and not somebody else’s. The memory of Seaver as Met merged forever more with the enduring reality of Seaver as Met. Today, on his 67th birthday, you can almost forget Seaver spent nearly nine of his twenty big league seasons as not a Met.

Something in which to take long-term comfort, perhaps, in case the closest thing the Mets have to a franchise player stops being a Met himself in the coming weeks.

I’ve heard it said by fans within my chronological demographic that “I survived Tom Seaver being traded, I can survive anything.” I can identify with that sentiment, yet I also wonder why I’d want to test Jose Reyes’s potential departure against the baseline for Worst Happenstance Imaginable in the realm of Mets exits. There’s only one Seaver, but that’s hardly the issue. Reyes isn’t Seaver. But he’s close enough. He’s as Seaver as we’ve had lately (David Wright notwithstanding). The Mets of 2012 without Reyes will be close enough to the Mets of 1978 without Seaver. They’ll still be the Mets, but less so. Putting aside the reconstruction of the small-f franchise and ever present financial considerations, it will be incredibly weird having the Mets and not having Jose Reyes on them.

I was 14 when Tom Seaver was traded. I survived and all that, but I’m still stunned that it happened. I had never known a Mets team without Tom Seaver. A Mets fan who is 14 now has never known a Mets team without Jose Reyes. I won’t speak to the potential stunnage of current 14-year-olds, but I can tell you that when the Mets played a marvelous montage of 1962-2011 highlights at their press conference yesterday and topped it off with all the players we can expect to see in their 50th Anniversary season, and there was no discernible sign of Jose Reyes anywhere, I was stunned. I all but knew there wouldn’t be any Jose as soon as the video started to roll, yet it was still still stunning. As stunning as it is, to me, that Tom Seaver, 67 today, was traded when he was 32 and I was 14.

But on the bright side, should Jose wind up elsewhere, there’s quite possibly a 75th anniversary bobblehead with his name and partial likeness on it come 2037. May Gold’s Horseradish and I live so long.

by Greg Prince on 16 November 2011 3:20 pm  To be uncommonly brief about it (and trust me, I plan to be more expansive on the topic in the very near future), congratulations to the New York Mets for getting it. They get that their 50th anniversary is a big deal, and they are making a big deal out of it. You can read the official details here and visit their dedicated site here, but for bringing Banner Day down from the attic, for offering up a literal handful of decade-themed bobbleheads and for working blue in their coming golden anniversary season, this historically minded Mets fan says way to go. To be uncommonly brief about it (and trust me, I plan to be more expansive on the topic in the very near future), congratulations to the New York Mets for getting it. They get that their 50th anniversary is a big deal, and they are making a big deal out of it. You can read the official details here and visit their dedicated site here, but for bringing Banner Day down from the attic, for offering up a literal handful of decade-themed bobbleheads and for working blue in their coming golden anniversary season, this historically minded Mets fan says way to go.

by Greg Prince on 14 November 2011 8:17 am I remember in the early ’40s, back there, when I was a kid working on the city desk in the Detroit Free Press. It was Sunday, four o’clock in the morning, somebody phoned in a story, and I had no way to check it out.

It was either print the biggest story of the century and beat every paper in the city by hours — or kill it. I was a gutsy kid, so I decided to print it.

You want to know what that story was? I’ll tell you what that story was. The Japanese had just bombed…San Diego.

—Lou Grant, “WJM Tries Harder,” The Mary Tyler Moore Show

If Jose Reyes becomes a Miami Marlin, we’ll know for sure. We’ll know because multiple reliable sources will report it and we’ll know because you’ll hear me yowling in agony.

But until then, take with a pound of salt any breathless bulletins that exclusively confirm “a done deal,” considering Jose’s only just begun to shop his services — no matter what protective headgear he may don when visiting construction sites.

Caution: Falling Rumor Zone. Which doesn’t make this process and its array of unfavorable potential outcomes any less of a nightmare.

Thanks a lot, Wilpons.

by Greg Prince on 9 November 2011 5:42 am “I saw him play.”

“Yeah? What do you think?”

“He was the best. Run, hit, throw…he was the best.”

—Buck Weaver on Shoeless Joe Jackson, Eight Men Out

Listen, I’m supposed to present this award to you: Faith and Fear’s Most Valuable Met for 2011. It’s not a real award, so don’t clear space for it or anything. It’s just something I do every year to put a wrap on the season.

You won the award easy. You won it in June. Now and again it would occur to me that come November I’d have to compose an essay to make it “official,” if you will. I looked forward to it. I always look forward to doing Most Valuable Met, especially in the overall bad years, because it’s something positive to look back on.

I have to admit I’ve been waiting to present this “award” to you ever since I invented it in 2005. You were one of the “finalists” every year the first few years, but there was always someone who embodied the season just a little more. I considered it a great exercise in self-control that I didn’t give it to you in 2006. I wanted to, but Beltran had the big numbers, and since I’d been boosting him for league MVP, I thought I had to honor that.

But that was OK. It wasn’t really a thing in my mind back then. The first couple of MVMs were sort of off the cuff. I didn’t make a thing of it until 2008, really, and that one had to be Johan’s. You understand, I’m sure.

Then you disappeared for most of a year, and weren’t more than 80% yourself the next year. You weren’t really top of mind. You understand that, too, I’m sure.

Finally 2011. You owned it. You owned the heart of it. I can’t imagine your agent doesn’t have all kinds of statistics revealing just how much you accomplished this year and every year — and how much you’re likely to do in the years ahead — but I have to share what I divined anyway, courtesy of Baseball Reference.

From May 24 to July 2, you batted .413. Your OPS was 1.074. You scored 37 runs in 34 games. You collected 62 hits. You stole 13 bases. You tripled 9 times.

And you transcended your numbers. You ascended to that level where nobody wanted to miss a single thing you did on the field. For six weeks, you were the greatest show on turf. You managed to maintain that J. Pierrepont Finch grin of impetuous youth, yet there you were, unquestionably a man in full. You may have been the best Met not named Seaver or Gooden I ever saw. For one of those rare moments across a half-century in the sport, we had the best player in baseball.

Honestly, I don’t think we ever had a better position player over an extended period. I could rattle off a few names and dates, but that wouldn’t help anybody else’s case or dilute yours. Nobody was as exciting as you. Nobody started games the way you did and nobody kept them going the way you would. Nobody was a better advertisement for staying tuned and sticking to one’s seat. Whatever else your teammates were doing — and they did what they could — you were why I wanted to watch the Mets in 2011.

Who am I kidding? You were why I wanted to watch the Mets from 2003 on. You played with a division champion. You played with eight lost souls. It didn’t matter. In my soul, you were the draw for me. You hitting. You running. You not stopping. You until you were a blur…a happy and peppy and bursting with love of the game blur, blazing from home to third and then ninety feet more.

A blur…that was you and that was time, it now occurs to me. How did it get to be nine seasons so soon? How did you get to be our all-time leader in runs scored? How did you land suddenly second to indefatigable compiler Eddie Kranepool in hits? How did June 10, 2003, become more than eight years ago so fast?

This year your blur was epic. Then it receded into injury. Why that keeps happening I don’t know. I was envisioning a 2011 that was going to keep growing in stature until it was the stuff of legend. The year you broke Olerud’s record for batting average. The year you broke Lance’s record for hits. The year you made yourself inarguably indispensable to the fortunes of the franchise. You were going to create a masterpiece so dazzling that the commissioner would have been forced to invoke the “best interests of baseball” clause to keep you from going anywhere else, because how could the Mets — whatever their financial foibles — function without you?

You came back from the first hammy calamity, you groped to find your footing…and it happened again. Another injury. There went the blur. There went the fun. Your teammates had run out of gas by then and you weren’t around to fuel them anymore. So we just waited for you to return a second time, sort of like we did all through and then after 2009…a lot like we did all through and after 2004 and even 2003, come to think of it. A little like we had to do in spots during 2010.

I really wish you hadn’t missed all those games. You’d be ahead of Kranepool by now. More importantly, you’d have had no doubters in high places. You’d have been courted and signed for the long haul. You’d be the Met for life you couldn’t not be. There’d be no questions from a front office that didn’t know what it had in you when it got here. I could hear it in Alderson’s tone a year ago when they asked what he planned to do about his shortstop’s expiring contract. “Who? Him? We’ll see.”

Yeah, he saw. We all saw. We saw the upside. We were reminded of the outside — the trademark, toothsome explosion of joy you effortlessly evinced. You were still that kid from 2003 and 2005 and 2006 and 2007 before it kind of went to hell on you. Yet you were somehow more mature, too. You were 28: timeless and ageless. And, in the heart of 2011, you were as healthy as you were vibrant.

Except there’s a portrait of your hamstrings in a storage facility somewhere in Corona and those suckers got old fast. Hearing about them did, at any rate. Nobody here wanted to think about the parts of you that weren’t indestructible. We preferred your smile. Your flying dreadlocks. Your facefirst slide into whatever base came next. Your infectious clapping from the dugout. Your blur. Your June. All of that felt impervious to danger.

Your hamstrings were another story. They were a story we chose to put aside as you wrote a new lede in the final weeks of 2011. You weren’t in Olerud/One Dog territory anymore, but son of a gun, you were still the hittingest hitter in all the National League. You were leading in batting average. We all agreed to suspend our cynicism toward a statistic that proves more and more hollow the deeper one drills into it because, quite frankly, it was the neatest title any Met had ever pursued. It may not have been complex or sophisticated, but when we were growing up, it had it own baseball card and its own listing in the papers — the leaders every day, and everybody on Sunday. No Met had ever headed that listing. But you were going to.

And you did. You did it with an uncharacteristically klutzy flourish on the final day, but I’ve already pretended to forget about that. The point is you won the title. You were the National League Batting Champion of 2011. You hit .337 the year after you hit .282. You did it in less than ideal physical condition. You didn’t triple after July 21 (yet tied for the league lead with 16). You tried to steal only once between August 31 and September 22 (but still finished sixth in the N.L. with 39). Your legs…your business partners…didn’t cooperate, but you overcame.

Which brings us to the presentation of this award, usually a pleasant distraction from the gaping maw of November and the fact that the Mets tend to come up empty where real awards are concerned. Like I said, I was looking forward to this little annual ritual of mine, but honestly, it’s been difficult getting to this point. I can’t think of what you’ve done without thinking of what your next move might be, and whether the Mets will cooperate with you any more amenably than your legs did in the second half of the season. And, to be perfectly frank, I can’t swear to just how much cooperation in the form of a lucrative multiyear contract is reasonable.

If money were no object…never mind that fantasy. Money is an object, one that likely eludes the grasp of the owners of this franchise (thanks to their most infamous business partner). I don’t know how New York City became Kansas City, but it apparently has. Nobody really believes you’ll be back to defend your batting title or run out more triples or give us something we can’t take our eyes off in 2012 and beyond. I don’t really believe it anymore, though I’d be happy to be wrong very soon.

If they don’t sign you, there will be moments, perhaps lots of them, when it will make all the sense in the world, but there will be at least as many moments — unquantifiable yet emotionally tangible — when it will be the worst idea in the world. The thought of the Mets without you is why this award presentation has been difficult for me to pull off. I can’t even bring myself to inject your name into this discussion. It’s like if I put it out there, forces will align to take it away from me.

I didn’t become a Mets fan to endure indeterminate stretches of being less happy than I’ve been previously. I’ve put up with those inevitable downturns on principle; or out of loyalty; or maybe just because I have too many clothes featuring too many Mets logos to start over. But these days I’m having a tough time reconciling my diehard tendencies with the notion of the Mets plodding along without you. I don’t look forward to rooting for a Mets team that doesn’t have you. It wasn’t much fun doing it when you were on the DL, but at least then we knew you were coming back.

By the way, you can decide to take less money to stay here. That is if you like it as much in these parts and in this dead-end organization as you’ve indicated you do. I wouldn’t necessarily do it if I were in your position. I don’t plan on becoming one of those creepy fans who writes to 29 strange teams declaring he’s a free agent, but except for habit and a lifetime of devotion, I can’t think of a good, rational reason to get squarely behind this team if you’re not on it.

You, on the other hand, were the best, most rational such reason for nine seasons, especially last season. That’s why I’m going through the formality of informing you that you’re Faith and Fear’s Most Valuable Met for 2011, from when “valuable” didn’t need to be assessed with a dollar sign.

We experienced it for ourselves day after day. If we don’t experience it anymore, I am going to miss it too much for words.

FAITH AND FEAR’S PREVIOUS MOST VALUABLE METS

2005: Pedro Martinez

2006: Carlos Beltran

2007: David Wright

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Pedro Feliciano

2010: R.A. Dickey

Still to come: The Nikon Camera Player of the Year for 2011.

by Jason Fry on 3 November 2011 8:44 am For once the actual weather matched the spiritual forecast: A day after a thoroughly entertaining World Series that featured a Game 6 for the ages, the East Coast got walloped by a blast of snow, slush and mess. The mess is gone but it’s still cold, and on some essential level it will stay that way until mid-February or the beginning of March or Wednesday, April 4 or Thursday, April 5.

By the end of 2011 I was tired, and it wasn’t so bad to have the Mets go away for a little while. It had been a tiring conclusion to the season, and I think we all sense it will be a tiring off-season, full of dispiriting talk about Jose Reyes and payrolls and most likely a slow-dawning acceptance that the Mets’ salvation will need to either come from within or await a change in ownership. Yet during the league championship series I found myself wrestling with a different cross for us to bear.

I’m referring, of course, to the disfigurement of The Holy Books by horizontal baseball cards.

For the uninitiated: I have a trio of binders, long ago dubbed The Holy Books (THB) by Greg, that contain a baseball card for every Met on the all-time roster. They’re ordered by year, with a card for each player who made his Met debut: Tom Seaver is Class of ’67, Mike Piazza is Class of ’98, Jose Reyes is Class of ’03, etc. There are extra pages for the rosters of the two World Series winners, including managers, and one for the 1961 Expansion Draft. That includes the infamous Lee Walls, the only THB resident who neither played for nor managed the Mets.

If a player gets a Topps card as a Met, I use that unless it’s truly horrible — Topps was here a decade before there were Mets, so they get to be the card of record. (Though now there’s an exception to this rule. Read on.) No Mets card by Topps? Then I look for a Bisons card, a non-Topps Mets card, a Topps non-Mets card, or anything else. Topps had a baseball-card monopoly until 1981, and minor-league cards only really began in the mid-1970s, so cup-of-coffee guys from before ’75 or so are tough. Companies such as TCMA and Renata Galasso made odd sets with players from the 1960s — the likes of Jim Bethke, Bob Moorhead and Dave Eilers are immortalized through their efforts. And a card dealer named Larry Fritsch put out sets of “One Year Winners” spotlighting blink-and-you-missed-them guys such as Ted Schreiber and Joe Moock.

Then there are the legendary Lost Nine — guys who never got a regulation-sized, acceptable card from anybody. Brian Ostrosser got a 1975 minor-league card that looks like a bad Xerox. Leon Brown has a terrible 1975 minor-league card and an oversized Omaha Royals card put out as a promotional set by the police department. Tommy Moore got a 1990 Senior League card as a 42-year-old with the Bradenton Explorers. Then we have Al Schmelz, Francisco Estrada, Lute Barnes, Bob Rauch, Greg Harts and Rich Puig. They have no cards whatsoever — the oddball 1991 Nobody Beats the Wiz cards are too undersized to work. (I no longer want to talk about Schmelz, the White Whale of my Metly Ahabing.) The Lost Nine are represented in THB by DIY cards I Photoshopped and had printed on cardstock, because I am insane.

Not a horizontal in sight. During the season I scrutinize new card sets in hopes of finding a) better cards of established Mets; b) cards to stockpile for prospects who might make the Show; and most importantly c) a card for each new big-league Met. At season’s end, the new guys get added to the binders, to be studied now and then until February. When it’s time to pull old Topps cards of the spring-training invitees and start the cycle again.

Now, about those horizontals. Periodically card companies get cute and shake things up with a horizontal card to lend their sets a certain variety. I have always hated these and replaced them as quickly as possible. Yet sometimes no replacement emerges, and a horizontal sneaks into THB.

This started to bug me this year, when Topps gave Justin Turner a much-deserved update card and it turned out to be a horizontal. Turner already had a normal Mets card from Upper Deck, but I was still annoyed — and before I could stop myself I’d launched a horizontal witch hunt. Crummy horizontals for Robert Person and Carlos Baerga were simple to ditch in favor of vertical Mets cards; ditto for Topps non-Mets horizontals of Rich Rodriguez and Jim Tatum. More problematic were Pat Mahomes, Mike Remlinger, Tony Phillips, Manny Alexander and Rodney McCray, all of whom got horizontals for their lone Mets cards. On the JV front, Chris Carter and the immortal Andy Green have horizontal Buffalo Bison cards.

Out with all of them, I decided. Better Manny Alexander right side up in an Orioles uniform than sideways looking like he’s about to make an error while wearing a Mets ice-cream hat. It took me some web searching and a few PayPal transactions, but a week later the Mets horizontals were reduced to zero, and all was briefly better about the world. Except, perhaps, for having to know that you actually are the kind of person who buys three Rich Rodriguez cards and then agonizes over which one is the best.

Anyway, previous annals of the THB roll calls are here, here, here, here, here and here. And now welcome to the first class of the Alderson regime. Are they heralds of a better era, or standard bearers for the new austerity? Ask us in a few years.

Miguel Batista: A wily veteran with a largely improvised repertoire and an professorial bent, Batista is a published author whose oeuvre includes poetry, philosophy and thrillers. Unfortunately, baseball only permits one niche per team/fanbase for “intellectual player whose reading material doesn’t prominently feature pictures of naked women,” and R.A. Dickey has that slot filled. So we pretty much ignored Batista’s off-field interests. The man pitched a two-hitter on the final day of the season, but that was the day Jose Reyes won the batting title and Terry Collins flubbed his likely Mets farewell. So we pretty much ignored Batista’s superb on-field effort, too. Unfair, but sometimes life’s like that. Batista arrives in THB with a 2008 Topps card in which he is contemplative and a Mariner.

Mike Baxter: Baxter hails from not too far east of Citi Field, and attracted a big cheering section for his Mets debut. His first at-bat was a double, albeit one given a little help from Kyle Blanks’s incompetent outfield play, and sent his friends and family into near-Citi orbit. It’s a small memory from 2011, but a nice one — one that will linger even if Baxter does not. Baxter gets an oddly martial 2009 San Antonio Missions card.

Pedro Beato: Another local boy, Beato pitched well enough at times to justify his Rule 5 status but poorly enough at other times to remind you that he’d have been sent down if not for that status. Worth it as a medium-term investment, and deserves a place in our hearts for telling reporters he hated the Yankees instead of blathering about tradition or pinstripes or the quiet leadership of Derek Jeter. Series 2 Mets card.

Blaine Boyer: Former Brave got axed early in the season after a couple of not good outings. Being a journeyman middle reliever is like being a competitive skater, only you start out with a broken shoelace, indifferent judges and nobody particularly caring that the ice is thin and/or missing in spots all over the rink. Stuck, probably forever, with a 2001 Bowman card.

Taylor Buchholz: Buchholz went on the DL at the end of May with shoulder fatigue, but stayed there because he was battling depression. Not so long ago, the Mets’ reaction to Ryan Church sustaining a concussion was basically to tell him to man up; this year, faced with something that might have seemed more ephemeral, they did far better. Kudos to the Mets for understanding that depression is real and nothing to minimize or mock, and kudos to Buchholz for being forthright about what he was facing. In some small way, that will help people trying to deal with depression know they’re not alone and don’t need to feel ashamed, just as it will encourage people who still dismiss depression as weakness or malingering to think again. Here’s hoping Buchholz gets better; in one sense, the Mets already have. If you want a lighter note, well, Buchholz gets a 2009 Topps card in which he’s apparently about to get mugged by a mascot.

Tim Byrdak: Some of Sandy Alderson’s moves worked and some didn’t. This was one of the ones that did. Byrdak proved more than capable stepping into Pedro Feliciano’s role, earning himself a one-year extension, and showed signs of a personality by videobombing reporters’ stand-ups to amuse himself. 2009 Upper Deck card in which he’s an Astro pitching in front of a sea of empty seats.

Chis Capuano: One of Alderson’s two rolls of the post-injury dice at the back of the rotation, Capuano exceeded expectations, giving the Mets a mix of mostly serviceable starts. Granted, “serviceable” isn’t a particularly exuberant accolade. Lots of Capuano’s starts followed a predictable pattern: He’d look good early, then get nicked for an unlucky run or two, then crash and burn. In late August, though, he faced one over the minimum while fanning 13 Braves. Using the Bill James Game Score metric, it was the best pitching performance in the big leagues in 2011, the best Mets performance since David Cone eviscerated the Phillies at the end of 1991 and the equal of Tom Seaver in the Jimmy Qualls Game. (You probably won’t guess who’s No. 1 in club history, though he was mentioned in a recent Happy Recap.) Still, one game does not a season make. Capuano did better than might have been expected, but the idea of asking him for more in 2012 makes me cringe. Series 2 Mets card.

D.J. Carrasco: Early in the year I decided I liked D.J. Carrasco. He wore his socks high and his utilitarian, vaguely tragic face reminded me of Jesse Orosco’s. Plus he had the guts of a burglar, as I declared after he escaped one encounter with the Marlins. Subsequent outcomes suggested Carrasco in fact had the guts of a burglar who kept wearing highlighter yellow and breaking into houses while people were there. Oh, and he’s signed for another year. A middle reliever having a bad campaign isn’t the end of the world, but ouch. Carrasco got a 2011 Bisons card, which he thoroughly earned.

Brad Emaus: Named Opening Day second baseman after a frustrating spring training in which he was essentially the tallest midget, Emaus showed so little with bat or glove that Alderson sent him packing after just 14 games. It was a weirdly hasty execution, but the Mets came out OK: Daniel Murphy, Justin Turner and Ruben Tejada all played more than capably at second. A position where the Mets had next to nothing for the last several years now has a logjam of players, yet more proof that we’ll never figure out baseball. And this is probably the first time you’ve thought of Brad Emaus since May. Got a 2011 Topps Series 2 card despite being Rockies property by then.

Scott Hairston: If Emaus demonstrated impatience can be a virtue, Hairston served the more traditional role of demonstrating the opposite. He started abysmally, but finished the year as a useful bench guy and genuine pinch-hitting threat. Will probably move on for 2012, but did his job. 2011 Topps Update card.

Willie Harris: Deprived the Mets of approximately 462 late-inning comebacks while playing for the Braves and Nationals, making the addition of his glove for 2011 a no-brainer. Unaccountably, Harris then started the year showing little flair on defense, leading to an epidemic of moaning about how these things always happen to us. (But, seriously … it’s weird, isn’t it?) As with Hairston, Harris hung in there to have a pretty good second half. Could return and we’d probably welcome him back. 2011 Topps Update card.

Daniel Herrera: The principal PTBNL in K-Rod’s trade to Milwaukee, Herrera was about four feet tall, had a Muppetesque mop of hair and pulled his cap down so low that it was a week before you could verify he had eyes. And he didn’t want to be called Danny. All that was endearing; so was the fact that he pitched pretty effectively, admittedly in garbage-time conditions. 2010 Topps Heritage card on which he’s a Cincinnati Red.

Chin-Lung Hu: His early billing as a good-glove no-bat shortstop proved half-right. Some Topps Dodgers special-issue card I got God knows where.

Mike O’Connor: Former National qualified as a warm body, didn’t merit a September call-up, and filed for free agency. Will possibly catch on somewhere and elicit an “Oh yeah, I forgot about that guy…” sometime next summer. 2011 Bisons card.

Valentino Pascucci: Last seen in the final Expos game, Pascucci earned a trip back to the big leagues after being a folk hero for stats-minded fans in recent years at Buffalo. Resembled Andre the Giant’s character in The Princess Bride, with the caveat that Fezzik seemed faster. Struck a decisive blow in a late-September game in which it looked like R.A. Dickey would lose a 1-0 non-no-hitter to Cole Hamels. Fezzik’s no-doubter of a blast into the left-field seats put an end to that talk; in the replay you can see me standing and whooping in the background while my kid races (in vain) for the HR ball. Those are reasons enough to remember Big Papa fondly in the Fry house. Trivia: Was first Met to wear No. 15 after Carlos Beltran. I still think the number was reissued with shameful speed, but that’s not Pascucci’s fault. 2011 Bisons card.

Ronny Paulino: Backup catcher. Won some plaudits for keeping Mike Pelfrey semi-focused at times. Fainter praise would actually be invisible. Sorry, I really was trying, but hey, he was the backup catcher. The backup catcher is generally a wise old veteran who briefly earns raves for straightening out some spooked-horse starter, flirts with taking the starter’s job, then proves there’s a reason he’s a backup catcher and is soon replaced. Where have you gone, Todd Pratt? 2011 Topps Update card.

Jason Pridie: Decent fourth-outfielder type, capable enough as a bench player and defensive replacement. Stunned everybody with a shot most of the way up the Pepsi Porch one night in the dregs of an otherwise anonymous game. I wonder if he’ll ever do that again, or if he just hit it perfectly that one time. Either way, I bet it was fun and at odd moments for the rest of his life Pridie will remember that one and smile. 2011 Topps Update card.

Josh Satin: No, not Josh Stinson. Might have generated more excitement if he weren’t basically Daniel Murphy, a promising hitter with no position. Emily thought he desperately needed a significant other who’d convince him of the wisdom of trimming his eyebrows. His THB card is some weird Topps issue proudly noting that he’s a Single-A All-Star.

Chris Schwinden: Watching this lumpy, sweaty pitcher with awkward mechanics and indifferent stuff, it was all I could do to keep from screaming, “ISN’T IT OBVIOUS THIS GUY IS NOT A MAJOR-LEAGUER?!!!” There are so many reasons I should shut up, including the fact that I don’t look that good even by the low standards of guys who type all day and the fact that the last player I had this kind of caveman reaction to was Heath Bell. If Chris Schwinden would like to make me look stupid for the next decade, he’s welcome to do so. 2011 Bisons card.

Josh Stinson: No, not Josh Satin. Pitched pretty well before the return to the statistical mean knocked him for a loop. Given his recent arrival, both on Earth and in the big leagues, the jury should remain out for a couple of years. 2011 Bisons card.

Dale Thayer: Porny mustache deserves some kind of praise. And so: I praise your porny mustache, Dale Thayer. 2011 Bisons card.

Chris Young: Gigantic, affable Princeton grad thrived in the early going, spinning terrific games against the Pirates and Nats before holding the Phillies at bay for seven shut-out innings in Citizens Bank Park on May 1, leading to Kevin Burkhardt staring at Young’s clavicle while the pitcher smiled pleasantly and spoke into a mike above Burkhardt’s head. Unfortunately, it was Young’s last start of the year — shoulder woes wiped out the rest, and possibly his career. 2011 Topps Series 2 card.

by Greg Prince on 2 November 2011 11:53 am Welcome to the final installment of The Happiest Recap, a solid gold slate of New York Mets games culled from every schedule the Mets have ever played en route to this, their fiftieth year in baseball. We’ve created a dream season that concludes here with the “best” 162nd game in any Mets season and the “best” 163rd game in any Mets season, thus completing a schedule worthy of Bob Murphy coming back with the Happy Recap after this word from our sponsor on the WFAN Mets Radio Network.

GAME 162: October 3, 1999 — METS 2 Pirates 1

(Mets All-Time Game 162 Record: 20-18-1; Mets 1999 Record: 96-66)

The Mets held their destiny in their own hands. What a frightening thought.

Less than 24 hours earlier, the Mets’ chances of attaining their first postseason berth in eleven years was, by necessity, a collaborative effort. They needed help — not the same kind their emotionally overwrought fans needed, but a more decisive kind. They needed one of the teams playing their rivals for the National League Wild Card to come up big on their behalf. They needed either the Milwaukee Brewers or the Los Angeles Dodgers to win a game. The Brewers were taking on the Cincinnati Reds; the Dodgers were going up against the Astros. When Saturday, October 2, began, both the Reds and Dodgers led the Mets by a single game. That gap had to be trimmed by half if the Mets’ Saturday night contest versus Pittsburgh was going to mean much of anything.

One of the two Mets’ new bunch of best friends in the whole world did them the solid of the century as 1999 neared its close. The 73-86 Brewers, a National League outfit all of two years, rose up and smote the 95-65 Reds on Saturday, 10-6, making it two consecutive times that Cincinnati stumbled versus non-contending Milwaukee. The Brewers put the Reds away with seven third-inning runs, as 23-year-old rookie Kyle Peterson chalked up his fourth major league win.

The cheering in New York could be heard all the way back to Wisconsin.

Peterson’s more than serviceable 6.2 innings of work — backed by two RBIs apiece from Marquis Grissom, Jeff Cirillo, Jeromy Burnitz and Ronnie Belliard — constituted the greatest gift Milwaukee presented New York since it began shipping Miller High Life east. Though Kyle Peterson’s name never, ever comes up in any retelling of New York Mets history, his Saturday afternoon win at County Stadium stands as the most important out-of-town bulletin ever to go up on the Shea Stadium scoreboard.

There it was that Saturday night, a crisp CIN 6 MIL 10 for 36,878 to see and savor. Peterson and the Brewers had pulled the Mets to within snatching distance of Cincinnati’s now half-game Wild Card lead. While any and all help would be appreciated Sunday, it was no longer required. If the Mets could, per serious-sounding sports jargon, take care of business, they could not be stopped in their quest to extend their season. Everything they and their followers dreamed of was now within their grasp.

Welcome to invasion of the Wild Card snatchers. As long as they did their part and didn’t play like zombies, the Mets were on their way to the playoffs.

Which was the frightening part, since they were on their way to the playoffs two weeks earlier and proceeded to blow it like crazy with a seven-game losing streak that made every Mets fan a fatalist. But they righted themselves just enough — two wins in their past three games — to benefit from the moment that Cincinnati suddenly decided to cease being Red hot. Cincy had forged a six-game winning streak more or less concurrent with the Mets’ losing ways. They were in first place in the N.L. Central a few nights earlier. Everything was going their way.

And then it started turning in the other direction. The Astros passed the Reds for first. Then the Reds fell twice to the Brewers as the Mets beat the Pirates once and prepared to play them again. The hottest team in baseball went cold.

It was time for the Mets to take an ice pick to them, via Pittsburgh.

On Saturday night the Second of October, the Mets unleashed a lethal weapon upon the Pirates. His name was Rick Reed, and he pitched only the game of his life. Against the team for whom he began his major league career eleven years earlier (and for the team he beat in his 1-0 besting of Bobby Ojeda on ABC’s Monday Night Baseball), Reed propelled the Mets while his teammates scuffled to figure out Francisco Cordova. Through six scoreless innings, Reeder allowed only two hits while striking out nine Bucs. Cordova wriggled out of a bases-loaded jam in the second and kept the Mets off the board until the bottom of the sixth.

Then the Mets caught up with the opposing pitcher and gave their own all the support he’d need. Aided by two Pirate errors, the Mets scored a pair of runs, the first on Robin Ventura’s 119th run batted in of the year. Ice cold for two weeks, Ventura was now steaming toward the finish line, having homered the night before in advance of winning the game on his eleventh-inning walkoff single. Only Mike Piazza had more RBIs in any one Met season now, and that was OK, ’cause that season was 1999, and the more records the Mets set, the better.

Up 2-0, Reed resumed picking apart the team that gave up on him at the end of Spring Training 1992. The Pirates weren’t the only ones. The Royals, the Rangers and Reds all had him and dropped him. He fell into Bobby Valentine’s lap at Norfolk in 1996 and Bobby brought him to New York in 1997, the first time Reed — by then 32 — had made a team’s Opening Day roster. Soon enough he made everybody look shortsighted for passing on him as he compiled a 13-9 record with a 2.89 ERA and fabulous control for the resurgent ’97 Mets. A year later, he was a National League All-Star. A year after that, at its critical end, the game of his life continued. Rick breezed through the tops of the seventh and eighth, nursing his 2-0 lead toward the finish line.

The Mets finally made it a breathable Saturday night when they added five more runs to their line in the bottom of the eighth. Reed drove in the first two, Piazza the last two, on his 40th homer, to up his franchise-best RBI to 124. Thoroughly bolstered, Reed pitched the ninth to its logical conclusion: a leadoff single to Adrian Brown for the third Pittsburgh hit of the night, a Brown-out double play grounder courtesy of Al Martin, and Abraham Nuñez looking at the twelfth strikeout of the night.

It was a 7-0 win for Reeder and a tie in the Wild Card standings for the Mets.

“It’s pretty cool, I guess,” the master of both the Pirates and understatement said before upping the assessment. “It’s awesome. This is a chance for us to make the playoffs. I know this organization has wanted it for how many years and I know there’s a lot of guys in here that are wanting it, and I’m one of them.”

“DREAM ON!” blared the front page of Sunday’s Daily News, but not in a smart-alecky fashion. The dream that the Mets could overcome their long odds and land somewhere besides home for winter was a dream that was still on, as the sub-head explained:

“METS WIN, CAN CLINCH PLAYOFFS IN FINAL GAME TODAY”

“Right now,” Rick confirmed, “we have to win one more game.”

Reed’s prognosis was a little more on-the-money than the News’s. Yes, the Mets could clinch a playoff spot in their 162nd game of the season, their finale against the Pirates, but the end result was available to them only if the Brewers continued to serve as their wingmen. Should Milwaukee finally ease up on Cincinnati, there could be no clinch — but as long as the Mets win, there’d be a tomorrow, a 163rd game to determine the Wild Card in a head-to-head matchup at Cinergy Field in Cincinnati.

But that was a world away in the Mets’ concerns going into Sunday. They had to win right here, right now. They had to beat Pittsburgh one more time. A loss would leave their fate to others. No, that wouldn’t do. Their hand was at last on the wheel of their own destiny. It hadn’t worked for them when they spiraled into their nearly lethal seven-game losing streak and it wasn’t any help a year earlier when a five-game losing streak left them on the sidelines as the Cubs and Giants engaged in one of those so-called play-in games. Yet it was, all things considered, still their best option.

Win today, and no matter what happens, there’s another game in their immediate future.

If Cincinnati wins and Houston loses…never mind all that. Just win today. Just win today.

The last time the Mets made good on a playoff opportunity, their road to a second world title in three years ended at the hot, hot hands of Orel Hershiser, the MVP of the 1988 National League Championship Series. The Dodger righty, who had come into that postseason riding a mind-boggling streak of 59 scoreless innings, earned his first chunk of postseason hardware by snuffing out the Mets in the seventh game of a series that was supposed to be in the New York bag but almost never felt not destined to go L.A.’s way. Hershiser hadn’t been overly suffocating in his Game One and Game Three starts (both pulled out by the Mets), but his twelfth-inning appearance in Game Four, flying out Kevin McReynolds with the bases loaded to nail down a 5-4 win was as strong a signal as Mike Scioscia’s tying home run off Doc Gooden three innings earlier that this thing was turning toward the Dodgers.

Come Game Seven, it was all Hershiser all the time: five hits, two walks and not a single Met run. With two outs in the ninth, and the Dodgers ahead by six, Howard Johnson stood bone-still on a three-two pitch to end the night, the postseason and the Mets’ final shot at a World Series for more than a decade. Beatific Orel Hershiser (who found a moment to drop to a knee and thank the Lord before embracing his catcher Scioscia) had his fifth strikeout and the enmity of every Mets fan. He was Mike Scott. He was Bruce Hurst. He was worse, actually. Unlike those guys, who merely threatened to derail the 1986 Mets, Hershiser had actually ushered the Mets from the Promised Land.

It’s hard to decide what a crestfallen Mets loyalist would have decided would have been more unbelievable on the dark night of October 12, 1988: That the Mets wouldn’t make the playoffs for at least another eleven years or when the moment came to push them toward that elusive goal, the starting pitcher for the Mets would be 41-year-old Orel Hershiser, no longer a Cy Young or MVP candidate, but a most grizzled veteran (the oldest hurler in the N.L. in 1999, by two years over teammate John Franco) who had figured out how to win 13 games despite an ERA well over four.

His opponent in this very different October was a pitcher at a very different stage of his career. Kris Benson was completing his rookie campaign three years after being drafted No. 1 in the nation by the perennially high-drafting Pirates. In that same first round of 1996, other teams selected from among the likes of Braden Looper, Billy Koch, Mark Kotsay, Jake Westbrook, Travis Lee, Eric Chavez and R.A. Dickey; the Mets picked 13th and selected slugging high school outfielder Rob Stratton. The Pirates considered Benson the most attractive of all.

This rookie righty wasn’t quite at the developmental level of Tom Seaver in 1967 or Dwight Gooden in 1984, but Benson was giving the Pirates that currency of late ’90s pitching: innings. He’d thrown almost 190 of them entering Sunday, second on the staff to ace Jason Schmidt. His won-lost record (11-14) wasn’t quite as good as Hershiser’s (13-12), but his ERA was several ticks better (4.22 versus 4.66) and, besides, Hershiser was pitching for a contender. The Pirates were still a high-drafting outfit heading toward 2000. Kris had less to work with — and he had a future. He wouldn’t be 25 until November. The young stud vs. old pro storyline was irresistible.

And for what it was worth, Benson and Hershiser had crossed paths once before, on July 27, also at Shea. It was the instantly infamous Mercury Mets game, the night the Mets turned the clock forward to (if sponsor Century 21 was to be believed), 2021. The Mets and Pirates both wore absurd uniforms, though the Mets’ all-in approach (rebranding their home planet; Photoshopping Rickey Henderson’s DiamondVision photo so he’d sport three eyes) is what won the Mets a judgmental round of derision from all concerned. The still-pious Hershiser was among those who didn’t care for the gimmick. He hoped “the Man upstairs” wouldn’t be too unhappy with the vaguely demonic symbol on his cap, and he didn’t seem to be kidding.

In the middle of all that Veeckian wreckage, Kris Benson outpitched Orel Hershiser, defeating the Mets of Mercury, 5-1. If he wasn’t otherworldly, Benson’s first complete game in the majors served notice, perhaps, that he was the kind of pitcher the Mets wouldn’t want to encounter with everything on the line.

Too bad. It was October 3, and if the earthbound Mets intended to break the surly bonds of the regular season, they’d have to beat Benson and/or his bullpen. If Hershiser could summon the ghosts of 1988, all the better.

As had been the case for the first two-thirds of the first two games of this series, starting pitching eclipsed just about all hitters. Hershiser, coming off a beatdown versus the Braves (he lasted only a third-of-an-inning), wasn’t touching off any scoreless steaks in the first, as the Pirates built a run on a walk, a bunt, a steal and a Kevin Young single. But he tamped down what was left of the Pirate attack for the next four innings. Whether Benson was baffling or the Mets were extremely tight, the Mets stayed behind 1-0 until the fourth. A Young error allowed John Olerud to reach second as a leadoff runner and Darryl Hamilton drove him in to knot the score at one.

Benson and Hershiser engaged in their battle for the ages, so to speak, until the sixth when a one-out Martin double compelled Valentine to remove Orel for Dennis Cook. Hershiser may not have quite rekindled his devilish magic from 1988, but two hits and two walks over 5⅓ innings was about as perfect as Mets fans could hope for from the oldest pitcher in the league. Cook and Pat Mahomes combined to extricate the Mets from any problems in the top of the sixth.

In the bottom of the inning, the Mets challenged Benson. Ventura and Hamilton singled, and Rey Ordoñez walked to load the bases with two out. The best pinch-hitter Valentine had was a Matt Franco, and there was no better juncture to use him, with the pitcher’s spot up next. Alas, there was no worse result than when Franco popped foul to third baseman Aramis Ramirez.

The top of the seventh belonged to the Mets’ fourth pitcher of the day, Turk Wendell, who set down the Pirates in order. Benson was still on in the seventh when Rickey Henderson led off as Rickey Henderson had been doing regularly since 1979: by getting on base. Rickey lined a single to right, but in a concession to his 40-year-old calves (one of which was cramping), he was pulled for rookie pinch-runner Melvin Mora. Mora, whose favorite player during his Venezuelan childhood was the mercurial Henderson, had nowhere to run, however, as Benson flied out Edgardo Alfonzo and Olerud before striking out Piazza with what became his 120th and final pitch of the day.

Kris Benson had outlasted Orel Hershiser, as 24-year-olds will do to 41-year-olds, but he only pitched him to a draw: each man allowed one run and each man was leaving his business to be finished by others. Wendell remained the Mets’ pitcher in the eighth and he stayed tough, retiring the Bucs in order again. Jason Christiansen replaced Benson, and it’s hard to say if the Mets noticed the difference. They made two quick outs, drew some hope from a Benny Agbayani pinch-walk but then watched Ordoñez ground to first to end the inning.

On to the ninth, with the Mets and Pirates still tied, 1-1. In Houston, the Astros were in the midst of clinching their division, thus altogether removing themselves from the National League Wild Card equation. In Milwaukee, nothing was doing in any sense of the word. Rain fell on County Stadium. On a less contentious final Sunday afternoon of the schedule, the Brewers and Reds would shake hands and get a leg up on their hunting and fishing. But the Brewers would have to wait around because the game was going to mean everything to the Reds, no matter what the Mets did.

What the Mets were doing in the interim was continuing to hold off the Pirates, though that, like the entirety of their 1999 season, insisted on getting interesting. Turk retired his seventh and eighth consecutive batters before succumbing to Young, who lined a single to left. Valentine opted for his hardest thrower, Armando Benitez. As Armando got used to the mound, Young stole second. The batter, Warren Morris, was intentionally walked to put two on with two out. With a shot at giving the Pirates a lead that might have devastated the Mets’ post-October 3 plans, Ramirez struck out on four pitches.

Gene Lamont brought in Greg Hansell to pitch. Bobby Valentine sent up a wishful thought to hit. His name was Bobby Bonilla, having, all things considered, one of the worst seasons any Met had ever had. The .161 batting average and the four months since his last home run was the least of it. Bonilla was a Grade-D distraction all year long, pouting, sulking, bickering and in no way contributing to a team that was tied in the ninth inning of the 162nd game of a season in which it was tied for a playoff spot. Had Bonilla produced just a little more positively, the Mets might already be in the playoffs. But Bonilla was a net negative in 1999.

Yet there he was, the Mets’ first hope of potentially their last inning. He was once a superstar, the biggest name in the free agent winter of 1991, when the Mets, desperate to make a splash, threw a ton of money at him and he declared how much he had always wanted to be a Met. That was a long time ago. Bonilla had since wound his way through Baltimore, Florida and Los Angeles. He was a Met again only because the current general manager wanted to get rid of one onerous contract (Mel Rojas’s), so he accepted a different one. Bonilla plainly wasn’t worth it.

Wasn’t it about time he was? That was the sense 50,111 at Shea maintained as they did a veritable restart on the hard drives of their memories. Clearing away everything they knew about Bobby Bonilla’s futile 1999, they stood as one and applauded their former two-time All-Star in the hopes that he could take one big swing and create a game-ending scene that would make Kirk Gibson scoff in disbelief. Bobby Bo had authored 277 home runs since 1986. How about one more right now?

It was a great idea, but no. Bobby let ’er rip, but all that occurred was a grounder to first for the first out of the ninth. Most of Shea applauded the effort. That Bonilla could elicit any semblance of good feeling was pretty unbelievable by itself.

Maybe those good vibes were the kickstart karma required to push the Mets toward life after 162 games. Next thing Shea saw, Mora, the pinch-runner who stayed in the game and shifted at Valentine’s will from left to right and back to left, singled to right for the fifth hit of his major league career. Alfonzo, the club pro, also singled to right, sending Mora scooting to third. Olerud, whom nobody called the silent assassin but they could have, had to be intentionally walked here. Even if it meant Mike Piazza and his club record 124 RBIs were up next.

Lamont did what he had to do. He had Hansell pass Olerud and he replaced Hansell with Brad Clontz, a Met for barely more than a minute in 1998, but nevertheless a former Met who looked at his ex-mates on the precipice of playoff ascension and “wanted to beat them bad”. Chances are most in the finger-crossing, rally-capping crowd had probably forgotten him if they were ever aware of him at all. But one person in blue and orange was plenty Clontz-conscious.

“I played with him,” Mora reflected upon noticing his Tide teammate from the season before was warming up, “and I knew he would throw the ball at the dirt. I was thinking wild pitch because I knew he wasn’t going to throw nothing around the plate to Piazza.”

Ladies and gentlemen, meet the prophet Melvin Mora. Oh, here he comes now, as described by Gary Cohen:

Well, the hope for the Pirates is they get Piazza to hit a ground ball at an infielder who would be able to turn a double play and get through the inning.

The infield will play halfway. The outfield will play only as deep as they can throw, a fly ball will win the game, with Mora standing at third base.

Alfonzo at second, Olerud at first.

Piazza stands in, oh-for-four on the afternoon.

Clontz is ready to go, pitching off the stretch. DEALS to Piazza. Low and outside, IT GETS AWAY! ONTO THE SCREEN!

MORA SCORES! THE METS WIN IT! THE METS WIN IT!

Mora is MOBBED by his teammates as he crosses home plate! Brad Clontz BOUNCED the first pitch up onto the SCREEN! Melvin Mora scores the winning RUN! The Mets win in game number one-hundred sixty-TWO, and the Mets will play again in Nineteen Ninety-NINE!

The Mets win it their final turn at bat, they win it two to one on a WILD PITCH by BRAD CLONTZ, and they’re going crazy here at Shea!

All the Mets out on the field, exchanging HIGH-FIVES and hugs. The Mets have played a hundred and sixty-two GAMES, they now lead the Wild Card by a half-a-game, waiting on CINCINNATI, scheduled to play in Milwaukee, waiting for the raindrops to cease, and it may be a long night before we know where the Mets are going, Bob, but now we know they’re goin’ somewhere.

Indeed, as Gary told Bob Murphy, the journey of the 1999 Mets was continuing. Once the rain stopped, the Reds would play. No matter what they did, so would the Mets — either against Cincinnati Monday to determine the identity of the National League Wild Card night or in Arizona Tuesday night to take on the N.L. West champion Diamondbacks in the first game of the National League Division Series.

“When I touched home plate,” Mora related, “I just thought, ‘We’re going to be flying somewhere, but we’re gonna fly.’”

The Mets’ fate remained in their own hands. What an exhilarating thought.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On October 5, 1986, there was numerical beauty in everything the Mets touched. They defeated the Pirates, 9-0, at Shea to complete the regular season at 108-54: two wins for every loss, so much neater than, say, 107-55. The Mets had already surpassed the franchise record for most victories in one year when they beat the Bucs, 3-1, in Pittsburgh on September 26 to move their mark to 101-53. With 1969’s standard of 100-62 relegated to second place, everything else prior to the playoffs was gravy.

But what gravy. The Mets surged toward their NLCS date with Houston in 1986 style by winning their final five, nine of their last ten and 15 of 19 overall, dating back to September 16 in St. Louis, when they clinched a tie for the foregone conclusion that the next night became their third division title.

Not only was 108-54 imposing (no National League team had won as many since the 1975 Reds; no National League team had won more since the 1909 Pirates), but the 9-0 score by which they achieved their 108th triumph was appropriate. 9-0 is the score by which a forfeit is declared, and the entire senior circuit seemed to give up as soon as the Mets appeared in the other dugout 108 times in 1986. There was also a tinge of satisfaction that it was the Pirates going down to defeat versus the Mets for the 17th time in 18 games in ’86. The Pirates were a lousy team, going 64-98, but their similar cellar-dwelling in 1985 (57-104) hadn’t stopped them from beating the Mets eight of eighteen and putting a major crimp in that year’s Flushing postseason plans.

Not a problem in 1986, a year unlike any other for the Mets. First-year Pirate skipper Jim Leyland was actually mindful that the Mets were due at the Astrodome three days hence and removed his starter, Hipolito Peña, in the second inning because he didn’t like how high and tight the late-season callup was coming in on Mets batters. His last pitch hit Keith Hernandez in the back. Nudged to recall his sportsmanlike pitching change a quarter-century later by the Times’s George Vecsey, Leyland reasoned, “Shoot, they were going to Houston. I didn’t want to see them get hurt.”

The Mets didn’t go out of their way to run up the score on the poor Pirates, it’s just what they did in 1986. More numerical beauty could be found in how the Mets put up their nine runs: A three-run homer from Gary Carter in the first, a two-run homer from Ray Knight in the fourth, a grand slam off the mighty bat of Darryl Strawberry in the fifth. Straw’s slam shoved his RBI total over 90 for the year, while Carter’s blast tied him with Rusty Staub for most runs batted in by any Met, 105, in one season.

The pitching also seemed to follow a script. Ron Darling went five to qualify for one of the season’s easiest victories (his 15th) and Sid Fernandez worked the final four to tune up for the playoffs. In doing so, he earned his first (and only) major league save. With his final pitch, to Pirate third baseman Bobby Bonilla, Sid added one more exclamation point: his 200th strikeout, tying Dwight Gooden for the staff lead. And if Sid should be needed in relief in the upcoming postseason, the experience would come in handy.

The home crowd — which had pushed paid attendance for the year to a New York City record 2,767,601 — was overjoyed to finalize an immortal regular season at 108-54, even if its attention was focused on what awaited in Texas. A chant of “We want Houston!” went up around Shea, mirroring the Mets’ feelings exactly. But before they took off in search of the eight wins they’d need to make 1986 as indelible as it possibly could be, they stood in their dugout, watched a highlight montage on DiamondVision (set to Willie Nelson’s recording of “Wind Benath My Wings”) and tossed their caps to the nearby fans. Then blue and orange balloons were released over Queens, hinting at just how high the Mets were planning on soaring before their 1986 was over.

GAME 163: October 4, 1999 — Mets 5 REDS 0

(Mets All-Time Game 163 Record: 2-3; Mets 1999 Record: 97-66)

Cincinnati on a Monday night. No town ever looked so good to the New York Mets.

The Mets knew they were destined to play more baseball after Melvin Mora came duckwalking across home plate on Brad Clontz’s bases-loaded, ninth-inning wild pitch on Sunday. The 2-1 victory against Pittsburgh guaranteed them the National League Wild Card if the Reds lost in rainy Milwaukee or a one-game, regular-season playoff — also referred to as a “play-in” — if the Reds won.

Well, the Reds won. Their Sunday afternoon game became a Sunday night game in deference to the Wisconsin weather and the urgency of the outcome. Though attendance was listed as 55,992, based on tickets sold for what was supposed to be County Stadium’s final baseball game (a fatal construction accident at the adjacent Miller Park site in July extended the old ballpark’s tenure into 2000), the five-hour, forty-seven minute rain delay ensured this one would be played in front of friends and family…and then only really close friends and immediate family. Nevertheless, the ghostly gathering saw National League Player of the Month Greg Vaughn pop his 45th homer of the season and Pete Harnisch, a Met from 1995 to 1997 (and one of several veterans who had clashed with Bobby Valentine), pitch Cincinnati to a 7-1 win, raising their record to 96-66, same as the Mets.

The Reds salvaged their season same as the Mets. They would meet in the seventh specially arranged tiebreaker in National League history, the third in the divisional era and the second in two years to determine the N.L. Wild Card. The 1998 play-in game was one the Mets had dearly wanted a piece of, but their five-game losing streak shut them out and, if so inclined, they had to sit home and watch Steve Trachsel lead the Cubs past the Giants to grab the last remaining playoff spot in Game 163 — the same playoff spot for which the Mets led the pack after 157 games and sat in a three-way tie for after 160 games.

It was a brutal collapse in 1998, which is why the facsimile thereof in 1999 — the seven consecutive losses to the Braves and Phillies with less than two weeks to go — haunted Mets fans so. Their team had come surprisingly close to the Wild Card in 1997, finishing four games behind the one-year wonder Marlins. Enhanced with Mike Piazza in May of ’98, they seemed to have a clear shot at going further, but it boomeranged on them late. In 1999, the Mets were as close to being a powerhouse as any team not named the Braves or the Yankees, particularly once an earlier losing streak (eight in a row in late May and early June) was overcome.

The Mets played 65-30 ball in the heart of the season. They seemed perfectly capable of overtaking Atlanta in September, what with their airtight defensive infield — hailed on the cover of Sports Illustrated as potentially the best ever; their three hundred-RBI men (Piazza, Robin Ventura and Edgardo Alfonzo); their generally reliable and uncommonly deep bullpen; their pair of base-stealing specialists (franchise record-setter Roger Cedeño swiped 66, the old master Rickey Henderson pilfered 37) and a intangible sense, per the refrain of the Doors classic “L.A. Woman” that became their rallying cry, that their Mojo was Risin’.

Then it fell flat. The Braves buried their divisional aspirations and the Reds rolled past them. But on the final weekend, the tables turned, resulting in the current tie. It was thrilling to any Met partisan that they had gotten this far, but after the heartfelt postgame love-in at Shea that followed Mora’s scamper home, when the cheers and the hugs and the music played cathartically on, the fans and players alike arrived at a singular conclusion: the Mets hadn’t actually won anything yet.

“It felt a little weird,” admitted Al Leiter.

Leiter would be the one charged with making the Mets’ next celebration immediate and a little more traditional. He was Valentine’s starting pitcher for the only non-incidental Game 163 the Mets had ever been asked to play. It was framed as both a clinching game and an elimination game. Leiter would figure to have the biggest say among all Mets as to which one it would go into the books as.

But he’d have help, starting with the leadoff batter to end all leadoff batter discussions. Rickey Henderson had long ago established himself as the best the game had ever seen. At age 40, he was still leading — leading Mets regulars in batting average, leading Cedeño to become a better base stealer, now leading off the one-game playoff with a tone-setting single versus Cincy starter Steve Parris. In a matter of moments, he’d lead Alfonzo around the bases as Fonzie quieted 54,621 Red heads by belting his 27th home run of the season. The Mets struck first and held a 2-0 lead.

Leiter took the ball and ran with it like nobody had at Cincinnati’s stadium since Ickey Woods was in his shuffling glory. Pokey Reese led off with a walk but stayed glued to first as Al got Barry Larkin and Sean Casey on flies and Vaughn looking at a three-two pitch for the third out. Jeffrey Hammonds reached Leiter for a one-out single in the second, but Eddie Taubensee and Aaron Boone stranded him. In the top of the third, a two-out walk to Alfonzo and a double from John Olerud moved Jack McKeon to intentionally walk Piazza. The Reds’ skipper lifted Parris in favor of Denny Neagle, but Neagle did him no favors when he walked Ventura, giving the third baseman his 120th RBI of the season and Leiter a 3-0 lead with which to work.

Al was functioning on all cylinders: one walk but no hits in the home third, a perfect fourth. He sat down, and Henderson, who remained reserved on Sunday, since to his mind all the win over the Pirates guaranteed the Mets was a chance, momentarily replaced Leiter at center stage of the Mets’ crusade. Rickey made the most of his team’s chances by leading off and belting his twelfth homer of the year, the team’s 181st (only the 1987 squad had slugged more).

“This is my time of year,” Henderson declared. “This is Rickey time. And with Henderson Daylight Time in full effect, the Mets were up by four, as Leiter remained in his groove, retiring the Reds in order in the fifth.

One more Mets run was on tap, Alfonzo doubling home Rey Ordoñez from second in the sixth for his 108th run batted in. It was now 5-0. By the end of seven, it was still 5-0, with Leiter having set down 13 consecutive batters. That string was interrupted by a Taubensee walk, but Boone grounded into a double play directly thereafter. When pinch-hitter Mark Lewis grounded to Ordoñez for the final out of the eighth, Al Leiter, self-proclaimed lifelong Mets fan from Toms River, New Jersey, was pitching a one-hitter and had his team three outs from the postseason.

Lifelong Mets fans all over the Metropolitan Area braced for what seemed almost impossible a little more than 72 hours earlier, when the Mets were two out with three to play. They played their three, they won their three and they earned this game, their fourth. By winning it — by not blowing it — the lingering bitterness from 1998 would be washed away. The decade of the ’90s, most of it mired in sub-mediocrity, post-Buddy Harrelson, pre-Bobby V, would be validated as worthwhile. Connecticut native Valentine, who had never been to the playoffs in ten seasons as a player or in any of the eight years he managed the Texas Rangers, would finally set foot inside the business end of October (forty-eight years and one day after his future father-in-law, Ralph Branca, legendarily stepped out of it).

John Franco, who used to clip coupons from the side of Dairylea milk cartons in Bensonhurst so he could sit in the upper deck at Shea, would be a postseason participant for the first time in a major league career that wound back to 1984. Another Brooklynite who grew up rooting for the Mets, Shawon Dunston, was traded to the team in July and not only saw this game as punching his first playoff ticket since 1989, but looked at the lefty Leiter in Game 163 and had one overarching thought he was willing to express aloud later: “Jerry Koosman! Jerry Koosman! Jerry Koosman!” Like Kooz in the ’73 NLCS, Al was a super southpaw dominating the Reds when it mattered most.

This stuff stayed with you if you were a Mets fan. Of course everything stayed with you if you were a Mets fan. Too often what stuck most was the disappointment: stacks of it. But when you got something good in your sights…something as good as you had in your selective rearview mirror…it was eyes on the prize all the way. That’s why the next three outs mattered so Amazin’ly much.

That’s why yet one more Metophile born in Brooklyn, in the first Met calendar year of 1962 (a few months before Dunston first saw light in the same borough in 1963), would eventually devote an entire chapter to the 1999 stretch drive in a memoir that tracked the highs and lows of a life spent intertwined with the baseball team he loved for better or worse. It was that fan/author’s favorite Met span ever, the climax to his favorite Met season ever, and he’d seen ’em all since 1969.

“After two oxygen-deprived weeks and six anxiety-riddled months,” he wrote, “the Mets were finally, finally, finally going to do what they didn’t do the year before, what they didn’t do for a decade before that.

“They were going to make the playoffs.”

Al Leiter threw 110 pitches through eight innings. He hadn’t pitched a complete game all year. But this one was his to take to the 27th out unless there was severe trouble. He hit a bit of bump to start the ninth, as Reese tagged him for a leadoff double. Pokey took third on Larkin’s groundout to short. Casey then struck out. With one out to go, Leiter walked Vaughn. That brought up Dmitri Young, one way or another Al’s last batter. He got ahead of Young with strike one and then threw his 135th pitch of the night.

Enter, as he had been doing since 1962, Bob Murphy:

“Here’s the pitch…swung, lined hard, CAUGHT! The game is over! The Mets win it! They’re on their way to Arizona! A wicked line drive hit by Dmitri Young, caught by Edgardo Alfonzo, the game is over, the Mets have won the Wild Card in the National League.”