The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

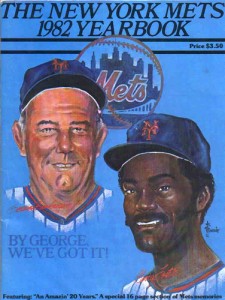

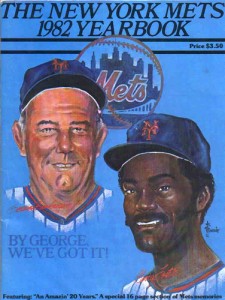

by Greg Prince on 1 December 2010 12:50 pm “Operator, please connect me with 1982,” Randy Travis yodeled on a country hit in 1986. “I need to make apologies for what I didn’t do.” I think it’s fair to say Randy Travis wasn’t a Mets fan, for in 1986, nobody wanted to make a call to the season that crumbled so definitively four years earlier.

But maybe Randy was just channeling the spirit of seasons gone by or believed the Mets — en route to 108 wins and then some — might agree to make amends for wasting our time and sapping our goodwill in 1982 with a forlorn manager, a depleted slugger and a hopelessly downward trajectory. The 1982 Mets looked like comers for two months, cresting at 27-21 (second place, 3½ behind the Cardinals), and then fell with velocity that would have made Pete Falcone envious, all way to 65-97 (sixth place, 27 games behind the Cardinals). But maybe Randy was just channeling the spirit of seasons gone by or believed the Mets — en route to 108 wins and then some — might agree to make amends for wasting our time and sapping our goodwill in 1982 with a forlorn manager, a depleted slugger and a hopelessly downward trajectory. The 1982 Mets looked like comers for two months, cresting at 27-21 (second place, 3½ behind the Cardinals), and then fell with velocity that would have made Pete Falcone envious, all way to 65-97 (sixth place, 27 games behind the Cardinals).

Let’s hope that when SNY debuts Mets Yearbook: 1982 Thursday night at 7:30, we learn the propagandists of 28 years ago were positively Travisesque in conjuring instant nostalgia for what I recall as one of the five most depressing Met seasons through which I’ve ever persevered. 1982 was the year I finally understood that the rebuilding program on which I pinned my hopes from 1977 through 1981 was at best unsuccessful and at worst a fraud. George Bamberger didn’t help. George Foster didn’t help. George Washington couldn’t have helped.

I cannot tell a lie: By George, we sucked.

Operator, I might have implored the cosmic baseball switchboard had I reached out to it in 1982, can you at least connect me with 1984? I’ve been trying to dial a winning season forever, and I just keep getting put on hold.

Image courtesy of “Mario Mendoza…HOF lock” at Baseball-Fever.

by Greg Prince on 29 November 2010 1:27 pm Some players talk a good game. Only one in recent memory, however, has shown a knack for articulating an extraordinary postgame.

R.A. Dickey is Faith and Fear in Flushing’s Most Valuable Met for 2010. He earned consideration through his pitching. He clinched the award the minute he cleared his throat.

The knuckleballer nobody saw coming saved the Mets’ season twice. First, he arrived with little fanfare from the scrap heap, via Buffalo, and sealed shut a gaping hole in the starting rotation. Then, after every outing, he casually opened his mouth and explained his thinking.

There are times I swear I would want to buy a ticket to Citi Field just to watch R.A. Dickey think. But I’d be sure to record the game just to make certain I didn’t miss anything he said afterwards.

You need an R.A. Dickey in a year like 2010 for several reasons. First and foremost, you need his numbers every bit as much as his words:

• The 19 quality starts in 26 attempts;

• The National League’s seventh-best earned run average of 2.84;

• The 3.4 WAR that bettered that of all his teammates, save for Angel Pagan, Johan Santana and David Wright;

• The 1.187 WHIP that was the best compiled by any Met righthanded starter since Orlando Hernandez in 2007;

• And the signature 1-0 one-hitter versus Cole Hamels (who recorded the lone safety) and Philadelphia on August 13, achieved in the Mets’ first dual complete nine-inning game since 2005 — and the first in which a Met had prevailed since Shawn Estes bested Glendon Rusch and the Brewers (also a one-hitter, also by a 1-0 score) in 2002.

Second, you can always use the element of surprise. Three healthy Johan Santanas and a couple of unspoiled Dwight Goodens may be ideal but there’s something exhilarating about receiving unexpected contributions from a starting pitcher who wasn’t penciled in for anything by anybody.

No Mets fan who lived through the travails of 1987 wasn’t uplifted to the point of levitated by sidewinder Terry Leach. Leach was a bullpen afterthought when that season commenced. He was its savior when things got hot: 12 midseason Leach starts, 10 midseason Mets wins.

A decade later, journeyman-epitome Rick Reed, tainted in the judgment of some for his participation in 1995 Spring Training replacement games with the Reds, shook off his overstated association with one strike and proceeded to regularly throw strike one. By the end of 1997, Reeder was known for his sub-3.00 ERA and his going, on average, roughly 6.2 innings between bases on balls.

But Leach had been around the Mets on and off since 1981. And Reed, though labor-relations infamy may have washed him out of the bigs for a spell, was at least a vaguely familiar sight, having pitched for the Mets’ then-archrivals, the Pirates, from 1988 to 1991 (including a 1-0 gem in his big league debut versus Bobby Ojeda). R.A. Dickey was almost nobody to the average Mets fan. There was one brief starting encounter, in 2008, an Interleague matchup between those nonfoes, the Mets and Mariners. Dickey threw seven splendid shutout innings, but from a parochial standpoint, the story was Oliver Perez getting lit up early and often en route to an 11-0 Seattle thrashing.

Two years later, when Perez needed replacing and Dickey was the designated substitute, we still didn’t know all that much about R.A. beyond he had a knuckleball; he didn’t have an ulnar collateral ligament, which is what made his mastery of the knuckler a must; and he didn’t stick around Spring Training very long before being assigned to minor league camp on March 15, three weeks before Opening Day. He next appeared on our radar in late April when he tossed a one-hitter for the Triple-A Bisons. Not just any one-hitter, either: He surrendered a leadoff single to Durham’s Fernando Perez and was then perfect the rest of the way. He faced 27 more Bulls and tamed every one of them.

It was his game that raised eyebrows and antennae among the keenest of Met-watchers — “That was the most dominating performance I’ve ever seen,” Bison manager Ken Oberkfell told the Buffalo News — but what we really should have been scouting were Dickey’s quotes afterwards.

“Life is not without that sense of irony,” the almost perfect pitcher elaborated to News reporter Mike Harrington. “To not have that ligament as a conventional pitcher really allowed me to be resilient. it’s that much more as a knuckleballer because I’m operating out there at 75 percent. If I’m at 100 percent, I’m going to be throwing the ball all over the place. I pick my times to really try to hump it up and throw a really filthy, hard nasty one. The rest of the time, I just want to feel like I’m playing catch with it, taking spin off the baseball and manipulate the baseball like I want to do.”

Which brings us to third reason why R.A. Dickey is Most Valuable, especially in 2010.

Read that quote again. Look at the phrases the winning pitcher brought to bear: “sense of irony”; “conventional pitcher”; “resilient”; “hump it up and throw a really filthy, hard nasty one”; “manipulate”. Dickey showed as much control of the language as he did the baseball that night in Buffalo, and demonstrated a repertoire of English that transcended any notion of him as a one-trick pitcher of complete sentences.

Has anybody else mixed a philosophical musing about life with pointed jockspeak like that? Anybody else sound as comfortable blending SAT prep with humping it up? Anybody?

I’ve never heard another player talk like R.A. Dickey. I’ve heard players talk more than R.A. Dickey, and I’ve heard players talk louder than R.A. Dickey and I’ve been impressed listening to any number of Mets over the years address their craft, but R.A. Dickey on the subject of anything he was asked about in 2010 — the subject didn’t have to be R.A. Dickey — was spellbinding. The pitching, from his Met debut on May 19 to his relief cameo on October 2, was generally sublime (which is why we paid attention to what he was saying in the first place). But the reflecting…that’s what proved truly award-worthy in our eyes and to our ears.

The Mets humped it up for spells in the first half of 2010, but by the time their West Coast wanderings were over in late July, so was their season. We were left with a bunch of not unlikable earnest guys haplessly attempting to reason away the latest hard nasty slump. Combine that with the standard quota of bad-apple incidents and the usual contretemps that surround this team, and we as hardcore, hang-on-every pitch/syllable fans, needed something to look forward to and feel good about.

As things developed, our icon became someone who would likely never end sentences with prepositions like “to” or “about”.

R.A. Dickey, we learned as the year went along, did not major in pitching all his life. He studied English at the University of Tennessee and took it very seriously, as was conveyed in one enchanting profile after another. Writers covering the Mets seemed to love covering R.A. Dickey. I once read that the New York “literati” of the 1960s were enamored of the Dallas Cowboys’ wide receiver Peter Gent because he struck them as a kindred spirit, an inference proven out by the publication of Gent’s football novel North Dallas Forty in 1973.

Dickey became this season’s Gent — our most well-spoken gent. As Jeff Roberts put it in the Record after another R.A. “W” in September, “Dickey, 35, looks more like an English professor than a major leaguer. He is working toward a degree in literature after studying English at the University of Tennessee before getting drafted in 1996.” There was also something in Roberts’ story (and several others) about the rare find in Dickey’s locker, items no other Met or baseball player apparently exhibited:

The small library sits on the top shelf of R.A. Dickey’s locker, nine books neatly lined up by size.

There’s a dictionary, a thesaurus, Life of Pi and A Year With C.S. Lewis.

Not just books, but literature having nothing to do with sports. Books aren’t exactly a common sight in the Mets’ clubhouse. Just as Dickey’s story isn’t exactly typical for most major league pitchers.

The description was eventually followed, much as ligament follows collateral follows ulnar, by one of those priceless, self-aware R.A. Dickey quotes:

“My journey has been such that I cannot take anything for granted,” Dickey said in his Tennessee accent. “That’s my story. Other guys have a different story, but my story is that I need to live in the moment as much as possible and work on living the next five minutes as well.”

I can’t blame Roberts or any of the other writers covering the Mets for going to the Dickey well at the drop of a knuckleball. They work with the language, and Dickey clearly respects the language. He reads the language. He speaks the language with grace and style — and he indeed possesses the most charming of accents.

If my job was to interview Mets, I, too, would seek out R.A. Dickey ever chance I got. In fact, when asked by the Mets communications folks on Blogger Night II if there was any Met in particular with whom I’d like five minutes, I requested an audience with R.A. Dickey. (Alas, he was unavailable, though Chris Carter did nicely, per his particular talent, in a pinch.)

We’ve already printed some statistics relevant to Dickey’s fine pitching. What would be more appropriate, considering what it is we really cherish about this guy, is to go to his greatest hits…each of them of the spoken-word variety. Read on and ask yourself if you’ve ever heard any Met — or any athlete — consistently express himself so gloriously.

For that matter, how many people, whatever their calling, speak this well?

• After his first win, an 8-0 triumph over the Phillies on May 25: “I feel like I’m 27 in knuckleball years because I started throwing it in ’05. It’s been a nice journey for me with this pitch.”

• After his second win, a 10-4 decision over the Brewers on May 30: “Before, if I had a poor knuckleball, I really would desert it. With who I am now as a pitcher, I don’t desert it. I think with the pitch that I throw, I probably have to prove myself more than most, because people want to see that it’s a trustworthy pitch.”

• After his third win, 4-3 over the Marlins on June 4: “There are little mechanical nuances that you have to really be able to feel. It’s a lot like a golf swing. It has been an evolution, and it’s slowly getting better and better. I don’t ever feel like I’m entitled to anything. That sense of entitlement will really get you in trouble. So I just try to stay humble and do the work I need to do.”

• After his fourth win, when he beat the Orioles 5-1 on June 11, specifically addressing the impact of his starting first games of series and potentially disturbing the opposition with his unusual pitch: “I don’t know. I think, if anything, it will screw them up. I surely don’t think it will help them for the next two days. If that’s the hypothesis, now we have a series to see if it works — to prove it out.”

• After getting off to a 5-0 start by defeating the Indians 6-4 on June 17 — and downplaying his personal achievement: “I hate giving you the SportsCenter answer, but I’m much more interested in how we fare collectively. But it’s nice. It’s better than starting 0-5.”

• On his traveling with a catcher’s mitt designed specially for handling the vagaries of the knuckler: “I feel a little dorky, like a field goal kicker carrying around a tee. This glove has a personality of its own. It will be broken in when it’s ready.”

• After going eight innings in a 5-0 win over the Tigers on June 23 and raising his record to 6-0 — regarding Jerry Manuel’s confidence in him: “I don’t pitch for other people, I pitch for me. It’s what I enjoy doing. I’m passionate about it and I have been fortunate to have been given the gift to do it. So I appreciate Jerry’s encouragement, but I don’t necessarily pitch for his approval.”

• On the unexpected nature of his success: “It doesn’t feel surreal. I feel like this is something I’ve been capable of doing. I felt like if I put in the hard work and committed to the journey, eventually it was going to yield some fruit. I’m excited it yielded this ripe a fruit. But it doesn’t feel like a dream.”

• After being undermined by his defense in his first loss, an eventual 10-3 pasting by the Marlins in San Juan on June 28: “Sometimes that’s the way the ball bounces — literally.”

• After outpitching Stephen Strasburg in a game the Mets’ bullpen eventually gave up 6-5 to the Nationals on July 3: “It was kind of anticlimactic. Not that he’s not very good. He’s good. But I felt like the ball was going to be invisible. I actually saw it.”

• On the impact the winds of AT&T Park may have had on his knuckleball: “Inconsequential.”

• After arguing to no avail with Manuel when the manager came to the mound to remove him when it appeared he injured himself while engaged in a pitchers’ duel the Mets would go on to lose to the Dodgers 1-0 on July 25: “It seemed like he was giving me a chance, but maybe my argument wasn’t compelling enough. I don’t know. But I definitely felt the compulsion to plead my case, and I did. On that small comebacker, with the pitcher running, I felt like I could afford to treat it a little more gingerly than I otherwise would. But I think that probably alarmed the powers that be.”

• After pitching into the ninth and earning his first win in a month, 4-0 over the Cardinals, July 29, following a tough Mets loss the night before: “We lost a heartbreaker yesterday. The propensity is to pout about it or mope about it. You really saw the character of this team today.”

• On convincing the remaining skeptics that he was for real: “There’s a lot of guys probably saying, ‘When is the horseshoe going to drop?’ And that’s OK with me.”

• After struggling to find his grip amid oppressive humidity in Atlanta but ultimately prevailing 3-2 on August 3: “Oh man, it was just straight guerrilla warfare tonight. I used every trick I knew out there.”

• After his knuckleball proved ineffective against the Phillies in a 6-5 loss on August 8: “It was kind of tumbling in there. It didn’t get that extra little wiggle that I’m used to getting.”

• After he blanked the Phils on one hit — allowed to opposing pitcher Hamels — on August 13: “There’s definitely no woulda-shoulda. There’s, ‘Aw shucks, I wish that wouldn’t have happened.’ That’s probably the most satisfying thing about this night for me is that there’s no regret. I had an outing without regret, and you rarely can say that about an outing. There’s always one pitch that you didn’t execute right, or a sinker you didn’t get or a ball you left over the plate that got raked in the gap. There’s always a regret. This game is about how to handle regret, it really is. Tonight, man, I could have pitched into the wee hours.”

• After the Mets came back to beat the Marlins 6-5 on August 24 despite his giving up a lead-changing three-run homer to Gaby Sanchez: “It’s just sad. You pitch your heart out and then one swing changes the culture of what’s going on in the moment. But I’m glad we won.”

• After an impressive 5-1 victory over the Marlins on August 29 when he scattered six hits over seven-plus innings: “I’m hopeful that for the rest of my career, the anomaly will be the bad outing. It’s nice to be on the same stat page, so to speak, but I don’t give it a lot of thought.”

• On his previously stated desire to serve as a ball man for the U.S. Open in the face of learning the tennis people don’t allow facial hair on those serving in that position (in a text message to David Waldstein of the Times): “I would prefer that they embrace me with beard. Especially for $7.75 an hour.”

• After an otherwise good day in which he bested Liván Hernandez and the Nationals 3-2 on September 8, addressing a baserunning ploy that went awry: “I got a little bit frisky. I don’t know how old Liván is, but I know he’s old enough to bait somebody. I’m older, too, so I was figuring, ‘Is he really arguing [with the umpire] or is baiting me here?’ I was affirmed that he was baiting me once I got out at third base. That was a terrible play. I was just trying to make something happen.”

• On his restrained but unmistakable criticism of teammates who didn’t join the Mets who visited injured veterans at Walter Reed Army Medical Center: “I’m a 35-year-old man with three kids, so I feel like what I say with a pure heart, I don’t have to apologize for it.”

• After his knuckleball baffled the Pirates in a 9-1 complete game victory on September 14: “It had some severe movement. That thing, especially with wind in your face, if you throw that thing slowly, it can move in four, five different directions.”

• After a 3-2 loss to the Phillies on September 24 when the big story was the questionable takeout slide Chase Utley aimed at second baseman Ruben Tejada: “If you deem as a team that it’s a dirty play then you should take action. Absolutely, you’ve got to protect your teammates, for one, and you’ve got to show the other team that you’re not going to roll over for them and let them step on your neck. That’s just part of the game, any game at this level. You don’t want to ever be a team that has the reputation that you can be kicked around and you’re going to go into the dugout after the game with your tail between your legs.”

• After his well-received final appearance of the season, an unforeseen relief stint in a 7-2 win over the Nationals on October 2 when Manuel chose him over bullpen refugee Perez: “Sure, you hurt for Ollie. You do. He’s had a tough year as far as the things that have happened with him and to him, and the things that he’s been asked to do and the way he’s handled it has been painted a certain way. I feel for him. But, at the same time, as a professional, I’ve got a job to do, regardless of his feelings. So I’ve got to compartmentalize that. But he’s my teammate and I’m for him.”

• On Manuel’s suggestion that he might bring him back in the season’s final game just to receive another round of applause from the appreciative Citi Field crowd: “If I had my druthers, that was an ovation enough.”

We have our druthers, and we stand in salute to 2010’s most unexpected and consequential gift to Mets fans.

A big tip of the cap to those reporters whose notebooks and recorders took down every most valuable syllable R.A. Dickey uttered in 2010.

FAITH AND FEAR’S PREVIOUS MOST VALUABLE METS

2005: Pedro Martinez

2006: Carlos Beltran

2007: David Wright

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Pedro Feliciano

Still to come: The Nikon Camera Player of the Year for 2010.

by Greg Prince on 26 November 2010 3:27 am Welcome to Flashback Friday: Take Me Out to 34 Ballparks, a celebration, critique and countdown of every major league ballpark one baseball fan has been fortunate enough to visit in a lifetime of going to ballgames.

BALLPARK: PNC Park

HOME TEAM: Pittsburgh Pirates

VISITS: 1

VISITED: July 20, 2002

CHRONOLOGY: 25th of 34

RANKING: 4th of 34

One of the best episodes ever of Cheers concluded with John Cleese as sardonic Dr. Simon Finch-Royce opening a hotel window and shouting to the city below:

Hear this, world! The rest of you can stop getting married now — it’s been done to perfection!

Fed up with Diane Chambers’s constant door-knocking and reassurance-seeking, Cleese’s character was being quite sarcastic. I, however, am not. I could easily to go to such a hotel window and exclaim the exact same sentiment to all those mulling or building a baseball facility after PNC Park. Per Dr. Finch-Royce, I’d exhort, “Envy them, Great American; envy them, Citizens Bank; for you shall never be as cozy as it!”

It was, in fact, from a hotel window overlooking Pittsburgh that I would have guaranteed PNC Park would be a total epoch-shattering success, and, like the good doctor, I would have staked my ballpark-loving life on it.

PNC Park was the moment a decade of throwback ballpark construction was leading up to. There were breakthroughs before, there was innovation en route, but the culmination of the phenomenon that began in the early 1990s reached its peak with the opening and blossoming of PNC. It must have. I can’t imagine any newer place ever being better. PNC Park was the moment a decade of throwback ballpark construction was leading up to. There were breakthroughs before, there was innovation en route, but the culmination of the phenomenon that began in the early 1990s reached its peak with the opening and blossoming of PNC. It must have. I can’t imagine any newer place ever being better.

I’ve seen nine ballparks for the first time since I was in Pittsburgh, all of them, except resuscitated RFK Stadium, as new as or newer than PNC. None of them came close to matching it for its intimacy, for its warmth, for its originality, for its sense of purpose, for its oneness with its surroundings….none of them.

Except that other teams in other cities need a place to play, I’m with John Cleese’s Cheers character, or at least channeling him: You can stop building ballparks now, baseball. It’s been done to perfection.

And I might have said that without ever leaving my hotel room, which played a huge role in forming my perspective on the matter. Stephanie and I stayed at the Renaissance, a name that probably means nothing to you. It meant nothing to me until I did a little checking in the planning of our trip to Pittsburgh and discovered the Renaissance was that boxy building that appeared in every panoramic shot of PNC. You know how your eye is drawn to the Roberto Clemente Bridge? If you follow it across the Allegheny River, away from the ballpark, you can see that building at its foot. It’s the one with the arch cut out in the middle.

That’s the Renaissance. That’s where we stayed. That’s where everybody should stay when they go to Pittsburgh, provided you get the room we got by dumb luck. Ours was on the tenth floor, tucked into the archway at an angle that allowed us to take in almost everything PNC had to offer without ever having to leave our accommodations.

Of course we wouldn’t stay glued to our window. Of course the idea was to get in the elevator, press down, walk through the lobby, hit the street, cross the bridge (just steps away from the Renaissance) and go inside PNC Park (just steps away from the Clemente). Of course we did that. But I swear we almost didn’t have to.

PNC Park from the hotel across the Roberto Clemente Bridge gave me a better experience than most ballparks do from their upper decks. It was like a super skybox suite that couldn’t be replicated at any ballpark no matter how many marketing wizards put their heads together to charge you for it. Our tenth-floor room offered hotel-like amenities (because it was a hotel); an incredible perch on the action; and the giddiness that came with sensing you were getting something for nothing. Well, not for nothing — the room cost whatever the room cost, but it wasn’t part of some extravagant Baseball Glimpse package, and nobody was hyping it to you. You just went to the window, you opened the window and you were practically inside PNC Park.

No kidding. We bought tickets for the Saturday night game but the Friday night game, as taken in from the tenth floor window could have counted as our first PNC affair. Hell, we actually stretched and sang along to “Take Me Out To The Ball Game” with the crowd from our room. They might not have heard us, but we could hear them.

***

I had never been to Pittsburgh before this pilgrimage and knew next to nothing non-baseball about it except for the confluence of the Three Rivers (the Allegheny and the Monongahela forming the mighty Ohio, and even this I knew from Ralph Kiner) and that it used to be sooty. A good friend in college was from the area and we had a running joke about how it dark it was during the day there because of all the smokestacks — it was funny because he assured me it was no longer true.

The sky was perfectly clear when we landed on Friday afternoon and the city was lovely. It struck me as one of America’s great undiscovered gems except I’m sure many millions of people before me had discovered it. It wasn’t just PNC Park, though I have to say that was the gem among the rivers. My first glimpse was on the shuttle in from the airport. It was breathtaking. Had I any real feel for how momentous it was, I would have jotted down the exact time I first laid eyes on it.

One of the dozens of great things about PNC Park is how indigenous it appears to the terrain, as if it grew along the banks of those rivers. Surely it existed when Fort Duquesne was established in 1754 and the city grew up around it, right? Though I know this to be inaccurate, it doesn’t seem cockeyed to imagine. PNC’s limestone exterior is nestled so comfortably into its space that it doesn’t look like it was built. It looks like it occurred organically.

And that bridge. Swear to Honus Wagner that the first time I saw PNC on television, when the Mets were playing the first exhibition games there in March 2001, I assumed the Roberto Clemente Bridge was some kind of golden walkway dreamt up by a clever architect to make the whole scene seem a little more, I don’t know, Pittsburghey…a design house’s complement to the black light standards and steel motif. Silly me — it was an actual bridge: the Sixth Street Bridge, unveiled in 1928 and brilliantly renamed in 1998 to dovetail with the construction of the ballpark

PNC syncs perfectly to its environs and it never lets you forget it’s the home of the Pirates (said with a straight face, skipping any and all cheap shots about the long string of sub-.500 seasons that has grown only more endless since I was there). The Clemente Bridge. The Clemente statue. The wall that’s 21 feet high for Clemente. Honoring Wagner and Stargell and Kiner (at least his hands) and lately Mazeroski with statuary. Loads of player banners. Loads of oversized Topps cards — not hidden away, not doled out grudgingly, mind you, but readily accessible and proudly displayed. Pittsburgh’s Negro League tradition got its due, too.

Some of this, the parts dotting the PNC exterior, we caught before we went to our official game on Saturday. After we checked in at the Renaissance and enjoyed an excellent Cuban restaurant next door, we walked across the Clemente (navigable by car and foot most of the time, limited to pedestrians before, during and after games) to explore. Two seasons into its existence, I’d salivated over PNC on TV but up close, even out for a stroll, it was even more astounding. Every inch of the place, every inch around the place, the sidling easy by the river as if intrinsic to the Western Pennsylvania ecosystem.

It wasn’t exactly PNCville around the ballpark, but there was enough in the way of sports bar action for those seeking it, and you were only a Clemente’s amble away from the edge of downtown if you sought food and drink that way. I also had no idea — remember, we were Pittsburgh tyros — there was something of an artsy section of the city adjacent to the ballpark. We wandered into the Andy Warhol Museum for a little non-baseball culture. I had no idea Andy Warhol was born in Pittsburgh. They later named the Seventh Street Bridge after him. I wonder if it and the Roberto Clemente Bridge ever have a catch. Or hit each other pop flies.

We inspected a bit of downtown Pittsburgh later but it was all prelude to our super skybox suite on the tenth floor. Having gathered takeout from a deli down the block, we headed for the hotel while ticketholders made their way across the Roberto (sad pecking order sign: Steelers t-shirts sold on Sixth Street before the Pirates game — football training camp was open and, as that Friday’s Post-Gazette explained, that meant Pittsburgh’s baseball season was over). Stationed at our window — windows, actually; one for each of us — we watched a pretty decent trickle of humanity stream over the river in advance of first pitch. We turned on KDKA for play-by-play but were served just as well by the voice of Pirate public address announcer Tim DeBacco. When he asked the 23,812 in attendance to rise for the national anthem, 23,814 of us stood.

Yes, we were that close. Except for losing a slice of right field, we could pretty much see everything that went on in the game, and aided by the broadcast team, we became honorary big fans of journeymen outfielders Adam Hyzdu (3-for-5 featuring a fifth-inning grand slam) and Rob Mackowiak (a two-run pinch-hit blast in the seventh). If Bob Prince’s partner Rosey Rosewell had still been calling Buccos games in 2002 and had bellowed his trademark home run call of “open the window, Aunt Minnie, here it comes!” we would have been ready.

Our windows were open. We sat by them, feet up, beverages handy, taking in a real, live baseball game without having to be at a real, live baseball game. It was akin to the Wrigley rooftops, I suppose, except no gouging was involved. We really did stand for “The Star-Spangled Banner,” we really did stretch in the seventh and we really did offer cheers for the home team as they defeated the Cardinals, 12-9. And we were blown away by what happened when the sun went down. PNC Park’s lights reminded me straight up of those old-time illustrations of Fenway Park or Crosley Field, the ones reproduced on postage stamps that had been issued a year before. In those iterations, the ballparks in question appeared to be bathed by light, as if by a cosmic shower head. That’s what happened here — but there was something even better! Set against the hills off in the distance (who knew Pittsburgh had hills?), PNC, from our angle, looked almost to have been carved into a bluff…like the Polo Grounds, for goodness sake.

Nearly thirty years of going to ballgames at this point in my life and I’d never had the Polo Grounds evoked. Technically speaking, we didn’t go to this game, but from the tenth floor of the Renaissance, it was close enough.

Experientially speaking, it was very close. We still had an actual game to attend the next night, and you could be damn sure we were going to attend the hell out of it. Still, the hotel window game is the one we recall most fondly when we recall our trip to Pittsburgh.

***

Saturday brought yet one more dimension to bear: a special guest star joining Stephanie and me. The date was July 20, relevant in that July 20 is the birthday of my Chicago-based friend Jeff (hero of the unforgettable Mets-Cubs Friday doubleheader of four years earlier). Jeff’s a fine family man — lovely wife, two bright children, including a daughter I induced with all manner of Metsabilia, when she was three or so, to adore Mr. Met — but he had mentioned every summer since we’d been corresponding that when July 20 rolled around, he did whatever the hell he wanted. Well, I suggested some months earlier, July 20 will be a Saturday, and Stephanie and I are thinking about going to Pittsburgh, and since it’s sort of halfway between New York and Chicago, and since this is your birthday and you do whatever the hell you want on your birthday…

No more needed to be said. Jeff put some frequent flier miles to good use and we agreed to rendezvous in the hours ahead of that night’s game. It’s one of those things I always thought sounded like a superb idea, meeting somebody in a city where neither of us lived just for baseball, but it was the first time I’d ever done it.

And, per the vibe that accompanied the weekend, it was superb.

Stephanie and I did a little more local sightseeing early, took a train ride (who knew Pittsburgh had trains?) and, as planned, we met Jeff in our lobby. He was staying a few blocks away without a ballpark view, but we dragged him up to our room so I could show him our catbird seat window and breathlessly describe what the previous evening had been like and looked like. He agreed it was sublime, perhaps just to get me to shut up about it already.

The three of us made good use of the Roberto Clemente Bridge, fitting enough in that Roberto Clemente was one of Jeff’s baseball heroes growing up. We each took turns posing with ol’ Bob’s statue and toured a bit of the riverfront. Jeff occasionally gazed through his trusty binoculars in search of aviary happenings. As a dedicated birder, Jeff keeps a “life list” of every species he’s spotted. He also, like me, keeps a log of every ballpark he’s visited.

I enjoy reading Jeff’s words on birds, but the obsessive language we share is ballparks, and the fact that we were seeing a ballpark new to us together for the first time added yet another layer of depth to the weekend. By the time we recrossed the Clemente for dinner at a very nice Italian restaurant downtown, we were deep in ballpark talk, trading stories and opinions the way we might have traded cards if we had grown up in the same place at the same time (though Jeff wouldn’t have traded me his Bob Clemente unless he had at least quadruples). Our dialogue probably wasn’t anything we hadn’t sent each other by e-mail in the previous half-dozen years, but for one evening the conversation was plucked from captivity and set free to roam into tangents, digressions and asides to say nothing of anticipation for what loomed directly ahead.

God, I enjoyed that.

***

Back across Roberto one more time, back to Pittsburgh’s North Shore to physically inhabit PNC Park. You’d almost think that after all the buildup and euphoria, the actual experience of going and being inside couldn’t help but be a bit of a letdown.

It was nothing of the sort. It was what all the walking and talking was leading to. And it couldn’t have been better.

For me to love a ballpark more (or at least rate it higher) than Shea, there has to be one instant very early in my immersion inside it when, without my brain doing anything proactive, my mouth drops open and forms nothing more than a quiet ohmigod. Wrigley had that. PNC definitely had that. It came after we emerged from the concourse and inhaled our first full view of the PNC Park vista.

Ohmigod.

Some parks, like Wrigley, aren’t quite done justice by television, even though they look great on TV. Some parks, like Fenway, are enhanced by television beyond their already high standards. PNC pulled off a double play worthy of Groat and Mazeroski. It had sucked me in from the moment I saw it on the tube, but in truly living color, my crush went hi-def.

Everything. Everything about it was incredible. There’s the downtown skyline. There’s our hotel in the foreground. (I can make out our window! We watched from there last night!) There’s the bridge. There’s the river. There’s the greenery beyond the green fence. There’s the ironwork and the seating and the ramps. Oh, it just blended so beautifully. The only thing I didn’t care for was the green batter’s eye as it got a little in the way of everything else, but I guess the batter did have to see the ball…so OK, it can stay.

Nothing that occurred during the game, taken in from splendid seats maybe 20 rows behind home plate, could have made me love PNC any more deeply than I did at that first internal sight. But nothing made me love it any less, either. The Pirates’ gamenight presentation (save, maybe, for a dopey Photoshopping of what celebrities would look like with mullets) was first-class. For example, the sound system was perfect. It’s an odd thing to remember, but because so many are ear-splitting, I noticed the acoustics were just right. Jason Kendall’s at-bat music — the “guess who’s back…back again” refrain from Eminem — was so sharp and so clear that I think it’s the reason “Without Me” soon became my favorite song of 2002.

We got a big kick out of the pierogi race, an amiable knockoff off of the sausage derby in Milwaukee. Would have loved to have tried a pierogi, or anything they were cooking behind us, but we were still full from dinner. Impressive concessions, if just to sniff. Impressive two-story team store. One of the pierogi magnets — Sauerkraut Saul — sticks in my office to this day and Stephanie still wears her Pirates-Mets First Game Ever shirt (deeply discounted from the year before) around the house.

Too often you watch a game from Pittsburgh on SNY and you see thousands of empty seats. But on this Saturday night, the Cardinals helped generate a near sellout of 35,000 (capacity is about 38,000, which sounded a bit small when I first heard it, yet felt just right when I was amid it). The offensive fireworks from the evening before continued, especially from our man Hyzdu, who contributed three hits, a pair of three-run dingers and seven RBI. Bucs blew away St. Louis, 15-6. It was a joyous night for people who came to root for the home team, not just applaud the home park. It got only better in the minutes after the final out when we tracked the baserunners and outs on the informative and attractive out-of-town scoreboard and confirmed the Mets held on to win in Cincinnati — yet another reason to cheer.

I could have kept cheering for PNC Park, lousy name and all. If I ever became prosperous, I decided, I’d buy season tickets here, never mind that I lived far from Pittsburgh. If I could afford it, I’d fly in on weekends and whenever else I could, just to sit here and watch baseball in the perfect setting. Maybe I could work out something to reserve that room in the Renaissance. Or, I thought, maybe I should just cut out the 332 miles and move here. That neighborhood around the Warhol seemed pretty nice…

I wasn’t moving to Pittsburgh and I wasn’t hauling ass for any more Pirates games, but boy was I smitten. And I still am, despite more recent associations with PNC Park as the place where late-inning Mets leads come to die agonizing deaths. Despite the often frustrating results and general malaise that surround every Mets-Pirates game, I could do with more Met visits to PNC just to ogle it more often on the telly. I’m not the only Mets fan who’s noticed it, either. When Citi Field was still in the drawing board phase, there was a quote from Jeff Wilpon expressing his admiration for PNC Park and how it, as much as Ebbets Field, was a model for what the Mets would build. Shortly after Citi opened, Wilpon cited PNC as inspiration for the finished product.

Good taste on Jeff’s part. I don’t see a damn thing that’s similar between the two other than size and steel — theirs is open and airy everywhere; ours continues to deal me bouts of claustrophobia — but I don’t hold that against Citi Field. No way anything built since PNC Park could match PNC Park.

It’s just too perfect.

***

The question you steadfast ballpark countdown trackers may be wondering isn’t, “If you love PNC Park so much, why don’t you marry it?” (which is easy to answer: Stephanie got to me first, and I believe marriage among a man, a woman and a ballpark is illegal in both New York and Pennsylvania), but rather, “If you love PNC Park so much, how could it possibly be only No. 4 on your life list?”

That’s a great question you haven’t asked, and I’ve certainly mulled it since July 20, 2002, when Jeff and I discussed our respective rankings on our final trek across the Clemente, back toward our respective lodgings. Jeff said he was ready to slot it above anything he’d ever seen. I did not argue the point with him, as there seemed no place better to experience a ballgame — of that I’m convinced.

Nevertheless, I guess I’d have to say a trio of other great ballparks got to me first and I’m extremely loyal and not a little sentimental about such relationships. Thus, the final three installments in this series will delve into the intense emotional attachments I formed for a trio of PNC predecessors, but honestly, if you’re looking for a good baseball time, you’ll never find a greater one than the one you’ll find out Roberto’s way.

Another countdown you should by all means monitor is being conducted by Dave Murray, who takes us through the Mets Guy In Michigan‘s version of the Topps 60 Greatest Cards of All Time. Naturally, they’re all Mets cards. He’s so far taken care of 60-51; 50-41; 40-31; and 30-21, and made a couple of detours for the sake of equal time and topicality. Dave might trade you an extra Bob Clemente, but good luck prying away his twentieth Mets Maulers.

by Greg Prince on 24 November 2010 12:20 am Either set your recording devices before embarking on the busiest travel/patdown day of the year or hurry back from wherever you’re spending the holiday, and for the love of Mike Bruhert be sure to get your bargain-hunting done early. SNY is running a SEVEN-HOUR MARATHON of Mets Yearbook, every one the network has produced, from 3 o’clock Friday afternoon to 10 o’clock Friday night.

The fourteen installments will run in chronological order. Brief teaser and refresher on contents:

1963: The Polo Grounds closes. Shea Stadium nears. Mets prospects agree the Mets are a good place for a youngster to find quick advancement. Casey Stengel is still talking.

1965: Casey finishes talking and hangs them up. Mets are still the Expressway to the Big Leagues. The winter caravan that remains a Mets tradition to this day (cough, cough!) winds its way deep into Long Island.

1966: Mets leave the basement and rise all the way to the boiler room. Ron Swoboda hits a mighty homer. Jacksonville Sun ace Tom Seaver looms as a possibility for ’67.

1967: Guess who made it up from Jacksonville.

1968: Jerry Koosman thinks to himself before the Home Opener. Buddy Harrelson tells Little Leaguers about The Good Lord. Gil wants you to know he’s doing fine.

1971: The Mets don’t hit, but they sure can pitch and give away batting helmets. Ralph Kiner instructs Ken Singleton so adeptly Montreal can’t wait to take him off our hands.

1972: Rusty! Willie! And sadness for Gil. But fine promotional dates, too.

1973: Edited to exclude NLCS and World Series footage (either for time or rights fees), but you can’t go wrong with a fresh dose of You Gotta Believe!

1975: Dave Kingman has personality. Mike Vail has star written all over him. Joe Frazier takes the reins for next year promising he’s not an evil devil (or am I confusing him with somebody else)?

1976: One helluva Bicentennial celebration in Flushing. Seriously. Stephanie saw the red, white and blue pageantry (like a million balloons) and decided it was more impressive than the final ceremonies at Shea. More festive anyway.

1978: In case you’re wondering if anybody can make stars out of Doug Flynn and Craig Swan, the answer is yes.

1980: The film starts with the hiring of a whip-smart, universally admired general manager and ends with a lot of talk about how great newly acquired Dave Roberts will be in 1981. Draw precedent-related conclusions at your own risk.

1984: The Mets stop sucking, and for 28 minutes, the message is essentially just that. Gary Carter shows up at the end to declare he’s saving his right ring finger for his World Series bauble, and son of a gun, he made good on it.

1988: Roger McDowell screws around with a camcorder, not nearly as entertaining as it must have sounded in those Mets Can Do No Wrong (except in the playoffs) days. Otherwise, Mets can do no wrong.

And there’s like a thousand more highlights from these highlight films that will, appropriately enough, be the highlight of your Thanksgiving weekend, whether you’ve never seen Mets Yearbook before, whether you’ve missed a few or whether you’ve dropped everything every time you flip by SNY and see it’s Dairylea Day yet again.

Watch it, record it, ignore everything else in deference to it. You’ve been suitably notified.

by Greg Prince on 23 November 2010 2:32 pm Clearly the Terry Collins era should be sponsored by an energy drink. Let’s hope it’s not Four Loko.

I watched our new manager’s literally bouncy introductory press conference and came away with one overwhelming impression: “This dude is into it.” If he was worried about being identified as laconic, I think he’s got that licked. A little vigor won’t be a bad thing for the Mets, though when he’s setting positive examples by running through walls, he should only remember to ease up before storming into 126th Street traffic.

While he bounced, Terry (we’re on a first-name basis already) said all the right things. Of course he said all the right things. If he used the occasion of his coronation to say the wrong things, then we’d really be in Blackout in a Can territory. There were some clichés about pitching and teaching. He handled the now requisite limited-perspective question about Chinese ballplayers skillfully (given his WBC experience, he is the right person to ask). He complimented the young Mets as some of the most polite fellers he’s ever had the pleasure of encountering on the diamond. He indicated he’ll communicate better than he did during his infamous stint with the Angels. And, in that vein, he declared he’s not the devil.

Didn’t seem devilish, though as Albert Brooks suggested in Broadcast News, the devil probably won’t have a long, red, pointy tail; rather he’ll look like William Hurt. Terry Collins doesn’t look like William Hurt, which is neither here nor there except to note that when you stick a baseball jersey over a suited 61-year-old man and top him with a baseball cap, it’s hard to concentrate on anything he’s saying, even about polite young Mets, talented Asian ballplayers or his non-devilish tendencies. All you can think is, ”Why do they make these guys wear suits if they’re going to pose them in jerseys?” and “Connie Mack had the right idea about eschewing the uniform when he was managing the Philadelphia A’s.”

The ritual of the offseason press conference seems to be evolving before and away from our eyes. The only non-broadcast reporter who asked anything for the cameras was the Chinese Media Net lady. All the usual wise guy print suspects (if you read the beat writers’ Tweets, you know what I mean) remained silent until they conducted their own mini press conference after Collins left the podium. Not being on-site for this event, I assume this arrangement is beneficial for the working media, though it makes for pretty deadly TV. I’m far more interested in hearing what Adam Rubin and David Waldstein — to name two dedicated Mets reporters — might tease out of Collins than listening to Russ Salzberg make certain Russ Salzberg’s voice is properly recorded for Russ Salzberg’s sportscast tonight.

Sandy Alderson spent valuable face time with Kevin Burkhardt for the benefit of those of us in the SNY audience. He is surely a different breed of cat from every general manager I’ve experienced in my Met lifetime. Everybody since Bob Scheffing — even lugubrious Steve Phillips — seemed like a Baseball Man. Alderson no doubt knows his baseball, but in his standup he mostly came off as a CEO who pencils you in for fifteen professional, reasonably substantive minutes and will forget about you before he’s onto his next meeting. He looks like he handles people in a way Omar Minaya never could have had he wanted. Definitely gave me the impression he has better things to do than talk to Kevin Burkhardt. It’s the same sensation I’ve gotten from interviewing corporate titans who have definitely given me the impression they had better things to do than talk to me.

Like any savvy bigwig, Sandy indeed has loads of pressing business on his plate. He’s got to fill out that coaching staff (HoJo’s gone) and tend to the bullpen (Valdes is a Cardinal and Feliciano will be offered arbitration) and, if we’re fortunate, work a miracle or two. Collins, meanwhile, can lose the suit, adjust his cap, tuck in his No. 10 jersey — chosen to honor erstwhile Met nemesis Jim Leyland though it’s eerily reminiscent of deep-seated Met nightmare Jeff Torborg — and bounce toward the east coast of Florida with a spring in his step.

Traditionally when I watch the Mets in official newsmaking mode, I find myself somewhere between inconsolable and queasy when it’s over. Today I’m modestly energized and unusually undisgusted. This could very well represent progress.

by Jason Fry on 23 November 2010 9:06 am Is Terry Collins well-organized? Or too intense?

Amid that rather pointless (for now) debate, I found this article by Adam Rubin at ESPN New York reassuring, with the likes of Josh Thole, Nick Evans and Dillon Gee saying pretty much exactly what you’d hope would be said.

There was just one small problem. If you haven’t read the article, click it and read it and see if you can find where you get worried. Go on. I’ll wait.

OK. For me at least, it was right here:

The Mets had a longstanding policy in which minor league players had to wear their pants legs high, like the old-time players did to expose their stirrups. Collins fought to have that policy ended.

“He battled for all of the players,” Thole said. “He went to [chief operating officer] Jeff [Wilpon], and had meeting after meeting with Jeff, just to try to get that rule changed — just to say, ‘Go out and relax and enjoy yourself when you play.’ “

He had meeting after meeting with Jeff, just to get a rule about stirrups changed?

Next time the Mets protest that Jeff Wilpon is treated unfairly and portrayed incorrectly, I’d like them to explain how Josh Thole — who seems smart enough not to consciously slag the owner in the press — had that wrong. Because that sure seems like pointless ticky-tacky micromanagement, like hamstringing decision-making, like the kind of thing that would make an organization sclerotic and dysfunctional and ridiculed by the rest of the sport. It sure seems to fit with a lot of stories we’ve been told are unfair.

I wrote yesterday that regarding Terry Collins, we ought to admit that people can learn and change. I also wrote that one of the heartening things about the arrival of the Alderson regime is that Sandy Alderson is too old, too well-paid and has too many better things to do to take shit from Jeff Wilpon.

I didn’t elaborate on it then, but that was actually meant as a left-handed compliment to the Wilpons. Because they have to know that about Sandy Alderson too. And if they know that and accept it, that’s a sign that they too are learning and changing — or at least know they have to. For which I applaud them, sincerely and without the usual helping of bloggy snark.

But we’ve heard this before. We heard about full autonomy back in the days when we albatrosses we were shedding were Bobby Bonilla and Eddie Murray. Unfortunately, we’re still talking about it now.

Here’s devoutly hoping that the Wilpons will actually get out of the way of the smart new baseball-operations folks that they were wise to hire. If they do that, I firmly believe the Mets are headed for becoming the kind of organization they and we have always wanted to be a part of.

But if they don’t, we will be back at this pass before too long — maybe in three years, or five, but too soon. And instead of being the National League equivalent of the Boston Red Sox, we’ll be the senior-circuit version of the Baltimore Orioles — whose fans know their problems start so high up the ladder that the time to solve them will be measured in generations.

Please no. I’ve survived Tom Seaver being traded and M. Donald Grant making the team the North Korea of the free-agent era and the deRoulets and Bobby Bo and Robby Alomar and being beaten by the Yankees and three late-season collapses. But that might really be the thing that broke my heart.

by Greg Prince on 22 November 2010 1:30 pm Somebody thinks Terry Collins is exactly what the New York Mets need in 2011 and 2012. Fine. Let’s see what he’s got.

Managerial choices don’t reveal themselves as brilliant or idiotic in the fall that they’re made. It’s in the fall that comes after the first spring and the first summer that we are able to say anything definitive about them, and surely that rule extends to the choice the Mets are set to announce.

Everybody can mine unflattering anecdotes from Collins’ past just as they can list glowing endorsements of his abilities. Everybody can compare his situation to managers with similar career trajectories and everybody who so chooses can take the logical step — or make the leap of faith — that if Sandy Alderson & Co. are as good as they are cracked up to be, then Terry Collins will turn out to be the right decision.

I had no problem that it took what felt like an eternity (but really only 23 days from Alderson’s official appointment to Sunday’s conclusive “multiple sources are reporting…” round of leaks) to land on Collins Avenue. It was an important hire, even if you buy into the role of the manager being relatively insignificant in the scheme of franchise success. The manager is still one of the primary faces of the franchise. The manager is still the person who meets with the assembled media twice daily throughout the season. No matter what system is put in place above him, the manager is still the one making the calls on which individual games will hinge.

When somebody bunts or doesn’t bunt or swings away and doesn’t deliver, the camera will find the manager in the dugout and we will reflexively think about and talk about the manager. When the ladies and gentlemen of the press seek out a key player after a loss, it won’t be the vice president of player development and amateur scouting whose moves will come up in conversation. When that player is quoted immediately thereafter, it won’t be the special assistant to the general manager who will exchange sideways glances with that player if the quotes are less than flattering. It won’t be anybody but the manager in and around the clubhouse day after day. It won’t be anybody but the manager who inspires analysis and impatience when things are going poorly and even when they’re going pretty well.

I’m glad Alderson’s crew worked thoroughly and diligently on this high-profile assignment even if I still can’t quite believe that a veritable nationwide talent search came down to essentially Terry Collins and Bob Melvin. But it did, Collins was the choice, and after absorbing his introductory press conference tomorrow, I plan to stop thinking about it and him until Port St. Lucie is open for business. For nearly two months, the entirety of the Mets’ operation has been devoted to eliminating a general manager and a manager; finding a general manager; surrounding the general manager with trusted aides; and finding a manager.

This is not why I watch baseball.

I am concerned about what actions Alderson and DePodesta and Ricciardi and Collins take in terms of the results they yield, but I shall no longer dwell on these individuals as the focal point of the New York Mets’ offseason. To use Matt Artus’s phrase from Always Amazin’, I contracted managerial fatigue by last week. It was a akin to the general manager malaise I felt as October wore on. Again, these were crucial decisions in determining the direction and possibly fate of my favorite baseball team, but it wasn’t baseball.

Thus, whether or not I think Terry Collins’s history of high-strung martinet tendencies indicates he looms as a disaster waiting to happen when he’s exposed continuously to the New York spotlight is irrelevant in shaping my view of him from the press conference onward. Terry Collins is the manager of my favorite baseball team and I want him to be the best manager he can be, I want him to be the best manager of all managers, and I will root for him to succeed immediately and enduringly.

I’ll lean on Alderson to do what needs to be done and Collins to take it from there because that’s what they’re here for. Then I’ll return to wondering who’s going to pitch in rotation with Mike Pelfrey, R.A. Dickey and Jon Niese while Johan Santana is out (and, for that matter, when he’s back); whether Jason Bay can rebound from both his scary concussion and his frightening mediocrity; if Ruben Tejada can ever hit like he can already field; if Daniel Murphy might carve himself a niche on this club; if Carlos Beltran has a hellacious salary drive in him; if one solid campaign out of Angel Pagan guarantees solid campaigns are his norm; if Francisco Rodriguez can resume being a closer or is yet another irredeemable albatross whose salary and persona must be shed at once; if Jose Reyes will be a Met for life or just one more year; and everything else that’s supposed to preoccupy baseball fans as November turns toward December, and a new year and another season emerge over the horizon.

Because that’s what we’re here for.

by Jason Fry on 22 November 2010 1:23 am Sandy Alderson’s honeymoon period as Mets GM is apparently over now that he’s decided to hand the managerial reins to Terry Collins. At least that’s what you’d conclude from the squawking on the FAN and in certain web precincts.

I’m trying to figure out why, exactly.

Yes, I’m aware that once upon a time Terry Collins had problems with Mo Vaughn and other members of the Anaheim Angels and ultimately resigned from his post.

You know when that was? It was 1999. Bill Clinton was president. His Russian counterpart was Boris Yeltsin. Yugoslavia was at war. We all went to see “The Phantom Menace.” Approximately every 42 minutes you got a CD from America Online in the mail, with your newspaper or possibly flung through an open window. Your technologically advanced friends had yet to discover Napster. Lance Armstrong had just won his first Tour de France. Brian McRae and Jason Isringhausen were still integral members of the Mets.

It was, by any measure, a very long time ago. I’m a completely different person than I was then. I bet you are too. It seems at least faintly possible that the same can be said of Terry Collins.

(And besides, remember that Mo Vaughn also savaged Bobby Valentine as a manager — the same Bobby Valentine we have all pined for at one time or another. Could it be the problem here is Mo Vaughn?)

Is the problem that Collins hasn’t had a big-league managerial job in 11 years? If so, there’s a pretty big asterisk there. In 2005 Paul DePodesta was about to hire him as skipper of the Los Angeles Dodgers, but DePodesta was himself fired before he could make that move. Last time I checked we were all thrilled with having DePodesta around. Given that, shouldn’t the fact that he was set to hire Collins be reassuring? Plus Collins had a stint managing in Japan, which only seemed to burnish the legend of the aforementioned Bobby V.

If the problem is that Collins is too intense, I’d like to know for what, exactly. For making Luis Castillo feel uncomfortable about getting too close to the Cheez-Its? If the Mets hit a midsummer skid and Collins sends the buffet airborne, I’ll be fine with that — there was many a night when Jerry Manuel showed up to chortle and dimple while I seethed and wished for a Piniella-like rampage. Besides, weren’t intensity and fire and all those other intangibles the things we liked about Wally Backman?

Is it the fact that he was arrested for drunk driving in 2002? That’s not something to be waved away, but if you’re disturbed about long-ago brushes with the law, you applied that same standard to Wally, right? Right?

Is it the fact that he doesn’t have a Mets pedigree? I sure as hell hope not. Because if you think about it, hiring Wally simply because he once wore orange and blue would have been very pre-Alderson Mets — a bunch of PR juggling and greasepaint meant to distract us from the condition of the tent. (I’m not saying Backman wasn’t a perfectly good candidate for other reasons. I hope he’s managing at St. Lucie next year, or that some other organization gives him a chance and he makes the most of it.) Collins was the team’s minor-league field coordinator last year; ultimately, that means more to me in terms of continuity than what he was doing 24 years ago. (For the record, he was managing Albuquerque.)

Beyond the fact that we don’t know much of anything about what Collins will be like as a manager in 2011, I don’t think managers matter tremendously — or at least I’d like to see some rigorous statistical evidence that they do. Jerry Manuel drove me insane with his idiotic bunting, inability to handle a bullpen and his Boo Radley Meets Mahatma Gandhi shtick, but I doubt any of these things cost the Mets much that was measurable. (His greatest sin in my book was playing zombie veterans instead of young players with potential.)

And even if you think managers do matter, does the hiring of Terry Collins really undo your trust in Alderson, DePodesta and J.P. Ricciardi? I was pleased enough that the Mets went outside their own dysfunctional organization for a GM, and over the moon that they picked three guys who give every indication of actually studying their business, instead of being unable to fill more than one need at a time, blaming reporters for berserk employees and forgetting the team’s ace had had elbow problems in spring training. Let’s not forget that we all knew or at least suspected nine months ago that this organization was a creaking, rotting disaster, yaknowwhatimsayin? The new team hasn’t proved anything, but the fact that there is a new team — and one so different in makeup, deportment and tone from the old one — speaks volumes.

For me, the biggest hope about the future of the Mets isn’t that their braintrust will look at stats more sophisticated than wins and RBIs, though that’s great. It’s that, to put it bluntly, Sandy Alderson is too old, too well-paid and has too many opportunities available to him to take shit from Jeff Wilpon. The Mets may still be badly run, but if so I’ll be stunned if Alderson turns out to be part of the dysfunction, or puts up with it for long. Everything we’ve read about the man suggests he wouldn’t; everything he’s done so far suggests brighter days are finally here.

Since I think that, until I see evidence otherwise I’ll trust him about Terry Collins. After all, 1999 was a long time ago.

And what did Mo Vaughn ever do for us, anyway?

by Greg Prince on 19 November 2010 6:00 am Welcome to Flashback Friday: Take Me Out to 34 Ballparks, a celebration, critique and countdown of every major league ballpark one baseball fan has been fortunate enough to visit in a lifetime of going to ballgames.

BALLPARK: Wrigley Field

HOME TEAM: Chicago Cubs

VISITS: 4 games, including 1 doubleheader

FIRST VISITED: August 3, 1994

CHRONOLOGY: 13th of 34

RANKING: 5th of 34

When I was nine years old, I briefly held quite the clever theory, namely that everybody famous did not exist. When we saw Tom Seaver on television, it was some kind of setup, I figured. How could it not be? How could anybody so much larger than life actually be living in the same life that we regular people lived?

I tried this theory out on my mother. She was good enough to shoot it down pretty quickly and plainly. No, she said, they’re real; who do you suppose is in those pictures anyway?

Ultimately, I couldn’t argue with that — I’ve always done better with logic than conspiracies — but still, it was tough to conceive that anybody or anything fantastically famous could be something you could just come upon. It’s probably why when I looked down from the Excelsior level at Citi Field and saw Tom Seaver walking through the Delta Club stands last June in civilian clothes (as, ironically, part of the nightly salute to military veterans), it was kind of shocking. I walk through the stands in civilian clothes. I’m a regular person. Tom Seaver is like a person-plus…y’know?

It’s that same concept of what’s real and what is simply too big a deal to be real that hit me the first time I approached Wrigley Field. I’d been aware of Wrigley Field for the previous quarter-century. I viewed it on TV at regular intervals every year. It was as photographed and filmed a ballpark as had ever been. It’s that same concept of what’s real and what is simply too big a deal to be real that hit me the first time I approached Wrigley Field. I’d been aware of Wrigley Field for the previous quarter-century. I viewed it on TV at regular intervals every year. It was as photographed and filmed a ballpark as had ever been.

Yet there it was, on the street, in Chicago, right in front of me.

In some ways, I still can’t believe it.

***

To say there is nothing like Wrigley Field is one of the more obvious statements one can make about ballparks, but perhaps it is more telling for me to tell you that when I was growing up there was nothing like Wrigley Field. I watched the Mets play eleven different opponents annually and only one of them held its home games in a facility that appeared completely different from all the others.

Shea was Shea and everything else looked like everything else, just about. Dodger Stadium had those seats behind the netting that lined up right behind home plate, and the Astrodome was clearly indoors, what with its weird lighting, and once the Expos moved out of Parc Jarry, you couldn’t help but notice the lingering track markings of Olympic Stadium, but mostly it was all a blur of Mets gray and road game bland.

But not Wrigley. Wrigley was a break from the sameness. Wrigley belonged somewhere. Our announcers talked about Wrigley like it was something more than a baseball stadium, like it was…like it was somewhere. Dave Kingman (for us, against us and then again for us) hit balls on to Waveland Avenue. If he were a lefty, he would have hit them onto Sheffield Avenue. These were streets on the North Side of Chicago, where the wind might blow in from Lake Michigan, but if it didn’t…watch out, ’cause Dave Kingman was goin’ to town.

I knew about Chicago geography because the Mets played nine games a year at Wrigley Field. I knew more about Chicago geography than I knew about any other city’s, and I had never been there. I knew Wrigley Field’s address was 1060 West Addison because that’s the address Elwood Blues claimed as his own in The Blues Brothers. Did other ballparks even have addresses? Did Ralph, Lindsey or Bob ever mention the names of the streets behind left field at Veterans Stadium?

Wrigley Field was somewhere and it was definitely something. Only Wrigley had ivy. Only Wrigley had that hand-operated center field scoreboard. Only Wrigley had day games and, for the longest time, nothing but day games. Only Wrigley kept its capacity way below 50,000 (it wasn’t even close). Only Wrigley had Bleacher Bums. I read about them and I didn’t like them with their hating on hippies and throwing of beer, but they were identifiable. Who sat in any part of Three Rivers Stadium? Who knew? Nobody ever talked about any other ballpark in the National League the way everybody talked about Wrigley Field.

And the damndest thing was how long it had been there. Built in 1914 for the Chicago Whales of the Federal League as Weeghman Park, it became home to the Cubs in 1916 and changed its name to reflect Cub ownership in 1926. By then, the National League lineup of ballparks was well set for the next half-generation: Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis; Forbes Field in Pittsburgh; Crosley Field in Cincinnati; Braves Field in Boston; Ebbets Field in Brooklyn; the Polo Grounds in Manhattan; the Baker Bowl in Philadelphia; and Wrigley Field on the North Side of Chicago. In 1938, the Phillies abandoned the tin-fenced bandbox to share Shibe Park with the A’s. With that switch, the octet of N.L. home fields remained unchanged clear through to 1952.

None of those buildings has seen major league baseball action since 1970. None except for Wrigley.

You can pick any spot you like in the last 95 years and reach a similar conclusion. In the year before the first National League expansion in 1962, the senior circuit’s ballparks of record were Crosley, Forbes, Shibe (renamed Connie Mack Stadium), Sportsman’s (renamed Busch Stadium, predecessor to the round version), County Stadium in Milwaukee, the Los Angeles Coliseum and the recently opened Candlestick Park…and Wrigley Field. No baseball in any of those places not named Wrigley since 1999.

For sixteen seasons, from the day the Expos took up uncomfortable residency at the Big O in 1977 until the next expansion kicked in, these were your stadia: Three Rivers, the Vet, Riverfront, Busch II (the circular one), the Astrodome, Fulton County, Jack Murphy, Candlestick, Dodger Stadium, our very own Shea Stadium, the aforementioned Big O…and Wrigley Field. Only Dodger Stadium has survived to keep Wrigley Field company on the National League schedule. And once the Marlins slide southward from their overly named facility in Miami Gardens to their as yet unnamed park in Miami proper, both ballparks from the 1993 expansion will be off the N.L. map.

By 2012, the National League ballparks with the longest stretch of continuous use by their primary occupant will be:

1) Wrigley Field, since 1916

2) Dodger Stadium, since 1962

3) Coors Field, since 1995

Or, to put it another way, starting with 1916 and running through the season after the next one, 14 National League franchises will have played regularly scheduled home games in 40 different venues, including two (the Polo Grounds and County Stadium) that were used by two different N.L. clubs. The only teams to call only one place home will be the Cubs and the Arizona Diamondbacks…who came along a mere 82 years after Wrigley Field took in its apparently permanent tenant.

To say ballparks come and go from our midst is an understatement — and an inaccurate one when applied to where the Chicago Cubs play.

Wrigley Field not only perseveres, it preserves. Catch a glimpse of it in a newsreel from the 1930s and it appears not much different from the Wrigley you’ve been seeing on TV all your life. Its vicinity may have grown more commercial, and various owners may have upped the modernity ante here and there, but when you look at it, Wrigley is still Wrigley.

Television opened my eyes to Wrigley, but Wrigley wasn’t made for TV. It was made for me to go see for myself. That was the goal for many years. Long before I fathomed I could, as a matter of course, visit ballparks other than Shea, well in advance of my fashioning a dream of seeing as many ballparks as I could, there was only one that was specifically on my must-go list.

I already knew where it was. Now I just had to get there.

***

Maybe, as the Fox promos from a few years back put it, you can’t script October, but Stephanie and I scripted our first multipark journey in the summer of 1994 exquisitely. Land in Chicago on Saturday. Visit the overwrought sequel to the late Comiskey Park on Sunday. Tool up I-94 to Milwaukee, the main Miller plant, Edwardo’s phenomenal stuffed pizza and homey County Stadium on Monday. Tool back down I-94 on Tuesday, take in something that has nothing to do with baseball — in our case, the Art Institute of Chicago — so we don’t seem overly one-track minded. And then, as if to build to a crescendo, you save the best for just about last.

Wednesday was Wrigley Field day…day, to be sure. Night games had been around the North Side since 1988, and I’m sure they served a purpose, but they didn’t serve mine. I could go to a night game anywhere. This was the day I’d been waiting some 25 years for, ever since I first heard of the Cubs and decided I didn’t like them. By 1994, the Mets and Cubs had been separated, made to sit in separate divisions, perhaps a result of them having talked too much and disturbing their N.L. East classroom. It was too bad. I loved the Mets-Cubs rivalry, from when it worked out well for us (1969) to when it didn’t work out well for either of us (1970) to when nature displayed its bizarre sense of humor (1984, 1989) and gave the Cubs a break at our expense.

The goal was to see Wrigley Field. The übergoal was to see the Mets there, preferably on a Friday afternoon (where else did they play on Friday afternoons?), with the Mets and Cubs battling it with something on the table (instead of merely knocking around that basement co-op they shared in the late ’70s and early ’80s) and, as long as we’re dreaming, make it a doubleheader, the way Ernie Banks would. That wasn’t happening this afternoon on the North Side. I’d have to settle for the Cubs and the Marlins, just one game.

I could handle that. I could even handle taking the bus to the ballpark, an option I had never considered outside of a camp trip to Shea. Stephanie and I began our Wednesday with a detour to the Chicago Historical Society — everything on this vacation felt like a detour once Wrigley loomed as our prime destination — and when we stepped outside to make our way to the El (the elevated line to Wrigley…that was part of the übergoal, too), a bus appeared that was headed to where we needed to be.

Imagine that: you get on a city bus and it just happens to stop a ballpark that’s been in operation since 1914, and the ballpark is where some people get off because their team has playing home games since 1916, and it’s where they go the way the rest of us go to our ballparks that, whatever their charms, are not Wrigley Field.

But this, once off the bus, was exactly that. It was Wrigley Field.

It was really here, right where Elwood Blues said, at the corner of Clark and Addison. It was really here, with the red marquee, clarifying that the Chicago Whales of the Federal League had long gone off to sea, that this was, no doubt about it, WRIGLEY FIELD HOME OF CHICAGO CUBS.

It was really here. Buses rolled by. A McDonald’s was across the street. Bars were nearby, too. Somebody I interviewed a couple of weeks earlier, from a beer importer, told me they had an account he could recommend where we could stop in before the game for a cold one.

Like I needed a cold one. I had Wrigley Field in my face. I was already intoxicated.

***

The Cubs, after thieving two division titles from the Mets in 1984 and 1989, went through phenomenon phases, as if Wrigley Field wasn’t phenomenal enough. Lee Elia’s caustic 1983 appraisal of critical Cubs fans — “Eighty-five percent of the fuckin’ world is working. The other 15 come out here.” — proved prophetic, in a way. There were times when it seemed 15% of the world was filing into Wrigley Field. Day games, night games, didn’t matter. Word was you couldn’t get a ticket.

1994 was not one of those years. We got the tickets pretty easily (ordering them “online” for novelty’s sake) and there were still plenty left when we arrived. Paid attendance for our first game at Wrigley was a little over 26,000, not the crowd scene I’d anticipated.

Which was fine. I didn’t want a scene. A scene I could get on television. I caught Wrigley when it was relaxed, when it was just a ballpark with two ballclubs playing one ballgame as might have been going on in just about any year since 1916. There was nothing on the table for the Cubs or the Marlins. I could sit back with an Old Style and take that in with ease.

Here’s what I remember about the ballgame itself: almost nothing. Here’s what I remember about Wrigley Field: almost fainting from how beautiful it was. Our seats were great. Maybe all seats there are great, but these definitely were. Got a great downstairs panorama of Waveland over there and Sheffield over there, and the ivy in the foreground. Jesus, there’s really ivy on that wall! It wasn’t a photographic illusion. It was small yet it was grand. The players were close by. Harry Caray led us in “Take Me Out To The Ball Game.” The wind blew out more than in. The Cubs scored eight. The Marlins scored nine.