The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 27 April 2010 8:00 am Update: Here’s this story revisited for NPR.

Near the end of winter my neighbor’s younger brother died unexpectedly. Emily and I are friendly with our neighbor, and offered him our condolences. But we don’t really know each other, for all the usual city reasons that you regret on one level but mostly look past while you’re busy being busy.

On Sunday I was walking through the neighborhood when I came across my neighbor rolling a luggage cart piled with stacked bags and boxes. I waved, and he stopped me.

“Just the person I wanted to see,” he said. “You’re a baseball fan, right?”

He’d just finished the unhappy business of cleaning out his brother’s apartment. A lot of stuff had gone to the charity shop, but there were some things he hadn’t wanted to just hand over. He said his brother had been a baseball fan and had kept some things, which he didn’t know what to do with.

Standing there on the street, my neighbor drew out one of the bags from the stack on the luggage cart and opened it. Inside was a stack of yearbooks. The 1961 Yankees were on top. Farther down in the stack I saw the Jets logo, and then a familiar sight: Tom Seaver smiling behind assembled baseballs. Mets, 1975. Then a Seventies Yankee, swinger’s locks flying, about to crash into a catcher at home plate. Then Mr. Met in a tri-cornered hat. 1976 — I’d had that yearbook, when I was a kid. Standing there on the street, my neighbor drew out one of the bags from the stack on the luggage cart and opened it. Inside was a stack of yearbooks. The 1961 Yankees were on top. Farther down in the stack I saw the Jets logo, and then a familiar sight: Tom Seaver smiling behind assembled baseballs. Mets, 1975. Then a Seventies Yankee, swinger’s locks flying, about to crash into a catcher at home plate. Then Mr. Met in a tri-cornered hat. 1976 — I’d had that yearbook, when I was a kid.

My neighbor explained that he hadn’t wanted to leave the baseball stuff to be thrown out or sold to just anybody. He wasn’t interested in getting money for it, but he did want it to go to someone who would appreciate it. He looked harried, but mostly sad: He knew there were people out there who would love this stuff, but he didn’t know how to find them.

“I can help you with that,” I said.

So later that afternoon I stood in my neighbor’s apartment, looking at a daybed covered with a stack of baseball books and four boxes — his brother’s baseball collection. The books tended toward big volumes celebrating the game’s history — the kind of lavish coffee-table things I’m always tempted by in bookstores. They looked brand-new. A big box held a stack of games by Cadaco, a company I’d never heard of. The games were some variant of Strat-o-Matic, from the late 1960s and mid-1970s. Another box held the yearbooks. And then there were two shoeboxes. My neighbor said those were full of baseball cards, and I could have them if I wanted them.

I told him I’d take the collection and look through it. Some of it might be pretty valuable, I said, adding that I’d set that stuff aside so he could figure out what to do with it. The things that weren’t so valuable I’d find homes for. The books, for instance, would be a great baseball introduction for Joshua, a way for him to quietly read and soak up knowledge and backstory on his time, arming himself with tales of Ty Cobb and Ted Williams and Frank Robinson. That’s how I’d caught up with the adult baseball fans in my life, spending evenings and car rides reading “Strange But True Baseball Stories” and hagiographies of vanished stars and chronicles of long-ago seasons.

We ferried the stuff down to my apartment. I sorted through the baseball books, putting some in the upstairs bookcase and some in Joshua’s room for him to discover. I put the mysterious games in the closet for closer scrutiny some other time. I looked through the yearbooks (they turned out not to be worth as much as I’d thought), pondering who might like them. There wasn’t a yearbook newer than 1980, though there were copies of Street and Smith’s annuals from 1985 and 1986. The newer stuff was pristine, almost as if it hadn’t been read. The older stuff showed its wear — it had been well-kept, but obviously read quite a bit.

And then I turned to the shoeboxes. These weren’t the long white boxes that card collectors use these days, but honest-to-goodness shoeboxes bearing the logos of old brands: Thom McAn and Walk-Over. 9 1/2. They would have fit me, I thought idly.

I opened the first one. There were cards stacked this way and that, and I suddenly remembered something I’d known as a child: Despite their place in Americana, shoeboxes aren’t a great fit for baseball cards, as long rows of cards don’t completely fill up the box, leaving it vulnerable to flexing. This box was tightly and carefully packed, with no wasted space. The second shoebox was the same way, but there was a baseball nestled among the cards. I eased it free and saw a signature on it, one I knew.

BABE RUTH

Wow, I thought. Then realized: No. It was a stamp. Next to the Babe’s signature was a stamp of Hank Aaron’s. The ball was white, but you could feel its age: It had gone hard as stone.

I put the souvenir ball aside and took out stacks of cards, arranging them on my dining-room table. There were hundreds of 1974s, with chevrons top and bottom. The corners were tight and perfect. I realized I wasn’t used to seeing old cards like this, as pristine cardboard rectangles. Mixed in with them were dozens of gaudy 1972s, with their Pop-Art colors and 3-D stars, a handful of 1975s, and ranks of dour, almost-military white 1973s. Then there were lots and lots of silver-gray 1970s, the last Topps cards to bear painterly portraits.

I started sorting the cards, at first idly, then methodically. There were few if any doubles from the 1972s and 1973s and 1975s. For the other two years there were lots — the stacks of doubles quickly topped 50, then 100. My neighbor’s brother had all but cornered the market on 1974 traded cards of Steve Stone, and the cards practically sang with a frustration I recalled: In 1976, the first year I’d collected, I’d been a magnet for traded cards of Mike Anderson.

The 1970s were in good shape, but not collector-quality. A lot of the corners were rounded, and some cards had been written on. Same with the 72s: Many had positions added on the front in pen. The 74s, on the other hand, were marred only by the occasional faintly burred front or discolored back. I remembered what caused those patterns. In a wax pack, the rectangle of dry pink gum was bound against the front of the first card, and adhesive often got on the back of the last card.

My neighbor’s brother had been born eight years before me. Looking over his cards, I did the math. He’d been nine when he collected those 1970s, and 14 when he bought a few 75s. I’d started collecting in 1976, when I was seven, and quit (the first time) in 1981, when I was 12. The ages were different, but the age range was the same. And so was the pattern of wear. I’d played with my 1976s endlessly, and today they’re almost round. My 1981 cards? They were put away basically untouched.

I kept looking for signs of order as I sorted the cards, but there weren’t any. Well, except for one thing: I wasn’t finding star cards or valuable rookies. Until, in the middle of the second box, I came to a 1970 Willie McCovey. Next was a 1972 Willie Mays (with CF added in ballpoint pen). I wasn’t surprised by what followed: Dave Winfields, Nolan Ryans, a Mike Schmidt, Tom Seavers, Joe Morgan, Harmon Killebrews, Pete Rose, Rollie Fingers. At some point (around 1980, by the evidence) my neighbor’s brother had taken down those shoeboxes and searched for stars. I suspect he sold, traded or gave some away — there were fewer valuable cards than chance would dictate, and no 1971s — and then put the rest back, where they sat undisturbed for another 30 years.

And there was one other, much subtler sign of order.

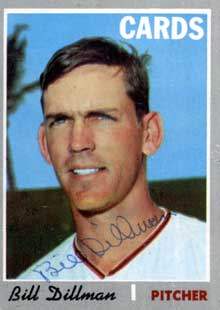

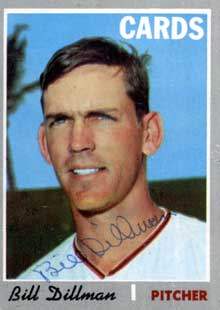

Looking through the 1970s, I found this sequence: Rod Gaspar (Mets), Bob Aspromonte (Braves), Jose Cardenal (Cardinals), Dave Marshall (Giants), Larry Stahl (Padres), Joe Foy (Mets), Sandy Alomar (Angels), Calvin Koonce (Mets), Bill Dillman (Cardinals), Ron Herbel (Padres), Dick Selma (Phillies).

That is not a random grouping: All of those guys were Mets at some point, except Dillman. I looked up Bill Dillman. He was a member of the 1972 Tidewater Tides.

My neighbor’s brother was a Mets fan — and not a casual one, either. He knew Larry Stahl and Ron Herbel had worn blue and orange even if they’d never had Mets cards, and he knew that Bill Dillman hadn’t quite earned a ticket back to the Show as a member of the Mets organization. He’d collected cards for a while, then put them aside, their apparent randomness hiding patterns that the right person would be able to read. Someone who knew not just baseball cards, but also obscure Mets. Someone like me.

Looking at those cards, I knew he’d loved the same team I do, and I could see how his mind had worked. I sorted his cards carefully, separating them into years and doubles. I put aside the small stack of valuable cards for my neighbor to consider. I checked to see if the cards of Mets and guys who’d been Mets were in better shape than my own, swapping mine for his when they were. I put aside the partial sets of 1970s and 1974s I’d reconstructed. And then I sat at the table pondering homes for yearbooks and thinking about baseball fans I knew who would see a packet of random 30-year-old Cardinals or Yankees or Expos as a welcome gift, worth pondering at odd moments or kept to be passed on to someone else who would appreciate them.

I never knew my neighbor’s brother, but I think he would like that.

by Greg Prince on 26 April 2010 3:08 pm The Mets Hall of Fame & Museum is Amazin’, Amazin’, Amazin’, yet it has to share honors as the most Amazin’ upgrade at Citi Field in 2010 with the quiet and most welcome infusion of Jane Jarvis into the sound system.

You know what plays over the loudspeakers when the Mets take the field now? Jane’s 1996 recording of “Meet The Mets”. Twice I’ve heard it at a game’s outset, and twice I’ve been moved to applaud heartily. (Let the players think it’s only for them assuming their positions.) I also heard it on the way into the ballpark last night, which made the impending rainy evening a whole lot sunnier. Earlier this month I kvelled when they played Jane’s you know it when you hear it rendition of “Let’s Go Mets,” an instrumental she composed that’s a little like “The Mexican Hat Dance,” and not at all to be confused with the “Let’s Go Mets” from the ’80s.

We note the Mets’ presentation blunders when they occur, so we should also praise them to the high heavens (where Jane is presumably doing two shows nightly) when they execute perfectly. Reinstating the music of Jane Jarvis, evoking precious Shea memories and introducing new ones at Citi Field is one of the best things Mets management has done in a very long time. So caps off to them.

Want to know more about “Meet The Mets”? Read Richard Sandomir’s article about its origins and endurance in the New York Times. As for the late Ms. Jarvis, her friends (and there were many) are holding a memorial tribute for her at St. Peter’s Church two weeks from now, Monday evening, May 10, 7:00 PM, on East 54th Street in Manhattan, just east of Lexington Avenue. St. Peter’s is spiritual home to New York’s jazz community and the perfect venue — as long as Shea Stadium isn’t available — for a night of remembrance and music. Hope you can make it.

Author Lee Lowenfish, who alerted us to the St. Peter’s event, tells Jane’s life story beautifully at his blog. Brighten up this rainy day and read it here.

by Greg Prince on 26 April 2010 12:56 am An amusing, apocryphal anecdote alluding to Gibson’s legendary power is told about a home run he hit in Pittsburgh. The ball jumped out of the park like it was shot out of a cannon, clearing the fence and sailing out of sight. The next day, in Philadelphia, a ball came down out of the sky and landed in an outfielder’s glove, whereupon the umpire promptly declared to Josh, “You’re out yesterday in Pittsburgh!”

—Negro Leagues Baseball Museum

The mist became a downpour. The infield disappeared under a tarp. Time in this particularly interminable game — two hours to play five innings, dictated to a great extent by a strike zone known only to Mike Estabrook’s fortune-teller — was suddenly of the essence. The tarp wasn’t going anywhere, but a train or two would be. The goal went from wriggling Mike Pelfrey out of his jams, to not standing around when we could be making tracks.

The tarp stayed, covering up not just basepaths but all physical evidence of the five longest 1-0 innings Citi Field has ever witnessed in its short life. We left, satisfied that while Pelf bent and bent and bent, breaking was no longer what he automatically did. My friend was soon Jerseybound. I just wanted Woodside and a convenient connection to the Babylon line.

I could babble on, all night, I suppose, about what a strange venue Citi Field was for a Sunday night, late April, five-inning-ish affair. How strange the 8 o’clock start. How strange the breath that visibly wafted from everyone’s mouth. How strange the utility of that ski cap the Mets gave out the other night; I thought I’d be wearing it in December, not right away. How strange the Mets’ offer to let everybody move down and get wet in better seats. Was management taking pity on its customers or just noticing that empties don’t look very good on ESPN?

Thirty or so pitches for Pelfrey in the first, but no runs. Thirty or so more pitches for Pelfrey in the second, yet again no runs. Ride that Pelf! Alas, you can only ride that pony so far for so long at such a Mike-boggling rate, thus we were all over his pitch count, but he got us through five alive. Tommy Hanson of the Braves wasn’t exactly an exercise in economy, either. He needed to throw 93 pitches to an inept offensive team for five innings, giving up only one unearned run. Pelfrey worked harder — 106 pitches — but the batters he faced were even more offensively inept (half the Brave lineup was batting below .200) and besides, Mike just keeps finding ways to toughen when he used to just tighten.

Raul Valdes comes on in the 1-0 game to start the sixth. He threw exactly one pitch to Jason Heyward. It was a strike. Then lightning figuratively and literally struck. Buckets of rain. Never has a tarpaulin been such a happy sight. We assume the game will be called. We’re not sure, but trains are trains, and it’s after 10 o’clock and come on, will ya look at what’s coming down?

I’m home by 11:30. Just before 11:40, I turn on ESPN, for whose benefit we play 8 o’clock Sunday night games, and I see “F/6” — that means it’s final; all you need is five innings, of course. I start clapping in my living room for our 10-9, series-sweeping Mets, not much more than an hour since I stood surveying the skies over Citi Field and fumbling for my umbrella. We just this very moment won, and technically I stayed for every pitch.

All 200 of them.

by Jason Fry on 24 April 2010 11:25 pm Baseball isn’t really a team game.

We talk of it as if it is one, but with a couple of exceptions (relay throws, hit-and-runs) it’s really a game of individual acts. The pitcher makes his pitch or doesn’t, the batter hits it or doesn’t, a fielder catches it or doesn’t. These individual acts get strung together into the illusion of a group effort — and we imbue this stringing together with qualities that are either impossible to quantify or don’t exist. Our team is hot, is firing on all cylinders, is coming together, and so forth.

This is one of the key lessons of the sabermetic era, exposing a lot of psychobabble and broadcaster bushwah for what it is. I’ve come slowly to appreciate advanced stats: They help me better understand the game I love, which is reason enough to engage with them. Beyond that, they’re excellent for figuring out which players are lucky and which ones are good, as well as which ones are being sabotaged by performance of those around them. And they’re crucial for figuring out how to construct a roster, something the Mets may decide to get better at one of these years.

But for all the usefulness of advanced stats, games and stretches of games and seasons still have storylines. We insist that they must, and so we create them, searching for meaning and constructing it out of whole cloth if need be. So it is with the 2010 Mets. There isn’t any reason I can think of that the 2010 Mets should be a great come-from-behind team — I’m sure it’s a statistical quirk of this very small sampling of games. But as a fan — which is to say an amateur storyteller — that’s what they’ve become. They’ll hang around until the late innings and then jump on you. Dangerous comeback team, these Mets.

And that’s great.

Come-from-behind teams are enormous fun to root for. Cheering for one makes tie games more sweet anticipation than nagging worry, and early deficits become just part of the dramatic arc. You don’t get too down, because you’ve seen again and again that the bad guys will be laid low, patience will be rewarded, and justice will prevail. The certainty that all of this is selective memory makes it no less fun to watch or listen to.

And it’s even more fun when it’s the Braves. The Braves — once the Globetrotters to our Generals — haven’t really been an outsized factor in our baseball lives since Beltran’s march to the sea, but you can root against laundry as easily as you can root for it. And goodness knows you can still root against Bobby Cox.

Cox didn’t come out of the dugout today, probably because if he had the temptation to throttle someone else wearing his uniform would have been too great. He’s retiring at the end of the season, though for most of this afternoon his charges looked like they were trying to get him to storm away from his desk and throw his ID at the harpy from HR before the cake and the speeches. (What do you want to bet Yunel Escobar is locking himself out of his hotel room in a towel right about now?) The Braves have played two days of stupid, with Chipper Jones not a factor and not playing tomorrow, Brian McCann not particularly damaging so far, Met killer in training Jair Jurrjens mastered today and Jason Heyward not yet embarked on what I’m sure will be years of ripping out our hearts.

Meanwhile, for us it was a (relative) lark: Jon Niese was wild and typically Metsian in his inefficiency, but held the Braves down when he needed to, keeping us down just a run for our (is it too early to call it typical?) late-inning charge. Good eye by Ike, long drive by Frenchy, Jose causing trouble on the bases (he’s got to keep Henry Blanco in the SB rearview mirror, after all), a Jason Bay sighting, and a welcome lack of drama from K-Rod, and we were officially a .500 club.

Mediocre never felt so good.

by Greg Prince on 24 April 2010 3:39 am “Citi Field,” according to the 2010 Mets Media Guide, is “home to one of the longest ribbon boards in baseball.” That is most definitely not one of the Top 1,000 most interesting facts to be found in this otherwise indispensable publication. For that matter, the ribbon boards, when they’re flashing advertisements that have zero to do with baseball, are about the easiest feature to ignore in the entire ballpark. Yet Friday night, during the sixth inning, a message glowed that totally fit the moment:

OPPORTUNITY. PURE AND SIMPLE.

Those words were paid for and posted to promote a business news and opinion cable channel, but they were uncommonly relevant to what stared the Mets in the face as they batted in a close game:

Opportunity. Pure and simple.

With one out, Jose Reyes, suddenly a three-hole hitter extraordinaire, tripled. Jason Bay, cleanup hitter more by default than merit to date, followed by doing exactly the same to put the Mets ahead 2-1. You know the last time the Nos. 3 and 4 hitters in the Met lineup tripled consecutively? Never. In fact, a trusted source tells me, the only time the No. 3 and 4 Met batters even tripled in the same game was in 1964, when the pairing was Ron Hunt and Joe Christopher and the triple-happy haven was Connie Mack Stadium.

Go to a Mets game and maybe you’ll see something you haven’t seen in 46 years.

That’s also about how often the Mets cash in on opportunities. Oh, exaggeration, you are amusing when we win, but really, a runner on third, less than two out and he is brought home with a triple? That’s fantastic. Then, a moment later, there’s a different runner on third and still less than two out? We don’t need a third consecutive triple. We just need a fly ball.

That’s scarier than it sounds, considering the batter is David Wright.

Nineteen months ago today, David Wright had a chance to deliver a sac fly that could have changed history and averted impending collapse. It was near the end of 2008, a year when Wright tied for the National League lead in sac flies. If only he had led it instead. If only he had lifted a fly ball to score Daniel Murphy from third with nobody out in the bottom of the ninth on September 24, 2008 and the score tied. Murphy had tripled, but he died there. The Mets died an inning later. Their season and stadium died four days after that.

So much death for such an ostensibly happy pastime.

David Wright has lofted seven sacrifice flies since that night of pure and simple opportunity eschewed, one of them, tauntingly, the very next night (generating an instant and ungrateful grumble of “Where was that last night?” from this particular spectator). Of course David tries hard, even as perception dies hard. David had driven in seven runs on sac flies since driving in none on September 24, 2008. But it’s the none that stubbornly stays with a fella.

Now, however, he has driven in eight since that fateful ninth. Wright brought home Bay with a very long fly ball that would have flown beyond a less confining outfield wall than Citi Field’s. But this, for better or worse, is Citi Field, where triples can be instantly doubled yet sacrifice flies are always appreciated.

Our new No. 5 hitter made the score Mets 3 Braves 1. It wasn’t as aesthetically exciting as what the 3 and 4 guys had just done, and it didn’t turn as many heads as No. 6 hitter Ike Davis did when he launched (and I mean launched) his first major league home run onto the Bill Shea Bridge, presumably causing a pothole in the process. Wright’s fly ball also wasn’t nearly as entertaining as Jose’s seventh-inning infield fly that befuddled Brave after Brave while triggering heretofore unseen baseball instincts in Angel Pagan who thrillingly knew enough to cross a plate that every Brave left enticingly uncovered.

But that Wright sac fly was as huge as anything else in this game, and I swear I’ll try to make it rather than the lingering sting of 9/24/08 my default man on third, less than two out, David coming up scenario. It probably won’t take, but I’ll attempt to keep it in mind.

Busy night all around, from John Maine’s spasming left elbow (leaving because of pain in his nonthrowing arm — not to make light of anybody’s pain, but that sounds, on the surface, like something that would befall Steve Trachsel) to Hisanori Takashi’s seven relief strikeouts in three emergency innings to the Braves’ four errors to Frankie Rodriguez registering three slightly uncomfortable outs 24 hours after he netted five. A little something for everyone, and a lot to hope on from here.

You hope Maine’s OK.

You hope Takahashi can do something like this again though you’d prefer the occasion not present itself the same way.

You hope somebody can step in for K-Rod should a game need saving Saturday.

You hope the Braves continue to forget the finer points of the infield fly rule.

You hope Ike gets so proficient at homering to extremely deep right-center that the Citi Field engineering corps has to double-deck the BSB.

You hope triples continue to explode from the middle of the batting order now that it contains a certified leadoff man.

Finally, you hope whatever runners the Mets leave on base, they’re not left on third with less than two out, because that’s opportunity wasted, and the Mets really can’t afford much, if any, of that.

Like ribbon boards, sacrifice flies aren’t inherently interesting. But when they weave their way into one night’s successful narrative, you just have to take notice.

by Greg Prince on 23 April 2010 4:12 pm Welcome to Flashback Friday: Take Me Out to 34 Ballparks, a celebration, critique and countdown of every major league ballpark one baseball fan has been fortunate enough to visit in a lifetime of going to ballgames.

BALLPARK: Comiskey Park (New)

LATER KNOWN AS: U.S. Cellular Field

VISITS: 2

FIRST VISITED: July 31, 1994

CHRONOLOGY: 11th of 34

RANKING: 27th of 34

New Comiskey Park may have ultimately suffered from bad timing, but it represented good timing for me. It had the temporal luck to be open and hosting a ballgame at the outset of a four-day span in which Stephanie and I set out to see three baseball games in three different baseball facilities. A trip like that requires pinpoint precision, and we benefited from it: New Comiskey on a Sunday, County Stadium on Monday, Wrigley Field on Wednesday. It became known in family lore as Chicago-Milwaukee-Chicago.

It’s probably not that rare a triple play to pull off for the ballpark-ambitious, but in the summer of 1994, we needed to have our timing down, for if we were to try this, say, two weeks later, we’d have been severely out of luck. The baseball strike that killed one season’s World Series and wrecked another’s Spring Training went into effect a little more than a week after we executed C-M-C to perfection. It was no fun to have no baseball to watch from August 12 on in ’94, but at least we had our memories of the baseball we immersed ourselves in from July 31 through August 3.

Memories being what they are, New Comiskey was going to have a tough time competing, both for my affections and aficionado acceptance. That’s where bad timing came in. New Comiskey showed up a year before Camden Yards. Camden Yards changed everybody’s idea of what a ballpark could be. New Comiskey came off, after a year as the new kid on the block, as the last dinosaur out of town. It had opened as a stadium that by not being multipurpose; by installing grass; and by including a few touches toward the nostalgic. figured it was a legitimate step up from the concrete circles of ’60s and ’70s.

Camden Yards blew that equation out of the water. State-of-the-art changed from 1991 to 1992. Oh, so THAT’S what a ballpark can be was the consensus across America. And if Baltimore was the Ball Ideal, then what was left on the South Side of Chicago?

Not Camden Yards. In a nutshell, that was half of its problem. It wasn’t human-sized. It wasn’t charming. It didn’t integrate itself into the fabric of its neighborhood or its city. Nobody much thought about this stuff before Camden Yards, certainly not me, but now I was acutely aware of it. I’d read up voraciously on OP@CY since it opened and in April of ’94 I made my first pilgrimage there. It meant New Comiskey was not the ballpark you wanted to discover after Camden Yards.

New Comiskey also suffered in comparison to Old Comiskey. It was impossible for me to shake off the “New” distinction, because Old Comiskey, which thrived for 81 seasons in what was now New Comiskey’s parking lot, was the real thing. I spent one evening there five years earlier and it made quite an impression. It may or may not have been falling apart as White Sox ownership claimed (while they demanded a new luxury-laden stadium, lest they vamoose to St. Petersburg), but damn was it real. This Comiskey, the one that devoured its predecessor, couldn’t help but feel synthetic.

For example, Comiskey’s arches represented legendary ballpark architecture. New Comiskey attempted to mimic them, but the fakery felt Disneyesque, and not in the seamless fashion Disney makes Disneyesque work in its theme parks. On paper, trying to recreate the arches probably seemed like a respectful or at least comforting nod to the Comiskey of yore. In the corporate present, however it served only as a reminder that Progress had just kicked the living daylights out of the Past.

So if New Comiskey wasn’t Comiskey and it wasn’t Camden, what was it? It was too high. That’s what we’d heard going in, and we weren’t disavowed of the notion once we left. Capacity was in the low 40,000s, but the upper deck negated any notion of intimacy. Original Comiskey, by dint of posts, kept the upper deck within striking distance of the field of play. Cantilevering (one of those words I learned when I was having my ballpark-consciousness raised in the early ’90s) removed such obstructions, but there was now the chance your view of the game would be blocked by a bird. The last row of the last tier the old park, I’d read, was closer to home plate than the first row of the last tier of the new park. I believe it.

No kidding, it was high and steep up there. I was a veteran of the Shea upper deck, but that was a dash up the steps next to New Comiskey. Bring water. Bring a guide. Bring oxygen.

Maybe don’t bring your wife on a 90-degree day, particularly when she is averse to glaring sun and has left her Mets cap in New York. (One adjustable White Sox cap never to be worn again: $15.)

The happy part of this, I suppose, is the park was crowded and their fans were enthused by the home team’s play. The White Sox were in first place and headed for the playoffs for a second consecutive season…except there would be no playoffs in 1994, darn it. It was widely known on July 31 that baseball was likely headed for doom — beloved organist Nancy Faust played Christmas carols that morning, which was something she usually did on the final home Sunday of the year. The White Sox would be on the road the following weekend. This was, in essence, their Closing Day. Consciously or not, no matter how far up they sat (and it was remarked again and again by the locals who had climbed to our vicinity that “boy, this is high”), they were into their team and their game.

That’ll make any ballpark feel genuine.

An added element to the excitement was the prospective “showdown” between arguably the sport’s two top young players, Frank Thomas of the White Sox and Ken Griffey of the Mariners. I had never seen either and, by the end of the day, I still hadn’t seen Griffey. He was given the day off, his first and only DNP of 1994. Thomas went 1-for-2, but the real star of the day was Lance Johnson, who hit a game-breaking grand slam in the sixth. When the same Lance Johnson became a free agent following the 1995 season, I insisted the Mets get him based almost entirely on that swing on that one hot Chicago afternoon.

The White Sox won easily. We cooled off eventually, about the time we were back in our downtown hotel room watching ESPN rerun the Hall of Fame ceremonies — it was the same day Bob Murphy received the Ford C. Frick Award in Cooperstown. Unlike Murph, New Comiskey wasn’t great, which wouldn’t have been a concern before Camden and the destruction of true Comiskey, but it did have baseball on a Sunday. By the middle of August, such simple summer pleasures would be unavailable to us.

***

A second visit materialized in 1999. Also hot, but a night game. I was in Chicago on business and got in touch with my friend Jeff, who didn’t much care for the White Sox (Indians fan by birth, Cubs fan by proximity), but a ballgame was a ballgame. This was a Monday night, and at New Comiskey in late of July of ’99, upper deck seats were five bucks apiece. “But I’m not sitting in the upper deck,” Jeff announced with uncharacteristic entitlement. He explained to me that these days, with the White Sox no longer exciting too many people, they weren’t about to kick you out of seats you didn’t pay for. Quite casually, I followed his lead into perfectly lovely and unoccupied field level seats behind first base. No way we could have done that at Shea.

It was a better view down there for sure. It was actually quite nice. A little generic, but not at all overwrought as it had seemed five years earlier. They’d been making improvements at New Comiskey in response to the generally negative reviews it had gotten and would continue to renovate well into the next decade (best improvement: the addition of a 2005 world championship banner). This time I had a chance to explore the lower concourse which was mall-ish, but not necessarily offensive. There was a neat little museum tucked away and an adequate slice of pizza to be found at the Old Roman stand. You could even see where Nancy Faust worked her magic.

If the only New Comiskey I saw was the New Comiskey I saw the second time around — from ground level, beneath the luxury boxes, removed from the incline above — I might have thought less harshly of it all along. And if I were judging it from one particular at-bat, I’d think it was greatest ballpark ever.

It’s the bottom of the second. Pat Hentgen is pitching for the Blue Jays. Leading off the inning for the White Sox is Carlos Lee, a rookie of some promise. As someone chronically unfamiliar with the American League, he is mystery to me. Yet he is about to become a household word, for Carlos Lee fouls one back to the first base side.

And it lands in our section.

And it rolls under a seat to my left, one row in front of me.

And the guy sitting in front of me reaches for it, but he can’t grasp it.

And I reach for it. And I do grasp it.

FOUL BALL! I GOT A FOUL BALL!

It was the only foul ball I ever got at a major league game. I had been to 160 games at Shea to that point, but never got a damn thing. The closest I’d ever come, actually, was at Old Comiskey ten years earlier.

You’d think this would cause my affection for New Comiskey to soar to upper deck levels, and in a way it did. Nevertheless, the image of picking up the foul ball is countered by the other image I maintain from that evening. It was generated when Jeff and I were making our way to the ticket windows where we were about to spend five dollars on seats we wouldn’t sit in. It was in the parking lot. I hadn’t seen it in 1994.

“Look,” he said.

There it was, a quiet five-sided marker.

COMISKEY PARK 1910-1990 HOMEPLATE

It was flanked by two batter’s boxes. Stemming from them were two white lines that stretched out forever. Progress won. Here’s where the battle ended.

The Carlos Lee foul ball still makes me smile. The Comiskey Park marker, however, can still move me toward tears.

by Greg Prince on 23 April 2010 2:55 am In case you haven’t turned on ESPN in the last week, the NFL Draft is in progress. It began Thursday night and it runs through late June. Makes for captivating theater, as in you’d have to hold me captive to get me to sit inside Radio City Music Hall for all 481 rounds of it.

Correction: I’m told there are actually only ten rounds and that the NFL Draft takes only three days to conduct. My mistake. That’s not overlong at all.

If the NFL Draft has given us anything besides Mel Kiper, Jr. over the years, it’s the phrase “Best Available Athlete”. It’s what football teams say they went for when they didn’t get the player their fans and media were clamoring for. It’s a nice catch-all and it means, from what I can tell, absolutely nothing. You get a look at these kids? They all appear to be comparably athletic. One would hate to think NFL general managers and their lieutenants plot hour after hour in their war rooms (as they are so charmingly called) only to blow their pick on the best available plumber.

Though if you get a tough clog, you’ll look at that hulking defensive end you traded up for and think, “This place is a mess. I wish we had gone with the plumber instead.”

It’s easier in baseball. Their draft is conducted in a cave somewhere in Secaucus while the season’s in progress, leaving relatively few to give it more than a moment’s attention when it rolls around every June. Major League Baseball tried to glamorize it in 2009. You know how? By literally holding it somewhere in Secaucus. Last year, the only player the average fan had ever heard of going into the draft was Stephen Strasburg. The year before, the only player the average fan had ever heard of going into the draft was…uh-huh, exactly. As for phrases like Best Available Athlete, baseball doesn’t waste those on draft picks.

That’s because everybody knows the Best Available Athlete in a given baseball game is Johan Santana.

Johan has speed, as demonstrated by the way Thursday night’s game fairly zipped along while he was pitching out of tight spots, and dragged unconscionably (yawn 3:16) after he left.

Johan has strength, as evidenced by the way he carries the Mets on his broad shoulders until they finally (after 17 consecutive innings of nonsupport) score a run for him.

Johan has size, too, particularly in the stature department. Tom Gorzelanny may have been matching him zero for zero there for a while, even threatening to no-hit the Mets — call it the Jaime Garcia effect — but ultimately Johan will tower over the competition.

Johan Santana also presumably scores well on the Wonderlic Test, the examination the NFL gives its prospective draft picks to determine mental agility. For example, Johan was smart enough to take the Mets’ money two years ago, and no matter what certain bored columnists conjure in their own addled heads, that was a pretty agile move right there.

The Mets’ other available athletes wouldn’t be bested, either, Thursday night. Their 2008 top pick and 2010 freshman sensation I.B. Swinger racked up three more hits. Former sandwich pick David Wright (who is said to be quite fond of peanut butter, honey and jelly) fulfilled every schoolboy’s dream and tied Ed Kranepool’s career total for doubles when it couldn’t have counted more. The heretofore forgotten closer Francisco Rodriguez came in early to slam the door not three but five times. Most impressively and encouragingly, he tickled the strike zone to end the eighth, leaving Chicago’s potential tying runs on base where they would wither like early-season ivy.

The Mets, for all their deserved reputation as tackling dummies, were the clearly best available athletes in this set of downs against the Cubs. Gorzelanny — along with the Met pen prior to K-Rod — may have kept the series finale uncomfortably close a little too long, but fortunately for us, the Cubs are as brutal to watch as the NFL Draft. Doesn’t matter, though; three out of four from anybody is a selection we’ll make any day.

As for tonight against the Braves, John Maine is on the clock.

Thanks to Dave Murray for dizzying up his FAFIF t-shirt earlier this month in Jupiter, Fla. Read all about it at Mets Guy In Michigan. If you want to look sharp standing up straight or staggering to the ground, you can get your own shirt here.

And yes, Faith and Fear in Flushing: An Intense Personal History of the New York Mets is indeed available in paperback, featuring an all-new epilogue regarding the Mets’ first season at Citi Field. It’s been spotted at several New York area bookstores and is available to order via Amazon and Barnes & Noble. Mets fan and film buff Vince Keenan gives it two thumbs up here.

by Greg Prince on 22 April 2010 1:18 pm Violinist Issac Stern played great music. Writer Isaac Bashevis Singer wrote great fiction. First baseman Issac Benjamin Davis made a helluva catch on a foul popup in the first inning of Wednesday’s otherwise desultory Met loss.

All these Isaacs were blessed with a talent for doing something most people can’t. Stern was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom; Singer was a recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature; Davis — better known as Ike — is our unanimous choice for best Met called up from the minor leagues in the last week, no offense to Manny Acosta or Tobi Stoner. He is also, by Alex Belth’s reckoning, the first major league ballplayer to share a name with a Woody Allen character. In Manhattan, Ike Davis is a middle-aged comedy writer dating a high school girl.

In Queens, Ike Davis is barely five years out of high school and en route, we pray, to becoming — apologies to Mr. Singer (Isaac Bashevis that is, not Annie Hall‘s Alvy) — the Magician of Flushing.

Also, each of these Isaacs, it turns out, is Jewish. Issac Stern and Isaac Bashevis Singer are members of the Jewish-American Hall of Fame. Isaac Benjamin Davis, early signs of a beautiful swing notwithstanding, probably needs a few more plate appearances to merit Hall of Fame consideration of any kind. The similarities among our trio of Issacs end there for now.

When I say “it turns out” Ike Davis is Jewish, that’s because I had only the barest inkling that was his background. I don’t generally give any thought to Mets’ backgrounds. Tom Seaver was in the booth for a half-inning last night. It occurs to me I’ve never known or wondered about Tom Seaver’s religion. Seaver religiously threw strikes like nobody else, which meant I was a practicing Seaverite from the time I was old enough to know right from wrong and left from right. If Seaver advertised his faith when I was seven, I probably would have petitioned my parents to convert to whatever that was.

The bare inkling I had about Davis came because our blog (like most blogs, I suspect) comes equipped with an internal information page that tells us, among other things, what kinds of searches people do that lead them to click on a link to us. On and off for a couple of months, apparently, a few people per day were going on Google and typing in “Ike Davis Jewish?” and finding FAFIF. We had never written anything about it, but we had mentioned him, and deep within our sidebar, under the heading “Extreme Baseball,” is a link to a site called Jewish Major Leaguers. That’s search engine alchemy for ya.

I noticed this, but I never much wondered. We get those searches from time to time for David Cone (not Jewish), Mike Jacobs (not Jewish, despite the best efforts of the 2006 Marlins’ promotions department) and Sean Green (wrong Green), among others. Not having seen Manhattan lately, the name “Ike Davis” didn’t necessarily resonate as Jewish or not Jewish. It never occurred to me before learning otherwise that “Shawn Green” was a Jewish name. Or, come to think of it, “Dave Roberts,” the last Jewish Met, from 1981, to predate Green, who arrived in 2006.

There’s an intensely interested audience for this information, however. Jewish baseball fans are almost always interested in knowing if a baseball player is also a Jewish baseball player. We’re not gonna not root for a guy because he isn’t Jewish — and we’re not necessarily gonna root for a guy because he is Jewish (did you hear any discernible vocal support from any demographic for Scott Schoeneweis during his two-year stay at Shea?), but it’s just somehow nice to know. It doesn’t make any of us who aren’t particularly athletic any more handy with a bat, but it gives us the idea, somehow, that it’s not so odd that someone who is Jewish can be a very sweet swinger.

Nobody told me I couldn’t be a professional baseball player because I was Jewish. My complete lack of skills told me that. But you grow up, you’re aware of who you are from a religious or cultural (or both) standpoint, you become aware there are very few who share that segment of who you are in the big leagues and you begin to accept that it’s very unusual to almost unheard of to find Jewish ballplayers.

Jewish violinists? There’s Isaac Stern. Jewish writers? There’s Isaac Bashevis Singer. Jewish ballplayers coming through the Met system?

There was nobody for decades until Isaac Benjamin Davis.

It didn’t matter, because Shea Stadium was your temple and Metropolitan-American was your true ethnicity, but, like I said, it’s nice to know. I only found out the other day about Davis when that stream of searches began to pick up. It was supplemented by cautiously joyous e-mails: “Did you hear…?” “Is it true…?” Thanks to Google, it didn’t take much detective work to track down this February tidbit from Pittsburgh Jewish Chronicle columnist Jonathan Mayo, delivered via New Jersey’s own Kaplan’s Korner:

I asked him in an email if there are any promising Jewish prospects to keep an eye on. His reply: “Ike Davis, the Mets’ first-round pick from 2008. [Former Yankees pitcher] Ron’s kid (mom is Jewish). He told me he’s not religious at all, but that’s ok. He’s not running from it, either.”

“He’s not running from it, either.” Why he would in 2010 I don’t know. If Ike Davis doesn’t deny being related to a Yankee, why would he eschew any of his heritage?

But seriously, this is nice to know. Going with the most generous delineations possible, the Mets have had nine Jewish players through the years — Green, Roberts, Schoeneweis, Joe Ginsberg, Norm Sherry, Greg Goossen, World Champion Art Shamsky, Elliott Maddox and David Newhan — but save for Goossen, never one who commenced his career as a Met (who, ten years after he broke in was indeed, per Casey Stengel’s projection, ten years older than he had been). So now, with Ike Davis, not only do we have enough for a minyan, we have one who is homegrown.

That’s only important in the sense that it’s always better to have a player who holds the promise of getting better, whatever his background. Shawn Green may have been a great Jewish ballplayer, but he peaked as a Blue Jay and Dodger. When it came to his Met days, he was a member of a vast and nonsectarian group of late-career acquisitions whose congregation was clearly situated Over The Hill (their rabbi: George Foster; their cantor: Carlos Baerga; the president of their men’s club: Jim Fregosi). The reason we’re liking Ike is he’s a Met who we can still rightly hope will become a great ballplayer. A great Met ballplayer. And if he’s Jewish while doing it, that’s nice, too.

Maybe more than a little nice for some of us.

by Greg Prince on 21 April 2010 12:00 pm [T]he only name anyone sings in the Yorkshire ale houses, raising their stinking jars to their stinking mouths, is Brian Clough. Brian Clough über-fucking-alles! Understand?

—Brian Clough, The Damned United

I don’t know when it will be 2006 again for the Mets. I don’t know when we’ll have a regular season in which we praise our lads to the high heavens from the Third of April to the First of October, from the top of the order to the pitcher’s spot. Nothing was ever wrong and all was always right a mere four seasons ago.

That’s a gauzy distortion of real time history, of course. We fretted everything and everybody when the season began and our ship was taking on anxieties by the nautical ton as it wound down, but there was a golden period somewhere in the middle when all was bright, all was clear and, above all, there was Jose.

Jose! Jose! Jose!

In the late ’90s, early ’00s, my friend Joe and I would go to random Saturday games, by no means seeking the same section every time, yet we always seemed to wind up in proximity to a group of fans who would break out into sing-song chant with no apparent baseball provocation. I never could make out what they were saying, singing or chanting, but it sounded more appropriate to one of those English football clubs whose games bars in Woodside advertised on their outdoor chalkboards than it did to whatever was going on at Shea.

Then one night in June 2006, after Jose Reyes had rounded first on a single that followed a homer, a double and a triple to therefore create a cycle, I heard it again through the TV. That chant or song. The English football guys from years before. What were they chanting/singing exactly?

“Olé”?

“Oyez”?

“Oy vey”?

No, it was Jose!

Jose! Jose! Jose!

As the animated man in the Guinness ads of the time would have put it, “BRILLIANT!”

I’ve never learned from whence Jose! was born. Was it a Shea scoreboard thing that actually caught on? Was it fan-generated? Was it the lads from the Mezzanine who used to congregate in full throat behind Joe and me? Don’t know where it came from, but it wasn’t going anywhere. Only Jose was going somewhere: to second or third most nights. Jose was going from “could be” to “is,” as in Jose is the Mets’ catalyst, the Mets’ ignition switch, the Mets’ lifeblood. Jose is the best leadoff hitter in the game. He is atop our lineup and we are on the top of the world.

Jose!

Jose! Jose! Jose!

Jose!

Jose!

As happens with every year once it becomes the past, 2006 gets harder to remember fully and accurately. The bright period from then is generally eclipsed by the gloomy ending now. What had been a storybook season became prologue for a dark and stormy next three chapters. Jose himself would have his moments across those pages — as would Jose! — but the resonance would literally and figuratively diminish. By 2009, Jose/Jose! took an involuntary extended sabbatical.

Met life, regrettably, went on without him.

Eleven days ago, a still young fellow wearing No. 7 stepped in to lead off a game for the New York Mets for the first time in a long time. He looked familiar, but his carriage struck no chord. The No. 7 I remembered was swift and sleek and above all sunny. This one was grim and attempting without success to gain his bearings. I kept an eye on him for the succeeding week and change. Still not quite right, still not quite what I remembered. Silence and glumness sat in his wake.

Then last night, on the radio, in the car, in the bottom of the second, joined in progress…Carlos Zambrano has already allowed one runner but he has two outs and the pitcher up. It’s Mike Pelfrey, with the Big Pelf-sized strike zone. But Zambrano finds it not big enough and walks his opposite number. That’s two on, meaning the order turns over to the leadoff hitter.

It’s Jose Reyes, mired in what is, for all intents and purposes, an 0-for-’10 slump. Gosh, I think, while making a left turn toward home, if he’s ever going to break out, this would sure be an ideal time to do it. The count goes to three-and-one. A walk wouldn’t be the worst thing, but, you know…

With that, there’s a swing and a drive to left and — yes! It’s in the gap! Here comes Pagan from second. Here comes Pelfrey from first (Christ, don’t get hurt on a play at the plate). Is Mike gonna score? He is, which is great and all, but now I want to know what I really want to know.

And then I know because Howie Rose tells me: Jose Reyes slides into third with his first triple of the season.

Jose Reyes with a triple. The 74th of his major league career, more than any Met. The first he’s collected since April 29, 2009, almost a year. There had been triples at Citi Field since then, but none by Jose Reyes, he for whose bat and legs and particular talent for creating triples this park was designed. Earlier, in the first, there had been a single. Later there’d be two more, plus a stolen base. But for now there was a triple. A Jose Reyes triple.

I don’t know how much or even if they were singing at Citi Field. But alone in the car, I sure as hell was.

by Jason Fry on 21 April 2010 1:38 am Watching Mike Pelfrey obliterate the Cubs and the Mets hitters do enough, I felt something I hadn’t felt since Opening Day. Or rather, I noted the absence of something.

Panic.

In 2009, a late two-run lead for the Mets was called foreshadowing. In the first week of the season it was a fantasy, as the Mets weren’t much for leads. Last night, it felt like a two-run lead — a number you’d like to see larger, but still proof against disasters of the lightning-strike variety. Could this still be the Mets? Could this still be me? Not long after I started thinking about this, Fernando Tatis refused to go gentle into that good night, slamming a pinch-hit home run over the left-field wall whose height has perhaps victimized him more than any other Met. We were four runs up, that felt safe, and it was.

And yet the Mets’ position remains precarious — in fact, it grew more precarious as the night went on. Ryota Igarashi slipped on the grass, strained a hamstring — SNY showed it contorting sickeningly in super slo-mo, which I’d like to ask them to never do again — and is headed for an MRI tomorrow. (Igarashi told the Times through an interpreter that “I felt the numbness develop,” which would be an excellent title for a book about being a Mets fan in the late Aughts.) And word came that Carlos Beltran had been to the doctor in Colorado and not pronounced fit for anything except more rehab. The idea of Beltran returning in May just evaporated; June is a place-holder, and here’s betting the All-Star break creeps into conversation before too long. Meanwhile, David Wright is being eaten alive by sliders and Jeff Francoeur is once again swinging enthusiastically at bags of peanuts he spies being tossed in the Excelsior level.

Given all this, why wasn’t I panicking? Because Pelfrey’s new splitter looked superb again, and you could see its owner seemingly growing more confident by the inning. (At one point Pelfrey was smiling and bantering with the umpire and/or catcher, and I barely recognized him.) And because after nearly a year of injuries, inactivity, questions, whispers, mysteries and troubles, Jose Reyes finally got to fly around the bases again like a giddy colt. His pregame interview with Kevin Burkhardt was oddly vulnerable for a professional athlete, so it was immensely reassuring to immediately see the old Jose on the basepaths — reassuring for us, but probably far more so for him.

An MRI. No Beltran doing much of anything. Wright and Frenchy looking lost. Bay still ice cold. And yet all of a sudden I can feel myself relax. I doubt that’s justified, but I’m not inclined to talk myself out of it.

|

|

Standing there on the street, my neighbor drew out one of the bags from the stack on the luggage cart and opened it. Inside was a stack of yearbooks. The 1961 Yankees were on top. Farther down in the stack I saw the Jets logo, and then a familiar sight: Tom Seaver smiling behind assembled baseballs. Mets, 1975. Then a Seventies Yankee, swinger’s locks flying, about to crash into a catcher at home plate. Then Mr. Met in a tri-cornered hat. 1976 — I’d had that yearbook, when I was a kid.

Standing there on the street, my neighbor drew out one of the bags from the stack on the luggage cart and opened it. Inside was a stack of yearbooks. The 1961 Yankees were on top. Farther down in the stack I saw the Jets logo, and then a familiar sight: Tom Seaver smiling behind assembled baseballs. Mets, 1975. Then a Seventies Yankee, swinger’s locks flying, about to crash into a catcher at home plate. Then Mr. Met in a tri-cornered hat. 1976 — I’d had that yearbook, when I was a kid.