The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 21 January 2010 6:19 pm In the three decades since Fred Wilpon entered our consciousness, oftentimes the best thing about the ownership group he’s played a major part in running was who he was and who they weren’t.

First, it was outstanding that Doubleday & Company, Inc. — 95% majority owners of the New York Mets as of January 24, 1980 — wasn’t a remnant of the original Payson operation. Joan Payson may remain a beloved figure in team history, but the mess she left behind after she died in 1975 decayed quickly. Her chairman, M. Donald Grant, ran the organization into the ground before running himself out of town. Her daughter, Lorinda de Roulet, took over and all but threw a shroud over the ground into which the Mets had been run. Charles Shipman Payson, Joan’s Red Sox fan husband, showed no interested in upkeep and parted with not a dime in that direction.

By appearing competent and willing to invest, the Doubleday group, which included 5% stakeholder Wilpon, couldn’t help but win goodwill if not a whole lot of ballgames at first. Nelson Doubleday was installed as chairman, Wilpon became president and they left the prospective empire-building to Frank Cashen. They bought a ballclub, but they also bought time.

In doing so, Doubleday and Wilpon were not George Steinbrenner. That was also outstanding to consider in the early and middle 1980s. Back then, being a Steinbrenner had almost no redeeming features. The principal owner of the New York Yankees spent and blustered and fired but he hadn’t won anything for a while. He kept blustering nonetheless, and while it was entertaining, it didn’t win him or his club kudos or titles. The Mets way, the Doubleday/Wilpon way, was the way to go. You saw them hold a press conference when they bought the club and, after that, you basically never heard from them again. Nobody minded. It seemed classy and professional and appropriate in contrast to the hyper hands-on Steinbrenner, whose approval ratings had been heading steadily downhill since the day he took out a newspaper ad apologizing to New Yorkers for not winning the 1981 World Series.

Doubleday didn’t seek publicity — he was not to be found in either the clubhouse celebration that followed the 1986 championship or the parade up Lower Broadway the next day. Wilpon’s profile wasn’t all that high either. He may have accepted the Commissioner’s Trophy from Peter Ueberroth on October 27, but he wasn’t writing any columns in the New York Post that month. George Steinbrenner, however, was. (What the hell, he had nothing else to do.)

Less than three weeks after the Mets defeated the Red Sox, the composition of ownership changed. Corporate machinations dictated Doubleday & Co.’s publishing interests be sold to a German concern. They weren’t buying the Mets. Nelson Doubleday and Fred Wilpon, who were not associated in any meaningful way until 1980 (Wilpon wanted to purchase the Mets but couldn’t meet Charles Payson’s price without Doubleday coming aboard), became 50-50 partners. The transition appeared seamless to the outside world. Doubleday and Wilpon were the names with which Mets fans were familiar, so when Sterling Doubleday Enterprises was formed on November 14, 1986 in an $80 million deal, it didn’t seem to represent a sea change à la the sale of January 24, 1980.

“Fred and I have had a good partnership for seven years,” Doubleday said in the Mets’ 1987 media guide, “and I know we will continue to have a good partnership. “There will be no revolutionary changes in the control of the Mets,” Wilpon agreed in the same introductory article. “Operations will continue just as they have since 1980.”

It didn’t play out that way. We still didn’t see or hear much of Doubleday and Wilpon for the next few years, but behind the scenes, as documented in Andrew Rice’s thorough 2000 New York Observer examination of their relationship, things were changing. By then it was common knowledge that Wilpon and Doubleday were partners in name but not in spirit. When they showed up in the clubhouse to jointly receive the Warren C. Giles National League Championship trophy, it was the first time in a while they had been seen together in public.

As Rice explained a decade ago, Doubleday wasn’t happy that Wilpon became his equal partner in the first place. Wilpon, according to Murray Chass, writing in the Times in 2001, took advantage of a first-refusal clause in 1986, one that “Doubleday apparently had been unaware of”. More friction developed with the more authority Wilpon gained/usurped. A turning point in the relationship, wrote Rice, came as the wreckage of 1993 piled up in Flushing. Cashen was gone, the Mets were in disarray and Wilpon stepped up to publicly accept responsibility for a team that was dismal on the field and hopeless off it. That summer — Bobby Bonilla threatening Bob Klapisch; Vince Coleman tossing lit firecrackers at children; Bret Saberhagen spraying bleach on beat reporters — was the Met equivalent of August 1974 in the Nixon White House. There existed a perception no one was in charge of the asylum. Fred Wilpon said, in essence, “I am.”

Whether it was a role he took on with reluctance or relish (and he’s been described as possessing an inner Steinbrenner), Wilpon emerged bit by bit as the man in charge. There was no unquestioned baseball authority figure on the premises — Joe McIlvaine had succeeded Al Harazin who had succeeded Frank Cashen, but neither Harazin nor Joe Mac was vested with the degree of autonomy Cashen held. And Doubleday? The mid-’90s not a great period for him, as Rice recounted in 2000.

[I]n the spring of 1994, a book about the ouster of baseball commissioner Fay Vincent by a group of owners led by Bud Selig and Jerry Reinsdorf quoted Mr. Doubleday, a Vincent ally, telling league presidents Bobby Brown and Bill White: “It looks like the Jewboys finally got you.” A former employee told Newsday that Mr. Doubleday had said similar things in his presence, but only “when he was drinking.” Mr. Wilpon, who is Jewish, stood up for Mr. Doubleday, saying: “It’s not like Nelson to talk that way.”

After that, one person familiar with the team said, Mr. Doubleday disappeared from the scene and Mr. Wilpon took charge, with a more hands-on approach. He has installed loyal subordinates who have frequently come into conflict with executives loyal to Mr. Doubleday.

It was Fred Wilpon, not Wilpon and Doubleday, who held the notorious 1997 press conference in which McIlvaine was dismissed (while the Mets were enjoying their first winning season in seven years) and assistant GM Steve Phillips was elevated. It was, however, Nelson Doubleday who was seen as coming out of hibernation to push Phillips toward trading for Mike Piazza in 1998. Doubleday promised he’d involve himself more in Met matters from there, but was generally unseen around Shea after Piazza was re-signed that October. Wilpon, meanwhile, had begun planning for a replacement to Shea Stadium, a goal not shared by Doubleday. On the road to the 2000 World Series, while real estate wizard Wilpon was working on making what would become Citi Field a reality, Doubleday came out in favor of renovating Shea.

Not communicating and not agreeing on fundamental matters like “where are we gonna play?” was no way to run a ballclub. Despite the Mets winning a pennant in this apparently dysfunctional atmosphere, something had to give. After a rumored sale to Cablevision fell through, it was Doubleday who gave in, selling his half of the Mets to Wilpon for approximately $135 million on August 23, 2002.

Was the best part of Wilpon owning the majority of the Mets that he wasn’t Doubleday? Or did concentrating all power in one man and, eventually, his son, send the Mets once more on the road to what feels like ruin?

It can’t help but be a hypothetical question. There’s no definitively answering whether we as Mets fans would have been better off with a continuation of the evolving Wilpon-Doubleday synergy, no matter how weird it must have been to work around. There’s no telling whether we would have been better off if it was Doubleday who bought out Wilpon, even if Piazza is often credited to his side of the ledger. Nelson did not present the steadiest persona in his later years as co-owner. Based on its record with the Knicks and Rangers, I think we’re all glad Cablevision never bought Doubleday’s piece of the Mets; if he’d have sold to Charles Dolan, how can we imagine the best out of anything else Nelson Doubleday might have done to/for the Mets? But what if somebody or some other entity had bought the team?

If any of these alternate realities had come to pass, and the Mets weren’t primarily the Wilpons’, would the Mets be in better shape at this moment?

The truth is the Mets were in yet another of their periodic humiliating death spirals when Wilpon bought out Doubleday. A month hadn’t gone by when the underachieving 2002 Mets went from bad to stupid amidst allegations of marijuana use and Bobby Valentine’s weird reaction to them — affecting a stoner pose during a press conference addressing the pot revelations. The stupidity only deepened when Fred Wilpon, with nobody holding him back, fired Valentine as manager and hired Art Howe, alleging Art Howe “lights up a room”. Valentine may have pretended to light up a joint, but the other guy lit up absolutely nothing. Outside of Howe’s immediate family, nobody ever saw in Howe what Wilpon somehow detected.

The Art Howe decision, the lowballing of the very available Vladimir Guerrero, the infamous “meaningful games in September” soundbite and the trade of Scott Kazmir (whoever’s call that was) all fed the perception that the Mets were, by 2004, back where they were when Fred Wilpon injected himself into public view in 1993. They were a mess.

Then they weren’t. Omar Minaya became the general manager, was given “authority and autonomy” and the Mets improved. Fred was the owner, but Omar served as the man in charge, at least until last summer when Minaya, in the middle of a desultory campaign, put his foot in his mouth when turning the Tony Bernazard story into the Adam Rubin story. Omar stopped appearing regularly in front of cameras and microphones. The owner was taking a more active role, but by now it was Jeff Wilpon, Fred’s son, acting in that capacity. Fred’s dream was opening the Ebbets Field lookalike in what had been Shea’s parking lot. It got done. Once the Mets were playing inside it, it would be Jeff who would absorb the criticism when the organization would inevitably do strange things like call out Carlos Beltran for getting his knee fixed. Now it’s Jeff who’s more than ever the man in charge. Fred didn’t want the franchise being sold to Cablevision or anybody because he wanted that. He wanted the Mets to stay in his family.

It has. Fred is still chairman, but it is increasingly Jeff’s show. We’ve lived and rooted under Wilponian influence for thirty years and, unless there’s a momentous change of heart or turn in financial fortunes, we’ll have countless more years of it. Jeff Wilpon is the chief operating officer of the New York Mets. He’s not going anywhere.

Which means what for us, exactly? In recent months, and for much of the last year, really, I don’t think a day has gone by when I haven’t read or heard somewhere the suggestion or demand by a Mets fan that the Wilpons sell the team. The catalogue of grievances is varied as it is long. The bottom line seems to be that the Wilpons, personified mostly by Jeff these days, are a long-term impediment to our happiness. They are not enabling our enjoyment of our favorite team; they are, instead, exacerbating our aggravation from it by their accumulated actions and nonactions.

I wouldn’t necessarily disagree with that assessment, but I have to ask, in all sincerity, what do you want from the owners of your ballclub? I mean that literally: what do you want from them?

When things are going well, we don’t toast the merits of our club owners. We just accept that things are finally going the way we want and, perhaps, we hope nobody screws things up down the line. Three years ago, even with the 2002-2004 track record a matter of public record, the Wilpons were not a continual object of our collective scorn. I doubt any of us gave them much thought at all, save for special occasions. The man they put in charge had transformed a fourth-place finisher into a division winner and projected perennial contender in just two years. They gave Omar Minaya the resources and Minaya produced instant results.

The other night, SNY reran the 2006 division clincher. I watched the ninth inning and clubhouse celebration yet again. It was the last massive joygasm Shea Stadium ever experienced. We won something big, something we hadn’t won since 1988. Nobody who wore a Mets uniform or made a Mets decision was considered suspect then. Everybody was part of the team that night. If Minaya was awesome, so, by implication, were the guys who employed him.

(Eerie shot by SNY’s cameras while the Mets indulged in their group hug: the despondent opposing manager soaking in the celebratory scene, wondering when he’d get a chance to lead his clearly irrelevant team to this kind of revelry. The manager was Joe Girardi. And, come to think of it, the clinched-against club was the Marlins.)

That September 18, 2006 was, to date, the high point of the Minaya Mets underscores that things haven’t gone to plan since. We won the NLDS, lost the NLCS painfully and then failed to return to postseason play. Three years ago today you could not have convinced most Mets fans — and certainly not me — that this would be our three-year fate. If you had solicited opinions on Fred Wilpon or Jeff Wilpon in the winter of 2007, you might not have won an unqualified endorsement of their savvy, but you likely would have given them a benign or at least begrudging tip of the cap for getting us as far as we had come.

Ain’t nobody doing that now.

Is everything since the promise of 2006 evaporated the Wilpons’ fault? On one level, no more so than it was all their doing that the Mets gave us 97 wins, a division title and a playoff series triumph over the Dodgers. On another level, if we follow the Fred Wilpon 1993 model wherein he stepped up to take tacit responsibility for the behavior of his club and the image of his organization, then blame away. I don’t know if that’s fair, but the buck has to stop somewhere.

Which doesn’t tell us what it is we want from these Wilpons if a sale isn’t imminent or from their hypothetical buyers.

We want our team to win, naturally, but when they’re not doing that, we want to believe we’re not far from doing so.

We don’t want to be teased.

We don’t want to be let down.

We don’t want to be condescended to, I think.

We want to be listened to.

We want to be heard.

We want honesty.

We want hope until we can have results — but surely we want results.

We want value.

We want smarts.

We want good players.

We want likable players.

We want fun.

We want our collective interests taken to heart.

We want a lot.

We want what we want. We’re fans. We have an endless agenda when we’re not getting enough (or much) of what we want. We have no way of obtaining it for ourselves. That’s ultimately up to ownership. Ownership puts the baseball people in place. Ownership frames the business operations. Ownership is where the buck stops. We occasionally take out our firing frustrations on managers, general managers and club executives, but it is our owners who we expect to make things right as soon as possible and keep them right for as long as possible…with as few interruptions in service as possible.

That’s what we ask of the Wilpons as they begin their fourth decade running the Mets. Can we ever expect it?

by Greg Prince on 20 January 2010 9:52 am When acknowledging assumptions as mistaken, Bob Murphy philosophized, “That’s why they put erasers on pencils.” You can use the same device to erase all the 6-4-3’s you’d already scratched into your scorebooks for all the double plays Bengie Molina was going to hit into as the Met catcher this season. Scratch ’em out — Molina’s staying a Giant for less money than the Mets were offering.

Gosh, what a shame.

I’m sure I was missing the upside of Bengie Molina the whole time he was deemed a done deal for this and possibly next season. I know he produced 20 home runs in 2009 and 95 RBI in 2008. I understand he’s renowned for his defensive prowess and that he caught a pretty good staff the last two years in San Francisco, including the reigning two-time Cy Young winner Tim Lincecum. I know at the moment we’re improvising with an extra-large pillow strapped to a barrel instead of a catcher, but I’m not upset that Molina joins Yorvit Torrealba in a Never Met platoon at the backstop position.

I kept seeing the highlight package SNY kept showing in giving Molina updates and all I could think was, “This guy’s gonna kill one rally after another.” That’s a big assumption. It assumes the Mets were going to have rallies in progress, but I’m willing to go as far as to project a baserunner or two in 2010. What I couldn’t project was a 35-year-old (36 in July), plus-sized, righthanded hitting catcher slower than everybody on the field (and many in the stands) not grounding to shortstop with one on and one out. 6-4-3…6-4-3…I was already seeing it in my nightmares.

In a more optimistic would-be world, Bengie was going to whisper just the right calming advice to Mike Pelfrey, bark the perfect focusing command to Oliver Perez, figure out exactly how to keep Frankie Rodriguez from not giving up grand slams in ninth innings. We might miss all that. We might have to settle for the intermittently inspiring if mostly mediocre Omir Santos, wait impatiently for the development of young Josh Thole and spend more of a summer than we ever desired with Henry Blanco. Or maybe Chris Coste will earn his way onto the roster just so he can have a chance to chat with his beloved ex-Phillies teammates when they come to bat. Who will emerge as our regular starting catcher? Perhaps we’ll have to pretend to pay extra close attention to Spring Training to find out. Perhaps we won’t know for a while after that. Look at this way: Mike Piazza didn’t become our regular starting catcher until the 1998 season was almost a third over.

Now that’s looking at things with rose-colored glasses from behind a catcher’s mask. Until roster lightning strikes, however, the future’s so murky behind the plate, it’s gotta wear a chest protector.

by Greg Prince on 19 January 2010 2:52 pm Four for four: the Mets went 4-for-4 today. They resumed baseball activities with a bang.

The long-rumored, long-postponed, long-hidden Mets Hall of Fame announced its class for 2010, its first class in eight years, and it’s a doozy. It’s so good I have this feeling I’m writing one of those “wouldn’t it be nice?” fictional blog posts, except it really happened.

They’re inducting four Mets icons into the Hall come August 1…August 1, not April 1. No foolin’. To be enshrined are:

• Dwight Gooden

• Darryl Strawberry

• Davey Johnson

• Frank Cashen

I told ya 4-for-4. These are the four I would have put on my ballot had anybody asked me. These were the four I was planning on suggesting in the next righteous-fan piece that I’m happy to report I do not have to write. The Mets actually convened their Hall of Fame committee as promised and the committee did the exact right thing. They tabbed their two most overdue players and two most overdue guiding lights. They burnished the legend of 1986 perfectly.

The pitcher and the rightfielder who symbolized the journey from last place to first place. The manager who steered the ship in the right direction. The general manager who rebuilt the ship. Eight years since the Mets last paid proper attention to their past, they get back in the game with a bang.

There was no need to wait. I don’t mean they shouldn’t have put the Hall of Fame aside after 2002 (even though they shouldn’t have); I mean they shouldn’t have schlepped out induction for these four Mets one year longer. It’s a wonderfully crafted quartet, these men’s Mets accomplishments intertwined as they were. You can’t imagine the ’84, ’85 or ’86 Mets without Darryl and Doc. You can’t imagine them having come together without Davey or Cashen. Each of them is among the best the Mets have ever had at their particular jobs. Gooden was as great as any Met has ever been for a significant period of time. Strawberry was as spectacular as any Met has ever been for the length of a Met career. No conversation of Met managers can go more than two paragraphs before Johnson is mentioned. And go find me someone who put an organization together from ruins the way Cashen did.

This is exciting. This is genuinely exciting for a Mets fan who’s been waiting for the team to recognize itself. We recognize them far too often for the train wreck they’ve become in the moment. I love this chance to recognize them for the glory they achieved and the idea that they might achieve more of it.

Let’s Go Mets!

by Jason Fry on 18 January 2010 9:12 am Shortly before the Mets’ crack baseball folks heard about Carlos Beltran’s surgery and carefully aimed the rifle at the blasted remnants of their own feet, I spent a good chunk of time contemplating this post by Amazin’ Avenue’s Sam Page. Based on WAR, it showed the pre-Steadmanized Mets as an 83-win team. Page then offered some ways the Mets could add some more wins, through a combination of new moves and better luck in-house. A Joel Piniero signing would net 2 more. A trade of Luis Castillo/prospects for Brandon Phillips and Bronson Arroyo would be worth an eye-popping 5. The addition of any catcher (something even the Mets should be capable of) would be worth 1. In-house, better years from Wright, Reyes, Oliver, Pelfrey (far from impossible with a real infield), Maine and a breakout from Niese would add 7.

You can play with the possibilities yourself over at AA. Add them up, and the Mets are in the 90s, and quite possibly in the postseason. Yes, these same Mets who won 70 games last year and have since decayed in memory to Cleveland Spiders territory. None of the ways of ascending from 83 wins is from the WFAN crackpipe school (“Why doan we, uhhhh, trade Daniel Murphy and dat kid F-Mart to da Cardinals for Albert Pujols?”), as Piniero and the other pitchers discussed by Page are presumably within the Mets’ grasp, and the potential trade with the Reds is at least a possibility.

Maybe it was just the usual effect of changing the calendar and being able to think about spring training, but I was feeling surprisingly optimistic. And while the early-season loss of Beltran knocks a win off of that total, if the Mets make the right moves, they should still be better than OK.

Ah, but there’s that “if” — and that gets us back to Beltran.

The real problem with the Beltran news isn’t the loss of our center fielder until sometime around Memorial Day, though that’s obviously bad enough. It isn’t the risible he-said, he-said mess that’s been all over the papers of late, though that’s embarrassing. It’s that there’s no scenario you can reconstruct in which the Mets don’t look like bumbling fools. (For the record, I suspect Andee had it right the other day: The team doctors and Omar agreed with Steadman’s diagnosis and told him to proceed, only to have Jeff Wilpon freak out and order up a self-defeating media dumb show to assuage his anger.) Whatever the case, the Mets amply demonstrated their own mistrust in Omar, drove a wedge between themselves and one of their best players, and gave the universe of reporters, agents, baseball executives and fans still more evidence for suspecting they’d screw up a one-car funeral. Way to go, gang!

And that’s where all that WAR threatens to fall to pieces. If the Mets can’t manage an unfortunate but apparently straightforward situation in which Carlos Beltran needs knee surgery, can you trust them to swing a potential deal with the Reds that would greatly improve the club? Can you trust them to fill the rest of the off-season’s holes capably? (I was feeling better in this regard before. Now that’s gone.) Can you trust them to make the right moves come June? At the break? At the trading deadline?

For more and more of us, the answer is no. We don’t trust this team. We don’t trust that it’s being run effectively, and so we don’t expect it to win. And so, consciously or not, we harden our hearts and close our wallets.

Ultimately, that’s much more damaging — and harder to fix — than anything in Carlos Beltran’s knee.

by Greg Prince on 18 January 2010 12:46 am Who thought there could be three variations on essentially the same name and it would be the Jets who got the best of the lot? Since when do the Jets get the best of anything?

On the other hand, is it terribly surprising the Mets got the Shawn — not to mention the Sean — end of the stick?

We’re not here to bury Shawn Green, the diminished outfielder of 2006-07, nor Sean Green, the erratic relief pitcher of 2009. We’re here to praise the hell out of Shonn Greene, postseason running back extraordinaire.

I confess I’m just getting up to speed on the latest and greatest in Shonn Greene. Tuning out football until the wounds of baseball have healed (not that they ever really heal), I’m slow to know my local football squads beyond their marquee players. Shonn Greene? My research indicates he wasn’t truly top-of-the-bill material until the first Indianapolis game…as in there’s going to be a second real soon. I was watching the Jets in that must-win contest in December and heard something along the lines of “Shawn Green” and thought, “I must be mistaken. There couldn’t really be one on the Jets so soon after we’ve had two on the Mets.”

But there is. Thank goodness there is.

Shonn Greene is a damn sight faster than Shawn Green. He’s also probably a more reliable pitcher than Sean Green. Sean Green’s never thrown anything in the postseason. Shawn Green threw a bomb to Jose Valentin who matriculated the ball down the field to Paul Lo Duca who intercepted both Jeff Kent and J.D. Drew in the first game of the 2006 NLDS, but is otherwise October-remembered around here for falling down in the right field end zone against the Cardinals one round later.

The third member of our homophonous trio stays on his feet and scores. Shonn Greene rushed for 135 yards last week against the Bengals and 128 yards against the Chargers this week, with a touchdown in each affair. The Jets won and won again. He’s a rookie. Shawn Green was young once, too. He was quite good at the time (good enough to deserve an award that recently went to Kevin Youkilis). Then he got older and became a Met when he didn’t have a whole lot left. Pity. Sean Green has some years ahead of him. Maybe he won’t always hit batters with the bases loaded. Maybe.

Shawn, Sean and Shonn sound alike, but only one appears to be sixty minutes from a Super Bowl.

***

Kirk Gimenez, the SportsNite anchor on SNY, was hired, as best as I can tell, for his ability to make wacky sound effects, kind of like that guy in the Police Academy movies. He doesn’t, however, communicate sports news very well. Gimenez reported at the top of Sunday evening’s telecast that the Jets have now won two postseason games in the same year for the first time since 1982. How long ago was that? According to Kirk, it was so long ago that Mark Sanchez, now 23, was only four years old.

The Jets won those games in January 1983. Mark Sanchez was born in November 1986, making Sanchez approximately zero minus three years and ten months…and anybody watching this show wonder how stuff like that gets on the air. If Sanchez had been four when Richard Todd was leading the Jets to the AFC title game 27 years ago, then he’d be a 31-year-old rookie at this moment.

One glance at the script or a roster would have told somebody at SportsNite that this was quite wrong. One glance at Sanchez would indicate the quarterback grew a beard only so he’d look old enough to buy beer.

To be fair, Kirk was probably meant to say “that was four years before Sanchez was born,” but how could Gimenez be expected to get that straight? He was too busy concentrating on spitting out, in one of his funny voices a beat or two later, that Sanchez is now “all growsed up” after beating San Diego.

Show the highlights, show the press conferences and then show Mets Yearbook. SNY should otherwise do away with the SportsNite anchor concept. It is not serving them well.

UPDATE: On the 1:00 AM airing of the show, Gimenez slowed down his delivery long enough to say Sanchez was “not even born yet” when the Jets last won two postseason games in the same year. And he didn’t do the “all growsed up” shtick either. Wow, somebody somewhere really does pay attention.

by Greg Prince on 17 January 2010 11:38 am While sitting here hopng the J-E-T-S will B-E-A-T the Chargers (and coming up with reasons to dislike the City of San Diego…stupid zoo), I’ve been kindly sent a link to a segment of vintage Art Rust, Jr. from 1981, at the beginning of his tenure on WABC. It’s a Spring Training show during which Art — whom we lost this week — forecasts unseasonably blue skies for the rapidly improving the Mets. Lots of guys who can “hit the rock,” a big comeback by “Swannie” and so much more.

Listen to this if you were a fan of New York’s only nightly sports talk fix from that era. Listen to this, too, if you missed him entirely. We were six years from WFAN, and he sounds nothing like WFAN. It doesn’t even sound that much like 1981 (which sources inform me was almost thirty years ago), but that was part of Art’s charm.

And look out for Joel Youngblood at the hot corner this year.

AUDIO HERE: Art Rust, Jr. on WABC

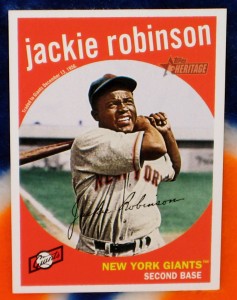

by Greg Prince on 16 January 2010 6:26 pm  Perhaps you’re familiar with the story of Jackie Robinson retiring rather than accepting the last transaction Walter O’Malley arranged for him, a trade to the Giants for Dick Littlefield. Perhaps you’re familiar with the story of Jackie Robinson retiring rather than accepting the last transaction Walter O’Malley arranged for him, a trade to the Giants for Dick Littlefield.

The very thought! Jackie the ultimate Dodger going to the hated rivals! GASP! No wonder he quit!

Actually, Robinson had already decided to retire from baseball after the 1956 season to go to work full time as Chock full o’ Nuts’ director of personnel when the trade was made: Robinson to New York; pitcher Dick Littlefield and $35,000 to Brooklyn. The move was seen as a parting shot from O’Malley, who never liked Robinson.

Contrary to the myth that Robinson would have rather died than call the Polo Grounds home, Jackie — according to biographer Arnold Rampersad — maintained cordial contact with Giants owner Horace Stoneham after the announcement and even told one reporter, “I’ve got no hard feelings against the Dodgers but I’m going to do everything I can to beat them next year.” Perhaps it was a charade (Jackie had sold his “I’m retiring” exclusive to Look magazine and it hadn’t yet been published), but he didn’t immediately or publicly reject the trade out of hand. By this point in his career, however, Robinson was almost 38 and knew the end of the line had been reached. Still, it took more than a month after the trade was made for baseball’s trailblazer to tell his prospective new employer thanks, but no thanks.

“I assure you that my retirement has nothing to do with my trade to your organization,” Robinson wrote Stoneham in a letter making it clear he wouldn’t be reporting to Spring Training in 1957. “From all I have heard from people who have worked with you it would have been a pleasure to have been in your organization. Again my thanks and continued success for you and the New York Giants.”

Doesn’t sound all that vitriolic, does it?

It was a little late for Jackie Robinson to start switching teams, but that doesn’t mean somebody didn’t imagine he might have followed through. Last year, Topps created a special set of “Cards That Never Were” in the style of their 1959 releases for a sports collector’s show. Jackie as a New York Giant, swinging in black and orange as if he hadn’t retired, was in the set. This caught the eagle eye of my baseball card maven friend, Joe, who tracked it down for me for my birthday…which was awfully nice of him. (And yes, I do know my share of baseball card mavens.)

Jackie Robinson, pictured as a New York Giant: I’ll be looking for a reproduction in a Rotunda near me.

by Greg Prince on 15 January 2010 8:37 pm Omar Minaya has told Newsday…ah, y’know what? I was going to update the saga of the ‘scope, but honestly, what’s the point? Without getting into Minaya’s crystal-clear explanation that he did talk to Beltran but he didn’t tell Beltran to have the surgery but there’s no problem between the organization and Beltran even though the organization — which may be a misnomer since nobody running the Mets seems particularly organized — has gone to great lengths to express it does have a problem with Beltran, suffice it to say Omarspeak is having its way with clarity once again.

To sum up:

• The Mets are still without one of their most important players.

• It’s a wonder the people running the club don’t lock themselves out of their offices every night.

by Greg Prince on 14 January 2010 10:49 pm “I am totally surprised by the reaction to my recent knee surgery.”

Honestly, this is better than the Jay-Conan thing. I mean, yeah, I know, we don’t want to be without Carlos Beltran, and it won’t be the least bit funny come April 5 when Angel Pagan is waiting for a fly ball in left only to realize he’s supposed to be in center, but still…

“Any accusations that I ignored or defied the team’s wishes are simply false.”

First the Mets don’t know about the surgery. Then the Mets kind of know about it, but wanted to mull it over. And they need to talk to a lawyer.

“I also spoke to Omar Minaya about the surgery on Tuesday. He did not ask me to wait, or to get another doctor’s opinion. He just wished me well.”

Now the party of the knee part, Beltran, issues a statement saying, no, the Mets are a bunch of liars…either that or Omar Minaya should check with Drs. Steadman and Altchek regarding treatment for short-term memory loss.

“No one from the team raised any issue until Wednesday, after I was already in surgery. I do not know what else I could have done.”

Maybe Minaya didn’t realize it was Carlos Beltran on the phone. Maybe he thought it was Rigo Beltran (I heard those two were tight). Maybe calling the GM doesn’t count as notification. Or maybe Carlos is just in this to cause trouble. Incidentally, I hope Carlos is feeling up to attending the Baseball Writers’ dinner next week to pick up his Joan Payson Award for community service.

“The most important thing here is that the surgery was a total success and I expect to be back on the field playing the game I love sooner rather than later.”

Let’s be clear on something: As much as we love the Mets, this is not, as I heard it referred to Wednesday night, a disaster. Haiti’s a disaster. This is just embarrassing and semi-professional. And if the fallout isn’t all that amusing from the standpoint of rooting for the Mets to win ballgames, well, it is pretty much par for what has become the course with this organization, and if you don’t laugh at it (in January, anyway), you might cry from it. John Ricco, whom I guess Carlos Beltran didn’t call before surgery, said the Mets were “disappointed” by the process and/or the player.

Disappointed? Gads, that’s so last decade. Or did the last one never end? In any event, as the man said, the most important thing here is that the surgery was a total success and he expects to be back on the field playing the game he loves sooner rather than later.

From Carlos Beltran’s mouth to Omar Minaya’s ear.

by Greg Prince on 14 January 2010 4:29 pm The Mets wanted Carlos Beltran to get a third opinion? OK, here goes:

“Hey Carlos, your team needs starting pitching.”

Opinions are like Met injuries: There are plenty to go around. Today the Mets expressed, as blandly and nonlitigiously as possible (other than by just shutting up), the opinion that Carlos Beltran went behind their backs to fix his knee. That’s their opinion and they’re entitled to it. That knee is a big investment for them.

I don’t really know what the Mets were supposed to do once they couldn’t be ahead of the story from the start. Had they taken, as Mike Francesa lucidly suggested, the tack of “we don’t discuss our players’ injuries,” it would have fired up a PR storm that was already brewing. A PR storm is almost always brewing around the Mets. Twenty-four hours ago, the Mets’ PR waters seemed unusually calm. David Wright was sharing football insights with Francesa, and pitchers and catchers were creeping ever closer.

Now hobbled centerfielders and secret surgeons are reporting instead.

I also don’t know what reporters who cover the Mets are supposed to ask, but none of their questions elicited much in the way of revelations — bad for information junkies, good for the Mets not looking terrible, I suppose. I listened to the conference call with John Ricco, which boiled down to two essential exchanges:

“Can you tell us everything we want to know about your internal machinations?”

“No.”

And:

“Can you accurately forecast when an injured player will be fully recovered and playing baseball despite the horrendous track record attached to your usually wild and inaccurate guesses.”

“Twelve weeks.”

Other than that, the whole process has been characteristically enlightening.

The upshot I gather is Carlos Beltran has two knees and would like them both to function so he can perform at his job. He went to a really well-regarded doctor for an operation that apparently didn’t do him undue harm. He and his agent ignored his employer since the Mets’ default prescription for regular leechings and bleedings wasn’t making him feel any less pain. And now Angel Pagan will have to be directed to center field, which I’m guessing he’ll find nine of every ten times he lights out for it.

So…do the Mets still Believe in Comebacks?

|

|