The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 14 January 2010 4:29 pm The Mets wanted Carlos Beltran to get a third opinion? OK, here goes:

“Hey Carlos, your team needs starting pitching.”

Opinions are like Met injuries: There are plenty to go around. Today the Mets expressed, as blandly and nonlitigiously as possible (other than by just shutting up), the opinion that Carlos Beltran went behind their backs to fix his knee. That’s their opinion and they’re entitled to it. That knee is a big investment for them.

I don’t really know what the Mets were supposed to do once they couldn’t be ahead of the story from the start. Had they taken, as Mike Francesa lucidly suggested, the tack of “we don’t discuss our players’ injuries,” it would have fired up a PR storm that was already brewing. A PR storm is almost always brewing around the Mets. Twenty-four hours ago, the Mets’ PR waters seemed unusually calm. David Wright was sharing football insights with Francesa, and pitchers and catchers were creeping ever closer.

Now hobbled centerfielders and secret surgeons are reporting instead.

I also don’t know what reporters who cover the Mets are supposed to ask, but none of their questions elicited much in the way of revelations — bad for information junkies, good for the Mets not looking terrible, I suppose. I listened to the conference call with John Ricco, which boiled down to two essential exchanges:

“Can you tell us everything we want to know about your internal machinations?”

“No.”

And:

“Can you accurately forecast when an injured player will be fully recovered and playing baseball despite the horrendous track record attached to your usually wild and inaccurate guesses.”

“Twelve weeks.”

Other than that, the whole process has been characteristically enlightening.

The upshot I gather is Carlos Beltran has two knees and would like them both to function so he can perform at his job. He went to a really well-regarded doctor for an operation that apparently didn’t do him undue harm. He and his agent ignored his employer since the Mets’ default prescription for regular leechings and bleedings wasn’t making him feel any less pain. And now Angel Pagan will have to be directed to center field, which I’m guessing he’ll find nine of every ten times he lights out for it.

So…do the Mets still Believe in Comebacks?

by Greg Prince on 13 January 2010 11:04 pm Carlos Beltran is out for a projected twelve weeks — three or so months of not just not playing, but also not practicing — after surprise arthoscopic surgey on his right knee to address osteoarthritis that was causing him too much pain to continue offseason training. I say “surprise,” because it reportedly wasn’t on the Mets’ radar or at least wasn’t done with the Mets’ blessing.

Part of me doesn’t blame Beltran for avoiding the Mets’ hierarchy, given their uninspiring track record handling injuries. Still, you probably have to tell them.

Let’s hope Carlos is feeling spry soon. Let’s hope we’re looking all right with Angel Pagan or some other stopgap in center before Beltran is back. Let’s hope our walking 2009 wounded are actually on the way back in 2010 before we pencil them in as healthy. When it comes to figuring out what might happen with the Mets, it may be best to use disappearing ink.

by Greg Prince on 13 January 2010 8:26 pm A winter’s night like this one? Twenty-five or so years ago? I would be dying for Mets news. I’d surely have checked my favorite blogs, except there were no blogs. I’d have watched MLB Network or SNY in hopes they had some information on their crawls, but there was neither an MLB nor an SNY. Naturally, the inclination would have been to tune in WFAN, but y’know what? There wasn’t even a WFAN before 1987.

Not an outlet was stirring, not even a Tweet.

You wanted live streaming hot stove baseball talk around here, you had one option if you were lucky: Art Rust, Jr. There was no guarantee that Art would be talking baseball. But if he was…oh boy! Maybe he’d have a Met or a Met announcer or a Met beat writer on the phone. Maybe he’d just be taking a call from a Mets fan. You leaned forward, even though you suspected you weren’t going to learn anything.

“Art, do you see the Mets improving their roster by maybe getting some new players?”

“Mark my words, my friend, when Opening Day rolls around, the New York Mets will be ready to go in the National League.”

It wasn’t much, but I can’t tell you how much better it was than nothing.

Art Rust, Jr., who died Tuesday at 82, was the sports talk voice of New York for quite a while. I don’t mean he dominated the field. He was the field. He was it on commercial radio. Generally speaking — which was something Art did with élan — if you wanted a sports fix before July 1, 1987, the date the FAN took flight and forever changed our expectations, you had Art, or you had radio silence. WFUV aired a late-night weekend program, and WINS and WCBS each gave you scores at :15 and :45 each hour, but for most of the 1980s, the only way to surround yourself with sports talk was to keep company with Art Rust, Jr.

We’re spoiled now. We have each other and so many other vehicles to feed our obsession. But when it was just you and Art, you valued Art. I know I did, particularly when I first encountered him one night in the summer of 1980. The Mets game had ended on WMCA (570 AM), and on came a smooth, sharp, unironic voice — apparently airlifted in from one of those radios Bugs Bunny might have been listening to in the ’40s — telling me there was no doubt about it, my friend, the New York Mets are playing great baseball and there’s going to be playoff baseball out at Flushing By The Bay this October, you can count on it.

You could always count on what Art told you. Art dealt in definites. Mark his words, he insisted to almost every caller after those Mets games on ‘MCA in 1980, you’re going to have interleague baseball by the end of this decade…and every team is going to be playing under a dome by then. So he was off by a few years on one prediction and ridiculously wrong on the other one. Art was certain, and that was somehow assuring. In that Magic Is Back summer, when I dared to dream the Mets would catch and pass the Phillies, him telling me the Mets were going to the playoffs was good enough for me.

Other talk radio hosts tell you the way it is and brook no dissent. Art wasn’t that way. He’d let you have your say, no matter how wrong it was. His big sport was boxing, which even in the early ’80s seemed rather old-timey. There was a huge bout coming up. I want to say it was Thomas Hearns vs. Sugar Ray Leonard; might have been Larry Holmes vs. Gerry Cooney. Whichever one it was, Art declared it over in advance. Hearns would beat Leonard…or Cooney would beat Holmes.

Next caller.

Except the guy Rust picked lost. Did it make Art look bad? Not really, because when a tol’-ya-so caller called in to remind Art of his incorrect prediction, Art shrugged, “I got it wrong, sir” and moved on to the next subject. A simple admission, but difficult for so many who talk into a microphone to make.

I remember that. I also remember that Terry Moore was Art’s favorite ballplayer. “My guy — Terry Moore of the St. Louis Cardinals.” Art would talk about Moore, a centerfielder from the ’30s, in the same vein defensively as DiMaggio and Mantle and Mays. He was that good. Was he? I’ve since read that he was, which is neither here nor there. Art said so, which was all I had to know.

Art really was old school. He was just a shade older than my father but his lingo arrived bubble-wrapped from another era. Shea was always Flushing By The Bay. Yankee Stadium was The Big Ball Orchard In The South Bronx. A good defensive catcher could Swish That Leather Behind The Dish, my friend. Circa 1980, that sounded like an impolitic assessment of the nightlife in certain precincts of Greenwich Village, but whatever. Art expanded my vocabulary as he did my horizons. Without him, I wouldn’t have known who the hell Terry Moore was.

The 1980 season ended with the Mets missing the playoffs by a mere 24 games. Art continued to do sports talk on WMCA that winter and then made a well-publicized move to WABC. I listened as much as I could stand to, considering WABC had just become the Yankees’ station. He had plenty of Mets guests nonetheless. One night he reunited, via phone, Cleon Jones and Davey Johnson, parties to the final out of the ’69 World Series. Cleon and Davey were each now working for the Mets in the minor leagues, Art said. (Who knew?) Another night he had on Steve Albert, then partner of Ralph Kiner and Bob Murphy. The Mets had been playing surprisingly competently, motivating me, for the only time, to call the Art Rust, Jr. Show.

I asked Steve what that big black thing beyond centerfield at Shea was.

“You mean the scoreboard?” Art and Steve asked in unison.

No, that other thing.

“You mean the batter’s eye?” Steve asked.

Uh, yeah, I said.

God, I felt stupid. I’d heard that phrase all my life and I’d seen that thing all my life, yet I never knew what either of them was. Nobody told me I was an idiot, however. Instead, Art asked me if there was anything else.

“I just want to say the Mets have the best fireman, the best second baseman and the best broadcasters in the National League.”

They chuckled and thanked me for calling. And I stand by those appraisals of Neil Allen and Doug Flynn.

by Greg Prince on 12 January 2010 6:21 pm My 2010 plans weren’t inexorably altered when I learned the Dodgers signed Argenis Reyes to a minor league contract, but upon doing a bit of checking, I now realize we’ve lost someone whose penchant for instant winning was unprecedented. We’ve lost a Met who was able to say, longer than any other Met, that he had been — as Willie Randolph might have put it — a winner his whole life…or at least the portion of his life that we cared about.

In short, Argenis Reyes was the best scratch-off lottery ticket we ever bought. We kept scratching and we kept winning.

I didn’t think my 2008 plans were inexorably altered either when the Mets called up the other Reyes two summers ago, but John Lennon advised us life is what happens when you’re busy making other plans. Argenis is what indeed happened to us in the middle of ’08 in a very fundamentally pleasing way.

Consider the indisputable evidence.

On July 3, 2008, the Mets placed shining light Luis Castillo on the 15-day Disabled List with a strained left hip flexor, though “chronic futility” might have been enough. To replace him, the Mets sent down to New Orleans (remember the Zephyrs?) and asked for a side of Argenis Reyes to go.

And go he did. On his first night as a Met, with his new team leading 11-1 in the seventh inning at St. Louis, Jerry Manuel inserted Reyes at second, replacing Damion Easley for the rest of the blowout. The Mets continued to lead 11-1 and put the game away. Argenis Reyes was 1-0.

The next night, in Philadelphia, Argenis Reyes sat and the Mets lost. Tsk.

The night after that, July 5, Argenis Reyes pinch-hit and the Mets won. Never mind that Argenis flied out. It’s a team game, and Argenis’s team was now 2-0.

Extra innings were required on July 6. In the tenth inning, Argenis pinch-hit again. He struck out. The Mets, though, would eventually come through. ‘Genny and the Mets were now 3-0.

A pattern was developing. Argenis Reyes pinch-hit again, on July 7. The Mets were up 10-7 in the ninth. Argenis grounded out to end the top of the inning. Then he left. Billy Wagner came in and gave up two runs, but the Mets hung on to win the damn thing, 10-9. They were now 4-0 in games in which Argenis Reyes participated.

There was no stopping these Mets…these Argenis Reyes Mets. He entered the next two games, against the Giant at Shea, as a pinch-hitter and stayed in for defense both times. He collected his first three hits in this pair of contests and the Mets shut out San Francisco twice. The Mets were 6-0 while under the influence of Argenis.

Manuel, giddy from himself replacing Randolph, was determined to go with the hottest of hands, the winningest winner who had been a winner his whole Met life. He started Argenis Reyes at second base on July 10. Guess what — the Mets won again. These were the 7-0 Mets and their newest sensation was the 7-0 Argenis Reyes. Granted, his height was listed at 5′ 11″, and that seemed generous, but did anybody ever stand taller sooner?

No time to ask. The Rockies rolled into town and found themselves the victim of a boulder dropping their head. Its name? Argenis Reyes, an 0-for-1 pinch-hitter on July 11, but an 8-for-8 Met as his boys won again, 2-1. The next day, a brilliant Saturday, was a spectacular kind of Argenis Reyes day. He started and recorded a base hit…exactly as many as the Rockies cobbled together off Pedro Martinez and the four Met relievers who followed him after Pedro had to leave with an injury. Argenis Reyes, however, wasn’t going anywhere. The Mets won 3-0 and Reyes had now played nine games in the majors without ever experiencing a loss.

Jerry, in his cocky gangsta mode, rested A. Reyes the next night and managed a win anyway. Then came the All-Star Break. Then came the game after, which the Mets won in the ninth inning at Cincinnati. It required a come-from-behind rally, generated when A. Reyes singled with one out, thereby lifting his batting average, slugging percentage and on-base percentage to .316 apiece. D. Wright then homered to tie the Reds 8-8. The Mets, with Reyes remaining in the game at second, came away victorious that July 17 evening, 10-8.

Did all good things have to end? Alas, yes. The Mets’ ten-game winning streak was snapped on July 18 despite Argenis Reyes’s deployment as a pinch-hitter. That was the first game in which Reyes played that his team lost. No word on whether he pricked a finger to see if he also now bled like any normal human.

From there, the Argenis Reyes story unravels. Short version for the likable little guy: He didn’t hit; he wasn’t that fantastic a second baseman; and the Mets stopped enjoying good fortune. The 2008 Mets came up painfully shy of a playoff spot. The 2009 Mets came to Citi Field unnoticeably shy of Argenis Reyes. Injuries to almost everybody, however, washed him ashore Flushing Bay in late June. He made it into nine games for the ’09 Mets. They lost seven of them. Then he was gone. Now he’s a Dodger.

But here’s the thing you’ve got to know: Argenis Reyes’s team won the first ten games in which he played. I can find no evidence of any other Met in 48 seasons being able to say the same thing. I looked. I checked long pre-2008 Met winning streaks and the Met debuts that coincided with the blossoming of those long Met winning streaks and came up Argenisless. Tom Paciorek had immediate impact almost as resounding as Reyes, but just missed the mark; his Mets lost their first game in July 1985, 1-0. Then they reeled off ten straight wins with a dash of Paciorek in the boxscore. But as Billy Joel put it, get it right the first time, that’s the main thing. Get it right the next time? That’s not the same thing.

Besides Paciorek, nobody comes incredibly close to the standard set by Argenis Reyes. The Mets were red hot when Willie Mays came over in 1972, but Willie played in only four consecutive victories to start his Met career. The Mets were white hot when Mike Piazza came over in 1998, but Mike played in only seven consecutive victories to start his Met career.

In this narrow but actual context, we can honestly say Willie Mays and Mike Piazza were no Argenis Reyeses and mean it completely as a compliment to Argenis.

by Greg Prince on 12 January 2010 1:29 am  Mark McGwire says he wishes he didn’t play in the Steroid Era. I have the same wish to a certain degree. From 1997 to 2001, McGwire hit 13 home runs against the Mets, batting .280 and getting on base in almost 39% of his plate appearances. Beating the Cardinals on any given day or night then would have been easier had he not produced those numbers. Hence, I wish Mark McGwire hadn’t played against the Mets in the Steroid Era. Conversely, I’m glad he played against the Braves, the Cubs, the Marlins and whoever else was keeping us out of the playoffs back then. Mark McGwire says he wishes he didn’t play in the Steroid Era. I have the same wish to a certain degree. From 1997 to 2001, McGwire hit 13 home runs against the Mets, batting .280 and getting on base in almost 39% of his plate appearances. Beating the Cardinals on any given day or night then would have been easier had he not produced those numbers. Hence, I wish Mark McGwire hadn’t played against the Mets in the Steroid Era. Conversely, I’m glad he played against the Braves, the Cubs, the Marlins and whoever else was keeping us out of the playoffs back then.

I could also have done without Sammy Sosa, Barry Bonds, Ken Caminiti…you name ’em facing the Mets. I wish the Mets had faced 9 Freddie Pateks (5′ 5″; 41 homers in 14 seasons) per lineup or 25 Harry Chappases (5′ 3″; 1 homer in 3 seasons) per roster. The Mets could have found a way to lose to Lilliputians, too, particularly at the end of 1998 when the snatching of defeat from the jaws of victory was a Metropolitan art, but I would have taken our chances with a less uniformly enhanced opposition.

Thing is, the new hitting coach of the St. Louis Cardinals did play when he played, as did the others who excelled as supernatural sluggers. Those seasons happened. The homers were hit, the numbers were posted. Mark McGwire really did hit 70 homers one year, 66 in another. He did whatever he did to the Mets, just as the Mets did whatever they did to the Cardinals when they showed down. Mets-Cubs games happened, with McGwire’s record-chasing shadow, Sammy Sosa, a major gate attraction at Shea — no matter how much less genuine Sosa’s statistics, like McGwire’s, appear in hindsight. Mets-Giants games featuring Barry Bonds happened, even if no one’s exactly waiting on a Barry Bonds outburst of qualified contrition to match McGwire’s.

Ken Caminiti, who died of a heart attack in 2004, gathered momentum toward a unanimous MVP award in 1996 after a particularly dramatic weekend against the Mets, recounted here by Baseball Library:

Caminiti’s toughness reached legendary proportions in August of 1996, when two liters of an IV solution and a Snickers bar helped him overcome dehydration, diarrhea, and nausea and hit two home runs […] against the New York Mets in Monterrey, Mexico. The 8-0 win tied San Diego with Los Angeles for first place in the NL West; Caminiti’s inspiring play eventually led the Padres to their first division title since 1984.

Caminiti admitted in 2002, after he retired, that he used steroids in his MVP year and in the years that followed. It doesn’t mean he didn’t find sustenance in a Snickers while in Mexico. It also doesn’t mean he didn’t help the Padres win a game and a division title. He, like many, played and succeeded in the Steroid Era.

More accurately, perhaps, where these players are concerned, they didn’t play in the Steroid Era — they composed the Steroid Era. That was the most darkly amusing component of McGwire’s confession Monday. He wishes he didn’t play in the Steroid Era? How does he suppose the period in question, the mid-’90s through the early ’00s, became the Steroid Era? Was it listed on a calendar in advance? Or was it because so many baseball players decided, for whatever reasons (McGwire says he was compelled by injury), to inject or ingest substances that weren’t altogether on the up and up where the old ballgame was concerned?

Mark McGwire was in full apology mode Monday, but he didn’t have to apologize to me as a baseball fan in 2010 for what he did in 1998. I saw him play at the height of the Steroid Era and it was quite entertaining. I watched him hit home runs on TV and I applauded from my couch when it didn’t harm the Mets’ Wild Card chances. When he hit what turned out to be his final Shea Stadium home run in 2001, I gave him a standing ovation because he was Mark McGwire, holder of the single-season home run record to that point, and to watch Mark McGwire hit a home run was to feel as if you were in on grandeur. Nobody really talked much about steroids then. Even if they had, they couldn’t erase what McGwire had achieved or accomplished — or just “did,” if his powerful feats no longer seem like achievements or accomplishments. As a partisan of the Mets, I didn’t want McGwire or Sosa or Bonds or Caminiti or their pumped-up brethren to do their damage against my team, but from the perspective of someone who loved baseball, I appreciated their ability to swing, connect and launch in ways that I had never seen consistently since I began watching the game.

I still sort of do, no matter how many asterisks public perception reasonably attaches to the bombs those sluggers detonated so explosively over so many National League fences. But they did what they did at the plate, however they went about doing it. That will not be erased. Those games in which they went incredibly deep took place. Boxscores are on file for all of them; I can probably dig up ticket stubs for a couple of them. The Mets lost to the Cardinals on August 12, 2001, when Big Mac hit his last Shea homer. The Mets’ record for 2001 is still 82-80. It won’t suddenly be 83-79 now. It won’t be 82-79-1. Nor should it be. I don’t know who else was juicing that day; I don’t know if McGwire was juicing that day, come to think of it. Mark McGwire may have been onto something in 2005 with his infamous “I’m not here to talk about the past” remark to Congress. You can talk about it all you want, but you can’t undo it.

Yet you can acknowledge that the past wasn’t passive, that eras didn’t innocently arise from the mists of unquantifiable intersections of time and space. The Steroid Era was the Steroid Era because Mark McGwire and an army of ballplayers who wished to Be Like Mark sought out steroids. These things don’t happen by accident.

He wishes he didn’t play then? Too late, pal.

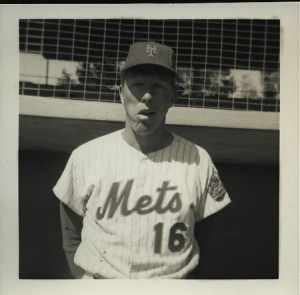

by Jason Fry on 10 January 2010 1:51 pm Longtime readers of this blog know of my quixotic pursuit of a decent picture of Al Schmelz, former Alaska Goldpanner and briefly a New York Met, along with many other momentary ballplayers in the bizarre 1967 campaign.

There were 54 1967 Mets — 35 making their team debuts — and those 54 players managed 61 wins, or 1.13 per Met. Those making their blue-and-orange debuts included a future Hall of Famer (Tom Seaver, of course), a player who’d become a star in New York (Jerry Koosman), one who did so elsewhere (Amos Otis), future workers of Miracles (Ken Boswell, Don Cardwell, Ed Charles, Cal Koonce and Ron Taylor), a guy who’d be better known in Met circles as a coach and a father (Sandy Alomar), a guy whose name would live in mild infamy (cruelly overhyped center fielder Don Bosch), another who’d be better known for his watering hole than his on-field pursuits (Phil Linz, impresario of the once-upon-a-time famous tavern Mister Laffs), and a lot of guys of interest only as answers to trivia questions posed on blogs such as this one (Dennis Bennett, Bill Graham, Joe Grzenda, Joe Moock, Les Rohr, Bart Shirley, Billy Wynne). There were 54 1967 Mets — 35 making their team debuts — and those 54 players managed 61 wins, or 1.13 per Met. Those making their blue-and-orange debuts included a future Hall of Famer (Tom Seaver, of course), a player who’d become a star in New York (Jerry Koosman), one who did so elsewhere (Amos Otis), future workers of Miracles (Ken Boswell, Don Cardwell, Ed Charles, Cal Koonce and Ron Taylor), a guy who’d be better known in Met circles as a coach and a father (Sandy Alomar), a guy whose name would live in mild infamy (cruelly overhyped center fielder Don Bosch), another who’d be better known for his watering hole than his on-field pursuits (Phil Linz, impresario of the once-upon-a-time famous tavern Mister Laffs), and a lot of guys of interest only as answers to trivia questions posed on blogs such as this one (Dennis Bennett, Bill Graham, Joe Grzenda, Joe Moock, Les Rohr, Bart Shirley, Billy Wynne).

But all those guys, from Bennett to Billy, got a decent baseball card one way or another, and are now enshrined in The Holy Books — my pair of binders collecting baseball cards for all the Mets since 1962: one card for each new Met, ordered by year. Including the Class of ’67.

Some of the ’67 Mets are fortunate enough to actually appear on Topps cards as Mets. Others demand creativity. Momentary Met Les Rohr has to share a 1968 rookie card with Ivan Murrell, a Houston outfielder wearing one of Topps’ blank black hats, but hey, it’s a card. Billy Connors shares a ’67 rookie card with fellow Cub Dave Dowling. Bill Denehy, Bob Heise, Bob Johnson, Jack Lamabe and Larry Stahl and Amos Otis appear hatless in their Met uniforms, or with their caps rendered generic, and are identified as members of other teams on their Topps cards. Properly attired as members of other teams are Bennett (Red Sox), Shirley (Dodgers), Nick Willhite and Wynne (Angels). Hal Reniff, sad to say, is a Yankee.

Graham and Moock never got Topps cards, and their careers were over before minor-league teams started issuing card sets in the mid-1970s. (A number of Mets in The Holy Books have cards from their tenure as Tides, Zephyrs, Bisons or members of other organizations’ farm clubs.) But Graham and Moock do have baseball cards, thanks to the efforts of a veteran card dealer named Larry Fritsch. Beginning in the late 1970s, Fritsch made several series of cards called One Year Winners, giving cardboard immortality to players who’d never had a card before. His efforts saved 10 thimbleful-of-coffee Mets — Graham and Moock, as well as Ray Daviault, Larry Foss, Rick Herrscher, Ted Schreiber, Wayne Graham, Dennis Musgraves, Shaun Fitzmaurice, Dick Rusteck — from anonymity.

But despite such efforts, a few Mets slipped through the cracks. Two — Brian Ostrosser and Leon Brown — got minor-league cards that are so dismal they’d be better off with nothing. (In Brown’s case this happened twice.) Tommy Moore got a Senior League card long after his big-league tenure. On it, he looks … well, senior. Then there are the guys who got nothing: Francisco Estrada, Lute Barnes, Bob Rauch, Greg Harts, Brian Ostrosser and Rich Puig. And, of course, Al Schmelz. Together, these nine make up the lonely roster of the Lost Mets.

In a fit of spectacular OCDism, I decided a few years ago that if the Lost Mets didn’t have cards, I would make cards for them — and so I did, using Photoshop to cobble together cards from old yearbook photos and scans of Topps cards. Which worked out fine for everybody — except Schmelz.

No moment of Schmelz’s baseball career seems to have been captured in a decent color photo. There are shots of him as an Alaska Goldpanner, but they’re in black and white. A couple of Mets yearbooks have pictures of him grouped with other guys invited to camp — always group shots, always black and white. He’s in the team photos — in glorious color, no less — in the ’67 and ’68 yearbooks, but of course he’s in the back, almost completely blocked by his teammates. His Holy Books card is a Frankenstein assemblage, with his body assembled from bits of pieces of different Mets from that ’67 team photo. It was the best I could do.

The Mets don’t have a better picture. As far as I can tell, no one else does either. I’ve even written to Schmelz himself a couple of times, with no answer. (I no longer do that — it seems like a ridiculous reason to wind up the subject of a restraining order.) Though Schmelz was photographed a few years ago at a fantasy camp in Arizona: He was wearing 1990s-looking Mets garb, sunglasses and what I had to interpret as a slightly mocking smile.

Every couple of months, out of habit, I Google Schmelz’s name. The results are not as straightforward as you might think: “Al Schmelz” appears to mean “aluminum smelter” in German. I also look for him on eBay. Sometimes this turns up a copy of an undersized, black-and-white semi-card he got as part of a 1990 Shea giveaway. (Cool, but no good for THB purposes.) Mostly it turns up nothing.

Until this morning. There it was, a snapshot of Al Schmelz, wearing the number that would one day belong to Dwight Gooden. As you can see, naturally it’s in black and white. Inevitably, Schmelz’s face is mottled by shadows. Of course his expression suggests that he just had a gulp of milk past its expiration date. No matter. It’s a picture of Al Schmelz, and though it’s faint praise to say it’s the best picture of him I’ve ever seen, it’s the best picture of him I’ve ever seen.

Of course I bought it. By now, it’s pretty much my job. Besides, who else would?

by Jason Fry on 9 January 2010 9:00 am Yesterday Greg and I exchanged a brief flurry of emails. I found myself wanting to write something about the Montreal Expos. He had been gripped by the same need, and was already working on this.

Not a surprise; stuff like that happens when you’re both baseball fanatics like-minded enough to share a blog, even when there’s no Met in the picture. What the heck, we decided. It’s Expos Weekend.

The funny thing is, I never particularly cared about the Expos while they were around. If anything, I found them vaguely ridiculous. First of all, there was the name. I’ll grant you that it’s not immediately obvious what a Met is. If I may risk disloyalty, it’s kind of a stupid name. But compared to “Expos” it’s genius. As a child I figured “Expo” must be French until the children’s grapevine opined that that wasn’t true (though actually it kind of is), leading me to finally ask some adult or other. When I got an explanation, I assumed I was being made fun of. Why would anyone name a baseball team after that?

Then there was the hat. I never saw the “Newhart” episode mentioned by Tyler Kepner here — in fact, while I’ve always been aware of “Newhart” and trust that it’s worthy of respect, I don’t think I’ve ever seen any episode of it — but hearing that George couldn’t figure out what was on their hat made me clap my hands. I know how he felt — I puzzled over the Expos cap for years as a kid and was well past puberty when I looked at it one day and suddenly yelped “It’s an M!” as if I’d spent a lifetime staring at a baseball “Magic Eye” book and finally got it. (Well yeah, except it also included an e and a b, for “Expos” and “baseball.” Which was really stupid.)

Then there was Olympic Stadium. There was the way you could see the backs of the umpire and the catcher and the batter and the front of the pitcher in the camera shot from center field, which was maddening once you noticed it and threatened to give you vertigo as you proved unable to take your eyes off of it. There was Youppi, whom I could never stand, not so much because he was a mascot but because he was so thoroughly generic, like the product of a committee that had actually wanted to make the kind of lackluster thing that gets blamed on committees. And there was the way the light always seemed off. At least on TV, games there looked faintly yellowed somehow, and I always got the feeling there wasn’t enough air, like the players were going about their business in some giant Canadian terrarium, except instead of having sadistic children rap on the glass you got morons blowing air horns throughout the middle innings of interminable games. Braaaaaaaap braaaaaaaap braaaaaaaap. Remember that? I think if I heard that sound on my deathbed I’d sit bolt upright and gasp, “Jesus, it’s Olympic Stadium!”

This is not to scorn the Expos, mind you. I respected them as a collection of players. Heck, I feared them — they had a habit of ending our dreams, either by exposing scrappy Met teams as noncontenders relatively early or tearing the underbelly out of good Met teams heartbreakingly late. (Somewhere, Chris Nabholz is still laughing at us.) And I felt for their fans. They were unstoppable in 1994, only to have that season turned into less than an asterisk by a labor war, and then they were consistently treated in the most cruel and dirty way by Major League Baseball, whether it was denying them callups in a pennant race, reducing the payroll to penury, frog-marching them to Puerto Rico for a farcical semi-relocation or then finally gift-wrapping them for a city that had already lost two franchises. (And then that city unretired the Expos’ modest collection of retired numbers.) Expos fans couldn’t be blamed for not showing up for the team’s final years — why on earth would they? They were a city of Charlie Browns who’d finally decided Lucy could take her football and stick it.

But as the Expos began their death spiral, they became something else to me. They became the baseball expression of my own paranoia.

Greg will recall that while baseball’s poohbahs were studying contraction with unseemly eagerness (and let me pause here to hope that Satan just gave Carl Pohlad another quarter-turn on the spit), I was grimly certain that somehow these wheels would grind until one of the teams contracted was the Mets. Obviously this was insane, and on some level I was aware of that, but I’d babble incessantly about it anyway, and my only hope is that I was never dumb enough to do that in front of an Expos fan. I knew of the weird links between them and us, of course. How the Expos began their existence by beating the Mets (by a single run) for an inauspicious beginning to the Mets’ best-ever year. How they were often our trading partners for deals good, bad and ugly. How two of the players they honored with retired numbers were also revered by us. And how they ended their existence by being beaten by the Mets, with the final tally Mets 299, Expos 298. Maybe that was the source of my paranoid fantasy — the feeling that in some ways the Expos were a distorted version of us, but with even worse luck. Much worse luck.

And in the end — after the end, in fact — I realized that I did care about the Expos. Greg and I were there for that final Expos game, and I remember looking around in the stands and seeing Expos hats and jerseys. They weren’t everywhere, though give me 20 more years and maybe I’ll say they were. But there were a lot of them, worn in pride and sorrow and defiance and just by way of bearing witness. And I don’t remember a single Shea Stadium lout offering one of those Expos fans typical Shea Stadium hospitality. Even the worst of us knew better. It was our stadium, but we were guests at their wake.

Except the story of the Expos wasn’t quite over. A few weeks later, a collection of players played exhibition games in Japan. On the roster was Brad Wilkerson, wearing a Montreal uniform. (He went 7 for 26, with a home run.)

I’ve never been able to get that out of my head: a lone player, on the other side of the world in the middle of the night, wearing the uniform of a dead franchise. There must have been Montreal fans who figured out how to watch, who tracked Internet updates, who gazed at this final ember of the team they’d loved, until in the early hours of Nov. 14, 2004, Frankie Rodriguez closed out a 5-0 win MLB win and that last little light went dark and there was nothing. There must have been Montreal fans who figured out how to watch, because I know that’s what I would have done, just as it’s what Greg would have done and what a lot of us would have done. Would I have stayed up watching stuttering Web video in Japanese to see a last few swings by, say, Daniel Murphy, wearing the uniform of the team that had been taken from me? You bet I would have. And at the end I would have wondered how many pitches were left and would have wished that he’d foul them off forever, until the world was forced to notice and common decency demand that the clock be turned back so some kind of fairness could prevail.

* * *

Remember: 1986 NLCS, Games Three, Five and Six. Noon to midnight today on the MLB Network.

by Greg Prince on 9 January 2010 12:18 am From noon to midnight today, MLB Network will be showing Games Three, Five and Six of the 1986 National League Championship Series. That’s (spoiler alert!) the Mets beating the Astros on Lenny Dykstra’s walkoff ninth-inning home run; the Mets beating the Astros on Gary Carter’s walkoff twelfth-inning single; and the Mets beating the Astros on Jesse Orosco’s sixteenth-inning hanging on for dear life. That last one’s where they win the pennant, too.

Game Three starts at noon. Game Five starts at three. Game Six starts at seven and practically never ends. The indispensable MLBN reairs Game Three at midnight and Game Five at three in the morning in case you haven’t had enough. And who could get enough of the 1986 NLCS?

Also, the Jets are playing a playoff game at 4:30 PM. I’ll be sure to flip over and check on them during commercials.

If you need or would care for a refresher, the 1986 NLCS was recalled in one fell swoop — whatever the hell a fell swoop is — in this Flashback Friday.

by Greg Prince on 8 January 2010 4:58 pm Andre Dawson’s election to the Hall of Fame conjures up a most frightening vision of a very scary slugger with a terribly lethal bat ready to destroy the next innocent baseball a New York Mets pitcher throws his way. I’ve read grumbles and snorts that Dawson’s career on-base percentage is too low to be worthy of Cooperstown, but I gotta tell ya: as one who gripped pillows, remote controls and anything handy in anxiety when he’d come to the plate to face Ron Darling (.333 batting average against, according to Ultimate Mets Database), Bobby Ojeda (.350), Wally Whitehurst (.400), Pete Falcone (.444), Tom Hausman (.467), Randy Jones (.500), Jesse Orosco (.546) or Kevin Kobel (.625), I surely was not thinking, “Oh good, Dawson’s up — little chance of him drawing a walk here.”

I’ve grown fairly numb to the Hall of Fame process if a Met (or somebody who wore a Mets uniform while lounging for a year-and-a-half) isn’t involved. That includes the “which cap?” dilemma that arises often in these days of frequent player movement. Just as I don’t have it in me to get up in arms about whether or not Fred McGriff‘s a Hall of Famer, I don’t particularly care how his hypothetical plaque portrays him. Dawson, though, is an exception to my apathy rule, because I really hope Andre Dawson goes into the Hall as an Expo.

Nobody goes anywhere as an Expo anymore. It would be nice, now and then, if somebody would.

The further we drift from October 3, 2004, the further we are from actual Expos, and the further we get from them, the more exotic they seem. Did we really used to play them eighteen times a year? How could we have? There are no such things as Expos anymore.

An entire baseball culture evaporated the moment Jeff Keppinger tossed a two-out, ninth-inning ground ball to Craig Brazell (speaking of evaporations) and the Expos lost their last game ever to the Mets. Don’t get me wrong — I was happy the Expos lost to the Mets. I was always happy when the Expos lost to the Mets. But in those final three seasons when Major League baseball in Montreal carried an MLB-mandated death sentence, I was sad we were losing the Expos.

It didn’t feel right. Montreal was not just our divisional rival. They were our spiritual kin. While games were in progress, they might as well have been Padres or Pirates. They were the enemy. But the peripheral stuff appealed to me when I wasn’t worrying about what an Andre Dawson or a Tim Raines or even a John Bocc-a-bella was going to do to us next. I particularly liked the Mets-Expos connection.

• They were expansion like we had been expansion.

• They were named for a World’s Fair while we played next to a World’s Fair.

• They were born bilingual and our first manager spoke fluent Stengelese.

• They wore beanies without propellers while we smushed together blue and orange against a field of pinstripes — and we both looked beautiful as a result.

• We had to send our guys through security to play them up there, and Jeff Kent once got pulled aside by the authorities for carrying a firearm to the airport.

• Jeff Kent had his first reported mental breakdown in the Olympic Stadium visitors clubhouse when his veteran teammates tried the ol’ rookie hazing on him, and Kent — forever winning fiends and influencing people — would not stand for it.

• Youppi and Mr. Met each have loads more personality than Jeff Kent.

This is to say nothing of the player pipeline that spanned the St. Lawrence Seaway south to the Port of Flushing: Rusty Staub, Gary Carter, Ellis Valentine (whoops). There was a lot of action back and forth between the two franchises. The Expos’ first game ever was against the Mets, at Shea (they won). The Expos’ last game ever was against the Mets, at Shea (we won). That 4-3 grounder, Keppinger to Brazell, that ended the Expos’ existence? It was hit by Endy Chavez, former Met farmhand and future Met icon. Endy was acquired for Montreal from New York by Omar Minaya, former New York assistant general manager turned Montreal general manager, a post he held until right before that final Expos series at Shea…when he became New York general manager.

And so it goes. Omar’s still here. Jerry Manuel’s still here. Fernando Tatis is still here. Jason Bay, whom Expo Omar traded to the Mets before Moron Steve traded him to San Diego, has just arrived. So has 2002 Expo first-round draft choice Clint Everts. The Met-Expo link endures more than five years since the Expos went to Washington, which left Montreal to stand in silence as a latter-day Louisville.

Surely you remember the Louisville Colonels. They finished ninth in the twelve-team National League of 1899. Then they were mathematically eliminated forever. Louisville would never again have what we consider major league baseball — National League or, despite the DH, American League. No other standalone city (ahem, Brooklyn) that had an N.L. or A.L. team in the 20th century would be sentenced to a life term with no big league ball. Washington appeared doomed that way for a long while, but they got the Expos. Besides, Washington always seemed destined to get something to make up for their being hosed twice. They did. They got the team that was once beloved by hosers.

It’s for the Canadians who cared and who still might care that I hope Andre Dawson’s plaque shows him as an Expo. He came up as an Expo in September 1976, getting a jump on Steve Henderson for Rookie of the Year the next year and establishing himself as one of the most exciting players and dangerous hitters in North America. Those Expos clubs he and Gary Carter led into pennant races in 1979, 1980 and 1981 (when they clinched their only regular-season crown, the strike-compelled split-season divisional title…at Shea, of course) were ferocious.

They were popular, too. The Expos’ average home gate from 1979 through 1983 always ranked in the top third of league attendance. It wasn’t until the Dawson-Carter-Raines Expos began to fray at the seams like the carpet barely hiding the Big O’s concrete floor that Montreal’s fans began staying away en masse. And it was only once management made clear their entire operation would be permanently threadbare did the Olympic Stadium we remember most vividly — empty and echoey — materialize regularly.

Andre Dawson left the Expos after a decade in Montreal. He was part of the free agent class of 1986-87 that was sideswiped by ownership collusion. The Hawk wound up accepting a below-market, one-year deal from the catbird-seated Cubs — Dawson, so desiring Wrigley’s natural grass as a salve for his turf-battered knees, legendarily signed a blank contract, telling his prospective employers to fill in the amount — and proceeded to tear up the National League from his new perch. He played six seasons in Chicago, the first of them spectacular, most of them fine. The Cubs did for Andre Dawson what the Mets did for Gary Carter: they raised a superstar’s profile to the level where it deserved to be back when that star shone in Quebec.

When the Hall insisted Carter wear an Expos cap on his plaque in 2003, I was disappointed but I understood. There was still a Montreal Expos franchise then, but it was going, going en route to certifiably gone. Kid had a lengthy and worthy track record up there, so it wasn’t an affront to the Mets to present him for posterity as an Expo. I believed there should be something for Expos fans to hang their — and his — hat on.

Now, a second Expo alights in Cooperstown. Andre Dawson is said to prefer the Cubs cap. It wouldn’t be crazy, given the MVP he earned in Chicago in ’87 and his general fearsomeness there through ’92. Plus, the Cubs can hold a press conference to congratulate Dawson. The Expos can’t. The Cubs can have a day for Dawson. The Expos can’t. Cubs fans who cheered for Dawson can perk up some desultory middle inning at Wrigley Field by remembering the time Andre came up and ripped a huge homer to left. Expos fans can’t sit inside Olympic Stadium and do a damn thing.

That’s the best reason I can come up with for Andre Dawson to cast his eternal fate with a defunct franchise. He doesn’t need the Expos, but the Expos could sure use him.

by Jason Fry on 7 January 2010 9:00 am I enjoyed this post yesterday by The Vertex’s Eric Bienenfeld about this year’s Hall of Fame ballot, which included a Met who almost was — Barry Larkin — as well as Roberto Alomar, a Met we could have done without. (Robby will probably get in next year, which would be fine with me — longtime Alomar hater though I am, I’m happy with a speed bump between him and Cooperstown, and don’t need a barricade. For more on the Splendid Spitter, here’s Greg.)

Barry Larkin, you’ll recall, almost became a Met at the trading deadline in 2000, when the team needed a substitute for the sidelined Rey Ordonez. The Mets and Reds worked out a deal, and that weekend Mets games unfolded on TV accompanied by a timer counting down the 72-hour window for the Mets and Larkin to agree on a contract extension, without which he was staying put. The extension never came to pass, Larkin stayed a Red, the Mets traded Melvin Mora to the Orioles for Mike Bordick, and that was that.

If memory serves (and it’s entirely possible it doesn’t), I opposed the trade, because I didn’t want to surrender Alex Escobar. This isn’t surprising — I’ve always overvalued prospects and bought into the hype surrounding ours in particular, which I really ought to get over given ample evidence suggesting one shouldn’t get too excited in theses situations. For the most part, Mets prospects are like Microsoft products were when Microsoft was still relevant — insanely hyped, late to arrive, then painfully buggy.

Nonetheless, I wanted to see Escobar’s bright future blossom in New York, the same way I’d wanted to witness the bright futures of Terrence Long and Jorge Toca and Alex Ochoa and Ricky Otero and Ryan Thompson and other marchers in this mostly sad parade. And when Larkin stayed home, I got my wish. Hooray! Hooray for us all!

Granted, there’s no guarantee Larkin would have been the answer to much of anything: He was pretty much shot after 2000, though it doesn’t seem like a stretch to think he would have topped Bordick’s 4-for-32 performance in the 2000 postseason. Still, yesterday I found myself dreaming about an alternate reality that began with Larkin saying, “Sure, I’d love to play in New York.”

Come away with me, to a very different world….

October 21, 2000: Timo Perez is gazing out at the left-field wall in Yankee Stadium when (as he’ll later tell reporters) he somehow hears a familiar voice through the cacophony of a World Series crowd. It’s Barry Larkin, and what he’s yelling is “Run, stupid!” Larkin later apologizes for the insult, but neither player minds — after all, a chastened Perez scores just ahead of Derek Jeter’s desperate heave, the key play in the Mets’ 4-3 Game 1 win.

October 26, 2000: Larkin, sprawling on his belly behind second base, smothers Luis Sojo’s little bounder up the middle and nips Jorge Posada at the plate, preserving a 2-2 tie in a hard-fought Game 5. In the bottom of the ninth, Mike Piazza’s home run gives the Mets a 3-2 series lead. “I thought it was going to die on the warning track,” Piazza says later, “but something pushed it over the wall. I don’t know, maybe it was me not wanting to let Barry down after all he’s done for us.”

October 28, 2000: Home runs by Larkin, Piazza and a grand slam by Melvin Mora send Roger Clemens to an early exit, chased by boos from a vengeful Yankee Stadium crowd. By the end of the 13-1 assault, the House That Ruth Built has been left to Mets fans exulting in the Amazins’ third World Series title. Buster Olney’s “The Last Night of the Yankee Dynasty” will later look back at this night as the start of everything else to befall the Yankees in later years.

October 29, 2000: An astonishing day in New York sports history, as a team of Daily News reporters arrive at Clemens’ New York City apartment for an interview the Rocket’s agent has forgotten to remind his client about. Admitted to the apartment by a confused nanny, the reporters discover Clemens being injected in the buttocks with an unknown substance by country singer Mindy McCready. An enraged Clemens rampages across the city before being Tazed by New York City police in the middle of the Brooklyn Bridge. Five years later, Clemens’ escalating problems will end with his incarceration in the Hague.

December 11, 2001: George Steinbrenner, still livid over the Yankees’ loss to the Mets and subpar 2001 season, orders a megadeal aimed at restoring the luster to his fallen franchise, acquiring All-Star second baseman Roberto Alomar from the Cleveland Indians for unhappy former stars Derek Jeter and Jorge Posada.

July 1, 2003: The Yankees trade Alomar to the Chicago White Sox after two brutal seasons that tarnish an apparent Hall of Fame career, accompanied by booing, dugout confrontations with his teammates and an on-air blistering by John Sterling. Shortly before the trade, Sterling’s assault on Alomar’s poor effort wins him plaudits, though the good reviews come with left-handed compliments. In the New York Times, Richard Sandomir writes that “given Sterling’s indifferent track record as an announcer and reputation as a homer, a listener can be forgiven for thinking it was almost as if someone else were speaking that day.”

November 6, 2006: Steve Phillips, who parlayed his success as general manager of the New York Mets into an unlikely political career, is elected governor of New York.

May 28, 2007: Baseball owners approve George Steinbrenner’s request to move the Yankees to New Jersey. The team’s relocation to New Jersey for the 2008 season sparks an exodus of Yankee fans from the city. A link between this exodus and a subsequent rise in New York City standardized test scores and perceptions of civility in the city remains hotly debated by scholars and economists.

May 17, 2008: A shocking day for New York as Gov. Phillips steps down, acknowledging reports of serial infidelities that have disgraced his office. In a statement issued on behalf of the Mets, GM Jack Zduriencik says that “while in no way condoning our former governor’s actions, all of us at the New York Mets will remember Steve’s successes in the early part of his decade, and ask that everybody respect his family’s privacy during this difficult time. Our focus will now return to our ongoing celebration of Shea Stadium and all it has meant to our devoted fans, a year-long celebration we hope to cap with a successful defense of our title as World Series champions.”

Interesting world, isn’t it? But it’s not our world. No, in our world Barry Larkin wanted to stay a Red.

Oh well. We’ll always have the memory of Mike Bordick.

|

|