The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 5 October 2007 7:47 pm When the season began, they were nobody. When it ended, they were somebody. If it’s the first Friday of the month, then we’re remembering them in this special 1997 edition of Flashback Friday at Faith and Fear in Flushing.

Ten years, seven Fridays. This is the last of them.

Here’s the crux of it. This is why I remember 1997 so deeply and so fondly and why it resonates so much for me for so long after the fact.

It made me cry.

I’m not being cute about this at all. I’m not going to give you the ol’ “I think there’s something in my eye” bit in telling you what 1997 did for and to me. I’m not going to deny a bit of it. Why deny? I couldn’t be prouder that I violated the Jimmy Dugan edict that there’s no crying in baseball. I like to think I’m the biggest Mets fan you’ll ever meet. I think I proved it to myself on Sunday afternoon, September 28, 1997.

That was the last game of an 88-74 season. I just went to the last game of another 88-74 season. If it made me cry, it was from a culmination of angst and exhaustion and for maybe two seconds while washing my hands in the men’s room after it was over. 2007 provided the kind of ending that made you want to wash your hands of the whole thing right away.

The last day of 1997 wasn’t like that. The last day of 1997 was something beautiful. It was the end of something beautiful.

I’ll never have another season like that. I’ll never again be capable of being surprised like that, of being delightfully surprised like that, of waking up rooting muscles that I assumed had gone permanently dormant. I’ll never again care the care of the innocent, unburdened by cumbersome backstory. Even with 28 previous seasons of Mets fandom in the books, 1997 wiped the slate clean. Past failures were ancient history. Past successes served as useful precedent.

I’ll never be able to enter a season expecting nothing and end it having been given oodles and oodles of something. Another Mets team can come along and do better than expected and it will be gratifying, I’m sure, but it will never sneak up from behind and embrace me like this one did. Once it’s happened once, you can’t be surprised if it happens again.

I’ll never again find myself surprised that I’m so immersed in a particular team or a particular season. I’ll never again be surprised that I find myself believing we can overcome a suffocating opponent or an imposing margin. I’ll never again feel shock that my team that wasn’t supposed to be any good proved to be not bad at all. I’ll never again be stunned by a team winning a little more than it loses even if it had just spent years losing far more than it had won. I’ll probably never again find deep and enduring satisfaction in a season that comes up just a few games short.

But short of what? Maybe you’re wondering how an 88-74 season can be so damn meaningful when you’ve just seen how awful the most recent one was. Context is everything, of course. Coming off a division title and building a record of 83-62 and a lead of 7 games, you’re not going to think much of 88-74.

But after 71-91 and after 69-75 and after 55-58 and after 59-103 and after 72-90 and after 77-84 and after feeling you were eternally consigned to circling a tunnel of irrelevant submediocrity, U-turning from one lousy year into another into another into another…you, the biggest Mets fan you insist anybody will ever meet…you’d think a lot of that.

Especially if it came with possibility. As painstakingly detailed across the previous six Fridays devoted to this topic, it wasn’t just the first winning record since 1990 that sent me over the Met moon in 1997. It was the unforeseen chance that there might be tangible reward. A playoff spot was in reach for the first time since 1990, too. The Mets finished within four games of the Wild Card that year. They competed ferociously for it into August, fell off the hunt a bit as September neared but clung to the legitimate possibility that they, the downtrodden Mets, the laughable Mets, the heirs to futility Mets, the next-of-kin to Anthony Young Mets, the artists formerly known as the fourth-place, 91-loss Mets — that they would make the playoffs. That if they made the playoffs, they could win a division series, a league championship series, a World Series even.

They didn’t, but that’s hardly the point of 1997. They made me believe they could. They made me dream they could. When the dream was dashed for the simple reason that they weren’t quite good enough, it bothered me as little as that sort of thing could bother me. Imagine investing all your fanhood in the hope that your team, on the verge of breaking through all season, actually breaks through. Then it doesn’t. Would you be disappointed?

Weren’t you just recently disappointed?

My 1997 was no more than tinged by disappointment. Not colored by it, certainly not defined by it. Even as I had grown to expect winning baseball from my team across May and June and July, when it didn’t automatically come in August and September, it didn’t kill me. Not because I didn’t expect better, but because I was given the gift of expectation at all. When the season was over, I looked around the sport. Twenty teams missed the playoffs. A few of the other nineteen franchises had probably exceeded their fans’ expectations, but I couldn’t imagine they didn’t feel let down somehow. Of the eight teams in the postseason, seven sets of fans were bound to be crushed by coming so close and falling just shy. The Giants and Braves each lost to the Marlins; that wasn’t supposed to happen. The Yankees and Orioles lost to the Indians; that wasn’t supposed to happen. The Indians watched a Game Seven lead slip away in the ninth inning and with it their first world championship in 49 years; that’s never supposed to happen. The fans of the eventual world champions, the Florida Marlins, got to celebrate heartily for a couple of days before their owner almost immediately ripped their roster apart. That’s totally unheard of.

By Thanksgiving 1997, everybody else who rooted for a baseball team was experiencing some degree of misery. And I was still thrilled and thankful. I’d had a year I couldn’t anticipate and now I couldn’t forget about it, not then, not now.

That’s why I cried on the last day of the season ten years ago. That’s why I was at the last day of the season ten years ago. There was no way I was missing it. I was invited to a wedding on Sunday, September 28, 1997 by a co-worker and fellow Mets fan. I didn’t ask him what the hell he was doing scheduling a wedding on the last day of the season, but I was clear on why I was RSVPing no.

I have a previous engagement, I said. I have another affair to attend.

I went to Shea Stadium alone that Sunday. Couldn’t have possibly gone with anybody else. It had to be me and my team, just us two, even if I was only going to be making the sound of one fan clapping. Technically, we weren’t alone. Paid attendance was announced as 27,176, pretty good for those days. It may even have been fairly accurate. There were apparently others who recognized 1997 for what it was. But I didn’t need to talk to them.

Having been to a very memorable Closing Day in 1985 when the last Mets team to come achingly (if unsurprisingly) close said goodbye by gathering en masse in front of their dugout and tossing their caps in the stands, I decided I wanted to sit in good seats. Maybe I’d catch a cap. Maybe I’d be in the middle of the fuss. Before I had a chance to seek out someone looking to unload the last of his season boxes, someone approached me. A man in his 50s, not very tall, offered me a $25 Metropolitan Club seat for $15. If they weren’t right behind the Mets dugout, they were darn close. I said yes.

Not having dealt that much with either scalpers or non-licensed ticket agents, I wasn’t expecting to sit next to this fellow once inside. But he became my neighbor. When I thanked him for the view, he told me not to thank him, but thank his brother-in-law. They were his company’s seats. Oh, I said, my thanks to him. He couldn’t make it today, huh?

“No, he died the February before last.”

It also turned out this same guy, the one who was living, had some kind of Tourette tic wherein he’d have to repeat every name the public address announcer broadcast (PA: “Now batting: Keith Lockhart”; Strange dude: “Keith Lockhart”). He also brought a glove and held it high in the air with every foul ball that was popped up, no matter where it was heading. And he referred to Astros manager Larry Dierker as Bobby Dierker.

Like I said, I didn’t need to talk to anybody that day.

The Mets were playing the Braves, the Braves who had won their third consecutive Eastern Division crown, the Braves who were forever tuning up for the postseason. The only Met with anything specific to play for was John Olerud, making a sudden rush on 100 runs batted in. He’d been driving them in relentlessly of late. He entered the week with 88 and entered the day with 98. Oly did his part with Olylike precision, doubling home Alfonzo in the fourth and blasting a three-run homer in the fifth. He got to 102 before Bobby Valentine pulled him.

The Mets A/V squad did their part, too. Eschewing the usual promotional rubbish, every half-inning DiamondVision break focused on some aspect of what made 1997 so enjoyable, with several of the vignettes devoted to the team’s Amazin’ Comebacks. There was Oly in May beating the Rockies, Baerga taking it to the Braves in June, Everett and Gilkey executing the most Amazin’ Comeback of them all (down 0-6 in the ninth, winning 9-6 in the eleventh) against the Expos two weeks before. Those of us among the 27,176 who were Closing Day pilgrims applauded each clip heartily. One gentleman sitting in front of me, however, scoffed.

“This is a results-oriented business,” he informed me, “so all this is meaningless.” He went on to downgrade these Mets, scoffing in particular at the acquisition of “Hal McRae.”

Brian McRae, I said. The Mets got Brian McRae, the son of Hal McRae.

He shrugged. “I stopped following the Mets when Frank Cashen traded Kevin Mitchell.”

“So,” I asked, “why are you here?”

He pointed to his son. The kid dragged him to the game. Fortunately, the kid lost interest around the time Olerud was reaching the century mark and Dr. Buzzkill exited the premises. Yet another good thing about this season. His departure meant an empty nearby seat that allowed me the chance to slip away from the glove-and-repeat guy.

It wouldn’t have really mattered had the Mets not won this game, but that wasn’t the sort of thing the 1997 Mets wouldn’t do. Of course they won. The Braves may have been checking travel itineraries, but the Mets were playing exactly as Bobby V had had them playing all year, living up to his mantra that the most important game of the season was the one they were playing next. Olerud’s homer had made it 5-2. Alberto Castillo and Rey Ordoñez tacked on a run apiece in the sixth. And Matt Franco launched one over the right field wall to lead off the eighth. That made it 8-2 Mets. That would be the final.

The excitement was building among the truly faithful. PA announcer Del DeMontreaux had urged us all afternoon to stick around after the final out for the end-of-year video tribute to the season. When the Mets had something to salute, they usually did it very well. In 1985, they set their highlights to Sinatra’s “Here’s To The Winners”. In ’88, they used “Back In The High Life” by Steve Winwood. I couldn’t wait.

I really couldn’t. After Greg McMichael retired Rafael Belliard for the first out of the ninth, I stood up in front of my Metropolitan Club seat and started clapping. I wasn’t alone. The anticipation for a final out that wasn’t going to clinch anything was overwhelming. When Greg Colbrunn flied out to Carlos Mendoza in left, the applause and the shouting rose. Everybody was now standing. You wouldn’t have known there was no postseason for us. You wouldn’t have known this wasn’t the postseason. I had my Walkman on and heard Gary Cohen describe the scene with surprise. Yes, he said, I guess it had been a good year. These fans are certainly enjoying the last of it.

McMichael worked the count 0-2 to Andruw Jones. Then he struck him out swinging. The Mets won. The season was over.

The roar was incredible. The Mets burst out of their dugout, not to celebrate beating the Braves, just to celebrate, at the very end of what they had accomplished, themselves.

They stood as we stood. They watched as we watched. The DiamondVision blinked on and we heard Gloria Estefan:

If I could reach

Higher

Just for one moment

Touch the sky

From that one moment

In my life

There the 1997 Mets were again. Keeping me up late from California. Winning the first battle of New York. Keeping pace as long as they could with a dream that came from I don’t know where. There were walkoff hits and clutch strikeouts and sensational grabs in the hole. There the Mets were, up on that screen, doing everything that made me stand up when there was one out in the ninth and made me start applauding — and crying — before the game was put in the books.

Yes, I was in full lachry-mode. There was a rain delay behind my glasses and no tarp capable of keeping the field dry. I could not stop bawling. And I made no attempt to stop. Neither did at least three other people standing in my midst. There were two fans who held each other tight like it was New Year’s Eve during wartime. I wasn’t the only one who had come to Shea today for this. I didn’t come to this game alone after all.

The video ended. The crowd cheered. I kept crying. I never did that for baseball before. Then I did something else I had never done. I climbed on my seat and began chanting LET’S GO METS! LET’S GO METS! Others followed. Maybe they would have done so without my lead.

The players waved, Todd Hundley among them. Hundley had left the team for elbow surgery a few days earlier. He emerged from the dugout in street clothes. Of course he was coming back for the final day, he told a reporter after the game — he wasn’t going to miss the video for anything. Carlos Baerga was out there, too. Baerga was booed fairly frequently since becoming a Met, since becoming the latest in a long line of Mets who didn’t live up to their previous billing. When I eventually saw highlights of the lovefest on TV, I saw Carlos Baerga standing on the field wiping a tear from his eyes.

I was still crying as it ended. The players threw their caps to the fans immediately behind their dugout, and I was still crying — and not because I was too far back to get a cap. We were thanked for coming, and I was still crying — and not because there was no game tomorrow. All attempts to compose myself failed. I left Shea crying, I boarded the 7 train crying, I waited at Woodside crying, I cried the whole way home until I finally forced myself to cut it out as the LIRR pulled into East Rockaway. I walked from the station to our house, came up the steps of our apartment, and as I began to describe for Stephanie what the day had been like, I started crying all over again.

Next Friday: The Champagne of centerfielders.

by Greg Prince on 5 October 2007 8:47 am I’m still working on Flashback Friday as regards the final game of the season ten years ago, but I thought it would be interesting in the interim to provide some emotion-free context for 1997.

Twenty-four men became New York Mets for the first time in 1997. Four of them — John Olerud, Rick Reed, Todd Pratt and Turk Wendell — would become mainstays of the Mets club that broke the franchise playoff drought in 1999. A few of them — the balk-magnet Steve Bieser, the first Met Japanese pitcher Takashi Kashiwada, human gas can Mel Rojas — gained a degree of triviality or infamy during their short stays. One — Cory Lidle — is no longer with us.

Most simply came and went. It would take a hardcore collector of data or baseball cards to recall with much depth the Met tenures of Yorkis Perez or Gary Thurman or Carlos Mendoza or Barry Manuel or Shawn Gilbert or one-game wonder (one inning at third) Kevin Morgan. Half of the 24 new Mets of 1997 never played with the Mets again.

Forty-five men in all were Mets in 1997, 21 of whom had previous Met experience. Five of those holdovers — John Franco, Edgardo Alfonzo, Bobby Jones, Matt Franco and Rey Ordoñez — would see postseason action with the club in ’99 and/or 2000. Nine of them, including the traded Lance Johnson and the caustic Carl Everett, would not be Mets beyond ’97. John Franco, who predated all his 1997 teammates in Queens, remained a Met the longest, through 2004. While Alfonzo and Everett were Long Island Ducks this past summer, Jason Isringhausen is the only player from that ’97 team to finish 2007 on a big league roster.

Roberto Petagine was the only Doubleday Award Winner to be recalled to the majors in September. The only future Mets to be recognized as top minor leaguers in the farm system that season were Grant Roberts (Capital City) and Endy Chavez (Gulf Coast). The top pick in the amateur draft that June was lefty pitcher Geoff Goetz. The most notable selection to eventually play for the Mets was Jason Phillips, chosen in the 24th round.

Snow white uniforms were introduced as “Sunday-only” togs, but eventually supplanted the pinstripes as the de facto primary uniform of the sartorially confused Mets over the next decade (black was added to the wardrobe in ’98). The white “ice cream” caps with blue bills intended to accompany them faded quickly, however, disappearing from player’s heads by June. Uniform number 42 went up on the left field wall April 15, as Jackie Robinson’s entry into the major leagues was honored first and foremost at Shea Stadium by the pioneer’s widow, the commissioner of baseball and the president of the United States. Every team, including the Mets, wore a right-sleeve patch commemorating the 50th anniversary of Robinson’s breaking the sport’s color line.

On the promotional front, 1997 introduced us to International Week, postgame Merengue concerts, Kids Opening Day and a one-off sunglasses giveaway sponsored by American Sports Classics, a Cablevision-planned rival to Classic Sports Network (now ESPN Classic) that never got off the ground. Fans of legal drinking age were presented on August 10 with a narrow “cooler bag” designed to accommodate several cans of beer; it looked more like a belt than a bag.

Interleague play provided the most substantial alteration for 1997. Of course National vs. American meant the first Subway Series and the attendant legend of Dave Mlicki, who shut out the Yankees 6-0 in the first crosstown meeting at Yankee Stadium on June 16. Overall, the Mets compiled a 7-8 record versus the American League East, which then included Detroit, where the Mets visited Tiger Stadium for the first and only time. Their initial Interleague game was against the Red Sox at Shea. The Mets’ competition for the Wild Card, the Marlins, went 12-3 against A.L. Teams, meaning the Mets actually owned a better record in intraleague play than the team that beat them out of a playoff spot.

Mets games were cablecast on SportsChannel for the final time in 1997; the outlet’s name would change to Fox Sports New York a year later. It was also the final season Coca-Cola would be poured at Shea Stadium and the final year before the addition of Milwaukee and Arizona to what had been the fourteen-team N.L. The Mets would lose Lidle (Diamondbacks) and Mendoza (Devil Rays) in the November expansion draft.

In Bobby Valentine’s first full season as manager — Steve Phillips succeeded Joe McIlvaine as GM on July 16 — 1997’s record represented an improvement of 17 games over 1996, the third-best one-year improvement in Mets history, following only those generated in 1969 (27 games) and 1984 (22 games). Bobby Jones and Todd Hundley represented the Mets as All-Stars, though Hundley was injured and did not make the trip to Jacobs Field. Hundley, who graced the 1997 yearbook cover in a holographic rendering of his record-setting home run from the September before (most by a catcher), led the team in homers again with 30. Butch Huskey was second with 24. The other catcher named Todd, Pratt, homered in his first Met at-bat, off the Marlins’ Al Leiter in early July. Olerud cracked the 100-RBI mark on the final day of the year, finishing with 102. He also hit for the cycle on September 11. Alfonzo, graduating from utilityman to everyday third baseman (no Met had played the position more in one season since Hubie Brooks in 1983) was the team’s leading hitter at .315, good for eighth overall in the senior circuit; he was also the only Met to gain MVP votes, finishing 13th in the balloting. Ordoñez’s acrobatics earned him his first Gold Glove at short.

Jones, who struck out the two most prominent sluggers of the year (Mark McGwire and Ken Griffey) in the All-Star Game, led the pitching staff with 15 wins, while Reed, enjoying one of the great surprise seasons in Mets history, pitched to the lowest ERA on the team at 2.89 — sixth best in the National League. Reed, Mark Clark and Armando Reynoso each homered, making it the only season in which three different Met pitchers went deep. John Franco saved 36 games, fourth-most in the N.L. Greg McMichael was the workhorse with 73 appearances. Pete Harnisch started Opening Day in San Diego, though did not finish the year as a Met, sharing that unusual footnote with Mike Torrez (1984).

The season opener at Jack Murphy Stadium was the Mets’ first in California since 1968. After nine mostly ragged games out west, the Mets took the unusual step of slating their Home Opener for a Saturday in deference to the Yankees raising their first World Series flag in 18 years one day earlier, but rain pushed the Mets into opening up with a downbeat Sunday doubleheader attended by fewer than 22,000 fans, the lowest total since 1981. The season’s attendance of almost 1.77 million was the Mets’ best in four years and the last time, presumably, that the Mets would fail to draw 2 million to Shea. One scheduling quirk unique to 1997 was the playing of 17 separate two-game series (squeezed in to accommodate Interleague and disliked by all concerned) and five “wraparound” Friday-Monday four-game sets. It was all laid out in pocket schedules whose covers were graced by Gilkey or, later, Hundley.

No team in the majors came from behind more often to win than the Mets, who did it 47 times. Ten of the Mets’ victories were of the walkoff variety, including three on home runs (Olerud, Everett and Bernard Gilkey). The come-from-behind vibe echoed the Mets’ performance in general, as their 80-60 record from April 27 to the end of the season was second only to the Braves in all of the National League over that five-month span. The final 140 games erased the season’s unpleasant 8-14 start, even if it wasn’t quite enough to lift the Mets past Florida and into their first Wild Card.

by Greg Prince on 4 October 2007 4:06 pm I may have accidentally made sense eight months ago:

Don't know if it's still conventional wisdom in baseball circles to define a player's prime as more or less the ages of 28-32. Since conventional wisdom never dies, probably. But if that's the prime — when you're old enough to know better and young enough to successfully implement what you know — we lack prime time on our team…

Other than Carlos Beltran Superstar, 30 as of April 24, nobody among frontline Mets is in his prime by traditional standards. But when were these traditional standards set? Probably when average life expectancy, to say nothing of typical career endurance, was a whole lot lighter. Yet this mildly freakish two young/one prime/three kinda old/one rather old/one practically my age demography has been nagging at me a bit as the wind chill turns these venerable bones cranky.

Selective cutting and pasting omits my February rationalization that everything was going to be fine, that the young Reyes and Wright along with the old Lo Duca, Delgado, Valentin, Alou and Green would mesh wonderfully with Beltran and we'd all be figuratively making love to Betty Grable on the White House lawn by Christmas.

To be honest, I'd forgotten this momentary age-related anxiety until after the season was prematurely over and I looked around and thought, man, almost everybody on this team was either too old or too young. Or, more accurately, too injury-prone or too immature. Most of those added on both ends of the age spectrum throughout the campaign fell into those categories as well.

Obviously vintage isn't everything. David Wright is extraordinarily developmentally advanced (except maybe in the field) while Moises Alou apparently stole the soul of a much younger man in September. Nobody was checking birth certificates in Philadelphia, but now that I'm looking at their roster, they sure do have an everyday nucleus that seems a little more geared to peaking. Just about every key player was between 26 and 31 this year.

As I've heard myself say to myself many times since Sunday, I don't know, I just don't know. But maybe it was more of a warning sign than could have been appreciated last winter when merely being the Mets seemed license to print playoff tickets well in advance of Opening Day.

by Greg Prince on 3 October 2007 7:11 pm TBS' postgame show will be presented by Captain Morgan Rum. What a coincidence. So is my week.

As the Phillies and Rockies prepared to kick off (take Colorado +3), I found one thing to take solace in. And it's a reach, but what the hell — it's not like I'm reaching into my pocket for Game One tickets.

At the All-Star Break, which is one of those junctures you're supposed to look at for who's leading and where they'll wind up, the four National League representatives to the 2007 postseason were set to be the Mets, the Brewers, the Padres and the Dodgers. I'm sure there were Power Rankings backing up that likelihood. For that matter, the Tigers looked like a lock in the A.L.

The teams that usurped the places of those teams were only marginally on the radar. The Diamondbacks were 3-1/2 out in the West. The Cubs were 4-1/2 out in the Central, one game over .500. The Phillies were the same length back in the East and at .500, behind us and the Braves. The Rockies were four from the Wild Card and also at .500. And in the American League, the Yankees were .500 and eight out of the Wild Card.

No, this does not make anybody feel better but there is a nugget of evidence that we are not alone in being on the outside looking in this week after thinking otherwise.

Maybe we can round up the not-quites and set up a tournament.

Getting more rest, at least. I drifted off while watching Baseball Tonight after midnight, but stirred long enough to see they were counting down the ten biggest moments of the year. Too groggy to follow the numerical narrative, I saw Matt Holliday sort of crossing home plate and figured it was No. 1. Next thing I heard was “greatest collapse in September baseball history” and thought, no, don't tell me…turns out we were only the No. 2 story of the year.

Never thought I'd say this, but thank heavens for Barry Bonds.

So, did watching the Cardinals accept their World Series rings inspire the Mets or what?

Finally, happy 56th anniversary to the Shot Heard 'Round the World. Next time ownership decides to model our team on one of its predecessors, can we look a little to the one that didn't blow a 13-1/2 game lead for inspiration?

by Jason Fry on 3 October 2007 1:03 am

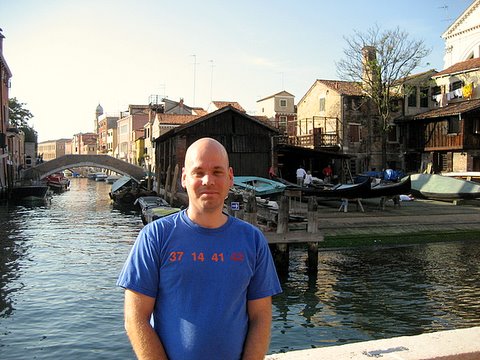

| Last month as the Mets were struggling to stay above water, Jace went to a city that could say the same, as chronicled here. For more about my adventures and misadventures trying to follow the Mets from overseas, see yesterday’s Real Time column from the Online Journal.If you’ve never been and get the chance, go to Venice. It is so worth it, even during a pennant race.We hope to have more Faith and Fear shirts soon — in the meantime, if you’ve got a snapshot of yourself bringing the colors to a new part of the world, send it to us and we’d be honored to put it up. |

|

|

by Jason Fry on 2 October 2007 2:30 pm

Charlie Hangley on the left, Jason on the right. Snapped a month ago, perhaps an hour after Pedro completed his triumphant comeback, on a sunny afternoon on Long Beach Island. Would have been posted earlier, but ran afoul of the magic-number countdown. About which the less said the better. Don’t worry, Charlie and Jace. Summer will return, LBI will still be there and we’ll all feel differently about the Mets. It’s a promise.

by Greg Prince on 2 October 2007 10:13 am Before any of us could have known what the last day of this season would represent for all time, it was just going to be the last day of the season. I like to go to the last day of the season, probably even more than the first day of the season, though I like going to that, too. I was at Shea on Opening Day this year thanks to a Faith and Fear reader named Jodie. It turned out we were long-lost, non-identical twin siblings…if you factor in vintage, heritage and passion for our baseball team and discount blood relations or anything DNAish. Jodie invited me to Opening Day. I said yes, and we won. Seemed appropriate that I invite my sister-of-sorts to Closing Day. She said yes, and we lost for the ages.

After it was over, she surmised she should have bought the tickets. When Jodie buys the tickets and I go — Opening Day, the Saturday night game against the A’s when she couldn’t make it, the instant-classic John Maine one-hitter — the Mets win. When I buy the tickets and she goes — Closing Day — the Mets complete what is now known far and wide as The Worst Collapse In Baseball History.

Next time, Jodie buys the tickets.

Epic tumbles notwithstanding, I like to see the home season to its conclusion. It’s intended to inoculate me against the offseason doldrums, though its preventive powers are fairly transient. Sometimes you get a good game and it will keep you going for a little while. Sometimes you get a stinker and you can tell yourself, eh, that’s OK, at least you saw a baseball game before there weren’t any more.

Once, and hopefully only once, you get what we got Sunday. Or didn’t get. The details are quite familiar to you by now, so if you don’t mind, I’ll just skip ahead Mets Fast Forward-style to what wasn’t — praise be — in the boxscore.

With Luis Castillo striking out with two down in the ninth on Sunday, a baseball season was completed. Like the Mets themselves, 2007 at Shea Stadium vanished in a flash. We 54,453 who witnessed it would never forget it, albeit for all the wrong reasons, but institutional amnesia set in immediately. I’ve been to fifteen Closing Days at Shea. I thought I knew all the postscripts: warm…celebratory…indifferent…anticipant…relieved…sad. But the actual moment of official appraisal for these Mets? Nada. The Mets turned off the figurative lights as soon as they could. If you didn’t know it was the end of September, the end of the season, you wouldn’t have thought a year had just been put eternally in the books.

In past years, the better ones, the players would assemble on the field, particularly if there were no road games remaining. They would wave. They would autograph. They would toss a cap or two. Go try and find a Met on Sunday who wasn’t hustling into the clubhouse at the end of this trying day at the end of this trying month (when the whole concept of “trying” seemed alien to certain Mets).

Once we went final, the Marlins rushed each other as if they had won something more than their 71st game; their relievers raced in from the bullpen faster than they had for Saturday’s brawl. Backs slapped, they filtered into their clubhouse, presumably to toast their rousing last-place finish. Without Marlins and without Mets, the field belonged to the grounds crew. A few workers took to the plate and the mound for a little manicuring. Maybe they were ordered to keep up appearances in case the Nats scored six quick runs in Philadelphia. More likely, they were just securing the summer house before the last ferry out of Avalon. I wondered how soon they’d disassemble the special VIP boxes by the dugouts, the ones set up for the playoffs that weren’t to be.

The Mets dugout was now conspicuously devoid of Mets. The only uniformed personnel apparent were a couple of batboys rounding up equipment and whisking away the remains of 81 days. These kids’ uniforms said Mets 07 on the front. Even from the upper deck, they didn’t look like big leaguers. Then again, neither did the Mets.

On the scoreboard — to the left and right of the brand new Budweiser ad that heralded The Great American Lager and was no doubt supposed to show up behind every fly ball to center on TV in the coming weeks — the Marlin and Met lineups disappeared instantly. The out-of-town scores stayed lit just long enough to confirm what everybody assumed: F WAS 1 PHI 6. Then those, too, vanished. History was erased as fast as it could be. The end of summer is truly a blank scoreboard.

The colorful message displays generated only a generic THANKS FOR COMING. “Thanks for coming”? It could have been April. It could have been June. No acknowledgement that it was the last day of September. Not even a nod to the record-breaking attendance of 3,853,955. Certainly no video presentation of 2007 highlights, no chance to relive the 159 golden days when the Mets held first place. If there was such a film in the can, it wasn’t about to be fired up. Probably good thinking given that nobody cared any longer about the story arc that got us to this final scene.

The music over the PA was muted. First, we heard Coldplay:

Nobody said it was easy

Oh it’s such a shame for us to part

Nobody said it was easy

No one ever said it would be so hard

Then, at an even lower volume, Barry Manilow:

I turn my head away

To hide the helpless tears

Oh how I hate to see October go

I hadn’t sat in the stands this long after a game since the division-clincher in 2006. Then it was smuggled Champagne and uninhibited jubilation and Takin’ Care Of Business. Now everything just grew emptier and emptier, quieter and quieter. Upper Deck boxes 746 and 744 cleared out bit by bit. The last fans in our ad hoc neighborhood were intent on picking up every last red Bud bottle with a Mets logo for safe keeping. As they left, one of them said to us that there’s always next year. I tipped my cap in silence.

I wondered if we’d be told to move it along by security. Would be the Mets thing to do, ending the season on you before you’re quite ready to go. A couple of ushers chatted on the walkway above us, but they didn’t bother anybody. They probably knew from Closing Day stragglers. We each lingered unmolested, Jodie in her thoughts, I in mine, the family resemblance uncanny. I looked around. Still a few of the extraordinarily faithful dotting the red seats. The SNY cameras don’t reach up there, but the disappointment was no less tangible than what was shown repeatedly from the field level on that night’s local newscasts.

I looked around some more. Blue sky, punctuated by a few of Bob Murphy’s clouds. Perfect day if you didn’t know any better. I was sitting in shirtsleeves outdoors as if I were always going to be doing that, as if that’s what people do everyday, as if that’s what I would be doing for the next six months because that’s what I’d been doing so often for the last six months. It was occurring to me that I would not be doing this anymore for quite a while.

I turned my view left and observed the left field cutoff. It’s where Section 48 ends, as if they ran through their construction budget before they could tack on a Section 50. Of all that is familiar to me about Shea, it is that view of the way the upper deck cuts off and becomes sky that strikes me as most iconic. I saw it on television when I was six and it instantly said Shea to me. I knew a player traded to the Mets had truly become a Met when he had his publicity photo taken with that particular backdrop of seats and sky over his right shoulder. In 1994, they added the Tommie Agee marker up there. It serves to commemorate the longest fair home run ever hit at Shea Stadium but also as a warning track for those who would venture that high up and that far out: walk too much further, and you will become puffy and cumulus if you’re not careful.

That view…it will be gone after next season. Whatever angles the successor to Shea Stadium provides, they will not have that feeling of infinity to them. Come to think of it, Jeff Wilpon has already gone on record, quite proudly, as describing Citi Field as “a ballpark that will envelop you.” Hmm…I’ve always liked the way the ends of Section 48 in left and Section 47 in right, cutting off and revealing heavens, achieve precisely the opposite effect. They give you the impression that if you sit in Shea Stadium, you can see the world open up before you, offering a rare vantage point of unlimited possibility.

If 2007 taught us anything — and as Closing Day reminds us annually — baseball is more finite than that. Baseball seasons aren’t permanent structures any more than your current baseball stadium is. The schedule you worked around does end. The team you knew inside and out does disband. Your season comes, your season goes. You live in it when it’s here, you roam around looking at your watch waiting for the next one to arrive so you can move in as soon as they’ll let you. You always miss the old one like crazy in the interregnum because, at base, it was the last one you had. Even if it wasn’t as wonderful as you’d projected. Even if it fell out from under you.

Jodie and I concluded our concomitant contemplations and rose from Upper Deck Box 746B, Seats 7 and 8. We turned our backs on the field that I watched so intently from plastic seats like these 35 separate times in 2007, including the final five dates of the year. I’d been at Shea since Wednesday night, essentially leaving just long enough to nap, shower, change and commute back. I had earlier in the season become surprisingly used to coming here as a matter of course, as if watching home games from my couch was the anomaly. Now I was so used to being here that it was strange to realize I was leaving it for six months, that I was going to nap, shower, change and then do something else altogether until April.

Our backs were soon turned on the upper deck, then the mezzanine, then the loge and the rest. I had grown used to living inside a baseball season. As badly as this baseball season had ended, I always regret walking down its last ramp.

by Greg Prince on 2 October 2007 5:07 am Did you know the National League season just ended like half-an-hour ago? Yes, that was the Rockies and Padres pre-empting Family Guy on TBS. And it was quite a game.

Didn't watch every pitch of it (Stephanie was shocked that I wanted to watch any of it after my nonstop despondency since 4:30 PM Sunday), but found the back-and-forth fascinating. It was 6-6 through 12, when ex-Met Clint Hurdle sent ex-Met Jorge Julio into pitch and make it 8-6. But those indefatigable Rockies, on a leadoff double by ex-Met Kaz Matsui (whom I urged on vociferously, to my genuine surprise), tied that bad boy in no time off the Julioesque Trevor Hoffman (does he ever get a big save?). Troy Tulowitzki doubled home Kaz; then Matt Holliday, a more authentic MVP candidate than anybody in Queens, sadly, tripled home Tulowitzki. Helton was intentionally walked so Trevor could face Jamey Carroll, ex-Expo whom I always dreaded. Carroll was batting behind Helton because Hurdle pinch-ran him for Garrett Atkins; I missed that when it happened, but it didn't seem like a great idea in the 13th. But Carroll lined it to Brian Giles in medium-deep right and Giles, a good arm, fired home.

Michael Barrett, yet another ex-Expo who drove me nuts, blocked the plate beautifully. Holliday tried to slide to the outer edge of the plate but didn't touch it. Yet Barrett didn't handle the ball and Tim McClelland seemed more flummoxed than usual. The ball rolled around behind the plate while Holliday bloodied his face in the dirt. Barrett ran to pick up the ball and tag the dazed Holliday, but McClelland, after about an eternity, called him safe and the Wild Card belonged to Colorado, 9-8.

No argument from the Padres. Too crazy around the plate: Rockies descending on Holliday; trainer tending to his face (at first, Matt didn't get up, but he walked away all right); t-shirts and caps distributed. TBS did a lousy job of covering the moment of truth but offered the angles eventually.

Not sure if it was a great game, but it was a long one. And it felt, I don't know, fun to watch without the weight of worry that had attached itself to everything I had my eye on for the last couple of weeks. I'm sorry the Rockies aren't next flying to New York instead of Philadelphia, but I think I might actually look in on these playoffs sooner than I'd planned. I didn't think I was going to want to watch any of them.

There are teams I like a little in this postseason and some teams of whom I'm not fond. But I don't have a favorite and I'm really not in a mood to root against. Let's Go Baseball, I guess.

by Jason Fry on 1 October 2007 11:00 am When it was over, when the disaster was complete, Joshua began to cry. That's the thing about being four — up until the third strike on Castillo, he really believed the Mets were going to win. It didn't matter that the Nationals were down 6-1 with two out in the ninth. He believed in them, too. When both of those beliefs were revealed as fantasies, he was genuinely astonished and grief-stricken.

I scooped him up and patted the back of his WRIGHT 5 shirt and said fatherly things. I told him that there were little kids and Moms and Dads who are Phillie fans who are really happy right now. (There are. It's true. I even know some of them.) I told him that in order to have miracles, you have to accept the possibility of disasters. I told him that this was the worst thing that had ever happened to a team in September, which meant he'll probably go his entire lifetime without another death spiral like this one. I tried to tell him that there was still baseball to watch, that it might be fun to root the Phillies or the Cubs or the Indians on to a championship.

It occurred to me, halfway through, that I might really be trying to comfort myself. But that wasn't it. Because I was OK.

No, I'm serious. I really was.

And coming from someone as fanatical as me, that should stand as one of the ultimate indictments of the 2007 New York Mets.

This isn't to say I was happy. By 12:15 I was losing track of conversations and spacing out, aware that game time was near and I had to get myself home. As Glavine neared fatal impact, I was unmanned by rage and unleashed a torrent of words not acceptable in our household. (Joshua: “Daddy, please don't say bad words.” Followed, moments later, by “this is the worstest game ever!”) When Ramon Castro lowered his hand, triumph derailed, I let out a scream of torment.

But after that, I was calm. Unhappy, but calm. The Mets lost. I watched the fans stare at the field and listened to Gary and Ron and Keith prattle on about the crew until word came that the Nationals had lost. And then I got on with my day.

I never liked this team. Early on, when they were ahead of last year's pace, I was vaguely embarrassed by this. Like a lot of us, I found myself groping for explanations, and worrying about why they left me cold. Was this the ugly side of raised expectations? Of the first stages of hegemony? Was this how being a Yankee fan began? What wasn't to like?

But I struggled to warm to them during the spring, and when they stumbled through the summer I stopped fighting it. I let a bit of hard-earned cynicism take over, dissecting fandom like social scientists examine human attachment. I told myself that when they made the playoffs, I'd find myself liking them just fine. But then the second half of September came, with the second horrible body blow administered by the Phillies, the inept handling of the pitching staff, the idiotic displays of temper, and the repeated assheaded baseball. And finally, those horrifying quotes by Delgado and Glavine and Pedro, the astonishing admissions that yeah, the team was bored and complacent. That right there was the end of the pretending that I would change my mind.

And that, oddly, made the rest easier. I will always love the 1985, 1999 and 2006 teams, despite the fact that they never won titles. I was never going to like this one, even if it wound up rolling down the Canyon of Heroes. (Maybe that's a massive rationalization. I wouldn't know — until now, I hadn't had any experience analyzing my feelings after the worst collapse in major-league history.) The 2007 Mets were the smug, self-satisfied hare to the tortoises of Philadelphia and San Diego and Colorado. Badly constructed and badly led, in the end they got exactly what they deserved.

After it was over, Emily and I watched in bewilderment as a few stubborn fans remained behind the dugout. What could they possibly be waiting for? I actually hoped they wanted stuff to sell on eBay, because the alternative was so pathetic: At the conclusion of this self-inflicted disaster, who would want to lay eyes on a single member of this band of choking loafers or their bloodless, self-deluding leadership?

There were fans crying after that third out. I cried last year, but why would I shed a tear for this team? For whom, exactly? For Tom Glavine, now undressed and revealed as the Frank Viola of his Met generation? For Willie Randolph, who never stopped issuing pronouncements about winners from the mountaintop while his team died in the valley? For Jose Reyes, regressing before our eyes as a ballplayer? For Billy Wagner, running his mouth and then trying to weasel out of his own words? For Lastings Milledge, jogging after balls with the season hanging by a thread? Those crying fans had never been complacent or bored. They hadn't decided they were such good fans that they could start caring when they needed to. In the end, they cared far more than those to whom they'd entrusted their hopes.

There are 2007 Mets I never want to see again. There are others I'll forgive and find myself cheering for with all the wild hope of fandom. But I didn't want to see any of them after that final out. I didn't even want to think about them. I know that will change, but I can't tell you when it will be. And yet those fans waited behind the dugout, the stadium emptying around them, the season dead. Why would they possibly want these Mets to return?

And finally I thought of something.

“Maybe,” I said to Emily, “they've filled their pockets with rocks.”

by Greg Prince on 30 September 2007 11:46 pm Obviously, I retract every remotely positive thing I ever said about Tom Glavine. Fucking Brave can go fuck himself straight back to Fucklanta.

Obviously, I retract every remotely positive thing I ever said about Jose Reyes. When you go to winter ball, work on hitting the ball on a line and don’t be chummy with Miguel Olivo. AND RUN!

Obviously, I retract every remotely positive thing I ever said about Willie Randolph. Your lifetime streak of winning is over. Check for a pulse while you’re at it.

Obviously, I retract every remotely positive thing I ever said about Omar Minaya. Jason Vargas? Ben Johnson? Ambiorix Burgos? Way to stockpile.

Obviously, I retract every remotely positive thing I ever said about the 2007 New York Mets. Believe in the tooth fairy before you ever believe in a bunch of stiffs that can’t beat its closest competition, can’t beat dreadful competition, can’t beat itself in a race to nowhere.

Obviously, I am disgusted. I was certain I was going to sit down and give you eloquent and reflective, but in fact I am angry and pissed. Eloquent and reflective is still simmering inside me but angry and pissed is boiling over.

What a fucking bunch of losers. With a handful of exceptions, they either did not play to their capability or they were not capable. In some realm I am able to look past that and say “well, I’m sure they were trying.” What evidence there would be to back up that assertion, however, is beyond me. There was a handful of exceptions, but this entire team and this entire organization is at fault for this collapse of historic, immense and confounding proportions. The broad brush of failure doesn’t ask questions, so I apologize to the handful of New York Mets who pushed themselves and generated the performance necessary to win the requisite number of baseball games required to ensure a continuation of their 2007. I would single you out as the exceptions, but this has to be a blanket indictment.

You all sucked.

It is not crucial that your team win championships or earn playoff berths every year. That’s not what being a fan is about. If it were, there would eventually be no fans. But at some point, you have to be able to trust your team to follow through on its position in the game, in the standings, in your hopes. You have to be able to count on a team that has led its division consistently for virtually an entire season to finish the job. Yes, it’s a job. The Mets’ job was to win a division which was in their firm control as late as the second week of September.

They did not do their job. They did not go down to the wire with the heart of a champion or guts of a contender. They went down to last-place teams and next-to-last-place teams. They went down, on-field hijinks Saturday notwithstanding, without a fight. They went down like a doormat. Gallingest among the much that was galling was how the Florida Marlins made it their business to destroy the Mets on Sunday and they were not stopped in pursuit of their goal. Just because some bitchy last-place team wants to beat you doesn’t mean they should or they can. Unless that bitchy last-place team is playing the 2007 Mets. Then the doormat’s right here, go ahead, wipe your feet on us.

What’s remarkable about these Mets’ losing these past two weeks is how uniform and universal it was. Even in the contests in which they blew leads, there was never any great feeling that, oh, they came so close, if only this or that had gone their way they would have pulled it out. They were on a collision course with failure and they smacked head on into it, baby. Full fucking force into a full fucking farce.

In the aftermath of the 27th out of the 162nd and absolutely final game for the 2007 Mets, some jagoff in the upper deck put a paper bag over his head and said “I’m ashamed to be a Mets fan,” to which I said, “I’m ashamed that you’re a Mets fan, too.” But even without the prop comedy shtick, I get it. The Mets are shameful. But I’m not ashamed that I’m a Mets fan.

I’m ashamed of the Mets, but I did fine. I did all I could. I supported my team the way I’m supposed to, by sticking with them and exhorting others to do so and paying my good money (not incidentally) for the privilege to do so. If you’re reading this, I know you did what you were supposed to do, too. We collectively came through. Mets fans have nothing to be ashamed of. We are not our team, after all. We are better than them.

I hope they regroup and meet the standard we have set for them. We’ll be waiting. At least I know I will.

|

|