The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 13 July 2007 3:32 am Go somewhere.

Hit traffic.

Run late.

Sit in car.

Turn on game.

Reyes homers.

Gotay homers.

History made.

Traffic eases.

Get there.

Do thing.

Get back in car.

Wagner closes.

Mets win.

Save for crawling on the Cross Bronx and missing the middle seven innings, may the rest of the second half be that simple.

by Jason Fry on 12 July 2007 4:41 pm Tonight the Mets will kick off the remaining 75/162th of the season at Shea, against the Cincinnati Reds. Bronson Arroyo will face Orlando Hernandez. Lastings Milledge may be patrolling left.

If I close my eyes I can imagine what Lastings' face will look like between his cap and the top of his jersey — a little bit of bravado, a little bit of uncertainty. I can easily picture El Duque's chin tucked against his shoulder as his knee scrapes the sky. Whatever role he's in, I can picture Rickey Henderson laughing in the dugout, still looking like he can play. (And telling anyone passing by the same.) I can see Jose regarding the pitcher with his mouth slightly open as his bat moves lazily back and forth. I can conjure up Wright rubbing his nose in his jersey and giving his head a little shake as he regards his bat. It's easy to think of Lo Duca squinting out at the pitcher, already vaguely annoyed about something. I can visualize Delgado's smooth, deceptively placid practice swings. Give me a minute and … yep, I've got Beltran looking still and imperturbable at bat. I can smile at how Shawn Green's always all elbows and knees. I can shake my head predicting that Jose Valentin's batting helmet will fold down the top of his ear. (Doesn't that hurt?)

I can see all these little quirks that you pick up over weeks and months and years of watching the players on your team through innumerable at-bats and defensive positionings and moments collecting themselves outside the batter's box. But there's one thing I can't see with any kind of accuracy, no matter how hard I try.

I have no idea what the Mets will be wearing tonight.

Black unis? White uniforms? Pinstripes? Black caps? Black and blue hats? The all-blues?

Kind of scrambles those mental images a bit, doesn't it?

It's been a long time since the Mets added a bushel of new variations to the uniform that had been good enough, names on the back and numbers on the front and racing stripes and a tail and drop shadows and an orange button notwithstanding, to wear since 1962. I'm not against change — if anything, I err on the side of rushing it in before it's quite ready. By now I'm used to the black uniforms, added in 1998, and the white ones, introduced the year before. (Though not to that wretched black cap with the blue bill, which needs to join the ice-cream cap and the METS with a tail in the dustbin of sartorial Met history.) What I am against is the sheer randomness of the Mets' uniforms, the way they take the field wearing this one or that one or the other one without apparent rhyme or reason. (See here for a history of Mets uniforms from Ultimate Mets Database.)

Howie Rose paints the word picture ably, just as Bob Murphy did, or Gary Cohen before SNY came calling. But no matter how good Howie is, there's a moment early on in his broadcast when I'm thrown out of the whole proceedings. And that's when Howie (or Tom McCarthy) describes “the Mets wearing their [insert one of many uniforms here].” In baseball, painting the word picture is about one-third keen observation and two-thirds summoning up, through time-honored shorthand, what the listener is already picturing in his or her head. When Howie has to stop and tell me what uniform my favorite team is wearing, the whole facade teeters for a moment. My recalibrating my mental images to show the correct uniform is the like being at the theater and noticing the backdrop's just painted and you can see hands tugging on cables in the rafters, and then having to yank your attention back to the story.

It's a uniform, for Pete's sake. The very word means it's supposed to be the same. Or at least predictable. What the Mets have now is a … there isn't really a word for it. A cacophon? A cluster … oh, let's just say it's a mess is what it is.

It doesn't have to be this way. Allow me, if you will, a modest proposal. And it is truly modest — it doesn't excise uniform variations (well, except for those stupid black and blue hats) or demand things be the same as they were in 1965 or 1986. It shouldn't endanger the slightest percentage of revenue from merchandising. It merely seeks to restore a certain sanity to what should never have become so complicated in the first place.

Here they are, the proposed uniform rules for your New York Mets:

Home night games: Pinstripes and blue caps.

Home day games: White uniforms and blue caps.

Weekend night games and holiday games: Black home uniforms and black caps.

Road night games: Gray uniforms and blue caps. (Or black. Monochromatic on the road works for me. But pick one.)

Road day games and holidays: Black road uniforms and black caps.

It may not be perfect. But it restores the traditional uniforms to what I see as their rightful role. They'd once again be the norm, while allowing plenty of chances to cash in on the current mania for variations that's infected clubs with lineages far older than ours. (Those red Braves uniforms, my God.)

Exceptions would be allowed. If the team wins five in a row and the players aren't inclined to mess with a winning streak, every fan would understand. If Pedro's convinced the black unis will end a five-game skid, listen to the man. And building on this foundation would let unique days feel actually unique, instead of just like an additional throw of the equipment-manager dice. Negro League uniforms are always cool. Wearing the various agencies' caps on September 11th makes for a quietly moving tribute. Break out the '86 unis every September 17th. And why stop there? Stars-and-stripes uniforms for the Fourth of July (the Binghamton Mets did it), camo togs for Memorial Day, pink unis instead of just bats for Mother's Day — I could live with all of that, if only the rest of the year were predictable. What If? nights with the Mets wearing concept designs for the Meadowlarks, Burros, Continentals, Skyliners and what-not. Heck, have “The Natural” night with the Mets in the yellow-and-white uniforms of the New York Knights — I just made that one up. I could even hoot cheerfully at the return of the Mercury Mets, as long as the leadoff hitter isn't given a third eye.

On second thought, that last one's too much.

by Greg Prince on 12 July 2007 8:42 am Of course Rick Down had to go. Dude got a whole lot dumber once Moises Alou got hurt.

Funny how little we hear of hitting coaches when the hitters are hitting. They’re a hundred times less visible than their pitching counterparts. We don’t even notice how regularly they wear their jackets. As one of our sharpest blolleagues, JAMMQ at The Mets Are Better Than Sex, asked during a recent teamwide offensive torpor:

Why is it only pitching coaches are allowed to go out to the mound? Why aren’t hitting coaches allowed to do the same thing for batters? Since 1954, when the Supreme Court established that “separate but equal is inherently unequal,” we believe a grave injustice is still on-going in that hitting coaches and managers aren’t able to run out to the batter’s box and settle down a hitter in much the same way a pitching coach is allowed to go to the mound and settle down a rattled pitcher.

Great question. I haven’t the foggiest as to the answer.

It occurred to me sometime last summer that Down must have been doing an aces-high job given how little his name seeped into our consciousness. After all those midseasons of the air thickening with calls for the ouster of Tom Robson or Dave Engle or Don Baylor, it was both refreshing not to see fingers pointing and discouraging to realize the guy nominally responsible for a teamwide offensive bonanza wasn’t reaping substantial public credit. Mind you, I have no idea how much credit Down was legitimately due, but if everybody’s going to jump ugly on the hitting coach when ohfers abound, it seems only right to say he was The Man when the lineup was clicking.

First word Wednesday night (issued as I fell asleep from watching HBO’s anesthetic of a two-hour documentary on the Dodgers — Larry King grew up in Brooklyn you say?) indicated the job will fall to Rickey Henderson, though a later report said Henderson’s definitely en route but Howard Johnson may become hitting coach. HoJo has been talked up as David Wright’s guru while Jose Reyes’ upswings have been traced to Rickey’s tutelage (Jose apparently works well with No. 24s).

Hmmm…maybe Down was too closely identified with Ricky Ledee.

If it is Henderson — even if it’s not Henderson and he’s here to coach first — it’s remarkable to realize what a winding road (albeit via the same Minaya shortcut that keeps Julio Franco off the coaching staff and on the active roster) Rickey took to get back here. He was disgraced within the organization when he was released in May of 2000. That was one of Steve Phillips’ decisions — signed off on by Bobby Valentine — that I was in complete alignment with. On a Friday night against the Marlins, Rickey launched a ball to the base of the leftfield wall and Rickey wound up on first. For someone whose entire career was predicated on running…Rickey wasn’t. And it wasn’t the first occasion since the previous August ln which Rickey’s dance card eschewed the hustle. The next day, in a rare show of Met front office resolve, he was sent packing; he’d be the only 2000 Met, counting even cameo men like Ryan McGuire and Jim Mann, begrudged an N.L. championship ring by the general manager.

Seven years later, Rickey is far more welcome in Flushing than Steve Phillips. Who’d have figured?

The one thing everybody seems to remember ruefully from Henderson’s Met tenure was the card-playing during Game Six in Atlanta. I have to admit I didn’t get riled up about that (other than being disappointed someone would choose to hang with Bobby Bo). Though I imagine ESPN could do a nice job of dramatizing it should they ever turn the ’99 Mets into a stilted miniseries, Rickey (like Bobby) was out of the game by then. Something tells me if Rickey wasn’t Rickey but still shuffled the deck while his team was battling for its life, he’d be held up as a charming example of old school superstition. It’s the durndest thing, I tell ya. Henderson was dealing hearts while the Mets were tying the Braves. What a character! But you could also argue if Rickey wasn’t Rickey…ah, y’know what? Rickey did pretty well being Rickey. Let’s hope he can teach the good parts. He is, when all is said and documented, a card-carrying legend.

The most infamous coach-sacking in Mets history was the triple-execution of June 6, 1999 when Bob Apodaca, Randy Niemann and Tom Robson took three for the team. Tom Verducci recaptured Henderson’s priceless take on the situation and perhaps the value of hitting coaches four years later when the ageless wonder was hanging on with the Newark Bears:

Henderson saw reporters scurrying around the clubhouse and asked a teammate, “What happened?”

“They fired Robson,” was the reply.

“Robson?” Henderson said. “Who’s he?”

Rickey’s Enriched Learning Center for Gifted Children is in session…discover your desks, people. See, Rickey isn’t old school. Rickey’s a magnet school. Rickey’s what they called, when I was in third grade, open school. In Dr. Rickey’s progressive classroom, if he is indeed named head of the batting department at P.S. .268 (P.S. .252 with runners in scoring position), I doubt we’ll have trouble remembering the identity of the hitting instructor for very long.

by Greg Prince on 11 July 2007 7:25 pm Didn't love the All-Star result, but I'm always happy to see Phone Company Park. Not that we haven't seen it, but it's a call worth placing any time. Baseball has done the right thing two straight Julys, bringing its showpiece first to Pittsburgh then San Fran. For sheer attractiveness, I think those are the two most beautiful settings in the sport.

Well, those and Shea.

As you probably know, the next All-Star Game will be in New York, but on the wrong side of town. The only way I can imagine slogging through that sycophantic media tonguefest will be to have National League manager Willie Randolph guide a squad led by Reyes, Wright, Beltran, Maine and five or six more Mets to a rousing victory. The Mets and their N.L. colleagues will celebrate, but our contingent will tell you it's nothing compared to winning the World Series last fall.

Anyway…we don't get a second All-Star Game at Shea the way things stand now. We got one when we opened and we've had to stay satisfied with that. It's been reported, however, the Mets will host an ASG in 2011, more likely in 2013, at Citi Field.

I have a better idea. The Mets should host the All-Star blowout at Citi Field in whichever year MLB gives it to us. And they should host it at Shea Stadium. Game and home run contest at Citi. Celebrity softball and some sort of pitching-based skills competition at fair and symmetrical Shea.

For that to happen, you'd need both ballparks. To which I say, but of course!

This is about more than an All-Star Game, though. It's about saving a precious piece of our heritage. It's about a simple enough proposal that I've been mulling for months, one that won't happen but, honestly, maybe ought to.

Let's build Citi Field. Let's keep Shea Stadium.

Imagine that. Imagine the Mets as the only ballclub in the entire realm of baseball to claim not one but two home fields. Talk about a home field advantage!

I'm not crazy.

OK, I might be crazy but it made perfect sense to me in April when the notion first hit me where else but at Shea when I was in the upper deck with my friend Laurie. We were enjoying not just the Mets beating the Rockies but the drop-dead gorgeous view of Queens-glorious-Queens from Section 1, Row H. Damn, I said, this is just too perfect to destroy.

I believe — and my focus group (Laurie) agreed — this two-ballpark plan will satisfy any number of constituencies. It speaks to issues of heart and practicality. If executed well, CitiShea could be a revolutionary revenue-generator for club management. Since they rightly have an interest in making money, how could they not love it?

Build Citi Field to completion but keep Shea Stadium.

There. Done.

Why not? Parking? Who needs adequate parking? Seriously. The Mets are drawing, on average, 44,320 per date in 2007. Remember when it was a big deal for the Mets to draw 40,000 to a given game? When it was a good sign that the Mets could get 25,000 on a weeknight? That's not a problem anymore. Give the people a good team and they will show up in record numbers. They will countenance whatever hassles you put in front of them, including a lack of parking.

Mets fans as a people have already adapted to the lack of automotive accommodation. It's become a badge of honor for chronic drivers that they know just when to leave home, how early to arrive and where their secret route or nook and cranny nobody else knows about is. For the rest of us, throw on a couple more trains, fix the Willets Point station and it will be barely remembered that we used to have a zillion more spaces. (Besides, Ebbets Field didn't have much parking.)

The site where Shea Stadium sits is due to become a parking lot by Opening Day 2009. Can you think of anything sadder, the ballpark where you fell in love with your team not only not existing any longer but giving way to a constant reminder that it doesn't exist? Mark it all you want, it doesn't help. There's a simple, tasteful home plate diagrammed in the parking lot of U.S. Cellular Field marking where the real one stood. It says, if I recall correctly, COMISKEY PARK 1910-1990. Lines extend out from where the plate was, as if bordering an infield constructed of asphalt and eternity.

I saw this on my last visit to the South Side of Chicago and I nearly cried literally on the spot. I have to admit that though I'm not a White Sox fan I did love old Comiskey, so it's little wonder I felt that way. But I had no love for Veterans Stadium, yet a couple of weeks ago when I saw the parking lot it had become, my baseball heart ached more than I would have thought. Thirty-seven years ago Philadelphia set out to honor those who fought and died for their country by naming its new sports facility in their memory. Now that honor has been reduced to a plaque.

A plaque and a parking lot…what do you think Joni Mitchell was trying to tell us anyway?

So let's not to do that to ourselves. Let's not pave over our 1964 paradise. But let's not be dead-enders either and deprive ourselves of a potential PNC or Phone Company. Let's be flexible about this.

Let's have our Field and Shea it, too. Both, baby. Both.

Your next question may be whatever for? Why are we building this state-of-the-art blahblahtorium if we're gonna keep Ol' Leaky around?

Glad you asked. I've got a multipoint plan:

1) The Mets move their operations to Citi Field.

2) The Mets play at Citi Field 75 dates a year.

3) The Mets play at Shea Stadium six dates a year.

Of course you use Citi Field has your primary home park. You just went to the trouble of building it, you're not going to pot plants in it. But what's the one overriding complaint you've heard about Citi Field from everybody who's read the fine print? That it will have not enough seats.

All that great attendance we were touting earlier will go by the wayside as of 2009. Crowds of more than 45,000 (seated crowds of more than 42,000) will be a thing of the past. Never mind how it looks in the agate. It will look like nothing to thousands of Mets fans every day because they will have no look whatsoever inside Citi Field. The noble concept may be to promote Ebbetsy intimacy, the bottom line goal may be to juice demand, but whatever the intentions, the truth is there will be games for which each of us (who isn't a full season ticketholder) has made it into at Shea that we stand a far lesser chance of seeing at Citi.

I'm willing to accept a little “oh well, that's life” here. The newer parks I think are so neat, PNC and Phone Company, do not hold 56,000 seats. I get the idea that being (or at least feeling) closer comes with a price, and not just whatever the market will bear. Bigger seats, closer seats…fewer seats. It's not ideal. It's not at all ideal unless you're inside. Fewer of us will be on every given day.

So let's promote a little feelgood expansion, shall we? Let's keep Shea around to host six games annually, one per month. Let's open the season at Citi, a guaranteed sellout, but let's revive Opening Day II and hold it at Shea. Make a big deal out of it like the Mets did in the mid-'80s with Rodney Dangerfield. Bring in Kevin James or some other regular-bloke entertainer to do self-effacing shtick. Manufacture some more magnetic schedules. What's the harm? You just made 11,000 or so Mets fans happy who would have otherwise been put out and put off.

That's April. In May or June, you bring one of the Subway Series games back to its roots and hold it at Shea. Figure out a way to make the 56,000 seats available to 56,000 Mets fans (I know they haven't done that yet, but assign a task force). Imagine how cool it would be to face down the Yankees with two ballparks. Imagine the cred we'd have all over America. Gee, I thought the Yankees were the big deal in New York, but the Mets have TWO stadiums. They must be the balls in that town! With Yankee Stadium, even restructured the-Bronx-is-boring 1976 Yankee Stadium, out of the picture, we'll have aesthetics, critical mass and tradition working for us. Whereas they'll just have Not Really Yankee Stadium, we'll have all kinds of options.

In June (or May, depending on the Subway schedule) you hold one of your concert-type nights at Shea. Merengue Night. Irish Night with green caps and Black 47. Doesn't have to be geared to any one international theme either. Bring in a panoply of Mets-loving performers. Bring in Yo La Tengo. Bring back the Baha Men. Make it a 4 o'clock start and sell it as a doubleheader of baseball and music. The place will rock, honoring the heritage of both the Mets and the Beatles.

July? Fireworks night. You can have two. One at Citi, one at Shea. People love fireworks. I don't much care about them, but many do.

August? How about a day-night, two-ballpark doubleheader? I mean two ballparks we can stand to be in on the same day. And make it a festival. Reinstate Banner Day and turn it into a joyous parade that exits Citi Field and enters Shea Stadium to herald the night portion of our twinbill. (Separate admissions will be required — this is a dream, not a fantasy.)

Come September, save one divisional date against that year's prospective rival of rivals and make them extremely uncomfortable. Imagine jarring them from the plush clubhouses and modern amenities of Citi Field in the middle of a series and sending them back to the jungle that is Shea. If the Mets are in a race, fathom the fervor of the fans who have been locked out of Citi finally getting a shot at the Braves or Phillies or Marlins or Nats just like in the old days. “God,” you can just hear Larry Jones saying, “I thought we were done with that place. It completely threw us off our stride. It's horrible. I can't hit there once a year. That's it. I'm retiring.”

There. Six games. That wasn't so hard, was it? Maybe you charge 10% less than what you charge at Citi. Or, what the hell, charge 10% more. Think about the cachet this half-dozen will have. “The Shea Games” will be must-see. The Mets can construct a whole new six-pack to sell — the Tradition Pack. Other than the Yankees and the September rival, you can serve up any old opponent and it will be a bona fide event. What longtime Mets fan would pass up that rare opportunity to take in a game at Shea? To show a son or daughter where Jose and David got their start? To point to the precise location of where a magic ball went through a first baseman's legs and to confirm that it really happened and that it wasn't a bedtime story Daddy made up? To remember the good old days while experiencing some great new days? (We could do that just by sticking with Shea alone, but that's a whole other moot point.)

One team, two parks is both a new idea and a proven oldie/goodie. I can think of two examples. One comes from Cleveland. Remember Municipal Stadium a.k.a. Cleveland Stadium a.k.a. the Mistake by the Lake? It was built in a fit of civic pride, perhaps in anticipation of the 1932 Summer Olympics coming to America's North Coast. That didn't happen. But there was this big ol' 80,000-seat stadium just sitting and waiting. In came the Indians to attempt to fill it…most of the time. See, the Tribe had long before set up its wigwam at smaller League Park in a different part of town. So for a dozen-some years, the Indians split their time. Municipal Stadium got the big gates, some night games, all the holidays and so forth. Day games, run-of-the-mill games, other what-have-you games were at League Park.

The Indians didn't win a blessed thing while this was going on, but they did use two parks as a matter of course. It has happened.

How about a better, closer-to-home — physically and spiritually speaking — example? How about those Boys of Summer certain modern-day owners obsess over enough to build them a permanent shrine? Yes, the Brooklyn Dodgers of Fred Wilpon's youth did not play all their games at sainted Ebbets Field even when Ebbets Field was their home. In 1956 and 1957, Dem Bums played one game per N.L. opponent, seven a year, at Roosevelt Stadium in Jersey City. It was essentially a scheme by Walter O'Malley designed to get New York's attention and show hey, you wanna see us play more games west of the Hudson? You ain't seen nothin' yet.

Roosevelt Stadium was part of a shakedown which, depending on your view, either didn't work for O'Malley (because the Dodgers wound up in Los Angeles) or worked like a charm for O'Malley (because the Dodgers wound up in Los Angeles). Either way, it was one team with two stadiums. And we already know, because we're reminded constantly, that the Brooklyn Dodgers were the balls in this town.

CitiShea isn't nearly as nefarious as EbbetsVelt. It's got all the Dodger dust with none of the posturing. The Mets aren't leaving town. If anything, they'd be putting down the most solid roots you can imagine in Flushing Meadows. They'd have two homes on the same block. Now that's big love.

I should get back to the multipoint plan, because you might be wondering if we're going to keep Shea around for a grand total of six games (the Tradition Pack…can't you just hear the ads?), what about the rest of the time? That's a lot of space being taken by an edifice that isn't doing all that much and a lot of upkeep for something not generating more than six dates' worth of action.

4) The Mets open Shea Stadium's upper deck during certain home games at Citi Field.

Remember what I said earlier about the view? It really is too good a view to let go to waste. Seriously, when I sat up there in late April, warm night, beginning to stay light for a few innings, there was no better place to be. You didn't even need the game that much. But you need it a little.

So here's the next phase. On select nights when you're fairly certain the weather will hold out and you know there will be a sellout with overflow interest in what's going on next door, take advantage. Sell seats in the portions of Shea's upper deck that provide a great view of DiamondVision for, say, five bucks. Instead of having crappy seats to watch the field, you'll have awesome seats to watch the screen. You'll get all the baseball from next door plus a wonderful sense of closed-circuit community and camaraderie. (For all we know, you'll be able to peek into Citi with a good pair of binoculars.)

The key is limiting the seat sales. You don't want to put too much of a strain on Shea. If Shea could handle the strain (or had been better maintained for four-and-a-half decades), management might not have felt the need to move. So don't strain Shea. Close off everything but the upper deck and cordon off the terrible upper deck seats. That way you concentrate on making the escalators run and the bathrooms up there work. You sell a limited supply of food and drink, maybe just packaged stuff that doesn't need to be cooked (or warmed). Have staff around for emergencies and to empty the wastebaskets, but otherwise you can go with a skeleton crew.

Picture it. You want to see the Mets. You're dying to see the Mets. But Citi Field's all sold out…again. Well, let's go next door. Let's go to Shea. Let's go upstairs. We'll have a great look at the big screen and the out-of-town scoreboard (gotta keep that), we'll bring a picnic, we'll yell LET'S GO METS! It will beat sitting in a bar or at home.

5) For a handful of dates, allow fans on the field at Shea Stadium to picnic and watch the games from next door on DiamondVision.

Same principle as stated for the upper deck. You do this a few times during the summer, preferably weeks before the monthly Mets game that will take place on the Shea field. Charge ten bucks a head. Cordon off the infield, but let families enjoy the outfield (it's a city park, after all). Keep it policed, remind everybody that the Mets will be needing this grass in a couple of weeks, you don't want to ruin their chances. Otherwise, bring your own blanket, bring your own refreshments, bring your radios tuned to WFAN and enjoy a Major League game from a Major League field. Who else's fans will be able to say they can do that?

As in the upper deck scenario, you won't just be tracking a game on television. It will be like you're there because you're so close to it. You'll be a part of a like-minded crowd. The visiting team will feel like its wandered into an echo chamber.

It can be fun. It can be raucous. It should be raucous. New ballparks, with their inherent hoity-toityness, are notorious for their unintended tamp on enthusiasm. You've just moved in, it's hard to feel at home. Keeping Shea around bridges the hellraising gap. When the Citi slickers hear the noise coming back at them from Shea, they won't feel compelled to hold back either. There will be good vibrations this way and that.

6) The Diamond View level at Shea will be converted to house the long-awaited, long-needed William A. Shea New York Mets Hall of Fame and National League Museum.

No longer stuffed in a closet, the Mets' Hall of Fame comes alive. An entire level of the stadium celebrates Mets' history. The Diamond View suites each host a different permanent or rotating exhibit. The Diamond Club becomes the museum cafeteria (sandwiches and such catered by nearby restaurants, again saving the strain on Shea's delicate infrastructure). Spotlight the Mets' history where most of it occurred. Once the luxury boxes, the restaurants and the paeans to the Dodgers are erected at Citi, there won't be much room for that sort of Mets thing anyway.

Seriously though, every effort should be made to connect the various pasts and the present and the future. The two parks are so close, maybe there's a stylish bridge, an actual bridge, that could be built. Part brick, part neon or one that pays homage to the Triborough or Whitestone. Linking Citi and Shea tells everybody this is OUR history, the entire scope of it. Here's the new park that looks like somebody else's old park because that old park that belonged to somebody else laid a foundation for our team, and here's OUR old park, the one our franchise grew up in. One is a park in the traditional sense or what we think of as traditional. The other is a stadium that was OUR tradition. This is what baseball looked like in ZIP Code 11368 for 45 years. We don't have to show you pictures. It's here. Revel in it a little.

The rest of the time, give Shea back to the people. Bring in more high school ballgames, area soccer leagues. You're not going to want Citi Field to be trampled on for such lowbrow activity anyway. So keep Shea around and let it be used and loved a while longer. It's the sundry stuff that's been killing Shea. So eliminate the sundry stuff. Don't make it handle 45,000 people a night. Don't challenge the plumbing. Don't plug too many appliances in at once.

But scale it back gently. Staring into a parking lot and thinking there used to be a ballpark here…it's sad enough to know there are apartment complexes where the Polo Grounds and Ebbets Field stood. At least we don't walk by them, except perhaps in the mind's eye, when we go to Mets games. When I was at Citizens Bank, I bought a DVD heavy on Connie Mack Stadium footage. I never went to Connie Mack Stadium, it was in what was no longer a desirable neighborhood and I don't like the Phillies, but seeing the plot of land where a baseball cathedral once stood now being used for something else…that was sad, too.

Now I'm leaning on sentimentality, which isn't nearly as theoretically practical as what I've suggested, but why else would anybody float a pipe dream to preserve a place like Shea Stadium if not for sentimentality? A couple of months ago in the Times, Jeff Wilpon dismissed Shea as “a dull, dingy place”. Oh sure, now he tells us.

Funny, I don't remember anything dull or dingy about it last October.

Tell you what. Let's try the two-park plan for a year. Let's see how it works in 2009. If nobody wants anything to do with Shea in any capacity, then forget it, pull Big Blue apart and pull that SUV into that space right over there where Ron Hunt and Ken Boswell and Felix Millan and Doug Flynn and Wally Backman and Edgardo Alfonzo and Jose Valentin each flagged down ground balls in his respective day. I think it was one of the bases. Maybe. I dunno.

Park there enough and maybe you'll forget anything ever happened on this side of the Citi Field wall.

(I have another scenario in which the entirety of Shea is converted to condos — easy access to mass transit and Mets games! — but that's a fallback position.)

by Greg Prince on 11 July 2007 8:40 am Willie Mays emerges in centerfield after the briefest videoboard introduction in which he was pictured mostly in the cap and uniform he wore when he was first wowing his millions of fans several thousand miles to the east. He’s engulfed Teddy Ballgame-style by a mostly new generation of All-Stars: a few perennials, but primarily young guns. They’re kids born way the heck after 1973, after Willie has said goodbye to America. But they know their baseball.

Maybe the 2007 National League and American League All-Stars have been too cutely choreographed into their veritable group hug with the Say Hey elder, but the affection and reverence seem genuine. These are the best in today’s game and they know greatness when they are touched by it. It’s reassuring to see these fellows understand what they’re a part of — and I don’t mean the 2007 All-Star Game.

Willie’s at home in center. You’re not going to ask Willie Mays to leave his house on this occasion, thus these will be the grounds from which he’ll throw out the first pitch. Willie in centerfield…the game coming to him…nice touch.

He’s handed a ball. Willie, 76, had one of the great arms ever; just ask the 1954 American League (not World) Champion Cleveland Indians. So of course he’s waving back his catcher, a glint of genuine fire in his eyes. It’s one thing to bring the game to him. It’s another to make it unnecessarily easy on him. He doesn’t need your help. He’s no visiting dignitary. Never mind where they’ve moved the plate for the festivities. Willie’s clutching a baseball in his right hand. That, too, means Willie Mays is home.

His catcher obliges the pitcher’s request.

He backs up.

He crouches.

And he’s…

Jose Reyes?

How did starting shortstop Jose Reyes, in the cap and uniform Willie Mays wore when last wowing his millions of fans several thousand miles to the east, wind up with first-pitch catching duties? Was it just the logistics of the lineups? The N.L. and A.L. turned and snaked from the infield to center after their introductions more or less in the order they were standing. Was it planned that our Jose be on the receiving end of a throw from Willie Mays because by dint of batting leadoff for the home team he’d be trailing at the back of the queue? Was it just convenience? What, Russell Martin couldn’t emerge from tending to Jake Peavy and do a catcher’s job? Would Willie not throw to a Dodger? What about Brian McCann?

Say hey and who cares? Look at that tableau! Willie Mays and Jose Reyes! Pitcher and catcher — unlikely positions, but we’ll take them.

Willie rocks and deals. A strike! (Who’d argue?) Then, as all of All-Stardom serves as parted Red Sea, the two approach each other. What happens next? Does Professor Reyes untuck his pinstripes and engage Mr. Mays in a trademark celebratory cha-cha? Does Willie just keep walking as Willie has been known to do? Willie has just thrown the first pitch at 24 Willie Mays Plaza. He can do what he wants.

Willie Mays wants to greet Jose Reyes.

They clasp hands soul-shake style. They clasp like brothers, like members of a very select fraternity of ballplayers. Thrill Epsilon Wow. You’re initiated on the basepaths, at the plate, all over the field. You don’t get in by being merely great. You have to be incredible.

The moment between Willie Mays and Jose Reyes is a laying on of mitts. It’s a passing of the torch from the one New York National Leaguer you could never take your eyes off to the next. Willie Mays may be godfather to somebody else here tonight, but it’s Jose Reyes, 24 and still figuring things out, who plays like his spiritual heir.

A lot of time, too much time, has flown between the twilight of Mays and the age of Reyes for us to call this a direct flight. Three decades moseyed on by after Willie exited and before Jose entered. It was an eventful enough interregnum for our New York Mets, but it was lacking something. Verve…panache…joie de ball. There were some fine and extremely dandy everyday players in our particular midst who preoccupied us from 1973 to 2003, but none to whose career we New York (N.L.) types can lay some or total claim who generated, just by showing up, as much pure and spontaneous excitement as Willie Mays did or Jose Reyes does. The game we love is just better when there’s a cap departing Willie’s head or a base greeting Jose’s arrival. We didn’t get more than a taste of the former on our terms. But we’re making up for it with loads of the latter.

Now they’re together, in centerfield a continent away, cementing what feels like — through the television and a lifetime of rooting for the only team that has sent Jose Reyes and Willie Mays to an All-Star Game — an intensely sacred bond.

Theirs. Ours.

These members of the highly exclusive Order of Swift Feet, Cannon Arm, Quick Bat, Awesome Instincts and Genius for the Game unclasp hands. The Charisma Summit is ending almost as soon as it started. But before it concludes business for good, Willie knows exactly what to do.

He signs the ball for Jose Reyes.

A sport, recognizing its greatest living practitioner, is savoring him. A city, one that eventually smartened up about adopting a favorite son, is embracing him. Yet Willie Mays puts all that on hold to sign a baseball for Jose Reyes.

Jose Reyes accepts what Willie Mays has given him. “I’ll save that ball all my life,” he says.

I, too, will keep what Willie Mays and Jose Reyes just gave me. You don’t have to travel to San Francisco in July to know what a chill feels like.

by Greg Prince on 10 July 2007 9:45 pm

| Bringing the Mets good luck — and the official FAFIF shirt a good look — is Della Ziegler, a.k.a. Mrs. Lonestar Mets, lovely wife of our Texas compadre in blogging Dan. Della and Dan attended last Saturday’s Mets-‘Stros marathon at Minute Maid Park, the one that went on and on and on and on until we beat the Astros at the break of dawn. Carlos made his catch and the Lonestars went home happy (only to return several hours later for the extraordinarily less satisfying Sunday loss, but as we all know now, the Mets don’t really get cooking until the 14th on any given night).This makes eight different states and the District of Columbia where Faith and Fear’s shirt has been photographed. Rumor has it a whole other continent is about to come into play. Stay tuned… |

|

|

by Greg Prince on 10 July 2007 9:12 am So there they are, your 2007 Major League Baseball All-Stars, gallivanting about in black and orange, orange and black. Every batting practice, home run contest and celebrity softball participant is resplendent in Giant colors. Gary Carter even managed to assimilate in a cap that says SF, for the team with which he’s so closely identified.

The San Francisco Giants are your gracious hosts for the 2007 All-Star Game. They celebrate themselves as well as the game this week. Well, they celebrate the part of themselves they can lay their hands on. They celebrate Bonds. They celebrate McCovey. They celebrate Mays.

I’ll be shocked if anybody in San Francisco utters these two Giant words: Mel Ott.

Who?

Sounds vaguely familiar…

I think I heard his name mentioned the last time somebody hit his 500somethingth home run.

Oh, I know!

And with that, the slugger passes Eddie Murray. Next up on the list: Mel Ott at 511.

Mel Ott hit 511 home runs.

Repeat: Mel Ott hit 511 home runs. Long before anybody had ever heard of the clear or the cream, long before anybody expanded and depleted pitching staffs, long before television became a way of life. Mel Ott hit 511 home runs back when hitting 511 home runs was an almost unmatched feat and without anybody setting a VCR to record a single one of them. But he hit ’em. He hit ’em and hit a load of ’em right around here.

And yet, have you, especially if you’re younger than 50, ever heard of Mel Ott beyond the most cursory of statistical mentions? Do you know who this man was and what he accomplished and where he accomplished it?

I’m guessing no.

I’m not blaming you. You can only seek out so much baseball. The rest is to be absorbed by osmosis, and for osmosis to occur, the baseball’s got to be out there somewhere. Mel Ott’s substantial slice of it isn’t anymore. Mel Ott has been lost to the mists of time. Mel Ott may be the greatest ballplayer to play in the greatest city in the world to have all but vanished from public consciousness.

It’s tough to remain an active immortal when your team has left you behind. That, of course, is what the New York Giants did to Mel Ott the second they became the San Francisco Giants. They left behind John McGraw and Christy Mathewson and Carl Hubbell and Bill Terry and hundreds of others, too. A few have managed to have the pilot lights on legends relit in recent years. Ott, though, has fallen through the cracks and pretty much straight down the memory hole, he and every one of his 511 home runs.

Which were huge in their time. Mel Ott was a star. He was an All-Star rightfielder/third baseman for a dozen consecutive years, from 1934 to 1945. He was the face of the New York National League franchise for two decades, beginning with when he was a teenager. Between Mathewson and Mays, he was, even at 5 feet 9 inches, the Giant among Giants.

Ott’s entire 22-season career has essentially been reduced to a rest stop on the home run highway. He’s where boppers collect themselves ever so briefly before preparing to pass Eddie Matthews and Ernie Banks just one dinger up the pike. Then it’s off to McCovey and Ted Williams at 521 and so on.

Mel Ott gets left in the dust. He’s a marker. Merely the signpost up ahead when he deserves to be an entire road unto himself — or at least have one in New York bear his name. Such an action is not unprecedented and the honor would surely be appropriate.

You may still refer to the West Side Highway in Manhattan as the West Side Highway (or the “bleeping West Side Highway” at rush hour), but a good chunk of it is officially the Joe DiMaggio Highway since 1999. A hardy band of fans of those departed New York Giants, the team that was identified with Manhattan for decades every bit as much as the Clipper’s club was tied to the Bronx, has petitioned two mayors and various municipal muckety-mucks to name at least part of Harlem River Drive after Mel Ott. (The Ottway has a nice ring, no?) It would be geographically spot on, given that it winds right past where its namesake player made his living and made his fans very, very happy.

DiMaggio, I’ll grant you, cast a wider PR net after his retirement, but I’ve got news for you. Before the Yankee Clipper clocked a single base hit, Ott outed 242 balls for home runs. The 511 he hit, that total passed so often in the injection era? It’s still 19th-most all time. A decade ago, it was 14th-most. And when Mel Ott retired on July 11, 1947, exactly 60 years ago tomorrow, it was the third-highest home run total in baseball history, trailing only Babe Ruth’s 714 and Jimmie Foxx’s 534. Until 1966, Ott’s 511 was the N.L. standard. The man who eventually topped him was Willie Mays, six seasons a New York Giant himself and the only fellow to be mentioned in a serious discussion of greatest everyday New York Giant ever.

Willie was Willie, but San Francisco unfortunately beckoned for the balance of his prime. Bill Terry compiled a lifetime .341 average, but little of the power and, at best, a fraction of the affection Ott did. Mel Ott, beyond his staggering numbers (notably 1,860 RBI, eleventh-most all-time) was beloved in ways that defy our modern, cynical perceptions of professional athletes.

It wasn’t for nothing that Time placed him on its cover in the twilight of his career, pronouncing him “Everybody’s Ballplayer.” It wasn’t a coincidence that when Lou Gehrig acknowledged the Giants paying him consideration in his darkest hour (“when the New York Giants, a team you would give your right arm to beat, and vice-versa, sends you a gift — that’s something”), that those were Ott’s Giants. It wasn’t a fluke that a nationwide poll of war bonds buyers in 1944 identified him as the most popular sports hero of all-time even after batting .234. And it’s no accident that the most famous and famously mangled quote in baseball, Leo Durocher’s “nice guys finish last,” started out as a tribute to the nicest guy of them all:

“Do you know a nicer guy than Mel Ott?”

Durocher offered his lefthanded praise to the Giants’ skipper (in his fifth season of seven as player-manager, when the Giants, in fact, were eighth of eight in the league) in the service of promoting Durocher, but it wasn’t an inaccurate assessment of Ott’s persona as it was widely viewed through his 22 seasons as a player.

• Is it any wonder that the National League officially honors its annual home run champion with the Mel Ott Award to this day?

• Is it any wonder that the evening after Ottie banged his 500th homer, renowned saloonkeeper Toots Shor abandoned entertaining the Nobel Prize winner who happened to be in his establishment, Sir Alexander Fleming, to welcome Master Melvin to the premises with a perfectly reasonable, “Excuse me, Alex, I’ve got to greet someone who’s really important”?

• Is it any wonder that after he was dismissed as manager by the Giants in 1948, they didn’t pretend he never existed but instead made sure to retire his number 4 the very next year? (It remains retired; thanks for that much, San Francisco.)

So he was a sweetheart and he hit a lot of home runs. Is there more to Mel Ott than that?

How about this: Mel Ott is the Home Run King of New York.

Aw, come on, you may be thinking. Everybody knows that’s Babe Ruth’s gig; we’ve seen the pictures with the Babe wearing the crown. Yes, of course, Ruth set the records for most home runs in a season and in a career, but not even the Bambino homered as much in New York City as Mel Ott did.

As documented in Stew Thornley’s essential Land of the Giants: New York’s Polo Grounds, Babe Ruth hit 299 regular-season home runs between the PG (Yankee home Ruth’s first three seasons in town) and Yankee Stadium. That, though, is a full 24 shy of Ott’s Coogan’s Bluff total of 323 — which doesn’t even take into account his frequent visits to Brooklyn and the 25 homers he hit out of Ebbets Field.

Granted, the Polo Grounds was as strangely shaped then as Barry Bonds’ head is now. Lefty Ott and his singular stance — lifting his right foot “completely off the ground and slightly crook[ing] his knee more as if he were pitching a ball than about to hit one,” Roger Angell wrote — surely took advantage of the 257-foot rightfield foul pole. If that’s how she played, that’s how she played. The wondrously weird dimensions of the Polo Grounds (including 483 feet to center) were as nutty for every Giant and every opponent as they were for Ott. If Yankee Stadium was The House That Ruth Built, the Polo Grounds turned out to be the crib where Mel Ott was born to deposit line-drives over a short fence.

Did somebody say “crib”? It wasn’t long after he first drew breath that he was swinging there. Mel Ott made his Major League debut in 1926 at the preposterous age of 17 (no minor leagues for this minor), thus earning that endearing and enduring nickname, Master Melvin. In Yogiesque terms, he was mighty young for an awfully long time. There was also something oxymoronic about his appearance, all 5′-9″, 170 pounds of it: A boy that green, a frame that slight, a signature right leg lift that unorthodox…yet home runs that plentiful. It’s as fitting and can be that the definitive book on him, by historian Fred Stein, is titled Mel Ott: The Little Giant of Baseball.

It’s sadly apropos that Ott got such an early start seeing as how his life ended too soon, at age 49, after a gruesome car accident in his native Louisiana. It’s unfortunate in a less tangible way that his death in 1958 accelerated the forgetting process that erases far too many figures from the collective memory.

Mel Ott is gone nearly 50 years. He fleetingly re-emerges in the collective baseball consciousness from time to time.

• Like when Ken Griffey became the most recent player to pound a 511th homer and when Frank Thomas or Alex Rodriguez becomes the next to reach that plateau.

• Like when TV Land airs that episode of M*A*S*H in which Colonel Potter, irked by Major Winchester’s assertion that operatic tenor Enrico Caruso is a giant, makes the same reference any American would have thought of as late as the Korean War:

“If I want a Giant, I’ll send for Mel Ott!”

• Like when 37-Across in the Times crossword contains the clue “Giant Mel” and there are three squares to fill.

• Like when the United States Postal Service issued four stamps last July to honor four Baseball Hall of Famers. Three of them — Mickey Mantle (61*), Roy Campanella (It’s Good To Be Alive) and Hank Greenberg (The Life And Times Of…) — were immortalized in film. The fourth is Mel Ott.

He’s a hint. He’s a sitcom rejoinder. He’s a line in The Baseball Encyclopedia to be hopped, skipped and jumped by the next slugger who doesn’t test positive for something a 5′-9″ legend in his time never needed.

Now he’s a stamp. Anything that affixes him in memory is a good thing, I suppose. Seems like he should be more, though. He was Mel Ott, for goodness sake. When I was in third grade, I found four ancient biographies of long-retired ballplayers in the school library: Ruth, Cobb, Gehrig, Ott. Ott was the only one I hadn’t really heard of before. Those other guys have stamps and movies to burnish their accomplishments, and a seemingly perpetual place in the National Pastime’s mythology. I’d be shocked if a single third-grader in America is reading about Mel Ott this term or next, no matter how often the post office cancelled his image in the past year.

Mel Ott played the 2,730th and final game of his Hall of Fame career 60 years ago Wednesday. He made his retirement as a player official at the end of 1947, returning as manager for ’48 — by then they were routinely referred to as the Ottmen — only to be replaced midway through the campaign by the far more fiery Durocher. Leo the Lip would do great things as Giant general, but it is no hyperbole to say an era ended with that momentous change of command. Mel Ott played for John McGraw. McGraw defined his franchise and his circuit in New York for more than a quarter-century. There was an unbroken line there that ran from McGraw’s hiring in 1902 and Ott’s dismissal in 1948. There’s never been a stronger baseball tradition in New York, not in the sense that generations and families inform tradition.

Mel Ott was National League baseball in New York in the way that…I don’t know that there’s an obviously analogous Met. I’d like to say Tom Seaver, but we know evil forces sent him on a wayward path far from home. (Ott, by the way, was a Tigers broadcaster when the Giants played their final home game in Harlem in 1957 and missed its farewell; imagine Seaver not being on hand at Shea next September.) Maybe if Buddy Harrelson had become a beloved and tenured Met skipper, maybe him, but we’re also talking about a playing career that is nearly unparalleled in all big league annals. No, there is no Met (yet) who quite measures up in Ottman terms. Not too many teams have had anybody like that, but it is worth mentioning the Mets in all of this.

Our New York Mets play under the same NY as Mel Ott did. Our New York Mets started life in the same Polo Grounds where Ott, as Angell put it, “consistently, quietly and always reliably” established his indelible statistical imprint of most National League home runs, runs batted in, runs scored, total bases, bases on balls and games played as of his retirement. Our New York Mets’ reason-for-being is born of two paternities once removed — one about to be commemorated for the umpteenth time while being permanently set in brick and another that’s amazingly obscure considering its rich history — a lore known far and wide by the middle of the 20th century, disappeared from view by that same century’s end.

Mel Ott doesn’t require a rotunda in Queens. But I thought it would be nice if somebody brought up his name and delved a little into what it represents within our New York National League genetic code. It’s something not nearly enough people in these parts do anymore.

You can read Fred Stein’s profile of Mel Ott at SABR’s Baseball Biography Project. It is adapted from an excellent book, available here.

by Jason Fry on 9 July 2007 4:54 pm Fifteen teams are sending just one representative to San Francisco for the All-Star Game: the Braves (Brian McCann), Marlins (Miguel Cabrera), Nationals (Dmitri Young), Cardinals (Albert Pujols), Pirates (Freddy Sanchez), Reds (Ken Griffey Jr.), Giants (Barry Bonds), Rockies (Matt Holliday), Blue Jays (Alex Rios), Orioles (Brian Roberts), Devil Rays (Carl Crawford), Royals (Gil Meche), White Sox (Bobby Jenks), A's (Dan Haren) and Rangers (Michael Young).

Some of those guys are superstars (Pujols, Griffey, Bonds), while others are rising stars (Cabrera, McCann, Holliday, Crawford). But some of the others fairly shout obligation. Do Michael Young's underwhelming numbers shout “midsummer classic” to you? Gil Meche has five wins — should he go to San Francisco for that? Does a punchless singles hitter like Freddy Sanchez really deserve an All-Star berth?

Yes, yes and yes. And I won't hear otherwise.

Why? Because of John Stearns. And Pat Zachry. And Joel Youngblood. And Lee Mazzilli.

I remember those players from my first plunge into Met fandom, which started when I was seven and was as all-encompassing and life-changing as anything you love to distraction when you're seven. Except having traded Tom Seaver away, the Mets were terrible. Embarrassingly terrible. Avert-your-eyes, bag-over-your-head terrible. A few thousand at Shea terrible. And growing up on the North Shore of Long Island as a Met fan, not surprisingly, was terrible too.

In the late 1970s, I made many, many bus rides to and from school and many, many circuits around the cul-de-sac where the kids of my neighborhood rode bikes. And from March through October, many of those bus rides and bike circuits were spent taking heaping portions of abuse for being a diehard fan of an irrelevant team. Most of my neighbors were Yankee fans, an allegiance they'd either come by honestly (if being soulless and evil can ever be arrived at honestly) or taken up because it was the easy thing to do. Up and down Miller Place I'd go, hearing the catcalls of sneering, braying junior Yankee fans. Mets suck. The Mets are so gay. How are the gay sucky Mets doing this year? Back and forth to school I'd go on the bus, tormented by the Steinbrenner Youth singing the version of “Meet the Mets” that was better known in our town than the real thing.

Beat the Mets, beat the Mets

Step right up and beat the Mets

Hit your kiddies with a bat

Guaranteed to want your money back

Because the Mets are really stinking this year

Fourteen behind and still acting queer

From Expos to Giants, everybody's comin' round

To beat the M-E-T-S Mets of New York town!

I wasn't stupid. I knew the Yankees spent money and had a good chance of winning their division every year. I knew the Mets were embarrassingly cheap and had no chance. I knew they and I would be disrespected for it from spring training to the fall, that nobody wanted Met cards, that Herman's Sporting Goods barely bothered stocking Mets caps, that everybody in Little League wanted to be on the Yankees and groaned when they had to be on the Mets. (I was a Dodger.) This was my lot in life, and I gloomily accepted it while reading about 1969 and 1973 and dreaming about years yet to come, when things would somehow be different.

I had one thing, once the hope of spring training faded and the reality of another dismal regular season set in: the All-Star Game. No matter how good the Yankees were, or how bad the Mets were, a Met would go to the All-Star Game. Unfortunately, when I was a kid the Met who usually went was John Stearns. Stearns would be the backup catcher, the just-in-case guy who never got to play. The Bad Dude went in '77 (Tom Seaver wore the colors of the Reds), '79 and '80. Between those three All-Star appearances he got one at-bat. And so it was for the Mets: Pat Zachry got tapped in '78 and didn't pitch. Joel Youngblood went in '81, after the strike, and went 0 for 1.

But that was OK. Because what mattered to me was all the silly stuff I now usually miss. Just hearing “from the New York Mets” and seeing John Stearns come out of the dugout to the tepid applause of some far-off place was enough. Why, he'd slap hands with Pete Rose and Johnny Bench and Dave Parker, then look up at the crowd and tug on the bill of his cap. He was a New York Met All-Star, one of the elect, on national TV like all the rest of them. It didn't matter that he was usually alone in orange and blue, or that Sparky Anderson or Tom Lasorda wouldn't find a place for him. By lining up with the rest of the National League's best he was proof that we mattered after all, no matter what the kids on Miller Place said.

And then there was 1979. Stearns went to the Kingdome and didn't play. But that year we somehow had two All-Stars. Lee Mazzilli, he of the basket catches and Italian good looks and Brooklyn roots, went too. And Maz did get to play. He led off the top of the eighth, pinch-hitting for Gary Matthews, whom the Mets had famously tried to recruit as a free agent by sending him a lowball offer via telegram. Facing Jim Kern, Maz cracked a home run to tie the game at 6-6. Then, in the top of the ninth, Mazzilli batted again. With the bases loaded. And on the mound was Ron Guidry … of the New York Yankees.

Ron Guidry. Louisiana Lightning. The year before, he'd won 25 games and the Cy Young Award. And for all that he seemed overshadowed by the Yankees' other stars, by Reggie and Thurman and Nettles and Randolph and Piniella and Gossage. We didn't face the Yankees, unless you counted the farcical Mayor's Trophy Game, which nobody did. But now we were. Tie game, bases loaded, the entire nation watching. It didn't count, but it sure as heck mattered.

And Maz, the New York Met, coaxed ball four from Guidry! He walked! In came what would prove to be the decisive run in a National League victory. I lay awake that night thinking happily of how tomorrow I'd get to see if the Yankee fans wanted to talk about how Ron Guidry had lost the All-Star Game to the young star of the Mets. I'd get to argue, perfectly plausibly, that Mazzilli should have been the MVP instead of Dave Parker. It wasn't a home run or a liner up the gap or even a clean single, but it had done the job. Guidry had thrown a complete game two days earlier and tired himself out warming up several times, but that was excuse-making. It wasn't winning the World Series, but I knew we weren't going to do that. Maz had beaten Guidry, and that was enough.

And so every time I hear that it's an anachronism for every team to be represented in the All-Star Game, I remember those summers and that night, and the only day I ever got to strut through the halls of my elementary school because I was a fan of the New York Mets. And I think, for once utterly without irony, “Won't someone please think of the children?”

There are young fans of the Nationals, Pirates, Royals, Orioles, Devil Rays and other downtrodden clubs who'll stay up to watch the All-Star Game tomorrow night. They're fans every bit as rabid as me and Greg and all of you reading. They pass the time memorizing stats and collecting cards and asking for replica jerseys for their birthdays. And mostly they spend their time dreaming — fantasizing about an impossible time when their love will be requited and their loyalty repaid. When their fandom won't hurt. When they won't feel their shoulders slump at the first brush of disdain and pity from those who root for winners.

Does John Maine deserve to go to the All-Star Game? Undoubtedly. Would I trade Freddy Sanchez's spot to right this wrong? No way. Because I have no doubt that a generation ago there were players who deserved an All-Star berth more than Stearns or Zachry or Youngblood or Mazzilli, and that the Sporting News or Baseball Digest or Dick Young said so. Not getting to see John Stearns tip his cap might have derailed me from the tough business of fandom, and I know there's a kid in Pittsburgh who feels the same way today. He reads about the We Are Family Pirates and wonders how the heck Sid Bream could have been safe and mourns how Barry Bonds got away. He daydreams about Jason Bay hitting the home run that secures the win for Ian Snell in Game 7 of some future World Series. And he's waiting — far too excited for his own good — for the Giants' PA announcer to introduce Freddy Sanchez, to see him in the Pirates' colors, to revel in the fact that for a few seconds he'll be standing by his lonesome at the center of the baseball world. Take that little ritual away, and you just might steal that moment that keeps him faithful amid all the middle-of-the-night fears that the game is rigged and his hopes are for nothing.

I needed that moment, and I got it. He deserves no less.

by Greg Prince on 8 July 2007 10:58 pm 1) Keith Hernandez has highly selective recall of his own career. Last night he invoked the infamous Terry Pendleton game, framing it as a crushing loss (no argument), coming as it did in the second game of a series (it was the first), after a game the Mets beat the Cardinals (again, a nonexistent game) and before the finale, which the Mets came back and won (the Mets were blown out of the game right after the Pendleton game but won the day after that). Today he placed himself in the 1988 All-Star Game (it was the '86 game) at the Astrodome (the '88 game was in Riverfront; '86 was indeed in Houston). Dates and places aren't everybody's forte, I understand, but Keith had a hammy problem in '88 he's referenced several times before and even if the years do tend to run together after a while, 1986 was, y'know, 1986. I guess the important thing is that Keith's career was, in fact, Keith's career and the rest of us can file away the particulars.

2) Scott Schoeneweis pitched the seventh and eighth. David Newhan remained in left. Shawn Green continued to patrol right. It took 87 games, but finally my mini-vigil paid off as the first three Jewish Mets to be on the same Mets team were in the same Mets game in the same Mets inning. This would be a greater source of pride if a) Schoeneweis, Newhan and Green had led a remarkable Met comeback; b) Schoeneweis and Newhan weren't Schoeneweis and Newhan; and c) I just came off the boat at Ellis Island 80 years ago and had to convince mama and papa that it was all right to take time from studying the Talmud to throw a ball around. It's not really that big a deal to me, but with only nine Mets Jewish out of 814 to date, I tend to notice these things.

3) Sandy Alomar, Jr. became the 814th Met. Nice gesture to give him a start before he's either dispatched to New Orleans/retirement or, in that way things happen with this team and 41-year-old reserves, gets 200 at-bats in the second half. Alomar was kept at the expense of Ricky Ledee, who was designated for assignment even after his clutch leftfield defense in the seventeenth inning made Saturday night his best game as a Met. All of Ricky Ledee's other games as a Met are tied for second.

4) Sandy Alomar, Jr. also automatically became the most likable Alomar brother to ever play for the Mets.

5) The last player to debut as a Met before today was Ben Johnson. His birthday is June 18. Sandy Alomar, Jr.'s birthday is June 18. Alomar is 15 years older than Johnson, yet Sandy's the one who goes by “junior”.

6) We promote the 41-year-old while the 26-year-old stays at Triple-A. But nobody ever said anything about the Mets and a youth movement.

7) Aaron Sele went two solid weeks without pitching between June 19 and July 3. He's now pitched in four of the past six games. He seems to pitch better when he's used a lot than when he's not used at all. When he's not used at all, he does absolutely nothing. (Of course that's the case for most of us.)

8) I was delighted when Saturday night's game reached a seventeenth inning because it meant Gary Cohen would reference the Mets' last seventeen-inning game, a 1-0 win over the Cardinals at Shea at the end of 1993. The winning pitcher for the Mets that night was Kenny Greer, a one-game wonder whom I gently jibed in this space in April 2005 for his most fleeting Mets tenure. Well, the Internet being the Internet, Kenny Greer just got around to weighing in a few weeks ago on why he got to enjoy only one game in blue and orange. Read the exchange here. Always nice to hear from Mets, especially the fleeting kind.

9) Imagine Willie had thrown down the gauntlet to Reyes about not running to first (remember that anymore?) by not only benching him for one inning Friday but by announcing that to learn his lesson there's no way he's playing Saturday. And then Saturday goes 17 innings and Willie either sticks to his guns and/or throws out the baby with the bathwater by not playing him, thus risking losing OR Willie adapts to the situation and/or gives in too easily by playing him, thus risking severe criticism in some quarters. Either way, good for Jose for owning up to his momentary lapse of hustle. He didn't really deserve the example-making business, but his actions did.

10) Jose Reyes ran his ass off all day Sunday, but ran it off wisely. He would have been thrown out in the first had he challenged Hunter Pence. But if he had made it and the Mets took an early lead, would it have altered Roy Oswalt's approach the rest of the day? Would have Dave Williams, lead in hand, calmed down and not thrown breaking pitches that didn't do as they were commanded? Those are technically unanswerable questions. But the answer to both is no. Some games, unless it's 1988…I mean 1986, you're just going to lose. This was one of them. After an epic triumph crowned by a once-in-a-lifetime catch Saturday night — and an emergency starter rolling the dice this afternoon in advance of three days off with four (oughta be five) first-place Met All-Stars tipping their caps in San Francisco, you just have to look past it and find other things to notice.

But we don't take off. Stay with Faith and Fear to feed your baseball reading habit throughout the break. Before you know it, it will be Thursday night and you won't feel the least bit at a loss.

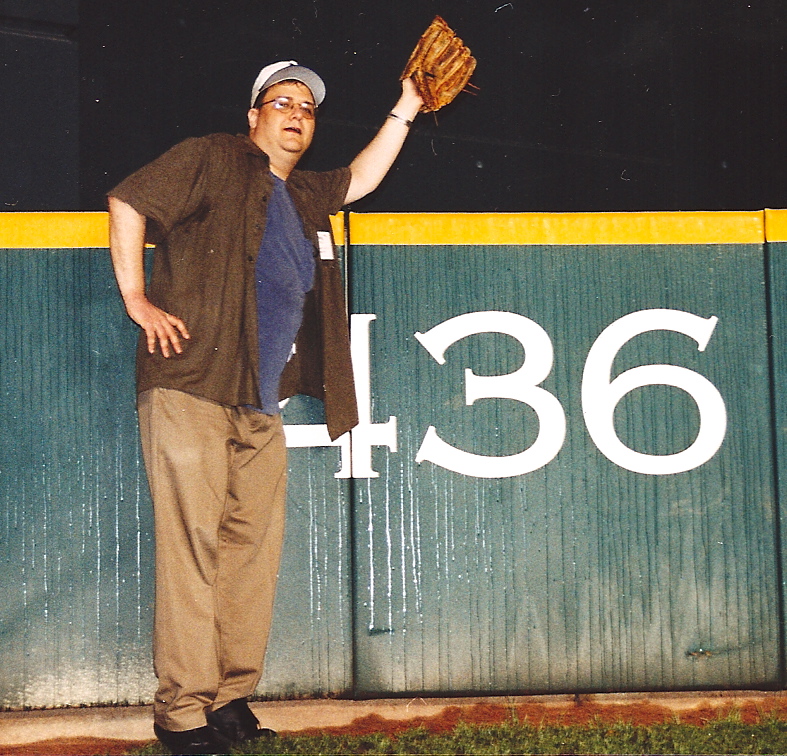

by Greg Prince on 8 July 2007 9:41 pm

I know Tal’s Hill is a silly place because I’ve been up on top of it. On September 21, 2003, in another phase of my professional life, I had occasion to wander Minute Maid Park. Natch, I headed 436 feet from home plate, straight out to center and climbed right up that hill.

It is high.

It is far.

It is stupid.

It’s maybe not as bad as my decision to pose — the one and only chance I’d ever have to be out there — with my throwing hand on my hip, but I don’t recommend it (or me) being allowed within the field of play.

Kudos for Carlos once more on conquering Tal’s Hill and tracking down Luke Scott’s otherwise gamewinning fly ball. I repeat: It was quite a feat.

|

|