The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 25 May 2022 2:03 am Once upon a time the Mets were down six runs in the seventh and with my eyes on bedtime I composed a minor recap I knew wasn’t a classic but thought did its duty well enough, particularly grading on the curve for West Coast night-owl duty. It was called “Ten Commandments for a West Coast Loss,” and it was mildly melancholy and warmly philosophical and other things you can probably guess.

And then all hell broke loose and the backspace key and I spent some quality time together.

In the eighth the Mets scored seven runs on eight singles and a triple, sending 12 men to the plate yet somehow only seeing 38 pitches. They didn’t need to work deep counts because slapstick reliably ensued — fielding miscues, balls sneaking through holes and pretty much any other form of mayhem one might imagine. When the dust settled some time later — 40 minutes? a week? — that 8-2 deficit had become an 11-8 lead, Stephen Nogosek was in line for his first career win after doing yeoman work in a seemingly lost cause, and the entire dugout was exchanged dazed grins.

Ah, but innings feature two halves. Drew Smith retired the first two Giants and it looked like San Francisco would slink off to think about what they’d collectively done, but then Smith allowed a single and a walk and Joc Pederson hit his third home run of the game, a cruise missile that came down in McCovey Cove. The Giants settled for sending nine guys to the plate, collecting four singles and that homer on 36 pitches, and the game was tied.

So of course Dom Smith tripled to lead off the ninth and of course he scored and somewhere in there I told my kid, “Pederson is totally coming to the plate as the potential last out.”

And of course Edwin Diaz came out and looked shaky and got a double play and walked a guy and allowed a single and holy cats there was Pederson again, with a muse singing of his rage. Would he hit a fourth home run? No, but a bolt of a single up the middle was enough to tie the game (and give Pederson an eighth RBI) and before anyone could get done being mad at Diaz Brandon Crawford had spanked a single to left and there was going to be a play at the plate on Darin Ruf, recently seen caught in the netting like a crew member doing pre-viz for The Hobbit, and I allowed myself a brief bump of hope before realizing that the throw was coming in a half-second too late, which was correct and the Mets had lost.

I mean, that was madness. It was bonkers. You could have had both teams play in zero gravity and do Whip-Its before each pitch and it wouldn’t have been much nuttier. And somehow these two teams will be expected to play tomorrow, instead of sleeping for three days and then starting therapy.

Yes, tomorrow. Which, for those of you who aren’t lunatics, means today. Late-afternoon matinee New York time, Thomas Szapucki reporting for circus duty. As I now don’t need to tell you, anything could happen and probably will.

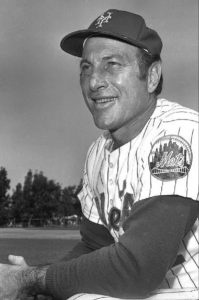

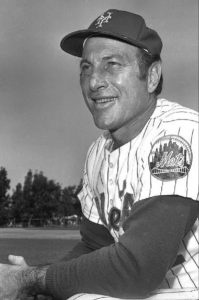

by Greg Prince on 24 May 2022 2:41 pm Joe Pignatano was the bullpen coach. He was the bullpen coach when I got here. He was the bullpen coach forever. I’m using past tense only on a technicality. Forever is a mighty long time.

Piggy, as he was known also forever, has died at 92. The ballpark in whose bullpen he famously cultivated tomatoes preceded him in death, but like Joe, Shea is eternal. Picture an affable chaperone keeping loose tabs on a clowder of purring arms — firemen, long men, swingmen, journeymen, screwballers, forkballers, young fastballers seeking the zone, old junkballers fooling the years — and you see Joe Pignatano. Dad’s in the dugout. He can’t be everywhere. “Hey, Piggy,” he asks his next door neighbor, porch to porch. “Do me a favor and watch the kids while I’m working.”

Piggy, preparing for another season. Sure thing, Gil. And Yogi. And Roy McMillan, Joe Frazier and Joe Torre. Piggy was on the staff of every Met manager from 1968 through 1981. He tended the bullpen’s vegetation and he raised relief pitchers. His garden proved plentiful.

Joe Pignatano, in case you hadn’t heard while he wore a Mets uniform, came out of Brooklyn. Of course he did. “He was a Brooklyn Italian,” his son told ESPN’s Elizabeth Merrill not long ago. “You give them a patch of dirt and they plant tomatoes.” Naturally enough, Piggy sprouted as a Brooklyn Dodger. He tagged along to Los Angeles when the Bums decided they needed to be glitzier and ritzier. The backup catcher to Johnny Roseboro stayed tight with certified Boy of Summer and future Hall of Famer Gil Hodges. The last miles of their active-player journeys crossed paths on the 1962 Mets — Piggy’s final batted ball resulted in a triple play in his team’s final loss among many — and joined forces anew in Washington mid-decade. Hodges managed the Senators. Pignatano became his trusted aide. Like fellow lieutenants Rube Walker and Eddie Yost, they followed the manager home to New York. With Gil, they grew a champion.

On April 2, 1972, as Spring Training ground to a striking halt, Gil golfed with his trusted coaches. Then he fell, never to rise. Pignatano was with him to his dying breath. Then, once there was a season, he stayed at Shea, assisting Yogi Berra as he would assist the men who succeeded Gil’s successor. Eventually Piggy took on first base coaching duties, but that, like the past tense, gets filed under technicalities. He was…is always our guy in the bullpen, always one of Gil’s guys, always as warm and funny like everybody says, always around to relive 1969 — and a Mets fan always finds time to relive 1969.

Go ahead. Pick up the dugout phone. Call down to the pen. Piggy will step around the vines, answer promptly and relay the proper instructions to the right lefty and the appropriate righty. The man knows his crops.

by Jason Fry on 24 May 2022 1:57 am What was going through Darin Ruf‘s mind as he lay on or perhaps in the netting in San Francisco while the ball he’d been pursuing bounced around somewhere nearby in an entire-world sense but entirely too far away in a make-a-baseball-play sense while a less-than-ideal quantity of Mets hustled around the bases?

Perhaps he was thinking that it might be a long night.

Or maybe he wasn’t thinking anything like that. Yes, two Mets scored on the play, but only two because the ball that had so rudely eluded Ruf did him a slight favor and hopped into the stands. There were two outs, it was only 2-2 and David Peterson hadn’t looked invulnerable out there, surrendering a home run to Brandon Crawford. And the Mets hadn’t so much pounded Alex Cobb as they had pecked at him with infield hits and little dunkers. And hey, slapstick is an occupational hazard when you’re a first baseman pressed into service in left field because a whole roster worth of outfielders are on the IL.

Maybe Darin Ruf is an optimist. I don’t know the man.

If he is, well, that was about to be tested. The next guy up for the Mets was Pete Alonso, and Cobb’s first pitch to him was a 12-3 curveball.

I know what you’re thinking. Jace, c’mon man. I know it’s late and West Coast recaps are tough, but for God’s sake you’re thinking of a “12-6 curveball.”

You’re right! That is what I was thinking of and presumably what Cobb had in mind too. But it wasn’t what he threw. The ball hung about midway down the center of that imaginary clock face, and at about 3 p.m. it encountered Alonso’s bat and then was last seen becoming a souvenir 391 feet away. It was 5-2 Mets, and that turn of events would make even an optimistic out-of-position first baseman feel a little down.

It was 5-2 and it would get worse, as Peterson settled in and the Giants’ bullpen surrendered some more infield hits and some of the outfield variety and two that went over the fence, with one hit by Jeff McNeil threatening to land in Alameda. Eventually they had outfielder Luis Gonzalez out there on the mound, and he put up a better line than Mauricio Llovera, who got whacked around enough to deserve at least two Ls.

Not a bad birthday for Buck Showalter. Not a bad start to the series in San Francisco. But when you win by 10, there’s not much bad to be found anywhere.

by Jason Fry on 23 May 2022 2:21 am The Mets have now played the Rockies for more than a baseball generation, but games in Denver will always seem bizarre — incredible shifts in temperature, snow-outs in late May, humidors and breaking balls (or the lack thereof), and the strange neither-here-nor-thereness of the team being far from home but not quite on a West Coast trip.

But the constant through it all has been that a five-run lead feels like a two-run lead, being ahead by three feels like a tie, and being up by one or two can even somehow feel like you’re behind. That was true from the jump, when the Mets helped the Rockies open Coors Field back in April 1995: The Mets came back from a 5-1 deficit when Todd Hundley connected for a sixth-inning grand slam, lost an 8-7 lead in extra innings (with nary a free runner in sight), took the lead again, and then got walked off by Dante Bichette. So was the template established: In Denver the other shoe is always about to drop, and when it does, the lack of air makes it land heavy. Succumb to a late-afternoon baseball nap and you can easily wake up to find home plate has been worn out by foot traffic and the score has gone from hectic to insane.

Very occasionally, though, you get a different kind of ballgame, one that resembles baseball on Earth. Back in 2010 the Mets won at Coors by a 5-0 margin behind Mike Pelfrey — the only time they’d shut the Rockies out in their home park. (Turns out I had recap that day and didn’t mention the feat, though for some reason I did include a still from Being John Malkovich. If you’re curious, the Mets have been shut out once at Coors Field, back in 2001.)

Then came Sunday.

Taijuan Walker may be the rare pitcher suited for arena baseball — Rockies hitters spent the better part of seven innings hammering his splitter into the ground, with only four outs recorded in the air. But the Mets didn’t have much luck against Austin Gomber, and the game was 0-0 in the sixth. Yes Virginia, at Coors Field. That was when the Rockies came apart, as Randal Grichuk turned a Brandon Nimmo single into a triple, followed by hits from Francisco Lindor and Jeff McNeil and an RBI groundout by Pete Alonso.

The Mets had a 2-0 lead, though this was Colorado, so it felt like they were actually behind — the first two Rockies singled, leaving Walker’s victory in danger of evaporating in the thin air. Walker coaxed a double-play grounder from Jose Iglesias, but pesky rookie Brian Serven slammed a ball past third.

Past third but not, it turned out, past Luis Guillorme.

Guillorme has been one of my favorites for years, with soft hands, a calm demeanor and flawless baseball instincts — he’s one of those players you can rely on to be in the right place and throw to the correct base without having to think things through. Severn’s hot shot knocked Guillorme backwards, but the ball stayed in his glove and he scrambled to his feet, completing the circle momentum had already begun, and fired a missile to Alonso at first, retiring Serven by two steps and getting Walker out of the inning. And he’s somehow hitting .338!

Of course, there were still six outs between the Mets and victory, which can be a hard road in Colorado — and the journey looked harder when Adam Ottavino sandwiched a pair of walks around a groundout. Ottavino rides his frisbee slider to great effect except when said frisbee starts sailing a little too far, in which case that slider can wind up riding him. It can be frustrating to watch, but Ottavino doesn’t scare, and he took apart the dangerous C.J. Cron on three pitches, then left in favor of Joely Rodriguez, after which Edwin Diaz secured the win.

Ho-hum — except a 2-0 win in Coors Field is anything but ho-hum. Here’s one to remember in another decade or so, when the Mets once again finish a game in Denver with that rarest of sights on the scoreboard — a zero.

by Greg Prince on 22 May 2022 1:17 am Unlike those Let’s Make a Deal-type distractions they run between innings on CitiVision, a day/night doubleheader is not a “double or nothing” proposition. The Mets didn’t risk their Saturday afternoon prize by opting to play again a few hours later. Hence, they get to keep their 5-1 win despite being saddled with the 11-3 loss that awaited them in the Colorado darkness. That’s a relief…even if “that’s a relief” is not a phrase you heard yourself thinking as Adonis Medina and Chasen Shreve went about permitting seven runs in the bottom of the sixth.

I’m surprised MLB’s engagement with gambling consortiums hasn’t led to a “risk it all” element to spice up twinbills. I mean for the standings, not the gambler. Win twice, get four Ws. Lose the nightcap, slide down behind the Nationals.

Enough giving Manfred’s marketing marauders dangerous notions. Although Daylight Savings Time is already in progress, what say we set our Met clocks ahead to 3:10 PM New York time, direct Brandon Nimmo to the on-deck circle (as if he’s not already there practicing taking) and get on with the first pitch of Sunday’s game, all the better to forget Saturday night’s affair?

What Saturday night affair? See, it’s already forgotten!

by Greg Prince on 21 May 2022 6:57 pm The Mets needed lengthy starting pitching in their Saturday afternoon makeup of Friday night’s snowout, since it was to be followed by a regularly scheduled Saturday night game, and they pretty much got it. Carlos Carrasco, in his first Coors Field start (and probably the first game he’s pitched on May 21 that was postponed by snow on May 20), went five-and-a-third and held the Rockies to one run. That’ll take some pressure off your bullpen.

The Mets needed dependable relief pitching Saturday afternoon. They need dependable relief pitching every morning, noon and night, but when you find yourself with two games in one day and another game the next day, you’d prefer to not blow out your bullpen before the second game of your series. Adam Ottavino got the Mets through the two-thirds of the sixth that remained after Carrasco left. Drew Smith was back to his solid self with a solid seventh. And classic Six-Out Seth Lugo reappeared from late frames past, pitching the eighth and the ninth, which was big both because you want six outs with minimal fuss and you want your usual closing option, Edwin Diaz, available for the night game. All told, Carrasco, Ottavino, Smith and Lugo teamed to hold the Rockies to fewer than two runs, something no opposition pitching staff had done at Coors Field for 84 consecutive games. It was a National League record. It still is, but it’s now over as an active streak.

The Mets needed more than one run if that’s all they were going to give up to the Rockies. They got it two batters into the game. Brandon Nimmo from nearby Wyoming — Rocky Mountain geography is different from yours and mine — reached on an infield single and Starling Marte deposited the first pitch he saw beyond the reach of the outfield. One swing after time on the bereavement list for Starling, two runs scored. The Mets needed Starling Marte.

The Mets needed Patrick Mazeika to catch at least one of these games not to mention all of those pitchers. Mazeika did that and hit, too. In the second, Dom Smith was on second, Luis Guillorme was on first and Patrick was at bat. The catcher who’d be at Syracuse had James McCann’s hamate bone not required repair stepped up and doubled both runners home. By the time Cookie was back on the mound for the bottom of the second, he was staked to a 4-0 lead.

You can never have too many runs at Coors Field, it is said, yet the Mets had enough. They went on to win, 5-1, and, unlike stray dollops of snow in the sights of the Coors Field grounds crew, didn’t have to worry about being swept on Saturday. The Mets have won at least one game in every doubleheader they’ve played this year and last, nineteen thus far. They also won that unofficial doubleheader at the end of August, the one that commenced by continuing a suspended game that had barely begun in April. So although we as fans tend to approach two games at once with a degree of trepidation, the Mets evince no fear, no matter how few degrees are in the air in Colorado on a given weekend in late May.

We’re fans. We worry about everything. On to worrying about Saturday night.

by Jason Fry on 21 May 2022 9:30 am Roger Angell died yesterday at 101. Greg offered his tribute here last night, shortly before the Mets and the Rockies spent the night staring out the window waiting for it to at least resemble spring. There will be many other such tributes, as there should be.

To that avalanche of grief let me add my own couple of rocks.

I was a child and a relatively newly minted baseball fan when someone gave me a paperback copy of The Summer Game, which I remember inspecting with a certain trepidation: It was very long, the print was very small, and it was filled with names of bygone baseball players I didn’t know. But after reading that book, I felt like I did know them — my baseball education came from trivia and factoids on the backs of 1970s Topps cards and from Angell, who brought Willie Mays and Stan Musial and Sandy Koufax to life for me. As it turned out, the only problem with The Summer Game was that it wasn’t long enough, which is the nicest thing a reader can say about a book. (Happy sequel: I quickly discovered there were other Angell collections.)

But Angell also perfected the formula for what we do, and he did it before we were born.

He became a baseball writer in ’62 — fortuitous timing, as a foraging trip for the New Yorker brought him into contact with the newborn Mets, who became one of if not the team closest to his heart. (I remember clapping with glee when Angell, at the end of the epic ’86 chronicle “Not So, Boston,” declared he’d interrogated his divided loyalties from that World Series and realized he was above all else a Mets fan.) A lot of wonderful writing would emerge from that trip, but so did something else. Angell, inspired primarily by Updike’s “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu,” wrote with no walls between the professional and the personal. He was an excellent reporter, bringing players to life not just as extraordinary athletes but as people, but he didn’t shy from making himself part of that story. That was verboten in sportswriting, and its double vision was largely ignored as a New Yorker oddity, but decades after Angell pioneered the form it became the template for a certain slice of sports blogs.

Certainly it was the form we followed. Combining Mets’ wins and losses with the experience of observing them? Angell did that long before we did. The tightrope walk between being clear-eyed about team business and hopelessly besotted by wanting said team to prevail? He showed us how to navigate that too. I see Angell in every simile and metaphor I throw into the air and hope comes down in a way that makes a reader nod, or at least smile. He taught me all of that when I was 11 or 12 — the only thing missing was an outlet for it.

And he made being a fan so much richer. Every late fall or early winter brought a clear-my-calendar evening when Emily told me Angell had chronicled the now-concluded baseball season. When that night arrived in 2006, I was not only a grown-up (at least chronologically) but had also blogged the better part of two baseball seasons. For the second season, Greg and I had chronicled the Mets and their giddy, never-in-doubt division title, their joyous pummeling of the Dodgers in the NLDS, and their exhausting, ultimately futile heavyweight bout with the Cardinals. It was an experience I figured had armored me and imparted a certain emotional distance. But then I read Angell’s account of it, which he ended like this:

I have studied the very last pitch — as delivered by the Cards’ very tall, right-handed closer Adam Wainwright — in replays and then over my own IF ONLY mental video, and have watched it repeatedly plummet past Beltran’s gaze like a bat in an elevator shaft. Time to go home. Instead, just lately, I’ve gone back to Jose Reyes’s shot to right center, and now see him catching a fraction more of the ball with his slashing bat, and the ball, this time, taking a course that carries it a yard or two more toward right and lands it there, in for a double. Noises rise, the score is tied, with one out, and Lo Duca is just coming up.

When I read that in November 2006 and saw the little New Yorker diamond that meant it was the end of the article, my brain slipped its track for a moment. And then, to my astonishment, I began to cry. Not a little chest hitch ahead of a moment one could hand-wave as allergies or a bit of dust in the eye, but a child’s dissolve into shocked misery.

That paragraph is everything we’ve ever tried to do at Faith and Fear, only perfected. The dispassionate observation of the scene, leavened with details personal and piercing. The intriguing but slightly lampshade-on-the-head simile. The exquisitely chosen detail — “with his slashing bat” is concentrate from which Jose Reyes is instantly reconstituted. The wistfulness for what might have been — that offset “this time” is doing a lot of work — and the way it rope-a-dopes you into the last sentence’s glimpse into a better world that never was. That’s the emotional KO, the part that leaves you on the mat looking up and wondering what just happened.

It was perfect now and it’s perfect then. Thank you, Roger. For everything.

by Greg Prince on 20 May 2022 4:56 pm “The Mets — ah, the Mets! Superlatives do not quite fit them, but now, just as in 1969, the name alone is enough to bring back that rare inner smile that so many of us wore as summer ended.”

Summer, in a sense, has ended with the news that Roger Angell, who wrote the above sentence in the aftermath of the New York National League pennant push of 1973, has died at 101. Sixty years ago, Angell, already an accomplished editor with the New Yorker, carved out a branch to his oak of a career, becoming his esteemed publication’s baseball writer. Before Angell, perhaps it would have sounded odd to think of the New Yorker as having a baseball writer. Because of Angell, millions of baseball fans consider the New Yorker a baseball magazine.

Angell grew up a Giants fan in Manhattan, but in Spring Training 1962, he was drawn to the Mets, and weren’t we the beneficiaries? Roger couldn’t resist St. Petersburg, “the old folks behind home” or, of course, Casey Stengel. He couldn’t resist following us back north, where he defined us before summer began. Angell wrote of the scene at the Polo Grounds when the joint jumped to support the baby Metsies as they endured the return of the powerful Dodgers to the five boroughs, documenting the first “full, furious happy shout of ‘Let’s go, Mets! Let’s go, Mets!’” And that was with the Mets losing by about a million runs. He was humming along to our tune from the Let’s-go get-go, and he wrote the lyrics to our biggest numbers on and off for the next six decades.

Roger Angell was one of us. He was a Mets fan more often than not. When he was, he was a Mets carer of the first order. And, in the realm of what you read in this space, he was the Mets chronicler who inspired us. I’m not doing this blog without Roger Angell setting the bar out of the reach of mere mortals and neither is Jason. We grew up and older reading his books, his articles, his every word about baseball. We smiled that inner smile every December that the issue of the New Yorker containing his postseason essay appeared on newsstands. We listened whenever we were lucky enough to tune into the documentary that was smart enough to book him as the talking head who’d seen so much that you’d almost thought he’d seen it all. Roger Angell was born in 1920, so, yeah, pretty close.

“One more thing,” Angell added to his many observations regarding the National Pastime in the early 1990s. “American men don’t think about baseball as much as they used to, but such thoughts once went deep.” In the case of Roger Angell, that’s where our affection for the summer game, as brought to us through his eyes, resides. Well over the 410 mark, and still going.

by Greg Prince on 20 May 2022 11:37 am The withstanding has begun. The Mets are 1-0 in the What The Hell Are We Going To Do Now? era. It will last anywhere from six weeks to eight weeks to whenever it actually ends. When you see Max Scherzer glaring from a mound near you, you’ll know it’s over.

For a spell on Thursday, it was hard to feel good about a team in first place by a healthy margin playing a close game because what did it matter what 25 other players did if the most significant among them — certainly in the top tier — wasn’t going to be available for his next start or the start after that or several to many starts after that? The original plan was to supplement Jacob deGrom with Max Scherzer. Then the plan was to cope without Jacob deGrom because we had Max Scherzer. The next plan won’t be nearly so glamorous. Scapulas. Obliques. The body parts pile up. The multiple Cy Young winners don’t.

Yet there were the Mets, facing down the Cardinals in a matinee that gripped your attention beyond the IL bulletins. It had everything you could want unless all you want out of every game is a stomping of the opposition (not an unreasonable desire). It had the Mets in front, the Mets tied, the Mets back out in front, the Mets holding on for dear life, the Mets having dear life all but slip from their fingers, the Mets behind and the Mets winning on one of the biggest swings you’ll see in any year. It had legends leaving our midst in Albert Pujols, playing first base like a real National Leaguer and nearly hitting one to the Marina before it politely declined to exit the park, and Yadier Molina, called into action as an injury replacement and unleashing one final mind’s eye glance of the ghost of Aaron Heilman (2022 postseason pending, because it’s not crazy to speculate a rematch of 2006 might be in the Cards). It had underappreciated superstar Paul Goldschmidt on fire, with a homer, three hits and four RBI. It had a new nettlesome Redbird, Juan Yepez, delivering three hits and the notion that the Cardinals never go away.

And those were just the visitors. The home team held its own and then some. It had Jeff McNeil, making like Bobby Ewing, discovered as alive and well and taking a shower by wife Pam on Dallas. Bobby was assumed to be dead for an entire season, but it was all a dream. That prime time soap opera’s jawdropping plot device serves a template for 2020 and 2021 where Squirrel’s resurrected career is concerned. The McNeil we see now is the McNeil of 2018 and 2019, and don’t we want to keep tuning in? Jeff drove in three runs, spread left field leather and has updated his status to essential Citi worker. Francisco Lindor was on base a bunch, too, and kept the ball in the infield while on defense. And, oh yeah, the Polar Bear roared, especially on that final crack of the bat, the two-run homer that rescued the Mets from a tenth-inning deficit with a ball that traveled two or three galaxies, or far enough to seal a 7-6 win with a two-run homer. The Mets’ rally began when MLB put Lindor on second to start the inning, eerily similar to how the Cards’ push in the top of the tenth began. I wish they wouldn’t do that. The Mets and Cardinals solved a 25-inning game once up on a time, a 20-inning game another time and an 18-inning game in fairly recent memory. Extra innings should be allowed to breathe.

As long as Pete Alonso is allowed to swing.

Chris Bassitt, the new ace of the Mets’ rotation, gritted per usual into the seventh. Neither Drew Smith nor Edwin Diaz was leakproof. Winning pitcher Colin Holderman got as much of the job done as he needed to. He came in with an unearned runner on second. Can’t blame him for that. The Cardinals scored their go-ahead run on a weak infield hit that moved said ghostly figure to third and Pujols grounding into a DP, which for much of Pujols’s career would have been an optimal outcome. Man, Pujols. After Pete treated his helmet like a basketball and shot it into a crowd of his teammates surrounding home plate — nobody got hurt — an SNY camera found Prince Albert heading down the tunnel for the final New York time. There goes greatness, I thought. When Albert retires, that’s basically it for that sense, unless Miguel Cabrera comes by next year. Otherwise, Albert is it from my perspective.

There are other superb active players of tenure who’ve built long, superb careers still in progress, but I haven’t experienced them quite the same way. Nobody whose National League bona fides go back quite long enough to seem like they didn’t commence “a few years ago”. Nobody who I don’t sort of see as a “youngster,” even if they’ve reached an advanced baseball age. Albert Pujols was the best hitter/player in the National League twenty years ago, right there with Barry Bonds. He endured at the top of the game for a decade. Then he departed St. Louis and continued to ply his craft out west in the junior circuit. The bottom line numbers increased even if his pace fell off drastically. The aura wasn’t what it once was once it was transplanted to Anaheim. I continually read that his presence had morphed into a liability. I didn’t want to hear it. To me, Albert Pujols was Albert Pujols in the way that Willie Mays was Willie Mays, and Hank Aaron was Hank Aaron, and Roberto Clemente was Roberto Clemente, and Frank Robinson was Frank Robinson when I was a kid. You get older, hardly any opponent resonates with you like that.

Pujols did. I didn’t want him to beat the Mets on Thursday. I never particularly welcomed any of the 93 career hits out of his total of 3,314 and counting that were registered at the Mets’ expense. I was just happy to see him out there in Flushing one more time, playing first, still at it as he might have been at Shea, where Mays as a Giant and Aaron as a Brave and Clemente as a Buc and Robinson before he was an Oriole all excelled and could be applauded for what they’d done and who they were. When that ball Pujols hit off Smith to end the seventh somehow fell into McNeil’s glove at the track in left, keeping the Mets ahead by one…well, I surely didn’t want it to go out with the game on the line. Yet I wouldn’t have begrudged the man. Cursed a little, perhaps. But not begrudged.

Priorities are priorities. The Maxless Mets had to win yesterday. Had to. With no Scherzer joining no Megill, never mind no deGrom, you can’t squander a Bassitt start. The starters who are staples — grinding Chris, along with Taijuan Walker and Carlos Carrasco, have to give us competitive outings and we have to back them up with ample support when they do. When we’re into David Peterson and Trevor Williams territory, we might need the bullpen to crank up a little sooner. Players need to emerge from slumps sooner. It was good to see Eduardo Escobar stinging the ball. It’s wasn’t so good to see him having trouble picking it up, but that’ll happen. What’s really good is everybody picking each other up. Yesterday was a had-to win because if we’re gonna be staring a bit into the abyss, giving it a glance with a seven-game lead as we are currently is about as ideal as we could imagine. Same for this just-completed homestand: three one-run losses that didn’t stop us from securing four wins and climbing twelve games above .500.

Let’s not gloss over where we are, even as we ask, “What the hell are we going to do now?” The Mets are seven games in front after forty games. Not impenetrable (we were memorably seven games in front after 145 games in 2007). But this is a solid lead constructed by a solid team right when it’s most needed. It may be hard to reckon good news within the context of doom Scherzer’s diagnosis wrought, but if a seven-game lead doesn’t seem encouraging, then you may need to reread the standings. Having built a seven-game lead is a damn sight better than being seven games behind. Building the lead to eight games, then nine, then more, would be optimal. If that becomes too tall an order, then withstand as you did on Thursday. The Mets closed out the first quarter of the season on a high note on the field. The more you win in the first quarter, the less damaging a given loss in the next three quarters will be. Pete Alonso, pretending to play hoops after going yard, obviously knows about first quarters and fourth quarters and the quarters in between. Winning on Thursday felt more gargantuan than simply taking one out of 162. Losing one on Thursday would have loomed even larger in the wrong direction. Losing No. 21 was bad enough.

Winning on a walkoff home run is a favorite thing for any fan, but there are others. National League Town explores a few more of them here or wherever your 447-foot blasts take you.

by Jason Fry on 19 May 2022 2:28 am Can the Mets win by seven and have that feel like an afterthought?

It turns out they can — if the takeaway from the game isn’t a blast of a homer by Pete Alonso or a hustling triple by happily hale and hearty Brandon Nimmo or a host of hitting to break the second half of the evening’s entertainment wide open.

Nope, the lasting image will be from the sixth, when Max Scherzer threw a slider to Albert Pujols and immediately signaled to the dugout that his night was finished — a very un-Scherzer thing to do, one that left a fanbase’s season flashing before its eyes.

It’s an annoying tic of being a Mets fan that we immediately assume not just the worst but the apocalyptic — we are the franchise of the Miracle Mets, the ball off the wall, Ya Gotta Believe and the unlikely series of events that culminated with a little roller behind the bag that got through Buckner, so there’s been some good fortune along the way. And yet it’s what we do, a habit that for most of us long ago went from superstitious to reflexive. About two hours before Scherzer’s unexpected walk, I was at a work function and conversation came around to how the Mets looked awfully sound. I agreed they did, but couldn’t resist remarking that as a Met fan, when things are going well I look over my shoulder like, ‘Oh God what’s that?’ ”

Which became the question of the minute, hour and possibly campaign not so long after that — what had happened to Scherzer? My kid, at the game with a friend, texted me immediately for updates I didn’t have. Like everybody else, I turned frantically to Twitter’s army of lip readers. Was Jeremy Hefner saying it was bad? Did Scherzer say he felt something pop? I watched that last slider like it was the Zapruder film, and thought I’d spotted Scherzer pulling his elbow into his side, trying to protect that critical little stretch of ligament from something that can’t be guarded against.

The culprit, according to Scherzer, wasn’t his precious UCL but his left side, which went from tight to problematic on that one pitch to Pujols, after which Max opted for caution and departure, never mind the optics or the glass case of emotion in which the viewing audience was trapped until the postgame show.

So now Scherzer will probably head for the confines of an MRI tube, and we’ll wait for updates. Which might well be bad: oblique injuries and other maladies can linger, cause a pitcher to unwittingly change his delivery, or otherwise be the first stone in an avalanche. But the side isn’t the arm. It isn’t the arm, and so we wait, and try to remind ourselves that even the Mets get a good outcome every now and again.

|

|