The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 10 May 2021 11:38 am You want the Jacob deGrom who locks in, who maybe seemed a little off in the first or second inning, but wasn’t allowing any baserunners, but then he’s on by the third, and seems on to stay. You fist-pump the Ks, but you secretly embrace the efficient outs. You count his pitches because his manager and pitching coach count his pitches. You want that Jacob deGrom on the mound — and you want that Jacob deGrom at the plate, handling the bat, advancing a runner, getting to first in process, coming around to score, being a ballplayer, helping his own cause…and then getting back to pitching like Jacob deGrom.

You’ll accept a slightly lesser Jacob deGrom who you reluctantly understand can’t be “Jacob deGrom” every batter of every inning of every game, the Jacob deGrom who is outstanding rather than perfect. You want that Jacob deGrom to overcome whatever’s not working — don’t worry, he will — and still be ahead of the opposition when he leaves the mound at the end of a relatively challenging inning.

You can’t deal with no Jacob deGrom, but sometimes you have to. You can’t deal with Jacob deGrom departing a game in the company of Brian Chicklo. You don’t want to hear Brian Chicklo’s name whatsoever, but sometimes the Mets’ head trainer needs to cross the foul line into our consciousness. The worst way for him to appear is when his job intersects with deGrom being physically unable to do his.

Sunday, we had silk deGrom for four innings, gritty deGrom for one inning and Chicklonian deGrom precluding any more innings. Reports of Jacob’s tight right side, and how it was apparently different from what kept him from starting last Monday, elbowed every one of us in the gut. We’d have rather shaken hands with total strangers during the depths of quarantine than see Jacob deGrom leaving a baseball game under Chicklonian circumstances.

The game was left in responsible hands. Miguel Castro. Jacob Barnes. Edwin Diaz. Met relievers you can trust at the moment. Almost all the Met relievers are relievers you can trust at the moment. The moment can be fleeting, but the aforementioned fellows, along with those who made the intentional “bullpen game” on Saturday and the contingency version on Friday navigable, are to be commended. Same for the Mets on Sunday who made sweet catches (Conforto!), delivered timely contact (Lindor!) and displayed plate patience (Mazeika!). With a lot of help, Jacob deGrom was credited with the Mets’ 4-2 win, our stealthily first-place club’s low-key fifth in a row. Let his teammates lift him for a change. Lord knows deGrom doesn’t usually get much help and is too often credited with nothing but appreciative gasps of disbelief.

We gasped when we were told deGrom had to go for an MRI. We might breathe easier today having learned, via MLB Network’s Jon Morosi, that Jake’s “initial prognosis is good” and no “serious or long-term injury” is evident. We might breathe easier, but it’s not guaranteed. When we see Jacob performing free, easy and without Brian Chicko, we won’t have to think about our breathing. It will come naturally, just as watching and loving Jacob deGrom does. Jake is oxygen to us. You can’t cut off our supply and expect us not to be adversely affected.

by Jason Fry on 9 May 2021 10:43 am The last time I saw Citi Field, Dom Smith was bringing down the curtain on the 2019 season, connecting for a walkoff homer in Game 162. That happy memory sustained me through the winter, but nothing could sustain me once our lives ground to a halt in a surreal spring. I saw Citi Field in 2020, but it was on my TV, or off to the side of the highway heading to or from the Whitestone. It was close but also closed, a strange disconnection — a short subway ride somehow turned into an unbridgeable distance.

So with a second jab in my arm and the calendar having advanced two weeks beyond that, you can imagine where my thoughts turned — and Saturday, as it happened, was both two weeks after my wife’s second shot and my birthday. Sometimes the universe isn’t particularly subtle about giving you a hint about where you belong.

So there we went, through once-familiar paces: rattling around in the 2/3 to Times Square and then trekking with the 7 out to Citi Field, underground until Queens, then a long slog on the elevated line, forgetting as usual that there are approximately 53,912 stops on this line, until finally we could see the tennis complex and the lights and the parking lot and the park, culminating with the sigh of the opening doors at Willets Point.

OK, this was pretty. For those worried about the new protocols, I can report with a certain pleased surprise that the Mets made everything about as easy as it could be — checking vaccine cards/tests and temperatures was brisk and efficient, and the socially distanced seating worked well, in part because the Mets have literally zip-tied seats that aren’t in use. To my even greater surprise, our fellow Met fans were cool about everything — I think a year has taught all of us to instinctively give each other a little wider berth than normal, and we witnessed nary a mask-related tantrum nor act of disobedience, whether performative or merely careless. I can’t speak to your risk tolerance, obviously, but if you’re wary of the idea of a ballgame, it may go better than you think.

Problems? There were a couple: Citi Field’s food options have been greatly curtailed, I hope temporarily, and most of our favorite ballpark haunts were lamentably dark and shuttered. The outposts that offered pricey but palatable craft beers seem to be no more, replaced by invitations to try Coors hard seltzer, because I guess someone in this great land needed a Coors product that’s even closer to water. And this one’s on the MTA, but the main exit from the subway was inexplicably closed, forcing everyone through a far narrower gate and an awkward interval of mandatory social converging.

The reduced crowd also meant an odd vibe: The population was what you normally see for games when the team’s 30 games out and autumn’s chugging towards you, but it was made up of fans far more invested in the outcome than the usual garbage-time spectators. That meant plenty of cheers and complaints and rolling Let’s Go Metses, but they lacked the fuel needed for ignition — there’s an R number we didn’t want to dip below one. The result was something you might call ambient baseball.

(The game was also glacial — both in terms of pace and temperature, the latter of which I made worse by insisting that yes, lighthouse-keeper conditions were suitable for a cup of vanilla soft-serve. Nice to know that even in my graybeard dotage I can come up with bad ideas.)

But ambient noise or not, cold or not, I was still surrounded by baseball — and oh my how I’d missed it, from the old Shea apple in its bed of tulips and the dopey between-inning contests to marveling anew that nine guys can cover a huge expanse of green grass, appearing out of nowhere to snatch balls out of the air and off the ground. (OK, I was wrong about Kevin Pillar being useless.)

One thing I did recall quite quickly was how different a night in the park is compared with the close study allowed by TV: I can’t tell you anything about Joey Lucchesi‘s curve or the home-plate ump’s strike zone or what happened to Jeurys Familia in an inning of flukey ground balls, because it was happening in another area code. What did translate was that various Mets we’ve worried about — Michael Conforto, James McCann and Francisco Lindor — struck several balls solidly, though only Lindor saw that turn into statistical bragging rights. Lindor is also an on-field presence even from afar, a wellspring of chatter and gestures aimed at his fellow fielders. I can see how that might annoy a colleague on occasion, even if zoology isn’t actually involved, but mostly it seems like a positive, a way to keep all concerned on their toes. Watching Lindor, in fact, I was reminded of Keith Hernandez and how he made his entire infield embed more deeply into pitches and at-bats — and how Hernandez was praised for playing first base like a shortstop.

After a not so tidy three and a half hours, Trevor May coaxed a harmless fly ball from David Peralta and the Mets had won. That’s always a nice birthday present; so’s feeling like you’ve been given a much-missed piece of your life back, and finding it a little different but fundamentally the same, in every way that’s truly important, as when you had to put it aside.

by Greg Prince on 8 May 2021 1:27 pm In the movie Thirteen Days, presidential advisor Kenny O’Donnell warns naval Commander William Ecker that when he leads a reconnaissance mission over Cuba to photograph evidence of missile bases on the island, it is imperative that his squad not be shot at. That’s not up to Ecker, of course, but O’Donnell’s message sinks in. President Kennedy can’t have a trigger incident while trying to maintain world peace, a precious commodity very much in the balance in those fretful weeks of October 1962. Thus, when the mission concludes, and it’s clear Ecker and his men have been fired at — the bullet holes in his plane couldn’t be more visible — he simply reports back that what obviously happened didn’t happen.

“Damn sparrows,” he said as his wingman and a member of the ground crew examine the damage. “Must’ve been migrating…probably hit a couple of hundred of them.”

“These 20-millimeter or 40-millimeter sparrows, sir?” Ecker is asked incredulously.

“Those are bird strikes. Sparrows to be precise. That’s the way it is, guys.”

It’s a white lie in service to a greater purpose, namely the avoidance of World War III. The viewer of the 2000 film knowingly nods along with Commander Ecker when he gives the others a quick, stern look to accept his story and move on.

Friday night’s Mets game versus Arizona was not the Cuban Missile Crisis. It didn’t require the cover of national security. Francisco Lindor didn’t need to weave a transparent tale of a rat or raccoon loitering in the tunnel that leads to the Mets dugout to explain why there was a heavily inferred disturbance involving him and Jeff McNeil, the second baseman who, prior to the apparent mid-seventh inning dustup, had gotten in Lindor’s way while he tried to field and throw a ground ball, a traffic snarl that allowed a Diamondback to reach first. Anybody watching on SNY knew something was up between double play partners because a) most of the other Mets ran down the tunnel to see what was up; and b) neither Lindor nor McNeil looked immediately afterward like he’d just been engaging in anything resembling spirited rodent-related bonhomie.

Lindor still appeared put off moments later, even after hitting his dramatic inaugural Citi Field home run, which tied a game the Mets seemed to be out of from early on. If a fellow known for smiling can’t grin from that, what gives?

What gave before the Tussle in the Tunnel was David Peterson lacked control (three walks and a hit batter in an inning and two-thirds), and the Mets were in a 4-0 hole after two-and-a-half innings while not doing much to scraggly D-Backs starter Zac Gallen. But a battalion of Met relievers reported for duty and acquitted themselves with valor, particularly newcomer Tommy Hunter, who chipped in two scoreless frames.

Hunter’s new to the Mets but hardly new to baseball. He debuted for Texas in 2008, one night before Daniel Murphy broke in as a Met. Hence, he probably understands that in games that seem to be getting away, the longer the run total for the team that’s ahead stays static, the greater the possibility becomes that the team that’s behind is not, in fact, out of it. Sure enough, with the likes of Tommy holding Arizona at bay in the tops of innings; and with a run in the bottom of the third (scored by Lindor); and another in the bottom of the sixth (driven in by Jonathan Villar), the Mets were back in this thing. Even McNeil cutting in front of Lindor to allow Nick Ahmed an infield single didn’t lead to disaster.

The same can be said for whatever went on in the tunnel. Boys will be boys, teammates especially. We can all dig that story. It’s probably not ideal to think your recently inked (for the next ten-plus years) superstar shortstop is not communicating with your squirrelly second baseman, and that maybe the vaunted Cookie Club clubhouse chemistry is being stirred bad, to borrow a classic Reggieism, but baseball behind the scenes is month after month in close quarters, requisite adjustment periods for the new guys to mesh with the old guys, biorhythms that don’t necessarily sync — not everybody has to actively love one another every inning of every day.

We, on the other hand, had to love that the heretofore slumping Francisco belted a tall two-run homer toward the left field foul pole in the bottom of the seventh and we suddenly had a tie game. Mr. Smile wasn’t really living up to his nickname after the blast, seeing as how he had to return to a dugout occupied by McNeil, but the scoreboard lit up nonetheless. We at home were curious, and you couldn’t blame those who’d be interviewing Lindor later for wondering what the hell was going on.

When we reached the start of the ninth, Arizona third baseman Asdrubal Cabrera, who once upon a time caused his own short-lived ruckus by demanding a trade from the Mets rather than consent to play second base for them, singled convincingly to right off Edwin Diaz. Less convincing was Cabrera’s attempt to stretch it into a double. Michael Conforto unleashed a bullet even Commander Ecker couldn’t deny and Lindor tagged his fellow former Tribesman. Considering Asdrubal’s failure to reach the bag, he must still have something against second base.

We went to extras, which don’t feel like extras in the 2020s given the automatic presence of an unearned runner on second, but if that’s how you want to play it, Manfred, fine. Aaron Loup pitched a scoreless tenth despite not being allowed to commence with a clean slate. Stefan Crichton wasn’t so lucky for the Diamondbacks in the bottom of the inning. Pete Alonso magically appeared on second (last out of the ninth). Dom Smith almost as magically appeared on first (intentional walk). After Kevin Pillar flied out to advance Alonso, Jonathan Villar was passed to first, too. Three baserunners, none of them having done so much as stand in to face Crichton.

The bases were loaded. Loup’s spot was up. The batter was going to be Patrick Mazeika, he of the one career at-bat. Luis Rojas is one of those managers who’d rather awkwardly attempt to answer questions about rats and raccoons than deploy his last backup catcher, but he’d double-switched James McCann out and Tomás Nido in back when Robert Gsellman took over for Peterson, and the bench was down to Mazeika and pitchers. Were he certifiably healthy, I would’ve opted for pinch-hitter Jacob deGrom. Mazeika had never had a major league hit, but he’d only made one major league out before. You never know if Patrick Mazeika can drive home a decisive run until you let him try.

Luis let him try. Mazeika had himself a fierce AB. A couple of balls. A couple of foul balls. He would not go quietly. On the fifth pitch he saw from Crichton, he did one of the better things he could do. He put it in play and not directly at anybody. It went about, oh, maybe twenty feet, but Crichton’s attempt to field and throw it was about as successful as Lindor’s when McNeil got in Lindor’s way. The pitcher’s scoop to his catcher was off-target and Alonso, who isn’t much of a runner, scampered home. Pete’s a swell scamperer.

For a moment, it was pure shirt-ripping joy at Citi Field. It was Patrick Mazeika, who was promoted twice last season, only to be sent back down without as much as a Hietpas helping of action, bare-chested and jubilant. He was an alternate site All-Star, a taxi squad sitter, an almost chimeric figure in hipsterish glasses and substantial beard. Now he was a walkoff RBI hero, same as Cabrera in 2016 in the heat of the last successful Met playoff push (“OUTTA HERE! OUTTA HERE!”); same as Shane Spencer in 2004 (who beat the Yankees on a similarly slight base hit); same as Esix Snead in 2002 (who also chose a game-ending swing — a homer — to record his first major league run batted in); same as Todd Pratt in the clinching game of the 1999 NLDS (the backup catcher protagonist the last time the Mets beat the Diamondbacks in ten innings at home).

Then Patrick Mazeika and the 5-4 Met victory got a little lost in the shuffle because when Lindor took questions in the postgame Zoom, he gave answers less believable than that business about bird strikes in Thirteen Days and Mazeika’s game-winning hit dipped to subplot. Francisco really tried to sell the tale of the rat and raccoon, which made it only less buyable. His smile was big and broad as he went on about the vigorous debate he and McNeil engaged in, how he was sure it was a big New York rat (he’d never seen one) and McNeil claimed it was a raccoon, and all their teammates rushed down because, gosh, what a sight, right?

Riiiiiight.

The smile was also contrived, which is a bit of a blow to our conception of Lindor as a authentically embraceable figure. He was being as genuine as the rat/raccoon…or possum, which was McNeil’s contribution to the urban myth (Rojas mostly demurred). Listen, we all sometimes put on a happy face when we’re not feeling it, but geez, this was a billboard for Crest while the lie seeped through his undeniably bright teeth.

It became the night’s big story because Lindor made it the night’s big story. Again, world peace did not hang in the balance. Don’t make it into a postgame crisis by doing the one thing reporters can’t abide by: giving amazingly phony answers. It wasn’t cute. It wasn’t clever. If you gotta obfuscate, at least obfuscate better than that. Don’t be Bobby Bo pretending you were calling the press box not to complain about an official scorer’s decision but to check on Jay Horwitz’s cold. (Great, now we’re reminded of Bobby Bo.) Give us some reasonably honest jockspeak. “We got hot for a minute, we’re good now, anybody wanna ask me about my homer?” Something like that. Maybe it played badly because of how postgame media scrums transpire under pandemic restrictions, with only the player sighted on camera and the inquisitors’ voices disembodied, certainly from our angle.

Those people asking the questions, the ones who used to get to know the players in person, have jobs to do. They’re there to ask what we the readers, listeners and viewers are likely curious about. They’re not royal stenographers, Zooming in to blankly take dictation and ludicrous answers as gospel. They don’t wear team jackets, either, not even one as nice as the one from the Coming to America sequel the beaming shortstop modeled during Spring Training when everything was legitimately all smiles.

Francisco Lindor had two hits Friday night. He may be breaking out and settling in. The 14-13 Mets, winners of three in a row, might be getting their act together. The imaginary hitting coach kept them going for two days last weekend before the real hitting coaches got axed. The imaginary animals in the tunnel could become a rallying point. Or simply mostly forgotten. Right now they’re just another sign that these Mets are still having a difficult time coping with reality.

by Greg Prince on 7 May 2021 12:48 pm From the deep well of numerical sustenance baseball is wont to give us on any given day, Thursday afternoon it gave us, among other digital delights, 7 1-hit innings from Taijuan Walker; 1 base hit from Francisco Lindor after 26 hitless at-bats; 11 walks issued to would-be Met batters from Cardinal pitchers (including 4 consecutive in the top of the 5th); a franchise record 17 Met left-on-baserunners who prized their status so dearly that they refused to exchange it for a run; and, in a teeth-pulling nod to the American Dental Association, a 4-1 getaway day Met win in St. Louis.

We accept this result as Lindor accepted his trio of walks: all smiles. Francisco posted a .667 on-base percentage for the game and the Mets re-reached .500 for the 8th time this year.

Quite an eventful May 6, though to be honest, May 6 didn’t need any help from the Mets or the Cardinals to feel eventful — though someone who used to play for the Mets and someone who used to play for the Cardinals would take over most of the day’s baseball headspace. What needed to be done to make May 6 special happened when former Met and eternal immortal Willie Mays turned 90. Willie Mays has made every day he’s been associated with the playing of baseball special since he first picked up the game and then lifted it higher than anyone before or after him.

https://twitter.com/mlbnetwork/status/1390317724191055874

Tom Verducci wrote a tribute for MLB Network, narrated by Danny Glover, that dipped into the aforementioned well of numerical sustenance, but with a caveat: “You would no more define Mays by his 3,283 base hits than you would Miles Davis by albums sold.” The numbers were the steak. The player was the sizzle. The combination, as a plethora of birthday wishes underscored, is what made Willie a dish unsurpassed in baseball annals. Mike Lupica’s column for mlb.com said it as well as anybody:

Willie Mays is the greatest all-around player who ever lived, whose legendary career started at the Polo Grounds with the New York Giants in 1951. It means that for so many lifelong fans, he is the greatest player they never really saw. Even for the ones who did see him at his best, in the 1950s and ’60s, in New York and San Francisco, they go mostly on memories now, ones that No. 24 burned into their imagination forever.

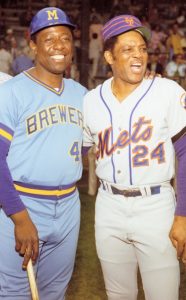

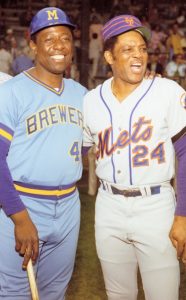

Still, annals are numerically inscribed, so whenever somebody has passed Willie Mays in some statistical category, it gets your attention. His stats aren’t very reachable to begin with, so it takes a special player to outpoint them. Take home runs. Hank Aaron slugged by Willie Mays late in both their careers. It was only slightly jarring. Aaron was Aaron, even though Willie was Willie and I’d never known a time where Willie wasn’t running 2nd to Babe Ruth on baseball’s most glamorous chart and/or table. In 1972, Willie the Met gracefully settled into 3rd place. Ruth, Mays, Aaron became Ruth, Aaron, Mays, which in short order became Aaron, Ruth, Mays — 755, 714, 660, respectively. That’s a Top 3 you can commit to memory and take to heart for the rest of your life.

Top 3 club meeting of those who could make it. 1976. If you lived to 2004, however, you saw the order upended. Barry Bonds passed Willie Mays with his 661st home run that April. Once Barry tapped previously unknown sources of power, his ascent up the list was inevitable. Nobody seemed prouder of the new No. 3 than the new No. 4, Bonds’s godfather Willie Mays. If it had Willie’s blessing, well, fine. Top 4 is still a pretty spectacular club, membership consisting of 4 giants and 2 Giants,

Bonds would go on to skip past Ruth and Aaron. A nation mostly held its applause. The Top 4 remained the Top 4 in composition if not order until 2015, when Alex Rodriguez hit No. 661. That truly annoyed me — A-Rod… — but what are ya gonna do? However he came to hit them, the man hit them. The totals were the totals. The Top 4 suddenly didn’t include Willie Mays. But the Top 5 did. As anyone who has repeatedly watched High Fidelity grasps, Top 5 has cachet. I wished Willie hadn’t been surpassed in home runs, but, honestly, can anybody be said to have surpassed Willie Mays?

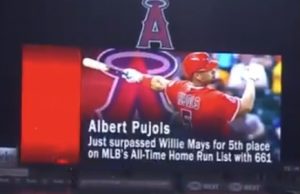

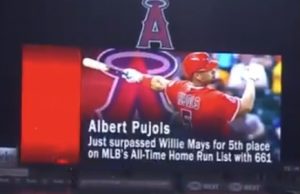

Emotions got mixed. The thought process came up again on September 18, 2020, when Albert Pujols of the Los Angeles Angels emerged from what seemed like a decade of Orange County hibernation to swat his 661st career home run. In a vacuum, I was all for Albert. He may be the last baseball player of a non-Met nature I would’ve been instinctively tempted to tack to my bedroom wall in poster form if I hadn’t been nearing 40 years old when Pujols emerged fully formed as the grandest Cardinal hitter since Stan Musial. For me, personally speaking, he’s always resided in that hushed “wow” strata of superstars, and that’s a difficult circle to open for entry when you’re not a kid anymore. I recognize greats to this day, but I haven’t been able to conjure awe for any who’ve debuted past 2010, and even then (Votto, Posey, Freeman) it’s more like solid appreciation. I’m reasonably familiar with the astounding work of Mike Trout and the Bettses, Sotos and so forth who’ve followed in his tracks, but I think there’s too much distance for me in my late 50s to get overly excited about anybody who’s not a Met. I’ve been watching baseball for more than a half-century. When it comes to baseball reverence, I’m not actively accepting new applications.

Albert Pujols and Miguel Cabrera have been the last players in other uniforms I’ve put on a pedestal. Pujols came up in 2001, Cabrera in 2003. I was too old to look at ballplayers that way by the time they swiftly ascended to their prime, but habit was habit. I looked at Bonds that way. Didn’t love him, can’t say I revered him, but part of me never lost the awe. Mike Schmidt struck me similarly, and believe me, I more or less hated Mike Schmidt. Vladimir Guerrero. Jeff Bagwell. Dale Murphy. Joe Morgan. Johnny Bench. Lou Brock. A couple of handfuls of others, maybe, all the way back to Frank Robinson, Hank Aaron and, of course, Willie Mays.

I was partially glad Pujols was still capable of knocking balls out of parks when he drew attention for hitting No. 661 last season — and then hit No. 662 in the same game. But I partially mourned Albert’s accomplishment because now Willie Mays’s 660 wasn’t even in Top 5 territory. Not that Top 6 isn’t sensational in the grand sweep of history, but it’s not Top 5. Willie Mays was more than home runs, more than statistics, more than what can be drawn from the numerical well. Even still. I don’t know where Miles Davis’s record sales rate versus, say, Kenny G’s, and I understand Billboard doesn’t measure artistry any more than Baseball-Reference does…but Willie Mays not in the Top 5 of all-time home run hitters? What is baseball without the statistical certainty on which we rely?

We’ll find out soon enough.

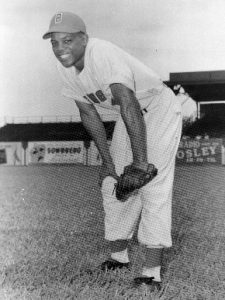

In the offseason, Major League Baseball announced it was ready to encompass under its statistical umbrella what we casually refer to as the Negro Leagues. Specifically, we’re talking the first version of the Negro National League (1920-1931); the Eastern Colored League (1923-1928); the American Negro League (1929); the East-West League (1932); the Negro Southern League (1932); the second version of the Negro National League (1933-1948); and the Negro American League (1937-1948). We might as well get to know the specifics. Until this move, too many of us have treated Black baseball as a gray area. We’ve heard of it. We admire what we know about its contents. We rue that society couldn’t bring itself to bring players of all colors onto the same field. Then, probably, we refer to thinking about “the major leagues,” which we reflexively know as the National League and American League, pre-Jackie Robinson and post-Jackie Robinson.

Well, suddenly some 3,400 players who never had the chance to be what have been called big leaguers will be called big leaguers. Separate leagues, equal footing, if you will. I was fortunate enough to sit in on a Zoom call with Negro League Baseball Museum president Bob Kendrick the December night the decision was announced. He called what was going on a matter of having “started the process of rewriting American history”. Good, I thought. American history could use all the help it can get. Same for baseball history.

Righting historical wrongs is Job 1 here. This is a tiny step in that direction. Blending numerical ingredients to create a satisfying statistical stew is next. If hits collected in games that weren’t sanctioned in their institutionally racist times are indeed major league, that unsettles the lists we’ve known all our lives. But if records are made to be broken, recordkeeping is made to be repaired. Figuring out where Oscar Charleston and Josh Gibson fit on a spreadsheet that already included Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb rather than confining their exploits to hazy legend will be a challenge. It will be worth it. It would have been better had everybody gotten to play in the same leagues. That ship refused to sail even a little until 1947. Statistics will have to do.

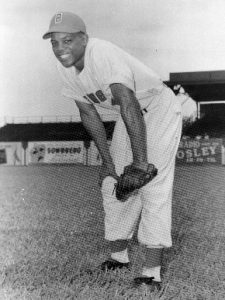

Among the gems unearthed by the monumental rediscovery process of these leagues was a newspaper report that noted a 17-year-old playing for the Birmingham Black Barons in the Negro American League homered against the Cleveland Buckeyes on August 11, 1948. A box score would be nice to have, but thus far none has been found. Still, the Birmingham News covered the event. And it was an event: It was the 1st home run of Willie Mays’s major league career.

Say Hey, that’s a promising kid. Yes, major league. That’s what the Black Barons were in practice and now that’s what the Black Barons will be in the annals. Thus, when Willie Mays was called up from the minor league Minneapolis Millers to play for the major league New York Giants on May 25, 1951, he had 1 major league home run in his pocket. For the Giants and Mets between 1951 and 1973, he’d hit 660 more, allowing him to end his major league career with 661.

That’s different. Slightly different, but different. Or not that different because, again, he’s Willie Mays, for whom the back of a baseball card constituted merely supporting evidence for what everybody watched him do on professional baseball fields from 1948 forward. Sort of like Albert Pujols’s 667 home runs are a mammoth total, but it’s the explosiveness of Albert’s swing that will stay with me long after the cruel irony of the Angels designating 41-year-old Pujols for assignment on May 6, 2021 — Willie Mays’s 90th birthday — is relegated to a footnote.

Nevertheless, despite a quarter-century’s worth of witnesses having attested to the greatness of Mays without feeling compelled to cite statistics, it somehow seems discordant to me that when we rattle off the Top 5 home run hitters in major league history, the list won’t include Willie Mays. Until last September, I’d never lived consciously as a baseball fan when Mays wasn’t up there. He was 2nd to Ruth; 3rd to Ruth and Aaron; 3rd to Aaron and Ruth; then Bonds and Rodriguez got involved. Finally, Pujols nudged him to 6th.

When, I wondered, did Willie reach the Top 5? I would have guessed he was born with 500 home runs, but no, he had to hit them like everybody else. By the time he got to No. 500 (or the 500 he hit in the NL after he moved on from the Black Barons) on September 13, 1965, he was already in the Top 5. The order was Ruth, Jimmie Foxx, Ted Williams, Mel Ott, Willie Mays. It had been listed that way for just over two weeks.

It got listed that way because of a home run Willie Mays of the San Francisco Giants hit at Shea Stadium against the New York Mets. The ball Willie socked was recognized as No. 494, or 1 more than Lou Gehrig, the former No. 5 all-time slugger, had hit. What made it delicious then and keeps it delicious now was the extra significance it carried. The date, you see, was August 29. The month was almost over. What a month August 1965 had been for Willie Mays…which is what could have said for Ralph Kiner in September 1949. In September 1949, Ralph hit 16 home runs. It was a National League record for most home runs in a month that had stood nearly 16 years.

But records were indeed meant to be broken, whether the reigning recordholder wished it shattered or not. Most recordholders, however, don’t have to describe to who knows how many people the shattering. Ralph Kiner had to. It was his job. He was calling the Mets-Giants game of August 29, 1965, just as he called every Mets game for a couple of generations. Ralph was working the radio side in the top of the 3rd inning that Sunday afternoon as the only other National Leaguer to have hit 16 home runs in a month stepped to the plate.

How did Ralph handle situation? Let’s listen in.

***It’s runners at 1st and 3rd, with Willie Mays coming up.

Willie Mays the batter.

And his 1st pitch is inside, a fastball, Willie started to swing and then spun around but held the bat back, and it’s ball one.

Mays all geared up, he’s got 40 home runs and 86 runs batted in. He’s batting .325. He has been on a terror streak here in this month, having hit 16 home runs so far.

Willie 5-for-9 against the Mets in the series.

And Fisher now back, in a 1-0 hole, and the next pitch is in the dirt for ball 2, and Mays says, ‘look at the ball,’ so the home plate umpire Stan Landes takes a look and throws it out of play.

2 balls, no strikes on Willie Mays.

Fisher a look at 1st and a throw there, but Gabrielson who picked off at 1st base his 1st time on only a couple of steps away. He was only a few steps away when he was picked off.

Now the 2-0 pitch. It’s hit deep to left field, going, going, going and gone!

So Willie Mays writes a new record book in the National League. He has just hit his 17 home run in the month of August, and that is an all-time record in the National League.

Well, it had to happen, there is no doubt about that.

Willie is hot, he’s the hottest man in baseball. He’s certainly a Hall of Famer, 1 of the greatest players that ever lived. That home run, his 494th, puts him ahead of Lou Gehrig in the home run derby, and it also knocked out Jack Fisher.

A high changeup, a perfect pitch for Mays to hit, it’s all over the left-center field fence.

And the Giants lead by a score of 5 to nothing on a 3-run home run. For Willie Mays, his 41st home run this year. He leads the major leagues.

Coming in now lefthander Gordon Richardson in place of Jack Fisher…

***Well, it had to happen, there is no doubt about that, but Ralph Kiner didn’t have to betray his emotions about being surpassed, and he didn’t, not on the air. Later, he told the Sporting News that maybe he wasn’t crazy about not holding that particular record anymore — or another record Willie had snatched from him two nights before. Willie had hit his 40th home run of 1965 off Tom Parsons on Friday, August 27, making it six seasons of at least 40. No National Leaguer had done that. Ralph set the previous standard with five. It had been tied by Ernie Banks and Duke Snider. Now they were all second to Willie Mays.

“In three games, I’ve seen two of my records broken by Willie,” Ralph said. “Sure, it hurts a little. A guy likes to have his name in the big book. but if somebody had to break them, I’m glad Willie did. He’s amazing.”

Pictured: all class. Ralph was all class. So was Willie. So, for that matter, was Lou. Lou Gehrig took a back seat to Willie Mays on the home run list, but he was still Lou Gehrig for posterity. Ralph Kiner took a back seat to Willie Mays on another home run list, but he was still Ralph Kiner, especially to us. Ralph was “certainly a Hall of Famer,” though the certainty wouldn’t be certified until 1975. Willie joined him in 1979. But it didn’t take them that long to get together after the record-shattering. Ralph had Willie on as his guest on Kiner’s Korner. It could have been uncomfortable had not so much class fit inside such a snug studio.

“Are you sore?” Willie asked his host.

“Sure, I’m sore,” Ralph responded as a great might to another great.

“I’m sorry, Ralph.”

Live 90 years, and you’re bound make somebody sore, even if somebody’s sort of kidding that he’s sore. Live 90 years like Willie Mays, and you’ll make most everybody happy.

by Jason Fry on 6 May 2021 2:16 am True confession time: Your recapper earns no accolades for being an attentive student of the game Wednesday night, dozing off before the conclusion of Game 1 (“Did they lose?” I asked Emily when roused) and remaining groggy and befuddled for a good chunk of Game 2. Just as well, since I figure we don’t particularly want to talk about Game 1 anyway — Marcus Stroman pitched well except for one pitch he shouldn’t have had to make to Met killer Paul DeJong, while the somnolent bats made you wonder if it was too early to fire Hugh Quattlebaum, and let’s leave it at that.

Game 2 was far more enjoyable, as the Met Plan Bs stepped up where some of the front-line players have faltered of late. You had the -illars, Kevin P and Jonathan V, contributing on both sides of the ball and giving the Mets’ tempo a welcome kick alongside their nightly pronunciation challenges. (By the way, points to Steve Schreiber for suggesting we refer to them as Kevin Public Relations and Jonathan Virtual Reality.)

In the second inning of the nightcap, the Mets looked like they were going to waste a second-and-third, nobody-out situation, as they have far too often in 2021: Villar and Jose Peraza made contact but neither hit the ball deep enough to score Dom Smith from third. But Smith scampered home on a wild pitch by Johan Oviedo, who got no help from momentary 2020 Met backup catcher Ali Sanchez, and then current Met backup catcher Tomas Nido drove Oviedo’s next pitch into the left-field seats for a 3-0 lead. It struck me as possible there might have been an easier way to get those runs home, but hey, whatever works.

To my delight, the next hitter was Patrick Mazeika, on the roster for a single day last August as Nido’s backup. Mazeika never got into a game in 2020, becoming the 10th ghost in Mets history, and between his modest minor-league CV, the acquisition of James McCann, and the Mets stockpiling other catching options, I had the uneasy feeling that day spent in the dugout might be closest he’d get to a big-league line in Baseball Reference. Which isn’t a fate I wish on anybody — being a team-specific ghost is an oddity, but being an MLB ghost is a tragedy. Of the once-again nine spectral Mets, that cruel fate has been reserved for just two — catcher Billy Cotton, who supposedly was on deck to pinch-hit in 1972 but saw the Met at the plate hit into an inning-ending double play, and Terrel Hansen, who never got that far in ’92, stuck to Jeff Torborg‘s bench while his cup of coffee went untasted.

But nope, there was Mazeika, at the plate and so in the books. He grounded out almost instantly to first and I guarantee you he doesn’t care a whit about that outcome right now, and at least for a day he has no complaint whatsoever with teams using openers. Mazeika’s time as the newest Met was brief, as the man he pinch-hit for, Miguel Castro, gave way to the just-recalled Jordan Yamamoto. Yamamoto pitched serviceably enough, helped out by a nifty throw from Pillar to nail Sanchez at the plate and by the fact that PR and VR kept pouring it on, leading to a tidy enough final score of 7-2 and a chance to exhale before tomorrow’s matinee.

If Mazeika never returns to the big leagues, at least we’re using a different verb than we did a year ago. And how about that two-batter stretch, anyway? Baseball bingo cards are filled with oddities, but good luck drawing a one-year reunion of 2020 Met backup catchers, with Sanchez getting a ringside seat for Nido’s heroics and Mazeika’s escape from ectoplasm.

Who knows? Maybe it’s a sign that James McCann will do something in 2022.

by Greg Prince on 5 May 2021 12:25 pm Rainouts are no good unless they save you from an emergency “bullpen game” being thrown together because Jacob deGrom has a tight ride side. Jacob deGrom having a tight right side is no good at all, but if it’s not tight enough to send him to the injured list, then it could be worse. The Mets having new hitting coaches? It is what it is.

Nobody ever says “it is what it is” about anything good. Even still.

Farewell, Chili Davis and Tom Slater. You never type or think of the name of the hitting coach unless something is going terribly wrong. The assistant hitting coach doesn’t come up at all except when he’s coming or going, and then you type him only if you’re feeling diligent.

I don’t know what I’m feeling after 36 or so hours inside the Hugh Quattlebaum era. Hugh Quattlebaum and Kevin Howard are the new hitting and assistant hitting coaches, respectively. You’re not going to hear much about Kevin Howard even if things are going woefully because “Hugh Quattlebaum” takes up all the oxygen from a fun-to-say, fun-to-type standpoint. Hugh Quattlebaum is simply irresistible, and I apologize for not resisting. I often think back to a journalism class in college in which our teacher discouraged us from having too much pun fun with people’s names in headlines. They’ve been hearing it all their lives, he said, and he was right.

But we’ve had so little fun as Mets fans these last 36 hours.

No game Tuesday night.

No regulation nine-inning game Wednesday night (two Manfred-mandated partial affairs in St. Louis instead).

No deGrom.

No winning streak in progress.

No more Diesel Donnie Stevenson, probably, which is OK, because the further we get from the initial invocation of the fictional approach coach, Donnie seems less a whimsical clubhouse creation and more a desperate cry for organizational attention.

Nothing except splendid shortstop play and a deeply reassuring track record out of Francisco Lindor, the .163 wonder, as in “I wonder when Francisco Lindor will start hitting the ball.”

So does Hugh Quattlebaum. So does Chili Davis. Ditto for their assistants. Donnie the Six-Foot-Tall Rabbit, too. Everybody wants to know. Everybody might still have the assignments with which they entered the week had Lindor been hitting adequately rather than not at all.

This, too, shall pass, I’m certain of it. Fairly certain. Basically confident. Seriously, he’s not gonna be this way for the next 1,759 games of his contract, is he?

Also to pass: the residue of the Quattlebaum kerfuffle, wherein hitting coaches were replaced just as a bunch of the players they coached were swinging productively again — and nobody bothered telling the players before the front office told the world. Clumsily handled or otherwise, the midseason exchange of hitting coaches is a time-honored tradition for teams temporarily dipped beneath .500 featuring superstars wallowing a nautical mile below .200. Somebody’s gotta go, but offing the manager is too much of a bother. Pitching coaches occasionally get the axe, but hitting coaches are more obvious targets. Pitching can be subjective. Hitting is obvious. Not hitting is blatantly obvious.

Chili Davis used to be a fun name to say if not as much fun as Hugh Quattlebaum. Chili was hitting coach when the Mets hit loudly in 2019 and for three days this past Saturday to Monday. He was also hitting coach for the first few weeks of 2021 when the bats were so quiet Elmer Fudd could go wabbit-hunting. Chili did his best to communicate with his star pupils via video conferencing in 2020. His star pupils swore by him. After he was let go on Monday night, his starriest pupil, Pete Alonso, mourned his dismissal. Probably other Mets did, too.

Pete and the pupils will see their way clear to perseverance. Coaches come. Coaches go. Players stay until they come or go but rarely because of the movement of coaches. The Mets will implement through Hugh Quattlebaum (and Kevin Howard) whatever their precious prevailing philosophies are. That’s a big thing now. We praise teams for being analytically inclined. Get the players the information and help them put it to optimal use. Unless someone sees the ball and hits the ball, in which case we revel in good old-fashioned horsehide sense.

Fabulous results, however obtained, will make everybody happier. And whatever his skills as an instructor and disseminator, bandying about the name “Hugh Quattlebaum” couldn’t hurt the mood for a few days.

by Jason Fry on 4 May 2021 12:15 am So that was complicated.

The Mets’ Monday night game against the Cardinals didn’t look like a particularly good bet, not with old friend Adam Wainwright on the mound and Nolan Arenado and Paul DeJong lurking to do what they do. Not to mention the Mets put J.D. Davis on the IL and didn’t have Brandon Nimmo as a batter and decided to send Joey Lucchesi to the hill after flirting with the idea of reliever roulette.

And, ultimately, Lucchesi’s limitations were what cost them the game. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves, because it wasn’t that simple. The Mets got to Wainwright, scoring twice in the second and three times in the third, to claim leads of 2-1 and 5-2. And they did a lot of things the way you’d like to see them done: superlative fielding all around, particularly from Jeff McNeil; smart ABs and strong offensive games from McNeil, Pete Alonso and former Jace scapegoat Kevin Pillar; and sturdy bullpen work. The ninth-inning endgame was at least mildly nail-biting: Francisco Lindor and Alonso drew walks against fireballing closer Alex Reyes and Dom Smith gave no ground in a tough at-bat, flying to left on the seventh pitch and ending the game — a bad result, to be sure, but solid execution. (None of that was enough to save the jobs of hitting coach Chili Davis or his assistant Tom Slater; both were relieved of their duties afterwards.)

The fatal sequence came in the third. Lucchesi got the first two out, but yielded singles to Dylan Carlson and Paul Goldschmidt. Lucchesi fed Arenado a steady diet of hard fastballs inside and threw him a 1-2 curve which he swung over. Inning over? Nope. Before you could say “holy moly it hit the railing,” Arenado was insisting he’d tipped the pitch and home-plate ump Mark Carlson was agreeing with him.

Lucchesi’s next pitch wasn’t inside — it was a fastball up, right where Tomas Nido wanted it but also where Arenado wanted it, and he launched it into the seats. DeJong and Tyler O’Neill followed with doubles, Lucchesi’s night was done, and though we didn’t know it yet, so was the Mets’.

Carlson’s call of foul tip didn’t seem unjust, as Nido neither tagged Arenado nor protested after Carlson gave Arenado another life. The problem — as Todd Zeile pointed out in a useful postgame breakdown on SNY — was that Nido and Lucchesi went away from a game plan that was working to give Arenado a pitch he could handle.

It’s unfair to make too much of this — Lucchesi hadn’t thrown a pitch in anger for 12 days, what with the minor leagues yet to reboot. He’s an interesting pitcher, but one pretty clearly in search of something he’s yet to find, whether it’s a reliable third pitch, a role better suited to what he can do, or both. Fortunately, the Mets should be upgrading the rotation in short order, with Carlos Carrasco added to the mix. That should send Lucchesi to Syracuse, not by way of punishment but so the Mets can figure out what they have in him and what he might become.

But still. The Mets jumped on Wainwright and had a three-run lead in St. Louis. I didn’t think they’d win this one, but it was there for the taking and they gave it back. That happens, as do a lot of other maddening things if you watch baseball long enough. Or if you watch it at all.

by Jason Fry on 3 May 2021 1:18 pm The Mets won the damn thing, by a score of 8-7.

Those of you with enough years of scar tissue will remember that as channeling Bob Murphy’s judgment after the Mets held off the Phils at the Vet in the summer of 1990, with the last out a liner speared by momentary Met Mario Diaz on its way to the left-field turf.

I wonder what Murph would have done with replay review, challenges and other baseball modernities. Something wonderful, no doubt — if nothing else, the newfangled brace of delays would have given him more time to admire the few harmless puffy clouds overhead, or the genial tension of the spectators awaiting the verdict, or some aspect of the game that might have been shaded a few degrees to the positive but struck you immediately as the way things should be, and maybe inspired you to do your part to nudge them a little closer to the ideal.

On Sunday night we didn’t have Murph, alas — we had Matt Vasgersian and Alex Rodriguez on ESPN. Vasgersian isn’t a bad announcer by any means, but managed to be simultaneously bland and annoyingly overcaffeinated, and ought to be told it isn’t cute to be self-deprecating about not knowing the material. A-Rod is far more frustrating — an apt student of the game with a keen eye for analysis, but a bad habit of stepping on whatever point he tries to make by trying way too hard, slinging out jargon and cute turns of phrase until you realize you’ve been grinding your teeth for three innings. I wouldn’t think I could feel sorry for a genetic superman who’s a millionaire many times over, but A-Rod’s fundamental insecurity bleeds out through the microphone on nearly every call. I ran out of scoffs and shakes of my head and was left mostly thinking, This is sad. He needs therapy.

Sad would also describe the broadcast’s lost opportunities. A lifetime ago I was briefly ESPN’s ombudsman, a job I didn’t enjoy and hadn’t missed for a second until last night. ESPN had miked up Rhys Hoskins, and early in the game we got the usual nonsense you get from miked-up players — generic dugout rah-rah and dopey attempts at banter with enemy baserunners. Once the game took a sharp right into surrealism, though, Hoskins was squarely in the center of two pivotal plays — a misplay that let the Mets tie the game and a valiant attempt at a Phillie comeback that came down to agonizing replay review. Here were two genuinely interesting moments, both of them prime examples of Things You Don’t See Every Day in Baseball, and through great good luck ESPN had the guy in the middle of both of them wearing a microphone. Unless I missed something, we got nothing from either moment. What in the world is the point of asking a player to wear a microphone if you’re only going to use the boring stuff?

At least this time around there wasn’t much boring stuff: This was a wild game, more messy than majestic but one that certainly held your attention, from a frenetic opening inning to the Mets crawling away from the ninth blinking and covered in soot and dust yet somehow not only alive but also victorious.

David Peterson stumbled out of the gate, giving off a leadoff homer to Andrew McCutchen and putting runners on first and second with none out, but got bailed out by a nifty double play engineered by Jeff McNeil (whose defense has been superb of late) and Francisco Lindor. He then settled in, allowing the Mets to tie the game in the third on a Michael Conforto single off Zach Eflin.

For a while it looked like another of those frustrating games where the Mets’ offense went comatose — in the sixth, Jonathan Villar fanned in a startlingly horrible AB against Eflin with runners on the corners and none out. Next up was James McCann, competing with Lindor for the less-than-exalted status of Acquisition Fans Are Grumbling About Most. McCann smacked a grounder back to Eflin, who had a play at the plate or possibly an inning-ending double play behind him. He bobbled the ball — the Phillies were horrific with the glove all night — and threw it to the wrong guy at the second, getting nothing and allowing the Mets to take the lead.

Ahhh! Felt good, didn’t it? Well, at least it did for about six minutes before Miguel Castro gave up a three-run homer to Didi Gregorius, putting the Mets in the rear again, down 4-2.

They came back again. Kevin Pillar homered off Brandon Kintzler — the same Kevin Pillar, fairness requires me to note, whom I’ve been grooming as my 2021 scapegoat — and with one out and Villar on first, Jose Peraza (no longer a ghost!) hit a seething liner to Hoskins’ feet. It was a tough chance, but Hoskins was perfectly positioned to catch it and double off Villar, ending the inning. Instead the ball got through Hoskins, trickling past him and about 20 feet up the right-field line. Villar went to third and saw Hoskins glumly flip the retrieved ball to Nick Maton at second — so he kept right on going, scooting home while the Phillies were feeling sorry for themselves.

Tie game, and here came performative loudmouth Jose Alvarado, who’d been suspended for his tiff with Dominic Smith but appealed and so was still eligible for duty. (Smith was fined by MLB, apparently for the sin of being yelled at.) Alvarado should have taken the suspension — he gave up a single to McNeil, then walked Lindor and Conforto to hand the lead back to the Mets. Enter David Hale, whose first pitch was lashed up the right-field gap by Pete Alonso — 25 feet too low to be a home run but harder than a lot of balls the Polar Bear has sent screaming off into distant climes. It was 8-4 Mets, and I proudly told Twitter that the Phillies could eat shit.

Well sure, but I didn’t notice the teams were sharing a spoon. In the ninth, Luis Rojas decided to ask Edwin Diaz to finish up, causing me to groan on the sofa. Rojas was short-handed in the pen, but asking Diaz to protect a non-save situation doesn’t exactly have a glittering history of success. Diaz, on cue, walked Gregorius. He coaxed a pop-up from Maton, but Roman Quinn tripled to make it 8-5. Diaz fanned Odubel Herrera, but walked Matt Joyce and now in thousands of Met domiciles curious phenomena were being observed: pictures spinning wildly on walls, blood gushing from elevator doors across lobbies, bedridden children spraying pea-green vomit with their heads on backwards … bad stuff y’all.

Earlier, Villar had redeemed his lousy at-bat with a bit of heads-up baserunning; now, to my horror, the batter at the plate was Hoskins. Hoskins got a 2-1 pitch — 100 MPH but middle-middle — and hit it out. Tie game.

Except, wait, had it been out? Or had it hit the railing and caromed skyward? Hoskins received his congratulations — including a shout-out from the Phils’ social-media crew for his 100th career homer — and was standing contentedly in the dugout, but the umps were gathering.

Railing. Ground-rule double. Hoskins’ reaction wouldn’t have been shared with the ESPN audience even if the network hadn’t discarded the microphone thing. And the Mets still led, 8-7.

Exit Diaz and enter Jeurys Familia, which is whatever the opposite of reassuring is. And here came Bryce Harper. Except Harper had aggravated a wrist injury, and ended his last AB incapable of swinging the bat with any malice.

We’re Mets fans — we see things through a blue-and-orange lens, which is only logical. We were certain Harper would have some devil magic in him, or Familia would screw it up, or some combination of the two we wouldn’t care to parse. But that’s our lens, and it’s not the only one you can look through. The Phillie lens — the maroon one — was that the home team had spent the whole game playing like their mitts were on backwards, given up a tying run because they weren’t paying attention, led a head-case reliever blow the game, gotten either jobbed on a replay or suffered a correct but agonizing near-miss at glory, and now they were sending up a hitter who was in no shape to take an at-bat.

Seen through the maroon lens, they were doomed. And, on 2-2, Familia threw a sinker just off the outside corner of the plate. Harper struck out. They’d lost the damn thing, by a score of 8-7. How in the hell did we survive that? asked Mets fans, even as Phillies fans asked, How in the hell did we think that would end any other way?

by Greg Prince on 2 May 2021 2:22 am It may be too much to ask the Mets to play nine perfectly appetizing innings, so be grateful for the half-innings you don’t want to send back to the kitchen as underdone or overcooked. On Saturday, you could dine out on a three-course meal of them.

The Top of the 1st — Baserunners! Hits! Breaks! RUNS! FOUR OF THEM! Drinks! Music! Instead of moping over how they haven’t scored recently and therefore will never score again, our beloved Metsies scored four times to start their night at Citizens Bank Park. Pete Alonso drove in one that should’ve been two except his ball bounced over the fence. Michael Conforto drove in two instead of one when Andrew McCutchen let a sinking liner get by him. Things evened out for a change. Everybody between two-hitter Francisco Lindor and seven-hitter Dom Smith got on. James McCann McDampened the mood by grounding into an inning-ending double play, but c’mon, four runs in the first! How greedy should we be?

I would’ve preferred lots of greed. McCann’s GIDP gave me a bad feeling. We had Zack Wheeler on the ropes. I’ve seen enough of Wheeler to believe he’s a “get ’em early or you won’t get rid of him” pitcher. And he was. Zack gave up nothing to his old teammates and their new workplace proximity associates. Meanwhile, Taijuan Walker was “OK”. That’s in quotes because that’s how Walker himself put it. And he was very OK: 6 IP, 7 H, 4 ER, or exactly what Wheeler gave up over seven innings, except it looked better on Wheeler because Wheeler recovered to persevere from a four-run hole, whereas Walker allowed a four-run lead to melt into a 4-4 tie.

The Bottom of the 7th — Aaron Loup is pitching. With one out, he walks McCutchen. Matt Joyce grounds to Lindor the shortstop who’s playing extra second base or whatever one would term positions that didn’t exist before clever shifting wrecked standard defensive diagrams. However it’s labeled, Joyce’s grounder shapes up as perhaps a double play ball or at least a simple putout at first. Lindor takes the ambitious route, chasing down McCutchen to no apparent avail before rushing a throw to first to try to nab Joyce.

Does that sound like it ended the inning? Well, it did. Lindor’s wily aggressiveness must have spooked the hell out of second base umpire Jose Navas, because he ruled McCutchen had run astray from the baseline and was out despite not being tagged or forced. Replays showed pretty convincingly that McCutchen stayed on the straight and narrow in his path to the bag and in no way should have been ruled out. Meanwhile, Joyce, who was initially called safe by Andy Fletcher — another umpire who must’ve been glued to his phone despite being at a baseball game — was actually out. Lindor knew it right away (he jogged off the field despite two Phillie runners briefly seeming to have legitimate claims to their bases) and an official second look confirmed it.

That was strange. Probably as strange as Conforto’s elbow getting in the way of a strike a few weeks ago and being told he could go to first base with a walkoff RBI. But no stranger than the Mets losing their three previous games by scores of 2-1, 1-0 and 2-1, the middle of them with deGrom on the mound and the last of them because a strikeout morphed into two opposition runs. So, again, breaks!

We didn’t necessarily order them, but we’ll take them if they’re compliments of the fates.

The Top of the 9th — Conforto goes deep to give the Mets a 5-4 lead. It’s about frigging time any Met hit any home runs at Citizens Bank Band Box. It’s where they usually spank the ball until it screams that it’s learned its lesson and it will get over the wall ASAP. This was their fifth game of 2021 in Philadelphia, yet only their second homer there. Nice time to get sluggy, Michael.

Dessert is included with our three-course meal. You really had to try the Mussless, Fussless Bottom of the 9th, assuming you had no dietary restrictions. It’s made with a revamped blend of Sugar, which tastes surprisingly sweet these days.

Edwin Diaz indeed closed out the 5-4 win. It was indeed a 5-4 win. The Mets seemed determined to blow this game, but maybe a touch more determined not to. As a result, they own a share of first place in the National League East, which doesn’t mean much because a) it’s very early May; and b) they and their co-frontrunners are under .500; yet c) it’s better than a share of last place. Plus, nobody pretended they were about to throw hands.

If you require a little acid reflux, seeing as how you can’t possibly be used to digesting good Met news, Mets are sort of dropping like flies. Sort of. Luis Guillorme’s IL stint stemmed from himself taking BP Friday. Brandon Nimmo and J.D. Davis had to exit Saturday’s game in tandem from hand and finger things that reportedly didn’t kill them (so maybe it will make them stronger). There was also that business about nearly blowing the game, partly because Walker was only OK and partly because Wheeler wouldn’t let them score after the first.

But they didn’t blow it. “OK” from the starter led to A-OK from the bullpen, with Loup, Trevor May and Diaz continuing to not let games get away, an increasingly standard accomplishment we don’t dare take as the norm but it kind of is lately. We got 80% of our runs in a batch at the beginning and the final 20% via one powerful stroke toward the end. We surely got our breaks (sorry, Cutch). We even have a newly hired hitting consultant named Donnie Stevenson, if Alonso’s and Conforto’s postgame description of their approach coach is to be believed. I assume he was brought on board by special assistant to the GM Jonathan Tuttle.

Tuttle? Why, I just had dinner with the man!

by Jason Fry on 1 May 2021 2:13 am The Mets lost and it was excruciating on so many levels.

They weren’t even playing the Phillies, really; rather, they were playing the lesser half of the Phillies, shorn of Bryce Harper and Didi Gregorius and J.T. Realmuto and Jean Segura. It didn’t matter. They probably would have lost to a bunch of Norristown tykes who barely topped four feet and were wearing blue jeans below t-shirts that said PHILLIES and had a local deli’s name on the back.

Mets pitchers gave up a grand total of two runs. Those runs scored, unbelievably, on a strikeout with two outs. A strikeout of the opposing pitcher. You cannot make this shit up.

You’d like to be making up the report that Marcus Stroman — wonderful after his bobble last time around — departed early because of a tight hamstring. But that was all too real — Steve Cohen himself said so, and I figure he ought to know.

A game that was already a farce degenerated further in the eighth, when the Phillies put on a show of performative high dudgeon about perceived Met misdeeds. First came Jose Alvarado, who found the plate in the nick of time to fan Dom Smith on pretty much the only good pitch he’d made all inning. Alvarado wasn’t happy a little while ago when Smith wasn’t happy about Alvarado hitting Michael Conforto; having struck Smith out, he struttingly invited the defeated Met to talk about their differences, causing the benches to empty and mill about and the bullpens to rush in, not that bullpens actually rush — they more huff and puff dutifully but unhappily about the whole thing. To the disgust of Ron Darling, the Mets didn’t start throwing haymakers; I thought that was less choosing pacifism than being baffled about the whole thing. Why would anyone try to wake up an opponent already so thoroughly asleep that you’re tempted to hold a mirror up to the batters’ mouths?

An inning later, Miguel Castro came inside to Rhys Hoskins with a pair of pitches. I doubt they were meant to hit anyone — they looked like sinkers that didn’t sink — but Hoskins, whom we’ve seen be touchy before, took loud exception. Cue more emptying, milling and dutiful reliever huffing and puffing, at which point I suggested the two bullpens simply brawl in the outfield to save each other the time and exertion. Nothing happened, largely because Francisco Lindor practically draped himself over Castro, keeping him out of further trouble — Lindor’s leadership remains All-Star quality even as his bat is stuck below replacement level. Somehow I found myself missing Larry Bowa. By that point Bowa would have stripped naked, lit himself on fire and become a superheated meteor of chaos racing around the field combusting everything within range; what we got instead was a bunch of posturing and chippiness that was both embarrassingly shrill and deeply stupid.

And beneath all that, there was something worse: Friday night’s game was another very 2021 ballgame, which is to say it was very long and very boring. The Mets and Phillies combined for three runs and nine hits, which isn’t much but somehow took three hours and twenty minutes. I’ve said before that I don’t like gimmicks like the three-batter rule or ghost runners, to say nothing of tinkering with 60 feet, six inches, but there are too many unwatchable games these days. Something has to change, not for the young future generations that baseball’s deeply concerned about unless it involves scheduling postseason games that generation can actually stay up to watch, but for old generations like mine, fans who love baseball but find it increasingly clunky and slothful and deeply dull.

After the game’s merciful death rattle, Darling grimly said the Mets needed to view Friday night as rock bottom, put April behind them and come out firing in May. Which would be nice. But I’ve watched my share of fundamentally bad teams, teams in danger of mistaking buzzards’ luck for their own character, and teams that will be OK once they stop getting in their own way. I don’t know which category the 2021 Mets belong in, not yet, but I have learned this much: There’s no surer way to make yourself miserable than to declare a certain debacle is rock bottom. All too often, you’ve got plenty of falling left.

|

|