The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 2 July 2017 4:18 pm Some things you have might have missed in Sunday’s oft-snoozy, quietly weird, ultimately dispiriting loss to the Phillies:

- Rafael Montero wasn’t that bad. Yes, the wheels fell off in the second inning for Montero, who has a history of winding up standing forlornly by the side of the road waiting for a wrecker. But Montero was undone primarily by his defense — not in an obvious, what-the-hell-was-that way but in a quieter, that-play-would-have-been-nice-t0-see-made way. For example, you can’t get on Brandon Nimmo for not running down Maikel Franco‘s double that brought in the first two Phillie runs — the ball was off the wall in left-center, and Nimmo belongs in a corner outfield spot. Still, the ball was in the air for a long time, long enough for a better defender to reach. The third run came in on a ball essentially through Asdrubal Cabrera — forgivable since the infield was playing in, but still a play not made. And the fourth run came in on a farcical two-base wild pitch that Rene Rivera simply couldn’t find, a catcher’s nightmare that was a dream come true for surprisingly speedy fellow backstop Andrew Knapp. It sounds like damning with faint praise, but that inning aside Montero was pretty good — aggressive and efficient where he’s often failed to be either.

- It’s piling on, but the other three runs were also the product of poor defense: Chasen Bradford went to sleep and failed to cover first on an infield roller and Jose Reyes looked immobile on a ball up the middle. Blecchs all around.

- Meanwhile — stop me if you’ve heard this one before — youngster Nick Pivetta rebounded from a terrible start to stymie the Mets, riding a mid-90s fastball and mixing in a sharp slider to keep them off-balance except for a line-drive homer from T.J. Rivera. But he tired in the seventh, walking Jay Bruce to lead off the inning and facing Lucas Duda. The Phils’ bullpen wasn’t ready, and if ever you had a good feeling about being down three runs with one hit on your ledger, it was now. Duda popped a ball up to short center that had trouble written all over it — and, indeed, it popped out of Aaron Altherr‘s glove. Except it then hit Altherr in the shoulder, rolled obligingly down his arm and plopped into his glove behind his back for a crusher of a double play. Sometimes the baseball gods aren’t subtle in signaling that it’s not going to be your day.

- Another oddity: the Mets and Phils inflicted a double challenge on their fans. The Phils challenged an apparent 6-4-3 double play, contending that Franco was safe at first. The Mets waited around for the umps to agree, then argued that Nick Williams had roll-blocked Cabrera on the pivot, which should restore the double play. They didn’t win either challenge. Oh the majesty of replay!

You can’t win ’em all, as a philosopher once said. Sometimes that conclusion emerges from an agonizing reversal, a horrific mischance or something unforeseen. And other times everything warns you that’s what the verdict will be.

by Jason Fry on 2 July 2017 12:28 am So the Mets played an amazing game Saturday afternoon, with Asdrubal Cabrera hitting the go-ahead home run on the same day fans took home a bobblehead of him connecting for a walkoff home run against the same team last year, and —

Wait a second. I’m afraid this post has been flagged for review. Because what you’ve written is absurd.

How so?

Jeez, where do I start? How about the cheap theatrics? A guy hitting a go-ahead homer on the same day a giveaway is celebrating what’s pretty much the same thing?

But … that’s what happened! I swear it!

Look, you even have him hitting it against the same team. You’re the one who’s always talking about narratives, right? Can’t you be a little more subtle? More artful?

Look, I’m just the chronicler … the narrator, if you will. I don’t come up with the story myself — I just pass it along and try to give the retelling some structure. If I could determine the outcome of these things, we’d be gunning for the 13th World Series title of the Faith & Fear era.

Did you actually see this miraculous home run?

Well … no.

That doesn’t sound like very good chronicling to me.

I know. But let me explain. See, I’m in Connecticut at my in-laws for the holiday, and the game was taking forever, and we had dinner guests, and the Mets had just fallen behind 6-3 on this tremendous home run by Aaron Altherr —

Was it his Bobblehead Day too?

Of course not.

Wait, I had my people review this. It was Tommy Joseph who hit the homer.

Tommy Joseph then. Anyway, it had been a frustrating game, and I kind of figured that was it, and anyway there was this huge bow wave of thunderstorms steaming from the west towards New York, so I knew there would be a rain delay. So I told myself I should go upstairs and be sociable, and I could discreetly check what happened on my phone and maybe slip back downstairs after the rain delay and hope for the best.

So the first time I check my phone the score I’m seeing doesn’t make sense: Mets 7, Phillies 6. That was pretty exciting, so I kept checking, and sneaked off during the rain delay to watch a replay of the Cabrera home run.

The one just like the one last year, you mean?

Yeah. I mean, it was uncanny — it was 20 feet or so to the left of last year’s, but about the same distance. Though of course Asdrubal didn’t punctuate events with an epic bat flip this time, seeing how this time the game wasn’t over.

See, that’s what I mean about subtlety and art. It would be more effective if this second home run of yours were hit to the other field, or clanged off the foul pole.

I suppose, but that’s where it went. And it wasn’t even the first bit of weird parallelism in this game.

Go on.

Well, Zack Wheeler started for the Mets, and he … well, he was Zack Wheeler.

That’s not very descriptive. How will your audience know what that means?

Believe me, they’ll know. It means he was really good — fastball hitting 98, sharp slider as an out pitch — but he was also really inefficient. Like it took him 40 pitches to get through the first two innings. But even then, he might have qualified for the win if not for this unlucky, unfortunate play in the fourth.

With one out T.J. Rivera committed an error at third and then Wheeler walked the next two guys — he wasn’t helped by a really small strike zone — which brought old friend Ty Kelly to the plate. Kelly’s an interesting player and I wish the Mets hadn’t lost him — he can work a count and has good instincts, though he always looks weirdly diffident at the plate, like he’s peeking around the bat. Anyway, Kelly worked the count full and then hit a grounder to Lucas Duda at first.

Duda — who had a really good day at bat and in the field, by the way — snagged it and threw to second for the second out, with Wheeler covering first for the return throw. But Zack took his eye off the ball to check where his foot was and the ball clanked off his glove. So instead of an inning-ending double play and Wheeler having the chance to come out for the fifth with a lead, the Phils had scored two and Terry Collins took Wheeler out.

OK, now I’m listening. That’s the kind of detail you want to make this narrative of yours engaging.

I’m glad you like it. But look, we haven’t gotten to the weird part yet. The Mets tied it up in the bottom of the fourth and then took a one-run lead on a Duda home run into the apple’s housing — I think they ought to call it the apple core, but nobody listens to me — but then the Phils tied it again in the top of the fifth after a two-out walk to Altherr and a throwing error and a Tommy Joseph double–

None of that sounds weird, just really sloppy. Plus you should throw some more protagonists and antagonists in the story, instead of just using Duda, Joseph and Altherr.

Hey, I chronicle what they give me. You’re right that it wasn’t exactly a baseball showcase. But here’s the weird part. In the bottom of the fifth Cabrera came up with the bases loaded —

The home-run guy? Can’t you use somebody else there?

I keep telling you that’s not how it works. Cabrera came up with the bases loaded and one out and smacked a grounder to Joseph at first, who threw to the shortstop and then back to Jeremy Hellickson, the Philadelphia pitcher, covering first. Hellickson took his eye off the ball to check where his foot was, and —

Let me guess, the ball clanked off his glove.

Nope. He caught it, no muss no fuss, and the Mets were turned aside. It was the exact same play where things went wrong for Wheeler — the two pitchers moved their gloves the exact same way, looked down the exact same way, were short of the bag and had to reposition a foot the exact same way. Except one guy caught the ball and the other guy didn’t.

Well, that’s not exactly parallelism, is it? Why do we need that detail?

Because it’s a reminder of how baseball turns on little things, and those little things are often somewhere between capricious and cruel. I think that’s something we need to keep in mind as fans — how thin the line is between success and failure.

All right, noted. So it seems like we’re up to the home runs you were telling me about — the one by this Joseph guy and the one by your pal Cabrera. What happened after that?

Well, there was the rain delay, and then Addison Reed was called on for a four-out save.

And did he get it?

Would you let me tell the story? He did, but it wasn’t easy. Altherr led off the ninth with a double — one that hit off the freaking orange line just above Jay Bruce‘s head.

Yikes! That’s dramatic! But once again, c’mon. Altherr again?

Sorry, but it was him. Leadoff double, but Reed held the line: flyout to center, grounder to first that moved Altherr to third, pop-up to right and the Mets had won.

Hmm. Well, that’s a feel-good ending.

It was! I wish they all were, but this one definitely was. Oh, and there’s one more thing I want to include. After the storm rolled through, there was a rainbow over Citi Field. It was beautiful.

That’s ham-handed — we really need to talk about subtlety in these write-ups of yours — but I agree that’s beautiful. So look, I still think you need a bigger cast of characters and a little lighter hand with the parallelism — the matching home runs and the two double plays and stuff like that. But this is good material and an OK first draft. So work on it some more and we’ll see…

Oh wait, it was a double rainbow.

You’re killing me here. Fine, write whatever you want.

I will! That was the game that brought the Mets to within four games of .500, and started their long climb back to the playoffs and then —

Let’s not go crazy.

Fine. I’ll settle for the nutty home run and how much fun it all was. But the double rainbow stays.

by Greg Prince on 1 July 2017 11:00 am Some games words filter into your brain. The word of the night Friday was “taut,” as in nice and tight, the way you’d figure someone who intermittently devotes himself to baseball as something of an academic discipline would like it. Give a student of the game a 2-1 affair won by his favorite team and played in 2:38, the student will grade it generously.

This one certainly did. I attended Friday’s game in tow with the Society of American Baseball Research. SABR’s annual convention is in New York this summer. It’s like fleet week, except instead of naval uniforms everywhere you go, you’re surrounded by men in vaguely ironic Ebbets Field Flannels purchases, at least in the vicinity of the Grand Hyatt. Most of the SABR buzz is over on the East Side, but every year they take in a ballgame in their host city, and this year the venue was Citi Field. It was my first national SABR event, a worthwhile expansion of my usual membership activity, which is generally confined to accessing the Sporting News archives as needed and skimming the weekly e-mail newsletter.

Lest you infer SABR has rigorous admission standards, it works like this: you sign up, you pay a reasonable amount in annual dues and you’re in. I recommend joining if you are intrigued by any of the facets that constitute baseball — and I’m gonna guess you are, given your choice of reading material at this very moment.

The first part of SABR Day at Citi Field commenced at 3 o’clock. This was the ballpark session, the only one I committed to. It entailed showing up at Citi at an hour when somebody stationed by a glass door usually tells you to get lost until later. My expectations were tempered by experience; first national SABR event, perhaps, but 238th regular-season game at Citi Field. Surprisingly, somebody in Flushing actually told somebody else to let us in. We flashed our lanyards at the Stengel entrance, subjected ourselves to the standard security search (lest someone be smuggling inside his backpack a lethal tract on 19th-century bunting) and were directed ever upward to Excelsior. We seated ourselves in the outer left field sections. Scanning of tickets and distribution of Free Shirt Friday apparel would wait.

The Mets furnished a splendid lineup of speakers, though the first one didn’t show. Terry Collins was going to talk to us, but we were told he couldn’t make it. I fantasized he was too busy unconditionally releasing Neil Ramirez, but maybe he was just too tired from the previous night’s late flight from Miami. Pinch-hitting for Terry (we SABR types love to use baseball terms) was Tom Goodwin, who you’ll recognize from those commercials with Curtis Granderson and myriad pats on the butt administered to runners at first.

Goodwin was solid. Coaches are good listens since it’s relatively unusual to hear from them. They’ll talk baseball nuts and bolts with passion. Tim Teufel did that at QBC this winter. Goodwin did it at SABR, except without the winks about what it was really like on the ’86 Mets. “Goody,” as he seems to be known internally, also reminded us David Wright a) still exists; b) is working hard; c) is missed. When Tom was moved to recall how well the lineup clicked down the stretch in 2015 with David batting second between Curtis and Yoenis Cespedes, I was shocked to realize that all that was less than two years ago.

In general — perhaps for positive reinforcement, perhaps for context, given how many of the attendees were from out of town and not walking around day and night conscious of every move the Mets make, every breath the Mets take — “2015” was mentioned an awful lot. I remember “1969” being mentioned an awful lot deep into the 1970s, as if to say “you know, we won something once, we might win something again.” Two years ago may or may not be a long time. I’ll have to do some baseball research on that.

The next talk was conducted by three Mets broadcasters: Wayne Randazzo (with a mic so faulty that the jets overhead couldn’t hear themselves roar), Steve Gelbs and Josh Lewin. Each of them was terrific. Josh introduced himself and added for those who didn’t already know, “Howie Rose is my spirit animal.” This is why we love Josh Lewin. I like Gelbs and Randazzo quite a bit, too, two young-ish men who have really grown over the last few seasons. (You can tell I’m edging into the prime SABR demographic when I use that kind of senior-discount language.) They all attested to the intense nature of the New York market, where people like us will point out instantly that uh, maybe what you said on the air wasn’t what you meant to say, here’s what you should’ve said. Wayne is from and has worked in Chicago and said there’s no comparison. Steve noted that on the Mets’ recent trip to Phoenix, there were two people at Chip Hale’s press briefing, “and one of them was Chip Hale.” They all embrace our market, though, and I embrace that they’re here.

At four, the announcers hustled downstairs to Collins’s presser — where there were more than two people and Neil Ramirez’s unconditional release was not announced — and Sandy Alderson took center stage. Seven seasons in, Sandy has reached that Terry stage of I can’t imagine anybody else in his role. A little success (did you know the Mets played in the 2015 World Series?) goes a long way, even in hard, unforgiving New York. Alderson always conducts good Q&A. He doesn’t necessarily tell you all you want to know, but he never doesn’t answer a question. Baseball people love the act of talking baseball, Sandy as much as anybody. It’s not state secrets or classified corporate intelligence. It’s putting the best nine guys on the field. Why not talk it up?

Tim Tebow came up. It wouldn’t have occurred to me to ask, but somebody did. I think Tim Tebow was signed by the Mets so there’s always be something to talk about (perhaps that’s why there are injuries, too). Sandy’s explanation of Tebow was the human embodiment of a shrug emoji. He’s famous, baseball’s entertainment…shrug. There was a delightful nugget thrown in about how if you turn to Tebow’s entry in the 2017 media guide, you’ll see the signing scout listed is James Benesh. James Benesh handles merchandising.

This is hilarious if you’re at a SABR meeting. Sandy knows his audience. He also mentioned calling the Braves and inquiring about Bartolo Colon. Well, their excess Bartolo Colon bobbleheads. (Also hilarious.) Sandy didn’t counter Goody’s portrait of David Wright as salt of the earth, but didn’t sound the least bit optimistic that he’d be playing baseball for the Mets this year. He couldn’t say whether Colon would be and didn’t go any further on projecting Tebow’s short-term future besides suggesting tickets for St. Lucie Mets games are now on sale.

Hard to follow Sandy Alderson into the spotlight, but there was one more group up for the challenge, consisting of assistant hitting coach Pat Roessler and analytics aces T.J. Barra and Joe Lefkowitz. Did you know the Mets send somebody from their analytics staff on every road trip so as to apply data to action? Or that players will nowadays ask to see data to support their coaches’ assertions on how they should approach an outside pitch? I didn’t until these fellas shared those tidbits.

We got two fine hours of SABR-catering, then our tickets scanned in a sane matter (they did it on Excelsior), then not one but two Free Shirt Friday shirts (Cespedes plus some Reyes overstock that perhaps the Braves would be interested in; Roessler was wearing one), then two hours to mingle. I got to meet if not my spirit animal then my fellow USF Bull Dirk Lammers, keeper of nonohitters.com and author of a book exploring all of Baseball’s No-Hit Wonders. Dirk and I were editors on our college paper in adjacent decades and are lifelong Mets fans. It was like we’ve known each forever. SABR will bring types like us together.

Then, if you registered for their convention in an ad hoc manner as I did, SABR will keep you apart during the taut game to follow. While Dirk, his lovely wife and others I either already knew well or was just getting to know were sitting over in Section 140, I was ensconced in Section 142. It was random, but it was all right. Those sections are the Big Apple seats or the Apple Orchard or perhaps sponsored by a hard cider purveyor. I’ve only recently gotten out of the habit of calling Excelsior the Caesars Club. You usually notice this center field seating area when The 7 Line Army takes over. They wave thunder sticks and make noise that would drown out Wayne Randazzo’s faulty mic. We paged through our 19th-century bunting tracts. Nah, that’s not true, but a national SABR gathering will be non-denominational, or at least catholic with a small ‘c’ in its alignment. Some Mets fans, but also some Phillies fans, a Dodger fan who once read Cespedes bounces around so much “because he’s a clubhouse lawyer,” and folks from all over with allegiances to match. Dirk’s from New Jersey but lives in South Dakota now.

I spent most of the nine innings with Howie and Josh in my ears. They convinced me (along with my eyes from 420 or so feet away) that Jacob deGrom was perhaps crafting something special. They made me believe a new chapter to Dirk’s book was possible Friday night. Curtis Granderson, whom Goodwin really likes and not just in commercials, put an end to that. As horrifying as it was, it was fascinating to watch from just beyond the center field fence the center fielder not catch a catchable ball. I’ve trained myself to watch the fielder, not the ball, but that’s usually from seats in foul territory. Here I was behind Curtis, so when I saw Andrew Knapp’s fifth-inning fly ball soar, I watched Curtis. OK, Curtis has got it…wait, why isn’t Curtis catching it? It was because Curtis didn’t got, er, get it. He misjudged it in a sky where, to be honest, I lost track of it immediately.

Knapp’s harmless fly fell in for a spiteful triple, which became the first hit deGrom gave up. It became a run when Jacob gave up a second hit, to former local sensation Ty Kelly. The only positive, besides not driving myself crazy with superstition for the next four innings (I wouldn’t have eventually grabbed a seat near Dirk & Co. if a zero was still in play under the hit column), was noticing Cespedes come over and give Curtis a consoling Goodwin-type pat on the butt. Not a clubhouse lawyer move, but the mark of a good teammate, I assume.

Otherwise, ouch. But not too bad an ouch, because the Mets took early advantage of Ben Lively’s early lack of tautness to post two runs. Should’ve been more, but they turned out to be enough. In center, I could hear Jose’s fourth-inning triple, both the ball and Odubel Herrera slam off the fence. (I could also hear every reliever thump the ball into his catcher’s mitt. Even Neil Ramirez sounded devastating.) I thought the Mets would take Lively apart, but he lived until the seventh. DeGrom, meanwhile, was barely bothered by the Phillies after the Grandy snafu, striking out twelve and allowing only one other hit. He and Lively dueled as pitchers used to, though not for as long as pitchers used to. Surely there’s some SABR research on that.

Relievers not named Ramirez took over and kept the game nice and tight until it ended 2-1 in 2:38, a metric I harp on because I figured it would allow me to make the 10:19 at Woodside. And it did, even though I walked much more slowly than usual to the 7 Super Express in deference to my new out-of-town pals who hadn’t been informed of how we step lively after we’ve stepped all over Lively, especially when catching a train is at stake.

They’ll learn. SABR teaches you plenty.

by Jason Fry on 30 June 2017 10:14 am The Mets don’t lead the league in much, but they’re at least a wild-card contender in keeping us guessing, having concluded their road trip with a Rorschach record of 5-5.

That’s five to go in the They Rebounded From Getting Blitzed and Got Themselves Together on the Road So There’s Hope column (you may label this one differently, of course), and five to go in the They Got the Stuffing Beat Out of Them and Didn’t Even Look Like a Big-League Team column. Which adds up to a collective shrug and a quick turnaround to Citi Field, where the Phillies await.

Before leaving Miami at an absurdly late hour, the Mets had one final game to play against the Marlins. It was an odd one — a stop-start affair that felt like three different games grafted together. First came the laugher, with Jay Bruce and T.J. Rivera beating up on Jose Urena. Then came a long, draggy stretch in which everything took forever. And finally we got a spasm of worry, as the Marlins staged a two-out rally that would ultimately just be a bunch of noise.

All of that is storytelling, of course — the construction of a narrative around individual pitches and plays. This is how we get ourselves in trouble as amateur baseball analysts, ferreting out imaginary patterns and attributing random events to grit, heart, morality and fate. Still, it’s irresistible — we’re wired for storytelling and use it for everything from describing a mundane day of work/school to secondhand accounts of athletic contests. And since we’re so wired, most baseball games sort themselves easily and readily into premade narrative buckets.

That sounds like a post to be considered with greater leisure during the offseason, but you know what I mean: there’s the Laugher, the Coach Not Taking Us to Tastee-Freez After This Mess, the One Where You Were Out of It After One Pitch, the Thrilling Comeback, the Fizzled Comeback, the Horrible Tortoise-and-the-Hare Loss, the Heart Ripped Out Day of Infamy, the Moral Victory But Still a Loss, the Philosophical Conundrum of Tying It in the Ninth Just to Lose in 12, the All-Time Classic, the One You Knew You Were Going to Lose One Way or Another Eventually, and so on. Last night’s wasn’t any of those — it feinted in various directions but never really settled on any of them.

Sometimes a baseball game’s just a baseball game, I suppose.

Like any baseball game — or at least any win — it had its pleasures. There was watching Seth Lugo as the antithesis of Rafael Montero, pitching efficiently and aggressively to Giancarlo Stanton & Co. and being rewarded for it, as the reconstituted Mets infield turned two more double plays on the night. There was the instinctively terrific defense of JT Riddle, a young shortstop who looks like he’ll be the next Marlin to make us grind our teeth in helpless agony. There was the big triple by the generically handsome Matt Reynolds — described perfectly by one Twitter wag as looking “like one of the teammates with no lines in a baseball movie” — that would push the Marlins back to a more comfortable distance.

Not a particularly memorable baseball game, but one that was just fine for a warm June night. And perhaps that’s its own narrative bucket.

by Greg Prince on 29 June 2017 9:17 am Don’t remind Ray Ramirez that Curtis Granderson is still out there, still playing, still hitting, still in one piece. Ramirez, or our conception of Ramirez as grim reaper of Met body parts, eventually gets everybody. He doesn’t get Granderson, though. Three-and-a-half years into a four-year contract, Grandy stands on two feet that he puts one in front of the other on his way to the outfield pretty much on a daily basis. If he isn’t starting, he is available to pinch-hit. You can’t always tell it from his throws, but his arms work, too. They can swing a bat and lately do to great effect. The parts between the limbs stay intact. The head is surely screwed on right.

Pending whatever damage I’ve done by deigning to mention his thus far indestructible durability, Curtis Granderson does not go down as New York Mets typically do. Not from Ramirez’s soul-harvesting alchemy, not from the ravages of time siccing themselves on a 14-season veteran, not from stubbornly torpid springs when his batting average wouldn’t qualify for welterweight competition. He was slashing .122/.175/.211 after two games in May. He has elevated to .235/.327/.473 with two games left in June. Grandy is up, and he is at ’em, and — when enough of his teammates meet him at the cross streets of Capable and Competent — he is helping the Mets win some games.

Curtis did that on Wednesday night in Miami. He helped the Mets immediately by not departing the batter’s box so quickly. Grandy lingered purposefully for nine pitches until working a walk from Jeff Locke. Nobody ever looks as satisfied by a base on balls as Granderson. You can feel him thinking, “I get to go to first now. This could be useful in so many ways.” He long ago deduced that a walk can be as good as a hit. For all we know, he might have been the one to have coined the expression.

How good was the walk Granderson took from Locke? Good enough to be exchanged for a run when Asdrubal Cabrera, hitting directly behind him, belted a ball out of sight to give Steven Matz a 2-0 lead that would grow into an 8-0 win. Matz nurtured his advantage for seven smooth innings. Jose Reyes, finally passing Ed Kranepool for second near the head of the all-time Mets hit parade (I would have preferred the leapfrogging take place in 2012), contributed two singles and a double. Brandon Nimmo was Le Grand Wyomingan, adding a couple of RBIs off the bench. And Grandy, who walked to first in the first, went deep to right in the seventh. It was his twelfth home run of the year, his eighth home run of the month, his fifth home run of the current road trip. He also long ago deduced that a homer is four times as good a walk.

Curtis got the Mets going the night before last with a leadoff home run. That the Mets didn’t keep going wasn’t his doing. He can’t always wrangle a minyan of Mets and lead them toward a happy recap. One Met can do only so much. Curtis has, however, done one thing remarkable on a remarkably consistent basis since becoming a Met in 2014, something nobody else in a Mets uniform has done in ages.

He stays active. Active in the baseball sense, not active in the “…and he takes Geritol” sense. Maybe he does take Geritol or calcium supplements or some other elixir that counteracts the effects of aging. In real life, Curtis is a young man of 36. In baseball terms, we call that old. When Curtis is in a funk, which usually coincides with months beginning with “A” and ending in “L,” we call him old. When Curtis unfunks, we see experience and don’t notice how long it took to compile it. Curtis doesn’t look any particular age these days. He just looks good.

More important, we don’t have to comb a chart other than the 25-man roster to find him. Four seasons, no DL. Now I understand merely writing the preceding sentence is the moral equivalent of tempting the wrath of the whatever from high atop the thing. Don’t worry, I’m going outside, turning around three times and spitting to ward off Ray Ramirez’s evil spirits as soon as I post. Superstition ain’t the way, except in baseball and a few other endeavors, but definitely baseball.

Nevertheless, I really do have to share a little insight I’ve gained through my Mets-fan compulsiveness. For many years, I’ve maintained a chart of every Met, which at the moment measures Richie Ashburn to Chase Bradford. It encompasses three vital statistics for each fellow to have worn the orange and blue in what Art Howe would call battle: when he was born; when he debuted as a Met; and when he played his last game as a Met. The last column is tricky for those still in our immediate midst, so I’ve developed a policy. At the beginning of a season, I mark as last game played the first game a player entered in the new year. If he goes on the disabled list, is sent to the minors or is otherwise provisionally removed from the 25-man roster (bereavement, family leave, suspension), I list his most recent game played as his last game played. Upon return, his first game back becomes his new “last game” and stays as such unless circumstances dictate otherwise. Vegas-shuttlers like Matt Reynolds and Rafael Montero have played a slew of last games this year. Once the season is over, when not staring out the window alongside Rogers Hornsby, I update the list with everybody’s most recent game as their last game. Winter bestows finality, no matter how temporary.

Richie Ashburn’s last game as a Met was 09/30/1962. That won’t change. Ed Kranepool’s last game (featuring his 1,418th and final hit) was 09/30/1979. That also won’t change, though if Tim Tebow can make it to Port St. Lucie, we shouldn’t rule anybody out. Robert Gsellman’s last game as a Met was 06/27/2017. Knock wood, that will change, but once Ray Ramirez got his hands on Robert’s left hamstring, Gsellman’s info required revision. Same for Neil Walker (06/14/2017) when he was assigned to the DL, same for Noah Syndergaard (04/30/2017), same for Jeurys Familia (05/10/2017), same for Tommy Milone, even (05/21/2017). When/if they come back, their next game will become their “last game”.

Curtis Granderson defies this granular level of bookkeeping. For Curtis, I type the date of Opening Day in the last-game column and I leave it until Closing Day because he stays. He doesn’t fall away in the fashion of his inevitably Ramirezized colleagues. Once, in his first year as a Met, he had to sit for a few games with some ache or pain, and I reflexively changed his “last game” notation. I just assumed he, à la every modern Met, was about to be officially disabled. Nope, he just needed a few days and then he was good to go.

The good going has continued uninterrupted ever since. There are gaps in Grandy’s production, but not his presence. You can’t say that about everybody. Actually, you can hardly say that about anybody. It’s to be admired when you see it, seeing as how you don’t see it all that much.

I spent twenty-some minutes talking about my book Piazza with Chris McShane for Amazin’ Avenue Audio. I hope you’ll listen in here.

by Jason Fry on 28 June 2017 11:04 am Thank goodness for Monday’s off-day, for it gave us another 24 hours to test the limits of mathematical optimism. Once the Mets were no longer playing the 2017 Giants, our dreams of seeing them ascend to contention were revealed for what they were and the audacity of hope crashed headfirst into the inevitability of nope. And, for approximately the 6,893,355th time since 1993, the wake-up call came from a not-good-but-better-than-us Marlins team in a near-empty stadium in Miami.

There was no shortage of things terrible and typical Tuesday night — mush-brained at-bats, poor fielding, inept relief, bad luck and ill health — but one sequence summed it up. To set the stage, in the top of the seventh the Mets had tied the game on a Travis d’Arnaud homer but saw a rally snuffed out thanks to a nifty, improvised play behind second base by new Marlins annoyance JT Riddle.

In the bottom of the inning came a flurry of mistakes that would prove fatal:

- The Mets continued to allow Neil Ramirez near a big-league roster, then compounded that bizarre decision by letting him pitch in a situation that mattered. Ramirez’s first act, predictably, was to walk JT Realmuto.

- Up came Riddle, the guy who’d made the good play to deny the Mets. He hit a one-hopper a step to Lucas Duda‘s left — not a routine play, but one a first baseman needs to make. Duda didn’t make it. The ball clanked off his glove, and instead of two outs and nobody on the Marlins had runners on first and third.

- Jerry Blevins came in to face Ichiro Suzuki, who slapped a ball into the 5.5 hole, two steps to Wilmer Flores‘s left. A good third baseman maybe dives and corrals it, helped by quick reflexes and sound instincts. It’s not news that Wilmer lacks both those things, but this was an extraordinary misplay even by his standards: his first step was towards third, away from the ball. What in the world was he doing? Who knows? At this point, what does it matter?

That essentially was it — the five minutes in which the Mets lost thoroughly and irrefutably.

I could linger on other moments that made you shake your head or stare into the void — there was the five-second period where the Mets lost a hit, a run that would have tied the game and Robert Gsellman to the disabled list — but you get the idea.

And yet you know what? This morning, a few hours removed from this latest debacle, I found myself feeling sorry for Wilmer, stumbling away from the ball he was supposed to field, and smiling at the memory of the four days where we’d decided the Mets were winning it all and just barely managed not to shout the good news from the baseball rooftops.

As Mets fans we get caricatured as a woebegone fanbase waiting for the roof to fall in again, and that’s not wrong. But it’s only half of it. The other half is we play three games against the Giants and spend one day playing no one and extrapolate from the lack of losses that we’re going back to the World Series. And whether we disguise it with silence or with irony, we fucking mean it. That’s the flipside of being a Mets fan: an inextinguishable, irrational hope that roars back to life at the tiniest opportunity.

Which reminded me, inevitably, of Anthony Young. By now you’ve read Greg’s fine tribute to AY. Hearing of Young’s death at a mere 51, I of course flashed back to the end of his 27-game losing streak and the removal from his back of what AY admitted wasn’t just a monkey but a whole zoo.

I was living in D.C. but back at my folks’ house in St. Petersburg, Fla., for reasons I now can’t recall. I had to step away from the game, for reasons I also now can’t recall, but set up the VCR to tape the end of it. In the long-ago world before phones and Twitter, all I had to do was not watch SportsCenter when I returned to the house sometime near midnight with no idea what had happened. Standing there in the darkened house, I rewound the tape to find out.

1993 was the year the Mets had a tail on the front of their uniforms and a kick-me sign on their backs — an utterly miserable campaign in which every light at the end of the tunnel was the next in a line of bigger trains. But not that night. You can see the final pitch from that night on YouTube, and watching it again I was happy to find my memory and history hadn’t diverged.

The Mets have — as usual — betrayed AY with some lousy fielding and other horrors, but then sprung to life against the newborn Marlins. Which brings us to Eddie Murray. Murray doubles down the line, sending Ryan Thompson streaking around the bases as the winning run.

The focus turns almost immediately from the jubilant Thompson to Young, who starts off on the edge of the celebratory scrum but quickly becomes its center. There’s Todd Hundley putting an arm around his shoulders, and gigantic Eric Hillman reaching down to offer what for him was a low-five. (Aside: Wow what a terrible team this was.)

Young at first looks slightly annoyed by the whole thing, which you can understand: the streak existed in large part because of buzzards’ luck and his teammates’ betrayals, and this win has as little to do with him as most of the losses did. But he can’t stay stone-faced, not with big, bluff Dallas Green coming over to fold an arm over him and the fans at Shea cheering madly. Which they really are doing — they’re going nuts for a pitcher who just ran his record for 1-13. Which is what I was doing that night, albeit on tape delay — I was running around my parents’ living room hurdling furniture and laughing like an idiot.

The cheers are genuine, and so Anthony Young finally throws his hands up and surrenders to them. It’s a little bit comic and, OK, maybe it’s even a little bit pathetic. But it’s heartfelt. It’s real. In that moment no one at Shea Stadium could think of anything better than being a fan of the New York Mets — the 35-65 New York Mets. And at least for a moment, I bet every one of them was certain the 1993 Mets would ride Anthony Young’s 15-13 campaign to end the year at 97-65.

Next time Wilmer Flores stumbles thisaway instead of thataway or Lucas Duda looks dolefully at the ball that should have been in his glove — which probably means tonight — I’ll make sure I remember that.

by Greg Prince on 27 June 2017 7:53 pm Anthony Young died today, Tuesday, at the age of 51, several months after being diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor. When he pitched for us, we rarely referred to him as Anthony and basically never called him Young. He was AY to us. He was AY when L’s stuck to him like he and they were made of Velcro, and he was AY when a W blessedly stumbled into his portfolio. L’s and W’s were what we focused on when we focused on AY. We were men and women of letters with him.

I’m inclined to invoke scorer’s discretion and give him a parting W right now. AY had us on his side all the way through a career that, on the surface, shouldn’t have inspired excess affection. He was with us when the contemporary accumulation of Mets wasn’t extraordinarily likable, never mind lovable. But we liked AY a great deal. We looked past the L’s. He helped us see there can be far more to a person enmeshed in competitive endeavors than a bottom line can convey.

AY the person inspired rave-filled scouting reports, when he was playing and when he was retired. You could be given some leeway for grumpiness if you were caught in a vortex of undesirable outcomes. AY didn’t take it. He was, by all anecdotal and observational evidence, one of the good guys. The sadness of the final loss suffered by those closest to him speaks mournfully for itself.

AY the pitcher is inextricable from his record. He went 5-35 from his big league promotion in August of 1991 to his last Met outing in September of 1993. It doesn’t jibe with an ERA of 3.82, nor does it reflect 18 saves collected as a substitute closer. Yet that’s not the record we think of when we think of Anthony Young. No Mets fan who was around in 1992 and 1993 doesn’t know the record or at least the gist of it. No pitcher in the history of baseball had his name attached to more consecutive losing decisions. AY’s total reached 27 before the streak mercifully snapped.

It’s one of baseball’s oft-discussed and increasingly derided quirks that wins and losses are personally assigned to one man per game. Nobody ever talks about the winning second baseman or the losing left fielder. Only the pitcher, and it has to be the pitcher in the right or wrong spot and the right or wrong moment. Sometimes there’s no space for debate — one guy pitched really long and really well and the other guy pitched really badly from jump, and there’s your W and your L, put them in the books. Sometimes, however, a pitcher who winds up with one of those letters affixed to his name is extremely lucky or unlucky. To our custom of thinking, AY was usually the latter.

We understand the context. We didn’t and wouldn’t wish being known as the “loser” of 27 consecutive anythings on anybody (give or take a uniform). Yet associating Anthony Young with that word seemed wrong. Even the “unlucky” part didn’t fully fit. Anthony Young was a major league pitcher, given the opportunity to ply a unique skill again and again. It didn’t work out on a given day? He didn’t give up. Again and again he took the ball. Again and again something found a way to go awry. Again and again he was back on the mound, pitching well enough to earn the next chance. Surely his luck, as we conventionally conceive it, had to change.

Twenty-four years ago today, AY and I were at Shea Stadium trying to avert history’s tap on the shoulder. AY was sitting on 23 straight losses. I was sitting in Loge. He was trying to win. I was trying to root him toward that preferred result. No dice for either one of us. He pitched as he always did — professionally; and I rooted as I always did — faithfully. We each did what we could, yet we both absorbed another loss, the 24th straight for him, the new, unwanted standard. Not visible in that Sunday’s box score was we both gave it what we had and we were both back for more at the first available opportunity. It was as satisfying a transaction as AY and I could muster under the circumstances of 1993.

The streak ended a little over a month later. I strained to listen through static in Penn Station. My train was being called, but I had to wait, had to hear if the winning run was going to cross the plate. It did. The Mets beat the Marlins, by coincidence their opponent tonight, 5-4. Anthony Young was the pitcher of record on the winning side. There was a lot of cheering at Shea Stadium and a little in Penn Station.

AY won one game in 1993. The Mets won 59. Somehow, it was the best of times.

by Jason Fry on 26 June 2017 9:20 am Can we play the Giants for the rest of the year?

Let’s be clear about something: the Mets’ three-game sweep of San Francisco doesn’t mean they’re suddenly good. They’re just better than the Giants, for whom “can’t get out of their own way” would be a kind assessment. The Giants are having a once-in-several-generations cratering of a season, one that will be recalled with a snort, shrug or shudder in decades’ worth of broadcasts, season previews and blog posts. This is their summer of Roberto Alomar and Jason Phillips, the one that seems to take several years and then lingers maddeningly and eternally, like a dead thing under the house.

Still, that’s not to say Sunday afternoon’s game was worthy only of pity. Two performances stood out: those of Rafael Montero and Rene Rivera.

Theirs was the perfect pairing: the talented pitcher who can’t ever seem to get his head on straight and the pitcher whisperer who’s seen plenty of such problems. Montero has seemingly had about a billion chances, living through multiple exiles to various minor leagues and all but being branded soft and dishonest by his own employer, yet he won’t turn 27 until the offseason. Like Wilmer Flores, he’s been around so long that it’s easy to forget how young he still is, and to realize how much growing up in public he’s had to do.

Montero still wasn’t great — he was inefficient and occasionally lapsed into his trademark timidity, trying to gnaw at the edges of the strike zone instead of trusting pitches that are good enough to get big-league hitters out. But he was more than good enough, with 104 pitches carrying him nearly through six innings.

Rivera should get some of the credit — his value as a coaxer and cajoler of spooked hurlers has been apparent for some time. That’s a subtle thing, but there was no missing the two home runs he crashed over the fence, part of an unexpected offensive awakening that ought to be very good for Rivera’s future job prospects, as it’s likely that Travis d’Arnaud currently has his leg trapped in a Miami baggage-claim conveyer belt, has been pecked bloody by a maddened macaw, or suffered some injury even less likely than those two.

Points also go to Jay Bruce and Curtis Granderson, who get extra credit for not only contributing to a win but also making themselves look yet more attractive to some playoff-bound club. Granderson starts every spring looking like he’s overdue for the knacker’s yard but then suddenly plays like he’s two decades younger when actual summer arrives, an unlikely trick he keeps managing to pull off.

And points to Chase Bradford for becoming the 1,032nd player in team history instead of getting slotted into limbo as the prospective 10th Met ghost and third with no debut for anyone else. (If you think I’m overreacting to the latter peril, well, I’m sure Billy Cotton and Terrel Hansen thought they’d get another call-up too.) That’s a fate that would make even a 2017 Giant blanch.

by Greg Prince on 25 June 2017 8:26 am “Hey, Terry.”

“Yeah, Asdrubal?”

“Listen, I got an idea to get us going.”

“We could sure use one.”

“When I’m activated on Friday, put me at second.”

“Second? You sure? We didn’t even think of that. If we had, maybe we would have played you there while you were rehabbing.”

“Don’t worry about that. I’ve played plenty of second before. It’s no biggie. Here’s the thing, though — it’s not my idea.”

“What do you mean it’s not your idea? You just told me the idea. If it’s not your idea, whose idea is it? It’s not Dickie Scott’s idea. He would have told me on the bench while we were getting our asses handed to us in L.A.”

“No, Terry, it really is my idea.”

“Cripes, Asdrubal, I’m confused enough as it is by the time difference out here. I don’t know if it’s midnight or three in the morning, and every time I close my eyes, some frigging Dodger is hitting another home run. I was in the Dodger organization a lot of years, yet even I couldn’t take it anymore. Did I ever tell you I was in the Dodger organization? That’s where I met James Loney. Justin Ruggiano, too.”

“Yeah, you mentioned that last year.”

“I got a picture of me with Koufax in my wallet. Lemme get it out…”

“You showed it to me last trip, before I went on the DL. And the trip before that. I need you to focus, Terry.”

“Sorry, Asdrubal. What were we talking about? You don’t wanna play shortstop anymore? Why the hell not?”

“You tell the reporters moving me to second base is your idea, something about how it gives us the best chance to win, blah, blah, blah, and then I’ll pitch a fit.”

“What? You wanna pitch now? ’Cause we really could use a sixth starter.”

“Not pitch, Terry. Pitch a fit. Complain real loud, draw attention to myself, get a whole bunch of stories and tweets going.”

“Oh. Wait — why would ya wanna do that? This isn’t gonna be some bullcrap about migraines and models and MRIs you don’t wanna take. Are your hamstrings all right? I can’t keep track of what’s wrong with who anymore.”

“Trust me, Terry. I’ll say something about how I wanna get paid more to change positions and now I wanna get traded. Some real diva nonsense.”

“You’re Asdrubal Cabrera, the popular, respected veteran clubhouse leader. You’d never act like that. Who’s gonna buy any of this?”

“Gotta shake things up around here, Terry. Everybody’s too complacent. Everybody’s going through the motions. We need something to happen.”

“Hasn’t enough happened this year?”

“Not this. This is a whole other thing. I make a big stink about second base, all the heat and pressure is on me, then the rest of the guys relax, go out and play loose. One of the old guys in Cleveland taught me about it when I was a rookie. I think they made a documentary explaining it. It was called Major League. Or Major League II. Whichever one starred Albert Belle.”

“I don’t go to the movies during the season. I’m too busy trying to find a way to fit Granderson and Bruce into the lineup while not playing Conforto too much.”

“I can’t help you with the outfield, Terry, but this will take care of the infield.”

“Well, I’m frigging out of ideas, so, sure, you at second all pissed off about it for some reason. We’ll do that.”

“Thing is we gotta make it seem like I’m miffed at you, so you gotta play along.”

“Play along how?”

“Act all…you know, the way you do when reporters ask you stuff.”

“What do you mean the way I do?”

“Don’t sweat it. Just keep saying it’s gonna help the team and maybe throw in some of that jazz about how important communicating is.”

“Communicating is key, Asdrubal. I learned that in Anaheim. Cripes.”

“You’re a great communicator, Terry, but this time we gotta act like you’re not. We can get Sandy in on it and make a big show of having a meeting. Reporters love reporting there’s been a meeting.”

“Can’t I just write down the lineup and hit a few fungoes? I love fungoes. They’re so peaceful.”

“Terry, if it were that simple, we wouldn’t be buried in fourth place a million games out. We gotta do something.”

“Well, Asdrubal, you’re the popular, respected veteran clubhouse leader. Besides, nothing else has worked. Fine, I’ll put you in at second, ask Sandy to call up Rosario and…”

“No, you gotta keep Reyes in at short.”

“What? Why would we be doing this to keep a one-ninety-something hitter who barely covers any more ground than you — no offense…”

“None taken.”

“Why would we shift you to second just to have Jose at short? Jose looks stuck in the mud and we have this hot-shot prospect all ready to come up. He’s supposed to be the real deal.”

“Terry, man, you gotta have faith. I’ll play second, Jose’ll play short, the kid can come later, like after the break if we haven’t turned it around.”

“So now you’re the GM and the manager, too, huh? Want me to ask Jay to let you do his job while we’re at it?”

“Terry, I’m the second baseman. The disgruntled second baseman. And this is all your idea. Remember that. I know it sounds crazy, but it’s just crazy enough to work.”

“Cripes, why not? My contract is up at the end of the year anyways. They pay me either way before then. Anything else I gotta do, Mr. Popular, Respected Veteran Clubhouse Leader?”

“Yeah. It would help if we could play the Giants for a couple of days. They’re going really bad. Oh, and start deGrom on Saturday night. He’s going really good. That should get us two wins, and by then we’ll have so much momentum you can do something totally nuts like put Montero back in the rotation.”

“I was gonna do that anyway. Rafael’s been working on some stuff with Dan and I think he’s gonna surprise some people.”

“Sure, whatever. Thing is, we win at least a couple of games in San Francisco and we won’t necessarily be screwed until the next time we are.”

“I like it, Asdrubal. Nobody’ll believe this was the plan, but I like it.”

by Jason Fry on 24 June 2017 9:58 am Timing really is everything.

My kid and I got on a plane to Iceland a few minutes after the end of the Mets’ victory over the Cubs and returned a few hours before the first of their check-for-pulse efforts against the Dodgers. While overseas and four hours down the clock, I checked in on our stalwarts as arrival times and hotel Wi-Fi allowed.

I’ve done this on previous trips and there’s something equally wonderful and weird about sitting in the equivalent of late-afternoon daylight despite the clock showing it’s after midnight and watching baseball being played at night on another continent. You look from Gary Cohen’s face to Icelandic hillsides dotted with intrepid/foolish sheep and feel amazed to be part of the age of miracles and wonder.

But this time both miracles and wonder were in short supply, and my timing was terrible: I brought SNY up for one of the games against Washington and had just registered that it was 3-0 Washington when Wilmer Flores made an error, skulking back to his post as the score became 4-0. Like a rat who’d pushed a button and been shocked (not for the first or even the 101st time), I came to the conclusion that I’d seen all I needed to see of that particular game. And say what you will about the evils of jetlag, but it did replace six hours I would have spent suffering through miserable baseball in L.A. with relatively blissful shuteye.

Last night I arrived a bit late to my post because of an extended dinner, and braced for impact as I turned on the TV. For me, assessing what’s happening in a game I’ve joined in progress is often a slapstick affair. First my senses frantically collect information ranging from the score (generally obscured by some TV/cable status readout) and the inning to the tone of the announcers’ voices. Then my brain collates this data, often not particularly efficiently, until I’m fully caught up and manage to render a verdict of HA! or huh or [weary expletive].

This one started as a huh: I grasped that the Mets and Giants were tied 1-1 in the second, with Lucas Duda on second base. But then Lucas was steaming home on a ball slapped past eternal enemy Conor Gillaspie at third, a ball I realized had been hit by Seth Lugo. That was prelude to the Mets battering poor Ty Blach as Bruce Bochy watched stoically: Yoenis Cespedes annihilated a high fastball for a two-run homer and Wilmer Flores, Michael Conforto and Travis d’Arnaud all doubled, turning the huh into a definite and definitely much-needed HA!

(The craziest-ever moment of assessment: in late 2007 my plane touched down at JFK and I turned on my sports Walkman to find myself in the middle of the Jose Reyes–Miguel Olivo brawl. It was a long, busy time before Howie Rose was able to address that the Mets were up 9-0 and John Maine hadn’t allowed a hit. That was a lot to take in.)

Friday night’s game also featured the return of Asdrubal Cabrera, who collected three hits but had made headlines before stepping onto the field. Cabrera, displeased at being told he’s now playing second, asked for a trade. Cabrera’s pique mostly has to do with being surprised — he spent his minor-league rehab playing shortstop. Which is definitely a reason to be annoyed, and yet another example of the Mets fumbling basic communications with their players.

Left out of the conversation was the real reason Cabrera and every Mets fan should be annoyed: he’s being asked to move so the withered corpse of Jose Reyes can keep contributing four automatic outs per game. Jose was the only member of Friday’s starting nine to go hitless; he’s now hitting .191 with a no-that’s-not-a-typo .267 OBP. The only debate in Mets circles should be whether Jose is even worthy of a spot on the bench. (Spoiler: he’s not.) Pretending he’s an everyday player is negligence fueled by truly determined obtuseness, and that delusion will have consequences beyond a one-day media dustup.

* * *

I got my set of Topps Series 2 cards in the mail last week and found that the eBay seller had filled out the box with junk commons: a random assemblage of hockey cards, a bunch of Fleers and some hastily grabbed ’89 Topps cards.

The latter were frankly more interesting than the graphically busy, statistically light 2017 Topps cards, so I separated them out and let myself stroll down memory lane with the likes of Jeff Blauser, Jim Clancy and Mike LaValliere. The latter were frankly more interesting than the graphically busy, statistically light 2017 Topps cards, so I separated them out and let myself stroll down memory lane with the likes of Jeff Blauser, Jim Clancy and Mike LaValliere.

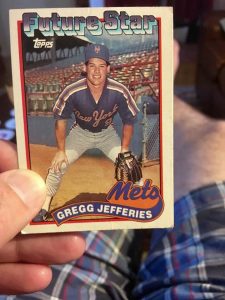

And then I got to the card that made me go oof.

Gregg Jefferies‘ first full season was so hotly anticipated that Topps made his Future Stars card part of the box art. He was on the cover of every season-preview magazine and all but inducted into Cooperstown before Dwight Gooden and Joe Magrane squared off at Shea for Opening Day. Jefferies went 2-for-3 that day but also made an error; 1989 would see too much of the latter and not enough of the former, as well as friction with teammates and fans. Eventually the Mets decided a professional divorce was best for all involved; Jefferies went on to become a Royal, Cardinal, Phillie, Angel and Tiger, forging a career that was pretty good by most standards except the impossible ones that had preceded him. He was out of the game before his 33rd birthday.

“Life comes at you fast” is an old adage that’s been revived as a Twitter taunt. It’s true, of course — changes of fortune arrive in an eyeblink, rearranging everything. But it keeps being true even as the moment passes, with today’s controversy becoming ancient history before you quite realize what’s happened. So it was with Jefferies, who went from the front of the box to filler inside it in a couple of baseball generations.

I never used that ’89 Jefferies card in The Holy Books. The original reason was probably that it still stung too much. I’d been a huge Jefferies fan during his rocket ascent in late 1988, blew the budget on him in next year’s college fantasy league, and waited for a triumph that wasn’t to be. But that’s become a long time ago. Seeing a Jefferies rookie come back to me, I decided to keep it and slotted him in, between The Other Bob Gibson and Mark Carreon.

And you know what? He looks good there, waiting beneath his own personal marquee for a future he can’t know will never arrive.

|

|

The latter were frankly more interesting than the graphically busy, statistically light 2017 Topps cards, so I separated them out and let myself stroll down memory lane with the likes of

The latter were frankly more interesting than the graphically busy, statistically light 2017 Topps cards, so I separated them out and let myself stroll down memory lane with the likes of