The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 14 June 2014 3:18 am Friday night in Dyersville, Ia., the 25th anniversary of Field Of Dreams was celebrated. That’s the movie in which legendary ballplayers of yore stream out of a cornfield in the full flower of youth and play the game that made them iconic as if no time at all had passed.

And in a wholly coincidental development, Bobby Abreu went 4-for-4 and Bartolo Colon pitched 7⅓ four-hit innings in the Mets’ Friday-the-13th victory over the San Diego Padres…on Zombie Night at Citi Field.

Our youth movement may not be amounting to much, but the Mets of the living dead seem to be alive and well.

Those New Faces of 1997 can still amaze audiences nearly two decades after their debut. Abreu and Colon were rookies in 1997, when Field Of Dreams was eight, Wilmer Flores was five and Interleague baseball was being born. Friday night also marked the 17th anniversary of the first regular season N.L.-A.L. game the Mets ever contested, versus the Red Sox. They lost to Boston at Shea, 8-4. By then, Colon had pitched six times for Cleveland and Abreu had accumulated 169 career at-bats with Houston. They were both already older than Interleague play, not to mention Derek Jeter, Alex Rodriguez and the Red Sox’ winning pitcher of June 13, 1997, Jeff Suppan. Today, they are older than dirt.

But dirt’s still got a few tricks up its well-worn sleeves. Colon was whacked around a bit in the first two frames he threw Friday against the Padres, who seem even more Metsian than the Mets in their offensive ineptitude. They got to Bartolo early but not often. Then they were completely shut down. Bobby, meanwhile, was open for business in the cleanup spot all night: doubling and scoring; singling and scoring; singling home Murphy; singling home Murphy once more. Together, the B-Boys — with a bit of help here and there from their more callow teammates — combined to overcome an early two-run deficit and secure a post-midnight 6-2 win.

The game crept beyond the witching hour because two hours of rain postponed its first pitch. That meant Abreu and Colon, each of them already past 40, grew yet a little more wizened as they waited to do what they’ve been doing since the middle of the Clinton presidency. Abreu would be playing in his 2,385th big league baseball game. Colon would be making his 418th start. What was a couple of extra hours against almost half a lifetime of experience?

It’s not like these guys quiver in the face of time’s inevitable march. Colon (6-5 for a 30-37 team) missed the entire 2010 season because of injury. Abreu (.319/.386/.472) was presumed done after not playing anywhere in 2013. The Phillies released him on March 27 of this year. The Mets picked up him up four days later and sent him to Las Vegas. So far he’s been their most promising minor league callup of 2014.

If you build it, maybe they will come. Some nights, though, there’s something to be said for renovating.

by Greg Prince on 13 June 2014 1:39 am Jon Niese looked like he wanted to strangle Terry Collins. Anthony Recker was all set to deck Angel Hernandez. Carlos Torres appeared ready to tear his own head from his neck out of frustration.

Who says the Mets don’t have any fight left in them? Hits and runs are another matter, of course, and few of either were produced by the home team across an unlucky 13 innings Thursday night at Citi Field.

This was the one with the three-minute rain delay that never made it to the tarp stage. The one with few commercials and many SNY gimmicks, the best of them Kevin Burkhardt joining the grounds crew (pre-rain) for a drag of the infield, not to be confused with this drag of a game. The one that featured Niese and Kyle Lohse mowing down each others’ teammates, which was probably a more impressive feat for Niese, considering he wasn’t the pitcher permitted to face the Mets. The only obstacle Jon Seether couldn’t overcome was his fireplug of a manager leaping out of the dugout with two out in the eighth to remove him when he was in full cruise mode.

Niese came out despite his well-earned objections (1 R, 6 H, 1 BB, 8 K), Jeurys Familia went in and the 1-1 status quo remained intact. Extra innings rolled around, not unlike the tumbleweed that presumably blew through the Promenade food court. The Mets still didn’t hit. The Brewers still didn’t hit. The commercials still didn’t air as SNY got in touch with its inner public-access self. The rain still didn’t stop but there were no more microdelays. All bullpenning from both sides proved impenetrable for the longest time, though Brandon Kintzler needed a little help, first from his Roenicke-rigged five-man infield, which cut down a run at the plate, and then from a one-man dispenser of vigilante justice who would never be tolerated in civilized society.

The bases were loaded with Mets in the eleventh — you could already guess that wasn’t going to end well, but still. Anthony Recker worked a two-two count before taking the world’s first low, outside strike…as called, of course, by Angel Hernandez, truly an innovator in the art of creative officiating. Recker was so disgusted that he didn’t get the chance to strike out honorably like most Mets that he furiously and instantly informed Hernandez of the myriad shortcomings he displays in his chosen profession. Giving Angel Hernandez an excuse to eject a catcher in extra innings is like giving an ape a banana. Of course he’s going to take it and stuff it in his umphole. So no, Recker shouldn’t have gotten himself thrown out, what with Collins’s bench down to Taylor Teagarden and splinters, but it’s Angel Hernandez in the eleventh. Who among us could resist vocally assaulting let alone bodily harming that arrogant piece of inaccurate dreck for one mist-soaked second if he was standing inches away…or closer than “strike three” was?

Anthony Recker: player of the game. Well, him or Burkhardt. We’re gonna miss that entertaining young man when he’s gone.

After the Mets allowed Angel Hernandez his chance to get the Brewers out of that jam (though, to be fair, they didn’t exactly help their own cause by sucking at hitting), Carlos Torres came in and walked a pretty nifty tightrope himself, stranding a pair of Brewers in the twelfth. Whereas Collins couldn’t help but pull Niese, he also couldn’t help but leave Torres in, and Carlos the Workhorse finally paid the price for overuse, getting clobbered in the thirteenth and then commencing to clobber himself. Trailing 5-1, the Mets proceeded to go down to characteristically efficient Francisco Rodriguez, 1-2-3, which, coincidentally, was the total crowd by the time the game was over.

Abandoned stadium. Lineup cobbled together from minor league callups. Manager and ballclub playing out the string. It was just one of those all-too-familiar late September evenings at Citi Field. Too bad it took place in the second week of June.

by Greg Prince on 12 June 2014 10:57 am The Mets didn’t win last night. Oh well. What were they going to do with a win if they’d attained it, anyway? Throw it on the pile of wins that never quite measures up to their taller pile of losses? Then what? Win again?

Come now.

Much as youth is said to be wasted on the young and plate appearances are almost certainly wasted on the Youngs, it occurred to me during Wednesday night’s tight but not exactly tense game against Milwaukee that wins are wasted on the Mets. I root for them to win, I find their winning preferable to their losing, but if they do win an odd game here or there, it’s not like they’re going to start winning them in volume. The Brewers, who won despite squandering multiple tack-on opportunities in classic Metsian fashion, seem like a team that could make good use of a win. They’re exceeding expectations and holding off the Cardinals as they maintain first place in their division. It’s hard to begrudge them an extra victory, even if it was earned at mostly vacant Citi Field in opposition to our beloved New York Nine. By contrast, when the Mets won the night before, what did it add up to? One more square x’d out on the pocket schedule, one more day until whatever year it is when wins and losses will severely matter to this franchise.

My favorite moment of the 2014 season to date, next to Ike Davis’s pinch-hit, come-from-behind, walkoff grand slam that beat the Reds (back when who won or lost a given game could still be interpreted as figurative life and death), may have been this past Sunday when Terry Collins removed Zack Wheeler with two outs and two on in the fourth inning in San Francisco. Zack had struggled some, ratcheting up his pitch count to an unsightly 86, but he wasn’t flat-out awful — but he also appeared not fully in control of his pitches or his emotions. He was in that zone talented young pitchers sometimes drift into, not having things go his way after two consecutive starts when he was mostly untouchable. The last hit he’d given up was a Tim Lincecum grounder that snuck by Ruben Tejada. The next batter due up was lefty Gregor Blanco, who had driven in a pair in the second when he doubled convincingly off the righty Wheeler

The develop-now, win-later handbook suggests you let Wheeler learn on the job. You let him face Blanco because as you’re cultivating one of your theoretical handful of aces, you know he has to deduce how to retire a troublesome lefty in a tough spot. You assume this is a moment that will tell you something about Zack and maybe in few decades, Zack will be announcing a baseball game on TV and telling his partners about the time he had to grow up in a hurry in San Francisco. If Zack Wheeler is this generation’s Ron Darling — his career trajectory to date feels fairly similar — this is where Davey lets Ronnie go after Leon Durham or Dave Parker.

Plus, to use the reigning manager’s favored vernacular, it’s only the stinkin’ fourth inning, for cripes sake.

But this was where Terry, saddled with a five-game losing streak and momentarily stripped of his pitching coach (Dan Warthen was off attending a graduation), decided not to be Davey Johnson in 1984, but Casey Stengel in any number of years when Casey saw the chance to pounce. Stengel was known to pinch-hit for his pitcher ASAP if he thought he could break a game open, no matter the inning. He did it for the dynastic Yankees of the 1950s and he did for the dreadful Mets of the early 1960s. The longest relief stint in Mets history, Larry Bearnarth’s ten innings thrown against the Cubs just over 50 years ago, was a result of Stengel sending up Rod Kanehl to bat for Bill Wakefield, who had already replaced Al Jackson, in the second inning. Kanehl singled to continue a rally that gave the Mets a lead…that they promptly gave up; these were the 1964 Mets, after all. The larger point is Casey understood a game could be won or lost in the early innings as much it could be later on. The Mets, as it happened, won that particular game on June 9, 1964, 6-5, in twelve, and Kanehl, like Bearnarth, played a huge role. (Read all about it here!)

The Mets have emphasized “later” seemingly forever. On Sunday Terry opted to be about now, albeit on defense. He could’ve let Wheeler find himself. Or he could’ve decided the long flight back to New York would be even longer if the Mets had to schlep a sixth consecutive defeat onto the plane. He decided the paramount goal in the moment was not letting Blanco extend a 4-2 Giant lead until it was out of Met reach. So he patted Wheeler on the ass, called on his newly rediscovered lefty toy, Josh Edgin, and Edgin took care of Blanco to keep the Mets viable a little longer.

A loss was in the offing anyway, but I liked the move. Wheeler not getting the opportunity to redeem himself is as much a lesson as anything he would’ve gleaned from another encounter with Blanco. And Collins, for at least an instant, shook things up in a meaningful, competition-minded way.

Sending down Travis d’Arnaud sent a similar message, though it shouldn’t have been a difficult one to transmit. “Don’t hit .180 and expect to start in the big leagues” should be self-explanatory to a rookie, no matter how much of a can’t-miss prospect he’s been labeled forever. I don’t worry that d’Arnaud is a “bust” based on 2% of precincts reporting any more than I worry about Wheeler not being Matt Harvey. Jerry Grote, John Stearns and Todd Hundley all turned into stalwart Met catchers who ranged from competent to spectacular as offensive contributors, yet they were all overmatched by opposing pitchers when they came up to the majors. Hundley was yo-yo’d for a couple of years between AAA and MLB and split more assignments than he would’ve liked with Charlie O’Brien and Kelly Stinnett before fully establishing himself as a legitimate starting backstop. Chronic viewers of Mets Yearbook: 1976 will recall Stearns asked to be optioned to Tidewater so he could hone his skills daily rather than sit behind Grote. Catchers not named Piazza or Posey take time. The Mets, based on their fierce lack of urgency, have plenty of that.

The only part of d’Arnaud’s d’Emotion that didn’t sit right was reading that he and his teammates were “shocked” that it happened. At .180 and showing zero power, they should have been shocked that he hadn’t been Vegas-bound sooner. I suppose their reaction is indicative of how little emphasis the Mets place on the Mets winning ballgames. Travis is hitting again out west. Swell. Keep hitting and come back soon. Taylor Teagarden’s Tuesday night swing for the ages notwithstanding, we’re gonna need Travis d’Arnaud like we’re gonna need Zack Wheeler.

Someday it’s not going to be a question of eventual development versus immediate performance. For now, though, it’s nice to be reminded that winning means a little something in the short-term.

Terry Collins clearly wasn’t brought in to mold a winner. The best thing anybody has to say about his skill set is he communicates well with his players and that he doesn’t lose the clubhouse. Apparently keeping replacement-level talent calm trumps getting much out of it. As of last night, Collins had managed 551 Mets games without compiling a winning record in any of his three-plus seasons at the helm. If he leads these Mets to at least 53 wins in their final 97 games this season and finishes at 82-80 (or better), then he’s off the board in that regard. Until that happens, here are the most Mets games managed without as much as a winning season in the portfolio:

Joe Torre: 706

Casey Stengel: 579

Terry Collins: 551

Dallas Green: 512

It’s unusual to get to hang around if you don’t win anything. You couldn’t tell from the Mets and Collins, but winning usually means something in baseball.

Stengel was a singular figure in unprecedented expansion circumstances. It was a broken hip that took him out of the game. Torre, as new to managing as Stengel was old but ultimately a Hall of Fame skipper just the same, was given yards of rope in light of his hollow roster and reasonably glamorous name (yes, even then). Joe also benefited from Frank Cashen not having quite enough time or juice to immediately eliminate him when Cashen took over as GM basically five minutes before Spring Training heading into Torre’s fourth season. Green’s charge was to clean up a bleach-stained mess; he had the Mets noticeably improving for a couple of years before they regressed into unquestioned mediocrity. At that point, like most managers who guide teams to terrible records, he was replaced.

Sooner or later, somebody takes the fall for 77-85, 74-88, 74-88 and (current winning percentage pro-rated to 162 games) 72-90. We’ve seen all our lives it’s usually the manager. It’s not boorish to begin to wonder what Terry Collins brings to his role if it’s not an ability to win a lot or just win a little more than has been the case. All that vaunted communication doesn’t explain why young players come up, are touted as real helps to the lineup and then get glued to the bench within two games. On Sunday, Collins had a reasonably better option in the moment when he removed Wheeler and summoned Edgin. Most nights he’s not exactly sitting Andrew Brown or Wilmer Flores because he’s blessed with Billy Williams and Barry Larkin. It’s a fine line discerning what you do, with limited personnel, to win this very game right in front of you, as opposed to what you do with an eye on what underknown quantities might become if only you gave them more consistent reps.

In our Metsopotamian world, you get whatever’s left to be wrung out of Bobby Abreu’s last legs and the amortization of Chris Young’s megamillions deal and the increasingly untantalizing teases provided by Lucas Duda and Ruben Tejada. You get a gratifying grand slam out of nowhere from a journeyman catcher but not an actual solid backup option who could mentor your projected star receiver. You don’t get the most for your roster-construction dollar, even considering this is a team operated on a shoestring, so you don’t get all that excited by an individual win or loss, yet you still wonder whether that’s a case of the team being bad, or you, the fan, being not as good as you could be because you’ve stopped taking losses to heart the way you always used to.

You see the ranks churn — only four of the 21 players used in the 20-inning game of just over one year ago are on today’s active roster — but you don’t see much change. You remember grumbling like this when the Mets were wallowing at 24-39 last season, but then, a week after that marathon loss to the Marlins, your spirits were hoisted sky-high when Kirk Nieuwenhuis hit a home run off Carlos Marmol and the Mets took 22 of 37 and you thought things were turning for real. But since that invigorating stretch expired in late July, the Mets have gone 57-71, which is the mathematical expression of More Of The Stinkin’ Same, For Cripes Sake.

And though you’re happy to watch on TV because the announcers are so much fun, and if you’re not near a TV you’re fine with the radio because those guys are fun, too, you notice you’re thoroughly unmoved to get up and go to the ballpark. You think about going, but then you decide, what fun is that?

by Jason Fry on 11 June 2014 1:02 am You can all thank me now.

In the bottom of the sixth, with the bases loaded and two outs and 981st Met in history Taylor Teagarden at the plate, something I’d been wondering about for a day or two finally coalesced in my head, and so — as happens these days — emerged as a tweet.

I got there because they say it takes two points to make a line, and I found myself with three.

The first point had shown up on Metsblog a couple of days back: a note that the Mets were 8-17 in one-run games. Every baseball fan knows such extremes aren’t sustainable: Here’s some proof if you’re feeling mathy; if not, the lowdown is that too good or bad a record in one-run games suggests luck is at work, and a regression to the mean is on the way. And that’s important: Metsblog noted that if the Mets had even managed a mediocre 12-13 record, they’d be tied for first place. In the underwhelming NL East, granted, but it counts.

The second point arrived via ESPN’s Mark Simon, who posted this during the afternoon:

Basically, the Mets are in the middle of the pack in terms of balls hit hard, but at the absolute bottom when it comes to converting those balls to hits. When I asked Mark if he hadn’t essentially posted a Luck Index, he warned that big ballparks could have an impact too. (And indeed, you’ll find the A’s and Giants a bit lower than you might have expected.) But it seems safe to say that there’s a fair amount of luck involved — I wasn’t surprised to see the Blue Jays in the top spot.

Then, finally, there was a note tonight from the SNY booth, not long before Teagarden stepped into the box: The Mets were ranked third in baseball at getting runners into scoring position, but 24th in on-base percentage with runners in scoring position.

You can chalk that last one up to ill-advised hitting philosophies, the fear of fans booing, or mental toughness. (If you must. Perhaps sunspots and the Illuminati are involved too.)

Or maybe that one is also shaped by a fair amount of luck.

Anyway, all this came together in my head, I tweeted my serious question, and approximately two seconds later Teagarden hit a liner over the right-field fence for a grand slam, turning a 2-1 lead you figured wouldn’t last into a 6-1 prelude to a rare and incredibly welcome laugher.

We don’t like to think too much about the role luck plays in the outcome of baseball games, let alone seasons. Or at least I don’t — it makes watching baseball feel a bit too clockwork, like I’m staring at some kind of flesh-and-blood version of Pachinko. So instead we do something that’s more satisfying but no more logical: We make up stories to fit the data. You know the drill: Good teams are resilient and well-led and have chemistry; bad teams are lazy and rudderless and selfish.

This isn’t something we do just with sports. We’re wired for it as humans — we’re extraordinarily good at finding patterns and ferreting out connections. Most of the time that helps us learn and plan and succeed. But the side effect is we’re also pretty good at finding patterns where there aren’t any, insisting we hear signal when there may not be anything but noise. And that can lead us to silly conclusions — or sometimes ones that are unfair and/or dangerous.

Look, the Mets have a lot of problems that are definitely signal: a withered payroll, untrustworthy owners, and too many ABs and innings given to subpar players. But on top of that, they sure look like they’re contending with more than their share of lousy luck — noise, in other words. If that sorts itself out, as such things tend to do, perhaps things aren’t quite as bleak as they appear.

And if not, what the heck — at least it’s a nice thought to kick off the Taylor Teagarden Era.

by Jason Fry on 9 June 2014 1:23 am On Saturday we threw a party to watch the Belmont Stakes. I enjoyed the bourbon a little too enthusiastically, fell asleep before the Mets starting playing and woke up hours after the game was over.

It was the best Mets experience of my week.

Today’s game wasn’t quite as infuriating a gag job as Saturday’s, but it followed the all-too-familiar recipe: not enough hitting, dopey baserunning, and bad defense, followed by excuse-making from the manager. If the Mets were a game of Clue, the revelation would be that everyone killed them, in every room, with every weapon. The Mets don’t lose with such numbing regularity because they’re consistently bad at one aspect of baseball; they lose like that because they’re consistently bad at multiple aspects of baseball.

And help is not on the way — the farm system has some hitting talent at the lower levels, but those players are all probably two years away. There’s no position player waiting in the wings a la Noah Syndergaard. No blue-chipper is wearing out pitchers in Las Vegas and clamoring for playing time in New York. Instead, we have guys we counted on to produce at the major-league level going back down a rung to get themselves figured out.

What the Mets do have is an abundance of talented starting pitchers — as I’ve written before, the team could go to spring training next year with 10 guys worthy of a spot in a big-league rotation. Even with elbows exploding across baseball and young pitchers being maddeningly unpredictable, that’s a surplus. And given that the Mets have a glaring deficit of decent bats, I find it impossible to believe the front office won’t move a number of those pitchers for hitters who are close to big-league ready.

If Sandy Alderson trades wisely, the Mets’ future could look a lot more promising in a hurry. (Personally, I’d start the dealing with Jon Niese and Jeurys Familia.) But the most opportune time to make such a deal is probably late July, meaning we have another six weeks of hideous baseball to endure.

Since I don’t recommend nightly sessions with Dr. Bourbon, how can those six weeks be made more bearable?

The Mets actually already took the first step by sending Travis d’Aranud down to get his mind clear and/or to get him the 500-odd Triple-A at-bats he might have needed in the first place. I’m a fan of d’Arnaud’s, but I was still glad to see that happen — he was lost at the plate and looked like he was trying to carry the franchise on his shoulders. Hopefully he can get well away from the bright lights.

What’s next?

How about declaring an end to the Chris Young experiment? Young wasn’t a terrible bet to rebound, but he hasn’t and you can’t say it’s a small sample size anymore. And he was never a part of the future, just a bridge to it, a la Kyle Farnsworth and Jose Valverde. So Farnsworth him and give the at-bats he’s wasting to Bobby Abreu (a bridge piece who’s earned those ABs), or better yet to Andrew Brown, Eric Campbell or Matt den Dekker. (And not to Pinch Runner Deluxe Eric Young Jr. when he returns, a date I’m not pining for.)

Second, find a place for Wilmer Flores to play. If it’s shortstop, let him play there for six weeks as a Met and see if he can do it. If it’s second base, send him to Vegas and call him up after the inevitable Daniel Murphy trade. If it’s third, first or DH, trade the poor guy. But give him a position already.

Third, and directly related, no more kids on the bench. Flores needs to start. Same goes for Campbell, who’s followed the usual Terryland path from hot hand to guy you forget’s on the roster. (Somewhere Josh Satin is shaking his head sadly.) Brown got regular ABs in Vegas and was tearing it up; he looks good right now but won’t when he’s playing once a week. Enough already.

Third … well, I don’t know what’s third. Six more weeks of hopeless baseball, I suppose, with the Mets done in by all the usual suspects, with all the available weapons, in every room of the mansion.

Ugh. Paging Dr. Bourbon.

by Greg Prince on 8 June 2014 3:41 am “All right guys, we have to get a few more of these in the can before the next homestand, so I appreciate you coming in early on a Sunday. Just like always, stare directly into the camera and show the enthusiasm that got you this gig. And…action!”

“Branden, I’m so excited about what the Mets are giving away this Friday!”

“You mean like the way they gave away Saturday night’s game to the Giants, Alexa?”

“Cut! Cut! Branden, just stick to the script. And…action!”

“Branden, I’m so excited about what the Mets are giving away this Friday!”

“Yes, Alexa, it’s another free shirt, though with this team, you can just take the ‘r’ out of ‘shirt’ and be left with exactly what the Mets are all about this season.”

“Cut! Cut! Branden, the sooner we get through these, the sooner we can all go home. Let’s try the next one. And…action!”

“Branden, did you know that every Sunday at Citi Field kids under 14 get to run the bases just like the Mets?”

“Just like the Mets? God, I hope not, Alexa. Did you see how they ran the bases in the third inning against the Giants? What a bunch of freaking amateurs.”

“Cut! Cut! Branden, the Mets aren’t paying us to do our own version of Daily News Live here. Let’s just read the next spot. And…action!”

“Branden, what could be more fun than coming out to see David Wright play baseball?”

“Maybe seeing David Wright take a seat and somehow get his head together? He looks totally lost at the plate, Alexa, and now he’s making stupid, costly errors, too. If you can’t count on David Wright, what can you count on with this miserable team?”

“Cut! Cut! Branden, baby, I know it’s tough, but you gotta persevere. Let’s do the next one. And…action!”

“Branden, can you imagine a better treat for Dad than taking him to a Mets game on Father’s Day?”

“Father’s Day? Kind of an ironic proposition, Alexa, given that the Mets are playing like the saddest bunch of bastards I’ve ever seen.”

“Cut! Cut! Branden, you’re supposed to mention ‘face-painting on Mets Plaza’ there. C’mon, work with me. Just read the next card. And…action!”

“Branden, with the Mets Family Four Pack, there are some tough decisions to make between a Nathan’s Hot Dog, a hamburger or a slice of pizza!”

“Well, Alexa, you can be sure if there’s a decision to be made, Terry Collins will inevitably make the wrong one. Dude shouldn’t even be managing the Kettle Corn concession up in Promenade.”

“Cut! Cut! Branden, I don’t think that’s what it says on the card. Just a few more, guys, and I promise we’re outta here. And…action!”

“Branden, we’ve gotta make sure we catch the Mets’ upcoming games against the Brewers and Padres this week!”

“Alexa, we have a better chance of catching a game than Anthony Recker does of catching a crucial third strike or Travis d’Arnaud does of catching anything now that’s he and his pathetic .180 batting average have been shipped off to Vegas. What the hell took them so long?”

“Cut! Cut! Branden, please, just concentrate and I swear this will be over soon. And…action!”

“Branden, a day at Citi Field is a great time for fans young and old!”

“Excuse me, Alexa, did you just mention Young? Could Chris Young be a bigger bust?”

“Cut! Cut! Branden, you’re usually so on message. The next one will get you back in the groove. And…action!”

“Branden, the Mets have a promotion that’s sure to be a hit!”

“You know what’s sure not to be a hit, Alexa? Most any pitch thrown to any Met with the bases loaded — or any pitch ever thrown to Bartolo Colon. Ya think he could at least try to make contact?”

“Cut! Cut! Branden, I don’t think you’re in the spirit of things the way you usually are, but I know you can nail the last one. And…action!”

“Branden, the Mets have some really Amazin’ ticket deals!”

“Alexa, it would be amazing if anybody showed up to see this crap in person. It’s bad enough watching it on TV. My conscience won’t allow me to mislead our public any longer. Folks, it’s me, Branden. Get out while you still can! Don’t fall for these come-ons anymore! The Mets aren’t getting any better! They’ll never get any better! There are 100 games of this left! You have to find something else to do with your summer! Something else to do with your lives! No free shirt is worth this kind of pain! C’mon Alexa, let’s find Christina and spread our message of truth to Mets fans everywhere!”

“Cut! CUT!”

by Jason Fry on 7 June 2014 12:58 am Well, for 10 minutes or so that looked like a nice ballgame.

The Mets looked like they might get no-hit by Matt Cain, but escaped that indignity when Ruben Tejada slapped a single beyond the extremity of where a shortstop can field it. Hooray for a hit, but could they score a run? They’d need to, because Jonathon Niese had been scratched for one when Brandon Hicks — whom you may recall as having done absolutely nothing with a glove or a bat for the Mets in spring training this year — tripled and Brandon Crawford drove him in with a sac fly.

But wait! In the top of the seventh Matt den Dekker doubled and for once I was actually OK with the inevitable Terry Collins bunt. But nope, Daniel Murphy drove a home run off the top of the right-field wall, and just like that the Giants were the ones who were behind, victimized by the kind of thing that we think only happens to us.

Unfortunately, there were still pitches for the Mets to make. Or not make. With two outs in the bottom of the seventh Niese walked the irritatingly no-longer-terrible Hicks, then threw (in rapid succession) a wild pitch and a poorly located pitch. Crawford lashed the latter into center, we were tied, Carlos Torres took over and hung a slider to Buster Posey, we were no longer tied, and you knew the Met bats weren’t going to do anything else. At least it only took 137 minutes for the loss to be recorded, instead of the usual twice that.

Whatcha gonna do? The Giants are good; the Mets aren’t good. The Giants had two productive Brandons; the Mets only have Brandon of Brandon & Alexa fame, though honestly he couldn’t be worse than Chris Young. It was fun walloping the Phillies a long time ago on the other side of the continent, but nothing has been fun since. The Mets will probably win another game, though I wouldn’t be shocked if they didn’t.

Since there’s more season to play, some options:

1) The Mets quietly disband after losing the last two games of this series. Would anybody notice? SNY could run ads for 50 Cent’s concert, Brandon and Alexa could continue acting excited about unexciting merchandise, and Mr. Met could become a goodwill ambassador for the city as a whole. We could spend the rest of our lives in an ahistorical void watching endless Mets Yearbooks, tweeting at each other that Dave Kingman seems nice when he’s been given a shitload of Thorazine and that everything will be better now that Tim Foli has arrived. Or was that Mike Vail?

2) Go horseback riding with Ticket Oak. Screw it, it’ll probably go better than staking one’s happiness on this misfit band.

3) Keep watching this increasingly boring, slow-motion train wreck.

I guess we’re stuck with No. 3, but right now I’d sign on for Nos. 1 or 2.

by Greg Prince on 6 June 2014 12:20 pm Beautiful Wrigley Field isn’t quite so beautiful when it is lit by electric as opposed to natural means. Ever since the Mets had their lights turned out on August 9, 1988, losing to the Cubs in what became Wrigley’s first official night game (following a rainout the ballyhooed night before), it seems mostly bad befalls them on the Near North Side of Chicago once the sun goes down.

There are exceptions. The Mets executed their most bountiful inning ever in the Wrigley dusk of 2006. A former Brave donned a Mets uniform in 2007 and won himself a 300th game, which seemed like something to revel in at the time. It’s been 26 years since Wrigley stopped hewing exclusively to bankers’ hours, so there’s probably some other enchanted evening that’s not springing to mind immediately, though I can’t think of it right now.

Mostly, Met nights at Wrigley are like the three we’ve just witnessed, episodes in which our cast of characters proves unready for prime time, whether the show begins at 8 o’clock Eastern or 6 o’clock Central. If the Mets aren’t scoring eleven runs in a sixth inning or assisting a Manchurian Brave to a personal milestone, they’re usually doing something along the lines of what they did all this week.

They’re losing. Thursday night they threatened to win, but it was an idle threat. Andrew Brown’s return from Las Vegas was pleasant enough — he performs well on any semblance of an Opening Day — and the roar back from an 0-4 deficit to a 4-4 tie provided a few minutes of false encouragement, but then Anthony Rizzo went deep and the Mets still had runners to strand and, well, the whole thing dissipated as it tends to do after dark in that part of town.

It was probably just cosmic coincidence that, smack in the middle of this sweep at the hands of what is still technically the worst team in the National League, one of the best-known members of what is still legendarily the worst team in the annals of the National League was reported passed away at age 83. Don Zimmer, as you’ve been reminded thoroughly by now, was an Original Met. Because Zimmer made baseball his business from 1949 forward and his profile in the game only grew with time, he became, by the 21st century, perhaps the most famous of all 45 players who could call themselves 1962 Mets. He’s not in the Hall of Fame like Richie Ashburn and he doesn’t maintain a sensational case for being in the Hall of Fame like Gil Hodges (who would be the last to manage Zimmer in the big leagues, with Washington in 1965), but 52 years after contributing indelibly to a 120-loss maiden voyage, it seems nobody didn’t know his name.

Not bad for an .077-hitting infielder who was swapped to Cincinnati for Cliff Cook and a spare Bob Miller before the franchise was four weeks old. Mind you, the Mets were just one of approximately a bajillion stops in professional baseball for Zimmer, but you can’t start counting Mets until you go around the horn on April 11, 1962, and take note of who the first third baseman in Mets history was. You maybe wouldn’t start anxiously counting Mets third basemen — a popular pastime for much of the ballclub’s existence — if Zimmer had a little more zimmo to his game when he came to the Mets at 31, one year after his sole All-Star selection. There wasn’t much zip left to Zimmer when 1962 rolled around, which put him in very common company on a roster of certifiable used-to-bes. Zimmer’s Met legacy, to be repeated into near-eternity by Ralph Kiner, was Don tumbled into an 0-for-34 slump that April, climbed out of it with a double off the Phillies’ Dallas Green, and was traded away two days later, just when he was getting hot.

“The way things were going for Don Zimmer,” Post beat man Leonard Shecter would reflect years later, “everybody knew he would soon be gone. It wasn’t only that he was hitting so poorly, it was that he was such a good raconteur that he was too good to last.”

Zimmer would go on telling stories and creating content for another five decades. The Mets would continue replacing him at third with alarming frequency throughout the 1960s. Sportswriters would keep tabs on just how many third basemen the Mets had gone through since Zimmer, with 38 receiving a shot at the hot corner in their first six seasons. For the record, when Eric Campbell shifted from first to third last night after David Wright was double-switched out of the game (stunning to consider, but he did make the previous inning’s final out…and nothing but outs the entire series), the all-time total inched up to 153. It doesn’t quite match the Zimmer-born pace set in the franchise’s formative years — thank you, David — but it’s significant enough so that somebody’s still keeping tabs.

That the positional progeny of Popeye expanded their ranks in the wake of their progenitor’s passing can be taken as ironic, I suppose, but what I found most moving in terms of time and place was that the Mets were in the midst of playing three night games at Wrigley Field. It was Don Zimmer who was managing the Cubs that night in 1988 when the Mets got off on the wrong, dark foot, and it was Don Zimmer who was managing the Cubs on the night in 1989 that basically defined what the next quarter-century of nights at Wrigley would be like for the Mets.

I think we’d all agree that rooting for a team with a winning record is preferable to rooting for a team with a losing record. Being as practiced as we are lately at rooting for a team with a losing record, and recognizing how we’d prefer anything else already yet, should confirm that hunch. Nevertheless, not every team above .500 is more fun than a barrel of Mookies. Twenty-five years ago, entering the action of June 8, 1989, Mookie Wilson was batting .193 and the Mets were a .527 club overall. They weren’t bad in the sense that we’ve come to understand bad, but they weren’t much good. These were the Mets from whom much was expected, so being only three games over, not to mention 2½ games out, wasn’t the cause for jubilation it would be today.

The team the third-place Mets trailed, however, was having itself a party. That was the Chicago Cubs, still managed by Zimmer and far exceeding their limited expectations. The Cubs had trudged along after outlasting the resurgent Mets in 1984 to win their first title of any kind since 1945. In October of ’84, the Cubs’ lack of lights was the talk of baseball, for if the N.L. East champs won the pennant — and how wouldn’t they, up 2-0 over San Diego in a best-of-five NLCS? — NBC wasn’t going to happily air midweek daytime World Series games and call it a paean to tradition. 1945 was long over in Corporate America, no matter what the stubbornly sun-dependent scheduling at Wrigley suggested.

If the Cubs had gone to the Fall Classic, they would have ceded home-field advantage to the Tigers despite it being the N.L. champs’ turn to host. Of course, the Cubs didn’t go (if they did, they wouldn’t be the Cubs the way they still are) and the lights blazed at Jack Murphy Stadium that October. But the fight to light Wrigley Field, led by Cub GM Dallas Green — the same Green who gave up Don Zimmer’s final Met hit in 1962 — intensified and its incandescent conclusion grew inevitable. Thus, the Mets found themselves losing in Chicago on the night of August 9, 1988, and found themselves trying to win in Chicago on the night of June 8, 1989.

That Thursday night, whose silver anniversary arrives Sunday, was a struggle as most nights and days were for those Mets. They were over .500, yes, and they had been the consensus favorites to repeat as winners in the East, but they were losing ground to Zimmer’s Cubs in the standings and on the scoreboard. Ron Darling (4.12 ERA) wasn’t sharp and left after six, trailing, 4-2. Lee Mazzilli, pinch-hitting for Kevin Elster, doubled home Gregg Jefferies in the seventh to pull the Mets within a run. And with one out in the ninth, Kevin McReynolds tagged Mitch Williams for a solo home run, tying the score at four…same as last night, come to think of it, after Brown took reliever Justin Grimm deep with a man on (something pitcher Travis Wood did to Jacob deGrom earlier in the game).

Unlike last night, though, extra innings beckoned. The contest of June 8, 1989, moved to the bottom of the tenth. With one out and Don Aase — Don Zimmer’s alphabetical bookend on the permanent Met attendance sheet until David Aardsma came along last year — pitching, Jeff McKnight, who had pinch-hit for Darling and took over for Elster once Mazz batted for him, booted a Lloyd McClendon grounder in his first-ever game as a major league shortstop. Curt Wilkerson then singled for his fourth hit of the night, moving McClendon to second. Aase then hit Shawon Dunston to load the bases.

For those of you whose only exposure to bases-loaded situations has been how the 2014 Mets offense vanishes during them, it might surprise you to learn that a team’s chance to score a run usually increases when it loads the bases. The contemporary Mets, you see, are an aberration in that regard. Therefore, you had to like the Cubs’ chances in this situation. They had runners everywhere and Aase had nowhere to put the next hitter. Then again, the next hitter was a rookie catcher named Rick Wrona batting .194, or ten points higher than rookie catcher Travis d’Arnaud is batting right now. Behind Wrona was leadoff hitter Doug Dascnezo, who was hitting a sub-d’Arnaudian .152. The Chicago Tribune referred to Wrona as the Cubs’ “forgotten man”.

What to do? The Mets of 2014 would wait for Noah Syndergaard to heal, Mike Conforto to develop and varied and sundry nebula to align perfectly. The Don Zimmer of 1989, demonstrating admirable impatience, ordered a bunt.

Yes, a bunt with the bases loaded. The thing nobody does these days and didn’t do that much then. But after Aase’s first pitch was fouled off, Don Zimmer told Rick Wrona to do it.

“If they get me,” the manager who survived 34 consecutive hitless at-bats as a 1962 Met reasoned, “they get me.”

Guess what. They didn’t get him. Wrona squeezed toward first base. McClendon came rumbling home from third base. All Cubs were safe. All Mets had lost, 5-4. “This game probably bothers me more than any other loss this year,” Davey Johnson said afterward.

That same game, though I had to refresh myself on the details, has bothered me longer than most June defeats of 25-year vintage, for the fuzzy memory of “the Mets lost here that night Don Zimmer squeezed with the bases loaded” never fails to shoot through my mind when the Mets are sentenced to night games at Wrigley Field. Wrona bunting home McClendon at Zimmer’s behest is what I can’t help but think of when the lights come on at the corner of Addison and Clark and the Mets are conscripted to serve as the visiting attraction. Wrigley wasn’t built for night games. It’s unnatural. It never feels right and the detrimental Met result usually bears that out.

It’s a feeling that’s too haunting not to last.

Zimmer’s Cubs kept doing stuff like that for the rest of 1989, beating out those endlessly frustrating and soon-to-be Mookieless Mets by 6½ games to win another division title; they played a pair of night playoff dates at Wrigley for the benefit of NBC and lost the pennant in five to the Giants. They still haven’t made the World Series since 1945. Zimmer, though, went a bunch of times as Joe Torre’s bench coach, including the Series when Roger Clemens flung a broken bat at Mike Piazza and Zimmer and hurled some unfortunate invective toward Mike in the aftermath. Eventually, he told George Steinbrenner he could stop writing him checks and moved on to the Rays, where his lovable nature was fully restored for the rest of his life.

Today, no matter the lousy mood we we’re left in from last night and the night before and the night before that, we salute Don Zimmer’s innate Original Metsness…despite his frustrating us in 1989; despite his defense of the indefensible pitcher following 2000; despite his getting in the way of Pedro Martinez in the heat of 2003. We remember him fondly enough at the end of a week when the Mets dropped three night games in a row in Chicago on the heels of taking four of five in Philadelphia.

Just when we were getting hot.

by Jason Fry on 5 June 2014 1:07 am For that, I need the Mets to keep playing well against lousy competition and hold their own against mediocre foes, to say nothing of taking on the big boys of the NL. I need to watch a lineup that scares somebody other than me. I need a whole lot that this team shows no signs of delivering quite yet.

OK, when I wrote that not so long ago, I figured the Mets would take two out of three from the Cubs, because they’re the Cubs. I was more worried about the Giants, Brewers and Cardinals.

But no, the last two nights the Mets have proved me right in gag-inducing fashion. The first game at Wrigley wasn’t the worst defeat the Mets had suffered all year, but it was definitely the most annoying. The team beat itself quite impressively, with Daniel Murphy costing them a run on the basepaths, David Wright muffing a double-play grounder, Scott Rice failing to do the only thing Scott Rice can sometimes sort of do, and nobody managing to get a big hit when it was needed. As a team-wide failure, it was impressively comprehensive. As an evening’s entertainment, it was ghastly.

Fast-forward to tonight, when the Mets doubled down on last night’s ineptitude by being terrible at everything. As did the Cubs — this was one of the worst baseball games I’ve seen in a couple of years, with both teams trying to one-down each other.

The Mets have good starting pitching, though that wasn’t in evidence tonight. The bullpen shows some promise, though Terry Collins‘ handling of it remains execrable. But they can’t hit, they can’t play defense, they can’t run the bases, and unless one of the intriguing young pitchers is front and center, they’re deeply boring to watch. The best moment of the night? It was Keith Hernandez remarking that “Murph is thinking he’s invisible again.” That’s one of Keith’s best lines of the year. (Update: The line is actually Wright’s, in a welcome departure from uttering Jeteresque nothings.) Too bad it was wasted on this farce.

To purge your system of the latest evening of horrible boring baseball, some reading material:

First off, check out this Joe Posnanski piece about the Oakland A’s. It’s not about sabermetrics or Moneyball or anything else that scares some of you. It’s about things that are much simpler: patience, and sticking to your guns. As Posnanski writes, “it’s not about KNOWING things others don’t. It’s about ACTING differently from other teams.” When the A’s make decisions, they do their best to make dispassionate ones, without snap judgments, groupthink and emotional baggage. It’s how they gave Josh Donaldson another chance despite his having failed in two previous appearances with the team. It’s how they saw past Tommy Milone‘s underwhelming fastball to his scintillating strikeout-to-walk ratio, made up their minds about him and then stayed with their decision. It’s how they plucked Scott Kazmir from the discard pile — Posnanski quotes Director of Baseball Operations Farhan Zaidi as saying that “we chose not to be bothered by his history.”

The card that started it all. Here’s another one for you: former Met C. J. Nitkowski all but pleading for the Mets to scrap three decades of La Russan bullpen dogma in favor of using their best relievers when the situation dictates and not getting hung up on closers or all the roles that follow, like dominos, from naming one. It’s a great idea, but unfortunately Nitkowski’s argument contains its own rebuttal: “It takes the right personnel and the right manager, but the Mets have that here and they could start a trend that may change baseball.” Yes, the Mets have the right arms. But they don’t have the right manager — I think Collins deserves more credit than he gets for being a good clubhouse skipper, but his in-game moves are aggravating Pleistocene stuff. He fetishes sacrifice bunts that decrease the team’s chance of scoring, had to be threatened into playing kids instead of Proven Veterans (TM), and is as boringly conventional as possible when it comes to bullpen roles. (Look at tonight, when he turned to retread Dana Eveland with the game on the line because it was an early inning, or something.) The Mets are indeed in a good position to try something new: They’ve got a passel of young flamethrowers who haven’t been around long enough to throw hissy fits about when and how they’re used. But unless they suddenly trade for Joe Maddon, conventional thinking is going to rule all, and the opportunity Nitkowski see will pass them by. Baseball’s going through a fascinating period in which smart front offices are searching for an edge with everything from pitch framing to defensive shifts, but the field generals are still largely from the school of Will to Win and other Just So Stories.

* * *

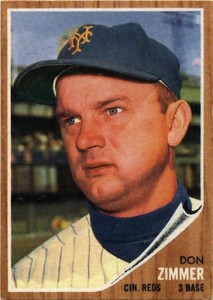

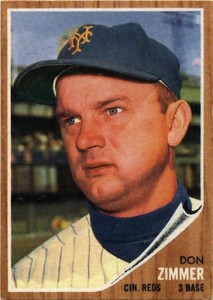

You probably heard that Don Zimmer died tonight. Zim hit .077 for the ’62 Mets, which was bad enough to get him shipped out of even that lowly outfit. I’m too tired to do him justice — I’m sure Greg will do the honors far better than I could — but I’ll add one personal note. And that’s to say that The Holy Books are sort of Zimmer’s fault.

My original goal was pretty straightforward: I wanted to collect all the Topps Mets cards. And I was making steady progress when I happened on Zimmer’s 1962 card, in which he’s wearing a Mets cap but we’re told he plays “3 BASE” for the “CIN. REDS.” (Topps paid homage to this a couple of years back by shooting David Wright from the same angle for Topps Heritage and making him a Red 3-Baseman.)

A player in a Mets cap is a rare sight in ’62 Topps even for guys actually identified as Mets — Topps mostly used hatless shots taken with the new Mets’ old clubs — so when I discovered the Zimmer card I had to have it. I puzzled over what to do with it for a while: It wasn’t a Met card, but Zimmer was obviously a Met on it, which was an interesting conundrum. Eventually I stuck it in a binder by its lonesome. Then, one by one, I started putting aside other ’62 Mets who’d never gotten Mets cards: There was Zimmer’s fellow Met/not-Met Bobby Gene Smith, whose cap was at least up at a logo-less angle, as well as Herb Moford, Sherman Jones, Joe Ginsberg, Dave Hillman and other immortals.

That led to collecting Mets without Met cards in other years beyond ’62. And then to deciding I needed all the Topps cards of anybody who’d ever been a Met. (Ouch to Willie Mays and Yogi Berra, and that was before I discovered Al Weis shared a rookie card with Pete Rose.) And then to finding cards of guys who never got a Topps card, and then to making cards for guys who never got any card, and most recently to making Mets cards for guys who should have had one. It’s a rabbit hole I’m still falling down, and it all started — as did so many baseball tales — with Don Zimmer.

by Greg Prince on 4 June 2014 9:52 am It’s not surprising that they lost. Losing is what they do. They’ve lost more often than they’ve won as a matter of course for five going on six seasons.

On May 31, 2009, buoyed by a week of having played teams who seemed indisputably lousier than them (Washington and Florida), the New York Mets stood seven games above .500, at 28-21. Those were the Mets forecast by Sports Illustrated to win that year’s championship, the Mets who came off campaigns in which they nearly made the World Series once and the playoffs twice. Those were the Mets who, dating to September 16, 2005, had been on a regular-season roll of 314-237; for 551 games, collapse-saddled notoriety notwithstanding, they played at a .570 pace, or the equivalent of a 92-70 record in 162-game terms.

On June 1, 2009, the Mets landed in Pittsburgh to play three games against another team that seemed indisputably lousier than themselves. They lost all three and were on their way to being a team that seemed indisputably lousier to fans of other teams. The Mets’ record from 6/1/09 forward, including Tuesday night’s entirely predictable loss in Chicago: 374-443, a clip of .458, good when compressed to 162 games for a mark of 74-88…the Mets’ final-season record in 2012 and 2013.

The 443rd loss in this 817-game span followed a nice, albeit short stretch that consisted of four wins out of five in Philadelphia, two of three at home against Pittsburgh and the salvaging of a doubleheader versus Arizona for a total of seven victories in nine attempts. Those clubs, like last night’s opponents, the Cubs, seemed either indisputably lousier than the Mets or certainly no better as their respective series approached. A really good team would make hay…should make hay when the schedule hands them such a slate. A pretty good team is supposed to prevail reasonably handily in these circumstances.

Since starting with the Diamondbacks on May 24, the Mets have gone 7-5, indicating that maybe they’re the class of a blah lot in the squishy sub-middle of the National League. Only two teams in the N.L. appear marooned impossibly far from contention in 2014: the D’Backs and the Cubs. The foul, fetid, fuming, foggy, filthy Philadelphians don’t look like much, either, but they sit only five games out of a Wild Card spot on the morning of June 4. Our predictably futile Mets are but two out of the playoffs even as they wallow two games under .500.

All of this is to say the sample size that encourages a person in the very short term has a hard time competing with the long-term trend that has served to suffocate that same person’s ability to gather enthusiasm. By my own calculation, I’ve watched or listened to at least part of every game but two the Mets have played since June 1, 2009. I’ve seen or heard them lose a clear majority — 54.2% — of those contests across a half-decade. Sometimes they surprise me and win. Precedent generally dictates a lack of optimistic expectation on my part.

Before Tuesday night fully revealed its nefarious intentions, I expected a Met loss at Wrigley Field. Not all day, mind you. Not because destiny insists the Mets lose. I’m not necessarily that much of a fatalist. That’s more the Cubs’ thing, anyway. No, I didn’t expect the Mets to lose at Wrigley Field until the game was up to its fifth batter.

Matt den Dekker led off the first inning with a single. Terrific.

Daniel Murphy was robbed on a line drive to third. Oh well. It happens.

Den Dekker stole second. Beautiful!

Den Dekker took third on a wild pitch. All right, here we go…

David Wright walked. Good, good, keep it going…

Curtis Granderson flies to center to bring home den Dekker. An out for a run, OK, it’s the first, and he did hit it hard…

Chris Young is up.

Fifth batter. Jake Arietta had not looked at all good for the first four, yet he was one Chris Young from escaping with a 1-0 deficit. Arietta didn’t require a double play here, which was fine for him. A pitcher’s best friend traditionally may be the double play, but an opposing pitcher’s best friend these days is Chris Young.

Chris Young flied to left for the third out.

We’re probably screwed.

Zack Wheeler comes out and shoves in the bottom of the first. Wheeler’s dealing so masterfully that when the Cubs go three up, three down, I’m thinking that one run might be sufficient support for him. I’m thinking one hit might be impossible for Chicago to attain. I’m thinking in ways I’m somehow still capable of thinking despite the Mets having lost 442 of their previous 816.

The top of the second arrives. The first two Mets reach base. Neither of them reach home.

In the bottom of the second, Wheeler’s no-hit bid goes awry when his sixth batter, Nate Schierholtz, singles. I shift into Nancy Seaver mode from July 9, 1969, accepting Tom’s spousal assurance that a one-hit shutout is a worthwhile outing, too. Wheeler’s so good early that why would I think 1-0 won’t hold up?

In the top of the third, more cushion for Zack is on order: Murphy singles, Wright walks, Granderson — I’m thisclose to calling him Grandy — singles. Murphy’s on third. Wright’s on second. Curtis is on first.

The bases are loaded. There’s nobody out. The cushion store calls to say the merchandise we requested is out of stock.

If Foxwoods Resort and Casino still had a Turning Point of the Game, this would be the one to wager on. Because I know…I just know that another run should have occurred by now…and I just know another run isn’t going to.

Young hits a ball to the right side of a Cub infield that’s playing back. Murphy, celebrated as grand exemplar of the modern family man, orphans the Mets’ chance to take a 2-0 lead. He’s not running on contact, he’s forced at the plate, he makes the first out. Lucas Duda does what is most accurately described as nothing for the second out. Wilmer Flores lines a bullet, just like Lamar Johnson coached him to, but Arietta intercepts it midflight.

Jake Arietta has been strafed for three innings and still hasn’t given up more than one run. Zack Wheeler will issue no more than a harmless walk in the bottom of third. A leadoff single from Travis d’Arnaud won’t go anywhere of note in the fourth. Wheeler will retire a side of Cubs immediately thereafter. Arietta will give way to Jayson Werth döppelganger Brian Schlitter once he’s put two Mets on with two out in the fifth. Schlitter whiffs Wilmer to keep the game, 1-0.

We’re still probably screwed.

A Schierholtz single goes for naught in the home fifth. Schlitter squelches the Mets altogether in the sixth. Wheeler’s spotless again. James Russell enters in the seventh, gets two out, gives up a base hit to Grandy (!), then can leave his glove on the mound for all it matters because Young is up next and due to strike out whether someone throws him three pitches or not.

Wheeler still has that 1-0 lead. He strikes out Anthony Rizzo, he grounds out Starlin Castro and gets ahead of Luis Valbuena 0-and-2. That he issues four consecutive balls to conclude the plate appearance is more troubling than it should be. It shouldn’t be a big deal because when Zack is immediately and correctly pulled with lefty-swinging Schierholtz looming, he’s pitched something very close to a gem. In 6⅔ innings, encompassing 107 pitches, he’s struck out seven Cubs, surrendered just two hits to nagging Nate and allowed only two walks. But something about that last one, to Valbuena, after being so definitively ahead on him…it was another reminder, like all the stranding on which Arietta and the Met offense had collaborated, that this game should have been safely projected in the New York column by now. Instead, exit polling was inconclusive and we were still waiting for key precincts to come in.

Historically speaking, Chicago’s the last place where you want to rely on late votes to decide a close outcome.

Josh Edgin preserved the 1-0 lead for Wheeler by fanning Schierholtz. The Mets didn’t score in their half of the eighth. The Cubs, however, did. Chris Coghlan homered off a lefty, Edgin, for the first time in four years. The last lefty he dinged? 2010 Met Oliver Perez. Edgin and Vic Black got out of the eighth with the game still tied.

It was still tied. It had been led for so long, now we were grateful it wasn’t actively being lost.

Instead, it was subtly being lost. The top of the ninth ended on a double play, leaving the total of Mets baserunners who never saw home at 10, the Mets’ output with runners in alleged scoring position at 1-for-9. The bottom of the ninth then produced a result so predictable that the Cook County Board of Elections would have been impressed. The prohibitively lousy Cubs arose from their presumed graveyard and beat the recently rolling Mets, 2-1. David Wright, the one Met who has stood head and shoulders over long-term lousiness since 2009, couldn’t turn a turnable double play. Nate Schierholtz, the one Cub who troubled Wheeler, got the winning hit off Scott Rice, despite Rice being a lefty, which is the skill that explains his continued existence in a Met uniform. That somehow wasn’t surprising, either.

I had a feeling we were screwed in the first, was fairly certain by the third, had that sense reinforced in the fifth and couldn’t have been convinced to bet against it in the seventh. I just knew the ninth would unravel more or less as it did.

So did you, probably.

|

|