The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 19 November 2013 12:30 pm When a bargain ceases to be a bargain, then it’s just business. LaTroy Hawkins was a baseball bargain in 2013, getting paid a paltry (in the business where “paltry” is a highly relative term) million bucks for his Metropolitan services. He proved so valuable, he earned himself a nice raise.

Too nice to remain a bargain and too nice to remain nearby. Hence, the man who issued only 10 walks in 72 appearances took a walk himself, clear to Colorado where he projects as the Rockies’ closer for 2014. The million bucks has multiplied by two-and-a-half. The impulse is to say good for LaTroy — one of the swell guys of the game by all accounts, at least until those ever-present “Mets people” whisper from the shadows that he always hogged two parking spaces — and, in a way, good for the team that let him walk. Hawkins was reborn as an effective late-innings pitcher at the age of 40. What are the odds he’s gonna stay vital at 41? I’m a sucker for a heartwarming endurance story, but the Mets used to extend veterans who had given them one wonderful year just enough to make fans of all ages regret the decision.

On the same day Hawk flew to Denver, I noticed the Padres appointed Jose Valentin their first base coach. Valentin was a scintillating second base surprise for the 2006 N.L. East champion Mets, socking 18 homers for a below-market rate of a shade over $900,000. When his minor miracle season was over, Omar Minaya reward him with a contract for 2007 for more than four times as much. As if on disappointing cue, Jose Valentin slumped and did not finish out 2007, never to play in the majors after that July. (Somehow Minaya resisted the temptation to slip him a long-term deal; he saved that gem for the about-to-be acquired Luis Castillo.)

I’m also inclined to assume almost all relief pitchers are best recycled before they degrade. Your elite closers and your lefty specialists you might want to hold onto. Everybody else answering to the job description of “long reliever,” “middle reliever” or “setup man” seems a perennial candidate for eventual promotion or benign expulsion. It’s just the nature of the non-Rivera beast that getting attached to an arm for one season too long can lead to a particularly horrendous case of heartbreak.

But I would like to back up to LaTroy’s $2.5 million payday. If — if — Hawkins remains reliable for the Rockies, that’s not a lot to pay a closer. Even if the Rox rearrange their pile of pitchers and assign Hawkins the eighth inning and the righty retires batters in that role, that’s not a lot, either, not if the goal of the team is winning every game possible, not just getting through another sub-.500 campaign.

Should the Mets have attempted to match the Rockies’ offer to LaTroy Hawkins? For the reasons stated above, probably not. But devoting a suitable sum to a key cog on a major league ballclub — and as we’ve been reminded repeatedly over the decades, scoreless sevenths and eighths are pretty damn key to attaining victory —doesn’t always add up to Minayan madness. The average MLB player salary edges relentlessly upward; last year it was approaching $3.5 million. If you can get away with something cheaper as the Mets did for the innings they squeezed out of Hawkins and the hits they derived from Marlon Byrd ($700K), fan-freaking-tastic. There are budgets and strategies and dozens of contracts to take into consideration. Don’t throw money away if you don’t have to.

But geez, I hope the Mets weren’t overcome with the shakes that an experienced pitcher coming off a fine year was compensated well. I hope this doesn’t touch off another round of recriminations about how “scary” it is to pay for quality.

I hope the Mets find some good players, mostly. And I hope they don’t hide (or aren’t forced to hide) behind a new line of fiscal barriers and consign us to another season when the competitive lights are dimmed by August. Not having a Cano for more than dinner conversation is one thing. Not devoting sizable resources to a Choo or an Ellsbury is seated at the same supper as that one thing. But if we’re uncomfortably slinking away from the table that hosts the possibility of a Peralta or a Cruz…

Please serve us up somebody who will help us win measurably more games than the number to which we’ve become uncomfortably accustomed is all I’m asking of the Met waitstaff…y’know?

One other thought on Hawkins and Byrd: When Terry Collins was moving toward his inevitable naming of David Wright as captain in March, he mentioned that he planned to talk to both of those guys to get their input. Neither one had ever been a Met before Spring Training (and neither had played for this manager elsewhere) but Collins explained both men had been around, both saw how things operated in a plethora of clubhouses and he wanted to hear what they had to say on the subject of captaincies. Apparently neither LaTroy nor Marlon vetoed the idea.

Eight months later, neither player is a Met. I’m guessing new versions of wise old hands will materialize in St. Lucie, and if they stick with the team and make contributions, their comparatively callow teammates will swear by their humanity and the skipper will attest to their wisdom and we’ll feel good about those guys until they, too, have to get going. To a degree, that’s how the “industry” works for most players who cross to the far side of the rainbow. Only a handful of players receive the kind of eight-year contract David Wright was offered, and precious few don’t make you at least partially rue the dotted line on which it was signed.

I have no real actionable agenda regarding the circle of baseball life, except it does leave me to wonder if someday the Mets will keep somebody besides Wright around long enough to grow into a wise old hand on their watch.

The Mets signed a catcher to a seven-year, $91 million contract fifteen offseasons ago. On the night of June 30, 2000, it felt like the deal of the century. Watch here as Jason and I join a joyous SNY panel in recalling the eighth inning that produced ten runs of Braves-beating fun.

by Greg Prince on 17 November 2013 3:50 pm Sure, you could’ve sent Tom Seaver a birthday card today — or at least written “Happy Birthday, Tom” on a Post-It note and stuck it to the cork atop a bottle of GTS Cabernet Sauvignon en route to toasting the Franchise — but there’s a better way to greet the day the Met who gave us 25 wins in ’69 turns 69.

Scroll toward the bottom of Baseball-Reference’s most Terrific player page and treat yo’self to the portrait of a leader…a pitching leader.

Tom Seaver pitched 20 big-league seasons. In how many of those, do you suppose, did he not finish in the Top 10 of some positive pitching category? Well, there was 1982, when he was dealing with injuries in Cincinnati. Then there was 1986, when he was approaching the end of the line between Chicago and Boston.

And that’s it. There were TWO years when Tom wasn’t among the 10 best pitchers in his league at something related to his craft and EIGHTEEN when he was. Usually he appears among the leaders multiple times for a given season and often he leads all of his alleged peers. Most of that leadership was accomplished as a Met. Some of it came as a Red. A bit of it was saved for the White Sox. All of it, regardless of uniform, speaks to an immortal.

Says “Happy Birthday” to him, too.

by Greg Prince on 16 November 2013 8:46 pm Twenty-five Mets said hello on Opening Day, April 1. Twenty-two of them said some variation on goodbye — whether it was farewell, so long, see ya later or be back in a bit — before Closing Day, September 29. Let us review how 88% of the 2013 Mets stopped or at least paused being 2013 Mets as the season wore on and on and on.

April 7: Jeurys Familia optioned to Las Vegas.

April 17: Greg Burke optioned to Las Vegas.

April 23: Kirk Nieuwenhuis optioned to Las Vegas.

April 27: Josh Edgin optioned to Binghamton.

May 3: Collin Cowgill optioned to Las Vegas.

May 14: Scott Atchison placed on disabled list.

May 30: Ruben Tejada placed on disabled list.

June 10: Ike Davis optioned to Las Vegas.

June 10: Mike Baxter optioned to Las Vegas.

June 18: Justin Turner placed on disabled list.

June 21: Jon Niese placed on disabled list.

June 23: Lucas Duda placed on disabled list

July 5: Brandon Lyon designated for assignment.

July 14: Jordany Valdespin optioned to Las Vegas.

August 3: David Wright placed on disabled list.

August 7: Bobby Parnell placed on disabled list.

August 11: Jeremy Hefner optioned to Las Vegas.

August 17: John Buck placed on paternity leave.

August 20: Anthony Recker optioned to Las Vegas.

August 27: Matt Harvey placed on disabled list.

August 27: Marlon Byrd traded to Pittsburgh.

September 9: Scott Rice placed on disabled list.

These, mind you, weren’t necessarily the only transactions attached to the players who failed to stick like glue to the active roster. For example, John Buck’s paternity leave didn’t last nearly as long as his paternity leave watch…but before the youngest Buck could learn to crawl, John was traded to Pittsburgh. Greg Burke would be recalled, but never long enough so that we could recognize him by face. Lots of frequent flier mileage for that fellow. Jeurys Familia battled long and hard from injury so he could rematerialize in September…and wind up getting racked around for his trouble. Scott Atchison toughed it out through a pair of DL stays no matter that he was widely presumed more decrepit than disabled. Jeremy Hefner’s transaction to Triple-A was mostly paperwork, but the injury that briefly made him a 51 86’d him for the year.

Niese? Hurt for a spell. Duda? Hurt, then forgotten until he had to be remembered. Davis was just bad, then maybe not so bad, then hurt. Tejada: bad, hurt, hurt again. Parnell good, but hurt. Valdespin: ludicrous, ineffectual, suspended everywhere but on Instagram. Cowgill: he was a thing, but not for long.

Indeed, resolutions differed for the 22 Mets who didn’t go wire to wire, even the few really good ones. David Wright returned as soon as he could, which wasn’t very soon. The Mets’ All-Star third baseman strained his right hamstring in the club’s 107th game of the year and wasn’t back until their 153rd. Wright wound up playing in fewer games than Marlon Byrd, who proved such a revelation that the non-contending Mets cashed out and shipped him with Buck to the Pirates for their stretch run. The Mets received youth in exchange, necessarily giving up on a slice of the present that had unexpectedly kept on giving.

And then there was Matt Harvey, the best and most exciting Met of 2013. He came in fourth in the National League Cy Young voting. He might have come in as high as second had his elbow not begun giving him trouble. No bad elbow, no making his last start on August 24. From maybe Cy to definitely sigh.

In between Aaron Laffey replacing Familia on April 7 and Wilfredo Tovar being inserted into emergency action on September 22, there was all kinds of traffic. Some of it got your attention for reasons beyond rubbernecking. Juan Lagares made you wish balls would be lined deep to center so we could revel in how he tracks them down. Eric Young was a welcome burst of pure energy. Zack Wheeler hinted that well-nurtured prospect dreams might come true. Competent relievers manned middle innings. Young hitters took promising cuts. Much of the churn, however, was as disposable as a 74-88 campaign prosecuted by 53 different players would suggest.

In the midst of the flux and the turnover and the fifth consecutive season when losses outnumbered wins and hopes for contending never more than flickered, three Mets stood firm. They weren’t the most talented, they weren’t the most productive and they weren’t the most marketable, but they were there day in and day out, night in and night out.

On these Mets that was plenty impressive. Thus, Faith and Fear in Flushing is reasonably proud to announce Daniel Murphy, Dillon Gee and LaTroy Hawkins as tri-winners of its coveted Most Valuable Met award for 2013. If it were a real award, we’d be confident they’d show up and accept it in person.

If there’s one thing you can say about these guys after 162 games in their company, it’s that they don’t have a problem showing up.

The decision to single — or is that triple? — out Murphy, Gee and Hawkins, though it’s based less on spectacular performance than it is on exemplary attendance, shouldn’t be taken as faint praise or merely the result of the process of elimination (which is something every Met year since 2009 has boiled down to by August). The Stalwart Three didn’t play dodgeball from April through September. They didn’t cleverly huddle in the back of the gym simply eluding disaster. They were out front for their team, and if they didn’t always excel, they certainly didn’t embarrass.

Also, they didn’t get injured, which always helps. Murphy lost all of 2010 and too much of 2011 to injuries. Gee missed the second half of 2012. Hawkins? Being 40 was enough of a health risk. Yet there they were at the end of the season having survived as the only three iron men on the premises.

Daniel Murphy played in 161 games, 40 more than any other Met (Lagares). Dillon Gee started 32 times, a half-dozen more than any of his fellow Met pitchers (Harvey). LaTroy Hawkins threw 70.2 innings in relief, almost 20 more than any of his Met pen mates (Scott Rice). Each Met in question wasn’t just durable but dependable.

It wasn’t crazy as the year took shape to believe Murphy could be an All-Star alongside Wright and Harvey when Citi Field grew stellar in July. Daniel was batting .300 as May ended, maintaining his clip in dramatic fashion during the Subway Series four-game sweep. On the first night of the New York-New York showdown, he drove in the go-ahead run in the eighth inning off David Robertson. On the second night, he led off the ninth with the ground rule double that sparked the two-run rally that vanquished Mariano Rivera. There would be some tailing off in June — perhaps a consequence of Terry Collins briefly redeploying him as a first baseman as part of larger team shakeup — but Murph of the Metropolitans (he may be the only Met ever to relish identifying himelf so formally) recovered, hitting .306 from July 6 on. He didn’t so much streak as gather hits in clumps. When he slumped, it was never long or brutal enough to label it fatal.

There are some juicy cherry-pickable statistics to be plucked from Murphy’s portfolio: second in the National League in hits; seventh in doubles; eighth in runs scored; a surprising seventh in stolen bases (23 — a total he attributed to his reputation as a “slow white guy”); an almost shocking second in putouts and third in assists among N.L. second basemen. Much of this success, which admittedly overlooks some of the shortcomings of his game, is a product of going out there every day and participating to the best of his ability. If hanging in there and handling the offensive and defensive demands of an everyday second baseman was easy, maybe the second-longest tenured Metropolitan (behind only Wright) wouldn’t stick out for having done exactly that in 2013.

As midseason approached, the best that could be said for Gee was that with Wheeler’s promotion imminent, maybe Dillon could come in handy in long relief. For almost two months, he was the weakest of links in the rotation, bottoming out on May 25 with a five-inning, five-run Citi Field shellacking at the hands of the Braves. That start, his tenth of the year, left his ERA at 6.34 and shoved him behind the likes of Jeremy Hefner and Shaun Marcum in the Met pecking order.

Then, everything changed. Starting with his final start of May, the night the Mets would complete their sweep of the Yankees at Yankee Stadium, Gee began his transformation from hoped-for innings-eater to dangerous batter-devourer. Pitching into the eighth (when he was removed by an overly nervous manager), Dillon scattered four hits, allowed one run and struck out twelve. The template was set for a startling turnaround.

From May 30 through September 26, encompassing his final 22 starts, Gee was a rock: 10-5, 2.71 ERA, 1.132 WHIP, lasting fewer than six innings only once. Say what you will about individual pitcher wins, but Dillon was the only Met to come away from 2013 with a number in double-digits, finishing 12-11 overall. He also led the team in innings pitched with 199, a point of consternation for him when he was removed from his 32nd start one inning shy of his goal of 200. It wasn’t a wholly arbitrary standard. Dillon Gee couldn’t be sure what he’d be able to do this year given that he didn’t pitch after the All-Star break in 2012. He wanted to compete to the very last possible inning in 2013. It’s not something many Mets have managed to do come the Septembers of this era. It was beyond admirable that it was of overriding importance to Gee. “I never want to come out of a game,” he declared, left to mine satisfaction from being the only Met starter who didn’t miss a turn all season.

If the Mets couldn’t have projected Murphy or Gee assuming statistical leadership as everyday players and starting pitchers, nobody would have guessed that as August rolled around, the Mets closer — on those occasions when they needed one — would be LaTroy Hawkins, heretofore Bobby Parnell’s setup man. The promotion from the eighth to the ninth was one he certainly didn’t demand but dutifully filled. Parnell had been one of the pleasant developments of the first half, but after showing signs of breaking out, he felt a pain in his neck. His year ended with a third of the schedule yet to be played.

Enter (after a failed cameo by David Aardsma) the Hawk, who didn’t exactly swoop in with glee. LaTroy understood he was signed to serve not just as a pitcher but as a mentor. As the season was concluding, he mentioned the veterans who taught him the ropes when he was a neophyte Twin in the 1990s. One of the names belonged to Rick Aguilera, then the resident closer at the Metrodome, a decade earlier a building block of great Met things to come.

Now, in his own baseball autumn, LaTroy Hawkins hoped he could set an example for the Parnells, the Gonzalez Germens and the Vic Blacks who were following in his footsteps. Whatever words of wisdom he offered were more than backed up by what he demonstrated from the mound. Hawkins had exactly zero saves through four months of the season. Beginning August 6, he compiled 13, blowing only one along the way. It wasn’t the plan to send a 40-year-old right arm to pitch so many ninths, but he became the best possible option and he didn’t disappoint. When 2013 was over, Hawkins had saved more games, logged more innings and chalked up more appearances than he had in any season since 2004.

Back then, he was the Cubs’ closer. That September, Mets fans knew him (gleefully) as the pitcher who gave up an instantly legendary game-tying ninth-inning home run to Victor Diaz. Diaz wouldn’t pan out and eventually be traded for Mike Nickeas. Nickeas wouldn’t do much and eventually be thrown in with R.A. Dickey to obtain Travis d’Arnaud, Noah Syndergaard and John Buck. Buck would be traded for Black, who earned his first major league save on a night in September when Hawkins needed a rest. LaTroy gave Vic his blessing, having played catch with the kid between outings. “Some guys,” Hawkins told the Star-Ledger’s Jorge Castillo, “have late life on the ball.” Hawk was referring to his latest protégé’s 97-MPH stuff, but at the tail end of his nineteenth big league season, he had proven himself an authority on late life.

When the Baseball Writers Association of America announced its National League Most Valuable Player voting for 2013, no Met came up in the conversation, not even as a whisper. Twenty-four players received votes. None of them was named Harvey, Wright or Byrd, the Mets who had put up the gaudiest numbers among Mets while they were still available to do so. It was the first year since 2009 (and the nineteenth in franchise history) that no Met collected as much as a point from the BBWAA MVP-makers.

There wasn’t much gaudy about Murphy, Gee or Hawkins, certainly nothing that would catch an out-of-town baseball writer’s eye at awards time. If the year recently completed had gone much better — and if certain hamstrings and elbows had remained intact — we’d probably be using this platform to praise the obvious standouts, not the obstinate stalwarts. A more fortunate collective than the 2013 Mets would have enjoyed the benefit of Harvey and Wright clear to the finish line. A markedly better bunch than the 2013 Mets would have employed the services of Byrd for six full months, maybe (as Pittsburgh did) a seventh.

That wasn’t the team we had.

We did, however, have the team that for a tenth consecutive season didn’t miss a single game. The last time the Mets left a contest unplayed was August 14, 2003, when a blackout blanketed Shea Stadium and the home team was prevented from taking on the Giants. The stabs at rescheduling — which had to take San Francisco’s playoffs and Bruce Springsteen’s concerts into consideration — proved too complicated to allow for a makeup. Since then, if the Mets have a game on the docket, they play it. If they have a rainout or a snowout or an electrical snafu, they sooner or later find a way to plug the innings back in.

Thus, the Mets keep showing up as a unit, no matter their components, and we keep showing up as Mets fans because it’s what we do. We show up when we think the Mets are going to be good and we show up when we’re sure the Mets can’t get any worse. We appreciate those who keep showing up for us and with us. It’s why we appreciate an iron triumvirate like that formed by Daniel Murphy, Dillon Gee and LaTroy Hawkins. They weren’t often the best at what they did, but each of them outstripped their projections and they all remained unshakable constants on a team that otherwise felt like it was staffed by a temp agency. They were there at the beginning, they were there in the middle and they were at the all-too-familiar bitter end.

You’d better believe there’s value in that.

FAITH AND FEAR’S PREVIOUS MOST VALUABLE METS

2005: Pedro Martinez

2006: Carlos Beltran

2007: David Wright

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Pedro Feliciano

2010: R.A. Dickey

2011: Jose Reyes

2012: R.A. Dickey

Still to come: The Nikon Camera Player of the Year for 2013.

by Greg Prince on 12 November 2013 8:45 pm I’m still trying to confirm that Veterans Day has an April Fools component to it, because the bit I read Monday about the Braves moving out of currently 17-year-old Turner Field three years from now makes for quite the doozy, the whopper and the priceless gag. Hats off, fellas, I wanna say.

But it’s apparently real, not just real weird that a ballpark that opened in the same generation that spawned still relatively new Citi Field is going to disappear from the Mets’ schedule before it can celebrate a 20th anniversary. That’s the plan, anyway, and the plan isn’t just drawing-board spitballing. It’s as done a deal as these things can be without being done. The Braves have their spot picked out. The commissioner’s on board. The mayor whose municipality is being abandoned doesn’t seem terribly upset. Though you can find dissenters as easily as you can find a comments section, the general reaction by those who root for the team involved doesn’t indicate mass outrage. The Braves specified some reasons for the shift — impending maintenance costs, stubborn traffic flow, fan base residency — and, well, there it is. See y’all up Cobb County way in 2017!

It’s still real weird. The one thing I haven’t read in any of this is a complaint about Turner Field. I don’t mean our “why can’t the Mets ever win there?” complaints about Turner Field, dating back to when the park still carried an echo of its Olympic beginnings and the Mets constantly settled for silver, but an actual problem anybody has with the place itself. At worst, Turner gets dismissed as sort of ordinary: too big to be intimate, not idiosyncratic enough to be charming, no longer new enough to be novel. My one in-person experience with it found it quite ideal for a Sunday afternoon of baseball. I’m not sure if that counts as “fan experience,” but it worked for me in April of 1998.

Granted, time flies like Marlon Byrd. 1998 was to Turner Field what 1965 was to Shea Stadium, just its second year of operation. Nobody in 1980 New York was leaning on the World’s Fair era to appraise Shea Stadium, which is the chronological equivalent of where the Ted is in 2013. As it happens, the home of the Mets had just received its first genuine facelift in its 17th season on the job. Imagine Nelson Doubleday or his highly limited partner Fred Wilpon had stepped up in November of 1980 and said, “We’re leaving Shea for somewhere nearby come 1984.”

Actually, that might have won some plaudits considering Shea lacked for maintenance in the 1970s, which is why the paint job and reseating of 1980 was so welcome. Nevertheless, it was inconceivable that the Mets or anybody else would’ve had a spare stadium deal up their sleeve less than two decades into the life of the current one. It was enough to get Shea to start draining better and maybe install some artificial turf (a plan that was announced and thankfully forgotten post-Jets).

I’m trying to summon some objective-observer dismay over what the Braves are doing, because giving up a perfectly lovely 17-year-old ballpark is so counterintuitive, but it’s not coming. The smooth sailing toward Atlanta’s Cobb County conclusion seems almost gentlemanly when compared to most other stadium replacement transactions. Strip away a few phrases of nonsense about how Some Company’s Name There Field will contain amenities for the ages (they’re already referring to the unbuilt facility as “world-class,” which we should recognize as code for catering to the luxury lounge crowd), and this move — from a distance — sort of makes sense.

Whatever isn’t wrong with the ballpark “experience,” it’s fair to include travel as part of your day or night out. If negotiating Atlanta traffic is intimidating enough to keep customers from spending their time and money at the Ted, and you’re responding by creating a less onerous path to the park by setting up shop closer to the most optimal Interstate interchanges, then I suppose going to see the Braves just became a better experience. If your best P&L estimates factor in maintenance as a going concern — something the Cubs traditionally understood while the White Sox never did, which is why there’s still a Wrigley Field after 100 seasons but Comiskey Park expired after 81 — and you can plan accordingly amid your prospective sweetheart deal, maybe you won’t have to kick this stadium to the curb c. 2037

Or maybe you will anyway. Maybe the Braves, whom despite my divisional animus for them I’ve generally considered a Cardinals Lite in terms of organizations that know what they’re doing, are innovators here. Maybe this is just what we do as a society. We pay lip service to landmarks but we can’t wait to do it over an ever newer phone. Commercials encourage us to drop our digital devices in crappers and such so we will feel entitled to purchase the model that emerges next week. Nothing’s wrong with the old one. It’s just not as astounding as the one we could have.

I guess Turner Field isn’t, either.

Yet this development continues to be weird. Choosing a ballpark site based strictly on driving considerations strikes me as sadly retro. The Braves didn’t like that Atlanta’s version of a subway, MARTA, didn’t make a stop directly adjacent to Turner Field. Indeed, as I discovered on my lone pilgrimage, I had to get out somewhere and hop on a free shuttle bus. It wasn’t a biggie. Now they’re going somewhere that has no MARTA — not just the stadium but the entire county. It’s also a little strange to watch a team pack its bags in the city and ship them to the suburbs, reversing the tide of history that began in earnest when Camden Yards opened in 1992.

One size doesn’t necessarily fit all regions, however. What worked beautifully in Baltimore, Cleveland, Denver and some other urban landscapes didn’t exactly click in Atlanta, where the Braves have been right around the heart of the city since 1966. I’ve read their location described as south of downtown, leaving it shy of where the action is. Turner Field going up next to where Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium was didn’t ignite neighborhood growth or complement anything that was in progress. Though the previous joint was demolished to provide parking for the current model, one of the plagues the Braves wish to leave behind is not enough spaces for cars. It’s a very anachronistic Connie Mack Stadium/Polo Grounds-style gripe.

The bulk of their ticket-buyers are in a different (more affluent) section of the greater Atlanta area? Bringing the ballpark to those people could be interpreted as the ultimate in home delivery, but it also underscores the inability of the Braves to matter to the people who’ve lived directly around them for 48 seasons. Those folks (less affluent) have had more pressing concerns than paying to go see a baseball game. It’s a shame it’s too expensive or not compelling enough an outing for those who could theoretically walk to Turner Field and simply buy a cheap ticket for their home team. The club has loads of data presumably born of credit card data regarding who antes up to attend. Remember when baseball was cash and carry and you didn’t have to carry all that much cash?

The Braves feature a map on their dedicated ballpark site to make it head-slappingly obvious that they should be where they’re going. You see such a large red blob surrounding NEW STADIUM that you can’t possibly imagine why they’d remain at Turner Field. I assume such a map is possible to construct and perhaps already exists to show the geographic dispersal of Mets customers. I doubt ZIP Code 11368 is where a plurality of us live but I assume it still functions all right as a hub. Nothing has ever developed around the Mets’ slice of Flushing, but the Wilpons seem determined to change that (their Metsville schemes have been disseminated, but call me when these real estate machers have a shovel in the ground).

Would the Mets be theoretically better served in their own version of Cobb County…which I would guess would be Nassau as opposed to Queens? I’m a Nassau County resident with the mortgage to prove it, but my answer would be no. I suppose if the Mets could figure out a way to erect a ballpark a town or two over from where I type, I’d hypocritically applaud their demographic foresightedness, but your team being from somewhere stable has got to count for something, at least in the land-line values system I instinctively call up. The Mets are from Flushing, a spot logistically accessible to all and just inconvenient enough to everybody. They d/b/a as the New York Mets. They belong in the City of New York, even if the bulk of their acolytes might have to schlep a little more than Braves fans will from 2017 forward.

Atlanta’s not New York (no kidding) and the Braves aren’t our problem, save for 19 times a year. I’d say good luck to them on their startling new venture except the Braves do fine without our well-wishes. Maybe they really are leading-edge on this issue. The Wrigleys and Comiskeys are exceptions. Just within the unfriendly confines of the N.L. East, Shea lasted 45 seasons, the Vet 33, Atlanta Fulton-County 31. The Marlins couldn’t wait to get out of the rotatingly named football stadium where they were shoehorned for 19 lonely seasons and the Expos had far less luck playing in an Olympian stadium for 28 seasons than the Braves ever did. Sooner or later, they all got vacated. Turner Field — despite providing more ideal baseball acreage than any of the above — is just choosing sooner.

The Braves like to tout their status as the world’s longest continually operated sports franchise, having been around in one form or another in one city or another in one stadium or another since 1871. Yet for all that longevity, they are a relentlessly itinerant operation. Boston was a problem because nobody came to their games. So they moved to Milwaukee. Everybody came to their games in Milwaukee until they didn’t. Within 14 years of arriving in Wisconsin they were Georgia-bound. Very few people were coming to their games in Atlanta, yet they forged a following far from the plethora of Peachtree Streets because their owner put them on a local TV station that wasn’t really local. They called themselves America’s Team, they moved into yet another stadium — their fourth in 46 seasons — and they seemed permanently set, or as permanent as the world’s longest continually operated sports franchise could be on the cusp of the 21st century.

Y’know what I remember being hyped as a really big deal when Turner Field opened? That beyond center field there was a wall of televisions beaming into the Braves’ ballpark every other game going on in the majors. As a Mets fan away on a business trip, I was delighted to leave my seat for an inning and turn my attention to a game going on at home. I wonder if the Cobb County park will have anything like that.

They probably won’t need such a contrivance. If people don’t want to pay attention to the Braves, they can just check their phones. Goodness only knows what they’ll be capable of showing you by 2017.

by Greg Prince on 7 November 2013 2:19 pm The Sunday after the All-Star break at Citi Field was one of those afternoons when All Is As It Should Be. Matt Harvey was punishing the Phillies. A Dwight Gooden bobblehead was nestled inside my schlep bag. What we used to call DiamondVision found a moment between highlighting Harvey strikeouts to feature the de facto guest of honor in the non-bobble flesh. A camera found Dr. K Emeritus taking in the game on the terrace of an Empire suite, no more pretentious about it than a fella sitting on the porch and watching the neighborhood kids play in the street. Our attention was directed to his whereabouts. He waved graciously. We applauded appreciatively. Some of us stood. I’m pretty sure I did.

Yes, I thought, All Is As It Should Be. The franchise that sees powerful righthanded pitching when it peers into the mirror in search of its inner beauty had two-thirds of its holiest trinity on hand. Harvey we’d been drooling over for months. He was on the mound, the only place we wanted him. Tom Seaver wasn’t around that afternoon, but he’d toed that rubber, albeit ceremonially, a mere five days earlier, so he was excused. Gooden, meanwhile, was ensconced in a place of honor, doing what he should be doing where he should be doing it.

Dwight Gooden was being our legend-in-residence. I don’t know that he can make a living at that, but if sitting, watching, rising and acknowledging the masses keeps him and his memory safe and secure, I’m all for it being a part of his and our Metscape.

One of the great, quiet victories of 2013 was the full reweaving of Dwight Gooden back into the Met tapestry. His recurring appearances in Flushing felt like the culmination of a bumpy five-year comeback trail that commenced on the most bittersweet day in Mets history — the Shea Goodbye sendoff that returned Doc to his native soil in proper garb for the first time since 1994 — and continued until you almost didn’t notice that the trail had led to an utterly unsurprising conclusion. He showed up for Shea Stadium. He showed up for his nephew Gary Sheffield. He showed up for his induction into the team Hall of Fame. He showed up for Banner Day’s revival. Eventually, he showed up for the hell of it. “Hey, Doc’s at the game tonight,” you’d now and then mention to your companion, pointing to where he was stationed and maybe at what he was doing.

Doc’s at the game. Where else would you expect him to be?

The Mets have several well-loved ambassadors who make community-minded appearances here and there, but they don’t really have somebody whose job it is to swing by and subtly remind you how great it can be to be a Mets fan (besides Matt Harvey, and he won’t be around much for the next year). They haven’t cultivated what Red Schoendienst is to the Cardinals or Don Newcombe is to the Dodgers or what Johnny Pesky was to the Red Sox — a sage without blatantly obvious portfolio whose very aura announces “Mets” when you catch sight of him. Someone who straddles celebrity and accessibility. Someone who knows the game. Someone who can talk to the players. Someone who can and will say “hi, how are ya” to the fans.

Gooden’s third autobiography really tells it like it’s been. Doc Gooden stopped himself a peg shy of irrefutable immortality on the field, but he definitely visited the stratosphere. He has a story worth telling, which he did in his third and presumably final autobiography, Doc: A Memoir, the most heartfelt and genuine of the trilogy. Beyond 1999’s Heat (not to mention 1985’s Rookie) this is the one that really lets you explore the mechanics of a troubled life and makes you realize avoiding the drugs that derailed his express train to Cooperstown was never going to be easy as Just Saying No. Doc has the power to sway you from “screw him, he threw it all away” to “he didn’t really grasp what was making him throw it all away.” Where the person is now won’t permit the pitcher to reset the clock on his career — when it felt like Gooden could go 24-4 24/7 — but the important thing is that the person has a future. I’d wholeheartedly welcome his future into our presence for as long as it keeps all concerned happy and healthy.

Book promotion probably helps explain why he was around Citi Field as much as he was in 2013, but given that he lives in the area, takes his second chance at eternal Methood seriously and still revels in his craft (if you heard him analyze Harvey with Kevin Burkhardt from the stands, you heard a master dissect a prodigy), the ballpark sure seems his natural habitat. A little waving, a little coaching, a little of whatever it takes to keep the tapestry intact.

With Doc onsite as often as possible and any luck, maybe somebody else will experience an encounter like I had in 2013.

This was a few weeks before that bobblehead afternoon. It was a Friday night when the Mets were frantically pushing for the naming of Brandon Nimmo to the Futures Game roster, a selection that was subject to online voting. To generate as much excitement as possible for the event, which was going to be a Citi Field affair prior to the All-Star Game, the Mets built one of their periodic blogger nights around a conference call with Nimmo.

That’s about what it sounds like. At an appointed hour, assorted media and quasi-media were shepherded into a room with a speaker phone on the table. A number was dialed. A 20-year-old’s voice was audible on the other end. Brandon Nimmo, I allowed myself to think, spoke with the humble cadences of a young (younger?) David Wright, though that might have been just my aspirations for him talking. My notes from that call indicate that he must have worked on his interviews and learned his clichés enough to make Crash Davis proud. Either that or he’s 20 and he sincerely believes in getting better every day while letting tomorrow take care of itself.

Brandon was extremely polite and eventually excused from any more interrogation; not long after he was authorized to hang up he would indeed be on his way to the Futures Game. In the meantime, the media departed. The quasi-media — your bloggertariat, that is — remained in that room with our friendly handler who dropped, in “by the way” fashion, that when we were done shooting the breeze in here we’d be meeting with Doc Gooden.

Oh.

Sure.

If you insist.

Doc was the centerpiece of a special ticket package that night, an all-inclusive admission that got you the game, some dinner, his book (signed) and a Q&A with him in the room usually reserved for Terry Collins explaining what went wrong with the bullpen in the eighth inning. I had partaken, as a civilian, in a similar deal for R.A. Dickey when he was promoting Wherever I Wind Up and found it a veritable bargain. One thing I noticed about Doc’s session, which we walked in on the tail end of, was Gooden lavished time and attention on every fan who asked for it, posing for pictures, chatting intimately, just being very available. It didn’t occur to me immediately that the reason he outstripped Dickey on that personable front was that R.A. — who was friendly enough but by comparison dished and dashed — had a team to get back to. Doc was there to be Doc. Legends-in-residence can set their own parameters.

When the last of the paying customers was done, we (maybe seven of us) were introduced on a first-name basis to Doc. As he went around our semi-circle, shaking our hands and greeting us personally, I had to seal all exits from my skin, for the next few minutes were about to become an out-of-body experience.

“Hey, you, sitting there — you’re shaking Dwight Gooden’s hand and he’s calling you Greg. Get a grip, literally and figuratively.”

Dwight Gooden has a very substantial right hand. It shakes quite well. It’s the same hand that won those 24 games, struck out those 268 batters and choked off opponents’ scoring at a rate of 1.53 earned runs per nine innings. I can still feel his right palm meeting my right palm the way I can still feel the only foul ball I ever legitimately caught — albeit on one bounce— landing in my left palm. That was in St. Petersburg, in 1982, less than three months before the Mets would draft a 17-year-old high school pitcher from across the bay in Tampa. Craig Swan was pitching for the Mets at Al Lang Stadium when I grabbed that ball with my bare glove hand. Almost two years later to the day, I’d be watching the 19-year-old Dwight Gooden pitching for the Mets at Al Lang Stadium.

Within a few weeks, in April 1984, Dwight Gooden would become Dr. K and it would never occur to me at his heights that I’d ever be shaking the hand attached to the arm attached to the best pitcher and my favorite player since Tom Seaver.

I listened to my fellow bloggers’ questions, I swear I did. I paid attention to Dwight Gooden’s answers, too. But mostly I had to mentally glue myself to my seat so I didn’t float away. Surreal doesn’t cut it as descriptors go. I was sitting across from Dwight Gooden, my second-favorite Met ever. If this was how I was handling an audience with Dr. K, just as well nobody ever let me achieve proximity to Tom Terrific. They might have had to have called security to have my hand removed from his.

I saw Doc up close once before, but this was different. He looked a little lost then. Here, he was in control of his narrative. Some combination of media coaching and rehab rules had kicked in, I imagined. It wasn’t like I hadn’t heard the basics of the story he was choosing to tell before this impromptu meeting. He’d been interviewed plenty since Doc was released and there were only so many answers he had for the questions that came up over and over.

What really got me here was the eye contact. Doc looked each of us in the eye. That had to be a rehab thing, right? “Face your demons,” I was guessing he was told as he worked to get better. I admired the way he locked in because I’ve never been good at it. I was in a school play once where the director told me to look the other actor with whom I was sharing the stage square in the eye and I just kept cracking up and ruining rehearsal.

All that staring into the window of the soul certainly gets your attention, though during the moments Doc was speaking to my blolleagues, my eyes wandered here and there. When you sit in that interview room at the proper angle, you can see out into the bowels of the stadium. They’re not very bowely yet, what with Citi Field not being that old, but this is field level without the field. It’s the ballpark’s basement. There’s a lot of action out in those bowels as everyone hurries hither and yon in pregame mode. In the span of no more than three minutes, I glimpsed both Jeff Wilpon and Cuppy promenading by.

Why, I asked myself, am I staring out into the bowels at them when I’ve got Doc right in front of me?

Finally, my turn to ask a question. I tried to think of something I hadn’t heard him respond to dozens of times. Because I was approaching the Torborg/Green era in my Happiest Recap research, I asked him about those days, my stated premise being you know, you were still “darn good” then (what a hard-nosed interviewer I am) even if the team was stuck in the bowels of the N.L. East.

Doc looked me directly in the eye and acknowledged there was a modicum of fun to be had in those days and definitely some good guys on that team — he name-checked Bret Saberhagen and Eddie Murray for their talent — but explained, “The chemistry wasn’t there.” If your second-favorite Met mentions chemistry, I decided it must a genuine component of winning even if it doesn’t show up in the box score. Gooden then pivoted from answering my question to a broader reminiscence of 1984 to 1989 when the Mets modeled an all-for-one and one-for-all ethos. “Guys would all go out to eat together,” especially those first few years when they were building toward a championship.

“When you win a World Series with a team,” Doc continued, never failing to look me straight in he eye, “those guys are always your teammates.”

Each of us having had a question and an answer, the semi-circle grew a little more informal, with more “what was it like when…” wonderings mixed in with a recovering addict’s affirmations that, in the spirit of Brandon Nimmo’s wisdom, it’s best to take everything one day at a time. For any Mets fan, it was a dream. We who were privileged to sit alongside the pitcher who authored 157 Met wins never mind three ghosted memoirs didn’t even mind that we were missing Matt Harvey’s first pitches to the Nationals. For me, it was a professional-type situation that defied standard note-taking. At the bottom of my last full page, this is what I scrawled in brackets, which I use to distinguish my thoughts from those of the speaker:

[“I’m looking into Doc Gooden’s eyes and I have to fight back tears.”]

I came close to welling up, but I pulled back on my ducts and remembered I was ostensibly a journalist, or at least a quasi-journalist here. I may have even thrown in another question for propriety’s sake, but was reveling in the moment too much to jot down a whole lot else. It wasn’t until after the PR folks gently nudged all of us apart that I felt something I can honestly say I hadn’t felt in decades.

I was overcome by the urge to call my mother and ask her to guess who I just spent like 15 minutes talking to…well, not me by myself, but with a few other people…Dwight Gooden, that’s who…yeah, Doc!…well, here’s how it happened…

Believe me, I didn’t have the desire to tell my mother much of anything that didn’t include an expletive while she was alive and there’s been little I’ve regretted not being able to exchange in the 23 years she’s been gone. But this was Dwight Gooden, and my mother loved Dwight Gooden. Maybe not exactly like I loved Dwight Gooden, but close enough during her baseball renaissance of 1984 to 1989, when whatever it was that got between us tended to thaw for a few hours if the Mets were playing.

Of course it did. We won the World Series with those guys.

by Greg Prince on 4 November 2013 10:51 am The best radio promotion I ever heard for the Mets aired the morning after they won the 1986 World Series. It consisted of every station in New York dwelling long and lovingly on the championship achieved in Queens the night before. There was no all-sports radio then, so the conversation was wholly organic, of the moment and impossible to affix a price tag upon. The formats didn’t matter. The hosts didn’t matter. All that mattered was the Mets were the biggest story in town, they had accomplished the biggest thing they could and, because they were on everybody’s mind, there was no way they weren’t going to be on everybody’s air.

So when the Mets in 2013 put out a press release to make official not just that their games will be heard on WOR, 710 on your AM dial, but that they and WOR parent Clear Channel will reinvent the wheel in terms of a “five-year landmark multimedia marketing partnership,” excuse me if I turn down the volume.

Clear Channel is a behemoth that owns a zillion radio stations, including more outlets in New York than the Mets have barely plausible first basemen. Games aren’t going to be broadcast on Z100 or Q104.3 or these other frequencies, but I guess when you hear some non-automated DJ suddenly launch into spontaneous praise of Jonathon Niese’s breaking ball from last evening out at rockin’ Citi Field, we’ll know it was bought and paid for. If this process somehow serves to ultimately ratchet up the excitement over the Met product, Met brand or the Met lifestyle and thus sells some additional tickets or merchandise or whatever allows our team to compete more effectively, well, go for it.

Mostly, though, I get the feeling the Mets had to issue a hype-laden press release, and it wasn’t enough to say, “Adjust your radio a few notches, see you in late February.”

Nowhere in the Mets’ missive touting their “multifaceted strategic alliance” with Clear Channel are Mets announcers specified, which kind of designates the lede for assignment. Besides knowing where the games can be found, all the Mets’ core constituency cares about vis-à-vis radio at the moment is who will be speaking into those WOR mics. Adam Rubin and others have been reporting Howie Rose is a lock to return but Josh Lewin’s status is unresolved.

The first half of that is great news. Howie is as much a part of Mets baseball as the skyline logo. After more than a quarter-century as a near-daily presence in our lives, he’s the aural equivalent of the Woolworth Building, at the very least.

The second half is unnecessarily murky and, from the perspective of the plain old Mets fan, stupidly mystifying. Josh has spent two years working his way up to Williamsburg Savings Bank status, logowise, and he’s done a damn fine job of it. I had my reservations when he was brought on board primarily because I identified him with Fox’s handling of baseball. I now realize holding a Fox microphone during a televised baseball game tends to lower an announcer’s IQ as if by corporate decree (with occasional Burkhardtian exceptions factored in, of course). Josh stopped being a Fox guy the second he sat down next to Howie. By the same turn, Howie’s creeping crankiness —a condition we all contracted via prolonged exposure to Wayne Hagin — commenced to receding when he partnered with Josh.

The team whose losing ways Howie and Josh have communicated may not have been much to listen for across 2012 and 2013, but the team Howie and Josh have formed has been worth tuning into, no matter Met fortunes on a given day or night. They know their stuff, which is no small statement after four years of Hagin sounding as if he just arrived from nowhere in particular. They maintain a terrific pace, which is also not a perfunctory compliment considering there’s an inside-the-park homer from 2007 that Tom McCarthy hasn’t yet finished describing. Best of all, they are splendid company to keep. When you get right down to it, that’s what a baseball listener wants and needs: voices with whom you want to spend the season, pitch by pitch, inning by inning, game by game.

I want Howie and Josh on that call. I need Howie and Josh on that call. I also want and need various morning menageries, whether Clear Channel’s or some other conglomerate’s, playing “We Are The Champions” on behalf of the Mets some future autumn a.m. (AM or FM) not because they are contractually obligated to but because it will be as accurate as the time and temperature they issue every four minutes.

There’s no better multimedia marketing promotion than winning. You don’t need the 105th caller to tell you that.

by Greg Prince on 2 November 2013 7:41 pm By 5 PM Sunday, darkness will have descended over the New York Metropolitan Area, a development fully attributable to the Baseball’s Over Act of 1917, implemented by Congress and signed by President Wilson when it was realized that once the World Series is done, then in all honesty, who cares how depressing it is outside?

To be fair, it’s depressing inside, too. On this last afternoon when the sun stayed strong until close to close to 6 PM, I flipped around the dial in search of a baseball game. The only one I could find was played a few weeks ago between Boston and Detroit. I’ll bet I watched it when it was happening. I’ll bet it seemed provisionally important. Maybe it was a classic. On this November Saturday, while the Red Sox enjoyed the confetti of their labor, I didn’t stick around long enough to discern which game it was. Its airing only served to taunt me.

The World Series 48 hours past, I watched my favorite basketball team pull out a one-point win over their league’s defending champion Friday night. I should’ve been thrilled. At most I was satisfied and moved on. None of these other sports played when it starts to get super dark super early can be taken seriously right now. It’s too soon for everything else even if it’s too late for baseball.

The Mets have bought out Johan Santana’s option. Either he received $5.5 million for disappearing from the roster or forfeited $19.5 million for not living up to every last hope we conjured around him nearly six years ago. The door has been described as slightly ajar in terms of a conditional invitation to Port St. Lucie, but I’d suggest, with malice toward none, shutting that door gently but firmly. Johan came up mighty shy of our expectations while simultaneously achieving things on our behalf that we couldn’t have imagined. Let’s just say we’re even.

Greg Burke is reportedly attracting interest from teams who aren’t the Mets. For a second, I thought maybe I’ve been too harsh in hoping his unreliable submarine picks up speed and is never spotted near Flushing Bay again. Then I decided if the Blue Jays or Rockies want to prove my queasiness at the sight of Greg Burke unfounded, they’re free to do so. Finally, I noticed I was thinking too intently about a middle reliever of little accomplishment who caused intermittent aggravation probably only because the sun was about to set and presumably never return. No offense intended to Burke, who’s probably a human being underneath all those earned runs. Then again, that was my excuse for Jason Bay across several frustrating seasons.

The sun won’t be what it used to be for a few months. But then it and what it brings with it will rise like a phoenix, which itself rose in Greek mythology like Marlon Byrd in 2013. For now, we fall back on unwelcome twilight, unsubstantiated free agent speculation and the occasionally engaging activity that fails to be baseball. Soon enough, however, spring ahead. Not really soon enough and not really soon, but eventually.

When the darkness is descending, you take what light you can get.

It’s a good weekend to reminded of the timelessness of loving baseball, and who better represents that clock-blocking quality than Vin Scully? Something I wrote on the subject for a non-baseball site here.

by Greg Prince on 31 October 2013 2:12 am Wow, the Red Sox won their first World Series at Fenway in 95 years!

Who’s gonna play first for us?

Unless Big Papi is holding a grudge against Kaiser Wilhelm, I suppose they can retire every last reference to 1918 up there.

None of the in-house candidates is remotely satisfactory.

Shame about Beltran not getting his ring.

Who’s gonna play short for us?

Shame about Victorino getting another, of course.

There’s not a single good, proven option on hand.

At least Molina looked miserable when it was over; so much for Cardinal inevitability.

Right field’s another zone of uncertainty, to put it mildly.

McCarver’s done on Fox — class act in his day, even if that day peaked around 1985.

I mean there’s nobody…NOBODY I’d put out there if I had to choose right now.

Even though I had no strong rooting interest, it was a pretty good postseason all around, I thought.

Geez, we have a lot of glaring holes.

It wasn’t the Mets, but I always enjoy getting caught up in it…as long as certain teams aren’t involved.

More treading water or are we gonna make some kind of splash?

I started watching baseball in 2013 on February 23 and I kept watching it until October 30.

And what defines “splash” anyway?

But now it’s time to move on, into winter and toward, should we all be so lucky, another spring.

I hope they don’t make any stupid trades…but that they don’t do nothing, either.

I have only one last thing to say as we enter the offseason.

Well, whatever.

Let’s Go Mets — yeah!

Let’s Go Mets — I guess.

by Greg Prince on 30 October 2013 9:58 am Year Books (as opposed to the Official Yearbooks available at concession stands or by sending $1.50 to Shea Stadium, Flushing, NY, 11368) are designed to easily entice historically minded readers. The formula makes sense on its surface. Something happened; something else happened; another thing was going on at the same time, too. You measure your thread, you tie your events/trends together, and — presto! — you have something potentially profound. That’s the idea, anyway, whether your focus is a year in baseball or a year examined within a wider sociological or cultural scope.

Someday I want to write a book titled or maybe just subtitled The Year Nothing Changed, though I don’t know what year it will refer to. My goal is to declare for the record that not “Everything Changed” in a given twelve-month span simply because a cynical editor or publisher thought pretending it did would goose non-fiction sales in the here and now. But to be fair, some things inevitably change if you give all things 365 days to strut their stuff. The world almost never succeeds at playing freeze tag.

Hmmm…maybe I should revise my concept to The Year Nothing Much Changed.

However much actually evolves or is of resounding consequence or just happens to be fun to relive when you limit a book’s field of vision to January 1 to December 31 (or, if it’s baseball, the end of the previous year’s World Series to the end of “your” year’s Fall Classic), then you need to make your raw material live up to its billing. I’ve read authors contort themselves in their attempts to convince their readers that this year in this here book encompassed everything you could possibly want from a year. If it snowed, it was a storm that blanketed everything in sight. If it rained, the ground never grew wetter. If it did neither, then the days were uncomfortably parched as [POLITICIAN] ran for office, [SONG] played on jukeboxes, [SLUGGER] swung for the fences and gas cost [COMPARATIVELY LITTLE] a gallon. The gymnastics to make it all work coherently can be positively frightening.

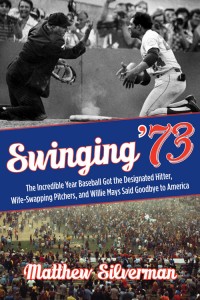

I’m pleased to report Matthew Silverman generally sticks his landings in Swinging ’73, which carries the ambitious subtitle Baseball’s Wildest Season and then makes sure to add another subtitle so we’re persuaded in advance that it was “The incredible year that baseball got the designated hitter, wife-swapping pitchers, world champion A’s, and Willie Mays said goodbye to America.”

Matt — my friend of several years and companion at many Mets games, so there’s your full disclosure — had me at “’73,” but I understand why a surfeit of information was loaded onto the cover. Not everybody lived through the 1973 major league season or the months immediately surrounding it. Not everybody was 10 years old as I was, forming impressions that have lasted a lifetime. Not everybody had a significant chunk of their worldview formed in 1973.

Wild times, indeed. I did. But if you didn’t, you have Matt, and he’s an able and affable tour guide to what you might have missed. It probably helped his cause that he’s just a wee bit younger than I am and freely confesses to not having paid attention to 1973 while it was in progress (whaddayawant from the guy — he was eight). Matt learned the basics in the years that followed but grew mighty curious to dig at what lay beneath them. That sense of personal discovery does the tone of Swinging ’73 good, allowing the author to implicitly share his delight at all that he’s found.

Was 1973 wild? I would have said so coming out of it on my eleventh birthday (12/31/73) and Matt’s book didn’t change my mind. The non-baseball portion attests to the vibe in the air — a vice president was resigning, a president wasn’t far behind him and then came Maude — while our grand old game definitely included some unprecedented twists. Like the first DH, Ron Blomberg. Like the innovative Fritz Peterson-Mike Kekich exchange of families. Like the ominous arrival onto the scene of George Steinbrenner. Like the tearing down of the House That Ruth Built and the imminent toppling of the home run record the Bambino set.

Geez, and that’s just the Yankee angle — and the Yankees fell out of their race in August (to at least one chum’s dismay). They’re not even the focal point of Swinging ’73 but Matt was sharp enough to make them one of his prisms. They always did know how to make news. The real baseball heroes of his story, however, are the eventual world champion Oakland A’s and, to our parochial interests, the National League Champion New York Mets.

Matt treats both entities with enthusiastic reverence, stressing the A’s credentials as all-timers and soliciting the thoughts of a cache of Met players for whom 1973 was their career pinnacle. The A’s deserve their praise, even if they earned it at the expense of our second world championship in five seasons. When you read Matt’s World Series account, you will come to truly admire this opponent from Olympus.

The Mets we hear from here form a somewhat different crew from those whose recollections you usually read in books like these. Matt gives us Matlack and Theodore and Capra and Staub and Hodges (Ron) plus a bit more Garrett than commonly comes up in a Metsian consideration of the Age of Miracles. It was a keen call on Matt’s part. Though only four years separated 1973 from 1969, a genuine interpretation gap exists between the two sensational surges. The Mets most strongly identified with 1969 who endured to make it to 1973 never seem all that excited to talk about the year when they almost won it all. When Tom Seaver announced Mets games, he gave me the impression that he basically went on hiatus after striking out 19 Padres in 1970. That’s how little he brought up 1973 (and how much he talked about 1969). Similarly, if you’re fortunate enough to spend a few minutes chatting with a Koosman or a Jones or a Kranepool, which I have, their calling card is the time they won the World Series, not the time they dazzled a city just to get there.

It’s an understandable impulse on their part, but that leaves roughly half a roster for whom 1973 was it in terms of World Series, not to mention playoffs. Those Mets have compelling stories and Swinging ’73 provides a wonderful forum for telling them. Reading the book and hearing Matt discuss it on multiple occasions was like being granted a seat at the 40th anniversary commemoration the Mets couldn’t be bothered to arrange for this team that worked undeniable wonders.

Wonders deserve our awe. So do the men who forge them and, yes, the years in which they are forged. The Mets apparently require reminding of that basic fact of fandom.

The Cardinals, whatever your opinion of ’em as they’ve played on this autumn, didn’t become the Cardinals by dint of an online survey or a sophisticated algorithm. They simply never stopped being the Cardinals. The winning is no small thing but they were the Cardinals even when they weren’t regularly going to playoffs and they always saw fit to underscore what being the Cardinals meant. There’s probably some connection between how the Cardinals present their heritage to their fans and how their fans see themselves as that heritage’s co-guardians. Nobody loves dressing in red enough to do so without a proprietary feeling for what the act epitomizes.

And nobody out Cardinal way stopped revering their tradition because some Octobers ended sooner than others.

Perhaps it’s because the Mets have come to process the majority of their October experiences as a matter of how far they didn’t go, but this organization’s decision to tacitly dismiss 1973 in particular as something markedly less sacred than 1969 or 1986 represents a lack of appreciation for and understanding of what actually happened four decades ago. Never mind that the Mets didn’t beat the A’s. The 1951 Giants didn’t win their World Series, but neither then nor now have those entrusted with tending that team’s legacy doctored Russ Hodges’s call so it blares, “THE GIANTS WIN THE PENNANT! BUT THEY FAILED TO SECURE THE OVERALL CHAMPIONSHIP! SO LET’S EVENTUALLY BARELY ACKNOWLEDGE THEIR INCREDIBLE ACHIEVEMENT!” The Giants, thousands of miles removed from the spot where Bobby Thomson’s ball landed, eternally toast the Miracle of Coogan’s Bluff.

The Mets determined handing out a sponsored deck of playing cards covered their obligations to remember the tidal wave of Belief that washed over Flushing on its 40th anniversary.

The Cards deal in heritage. The Mets deal playing cards. The final two games of the 1973 World Series were played over a three-day weekend that no longer exists. Veterans Day, long observed on November 11, had been transformed, Armistice date be damned, into a Monday holiday in 1971 and would stay as such through 1977. Because we had off from school on the fourth Monday in October, my parents took my sister and me to the Raleigh Hotel in the Catskills the preceding Friday. It was there that I watched as much of Games Six and Seven as I could. Technically I was heartlessly forbidden from tuning in — punishment I was receiving for not packing my fancy sports jacket as explicitly instructed —but the ban ultimately proved unenforceable (not that I haven’t found myself haunted by the threat). I was definitely watching when the ninth inning of the seventh game of our second World Series reached its armistice.

I don’t recall if it was because not repeating the feat of 1969 disturbed me to the point of sleeplessness, but I awoke the morning after uncharacteristically early. My older sister, with whom I was sharing a room, was up and at ’em, too, so with little left to do at the Raleigh until my parents were awake and ready to check out, Susan and I did what guests in the Catskills did when there were no meals being served. We went to sit in the lobby.

It was empty downstairs for quite a while, save for us and the desk clerk. Eventually, however, we were joined by a stack of that morning’s Daily News, the extremely thin edition shipped north to towns like South Fallsburg. I bought a copy and flipped through the sports pages, stopped cold by Bill Gallo’s cartoon. It showed Yogi Berra changing a few letters in a sign bearing a very familiar topical phrase while Basement Bertha looked on in sympathy.

“What’s ‘bereave’ mean?” I had to ask Susan, who had already taken the SATs.

“It has to do with being sad,” she explained.

Ah, YA GOTTA BEREAVE…yeah, I get it. Gallo’s humor seemed all too appropriate that mournfully quiet morning. But I didn’t bereave for long. Everything that preceded Games Six and Seven — the timely recovery from multiple injuries; the divisional deficit wiped away in a veritable blink; the legendary center fielder bidding his countrymen adieu; the muttery manager phrasing our odds awkwardly but accurately; the slight shortstop standing up for his smallish self; the indomitable pitchers who could barely be touched; the rallying cry heard ’round the Metropolitan Area; the astounding bounces that coalesced into an Amazin’ ball of virtual unstoppability — felt too life-affirming to allow a Mets fan to get bogged down in the grieving process over a pair of contests that didn’t go the Mets’ way. They were the only things that hadn’t since August 31.

The 1973 Mets won a division, won a pennant and, for how they attained those victories, won our faith forever after. Their loss of the World Series — legitimate George Stone flashbacks notwithstanding — veers to the incidental when considered in this context.

Or to put it in modern conference room parlance, 1973 built the Mets brand and imbued it with its key core equity. For those who don’t require a PowerPoint presentation, 1973 is why we Believe with a capital B. If Tug McGraw (whose spirit inhabits Matt’s book) had spouted a less relatable credo than “You Gotta Believe,” it wouldn’t resonate to this day every time a whisper of a hint of a chance pokes its head just barely above the surface of likelihood. Others might attempt to co-opt it, but it’s ours. The experience it stands for informs our soul like nothing else across the five-plus decades there have been Mets.

And it came from 1973. Due respect to Archibald Cox, Billie Jean King, Secretariat and Dark Side Of The Moon, that’s what definitely changed during that year, and for the likes of us, its ramifications were indeed wild. Tug and his teammates filed the copyright forms on behalf of all of us, whether we were around to Believe then or not. It was truly negligent of the Mets to not celebrate what it all still means to us in 2013. I’ve heard tell the folks in the counting house did a short-term cost/benefit analysis and decided a 1973 Day that went beyond the distribution of playing cards wasn’t a surefire draw, so they skipped it. I’d respond — in the kind of language they might grasp — that brand equity doesn’t activate itself.

I don’t know what will change in 2014, but I hope the Mets’ reluctance to fully embrace the Mets does.

by Greg Prince on 29 October 2013 11:52 am It’s a great day to be a Red Sox player or fan. It’s a slightly less great day to be a Cardinals player or fan, but, all things considered, it’s not so bad. Both teams have at least one more game scheduled and a world championship remains possible for either. For Mets fans who are paying attention, it’s as good a day as you want it to be in terms of a World Series transpiring without our players. You can root for or against one of these collectives depending on your tastes. Or you can stay neutral but keep an eye on what happens next. There is still a little “next” left to baseball in 2013, praise Selig.

If you choose to, you could be in that plurality of TV viewers who are enjoying a reasonably absorbing if not quite exhilarating Fall Classic. You’re also free to be in that vast majority of Americans who aren’t tuned in and are thus the subjects of the annual spate of articles examining why you don’t tune in. I’ve been reading these stories for more than twenty years. The theories don’t much change, but they do deepen, boiling down to the basic facts that: a) baseball doesn’t maintain the hold on the public imagination it once did; and b) things have changed too much in too many ways to expect that it would.

I suppose I still pine for a mythic world that hangs on every pitch and discusses each of them the next day, but I’ve probably never actually lived in that world (and, to be fair, I’m not quite hanging on every pitch). I came along when the World Series was played in daylight, the television dial was severely limited by modern standards and whatever thing you’re reading this on didn’t exist. It wasn’t necessarily a better world, but baseball was a bigger part of it.

Then again, no matter how overwhelming one assumes the World Series at the height of its powers — in the prime time era, at least — there were always dissenters. The afternoon prior to Game One of the 1986 edition, we had a visit from a couple of relatives on my mother’s side, a cultured, elderly couple who lived practically across the street from Lincoln Center. They were with it. They knew what was going on. Nevertheless when I mentioned my immediate priority was to watch the Mets in the World Series that Saturday night, I got a blank stare on the order of “What’s that?” Maybe that was just New York being New York, I figured. We have too many people interested in too many things to notice every little or big thing.

Subtract the participation of a beloved local team and multiply the blank stares exponentially, and you have the World Series as national non-phenomenon today. It used to bother me quite a bit. It bothers me much less this year. The Series still gets solid if not spectacular ratings, they’ll continue to televise it and it will continue to be covered and talked about. The conversation might not be universal, but it will range far and wide enough. Part of me thinks there’s something terribly wrong with a country that doesn’t drop everything to see how the baseball season concludes — and something incredibly off about baseball fans who seem proud of their lack of interest as October rolls on — but as with any given Mets game, if it’s being shown, I’m watching, and I’m pretty sure I’m not the only one. That will have to do.

What somehow surprises me is that major leaguers not on the Red Sox or Cardinals don’t necessarily watch. I’ve ascertained this dirty little secret quite incidentally, now and again noticing a tweet from a 2013 Met who is off to some concert or on safari or perhaps fixing that loose step he keeps promising the wife he’ll get to. There’s nothing wrong with any of it. It’s none of my business, actually, except I keep learning what they’re up to because I followed them on Twitter while they were playing and they insist on telling me.

I get that it’s their hard-earned vacation time and I admit I don’t know how often they’re checking their devices for scores and highlights as they pursue their various non-baseball adventures. Maybe they’re DVRing every game. They probably have that package that records ten shows at once and thus don’t have to conk one another over the head with a bat as they decide what shows to tape. They’re professional ballplayers. They can afford it.

They’re professional ballplayers is more the point, though. I would think that as a member of this highly exclusive fraternity they would have a proprietary interest in seeing how the World Series turns out. It’s their craft being performed for the highest stakes at (though not every play is flawless) the highest level. Just from an aficionado standpoint, you’d think they’d be into it. And from an aspirational standpoint, too. Isn’t the World Series where these guys want to be? Couldn’t have they flown to South America next week or caught up with the Zak Brown Band at a later stop? Shouldn’t have their schedules been clear through the beginning of November anyway, just in case?

I think I’m only about a quarter-serious in being disappointed to realize players don’t automatically watch other players play the World Series, but it does strike me as a little sad. My sister long ago asked me how it would work if a Met wanted to go to a baseball game that didn’t involve the Mets. After explaining that the Mets are usually playing at the same time as other teams, I guessed it wouldn’t be too hard for, say, Tom Seaver to get a ticket if the Mets were off and a game was being played in some other city. I grew up and learned that players get tickets — probably really good ones — to pretty much whatever they want just because they’re players. It’s known as a perk.

Then I got older and had it confirmed baseball players don’t much care if other baseball players are playing for a championship that long ago evaded their own grasp. You learn something new every year.

|

|