The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 30 October 2013 9:58 am Year Books (as opposed to the Official Yearbooks available at concession stands or by sending $1.50 to Shea Stadium, Flushing, NY, 11368) are designed to easily entice historically minded readers. The formula makes sense on its surface. Something happened; something else happened; another thing was going on at the same time, too. You measure your thread, you tie your events/trends together, and — presto! — you have something potentially profound. That’s the idea, anyway, whether your focus is a year in baseball or a year examined within a wider sociological or cultural scope.

Someday I want to write a book titled or maybe just subtitled The Year Nothing Changed, though I don’t know what year it will refer to. My goal is to declare for the record that not “Everything Changed” in a given twelve-month span simply because a cynical editor or publisher thought pretending it did would goose non-fiction sales in the here and now. But to be fair, some things inevitably change if you give all things 365 days to strut their stuff. The world almost never succeeds at playing freeze tag.

Hmmm…maybe I should revise my concept to The Year Nothing Much Changed.

However much actually evolves or is of resounding consequence or just happens to be fun to relive when you limit a book’s field of vision to January 1 to December 31 (or, if it’s baseball, the end of the previous year’s World Series to the end of “your” year’s Fall Classic), then you need to make your raw material live up to its billing. I’ve read authors contort themselves in their attempts to convince their readers that this year in this here book encompassed everything you could possibly want from a year. If it snowed, it was a storm that blanketed everything in sight. If it rained, the ground never grew wetter. If it did neither, then the days were uncomfortably parched as [POLITICIAN] ran for office, [SONG] played on jukeboxes, [SLUGGER] swung for the fences and gas cost [COMPARATIVELY LITTLE] a gallon. The gymnastics to make it all work coherently can be positively frightening.

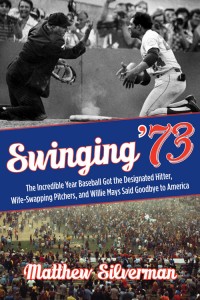

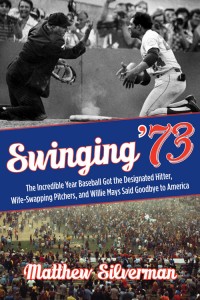

I’m pleased to report Matthew Silverman generally sticks his landings in Swinging ’73, which carries the ambitious subtitle Baseball’s Wildest Season and then makes sure to add another subtitle so we’re persuaded in advance that it was “The incredible year that baseball got the designated hitter, wife-swapping pitchers, world champion A’s, and Willie Mays said goodbye to America.”

Matt — my friend of several years and companion at many Mets games, so there’s your full disclosure — had me at “’73,” but I understand why a surfeit of information was loaded onto the cover. Not everybody lived through the 1973 major league season or the months immediately surrounding it. Not everybody was 10 years old as I was, forming impressions that have lasted a lifetime. Not everybody had a significant chunk of their worldview formed in 1973.

Wild times, indeed. I did. But if you didn’t, you have Matt, and he’s an able and affable tour guide to what you might have missed. It probably helped his cause that he’s just a wee bit younger than I am and freely confesses to not having paid attention to 1973 while it was in progress (whaddayawant from the guy — he was eight). Matt learned the basics in the years that followed but grew mighty curious to dig at what lay beneath them. That sense of personal discovery does the tone of Swinging ’73 good, allowing the author to implicitly share his delight at all that he’s found.

Was 1973 wild? I would have said so coming out of it on my eleventh birthday (12/31/73) and Matt’s book didn’t change my mind. The non-baseball portion attests to the vibe in the air — a vice president was resigning, a president wasn’t far behind him and then came Maude — while our grand old game definitely included some unprecedented twists. Like the first DH, Ron Blomberg. Like the innovative Fritz Peterson-Mike Kekich exchange of families. Like the ominous arrival onto the scene of George Steinbrenner. Like the tearing down of the House That Ruth Built and the imminent toppling of the home run record the Bambino set.

Geez, and that’s just the Yankee angle — and the Yankees fell out of their race in August (to at least one chum’s dismay). They’re not even the focal point of Swinging ’73 but Matt was sharp enough to make them one of his prisms. They always did know how to make news. The real baseball heroes of his story, however, are the eventual world champion Oakland A’s and, to our parochial interests, the National League Champion New York Mets.

Matt treats both entities with enthusiastic reverence, stressing the A’s credentials as all-timers and soliciting the thoughts of a cache of Met players for whom 1973 was their career pinnacle. The A’s deserve their praise, even if they earned it at the expense of our second world championship in five seasons. When you read Matt’s World Series account, you will come to truly admire this opponent from Olympus.

The Mets we hear from here form a somewhat different crew from those whose recollections you usually read in books like these. Matt gives us Matlack and Theodore and Capra and Staub and Hodges (Ron) plus a bit more Garrett than commonly comes up in a Metsian consideration of the Age of Miracles. It was a keen call on Matt’s part. Though only four years separated 1973 from 1969, a genuine interpretation gap exists between the two sensational surges. The Mets most strongly identified with 1969 who endured to make it to 1973 never seem all that excited to talk about the year when they almost won it all. When Tom Seaver announced Mets games, he gave me the impression that he basically went on hiatus after striking out 19 Padres in 1970. That’s how little he brought up 1973 (and how much he talked about 1969). Similarly, if you’re fortunate enough to spend a few minutes chatting with a Koosman or a Jones or a Kranepool, which I have, their calling card is the time they won the World Series, not the time they dazzled a city just to get there.

It’s an understandable impulse on their part, but that leaves roughly half a roster for whom 1973 was it in terms of World Series, not to mention playoffs. Those Mets have compelling stories and Swinging ’73 provides a wonderful forum for telling them. Reading the book and hearing Matt discuss it on multiple occasions was like being granted a seat at the 40th anniversary commemoration the Mets couldn’t be bothered to arrange for this team that worked undeniable wonders.

Wonders deserve our awe. So do the men who forge them and, yes, the years in which they are forged. The Mets apparently require reminding of that basic fact of fandom.

The Cardinals, whatever your opinion of ’em as they’ve played on this autumn, didn’t become the Cardinals by dint of an online survey or a sophisticated algorithm. They simply never stopped being the Cardinals. The winning is no small thing but they were the Cardinals even when they weren’t regularly going to playoffs and they always saw fit to underscore what being the Cardinals meant. There’s probably some connection between how the Cardinals present their heritage to their fans and how their fans see themselves as that heritage’s co-guardians. Nobody loves dressing in red enough to do so without a proprietary feeling for what the act epitomizes.

And nobody out Cardinal way stopped revering their tradition because some Octobers ended sooner than others.

Perhaps it’s because the Mets have come to process the majority of their October experiences as a matter of how far they didn’t go, but this organization’s decision to tacitly dismiss 1973 in particular as something markedly less sacred than 1969 or 1986 represents a lack of appreciation for and understanding of what actually happened four decades ago. Never mind that the Mets didn’t beat the A’s. The 1951 Giants didn’t win their World Series, but neither then nor now have those entrusted with tending that team’s legacy doctored Russ Hodges’s call so it blares, “THE GIANTS WIN THE PENNANT! BUT THEY FAILED TO SECURE THE OVERALL CHAMPIONSHIP! SO LET’S EVENTUALLY BARELY ACKNOWLEDGE THEIR INCREDIBLE ACHIEVEMENT!” The Giants, thousands of miles removed from the spot where Bobby Thomson’s ball landed, eternally toast the Miracle of Coogan’s Bluff.

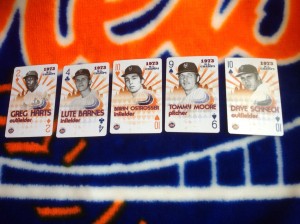

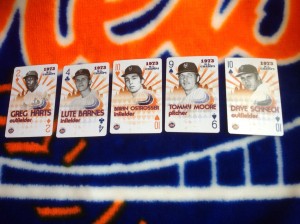

The Mets determined handing out a sponsored deck of playing cards covered their obligations to remember the tidal wave of Belief that washed over Flushing on its 40th anniversary.

The Cards deal in heritage. The Mets deal playing cards. The final two games of the 1973 World Series were played over a three-day weekend that no longer exists. Veterans Day, long observed on November 11, had been transformed, Armistice date be damned, into a Monday holiday in 1971 and would stay as such through 1977. Because we had off from school on the fourth Monday in October, my parents took my sister and me to the Raleigh Hotel in the Catskills the preceding Friday. It was there that I watched as much of Games Six and Seven as I could. Technically I was heartlessly forbidden from tuning in — punishment I was receiving for not packing my fancy sports jacket as explicitly instructed —but the ban ultimately proved unenforceable (not that I haven’t found myself haunted by the threat). I was definitely watching when the ninth inning of the seventh game of our second World Series reached its armistice.

I don’t recall if it was because not repeating the feat of 1969 disturbed me to the point of sleeplessness, but I awoke the morning after uncharacteristically early. My older sister, with whom I was sharing a room, was up and at ’em, too, so with little left to do at the Raleigh until my parents were awake and ready to check out, Susan and I did what guests in the Catskills did when there were no meals being served. We went to sit in the lobby.

It was empty downstairs for quite a while, save for us and the desk clerk. Eventually, however, we were joined by a stack of that morning’s Daily News, the extremely thin edition shipped north to towns like South Fallsburg. I bought a copy and flipped through the sports pages, stopped cold by Bill Gallo’s cartoon. It showed Yogi Berra changing a few letters in a sign bearing a very familiar topical phrase while Basement Bertha looked on in sympathy.

“What’s ‘bereave’ mean?” I had to ask Susan, who had already taken the SATs.

“It has to do with being sad,” she explained.

Ah, YA GOTTA BEREAVE…yeah, I get it. Gallo’s humor seemed all too appropriate that mournfully quiet morning. But I didn’t bereave for long. Everything that preceded Games Six and Seven — the timely recovery from multiple injuries; the divisional deficit wiped away in a veritable blink; the legendary center fielder bidding his countrymen adieu; the muttery manager phrasing our odds awkwardly but accurately; the slight shortstop standing up for his smallish self; the indomitable pitchers who could barely be touched; the rallying cry heard ’round the Metropolitan Area; the astounding bounces that coalesced into an Amazin’ ball of virtual unstoppability — felt too life-affirming to allow a Mets fan to get bogged down in the grieving process over a pair of contests that didn’t go the Mets’ way. They were the only things that hadn’t since August 31.

The 1973 Mets won a division, won a pennant and, for how they attained those victories, won our faith forever after. Their loss of the World Series — legitimate George Stone flashbacks notwithstanding — veers to the incidental when considered in this context.

Or to put it in modern conference room parlance, 1973 built the Mets brand and imbued it with its key core equity. For those who don’t require a PowerPoint presentation, 1973 is why we Believe with a capital B. If Tug McGraw (whose spirit inhabits Matt’s book) had spouted a less relatable credo than “You Gotta Believe,” it wouldn’t resonate to this day every time a whisper of a hint of a chance pokes its head just barely above the surface of likelihood. Others might attempt to co-opt it, but it’s ours. The experience it stands for informs our soul like nothing else across the five-plus decades there have been Mets.

And it came from 1973. Due respect to Archibald Cox, Billie Jean King, Secretariat and Dark Side Of The Moon, that’s what definitely changed during that year, and for the likes of us, its ramifications were indeed wild. Tug and his teammates filed the copyright forms on behalf of all of us, whether we were around to Believe then or not. It was truly negligent of the Mets to not celebrate what it all still means to us in 2013. I’ve heard tell the folks in the counting house did a short-term cost/benefit analysis and decided a 1973 Day that went beyond the distribution of playing cards wasn’t a surefire draw, so they skipped it. I’d respond — in the kind of language they might grasp — that brand equity doesn’t activate itself.

I don’t know what will change in 2014, but I hope the Mets’ reluctance to fully embrace the Mets does.

by Greg Prince on 29 October 2013 11:52 am It’s a great day to be a Red Sox player or fan. It’s a slightly less great day to be a Cardinals player or fan, but, all things considered, it’s not so bad. Both teams have at least one more game scheduled and a world championship remains possible for either. For Mets fans who are paying attention, it’s as good a day as you want it to be in terms of a World Series transpiring without our players. You can root for or against one of these collectives depending on your tastes. Or you can stay neutral but keep an eye on what happens next. There is still a little “next” left to baseball in 2013, praise Selig.

If you choose to, you could be in that plurality of TV viewers who are enjoying a reasonably absorbing if not quite exhilarating Fall Classic. You’re also free to be in that vast majority of Americans who aren’t tuned in and are thus the subjects of the annual spate of articles examining why you don’t tune in. I’ve been reading these stories for more than twenty years. The theories don’t much change, but they do deepen, boiling down to the basic facts that: a) baseball doesn’t maintain the hold on the public imagination it once did; and b) things have changed too much in too many ways to expect that it would.

I suppose I still pine for a mythic world that hangs on every pitch and discusses each of them the next day, but I’ve probably never actually lived in that world (and, to be fair, I’m not quite hanging on every pitch). I came along when the World Series was played in daylight, the television dial was severely limited by modern standards and whatever thing you’re reading this on didn’t exist. It wasn’t necessarily a better world, but baseball was a bigger part of it.

Then again, no matter how overwhelming one assumes the World Series at the height of its powers — in the prime time era, at least — there were always dissenters. The afternoon prior to Game One of the 1986 edition, we had a visit from a couple of relatives on my mother’s side, a cultured, elderly couple who lived practically across the street from Lincoln Center. They were with it. They knew what was going on. Nevertheless when I mentioned my immediate priority was to watch the Mets in the World Series that Saturday night, I got a blank stare on the order of “What’s that?” Maybe that was just New York being New York, I figured. We have too many people interested in too many things to notice every little or big thing.

Subtract the participation of a beloved local team and multiply the blank stares exponentially, and you have the World Series as national non-phenomenon today. It used to bother me quite a bit. It bothers me much less this year. The Series still gets solid if not spectacular ratings, they’ll continue to televise it and it will continue to be covered and talked about. The conversation might not be universal, but it will range far and wide enough. Part of me thinks there’s something terribly wrong with a country that doesn’t drop everything to see how the baseball season concludes — and something incredibly off about baseball fans who seem proud of their lack of interest as October rolls on — but as with any given Mets game, if it’s being shown, I’m watching, and I’m pretty sure I’m not the only one. That will have to do.

What somehow surprises me is that major leaguers not on the Red Sox or Cardinals don’t necessarily watch. I’ve ascertained this dirty little secret quite incidentally, now and again noticing a tweet from a 2013 Met who is off to some concert or on safari or perhaps fixing that loose step he keeps promising the wife he’ll get to. There’s nothing wrong with any of it. It’s none of my business, actually, except I keep learning what they’re up to because I followed them on Twitter while they were playing and they insist on telling me.

I get that it’s their hard-earned vacation time and I admit I don’t know how often they’re checking their devices for scores and highlights as they pursue their various non-baseball adventures. Maybe they’re DVRing every game. They probably have that package that records ten shows at once and thus don’t have to conk one another over the head with a bat as they decide what shows to tape. They’re professional ballplayers. They can afford it.

They’re professional ballplayers is more the point, though. I would think that as a member of this highly exclusive fraternity they would have a proprietary interest in seeing how the World Series turns out. It’s their craft being performed for the highest stakes at (though not every play is flawless) the highest level. Just from an aficionado standpoint, you’d think they’d be into it. And from an aspirational standpoint, too. Isn’t the World Series where these guys want to be? Couldn’t have they flown to South America next week or caught up with the Zak Brown Band at a later stop? Shouldn’t have their schedules been clear through the beginning of November anyway, just in case?

I think I’m only about a quarter-serious in being disappointed to realize players don’t automatically watch other players play the World Series, but it does strike me as a little sad. My sister long ago asked me how it would work if a Met wanted to go to a baseball game that didn’t involve the Mets. After explaining that the Mets are usually playing at the same time as other teams, I guessed it wouldn’t be too hard for, say, Tom Seaver to get a ticket if the Mets were off and a game was being played in some other city. I grew up and learned that players get tickets — probably really good ones — to pretty much whatever they want just because they’re players. It’s known as a perk.

Then I got older and had it confirmed baseball players don’t much care if other baseball players are playing for a championship that long ago evaded their own grasp. You learn something new every year.

by Greg Prince on 27 October 2013 11:11 am From a purely parochial view — and what is our collective perspective on this World Series if not Metsian in these regionally defined baseball times? — I score the final play of Game Three 2-3-2: Stearns to Hernandez to Gibbons.

You won’t find it in your box score but like Jim Joyce in the interview room, I’ll do my best to explain my thinking.

Let’s see…second and third, one out, tie score, bottom of the ninth, Boston’s playing the infield in for Jon Jay to prevent the winning run from scoring. Not too much riding on the next pitch from Koji Uehara, eh? Uehara delivers and Jay grounds a ball Dustin Pedroia smothers and fires home to Jarrod Saltalamacchia. Running if not exactly storming down the third base line is Yadier Molina, my walking nightmare since October 19, 2006. He’s carrying the winning run, but mostly lugging it. Because Pedroia was so diligent in securing and releasing Jay’s throw, it’s fairly obvious to Molina that he’s going to be out at the plate.

Yadier’s only hope is to crash into Saltalamacchia. We’ve been told over the seven years since we became intimately acquainted with the catcher who never gets enough historical scorn for snatching what was supposed to be our first pennant since 2000 that Yadier Molina does everything right. The right thing to do here, if you want to score the run that will put your team up 2-1 in the World Series, is to bowl over the other catcher. John Stearns would’ve done it, right? John Stearns was fearless on both sides of the ball. John Stearns determined John Stearns had right of way whether he was wearing a chest protector and shin guards or hurling himself into someone who was.

Yadier Molina clearly wasn’t channeling his fellow multi-time All-Star Stearns as he approached the plate Saturday night in St. Louis. He plays in the modern era when full-impact collisions at the plate are frowned upon. It’s bad enough that a catcher receives them. Does a catcher who is considered his club’s most valuable member really need to be issuing them? You can reference discretion being the better part of valor or chalk it up to professional courtesy. No way in hell is Yadier Molina, championship-round game on the line or not, going to barrel into Jarrod Saltalamacchia. He’s not going to do a blessed thing to disturb a single consonant on the back of his opposite number’s jersey. Instead, he slides in a perfunctory manner, several feet short of home, making no attempt to sprinkle Salty’s equipment all over Busch Stadium. He’s out, he knows it and he gets himself tagged. Two down.

In that instant, I can hear Keith Hernandez, who played in the age when men were men, catchers absorbed runners, runners took on catchers and John Stearns would do anything to win. I can imagine Keith taking time out from his reverence for all things Cardinal to chastise Molina specifically and all players today generally for their indulgence of “country club baseball,” for their “la-de-da” attitude in a game-winning situation, for opponents offering one another a “spot of tea” instead of a ticket square into the backstop. And I can hear myself, from the comfort of my couch, egging Keith on.

But that instant ends pretty quickly because there’s another play developing, like in a superstorm. The hurricane has blown out but look — it’s a nor’easter! Allen Craig, who initially hesitated on the grounder Pedroia so expertly captured, was now making his move on third. Had Saltalamacchia been knocked on his rear by Molina, no doubt Craig goes in without a throw. Jarrod would’ve been in no position to do anything about it.

Ah, but Molina had left Salty standing, his faculties fully intact, and since he had complete control of the ball after tagging Yadier, he was capable of throwing in the footsteps of another Mets catcher.

This is how I’d like to think the seeds were planted. It’s Saturday afternoon. Tim McCarver is down on the field, making the rounds, chatting up the players on both sides. As old catchers are wont to do, he seeks out Saltalamacchia and shares with him some of the benefit of the experience he has accumulated through decades as a catcher and decades watching other catchers from his perch in the booth.

Hey Salty, Timmy says, I’ve seen some things in this game.

Like what, the genuinely curious Bosock asks.

Why, there was this time when I announcing for the Mets that the DARNEDEST double play unfolded.

Oh, please tell me more, Mr. McCarver. Like most active players, I enjoy soaking up the wisdom dispensed by my elders.

You can call me Tim, the broadcaster insists, and goes on to fill his new protégé in on the details of a long-ago night in San Diego.

Well, Salty, it was like this: the bottom of the eleventh, last night of a long West Coast swing, Mets clinging to a one-run lead. Davey Johnson had to use Doug Sisk, who wasn’t a very good reliever. He had already given up a double to Garry Templeton, who could fly. With one out, Tim Flannery singles to center. Templeton takes off and you’re pretty sure he’s gonna score, we’re gonna be tied and we’re never gettin’ out of Jack Murphy Stadium. But Lenny Dykstra charges and fires and Templeton is OUT AT HOME! And that would keep the inning going, Mets still up by a run with two out, except Sisk notices Flannery kept runnin’ and was headin’ to third, so he tells the catcher, John Gibbons, who’s lyin’ on the ground after Tempy bowled him over, to look — you’ve got another play! So Gibby — who’s only in there ’cause Gary Carter is injured and Ed Hearn needs a blow — gets up and fires to Howard Johnson at third and…OUT AT THIRD! The Mets win it, six to five! What a double play! Just your routine double play!

As you can imagine, Saltalamacchia has stars in eyes after his chat with the Fox announcer. After Tim wishes him well in tonight’s game, the younger man thinks, I’d sure like a chance to be in one of those kinds of plays. I’ll bet Mr. McCarver would get a real kick out of it.

That’s how I imagine it anyway.

I can’t swear what Saltalamacchia was thinking when he decided that with two out in the bottom of the ninth inning of this tied World Series game he’d throw to third in hopes of nabbing Craig. If he doesn’t, Pete Kozma, 0-for-Fall Classic, is up as the potential third out and if Kozma doesn’t get on, the Red Sox have Victorino, Pedroia and Ortiz up to start the tenth. Granted, that’s a lot to think about in an instant. If Molina had laid him out or even nudged him a bit, Saltalamacchia wouldn’t have had the chance to think. He could have simply, in an expression old-time Red Sox fans would recognize, held the ball.

But he had the time and the wherewithal to throw to third. He was inspired to be another John Gibbons.

It didn’t work out for Jarrod Saltalamacchia the way it worked out 27 years and two months earlier for Gibby. Boston’s catcher threw past third baseman Will Middlebrooks, which guaranteed that Allen Craig could trot home with the winning run…which he wasn’t doing because…what the hell was going on? Craig had stumbled or something, and was that Daniel Nava hustling over, picking up the ball, throwing it to Salty, and was that Craig, just getting over a foot injury that had kept him out of the National League playoffs, getting tagged out at home to end the ninth?

Yes and no. What Craig stumbled over was Middlebrooks. Middlebrooks had fallen down and couldn’t get up. He was suddenly an inanimate object (though his legs flailed). He didn’t mean to get in the way, much as that piece of furniture in the middle of your living room that you mindlessly clank into meant you no harm. But it’s there and it gets in your way regardless of intent. Middlebrooks was guilty of having transformed into a coffee table. By stumbling over him as he attempted to advance, Craig became, in the umpires’ judgment and a dispassionate reading of the written rule book (we were all about to become constitutional experts on something called 7.06), entitled to home plate. Home plate meant a run. A run meant the game. The game meant the Cardinals led the World Series.

As Stephen Colbert might have judged it, that was the Craziest F#?King Thing I’ve Ever Heard. Or seen. Or expected to read in Baseball Digest when I was a kid about some enduring World Series mystery from 1925. A World Series game ended with a couple of relatively furtive signals from Jim Joyce at third and Dana DeMuth at home. Ah, but a rule’s a rule, regardless of optics. Red Sox rooters were left to argue intent, as if litigating an ill-fated Florida recount, but baseball doesn’t leave that many chads hanging. Middlebrooks obstructed Craig as Craig tried to score. That was that. Helluva way to end a game of this nature, and you’re free to interpret that sentiment as your partisanship permits.

Game Three, however, was over.

My conclusion? Yadier Molina, by permitting Jarrod Saltalamacchia to remain in position to make the poorly conceived throw to third that ultimately allowed Allen Craig to be ruled safe at home despite never actually touching the plate, is an evil genius. But we’ve known that since a very dark night in 2006.

by Greg Prince on 25 October 2013 7:06 pm In honor of what transpired 27 years ago tonight, here is the slightest taste of Game 252 among the 500 Most Amazin’ the Mets ever won, from the forthcoming The Happiest Recap: Second Base (1974-1986). This excerpt focuses on the task that threatened to devour the Mets as they headed to the bottom of the tenth inning.

Shea Stadium was built on the site of an ash heap, and as Saturday, October 25, morphed into Sunday, October 26, the locale’s original purpose seemed apropos. This Mets season…the greatest Mets season ever…was three outs from being what you bring to the dump. The 108-54 record wouldn’t matter. The three resurrection wins against the Astros wouldn’t matter. The National League pennant secured in sixteen grueling innings within the Astrodome din wouldn’t matter. Tying the series at Fenway Park wouldn’t matter. Withstanding Roger Clemens wouldn’t matter. Tying Game Six at 2-2 in the fifth and 3-3 in the eighth wouldn’t matter.

Not winning the World Series was all that was about to matter. Losing the World Series, too, for that’s what the Mets were on the verge of doing. The 1986 Mets were built to do everything but that. It was as if a mechanism had malfunctioned, as if Michael Sergio’s rip cord didn’t activate properly. Sergio’s message was GO Mets.

Going home — emptyhanded — seemed the more plausible response.

The Red Sox, despite stranding 14 runners in 10 innings, were two runs up and three outs away from a state of nirvana. Henderson’s home run loomed as a decisive blow for the ages, but the one-two double-single punch Boggs and Barrett threw at Aguilera was what set up the Mets’ mission as almost prohibitively daunting. Boston had every advantage. Schiraldi could afford to give up a run. McNamara could afford to give up a little defense, even if it meant going against his norm. In the three previous Red Sox wins, he inserted Dave Stapleton at first to tighten the infield perimeter. But here in Game Six, with his wounded solider of a starting first baseman having limped this far, the manager hesitated to make that move.

Thus, the same man who left Calvin Schiraldi in for a third inning of work decided Bill Buckner should take the field in the bottom of the tenth.

The rest of the story…coming soon.

And happy anniversary, greatest night that ever was!

by Greg Prince on 24 October 2013 5:03 pm Carlos Beltran made a great catch look routine in the first game of the World Series. Then he had to leave because he hurt himself in the process. How much he can be expected to play in the remaining three to six games is a matter best left to trainers, doctors and conjecture until he takes some swings and sees how he feels. (UPDATE: He’s playing in Game Two.)

That’s about as Beltran a set of facts as one could conceive. The man makes things look far easier than they are; absorbs the blows nobody quickly comprehends; reaches a new pinnacle in his career; finds himself in dangerous day-to-day territory regarding his availability to continue scaling this peak experience; and, as a throwback of sorts, his team loses without him.

The 2013 Cardinals are no 2009 Mets at this stage of their postseason, though they at nearly full-strength appeared about as discombobulated as the Beltranless bunch we grimly cheered on when it was without Carlos, the other Carlos, Jose and David for a dizzying spell but chock full of Wilson Valdez and Jeremy Reed. The Red Sox were already well on their way to grounding the Redbirds Wednesday night when Beltran took three away from Boston and one for the team. But losing Carlos made the seven-run defeat almost incidental.

Granted, I say that as someone whose only Cardinal rooting interest in this is what goes on Carlos Beltran’s spare ring finger. I’m sure actual St. Louis fans are pretty upset about an 8-1 Boston thrashing and 0-1 Series deficit. I’ll let you know when I’m worried on their behalf. In the meantime, I take selective solace in the idea that if Beltran’s rib contusion confines him to exactly one moment in the World Series spotlight, it came on defense.

Carlos Beltran is a defensive genius. That’s a title that’s normally reserved for your Bill Belichick types as they’re working their way up the coordinating ladder, yet in 45 years of watching Mets baseball, I’ve never seen an outfielder so flat-out knowledgeable about fly balls, their journeys in progress and their ultimate destinations. Before his knees began to go, you didn’t necessarily notice the head because the legs moved so well. But the smarts were coaching the speed all along. There was no more spectacular example than the night at Minute Maid Park when the whole of Carlos knew exactly what it was doing as he homed in simultaneously on a long fly and a steep hill. The result was pure poetry. It dazzled a little more than most of Beltran’s glovework, a state of affairs attributable to his ability to disguise the extraordinary as ordinary.

You watch the David Ortiz grand slam he reduced to a sacrifice fly and you see someone who is not fazed by how far the ball is traveling because he knows what he’s doing out there. He tracks a ball as if he’s equipped with state-of-the-art GPS. The reach over the fence should be a bigger deal — he robbed Big Papi of three RBIs! But it’s just what this guy does. He didn’t have to dazzle because he had the route mapped out in advance and also the patience to pull over to side of the road of his mind and check the mental map before he drove too far off in the wrong direction. If a leap or a dive was required, Carlos would have leapt or dove. It wasn’t necessary. A slight adjustment was what he needed to make. Like the best coaches in football, he made it in order to get the ball back.

Did he have to sustain a poke to the ribs while committing grand theft baseball? Harold Reynolds demonstrated on MLB Network what made the catch painful. The right fielder managed to impale himself between sections of the Fenway fence. Beltran’s radar isn’t perfectly calibrated to avoid personal calamity. Give him a chance to come back, though, and he’ll probably figure a way around that, too.

by Greg Prince on 23 October 2013 7:34 pm You can read a thorough appraisal of the late Bill Mazer’s life here. You can read the man himself reflect on a career that he wouldn’t have argued over if you called it Amazin’ here. And if you grew up a sports fan in the New York Metropolitan Area between the 1960s and the 1990s, you can tune in your own memories of a broadcasting icon of the highest order, a gentleman who has left us at age 92.

Right here, though, you get my Bill Mazer story. It isn’t long. That, according to Bill, was its charm.

It’s a weeknight late in the 1972 season. The Mets have either won or lost. I’m going to guess they won. Let’s say they won. I’ve been listening to the game on WHN 1050 and now I’m staying tuned for Mets Wrap-Up with Bill Mazer. Bill asks listeners to call in with their Met concerns and questions. I have one that’s been bugging me for months.

Whatever became of Buzz Capra?

Buzz was a righthander on whom I fixated during the 1972 season, same as I fixated on Ray Sadecki in 1970. What the Mets needed, I was convinced, was more Buzz Capra. I’m guessing the critical mass of seeing the name Buzz Capra on some combination of a rookie card (shared with Jon Matlack and Leroy Stanton, the latter already thrown in with Nolan Ryan to obtain the services of Jim Fregosi, oy), a Baseball Digest preseason roster and a quarter-page of the Official Yearbook had me buzzing for Buzz. His name was Buzz, for crissake. What more reason did I need to fixate?

Buzz made the team. Yogi Berra gave him six starts and had him relieve eight times. Mostly you didn’t see a lot of Buzz Capra. His final appearance came July 7. I had never gotten the memo as to why he no longer pitched among us.

So I did what a person in these parts did when the library was closed and before there was an Internet. I called Bill Mazer. He answered. It went more or less like this (more than less):

“Hello, you’re on the air.”

“Hello. I was wondering why the Mets farmed out Buzz Capra.”

Note use of proper lingo on my part. I didn’t read Baseball Digest every month for my health.

“He needed more seasoning.”

“Oh. OK. Thank you.”

“Is that it?

“Yes. Thank you.”

After I hung up, Bill told the rest of his audience, “I wish all my calls could be as easy as that young man’s.”

This happened 41 years ago. I’m going out on a limb and guessing Bill probably forgot about it by the next commercial break. I’m still dining out on it.

Here’s to those who have earned the right to behave like big shots but conduct themselves as human beings. And here’s to those who know their stuff. Bill really did. With a little more seasoning under his belt, Buzz contributed to the 1973 pennant drive, saving the game in Pittsburgh that kicked off the winning streak that vaulted the Mets into first place. A year later, fully seasoned, Buzz Capra led the National League in earned run average. True, he did so for the Braves, but that wasn’t Bill Mazer’s doing.

Please enjoy a little of Bill’s Mets work from one of their greatest days.

by Jason Fry on 23 October 2013 8:47 am Well, Yankees fans hate the Red Sox … if the Cardinals win again at least Carlos Beltran gets a ring … Hmm.

You know what? Never mind that for now. It’s time to welcome the latest budding immortals and dudes you’ve already forgotten who make up the THB Class of 2013.

Background: I have a trio of binders, long ago dubbed The Holy Books (THB) by Greg, that contain a baseball card for every Met on the all-time roster. They’re in order of matriculation: Tom Seaver is Class of ’67, Mike Piazza is Class of ’98, Matt Harvey is Class of ’12, etc. There are extra pages for the rosters of the two World Series winners, including managers, and one for the 1961 Expansion Draft. That page begins with Hobie Landrith and ends with the infamous Lee Walls, the only THB resident who neither played for nor managed the Mets.

If a player gets a Topps card as a Met, I use it unless it’s truly horrible — Topps was here a decade before there were Mets, so they get to be the card of record. No Mets card by Topps? Then I look for a minor-league card, a non-Topps Mets card, a Topps non-Mets card, or anything else. Topps had a baseball-card monopoly until 1981, and minor-league cards only really began in the mid-1970s, so cup-of-coffee guys from before ’75 or so are tough. Companies such as TCMA and Renata Galasso made odd sets with players from the 1960s — the likes of Jim Bethke, Bob Moorhead and Dave Eilers are immortalized through their efforts. And a card dealer named Larry Fritsch put out sets of “One Year Winners” spotlighting blink-and-you-missed-them guys such as Ted Schreiber and Joe Moock.

Insert joke about floor and high ceilings here. Then there are the legendary Lost Nine — guys who never got a regulation-sized, acceptable card from anybody. Brian Ostrosser got a 1975 minor-league card that looks like a bad Xerox. Leon Brown has a terrible 1975 minor-league card and an oversized Omaha Royals card put out as a promotional set by the police department. Tommy Moore got a 1990 Senior League card as a 42-year-old with the Bradenton Explorers. Then we have Al Schmelz, Francisco Estrada, Lute Barnes, Bob Rauch, Greg Harts and Rich Puig. They have no cards whatsoever — the oddball 1991 Nobody Beats the Wiz cards are too undersized to work. The Lost Nine are represented in THB by DIY cards I Photoshopped and had printed on cardstock, because I am insane.

During the season I scrutinize new card sets in hopes of finding a) better cards of established Mets; b) cards to stockpile for prospects who might make the Show; and most importantly c) a card for each new big-league Met.

(Apologies to everybody who’s read that a ton of times. Want to read it some more? Previous annals are here, here, here, here, here, here, here and here.)

Last winter Greg Prince’s years of patient questions and gentle campaigning culminated in reworking The Holy Books so the players were in order of matriculation instead of alphabetical within the year of their debuts. So shall it be here:

John Buck: Installed behind the plate with Travis d’Arnaud at Triple-A, Buck smashed nine home runs in April, causing us to say mean things about Josh Thole and declare that d’Arnaud could stay in Las Vegas for the year or possibly forever. Buck then hit six home runs the rest of the season while never walking — basically what John Buck had done throughout his career with the exception of April 2013. (And, OK, 2010, but that was in the American League and in Canada, which is two reasons it shouldn’t count.) 2013 Topps 2 card in airbrushed Mets togs.

Collin Cowgill: Cat-eyed outfielder who hit a grand slam on Opening Day, leading to an excess of “More Cowgill” jokes, then played indifferently for the rest of April, leading to an appropriate number of “Less Cowgill” jokes. Returned from the minors in June, which I have no memory of, and was then sent to the Angels. 2013 Topps Update “Chasing History” insert card that’s autographed. This piece of cardboard cost basically nothing but still annoys me, because 1) Cowgill last swung a bat in anger for the Mets around Flag Day; 2) it’s a horizontal, and horizontals hurt America; and 3) it’s the SECOND “Chasing History” insert card Cowgill got in 2013. Which member of Clan Cowgill works for Topps?

Marlon Byrd: Byrd’s 2012 could redefine miserable. He acknowledged that he still worked with BALCO honcho Victor Conte, played horribly with the Cubs and Red Sox, got released, then was suspended after testing positive for the estrogen blocker Tamoxifen. Byrd said he took the drug to treat a recurrence of gynecomastia, for which he’d had surgery a few years back. Gynecomastia is the growth of breast tissue in males, a condition that sometimes arises from steroid use and sometimes doesn’t; either way, it’s not the kind of thing a man wants to stand at his locker getting quizzed about. Byrd became a Met after the team lost out on its half-hearted pursuit of Michael Bourn, a Sandy Alderson pickup greeted with the kind of cheers normally reserved for a jury duty summons. So of course Bourn was merely OK in Cleveland and Byrd had a terrific campaign in New York, emerging as a clubhouse leader and fan favorite before getting flipped to the playoff-bound Pirates in exchange for useful reliever Vic Black and second-base prospect Dilson Herrera. Not bad, Mr. Alderson, not bad at all. 2013 Topps Update card in which he’s sliding home past Miguel Montero. It’s a horizontal, because Topps hates me.

Brandon Lyon: Well-traveled veteran reliever was pretty good for the Astros and Jays in 2012, then awful for the Mets in half a season, leading to his release. Middle relievers, sheesh. Unless you’re the Rays, every one of them is a crapshoot. 2013 Topps card on which Lyon’s a Blue Jay.

Scott Atchison: A 37-year-old reliever who looked 57, Atchison was nicknamed “Dad” by Mets fans, which was funny and better than being nicknamed “Warm Body,” though the latter would have been a perfect description of him. Some really old Upper Deck card that bills him as a Mariners “Star Rookie,” which is the kind of flight of fancy excusable when offered by elderly aunts and writers of copy for the back of baseball cards.

Scott Rice: Gigantic reliever who looked a bit like a thug seen in the background of some frame of “The Princess Bride.” Rice was a nice story in 2013, making the Mets after six organizations, 14 seasons and this itinerary of professional homes: Sarasota, Fla.; Bluefield, West Va.; Aberdeen, Md.; Delmarva, Frederick, Md.; Bowie, Md.; Ottawa; Surprise, Ariz.; Clinton, Iowa; Frisco, Texas; Central Islip, N.Y.; Newark, N.J.; San Antonio; Tulsa; Colorado Springs; York, Pa.; Chattanooga; Albuquerque. You think Rice didn’t consider hanging it up somewhere in there? Proved useful enough, with the rather predictable outcome that Terry Collins rode him into the ground. Had surgery for a hernia in early September; one hopes he’ll be back. 2012 Albuquerque Isotopes card.

Greg Burke: Consistently lousy submariner bounced back and forth between New York and Las Vegas, arousing less enthusiasm each time he reappeared. Unlikely to return as a Met; likely to show up as the last guy on somebody else’s staff and make you go “oh that’s right” during the sixth inning of some ho-hum game in June 2014 or 2015. Las Vegas 51s card, fittingly.

LaTroy Hawkins: Proof that not all of Sandy Alderson’s bullpen signings are disasters. The 40-year-old Hawkins’ arrival marked his ninth organization in as many years, and at first he was notable chiefly for goading the Mets into making a “Harlem Shake” video. But he was solid all year, even taking over closer duties from Bobby Parnell without a hitch. Bringing him back for another campaign might be pushing it, but he’ll be fondly remembered. No 2013 Topps card; last year Topps made cards for Manny Acosta, Miguel Batista, Tim Byrdak, Josh Edgin, Jeremy Hefner and Ramon Ramirez. That makes sense.

Aaron Laffey: Discarded after four horrible April appearances in which he allowed 21 baserunners in 10 innings. Not very funny, Aaron. 2010 Topps card.

Anthony Recker: A lesson in patience — on April 30 Recker had perhaps the worst defensive inning I’ve ever seen from a catcher, capping a month in which he had exactly one hit. It sounds like damning with faint praise to say he got better, because how exactly could he have got worse? But he got better, hitting .317 in August and September and looking much more capable behind the plate. Plus he pitched an inning against the Nats, during which Angel Hernandez squeezed him on pitches and John Buck remarked that he had experience catching position players: “I played for the Royals, man … not my first blowout.” Good times! 2011 Bowman card.

Juan Lagares: Converted infielder surprised everyone by emerging as the best defensive center fielder since Carlos Beltran, making even difficult plays look routine and gunning down runners aplenty. The jury’s still out on his bat, but Lagares showed signs of improving his approach at the plate as he gained big-league experience. One of the year’s most pleasant surprises. 2013 Topps Update card.

Shaun Marcum: Started late, then pitched in what looked like abominable luck but was actually karma. After riding off into the post-surgical sunset with a 1-10 record, Marcum criticized Gary, Keith and Ron on Twitter and was savaged by fans and scribes alike. AND STAY OUT. Got a 2013 Topps Update card despite last being seen on July 6.

Andrew Brown: Prospect-turned-suspect showed flashes of power in part-time outfield role, but struggled for playing time. 51s card.

Rick Ankiel: Ankiel’s rise and fall and reinvention with the Cardinals is a well-known and inspiring story, but that was a long time ago. Picking up Ankiel in mid-May after the Astros no longer wanted him was one of the more mystifying decisions of the Alderson regime, transferring playing time from young guys who needed it to an old guy who all too obviously no longer merited it. Ankiel’s final big-league AB was a strikeout that ended a 20-inning loss against the Marlins in June, a sad end to a final chapter that never should have been written in the first place. 2010 Topps Opening Day card, of all things.

David Aardsma: Bald, buff reliever pitched well enough until overuse took its toll. Bumped Don Aase from his place as the first Met in alphabetical team history, though no one can bump Don Aase from his place as the first Met in our hearts. 2012 Topps card as a Mariner.

Carlos Torres: Arrived unexpectedly in mid-June, the beneficiary of a promote-him-or-lose-him contract clause, and surprised everybody by pitching quite serviceably as a swingman. Will probably be back, and deservedly so. 51s card.

Zack Wheeler: Followed the Matt Harvey route to the big leagues, refining his craft in Triple-A, getting bored and arriving in New York after a predictable delay related to service time. When he arrived he was every bit as much of a treat as Harvey had been, showing off a dazzling repertoire and seeming to get better with every start. If he continues along the Harvey arc, look out National League. (Though let’s skip the tragic lack of run support and Tommy John surgery.) 2013 Topps Update card.

Eric Young Jr.: Not as good a player as people think, but brought the Mets much-needed speed, defense, and energy. And hey, getting him for Collin McHugh was a pretty nice bit of front-office thievery. 2013 Topps Update card.

Gonzalez Germen: Looked destined to become the 10th Met Ghost, sitting on the bench for a long stretch in early July, but got into a game after all and then pitched well enough for the rest of the year. Should be in the mix in 2014. He’s a middle reliever, so who the heck knows. 51s card.

Wilmer Flores: Bad-bodied kid with a quick bat and no obvious position. Seems most valuable as a trade chip to be sent somewhere he can DH in peace. The Mets of the early 1990s would have stuck him at second base. Yipes! 2013 Topps Heritage Minor League card on which he’s a 51.

Travis d’Arnaud: The centerpiece of the R.A. Dickey trade, d’Arnaud’s brief audition demonstrated a knack for drawing walks but not for getting hits, which is probably just a product of a small sample size. Already winning plaudits for his ability to frame pitches, the current frontier in baseball science. Here’s hoping he can stay on the field, relax, and let the hits come. No Topps Update card; instead he’s represented by a 2013 Topps Pro Debut card on which he’s a Buffalo Bison, a team he’s never played for. Nice job, Topps.

Matt den Dekker: Grapefruit League injury derailed a possible trip north for this sure-gloved center fielder, which opened the door for Collin Cowgill and eventually Juan Lagares. Once he finally arrived, looked superb in both center and right and showed surprising power. Promising, but then we once said similar things about Kirk Nieuwenhuis. 2012 Pro Debut card.

Daisuke Matsuzaka: Another lesson in patience. Matsuzaka looked awful in his first three starts after the Mets grabbed him out of the Indians’ Triple-A ranks, but his next four were terrific. It wouldn’t be the craziest idea for the Mets to make him 2014’s Shaun Marcum, hopefully minus being bad and annoying. 2013 Topps card as a Red Sock.

Vic Black: Came over from Pirates in the Marlon Byrd trade and looked decent enough, with a high-90s fastball complemented by a good slider. He’s a reliever, so we’ll see. 2012 Pro Debut card.

Sean Henn: Who? 2011 Las Vegas card.

Aaron Harang: I admit to prejudice against ham-and-egger starters whose sole reason for getting a roster spot seems to be their status as Proven Veterans™ — why on earth would you want to come to the park to watch, say, Livan Hernandez get older? But the September Mets were truly screwed, with injuries and innings limits eliminating all real options within the organization. So enter Harang, to my infinite displeasure. How’d he do? Not badly at all — see Daisuke Matsuzaka above, and shut up Jace. 2012 Topps card.

Juan Centeno: Pint-sized catcher sat on the bench for nine games, then collected two hits in his debut and later gunned down Reds speed merchant Billy Hamilton. Not bad! 51s card.

Wilfredo Tovar: Ruben Tejada’s broken leg forced the Mets to call Tovar, who was sitting at home to Venezuela after an up-and-down season with Binghamton. Pressed into service, Tovar promptly collected a pair of hits in beating the Phillies, which was enough to endear him to any Mets fan. Good glove, iffy bat, zero speed — it’s like the factory ran off an extra Ruben Tejada while no one was looking.

And that’s a wrap! See you next year!

by Greg Prince on 20 October 2013 1:17 pm Hello, I have time-traveled to your October 2013 from the Octobers of 1946, 1967 and 2004, and I am curious to discover if your World Series will be materially different from the ones I have encountered on my journey. May I please see your matchup?

Hmmm…don’t you people ever change?

It only feels like I just woke up from historical, distant and recent memory to discover yet another World Series pitting the Red Sox versus the Cardinals. Rematches are fun every generation or two. You get them squeezed into the same decade and they get a little old if they don’t include your team.

We are also faced with the third World Series in six to encompass Shane Victorino, and it’s not like he drafted in on his teammates’ coattails for this one. Victorino, in case you looked away at the sight of this athlete, philanthropist and Met-buzzing gadfly, socked the decisive grand slam that ultimately gave Boston the pennant Saturday night. You can’t argue with the stepping up and getting it done, but you can withhold your applause if you so choose.

Beyond Victorino — whom I might cheer if his and my interests directly intersected but they don’t — the Red Sox seem like a fine bunch of fellows, their story of rocketing from worst to first is inspiring (even if it reflects really badly on Bobby Valentine’s 2012 influence) and if they want to grow beards that stretch from Fenway to Philadelphia, that’s their business. I spent one adolescent summer in a smoldering second-team romance with them, and though 1978 didn’t work out so hot on that Dented front, I’m now and then moved to maintain the slightest of embers for my old A.L. flame. Such lingering if mostly faded affection for some things Red Sock appeared permanently snuffed out by the New England attitudes of October 1986, but it turned out I was in a fairly forgiving mood afterward.

Nevertheless, the Red Sox have Shane Victorino, so that’s pretty sickening. The Cardinals, meanwhile, have Yadier Molina, so they sort of cancel each other out in my perceived enmity…except Molina’s a bigger part of the Cardinals’ overall success than Victorino is of the Red Sox’…but Carlos Beltran is on the Cardinals, and though I’m operating at narrative capacity verging on overload where so-called “Señor Octubre” is concerned, the thought of a team with Beltran trumping a team with Victorino is always appealing.

Unless the team with Beltran is the Cardinals, then the arrangement is laced lousy with loopholes.

It’s one of those whaddayagonnado? World Series, albeit at a lower level of default disgust than that which could be otherwise generated. A World Series featuring a stew of teams, players and fan bases you prefer to not see repeatedly rewarded could be far worse, as any Mets fan sentient in 2009 and 1999 could attest.

Though I’ll get over it in a matter of hours, I’m genuinely sorry the Tigers couldn’t break through (though a DET-STL World Series also wouldn’t be anything baseball doesn’t already know from in storybooks, film clips and “didn’t we just have one of those?” recollections). Since the dissolution of what was left of my once-beloved 2002 Angels, I’ve been without a favorite American League team. Detroit would be a nominal choice to fill that role, though I’ll admit I’ve never given them a ton of thought when they’re not right in front of me. Yet my familiarity with them from the past three postseasons and our recurring Interleague visits since 2010 combined to draw me to their cause on a temporary basis this time around. I found myself in the 2013 ALCS not rooting against the Red Sox at all but definitely pulling for the Tigers.

That didn’t work out, either, as they emitted undeniable signals in every one of their losses — even the dramatic ones — that they would eventually conjure a way to secure defeat. Perhaps if Miguel Cabrera, who wasn’t moving all that great when he was raking at Citi Field in August, didn’t appear in dire need of a wheelchair or at least a chaise lounge, his team would be playing Game Seven tonight or already preparing for Game One Wednesday night. But I’m pretty sure Bobby Ojeda would roll his eyes at that thought and remind Chris Carlin that at this time of year, everybody is hurting, so suck it up and strap ’em on.

Putting aside Cabrera’s wounded walking, the tantalizingly talented Tigers just lacked the crispness necessary to put away an opponent that was no less than their equal. If there was a rundown to be Throneberryed, a ground ball to be Jefferiescized, a double play to be Castilloed into or a tenuous lead to be utterly Heilmanated, the Tigers would do it. As solid and sound as they could be for most of a season or a game, and for as many perennial Cy Young and MVP candidates as they seem to feature, they came to remind me of long-ago backup infielder Don Buddin as he was portrayed by Brendan Boyd and Fred Harris in The Great American Baseball Card Flipping, Trading and Bubble Gum Book:

Don Buddin was a creative goat. He was the sort of guy who would perform admirably, even flawlessly, for seven or eight innings of a ballgame, or until such time as you really needed him. Then he would promptly fold like Dick Contino’s accordion. Choke. Explode. Disintegrate. Like a cheap watch or a ’54 Chevy. He would give up the ghost and depart. […] If there was a way to make the worst out of a situation, Don Buddin could be counted on to find it.

Don Buddin was a Red Sock most of his career, but finished up as a Tiger in 1962. Figures.

While Detroit inevitably Buddined, the cameras captured Jim Leyland calculating how much he was aging and how few chances he might have left to return to a World Series. When I see his face, my instant impulse is to think what a shame that Good Ol’ Jim has never won the big one; then I make a quick correction to my thinking and remember, no, the 1997 Marlins, that was Leyland. He won a ring and accepted accolades and got to enjoy the whole bit for a good five minutes before Wayne Huizenga systematically dismantled a world champion. Maybe that’s why it seems like he’s never gone all the way. There were those three consecutive autumns in the early ’90s when his Pirates couldn’t make it over the hump and now there’ve been these three in the early ’10s when his Tigers fell similarly heartbreakingly short. Jim Leyland wears the face of proud disappointment like no manager I’ve ever seen.

It’s hard to recall that he once interrupted his stoicism with a smile at the end of an October, but he really did. Granted Jim Leyland winning his only World Series as manager of the Florida Marlins was like Chuck Berry earning his only No. 1 single with “My Ding-a-Ling,” but when you hit the top of the chart after years of trying, they all look line drives in the next day’s box score.

Mike Matheny or John Farrell will soon tie Jim Leyland in the World Series rings accumulated while managing department. Shane Victorino could very well have twice as many parades thrown in his and his teammates’ honor as Tom Seaver, or Yadier Molina could wind up with three times as many as either of them. One among Nations identifying themselves as Red Sox or Redbird is guaranteed a third full-out celebration in the span of less than ten years. Truly, you can drive yourself to distraction if you peer at these things with excessive granularity.

by Greg Prince on 19 October 2013 2:32 am When I think of the Cardinals winning yet another pennant, I think of the episode of The Simpsons in which Grandpa Abe tells Bart the story of the Flying Hellfish from World War II, which leads to the two of them tracking down valuable stolen paintings that could make them very rich. Ultimately, however, they must be returned to the descendant of the original owner, a young German baron who accepts the U.S. State Department’s apologies with casual Eurotrash disdain, barking at an American official to be careful “mit der art things” as they’re placed in the trunk of his Mercedes. As Baron von Wortzenberger drives off to “Dancecentrum in Stuttgart to see Kraftwerk,” Grandpa considers the fortune he has lost and rationalizes, “I guess he deserves it more than I do.”

I’m not necessarily as gracious as Abe Simpson, and since I don’t believe any of the St. Louis Cardinals read Faith and Fear in Flushing, I’ll dispense with perfunctory congratulations in their direction. They don’t need my congratulations anyway. They seem to do very well without my support. The Cardinals started the National League Championship Series as inevitable and they ended it, inevitably, as National League champions. I’m sure capturing another flag was difficult, but they sure make it look simple.

Carlos Beltran enters his first World Series as a result of his team’s six-game victory over the Dodgers, and that’s nice, I suppose. I thought I was rooting for him above all Cardinals to make it, but the longer he wears a uniform that isn’t the Mets’, the less I see him as any cause personal to me. Great player whose time in New York I’ll always appreciate, but very much a Cardinal these days. That’s by no means an insult, even if it’s not a term of endearment. I was planning to add that at least we finally have a Met from October 2006 going to the Fall Classic, but that bit of business was actually taken care of by fan favorite Guillermo Mota when he was a 2010 Giant.

Just as true Mets fans will recognize October 18 as the date of the final wholly worthwhile game of the 1973 World Series, we are burdened to notice that in the hours since the Cardinals clinched their third pennant in eight seasons, it has turned to the seventh anniversary of October 19, 2006, a.k.a. the last time the Mets played a playoff game (they didn’t win). It was pointed out to me by my friend Garry Spector that of the 28 players who saw action in Notorious Game Seven, few are still active in the big leagues…though it turns out three of them — the currently champagne-soaked trio of Beltran, Adam Wainwright and Yadier Molina — will be active Wednesday night, too. The others include two Mariners (Oliver Perez and Endy Chavez), one Angel (Albert Pujols), one Blue Jay (Jose Reyes) and one Met (David Wright).

Time flies, hitting a person over the head in the process.

I framed this NLCS as a team I don’t like taking on a team I can’t stand. The Can’t Stands won, but I came to not completely dislike the Dodgers along the way. Maybe it was the exposure to Vin Scully or overexposure to the Right Way To Do Things. However I came across it, I probably found as much simpatico for L.A. as I have in a big-time situation since their predecessors were snatching the 1981 World Series from the jaws of intolerable. The 2013 postseason — akin to the wave of misreported teen suicides in Heathers — seems to have given Hanley Ramirez depth, Adrian Gonzalez a soul and Carl Crawford a brain. I don’t know if Don Mattingly is much of a manager but I actually felt kind of bad at how he can never, ever get to a World Series in any uniform. I’d mention the Dodgers’ debilitating injuries here, but the Cardinals soldier on like crazy through debilitating injuries (anybody seen Carpenter, Craig, Garcia or Motte lately?), so maybe I won’t. Plus Mattingly got within two games of a World Series, while Terry Collins is home getting eight hours of sleep every night and three square meals every day; consider my sympathy limited and contextual.

Next up for the Cardinals: Some team we’ve seen them play in a World Series in the last ten years and yet another team that will be in its third World Series in a decade. Familiarity breeds impatience here on the sidelines, but this time Beltran will be involved, so that’s different at least.

by Greg Prince on 18 October 2013 6:57 pm Forty years ago tonight, the National League champion Mets hosted Oakland, tied with the American League champion A’s at two games apiece in the 1973 World Series…and they were about to post one of the 500 most Amazin’ wins of their first 50 years.

From The Happiest Recap (First Base: 1962-1973)…

***

The Shea Stadium scoreboard was hailed as a modern marvel before anybody ever saw it. Billed as “the Stadiarama,” it promised to mesmerize every fan who could see it from the 96 percent of seats planted within the foul poles of the new ballpark. One of its highlights would be the large field given over to electrically transmitted messages, enabled by “approximately 28,000 lamps, arranged in clusters capable of forming letters and numerals […] [T]hrough one of the message display groupings, it is even possible to show ‘Sing Along’ messages when it’s time to break into song!”

That’s how Met management put it in the Shea preview pages of the team’s 1963 yearbook sold at the Polo Grounds. Ten years later, the reality of the Shea Stadium scoreboard wasn’t quite as breathtaking, and not just because the Mets never seemed to put enough runs on it. As Shea’s first decade wore on, the scoreboard made mistakes. Those letters and numerals didn’t necessarily flash as planned. Lamps that burned out weren’t immediately replaced. From the stands, it looked like a segment of the “approximately 80 miles of wiring” was prone to shorting out.

Yet for as gaffe-prone as the Shea scoreboard could be as it matured, there was no telling that it got a basic fact of the 1973 World Series wrong the Thursday night Game Five ended. The Mets had just won, 2-0, with Don Hahn and John Milner knocking in runs against Vida Blue, and Jerry Koosman and Tug McGraw combining on a three-hitter. The Mets were up 3-2 in the best-of-seven set. Given that information, the minds behind the scoreboard controls decided to post a most hopeful message as if it were fact.

“MIRACLE NO. 2,” the Stadiarama gleefully informed 54,817 frostbitten fans, awaited “3000 MILES AWAY”.

Wrong on two counts, it turned out.

***

You’ll find out the rest of the story, and why it wasn’t necessarily a sad one, when you read The Happiest Recap (First Base: 1962-1973).

Print edition available here.

Kindle version available here.

Personally inscribed copy available here.

No Mets fan should be without The Happiest Recap. It’s got the whole Amazin’ story of the Mets’ most unbelievable stretch drive ever…and everything that brought them there.

|

|