The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 17 October 2013 3:04 pm I’m as happy as a Puig in slop that the Tigers and Dodgers won on Wednesday. It means the daily baseball express rolls on.

While the Mets and 18 other clubs scattered to golf courses far and wide as of September 29, the good teams kept on playing. The A.L. Wild Card tie between the Rays and Rangers was broken on September 30. The next day the government shut down. The day after that the Pirates shut down the Reds. The day after that the Rays did the same to the Indians. The day after that the playoffs began in earnest, and thanks to staggered scheduling and just enough competitiveness to ensure each matchup is brought either to the brink or to the brink of the brink, we’ve had a game every single day. We have the Tigers and Red Sox tonight and are guaranteed a continuation of the NLCS in St. Louis tomorrow night and some more ALCS the next night.

Plus the government started operating again today, so it’s practically win-win.

I shouldn’t use language too strong for what I’d do to have the Mets be part of this or some near-future October lest a clever prosecutor cross-examine me and ask me to confirm, under oath, “Isn’t it true you said you’d ‘kill’ to have the Mets make the playoffs?” But who among us wouldn’t figuratively go ape, even if it meant a judge ordering us to consume multiple bananas on the witness stand, if it were the Mets taking on the Dodgers or the Cardinals or any opponent handy? As much as I enjoy that somebody’s playing big-time baseball against somebody else (and neither somebody is the Yankees), goodness I miss being a part of it all. It’s really beginning to hit home how rarely we’ve stormed or wheedled our way in.

Twenty teams have been around since 1962 or earlier. The Mets have participated in seven of the 51 postseasons that have been conducted in what we’ll call the Metropolitan Era. You know how many of their cohort — not counting the clubs that came along later — have been in more?

Almost all of them, for crissake.

Tell ya what, let’s lop off 1962 to 1968 when it would have been unreasonable to expect the Mets, Astros, Senators or Angels to finish first among ten teams (despite the Halos’ surprising run at an A.L. title in ’62), and start with 1969, since that signaled the beginning of divisional play and provided definitive proof that an expansion team could eventually grow up to be a full-fledged champion of something. In the 44 fully executed seasons that concluded two-and-a-half weeks ago, excluding strike-shattered 1994, the Mets have still made the playoffs only seven times.

Making the playoffs fewer times among their 19 established brethren:

The White Sox (5)

The Cubs (6)

The Rangers formerly known as Senators (6)

And that’s it. Then it’s the Mets and Tigers, with 7 apiece, and it moves up the frequency ladder to the long-dormant Indians (8 times, all since 1995), the expansioneer Angels and Astros (9 each) and a few franchises that have experienced oases of dominance amid endless dry spells (Pirates, Giants, Orioles and Twins, 10 apiece). From there you get all those teams that the unaligned fan probably finds himself instinctively rooting against sooner or later because nothing exceeds like success:

The Reds (11)

The Phillies (12)

The Dodgers (13)

The Red Sox and Cardinals (14)

The A’s (17)

The Braves (19)

You don’t want to be explicitly reminded (22)

For the record, of the teams that came into existence from 1969 forward, it goes, from top to bottom, Royals (7), Blue Jays, Diamondbacks and Padres (5), Brewers, Rays and Mariners (4), Rockies (3), Exponentials/Natspos and Marlins (twice apiece). The Mets at least haven’t been outflanked by their juniors — and maintain a little something to hold over the head of the Windy City should that become a priority. (It might prove useful should an argument over pizza styles require a digression.)

All of this is to say I’m used to seeking succor in October baseball that isn’t synonymous with Mets baseball. It’s not just better than nothing. It’s better than most things. It’s October 17 and the summer game will be televised nightly through October 20, perhaps October 21 and then, following a short break, hit the airwaves again October 23. I’m well-versed in immersing myself in seemingly random matchups of Dodgers and Cardinals, Red Sox and Tigers, Whoever and Whoever. I can take a side, I can choose a foe, I can change my mind or I can just sit back and admire.

But I sure wish I’d had the opportunity to have been overwhelmed by the presence of the Mets in October more than seven times in my 44 postseasons to date; more than three times in the past 24 postseasons; more than once in the past 13 postseasons; and more than not at all in the past 7 postseasons.

I wish I had a problem on my hands like Yasiel Puig. I’d love to have a guy that talented on my team breaking unwritten rules left and right in games that are tallied toward championship consideration. Or, I suppose, I’d love for my team to be carping at a guy that talented from the other dugout right about now provided they were getting him out as often as the Cardinals have.

I’ve listened to and read a lot of opinions on how Puig plays the game during this NLCS. What I’ve noticed is that he is literally playing the game while most others in his sport are pursuing wildlife and/or fish in presumably sportsmanlike fashion. If “excitable” or “emotional” or whatever code words are applied to Puig’s non-grimness is how the kid rolls, and his manager doesn’t find himself trying to demote him while being called a sucker of some kind, then he doesn’t bother me.

Besides, my unwritten rule — though I’m apparently writing it here — is if a Met does something at odds with convention, it’s probably OK, whereas if it’s being done against the Mets, it’s a horrible affront to all that is sacred and thus requires retribution or a tantrum of some kind.

The Mets, as mentioned, aren’t playing. Do what ya want, Yasiel.

I also wish I had a problem on my hands like inconvenient starting times for my Mets playoff games. For years the gripe of choice has been playing too many games too late. It will probably be regriped during the World Series. There was also, going back nearly twenty years, what I considered a very legitimate concern regarding concurrent scheduling. In the mid-’90s, baseball’s best minds concocted a plan in which all four division series would run simultaneously but no more than one would be beamed into a given market — likewise the first five games of both league championship series. That strategy was known as The Baseball Network, a splendid 1995 answer to the afterstrike question, “How do we keep as many of our fans in the dark as possible?” Fortunately, TBN lasted only that one postseason.

About a decade later, it was decided the bulk of the LCSes should be played at the exact same time, with one featured on Fox and one shifted to a (then totally obscure) cable outlet known as FX depending on where you lived. If you were in New York, which was understandably caught up in the 2004 ALCS and its excellent outcome, chances are you saw next to none of the equally legendary Cardinals-Astros showdown that made Carlos Beltran a bankable commodity. Baseball got over that foot-shooting thinking, too.

We have ten teams instead of eight in the playoffs for the same reason we have eight instead of four and four instead of two: more television programming, more television money. Fine with me. I’m already paying too much for cable, so it might as well include lots of baseball. Naturally you have to occasionally squeeze in a game here or there away from prime time, which is also fine. It’s baseball. October. Daylight. Sun. Shadows. All that. The tradeoff is it’s not perfectly timed to everybody’s comings and goings in this world. But that’s always been the tradeoff. Go curl up with some Ken Burns if you weren’t sure.

I assumed we knew that. Yet because Los Angeles is in the tournament, their 4:07 PM Eastern start Wednesday was, locally, a 1:07 PM Pacific start. I can see where that would be inconvenient, particularly for the Dodger fan who cannot escape his job or his class or other daytime commitment. I can see where, as suggested, it’s not optimal for the baseball viewer on either coast or in between for the same reason.

To which I say, oh, please, give me an inconvenient start time of 1:07 PM local for my Mets playoff game. Or 11:07 PM as was the case in 1999, live from Phoenix. Or five in the morning should the Mets ever draw the Hanshin Tigers in a real World Series. When your team has made the playoffs sporadically at best in your half-century of living, you don’t complain too loudly about when you have to show up or tune in. You go with it. You don’t wish to give the networks and other powers that be (though I guess the networks are the ultimate powers that be in baseball) too much rope with which to tie up your productivity and responsibilities, but if your team is in the playoffs, you’re pretty much a willing hostage to the process. Otherwise why would you sweat out 162 games to get to this cherished apogee of life?

TV isn’t having any more weekday afternoon games this year anyway. We get one more Game Five, a pair of Game Sixes and, if we’re good, a couple of Game Sevens. And then another four to seven between this weekend’s winners. Then, when those are over, we’ll all be in the same baseball-less boat.

Could be worse. We could all be from Chicago.

by Greg Prince on 14 October 2013 3:44 pm Forty years ago today, the National League champion Mets were visiting Oakland, trailing the American League champion A’s one game to none in the 1973 World Series…and they were about to post one of the 500 most Amazin’ wins of their first 50 years.

From The Happiest Recap (First Base: 1962-1973)…

***

The most encouraging sign for Yogi Berra was his ability to write STAUB onto his lineup card once again. He wasn’t completely healed by any means, but one shoulder of Rusty Staub, the manager decided, was better than any of his other options. Besides, this was the World Series. Rusty had been excelling in near obscurity as a Colt .45, an Astro and an Expo before coming to the Mets in 1972. He had never been anywhere near a Fall Classic before. Who knew if he’d ever have the opportunity again?

It was also comforting for Yogi to finish off his lineup with KOOSMAN, who gave him such a fine effort in Game Three of the NLCS and was the pitcher who turned around the Mets’ last World Series in its second game. Tom Seaver might have been an even more comforting presence, but because of the five-game LCS that ended Wednesday, Yogi’s ace (like Dick Williams’s main man Catfish Hunter, who’d also had to pitch a do-or-die clincher) wasn’t yet ready to go. Jerry Koosman was no last-ditch alternative, though. He’d made four postseason starts for the Mets in his career, and the Mets won every one of them.

Between Staub and Koosman, you might say the sun was going to shine on the Mets in Game Two. Or you could just look up at the unyielding Oakland sky and reach that conclusion for yourself. Before the day was out, the sun would be impossible to ignore.

Cleon Jones was the afternoon’s first atmospheric victim, in the bottom of the first when he lost Joe Rudi’s deep fly ball in nature’s light and it fell in for a double. “It was the worst, the absolute worst” Cleon attested of the view from left field. “I’ve never played in a major league ballpark where the sun was that bad.” Sol was a real SOB and Sal — Bando — was no nicer to Koosman than the sun had been to Cleon. He tripled home Rudi and scored three batters later on Jesus Alou’s double. Jones made amends with a leadoff home run in the second off Vida Blue, but though it was 2-1, this was going to be no facsimile to the 2-1 game of the day before.

Kooz had more trouble in the third: another triple (Bert Campaneris’s) led to another RBI (Rudi’s). Down 3-1, the Mets’ attack was reignited by Wayne Garrett’s solo blast in the third, making it 3-2. But Jerry couldn’t handle a little prosperity. With one out in the home third, he walked Gene Tenace, gave up a single to Alou and made a bad throw to first that let Ray Fosse reach. Now the bases were loaded, so now Berra acted. He removed Koosman and brought in Ray Sadecki. The veteran swingman caught a break when Williams put on the squeeze, but Green couldn’t deliver, making Tenace dead meat at the plate. Dick Green then struck out to keep the A’s off the board.

Blue’s grip on the Mets loosened in the top of the sixth when he walked Jones, who sped to third on Milner’s single. Vida’s day ended in favor of Horacio Pina, but it wasn’t Horacio’s day, either. After hitting Jerry Grote to load the bases, Don Hahn and Bud Harrelson delivered run-scoring singles to give the Mets the lead. Williams replaced Pina with Darold Knowles, who thought he had a force at home when Jim Beauchamp pinch-hit a grounder back to the mound. A bad throw let Grote and Hahn score, and the Mets had a 6-3 cushion to offer Tug McGraw when he came in to pitch the sixth.

Tug pitched the sixth without incident. He pitched the seventh, surrendering an RBI double to Reggie Jackson, which shoulder-strapped Staub could barely fling toward the infield. He pitched the eighth, and took care of the A’s in order. After the Mets threatened in the top of the ninth — Staub singled and Yogi pinch-ran Willie Mays — but didn’t score, Berra left Tug in to pitch the ninth as well.

Was it an inning too far for the fireman for whom the manager had been pulling alarms regularly for weeks on end? It didn’t appear to be, as McGraw coaxed a fly ball to center field from pinch-hitter Deron Johnson, and Tug had the benefit of possibly the greatest center fielder of all time standing out there. Mays stayed in the game after pinch-running, and in his prime, he was a sure thing to catch a ball like Johnson’s. Except Willie wasn’t in his prime — Sol was. The sun did the A’s dirty work again, blinding Willie, who admitted, “I didn’t see Johnson’s ball…I’m not alibiing. I just didn’t see it.”

The Say Hey Kid fell down in centerfield as the ball fell in front of him. In an instant, his stumble became the default example for generations of lazy writers and broadcasters who were eager to usher great athletes out of their sport once they “hung on too long”. After all, they tut-tutted, they shouldn’t want to wind up like Willie Mays.

In the there and then, Mays’s misadventure was less cautionary tale than a genuine trigger for Met crisis. The standard fly ball turned into a sun-splashed double, setting up an inning that crested with RBI singles from Jackson and Tenace. The A’s had tied the Mets at six.

The A’s tried to give the game right back to the Mets in the tenth. An error — Oakland’s third of the day — let the Mets push the go-ahead run to third with one out. From there, Harrelson sprinted ninety feet when Millan flied to Rudi in left. He evaded the tag of Ray Fosse by running to the catcher’s right. He crossed the plate with the run to make it Mets 7 A’s 6.

But Augie Donatelli didn’t see it that way. Donatelli, in one of the worst blunders made by a home plate umpire in World Series history, decided Fosse tagged Buddy. The replays showed otherwise. On-deck hitter Mays pleaded otherwise. Berra argued otherwise. Harrelson absolutely insisted otherwise: “I felt I was safe and I didn’t know I had been called out until I got near our dugout.”

Donatelli was unmoved. The Mets were done in the tenth. The game stayed tied, 6-6. McGraw stayed in to pitch the bottom of the inning, his fifth, which he did flawlessly, and the eleventh, too (after the Mets left two on). Tug had now gone six in relief and the game’s score remained stalemated.

It had already been a pretty darn intriguing affair, but it’s fair to say the twelfth inning is where things got really interesting. There was Buddy, doubling to start things off promisingly. There was Tug — still — left into bunt. He moved Harrelson to third and got on himself when his bunt blooped over the head of the charging Bando. With two outs, up stepped the old man who’d looked so overmatched by the elements in the field. Yes, Willie Mays was batting against Fingers, still dealing with the sun, albeit from a different angle.

But he dealt with it fine, bounding a one-hopper up the middle to score Harrelson. With the very last hit of his Hall of Fame career, Mays put his team up, 7-6, in the twelfth inning of a World Series game.

Willie and Tug each eventually scored when the A’s defense continued its daylong deterioration. The culprit in the eleventh, on two consecutive plays, was Mike Andrews, a bit player who committed a pair of errors (one on a grounder, one on a throw) that resulted in three Met runs. It also made him a target for Finley’s ire. The owner tried to disown the backup second baseman immediately, attempting to stash him on the DL despite his being perfectly healthy. In the coming days, in a nation where cynicism had ramped up in the wake of Watergate, Finley’s ploy would be seen through and Andrews wouldn’t be disappeared so easily. But at the moment, the only truth that counted was Mets 10 A’s 6, heading to the twelfth.

Tug McGraw continued to pitch. Perhaps Berra forgot he had at least a couple of other options. To begin his seventh inning of work, the southpaw got Jackson to hit a deep fly ball to center field. Willie ran to the wall to track it down. He didn’t. Jackson landed on third with a triple. After walking Tenace, Tug was done. George Stone got the call, which appeared a wrong number. Alou tagged him for a single to cut the Mets’ lead to three runs. After a forceout and a walk, the bottom line was the bases were loaded, McGraw was finished and Stone had to end a contest headed toward establishing a new record for longest — and nuttiest — World Series game.

Stone turned rock solid, popping up pinch-hitter Vic Davalillo and grounding out Campaneris. The game that wouldn’t end was over after four hours and thirteen minutes, and it belonged to the Mets, 10-7. The process was as exhausting as the result was exhilarating. It left the World Series tied at one before it could be packed up and flown to New York.

***

And the rest of the story? How it began? Where it went from here?

You’ll find out when you read The Happiest Recap (First Base: 1962-1973).

Print edition available here.

Kindle version available here.

Personally inscribed copy available here.

Pick up The Happiest Recap and get the whole Amazin’ story of the Mets’ most unbelievable stretch drive ever…and everything else.

by Greg Prince on 14 October 2013 1:41 pm I wasn’t watching the Tigers and Red Sox too closely Sunday night at first, but I did guess that Max Scherzer wasn’t going to throw a no-hitter despite carrying one into the sixth. Given the oodles of precedent at our disposal (Don Larsen, Roy Halladay and nobody else), not a tough guess to tender.

I figured, once the Tigers were up 5-0, that they were in pretty good shape to go up 2-0 in the series, but then I saw a comment on Twitter that suggested that with Scherzer striking out Sox at such a rapid pace, Detroit might as well be up 500-0. I suddenly had a weirdly foreboding feeling on behalf of the Tigers (for whom I’m nominally rooting since they’re the team without Shane Victorino). It’s been my experience that when a team seems completely in command of a given game but the scoreboard indicates they are not wholly out of reach of their opponent, the game isn’t over. Call it a wild guess.

I took in the sight of Scherzer accepting handshakes from his teammates when the seventh was over, his night apparently done with a 5-1 lead. He must’ve thrown more pitches than usual, I thought (I wasn’t paying a ton of attention by then), and Jim Leyland must be saving him for later in the ALCS. Winning this one first seemed paramount, but Leyland’s a universally acclaimed manager and he knows his pitchers better than I do. Maybe this wouldn’t matter; you never can tell if it will or if it won’t. I’d say I guessed wrong.

Not in front of the TV while the bottom of the eighth came together, I was surprised when I returned to realize the Red Sox had a genuine threat going. The bases were loaded and David Ortiz was coming up. I didn’t know which pitchers the Tigers’ bullpen carousel had dropped off on the Fenway mound or comprehended whether those were good or bad moves, but I was aware enough to think, hey, he could tie it up on one swing, as the cliché goes, but how likely is that? I should’ve guessed that it was very likely.

Now that it was 5-5 on Big Papi’s grand slam, I kind of figured this might go deep into the night if only because every playoff game at Fenway Park goes deep into the night. Nope, the iron-gloved Tigers couldn’t have been more helpful in helping the Red Sox score the winning run in the bottom of the ninth. If I was conspiratorially minded, I would have guessed Detroit was on the take at Fox’s behest to make these playoffs more entertaining to a broader audience. That, by the way, wouldn’t be a serious guess…I don’t think.

Given how dramatically the Red Sox roared from behind, nobody wasn’t willing to call this game an all-time classic and declare it would be remembered forever. I’ll go with the classic part but I’m going to guess it gets forgotten more quickly than you’d guess. There are so many rounds and so many games and so many teams that the second game of a League Championship Series — no matter that it includes a phenomenal pitching performance trumped by a breathtaking comeback — is bound to get a little lost over time. Red Sox fans won’t forget it. Tigers fans won’t forget it. The rest of us are on our own. Just consider the note that emerged once Ortiz’s blast cleared the fence and eluded Torii Hunter’s tumbling reach. His grand slam was the third in the history of postseason play to tie a game, joining Ron Cey’s from the 1977 NLCS and Vladimir Guerrero’s from the 2004 ALDS. I ask you: when was the last time you heard anybody invoke those as classic and unforgettable? I don’t approve of popular amnesia, it just happens.

First guess. Second guess. Lucky guess. Baseball’s the ultimate guessing game. That’s what makes it so much fun to play along with at home.

by Greg Prince on 13 October 2013 3:06 pm Two games, two runs, two 1-0 results. Pitching! Defense (of which pitching is a key component)! No hitting! Almost literally, in one case!

Michael Wacha and bullpen outlasted Clayton Kershaw and bullpen in the afternoon, while Anibal Sanchez and bullpen totally edged Jon Lester and bullpen at night. It wasn’t exactly Marichal and Spahn going mano-a-mano for 16 innings (and all of 14 minutes longer than the Tigers and Red Sox), but it was certainly taut. The Tigers took a no-hitter into the ninth inning in Boston and settled for a five-man one-hitter. Three Dodgers gave up only two hits…but also the solitary run in their loss at St. Louis.

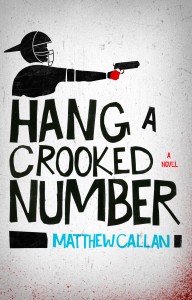

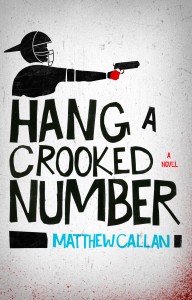

So much pitching. So little scoring. An absolute paucity of what baseball folk like to call crooked numbers. But if you require wayward numerals and the spirit that informs them, I suggest you and your electronic device get together with Matthew Callan.

Matthew lets it all hang out at his Scratchbomb blog, dissects games as they were first beamed on the Replacement Players podcast and occasionally chimes in on an array of Metsian matters at Amazin’ Avenue. He has cast an archivist’s light on 1988, injected welcome dollops of delicious texture into retelling 1999 and generally looks out for the Mets fan’s psyche’s best interest. And, because his imagination adheres to few boundaries, he’s written and released a positively Callanian novel, Hang A Crooked Number.

It’s got baseball. It’s got espionage. It’s got a good deal more layered within. It’s got enough Mets references to keep somebody like me who tends to be fiction-averse from growing too terribly antsy. It’s got, as it must when you consider the genres it’s blending, the Moe Berg Society, a could-be consortium named for the legendary catcher who was a spy and whose last words were actually reported to be, “How did the Mets do today?” It’s got baseball. It’s got espionage. It’s got a good deal more layered within. It’s got enough Mets references to keep somebody like me who tends to be fiction-averse from growing too terribly antsy. It’s got, as it must when you consider the genres it’s blending, the Moe Berg Society, a could-be consortium named for the legendary catcher who was a spy and whose last words were actually reported to be, “How did the Mets do today?”

Berg died on May 29, 1972. The Mets won that Memorial Day matinee, 7-6, on the strength of a Ken Boswell three-run homer that tied the Cardinals and a passed ball that topped them in the visitors’ ninth at Busch Stadium. Jerry Koosman — for whom a character in Matthew’s novel is named (but not necessarily just like in Growing Pains) — then came on to pitch relief and was awarded the win rather than the save since the nominal pitcher of record, Tug McGraw, had allowed three Redbirds runs in the bottom of the eighth on consecutive triples; this, apparently, was when they used to permit the hanging of crooked numbers in St. Louis. One of those three-baggers was surrendered to a pinch-hitting catcher, Jerry McNertney, who I don’t think was a spy but I’m pretty sure infiltrated every other pack of cards I bought in 1971 by going undercover as a coin.

Moe Berg was 70 when he reached his end, having been injured in a fall a little prior to that fateful Monday, so, no, the Mets managing to come back in such stunning fashion isn’t what killed him.

You can learn more about Hang A Crooked Number here, which will you enable you, if you so choose, to download it to whichever contraption you choose to read e-books. Matthew is also accommodating those who eschew tablets, Kindles and whatnot with ePub and PDF versions. Don’t let technological issues or a lack of hitting with runners in scoring position separate you from Matthew Callan’s talent.

***

A few other links I’ve been meaning to share between innings big and small:

Patrick Flood went pro a few years ago with his immense writing abilities. He remembers what it was like to blog the Mets with a credential dangling from his belt loop at narrative.ly.

Another familiar name from the Metsosphere, Howard Megdal, goes deep at the same site, reflecting on his commitment to raise his daughter(s) the (W)right way.

Something as simple as delivering the mail around Citi Field turns out to be fascinating when its story is told by the Times’s Tim Rohan.

I had no idea what it meant to Tim Byrdak to extend his “long and meritorious service” as a Met in 2013, but ESPN’s Chris Jones explains it thoroughly.

And if you didn’t hear how the WFAN Mets era ended on Closing Day, give it the good listen its passing deserves.

by Greg Prince on 12 October 2013 1:48 pm That new hit cable show Masters of Postseason was on last night, starring the venerable Carlos Beltran and narrated — if you didn’t mind mixing and matching your media — by the dynamic Vin Scully. Or is Scully venerable and Beltran dynamic? Actually, I’m pretty sure both are each.

You didn’t need to listen to KLAC via the MLB At Bat app to get what our former franchise player was up to in Friday’s marathon Cardinal win over the Dodgers at Busch Stadium. All you had to do was stare in awe at TBS and you could easily observe Carlos Beltran being directly responsible for all three runs his team gathered on offense and actively defending against a critical run via vintage defense.

He doubled in a pair of runs off Zack Greinke (8 IP, 10 K) in the third to even the score at two.

He nailed Mark Ellis at home on a 9-2 twin killing in the tenth (never mind that Yadier Molina didn’t exactly make a tag…and that sending Ellis may not have been the swiftest move imaginable).

And in the bottom of the thirteenth, he drove in Daniel Descalso from second to give St. Louis a 3-2 victory and the definitive early edge in what one wag is calling the Smug vs. Smog NLCS.

Beltran came up for that last swing with a runner in scoring position, and the runner scored. Typical Beltran, give or take…well, you know. His lifetime postseason batting average with runners in scoring position is .429 and he owns a bunch of other numbers that are comparably impressive. He’s helped push three different franchises to the seventh game of a league championship series. Maybe this year he nudges this one a little further.

That would be sort of a shame, even if you don’t find inevitability wholly unlovable, because if the Cardinals go to the World Series, then the Dodgers don’t. And if the Dodgers don’t, neither does Vin Scully.

I took the advice of several savvy people and did for last night’s Game One what I did for a bit of the 2006 NLDS’s Game Three. I turned the sound down on national television and turned the sound up on whatever device would welcome me to Scully letting me know it was time for Dodger baseball. I don’t necessarily seek Dodger baseball most late nights from L.A. but Dem Erstwhile Bums is half of all we got left in the N.L. If it’s going to come down to Smug vs. Smog, give me the voice that’s been coming in crystal clear and free of pretension since about ten minutes after Abner Doubleday didn’t invent the Grand Old Game.

Don’t take this as a rooting interest, per se, but if the Dodgers wind up playing the Red Sox in the World Series, Game One will feature an announcer who’s been describing baseball forever describing baseball in a ballpark that’s been hosting baseball since 15 years before that announcer was born. Not many active entities have remained precisely in place since I became enamored of this sport in 1969. Yet in my baseball lifetime, Vin Scully has always announced Dodger games and Fenway Park has always been the home of the Red Sox. Each has withstood progress’s army of steamrollers to not so much “remind us of all that once was good,” per Field Of Dreams, but to continue to represent the pinnacle of the American experience — National Pastime division.

Scully began his broadcasting career reporting college football from frigid Fenway in 1949. He broke into the big leagues as Red Barber’s and Connie Desmond’s junior partner at Ebbets Field in 1950. He shifted west to keep doing what he was conceived to do in 1958. He was recognized with the Ford C. Frick Award in 1982, the sixth announcer to be so honored by the Hall of Fame. The NBC gig that eventually crossed his path with that of a little roller up along first didn’t materialize until 1983. Before that, Vin Scully did the Dodgers, took on myriad postseason radio assignments, called the NFL on CBS and spoke into who knows how many microphones for who knows how many different events, yet it wasn’t until he was 65 that he went truly national as baseball’s undisputed lead voice. He was the sound of NBC for seven seasons, encompassing Bill Buckner’s error, Kirk Gibson’s homer and much more.

NBC lost baseball to CBS in 1990. Vin Scully kept going. He was at his job, on the air from St. Louis last night, in 2013. I listened as I have a few dozen times since I’ve had the technology available to me. The TBS announcers, the Cardinal announcers, the ESPN Radio announcers, even the other Dodger announcers for the innings Vin takes a break…none of them makes a postseason game as special as Scully does.

And you know why he makes it special? Because he treats every game as special. In a sense, this could have been a Dodgers at Cardinals game in the middle of the “regular year,” as he terms it (except he wouldn’t have made the road trip east of the Rockies at this stage of his life). If I were a Dodgers fan, I’d be close to expert on every Dodger opponent because for all his implicit advocacy on behalf of the team he’s personified for 64 seasons, Scully is best when the opponent is at bat. Vin told a story about David Freese in Game One. It wasn’t a big deal, just some background on how he had to share an apartment with a college buddy when he was a rookie, but damned if I wasn’t caught up in David Freese’s prior living arrangements. He gave me the same kind of skinny on Molina, on Beltran, on every Cardinal.

There’s something so respectful about that. I’ve been hearing him do that since the first time I heard him in his native habitat, on 790 KABC in 1996 when I was visiting L.A. I don’t remember what he was telling me about Astro third baseman Sean Berry, but I remember being struck that he took the time to inform me and that he wove it so seamlessly amid the balls and strikes. It was and is a small thing, but what are a baseball game and a baseball season and a baseball postseason are nothing if not a billion small things arranged in a dazzling mosaic?

As last night plowed into extra innings and past 1 AM Eastern, Vin Scully didn’t miss a beat. The giveaway towels made it “look like a snowstorm in the grandstands”. The clothing of choice in those seats? “When you come to St. Louis, it’s like an internal hemorrhage in the ballpark, nothing but a sea of red.” Conference on the mound? “Ellis covering his mouth with his glove and Wilson covering his mouth with his beard.” Yasiel Puig not coming through with a big hit? “He looks so frustrated — on one of these swings he’ll break the laces in his shoes.” Not a second of annoyance that this game wouldn’t end in his team’s favor.

“It’s a four-hour game,” Scully, 85, remarked with innings to go before he slept, “and well worth every minute of it.”

All of those pithy descriptions were transcribed courtesy of @VinScullyTweet, a “tribute” account dedicated to a man you can have fun affectionately imitating but even Twitter knows enough to not mock. When Beltran came up with the winning run on second, it felt as if not just Carlos had set the stage for his unfolding moment, but Vin had, too. During every at-bat Beltran had all night, Scully smoothly and hypelessly discussed the hitter’s great knack for producing in October. With him facing Kenley Jansen, it felt as if a narrative Scully started writing a dozen innings and close to five hours before was poised to reveal its final chapter.

Never mind that I had the television on and it was two to three pitches ahead of the app. I saw Carlos Beltran’s walkoff hit with my own eyes but I couldn’t swear it happened it until I heard it through Vin Scully’s mic. It was well worth every second.

by Greg Prince on 10 October 2013 4:00 pm You knew the Cardinals would beat the Pirates, didn’t you? The Cardinals are the new inevitables of the National League. They may not win the World Series. They may not win the pennant. But they always stick around because they never really go away. They trump most of the good stories that orbit in their atmosphere. If you don’t see them winning everything or most things in a given year, just wait another year and they will. They’re not going anywhere.

This is admirable on its face. If it was some other franchise pulling it off, it would be downright inspirational. Surely it is aspirational. But it’s the Cardinals. It transcends the brand of simple “they win all the time” aggravation we used to associate with the Yankees or Phillies or Braves. By now it’s more than what they did to us in 2006 or what we couldn’t do to them a couple of times in the 1980s.

The Cardinals can be impeded, yet they cannot be brought to a full stop. Old Man River has nothing on the team whose city he keeps on rollin’ by. They don’t retain the services of probably the greatest hitter of this century. They say goodbye to a manager and pitching coach who were deemed essential to their success. They turn over their roster so completely from their first world championship of the current era to the present that the only core left from it consists of two of the three players we most closely associate with our bitter, bitter loss to them. And the biggest name they’ve added in the past couple of years? That would be the third player we most closely (if not always fairly) associate with that bitter, bitter loss.

The Cardinals aren’t flawless but they are the kings of resilience. Did you know that in 2012 the Cardinals gave up a 3-1 lead in the seven-game National League Championship Series and in fact lost that series to the Giants? Think of the teams for whom that would constitute a crisis of epic proportions. “They were one game from the World Series but were so shaken by how they blew their chance that they never recovered.” The Cardinals? Do they appear shaken? Stirred? Did they suffer at all?

Not really. The Cardinals lost Albert Pujols to free agency. Anybody heard from Pujols lately? The Cardinals get hit by injuries same as everybody else, but no, not the same as everybody else (Matt Harvey should forget about Tommy John and request the Adam Wainwright surgery). They just plug in somebody else they have handy, they finish first and they finish off the Pirates.

Pittsburgh reawakened as a baseball town in 2013. Andrew McCutcheon emerged as a full-fledged MVP candidate. The twenty-season losing streak was shattered and PNC Park at last earned its moments in the postseason spotlight. But when they had to fly back to St. Louis to determine how much more life their October contained, you knew there wouldn’t be much. Wainwright could’ve had a bad game…but you knew he wouldn’t. Molina could’ve called for the wrong pitch at the wrong time…but that wouldn’t be “Yadi” now, would it? There was one close moment when the Bucs briefly rallied on a Cardinal miscue, but that wasn’t going to stick. And whatever the Cardinals gave away in the top of that inning, they took back in multiples in its bottom.

It was inevitable.

Wainwright. Molina. Beltran instead of Pujols. Matheny instead of LaRussa. Michael Wacha instead of Chris Carpenter. Matt Carpenter in addition to Matt Adams. Trevor Rosenthal and a cast of closers. It’s not that they’re a classic juggernaut — their 97 wins this year are the most they’ve accumulated since 2005 and they won their recent world championships on the strength of 83 and 90 wins, respectively. It’s not that they’re a budgetary behemoth — their total payroll ranks only eleventh in the major leagues. They’re just…they’re just the Cardinals. And they fail to cease being the Cardinals.

They’re not “the Yankees of the National League,” a phrase I’ve heard now and then that I think misses a couple of points. First off, the Yankees, at their height, weren’t the Yankees of the American League. They were the Yankees, period. They paid and played in their own league. That they were associated with one or the other halves of MLB is a technicality in their business plan. These are the haughty bastards who sell memberships to something called Yankees Universe, for crissake.

Second, the Cardinals are the Cardinals of the National League. They are the signature outfit of the Senior Circuit, not quite dominant or overbearing enough to eclipse everybody in sight but the one team that almost always clicks on every cylinder. They win with pitching. They win with offense. They win with “fundies”. They win with dramatics. They win with strategically signed veterans. They win with an assembly line of youngsters. They draw loads of customers and engender incredible if showy loyalty. They are a model for 14 other teams to copy yet singular enough that whatever it is they’re doing isn’t easily duplicated. (They also seem to be the archrival of everybody in their division, at least according to their N.L. Central neighbors.)

The Cardinals fill a role in the National League that for a long time was taken care of by their next opponent, the Dodgers (talk about a matchup that only the blond villain from The Karate Kid could love). Even when they weren’t necessarily winning divisions or pennants, the O’Malley Dodgers pretty much ran the National League in the ’60s and ’70s. The Dodger Way was spoken of with the kind of reverence currently assigned the Cardinal Way. It was appropriate. L.A. always competed, usually contended and a couple of times conquered. The Dodger Way deteriorated over time as its ownership situation spiraled into chaos (ahem) and the bloom came off the blue, though they were rarely godawful on the field.

Godawful practically never enters the Cardinal vocabulary. They haven’t endured consecutive losing seasons since 1994 and 1995. Before that, it was 1958 and 1959. Three losing in a row? Try Woodrow Wilson’s second term, which was more than nine decades ago. And once the playoffs expanded to include four and then five teams from each league? Forget about the Redbirds flying away. They’re on their eleventh postseason berth in the past eighteen years, their eighth NLCS in fourteen Octobers.

They outlasted us in 2006. They brushed aside the Brewers in 2011 right after dispatching the Phillie rotation for the ages. They rendered Natitutde irrelevant in 2012. They made the potentially feelgreat story of the Pirates sink before it could fully gather steam. They and their “best fans in baseball” will be praised to the nausea-inducing hilt in the days ahead. Through gritted fingers, I am impelled by honesty to type that on some level the whole Cardinal enterprise deserves the thumbs that are about to be raised high in their direction.

The Dodgers took on a ton of contractual obligations and promoted Yasiel Puig from the minors yet were no sure thing to make it this far. The Cardinals just kept being the Cardinals. Their presence here was inevitable.

by Greg Prince on 10 October 2013 10:20 am Forty years ago today, the Eastern Division champion Mets were hosting Cincinnati, tied two games apiece with the Western Division champion Reds in the National League Championship Series…and they were about to post one of the 500 most Amazin’ wins of their first 50 years.

From The Happiest Recap (First Base: 1962-1973)…

***

It was a good day to quit, to give up, to throw in the towel…but that applied only to those who played their games in Washington. In the nation’s capital, this Wednesday would be marked by a historic resignation. Spiro Agnew, the Vice President of the United States, under grand jury investigation for tax evasion, cut a deal and vacated the post to which he’d been re-elected in a landslide less than a year earlier.

In New York, however, the thought of quitting never crossed anybody’s mind, certainly not in Flushing where the Mets, unlike Agnew, had been toughened by autumn’s adversity. Why shouldn’t they have been? They were losing the National League East by the kind of landslide that had buried George McGovern the previous November, yet turned a midsummer 12½-game deficit into a 1½-game mandate to govern their division. It was the kind of stuff kids were taught about in social studies class…Mets-in-first destiny, if you will.

But that was just the primary. In the playoff series projected by DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN-style gun-jumping pundits to exist exclusively in a Red state, the party of blue and orange was locked in a race that was too close to call. Four of five precincts had reported. The Mets had won two, their opponents two. The time had come to cast the deciding vote.

Yogi Berra’s choice for Game Five was perfectly clear: Seaver Now, More Than Ever. That one was obvious enough. Of course Tom Terrific was going to start the Mets’ first-ever postseason win-or-go-home game. But the manager had another decision to make. After writing in the same eight position players in the same eight spots in the batting order for four games, Yogi was deprived of his cleanup hitter. The injury Rusty Staub absorbed in his right shoulder the day before0 prevented him from swinging a bat or throwing a ball (Staub batted left but threw right). Without one of the rocks of his lineup, the skipper had to scramble.

The answer he came up with was the one that had been available to Met managers longer than any other in the history of the franchise.

Ed Kranepool hadn’t started a game since September 15, when he spelled John Milner at first base. He hadn’t started a game in the outfield since taking a turn in right on July 16. But Berra wasn’t asking him to play right. He instead moved Cleon Jones, the better outfielder, from left to right in deference to Sparky Anderson deploying a left-leaning lineup against righthanded Seaver. Krane was thus stationed in left, terrain with which he wasn’t completely unfamiliar, having started there thirty times when Yogi was clustering whatever healthy Mets he could find when he was strapped for his usual starters before September.

There wasn’t any terrain at Shea Kranepool couldn’t have known by 1973 seeing as how he had been a part of the team longer than the stadium had stood. He was the one Met who could claim to have been a part of every Met squad since the first one, in 1962. He was just a kid then, 17 and getting his first taste of the bigs under Casey Stengel that September in the Polo Grounds. Krane persisted across the ’60s, never achieving the stardom the Mets wished for him, but remaining relatively young and relatively useful. His investment of time as a Met — and the Mets’ investment in him — paid off when he contributed significant base hits as half of Gil Hodges’s first base platoon in 1969.

By the middle of 1970, Kranepool was a Tidewater Tide, not hitting and not happy to be Met property. He was presumed gone when he was put on waivers, but no other team scooped up his services and he returned to the major league club before long. Having experienced the near-death of his professional career, Ed underwent a renaissance in 1971, putting up the best numbers of his life and getting back into Hodges’s good graces. He was less effective in 1972 and less effective, still, in 1973, but he was on the roster, he knew how to play the outfield and nobody had ever been more of a Met than Ed Kranepool.

“I’ll be out in Pete Rose’s Rose Garden,” the crafty Bronx-born veteran promised upon learning of his assignment. “I just hope I bloom.”

After Tom Seaver avoided a patch of proverbial crabgrass in the top of first and escaped a bases-loaded jam, Ed Kranepool’s hope came true quickly. Against Jack Billingham, the Mets filled the sacks on singles from Jones and Felix Millan and a walk to Milner. The Krane was up next and he delivered a two-run single to left. The Met who’d been around longest put the Mets on the board first.

Down in Washington, the buzz over Agnew was overriden in at least one branch of government. Found among papers released five years after the 1999 death of former Supreme Court justice Harry Blackmun was a note handed to Blackmun by fellow justice Potter Stewart, dated October 10, 1973. The note was jotted down by Stewart’s clerk and delivered to him while the highest court in the land was in session:

V.P. Agnew just resigned!!

Mets 2 Reds 0

Back in Flushing, the honorable George Thomas Seaver presided over the 2-0 lead with liberty and justice for all…or guts and guile, at any rate. This wasn’t quite the Seaver of the preceding Saturday when he blew away most of the Reds in a losing cause. Going on three days’ rest, he had to rely on his offspeed arsenal and the guidance of his catcher, Jerry Grote. The combination got Tom through the third with a 2-1 lead after Dan Driessen’s sacrifice fly halved the Mets’ advantage, and it functioned effectively through the fifth despite Tony Perez singling Pete Rose home from second to knot the score. Billingham was doing his share of presiding as well, as the Mets’ offensive drought reached arid proportions. From the fifth inning in Game Three through the fourth inning of Game Five, encompassing twenty innings in all, the Mets had scored only three runs.

Change, however, was at hand. It started with Wayne Garrett — so hot in September yet ice cold in the playoffs — doubling to lead off the bottom of the fifth. Millan bunted to Billingham, who had a play on Garrett at third. He threw to Driessen who stepped on the bag for the force…which was a rookie mistake at the worst possible moment for Cincinnati because the force wasn’t on. It meant Garrett was safe at third while Millan took first. Wayne dashed home and Felix ran to third when Jones doubled to put the Mets back in front, 3-2. Anderson pulled the righty Billingham and went to a lefty, Don Gullett, seeking to gain an edge on lefty-swinging John Milner. But Milner didn’t have to swing; he walked to load the bases.

The next batter scheduled was another lefty, Kranepool. If the longest-serving Met could deliver one more blow, it would give 50,323 fans an emotional jolt. But what if the oldest Met were to come through here? Not just the oldest Met, but the most highly decorated player in all of baseball in the dimming twilight of his storied career?

Willie Mays hadn’t played since September 9. He’d announced his retirement, received an outpouring of affection on a night dedicated in his honor on September 25 and was in every way but official done as a player. Except he was on the active roster and he was still Willie Mays. So Yogi told the Say Hey vet — a righty, in case anybody’d forgotten during his lengthy period of inactivity — to grab a bat and hit for Kranepool.

The crowd loved it. How could it not? As Anderson’s next reliever, Clay Carroll, came on for the righty-righty ritual, anticipation built. Could the man who’d hit 660 homers since 1951 add to his bulging portfolio of legendary moments? Might the last of the New York Giants perform once more in a larger-than-life capacity?

Let’s just say that unlike Spiro Agnew, Mays wasn’t ready to quit. He attacked Carroll’s first pitch and sent it…oh, inches when measured on a line, but as high as it needed to be. It was a Baltimore chop practically straight up off the plate. By the time it came down, everybody was safe. Millan scored from third, Jones moved up from second, Milner replaced him there and, with the final hit he’d record in National League competition, Willie Mays made it to first base.

Twenty-two years and one week after standing in the on-deck circle as a nervous rookie while Bobby Thomson won the pennant for the Giants, Willie Mays extended the Mets’ lead in a potential pennant-clinching contest, 4-2…the same sequence of numbers that nowadays constituted his age.

Two more runs would score in the fifth to give Seaver a 6-2 lead. Jones moved from right to left. Don Hahn moved from center to right. And Mays stayed in to play center, where he’d catch the final out of a 1-2-3 sixth. In the bottom of the inning, Seaver led off with a double and scored on a Jones single. His lead was 7-2 when he started the seventh. He kept it as such then, and again in the eighth.

Finally, it came down to Tom Seaver and three outs for the pennant. It was an ideal setup, especially after Cesar Geronimo led off by lining out to Millan to start the ninth. But it wasn’t an ideal environment to complete such an Amazin’ story. Unsavory elements of the restless crowd began trickling onto the field. Play had to be halted a couple of times, impeding Seaver’s rhythm. While Tom attempted to cope, pinch-hitter Larry Stahl (a Met teammate of Seaver’s in 1967 and ’68) singled. Another pinch-hitter, Hal King, walked. Then Rose did the same to fill the bases with Reds. The lead was still five runs and the pitcher was still Tom Terrific, but now was the time for neither arithmetic nor reputation. Yogi knew he’d gotten plenty out of Seaver. He also knew how to pick up the phone and ring the bullpen.

In came Tug McGraw, the signature Met of the improbable drive that had brought this team to this juncture. It wasn’t just good strategy to have him go for the last two outs. After Kranepool and Mays set the stage for a pennant-clinching, karma almost demanded Tug’s presence on the mound to finish the job.

Joe Morgan, the dangerous second baseman with two MVP awards in his not-too-distant future, popped to Bud Harrelson at short for the second out.

Driessen, the callow third baseman who wore the defensive goat horns from forgetting to make a tag, grounded to Milner, who flipped the ball to McGraw.

Three out.

In a six-week blink, the Mets earned the championship of the National League. In a much more condensed time frame, Shea’s playing surface was stormed as if Bastille Day II had been declared. Observers universally agreed this was a far less innocent display of joy than the ballpark had been engulfed by in 1969. The Reds, running for their lives, suggested New York was hardly a part of America and that these people coming after them might have felt more at home in a zoo. The Mets were forced to take quick cover, too, and didn’t much indulge the baser instincts that were let loose by their triumph.

“Eerie,” Tug described the reaction. “These people,” Tom asserted, “don’t care anything about baseball, or that we won. It’s just an excuse to them to go tear something up.”

In the safety of the victorious clubhouse — and wherever millions of true Mets fans celebrated in sincerity — the tenor turned suitably upbeat. All agreed there was something to this power of positive thinking McGraw kept disseminating and to not being resigned to your supposed imminent demise, no matter the assessments set forth by the nattering nabobs of negativity. Agnew’s pet phrase, as coined by speechwriter William Safire, referred to his strawmen in the press, though the now former VP could also have been talking about the poll that ran in the Post during the summer. The survey asked readers who should be fired for the disaster the Mets had become: board chairman Don Grant, GM Bob Scheffing or good old Yogi.

At this moment, all were gainfully employed and swimming in champagne.

Beyond bromides about never giving up or giving in, it might have also been worth noting that when you have pitching like the Mets showed in this series, there was no logical reason to think you couldn’t hang with and ultimately defeat the best of them.

In five games against the humble 82-79 Mets, the mighty 99-63 Reds of Rose, Morgan, Perez and Bench accumulated a grand total of eight runs. Berra’s starting rotation of Seaver, Jon Matlack, Jerry Koosman and George Stone permitted 26 hits in 41⅓ innings while McGraw threw five shutout frames of relief, entitling him, as the team’s indispensable fireman down the stretch and into the playoffs, to bellow for the record the most famous last words uttered on behalf of the 1973 National League champions:

“YOU GOTTA BELIEVE!”

***

And the rest of the story? How it began? Where it went from here?

You’ll find out when you read The Happiest Recap (First Base: 1962-1973).

Print edition available here.

Kindle version available here.

Personally inscribed copy available here.

Pick up The Happiest Recap and get the whole Amazin’ story of the Mets’ most unbelievable stretch drive ever…and everything else.

Seriously, get it. It’s good.

by Greg Prince on 9 October 2013 4:29 pm “Hey Pop, the time you hit Hazen in the mouth, was it worth 30 years?”

—Paul Crewe, The Longest Yard

“That’s how you become great, man. Hang your balls out there.”

—Jesus at the CopyMat, Jerry Maguire

The Mets have been to the postseason seven times. I cherish all seven appearances, including the one that crested and crashed 25 years ago tonight.

That was 1988. Hardly any Mets fan cherishes 1988. Scioscia happened in 1988. Scioscia tends to blot out everything.

• 100 Met wins for the third and (thus far) final time.

• A 15-game Met romp over the National League East, created by a 31-11 start, confirmed by a 29-8 finish and accented by a knack the Mets had in prevailing over the ultimate bridesmaid Pirates in every showdown series they played that summer.

• The individual exploits of, among others, David Cone, Darryl Strawberry, Kevin McReynolds, Dwight Gooden, Ron Darling, Randy Myers and Gregg Jefferies.

• Three National League Championship Series victories — in Games One, Three and Six — that were as impressive as they were entertaining.

• A seventh game that determined whether or not the Mets would compete for another world championship.

The Mets got to that precipice, on October 12, 1988, three days after Scioscia. They tripped and fell off of it and that was the end of 1988’s goodwill forever more, which is too bad because, well, how often do the Mets get even that far?

Seven times, give or take a game.

I watch these current playoffs. I feel the engagement of the crowds. I pick up on the vibe that every pitch matters, that every swing can shift momentum, that every time a ball goes somewhere, it could very well be headed into history. That’s the reward for getting here, to live on an emotional high wire until either someone knocks you to the ground or elevates you even higher. That’s what it was like for Rays fans until their team was dispatched by the Red Sox last night. That’s what it will be like for one group or another tonight and again tomorrow. Somebody will go on, somebody else will go home.

It will have been worth it. It was worth it in 1973, even when Darold Knowles popped up Wayne Garrett. It was worth it in 1999 when Kenny Rogers lost the strike zone while Andruw Jones stood idly by. It was worth it in 2000 when Mike Piazza could muscle a Mariano Rivera cutter only so far. It was, I swear to you, worth it in 2006 when one of the great postseason players of his generation looked at a nasty curveball on oh-and-two.

And it was worth it in 1988 when Orel Hershiser froze Howard Johnson to conclude Game Seven three days after Mike Scioscia homered against Dwight Gooden to tie Game Four, the result of which seemed to be in the bag but, once Scioscia struck, was now rolling loose for anybody to grab.

The Dodgers grabbed it. They evened the score in the ninth, took and held a lead in the twelfth, won Game Five the following afternoon, withstood a Game Six loss the night after that and, come Game Seven, earned a trip to the World Series.

The Mets, who had been three Gooden (or maybe Myers) outs from a three-one lead in the NLCS, went home, but I still say it was worth it.

For seven games played in a span of nine days, it was worth it. The Mets were still playing in 1988 when almost everybody else wasn’t. Had they succeeded — and they came far closer than is generally appreciated — they’d have kept playing. If they’d kept playing, perhaps they win a third world championship. Or they lose to Oakland as they did in 1973. There was no saying once what could’ve happened once they bowed to Los Angeles in ignominious fashion in Game Seven.

But they got to Game Seven. They got to Game Five and Game Four and Game Two, same as they got to the games they won in those playoffs. It was so much better than it was the year before when they got to the end of the 1987 season several games short of qualifying for the postseason. It was so much better than it would be in the ten succeeding seasons that came up either just shy of October or expired well in advance of August.

This is where you wanna be, where the Pirates and Cardinals are tonight, where the A’s and the Tigers will be tomorrow night, where the Red Sox and Dodgers have already assured themselves of being this weekend and, yeah, where the Rays, Braves, Indians and Reds have been only to exit earlier than they would’ve liked in 2013. Their fans got to the next stage, a stage we haven’t entered in seven going on eight years. It was our stage in 1969, 1973, 1986, 1988, 1999, 2000 and 2006. We didn’t always own it at the moment the curtain was lowered, but good god how I loved our time upon it, no matter how long it lasted.

Scioscia and his teammates pulled the wings off of 1988. There’s no whitewashing it. His home run was a dagger through the heart, a kick in the head, any metaphor indicating damage to a vital organ or body part you care to name. The loss of that series prevented a great year from going down as extraordinary. But it was a great year. It was great because we got as far as we did. It was a terrible way for it to go awry, but what isn’t a terrible way to not win a championship?

You can fall out of contention and watch other teams’ fans hang on every pitch or you can immerse yourself in October on account of your own team’s actions, knowing all the while that you very well risk a Scioscia blowing up in your face. It’s not even a choice. Give me a 4-2 lead in the ninth inning of a Game Four every time and I’ll take that risk. The risk is its own reward this time of year.

Meanwhile, at Sports On Earth, Jason shares his thoughts on what might be going through the minds of some other fan bases.

by Greg Prince on 8 October 2013 1:08 pm Forty years ago today, the Eastern Division champion Mets were hosting Cincinnati, tied one game apiece with the Western Division champion Reds in the National League Championship Series…and they were about to post one of the 500 most Amazin’ wins of their first 50 years.

From The Happiest Recap (First Base: 1962-1973)…

***

In an era when comedians could get a cheap laugh at the expense of the violence-riddled NHL — “I went to a fight and a hockey game broke out” — a touch of Broad Street Bullying came to the intersection of 126th Street and Roosevelt Avenue. Except unlike the Stanley Cup-bound Philadelphia Flyers of 1973-74, whose brawl-encompassing season was about to begin, the Cincinnati Reds saw their attempt to win with their fists what they couldn’t win with their skills amount to naught.

That’s because by the time they decided to come out swinging this sunny Monday at Shea Stadium, they had already had the hell beaten out of them where it counted.

The Mets and their perennial offensive blues were reflected in the first seventeen innings of this NLCS when they provided Tom Seaver and Jon Matlack with all of two runs for their brilliant efforts. Finally, in the ninth inning of the second game, the Mets bats woke up. The four runs that secured the Game Two win must have served as a shot of caffeine because those bats stayed wide awake as the series set down in New York.

For the first time since the last time Jerry Koosman started, eight days earlier in Chicago, the Mets scored in the first inning. The trigger man was again Rusty Staub, providing his second solo home run of the series. The early lead grew quickly. In the bottom of the second, Wayne Garrett’s bases-loaded sacrifice fly and Felix Millan’s RBI single extended the Met lead to 3-0 and ended Cincy starter Ross Grimsley’s day. With two on and two out, Sparky Anderson opted for his lefty reliever, Tom Hall, to face the sizzling lefty Staub.

Rusty was not to be faced down. He took Hall on a tour of downtown Flushing via his second home run of the game and third of the series. The Mets presented Koosman with a 6-0 lead. It got trimmed in the third when Denis Menke homered and three singles strung together a second run. But Kooz got half of that back on his own, driving in Jerry Grote in the bottom of the third to make it 7-2. And in the bottom of the fourth, Cleon Jones and John Milner each knocked in runs.

It was 9-2, Mets. They had scored in every inning dating back to the ninth the day before. Despite their starter’s earlier hiccup, their pitching now appeared on Kooz control. Jerry struck out Roger Nelson (Anderson’s fourth pitcher of the day) to begin the fifth. Pete Rose touched him for a single, but then Joe Morgan grounded to Milner at first to start a 3-6-3 double play to end the inning.

Except in the middle of that otherwise routine twin-killing, Rose got it into his head to reach out and do more than touch Buddy Harrelson. That’s how Buddy saw it from his vantage point at the business end of the onrushing Rose. “He came into me after I threw the ball,” the skinny shortstop swore. “I’m not a punching bag.” The much larger Rose resented the implication that he played dirty, testifying he slid hard but clean.

Buddy might have added he wasn’t a sliding pit, either.

“And a fight breaks out! A fight breaks out!” was Bob Murphy’s call of the scene once the DP was turned. “Pete Rose and Buddy Harrelson! Both clubs spill out of the dugouts, and a wild fight is going on! Jerry Koosman’s in the middle of the fight! Everybody is out there!”

Yes, everybody. The Mets’ starting pitcher was too much the competitor to keep his left arm from danger. The Mets relief pitchers weren’t going to stand idly by from their safe haven in the right field bullpen, either. Tug McGraw figured that by the time he and his colleagues joined the fray, the fray would be dying down. No such luck. Tug grabbed Rose; the Reds third base coach, Alex Grammas, grabbed Harrelson; Ray Sadecki pitched in to quell the rabid Rose. “But finally,” McGraw recounted in Screwball, “we ripped them apart and the hassle seemed over.”

But it wasn’t, because the Met relievers weren’t the only recent arrivals at the scrap. The Reds pen men showed up, and one had a taste for…well, something.

Murphy: “And now, Buzzy Capra is in a fight. Out in center field, another fight breaks out.”

McGraw: “Pedro Borbon came tearing in and broadsided Buzz Capra with a shot out of left field that you wouldn’t believe.”

Mind you, this is Tug McGraw who’d just spent six weeks telling everybody who’d listen that You Gotta Believe. Yet it was pretty unbelievable. Borbon went after Capra, so Duffy Dyer went after Borbon and “cold-cocked” him by McGraw’s account, “then everybody started to hassle all over again.”

As if the scene needed a coda, it was provided by Borbon, who grabbed what he thought was his Reds cap and placed it on his head when all the hassling was losing its zip. Alas, Borbon picked up somebody’s Mets cap, and when he realized he was sporting the gear of the enemy, “he went into a real rage,” according to Tug, stuffing the cap “in his mouth, with his eyes all like fire, and started to tear it apart with his teeth” before flinging it to the ground and stomping off the field.

That would have been that, a pugilistic interlude (or two) to liven up a seven-run rout, except one more corner had yet to be heard from. There were 53,967 on hand at Shea, and as proud as they were of Harrelson for standing up for himself — and, by proxy, for them — a minority of the spectators didn’t think Charlie Hustle had quite gotten what was coming to him. So they were going to take care of that themselves.

When Rose took his position for the bottom of the fifth, he learned left field had been rezoned for sanitation disposal by popular referendum. Garbage came flying out of the stands, all meant for him. Rose liked to cast himself as a tough guy, but taking on the malcontents in a sellout crowd was far above his pay grade. The fruit and paper cups didn’t bother him, he said later, but glass receptacles were another matter:

“They just missed me with a bottle of J&B.”

When the critical mass of debris ramped from nuisance to danger, Sparky Anderson scotched the idea of the Reds just standing there and taking it. He pulled his players from the field for their own safety. National League president Chub Feeney and the umpiring crew could hardly blame him and were forced to confront the Mets with a very unpleasant fact: get this barrage stopped or forfeit this game.

It took a diplomatic mission more suited to solving the crisis enveloping the Middle East — Yogi Berra, Willie Mays, Seaver, Jones and Staub — to head to left field and negotiate some sense into the slice of the crowd that wanted the grass to run red with the blood of Rose. Cut it out, they urged the cranks, or our 9-2 lead becomes a 9-0 loss.

They cut it out and the game proceeded without interruption for the final four innings. Amazingly, no one was ejected. Borbon even pitched the eighth and ninth (in his Reds cap). Koosman just kept on keeping on despite hanging around for the donnybrook. When he retired Phil Gagliano to end the most memorable Columbus Day in Shea Stadium history, the Mets discovered themselves 9-2 winners in Game Three and 2-1 leaders in the series overall.

With one more win, they’d sail into the World Series. But the waters grew choppy on Tuesday.

***

What happened next?

You’ll find out when you read The Happiest Recap (First Base: 1962-1973).

Print edition available here.

Kindle version available here.

Personally inscribed copy available here.

Pick up The Happiest Recap and get the whole Amazin’ story of the Mets’ most unbelievable stretch drive ever…and everything else.

by Greg Prince on 8 October 2013 11:30 am Just when I think one of the funnest days of non-Mets baseball ever couldn’t get any more funner, I nod off in the eighth inning of the last reel of this rollicking quadruple-feature, the overly familiar Atlanta Braves leading the Los Angeles Dodgers by a run. I open my eyes maybe fifteen minutes later and the Los Angeles Dodgers are jumping all over one another, and probably not with Brian McCann’s approval. Hours later, by morning’s light, I tell Stephanie how the Dodgers won and how the Braves lost.

Without missing a beat, she lilts, “See ya, Braves!”

If that’s not the funnest way to cap off a daylong postseason festival, I don’t know what is. But I’ll check with McCann and wait for his ruling.

As recently as Saturday, I was drifting unmoored from the Mets, even the 2013 Mets, with whom, I assure you, I was quite done. Yet early Saturday I sat myself down on my couch, looked at the clock, and thought, “1:10 or 7:10?” But there was to be no :10 on Saturday. No Mets. No setting my ballological clock by their seventysomething wins and timeless hopes. Their season was over nearly a week, yet my insides hadn’t come to grips with it.

Now they seem a million miles away in both directions. The 2013 Mets belong permanently to the past, never to pop up with two out and a runner on first again. The 2014 Mets are nothing but unprovable theory until further notice, and I have a hunch the notices are a ways off. If it’s October, it’s not about the Mets.

Well, it’s always a little about the Mets. I wouldn’t find the Braves falling to earth with such a plodding thud so enjoyable if I didn’t retain some good, healthy Cublike enmity for them from when we were serious rivals. I’ve always thought we sucked the life out of them heading into the 1999 World Series by pushing them to something approaching the limit in that year’s NLCS (though the Mets never did receive royalty checks from the eventual world champions). I now believe the Braves have never, ever recovered from mustering all the strength it took to draw ball four from Kenny Rogers. They used to loom. They loomed in 2000 for our dreaded/anticipated playoff rematch until we got word at Shea, in advance of Game Three versus the Giants, that they’d been swept by St. Louis. A mocking Tomahawk chop ‘n’ chant went up.

How cheeky of us!

At some point Monday, while feasting intermittently on the four-game smorgasbord MLB laid out before me, I decided there was to be no mocking of any current playoff participant. They were all worthy competitors, none blessedly was the Yankees and each was where I’d very much like my team to be again before a mall stands on the site of Shea Stadium. That thought, however, occurred to me before Juan Uribe beat the Braves with an eighth-inning home run. If you can’t mock the Braves going down in their first playoff series of the year in the seventh consecutive year in which the Braves have been in the playoffs, then you’re just not extracting all the joy — Sheadenfreudic or otherwise — there is to watching baseball in this unfortunately Metless month.

I turned on my office TV a little after the start of the A’s-Tigers game, the third in the division series in which I had the least emotional capital invested. My relative lack of interest was appropriate, since the MLB Network telecast mysteriously came to me in Spanish. I checked my Panasonic and Optimum settings; they said I was loco and everything was as it was supposed to be. Nevertheless, the audio stayed in Spanish for innings on end. I shrugged and went back to my computer, now and again perking up at mentions of “Moneyball”; “Jim Leyland” and “Home Run Derby”. It’s easier than I would suspect to half-follow a baseball game in a second language. Eventually, I figured out how to bring back the English (I actually had to set my cable to “Español”) which was both too bad, because it exposed me to the inane American Matt Vasgersian, and great, because I could hear loud and clear the well-mic’d Grant Balfour and Victor Martinez inform each other of their respective shortcomings.

It was the long-awaited sequel to Bert Campaneris and Lerrin LaGrow, except with the pitcher and hitter on different sides and hostilities limited to verbiage. No bats or punches were thrown; only glares went awry. Balfour is apparently a piece of work and Martinez plays for a team that has suddenly forgotten how fearsome it can be. The A’s came out ahead in the end, which was fine with me, though I feel bad I can never conjure any genuine autumnal passion for the grand old Tigers, helmed by grand old Jim Leyland, representing a grand old city that could use a boost and is owed one after doing the lord’s work so effectively for two consecutive Octobers. Conversely, if it’s not October 1973, I tend to have a default setting that supports the Athletics, whoever happens to be on them in a given year. I’ve looked in on and listened in to three A’s playoff games in a row and probably still can’t identify half the roster. My problem, not Oakland’s.

By the time matters were settled, 6-3, at Comerica Park, Michael Wacha was deep into perfect-gaming the Pirates in Pittsburgh, which was both too bad for those of us wishing the Bucs all the best after two decades of them experiencing mostly the worst, and pretty darn impressive in that Michael Wacha has less big league experience than Zack Wheeler. But Wacha’s flirted with a no-hitter before, so maybe it wasn’t surprising that this rookie was completely suppressing an opponent in a do-or-die showcase. Wacha didn’t get the perfecto or the no-no, but he and his Cardinal comrades stayed alive, which is swell if you love Game Five drama in a short series, yet is too bad if you’d like the Cardinals to fly south for the winter. Unlike the Braves, they have a penchant for overstaying their welcome most Octobers.

Natch the one Cardinal I can’t root against is Carlos Beltran. The most I can ask of him is not to break too many Pirate hearts the next time he revises the postseason record book (I’ll bet “postseason” didn’t exist as a going phrase when Babe Ruth was belting 15 World Series home runs but doing absolutely nothing in the then-nonexistent preceding playoff rounds). Can’t not cheer for the greatest center fielder we ever had, however. Ideally, I thought early in the Pirate-Cardinal series, Carlos changes uniforms and joins Marlon Byrd on the Bucs. Then I decided that was only a temporary solution. Let us instead have Carlos, Marlon and 23 other really good, really likable players be Mets and cut out the middlemen.

But this isn’t about the Mets, remember?

Wacha’s 2-1 gem, with supporting jewelry provided by Charlie Morton, Pedro Alvarez and, most tellingly, Matt Holliday, took only 2:36 to craft, which allowed the baseball-gluttonous among us plenty of space to fill our bellies with the Rays and the Red Sox. Those guys required the same nine innings they used at PNC Park, yet somehow needed 4:19 to bring their affairs to resolution. If you were rooting for the Red Sox, it went on far too long. If you were rooting for the Rays as I am — USF’s surprise victory over Cincinnati the other night must have stirred my long-dormant inner Tampan — it went exactly as long as necessary, until Jose Lobaton could end it with a home run.

During the TBS telecast from Tropicana Field, the announcers kept insisting that due up in the bottom of the ninth were Ben Zobrist, Evan Longoria and the pitcher’s spot…that’s right, the pitcher’s spot, because so many moves were made and the Rays’ DH had come out and…oh, wait, Joe Maddon double-switched Lobaton into the game. That’s how obscure Jose Lobaton, imminent postseason hero, was before his swing for history. He had replaced Jose Molina a half-inning earlier and it wasn’t fully comprehended where he was batting.

Well, that’s been taken care of. Now Lobaton is up there with other catchers whose low profiles were irrevocably raised on their final swings in a given October game. Like Francisco Cabrera in 1992. Like Todd Pratt in 1999. Sort of like J.C. Martin in 1969, though Martin bunted to win Game Four of the World Series and reached first via clever baserunning. Gary Carter (for us) and Johnny Bench (against us) also had hits that ended tense postseason matches, but those fellas were fairly recognizable to the public at large already.

The Rays’ 5-4 victory ensured at least one more game in their ALDS, which — unless you’re going to be an actual Sox fan about it — is preferable to a sweep. Sweeps are boring if your team isn’t doing the sweeping. Double-elimination games, where somebody will be forced to go home, are the most enticing propositions for the unaligned. Thanks to Wacha, we knew we’d be getting that in St. Louis on Wednesday. Thanks in great part to Freddy Garcia, whom I’ve never forgiven for prickishly walking across the outfield while R.A. Dickey was preparing to pitch to Brett Gardner on July 3, 2011, it appeared we’d get a Game Five at Turner Field, too.