The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 3 January 2011 8:52 pm The Mets have signed two low-risk, low-budget, low-profile pitchers on whom only the truly prescient were concentrating highly prior to the announcement of their unforeseen acquisitions. One is former Rockie Taylor Buchholz, who not long ago underwent Tommy John surgery. The other is former Brewer Chris Capuano, who also not long ago underwent Tommy John surgery.

If either of them pitches like Tommy John, that would be great.

At the moment, I’m most interested in Chris Capuano, not because he was an All-Star in 2006 and hasn’t done a ton since (ahem), but because he comes to us in the same offseason as Boof Bonser. When the Mets picked up Boof Bonser, Stephanie asked me if the Mets were now placing an extraordinary emphasis on alliteration.

I suspect they are. Boof Bonser…Chris Capuano…can Bill Bonham be far behind?

Let us zealously zip to UMDB and quickly compose the All-Alliteration Amazins:

C – Chris Cannizzaro

1B – Tony Tarasco

2B – Tim Teufel

SS – Luis Lopez

3B – Bob Bailor

LF – Melvin Mora

CF – Bruce Boisclair

RF – Shane Spencer

P – Rick Reed

Billy Baldwin is primed to pinch-hit, though Chris Carter is more likely to get the call. Wally Whitehurst warms up alongside Brian Bohanon. One is throwing to Duffy Dyer, the other to Greg Goossen. Scott Strickland stands ready to get the save, but pitching coach Red Ruffing is telling him to hold his horses. There are a couple of Mike Marshalls rarin’ to go as well. (Blaine Beatty’s buried in AAA ball; Bobby Bonilla, benched, sits, stews and seethes.)

Amid all this avid activity, Ryota Igarashi was designated for assignment. Igarashi was non-alliterative, but mostly he was non-effective.

Cap tip to Fred Solomon, Ed Leyro and John Sharples for helping to expand the roster.

by Greg Prince on 2 January 2011 8:10 am The Florida Marlins remain no help whatsoever. By not having announced a start time for their Opening Day hosting of the New York Mets at Name Subject To Change Stadium, they did not allow us to calculate precisely when the Baseball Equinox would be upon us. That’s something we look forward to figuring out every winter, yet the Marlins’ perpetual languor robbed us of that small pleasure, much as their latent, late-September competitiveness robbed us of larger pleasures in advance of previous winters. However, because we do know the first game of 2011 will be April 1 — and because the final game of 2010 definitely took place on October 3 — we can say with authority that even though we don’t know when it occurred exactly, we have indeed drifted past the Baseball Equinox, that space on the calendar when we are closer to next season than last season. The blessed event happened sometime yesterday afternoon.

Tangibly speaking, then, Happy New Year.

Of course we’ve been alternately hurtling and schlepping toward the 2011 campaign’s gravitational pull since the morning of October 4, at whichever instant word seeped that the unfortunately linked tenures of Omar Minaya and Jerry Manuel belonged completely in the past tense. From there, everything became about looking ahead. Who’ll be the next general manager? Who will he choose as manager? Those overarching questions have long been answered — and, I might add, with more definitiveness than the Marlins have offered regarding the moment Josh Johnson next peers in toward the general direction of Jose Reyes’s strike zone.

Far less certain is what we can expect from the first team Sandy Alderson organizes and Terry Collins helms. Seems we’re skipping the part that includes enticing new acquisitions, which is where the hurtling slows into schlepping and I have to rub two sticks together to maintain a spark of anything more than perfunctory excitement over the emergence of the upcoming season. Yes, Alderson’s the man with a plan; and the plan, in its broadest, faintest strokes, is implicitly contingent on decrappifying the 40-man roster of its most onerous commitments; and perhaps as soon as the recording of the final out of September 28 — Closing Day 2011 — we will be hurtling in earnest toward quantifiably brighter years than the last couple we’ve lived through.

This year (like all years before they begin) is an unknown quantity, though relying on the same basic 79-83 bunch to exceed .500 seems a surefire prescription for disappointment. On January 2, disappointing baseball beats none at all, but once the euphoria attached to Opening Day on April 1 and the Home Opener on April 8 dissipates, all we can do is watch and see. We’ll watch and see if a full year of a healed Carlos Beltran compensates for the several months we’ll likely be missing Johan Santana; if Jason Bay’s clear head makes up for a bullpen quietly cleared of dependable lefthanders; if a developing Josh Thole generates more impact than a lingering Luis Castillo depletes energy; if there’s anything at all to be found within a returning Daniel Murphy or an arriving Chin-lung Hu.

St. Lucie beckons soon enough. Not that Spring Training will tell us anything provable, but at least it will distract us for a few weeks. After that, there’s the actual season, when we stand an excellent chance of being pleasantly surprised. Or dourly dismayed. Or something in between.

Which sounds not altogether unlike 2010, but we don’t know that yet. We don’t know anything at all about that which won’t do us the courtesy of transpiring before it’s damn well ready to get rolling. Perhaps the new GM really does know more about our Met future than we can possibly grasp, and if that doesn’t make 2011 a certifiably happier year in the standings, I suppose it could signal 2012 as truly worthy of our salivation. Still, I don’t want to write off the year that just got here just so we can move on to the next. Thirty-two hours into 2011 and eighty-nine days from its first pitch, it’s immensely unsatisfying to think in those terms.

I used to get psyched about the approach of a new season. Lately I just brace for it. Maybe that will change between now and April 1. Maybe the Marlins will tell us what time we need to tune in before then. Once we are so informed, I’m going to watch and see.

That much I do know.

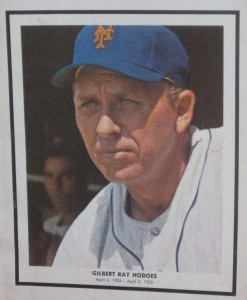

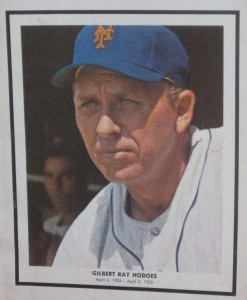

by Greg Prince on 31 December 2010 11:34 am The phrase “48th birthday” carries a Metsian resonance that resounds beyond the usual suspects. Randy Tate, Randy Myers, Aaron Heilman (I suppose)…all valid identifiers for we who are tenured fans/MBTN bookmarkers, yet when I found myself earlier this week noticing the nearness of my 48th birthday, one name unattached to uniform No. 48 planted itself in my mind:

Gil Hodges.

I could do math very well as a kid, so when I received my 1972 yearbook in the mail and opened to the first inside page, it was an easy calculation. Printed under the suitable-for-framing photo of our late manager were his birthdate — April 4, 1924 — and his astoundingly untimely death date — April 2, 1972. That was 48 years minus two days, and that would become the last line of every biographical summation of the man’s life. Hodges was felled by a heart attack two days shy of his 48th birthday.

The only manager I could imagine. So close to 48. Not that there was anything magical about 48 except that it would have been a blessing to all concerned had Hodges reached it. The Mets would have been a better place if Gil had made it to 48, then 49, then 50 and so on. The world at large probably would have benefited, too. In Gil Hodges’s not quite 48 years, he fought for his country at Okinawa, caught the last out of the World Series for Brooklyn and worked miracles in Queens. Gil Hodges accomplished a great deal in a short time. One can only speculate what a longer life might have yielded.

Everything I’ve ever read about Gil Hodges, from his Indiana coal country upbringing to the way his days ended with a literal thud on a Florida golf course, dwells on how strong he was. Physically strong. Constitutionally strong. Strong as a Marine in World War II. Strong as the powerful corner infielder who anchored Ebbets Field’s epoch of glory. Strong as the manager who raised expectations for each individual New York Met until they were strong enough to lift themselves, as a unit, to the pinnacle of their sport.

Strength Gil Hodges did not lack. Yet he didn’t make it to a 48th birthday. An inveterate smoker, he was strong enough to survive one heart attack, at age 44, but not a second. This is Gil Hodges we’re talking about, the Mets’ one-man Mount Rushmore, the first manager I ever rooted under, the only manager I could, in my early years of fandom, ever imagine commanding my team. I’m sure I didn’t know Gil Hodges’s age until it was announced in the past tense. I’ve been amazed ever since I bothered to do the arithmetic that he was a mere 45 when he steered the 1969 Mets to their destiny. When I was a kid, I had no concept of 45. It sounded old. So did 70. So did 28.

Watch out fellas, there's 120 losses under your feet! From left to right, it's Original Mets Thomas, Hodges, Zimmer and Craig. As of today, I am 48 years old and, quite frankly, I can’t believe I’ve outlived Gil Hodges. I’ve never seen a photo or a film clip of him, certainly not from the time he was a Dodger fixture onward, in which he didn’t seem older than me right now…to say nothing of more substantial. Even in that incongruous image of Gil Hodges leaping loonily into the abyss that was about to become the 1962 Mets — the shot in the Polo Grounds where he’s wearing a road uniform and a mitt while brandishing a bat alongside several hammy teammates — he instinctively maintains his dignity. Gil Hodges was 38 when that season began. His designation as the starting first baseman for those inaugural Mets is often invoked as a symptom of the deleterious franchise-building philosophy that hamstrung our collective baby steps. Sure, he was beloved locally. Sure, he was winding down a stellar playing career. But Gil Hodges was 38. He was ancient.

I don’t remember feeling ancient when I was 38. I don’t feel ancient at my newly minted age of 48, certain undeniable physical trends notwithstanding. Maturity was held to a different standard in 1962, the year I was born. It was hanging tough in 1972, the year Gil Hodges died, two days before he could make it to 48.

I may be older than Gil Hodges ever was, but I doubt my maturity will ever be in the same league.

by Greg Prince on 28 December 2010 9:23 pm John Olerud’s name appears on the 2011 Baseball Hall of Fame ballot. It should be the other way around. The Baseball Hall of Fame should appear on the 2011 John Olerud ballot.

THE 2011 JOHN OLERUD BALLOT

Rules: Please vote for the honors, offices and/or institutions to which John Olerud should consider lending his considerable personage. Mr. Olerud will decide at a later date if he will grace with his presence any of those named on at least 75% of all ballots.

__ NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME

Located in Cooperstown, New York … may not be convenient for John Olerud unless it is relocated to Pacific Northwest … purports to offer “immortality” to outstanding baseball players … to discerning Mets fans, immortality is the second-highest level a baseball player can achieve; John Olerud is the highest … could use infusion of grace considering it is weighed down with surfeit of poor character (e.g. Walter O’Malley, Bowie Kuhn) … John Olerud may not wish to associate himself with this supposedly august body unless peers in legendary first base play (Gil Hodges, Keith Hernandez) are inducted alongside him … membership currently limited to individuals … ultimate team man John Olerud would no doubt prefer 1999 Mets — a.k.a. The Ultimate Team — be inducted as a unit.

__ AMERICAN IDOL

One of the highest rated television shows of the past decade … John Olerud too often underrated when, in fact, he can’t be rated highly enough … airs on Fox … John Olerud’s sensibilities better suited to low-key networks like C-Span3 … an all-time high 624 million votes cast during show’s eighth season … in his second season as a Met, John Olerud set a new club mark by batting .354 … average Americans call in to select the new American Idol … John Olerud already an idol to the average Mets fan.

__ MISS UNIVERSE

Worldwide beauty pageant for young ladies … no creature on earth as beautiful as John Olerud … a truly international event … John Olerud’s stardom shone in both Canada and the United States … produced by the Trump Organization … John Olerud wore a helmet in the field for protection after experiencing a brain aneurysm; what’s the excuse for that thing Donald Trump keeps on his head?

__ MAYOR OF NEW YORK CITY

Responsible for delivery of services to more than 8 million New Yorkers … John Olerud always delivered for New Yorkers … must make certain snow is removed after severe winter storms … John Olerud cleared the bases with regularity — primary, secondary and tertiary roadways would be a breeze … has to deal with an array of high-powered rivals … John Olerud has dealt effectively with Curt Schilling and Greg Maddux … needs to unite diverse constituencies that aren’t always willing to understand one another’s differences … even brief, unfortunate tenure as a Yankee could not diminish the luster of John Olerud in the eyes of Mets fans.

__ ROCK ‘N’ ROLL HALL OF FAME

Recognizes transcendent contributions to contemporary popular music … hard to think of anybody who had bigger and better hits than John Olerud … previously inducted musicians include those who were considered extraordinary on bass … John Olerud was extraordinary at getting on base … as induction ceremonies wind down, the stars jam together in a one-night supergroup … John Olerud played with Robin Ventura, Rey Ordoñez and Edgardo Alfonzo in the Best Infield Ever for just one year … mostly considers artists from the 1950s onward … John Olerud would have been most at home with the music of the 1940s, as he was all about that sweet swing.

__ POPE

Spiritual leader of Catholics everywhere … John Olerud’s goodness is too far-ranging to be confined to a single faith … infallibility a key aspect of papacy … did John Olerud ever look like he didn’t know what he was doing? … selected by College of Cardinals … John Olerud jumped to the majors directly from college — and registered an OPS of 1.042 versus the Cardinals in his first season as a Met … election signaled by white smoke … John Olerud wouldn’t knowingly subject a crowd to second-hand smoke.

by Greg Prince on 28 December 2010 9:00 pm In 2009, Flashback Friday commemorated the milestone anniversaries of previous Mets seasons ending in 9: 1969, 1979, 1989 and 1999 with a series subtitled I Saw The Decade End. Here, for handy reference (a year after the fact, because I sort of forgot to give it its “Best of FAFIF” cataloguing treatment last December), is a guide to the epic Mets days of ’69 and ’99…as well as the lesser Mets days of ’79 and ’89. Remember: you don’t need to make the playoffs to generate a good story. Click on any for whichever trip back in time might intrigue you.

1999

Our Days Got Numbered: Cosmetic changes are all around

Team Building Exercise ’99: The unlikeliest Met, from the vantage point of 1988

Wallworthy: Why some things are bigger than titles

Never Gonna Win Another Game: An eight-game losing streak that feels much longer

Don’t Stop ’Til You Get Enough: The Mets who stayed crunchy, even in milk

The Fab Four: The Best Infield Ever coalesces

Freaks and Geeks: Setting September’s stage

Baseball’s Most Magical Date: October 3 comes to its logical conclusion

Prelude, Playoffs & Postscript: Whacking the Diamondbacks

A Beautiful Ride: Coming up short against the Braves

The Days After: Picking up the pieces

Amazin’ Medley: A musical homage

1989

Showing Some Fight: Darryl takes on Keith, while I take on beverages

Last Summer in Long Beach: Getting around to coming of age

Dykstra & McDowell for Samuel: Potentially advantageous trade goes horribly awry

Intermittently Sweet Music: Frank Viola, not quite the answer

As Mookies Go & Eras End: Exiting the Eighties

1979

When Shea Would Go ‘Boom!’: Fireworks Night explodes in Flushing

Generation Pre-K: Going cheap, going young

The Willie Mays Bridge: Spanning New York’s National League generations

Livin’ It Up (Friday Night): When Mets vs. Yankees was as much conjecture as rock vs. disco

Dock Ellis to Doc Gooden: Counting our lucky All-Stars

Dave Kingman Appreciation Day: Surrendering three homers, gaining one win

¿’79 or ’93: Cuál es Mas Mal?: Which wretched season is more bad?

1969

Before & After: If it occurred before I met the Mets, it hardly counts

Living in the Moments: How does a miracle lose its currency?

Donn of a New Era: Clendenon makes an impact

Duffy Deserves His Ring: The ultimate backup catcher

Born Again: Before there was Jimmy Qualls, there was Don Young

It’s A Family Affair: Uniquely Met immortals

Rites of Passage: Bar Mitzvah in the morning, Old Timers at night

You Never Forget Your First: Why 1969 still resonates

Across The Decades

Don’t Pitch to Kevin Young: A fan born in 1969 revels in 1999

Rickey and Jesse Would Always Know How to Survive: A Met rookie from 1979 crosses paths with a Met star from 1999

Euphoria and the Infinite Sadness: The long and winding road from 1969 to 1979

by Greg Prince on 25 December 2010 1:37 pm What? You didn’t get a ballpark for Christmas? Fear not, for I have regifted one of the presents baseball has given me — a quick trip to the 34 ballparks I’ve visited, passed on to you one paragraph at a time, from least to most beloved. Should you care to linger longer at a given venue, please click on the ballpark’s name and take the full tour. No ticket (or sleigh) required.

34. Olympic Stadium

Its main drawback was it was less like a ballpark than a basement, and not the National League East kind (the Expos were doing pretty well in 1987). Or maybe it was more like a warehouse, but I don’t mean in the fun Camden Yards sense. More like those refrigerated warehouses I’d visit when I was covering beverages full-time. It was cold, there were forklifts and there was plenty of beer. Beer’s not a drawback at the ballgame, but, as you probably saw if you watched Mets @ Expos games on TV, it never looked finished.

33. Jack Murphy Stadium

Pleasant beats unpleasant every time. But pleasant’s not the same thing as big league, and there was something about seeing a Padres game in their original home that felt less than major. It wasn’t bad — pleasant can’t be bad — but it didn’t fill me with anything approaching awe.

32. Royals Stadium

This was a multipurpose stadium in soul if not practicality. The artificial turf (replaced by grass in 1995) didn’t help. The schlep up to the top rows of the upper deck — I’d bought the seats in June, but the Royals were very popular — was frustrating, too. The Royals monarchical scoreboard was unique, but the fountain’s charms wore off quickly. Middle of the second: fountains spew water. Top of the third: fountains spew water. By the fourth, we got it.

31. Veterans Stadum

Veterans Stadium was as unpretentious as a ballpark could get, which was appropriate because what could it possibly have pretenses toward? It was hard. It was plastic. It was numbingly round. You didn’t rush to embrace it and you wouldn’t dare hug it. If you tried, I suspect you’d come home with bruises on the inside of both arms, and maybe a jab between your shoulder blades. But it got the job done, no matter how unpretty the job. Your job, as the fan, was to watch the game. You watched the game at the Vet. There was nothing else to look at.

30. RFK Stadium

For something that was so somnambulant for so long, RFK served its temporary purpose remarkably well. Don’t get me wrong. The place was a dump. I don’t mean in that Shea “it’s a dump, but it’s our dump” lovable way, either. I wouldn’t have been surprised if it was used for a tire fire when it wasn’t being used for baseball. It was dark, it was cramped, it was MacArthur Park come to life: someone left this cake out in the rain, the sweet green icing was long melted and it showed. But it came to life in 2005 when the Expos became the Nationals, and you’d be surprised how beautiful a “dump” can be when it’s got baseball and baseball fans.

29. Renovated Yankee Stadium

I would have liked to have seen the real Yankee Stadium, the one that existed in full for a half-century. I only saw that one on Channel 11, and then only if the Mets weren’t playing (and even then in short doses and with distaste — distaste for Jerry Kenney, Rich McKinney and Celerino Sanchez…I was capable of hating Yankee third basemen well before Alex Rodriguez was born). That place was legitimately historic. The place I got to visit I never bought as the same one. I’d looked at too many pictures of the original to think the renovated version was anything but a knockoff. Granted, the ’76 iteration hosted its own history over 33 seasons, but I never had the sense I was in the house that anyone but John Lindsay built. The Yankees may not have moved to the Meadowlands, but their refashioned building, escalator banks and all, reminded me more of Giants Stadium (also class of ’76) than a pure idyllic ballpark. For anyone who wasn’t buying in to the myth in advance, it wasn’t an alluring proposition. It combined 1920s efficiency with 1970s charm.

28. Minute Maid Park

It’s in a part of Houston that, at least back then, contained nothing else with a pulse. Maybe a bar or two, but it felt plopped in as if to develop or redevelop downtown. I liked the idea of a converted train station, but it didn’t give off a ballpark feel from the outside. Nobody who worked there seemed particularly friendly (come to think of it, there were a lot of unfriendly people who worked for Mr. McLane). It was kitschy without being fun. Maybe it was an improvement on the Astrodome, which I never visited, but it was the first retro park I saw that I really didn’t much enjoy.

27. New Comiskey Park

It was too high. That’s what we’d heard going in, and we weren’t disavowed of the notion once we left. Capacity was in the low 40,000s, but the upper deck negated any notion of intimacy. Original Comiskey, by dint of posts, kept the upper deck within striking distance of the field of play. Cantilevering (one of those words I learned when I was having my ballpark-consciousness raised in the early ’90s) removed such obstructions, but there was now the chance your view of the game would be blocked by a bird. The last row of the last tier the old park, I’d read, was closer to home plate than the first row of the last tier of the new park. I believe it. No kidding, it was high and steep up there. I was a veteran of the Shea upper deck, but that was a dash up the steps next to New Comiskey. Bring water. Bring a guide. Bring oxygen. Maybe don’t bring your wife on a 90-degree day, particularly when she is averse to glaring sun and has left her Mets cap in New York. (One adjustable White Sox cap never to be worn again: $15.)

26. Network Associates Coliseum

I’ve never encountered less grandeur en route to a major league stadium. That hoary quote from Gertrude Stein was obviously written with the home of the Oakland A’s in mind. There is no there there. It didn’t feel like there would be when Stephanie and I stepped off a BART train from San Francisco nine years ago and looked for something approximating a ballpark. Normally I’d just follow the crowd, but for a Thursday afternoon game in Oakland, there was no crowd. There was barely any “there”. There was, however, a bridge. There were some panhandlers. There was then a loading dock. Then there was an enormous pile of concrete. That’s the Coliseum. Welcome to A’s baseball. It’s going on in there somewhere. Perhaps it was because the outside was so uninspiring that once we were inside “the Net” (or as our local friends called it, “the Ass”), it actually surpassed our expectations. We expected a quarry, I suppose. We got a pretty decent setting for baseball, all things considered.

25. Old Busch Stadium

The tour ended on the turf. It was my first time on a major league field. Even though it was carpet, it was thrilling. We stood in foul territory on the first base side and were told to not step over the line lest we incur the wrath of the grounds crew. It was just turf, but who wanted to make trouble? As the guide wound down his remarks, my eye wandered to right field. On October 3, 1985, Gary Carter hit a fly ball over there with one man on and two men out in the ninth inning, the Mets down a run. When he connected, I was convinced it was going out, that the Mets were going to pull ahead of the Cardinals in the game and tie them in the standings and that everything would be great. Instead, the ball was routine and the outcome — 9-unassisted, caught by Andy Van Slyke — was predictable. Still, for a moment, I reveled in standing feet away from bittersweet Met history. We won those first two games in St. Louis that first week of October. They could call us pond scum, they could spill their beer on Lenny, but we went to the ninth inning of the third game with a genuine chance. Keith had singled for his fifth hit of the night, and Gary, on fire for a month, was up against Jeff Lahti. That was 1985. This was 1995. Baseball had been gone since the previous August. Now it was so close, I could taste its lingering heartache. Three seasons after having had quite enough of it, I would exit Busch Stadium the second time not particularly wanting to leave.

24. SkyDome

Our $50 pair of seats was in SkyDome’s upper deck, or “SkyDeck,” which sounds so much cooler than upper deck. Very futuristic, very tomorrow. Thing is while we climbed to said Deck, I wasn’t being whisked along by a PeopleMover or a GlideWalk or something else that smushed TwoWords together in a futuristic construction. There were just stairs. Outside the doors to the seating bowl, there was just a hallway. It was no more modern out there than Madison Square Garden. With a threat of rain, the retractable roof was closed. We were inside an arena, basically. A vast, carpeted baseball arena adorned by the largest JumboTron in North America. Where’s the future in that?

23. Anaheim Stadium

The comfort of the Big A came easy. And there was one overriding reason for it: I could have sworn I had been there before. Why? Because it was Shea! Anaheim Stadium was a thinly veiled, West Coast version of Shea Stadium. It couldn’t have been more like Shea had it had an apple and an airport over the outfield fence. This was Anaheim Stadium before gentrification. You see it on TV today and you see a Disneyfied ballpark-style attraction now known as Angel Stadium. But back then, it was Shea West. It was enormous and it could be used for a multitude of purposes. Sound like any stadium you once knew? That alone may not be specific enough to evoke Flushing in Anaheim, but it definitely had the feel. Anaheim had grass, like Shea. Anaheim was from the ’60s, like Shea. Anaheim had that sense of being somewhere not altogether where you imagined it might be. Shea was New York, but it was, in terms of access to anything that wasn’t inside the stadium itself, in the middle of nowhere. Anaheim wasn’t L.A. — and L.A. definitely isn’t “of Anaheim” — but you shrugged if you were from back east and figured you were close enough. Anaheim Stadium was the closest thing to Shea Stadium I ever experienced without a 7 train. I’m not surprised that I liked it as much as I did, and perhaps it’s telling that when stripped of all personal and Met association, I didn’t find much else distinctive about pre-renovation Anaheim Stadium.

22. Bank One Ballpark

There was a tension between the modernism necessary to execute a retractable-roofed stadium in the middle of a burgeoning downtown and the desire to at least partially ride the retro wave that had been in ballpark vogue since Camden Yards opened six years prior (thus, that pretentious dirt path). It was sort of like the desire to have a unique Arizona feel to the scene — accented by those garish teal and purple uniforms on which Showalter signed off — while accepting megabucks to plaster the rootless Bank One logo all over the place. It continued indoors, which featured, among many other attractions/distractions, a Hall of Fame exhibit, on loan from Cooperstown. The Diamondbacks had existed for little more than a year to this point, but they were trying to steep themselves in baseball history, just as the sculptures outside tried to give fans a cue as to what awaited them inside. That type of touch could have been taken as truly tradition-friendly or it could have been interpreted as a overly marketing-driven. It was probably somewhere in between.

21. Great American Ball Park

Great American wasn’t a great park, but it was a good time. There was even something to the corporate name on the door. There was a touch of Twain to that view of the mighty Ohio and the country that lay beyond it. If you can evoke Tom Sawyer and Tom Seaver in the same evening, that’s gotta be pretty Great.

20. Nationals Park

The Nats skipped the bricks and the overwrought homages to a mythic baseball past. The clean, well-lighted, modern approach was refreshing even if red brick can serve as an effective Pavlovian cue to get fields-of-dreamy about one’s surroundings. You don’t always, however, need to be enveloped by a manufactured past. That said, there was something about Nationals Park that made it feel — and this isn’t intended to come out as derisive as it will — like a very nice and very large Grapefruit League park. It wasn’t sterile as much as not yet defined, not yet lived in.

19. New Yankee Stadium

Once the game started, the consensus was this place was OK for ballgame watching, but it didn’t set any new standard for excellence. If you peered hard enough, beyond facades and pictures of championship teams in the concourses (and they’ve had a few) and the massive video board above the left field bleachers, there was something Natsy about Yankee Stadium — it wasn’t a whole lot different from Nationals Park. I had that sense at Citi Field in April and now I got it here. You could sell a lot of stuff and you could put up a lot of pictures, but when you got right down to it, there was a throbbing adequacy to Yankee Stadium. It was new, it was clean, it had ATMs…after a fashion, no matter how much pride and pinstripes one franchise can claim, all these new places — Nationals Park in 2008, the two New York parks in 2009 — seem to have their core come out of a kit.

18. Miller Park

It was a super fun evening in a really well-conceived facility. The only thing that holds it back from greatness is it’s an indoor facility. We did a 360 walkaround before the game and it drained some of the enthusiasm I’d gathered outside. The curse of the auditorium. Watching the game while it was still light out felt all right, but once it was a nighttime sky, I felt claustrophobic again. I’d wanted a ballpark trip to get away from feeling enclosed. Miller Park needed to breathe. It needed to step outside and make everything feel a little less cold and industrial. It should have been a fantastic showplace for baseball. It almost was. Stupid retractable roof.

17. The Ballpark in Arlington

It’s the original Ye Olde Ballpark attraction planted in a parking lot off a highway. Even if the highway is the Nolan Ryan Expressway, it feels cut off from the kind of baseball tradition it aches to evoke. You can’t approach TBIA and not be conscious how far you really are from anything having to do with it. The good news is once you get close and then inside it, your ballpark snobbery fades because even if it is a bit of a baseball theme park, it happens to be a very good baseball theme park. And though those of us who value integrated neighborhood aesthetics and all that might be put off by a ballpark whose immediate community is a vast parking lot, it’s Arlington, Texas. Where else are they gonna put the darn thing?

16. Citi Field

Citi Field should have gotten everything right. It didn’t come close. But it didn’t screw up completely. If you’re a Mets fan, you understand that not screwing up completely is sometimes as good as it gets.

15. New Busch Stadium

Busch was beautiful from the outside. I rank it a hair ahead of Citi Field and that’s probably because it did unquestionably better with the aesthetics in my purely subjective opinion. The interior reds and greens are perfect. Busch’s exterior, meanwhile, looks like it belongs where it’s situated. The bricks hum in harmony with nearby buildings. The arches pay homage to that one really big one a few blocks east. There are reminders that we are near a bridge, the Eads, laced into the steelwork. And when you’re inside the park, particularly if you take the tour — as we did, mid-morning — and get the home plate vantage point, the St. Louis skyline makes for a glorious backdrop. All those years watching the Mets play in an enclosed Busch (and Three Rivers and Riverfront) revealed nothing of the environs they were visiting. It was nice to know that baseball teams actually played someplace. The attractiveness quotient was, like the temperature, high enough, but once we actually went to our game (praise be, the mercury plunged to 89 degrees at sunset and there was the slightest of breezes), it was less thrilling than I hoped it would be.

14. Citizens Bank Park

While I didn’t think CBP broke much new ground in 2004, it wears very well in 2010. It has a nice, easy slope to it. Its architecture doesn’t try too hard. It feels not like a drawing board project gone awry in the transition to real life but an actual ballpark, comfortable for its purpose, civilized in its approach. It’s intimate without the claustrophobia. It emits a lighthearted sense of self. The statues and other heritage-minded tributes (Ashburn Alley, Harry the K’s) burst with the kind of pride a fan — even an “enemy” fan — feeds off. I’ve sat in four different areas on my four trips, and they all have something to recommend them. It all looks good, it all sounds good — the PA is crystal clear and the music selection’s superb (though the announcer is overbearing) — it all tastes good and it all feels right.

13. County Stadium

My mother, had she ever made it to County Stadium, would have known what to call it. She would have broken out the Yiddish as she tended to do (American birth and upbringing notwithstanding) and declared it haimish. She usually invoked that word when she wanted to express how down-to-earth something was. Not prust, as in “common,” which was something we were told not to act (spitting, for example, was admonished as prust) but haimish…homey — unpretentious. County Stadium, Milwaukee. It was so comfortable, even the Yiddish language feels retroactively at home there.

12. Dodger Stadium

Damn that O’Malley, getting exactly what he wanted in Los Angeles and making it work to near perfection for decades, even long after he was gone.

11. Jacobs Field

It was the magnet in the middle of our minds from the moment we checked in until we got through our game. After dropping our luggage, we walked over and peeked in. There was no game in progress, but it was right there on the street waiting to be gazed upon. You could see the field and all the touches that made it special, like the toothbrush lights and the massive scoreboard (which seemed bigger in those days before everybody got one). You could enjoy the sandstone exterior, an unwitting antidote to the epidemic of Camden-style bricks almost everybody else building a ballpark was copying from Baltimore. Cleveland had itself an original. The game was Friday night, but I couldn’t wait 24 hours for more Jake. It was just too damn alluring and we were just staying way too close to pretend it wasn’t calling to us.

10. Coors Field

Saberhagen never much impressed me as a Met but seeing him as a Rockie, just eight rows away…wow! That was probably the beer talking. But sobered up and settled in after a fashion, my wowness never dissipated as the night wore on. Coors Field felt as fresh as what SandLot was brewing. It was crisp and open and electric, like no place I’d been for baseball. The house was packed and engaged by its baseball team. Intelligently engaged. Three years in the bigs and these were major league fans. Not only did they cheer their Rockies as three-quarters of their Bombers lay waste to Cubs pitching, but they were savvy enough to scoreboard-watch. The Dodgers had edged ahead of the Rockies in the N.L. West, but they were losing in Cincinnati. When that game went final, a roar went forth that was as majestic as the Rocky Mountains.

9. Turner Field

I developed a theory about Turner Field after spending nine sublime innings in its company. It had to do with the name on the door. Something about Turner Field looked and felt uncommonly perfect for baseball. It transcended what we were already calling “retro”. Turner Field didn’t feel retro. It felt traditional, like if you had to conjure a “ballpark” in your mind, you might come up with how this one looked while you were sitting in it. Ted Turner, I thought. Ted Turner’s in the entertainment business. Ted, I decided, put his best showbiz people on Turner Field. He called in his set designers after the 1996 Olympics were over, before the stadium would be converted for the Braves’ use, and said give me something that allows our patrons to get lost in baseball as they watch our games: not gimmicky, nothing distracting, just appropriate. If that’s the way it happened, then thanks Ted; it worked. And if it didn’t go down that way at all, it’s enough that I believe it.

8. Pac Bell Park

This place was Retro Version 2.0, an upgrade from the generation of trendsetting ballparks that preceded it. Pac Bell was evidence that nothing was static in this fast-moving era, that progress was only a mouse click or a Barry Bonds swing away. Camden Yards had been state-of-the-art just eight years earlier. Now baseball seemed poised to trade in their Camdens for Pac Bells. That’s how it felt up in the last row. As hackneyed an expression as “state-of-the-art” had become by 2001, it fit Pac Bell. Actually, maybe you could make do just by calling it “art”. Wow, what a venue for baseball.

7. Fenway Park

After touring the exterior, we made our way inside Fenway and to our seats in short right. We all had the same reaction: This place is small. “It’s smaller than the field at Shell Creek,” Rich said. Shell Creek Park, his and Joel’s place of employ, was a Town of Hempstead park, home to softball games. My ill-fated attempt to organize a team out of our high school newspaper staff took place at Shell Creek Park. There was nothing big league about Shell Creek Park. But Rich was right. It was smaller than Shell Creek. Felt smaller, at any rate. Definitely no match for Shea Stadium, the only frame of reference any of us had. Size, however, wasn’t everything. Fenway Park didn’t need a parking lot or logical access or an extra 20,000 seats. We were young, but we were wise enough to get why this place was a big deal. Everything we’d seen on television was here in bright green: the Monster; the hand-operated scoreboard; all the bizarre angles. There were the Red Sox and the White Sox, in living color, so much closer than we were used to the teams being at Shea (closer, in proximity, to Shell Creek Park). And there was, in our midst for the first time since 1983, Tom Seaver.

6. Shea Stadium

It meant home. Actually, in its way, it was better than home. You need a literal home, but you also need a place you just want to be…y’know? Home carries certain responsibilities, not all of them desirable, depending on what else is going on in your life. The place where you just want to be is there for you, free and clear of baggage. That was my Shea. I sought it out and it accepted me. Every time I needed to be, I could be there. When it was great, which was usually, I didn’t have to think about it. It was Shea being Shea. When it wasn’t, which was occasionally (and logistically), I could just write it off as, well, there goes Shea being Shea. I didn’t have to make excuses for it. Spend 400-some games with a ballpark, it will eventually explain itself.

5. Wrigley Field

It was a sweep! A Mets doubleheader sweep of the Cubs at Wrigley Field on a Friday afternoon that I took in from the kinds of seats reserved for the Eddie Vedders of the world. The Mets were the real rock stars, however. They were now 1½ in back of the Cubs for the Wild Card. There were still two months to go in the season, but this would be, thanks to expansion, realignment and general Seligism, the last series between the two old rivals. We had to get to the Cubs while the getting was good. The getting was very good this Friday. Wrigley was very great. I didn’t want to leave. Savoring victory, I took out my Chinon 35mm camera (huge by 2010 standards) and took some more pictures. The memories, however, would suffice. I can still see Wrigley filling up; Wrigley jammed; Wrigley filing out; the green, green grass of Wrigley, so close to me…I didn’t want to pull back from it. Who would?

4. PNC Park

PNC Park was the moment a decade of throwback ballpark construction was leading up to. There were breakthroughs before, there was innovation en route, but the culmination of the phenomenon that began in the early 1990s reached its peak with the opening and blossoming of PNC. It must have. I can’t imagine any newer place ever being better.

3. Tiger Stadium

I am not nor have I ever been a Detroit Tigers fan. But count me as a spiritual member of any organization dedicated to Tiger Stadium. I would have hugged her had it occurred to me as feasible. For what it’s worth, I kissed her goodbye on my way out. Literally. Tiger Stadium. Sweet, embraceable you. I guess all we had was a one-night stand, but you still bring a smile to my face and a pang to my heart. It was all I could do to see you once, before it was decided you had to go. I’m sure glad I got there just in time.

2. Camden Yards

Did I mention they got Oriole Park at Camden Yards right? That even with the slightly overdone name — does anybody who isn’t paid to actually call it Oriole Park? — and the implied (or not so subtly explicit) sense of class separation, that it was just the right place to be on that Tuesday afternoon? That the Baltimore skyline, accented by the Bromo Seltzer tower, complemented the Baltimore ballpark as if somebody took everything into account? That there was milling and teeming on the street between the park and the warehouse that was somehow part of the ballpark but was also a city street? Eutaw Street…they incorporated it into the footprint. Co-oped it during game hours, but it was open the rest of the time to pedestrians, just like the team store in the warehouse. There was a team store in the warehouse! Of course there was, why wouldn’t there be, but again, this seemed revolutionary for my pre-Camden mentality. All the interesting food stands and beer stands and Boog’s Barbecue — why had not this been thought of before? Or if it had been thought of, why was it not executed anywhere else? And how about that field? The angles of the outfield wall! And the ads for Coca-Cola and Budweiser that could have been from the first part of the century! And people….people, everywhere. People happy to have snuck away from wherever they were supposed to be on the sunniest Tuesday afternoon in the history of sunny Tuesday afternoons. My seat, in short right, was not bad. Not bad at all, especially in light of demand. Camden Yards was where everybody wanted to be, yet I could be in not the worst seat in the house. Did this house have a worst seat? I looked all over the place: the sea of green seats; the thousand and one perfect touches (the end of each row, for example, incorporated the 1890s Baltimore Orioles logo into its grillwork); and the green grass (not a detail to be taken for granted while the Vet, et al, still stood); and the way you could see the bullpens (they weren’t hidden like I was used to); and this marriage of urban setting and National Pastime… Christ, it’s like they thought of everything.

1. Old Comiskey Park

It reeked of baseball. That’s what Comiskey Park did. Reek does not carry pleasant connotations — “to be pervaded by something unpleasant” is the dictionary definition — but that was the word that came to me 21½ years ago. I meant no offense by it. To the contrary, it was the highest compliment I could pay it. What better to reek of than baseball? What better to sense oozing out of the pores of a building than 80 seasons of national pastime? I knew very little about Comiskey Park when I bought that ticket, but I could feel everything about it once I stepped inside. This place reeked unapologetically of baseball, baseball and more baseball. Baseball had infested this ballpark like termites. The baseball was peeling from its walls. The baseball formed puddles at your feet. You needed a bucket to catch all the baseball dripping from its ceilings. There was no mopping it up, no patching it, no stepping around it. You walked through Comiskey Park, you were immersed in a flood of baseball. Best. Reek. Ever.

by Greg Prince on 24 December 2010 12:57 pm Welcome to the final edition of Flashback Friday: Take Me Out to 34 Ballparks, a celebration, critique and countdown of every major league ballpark one baseball fan has been fortunate enough to visit in a lifetime of going to ballgames.

BALLPARK: Comiskey Park

HOME TEAM: Chicago White Sox

VISITS: 1

VISITED: June 27, 1989

CHRONOLOGY: 6th of 34

RANKING: 1st of 34

A new, state-of-the-art Comiskey Park will soon be taking shape directly across 35th Street from the current Comiskey, the oldest existing major league ballpark. […] The new ballpark will offer all the amenities to fans who come to White Sox games while at the same time retaining some of the look and charm of the old stadium. “Nostalgia” will be a key ingredient as the new 43,000 seat stadium rises immediately to the south of the current facility.

—Chicago White Sox 1989 game program

Now you can tear a building down

But you can’t erase a memory

—Living Colour, “Open Letter To A Landlord”

He called me kid. He called everybody kid. “Kid,” he said, “the NutraSweet party’s tonight. I won’t be able to make it, but you’ll be there, right?”

I nodded. In doing so, I lied. I lied to my publisher. I wasn’t going to any NutraSweet party.

***

The Institute of Food Technologists has a big annual convention every summer. Sounds like guys in lab coats waiting for a girl in a swimsuit to jump out of a chemically enhanced cake, but that’s not quite the scene. They set up shop in a massive convention hall and, as is the case with any trade show, it couldn’t be more numbing. Acre after acre of booths are set up so you can stop by, be told how incredible some new development/product is, take some literature and maybe have a sample.

Samples are everywhere at a trade show, especially one with food and/or beverage implications. The hot item at IFT twenty-one years ago was cheese, or some artificial simulation of cheese. “Would you like to try one?” some pretty booth hostess with a tray would ask. Sure, I’d say. I said it too often. I couldn’t look at artificial cheese by the time my first day at IFT ’89 at Chicago’s enormous McCormick Place was done. Not that looking at artificial cheese was ever a goal of mine in particular.

I wasn’t at this show for cheese. Not my beat. I was there for the beverages, or, more specifically, for the beverage ingredient makers. They were an intrinsic part of what we covered at the beverage magazine I had joined a little more than three months earlier. My job was to cover those booths — grab brochures, talk to executives or PR people and, when you got right down to it, let the magazine’s advertisers know editorial cared about them.

That’s why the NutraSweet party was on my publisher’s mind. NutraSweet was a huge advertiser. They were, at the time, the only company with a patent to produce the aspartame sweetener in the United States. Aspartame was the key ingredient in diet colas. It had revolutionized the category in the 1980s, making for a better-tasting and (according to repeated reputable testing) safe product for calorie-conscious consumers. By 1989, there was no doubt that every soft drink marketer and bottler in America knew how important NutraSweet was to their business. Why they had to advertise in trade magazines, it occurs to me now, isn’t clear, but convincing them it was vital was the genius of men like my publisher, the ultimate trade magazine ad salesman.

His fallibility, however, was believing me when I nodded that I’d be at the NutraSweet party once he told me he wouldn’t be there. Having already attended to NutraSweet’s IFT booth and having scooped up literature and quotes and whatever else I needed in terms of information and face time — and having determined that the NutraSweet party was the kind of gala cocktail soiree from which a single trade magazine reporter’s absence would go wholly unnoticed — I made an executive decision. I would pass on the NutraSweet party. I had some sampling of my own volition to do.

***

My publisher had sent word through my editor the week before: “Tell the kid to get his suit pressed.” (Apparently I struck him as a bit rumpled the first time he saw me in action away from the office.) My father, who grew up upstairs from Prince Valet in Jackson Heights, told me you don’t just get your suit pressed — you get it dry cleaned. My mother was still peddling the same advice she’d been giving me and my sister since we were kids.

“Put five dollars in your shoe.”

What was I — an idiot? Granted, I had never been to Chicago before, but I knew how to clean myself up, knew how to dress myself and knew enough not to get — as my mother confided to my sister she was afraid would happen to me in the strange city because I was too nice — “rolled”.

I was 26. If I hadn’t been “around,” I’d also venture to say I wasn’t an utter naïf. I was pretty confident I could handle getting on an overly early flight to O’Hare on a Monday morning (magazine too cheap to pay for a civilized extra night’s stay), getting to McCormick, getting a convention badge and getting on with IFT. At the first available break, I managed, all by myself, to uncheck my luggage at the convention center and check into the adjoining hotel when my room was ready. I even knew enough to tell housekeeping, when they came around to inspect, that no, I had not enjoyed a Heineken and M&M’s from the minibar, I had only just entered this room five minutes ago, that must have been the last guy.

Not rolled by hotel management. That was encouraging.

God, I was tired. The flight was too early for my nocturnal system, and United Airlines mysteriously offered only caffeine-free diet cola. No caffeine? What was the point of that at seven in the morning? Settling briefly into my room, I flipped on the radio to hear what Top 40 sounded like in Chicago (pretty much the same as it sounded everywhere else) and, just as the minibar lady with her clipboard left, the new Great White hit, “Once Bitten Twice Shy,” caught my ear.

You’re lookin’ tried

You’re lookin’ kinda beat

The rhythm of the street

Sure knocks you off your feet

Per Great White’s expert reading of my mental state, I would’ve loved a nap right about then, but I had miles of trade show booths to go before I could sleep.

Back to McCormick. Back to the floor.

***

I’d always wanted to go to Wrigley Field, but so did everybody else. The Cubs were hot stuff in June 1989. They held first in the National League East (damn it), so that made their already limited inventory of tickets even scarcer. Throw in the advent of night baseball on the North Side — lights were switched on for the first time the previous summer — and games that took place after traditional working hours were in near impossible demand.

At the end of my first day at IFT, I returned to my room, turned on WGN, Channel 9, and saw the joint was jumping. Another sellout, they exclaimed — it was all happening at Wrigley.

Before I nodded off for the evening (it didn’t take much), I opened the Tribune sports section and examined the upcoming schedule. The Cubs were home again tomorrow night, but that figured to be sold out, too. They had a day game the day after that, but I was flying home that night and how would that work? What was I supposed to do with my stuff? How does one approach a Wrigley Field scalper? Does one risk getting rolled? And what about my flight out of O’Hare — how close exactly was the airport to the ballpark?

I wasn’t a naïf, but I also didn’t know very much.

Yet I did know this, or at least I allowed it to occur to me: Chicago had another ballpark, home base to another team, one whose games were immaterial to divisional races and — based on my scanning of box scores — did not loom as major attractions. Best of all, that ballpark would, in the spirit of IFT, be open for business this week; the next night, in fact. It had never really crossed my mind to see it, but I was in Chicago, it was there on the South Side, relatively close to where I was from my best reading of Second City geography…

What the hell? If Wrigley was prohibitive, I’d sample the other place.

***

He called me sir. He called everybody sir, I suspected, out of professional courtesy.

“Good evening, sir.”

“Good evening. Comiskey Park, please.”

“Yes sir.”

The NutraSweet party was in my cabdriver’s rearview mirror. Somewhere ahead of us, baseball. Baseball in Chicago. Not the baseball in Chicago I’d always yearned to be a part of, but it would do for now.

It’s not like I’d never heard of Comiskey Park before. It, like the White Sox, penetrated my consciousness every few years. Bill Melton led the American League in home runs with an absurdly low total when I was a kid, the season before Richie Allen became Dick Allen. Richie Zisk became a free agent bargain when I was in junior high. Disco Demolition became a catastrophe the summer between my being a high school sophomore and junior. In 1983, while I was in college, they hosted an All-Star Game and then morphed into the embodiment of Winning Ugly. It was supposed to refer to their style of play, but it could have been an allusion to their ever more hideous uniforms.

You thought of the White Sox in the 1970s and 1980s, you thought of oversized sluggers in lumpy throwback blouses (with or without shorts), or horizontal stripes that could never quite take the measure of a Ron Kittle. The last time, by 1989, that I had thought more than a minute about the White Sox was probably 1986, when Chicago traded misplaced Met icon Tom Seaver to Boston, which I appreciated, because there had been talk he might wind up on the Yankees.

Tom Seaver looked good in every uniform, but that’s not one I ever wanted to see him try on.

***

“Sir?”

“Yes?”

“If you don’t mind me asking, are you a sportswriter?”

The cabdriver’s question tickled me. I had once been mistaken, sort of, for a Mets ballplayer, but I chalked that up to my youth (barely 19), my Mets jacket (a Starter), my surroundings (the Tampa airport, across the bay from the Mets’ Spring Training home in St. Pete) and the person who made the mistake (lady in the airport gift shop who definitely needed her eyes and/or judgment checked). This case of mistaken identity? I guess it was plausible. Though I had left my suit jacket and tie back in the hotel, I was still wearing a buttondown shirt and my suit pants — ever less pressed, but still presentable. Am I what a sportswriter looks like? They’re not all rumpled like Oscar Madison…or me, normally? I can pass for a sportswriter?

“No,” I said. “Just going to the game.”

I didn’t ask, but I figured my driver didn’t get many fares to Comiskey Park. In 1989, the White Sox were dead last in American League attendance, drawing a smidge over a million by season’s end. In 1989, someone would probably have to have a reason to want to go there on a Tuesday night, like it was his job. They would literally have to pay you to go see the White Sox.

Not me. They paid me to go to IFT. And the NutraSweet party, I suppose.

He mistook me for a sportswriter. I liked that.

***

The NBA draft was in progress, and attached to the cab’s meter was a news ticker of sorts. Interrupting the steady stream of traffic updates was this flash: The Chicago Bulls, with the sixth pick, selected Stacey King, from the University of Oklahoma. There was much hooting and hollering to be heard over the cab radio. The dispatcher was happy. The other drivers were happy. My driver was happy.

“Sir, do you follow basketball?”

“A little.”

“Everybody’s very excited about this draft pick.”

“Uh-huh.”

The Bulls were worth talking about in Chicago. The White Sox weren’t.

***

Six-something dollars (plus tip) from the convention center hotel, we were there: Comiskey Park. It didn’t look like much — the major construction site next door perhaps lessened its impact — and it didn’t appear to be in the middle of anything you’d want to be if you didn’t know your away around. To minimize the possibility of being rolled, I asked my courtly driver if there were cabs around after games. No, he said, there weren’t, so he gave me a business card with the phone number of the cab company circled. Just call, he said, and one will come to get you.

Sounded reasonable in theory. I thanked him for the ride and the information, if not the sportswriter remark.

***

As predicted, no problem getting a ticket to a White Sox-Rangers game in late June. Walked right up to the window (no wait) and went for an $8.50 box seat down the first base line. You couldn’t get a box seat at Shea in those days without major finagling. Three weeks earlier, I took my friend Chuck, visiting from out of town, to his first Mets game in ages. We had to buy our tickets from a guy who was selling them out of his trunk.

Not the case on the South Side of Chicago. Getting in was a breeze. Getting home might be another matter, but that was for later.

***

It reeked of baseball. That’s what Comiskey Park did. Reek does not carry pleasant connotations — “to be pervaded by something unpleasant” is the dictionary definition — but that was the word that came to me 21½ years ago. I meant no offense by it. To the contrary, it was the highest compliment I could pay it. What better to reek of than baseball? What better to sense oozing out of the pores of a building than 80 seasons of national pastime? I knew very little about Comiskey Park when I bought that ticket, but I could feel everything about it once I stepped inside.

This place reeked unapologetically of baseball, baseball and more baseball. Baseball had infested this ballpark like termites. The baseball was peeling from its walls. The baseball formed puddles at your feet. You needed a bucket to catch all the baseball dripping from its ceilings.

There was no mopping it up, no patching it, no stepping around it. You walked through Comiskey Park, you were immersed in a flood of baseball.

Best. Reek. Ever.

***

The first thing I loved about Comiskey Park was grasping that it had been there forever. It went up in 1910, before Fenway, before Wrigley. If I didn’t know the exact date on the night I was there, I could have guessed it was the oldest ballpark in the majors. It, unlike me, had been around. And unlike its more celebrated contemporaries, it didn’t emit preciousness. Fenway and Wrigley had been lauded my entire life for being what a ballpark was supposed to be, yet Comiskey didn’t need accolades. Its sturdiness spoke volumes. This was a ballpark that kept to itself and didn’t demand attention.

Yet it had mine, instantly. No, the whitewashed brick outside augured nothing overly sensational, and the utilitarian concourses told you mostly that these walls had been well lived in between (as did the concession stands, which were still selling 1983 A.L. West Champion buttons six years after the fact). But when you ambled down the first base side and came out the tunnel to your right field box seat and your $8.50 became the investment of a lifetime.

You were in baseball paradise. Nothing else existed except baseball. You just knew you were in the right place. The double-decked grandstand; the way it turned at sharp angles as if to put its arms around the field; the roof above the top deck warding off glare and rain for generations; the posts holding the roof aloft and keeping everybody on top of the game; the arches behind the bottom deck that let in shafts of natural light and a suggestion of the neighborhood beyond; the leafy trees behind the arches; the festive scoreboard ready to ignite at a homer’s notice; the picnic area where I once read Claudell Washington would help himself to ribs; the yellow accents; the green seats; the green fences; the green grass; the incredibly green grass…more than any ballpark I’d ever seen or would ever see, this place said in plaintive fashion to me, “Baseball.” That was it. That was all it had to say.

Once bitten by Comiskey Park, you were never shy about loving it.

***

A game between the 1989 Chicago White Sox (managed by Jeff Torborg) and the 1989 Texas Rangers (managed by Bobby Valentine) served mostly as an excuse to allow Comiskey wash over me, much as the shower Bill Veeck had long ago installed in the center field bleachers once refreshed and invigorated his customers. I cheered with temporary conviction for the home team, moaned theatrically at the success of the road team — featuring five players (starting pitcher Kevin Brown; left fielder Sammy Sosa; first baseman Rafael Palmeiro; right fielder Ruben Sierra; and second baseman Julio Franco) whose careers would extend to at least the mid-portion of the first decade of the next century; and came mighty close to picking off a foul ball (a father and son, actual White Sox fans, nabbed it in the row ahead of me). Otherwise, I just soaked up the evening. There was Nancy Faust’s organ and Old Style beer and the low, contented buzz of a night game in late June when there are few in the stands (9,631 announced as attendance) and not much on the line (the Sox were 17 out) and no reason whatsoever to want to be anywhere else in the world. The Mets were in Montreal, the NutraSweet party was a million miles away, I was where I always wanted to be but just hadn’t known it until I found it.

They should have had to have dragged me out of there kicking and screaming. It should have taken a Chicago police presence on the scale of what the first Mayor Daley unleashed on the 1968 Democratic Convention to move me. I should have claimed eminent domain and declared my box seat a sovereign nation. Instead, I bolted early, after six innings.

I was worried about getting a cab back to the hotel. Not knowing from the El, I didn’t want to be stranded on the South Side of Chicago; Jim Croce advised me years earlier that if you go down there, you better just beware of a man named Leroy Brown. And even if it wasn’t as bad (bad) as all that, I still felt a little uncomfortable with the notion of a sparse crowd filing out and me standing around a mostly deserted ballpark waiting on a ride. So while there were still people on the premises, I figured the smart thing to do was leave paradise behind with three innings to go, find a pay phone, use that business card and make a smooth exit.

I’m not convinced that my cab ever came. The seventh became the eighth and patrons began to trickle out in my wake. My anxiety quotient was rising at the thought of being the last out-of-town fan standing around in the dark. Thus, when a taxi bearing a name different from that on the card wandered by in my general vicinity, I hailed it down, jumped in the back seat and, before the driver had a chance to confirm I wasn’t the fare he’d been sent to pick up, I directed him to my hotel.

I may not have known the South Side, but I’m from New York. I know how to steal a cab.

***

Leaving three innings of the ballpark with which/whom I fell in love on the table made sense after the sun went down on June 27, 1989, and it doesn’t really bother me now. Comiskey had proven its point to me. She was The One. I knew it. I wasn’t a ballpark aficionado when I showed up. I had no more than a very vague desire to see as many of them as I could, maybe one day see them all, but I didn’t walk in with an agenda. My life list was only five before Comiskey. Nothing that preceded it in my travels, however, could approach it for beauty and feeling and baseball. Not Fenway, not Shea even.

Five years later, blown away by what had been constructed in Baltimore, I admit I had to think about it, but no, Comiskey could not be topped. Her cousin in Detroit touched me deep inside upon our one dalliance in 1997, but Tiger Stadium somehow fell short, too. PNC Park, this century’s gift to the future…only in a discussion that includes Comiskey could the jewel of Pittsburgh be considered an also-ran.

There would be no place like Comiskey Park for the rest of my life. Soon enough, there wouldn’t be a Comiskey Park. That dusty construction site next door would see to that.

***

Comiskey Park was shuttered forever in September 1990. I’ve been alternately sad and pissed off about it ever since. I suppose I want to be sad and pissed off about it. Comiskey Park deserved to survive and celebrate a centennial this very year. Getting all out of sorts over its enforced absence from the current baseball landscape is my way of keeping it alive. When I need my dismay stoked, I pull out what amounts to my bible in this matter, Baseball Palace of the World: The Last Year of Comiskey Park by lifelong White Sox fan Douglas Bukowski.

Bukowski took part in a doomed preservation effort — Save Our Sox — right up to the end. It didn’t go anywhere, but the diary he left behind in the form of his book is every bit as affecting to me as Comiskey itself. Bukowski refused to be taken in by club owner Jerry Reinsdorf’s clarion call for progress and amenities, the twin siren songs of all ownership-driven pushes for new/more profitable facilities. Comiskey Park was four years older than Wrigley Field. Nobody was tearing down Wrigley, Bukowski argued. They were maintaining it. Comiskey needed devotion, not demolition. Reacting to then-commissioner Fay Vincent’s likening Wrigley to a cathedral (and Comiskey to “an old car”), Bukowski wrote:

St. Peter’s stands as a landmark to the baroque. People visit to get a sense of seventeenth-century Rome; they do not complain about the lack of central heating or air-conditioning. For the cathedral metaphor to hold, Fenway and Wrigley have to appeal through their sense of the past. Fans venerate both — and Comiskey — because they are so unchanged: the field and stands are virtually the same as they were in the days of Ted Williams or Hack Wilson or Luke Appling.

All that has been done to Wrigley Field is good housekeeping and regular maintenance. The commissioner is confused when he talks about [modifications to Wrigley] moving forward “with the interest of the fans.” Skyboxes and night baseball are to the benefit of the few and well-heeled, not the average Chicago Cubs fan. At least Vincent had it right about Comiskey Park not changing. That is precisely what makes it a cathedral of baseball.

Douglas Bukowski came off as a bit of a curmudgeon as he chronicled his 1990 Comiskey farewell (and retained that chip on his shoulder in the best of White Sox times), but he had every reason to do so. His righteous love of his ballpark, well-earned and well-honed, is palpable. I can muster only a scintilla of his depth of appreciation of Comiskey Park, but I totally feel it still.

***

Comiskey’s 1991 replacement, also named Comiskey Park until a sponsor came along in 2003, was not what it was cracked up to be. Everything was farther away from the field. The upper deck stood absurdly high. A major renovation effort would be needed in its second decade to make it palatable to White Sox fans once the novelty of its modernity wore off. And in the great sweep of ballpark history, new Comiskey represented an aesthetic setback. It opened one year ahead of the great success of the age, Camden Yards. New Comiskey feinted toward nostalgia for inspiration and delivered no sense of timelessness. Camden, of course, became legendary as the first brick in the revival of baseball’s architectural integrity.

Peter Richmond, author of Ballpark: Camden Yards And The Building Of An American Dream, and presumably a disinterested party, framed the differences between what the White Sox gave up on…

Comiskey offered an antidote to the daily jungle. It was one of the first parks to install lights. In fact, Comiskey was a better park for watching baseball than Wrigley. It was small, and built on a human scale, for a human-scaled game. Its upper-deck front rows were forty-five feet closer to home plate than Wrigley’s. Down in the street-level concourse, the scents were shellacked onto the walls, adhering to the brick like the very soul of the game made manifest; cigar smoke, Old Style beer, sausage, cooking oil.

…and what they were rushing toward:

[T]he upper-deck cant — 35 degrees, among the steepest in the majors — was enough to induce vertigo. Its seats furnished a view of the Dan Ryan Expressway and its caravans of trucks, and the aural accompaniment was the incessant hum of rubber tire on highway. We also heard a train, but we couldn’t see it.

The steep upper deck was required to furnish sight lines; without columns below, the upper deck in a stadium has to be set farther back. With the extra height forced on it by three decks of luxury boxes — they are wincingly prominent, like the prow of a ship, the staterooms looking down on steerage — the upper deck up top has to be cantilevered even more.

Old Comiskey was home cooking, a one-of-a-kind family recipe. New Comiskey may as well have been concocted in some food technologist’s lab. You don’t need that refined a palate to tell the difference.

***

When your favorite ballpark ever is one you can’t go to any longer, you take what you can get. You read your books, you search out blogs and pictures, you keep an eye open for video. You sit through an hour of the morose John Candy comedy Only The Lonely only because one scene takes place in Comiskey Park; Candy takes Ally Sheedy for a nighttime picnic in the infield (he’s a cop and he knows the security guard). Candy laments it’s a shame they’re gonna tear this place down.

I’m not a White Sox fan, beyond reflexively wishing them well because they’re not the Cubs. I never begrudged them their plucking Tom Seaver off our unprotected pile in that abortion of a compensation pool draft in 1984 — it just showed they had good taste. But other than the 2005 postseason, when their fans deserved a break, and whenever they play the Yankees, I’ve never particularly cared what they do. I have no attachment to the White Sox. But oh, how I adored Comiskey Park and how I’d love to be able to go there again, but that’s never happening again, obviously. All that sits where it used to stand (besides a parking lot) is a marker signifying the site of home plate, with its year of birth and its year of death.

Seeing it on one of my visits to Comiskey’s half-baked replacement only pissed me off and saddened me more.

But that’s not what ballparks, even the ballparks whose unnecessary passings you endlessly rue, are for. Ballparks are for the best moments in our lives. Ballparks are where I’ve had most of mine. Whether it’s six innings one unplanned evening far from home; or thirty-six seasons in what you considered your home; or the throwback field exponentially enhanced by an ingeniously resuscitated warehouse; or the desultory circle on foreign soil and fake turf that made you think you were inside a warehouse; or that plastic place planted off some highway which everyone else thinks is splendid but you still believe to have been soulless; or that place that took the place of your home — the place you’ve given 63 chances to win you over and hasn’t quite after two seasons, but you’re going to give it as many chances as it takes…well, I must have a very limited imagination, because from Olympic Stadium and Royals Stadium, through Citi Field and Shea Stadium, all the way to Camden Yards and Comiskey Park, there’s nowhere else I’d rather have gone and that I’d rather go than the ballpark. Any one of ’em.

Thanks for taking these journeys with me to my 34 ballparks. No doubt I’ll let you know when I get to a 35th.

by Greg Prince on 21 December 2010 11:05 pm Perhaps it’s this miserable cold I’ve contracted and can’t divest myself of, or it’s the impending winter solstice (you mean it’s still fall?) but something overwhelming has occurred to me this evening:

I don’t care what the Mets are doing at the moment.

I will care. Of course I’ll care, but for now, I’ve run out of care. I don’t care who they’re looking at to fill out the rotation or to play second. I don’t care about trade rumors or how much budget they have to tinker with. I don’t care how poorly they frame themselves or present themselves or what kind of ticket deals they’re offering.

I’ve OD’d on year-round Mets coverage, my own included. It used to be if you came across a baseball brief in the fourth week of December, no matter how brief, no matter what it was about (but especially if it was about your team), you felt blessed. “They’ve extended their affiliate agreement with Visalia? WOW!” Now we grow antsy if there’s “no news” about the Mets on a given day.

Of course there’s no news. It’s the fourth week of December. If it was news, it would have happened by now. Or if it’s going to be news, it will happen eventually. Either way, the season will begin when it’s supposed to begin, not a tick sooner. Maybe if a boffo free agent were still prowling the open market, I could buy into the chronic curiosity, but there’s nobody out there worth losing a minute’s thought over on December 21 or December 22. You’re going to hit refresh for the latest word or lack thereof on Chris Young? Or Jeff Francis? Or Freddy Garcia?

Don’t. Winter is nature’s way of telling you not to give a fig sometimes.

by Jason Fry on 19 December 2010 5:33 pm It’s not yet the Baseball Equinox — though I’m eagerly awaiting word from Greg that we’re finally closer to new baseball than we are to old. But nonetheless, in the last couple of days I’ve felt a quickening somewhere in my blue-and-orange soul.

Spring's coming. Promise. And it has nothing to do with our front office. Just having Sandy Alderson on the payroll is grounds for celebration, as is having him make smart hires and calmly explain to everybody from Mike Francesa to panicky Mets fans what is and isn’t happening, and that there’s a plan that’s being stuck to. (And hey, getting to talk to the man himself is certainly a welcome new experience.) Still, even the wisest doings of men in jackets and ties can only do so much.

This was different.

And welcome, as I was beginning to worry a bit.

After the 2010 season mercifully expired with Oliver Perez and a bunch of Jerry Manuel Veteran Leaders (TM) taking up space at Citi Field, I didn’t particularly want to think about my misbegotten baseball team for a while. The Giants and Rangers offered a welcome diversion, but then — as always happens — baseball was over and it was winter.

For a while filling my days wasn’t a problem: I was insanely, frighteningly busy in a medium-term freelance gig I’d taken, and I was trying to finish a book that had been squeezed into night-owl hours but whose deadline hadn’t moved. It was about the most tired I’d ever been — I registered the departures of Omar and Jerry and the arrivals of Sandy and J.P. and DePo with what approval I could muster, but mostly I just stayed tired.

And then when I got my breath back a bit, it was clear that the Mets weren’t going to be making big headlines. No Cliff Lees or Zack Greinkes or even Orlando Hudsons were going to be showing up to awkwardly button a jersey over a shirt and tie (seriously, this looks ridiculous) and say can-do things. No, it was Paulino and Carrasco time. I’ve watched the Knicks a bit, with what started as a professional duty turning into a genuine rooting interest. (Perhaps sensing the arrival of a Mets fan, they’ve now stopped winning.) Today I checked in on the Giants, decided to watch them finish off the Eagles, and found myself profoundly grateful that I didn’t really care as Tom Coughlin’s bunch gagged horribly. No offense meant to the Knicks and Giants (or the Jets, Nets, Rangers, Isles, Devils and anybody else), but the more I reallocate my portfolio of Sports Caring, the more I realize that for me there’s baseball and there’s everything else.

So what lifted my spirits? Baseball cards. Yes, in December.

Topps just released 2010 Bowman Draft Picks, news that I greeted with the kind of enthusiasm appropriate for a minor card set purporting to belong to a year that’s over. But then I noticed that Justin Turner had a card — Justin Turner who’d gone into The Holy Books with an evocative but inappropriate Norfolk Tides card from his time as an Oriole. Cool, I thought (becoming one of at least five or six people on the planet to do so), now I have a Justin Turner Mets card.