The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 5 March 2010 5:31 pm Welcome to Flashback Friday: Take Me Out to 34 Ballparks, a celebration, critique and countdown of every major league ballpark one baseball fan has been fortunate enough to visit in a lifetime of going to ballgames.

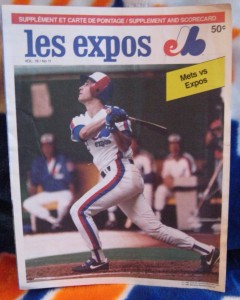

BALLPARK: Olympic Stadium

HOME TEAM: Montreal Expos

VISITS: 1

VISITED: June 16, 1987

CHRONOLOGY: 5th of 34

RANKING: 34th of 34

Two things strike me as I consider the ballpark that is technically my least favorite of those I’ve visited:

1) Despite considering Olympic Stadium the worst place I ever saw a major league baseball game, I had a marvelous, memorable time there and would not want to have not experienced it.

2) Despite having had a marvelous, memorable time at Olympic Stadium, I consider it the worst place I ever saw a major league baseball game.

I think these conclusions say less about Olympic Stadium and more about baseball. Stade Olympique really was a lousy place for a game, and it didn’t matter one bit. Perhaps if I had been a Montreal Expos fan it might have gotten to me in the long term, but I was just a traveler on a pilgrimage, and I came away highly satisfied at the results of my journey. Clearly, the least impressive ballpark available is better than just about any place in the world that isn’t a ballpark.

Olympic Stadium’s No. 34 on my ballpark list — and, I don’t know, No. 36 on my life list. Where else would you rather be than at the ballpark? Even the lousiest of ballparks?

Which is what Olympic Stadium was. Lousy…yet gloriously so.

Its main drawback was it was less like a ballpark than a basement, and not the National League East kind (the Expos were doing pretty well in 1987). Or maybe it was more like a warehouse, but I don’t mean in the fun Camden Yards sense. More like those refrigerated warehouses I’d visit when I was covering beverages full-time. It was cold, there were forklifts and there was plenty of beer. Beer’s not a drawback at the ballgame, but, as you probably saw if you watched Mets @ Expos games on TV, it never looked finished.

This brings to mind one of the great things about going to a ballpark you’ve only seen on television. It’s like taking the Universal Studios tour. Look! It’s the shark from Jaws! To a great degree, you feel like you’re visiting a movie set, except everything is real, yet more so. The orange roof: really orange. The long dugouts: really long. The French: really foreign.

It was my first bilingual game (more French than English) and my first indoors game; the roof had just gotten sealed in 1987. I never got used to indoor baseball, but I can see why they planned it that way in Montreal. My friend and I were there in the middle of June, and it was not a little chilly at night.

Still, it’s unnatural. Olympic Stadium was a science experiment gone awry. If a kid could grow enough mold on a piece of bread, the result would be the same. It was just that charming.

And yet…I loved being there. I loved seeing the Olympic Stadium set. I loved baseball in two languages. I loved wandering through an indoor plaza filled with smoking Quebecers and smoked meat (even if didn’t particularly want to be singed by either). Though the attendance was middling (20,000) and the environs were dank, the scene was as festive as Olympic Stadium could be. It probably helped that the Mets were there. Mets fans liven up any scenario — we built a 7-0 lead — but Expos fans, once their team began scoring a few meaningless runs, went nuts. Or maybe those were the forklifts I heard. Whatever it was, it wasn’t sad. It was fun.

It just wasn’t as good as the other 33 ballparks I’ve attended. It was Olympic Stadium.

***

At the risk of repeating myself, I have written about this trip before in a slightly different context. For those who have somehow not committed every Flashback Friday to memory, what follows is that entry of June 8, 2007.

***

No fictional character in the popular culture — not Sidd Finch, not Chico Escuela, not Oscar Madison — has done more to enhance the Metropolitan legend than Keith Hernandez. That Keith Hernandez is technically real shouldn’t detract from his contribution to the canon one bit.

I would think that every Mets fan knows what I’m talking about, though I could be wrong. On DiamondVision during the Delgado-Benitez balk game last week, Keith appeared to ask some lucky fan which Met appeared as himself on Seinfeld. The hint couldn’t have been any plainer than the questioner’s face.

The guy they picked to answer said Tom Seaver. He still won the Uncle Jack’s prize package. I wished they’d have given it to me so I could have poured that steak sauce on his head.

The answer was Keith Hernandez. Of course it was Keith Hernandez! Who doesn’t know that? Did they find one of those people who “doesn’t look at television”? Geez!

On February 12, 1992, Keith Hernandez, his playing days not two years over, made Mets and television history by guest-starring as Keith Hernandez on the then-cult sitcom Seinfeld. He was very convincing in the role. Jerry met him at a health club and developed what we would today call a man crush on him. Elaine dated him until his smoking turned her off. And Kramer? Well he and Newman said they didn’t care for Keith Hernandez.

KRAMER: I hate KEITH HERNANDEZ — hate him!

NEWMAN: I despise him.

ELAINE: Why?

What follows is one of the great moments television has ever beamed, a dead-on parody of the film JFK in which Jerry’s neighbors explain in Zapruderish detail why they so loathe the first baseman New Yorkers so loved.

NEWMAN: June 14, 1987…Mets-Phillies. We’re enjoying a beautiful afternoon in the right field stands when a crucial Hernandez error to a five-run Phillies ninth. Cost the Mets the game.

KRAMER: Our day was ruined. There were a lot of people, you know, they were waiting by the players’ parking lot. Now we’re coming down the ramp. Newman was in front of me. Keith was coming toward us, as he passes Newman turns and says, “Nice game, pretty boy.” Keith continued past us up the ramp.

NEWMAN: A second later, something happened that changed us in a deep and profound way from that day forward.

ELAINE: What was it?

KRAMER: He spit on us. And I screamed out, “I’m hit!”

NEWMAN: Then I turned and the spit ricochet of him and it hit me.

ELAINE: Wow! What a story.

JERRY: Unfortunately the immutable laws of physics contradict the whole premise of your account.

Yes, Jerry would prove beyond all reasonable doubt there was no magic loogie — and Keith would come along in the second half of the hourlong episode to reveal the true culprit.

KEITH: Well lookit, the way I remember it I was

walking up the ramp. I was upset about the game. That’s when you called me pretty boy. It ticked me off. I started to turn around to say something and as I turned around I saw Roger McDowell behind the bushes over by that gravelly road. Anyway he was talking to someone and they were talking to you. I tried to scream out but it was too late. It was already on its way.

JERRY: I told you!

NEWMAN: Wow, it was McDowell.

JERRY: But why? Why McDowell?

KRAMER: Well, maybe because we were sitting in the right field stands cursing at him in the bullpen all game.

NEWMAN: He must have caught a glimpse of us when I poured that beer on his head.

Wraps it up nicely, no? Except for one nagging detail:

The Mets were not at Shea on June 14, 1987 losing to the Phillies. They were in Pittsburgh beating the Pirates. An immutable law of physics — the one that would specify you can’t be in two places at one time — contradicts the whole premise of everybody’s account.

It’s still a funny episode, but it’s always bugged me that Seinfeld chose this particular date to portray this fanciful incident. I remember June 14, 1987 very well. It was twenty years ago next week and it represented a milestone in a spring full of them.

June 14, a Sunday, was the day Stephanie left town. Not forever but, save for a few visits, for three years. She was in New York to go to plays and museums to earn college credits over six weeks. Her six weeks were up on June 14. We spent the last five of them together, but now it was time for her to go, damn it.

Now what do I do with myself? First thing I did after putting her on a train south to Florida was grab a seat at a bar in Penn Station, order a drink and ask the bartender how the Mets did today. He didn’t know, which I thought was highly irresponsible. The Celtics and Lakers were playing for the NBA championship on his TV. I think the Lakers won the title that day. I’m not sure. I didn’t much care. It was left to Sports Phone to inform me the Mets beat the Pirates 7-3, Sisk going 4-2/3 for the win, Darryl and, yup, Keith homering. We were still floundering in the N.L. East, 7½ in back of the Cardinals and behind the Cubs and Expos for bad measure. But it was something.

Now what else do I do with myself?

Stephanie and I met on May 11. Our first date, the Mets and Giants, was on May 15. We were spending most available waking hours together by the end of May. Our first fait accompli discussion of marriage was June 4. It was whirlwind, but it was real. Now it was hurry up and wait while she finished her sophomore, junior and senior years of college (she was only 19, for goodness sake) and I did whatever it was I had to do to become a viable member of society by the time she was done at USF.

So what do I do after getting the Mets-Pirates score? I take off to Montreal.

I had a very good friend who facilitated my meeting Stephanie. If he wasn’t in New York on that same arts program (trying to forget his old girlfriend) then I would never have been in the lobby of the hotel where my future wife was staying in May. Now it was June and not only was she riding the rails home but so was her roommate who happened to be the girl my friend got involved with that same spring (got that?). At that very moment, actually, they were broken up and he was all “let’s drink and forget her!” It was his idea to go to the bar in Penn Station.

It was my idea to go to Montreal and see the Mets play the Expos.

My friend had a whole family psychodrama playing out, culminating in his parents flying into Newark the following Friday. From there he and they would drive back to Miami. Or Philadelphia where they were from originally. Or something. I forget what the deal was exactly except he kind of invited himself to stay over at my house between Sunday and Friday, which was fine with me, not such a popular idea with my mother who really didn’t like having houseguests (despite a plenty big enough house to accommodate several). I needed to get me and my friend out of town. And plan a future. But first get out of town for the week.

I know, I said. Let’s drive to Montreal! The Mets will be there! My friend wasn’t a big baseball fan but had this accommodating habit of being into whatever you were into at the precise moment you brought it up. Like Zelig, if you ever saw the Woody Allen movie in which the title character of yore morphs right into the prevailing situation. In my friend’s case, it occasionally seemed insincere and a little desperate, but this time it was very convenient. He was totally into this impromptu sojourn into another country.

I was 24 and sporadically employed. He was 21 and had nothing to do for five days. The loves of our lives had just split. What better remedy than ROAD TRIP!?

So we did it. On Monday the 15th, three of us — me, my friend and another summer-semester castaway who just happened to need a ride to her grandmother’s in Burlington, Vt., piled into my 1981 Corolla and headed north. I barely drive round the block these days if I don’t have to, but kill time in Montreal? Sure! Drop off a virtual stranger in Vermont along the way? Why not?

As is my custom, I didn’t hit the road until late in the day Monday. In those days, I took pride in being a nocturnal animal, and driving at night didn’t bother me a bit. Besides, the summer solstice was fast approaching. It was staying light late and we were going in the general direction of the Arctic Circle. The immediate future was so bright, we had to wear…well, you know.

Day became night and New York became Vermont. The Mets on WHN faded in and out. The first of the four-game series pitted Doc Gooden, recently back from drug rehab versus Dennis Martinez, a recovering alcoholic getting a final shot. It was on Monday Night Baseball. It was also going badly: Martinez pitched a shutout (infer what you will about their respective addictions). Our third wheel guided us over the river and through the woods — or at least across Lake Champlain — to Grandma’s house. We let her out on a quiet Burlington street probably after 10 P.M. We spent maybe six hours together, the three of us, after being casually acquainted since mid-May. We shared an adventure, or part of one. And then I never saw her again.

Montreal lay ahead, but the Canadian border was of more immediate concern. This was my first trip to Canada and I didn’t know what to expect. I was told I didn’t need a passport but I had conflicting reports on whether I needed a special insurance card to drive there (Mom said yes, the Vermont girl said no; KBS Insurance mootly mailed one to the house that arrived after I returned, so I guess no). What I did understand was I was getting tired. My friend and I switched seats and he drove.

Well after midnight, we made it to Canada. A border guard greeted us with a smile. Welcome to Canada, what is your business here? My friend, at the wheel, told him, “We’re here to see a couple of ballgames.” Another smile from the guard. With almost no hesitation, he waved us through. I’m glad the Mets-Expos rivalry carried such weight.

Just like that, another country. It was still another hour and some to Montreal. Unlike in later years, I planned this not at all. Today, I research hotels and transportation and baseball tickets. Then, I figured, we’ll get there when we get there and we’ll find our way. I was quite spunky then or just became more fretful as I grew older.

As Montreal approaches, you reach a toll bridge. A Canadian toll bridge that wants a Canadian toll. A quarter, at least then. I panicked. Because I panicked, my friend panicked. Who had Canadian change? In fact, back in Vermont when we gassed up, the attendant gave me back Canadian change and I politely asked for real money. The funny thing is I seemed to believe I was the first American who ever entered Canada with only American money. I explained all this to the tolltaker at the bridge at probably two in the morning. He waved us on through. What a country!

We found downtown Montreal in the dead of night. A well-lit dead of night, I should point out, replete with restaurants advertising smoked meat sandwiches. Within downtown, we found a Holiday Inn. Looked good to us. Disheveled, unshaven and dressed nothing like businessmen, the desk clerk, who seemed mildly suspicious of our business in Canada, offered us the businessman’s rate if we could produce some proof that we had some. Business, I mean. My “Freelance Writer” card only confused him. My friend had an expired press credential from a defunct newspaper. That did the trick; we got a room and by 3:45 A.M., we saw it getting light out. I think the rate sounded absurdly high anyway, but that was in Canadian dollars. As I was catching on (and had been clued in ahead of time), it translated to like five bucks American.

That became the running joke the next morning. My friend got up and exchanged some of our money at a nearby bank and ya gotta see the prices. Everything costs like five bucks because, well, it’s Canadian.

We did what any two American guys would do in a bilingual city filled with mystery and intrigue. We went to McDonald’s. Sticking with my weird insistence on not being a stranger in a strange land, I tried to order a Quart de Livre. The girl behind the counter said, “Quarter-Pounder, what else?” Ah, the hell with it. Yes, plus fries and a diet Coke please.

It was all prelude to our business in Canada, the ballgame. The one piece of information I had cobbled together was there was subway service between downtown (which is where I assumed we were staying — it could have been midtown for all I know) and The Big O. In Montreal, you took the Metro to the games. They even talked about it on the Mets’ broadcasts from there. Our hotel was near the line that would take us to Pie IX, the local version of Willets Point. Man, I thought, this is not bad. I’m in some foreign country and I know how to get to the ballpark.

Unlike the way it was painted in the dying years of the franchise, there were Expos fans in Montreal in 1987. Enough of them so they populated a subway car. We followed them the way tourists on the 7 follow me so they don’t get lost. (At least a couple times a year that happens; I kinda dig it.)

It worked. We got off at Pie IX and never had to go outside. Just that season, the Expos finally managed to get a roof on Olympic Stadium. It wasn’t retractable as advertised 10 years earlier when it opened for baseball, but it shielded you from the elements — not a huge concern in June — and kept with the general Canadian ethos of avoiding the great outdoors. The walk from the subway to the ballpark was all indoors.

It included a pass through a lively plaza. People milled and ate and smoked and a band played “Don’t Forget Me (When I’m Gone),” a hit by Glass Tiger from the previous fall. My friend and I looked at each other and laughed out loud. Glass Tiger, we both knew, was a Canadian group and this cover band doing their song played into our concept of Canada as a country with a complex. Listen! It’s the No. 2 hit in the States! And it’s Canadian!

Tickets were easy to get. We produced Canadian money but, again, that wasn’t necessary, just cost-effective. Other Mets fans on their own sabbaticals were here, some buying tickets with U.S. currency. Somehow I felt a little offended that they didn’t make the effort to use Canadian money. (Hmmm…maybe I was the one with the Zeligaffliction.)

Box seats were maybe 15 bucks (or like five bucks American). Good deal. We sat on the first base side. I looked around and, gads, what an ugly place! Don’t get me wrong. I was happy to be there. It was exciting. It was a ballpark and the Mets were going to play. But this was everything it was said to be and less. Just because it was half in French didn’t make it slightly charming. So much space, so much of it useless. There was a veritable lumber yard behind the centerfield fence — some wood that had been left over from a construction project that ran out of funding. In the next phase of my career, I’d visit cold warehouses stacked with 24-packs of beer or soda and be reminded of Olympic Stadium.

That’s the critique in a nutshell. Too big for its own good. Too deep, too hollow. Too artificially loud thanks to the cheers that echoed all out of proportion to their actual heft. Too bad. This was the fifth ballpark I visited and I immediately decided it was No. 5 among my favorites. That pattern continued right up to the Expos’ death. At this writing, I’ve been to 30 ballparks and Le Stade Olympique is secure at No. 30 — until the 31st park gets visited. Tropicana Field or the Metrodome, long buried on my to-do list, will have to be awfully awful to undercut it.

But I’m not recollecting here to be mean to Montreal. I had a nice time. And if I had a nice time, I’m pretty sure my friend did, too. First off, the Mets took a 4-0 lead by the third and won easily, 7-3. Terry Leach, who was a godsend that season by filling in for all our injured starters, went eight innings for the victory. He was 5-0 at the end of the night. What a bon lanceur he was. I squinted down to the end of the Mets’ long dugout bench to pick out Tom Seaver who was on the comeback trail (it never took; he retired the following week) and may have seen him.

I know I saw No. 25 in the lineup, batting second and playing second. It wasn’t Backman and it wasn’t Teufel. It was Keith Miller, making his Major League debut right there in Montreal with me on hand. Because of that, I always felt proprietary of his career which didn’t amount to much, sad to say (at least before taking up agenting), but he did hustle. In the private baseball lingo another friend and I occasionally chatted in for fun, Stephanie became known as Keith Miller for coming out of nowhere and providing a spark to my life; I was Darryl Strawberry mostly ’cause I wanted to be.

Mets caps dotted the O. I was wearing one plus a Giants Big Blue Wrecking Crew sweatshirt, trying to stretch that City of Champions vibe a little longer (the Mets and Giants would both defend titles ineptly in 1987). Ran into a fellow in the men’s room who was also up from the Metropolitan area, also liked the Mets and Giants. We chatted briefly about both teams and concluded that we had had it pretty good lately in New York.

That was the only game we went to, at least the only Mets-Expos game. My friend and I walked along Rue Ste. Catherine, past the various Smoked Meat signs, and found a park near McGill University the next afternoon where we played Wiffle Ball. We’d had a Wiffle Ball game in progress since November ’85, my first post-college visit to Tampa. We played a few innings in the Albertson’s parking lot then and picked it up every time I came down. I don’t think we did much Wiffle Ball in New York, but made up for it with three innings in the park that day. We concluded the game the following March on the main baseball diamond at USF when I came down for Stephanie’s spring break. I seem to recall the final collective score winding up 43-33 in my favor, but I could be making that up.

We left Montreal Thursday morning, initially following the same path we took, back through Vermont. We got to the border, me driving this time. The United States guard wasn’t smiling when he asked what we were up to. I smiled and said we’d gone to Montreal to see the Mets play the Expos.

He looked us over. Young guys. Florida plates that I still hadn’t switched to New York. Hadn’t shaved. My friend was wearing one of his trademark Hawaiian shirts. Miami Vice was still on the air.

“Please get out of the car.”

The border guard decided were drug smugglers. He didn’t say it, but that was the strong impression he gave. He searched the car, searched our luggage, searched our pockets. He got excited twice, once when he found an empty baggy in my suitcase, once when he found pills in aluminum foil in my jeans. He actually cracked the foil open. Tylenol, I said. I get headaches.

He let us go.

The rest of the trip was uneventful except for me being pulled over for speeding on the Massachusetts Turnpike. I was doing 77 in a 55 zone. Gosh, that makes me smile today. The Mets salvaged a series split while we were in Connecticut. The next day, I drove my friend to Newark Airport (in record time from Long Island, I might add) and he hooked up with his parents. I turned around and went home.

That was it for me and Montreal and for me and grand, unplanned ROAD TRIP!s. I would have assumed this was the sort of thing I’d do from time to time for the rest of my life, but no, that was the only truly impulsive one I ever took off on. As for me and my friend, it was kind of a final flourish for our post-college friendship at least on the scale it existed in the mid-’80s. He and Stephanie’s roommate got back together in Florida and actually beat us to punch marriagewise (neither of them being sticklers about bothering to graduate). We all kind of stayed in touch, on and off, for several years thereafter. For reasons I don’t quite grasp, they and their daughter, born in December 1989, fell off our radar for good in 1996 and us off theirs. Wouldn’t have guessed that could possibly happen in June 1987, but it did.

The Mets arrived home from Montreal as well. They swept a weekend series at Shea from the Phillies in what was judged to be a great pivotal turning point to that frustrating season. No record exists on which player spit on which fans in real life.

by Greg Prince on 4 March 2010 7:21 pm Jason Bay once was Lost. But now he’s Found. A four-year contract has saved a wretch like him.

No offense to JB (does he have a nickname yet?). I just can’t help but notice that unless he falls victim to Prevention & Recovery between now and April 5, he will become the 13th verifiable member of the Lost Boys Found Society: Met minor leaguers who had to leave home to make the majors, yet somehow discovered the Amazin’ grace to make it all the way back home to become real, live New York Mets.

You probably know that in the summer of 2002, as general manager Steve Phillips struggled with his twin addictions (sex and the mindless dispatching of useful outfielders), Jason Bay was traded by the Mets to the San Diego Padres. The Mets’ big prize in that deal was middle reliever Steve Reed, who Phillips just had to have to shore up the ’02 Wild Card drive…you know, the one that ended in a ditch filled with bong water and regret. Bay’s big prize was the Rookie of the Year award he earned with the Pirates in 2004. Yes, San Diego was dopey enough to let him go, same as us, same as Omar Minaya’s Montreal Expos before us. The Mets were not alone in misunderestimating Jason Bay.

But that doesn’t make Steve Phillips a visionary for telling a future three-time All-Star to get Lost.

Steve Reed’s unforgettable contributions to a non-playoff hunt notwithstanding (to be fair, Reed was pretty decent in his 24 Met appearances, no matter that the last 20 or so came after the Mets fell out of contention), how must have Jason Bay felt? There he was, a Binghamton Met, batting .290, walking teenaged Jose Reyes from the hotel to the ballpark, close enough to Shea to dream…and then?

Boom — he’s a Padre.

We’re Mets fans. Who among us hasn’t dreamed of becoming a Met at some point in our lives? Imagine if it was you. You’re a Met minor leaguer, your lifelong goal of playing for the Mets appears within reach, and then it’s snatched away because Steve Phillips was presumably too busy indulging his extramarital libido to dissect scouting reports. Granted, Jason Bay may not have grown up a Mets fan in British Columbia, but we don’t take that into account. In our lives, being a Met is the highest calling there is. When he was sent to San Diego, then Pittsburgh, then Boston, Bay’s call seemed forever put on hold.

Now he’s been called back. An expensive call, but one for which we’ve accepted the charges. Come April 5, Jason Bay’s destiny gets back on track. He was a Lost Boy in those other uniforms. He’s Found himself a Met.

It’s happened before. It’s happened, as far as I can reckon, a dozen times. A Met minor leaguer has to leave the Met organization to become a major leaguer but then, somehow, he receives a reprieve and becomes a Met. With the help of my friends at the Crane Pool Forum, I’ve counted twelve different Lost Boys Who Found Themselves. Like Jason Bay, they appeared consigned to the wilderness of playing only for opposition. But circumstances led them, at last, to Queens and earned them the fruits of true Metdom:

• a listing on Ultimate Mets Database;

• a notation in Mets By The Numbers;

• a card in The Holy Books.

Surely they are thrilled.

Let’s get to know those Mets who blazed the path Jason Bay will follow when he becomes the first Lost Boy to Find himself at Citi Field.

The earliest known example of a Lost Boy Found is Jerry Morales, a 1966 signee who was Metnapped by the pesky Padres in the 1968 expansion draft. Poor kid didn’t even have time to rise beyond Single-A when he was taken. Alas, Morales became a big leaguer in San Diego in ’69, gave the Cubs several solid seasons in the mid-’70s (earning a 1977 All-Star berth) and made his way back to where it should have all started, Shea Stadium, in 1980. He came “home” from Detroit, in the company of the severely mortal Phil Mankowski, in a trade that was a winner for the Mets, because they pawned off on the Tigers one Richie Hebner. If the Mets couldn’t have sent their Sixth–Circle Mets Hellion to Motown, they would have had to have shipped him to Love Canal. That was where toxic waste went back then. Morales did essentially nothing in his one-year Met tenure. Mankowski was actually harmful to ground balls. And I still say it was a great trade. Anything that rids the environment of Richie Hebner is a good thing.

The ’80s progressed with no more Lost Boy action until Lou Thornton came around to score at the end of the decade. Thornton was a 19th-round choice in the same 1981 draft that saw the Mets select Terry Blocker in the first round, Lenny Dykstra in the thirteenth, Roger Clemens (yup) in the twelfth and Steve Phillips (double yup) in the fifth. Lou’s future career as a Met pinch-runner was derailed when the Blue Jays plucked him in the 1984 Rule 5 draft. That meant they had to keep him on the big club, which wasn’t so bad for Lou, because he got to pinch-run his way onto Toronto’s playoff roster. Lou pinch-ran twice in the ’85 ALCS, which the Jays lost. Serving again as a pinch-runner, he scored the winning run in a huge Toronto victory over Detroit down the stretch in ’87, right before the Blue Jays reverted to Blow Jays form and blew the A.L. East to the Tigers. The Mets picked him up from the Pirates in the middle of 1989, and he was on the roster in September, scoring another winning pinch-run in a pennant race showdown, at Shea against the Cubs. Once again, however, Thornton’s speed was for naught as the Mets, like the Jays, did not win on the wings of Sweet Lou’s wheels. He’d be lost to the Met mists of time by 1990.

Bill Murray used to do a very funny bit on Weekend Update in which, as film critic in residence, he’d go through the Oscar nominees and dismiss several Best Picture candidates because “I didn’t see it.” Bill Murray meet Mickey Weston, a righthanded hurler Mets fans saw only four times. Better yet, Dave Murray, meet Mickey Weston. Our Mets Guy In Michigan blolleague has a nice story about meeting the pitcher and becoming his “personal biographer”. I have no story about Flint-native Weston, a Mets’ draft choice in 1982 who wrapped in the same bounty that yielded us Dwight Gooden, Roger McDowell, Steve Springer (Dave and I share him) and — had we signed him — Rafael Palmeiro. Seven years beating the Met bushes got Weston no further than Tidewater. He left as a minor league free agent and ultimately made the show with the ’89 Orioles. He rematerialized as a Met in 1993, which made him a 1993 Met, which is guilt by association, but Dave seems to think he’s all right, so we’ll give him a pass.

There was Leon “Goose” Goslin. There was Rich “Goose” Gossage. It was inevitable, then, that Mauro Gozzo‘s nickname would be avian in nature even if he wouldn’t make it three Geese in the Hall of Fame. This Goose’s professional career took flight as a Met draft pick in 1984. The righty’s tour from Little Falls to Columbia to Lynchburg was rerouted in the spring of ’87 when he was a throw-in (and have you ever tried to throw a goose?) in what the Royals hoped would be the Ed Hearn trade but turned out, thankfully, to be the David Cone trade. Goose flocked to the Blue Jays for his 1989 big league debut and later landed briefly in Cleveland and Minnesota. By ’93, he was a Norfolk Tide and, as was often the case with the Tides of ’93, a full-fledged Met. After 1994, however, Gozzo was gonzo.

Fernando Viña was another Rule 5 (or is that Rule V?) loss by the Mets. The Mets signed him in 1990, lost him in 1992, watched from afar as he made his debut as a Mariner in 1993…but got him back before that benighted campaign completed. While Seattle built the foundation of the Refuse to Lose A.L. West champs, Fernando continued to attempt to get his Met on in Norfolk. He impressed in camp in ’94 and at last answered his Met calling, primarily backing up Jeff Kent and Bobby Bonilla, two of the most popular Flushingites of the era. While players and owners engaged in mutually assured labor-management destruction that December, the Mets shipped Viña to Milwaukee for Doug Henry. Doug Henry, like Jeff Kent, had two first names. Fernando Viña, like Jeff Kent, went on to greater things as an ex-Met, including two Gold Gloves, one All-Star appearance, a gig on Baseball Tonight and a supporting role in the Mitchell Report.

How good were the 2000 Mets? They were so good that they made the World Series despite misguidedly deploying Rich Rodriguez in 32 separate games. It was likely the stopping of using Rich Rodriguez that catapulted them to the pennant. Rodriguez’s route to Metdom began as a 1984 ninth-round draft pick. His left arm got as far as Double-A Jackson in ’88 before it was dealt to the Padres for the proverbial bag of balls. Next thing you know, ol’ Rich is a lefthanded specialist for four different major league clubs across the ’90s. His specialty turned not so special when he returned to the Mets in 2000 and allowed as many batters to become baserunners as humanly possible. The fans took note. Before Game Three of the NLDS, the Mets did the classy thing and introduced their non-roster players, the guys who came up or back in September but wouldn’t be used in the postseason. Only one of them was booed by the discerning Shea faithful. That was Rich Rodriguez and his 7.78 ERA. Yes, the Mets did the classy thing, but also the smart thing by not letting him do anything more that October than glumly tip his cap. Steve Phillips let him go after 2000, clearing much-needed space for his next lefty specialist find, Tom Martin (2001 ERA: 10.06).

In seven minor league seasons from 1990 through 1996 — encompassing stints with Gulf Coast, Kingsport, Pittsfield, Capital City, St Lucie, Binghamton and Norfolk — the closest first baseman Brian Daubach got to New York was 1995, when the Mets were featuring at Thomas J. White Stadium anybody who didn’t mind being labeled a replacement player. Future Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor made that particularly embarrassing baseball spring moot when she told the clubs to cut that stuff out, and Daubach’s first chance to be a Met of any kind went by the wayside. He emerged as a 1998 Marlin, then as a pretty solid Red Sock for a few years after that. In a 2000 Interleague series, Daubach overcame Todd Pratt’s calling him a “scab” and homered off Mike Hampton to beat the Mets at Fenway. Five years later, Daubach wasn’t quite as solid and found himself again in Norfolk. That June, he was called up to replace a disabled Miguel Cairo. Fifteen mushy games later, he’d find himself replaced by a reinstated Doug Mientkiewicz.

Perhaps we’ll one day think of Jason Bay as an all-time Met. The first seven Lost Boys Found don’t really strike us that way, do they? But the eighth man to leave the Met minors, make the majors as something less desirable and the finally become a Met in toto…he’s pretty damn all-time. He’s Endy Chavez. We know who he became as a Met. Why was he allowed to become a major leaguer somewhere else? He spent four years in our minor leagues, cresting in high A (batting .298, stealing 38 bases) in 2000 and attracting the attention of the Royals’ front office, if not genius Steve Phillips. Kansas City took him as Rule V (or 5) selection. They tried to give him back to the Mets at the end of Spring Training, but Phillips brilliantly said, no, that’s all right, you keep him, why would the Mets ever need an Endy Chavez? Endy would be a nondescript Royal, then a promising Expo — torching the Mets a lot — before GM Omar Minaya grabbed him in advance of 2006. Endy did the grabbing from there, as we all know.

An ordinary infield prospect for the Mets became an effective relief pitcher for the Expos and, a couple of years after that, a villain to Mets fans. Such was the sojourn of Guillermo Mota, an early ’90s Met minor league shortstop/third baseman who had to find a whole other position to make it relatively big. Mota’s mistake as a pitcher was throwing too close to Mike Piazza in consecutive Spring Trainings, 2002 and 2003 incurring the big man’s — and our — wrath. The feud culminated when Piazza entered the Dodger clubhouse looking to settle the score. Wow, did we ever hate Guillermo Mota. Then, in the summer of 2006, as Omar Minaya groped around to fill the gap left behind by the Midnight Ride of Duaner Sanchez, he picked up a struggling Guillermo Mota. Given no choice, we reluctantly cheered on our new and not so bad righty reliever, until he contributed to our losing the NLCS, tested positive for a banned substance and sucked out loud through 2007. He was little good for us in the long run, but at least Mota left us feeling validated about despising him in the first place.

Being an Original Cyclone didn’t help Angel Pagan make the majors as a Met. The onetime Brooklynite (as well as Kingsporter, Capital Citizen and so on) climbed the Met minor league ladder for six seasons, only to be knocked off short of the big leagues. He landed as a part-time Cub in 2006, but then alit at Shea at last in early 2008. Pagan was greeted warmly — anybody remember the flapping Angel wings that April? — if briefly. A torn labrum grounded Angel in May, and he battled bad health luck as almost every Met would in 2009. Finally, he mended while so many of his teammates’ seasons ended. Pagan would run the wrong way a lot when given the chance, but he also hit pretty well at times. He now gets another opportunity to impress…alongside his Lost Boy soulmate, Jason Bay.

If anyone seemed destined to become a Met, it was Nelson Figueroa. He grew up rooting for them in Brooklyn, he was drafted by them out of Brandeis, he had pitched his way to Binghamton…and then, in 1998, it was off to Arizona in what was either the Bernard Gilkey deal or the Willie Blair deal. The deal for Figueroa was a lot more traveling by the time he got to Phoenix in 2000. He went to Philly (for Curt Schilling) and then three more organizations. Figgy missed an entire season due to rotator cuff surgery and wandered his way from town to town, up and down the dial. Eventually, the town that welcomed the righty home was New York, New York. He made his long-delayed debut as a Met starter in April 2008, on a foggy night when his entire family and everybody they ever knew packed a Shea DiamondView suite to cheer him to victory. There have been ups and downs since — sniping at the Nationals for acting like “softball girls” when he couldn’t get them out was rather inane — but when you scan the practice fields of Port St. Lucie, you’ll see Nelson Figueroa, still working to make his destiny permanent.

Raul Casanova…talk about a Lost Boy. Drafted by the Mets in 1990 (same June as Viña — and Daubach). Traded to the Padres for Tony Fernandez in 1992. A major league catcher for the first time as a Tiger in 1996. Professional relationships between 1999 and 2007 with the Rockies, the Brewers, the Orioles, the Devil Rays, the Orioles again, the Red Sox, the Royals, the White Sox, the Athletics, the Devil Rays again. Then, in April 2008, directly on the heels of Pagan and Figueroa, he became a Met at last. It only took him 18 years. And he only lasted 20 games. Still, better Found late than to remain Lost forever.

And now, it is time for Jason Bay to Find himself with the Mets.

by Jason Fry on 3 March 2010 2:39 pm If the 2010 Mets get off to a bad start on the field or once again demonstrate that they’re incompetent and/or tone-deaf about treating injuries, building ballclubs or relating to fans, we’re going to get typecast. We’ll be fans of the Big Team That Can’t, the grizzled, paranoid saps who trudge around accompanied by our own personal blue-and-orange storm clouds, anvils suspended by frayed strings above our much-abused noggins. And there will be some truth to it.

This thought crept into unhappy view yesterday, at the beginning of what should have been a gleeful couple of hours. At 1 p.m. sharp I made my way from the office to the bedroom (I’m not sure but I may have even skipped), turned on the TV, and told the Cartoon Network its winter of animated hegemony was now over. There was SNY, and Gary, Keith and Ron, and green grass and baseball and Mets.

All good. All wonderful, in fact. But then came that moment.

Nelson Figueroa is on the mound, backed by scrubs and kids and retreads. There have been a bunch of scratches from the regular lineup. There is nothing to play for.

We were, I realized, pretty much exactly where I last saw the New York Mets getting statistics recorded for playing baseball. Was there any way this immediate reminder of 2009 could that possibly be good luck?

And then the moment passed, and I was able to sink gratefully into the old routine, by now so familiar that it’s practically muscle memory. There were some old Mets and some new Mets and some ex-Mets and some impossibly young Mets. There was a sideline interview with Jose Reyes, who looked cheerful enough giving Kevin Burkhardt vaguely considered answers beneath various objects perched on his head, like the tops of out-of-order Russian dolls. There was big Ike Davis, who got two hits and muffed a somewhat-tricky pop fly, providing us with three opportunities to overreact in various ways to March doings. There was the inevitable terrifying new Braves prospect, one Jason Heyward, to admire and then worry about. There were lousy calls and a minor injury to a not terribly important player and Keith talking about his dog and finally a Mets win, which I had long since stopped paying very much attention to.

During the winter it always seems faintly crazy that this could happen. Are you there, God? It’s me, Jason. If You’d only give me a spring-training game, I’d spend three hours watching it with laser-beam intensity and then be a better person. Thanks. Oh yeah, and amen. But it is always like this: By the 20th minute of the first Grapefruit League game I’ve got half an eye on the game and half an eye on something else, and am thoroughly used to having baseball back.

We talk about baseball fever a lot. But maybe we’ve been misdiagnosing it all these years. Because, honestly, doesn’t baseball fever come in the winter? That’s when I’m irritable (OK, more irritable than usual) and fidgety and can’t shake the feeling that the world is deplorably out of kilter. When baseball does return, within 20 minutes I relax and feel well again. Baseball fever — endure it.

* * *

I’m with Greg in giving the Mets kudos of a minor sort for finally admitting what we’ve all been complaining about for nearly a year: There are outfield seats in Citi Field from which you can’t see one and sometimes two outfielders, and now you’ll at least know it when you go to buy a ticket. If the Mets want me to shut up about this they should also discount those tickets — perhaps they should cost 7.5/9 of a ticket with full views? — but yes, it’s progress. I’ll also join my partner with a tip of the cap to the ever-vigilant Mets Police for walking this beat on behalf of fans.

by Greg Prince on 3 March 2010 8:26 am Truth in advertising creeps into Metspeak, according to the Times‘ Bats blog:

Mets fans had a tough time feeling comfortable in Citi Field ast season, mainly because the team performed so poorly. But some fans were also irked that they could not see parts of the field from their seats, especially in left field.

In the third deck there, for instance, fans often cannot see the left fielder, and occasionally the center fielder drops out of view.

Mets executives said the obscured views were the trade-off for putting fans closer to the action in Citi Field, which is cozier than Shea Stadium. That explanation did not placate some people who felt the team should have affixed warnings to the tickets.

The Mets appear to be correcting that lapse. When ordering tickets for certain seats online, fans receive a warning that reads, “View: Limited portions of the playing field may not be visible from this seat location.” The disclaimer, in bright orange, was attached to seats in 300, 400 and 500 level seats in left field.

Don’t be fooled by the Times‘ subtlety, for, in the context of Citi Field’s growing pains, this is worthy of screaming Post hyperbole. It’s really quite substantial: an acknowledgment by the typically admit-nothing Mets that what they’re selling isn’t close to perfect, even if took them a year to nod toward the reality that everyone else discovered upon trying to take in the entire outfield from any given seat in Promenade. I assumed the Mets would instead dig their heels in deeper and insist that these were actually the best tickets you could purchase; my wife came up with a fantastically Metsian term for the areas from which you couldn’t clearly make out the left fielder: Vantage Point Seating. We expected to receive a brochure hyping it as New For 2010.

Admitting imperfection in bright orange represents a sea change — or Bay change, since we’re talking left — from deny, deny, deny, as Dave Howard did last April on WFAN when he was asked to respond to the rising tide of complaints from ticket buyers who could not see all for which they had paid (transcript courtesy of Mets Today):

“Here is the issue, this is with regard to seating in fair territory in the outfield, which is something different that we have at Citi Field, that we really did not have much of at Shea Stadium. … the reality is … a little seating we had in fair territory in the outfield at Shea Stadium did have some blind spots on the field, it is NOT obstructed. The way we characterize “obstructed” is if you have an obstruction, something in front of you — a beam, a pillar, something that’s blocking your view. That’s not the case here. It is a function of the geometry of the building. And it is a conscious decision that we made along with the designers and the architects, that we wanted people to be lower and closer to the field, and have great views, and great views of the action. By doing that in fair territory, you are going to have situations where you are going to lose certain blind spots in the deep outfield of those sections. That is something we understood to be a factor. It is true in every new ballpark that has seating in the outfield …”

I barely passed ninth-grade geometry, yet I think if there had been a question on the Regents Exam about something blocking my view, I probably would have chosen “obstruction” over “blind spot” if the question was multiple-choice…and, in the “show your work portion,” I wouldn’t have tried to explain how not being able to follow the track of the ball or the fielder(s) chasing it is an asset at a baseball game (even a 2009 Mets baseball game). I’m still confused over how seeing less of the action was supposed to give me “great views” of the action. But again, geometry was never my strong suit.

The “conscious” decision to build a baseball stadium in which significant swaths of the baseball game would not be readily visible to a critical mass of baseball fans would be tough to square with the logic statements inherent in geometry. Rebuilding is something the Mets do clumsily when it comes to their roster, so I guess it’s not surprising that building a grandstand (and a case for its drawbacks) would befuddle them. At the very least, they can label the tickets with a proper warning. And they’ve done that.

They’ve done the very least.

Blue Cap tip to Mets Police for being on this well ahead of the Times. If there’s a Paper of Record for recording Mets fan indignities, surely it’s MP.

by Greg Prince on 2 March 2010 2:08 am Continuing the recent theme of leaning forward into the schedule of meaningless exhibitions until we are so close to Tradition Field that we’ll be called out for fan’s interference, there’s a game today.

Today has a game. A baseball game. A Mets game.

It’s Today’s Game.

Today’s Game is scheduled to start at 1:10.

Today’s Game will air on SNY.

Pitching in Today’s Game will be whoever. Same for the catcher. Same for the batting order.

Whoever, whatever…we’re not picky. We’re starving. We’ll be sated by Today’s Game. Just the thought of Today’s Game fills us up.

Today has a game. A baseball game. A Mets game.

Can’t wait for Today’s Game.

So what else is new?

by Jason Fry on 1 March 2010 9:33 am  The building that contains the Fry manse has had a tough winter. First the heat was kaput for several days. Now, following the season’s 242nd blizzard, the roof is leaking. Through a quirk of intrabuilding geography that I find less than delightful, the water’s chosen route was to descend three floors and pool atop our bathroom ceiling. Cue a leak and, after two days of soaked sheetrock, the inevitable. Which came at 4:15 a.m., as these things do. The building that contains the Fry manse has had a tough winter. First the heat was kaput for several days. Now, following the season’s 242nd blizzard, the roof is leaking. Through a quirk of intrabuilding geography that I find less than delightful, the water’s chosen route was to descend three floors and pool atop our bathroom ceiling. Cue a leak and, after two days of soaked sheetrock, the inevitable. Which came at 4:15 a.m., as these things do.

WHAM!

Emily (groggily): What the hell was that?

Me: I’m gonna assume the bathroom ceiling.

Correct. Which at the time seemed like a good thing: The water had eliminated that pesky sheetrock from its path, we had a bucket, etc. But no. Now the water is descending an additional floor and pooling atop our downstairs bathroom ceiling.

Being a Mets fan here is somewhat helpful in making predictions: The upstairs bathroom ceiling is done collapsing; the downstairs ceiling is up 3 1/2 with 17 games to play.

And yet, as I sit here in the bowels of my snowbound, falling-apart house, I’m … happy.

And why is that? Because tomorrow the Mets play the Braves, and things like 1:10 and 7:10 and Ws and Ls and SNY return to my lexicon. It’ll just be a small step closer to spring, but it’ll feel like a giant leap. And while ceilings may still be falling, I’ll no longer feel like the sky is, too. Hang in there, everybody. We’ve almost made it.

by Greg Prince on 28 February 2010 5:33 am The Department of Sudden Realization is reporting the New York Mets will play the Atlanta Braves in two days. Well, it’ll essentially be random fellows wearing Mets uniforms versus unknown guys wearing Braves uniforms after the third or so inning, and it won’t count in any serious standings, and the outcome will be forgotten minutes after it is registered.

But the New York Mets will play the Atlanta Braves in two days.

Professional baseball players under contract to our favorite team will pitch against and hit against and maybe even field against professional baseball players under contract to another recognizably branded organization. People will pay money to sit inside a stadium and witness it. A score will be kept and displayed. Shouts of encouragement and bites of frankfurters and purchases of programs…all those pleasing signs of spring will, for the first time in an eternity, be sprung.

Baseball! It’s February 28, it’s freezing, half the world remains snow-encrusted, yet in two days, there will be baseball. New York Mets baseball is coming to a life near you.

We can start living ours again any hour now.

Billy Heller of the New York Post says Faith and Fear in Flushing: An Intense Personal History of the New York Mets — available soon in paperback, with a brand new epilogue exploring the first season of Citi Field — is Required Reading. Read all about it here.

by Greg Prince on 26 February 2010 7:59 pm On October 28, 1961, eight dignitaries in suits — including Mayor Bob Wagner, master builder Bob Moses and future villain Don Grant — plunged spades into the ground and touched off the beginning of construction on a project tentatively titled Flushing Meadow(s) Stadium. It took 902 days to get from ceremonial shovels to the first official pitch thrown on that site, one fired by Jack Fisher of the New York Mets to Ducky Schofield of the Pittsburgh Pirates. By then, April 17, 1964, the structure in question would be called Shea Stadium…and the pitch from Fisher would be called a strike by home plate umpire Tom Gorman.

On September 28, 2008, Ryan Church would lift a deep fly ball to centerfield in the same place. Deep, but not deep enough. Cameron Maybin caught it and, in essence, ended the life of the stadium. A ballpark can’t be a ballpark unless it’s got some ball in it, and dratted Maybin made off with the last one. Nevertheless, Shea stuck around after the final out, first for another ceremony — one in which Fisher, followed by 42 other former Mets, would bid adieu to the stadium’s last assemblage — and then for the gruesome business of the building’s disassembly.

Breeze Demolition, a subcontractor from Red Hook, dug its hooks into Shea Stadium within hours of Fisher’s fond farewell. It took 143 days to pull apart what required 902 days to put together. For those of us who couldn’t help but monitor its methodical deconstruction, it seemed like it took forever for Shea to come down, yet in actuality, erasing it took less than one-sixth the time it took to create it.

The disappearance of Shea from the New York cityscape, save for the dust and debris that would linger into May, was completed just over a year ago, when on the morning of February 18, 2009, the last immediately discernible sign of its existence vanished from the Queens skyline. Save for four brass bases and an accurately if curiously named pitcher’s plate in a parking lot, it’s now like Shea Stadium was never there. The disappearance of Shea from the New York cityscape, save for the dust and debris that would linger into May, was completed just over a year ago, when on the morning of February 18, 2009, the last immediately discernible sign of its existence vanished from the Queens skyline. Save for four brass bases and an accurately if curiously named pitcher’s plate in a parking lot, it’s now like Shea Stadium was never there.

Shea, of course, lives on anyway. It lives on in our memories, our souls, our imaginations and our Mets fan DNA. It also, thankfully, continues to exist in print, most notably in the pages of several recent and terrific books. One of them — Bottom of the Ninth by Michael Shapiro — tells thoroughly if almost incidentally of Shea’s conception as part of a larger story of baseball’s late ’50s and early ’60s evolution. Two others whose reach is closer to home — Dana Brand’s The Last Days of Shea and Shea Good-Bye by Keith Hernandez and Matthew Silverman — offer loving encomia crafted on the eve of the park’s passing. Each of them is a worthy companion to the way you remember Shea, whether from its beginning, its middle or its end.

I’ve only recently gotten automatically used to the idea that there is no longer a Shea Stadium. No wonder: 2010 is the first calendar year in 50 during which there has been no immediately discernible sign of Shea Stadium. Still, the slow realization that it’s not around and that it’s not coming back goes beyond the longevity of an entity that began to stir in 1961 and ceased to exist in 2009. It goes beyond what Brand’s textured eloquence or Shapiro’s fresh history or Silverman’s expert editing of Hernandez’s occasionally random recollections can capture, too. It’s gets to the simple fact that Shea Stadium was my idea of what a ballpark was. It couldn’t help but be. It was my first ballpark.

It was my first park on TV. It was my first park in person. It was the park that defined what it meant to watch baseball for me. Shea shaded my view of every other park I’d ever visit, particularly the one I now technically call home.

I’ve been lucky enough to have attended Major League Baseball games in 34 different parks, 10 of which, like Shea, have either left the face of the earth or have stopped functioning in the MLB realm. On some level, that means I’ve been to…

• Shea Stadium;

• 9 parks that weren’t Shea Stadium;

• and 24 parks that are not Shea Stadium.

It won’t surprise you a bit that Shea defines my perspective on ballparks. It may surprise you, however, to learn I don’t consider Shea my favorite ballpark. Most beloved and most resonant to me, absolutely. But there are some I hold in what I guess you’d call higher esteem.

Oh, there’s none I hold as dear as Shea, but I’ve got the ability to delineate. I know when I’ve been somewhere that’s…I don’t know if “better” is the word I would use here, but I’ve been to parks that transcended Shea for me — which is no small feat. That’s the litmus test I wound up applying once I began visiting other parks and ranking them. If I really felt that, all things being equal (though all things rarely are), I was having a Shea-plus time at a ballgame elsewhere, I had to be honest with myself. I had to say, y’know what? I have to rank this place ahead of Shea.

Not many ballparks made it over that hurdle. The uninitiated — anybody’s who’s not a Mets fan, probably — would not get that. But I imagine most of you who are Mets fans do.

Over the next several months, I plan to devote Flashback Friday to ballpark talk in a series ambitiously dubbed Take Me Out to 34 Ballparks. Starting Friday, March 5, I will revisit my 34th-favorite ballpark. The week after, we’ll go to my 33rd-favorite ballpark. Then…well, you get the idea. It’s a countdown because I like to count things down, but it’s less about my immensely subjective rankings than a chance for me to explore with you what these places mean to us as baseball fans.

It’s also an attempt on my part to place Citi Field in some kind of context besides it not being what Pedro Martinez memorably called my beloved Shea. With Shea Stadium off the map, I hope to begin to view Citi Field apart from the ghost hovering over its third base shoulder. Figuring out where it stands for me is an unfinished assignment. Take Me Out to 34 Ballparks might provide me with some guidance.

I tend to rank my ballparks as soon as I see them. Most of them I’ve seen only once, and I know I’ll likely never see again. Citi Field is different in that respect. I didn’t rank it right away. In fact, I kept it unranked until I’d finished a full season there, and even now I view its status as provisional. I have a hunch Citi Field will always be a work in progress for me, which is fine. Shea was always going to be the static standard by which I measured every other ballpark. Citi’s place in my head (and maybe, eventually, my heart) can’t help but be more dynamic. My thoughts on it will be more subject to change than the other 33 parks combined.

But it does have a ranking, so it will show up where it shows up — same for Shea, same for the other 32 where I’ve been fortunate enough to experience big league baseball.

I like some parks more than I like other parks. It’s no secret that I like Shea more than I like Citi. But (again with all things being equal) I’d take being in a ballpark — any ballpark — over being anywhere else just about any day. So I’m pretty excited about going to one every Friday for the next 34 Fridays.

I hope you’ll find it a worthwhile trip.

Unless you’re soaking up the pleasures of practice fields in Florida or Arizona this weekend, consider spending an inning of more at the 24 Hour Talk-a-Thon to benefit Operation Homefront, a joint production of Baseball Digest, FantasyPros911.com and BlogTalkRadio.com. Details on this impressive undertaking for a worthy cause here.

by Greg Prince on 24 February 2010 7:47 pm Pity Mike Francesa. He’s a very insecure man. Today he interviewed James Hirsch, the author of the wonderful Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend, and turned the conversation as well as the remainder of his show into a referendum (with his vote the only one that counts) on Mickey Mantle being better or more clutch or more forthcoming or a nicer person than Willie Mays. Even in begrudgingly acknowledging Mays’ unsurpassed all-around greatness, Francesa had to keep injecting Mantle, Mantle and more Mantle into the program.

I found this fascinating, not for the content, but for what it reveals yet again about Francesa, New York’s most listened-to sports talk host and highest-profile über Yankees fan. He couldn’t stand the idea that his childhood idol Mantle wasn’t being celebrated. The book, mind you, covers Mays’ entire life and career. It’s not a comparison of centerfielders at whom New Yorkers and baseball fans were fortunate enough to marvel during the same era. Mantle is not disrespected in this book. He’s just one character in a sweeping biography. Hirsch wrote about Mays, not Mantle. There are plenty of books about Mantle. This simply isn’t one of them.

Not good enough for Francesa, who immediately told Hirsch — because it mattered to Francesa — that he’s “pro-Mickey Mantle” and, therefore, “anti-Willie Mays”.

This is a delineation a six-year-old makes.

It also fits the pattern of Francesa endlessly dismissing the Mets, the Jets and just about anything that isn’t the Yankees or that he can’t somehow connect to the Yankees. The football Giants, since they used to play in Yankee Stadium (and employ a coach who once served under his onetime BFF Bill Parcells), seem exempt from such condescension. I noticed on his performance art showcase that aired on Channel 4 the Sunday night after the Jets clinched their playoff spot that Francesa had to lead with an observation on how badly the Giants had played that afternoon, but we’ll get to them later…oh yeah, the Jets made the playoffs.

This was obviously the fault of the Jets for rhyming with Mets, which automatically devalues them to Francesa, the six-year-old who can’t stand attention being paid to anything that doesn’t smack of pinstripes.

Willie Mays? An all-time great? The subject of a new book, which is why you have on the guest you have on? So what? WAAAH! I WANNA TALK ABOUT MICKEY MANTLE! HE WAS MY FAVORITE PLAYER WHEN I WAS LITTLE! Reminded me of another misguided listening adventure many years ago when I tuned in to hear Francesa and his erstwhile brain-free partner speak to actor and Mets fan Tim Robbins. First thing Francesa said to Robbins was, hey, we should get you together with Chazz Palminteri, he’s an actor and a big Yankees fan!

Robbins was too polite to ask what I would have in that situation:

“What the fuck does Chazz Palminteri have to do with me at this moment?”

I don’t recall the impetus for Tim Robbins appearing, but I do know it wasn’t Subway Series Smack Talk or anything like that. Alas, Robbins was a Mets fan, and that couldn’t be taken at face value. Francesa had to make it about the Yankees, because that’s what a preternaturally insecure, hopelessly childish Yankees fan does.

Perhaps you’ve encountered examples of such behavior in your own life, off the air.

I have a hunch Mike Silva’s interview with Hirsch this Sunday evening at 9:00 on NY Baseball Digest will be far more focused on the subject matter at hand.

by Jason Fry on 23 February 2010 9:18 pm Ignore, this will be gone soon.

PEN4EN22868X

|

|