The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 14 October 2023 1:20 pm “The moon belongs to everyone,” a wise man once informed a hallucinating man, though the subject could have been the playoffs, and that would have been wise, too. They’re here for all of us every October that isn’t October 1994, even if the best things in life include the Mets playing in them, and that’s not going on this October.

Rare treats being what they are, the Mets’ playoff involvement doesn’t go on most Octobers, so a Mets fan oughta be practiced at this type of adjustment. A Mets fan watches two non-Mets teams and picks a side, sometimes consciously, sometimes just pulled in one direction or another by the moment. You didn’t have to be a Mets fan to enjoy the National League Division Series elimination of the Braves. That belonged to everyone. For anyone reflexively pointing out that at least the Braves made the playoffs, nah. It’s too late for those who advocate on behalf of an ousted playoff team to take out their frustrations on the snickering peanut gallery far removed from the action. You’re on the big stage, you stumbled, we get to guffaw. The best things in life are free.

Enjoying Atlanta’s exit from the postseason necessarily meant being in favor of Philadelphia’s advancement therein, which is akin to a person beset by nut allergies digging into a tin marked Planters. Except it’s October, and we can be inoculated against the usual impact of our chronic allergens if we wish. We just have to forget how much we can’t stand one half of a postseason series’s participants, either because we are smitten by a fleeting storyline or we really can’t stand the other half of that postseason series’s participants. For Phillies-Braves, we had a practice round. We had Phillies-Marlins. The Phillies — who we can’t stand for getting in our face — eliminated the Marlins — who we can’t stand more for getting under our skin — in less time than it took for the Marlins to have been declared losers of a suspended game at Citi Field the week before. That’ll buy a hated foe a cup of goodwill that comes with free refills.

Once we got to the Phillies and Braves, neither were the Mets’ hated foes. They were each other’s problems, and we were so there for it. When Philly pulled out in front, I know I was there for it. The Braves lost only 58 times in the regular season. It wasn’t enough. Them losing in ratcheted-up circumstances felt too good to not want to see more. Ahead in the series and with universally acclaimed ace Zack Wheeler on the mound (Zack Wheeler…where have I heard that name before?), I was frothing for the Phillies putting their foot on the neck of the Braves. The Phillies? Really? Honestly, they had me at “…foot on the neck of the Braves”. I wasn’t going to ask too many questions regarding the color scheme of the pants leg above the foot.

Then Travis d’Arnaud hit a home run (Travis d’Arnaud…where have I heard that name before?) and the Braves eventually pulled ahead in the second game, sealing it when Bryce Harper, who has been known to use the postseason to remind everybody of his all-timer status, got caught off first base in a somewhat understandable fashion, as an 8-5-3 double play had never before been turned in a postseason, let alone to end a postseason game.

Then the Phillies clobbered the Braves in Game Three, as Bryce Harper returned to using the postseason to remind everybody of his all-timer status, though by that measure, every Phillie was an all-timer, as they were all clobbering the Braves. The chef’s kiss aspect, of course, was Harper’s pair of glares at the Braves’ shortstop, Orlando Arcia, who thought it was a hoot that Harper had been caught off first base to end Game Two and let it be known volubly and de facto publicly, then acted all hurt about his precise sentiments getting out. Atta boy, indeed.

By Game Four, as the TBS cameras made me wish I had the maroon and powder blue concession at Citizens Bank Park, I’d forgotten that I normally hate the Phillies; forgotten that they’d employed Chase Utley longer than and before the Dodgers ever did; forgotten that I can’t look at Citizens Bank Park in sunshine and not see Brett Myers striking out Wily Mo Peña to end the 2007 regular season, which clinched eternal darkness in my soul where the 2007 Mets were concerned; forgotten that I chronically cackled harder than Orlando Arcia ever did at whatever missteps or misstatements Bryce Harper made in a Washington Nationals uniform in 2015. Gotta say, in the nighttime moment, I was all in on the Phillies.

Because I was all in on the Braves being all out. How could I not be? They’re just so…Braves. Or they were, as they are no longer involved in the present tense of the postseason, having lost their NLDS in four games, or one more that it took for the similarly successful regular-season Los Angeles Dodgers to take their leave. I don’t see the Dodgers enough in the regular season to embellish my ongoing animus in their direction beyond what still exists for Chase Utley’s assault on Ruben Tejada, but the playoffs belong to everyone. Everyone can enjoy the Dodgers being bounced in October.

After two years of giving baseball’s best regular-season teams time to freshen up before re-entering the fray while their statistical lessers stay engaged by playing games that count, questions have arisen if this is the best way to conduct a postseason. Whither the 104-win Braves? The 100-win Dodgers? The 101-win Orioles, for that matter? They all withered, whisked aside by teams that won 90 games, 84 wins and 90 wins, respectively. How do we deal with this unintended disparity?

We deal with it. Or those teams can deal with it. My team won 75 games. This isn’t my problem. My team won 101 games last year and couldn’t take two out of three in their mandatory first-round series. So much for staying engaged and playing games that count. Maybe something is wrong with a setup that doesn’t more easily enable the teams with the best records over 162 games to carve a path to the World Series. Or maybe something is wrong with each of those teams on an individual basis in a given week. Or maybe a team that can be very good for a few days, like the Diamondbacks, isn’t tangibly lesser when compared to a very good team not playing its best, like the Dodgers.

Enjoy those 162-game seasons if you were blessed with a golden one. It’s six months of unrelenting ecstasy that needn’t be permanently tarnished because a few days in October didn’t go according to plan. That’s just my off-the-cuff advice to those who are now ensconced in the peanut gallery with the rest of us. What do I know? My team won 75 games.

My team for the rest of the way is…I dunno. The Phillies are still the Phillies. They managed to find the bandwidth to express their thoughts about the Mets during their clubhouse celebration that was ostensibly dedicated to defeating the Braves, so I see no point in getting even temporarily attached to them (though it was nice to be remembered, I guess). The Diamondbacks are plucky and admirable — and my gratitude for the 2001 World Series is forever — but for all the desert pastels they’ve donned, to me they’re beige. In the other league, the Rangers and Astros are loaded with ex-Met pitchers, active and otherwise, who’ve won Cy Youngs. Some years that’s a feature. This year it’s a bug, as in it bugs me.

But whatever. A little more high-stakes baseball for the peanut gallery to take in prior to the staring out the window and waiting for spring commences in earnest. The playoffs belong to everybody, us included.

National League Town watched the playoffs, too. Hear all about it.

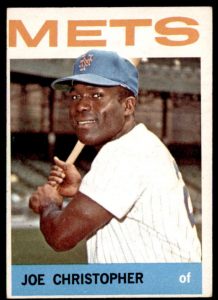

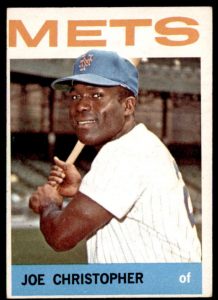

by Greg Prince on 7 October 2023 5:37 pm The scouting report I have cobbled together regarding Joe Christopher’s New York Mets career of 1962 through 1965 is he could run pretty well; he could hit pretty well; fielding was optional; and none of it much mattered, because to those who fell hard for the early Mets, Joe’s most outstanding tool was personality. Anecdotal evidence suggests it was off the charts. I wasn’t a first-hand witness, but I don’t think I’ve come across any player from the New Breed days whose name more often elicits a response of “he was my favorite.”

Most Valuable Personality. Joe, the first ballplayer from the Virgin Islands to make what for many years we called without qualification the majors, died this past Tuesday, October 3, a helluva baseball date in general and the 58th anniversary of his final game as a New York Met. Joe might have appreciated the connection, given his interest in numerology. That bromide about a ballplayer dying twice, the first time when he’s done playing, doesn’t quite fit here, because Christopher would get some playing time with the Red Sox the next season and keep going in the minor league for a little while thereafter, but the best part of his baseball life ended with his trade to Boston. That is not a provincial inference. Joe said as much in his farewell letter to George Weiss once the right fielder was shipped north in exchange for shortstop Eddie Bressoud.

Christopher made a habit of corresponding with the front office every offseason, even if all Weiss and his staff were looking for in the mail was a signed contract. One of his letters, when he was seeking a raise, ran nine pages (he’d have fit in well had he tried his hand at the blogging medium). He was briefer at the end of 1965, concluding a couple of paragraphs expressing his appreciation for his tenure as a Met by telling the club president, “The four years I did spend with the Mets’ organization were the four most glorious years I ever did spend in baseball. I also want to thank you, Mr. Weiss, for having confidence in me. It made me have confidence within myself.”

And if that doesn’t get you, the postscript will: “It still hurts not to be a Met.”

The fifth pick the Mets made in the 1961 expansion draft — right after Gus Bell, right before Felix Mantilla — Joe Christopher wasn’t exactly an Original Met if you’re a stickler for defining Original as someone on the Opening Day 28-man roster, but he’d be along eventually. Though he’d been a member of the 1960 world champion Pittsburgh Pirates, having roomed with fellow Caribbean native Roberto Clemente during their pennant-winning campaign, the 26-year-old was sent to Syracuse to start 1962. But by May, once Bell was identified as the player to be named later in the trade that brought Frank Thomas to the Mets from the Braves (never mind that Bell had played alongside Thomas for more than a month as a Met), Christopher was promoted to the bigs. The Mets employed 45 players in 1962. Joe was the 35th to debut, on May 21. Ten are still with us. They’re all Originals in their own right.

Christopher showed up literally the day the competitive aspect of the year began to go altogether down the tubes for the 1962 Mets. That trajectory should not be attributed to Joe’s presence. It was a team effort. On May 20, the Mets had swept a doubleheader in Milwaukee to complete a 12-10 stretch that had elevated the Mets into eighth place with a 12-19 record overall, a splendid recovery from their 0-9 start; they haven’t been as close to reaching .500 as a franchise since. Then, after leaving Bell behind at County Stadium as delayed payment for Thomas, they prepared to fly south to Houston and maybe even greater heights in the standings.

This was the legendary night into morning when a) the charter aircraft the Mets were supposed to board in Milwaukee was put on the DL with engine trouble; b) United Airlines entertained the Mets with a cocktail party at the airport until they could roll a new plane in, which didn’t happen until around midnight; c) the flight to Houston had to be diverted to Dallas in deference to heavy fog; d) the team arrived at its hotel in Houston at 8 AM; and e) Casey Stengel instructed traveling secretary Lou Niss that, “If any of my writers come looking for me, tell them I’m being embalmed.”

As were the Mets. Starting that night in Houston, the Mets took off on a 17-game losing streak, coinciding with Joe Christopher’s first official appearance in a New York Mets uniform. The road trip that commenced in Wisconsin and wound through Texas and California represented quite a welcome for the outfielder, who was finding out what made his new team so gosh darn Original.

In his first game, Joe doubled, moved up to third on a wild pitch and was stranded there in the eighth as the Mets lost by one to the Colt .45s. The Mets were 12-20.

In his second game, momentum turned on a deep fly ball that, per Dick Young in the Daily News, “speedy Joe Christopher sprinted obliquely for”; it “shot up his glove and made contact — only to have it pop out of the pocket for a triple” that scored the difference-making runs in a 3-2 defeat. The Mets were 12-21.

In his third game, at Dodger Stadium, Christopher drove in his first run and was thrown out in his first stolen base attempt. The Mets lost, 3-2, and fell to 12-22

In his sixth game, Joe hit his first Met home run, off future Hall of Famer Gaylord Perry of the Giants, tying the game in the sixth. The Mets lost, 6-5 in ten on Willie Mays’s home run off Jay Hook. The Mets were now 12-25.

In his seventh game, Joe inadvertently launched the Mets into their first on-field fracas, getting clipped in the batting helmet while running between first and second as Orlando Cepeda attempted to complete a double play. Joe had to leave the game, but the Mets were already feeling chippy and one of their teammates going down only incensed them further. Soon enough, Roger Craig was drilling Cepeda, Cepeda was jawing at Craig, Craig was trying to pick Cepeda off first, then Willie Mays off second (because what would a Mets-Giants game be in 1962 without Willie Mays on base?), which led to a hard slide by Mays into shortstop Elio Chacon, who wasn’t pleased. Chacon went after Mays, Cepeda went after Craig, and the Giants won by six despite the Mets’ feistiness. The Mets, “outclassed but not outfought,” wrote Young, were 12-26.

Christopher would be back in the lineup a few days later, collecting three hits and scoring two runs against the Dodgers in the erstwhile Brooklynites’ first return to New York; Dem Bums won, 13-6, in the opener of a doubleheader to which none other than Roger Angell, reporting from Manhattan that Memorial Day, traced the birth of the chant “Let’s Go Mets!” The chant lives on today. The losing streak extended through the nightcap and then some, until the Mets’ record plunged to 12-36. Joe would not be a part of a winning effort until June 8, 18 days after his first game. His batting average was .193 by then. It would be up to .244 — with eleven speedy base thefts — by year’s end, indicating a pretty decent surge for player on a team whose results were legendarily indecent.

But the 1962 Mets weren’t about results. They were about legend, and Joe was in the middle of one its most enduring. That story, authentic or embellished, about Richie Ashburn learning to shout “¡Yo la tengo!” so the Spanish-speaking Chacon at short would know Ashburn in center was calling him off a fly ball…only to have monolingual left fielder Thomas trample Ashburn because nobody thought to inform Thomas what was Spanish for “I got it!” was facilitated by Joe, a veteran of Puerto Rican winter ball, serving as Richie’s second-language tutor. “¡Yo la tengo!”, as legend (and band), has outlasted even that 17-game losing streak as a going concern. It’s been around almost as long as “Let’s Go Mets!”

Of all the principles in the YLT tale, Christopher lasted longest as a Met. He survived the Polo Grounds’ closing in 1963 and was planted in right field for the Mets’ first-ever win in the borough of Queens on April 19, 1964, contributing two hits and two runs in support of Al Jackson’s shutout of visiting Pittsburgh. Joe’s talent for getting things going and making things happen continued unabated. The Mets might have been succumbing to one of their usual defeats to close out May 31’s Shea doubleheader versus the Giants, when Joe took it upon himself to belt a two-out, game-tying, three-run homer in the bottom of the seventh. Thanks primarily to his knotting things up, there’d be 16 more innings that day, adding up to 23 for the game and 32 for the day. The Mets would turn a triple play in the fourteenth. Mays would fill in at shortstop. Perry went ten for the ultimate San Fran victory. Larry Bearnarth held the fort for seven innings in relief, in advance of Galen Cisco going the final nine in defeat. Of course there was defeat. These were the Mets. They weren’t good, but they weren’t boring. Ed Kranepool, then freshly recalled from the minors, still tells the story of playing all 32 innings following his having played a full doubleheader for Triple-A Buffalo the day before.

Joe Christopher, however, didn’t make his 1964 only about being anecdotal and incidental on behalf of a ballclub whose play often seemed accidental. A student of both hitting and history — the man soaked up a how-to booklet by Paul Waner and may have been the only Met to recognize irascible 1962 coach Rogers Hornsby as an honest-to-god resource — he boned up and started addressing the ball with authority. He was hitting over .300 until mid-June, took a dip in the average department at midseason, then recovered in a big way. In one of the better Met weeks of the 1964 season, during the same August series when rookie Dennis Ribant burst upon the scene with a ten-strikeout shutout of the Pirates, Joe went wild versus his old team: a double, a homer and two triples in a 7-3 win before the home folks, fans who withstood a rainy night to stand and applaud Joe’s exploits. The dozen total bases set a team record, one of the few that wasn’t related to prodigious amounts of losing. Joe’s bat placed the Mets square in the middle of a five-game winning streak that even Johnny Carson acknowledged in his monologue once it reached four. That’s what big news it was for the Mets to not lose for a few days.

The Mets were 40-82 when they cooled off, and the laughs reverted to being back on them, but Joe kept up his hot hitting for most of the rest of 1964. On the final day of the season, when the Mets were trying their best to play spoiler in St. Louis, Joe laid down a bunt for a base hit that made certain he’d go into the books with .300 average that looked plenty sleek alongside his 16 home runs and 76 runs batted in. Nobody knew what an OPS+ was in 1964, but Joe’s was 135. For context’s sake, that ballpark-adjusted combination of on-base percentage plus slugging percentage to express how good a batter is versus the league average was higher than anybody’s on the zillion-dollar 2023 New York Mets. As was, no everyday Met topped it in the Mets’ first six seasons, and no other Met produced a markedly better all-around traditional stat line prior to 1969.

For one year, Joe Christopher was an offensive force. For four years, the other side of the game, like that triple in Houston back in ’62, more or less eluded him. Pitcher Tracy Stallard went so far as to complain to reporters about Joe’s defense in the midst of his right fielder’s banner batting season, albeit after a misplay on Christopher’s part doomed one of Stallard’s July starts: “Christopher is the only .300 hitter I have ever seen who hurts a ballclub. He improved his hitting this spring. He should have worked on his fielding, too.” That’s some rough criticism (Tracy softened it after Joe’s big game versus the Buccos by allowing “he’s doing better”), but as the years went by, a chorus of Met teammates backed up Stallard’s assertion when asked.

Bill Wakefield: “Joe had a little trouble in the field.”

Bobby Klaus: “He got to a lot of them, and a lot of them he didn’t get to.”

Gary Kroll: “He was a good hitter, but he couldn’t field worth a damn.”

Ron Hunt: “God, he was terrible in the field.”

Yet Joe Christopher, who did not repeat his hitting exploits in 1965, maintained a place in the heart of Mets fans for decades to come. They remembered the base hits, yes, and might not have forgotten the catches that didn’t come to fruition, but what stayed with them the most was the sincere smile and heartfelt engagement of a Met who didn’t put himself above the crowd. The right fielder bridged the distance between his position and the adjacent stands with a stream of back-and-forth chatter (hopefully between pitches). Everybody, it seems, also remembers the ears, the most famous pair of ears in Mets history, at least until Joe Musgrove’s appeared suspiciously shiny on the Citi Field mound as the 2022 playoffs were ending ignominiously.

“When fans in right field cheer Joe Christopher as he trots to his position after a clutch hit or running catch,” Dick Young advised readers of the Sporting News as 1964 wound down, “Christo wriggles his ears for them. This makes his cap quiver, and the New Breed roars with delight.” Joe Donnelly in Newsday wrote, “He wiggles his ears and his cap tips without a hand going to his head.” Whether it was a wriggle, a wiggle or a waggle, it left an impression. All of it did, whether it was fan or reporter taking in what Joe had to offer. In 2017, George Vecsey recalled Christopher as “one of my favorite players in those first loopy years of the Mets,” someone who “talked of spirituality and art and would whisper to writers he trusted, ‘I’m a better ballplayer than you guys think I am.’”

Joe lived to be 87. It’s still great that he was a Met.

by Greg Prince on 5 October 2023 10:55 pm Did we have a Billy Eppler Era? Not quite two years since becoming GM; can’t say they weren’t eventful. Lots of high-profile free agents, which had a lot to do with the owner’s wherewithal to spend, but somebody had to do the hands-on negotiating. Handful of trades that didn’t pan out, then a slew of future-leaning swaps that look good in down-the-road terms, but that’s necessarily TBD. Whatever went on in the way of organization-building, which is never apparent to the layperson until somebody writes a story telling us what was built was just what was needed or clearly not enough. Not an excessive amount of public paeans to “culture” that I can recall, which was refreshing. One season making the playoffs. One season nowhere near them. Mysterious exit late one afternoon that grew a little less mysterious as that afternoon’s evening wore on.

Eppler said on Thursday he was leaving the Mets so David Stearns could have a “clean slate” in creating the Mets in his own president of baseball operations image, which seemed a little curious at first report, in that dating back to midsummer, Steve Cohen indicated Eppler would be around under any POBO to be named, giving him far weightier a vote of confidence than he gave Buck Showalter. Confidence in Showalter evaporated by Sunday, but at Stearns’s introductory press conference on Monday, David gave Billy what sounded like a unconditional endorsement, or at least didn’t euphemize too hard when asked about his predecessor continuing on in a different/diminished role.

Take ancient precedent with grains of salt, but when reigning Met GMs Joe McDonald and Jim Duquette were informed they would soon be reporting to newly named successors (McDonald to Frank Cashen in 1980, Duquette to Omar Minaya in 2005), those arrangements didn’t last long, and the former GMs each soon moved on from the organization for posts elsewhere. Although Stearns was hailed in advance as a superexecutive the brilliant likes of which we’ve never before seen, I thought there has to be some level of discomfort for Eppler being told he was no longer the lead non-Cohen decisionmaker in these parts. But if all concerned were on board, so be it. I’d already spent more time than I cared to this week trying to remember the names of Mets general managers since 2018.

Within hours of his graceful resignation, we learned via multiple outlets that Eppler is apparently under investigation by MLB for improper use of the injured list, which seems unfair, given that the Mets looked sick all of 2023, so maybe there weren’t enough of them sent to a doctor. It probably means guys who weren’t injured were put on the injured list to ease roster logjams. The Mets always seemed to have a roster logjam and somebody always seemed to be going on the IL to make way for the next fringe character.

But I’m just speculating, not only about this investigation business, but any of it. When we watch a game, and we see somebody strike out, we can say what we saw and perhaps articulate a legitimate opinion of why what just happened happened. “He swung at the pitch and didn’t hit it because he swings at pitches he can’t hit.” Discerning front office machinations without first-hand knowledge or access to an informed source willing to whisper in our ear that, for example, it was Eppler and not Showalter who insisted Daniel Vogelbach was exactly the kind of DH this team needed in its lineup most days amounts to guessing while trying to sound intelligent.

So I don’t know any more than anybody else about what all went on beyond the surface in the Billy Eppler Era. I’m not even sure if there was a Billy Eppler Era. Eras in Flushing tend to be fleeting.

by Greg Prince on 4 October 2023 10:35 pm For all you completists in the crowd, it’s our privilege to report a final final score: Mets 1 Marlins 0 in eight rain-shortened innings last Thursday, ensuring the Mets were 75-87 in 2023, rather than whatever it appeared they were when the tarp went on; no resumption was attempted; and nobody from MLB told us for absolute certain what the hell was supposed to happen vis-à-vis the W-L-T columns of the standings. Hopefully, Buck Showalter has a lucrative bonus clause that kicks in as a result of his having managed this extra win whose conclusion was delayed by a mere 132 hours.

Also, let us not overlook that this was an additional loss pinned on the Marlins the morning after they dropped Game One of their Wild Card Series versus the Phillies, and the morning before they were about to be blown out of Game Two in that best-of-three, ending their postseason in two flops of a fish’s tail. Hey, if they wanna swing by Citi Field to take care of that ninth inning now that we have nice weather and they have nothing else to do…nah, they probably don’t. But they’ll always have the memory of taking a lead that no longer exists, not to mention the hits and runs that have been wiped away by a slowly but surely applied rule that, truthfully, is kind of stupid. But so were all alternatives.

So we lost our last game of 2023, on Sunday, but we came away victorious with our final result, on Wednesday. Nothing like going into winter on a quasi-winning streak of one with an asterisk.

Plus a new episode of a new episode of National League Town!

by Greg Prince on 3 October 2023 10:50 am In a few weeks, David Stearns, Billy Eppler and perhaps Steve Cohen will gather in the Shannon Forde Press Conference Room at Citi Field to introduce the 25th manager in the history of the New York Mets, a day to which I look forward, ’cause ya gotta have a manager. We had a manager until Sunday — a four-time Manager of the Year whose most recent year wasn’t gonna win any awards — but a VACANCY sign blinks in that office at present. It’s a big enough deal when you bring in a manager or a general manager or a president of baseball operations that you turn on the lights in Shannon’s room or, if necessary, ask the credentialed media to log in over Zoom, and meet the new essential person tasked with helping make the Mets a winner.

The Mets should be as forthcoming and transparent as possible with the press. They should place their leadership front and center to share their philosophies and respond with clarity to all reasonable inquiries. But, in terms of making the kind of introduction they made on Monday or the one they will make pretty soon, they really have to stop.

You got your president of baseball operations.

You’ll have your manager.

You’re apparently satisfied with your general manager.

The owner of the team seems to be enjoying his long-term investment and doesn’t figure to be going anywhere.

Great! To everybody in those roles, please be really good at what you do and make the Mets as great as they can be and don’t make us wish any of you away. If you are that good at your assignments, don’t decide to move on for a while. Don’t necessitate more introductory press conferences.

We’ve seen enough of them.

It was right around six years ago we met a new manager, five years ago we met a new general manager. Four years ago we met another new manager…and one right after him, before a single game had been managed. Three years ago we met the new owner (who we greeted as a liberator). The new owner reintroduced us to the previous general manager who’d be serving for a spell in some loftier capacity (I always enjoyed seeing him, though I was surprised he was suddenly back on our scene). The old/new executive introduced us to a new general manager…which led to an interim general manager pretty quickly once the new general manager did what again? Something like what one of the recent previous managers did, but we didn’t find out about that manager doing what he did until he was gone from here. Anyway, the interim general manager proved very interim, and a new full-time general manager was introduced, then another manager, one with lots of experience and lots of gravitas, embodying lots of reason to think we wouldn’t be needing a new manager for years to come.

Two, exactly.

So we’ll get the new manager to replace Buck Showalter, who replaced Luis Rojas, who replaced Carlos Beltran (technically), who replaced Mickey Callaway, who replaced Terry Collins (whose seven years in the dugout made him a veritable Met FDR longevitywise) when the Metless postseason is over. He’ll put on a cap, maybe a jersey or perhaps a windbreaker and be ready to take charge as all the others were. The new manager will report to Billy Eppler, who replaced Zack Scott, who replaced Jared Porter, who replaced Brodie Van Wagenen, who replaced an ad hoc GM group that took over for Sandy Alderson when Sandy Alderson’s health wasn’t its best, though we were happy to learn Sandy was doing well enough a couple of years later when Steve Cohen replaced the Wilpons altogether and Alderson came in to temporarily more or less run the show as president of the Mets, which isn’t the same as president of baseball operations, which is what Milwaukee wunderkind David Stearns is here to be, the first ever, we’ve been told, to fill that particular position atop the Mets hierarchy or decision tree or whatever term of art is in vogue these days.

It’s hard not to sound cynical, a symptom of suffering from OIPCO Syndrome (that’s Offseason Introductory Press Conference Overload — ask your physician if PresOp is right for you). Perhaps if we weren’t on our umpteenth new era since the 2017 season ended, I’d be a little more relentlessly upbeat about the arrival of Stearns in Flushing, a presidential homecoming if ever there was one. I’m pretty upbeat as is. You don’t think I lapped up every answer Stearns gave about growing up a Mets fan? He had me at reminiscing how he loved listening to Gary Cohen, Bob Murphy and Ed Coleman, in that order.

Listing Gary Cohen first was shocking to anybody who always, always, always puts Murph first, but by the portion of the 1990s that young David had locked in on being a Mets fan, it was Gary who was on the radio every game, with Bob pulling back a little more every year. And Ed Coleman? Who thinks to remember that Ed Coleman did semi-regular play-by-play over WFAN? That’s bona fide fandom talking.

Which was great. The references to sneaking into Shea and interning for the Cyclones were great. The excitement about getting to raise his kids as Mets fans after their allegiance was held hostage in Wisconsin was great. The ease in the press conference spotlight was great, as if being in Queens is second-nature to him, not just another chance to trot out familiar execuspeak about building an organization that will make us all proud or whatever else he said, because, honestly, after so many of these types of press conferences, I’ve already forgotten the nonanecdotal stuff, because just go ahead and do it, David. Build this organization. Collaborate collegially with resources. Whatever. When you have a spare minute, tell Steve Gelbs how you really felt the day you learned Todd Zeile would be replacing John Olerud, and all of us (Zeile included) will nod and chuckle.

But seriously. Just be great at this. Get a great manager who will manage great for more than one year, or at all for more than two years. The owner can erect his casino, and the GM can work the phones, and the Manager to be Named Soon can communicate/motivate/make correct calls to the bullpen, and you can be the person who brought your childhood team to new and steady heights, a president whose transformative tenure can outlast that of even Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s.

Mostly, I’m sick of offseason introductory press conferences, save for the one officially announcing Shohei Ohtani’s record-breaking pact or any applicable get-together of that nature. Otherwise, enough meet and greet, enough dog and pony. Go, David. Sneak us into the promised land.

by Greg Prince on 2 October 2023 9:32 am Everybody had a hard year

Everybody had a good time

Everybody had a (M)et dream

Everybody saw the sunshine

—Lennon and McCartney, more or less

When I left for Citi Field early Sunday afternoon, Buck Showalter was the manager of the New York Mets. Before I arrived at Citi Field a little later Sunday afternoon, Buck Showalter let it be known that he would soon no longer be manager of the New York Mets. As I was leaving Citi Field as Sunday afternoon was morphing into Sunday evening and the National League baseball season in New York was officially over, there seemed to be a tad of confusion as to who exactly decided Buck Showalter wouldn’t any longer be the manager of the New York Mets — did Buck proactively decide to step aside, or was it sternly suggested to the reigning National League Manager of the Year that he should move along to create space for the club’s incoming grand operational poobah’s selection machinations?

Me, I was just trying to go to a ballgame, Closing Day, my twenty-eighth seasonal au revoir in a row (not including 2020), my thirtieth overall. The suddenness and the murkiness of the Buck Showalter exit kind of overshadowed the farewell to the season, as did that lingering ND from Thursday night. It was three days since the Mets and Marlins had their rainy game suspended, the one the Mets led, 1-0, at the end of eight, only to have the Marlins pull in front, 2-1, before the top of the ninth, let alone the bottom of the ninth, could be completed. When I wasn’t joining in the standing ovation for Buck during a sweetly choreographed lineup card exchange while THANK YOU, BUCK beamed from the EnormoVision screen — “there goes Vince Lombardi, having coached his last game for Washington” was the thought that popped into my head as the imminently erstwhile skipper saluted his players who were saluting him — I was continually checking my phone for definitive word of any ruling from MLB as to whether I had witnessed a win, lose or draw versus Miami the other night. With us finishing out the end of our string, and the Marlins being all but set for the postseason, I concluded I’d be comfortable having it called however it would be called. What I really wanted was for it to be called. The string should not be put into the books with a frayed end.

Sunday in New York like it oughta be, managerial dismissal, unresolved record and blowout loss notwithstanding. So Buck’s drama had some of my attention, as did some combination of the Diamondbacks, the Marlins and Rob Manfred’s minions (the out-of-town scoreboard made clear there was zero reason the proposed delicious four-out scenario would unfold on Monday), the combination of which served to distract me somewhat from the annual communing with finality I relish on Closing Day. That’s too bad, in that we had a perfect shirtsleeve Bobby Darin “Sunday in New York” First of October to sit in the ol’ ballpark one more time in 2023, a reminder that baseball played under sunny skies on a dry field is preferable to all alternatives.

Little was special about the season that was coming to its merciful end on Sunday, and little turned out special about Buck Showalter’s final game as Mets manager, Jose Butto’s six solid innings and Tim Locastro’s no-doubter home run notwithstanding. Yet I looked forward to this Closing Day in particular because of what it represented personally vis-à-vis how the baseball year began, and that element of Game 162/Decision 161 delivered.

Three days before Opening Day, my wife went into the hospital for what I chose to identify in conversation and correspondence as “a medical procedure,” because I didn’t choose to use the word for what the procedure was intended to address. Let’s just say she was diagnosed with that thing Major League Baseball urges everybody to Stand Up To during the World Series. Stephanie stood up to it courageously, and modern medicine (along with health insurance) did the rest. What she had to be operated on for was a version of that thing, a friend who is a researcher in the field told me, that is among the most treatable. You never want to get any form of it, he added, but if you have to get some form of it, this is the one to get.

Sure enough, the procedure played out as doctors described in advance, and the recovery proceeded without incident, which is easy for me to say, as I wasn’t the one recovering. The biggest post-op moment — and, as far as I’m concerned, the biggest victory of 2023 — came the morning of what was supposed to be the Home Opener, the one that got rained out because they thought it was going to rain, but it didn’t. The phrase we heard that day, ten days after surgery, was, “Your labs were better than your biopsy.” It carried the power of a thousand Outta Heres.

Followups have followed, and all has flowed smoothly against the backdrop of the first half becoming the second half and the Mets going nowhere across six months, yet I eagerly anticipated our going to the last Sunday of the year together. I always do, but this time more so and differently. It would have been nice had the Mets put together something more closely resembling a winning effort en route to their 9-1 loss to the playoff-bound Phillies. It would have been nice to have left the park not subject to bulletins from what has been institutionalized as the franchise’s biennial managerial search. It would have been nice to have known for certain if the Mets’ final record is 74-87, 75-87 or 74-88. But mostly it was nice sitting in Section 328 for two-and-a-half hours with who I was sitting with, occasionally clapping, occasionally groaning, constantly aware that in ways that elude the box score, it doesn’t get any better than this.

by Jason Fry on 1 October 2023 12:04 am It finally didn’t rain and the Mets finally got to play, and so for your recapper’s final go-round of the season our heroes presented one game that turned into a nail-biter, one Calvinball farce that was pretty entertaining for all its sloppy meaninglessness, a doubleheader sweep that didn’t matter, a depressing thought, and a happy memory for winter.

Which is a lot for an afternoon and evening!

First the nail-biter. It started out with Tylor Megill looking effective against a vaguely serious lineup of playoff-bound Phillies, showing off a forkball he learned from Kodai Senga and dubbed “the American Spork,” cheerfully deriding it as an off-brand Ghost Fork. The new pitch’s effectiveness seemed to vary, as did Megill’s early on, but he persevered and wound up capping a run of pretty good pitching with his ninth victory of the year, which is probably more than you figured he had.

Megill, David Peterson, Joey Lucchesi and Jose Butto have pitched pretty well as members of the Then Again, Maybe We Won’t Mets, sparking endless debates about whether garbage time is any different in an era of multiple wild-card teams and smaller September rosters. I don’t know the answer to that one and neither do you and neither do most front offices — we’re all waiting for another generation’s worth of data. But I do know that those pitchers’ collective competence has gone from surprising to heartening, which isn’t a bad thing to take into winter no matter how much of a mental discount you affix to it.

The game nearly got out of hand once Megill exited, with Adam Ottavino having another shaky outing as closer du jour — the Phillies were poised to tie it but Jake Cave had a strangely tentative at-bat, looking at Ottavino’s only perfectly executed pitch of the inning for a called strike three with a runner on third and one out. Ottavino then got the light-hitting Cristian Pache and the Mets had escaped.

Escaped into the nightcap, which was madness — a fusillade of homers and hit batsmen and other lampshade-on-the-headery. No one got particularly exercised about the HBPs, which was a relief but not particularly a surprise, as both teams seemed to be in a bit of a Let’s Not Play Two fog with the exception of Francisco Alvarez, who sent two homers to nearly the same spot — the facing of the second deck a very long way away. Which led to … nope, I’m saving that one.

In the middle of the game Steve Gelbs came up to the booth for a report grappling with velocity and pitcher injuries, which was diligently researched and well-intended even if I didn’t think it particularly broke any new ground. (Honestly, read Jeff Passan’s The Arm, likely to remain The Book on this subject for quite some time.) The best thing that came from Gelbs’ endeavors (which I really did like, lest you think I’m damning with faint praise) was that he got Ron Darling talking about how he would have been a different young pitcher in an era where everybody from teams and front offices to agents and potential draftees are chasing velocity — Darling talking pitching in general and his own missteps and regrets specifically is always worth a listen.

Listening to the booth hash things out, though, I had a depressing thought, one I kept waiting to see if one of the SNY principals would echo. (OK, the PIX principals at that point, but never mind.) My thought was that there’s no solution to the vicious circle of velocity/lack of control/injuries because baseball already has a ruthless one that works perfectly well: When a pitcher breaks, you just get another one.

Think of the parade of hard-throwing right-handed relievers who’ve trudged up and down the Citi Field mound in recent years, from Jacob Rhame and Jamie Callahan to Drew Smith and Phil Bickford — who, as if on cue, hit a Phillie during the earnest conversation about velocity and the ability to pitch. All those guys are in The Holy Books but in my brain they’re a blur of radar guns and never finding reliable secondary pitches and getting DFA’ed, because they’re all essentially the same guy.

And this ruthless strategy isn’t anything new. Decades ago, when young pitchers came down with a “sore arm,” the lucky ones turned into junkballers and the unlucky ones turned into truck drivers. Tommy John surgery has essentially let baseball double the pool: Now you can stick your broken pitcher on a shelf for a year and try him again, or let someone else take him home. Combine that with more international talent than in previous generations, with Asia now supplying a new influx, and you’ve got an effectively endless supply of interchangeable, disposable arms. And if you’ve got that, what’s the incentive for the people who control how those arms are used to do anything differently?

Maybe that point was a little too Marxist for SNY, or a little too depressing. Certainly it’s too depressing for me to end with, which is why I’m going back to the memory I hope will sustain me through the winter.

I love the way Francisco Alvarez devours baseball whether he’s got a bat in his hands or is encased in the tools of ignorance — he approaches the game like it’s an all-you-can-eat buffet and he was just delivered from a month on a bamboo raft in the Pacific. But my favorite sight of all is the Alvarez home-run trot. Alvarez has given us epic bat flips and gun-flexing and million-watt celebrations, but what really makes me laugh is the way he picks up his knees when rounding the bases, like one of those carefully coiffed and trained show ponies.

The season’s ending with three meaningless games against a team headed for the brighter lights. (With, perhaps, a farcical 15-minute coda that no one wants.) It’s not what any of us had in mind. But the first two of those games had their pleasures, and I can already guarantee you when I look out through blowing snow I’m going to be thinking of Alvarez high-stepping along between second and third, beaming and gesticulating like a leading man playing to the back of the house, and I’ll sigh and think about how happy it made me the last time I saw it and how eager I am for the next time to come around.

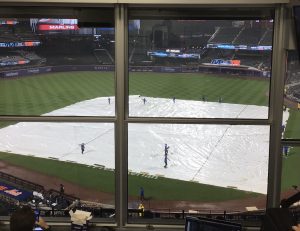

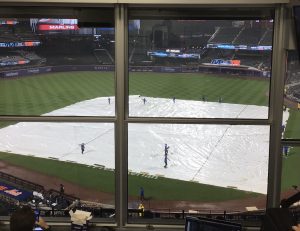

by Greg Prince on 29 September 2023 4:24 am I’ve never felt more like Jack Buck after returning home from a ballgame, for “I don’t believe that I don’t know what I just saw!”

Did I see the Mets play the Marlins? Pretty sure I did. That was important to me, as, entering Thursday, I had not seen the Mets play the Marlins in person yet in 2023, and I’ve seen the Mets play the Marlins in person at least once (usually too much) in every non-pandemic season since 1997. I can confidently write “Miami” in The Log after having personally observed them in action versus the Mets.

Did I see the Mets beat the Marlins? I don’t think I did. True, the Mets led the Marlins, 1-0, at the end of the eighth, the last completed inning of the evening before a downpour made the field unplayable during the top of the ninth. With all those qualifiers, and knowing what we know about an official game, it kind of reads like a Mets win. But I was there, watching through the press box window, and I’d have to swear on a stack of media guides that I did not witness a winning effort on the part of the home team. For a few minutes, I thought it might be. I thought it might be rued in Marlin lore as The Rafael Ortega Game once the little-used outfielder, subbing for Brandon Nimmo once Nimmo left with an injury, drove in, after seven-and-a-half scoreless innings, the game’s only run. What lovely reprisal for not only [your choice of crime inflicted upon Metsdom by the Teal Menace], but Jesus Luzardo’s ten strikeouts across seven-and-a-third innings.

The Citi Field tarp is perpetrating a coverup, preventing us from finding out whether the Mets won, lost, tied or even played Thursday night. Did I see the Marlins beat the Mets? We were likely getting close to that eventuality, what with the Marlins usurping that thin 1-0 lead of the Mets and transforming it into a 2-1 edge of their own in the top of the ninth off noted closers Grant Hartwig and Anthony Kay. Hey, it’s only a game with an impact on the entire postseason picture. Might as well try whoever you have out in the pen to finish off a contender. Ah, what’s a closer but a label? Neither Hartwig (who did put up a zero in the eighth) nor Kay lived up to the example set by David Peterson, who not only shut out the Marlins for seven innings (with 8 Ks and a touch of help from a six-minute two-team video review challenge that correctly removed a Marlin run from the scoreboard), but has never given up a run the three times I’ve attended starts of his: 19 IP, 0 R. How am I not on Peterson’s pass list? Reed Garrett became the third pitcher of the ninth just in time to give up a hit and then be overtaken by a tarp that was about as welcome in the ninth inning as a skunk at a picnic…or the Marlins anywhere.

Did I see the Mets-Marlins game suspended? Not until after I bolted the hermetically sealed comfort of the press box to take on the rain, the rails and the ride home. Good call, I have to say. When I exited Citi Field, the rain delay was about 50 minutes old. When I walked into my living room and flipped on SNY, the delay was well past the two-hour mark, and an impromptu Amazin’ Finishes marathon was in progress, punctuated by live shots of the tarp sitting on the infield, nudged off the infield, and returned to the infield — with Skip Schumaker registering his displeasure with Mother Nature’s timing and nerve. Altogether, it took three hours and seventeen minutes of steady precipitation for the powers that be to decide no more baseball would be attempted in Flushing this early Friday morning. What could have been The Rafael Ortega Game devolved into that night we kind of inconvenienced the Marlins.

Did anybody see or hear anything definitively conclusive about concluding the Mets-Marlins game? MLB, in whose hands this rests, basically replaced that batter in its logo with a shrug emoji. Late-breaking consensus, however, has formed around the Marlins having to fly back to New York from Pittsburgh to finish the game Monday if necessary to determine Wild Card clinching…or maybe just in general. Baseball likes its games completed, though if Miami already has a playoff spot in the bag (they’ve got a half-game lead on the Cubs plus a tiebreaker), one isn’t sure why the hell they’d wing their way to Gotham to secure what I hate to call a meaningless win, because we see meaning in everything in baseball, but c’mon. If there’s no berth and no seeding at stake, what lures the Marlins for an inning-and-a-third rendezvous with density?

Yet if the game isn’t over — and it’s not — and they don’t pick it up, what exactly happened Thursday night?

The ol’ “in the event of rain, the score reverts back to the last complete inning” rule that would effectively erase the two runs Hartwig and Kay gave up doesn’t exist any longer, so there’s no slipping this one into the win column for the Mets on a technicality, but you really can’t say the visitors have prevailed if the home team isn’t granted last licks.

I’d get a kick out saying I saw the first Mets tie in 42 years, but it wasn’t tied when the tarp came out to halt play.

The Marlins could forfeit on the grounds that by Monday, if they’ve clinched, they’ll have better things to do, like prepare for the playoffs ASAP, but Schumaker doesn’t appear to be of a mind to give the Mets anything other than another piece of his mind.

The game could magically disappear from the team’s respective won-lost records, sort of a virtual tie, with all player stats standings, but what’s the basis for that, exactly? MLB has been suspending and resuming otherwise obvious rainouts for a few years now, sometimes insipidly, but to date, a suspended game with real ramifications and little time to tighten its loose ends hasn’t had to absolutely, positively be finished. Finishing it with the Marlins’ and the Cubs’ and maybe the Reds’ playoff fates in the balance would be one thing (even if it’s for four outs and would be a nuisance to every Met whose U-Haul will be double-parked on Seaver Way), but to finish it because every team is required to file in its ledger 162 indisputable results?

I live for the bookkeeping of baseball, but even I think there ought to be a classy way out of finishing this game if there are no serious implications on the table. Yet I did go to this game, and my Log wants to know what I just saw. As of this moment, I can’t write it down as a loss, I can’t write it down as a win and I can’t write it down as a tie. I can’t even pencil it in as a suspended game if I don’t know for sure that it will be rescued from suspended animation. I’ve already written down that I saw the Marlins, as I have in every non-pandemic season since 1997, and I’ve already written down that I saw Peterson, who clearly loves to pitch in front of me. But I can’t write down what “my” record is against the Marlins at Citi Field (it was 22-13 coming in); or “my” lifetime record at Citi Field (currently 179-132 with one dangling “?”); or the W/L aspect of the game; or its final score. I’ll need a dab more information to finish this entry, thank you very much.

Come in from out of the rain and listen to a new episode of National League Town.

by Jason Fry on 28 September 2023 12:32 am It wasn’t raining Tuesday night. The problem was one of tenses — not what was happening weather-wise but what had happened. It wasn’t raining, but it had rained. Considerably. Considerably as in “enough that they give the concentration of rain a proper name and track it over the ocean like it’s an invasion fleet.”

An amount of rain, in other words, that might make you cover an infield.

The grass-mowing, sod-tending members of the Mets didn’t do that while the bat-swinging, error-making members of the Mets were losing games in Philadelphia. Why? Beats me. The reason hasn’t been made clear, perhaps because it can’t be made clear. I’m neither a meteorologist nor a groundskeeper, but it seems to me that the presence of a tropical storm suggests a tarp be deployed.

No rain Tuesday, no game Tuesday. The field was unplayable, the Marlins’ reaction was unprintable, and I can’t say I blame them. If Francisco Lindor had offered the Marlins a jaunty “let’s play two” on a sunny Wednesday afternoon, one of them might have punched him in the face, and I wouldn’t really have been able to say I blamed them for that either. The Marlins are scratching and clawing for a postseason berth; any scratching and clawing done by the Mets makes you back away worrying about fleas.

Despite their wrath, the Marlins didn’t exactly come blazing out of the gate Wednesday afternoon. Pete Alonso homered and Lindor homered and Mark Vientos homered and Joey Lucchesi motored through the Miami lineup. You could see when the Marlins quit in that first game — Jorge Soler showed no particular interest in participating while in right field, which means the Little League remedy for such aptitude was already unavailable — and I wondered if they’d bring anything to the fight in the nightcap.

But they did: The Mets bent Johnny Cueto, as Lindor hit his third home run of the day and joined the 30-30 club, but couldn’t break him. Meanwhile, Kodai Senga struck out his 200th guy in his season finale, but also gave up a pair of homers, resulting in a stalemate.

The second game looked like it was going to turn when Jake Burger was at the plate with the bases loaded, two out and the score tied 2-2 in the top of the seventh, facing a rather shaky looking Phil Bickford. But Burger had to deal not only with Bickford but also with home-plate umpire Ramon De Jesus, whose strike zone was the kind of abstract art that makes you sniff that “my kid could do that.” (And if you’re right in that appraisal, please discourage your kid from both art school and umpire school.) De Jesus punched Burger out on a pitch that was clearly outside, then ejected Burger when he slammed down his helmet in thoroughly understandable disgust, tossing Skip Schumaker for good measure when the Marlins skipper came out to remind De Jesus that no one came to Citi Field to watch him.

That substitution looked fateful two innings later, when Adam Ottavino loaded the bases with nobody out (sigh) and found himself facing not Burger but Yuli Gurriel. (If I weren’t too tired, I’d try for a Hamburger Helper joke here. Let’s just pretend I did and it was funny.) Gurriel smacked an Ottavino sweeper right at Brett Baty, and all Baty had to do next was throw the ball home and watch Omar Narvaez step on the plate and then watch him heave the ball to Alonso at first, which would turn the inning around, and then…

…except Baty did what I just did. He tried to make the throw before he caught the ball and … oof. It’s been that kind of year for the kid.

Baty turned two outs into none, it was quickly 4-2 in favor of the finny visitors, and soon after that the Mets were done and the Marlins had not only survived but also pulled into a tie for the last wild-card spot. A split — which, if you think about it, wasn’t bad for a day’s work, as it required beating the Mets (well, once at least), the Mets’ groundskeepers, bad umpiring, a tropical storm and some measure of unkind fate.

You could almost admire it … well, if it weren’t the Marlins we’re talking about.

by Greg Prince on 25 September 2023 12:44 am • The Mets lost, 5-2, at Citizens Bank Park on Sunday night, completing a weekend in which there was a definitive milestone of futility planted every step along the way. Sunday’s wasn’t as momentous as clinching a losing record (Thursday), being mathematically eliminated from postseason contention (Friday) or assuring the 2023 Mets would drop further from their previous year’s record than any Mets team before them (Saturday), but by losing, the Mets did fall to 14 games under .500 for the first time this season. There are always new depths to plumb with this team.

• The Mets were swept four by the Phillies, who had plenty to play for and played like it. So much for the spoiler role fitting this team like one of Francisco Lindor’s designer gloves.

• Impromptu Sunday Night Baseball — a 6:05 PM start was set Saturday night when the Phillies realized the scheduled one o’clock first pitch did not mesh with the ominous forecast — isn’t such a bad proposition when ESPN isn’t involved. Good advance contingency thinking rather than telling the fans to come to the ballpark and wait and wait for a window.

• The Mets lost on Fox/Channel 9 Thursday night, Apple TV+ Friday night, SNY Saturday evening and PIX11 on Sunday night. Four consecutive losses in the same series on four different frequencies must be some kind of record, unless you listened on the radio, in which case it was a lot of same spit, different day.

• Ronny Mauricio left the One Met Homer Only club, which is a fine club to join, but not so great a club to linger within. Mauricio exited by swatting for his second home run a Cristopher Sanchez pitch that was a little more than a foot off the ground when Ronny connected with it. It came down over the left field wall, 389 feet from home plate, having departed the young man’s lumber at a velocity of 112.9 MPH (which experts say is quite the thwack). A runner was on base at the time, the time being the top of the sixth inning. Up to that point, the Mets trailed, 5-0, indicating Mauricio was responsible for the entirety of his club’s offense.

• Sanchez went untouched by the Mets, except for that home run ball (which would have been a scorekeeping ball had Mauricio declined to swing, because it was barely off the ground). The Phillie starter lasted through seven, striking out ten, allowing only three hits and one walk. Jose Butto, on the other hand, took a step back from the progress he’d shown in recent outings. Only four innings for Jose, with four runs and four hits. Fours were not lucky in this case.

• Butto’s presence on the CBP mound had me thinking back to 2022, which is a dangerous exercise for anybody who’s been watching the Mets throughout 2023. Butto, called up to make his big league debut in Philly, started The Mark Canha Game, which became The Mark Canha Game (also The Nate Fisher Game) after Butto dug the Mets a relatively deep hole that cloudy Sunday, leaving the Mets down, 7-4 after four. Four wasn’t altogether unlucky in that case, as the Mets came back to win, 10-9. The 2022 Mets would forge that kind of comeback now and then. Those were the Damn Thing days, my friend…we thought they’d never end. Or at least go on for another year.

• Hello to Long Island’s Own Anthony Kay, the 1,218th Met overall and a fellow who can be said to have waited longer than most Mets to become Mets. We drafted him in 2013 (didn’t sign). We drafted him anew in 2016 (he did sign). We traded him in 2019 (for Marcus Stroman, who had one of those eventful Met tenures that a couple of years later doesn’t seem like it actually happened). We grabbed LIOAK back on waivers recently and called him up to fortify the bullpen from the left side, which he did with a scoreless inning-and-a-third Sunday. Who says you can’t go home again for the first time?

• So long to Peyton Battenfield, who was called up Friday to replace Jeff Brigham, yet was not afforded the opportunity to tell his friends and family that he was the 1,218th Met Overall. Buck Showalter, apparently, was not lovin’ a Battenfield. Peyton sat for two games and was optioned to Syracuse to make room for Kay. Given that the Triple-A season is over, that’s a pretty cold place to send somebody. And Syracuse gets pretty cold as is.

• Hi from across the field to brand new major leaguer Orion Kerkering, hot Phillies prospect who came into pitch the eighth and made three Mets batters appear totally ineffectual. I mean more than usual for this weekend. I wouldn’t normally get caught up in any opponent’s success at the expense of the Mets, especially not one who could be haunting us in the division for years to come, but a) Kerkering’s dad was caught on camera in absolute tears at the sight of his son’s debut; and b) Orion Kerkering is a USF Bull. Or was until he was drafted by the Phillies in 2022. I, too, was/am a USF Bull, albeit of a much earlier vintage. For one eighth inning on one Sunday night when the Mets were sleeping through their classes, I’ll give a Horns Up to the kid.

• Congratulations to my and Orion Kerkering’s USF Bulls for beating the Rice Owls, 42-29 in Saturday’s college gridiron action. Our USF Bulls haven’t made a habit of winning at football lately. Given that the Mets couldn’t take even one of four games from the Phillies; and that neither the Giants nor Jets could succeed between Thursday night and Sunday afternoon; and that even the formidable ladies of the Liberty were pretty much trounced in their WNBA semifinal playoff game, I need to bask in whatever victory I can find. Orion Kerkering and I are thus stoked about our Bulls boiling Rice.

• Happy Elimination Day, which arrived a couple of hours before Kol Nidre services, to all who observe. Like the Mets’ lack of postseason plans, the Yankees’ absence from October had been a virtually sure thing for months, but why let a festive annual occasion, however low-key it may feel this fall, pass without acknowledging its blessed nature? Good luck to every remaining American League Wild Card contender. Each of you is a winner in my eyes.

• Back on our going-nowhere end of town, six games remain, all at home. That’s 54 innings of Mets baseball, give or take, until there are none. I’ll probably need another week to get altogether melancholic about that. Spoilerwise, the Mets can still debone the Marlins a bit. The Phillies should have the NL’s four-seed locked down by next weekend. Honestly, the implications are light. Barring rain that can’t be worked around, the 2023 Mets can win as many as 77 games once over is over, or lose as many as 91. There is no good won-lost record at the end of this rainbow. There will be goodbye, though. Some years, that is for the best.

|

|