The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 19 June 2023 1:47 pm Someday in the future, a precocious Amapola Chloe Lindor might look at her birthday, consider her father’s occupation, and ask, “Daddy, what did you to in the first game you started after I was born?” And her dad Francisco will be able to rightly tell her, “I hit a home run for you. What made it even better was that it happened on Father’s Day.” Rightly impressed, the young lady might reasonably respond, “Wow, you hit a home run, which it would naturally follow boosted our family’s favorite team, the New York Mets, to a rousing victory, given the implications of the occasion and the romance with which we imbue baseball.”

To which Papa Lindor might also very reasonably reply, “Don’t you have some homework to do?”

I was very happy to watch Francisco launch a no-doubter of a home run to left field in the bottom of the first inning at Citi Field on Sunday, not only because it immediately halved the deficit the Mets faced from the two-run homer Nolan Arenado hit in the top of the first, but because I wanted to be a romantic about baseball. Lindor wasn’t in the starting lineup on Saturday in deference to the birth of Amapola early that morning. His paternity leave didn’t even last an entire game. He was back at the ballpark before first pitch and, after Buck Showalter determined he was sufficiently rested, he pinch-hit to lead off the ninth. Francisco reached base via hit by pitch to maybe get a rally going in a game the Mets trailed by two. The shortstop made it as far as second base. There was no rally. The Mets lost by two.

Ah, but Sunday was a new day, and Sunday was a literal whole new ballgame once Lindor, returned to the starting lineup and, still not having missed a single game in 2023, greeted Cardinal starter Matthew Liberatore’s fastball with 104½-MPH exit velocity. How could you not feel something percolating after that swing? Lindor, a new father for the second time, channeling the joy he’d expressed after Saturday’s game into a Father’s Day demonstration of appreciation for the miracle of life; putting the Mets on the scoreboard; answering two runs with a run; inspiring the 15,000 attendees within the sellout crowd who were handed orange bucket hats to contemplate tossing them into the air in celebration, creating a sky of blue and orange for the enjoyment for the 28,110 attendees within the sellout crowd who weren’t handed bucket hats…c’mon, this was too good not to work.

Francisco Lindor homers on Father’s Day after his child is born. And Pete Alonso! Pete Alonso burst from the injured list right back to first base! No embedding the Polar Bear with a half-dozen afterthought relievers in the Who’s Not Healthy Now report. No dispatches from Binghamton or Brooklyn on how the latest rehab game went. Nope, just Pete, ready to go. Maybe Pete, like Francisco (or Katia Reguero Lindor’s obstetrician), would deliver memorably before this weekend series versus St. Louis was through.

Usually I avoid setting myself up for storylines. Leave that to the pregame gambling sponsor and the naïve. Most everything you think is going to happen because it should happen doesn’t happen. Maybe it happens just enough to create a sense of precedent, or you can convince yourself that this is the sign, this is the day things get turned around. The sign is almost inevitably a misdirection and the turnaround rarely comes.

Still, Father’s Day, as Metsian a holiday as there is. Mr. Met has two daddies, one who decamped to San Fran, the other to L.A. Talk about being born with a Metipal complex. Our first Father’s Day, was June 17, 1962. We were swept in a doubleheader by the Cubs. The opener was the game when Marv Throneberry didn’t touch first. Over the radio that Sunday afternoon, Bob Murphy transmitted a plea on behalf of the real Baby Mets:

Marv Throneberry and several other members of the New York Mets, now that school is out, would like very much to move their families to New York for the summer if they can find a furnished house to rent someplace. If you know of one, don’t call but write Housing, The Polo Grounds, New York, 39.

You’d think the Metsies had paid their initiation dues by a) Marvelous Marv running them out of a triple (he didn’t touch second, either) and b) having their announcers act as their real estate agents, and therefore should be granted karmic Father’s Day consideration into perpetuity, especially considering what was about to come after never fully settling down in the Polo Grounds. Two years later, the Mets had permanent housing: Shea Stadium. The first Father’s Day they spent there involved another doubleheader sweep at the hands of the visitors — the Phillies — and another celebrated episode of a Met not touching a base — any of them. That was Jim Bunning’s perfect game of June 21, 1964. Mets fans, recognizing a lost cause when they saw one, showed sportsmanship unimaginable nearly sixty years hence, and cheered Bunning of the Phillies (ptui!) on toward perfection. They knew they weren’t going to get anything like it from their team.

The Mets wouldn’t come away from a Father’s Day without a loss until 1972, when, on that June 18, Yogi Berra could hand to the home plate umpire a lineup card with “MAYS CF” written atop it and hand the ball to SEAVER P; Willie recorded a single and a pair of putouts, Tom pitched a complete game at Cincinnati, homering to drive in the decisive run, and, with the Pirates losing to the Padres, Yogi had steered his team back into first place. In other words, it took THREE Hall of Fame legends for the Mets to make an unqualified success out of Father’s Day, though, to be fair, there were a few splits of twinbills in the ’60s, there was a rainout in 1970, and, despite the Mets being defeated by the Dodgers in Los Angeles, there was a big-picture triumph on Sunday June 15, 1969, via the trade for Donn Clendenon, a player who would add an air of elder statesmanship to a clubhouse of kids just learning to win.

Baseball being the daily grind that it is, one day, even Father’s Day, probably looks pretty much like the other from the inside. It’s little wonder that it was on Father’s Day 1987 that Ralph Kiner, who was on the New York Mets air for his 26th consecutive Father’s Day and who knows how many other days, sent out sentiments from Shea’s television booth that have outlived Ralph himself. According to Howard Blatt in the Daily News, Kiner said, “On this Father’s Day, we again wish you all a happy birthday.” Generations have chuckled at Ralph’s tongue-tangoing expense, but maybe he was just getting ahead of the game, specifically with Amapola Lindor in mind. On June 17, 2029, Father’s Day that year, Francisco Lindor’s second daughter will mark her sixth birthday.

Father’s Day 1987 stands out in the annals of my mind not for Ralph’s classic Kinerism, but because the Mets won that day. They’d won the day before and the night before that, too. They swept the Phillies. We’d been waiting for the Mets to make a habit of sweeping everybody, the way they seemed to the year before when they were winning more than a hundred games. To date, on June 21, 1987, the Mets were reminding us less and less of the team they had been the year before. They entered that weekend series in fourth place, 7½ games behind the Cardinals. Our team needed a boost. Our team’s fans needed hope. Taking three in a row, culminating in a Father’s Day 8-3 shellacking of Philadelphia at Shea, gave it to us. We’d picked up two games in the standings. More than half of the season remained. We could keep making up ground. Gary Carter, who rested in the bullpen and on the bench that Sunday said to Sports Illustrated writer Douglas Looney before the series finale that he found himself thinking, “Hey, maybe I really am feeling good.” Gary was referring to his nagging aches and pains, but he could have been speaking for our psyches. The year after our Year to Remember had played out as a hangover that would never quite let up. Yet here we were, showing signs of life, beating back a presumed lesser opponent and encroaching bit by fit on first place. Hey, maybe we really feeling good.

Happy birthday to us all, indeed.

The Mets didn’t get any closer to the Cardinals before the first inning finished on Father’s Day 2023, and they fell further behind as the second inning progressed, with an errant Eduardo Escobar throw to first pinning Carlos Carrasco behind an 8-ball destined to roll over him. Cookie gave up three runs on two run-scoring hits, and the Mets were down, 5-1, heading to the bottom of the second. But then, a little lightning struck. With two out, Jeff McNeil appeared barely grazed by an inside pitch, but it put him on first. Then Escobar, making up for his error, laced a fly ball to deep center that became an uncaught RBI triple (Tommy Edman ran it down, only to have it clank off his glove). The veteran who plays less and less immediately making up for his error, albeit with the help of a hit that could have been ruled an error: that’s karma! Then, after Mark Canha walked and advanced to second on a wild pitch, Brandon Nimmo stepped up.

Nimmo was the author of the hugest hit the last time the Mets won on Father’s Day, at Arizona in 2018. The Mets were playing dismally that afternoon and that entire June; they hadn’t won consecutive games in nearly a month. The Diamondbacks had extended their lead to 3-1 in the eighth, almost assuring that the Mets’ win the previous evening would be orphaned. The Mets make two quick outs in the top of the ninth. Then, somehow, a rally: Jose Reyes bunts his way on; Jose takes second on defensive indifference (which is what the Mets were playing with most days); our other Jose of the moment, Jose Bautista, hits a ball that glances off right fielder Jon Jay’s glove and turns into a double that scores our primary Jose to make it 3-2; then Brandon, in his first season as a regular, homers off Brad Boxberger to put the Mets in front, 4-3. Asdrubal Cabrera follows with another dinger, and the Mets go on to win, 5-3. It is shocking that the Mets arose from the almost dead. It is shocking that the Mets had now won two in a row. This was the June of 5-21 — FIVE Met wins the entire month, for criminy’s sake, as Nimmo might have muttered to himself when things weren’t going well. But things were going well for Nimmo. Not only had he created a rare Met winning streak, but he’d be going more or less home the next night, to Coors Field, playing in front of his parents, who were coming down from Wyoming to see him. Brandon gave them a belated Father’s Day present in the form of a leadoff inside-the-park home run, touching off a 4-for-6 performance and fueling a rout of the Rockies for the Mets’ third straight win.

After which, the Mets would lose their next seven, but we didn’t know that yet. We only knew Brandon was the star of the extended Father’s Day weekend show and, five years later, I knew Brandon was up in a game that wasn’t yet lost as of the second inning, and in 2023, he swung and connected for extra bases. Escobar scores! Canha scores! Nimmo, seeing his ball rattle down the left field line after Jordan Walker’s flailing dive totally missed it, steams past second and heads for third! Karma!

Alas, Ebullient Brandon, like Marvelous Marv, doesn’t touch a base he needs to. Or, more precisely, Arenado touches him on the arm before he can touch the bag. Ralph’s broadcast partner Tim McCarver drilled into us by 1987 that a player must never make the first or third out of an inning at third base, which is what Nimmo did by trying to stretch his sure double into an iffy triple. But, well, that’ll happen. I look at Brandon and I think of a term I heard Buck Showalter use a couple of weeks ago when he was asked for his recollections of managing incoming Mets Hall of Famer Al Leiter in the minors. Al, Buck noticed way back when, “had a lot of ‘want-to’.” So does Brandon. So does just about every one of these Mets. You’d figure every major leaguer does, but it doesn’t always show. There’s a so-called dad joke in there somewhere, something akin to “their ‘get up and go’ got up and went.” The Mets might want to win, but even on Father’s Day, even with Brandon Nimmo unleashing his quintessence, their want-to tends to get up and get thrown out at third.

Karma? I wanted to believe the Mets had one more encouraging Father’s Day example hanging from their necktie rack. On June 16, 2013 (which math insists was a full decade ago, but I’m going to ask for an umpire review because, nah, it can’t be ten years already), at home against the Cubs, the Mets were even more moribund than they’d be five years later in Phoenix. The Mets were trailing, 3-0, heading to the ninth. They’d lost three in a row, six of seven, ten of twelve, and were 24-39 overall. Not only were they moribund, you couldn’t imagine they were capable of being bund. Still, they had enough major leaguers and enough want-to on their side to make a Mets fan forget all that for the next half-inning. Marlon Byrd led off with a homer off Carlos Marmol; Lucas Duda walked; John Buck singled; Omar Quintanilla singled both runners up a base; and Kirk Nieuwenhuis ripped a fly ball to deep right that kept going, going…

GONE, GOODBYE! (That’s Kinerese for OUTTA HERE! OUTTA HERE!) Nieuwenhuis had himself a three-run, walkoff home run that set off a bacchanalian celebration at home plate, raised the droll dander of Bob Costas as he showed the highlight during a break in NBC’s U.S. Open golf coverage (“a team fourteen games under .500 celebrates as if it just won the seventh game of the World Series, another indication of the ongoing decline of Western Civilization”), and, for a spell, ignited the hopeless fourth-place Mets to become let’s say somewhat less hopeless. Starting with the Father’s Day comeback and running through almost the next six weeks, the 2013 Mets were bund as hell, going 22-14 and not limiting their joyous days exclusively to Harvey Days.

Kirk’s karma may have been ten years old this Father’s Day, but it came rushing back to me, just as Nieuwenhuis rushed into the line of his waiting teammates at home plate ten years ago (did you know Kirk Nieuwenhuis played high school football?). Maybe I’ve reached a point where I will take anything I can get to make the 2023 Mets more palatable. Usually losing a 5-1 score in the middle of the second would have been enough to elbow aside any optimism for the rest of the game. But if you can’t divine belief that the Mets will do something astounding on Father’s Day, then you haven’t been paying attention for the bulk of the franchise’s life. Sure, Nimmo was thrown out at third, but they’d scored three runs before he got tagged. It was 5-4 with seven innings to go.

Karma!

I was even willing to bring the Braves (ptui!) into it. I’ve stopped paying attention to the Braves where their vast distance from the Mets in the National League East is concerned, but I did notice that they had designated Charlie Culberson for assignment on Sunday. It was reported widely because the Braves had invited Charlie Culberson’s father to throw out the ceremonial first pitch before the game. Instead, they threw out Charlie Culberson. Then, as if karma decided attention must be paid, the Rockies took a 5-0 lead by middle of the second at Truist Park. I could swear something was percolating.

Then again, I’m not a coffee drinker, so how the hell would I know from percolating? Having been brought almost to a level playing field, Carrasco tilted matters back toward the Cardinals in the third, giving up a home run to Paul DeJong, which one could almost overlook since Paul DeJong home runs are proportionally more common to the Citi Field experience than bucket hats given to fans on Bucket Hat Day. Another HBP to the anatomy of McNeil led to another Met run in the bottom of the fourth, by which point Carrasco had exited and John Curtiss had buckled in for the middle relief long haul (two-and-two-thirds). A Jordan Walker solo homer would be the only substantial blemish on Curtiss’s ledger, and it could have been said to have been effectively erased when Tommy Pham answered with a two-run homer off Cardinal reliever Chris Stratton in the fifth. It was 7-7, the Mets had come all the way back, and my lingering suspicion that every Pham RBI is ultimately a mush seemed misplaced. Hot damn, we could win this Father’s Day game!

We could have. Had we, I don’t know that I would have put much stock into what would come thereafter. Thirty-six years ago, the Mets’ inability to make much out of their three-game sweep of the Phillies, cautioned me to be wary of counting on the generation of momentum. With their Father’s Day triumph, the 1987 Mets raised their record five games over .500. Eighteen days later, the 1987 Mets sat four games over .500. That sweep of the Phillies ginned up what turned out to be false hope. Not that I’m dismissing false hope. At this Met moment in 2023, I could use some false hope. I don’t have any other kind for this successor to a team coming off a season of more than a hundred wins.

The 1987 Mets dropped to 92-70 from 108-54 in 1986. It wasn’t the same year the year after. It’s never the same year the year after. The 2023 Mets will not approach the 101-61 record their predecessors achieved in 2022. As Laura Albanese trenchantly observed in Newsday after Saturday’s loss, “Often, guys like Lindor or even manager Buck Showalter will profess optimism that a team so similar to the one that won 101 games last year is just one turning point away from reclaiming its former glory. […] It’s time to put the dream of ‘once things go back to normal’ in the REM cycle. It’s time, too, to act as if the 101-win season was the exception, not the rule.”

A little like remembering that bolts of lightning on a Father’s Day here or a Father’s Day there, let alone a home run by the shortstop on the heels of the birth of a daughter to the shortstop, stand out because they are unusual. The usual with this team is not winning the games that they could win. on Sunday, after the fifth inning, it was business as usual. Curtiss, Dominic Leone, Brooks Raley and David Robertson all pitched credibly, keeping the Cardinals from breaking the 7-7 tie. Robertson needed only eight pitches to put away St. Louis in the eighth. Yet the Mets didn’t do any post-Pham scoring, either, and in the ninth, when Robertson remained fairly fresh, Showalter turned to Adam Ottavino to face the heart of the Redbird order, and the second beat of that heart, Arenado, beat Ottavino with a homer to left, making it 8-7 for the Cards. Maybe Robertson would have faltered, too. Maybe the saving of Robertson for tonight in Houston will pay off. Maybe it was just one pitch by one pitcher going awry and you can say that in any season, even a season like 2022, though we sure didn’t have to say it very much last year.

In the bottom of the ninth, against fireballing Jordan Hicks, Brandon Nimmo expertly dunked a soft liner into shallow left field with one out and Starling Marte coming up. All Marte had to do here was not ground into a double play, and not only would the Mets remain alive, but the next batter would be Lindor. If you were so inclined, you fumbled around for the script you wrote in your head as it pertained to Father’s Day heroics. If the game wasn’t resolved by Big Daddy Francisco on deck, the Polar Bear lurked in the hole. Pete Alonso, escaped from the injured list and doing to Hicks what Arenado did to Ottavino, would make for just as wild an ending as any imagined off the bat of Lindor.

Marte grounded into a double play. Mets lose, 8-7, same score the Mets lost by on June 17, 1962, in the Marv Didn’t Touch First or Second Game. At least there wasn’t a nightcap to lose on June 18, 2023. Meanwhile, as if to tell us karma doesn’t play favorites, the Braves stormed back in Atlanta to crush Colorado, 14-6. Not that you don’t expect that from the Braves. What you don’t expect, as you scan the standings, are so many splendid seasons in progress from so many sources lately transformed from moribund to alive and well. Have you noticed that, roughly ten days shy of the schedule’s midpoint, the Miami Marlins currently own the third-best record in the National League as well as the top NL Wild Card spot? That the Arizona Diamondbacks are first in the National League West? That the Giants have nosed ahead of the Dodgers and that the Dodgers are, if only for the moment, out of the playoff picture? That the Cincinnati Reds have gone from going nowhere to a half-game from first in the NL Central? That the Texas Rangers, a common object of derision when a certain free agent pitcher said he liked the cut of their competitive jib as he departed a 101-61 juggernaut for a 68-94 jugger not, is way ahead of those defending champion Astros in the AL West, and Texas has ascended to its perch without much help from said pitcher?

None among the Marlins, Diamondbacks, Reds and Rangers lost fewer than 88 games last year, and the Giants finished 30 games behind the Dodgers. When I do scan the standings, I have to confess I get an unaffiliated kick out of the uprisings thus far executed by the previously downtrodden. I try not to think that if teams that were “supposed” to lose are winning, it figures that teams that were “supposed” to win are losing, and, unfortunately, that’s a cohort that encompasses us at its core. Reflecting on our shortfalls in years like but not limited to 1987, I told a friend once that we — the Mets and Mets fans — are much better at storming the gates than we are at defending the castle. Sneaking up becomes us. Fending off tends to court disaster. My team has an enormous payroll that I also try not to think about, given that it doesn’t represent currency that can be exchanged for victories. My team also has several players with large reputations built on previous accomplishments, none of which can be translated on demand to doing them or us any good in the present. My team won 101 games last year and clinched a playoff spot with weeks to go; they were universally projected to win a comparable amount and secure even more clinchables this year. That also doesn’t do us any good in the present.

I wouldn’t say I envy the Marlins (ptui!) or any of the other presumed scrappy contenders suddenly establishing a toehold at or the near the top of the divisional and Wild Card standings and becoming less a fleeting phenomenon and more a legitimate contender. But, man, I do miss that feeling from when the Mets would emerge from nowhere and give us a season we didn’t see coming in the good sense. As gratifying as it can be to live up to expectations, it’s an absolute blast to totally exceed them. Had the 2023 Mets been doing what they were “supposed” to do, that would have been fine, too, but expectations never seem to get us where we want to go. This year, they have gotten up and left.

by Jason Fry on 17 June 2023 11:31 pm I don’t like being mad at the Mets.

They’re an important part of my life — while I’m not as doctrinaire about it as I was in the not so distant past, it’s odd for me not to see or hear every pitch, and decidedly rare for a game to go in the books wholly unglimpsed by me. (The last one, though? It was Friday night. Emily and I took my mom out for birthday dinner, and the new Manfred rules meant I returned thinking it would be sixth or seventh only to find out the game had ended 10 minutes or so earlier.)

Being at my station most every day means Brett Baty and Francisco Lindor and Starling Marte and their teammates are near-constant presences in my life, people whose faces and mannerisms I know extremely well despite never having met them in real life. My presumption is that I will like them because they’re wearing the uniform to which I’ve sworn allegiance, and though I know this wouldn’t be particularly true in practice, I choose not to think about that too deeply. When the Mets win they bring me joy and I think better of them, ascribing qualities to them that they may or may not have in real life.

The flip side of this is that when I’m mad at the Mets I am mad at them like they’re family members or dear friends I feel have betrayed me. Which is to say I become volcanically pissed at these young men I imagine I know who are actually total strangers. I scrutinize their failures harshly; I parse their postgame mea culpas like a particularly vengeful prosecutor; I judge their futures with a jaundiced eye and a sneer.

This is not healthy for me. (The actual Mets neither know nor care; the people around them worried about what blogs like ours thought for a brief period some years ago but as far I can tell they no longer do, which is probably better for all involved.) It just makes me stew and shortens my life expectancy. The Mets will be death of me one day, of that I have no doubt — Emily will find me on the couch after another loss waxy of visage and cool to the touch, mouth fixed in an O of despair or outrage, and she’ll say, “Well of course it was the Mets” — but I’d very much like that day to be as far in the future as possible.

This hasn’t been a great year for Mets-induced life expectancy, not with the team determined to be lousy in lots of ways that are grindingly irritating when viewed in contrast to last season, or at least the first 90% of it. But the good news is that I think I’ve let go of all that, or at least some meaningful portion of it, reaching if not acceptance than something reasonably close to it.

Granted, today might come with an asterisk. We kicked off our annual week on Long Beach Island, driving down from Brooklyn and taking possession of our slice of a beach house. With the car disgorged of luggage I figured out how the cable TV worked and found Kodai Senga in trouble against the Cardinals in their baby blue motley. Senga got out of that trouble but then found himself in more of it; while we were buying necessities and booze (OK mostly the latter) at the market in Beach Haven Luis Guillorme, of all people, brought the Mets within a run with a homer. The rest of the game played out with the Mets close on the scoreboard but never particularly feeling like threats; when they lost I sighed and shrugged and we went to dinner.

The experience of a single game may not be as existential as I’ve made things out to be; from the moment Paul Goldschmidt went deep against Senga this game gave off the vibe that it was one of the 50-odd you’re guaranteed to lose in any particular season, notable only for being career win No. 198 for Adam Wainwright, who long ago Ruined Everything.

But the point is that the Mets, barring some reversal of fortune for which there’s zero evidence at presence, are going to lose a fair number more games than 50-odd, and most likely a fair number more games than they and we and various baseball prognosticators thought back in March.

And you know what? That’s OK. I mean, on one level it isn’t, because it means I’ll be sad or PO’ed when I’d rather be happy. But it will be … well, it will be disappointing and not devastating, though I grit my teeth reflexively at putting it that way.

Some years everything your team touches gets sprinkled with pixie dust: The veterans stay healthy, the kids prove precocious and game after game unfolds with every bounce going your way. And some years are the opposite of that. You can’t have one possibility without the other, and, honestly, the not knowing is essential to fandom — there’s nothing less watchable than a guarantee.

The Mets are trying. They’re as baffled as I am that it doesn’t seem to be working, and they’re mad about it too. I’ll watch and listen to them whenever I can and root for them and want to like them, and I’ll try not to get too angry at them when things don’t work out.

It’s acceptance, or at least something close to it. Let’s see how it goes.

by Greg Prince on 17 June 2023 10:51 am In April, it didn’t merit our attention. In April, the Mets were the Mets who were going to make a habit of it. In April, the Mets beat the Padres one game, the A’s the next; the A’s one game, the Dodgers the next; and the Dodgers one game, the Giants the next. In April, the Mets would finish off one opponent, we’d shout “BRING ON THE NEXT VICTIM!” and the Mets would proceed as if they’d heard us.

That was April. This is June. April took place in another season. Before April ended, the Mets stopped beating most comers. In May, most comers took it to the Mets. There was a pause to the new, discouraging pattern in the middle of the month — two wins in a row to close out the Rays, then a sweep of the Guardians directly thereafter — and there were consecutive successful nights spanning a departure from Wrigleyville in Chicago and an arrival in the LoDo section of Denver, but otherwise, the Mets were having trouble holding the court. Somebody else always had next when it came to wins.

From May 27 through June 13, the Mets played fifteen games. They lost eleven of them. Three of the wins came in a row, all against one team, the Phillies. Another, versus the Pirates, floated alone in an ocean of defeats. Entering this season, you wouldn’t have thought you would get to the middle of June and have notice the Mets beat different opponents in back-to-back games only five times. But with the 2023 Mets, you learn to not count on what you were originally thinking.

Going into Friday night’s game, you might have thought the Mets got lucky to have as much as won one game in a row, their most recent, against the Yankees. They tried to sabotage themselves, they really did, but they pulled out Wednesday’s Subway Series finale despite themselves. Or maybe it was left on their doorstep and they had no choice but to pick it up. Whatever. A win was a win, and the Mets had one. So much for the commonly held belief that these Mets were never going to win another game in 2023.

Next inside Citi Field, after a blank day on the schedule, came the Cardinals. EEK! THE CARDINALS!! So much bad juju is associated with the Mets playing the Cardinals. And the existence of the Cardinals in general. If we just go on instinct, we assume the Cardinals have won most of the World Series the Yankees haven’t. Our instincts haven’t heard the Yankees haven’t won (or been in) a World Series since 2009, and that the mighty Cardinals have made a habit of being tripped up in postseasons since conjuring the last of their foolproof devil magic in 2011. We might not have noticed, since we were busy having our championship aspirations elbowed aside by the Padres, that the Cardinals pratfalled even harder versus the Phillies in the Wild Card round last year. We might have forgotten we took five of seven games versus St. Louis last year; it happened early, so our selective memory can be forgiven a little.

The St. Louis Cardinals of 2023 have fallen so far from their usual uppermost branch of the National League tree that even our Mets, struggling to flap their wings on any kind of consistent basis, have to look down to spot them. The Cardinals came into Citi Field with the worst record among all fifteen NL teams. As Gary Cohen reminded us twice during Friday’s telecast — a second time because it bore repeating — the Cardinals hadn’t finished a season with the worst record in the National League since 1918. There were fewer teams then. And a World War.

Yet, because we are Mets fans, we might have believed this was all an enormous setup, because they’re the Cardinals and we’re the Mets, and the Cardinals are forever our default worst-case scenario example, as in “we’ll release him, the Cardinals will sign him, and he’ll win 20 games/a batting title,” as if Jose Oquendo really did make it to Cooperstown. Belief in devil magic was capable of convincing us that the Cardinals would choose this trip to New York to remember that they are the Cardinals; remind us that they have appeared in four consecutive postseasons; and unnerve us with the additional credential that they haven’t missed the playoffs for more than three consecutive seasons in almost thirty years. And then you throw in 1985, 1987, 2006 and whatever individual bête noire that happens to flap to mind the moment you see Redbird red…

EEK! THE CARDINALS!!

But no, not so much at this juncture of 2023. While the Mets have not been very good, the Cardinals have been far more not very good, and they proved it Friday night in what became a quick and easy win for our guys. The Mets jumped on Miles Mikolas for three two-out runs in the first inning. Usually jumping on a pitcher for runs in the first inning implies fewer than two outs have been recorded, but the Mets needed to get a little futility out of their system with a bases-loaded, 1-2-3 double play from Francisco Lindor so we could all think the same thing: Here we go again. Our thinking, however, is consistently faulty this year. Instead of a golden opportunity going horribly tarnished, Brett Baty doubled home two runs, and maybe-not-bad luck charm Tommy Pham drove in another.

That provided a three-run cushion for Tylor Megill, the on again, off again starter who is rarely part of any grand rotational plan, but there he is, every fifth or so day, throwing the ball from the first inning until it becomes abundantly clear he shouldn’t be throwing it any longer. We brace for that moment to reveal itself by maybe the third, probably the fourth, definitely the fifth, and we expect whichever long reliever is tabbed to follow Tylor to have to hold down the deficit Megill has created.

Not Friday. Megill was locked in for the first four innings, negotiated a bit of havoc in the fifth inning, and then more or less sailed through the sixth. One run in six innings on seven strikeouts and no walks. Was Tylor that good or the Cardinals that bad? Did it matter? By the time Big Drip had soaked St. Louis, Lindor had compensated for his DP grounder by driving in a run with a sac fly RBI, and Pham once again brought a runner home. The Mets built a 5-1 lead ahead of Tylor’s final frame, and then made it 6-1 when presumed missing person Daniel Vogelbach reappeared as a DH who could hit, launching a very high home run toward the soft drink sign that glowed in rainbow colors for Pride Night. We could all feel proud as Daniel circled the bases.

Megill gave way to an inning of suddenly reliable righty Dominic Leone and two from emerging lefty option Josh Walker. Neither allowed much of anything to the visitors, and neither kept the hands of time impatiently tapping their fingers. The Mets required all of two hours and one minute to quell the Cards, 6-1. It was just one game, but it was one game we won after another game we won against a different opponent, the first instance of us knocking off a couple of “thems” in succession in three weeks. That the thems in question were the Yankees and the Cardinals can’t help but make the somewhat sustained success a skosh sweeter. There are some opponents against whom we tend to expect the worst. Let us therefore savor a couple of dollops of the best we could hope for.

A win versus somebody.

Then a win versus somebody else.

Who knew they would be such rare treats?

by Greg Prince on 16 June 2023 11:08 am In an unusually clever bit of scheduling, Major League Baseball has sent the St. Louis Cardinals to Queens this weekend to play the New York Mets, 40 years after a player the St. Louis Cardinals sent to Queens began to play for the New York Mets, albeit in Montreal. It was on June 15, 1983, that one of the top Cards in the entire St. Louis deck, Keith Hernandez, was traded to the Mets for Neil Allen and Rick Ownbey. The Mets were off on June 16, so Keith made his Met debut, versus the Expos, on June 17 at Olympic Stadium, going 2-for-4 in a 7-2 Met loss. Met losses were not uncommon in 1983.

After a while, though, they wouldn’t remain the rule.

Not pictured: Keith Hernandez. Not started until late July: fun. On National League Town, the history-conscious podcast I do with my friend Jeff Hysen, we’re devoting a portion of the third episode of each month of the current campaign to a substantive segment on Met seasons and Met ballclubs that are reaching round-numbered anniversaries in 2023. It’s a feature we call IT HAPPENS IN THREES. This month’s three-sided salute is to 1983, and by way of wishing that deceptively successful last-place outfit a happy 40th anniversary, I thought I’d share a textual excerpt from the show, focusing specifically on the Sunday I’ve always considered the pivot point of not only that season, but the decade at large. For the generation of Mets fans who had muddled through the previous six years, the day in question — July 31, 1983 — was not only a blast in the moment, it lives on in memory as the beacon of light that directed us toward better times.

***The 1983 Mets upended their present in the Sunday Banner Day doubleheader that set off this stretch of crackling, competent baseball. Their opponents were the Pirates, in their last throes as a reliable NL East contender. The first inning of the first game was pure 1983 as we’d resigned ourselves to knowing it, with Walt Terrell giving up a single, a single, a walk and, with nowhere to put him, a grand slam to Jason Thompson. Frank Howard removed Terrell, brought in Scott Holman, and hoped for the best…not that the Mets nor their fans had any clue what that looked like. Holman held the Pirates at bay through the fifth, but Pittsburgh extended its lead to 6-1 by the sixth, and the banner parade was poised to be a march of forced frivolity.

Yet in the seventh inning, Mookie Wilson drove in a run, and in the eighth, Keith Hernandez and George Foster delivered back-to-back home runs, setting up a four-run inning that tied the game at six. Jesse Orosco, Neil Allen’s successor as closer and the Mets’ only All-Star earlier in the month, entered to start the ninth and kept pitching as if the banner-wavers weren’t getting antsy to display their works of art. Jesse pitched the ninth. And the tenth. And the eleventh. And the twelfth. And he gave up no runs. Neither did anybody on the Pirates until the bottom of the twelfth, which saw Darryl Strawberry single, second baseman Brian Giles single, utilityman Tucker Ashford walk, and SUPER utilityman Bob Bailor drive in Strawberry with the winning run. Remarkably, the Mets had won after trailing by four after four batters.

More remarkably? It wasn’t the best Met win of the doubleheader.

The Mets celebrated their opener, the fans marched jubilantly — the winning banner proclaimed the Mets “Take a Licking, Keep on Ticking” — and Game Two commenced with Mike Torrez on the mound. Perhaps as if to make up for the TEN walks he issued in Cincinnati a week-and-a-half before, Torrez threw ELEVEN shutout innings in the nightcap. That would indicate the Mets were in extras. Indeed, Torrez was matched inning for inning and zero for zero by Pirate starter Jose DeLeon, who was not only shutting out the Mets, he was no-hitting them. Not until Hubie Brooks singled with one out in the ninth had the Mets pierced the “H” column on the Shea scoreboard…though an instant later, Hernandez erased all that progress on a double play grounder.

Kent Tekulve took over for DeLeon in the tenth and the Mets continued to be stymied. After Torrez gave the last of his all — no Met starting pitcher would EVER again go eleven innings — Frank Howard turned to his Game One workhorse Orosco to keep Game Two going. Jesse shut down Pittsburgh in the top of the twelfth, setting the stage for the bottom of the twelfth, the signature half-inning of the season, and perhaps the overture for the era to come.

Facing Manny Sarmiento, Mookie Wilson singles. Hubie bunts Mookie to second. Chuck Tanner, manager of the Pirates, orders Sarmiento to intentionally walk Hernandez, setting up a double play possibility. It’s possible, but it’s also Mookie out there on second. Beware, Chuck Tanner! George Foster seems to cooperate, with a ground ball to second. Keith is forced, but the man we’ll soon be calling Mex slides hard into shortstop Dale Berra; Foster is running just as hard to first; and Mookie — with third base coach Bobby Valentine’s blessing — is flying toward home. Foster beats Berra’s Hernandez-compromised relay, while Mookie just keeps on comin’.

Wilson is a blur.

The 4-6-3 DP fails to materialize.

Mookie crosses the plate with the winning run in the SECOND twelve-inning win of the afternoon-turned-evening and present-turned-past. The Mets have done more than sweep the Pirates. They have, after being stuck in the same gloomy chapter of their lives since 1977, turned the page toward tomorrow.

The winning pitcher twice was Jesse Orosco, marking the first time a Met pitcher had won two games in one day since Willard Hunter in 1964. Jesse was so pumped that he declared in the postgame euphoria, “I’m ready to pitch a third.” Howard took him up on the offer as best he could. In the 14-game span that had just begun, Orosco would pitch nine times, every occasion a Met victory. Jesse earned five wins and four saves, propelling him toward a third-place finish in the NL Cy Young voting — pretty good for a relief pitcher from a last-place team.

The two weeks that were underway would be chock full of statistical and anecdotal delights. Mookie now had a signature play, and he trotted it out again, against Montreal, three days after the doubleheader. Same deal: Mookie scored from second on a potential double play grounder to win the game. Mookie on the run was already a familiar sight to Mets fans. The entire baseball-loving universe would see the difference Wilson’s wheels could make to a game’s outcome soon enough.

You can listen to the full 1983 segment and entire episode here or on your podcast platform of choice. You are also cordially invited catch up with National League Town’s previous IT HAPPENS IN THREES salutes to 1963 (from this April) and 1973 (from this May).

by Jason Fry on 15 June 2023 12:01 am Given a choice between a bedraggled, ill-mannered win and a jut-jawed, morally inviolate loss, you take the win every time. And the historical record will show that the Mets beat the Yankees Wednesday night, prevailing 4-3 in walkoff fashion in the 10th at Citi Field.

But if you were watching, you know that “win” is stretching it. It’s more like the Mets survived.

Survived, and didn’t exactly calm the troubled waters of their thoroughly roiled season.

The first half of this game was a relatively orderly affair and even a taut one, with former Astro teammates Justin Verlander and Gerrit Cole matching up in an old-fashioned pitchers’ duel that was notable for its contrasts. Cole looked like a classic power pitcher as he went through the Mets’ lineup like a combine, while Verlander inventoried his weapons, found his fastball a little lacking and so turned to the slider, using it and his other breaking pitches to confound the Yankees and condition them so that the fastball, reintroduced late in the proceedings, seemed a tick or two speedier than it was. It was a cerebral performance, one sorely needed, and the former Houstoners’ matchup ended after six with the teams tied at one run each.

And then the Mets commenced to play stupid.

Jeff Brigham walked Josh Donaldson to start the seventh and hit Anthony Rizzo, but then struck out DJ LeMahieu and coaxed a grounder from Isiah Kiner-Falefa, a baseball name I can’t decide whether to classify as wonderful or ridiculous. Rizzo was out at second, but Jeff McNeil made a throw he shouldn’t have made given Kiner-Falefa’s speed and Mark Vientos (who’d made some nice scoops earlier in the game) didn’t make a pickup he should have made, with the end result that a moment later the ball was caroming around on the wrong side of first and Donaldson was trotting home. Kiner-Falefa then stole second, moving to third when Francisco Alvarez threw the ball into center field, and then he stole home on not just Brooks Raley but apparently each and every person employed by the Mets. Seriously, it was like Daniel Murphy really had become invisible out there. At least Raley had the presence of mind to try and drill former Met Billy McKinney, which would have turned the theft into a dead ball, though that didn’t work either: Kiner-Falefa got up dirty and happy while McKinney looked like he wished someone had consulted him about the whole thing.

Down 3-1, the Mets tied the game back up in the eighth on a flurry of Yankee misdeeds: two singles, a walk, a HBP and another single — but Brandon Nimmo short-circuited the inning by inexplicably taking his eye off Vientos as his teammate was rounding third. When Nimmo realized Joey Cora had held Vientos he was basically at the shortstop’s usual address, and wound up making the third out trying to return to second. (Maybe he was safe, but if so no particular injustice was done.)

That was the second day in a row that the usually reliable Nimmo did something boneheaded, though he’s far from alone this year — Steve Gelbs, not exactly a bomb thrower in the criticism department, noted with apparent exasperation on Twitter that the 2022 Mets were known for crisp play and attention to detail, and so far the 2023 Mets are … not known for that.

Still, the game was once again tied and so on the two clubs played, with pretty much every Met fan waiting to see what would go wrong this time. Except that somehow didn’t happen. Adam Ottavino — one of so many Mets following up a terrific season with a thoroughly average one — allowed a leadoff double to Anthony Volpe in the eighth but stranded him, David Robertson worked around a LeMahieu double in the ninth, and Dominic Leone survived a 10th inning confrontation with Giancarlo Stanton. Which led to Nimmo facing Nick Ramirez with one out in the 10th and Eduardo Escobar as the ghost runner.

Nimmo, a man badly in need of redemption, smacked Ramirez’s second pitch off the right-field fence for a walkoff win, winding up crowned with popcorn and drenched in ice water at the center of a scrum of happy (or at least relieved) Mets. Given the outcome — hey, we walked off the Yankees! — I feel bad for noting that Escobar inexplicably stayed all but glued to second instead of going halfway while Nimmo’s drive was in the air, and might have been thrown out at the plate if a couple of Yankee defenders hadn’t made some flawed assumptions of their own.

Escobar wasn’t, though — he slid home safely and the Mets had won. Or at least survived. Close enough.

by Greg Prince on 14 June 2023 1:45 pm The starter can’t hold a four-run lead in the fourth inning.

Two relievers can’t maintain a tie in the sixth inning, and a third reliever is barred from the mound because of sticky hands in the seventh inning.

The center fielder can’t catch a ball lined essentially in front of his glove.

The five-hole hitter strikes out with two on and two out in the sixth, and three on and two out in the eighth, the latter directly after the cleanup hitter strikes out with three on and one out in the eighth.

The manager, whose team is down by one with two out in the ninth, resists the urge to use either of two power hitters to pinch-hit for a light-hitting backup middle infielder who has likely used up his quotient of base hits for the evening.

Can’t pitch.

Can’t catch.

Can’t make contact.

Can’t catch a break.

Can’t make their own breaks.

How’s that for a five-tool team?

Befitting a squad that finds multiple ways to lose, the Mets lost a one-run game to the Yankees at Citi Field on Tuesday night. Don’t be thrown off by the manufactured heat of the Subway Series or the reputation of the intracity rival. Everybody plays everybody, diminishing the impact of anybody playing anybody. Or as Abraham Simpson wrote so eloquently, “Dear Mr. President: There are too many states nowadays. Please eliminate three. I am not a crackpot.”

This loss from Tuesday could have happened against the Pirates or the Braves or the Blue Jays or the Cubs or the Rockies. We know that because in the past several weeks, losses like these have occurred to opponents like those, which is to say everybody who isn’t the Phillies. It doesn’t really matter who the Mets play. It doesn’t really matter what facet of the sport slinks into the spotlight as a result of the Mets not mastering it. Whatever it is a given baseball club has to do to win a given baseball game, doing it to winning effect is something New York’s National Leaguers cleverly avoid.

About the only thing the Mets are doing well these days is saying some version of, “My bad.” Max Scherzer, he whose sliders altogether ceased working in the fourth inning, told reporters, “You can put the camera right on me.” When the camera was put on Francisco Lindor, whose failure to put the ball in the play in the eighth with the bases loaded and less than two out signaled another opportunity was about to be lost, pledged, “I will be better.” Brandon Nimmo, who let a sinking liner baffle him until it fell under his grasp, admitted, “I just missed it.” The Mets are challenging for the league lead in accountability, if nothing else.

While Scherzer wasn’t getting nearly enough outs; Josh Walker (who put a runner on and wild-pitched him forward before Nimmo didn’t make his catch) and Jeff Brigham (who allowed Walker’s Nimmo-facilitated runner to score on a sac fly) weren’t shutting down a key scoring threat; Starling Marte was personally leaving seven runners on base; and Lindor wasn’t doing any better, there was the curious case of Drew Smith. Smith was curious as to why four umpires inspected his right hand and judged it too sticky to let him pitch the seventh, considering, he swore, it was no sticker than it was any other day when he’s been permitted to pitch. It was all sweat and rosin, he said. Scherzer said that, too, when the umps wouldn’t let him pitch in Los Angeles in April, but at least Max had actually pitched some in that game that day. Drew’s in the Tuesday night box score with zero batters faced. He’ll probably be suspended for ten games without the Mets because able to replace him because a) that’s the penalty, unless successfully appealed; and b) that’s the Mets in 2023.

The Mets’ manager in 2022, Buck Showalter, probably made in-game decisions that didn’t work numerous times, but they were easily overlooked because so much he did and his players did went right. In 2023, Showalter isn’t altogether fallible, even in losses. On Tuesday night, the same manager from 2022 made the right call bringing in Dominic Leone to bail out Scherzer, and he made the right call bringing in John Curtiss after Smith was turned around by the men in blue. The calls proved right, in any case, as neither of those down-the-depth chart relievers allowed any runs. Luis Guillorme starting at second can be said to have been the right call, too, in light of the Mets’ Luis singling in the tying run off the Yankees’ Luis (Severino) in the fifth. Our Luis is mostly up here for his defense. Actually, he’s up here because a roster spot opened after Pete Alonso’s bone was bruised. Guillorme hasn’t hit very much since the middle of last year, but his manager exhibited a little trust in an old hand, and Guillorme rewarded him by getting the Mets back even. You didn’t necessarily think getting back even would be on the Mets’ agenda once they jumped Severino for a 5-1 lead, but then along came Scherzer for the fourth, and 5-1 for the homestanders became 6-5 for the interlopers. Guillorme singling in Brett Baty from second made it 6-6. Nimmo not catching Anthony Volpe’s liner — not the easiest ball in the world, but far from Earth’s hardest — facilitated the Mets trailing again, 7-6.

Lindor and Marte’s back-to-back strikeouts versus Clay Holmes in the eighth, leaving the bases loaded as they did, tends to detract from one’s confidence in credentialed hitters. Still, if fatalism hadn’t overtaken your faith, you might have wanted somebody like lefty Daniel Vogelbach to take a crack at righty Michael King when Guillorme was due up as the Mets’ last hope in the ninth. Or, if you didn’t care about experience (or were worried about who was gonna play where in the hypothetical tenth inning of a game in which versatile Eduardo Escobar was burned as a pinch-runner for the unleaden if not unleaded Francisco Alvarez in the eighth), maybe you send up Mark Vientos and roll the dice that his bat has defrosted while he has sat. But Vientos hits about as much as he plays, and Vogelbach is emitting serious 1983 Dave Kingman vibes from the portion of the season when Keith Hernandez rendered his gloomy presence superfluous, except I don’t think we’ve lately traded for Keith Hernandez. When they put the camera right on Vogelbach, he’s in the dugout, and he’s in a warmup jacket that never has a reason to be removed. Daniel was last designated to hit in the middle of the Atlanta series, two series ago. One could ask what he’s doing on the Mets if he’s not asked to do the one thing he was brought to the Mets to do — go to town on righthanded pitching. Even if that town continues to be Doomsville (population Mets), it might be worth a trip to find out.

Or not. It could be I’m just groping for a fifth tool to tear into so my “five tools” construct will stand, however flimsily. I doubt I’m all that upset that neither of the V&V Boys batted for Guillorme. Still, I was pretty sure Guillorme didn’t have another big hit in him, and the moment did have that “do something!” urgency to it. Showalter didn’t do much to make the Mets’ own breaks in that spot, which doesn’t seem like the Buck for whose persona we (certainly I) swooned over last year. He also didn’t say much discernible when he was asked about it in the postgame presser. Perhaps his players and the scoreboard said all that needed to be said.

(Mike Puma has since reported Vogelbach is being granted something of a “mental break,” which might explain why he hasn’t been used at all for five consecutive games.)

Late in the SNY-produced Channel 11 telecast, a clip from The Matt Franco Game was shown. The clip, specifically, the one that explains why the game is universally recognized as The Matt Franco Game. It was from the Shea segment of the 1999 Subway Series, the Saturday game. The bases were loaded. Two were out. The Yankees led, 8-7. Franco was pinch-hitting for rookie Melvin Mora. Gary Cohen’s Hall of Fame play-by-play took it from there.

Now Rivera brings the hands together…runners take a lead at all three bases. One-two to Franco…LINE DRIVE base hit into right field! Henderson scores! Here comes Alfonzo…Here comes O’Neill’s throw to the plate…Alfonzo slides…he’s safe, the Mets win it! THE METS WIN IT! MATT FRANCO WITH A LINE DRIVE SINGLE TO RIGHT AND HE’S BEING MOBBED BY HIS TEAMMATES! Matt Franco, a two-run single off Mariano Rivera in the bottom of the ninth inning, and the Mets win it, nine to eight!

I don’t know how many weeks it required for me to get my full voice back after shouting and screaming and shrieking from almost the top of the Upper Deck at Shea Stadium when The Matt Franco Game went final. Beating the Yankees on July 10, 1999, especially by one run in the bottom of the ninth, was of paramount importance to this Mets fan as life stood that Saturday afternoon. To paraphrase Noah Syndergaard recently on wishing he could pitch he like used to, I would have given my hypothetical first-born to have beaten the Yankees that day.

Twenty-four years later, there was Guillorme, and there was King, and there was a one-run game in the balance, and Guillorme made the last out, my hypothetical offspring were in no danger of being bargained away. I wanted the Mets to win. I wanted the Yankees to lose. It wasn’t urgent urgent from where I sat, so who am I to knock Showalter for not desperately swapping out suboptimal options? Interleague overkill along with substantial personal mileage — fan passion that raged at 36 some nights merely simmers at 60 — can be pointed to for not life & deathing a 7-6 loss for the team I love most to the team I hate most. But mostly, it’s the team I love most not meriting very much voice-raising in 2023.

by Greg Prince on 12 June 2023 12:03 pm It’s a nice enough Sunday, the Mets game from Pittsburgh is on, I’m happy to be tuned in even if I’m only sort of paying attention to the Mets trailing the Pirates. I see Luis Guillorme called out on strikes because he was a second or so late in facing the pitcher with the count one-and-two, a ticky-tack rule rigorously enforced by umpires who don’t want their asses plopped into jackpots. That’s how baseball works in 2023. Get these games over with as soon as possible, every second counts. I’m thinking maybe Luis forgot about these MLB adjustments during his exile to Syracuse, or perhaps his ever-impressive beard inadvertently served as clock-blocker.

Next half-inning, still sort of paying attention, I hear Gary Cohen sum up the defensive changes Buck Showalter has made. Mark Canha is now playing first base, Jeff McNeil is in right field and Guillorme is at second. “Where was Guillorme playing before? Was he at short? At third?” None of that sounded correct. I consulted an in-progress box score. Francisco Lindor was the shortstop all day. He was the DH the day before, but he’s the shortstop every day. Brett Baty I was pretty sure was the third baseman. Yup, still was. Then I divined Guillorme had entered the game the previous half-inning as a pinch-hitter for Mark Vientos and his .167 batting average. You might want somebody to bat for young Mark if your confidence in the kid has sagged sufficiently. But Guillorme? Really? I foggily recalled from a few minutes earlier that the Pirates had made a pitching change, thus Buck must have responded in kind, Guillorme the lefty for Vientos the righty versus whoever the reliever was.

Guillorme as pinch-hitter? I mulled. He was asked to lead off the Mets’ most recent half-inning. In that situation, you just want somebody to find his way on base, so I guess it wasn’t altogether crazy to send up a guy who had hit so little before his mid-May demotion that his bat wasn’t once missed during his absence. It’s not like Luis, recalled on Friday, has never gotten on base. We know he can work counts by fouling off legendary quantities of pitches. He is, as Keith Hernandez likes to intone with assurance, “a veteran”. Luis generally knows what he’s doing. It just didn’t pan out, neither the plate appearance nor the knowing what he’s doing vis-à-vis the pitch clock. A year ago, Luis was a heady, clutch contributor and Buck’s calls were mostly golden.

Me, I was only sort of paying attention. I could complain about what the Mets seem incapable of doing these days, but I seem to have at least temporarily lost my ability to hang on every pitch. Perhaps I should try sweat and rosin to regain my grip. I knew the game was coasting along without much Met success. I knew McNeil had homered. I knew nobody else on our side had done anything remotely like that. I knew Carlos Carrasco didn’t last quite long enough. I knew Josh Walker had gotten out of Carrasco’s jam and further acquitted himself well in the next inning, and that Drew Smith stopped giving up home runs. I knew Andrew McCutchen had collected his 2,000th career hit, and that as long as it didn’t drive home any other Pirate or a lead to any other Pirate driving him home, good for him. I knew Mitch Keller had thrown a gem for however long he threw it, thanks to a) being conscious that Keller is having a heckuva year for the Buccos; and b) being hyperconscious that Keller was the guy who hit Starling Marte last September and effectively shortsheeted our offense for the duration of 2022. It took a second trip through the batting order for me to question if I’d seen Marte in the game. I was certain I would have noticed a Marte-Keller rematch. I checked that in-game box score to confirm…no, Starling had the day off. Like I said, I was sort of paying attention.

I knew we were losing, 2-1. I didn’t know we were going to lose, 2-1, but I rather suspected it, partly because of what I could glean from what I had managed to notice, partly from the tenor of the week-plus that had just passed. The Mets had lost seven in a row, then won one, now were trying to not lose anew. I had written up five of the seven losses. Maybe the cumulative losing had taken a toll on my attention by Sunday, despite the win on Saturday. I delved into Baseball-Reference and determined that since we began Faith and Fear in Flushing, the Mets have lost seven or more in a row seven times: once in 2011 (in April, undermining our confidence at the dawn of what became the Terry Collins Era); once in 2015 (more than a month prior to our salvation via Cespedes); once in 2017 (when things had grown so chippy around here that Jason and I turned off the comments section for the entirety of a road trip); twice in 2018 (an eight-gamer that ran through June 9 and a seven-game version that commenced June 19; fun times); once in 2019 (when I had the rare pleasure of recording for blog posterity each of the seven consecutive defeats); and the one we just endured in 2023. What all those dips into the abyss had in common is we treated them, after it became apparent the losing had reached streak proportions, as if they would never end and, after sucking up as much sucking as we could, acted as if we couldn’t bear to continue paying attention to the team doing the losing. Then a win would occur and attention would be paid, at first sort of, eventually at an extent approaching full engagement. That’s how a blog lasts nineteen seasons and counting. That’s how lifelong fandom earns its adjective.

The longest Met losing streak I ever experienced as a fan was in August of 1982: 15 games. It started while I was winding down the summer interregnum between my freshman and sophomore years of college. It continued during my rushed packing and thousand-odd mile drive south. It didn’t conclude until classes were in session. It was easier in 1982 to no more than sort of pay attention. By the time I was back in school, far from New York in the pre-Internet age, all I had was the next morning’s paper. They lost again. Damn. Oh well. If George Bamberger made a questionable move with a pinch-hitter, it happened without as much as peripheral awareness from me. The 1982 Mets finished in last place, 32 games under .500, 27 games out of first. I was as discouraged as I’d ever been since I’d begun watching, listening to, reading about and obsessing over the Mets in 1969, yet my attention rose to its standard status of full-mast when 1983 rolled around. I was barely older then than this blog is now and had never committed myself to write more than a composition or a book report about the Mets.

The new rules say a pitcher trying to pick a runner off base without himself courting an automatic balk can only disengage twice. I guess it doesn’t hurt for a fan to try it at least once in a while.

After the inning Canha moved to first, McNeil to right and Guillorme to second — none of which mattered, as Brooks Raley walked one and struck out three — Tommy Pham doubled with one out. He was the tying run on base, which was great. Pham doing something of an extra-base nature…I was wary. Pham seems to light it up most in Met losses. Coincidence, I’m sure, but you tend to infer what you begin to sense are trendlets. Another trip to Baseball-Reference is booked to ascertain if Pham the Met hits his best in games that become losses is something akin to a trend or just a figment of the selective imagination.

Pham HRs in Met wins: 2

Pham HRs in Met losses: 4

Pham RBIs in Met wins: 7

Pham RBIs in Met losses: 15

Pham total bases in Met wins: 21

Pham total bases in Met losses: 35

Absolutely coincidental. I’d rather have Tommy Pham getting big hits and take my chances that a teammate will follow in kind than subscribe to voodoo that suggests a Pham double represents a season ticket to Doomsville. Still, it’s kind of eerie. I guess I’ve been paying enough attention to notice Met quirks if not who among Mets is playing in a given inning.

Pham on second, one out, David Bednar pitching. The inning, by the way, is the ninth. It’s the Mets’ last chance. The game has coasted, but now it may be crashing. Gary is telling me how good a closer Bednar is. I actually knew that. I remember he was the Pirates’ lone All-Star last year, a solitary status well-deserved based on what I watched last September when I was paying close attention daily. I may have never seen a more fundamentally lacking ballcub than I did when the Pirates stumbled into Citi Field in 2022. They’ve certainly tightened up their act since then. They’re in first place in their division, and they’ve got a better record than we do, though the latter distinction hardly implies membership within an exclusive society. Bednar, who threw a lot of pitches to get some work in during Friday night’s blowout win for them, has Pham on second. He’s facing Baty, with Canha on deck. Either one would be the right person to knock Pham home. Baty’s run hot and cold, but can’t you picture his game-tying line drive and him landing on first base clapping hard and the Mets dugout going suitably nuts for his having rescued them from a series loss? I could. Alas, it was only in my mind. Baty flied out.

Then Canha, who would have made for a gratifying hero as well. Canha, who got off to a molasses start in this sped-up season, but has begun to produce. Canha, who we know can take it to one of the Pennsylvania teams from the way he beats Philly silly, so why not both (Canha’s BA versus PHI and PIT: .438; Canha’s BA versus all others: .227)? Canha, who had half of the Mets’ hits between the first inning and the eighth inning, a fact I half-recalled from the attention I had sort of paid this game. Canha, who suddenly plays first base much of the time because the Met who plays first base all of the time, Pete Alonso, is unavailable for the immediate future after he absorbed a pitch on the wrist in Atlanta. You just hope the effect of Alonso’s absence this year isn’t akin to the effect of Marte’s absence last year. Hope is one of those elements that is not rules- or health-dependent. You can have all you want, assuming you can generate it in the aftermath of a seven-game losing streak.

I had semi-sincere hope that Canha would come through and drive in Pham. As with Baty, I could picture it happening. A double in the gap, I decided. Pham scores easily. Canha shouting something triumphant while standing on second. Gary declaring that with the Mets down to their last out, it is Mark Canha, the key to their Keystone State fortunes, who keeps them alive, except Gary would declare it better than that because he’s a Hall of Fame broadcaster.

Usually I resist envisioning what’s going to happen because, unlike my hunch about Pham totaling most his bases in Met losses proving accurate, my percentage as prognosticator, particularly as it syncs to the Mets winning, is lower than Mark Vientos’s batting average. Clearing my mind of possibilities is the best way for me to proceed in the ninth inning. Maybe Canha would get that base hit. Maybe he wouldn’t.

He didn’t. The Mets lost, 2-1. They had three hits in total: Canha’s single in the second, McNeil’s homer in the fourth, Pham’s double in the ninth. It was still a nice Sunday. For me, not the Mets. We do lead separate lives sometimes. I left the game on until it became the postgame, I half-listened to Buck frame the Mets’ eighth defeat in their past nine games, though I must confess that I retained none of what he said five seconds after he said it, and then I told my wife, sure, put in the movie. Netflix’s DVD-rental service is going out of business, so we’re trying to watch as many unstreamable titles as we can before they shut it down in September. I’m also trying to watch as many Mets games as I can before the Mets shut it down in September — in case that’s their plan. I tend to make movie time wait on the Mets. I don’t know how long that plan will remain the rule.

Entering the series at PNC Park, I reasoned the Mets were a few games from a playoff spot with 99 games to play, and that’s the bottom line, no matter the sputtering that’s kept them from reaching the sunnier side of that bottom line. It’s three games later. They’re just as far off the pace, though with some extra teams crowding them out of more encouraging positioning. Ninety-six games remain. The Mets are still around. Maybe they’ll start playing better and move up. Maybe they won’t. I look forward to paying attention. Sort of.

by Jason Fry on 10 June 2023 9:33 pm On Saturday afternoon in Pittsburgh the Mets … won a baseball game.

That’s it. They played a baseball game and it ended with more runs for the Mets than their opponents, so they won. That shouldn’t be particularly noteworthy, yet alone breathtaking, yet after the frustrations of Toronto and the horrors of Atlanta and the hungover farce of opening night in Pittsburgh, it felt like quite something indeed.

I watched the game in a vaguely narcoleptic state after getting too much sun in a kayak on the East River, but I registered the details through my self-inflicted haze, from Kodai Senga‘s superb pitching (minus an inexplicable, Leiteresque few minutes where he forgot how to pitch) to Brandon Nimmo supplying excellent defense and the jarring sequence where the Mets’ infield did not, though in fairness the first of their two errors in that frame should have been on the second-base umpire, who misread Luis Guillorme‘s superlatively fast transfer at the front end of an attempted double play as a drop. This time the roof didn’t cave in: The Mets tightened up and got out of the inning with just a single run scoring, leaving the game tied. Which it stayed until the seventh, when the Pirates chose to walk Guillorme so slider specialist Dauri Moreta could go after Mark Canha. I’m easily one of the planet’s Top 100 Guillorme fans, but that didn’t make a whole lot of sense to me; Canha suffered the indignity of a 2-1 slider outside being called a strike but then got one from Moreta without enough break and lashed it up the gap for a double, followed by about 75,000 exhales in the Greater New York area.

The Mets kept going, adding two more runs on a Francisco Alvarez home run and another Canha RBI double, and their relief corps choked out the Pirates without undue trouble, leading to what in happier times might be called a rather ho-hum 5-1 win. This was the kind of game ideal for a baseball nap that erases the middle innings, a mildly pleasant diversion fated not to be thought of again once 28 hours had passed. Which was what the Mets as frustrated players and we as enraged fans sorely needed, what with the humdingers and barnburners all going in the enemy column of late.

It was just a baseball game. The Mets won it. It’s a formula they’re encouraged to repeat.

* * *

In case you didn’t see it, Joel Sherman of the Post got Steve Cohen on the horn to basically ask why he hadn’t unleashed a red wedding on his employees given a frustrating season and its recent nadir.* Cohen’s lengthy ruminations on the subject of how to react when everything goes awry isn’t satisfying if you’re looking for catharsis, but it’s undoubtedly a lot more healthy than what any of us would have done if unwisely empowered to take action after the 13-10 curb-stomping by the Braves or whatever the hell that was Friday night in Pittsburgh. It’s worth reading and thinking about. In case you didn’t see it, Joel Sherman of the Post got Steve Cohen on the horn to basically ask why he hadn’t unleashed a red wedding on his employees given a frustrating season and its recent nadir.* Cohen’s lengthy ruminations on the subject of how to react when everything goes awry isn’t satisfying if you’re looking for catharsis, but it’s undoubtedly a lot more healthy than what any of us would have done if unwisely empowered to take action after the 13-10 curb-stomping by the Braves or whatever the hell that was Friday night in Pittsburgh. It’s worth reading and thinking about.

* * *

Back in 2001, Topps celebrated its 50th anniversary of making baseball cards by unveiling a set called Topps Heritage. It presented 2001’s players on cards based on the 1952 design; Topps has advanced year by year since then, chronologically revisiting each of its original designs for a new crop of players. One’s fondness for Topps Heritage depends on how one views the original design being resurrected: I loved 2013 Heritage because I think 1964 Topps is the pinnacle of its designs and was left cold by 2017 Heritage because I think the 1968 Topps “burlap sack” design is a low point; reasonable people might have the exact opposite point of view.

Topps generally plays things straight with Heritage, but every so often they’ve paid sneaky homage to some aspect of the set that came 50 years before. From a Met fan perspective, the pinnacle of such efforts was 2011 Heritage, which left Met fans complaining that the Mets hadn’t received a team card and a lot of the players were shown hatless in generic-looking uniforms. It fell to baseball-card dorks like me to explain what was going on: Back in 1962 Topps had shown nearly all of the brand-new Mets the same way (a format known in the trade as BHNH, or Big Head No Hat) and skipped a team card; since 2011 Heritage used the ’62 design, Topps was being true to its antecedents. They even went so far as to create a David Wright “error” card listing him with the Reds, in tribute to fellow third baseman Don Zimmer‘s ’62 card that shows him as a Red wearing a Mets hat.

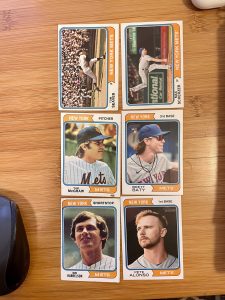

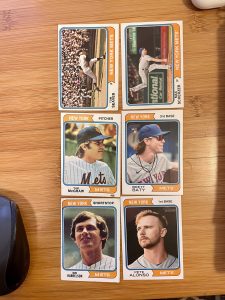

This year’s Heritage set uses the 1974 design, which isn’t particularly a favorite of mine, and I paid the Mets selected no particular heed while obtaining a set. But then I read a fun post noting that cards in the set that echoed those produced the first time around, and got to digging. Sure enough, Topps is up to something with this year’s Mets: Pictured are the ’74 Topps cards for Tom Seaver, Tug McGraw and Bud Harrelson, and the ’23 Heritage cards for Max Scherzer, Brett Baty and Pete Alonso.

Coincidence? Nah — the card numbers even match. Well played, Topps!

* because that was totally the nadir, right?

by Jason Fry on 9 June 2023 11:14 pm

by Greg Prince on 9 June 2023 11:48 am The schedule works out well for the Mets this weekend, positioning them to take advantage of their place in the standings. They are three games out of the third Wild Card spot in the National League and they are in Pittsburgh for three games this weekend to take on the team that it turns out is their target. The Pirates, if you haven’t noticed, are the NL’s six-seed du jour, themselves running two games behind the provisional five-seed Marlins. The situation is fluid, but if the playoffs started today (which they don’t), the Pirates would be in. If the playoffs started today, the Mets would be out.

Way out.

If it seems irrelevant to the point of laughable to invoke playoffs after what we’ve witnessed from the Mets these past three days in particular and seven weeks in general — they’ve been more Jim Mora than Melvin Mora — well, it’s June 9 and 99 games remain in the 2023 season, and if you renew your Mets fandom annually for the long haul of a given baseball season, that’s what they’re giving us. We have a chance to remain invested in the pursuit of a postseason berth. Just not the one we thought would be in our grasp.

The Mets’ participation in the divisional race is essentially over. It’s June 9, and 99 games remain in the 2023 season, yet the Mets have consigned themselves to a different, lesser competitive sphere for the foreseeable future. Granted, in these Air Quality Alert times we can barely foresee down the block, but these Mets have to look up too high to make out their initial goal of first place in the NL East. On a clear day, from where they have mired themselves in fourth, they can no longer see Atlanta.

Thursday night’s finale in their three-game series versus the Braves at Truist Park hinted at what could make the Mets viable for the rest of the year and emphasized all that may very well eliminate them from even semi-serious consolation contention. They did forge a comeback. They did add on. They did exude enthusiasm and, for a while, didn’t say die. They played young and spunky and gave us hope at a hostile locale where fatalism had overtaken our view of what was possible.

Ultimately, though, their fate was to lose, 13-10, in ten innings to the Braves. If this type of loss had come at the hands of any other National League opponent, you’d almost shrug it off as one of those games where each club went to town on the other club’s pitching and the slugfest simply didn’t end the right way. But, no, this wasn’t that. This was horrible Met starting pitching from a source whose excellence was advertised as implicit; horrible Met relieving from everybody asked to get enough outs to help us make it through the night; and, despite the ten runs and fourteen hits and the overcoming of an early 0-3 deficit, horrible offense when it mattered most.

The team that can produce a grand slam — Brandon Nimmo’s — to compensate for their co-ace’s — Justin Verlander’s — staggering shortfall, and slot their hottest shot rookie catcher ever — Francisco Alvarez — as DH and get two home runs from him, and survive, to a point, a night without their biggest bopper (get well, Pete Alonso’s wrist), isn’t without merit. Two hits apiece from McNeil, Lindor and Baty. Three from the slowly awakening Marte. Tommy Pham continuing to make himself something more than useful. No sign of Daniel Vogelbach anywhere except in the dugout where he patted backs and shouted encouragement. Through the tops of five innings, the second through the sixth, mainly at the expense of otherwise able Atlanta starter Spencer Strider, we saw what this team can do and why we expected so much.