The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 2 March 2022 2:09 pm Counterfactually, the Mets are in West Palm Beach today playing the Nationals. It’s not much of a counterfactual to the reality we live in to conclude the Mets would be busy training their spring away a little south of St. Lucie given that the Mets sent out a preliminary Spring Training schedule last August marking FITTEAM Ballpark of the Palm Beaches as their planned whereabouts for March 2, 2022. The same preliminary schedule indicated the Mets were to have played every day since this past Saturday, meaning we would’ve seen them on television at least once; we might’ve heard them on radio; and we would’ve had a satisfying visual, aural and/or anecdotal glimpse of them taking on, for practice purposes, each of their Treasure Coast neighbors.

And we’d be growing sick of the whole thing after five games of the Grapefruit League slate because the Mets would have already been officially preparing for the 2022 season for about two weeks. Pitchers & Catchers & Third Basemen-Outfielders & everybody else would have reported; we’d have all praised their arrival to the highest heavens; and the practices prior to the practice games, too, would have lost their novelty after approximately five days.

Which doesn’t mean we wouldn’t have appreciated the whole Sunshine State spectacle despite its apparent pointlessness, for the point is baked in. By the second day of March — today — we would have had the routine of baseball hammered into us and therefore be set for the year ahead. The key to Spring Training is the repetition of Spring Training, in which weeks and weeks of mostly nothing have to happen in order to prepare us for six months that we collectively concur will be something. That’s what we’re in it for every Spring. We put up with Spring so we can be rewarded with summer and, if we’re lucky, fall.

Yeah, right. Right now, we’re putting up with literal nothingness where Major League Baseball is concerned and we will be for the foreseeable future…though only if we feel ourselves putting up with it. Personally, I feel only a little put out by the news that The Lockout has clamped into institutionality. I would, like any baseball fan, prefer Spring Training to have magically appeared this February and March the way it magically appears every February and March, smoothing the path to Opening Day and the 161 games that, by natural law, are supposed to follow. Instead, The Lockout is the new routine. The owners of the thirty MLB clubs have locked out the players and decided to keep them locked out. Simultaneously, they are locking us out of our previously precious pointless routine and they’ve now confirmed they’ll lock us out of at least the first two series of our season.

Or their season. They view it as their ball. They’ve taken it and gone home. They don’t seem particularly upset about it. Rob Manfred couldn’t be bothered to suppress a grin in announcing the indefinite continuation of The Lockout. At least Bud Selig would have managed to look morose on the heels of frenzied negotiations that ultimately went nowhere. We can either stand around outside the proverbial gates of the Citi Fields of the mind and wonder wistfully when somebody will come along to open the ballpark for us, or we can think about something else. The Lockout makes you shrug. It is designed to make you shrug.

By instinct, I miss Spring Training. I will miss Opening Day for the same reason. I will miss the unfurling of the routine. Maybe the void the owners of the thirty MLB clubs and their hired commissioner have created will grow to a size that will envelop my emotions, and the lack of baseball will get to me and get to me bad. But it hasn’t really happened this time around. I guess I have other things to think about. I guess we all do. The so-called stewards of the sport don’t seem to care if we care, so why should we care? Even my instinct is shrugging.

I still love baseball, by instinct. Instinct carries us through March every March. Until this one. In the counterfactual universe of what we’ve come to routinely expect Spring Training to be, I’d be savoring our March maneuvers — Mets at Nationals today; Marlins at Mets tomorrow; then a weekend versus more Nationals and more Marlins — even as I was growing sick of them. That universe, however, presently sits light years from reality. The Lockout is what MLB has become in reality. MLB can keep its reality.

Call me when the gates reopen. I won’t be standing by.

by Greg Prince on 23 February 2022 4:26 pm Standard numerical milestone acknowledgements aside, the proper anniversary to fondly recall Gary Carter would have been the 8th. Gary Carter wore 8 and, presumably because he wore 8, cherished 8. Marty Noble told a story about visiting Gary Carter’s house during Spring Training and encountering a keypad in order to enter the property. Noble either forgot or didn’t have the five-digit code, so he guessed. He used 8-8-8-8-8. It didn’t work. Then he used four 8s and one other digit. That unlocked the gate.

In an ideal world, we wouldn’t need an anniversary to do this, certainly not the anniversary of a death, which seems antithetical to the enduring image we maintain of a vibrant and upbeat Gary Carter. We would just find ourselves thinking about Gary Carter because he was Gary Carter and take it from there. Yet here we are, in February of 2022, suddenly 10 years beyond the passing of the last Met to catch the final out of a World Series and, as has been the case since February 16, 2012, we find ourselves missing him.

Gary Carter’s Greatest Hits you can replay in your mind for yourself. This isn’t intended as an exhaustive cataloguing of the biggest blows our Hall of Fame catcher struck, rather a stream of consciousness that just happened to yield 8 things that have stayed with us about Gary Carter, 8 things — ups and downs notwithstanding — we still love about Gary Carter.

1. THE KVELLING BEGINS

As offseason gets go, I don’t know if any get the Mets ever got captivated us the way getting Gary Carter did, particularly when you consider the context. It’s the December after the Mets had upped their season win total from 68 in 1983 to 90 in 1984. We’re still high from having competed vigorously in our first full-fledged pennant race in a baseball generation. We’re convinced we’re momentum-fueled, ready to catch and pass the Cubs in 1985. All we need is…

All we need is Gary Carter! If we didn’t think quite so specifically, we were willing to identify the missing piece once it was delivered to us. We didn’t give up nothing, mind you. We gave up our longtime starting third baseman (turned recent shortstop) Hubie Brooks; our promising rookie backstop Mike Fitzgerald; an outfielder who’d hit .407 in a September callup, Herm Winningham; and one of our many talented pitching prospects, Floyd Youmans. Every one of those fellows would contribute to the Expos, yet the trade was a win for the Mets. Ninety wins plus Gary Carter and assorted other additions equaled CAN’T WAIT! for the next four months.

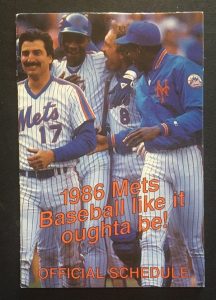

The first season of Gary Carter in New York came exceedingly close to meeting our expectations. The Cardinals replaced the Cubs as our archrivals, and they proved implacable foes, but what a race from Game 1 — which Carter secured with his tenth-inning walkoff home run — to Game 161. Mets fans had never been treated to quite this kind of marathon before, especially those every-fifth-days when it was Gooden pitching to Carter, Hernandez at first and Strawberry in right field. We’d never grouped four players of this nature together at the same time. Now we had them on a regular basis. Them and so many others, but especially them. The Mets grabbed first place early and took it back later, and even if they couldn’t hold on to it all the way to the end, what a ride on this quartet’s collective back it was. No wonder that when we got to Game 162, the only game we entered without a shot at first place, we stood and applauded their season and eagerly craned our necks for a glimpse of 1986.

In 1985, Gary taped his knees, swatted 32 homers, knocked in a hundred runs — right in line with his Canadian exchange rate — and constituted the difference between a team on the come and a team that was just about at its destination. A few smaller pieces would have to be added to make the championship puzzle a perfect fit, but it’s not wrong to consider Carter’s campaign as the pièce de résistance of building blocks once we knew we had something here. You needed a bat like Carter’s to keep climbing in the East. You needed a mitt like Carter’s to catch everything in sight. You needed a storehouse of knowledge like Carter’s to benefit a young pitching staff. Even the slightly older hurlers could benefit. One night in May, he guided Ed Lynch, 29, to his first complete game shutout. Gary being Gary, his instinct was to wrap his arms around his pitcher; Eddie opted for a handshake, as if throwing the best start of his middling career was something he did once a week. “I guess he doesn’t like to give hugs,” Carter said after the game with enough ebullience for the entire battery. “He turned me down. Said, ‘Just shake my hand.’ Eddie’s going low-key on us.”

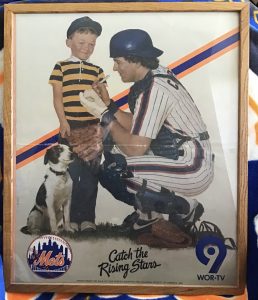

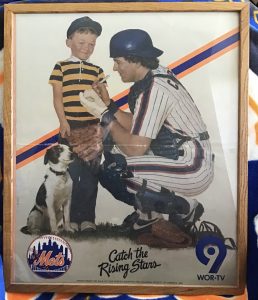

That wasn’t a key Carter struck too often. Mets baseball itself was a pretty convincing advertisement for Shea’s cast of Rising Stars, yet having a face like Carter’s fronting the franchise couldn’t help but raise everybody’s Q rating. Gary’s smile was made for Madison Avenue as much as his game was ideal for Roosevelt Avenue. We loved Keith, but Hernandez could come off as a little dark. We embraced Darryl, but Strawberry was still getting comfortable as a public figure. Dr. K was ready to pitch in the spotlight more than Dwight Gooden was to have it shine on him. Gary Carter was experienced enough and enthusiastic enough to fill the role of Metropolitan Idol. Call that certain something he brought to New York value-added.

We weren’t yet inside the 1985 season when NBC, on its Sportsworld anthology program, attempted to do its part for famine relief by producing its own version of “We Are The World,” except with athletes standing in for singers. One snippet of one chorus was handled by new teammates Gary Carter and Darryl Strawberry, struggling for literal harmony but singing like they meant it on a practice field in St. Petersburg. We weren’t too far into the 1985 season when Channel 9 began offering a poster featuring catcher Gary Carter as a Norman Rockwell-type character, signing a baseball for a little kid and his dog (probably more for the kid than the dog). It was, I think, five bucks, proceeds going to the Leukemia Society of America; Gary had lost his mom to leukemia. In the moment it took me to wonder whether it was odd that somebody who hadn’t been on team for very long was now its literal poster boy, I sent in my check. Like Mets fans everywhere, I couldn’t live without Gary Carter, in whatever form he was available.

When that almost-made-it of a season was over, I came across the briefest of promos for WOR-TV’s premier property. In the middle of November, when we were all missing the Mets, Channel 9 ran a spot of a man leaning against a pillar in the Times Square station looking like he’s got a case of the Mondays. “Need a lift?” the voiceover asks. “Well, just remember.” The next voice belongs to Ralph Kiner: “Going, going, it is gone, goodbye! A three-run homer…” The image that raises the spirits down in the subway is Gary Carter rounding the bases after going deep off none other than Mike Scott (who, at that moment, was just a random Astro who used to be a Met). Our commuter in the commercial is summarily lifted and so are we. “Thanks for the memories, Mets,” the announcer ends it. We are all in on the gratitude en route to winter 1985-1986 when we close our eyes and think about Gary Carter.

2. HE WANTED TO PUMP US UP

Gary Carter was in favor of cleanliness, as evidenced by his ubiquitous commercials for Ivory Soap. Gary Carter wanted you to be conversant in current events and therefore endorsed the selling of Newsday. And when you had to fill up your tank, for the sake of all that was good and holy, please patronize your local Northville Gasoline retailer, just like Gary Carter does.

Perhaps it’s because Northville was a new name in the market in the latter half of the 1980s that Gary Carter for Northville Gasoline is the Gary Carter endorsement I see in the billboard of my mind. You’d see an off brand of fuel here and there, but you just assumed they were fly-by-night. If you really needed gas, you had Amoco, Mobil, Exxon (previously Esso), Sunoco, Texaco, Gulf…you figured you knew the major players. They were the same players who’d been around more or less forever. Then, out of nowhere, there are Northville stations dotting the Long Island landscape, and if we’re not sure they’re viable, we have Gary Carter confirming that they must be OK or he wouldn’t roll his automobile up to one of their islands.

The only other thing I remember about Northville is that Howard Stern custom-read ads for them every morning for a while, which made for strange implicit bedfellows. Howard knew nothing about sports, nothing about baseball, nothing about the Mets, but somehow Gary Carter grabbed his attention. He’d caught enough of Carter’s celebratory clubhouse testimony as the champagne flew in the fall of 1986 to produce a convincing Gary Carter impression. The only other thing I remember about Northville is that Howard Stern custom-read ads for them every morning for a while, which made for strange implicit bedfellows. Howard knew nothing about sports, nothing about baseball, nothing about the Mets, but somehow Gary Carter grabbed his attention. He’d caught enough of Carter’s celebratory clubhouse testimony as the champagne flew in the fall of 1986 to produce a convincing Gary Carter impression.

From K-Rock the morning after the World Series had been won, to the best of my recollection:

ROBIN QUIVERS: Is there anybody you want to thank?

STERN AS CARTER: I want to thank Jesus.

ROBIN: Anybody else?

STERN: I want to thank the Easter Bunny.

Howard was always gonna be Howard and Gary was always gonna be Gary, and even if the two never met as far as I know, well, they both swore by Northville Gasoline. They just swore in different manners. It wouldn’t have been New York in 1986 without either of them.

3. WHAT’S THE ‘BIG’ IDEA?

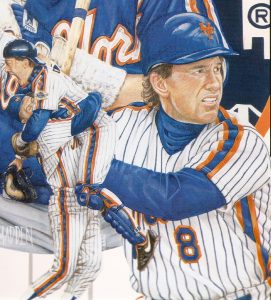

A press invite fell into my hands in August of 1987 for the release of a hot new videocassette: Think Big, a VHS production that would have its coming-out party at Shea Stadium prior to a Mets-Phillies game. Somewhere down the left field line of the Mezzanine concourse, an area was roped off, refreshments were offered and, without fanfare, Gary Carter magically appeared in full uniform. No shin guards, but the pants and the jersey, maybe the cap, if memory serves (it doesn’t always). The PR people didn’t much choreograph his drop-by. He just showed up, dutifully, and a crowd formed around him. I don’t remember if the questions were Think Big-related or standings-related. I was too in awe of the idea that Gary Carter could be bothered to ascend several flights from where he’d soon have business behind the plate and in the six-slot of Davey Johnson’s batting order. Other than filming his street-clothes cameo on a Shea ramp for the Let’s Go Mets music video the previous summer — “go ahead, Doc” — I found it hard to fathom Gary Carter would materialize where regular people gathered. His Think Big co-stars Mookie Wilson and Roger McDowell also made the trip in their game togs, but I spotted Carter before I noticed them, and once you realize you’re standing next to Gary Carter decked out in his Mets uniform, nobody else seems quite so impressive.

Think Big is best described as a motivational tape for kids. In the plot, Gary, Mookie and Roger urged the youngsters to, well, think big. Gary strummed a baseball bat like it was a guitar, approvingly watched from the warning track as a fly ball flew over the outfield fence (it was supposedly hit by one of the kids a few feet away, so it’s not like it added points to one of his pitchers’ ERAs) and dispensed world championship encouragement. “Think about what you’re not doing that you could be doing. ‘Think big’ is like trying to do better than your best,” Kid explains to actual children who are flummoxed by a computer that appears dead-set on ruining baseball…which perhaps indicates how prescient Think Big was. Think Big is best described as a motivational tape for kids. In the plot, Gary, Mookie and Roger urged the youngsters to, well, think big. Gary strummed a baseball bat like it was a guitar, approvingly watched from the warning track as a fly ball flew over the outfield fence (it was supposedly hit by one of the kids a few feet away, so it’s not like it added points to one of his pitchers’ ERAs) and dispensed world championship encouragement. “Think about what you’re not doing that you could be doing. ‘Think big’ is like trying to do better than your best,” Kid explains to actual children who are flummoxed by a computer that appears dead-set on ruining baseball…which perhaps indicates how prescient Think Big was.

There’s also an unfortunate attempt to mimic Pee-wee Herman. By voice, I mean.

Gary carries his burden of being a good example obligingly here, as he did in most of his off-field appearances. I continually got the sense he took his role-modeling seriously, that if he was going to be a superstar ballplayer, a superstar ballplayer owed it to his fans to be what he thought a superstar ballplayer should be. Superstar ballplayer Gary Carter, therefore, is gonna get those kids thinking big. I can’t help but believe that if Gary Carter had been in Revenge of the Nerds, he would have persuaded his fellow jocks to cool it with the taunting and instead put on a clinic down at the local elementary school.

As an accredited journalist, I received a copy of Think Big upon checking in for the event. I brought it home and watched it with my mother. Or tried to. I gave up about five minutes in. My mother got a huge kick out of it. Also, the Mets won that night, 5-3, with Carter going 1-for-3 with a sac fly and guiding Doc Gooden and McDowell through a combined 10-hitter. So, yeah — think big.

4. YOU DO NOT MESS WITH THIS KID

The Gary Carter we got turned 31 just prior to his Met debut. It probably didn’t occur to us how old that was in catcher years. Gary played like it didn’t occur to him either. With all due respect to Think Big, the greatest video production the Mets ever put together was No Surrender, the 1985 highlight film that ran regularly on SportsChannel during rain delays in 1986. It was so enchanting that I rooted for the tarp to remain on the field for at least half-an-hour just to view it again. No Surrender, which was bowdlerized for music rights reasons once SNY’s Mets Yearbook series got ahold of it, was state-of-the-art for MTV-era sports storytelling. Not only did Tim McCarver narrate and not only did it follow the ’85 Mets chronologically (something grand old team highlight films basically never did), but it packed music-video treatment upon music video treatment, clearance fees be damned.

The falling Cubs are shown “No Mercy” in June by both the surging Mets and Nils Lofgren. Keith Hernandez is “The Warrior,” as in Scandal featuring Patty Smyth. Doc gets Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth”: “What a field day for the heat.” Damn. Gary’s winning sequence was scored by “Messin’ With the Kid,” a Blues Brothers track. Not too on the nose, eh? But what made it sing, beyond the title, was the montage. There’s Gary hitting, there’s Gary smiling, there’s Gary politely but firmly giving an earful to an umpire, but mostly there’s Gary catching the hell out of his position.

Two clips stand out:

1) Carter not only blocking the plate and putting a locomotive of a tag on the Pirates’ Doug Frobel, but then pushing him aside with as forceful a go away, kid, you bother me move as W.C. Fields ever managed. Gary doesn’t have time for Frobel. He’s got to look the runner back to first. The play is from the 18-inning game in late April when Gary’s already dealt with one onrushing runner (George Hendrick) and has innings to go before he sleeps. He may have excited because of what he did as a hitter, but we were reminded that day that we had ourselves a catcher.

2) In early June, the Cardinals are running wild, which is a problem for the National League East in general and the Mets most of all. In the third inning of the opener of a Sunday doubleheader at Shea, Vince Coleman steals third and Willie McGee steals second in one fell swoop. This was when it was often said the only gap in young Dwight Gooden’s arsenal was an ability to keep base thieves honest (because he had so few runners to practice holding). Next thing we knew, a ball was getting away from Carter and Coleman decided to bolt for home. Carter, in “Messin With the Kid,” turns into a deli man who comes out from behind the counter to determine who’s causing all this ruckus. With his chest protector as his apron, Mr. Carter grabs that loose ball and chases Coleman all the way back to third. Almost all the way, because veteran Gary in his equipment runs down swift rookie Vince and tags him out.

Warning to baserunners everywhere: you do not mess with this catcher.

5. THEY LIKE EACH OTHER, THEY REALLY LIKE EACH OTHER

Those Mets of Carter and Hernandez if you were going alphabetically, or those Mets of Hernandez and Carter if you were going chronologically, made you care about them beyond their batting or earned run averages. They dripped with personality and they were covered as competitively as they played. The “media” wasn’t a monolith, but all outlets in those days kept extreme tabs on those Mets. Even the junior media.

One Sunday in the summer of 1985, Kidsday, the Newsday section that you’d think was named for Carter but was specifically geared to and more or less produced by children, featured a Q&A with Keith Hernandez. The celebrity Q&As, as interpreted by my friend Fred, usually went something like this:

Q: How are you?

A: I’m really depressed.

Q: What’s your favorite color?

A: Green.

The only specific I remember from the Hernandez interview was the Kidsday staff asking him who were his best friends on the team. Keith named probably at least half-a-dozen Mets, and then, as if he’d realized he’d committed a faux pas, added something to the effect of “I should probably also mention Gary Carter.”

Despite being well out of the Kidsday demographic, I was relieved to have it confirmed that Keith liked Gary, or at least that Keith thought it important to strongly imply he liked Gary. I already assumed Gary liked Keith, because, given all the commercials he did, I figured Gary liked everything. It was important to me that our Veteran Leaders were in sync. I wasn’t naïve enough to believe everybody always liked everybody on my team, but I wanted to believe it. We’d heard that the Expos had had their fill of Carter, but to me that only revealed a deficiency of character on Montreal’s part.

“Camera Carter,” as far as I was concerned, was left north of the border. When, per Noble, George Foster dug up the derogatory nickname while Gary was “doubled over in pain,” his teammates’ reaction was, in essence, “not cool, George.” Noble, writing for Newsday down the stretch in ’85, conceded some of his New York teammates processed Gary’s style as “a little much,” but they “admire his motivation, effort and ability to play despite injury and pain, to say nothing of his talent.”

The vibe remained valid three years later. After he was traded to Minnesota, Wally Backman submitted to an exit interview with Mike Lupica in the Daily News. This was December 1988, the beginning of the end of an era in Flushing. “Gary’s always gonna be a leader in the sense that guys on the team can look up to him,” Backman said, “the way he carries himself on and off the field. Doesn’t matter if you’re a kid or a veteran. I’ve never heard him say a bad word about anybody. He’s just getting older.”

By then, Hernandez and Carter had served a season as co-captains, a year after only Keith wore the C (a letter neither of them wore once they both shared it). It was pretty clear even to a fan reading the papers and listening to pre- and postgame comments that Carter wasn’t crazy about being initially overlooked in 1987. And in his 1993 autobiography The Gamer, he was still a little sore about it. In the moment, to me, Keith was Keith, and Gary came later, so how could Carter argue with Davey’s decision?

“I think Gary may have been a little taken aback by the fact that it was so blatantly obvious who most of the players looked to for leadership,” Mookie Wilson wrote with Erik Sherman in 2014. “Gary may have been the final piece in making us a championship-caliber team, but Mex was our general.”

Yet even in a situation like that, much as when Gary let it be known between the lines he was a little miffed he wasn’t getting more MVP support in 1986; or when he was dropped out of the high-profile cleanup spot; or when he wasn’t a first-, second- or any-ballot Hall of Famer until the sixth time the BBWAA considered his candidacy, I sort of appreciated No. 8 looking out for No. 1. There was an insecurity to Carter that felt palpable from a distance. Maybe it registered as unseemly for such an acknowledged superstar to worry aloud about these ancillary matters, but it was human. Maybe Gary somehow sensed he wouldn’t be around long enough to appreciate the honors that he was sure should have been coming his way. Maybe he had a touch of Billy Joel’s “Big Man on Mulberry Street” in his soul.

“What if nobody finds out who I am?”

6. LONG-TIME IDOL, FIRST-TIME TARGET

Did Gary Carter found WFAN? Not exactly, but he did position himself squarely within the station’s first batch of content. What is sports talk radio if not a forum for debating whether a hometown player is to be venerated or vilified?

Sports talk radio, which had been around in chunks for years, became institutionalized on July 1, 1987, when 1050 AM switched from country music to a format that sounded too good (or bizarre, depending on your perspective) to be true. WHN became WFAN, and WFAN became the home of saying to others what you might have only been saying to yourself all this time. Previously if sports fans wished to be heard by more than a few people at once, they had to buy a ticket to a stadium and express themselves loudly. That’s what had been going on at Shea in 1987. With the Mets having fallen off the pace of 1986, relatively few were in the mood to venerate the defending world champs.

As Jim Lampley, WFAN’s first-ever host, put it shortly after 3 o’clock that afternoon of July 1, “to read the sports sections of this morning’s New York newspapers, you might’ve thought it was October 1,” given the urgency attached to the pennant race the Mets were huffing and puffing to get themselves back into. Patience was less a virtue than missing in action. Gary Carter, he who hit 24 home runs and drove in a team-record 105 runs for the Mets in the regular season the year before — and he who delivered one enormous swing after another in the postseason that certified all of us as champions in our hearts — was getting booed. Not by everybody, but by a vocal percentage of the Shea Stadium throng. On June 29, two nights before the dawn of WFAN, Gary stepped up to the plate in the bottom of the eleventh. The Mets trailed the first-place Cardinals, 8-7, in a Monday Night Baseball showdown that despite transpiring with more than a half-season to go sure as shootin’ felt must-win.

The bases were loaded. There were two out. The Gary Carter of 1985 and 1986 would have conjured a way to at least tie the game and win the crowd. The Gary Carter of 1987 struck out and lost both. Technically, the Mets lost the game as a team, all of them falling 7½ back of the division lead. But the last guy not making contact tends to grab a ballpark’s attention.

In other words, boooooooo.

Two nights later, on the rainy Wednesday night the FAN took flight, the home crowd tried to work out its feelings toward its catcher. In the third inning, after Carter grounded out and left Tim Teufel standing on third, he was booed some more. In the sixth, Carter homered. That rated cheers — and elicited a half-hearted curtain call response from the feistiest fist-pumper who ever took a bow. In the seventh, Carter homered again. Giving the people what they wanted proved popular. More cheers. A heartier curtain call. In the eighth, up for a third consecutive inning, Carter did not homer. He struck out with runners on the corners, but the Mets by then were ahead by four runs. Chastened, perhaps, the fans who remained late through the rain, stood and applauded him.

Carter’s teammates weren’t happy at how he’d been getting treated prior to the home runs. Hernandez: “I could tell he was obviously hurt by it.” Howard Johnson: “You could it tell it bothered him.” The manager believed the fans were spoiled by success, Kid’s and the club’s. “We all know that now that we’ve demonstrated a certain amount of excellence,” Davey Johnson said, “when we don’t give it to them, they’re going to be unhappy.”

Unhappiness wasn’t Gary Carter’s brand, so he put on the best face possible after the 9-6 must-win win (every win was a must in 1987) he personally powered over the Mets’ gleaming new flagship station. “I’d have to say that’s the first time in my career that’s happened,” Carter said. “It’s a case of, ‘What have you done for me lately?’ They have every right to cheer and boo. What it means more than anything else is that they care.” And that memories in New York could be as long as the average length of a phone call to 1 (800) 635-1050.

7. WHEN THE TENT COMES DOWN

The story coming out of the Mets-Braves game in Atlanta on Monday night, May 1, 1989, was Doc Gooden’s left ankle. The mound was muddy, the footing was treacherous and the worry was about a pitcher who slipped. On July 4, 1985, which famously became July 5, 1985, at Fulton County Stadium, Davey Johnson pulled Gooden under dangerous conditions, lest his ace pitcher in the midst of a historic season go into his windup and wind up with an injury.

Not quite four years later, the Mets were cautious but maybe not abundantly so. The ankle (as well as the rest of the pitcher) was brought to the dugout after its muddy mishap in the seventh inning for taping. Satisfied he was good to go, Johnson sent Gooden back to his office to complete a little more business. Doc finished the seventh, started the eighth, gave way to Roger McDowell and picked up his fifth victory versus no defeats in a 3-1 Mets win.

Doc’s ankle would be of tangible concern in the aftermath of Monday night, but Gooden wouldn’t miss his next turn and his pitching looked more than good enough. To the naked eye, the big story of May 1, 1989, would come and go.

The naked eye had no idea what the big story of May 1, 1989, was. The naked eye had to sift through Baseball-Reference after becoming curious decades later regarding a question that crossed the eye’s mind when mulling the magnificence of a Mets team that featured four tentpoles like it never featured before and would never feature again:

When was the last time the Mets started a lineup that was comprised 4/9ths of The Big Four, a.k.a. Gary Carter, Keith Hernandez, Darryl Strawberry and Doc Gooden?

You just read the answer.

I don’t know if anybody else refers to that specific quartet as The Big Four. I’ve never seen it. I never thought it until a couple of years ago. It fits, though. Kid. Mex. Straw. Doc. If the mid-1980s Mets were the marquee, those were the names above it. They were stars. They were superstars. They were megastars. Keep upping the descriptive ante. By reputation, performance and aura, they’d match it.

The Big Four came to be in a box score sense on April 9, 1985, that most magical of Mets Opening Days, Carter’s first game for New York. Gary had been big in Montreal. A big star with a big following (Rue Gary-Carter graces that city’s thoroughfares today). Maybe he wouldn’t be as big in New York in terms of putting up in-his-prime numbers — and maybe New York was too big for a single individual to dominate — but because he was undeniably big in New York, Gary Carter was about to be bigger than ever. Same for Keith Hernandez, a multitime everything in St. Louis, but a celebrity driving in the clutchest of runs in Queens. As for Darryl Strawberry and Dwight Gooden, their limit was the sky when 1985 commenced, and the sky just kept inching higher.

Gary signed with the Mets for five seasons, a time span during which the other components of The Big Four were under contract, so you could say their reign together lasted five seasons. But more granularly, it spanned 79 regular-season games. That’s how many times Davey Johnson submitted a lineup card that was 44.44% covered by…

Hernandez 1B

Strawberry RF (CF a few times)

Carter C

Gooden P

…and, no, wise guy, the rest wasn’t covered by Garry Maddox.

The last time, No. 79, was an occasion that had zero fanfare to it. There was no reason it would. It was barely May. It was a Monday night in Atlanta when a Mets-Braves contest was bereft of inherent hostility. They were in the West. We were in the East. The two clubs hadn’t played a mutually meaningful game since the 1969 playoffs. The schedule called for the Mets to visit Fulton County. The rotation called for Doc to take the ball. The manager didn’t do anything special in writing down Keith’s last name to bat third, Darryl’s to bat fourth and Gary’s to bat seventh. Carter had hit .117 in April, so the seven-spot isn’t as shocking as it might appear if you’re picturing vintage Kid.

Nothing lasting forever probably didn’t need Gary Carter to illustrate its eternal truth, yet the end to something that seemed as if it had just begun was more in sight than we cared to admit heading into 1989. In 1987, he was booed. In 1988, he went three months between home runs, which would have been noteworthy given it was Gary Carter, but turned absolutely painful because the home run that awaited a follow-up was the 299th of Kid’s career and, boy, did he want that 300th. Come the NLCS in ’88, though both Carter and Hernandez each delivered in a couple of key moments, you couldn’t dispute Roger Angell’s assessment, written after the Mets lost the pivotal fifth game en route to losing the series to the Dodgers in seven: “The Mets…looked middle-aged on the field that afternoon and in their clubhouse as well.” At the time, Roger Angell was 68 years old, Carter 34, Hernandez about to turn the same…half of Angell’s longevity to date. The man recognized middle-aged when he saw it. (Roger’s 101 now if that makes you feel any younger.)

When we traded for him, Gary was 30, fluffily curled and coming off one of his best seasons in a career that was stocked with best seasons. For arguably the most significant two-year stretch in franchise history, he was a legitimate differencemaker. You know all those big names the Mets tend to get when the team is at a crossroads and the names proceed to shrink rather than magnify under New York scrutiny? And the crossroads go awry? That wasn’t Carter in 1985 and 1986. He was a new paradigm: the superstar who stayed super helping to lead a good team to monumental greatness. If that’s Gary Carter’s Metropolitan story in toto, that’s fantastic.

It’s not the entire story. The entire story includes a denouement, to put it kindly. The rest of the story, however, despite precipitous statistical declines as he aged past 35, didn’t really dent his Met legacy. Gary Carter in his shrinking-perm stage is no more than ellipsis. Yet if you were there in 1987, 1988 and especially 1989, you couldn’t help but notice Carter’s prime wasn’t what it used to be. But he was still Gary Carter, and now and then there’d be a smattering of success that was straight outta ’85. I can still remember walking into a motel room in Tulsa, Okla., at the end of an August afternoon of business obligations, tossing aside my suit jacket and turning on CNN Headline News to learn that Gary Carter went 4-for-4 in Philadelphia, which tickled me half-a-continent from where I usually got giddy. Any Met going 4-for-4 was good news. Gary entered the day batting .116. That is not a misprint. He ended it batting .152. Also not a misprint. By 1989, you kept wanting to pin numbers like those on erratic typesetting.

Nope, the Mets of Carter and Hernandez and Strawberry and Gooden, even though we hadn’t realized it in May and still didn’t grasp it in August, were over. The next time Gooden pitched after the aforementioned game in Atlanta, Teufel gave Keith a blow at first (a lefty was pitching for Houston). The time after that, Gary’s right knee, unable to bend, was about to nudge him to the DL. Kid had last played May 9. Doc’s next start was May 12. Gooden, throwing to Barry Lyons or Mackey Sasser, went along having a dynamite season until late June, when his right shoulder sent him to the sidelines. Carter was still there. So was Keith, out since the third week in May with a broken right kneecap. Hernandez returned to the lineup on July 13. Carter played again on July 25. Neither was deployed as a regular. Doc’s season, save for a pair of September relief appearances, never regenerated. But he’d be back in 1990. So would Darryl, who skipped the ’89 All-Star Game with a broken toe; honestly, it hadn’t been a very stellar first half for the perennially elected Strawberry.

None of The Big Four was gone altogether from the Mets in 1989, but they no longer composed an elite unit within a juggernaut. It’s not like there hadn’t been a strong bench between 1985 and 1988 should another catcher, first baseman or right fielder have to be called upon; it’s not like the positions that didn’t belong to Carter, Hernandez and Strawberry weren’t manned skillfully; and it’s not like you weren’t getting your innings’ worth out of Darling, Ojeda, Fernandez and so on when Gooden was between starts. But the Big Four was where glamour lived, where excellence thrived, where you most fervently directed your passion.

After May 1, 1989, you never saw it again. Only hair styles can claim to be permanent, and they don’t last either.

Gary’s final turn at bat at Shea as a Met (he somehow willed three more seasons in three more stops from his perpetually barking body) was a thing of beauty, a double struck into the right field corner after he’d taken over behind the plate from Mackey Sasser. He and Keith were permitted last plate appearances in front of what was left of the diehard masses who celebrated their most every move for a few years less than a few years before. Keith’s AB produced a flyout that left his average at .233. Gary’s double raised his to .189. The statistics were hardly the point. The 18,666 in attendance reveled in a proper goodbye.

The Mets, ending their 28th season, had orchestrated few on-field farewells in their history. Maybe when Rusty Staub pinch-hit as 1985’s last batter. Rusty was 41. He probably wasn’t coming back but wouldn’t be definite about it on Closing Day after grounding out on what became the final pitch of his 23-season career. The club held a night for Willie Mays in 1973, and the occasion packed Shea, but (surprise, surprise) M. Donald Grant offered “no support for Willie’s retirement,” according to one of Mays’s advisers, and the planning for what became a star-studded, tear-welling pregame gala was left to Willie’s people. The fans never knew for sure if they were saying goodbye to Seaver or Koosman or Cleon or Buddy as the ’70s unraveled or, for that matter, Mookie or Lenny earlier in 1989. Hell, Joe Torre didn’t find an at-bat for lifetime Met Ed Kranepool in what loomed as Ed Kranepool’s final career home game…on Fan Appreciation Day in 1979.

Carter and Hernandez at least got to tip their caps on the way out and the gesture returned from the stands. They and their deeds had been too big to ignore. Shortly after the schedule played out in Pittsburgh, the co-captains also shared a press conference at Shea. The Mets would be re-signing neither man, but they provided them the space to have their say in the old Jets locker room.

Mex: ”It’s sad because these have been six-and-a-half great years, and I’ll always be a New Yorker and a New York Met. But then come the cold realities. You can’t retire at 65 in baseball.”

Kid: “I can still play this game, and I know there’ll be an opportunity out there. But these have been five great years. I heard the cheers and I heard the boos, and I like the cheers a lot more. Maybe I’ll hear more of them.”

“Privately,” Tom Verducci summed in Newsday, “it was Hernandez who pumped up his teammates and gave the Mets their swagger. but publicly, it was Carter who created the aura of arrogance that the club came to feed on,” an aura that had evaporated as 1989 closed. It was bracing how quickly 1986 had become the past. The Mets had been peeling off their championship players with disturbing alacrity since they let Ray Knight walk and traded Kevin Mitchell to San Diego. With Carter and Hernandez thanked for their service and directed to the exit, the World Series roster of 24 would be almost two-thirds gone by the turn of the decade.

“Somebody will have to lead the Mets into the ’90s,” Keith observed. “And it’s not going to be Gary or me.”

8. FAITH AND KID IN FLUSHING

On December 12, 1984, two days after we discovered who was going to co-lead the Mets for the balance of the ’80s, Gary Carter stood at a podium in the Diamond Club at Shea Stadium and announced, “I’ve saved the ring finger on my right hand for a World Series ring.”

On October 27, 1986, the Mets won the World Series, the last out recorded on a swinging strike three that landed into the mitt of Gary Carter.

On April 7, 1987, Gary Carter was presented with his World Series ring.

On August 12, 2001, the Mets prepared to induct Gary Carter into their Hall of Fame, their first such selection since Keith Hernandez was presented with a sculpted likeness of his own four years earlier. Evocation of 1986 represented a rare bright spot on the premises. Two-Thousand One had been a dreary season to that point. The Mets sat 10½ games out of first place and weren’t a factor in the Wild Card race. They’d recently made three trades subtracting four players — Todd Pratt, Turk Wendell, Dennis Cook and Rick Reed — who had helped them to the postseason in 1999 and 2000. It felt akin to where the Mets had been in 1989, except there was no relatively recent world championship in our rearview mirror. The Mets were still waiting to pick up where they left off when Carter, cradling the sinker Marty Barrett couldn’t touch, embraced Jesse Orosco. It was no wonder that when GM Steve Phillips inserted himself into the Hall festivities, he was vigorously booed. Guest of honor notwithstanding, we were in a bad mood that Sunday afternoon.

Against this sullen backdrop, who could light our world up with his smile? None other than the Kid who made good on a promise of ultimate success once before. I couldn’t see his right finger from where I sat in Mezzanine, but I had to believe it still sported that ring he was determined to win. Against this sullen backdrop, who could light our world up with his smile? None other than the Kid who made good on a promise of ultimate success once before. I couldn’t see his right finger from where I sat in Mezzanine, but I had to believe it still sported that ring he was determined to win.

“Keep cheering for them,” Carter encouraged us as he pointed to the Mets’ dugout. “They’re gonna win another championship. I guarantee it.”

Since he didn’t specify a date, I’m gonna keep believing in Gary Carter.

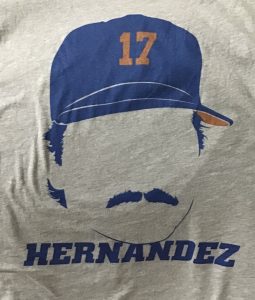

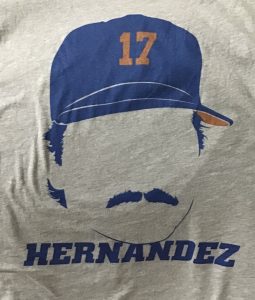

by Greg Prince on 16 February 2022 11:05 am This is a nominally festive occasion. Faith and Fear in Flushing turns 17 today. The team we cover recognized this milestone by announcing they will retire No. 17 this season and reinstate Old Timers Day so the authors of this blog will feel right at home.

All that the Mets and their MLB franchise brethren need to do to make our little celebration complete is some confirmation that there will be a season. My in-box keeps receiving invitations to buy tickets, whether in packages or individually, and I’ve been assured if I pick the right date and show up early enough, I’ll be handed a must-have bobblehead or three, but there’s nothing ever mentioned about the players who might be termed New Timers. No Canha. No Escobar. No Marte. No Scherzer. They seemed so happy to tell me about those fellas when they signed them. Now I’m having a hard time remembering what they were signed to do.

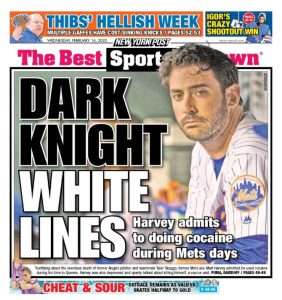

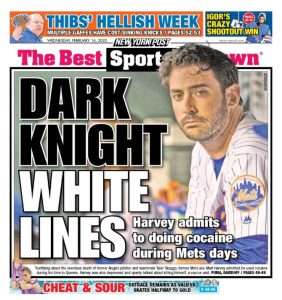

Bad news on the doorstep, indeed. “Bad news on the doorstep,” an American Troubadour once observed of a February that made him shiver. We’ve got a bunch of that in baseball terms and a dollop more in human terms. (When it snows, it pours.) All we can do for Matt Harvey, whose use of cocaine came to light in the trial of Eric Kay regarding the former Angel employee’s culpability in the death of pitcher Tyler Skaggs, is wish him the best where his day-to-day is concerned, particularly after Terry Collins chimed in regarding Harvey’s state of mind back in the day.

All we can do for baseball is wish it gets going.

It’s the middle of February. The wintry afternoons have grown longer. The Super Bowl has completed its brutal business. Those milestones we take as signs of impending Spring with a capital “S” have done their part. Our thumbs, index fingers and middle fingers are clutching our pencils to check the next rite of February off our oh boy! list. Yet the pitchers aren’t throwing to the catchers. The catchers aren’t throwing to the pitchers. The pitchers, the catchers and their colleagues who play the other positions are locked out by the owners and nobody seems to have a clue to the combination of the lock. The jumping-off point for another season of baseball, like the negotiating of a collective bargaining agreement, is stalled. Not a soul has declared he is in the best shape of his life. Thus, the companion occasion that we mark in this space every February 16, the anniversary of the founding of Faith and Fear, is missing a bit of its boisterousness. Maybe more than a bit. Definitely more than a bit. Everything we look forward to as Mets fans…

• the fresh acquisitions loosening up for the first time in orange and blue under the St. Lucie sun;

• the key holdovers making pronouncements about how this year will be better than the last;

• the manager doing things differently than they’ve been done around here and hearing repeatedly why it’s just the tonic this organization has needed for too long;

• every Met’s move being tracked and tweeted as if we can’t survive another second without a handle on how Luis Guillorme’s first ten swings in the cage appeared to the naked eye;

• and we the fans lapping every last bit of it up for at least a quarter-hour until we declare we’re already tired of Spring Training

…isn’t happening.

Boo, obviously.

Nonetheless, it is our anniversary — our seventeenth (the mustache anniversary). Faith and Fear in Flushing commenced to blogging on 2/16/2005 because Jason and I were excited that Pitchers & Catchers & Beltran & all the Mets were arriving in our lives for the next seven or eight months, and we were so excited we simply couldn’t keep our enthusiasm to ourselves. We shared it and just kept sharing it for the next seventeen years. Same for our Met-related dismay, which has tag-teamed with the enthusiasm for seventeen Springs turned seventeen seasons. In the midst of a lockout, we’d probably have to work our way up to dismay from disgust, though disgust has been part of the ongoing discourse as well. Seventeen seasons blogged. Ten losing records. Fourteen MLB postseasons proceeding without Met participation. A little disgust was bound to seep in.

Happy mustache anniversary to us. Yet there is always, at least in theory, one more Spring. One more Spring than seasons, even. Seventeen seasons? Eighteen Springs! We’re back perennially come mid-February regardless of reasons to have been repelled. How many games did the Mets lose last year? Several more than they won. When they were done losing the last of them, we didn’t know precisely who would compose the 2022 Mets, only that eventually we’d bundle up and calculate the number of days until we could informally meet the lot of them. Why am I looking at pictures of Gary Gentry, Doug Sisk and Bobby Parnell in my social media feeds? Because it’s 39 days to Pitchers & Catchers!

The ritual counting down fizzled out weeks ago. The locking out continued. When I turned my officially licensed Mets calendar to February, I was greeted by an image of Taijuan Walker pitching from the stretch. I had to pause and think, a) “Who is that?” and b) “Oh right, Taijuan Walker…man, I have not thought of that guy all winter.” Nothing personal vis-à-vis Taijuan Walker. I’ve barely thought of any active Met since the owners opted to lock out the players. As happy as I am that the Mets have scheduled a number retirement, an alumni reunion and three bobblehead giveaways reflecting the approximate likenesses of their three TV announcers, the current iteration of Mets baseball being out of sight/mind has altogether defierced the urgency of mid-February. And I’ve still not thought much about Taijuan Walker.

***We blogged about 42 players who made up the 2005 Mets in our first season. Last week, that particular team suffered its first brush with mortality with the passing of Gerald Williams from cancer at age 55 (Pedro Feliciano, who died last year, was in Japan in ’05). The Mets had Williams at the end of his career, bringing him onto the club in June of 2004 and recalling him from Norfolk the following summer. Looking at his numbers more or less confirms what I remember about his on-field performance. He batted .233 in each of his partial seasons.

The numbers, however, were only numbers. The person was a different story. It always was with Gerald Williams, even if a fan shaking his head at an outfielder in his late thirties getting 160 plate appearances opted to concentrate on the numbers. “Why is Ice Williams up in this situation? Why is Ice Williams even on this team? What kind of rebuild is this?”

It could be that the people who made personnel decisions — even if there was a case to be made against their judgment based on the period’s broader results — understood a little more what constitutes a team than I did. Gerald Williams, long after his professional peak, was a good guy to have around. When the Mets had better options to start in left, center or right, he filled in around the margins. When the Mets of ’04 and ’05 were strapped for bodies, he was relied on to produce in something resembling the fashion he had from 1992 forward. Sometimes he did. When Carlos Beltran and Mike Cameron slammed into one another in pursuit of a fly ball in San Diego and neither could get back on his proverbial horse before the road trip moved on to Los Angeles, Gerald Williams stepped up for a few days. In one game, he homered, doubled, stole third and brought home an insurance run to support a Jae Seo-Braden Looper combined five-hitter. It was vintage Williams, reminiscent of the seasons when the man whacked as many as 21 homers, drove in as many as 89 runs and was good for as many as 23 steals (Willie Randolph used a pinch-runner ten times in 2005; nine times the runner was Williams).

We might have noticed Gerald when he was one of two Williamses on the youthful Yankees and it wasn’t certain whether he or Bernie was going to be the bigger deal. We surely noticed Gerald when he led off the bottom of the eleventh inning of the sixth game of the 1999 National League Championship Series by doubling off Kenny Rogers…and trotted home minutes later after Rogers threw a dozen balls, intentional and otherwise. If we were tuned into the likes of SportsCenter, we couldn’t miss Gerald and his future Met teammate Pedro Martinez going at it when Williams was a Devil Ray and Martinez was a Red Sock. The pitcher hit the hitter to lead off a game in 2000. The hitter did not take kindly to the free base and a brawl ensued. Gerald Williams experienced a great deal of living and a great deal of baseball by the time he became a Met.

Gerald Williams: more than a .233 hitter. We saw a guy who hit .233 for us and predictably wondered why we couldn’t have somebody with more future in his toolkit. His teammates saw something different. Deep in the FAFIF archives, I rediscovered something I wrote in June of ’05 typical of the modicum of thought I’d given to the value in maintaining a spot for 38-year-old Gerald Williams.

Turns out Gerald Williams is good in the clubhouse. Doug Mientkiewicz said so on Mets Extra, pointing out how Geriatric Gerald was exercising all kinds of great influence on Jose, which obviously paid off in Philadelphia Tuesday night. Well, I thought, maybe that’s worth something, if not an entire roster spot.

Ed Coleman, who likes to agree with whoever’s talking into his microphone, concurred with Minky. “Right,” said Ed. “Last year, Gerald was riding Floyd and Cameron all the time.”

I was glad the Mets, who had been reeling for most of the previous couple of weeks, won. I was glad a connection was discerned between the presence of a veteran and the emergence of a youngster. Jose Reyes recorded two singles and a triple, scored a run and stole a base. The box score indicates all Williams did that night was replace Cliff Floyd on defense in the ninth. Yet I was trying my best to be a realist. Gerald Williams is a guru? That’s great. “So make him a coach,” I concluded.

Maybe they should’ve. Or maybe I didn’t know what I was talking about (wouldn’t have been the last time). The player-to-player dynamic and how it plays out in the short- and long-term is one of those things you likely have to witness to grasp, and even then, you’d only be an observer. The note I made about Ed Coleman remembering Williams’s relationship to his teammates a year earlier came back to me when I read what Mike Cameron, who, like Williams, wouldn’t be a Met after 2005, had to say after Gerald’s death.

“He got me through my first year in New York. He was always so positive. I struggled the first half of that season, but he stayed with me and never let me get frustrated. He was a special guy. He would take care of you as a teammate and give you good advice where to go after a game or where not to go. It’s hard to go out and just perform without a support system and he was one of those guys who provided it. He helped make it easy for you. You really appreciate somebody who does that. […] Especially in places like New York and Boston, you need veteran guys. He made a difference for me, and I know the same is true for a lot of other players.”

I’m seventeen years older than I was in 2005. I’m still working on wiser.

by Greg Prince on 9 February 2022 11:34 am Look at Dan Napoleon

And you might notice

The last name’s the first name

Just like Amos Otis

Like Ed Charles, Frank Thomas

Charlie Neal

Or Kevin Mitchell

But not Rod Kanehl

—Dick McCormack

On May 11, 1969, the New York Mets woke up in as good a situation as they’d ever enjoyed after 28 games: 13-15, a mark they’d reached previously only in 1963, good for third place in the newly carved National League East. Tom Seaver had just beaten the Astros, 3-1, to raise his record to 4-2 and lower his ERA to 2.08. Cleon Jones, having smacked his fifth homer of the young season, lifted his batting average to .402. Historically speaking, even without the benefit of 1969 hindsight soon to come, things were unquestionably looking up.

Yet to Red Foley in the Daily News, not much had changed since 1962. In that Sunday morning’s edition, Foley dwelled on the one constant that hadn’t budged since the Mets’ founding. They were still sorting through third basemen. “For the Mets, who’ve gone from A to Z trying to populate it,” Foley wrote, “third base has been a headache, the kind for which the boys at Excedrin don’t even have a number.”

If you watched enough television in the late 1960s, you got the reference. If you’d watched the Mets during their first decade, you understood the malady Foley was diagnosing. “If there’s a bromide for this lingering cranial pain,” Red elaborated, “you can bet your aspirin that managers Casey Stengel, Wes Westrum and Gil Hodges haven’t heard of it. They’ve tried a total of 40 brands and haven’t gotten to first base, let alone third, in the antidote league.”

Foley went on to giddily list all of the remedies that had purportedly failed, from “that memorable spring evening in St. Louis, when Don Zimmer became the foundation sire for the lengthening line of Met third basemen,” through all those “third basemen who conjure thoughts of those past days and nights when the Mets celebrated rainouts as moral victories” and up to the quartet that had thus far attempted to man third in ’69. “Now,” Foley concluded without giving an inch to the possibility that things maybe were turning a corner, “seven years and 1,163 games after Zim launched the hot corner odyssey, Rusty Garrett, Ed Charles, Amos Otis and Kevin Collins are helping extend the string that for too many has stretched from here to oblivion.”

Forty third basemen in just over seven seasons? Yikes! That sounds like a lot! But was it? Or was it just one of those Met myths that took hold in the earliest days and couldn’t be shaken? Thanks to Baseball-Reference, we can do some comparison shopping. Between 1962 and 1968, spanning all those tenth- and ninth-place finishes, here are how many third basemen each National League franchise employed.

Cubs: 14

Cardinals: 14

Giants: 16

Reds: 17

Pirates: 17

Phillies: 21

Braves: 22

Astros: 27

Dodgers: 27

Mets: 39…with 1969 rookie “Rusty” Garrett (also known as Red, more commonly as Wayne) making it 40

So yeah, the Mets used a lot of third basemen. Certainly a lot more than everybody else. A few amid those growing-pains campaigns were bound to wander in from the outfield.

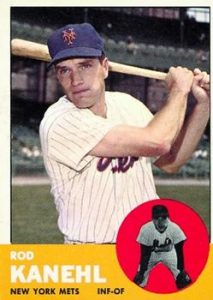

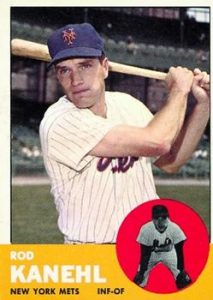

***The first time Casey Stengel gave up on Don Zimmer as his Original third baseman, benching him for six of eight games in late April and early May of 1962, the Ol’ Perfesser turned to Felix Mantilla to start, whether he had conviction about the former Milwaukee Brave or not. Mantilla recalled once having his starting status determined by whether he or Rod Kanehl looked better catching pregame popups hit to them by coach Solly Hemus. “Stengel,” George Vecsey wrote in 1970’s rags-to-riches tale Joy in Mudville, “seemed to have less patience with Mantilla than any other player, once benching him after he made four hits in a game.”

Maybe Casey missed the best the Mets’ first Felix had to offer. According to Mantilla, the legend of the manager maybe not keeping both eyes on every game was more than myth. “People used to ask me if Casey Stengel used to go sleep in the dugout,” the 1961 expansion draftee told journalist Danny Torres in 2019, “and I said that was the truth.” One day versus the Phillies at the Polo Grounds, Mantilla swore innings one through seven went blank on Casey’s scorecard: “The guy was taking a big-time snooze […] God’s truth.”

It’s probably also true that anyone paid to watch the 1962 Mets every night and day might need to briefly escape to dreamland now and then.

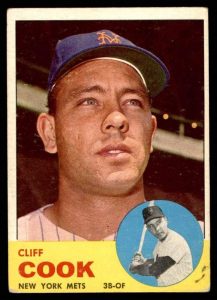

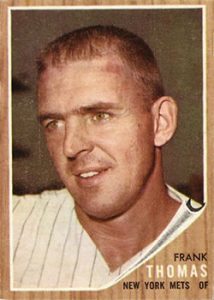

However groggily decisions might have been made sometimes, Casey didn’t fully shut his eyes on what Felix — a man of “lusty good humor” in Vecsey’s estimation — could give him. After the Mets altogether gave up on Zimmer by trading him for Cliff Cook; after Stengel gave up on Cliff Cook by replacing him at third with Frank Thomas; and after Stengel gave up on Thomas as a third baseman and sent Frank back to left field, the manager turned again to Felix Mantilla. Nine Mets in all played third base in 1962. Mantilla was as close to a regular occupant of the Hot Corner as the club could claim. He put in 95 games at third, starting 88 of them and gave the Mets 141 games of baseball in all. The Opening Night shortstop in St. Louis settled in at third as well could be expected, finishing with a solid batting average of .275 and rating sixth among third basemen in double plays turned. It’s an esoteric stat, but considering 120 games were lost, it has to represent a feather in the 1962 Mets’ cap.

At bat, Mantilla was “drilling line drives in every direction,” Vecsey wrote, “but his fielding was a problem. Mets fans liked to imitate him, crouching forward, then rocking back on their hells, waving their left hands casually at the imagined baseball. That was Mantilla playing a hard grounder.”

Perhaps Mantilla, the first Puerto-Rican Met (more than a decade before kids coming upon his name in book’s like Vecsey’s did a double-take and thought, “doesn’t he mean Felix Millan?”) could have found his third base groove and slowed the door already revolving at the position had his services been retained for 1963, but Felix’s strong bat represented enough of a trade chip to land three players from the Red Sox in December of ’62: Tracy Stallard, Al Moran and Pumpsie Green. Two, Moran and Green, were about to become Mets third basemen. But neither was sent to play the outfield. Here in the land of OF-3B/3B-OF, that disqualifies us from saying much more about them.

As we roll like a 38-hopper into the second part of our series on players maybe not playing the position for which they were best suited, we’ve already said more than we planned about Mantilla, who somehow never played outfield as a Met despite seeing 155 games’ worth of action between left, center and right as a Brave, a Red Sock and an Astro in a career that lasted until 1966. He earned a World Series ring for Milwaukee four years before becoming a Met and made the AL All-Star team three years after leaving the Mets. “Mantilla,” Lenny Shecter wrote in his own fond post-1969 look back at the newly crowned champs’ humble beginnings Once Upon the Polo Grounds, “told the world that leaving the Mets was like being ‘pardoned from the electric chair’. He also said that the Mets were the worst team he had ever played on,” professionally or otherwise.

“He may have been right,” Shecter allowed, “but one of the reasons they were so bad was the way Felix Mantilla played the infield.” And Shecter may have been right, but Mantilla, the second player the Mets ever sent up to bat, turned 87 last July. That one year in New York losing all those games certainly didn’t kill him. Perhaps it made him stronger.

Not much strengthened the Mets as they entered their second season, and the third base door continued to spin. Charlie Neal, the primary second baseman from ’62, was tabbed to open the franchise’s sophomore season at third. He didn’t last there or at the Polo Grounds (like Zimmer the year before, he was traded to Cincinnati). Ted Schreiber became the tenth third baseman in Mets history as the Mets were losing their 125th game ever — falling to 0-5 en route to starting 1963 0-8. Ted’s Met highlight would come at year’s end when he grounded into the double play that ended the final National League baseball game the Polo Grounds ever hosted. In between, he’d conclude, “Casey didn’t want me.”

Chico Fernandez, acquired from Milwaukee in May, gave third a brief whirl. Larry Burright put in one inning at third, though Burright admitted in an interview many years later that “I’d never played third base before,” but Casey asked him to, so he tried it (after which, Casey told him, “go pinch-hit for Snider,” despite Burright already being in the game). Moran, mostly a shortstop, had his 3B cameo in May, the same week Ron Hunt commenced to moonlight at third. Hunt’s bright future, however, was mainly at second.

***All of this brings us to the Met Stengel selected to try out at third base in June. He was discovered in the outfield, playing what he usually played. Yet once you’ve gone through 14 would-be third basemen in a little more than eight months of existence, you’re gonna seek solutions wherever they might be found.

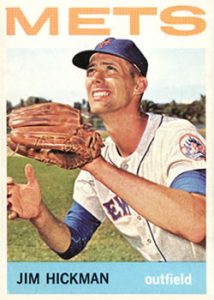

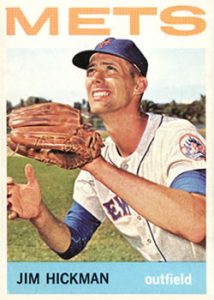

When the Mets chose Jim Hickman in the expansion draft, he had just completed a six-season hitch in the Cardinal chain. From 1957 through 1961, he’d played nothing but the outfield. When he made his major league defensive debut on April 14, 1962, it was in center. Because Opening Night CF Richie Ashburn’s wheels had only so much tread left on them, it would be Hickman who would eventually emerge as the closest thing Stengel could call an everyday starting center fielder. By Baseball-Reference’s reckoning, at no point in the minors nor in the majors entering 1963 had Hickman played third base.

So why not try him there? What did the Mets have to lose? More games? Please. The Mets were 25-42 on June 19 when the OF was first shifted for a couple of frames to 3B. As for Hickman, he was still pretty young (27) and still pretty promising (13 home runs in 1962) if not yet fully formed. Jim led ’62 team with 96 strikeouts, too many of them of the called variety for his manager’s liking. “Oh, you can’t improve your average,” Stengel felt compelled to remind him via ditty (per Vecsey), “with your bat upon your shoulder.”

The Mets improving their record with Hickman upon third base became the idea of the month after the Tennessean tested out the left side of the infield during an in-season exhibition versus their top farm club. “I know some of our players were a little afraid they were going to be left in Buffalo,” Casey cracked about the trip to the shores of Lake Erie. The stopover wasn’t only about maintaining healthy minor league relations and stoking major leaguers’ anxieties. Dana Mozely reported for the Daily News that Hickman “handled everything that came near him flawlessly and revealed a super arm. Everything he threw was a swift strike.”

Mozely may have been breathless in his assessment, but Stengel was circumspect. “I’ll think it out,” Casey said. “I’ve got to try ways to get more long-distance hitting in our lineup. Putting Hickman at third might help. Of course, we don’t know yet how he’ll do when they put on the bat play.” Either “the bat play” has since gone out of style, or Stengel actually said “the bunt play” (time spent with a Newspapers.com subscription indicates Daily News typographers of the day would have fit right in with the 1963 Mets’ defense).

When Stengel became game, Hickman had little choice but to do the same. A stiff upper lip went hand-in-glove with where he was taking his leather. The center fielder from April and May, who detoured to left and right much of June, got his first start at third on July 7. A month later, after he’d produced the first cycle in Mets history, he answered in the affirmative when Newsday’s Stan Isaacs asked him if playing third base was making him a better hitter.

Early Mets had to be on the lookout for someone sending them to play third. “Well,” Jim reasoned, “I have been hitting a lot better in the last couple of weeks. I like third base. It [doesn’t] seem like I get as tired as I do playing the outfield. What takes it out of me in the outfield isn’t the playing, but the running back and forth between innings.” Stengel more or less shook his head at his OF-3B’s thought process: “He wasn’t tired when he knocked in all those runs earlier in the year.” But the Ol’ Perfesser theorized that if Hickman learned to properly shift his feet in the batter’s box, “he can make a living here as a third baseman. We been looking for a third baseman who can hit .260 and knock in 75 runs.”

Roger Craig was looking for anybody at any position to get him a big hit, and two days after Jim singled, doubled, tripled and homered in support of Tracy Stallard, Hickman did his ace pitcher teammate a solid. Craig was riding an eighteen-game losing streak. Good-luck totems fans sent him didn’t help. Counterintuitively switching his uniform number to 13 didn’t help. What — or who — helped was third baseman Jim Hickman lofting a walkoff home run to deliver Craig from a nineteenth consecutive loss. No 3-20 pitcher was ever so happy.

“The first thing I had in mind,” Craig said, “was to make sure he touched home plate. I’d have tackled him to make him do it if I had to.”

Over time, you likely would have had to have tackled Jim Hickman to keep him at third base when the Mets were in the field. Despite his brave words to Isaacs, he wasn’t really cut out to play third, possibly because he was an outfielder. “There are often drawbacks to that type of scenario,” none other than Frank Thomas averred in 2005 when asked to remember his and Hickman’s attempts to convert from the outfield. The numbers Casey wanted out of Jim weren’t there in 1963, with a .229 average and 51 RBIs his final totals. No Met homered more (17), but no Met struck out more (120). Despite not being sent to third regularly until July, Jim made the sixth-most errors in the National League at the position (though, like Mantilla in ’62, he ranked among the league leaders in double plays turned by a third baseman, which perhaps will happen when you play for a team that allows more than its share of baserunners).

More than four decades after Jim Hickman gave third base his best shot, he remembered for Bill Ryczek in The Amazin’ Mets, 1962-1969 that “they stuck me over there and it was tough. Heck, I was half scared to death. I wasn’t a natural third baseman and I just didn’t know what to do over there.” By Spring Training of 1964, Frank Thomas was again being talked up in the papers for third base and Pumpsie Green was getting a long look of his own. Jim moved back to the outfield as the Mets moved into Shea Stadium, and except for occasionally filling in, was done as a third baseman. Before he’d be done as a Met, he’d pile up the most home runs and runs batted in in Mets history — 60 and 210, respectively, over the franchise’s first five seasons, preceding his trade to Los Angeles.

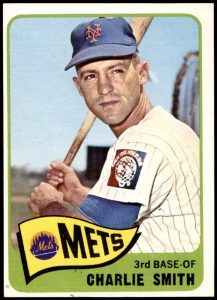

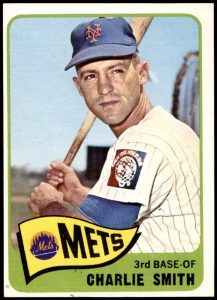

***Once Stengel became certain Hickman wasn’t his third baseman, somebody was going to have to be, and it was neither Thomas (stationed in left or sometimes at first until his trade to Philadelphia in August) nor Green (sent to Buffalo, never to return to New York). Hunt started Opening Night in Philly, but that was a temp job; he’d be back at second before the paint dried at Shea. Rod Kanehl was granted a few starts, but utility demanded Hot Rod stay ready to play anywhere. The answer came in a swap with the White Sox. The Mets sent Chico Fernandez to the South Side in exchange for Charley Smith. Charley didn’t have to convert, at least not by 1964. He’d been a shortstop in the Dodger system before shifting a few yards to his right. Smith had been playing primarily third in the majors since 1961, first for L.A., then Philadelphia, then the Pale Hose.

Card-carrying Charley (or Charlie) Smith gave the Mets a fair shake at 3rd BASE. The man was a pro on a team often accused of being stocked with amateurs. In 1964, Charley socked twenty homers, the most by a Met since Thomas in ’62 (and the most until Tommie Agee in 1969). He also surpassed Hickman for the team strikeout lead and placed fourth in the NL in 3B errors. “Streaky” was how Vecsey described him, and it couldn’t have been surprising that, after hitting fewer homers and striking out even more (123 times) in ’65, Smith would be sent to his fifth club. Charley’s Met legacy, for our purposes, was Topps initiating him as a card-carrying member of the 3B-OF club in 1965. Charley played left field thirteen times in 1964; he played short in seventeen games. Maybe the Topps photographer dropped by Shea on one of those relatively rare LF instances and made sure to tell somebody back at the office that a “3rd BASE-OF” designation was in order. However it happened, Topps didn’t bother to print Smith’s first name in line with his preference. They had him as “Charlie” (then again, this is the same company that kept labeling Roberto Clemente “Bob”).

Smith was traded after the ’65 season with Al Jackson to the Cards for the quintessential “real” third baseman: Ken Boyer, barely a season removed from his MVP campaign for the ’64 Cardinals and with five Gold Gloves in his trophy case. Boyer, 34, was the essence of an accomplished veteran…which basically meant he was old, or at least baseball old. “Shopworn” was Vecsey’s descriptor. The Mets had gone the accomplished veteran route plenty since their founding. This is not to say Ken didn’t give the Mets an honorable year-and-a-half. In 1966, only Ron Santo made more assists among NL third basemen. Maybe the most valuable element Boyer gave the Mets was stability. For the first time, the Mets had a third baseman who finished in the top five in games played at the position…and for the first time, the Mets finished in a place above tenth.

The smattering of accomplished veterans the Mets brought in elevated the Mets to ninth place, but they weren’t long-term solutions. Neither, come to think of it, was the manager who steered them out of the basement. Wes Westrum had replaced Casey Stengel in the summer of ’65 after one of Casey’s 75-year-old hips gave out. Westrum went from interim to permanent to resigned in a little over two years. By the time Boyer was traded to the White Sox on July 22, 1967— and despite both Smith and Boyer having lent third base a hint of dependability for more than three seasons — the all-time meter on Met third basemen was up to 34. Before 1967 ended, by which time Salty Parker briefly replaced Westrum in the dugout and Gil Hodges could be heard driving up from Washington, the count had reached 38. Thirteen of those fellows had also seen outfield action as Mets.

The thirteenth among them would go down as the most misassigned Mets OF-3B yet…and probably ever.

***Time was to reveal that in 1969 the Mets had the exact right platoon to cover third base. They had a veteran, righty-swinging Ed Charles, acquired from the Kansas City Athletics in 1967, two months before Boyer was sent to Chicago. They had a freshman, lefty-batting Wayne Garrett, snatched from the Braves in the 1968 Rule 5 draft. Together, like pairs of Mets at half of the positions Hodges filled in depending on the arm with which the opposing club’s pitcher threw, it worked. The Glider and Red combined to function as a world championship third baseman.

Who’da thunk it? Probably not anybody who’d been watching the Mets for the seven seasons prior to Spring Training of 1969, not even the positive-thinking Hodges. Before it became clear Charles had a year of sheer poetry left in him and that 21-year-old Garrett might be more than prosaic in alternating with the 36-year-old, the Mets thought deeply of turning to another youngster to fill what was still considered their lingering hole.

Meet Amos Otis, the product of what could have gone down as one of the best moves the Mets ever made. On November 29, 1966, the Mets casually plucked young Otis, then a lad of 19, from the Red Sox farm system in the minor league draft. Much as the Orioles took Paul Blair from the Mets in the 1962 draft of first-year pros and then made the Mets regret the oversight while Blair piled up Gold Gloves and postseason appearances, the Mets could have filled the Red Sox with remorse.

In high school, Otis — who like Cleon Jones and Tommie Agee hailed from Mobile, Ala. — had played every position (“I was a jack-of-all-trades”), but primarily shortstop. For the Red Sox, he was tried at first, third, short along with the outfield. As a Met callup late in ’67, he’d get a fleeting glance at third, six days after Joe Moock got his. By 1968, at Triple-A Jacksonville, the Mets used Otis mostly as their center fielder. He flourished in all facets of his game, batting .286, swatting fifteen homers and stealing twenty-one bases.

By the spring of 1969, the Mets were committed to Agee as their center fielder. Agee endured a seasonlong slump in ’68, but Hodges believed in him, so much so that he vehemently disagreed with player personnel director Whitey Herzog’s brainstorm that Agee should move to right to clear space for Otis in center. “Jim McAndrew recalled that was the only time he ever saw Hodges and Herzog argue,” Mort Zachter noted in Gil Hodges: A Hall of Fame Life.

What Hodges believed about Otis, who’d earned All-Star accolades in the previous fall’s Florida Instructional League, was that the youngster could become the third baseman that would hush Red Foley and his army of skeptics. Not necessarily on board with the plan? Otis himself. When asked during Spring Training what was giving him trouble as he tried to learn third, this kid didn’t kid around: “Everything.” The player reasoned the Mets “made me an outfielder. They thought with my speed I’d be more of an asset in the outfield.” Then again, as Jack Lang pointed out in the Sporting News, Hodges was “up to his elbows in outfielders,” with Jones, Agee and Ron Swoboda each already penciled in as starters in March.

Amos Otis with fellow Mobile major leaguers Tommie Aaron, Cleon Jones and Tommie Agee. If only the kid could have stayed in the Shea picture. Otis’s talent, minor league track record and assumed potential at more than one position attracted outside interest. The Braves dangled veteran catcher Joe Torre, a New Yorker with the kind of heavy bat the Mets were always lacking. Atlanta asked for a package of Nolan Ryan, Jerry Grote and Otis. GM Johnny Murphy demurred. “Otis,” he said, “is one of our untouchables.”