The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 1 April 2022 8:39 am For those who instinctively turn their dial to Channel 9 on Saturday afternoons at 2 o’clock expecting Mets baseball, I feel ya. Old habits are hard to break, particularly in a courageous new world. I know the phrase is brave new world, but after five consecutive division titles and a world championship, enough with everything Brave. And I know televisions no longer come with dials. I’m cognizant of what century it is. I don’t have to acknowledge everything about it all the time.

The coming of cable was a good baseball thing in that it meant pretty much every Met game would be televised. The coming of your cable bill was a less good thing, but at least you got what you paid for. In the beginning, there was SportsChannel, which was a name that told you what you were getting, even if it didn’t mention Fran Healy came with it. The later Met melange of Fox Sports Net-New York, which really rolled off the tongue (they shoulda stuck with SportsChannel) and MSG gave way to SNY and GKR, which, despite initial reservations, we’ve enjoyed wholeheartedly since 2006. This longstanding arrangement, give or take some weekends when Gary Cohen takes a break, has been true value in action. Except for those dates nibbled away by Fox or ESPN. Funny how once you didn’t have Vin Scully on NBC or Al Michaels on ABC calling the action, the “honor” of your team being on national TV began to feel like a burden.

Then came games snatched by Facebook and YouTube, which served some alleged purpose that I’ve been slow to grasp, but they were weekday afternoons and if somebody planted behind a desk somewhere was able to sneak peeks they couldn’t otherwise (because not everybody everywhere is an MLB.tv subscriber), well, it’s a weekday afternoon. Baseball happening on a weekday afternoon is gift enough. If its images are not beamed to us directly from Wrigley Field with Ralph Kiner explaining how the winds are blowing out to Waveland Ave., mainlining the Mets by radio oughta suffice.

Nowadays, though? We still have Fox and FS1 depleting the quality of random Saturdays. We still have whatever ESPN will put us through next on select Sundays. TBS’s forthcoming deal for Tuesday nights isn’t exclusive, but they do pull Ron Darling away from Cohen and Keith Hernandez, and that, as we’d say when the Captain didn’t play, ain’t Wright. Now a stream of streaming — exclusive in nature — aspires to prove itself all wet.

Apple TV+ is taking over Friday nights, or at least the games it chooses to devour, commencing with merely what is slated to be, Jacob deGrom’s right shoulder willing, Max Scherzer’s first start as a Met a week from tonight. Wouldn’t you love to hear what our announcers have to say about this historic outing? We’ll have to savor their perspective when it’s offered only in the past tense. Peacock is poised to pluck its share of Met games, too, swooping in on Sunday mornings, as if ESPN doesn’t do enough to denigrate Sunday evenings. (Amazon Prime is also doing something, but it’s something we don’t much care about, so they can leave it out on the front steps.)

I fear the streaming that will have us screaming is Paramount+ having dibs on whichever Thursday night games it chooses, all of which Rob Manfred has mandated must start at 9:30 PM local time, in deference to MLB’s agreement to vigorously promote the sitcom Ghosts, which airs on CBS Thursdays at nine, streaming the next day on, you guessed it, Paramount+. I’ve seen a few episodes of Ghosts. Parts of episodes, really. As network situation comedies in the present day go, it’s no Young Rock, but it’s OK. I’d like it better if it stayed in its lane.

The worst part of the Paramount+ tie-in, which you may have read about if you keep up on these depressing sports media matters, is difficult to choose, because the more you look at it, the worse it gets.

• There’s the late first pitch. West Coast games will stream live starting at 12:30 AM EDT, more like 12:40 once they do all the folderol. Seth Meyers and James Corden, beware.

• There’s the dreaded exclusivity’s impact on the booth. We won’t be hearing from Gary Cohen. We won’t be hearing from Gary Thorne, who did a decent job filling in for his namesake last summer. We won’t be hearing from Gary Apple, even. The Paramount+ announcers will be Ghosts series stars Rose McIver and Utkarsh Ambudkar, calling the games in character as Sam the writer who sees ghosts and Jay her husband who doesn’t, alongside ubiquitous plague on ears everywhere Matt Vasgersian, on loan from MLB Network (I’d prefer the actors). I don’t wish to prejudge, but broadcasting baseball games, regardless of platform, might work better with baseball professionals behind the mic (including Vasgersian, I count none here).

• Then there’s the rules change. Ohmigod, the rules change. If there’s any good news in what they’re doing to the rule book, it’s that this will only apply to these Paramount+ games. The bad news is these games count.

Ghosts runners. Now we’ve seen everything. Unless we can’t see them. You think you hate the concept of ghost runners as we’ve seen it in 2020 and 2021 for extra innings? The same ghost runners we thought we’d be spared from after the lockout, then learned were returning to second base to start the tenth in case of a tie after regulation? You ain’t seen nothing yet. Literally. On these Thursday games that run on Paramount+, we’ll have Ghosts runners. The plural is no accident.

Let’s say Francisco Lindor leads off an inning and doubles. You and I and Buck Showalter may all be satisfied with Lindor’s speed, but Lindor has to be automatically removed for a Ghosts runner, meaning one of the supporting characters from the show will go to second in Francisco’s stead. Sam will see it; Jay won’t; Matt will strain to be sardonic; but the cameras will do the great favor of transmitting it…after first futzing around with some fuzziness because, you got it, they’re ghosts. According to a release from MLB, “the identity of the Ghosts runner will be determined by a special algorithm developed in accordance with the personality of the player who has doubled to lead off an inning (or reached second via a two-base fielding error or any defensive miscue that allows the batter to reach second base before the second batter of the inning steps into the batter’s box to begin the next plate appearance) and how well it meshes with the uproarious cast of Ghosts, which airs on CBS Thursday night at nine and streams the next day on Paramount+.”

That, by the way, is how all announcers employed by Major League Baseball rights holders, local and national, are required to explain the rule in their own broadcasts. So far, our beloved Gare has resisted, and I didn’t hear if Wayne Randazzo succumbed this week in St. Lucie, but watching some other teams’ Spring games on MLBN, I’ve heard the whole mouthful. It should come with mouthwash.

So Lindor won’t be on second. Despite doubling. Despite being Lindor. Despite being under contract to the Mets through 2031. The runner (they don’t pay me to call it “the Ghosts runner” at every turn) could be Trevor or Flower or Alberta or Hetty or Thorfinn or Sasappis or Captain Isaac Higgintoot or Pete. Not Pete Alonso, but Pete Martino — no relation to SNY reporter Andy Martino, as far as I know (Andy thinks this change is “just the shot in the arm baseball needs,” by the way; big surprise). Pete, like the aforementioned, is a character on Ghosts. They are collectively the Ghosts in the show title, the Ghosts who live with Sam and Jay. This is information you didn’t think you’d need to know to follow the Mets this season, but here we are.

Pete, at least, represents the spirit of a Mets fan. Each of the Ghosts has a goofy backstory that works in the context of their sitcom yet has nothing to do with baseball. True, bespectacled Pete was a Mets fan during his pre-Ghosts lifetime, but that doesn’t tell us how well he’ll pick up signs from third base coach Joey Cora (also, he has an arrow lodged in and sticking out his neck). They will be in character and they will appear in costume rather than the uniform of which ever team on whose behalf they spookily materialize. It’s unclear as to whether their names will show up in the official box scores since they’re, well, Ghosts, but the decision to insert them as Ghosts runners is not subject to replay or umpire review.

Even if the given Ghosts have blazing speed — who doubts every one of them will run harder for home than Robinson Cano does to first on a ground ball to second? — there’s no guarantee they’ll score. As you try to wrap your head around this alteration to the tattered remains of what used to be our National Pastime, you might reason there’s never any guarantee that any runner will score from second. Which is fine, except if Captain Isaac Higgintoot (he’s the Ghost who died in the Revolutionary War) doesn’t score, then Lindor in this case or whoever doubled to lead off an inning has to leave the game.

Manfred’s explanation, via MLB’s release:

“Our research indicates ‘desirables’ and other youthful potential baseball-adjacent consumers who are engaged by fantasy, E-Sports and virtual activities will be intrigued by the exclusive opportunity to watch a runner suddenly ‘disappear’ from view, especially when it streams on a platform that requires an additional fee. Thus, any player who reaches second on a fair hit or error to lead off an inning must ‘vanish’ and be replaced by one of the Ghosts, who viewers of all demographics are welcome to watch pull hilarious hijinks every Thursday night at nine on CBS, streaming the next day on Paramount+. The Ghosts runners may have already lost the fight for their own lives, but now they, in conjunction with the team lineups that will attempt to ‘drive them in,’ can battle to keep some of the biggest stars the MLB has to offer in these exclusively streamed games. Truly, this is content in the best sense of the word.”

Gotta love how Manfred is calling his own sport “the MLB” now. And why does he put a baseball term like “drive them in” in quotes? I’m getting the sneaking suspicion Rob Manfred neither likes nor knows that which he commissioners.

Anyway, if the Ghosts runner scores, the hitter stays in the game and goes back to his position for the next half-inning (and is safe from “vanishment banishment” for the rest of the game), but not before McIver, Ambudkar and Vasgersian exclaim, “That’s bed…and breakfast!” Sam and Jay run a B&B on the show, in case you haven’t tuned in. Lest you think the would-be cutesy catchphrase is incidental, think again. Because they’re starting the games so late, Paramount+ and MLB (no the, “Commissioner”) are doing a tie-in with Airbnb. “Getting tired? Next time, reserve more than a room…” Something like that. Aaron Judge and Aaron Boone are supposed to be in the first commercial as “the sharin’ Aarons,” sharing the short-term rental. No doubt that one will run every half-inning of every Mets game Paramount+ hijacks.

Do you believe this nonsense? Do you believe the Players Association agreed to this? The universal designated hitter was bad enough. The extra-inning rule was bad enough. But implementing the Ghosts runner is beyond comprehension. Granted, it’s the reason rosters have been expanded to 28 for the first month of the season, ostensibly in order to give managers more Thursday night flexibility and get used to the vanishing act where leadoff baserunners disappear if their streaming replacements don’t score (Luis Guillorme is advised to stay ready to go in on defense at multiple positions), and that translates to 60 extra temporary jobs and perhaps unlocks a surfeit of service time for the union’s membership, but Tony Clark and whoever else negotiated this wrinkle really should have ironed it out. I already know the owners don’t care. I already know Manfred will allow anything for a buck. I guess the players, already willing to wear advertising on their uniforms (including the Peacock logo suggestively below their belt buckles in those Sunday morning games), aren’t going to make a fuss at this point.

We’re six days from the beginning of the season, but what difference does it make what day it is when Major League Baseball doesn’t give its actual fans a ghost of a chance?

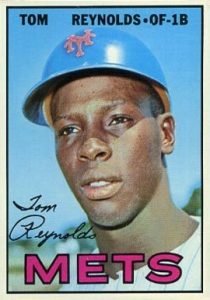

by Greg Prince on 30 March 2022 11:50 am Where do you go after you’ve traded Amos Otis for Joe Foy? Not to the heights of the hot corner, we learned in 1970. As we pick up the thread of our OF-3B/3B-OF series, we shake off the Mets’ decision to swap a promising outfielder who didn’t appear promising at third for a third baseman who didn’t have much left at third, and attempt to reset.

The Mets, as we learned in the first part of this series, practically came into this world eyeing the outfield to solve their genetic third base shortfall. By the end of the second part of this series, we saw that they continued to devote serious consideration to the concept as the 1960s wore on — before entering the ’70s with a bona fide third baseman in tow who didn’t work out. That was Foy, traded to New York for Otis. Otis, as we’ve explored, wasn’t a third baseman, but was a very good player. He was also not a Met when the full discovery regarding his talents was made.

Oh well, said the Mets, back to the drawing board. Having detoured in the third part of this series to the intriguing world of catchers who got caught in the web of OF-3B/3B-OF, we shall return to our drawing board and watch where the quest to spark third base joy after Joe Foy takes the Mets. By 1975, something tells us they’ll be attempting to scale the heights with an uncommonly tall, particularly powerful third-sacker. Or, more specifically, a first baseman-outfielder who will play third base for them.

***Though 1970 was the year it didn’t work out with a veteran 3B, the Mets in 1971 were content to work the same gimmick with a different veteran 3B. Out went Foy, in came Bob Aspromonte. Aspromonte’s “hey, I know something about him” fact is he was the last Brooklyn Dodger to play in the major leagues. The boys one associates with The Boys of Summer were all retired by the 1970s. Even the fellas one doesn’t instantly associate with the legendary squad that left Kings County behind because their biggest moments awaited them in L.A. — your Koufax, your Drysdale, their catcher Roseboro — were done. Aspromonte outlasted them all. The borough native’s Flatbush experience was a single at-bat as an 18-year-old in a 17-2 blowout of the Cardinals in September 1956, but it counted. “My knees were shaking,” he’d recall, but Aspromonte appears in the very same box score as Pee Wee Reese, Duke Snider, Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella and his future manager Gil Hodges, all putting in just another day of work en route to the Hall of Fame. “Gil took me under his wing in the early days when it was tough,” Bob remembered. “You really didn’t belong, but you had to be there.” Fifteen years later, at the tail end of a solid career for the Dodgers, Colt .45s/Astros and Braves, the Lafayette High School graduate came home again, or close to it.

Returning to pretty close to where it all started had been on Aspromonte’s mind for a while. When the deal that sent Ron Herbel to Atlanta to get Bob went down, Newsday’s Tim Moriarty recalled Aspro, then an Astro, pestering some reporters in the Mets’ traveling party around the batting cage in Houston, “When are the Mets going to make that trade and bring me back to New York?” When it finally happened, his manager in Atlanta, Lum Harris, sent him on his way with what amounted to a half-throated endorsement. “Sure he can play,” Harris said of the 32-year-old who’d batted .213 in 1970. “The reason we can let him go is we have Clete Boyer at third base,” which, in 1970 fielding terms, was like saying you had Nolan Arenado at third base. “The Mets don’t have a Clete Boyer at third base, do they?”

No, the Mets didn’t even have Joe Foy at third base anymore, having let him go to the Senators in the Rule 5 draft. They did, as they had since the suddenly distant but eternally golden year of 1969, have Wayne Garrett, but Garrett was scheduled to serve out his National Guard commitment for more than half of the 1971 season. Like the Washington Senators, that’s something that doesn’t enter a lot of contemporary baseball stories these days.

“When one thinks of Sandy Koufax,” Bill Travers wrote in the Daily News on Christmas Eve 1970 in a lament for Lafayette’s athletics department’s budgetary woes, “he thinks of one of the greatest pitchers in history. When one thinks of Bob Aspromonte, he thinks of the new Met third baseman who might cure their hot corner ills.” The shared alma mater of the two old Dodgers (and Fred Wilpon) would eventually get its baseball program back on sound financial footing, as evidenced by the development of future Met closer John Franco. And Koufax would forever be Koufax in every pitching conversation.

Few think of Bob Aspromonte as having cured the Mets’ hot corner ills. After one underwhelming season of Aspro (.225/.285/.301), the Mets moved on. Bob himself retired, ensuring the Brooklyn Dodger presence on active MLB rosters was history. Garrett, having done his Guard stint, was still around, as were a couple of young infielders who’d reported for duty at both third and in the outfield: former overall No. 1 draft choice Tim Foli and the über-useful Teddy Martinez. But whatever awaited on their respective horizons, none flashed the power a team wishes from its third baseman. Among them, in 682 plate appearances, the trio combined for two home runs in 1971 — or four fewer than Clete Boyer hit in 30 games for the Braves.

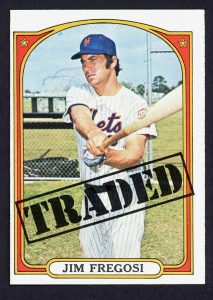

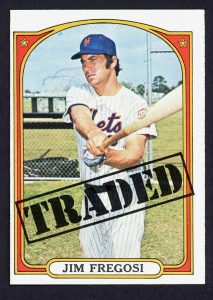

***The Mets instead replaced a veteran named Bob at third base with a veteran named Jim at third base. Except veteran Jim wasn’t really a third baseman or, for that matter, an outfielder. And not really a power hitter, either, having topped 20 homers just once since coming to the majors in 1961. This is where we meet Jim Fregosi, who the Mets acquired from California for that Ryan kid.

Actually, it was that Ryan kid plus three others, as if GM Bob Scheffing wanted to tell the Otis-for-Foy trade, “Hold my beer.”

We know about Nolan Ryan blossoming into the greatest strikeout pitcher of all time about five seconds after leaving the Mets. We know that one of the three others dispatched to the Angels to get Fregosi, outfielder Leroy Stanton, went on to a more than respectable career in the American League. We know Jim Fregosi, the American League’s long-running All-Star shortstop, wasn’t the answer at third base for the Mets during what became an ill-fated Shea stopover of less than two years when:

• he broke a thumb in his first Spring Training;

• he ranked by latter-day metrics as the least valuable defensive third baseman in the National League of his day;

• and he hit fewer home runs in his entire Met tenure than Stanton did in his first year as an Angel.

One could have hoped for the best out of Fregosi, turning 30 and coming off an injury-affected season in Anaheim, but one could look at all that was being given up and wondered what the hell? If you had to trade Ryan and all his potential on the eve of his age-25 season, might you not find a surer thing than an aching shortstop who’d have to learn a new position in a new league? And would you have to throw in three other players to make it happen? Steve Jacobson of Newsday predicted the day after the trade was made, “Unless Fregosi has a very good year, it won’t seem like a fair exchange,” which might explain why Steve Jacobson endured as a top-flight baseball writer into the next century.

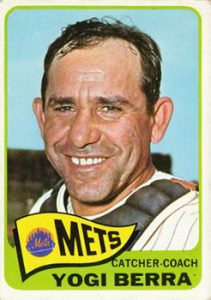

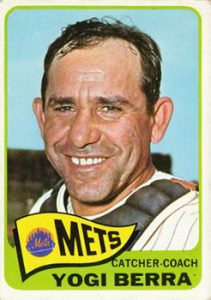

One could have hoped for the best even as one wondered what the hell? Of all the things we know about Ryan-for-Fregosi, are we aware that on June 5, 1973, versus the Reds in Cincinnati, Fregosi took a turn in left field for the Mets? If we didn’t, we do now. Cleon Jones was injured and trying anything that might work topped Yogi Berra’s agenda. Fregosi, carrying a .194 average through the games of June 4, had played left seven times for the Angels, all in 1971, his eleventh season in the majors. It was seven times more than he’d played third base prior to coming to the Mets in 1972.

Fregosi-to-left wasn’t a disaster, which is one of the few contexts for which “it wasn’t a disaster” fits anything related to trading Nolan Ryan for Jim Fregosi. The man started, drove in a run, played into the tenth, and was removed for defense once the Mets took a 5-2 lead (which Tug McGraw and Phil Hennigan proceeded to blow). No balls were hit to him, thus he made no catches, but committed no errors. Not convinced of Jim’s utility, Berra never deployed Fregosi in the outfield again, perhaps because with Bud Harrelson also out hurt, Yogi needed Fregosi to reacquaint himself with shortstop. A month or so later, as neither Fregosi’s presence nor performance still wasn’t letting anyone forget the Nolan Ryan deal, the Mets sold the former star’s contract to Texas…the same franchise for which Nolan Ryan would be pitching twenty years later…when Jim Fregosi was managing the Phillies to the World Series. (Win-win for everybody except the Mets.)

***Garrett, meanwhile, was about to do something the Mets’ front office hadn’t envisioned while it was off collecting and eventually discarding Foy, Aspromonte and Fregosi. He established himself as the everyday third baseman the Mets always needed. Wayne was there all along and now, down the unlikely stretch of 1973, the Mets noticed. From the late-August night the Mets climbed out of the NL East cellar to the October afternoon they clinched their second division title, Garrett slashed .320/.405/.590 and proved himself one of the main reasons the club rushed from worst to first in just over a month’s time. In recognition of his abilities, the Mets left third base alone entering 1974. It was Garrett’s to have; to hold; and, alas, to lose.

Across a full season, Wayne saw his batting average sink more than thirty points, his power numbers regress and his defense, which was more than decent (fourth in the NL in fielding percentage at third, for what that’s worth), not make the case for his continued incumbency. “Let Wayne Garrett play every day and he’ll hit .230,” Fregosi had ruefully predicted when he himself was under fire in New York, overestimating the redhead’s average by six points. Almost as soon as ’74 ended, the Mets made another move for a veteran. Unlike Foy, he knew the National League. Unlike Fregosi, he knew third base. Like Aspromonte, he knew the neighborhood.

It was Brooklyn’s own Joe Torre, forever rumored to be en route in one big trade or another. The haul the Mets sent to St. Louis on October 13, 1974, to secure him at last wasn’t really that big — veteran swingman Ray Sadecki and perennial pitching prospect Tommy Joe Moore — but maybe his bat could be. “Right now, I picture Torre for third base,” Berra said, as if staring straight through Garrett. “He has a couple of good years left.” Torre, as a Brave and a Cardinal in a career that dated back to 1960, had socked 240 homers and driven in 1,110 runs. As recently as 1971, while playing third base for the Cards, he hit .363 and was voted the National League MVP. He didn’t even wait for Spring Training to start playing for Mets. The ballclub was making a goodwill tour of Japan in the autumn the Mets got him, so he went along, put on the uniform and got the folks back home excited ahead of 1975.

One fellow may have been less than enthused. “I’m just going to be a utilityman, I guess,” Garrett, entering his seventh season as a Met, said in Spring Training after an offseason when he saw 1969 teammates Ken Boswell, Duffy Dyer and Tug McGraw get traded. Longevity at Shea was no guarantee of a future.

The thrill of veteran Joe Torre at third base — a position he’d eased away from as he transitioned to first his last couple of years as a Redbird — didn’t last long. Turning 35 in ’75, Joe may not have been the most mobile of third sackers. The pop that once produced 36 homers in a season (mostly as a catcher) fizzled. Torre went deep only six times in his first season as a Met, only once more than Fregosi had in ’72. The overriding memory of Torre as a player at Shea became the game when Felix Millan singled four times, only to find himself forced at second four times because Joe Torre, batting directly behind him, grounded into four consecutive double plays. It set a record.

As 1975, like Torre, wore down, we began to see Garrett, still only 27, rise anew and take starts by the bunch at third; his batting average rose to a career-best .266, as he homered exactly as much as Torre and drove in only one run fewer. We began to see the latest infield phenom from Tidewater, Roy Staiger, who led the International League in RBIs, get a shot. And, most tantalizingly, we began to wonder if something too good to be true could enter the realm of the possible. Might it be that the player who had solved the most glaring offensive void that had plagued the franchise almost since its beginning would also be the player to solve the most glaring defensive void that had plagued the franchise absolutely from its beginning?

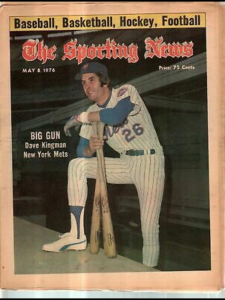

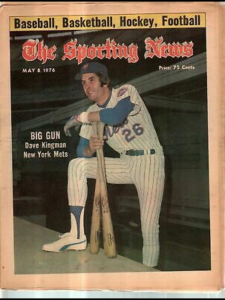

The answer was embodied within six feet and six inches of intermittent thunder that went by the name of Dave Kingman.

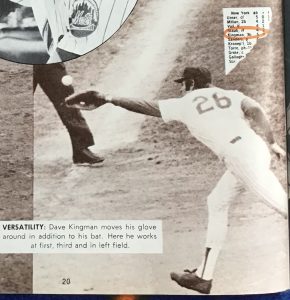

***Dave Kingman loomed as a revelation when the Mets sent a brimming basket of cash to Horace Stoneham in San Francisco in order to obtain Kingman’s services. Kingman, tagged with the “sensitive” label as a Giant, was a bona fide home run threat — which was something no Met had approached being since Frank Thomas swatted 34 in 1962 — and he consistently hit some of the longest home runs anybody had ever seen, even if he was an inconsistent hitter in general. The Mets saw the breathtaking aspect of his game for themselves. In August of his rookie year, 1971, Kingman dinged both the ERA of Jerry Koosman and the roof of a bus parked behind the visitors’ bullpen in left. The Mets won the game and, as the victors, they later got to write the history. In the 1975 yearbook, on the page their new acquisition shared with reliever Jerry Cram, the Mets called that home run “an estimated 500-foot Shea shot”.

Dave Kingman, preparing to play his best position. When that kind of power can be at your disposal and there’s an array of body shops nearby, why wouldn’t you grab yourself some Dave Kingman if all it takes is 150-grand and tolerance for his perceived shortcomings? When they purchased his contract from San Fran early in Spring Training, the Mets appeared set at all the positions 26-year-old Kingman played, having made a passel of offseason moves after trading for Torre, but a big bat was a big bat, even if it had struck out 422 times in 409 big league games. Dave’s gargantuan wood left mouths agape when it took Catfish Hunter deep into what might as well have been the Everglades in one game televised back to New York from Fort Lauderdale. “I’ve never seen one hit further,” swore Mickey Mantle, who hit more than a few pretty far. So, yeah, that stick of Dave’s would stick somewhere.

“If Yogi Berra’s cast were working in the American League,” one wire story mused in late March, “Dave Kingman would be a perfect designated hitter. But the NL doesn’t have the DH, so Kingman has to bring his baseball glove to the ballpark along with his bat. That’s trouble.” Pirate manager Danny Murtaugh’s measured praise was “Kingman has power, he runs and he throws superbly, and that’s what you look for in superstars. Now he’s got to learn to play ball,” a.k.a. defense. Dick Young chimed in, “He is an exciting outfielder, lending the thrill of uncertainty to the pursuit of a fly ball every so often.” His former San Francisco teammate, Mets coach Willie Mays, was more understanding: “He’s happy and that’s the main thing because everything will come then. He’ll hit and he’s willing to play any place. His best position is first, but I told him wait and see” for, among other things, how well Mays might tutor him in the outfield.

Ah, the good old days, when a glove, too, had to find a place to play.

***Yogi brought his team to Shea and let Kingman feel his way on the field. Early on, with Rusty Staub nursing an injury, Dave Kingman took a couple of turns in right and produced two home runs, winning over the crowd as a whole (“I never played anywhere where the fans are so enthusiastic”) and, noticeably, their spiritual leader. Sign Man Karl Ehrhardt brandished a SUPER WHIIFF! placard when Dave struck out, but switched to KONG! in approval of his first Met swat. Rusty soon returned to the lineup and Dave shifted to left, since 1968 the province of Cleon Jones but temporarily vacant while Cleon dealt with his own knee problems. Dave put his third through eighth homers into orbit as the starting left fielder, the position he claimed as his own more days than not.

By June, Sky King — our announcers informed us that if we had to call the 6’ 6” Kingman by nickname, he preferred Sky King to Kong — was occasionally whiling away the gloved portions of his innings at first base, spelling Ed Kranepool and John Milner. Two of the swings he took during that interlude connected for home runs nine and ten. Shea’s air traffic, however, wasn’t exactly drowned out by the cacophony from Sky King’s connections. As June drew to a close, RF-LF-1B Dave Kingman had totaled a respectable eleven homers. It was a pretty good pace Metwise, considering no Met had hit as many as 25 home runs since 1969, but a Mets fan really had to squint to not notice his .219 batting average nor the 47 strikeouts that had piled up.

Come July, there was no missing what Dave Kingman was doing, no matter that some of it was missing the ball altogether at the plate or in the field, for when he did make contact, it was buses beware. Planes, too.

A home run on July 4.

A home run on July 5.

A home run on July 7.

A home run on July 8.

After the All-Star break, a home run on July 17.

A pair of home runs on July 20 — a three-run job to catapult the Mets back into a game they trailed by six and a two-run bomb that sealed a 10-9 comeback win.

Then some more home runs for the mostly left fielder and intermittent first baseman until Kingman finished July with 13 for the month (the Month the National League named him its Player of) and 24 on the season. A year that increasingly couldn’t get out of its own way at Shea — Jones was disgracefully released and Berra was about to get fired — at least contained a potential highlight four at-bats per game. Dave’s batting average soared to .260, which was nice, if not the statistic upon which you dwelled when balls were leaving the yard. His strikeout sum was up to 84, but that we accepted as the cost of doing Sky King business.

***As Dave brought his power to bear, one couldn’t help but be curious about one element of Kingman’s biography. We’d seen him in left and right. We’d seen him at first. What about third? Wasn’t that on his San Francisco résumé? Indeed, between 1972 and 1974, Sky played 140 games at third and hit 36 homers as the Giants’ third baseman, including one off Ray Sadecki at Shea in ’73. He was the Opening Day third baseman at Candlestick the year before he came to the Mets. Yet after April, he rarely set foot near third in ’74, unless it was on his trot from second to home.

Yogi was asked when the Mets purchased Kingman’s contract in Spring Training whether the position the Mets could never solve was a feasible fit now that they were about to harness the thump they’d sorely lacked. “What I saw of him at third base, I don’t like,” Yogi grumbled. A little later in Florida, the skipper reiterated, “He had 26 errors in 20 games at third base,” not quite nailing Kingman’s 1974 defensive record — it was 12 errors in 21 games — but the crux was understood. “First base I don’t like him too much, either.”

What Berra preferred, though, was no longer salient at Shea once he was dismissed in early August. By that same month there was another factor to consider: Mike Vail, hot-hitting rookie outfielder. Vail, who’d led the IL in batting (.342) took over in left, with he and Staub trusted to flank Del Unser. With Vail’s National League rookie record 23-game hitting streak about to unfurl, it appeared Mike would never be dislodged. Rusty around in right was having a dynamite season, heading for 105 RBIs, while Unser stuck close to .300 and provided the best center field defense Shea had seen since Tommie Agee. The outfield was occupied.

At one corner of the infield, Milner was having a horrible, injury-wracked year that would see his batting average plummet beneath .200 and his home runs dwindle to single-digits. Kranepool, despite a renaissance campaign (batting .318 as a starter) found himself reassigned to his customary pinch-hitting duty as the Mets forged a wishful August push toward their third division title. Kingman was suddenly the full-time first baseman — while Torre was less and less the full-time third baseman. Familiar default resort Garrett received some reps at third, as trusty Red inevitably did. Prospect Staiger was given a whirl, too, but young Roy must have forgotten to pack his lumber upon leaving Virginia (he batted .158 after his callup).

Come the middle of September, interim manager Roy McMillan resisted lingering possibility no longer. Dave Kingman, he of the 44 errors in 140 career games at third base, would play third base. At the time he was pointed to the left side of the infield, Dave was sitting on 34 home runs, having knotted Thomas’s previously unassailable 1962 mark. In his fourth game as the Mets starting third baseman, Kingman dislodged Thomas from the record books, an OF-3B taking over for the Original OF-3B…except by the time Kingman came through with No. 35, which happily happened to be the bottom of the ninth for a walkoff win, McMillan had shuffled his personnel and Dave was technically playing first. Sky had one more 1975 homer in him. That Kingman dinger, a solo shot on September 26, unquestionably came as a third baseman. It also came the half-inning after Dave made an error that led to an unearned run that proved the difference in a 4-3 loss. In all, Kingman tried his glove at third in a dozen games and committed three errors…or three times as many home runs as he hit as the Mets’ third baseman.

So maybe an outfielder whose least worst position was first base wasn’t the answer at third, but he did hit 36 home runs, and that pretty much overshadowed all defensive shortcomings, not to mention his 153 strikeouts (making a prophet of Karl Ehrhardt) and .231 average. Sky King was content in Queens. “I’m very happy,” he said late in his first Met season. “I always wondered would happen if I was given the chance to play regularly. I feel I’ve improved in a number of areas because I’ve been given that chance.”

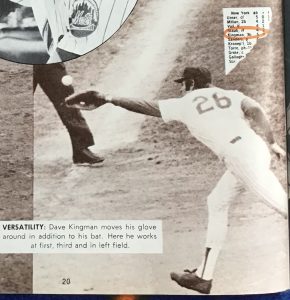

He tried. When the 1976 yearbook came out, three-quarters of Kingman’s bio and stat page, graphically speaking, was devoted to Kingman’s defense. There were pictures of him — with scraps of box scores serving as additional evidence — playing some first, some left and some third. “VERSATILITY,” the caption gushed. “Dave Kingman moves glove around in addition to his bat.” The snapshot of Dave at third shows a ball getting by him. Not mentioned in any of the agate type: detailed fielding statistics.

After 1975, Dave Kingman would hit 118 more home runs for the New York Mets…and never play third base for the New York Mets again.

A multiplayer pileup is about to transpire at that ever blazing hot corner, encompassing Met outfielders, Met third basemen and, yes, Met catchers. The next article in our series, endeavoring to sort out who played what and who didn’t want to play where, is coming soon.

THE METS OF-3B/3B-OF CLUB

That ’70s Show Gets Underway (1970-1975)

15. Tim Foli

Mets 3B Debut: September 12, 1970

Mets CF Debut: September 7, 1971

16. Teddy Martinez

Mets 3B Debut: July 6, 1971

Mets LF Debut: September 12, 1971

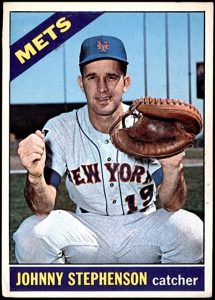

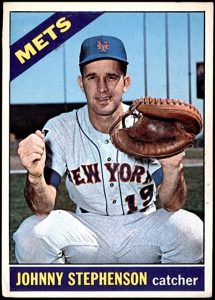

17. Jerry Grote

Mets 3B Debut: August 3, 1966

Mets RF Debut: July 12, 1972

18. Jim Fregosi

Mets 3B Debut: April 15, 1972

Mets LF Debut: June 5, 1973

19. Ken Boswell

Mets 3B Debut: September 18, 1967

Mets RF Debut: August 19, 1974

20. Dave Kingman

Mets RF Debut: April 8, 1975

Mets 3B Debut: September 15, 1975

Mets who’ve played both at third base and in the outfield represent one of my favorite things. As the new season approaches, Jeff Hysen and I swap a few others we love about baseball at National League Town. Listen here or on your podcast platform of choice.

by Greg Prince on 28 March 2022 10:21 am It got a little lost during Sunday night’s Academy Awards telecast, coming as it did after celebrity Mets fan Chris Rock was so rudely interrupted, but the Oscars aired their annual tribute (such as it was) to those no longer with us, which means, come the Monday morning after, we do the same. Except in our case, we mean it in the baseball transactional sense.

Here, then, for the sixteenth consecutive Spring, is our heartfully produced, hopefully inclusive montage saluting the Mets who have left us — the organization, not this earth — in the past year. At press time, we still don’t know where each of these now former Mets will wind up, but we do know that not long ago, whether for an evening or an era, they definitely Metsed among us.

We will remember you, albeit some more than others.

___

LUIS E. ROJAS

Manager

July 24, 2020 – October 3, 2021

I’d suggest Luis Rojas do whatever a manager can do with a compromised coaching staff and drill into his lads a few things about how to compete in every baseball game they play and how to win a bunch more than they have. At the very least, Luis, maybe let Lugo get up to set down more batters when he’s proving himself unhittable.

—August 26, 2020

(Relieved of duties, 10/4/2021; named Yankees third base coach, 11/15/2021)

___

AKEEM MAURICE BOSTICK

Relief Pitcher

July 29, 2021

For the silver lining-lovers out there, Miguel Castro continued on his journey back to sharpness with a scoreless sixth; Aaron Loup threw an ale of an eighth; and, making his major league debut, righty Akeem Bostick kept the Braves from inflicting superfluous ninth-inning damage. My scouting report on Akeem Bostick consisted of me learning after I got home from Wednesday night’s game that Akeem Bostick had been situated in the bullpen during Wednesday night’s game, having replaced Jerad Eickhoff on the active roster. Previous Mets to have replaced Jerad Eickhoff on the active roster in 2021 were Thomas Szapucki and Robert Stock. Have you seen Szapucki or Stock lately? Hopefully Bostick won’t be disappeared to wherever it is pitchers who dare to occupy the flip side of Eickhoff’s DFAs. wind up. He was obviously a happy young man when he tweeted, postgame, “I can FINALLY say ‘I’M A BIG LEAGUER!’” Akeem should indeed shout his newly earned status to the heavens. It’s a very special designation to have earned, even among Mets, a team that has habitually enlisted Jerad Eickhoff to start baseball games.

—July 29, 2021

(Free agent, 11/7/2021; signed with Kansas City Monarchs (American Association), 1/24/2022)

___

TREVOR SEAN HILDENBERGER

Relief Pitcher

April 17, 2021 – April 21, 2021

[N]ew export Trevor Hildenberger looked pretty good when he arrived and now he’s departed, because middle relievers.

—April 23, 2021

(Selected off waivers by Giants, 5/18/2021)

___

DANIEL JAMES ZAMORA

Relief Pitcher

August 17, 2018 – September 29, 2019

We knew Daniel Zamora, called up from Binghamton to replace DL’d Bobby Wahl, was our 54th Met of 2018. As with the 24 runs, this was big-time record-setting, or at least record-tying. The answer to the question some of us have been asking ourselves since 1967 — “Met 54, where are you?” — was finally answered. Knowing this milestone had been touched made us authorities on Daniel Zamora compared to not only Phillies fans but Mets fans in our section, which is understandable. There must have been a flock of Temple Owls in the house because Zamora was greeted primarily with “who? who?” It’s a common refrain at Mets games everywhere these days.

—August 18, 2018

(Selected off waivers by Mariners, 5/22/2021)

___

WILFREDO JOSE TOVAR

Infielder

September 22, 2013 – September 28, 2014

May 21, 2021 – May 29, 2021

Games remain scheduled whether or not you come prepared with an optimal assortment of players. It’s not the fault of the journeymen who are populating the roster currently that they were nobody’s first or second choice to be “the Mets” of the moment. They arrived in the organization as depth. They hoped they’d avoid alternate sites and get a call individually, but they didn’t expect to ascend to the majors en masse. I doubt they rallied one another in St. Lucie or Syracuse or wherever they crossed paths and said, “Wouldn’t it be great if all of us among the overlooked, undernoticed and generally dismissed got our chance together?” But they have. Sometimes, as on Friday, it works. Sometimes, as on Saturday, it almost works. Sometimes it’s Sunday, when Johneshwy Fargas doubles, Wilfredo Tovar singles him in and Yennsy Diaz looks good for an inning…and that’s it, basically.

—May 23, 2021

(Free agent, 10/4/2021; currently unsigned)

___

FRANKLYN KILOME

Relief Pitcher

August 1, 2020 – September 18, 2020

Franklyn Kilome got twelve batters out in his one outing, yet was optioned to Elba, but that transaction was primarily a function of churn. Go four innings as a reliever one night and you can’t be used for a couple of days, so go ice your arm by the beach, kid. Kilome might be back by Wednesday in time to take what had been Wacha’s turn, which comes after that of Rick Porcello.

—August 9, 2020

(Free agent, 11/7/2021; currently unsigned)

___

JAKE WILLIAM HAGER

Utilityman

May 15, 2021 – May 21, 2021

It was the first major league at-bat of Hager’s ten-year professional career and the first time any Met player wore 86, a pair of digits — like the city of St. Petersburg itself — that contains some Amazin’ championship cachet. New No. 86 Jake Hager finally getting this kind of chance was a reason to stay tuned, a reason to remain engaged, a reason to feel good. Hager proceeded to fly out, thus ending the positive evocation portion of our program.

—May 15, 2021

(Selected off waivers by Brewers, 5/25/2021)

___

JACOB ANDREW BARNES

Relief Pitcher

April 7, 2021 – June 13, 2021

[…] Jacob Barnes relieved Peterson and gave up a three-run homer on his first pitch delivered as a Met, a badge of insta-futility not donned since John Candelaria’s debut as a Plan H or I starter in the cursed ’87 season. Barnes also settled down, though by now the barn was in flames and the horses weren’t even bothering to flee but insouciantly hanging around to light cigarettes from the embers.

—April 7, 2021

(Traded to Blue Jays, 6/19/2021)

___

MASON JORDAN WILLIAMS

Outfielder

May 31, 2021 – June 19, 2021

Defensive replacement Mason Williams defended against a last-gasp Cub rally with a diving grab that made his insertion an instance of brilliant managing by Luis Rojas. The win, our third consecutive, pushed the Mets to ten above .500 for the first time since the end of 2019 and kept us five ahead of the NL East pack. Very nice. And excruciatingly irrelevant versus the only thing anybody is really talking about the day after.

—June 17, 2021

(Free agent, 11/7/2021; currently unsigned)

___

WILLIAM LANDIS “Billy” McKINNEY

Outfielder

May 27, 2021 – July 11, 2021

When Billy McKinney distributes his base hits as if from a variety pack — at least one among doubles, triples and homers before bothering with singles — Billy McKinney is my right fielder.

—June 7, 2021

(Traded to Dodgers, 7/21/2021)

___

STEPHEN NICHOLAS TARPLEY

Relief Pitcher

April 24, 2021

Perhaps Tarpley should have remained on another plane of existence — he threw 14 pitches and got nobody out, and now sits in the Met record books with an ERA of infinity. Spooky!

—April 25, 2021

(Released, 7/16/2021; currently unsigned

UPDATE: Signed with Long Island Ducks (Atlantic League), 4/22/2022)

___

RICHARD HEATH HEMBREE

Relief Pitcher

August 24, 2021 – October 2, 2021

Except there’s another game Wednesday night, and if the Mets win that (it’s possible), they’ll cut a half-game off the idle Braves’ lead. And if they somehow win Thursday night (it’s not over before it’s started), that’s another half-game, with Atlanta mysteriously on hiatus two days in a row. Now we’re 5½ out and the Braves’ schedule toughens, while ours lightens up, and Francisco didn’t look bad at the plate by any means, and Pete is hitting pretty consistently, and Brandon keeps getting on base, and Jeff was pretty good in the outfield in 2019, and nobody can blame the Heath Hembree-enhanced bullpen very much, and the more Carrasco pitches the more he’s bound to find his form, and isn’t Syndergaard about to begin a rehab assignment? It will be all over mathematically eventually and over beyond semantics soon enough. Until then, you never know and can’t help yourself from hoping accordingly. Even if you pretty much know it’s hopeless.

—August 25, 2021

(Free agent, 11/3/2021; signed with Pirates, 3/15/2022)

___

DELLIN BETANCES

Relief Pitcher

July 25, 2020 – April 7, 2021

Entering the bottom of the eighth, the Mets were leading, 10-6. No pitchers needed to be pinch-hit for because the National League no longer exists in such a natural state, yet the Mets were on their fourth pitcher of the night, Dellin Betances. In brief, it didn’t go well, and it went on extra long because two replay reviews ensued, neither of them amounting to a reversal of declining Met fortunes and both of them combining to eventually push the game into to its eighth half-hour. Betances left with the Mets’ edge reduced to 10-8 and Braves occupying first and third.

—August 1, 2020

(Free agent, 11/3/2021; currently unsigned

UPDATE: Signed with Dodgers, 4/5/2022)

___

CHANCE THOMAS LEO SISCO

Catcher

August 18, 2021 – September 3, 2021

And, for fun, McNeil doubled and Chance Sisco, a Triple-A name that hadn’t crept into our consciousness until the contingency backup catcher’s emergency backup was activated from the taxi squad, doubled on the first pitch he saw as a Met to make it 6-2. Ready to take a Chance again, indeed!

—August 19, 2021

(Free agent, 10/5/2021; signed with Mariners, 3/16/2022)

___

RAYMOND THOMAS “Tommy” HUNTER

Relief Pitcher

May 7, 2021 – May 18, 2021

Meet this Met

Meet that Met

Every day we meet more Mets

There’s Tommy Hunter

And his first hit

There’s Khalil Lee

Who can field quite a bit

—May 19, 2021

(Traded to Rays, 7/23/2021)

___

BRADLEY RICHARD “Brad” HAND

Relief Pitcher

September 4, 2021 – October 2, 2021

Hell, maybe the front office and its flawed parade of GM types knew what they were doing long enough to bring in the Villars, Pillars and Loups who have levitated the season just enough above sea level so that it hasn’t altogether drowned. Somebody in authority just signed off on bringing in Brad Hand. From a thumb to a Hand and nobody making a fist in a week’s time. That’s progress.

—September 3, 2021

(Free agent, 11/3/2021; signed with Phillies, 3/14/2022)

___

JERAD JOSEPH EICKHOFF

Starting Pitcher

June 21, 2021 – July 27 , 2021

Jerad gets us nervous, but mostly because we just met him, we’re not confident we can spell him and we know he wouldn’t be here if we had somebody more obviously qualified to do what he does. He calmed us down eventually, but we definitely had the feeling he and we got lucky. He’s welcome to come back soon. It’s not like we won’t have room for him.

—June 22, 2021

(Free agent, 10/6/2021; signed with Pirates, 11/29/2021)

___

FRANK ANTHONY BANDA

Relief Pitcher

July 19, 2021 – July 30, 2021

The Mets cashed in their ghost runner, but with Trevor May and Jeurys Familia and Aaron Loup all gassed, they handed the ball to the briefly aforementioned Banda. To call Banda unassuming would be putting it mildly — he looks like a fan who won a Closer for a Day! contest.

—July 20, 2021

(Selected off waivers by Pirates, 8/2/2021)

___

ROBERT ANTHONY STOCK

Starting Pitcher

July 7, 2021 – July 20, 2021

The Mets’ track record of winning first games and not winning second games hung heavy in the air, just like the air hung heavy in the air. Succeeding deGrom as starting pitcher was Robert Stock, the 1,141st Met ever and the first to wear 89. “Just give me whatever the temperature is at first pitch,” Stock presumably requested of clubhouse manager Kevin Kierst.

—July 8, 2021

(Free agent, 10/29/2021; signed with Doosan Bears (KBO League), 1/4/2022)

___

NICHOLAS PAUL “Nick” TROPEANO

Relief Pitcher

July 9, 2021

Stock started because, what, ya got somebody else handy? Shallow rotation depth is the soft underbelly of the first-place Mets (and I say that as one who knows from having a soft underbelly). It was either the guy the Cubs decided didn’t fit their needs anymore, or Nick Tropeano — a.k.a. Nicky the Trope; a.k.a. The 27th Man; a.k.a Guy Who Gets to Dress but Never Gets to Pitch.

—July 8, 2021

(Free agent, 8/4/2021; signed with Dodgers, 8/6/2021)

___

GEOFFREY THOMAS “Geoff” HARTLIEB

Relief Pitcher

July 20, 2021 – August 15, 2021

Geoff Hartlieb being activated as the extra player for a shortened game whose start was delayed by rain when it wasn’t raining before getting rained out and then being optioned before the next day’s pair of shortened games began may go down as the quintessential 2021 Mets transaction.

—August 13, 2021

(Selected off waivers by Red Sox, 9/4/2021)

___

CAMERON KEITH MAYBIN

Outfielder

May 19, 2021 – May 29, 2021

Poor Cameron Maybin set a new club mark for futility to begin a Mets career, going 0 for 27 and so topping (or perhaps the term is limbo’ing under) Charley Smith’s 0-for-26 start in 1964, but then tapped a little swinging bunt up the third-base line to get on base, an accomplishment greeted with rapturous applause from the stands and a flurry of jazz hands from his dugout. Maybin’s smile was a highlight in its own right, starting off low-watt sheepish and then brightening to big and genuine.

—May 30, 2021

(Free agent, 10/4/2021; retired, 1/3/2022)

___

COREY EDWARD OSWALT

Pitcher

April 25, 2018 – July 4, 2021

The Mets last week lost a game started by Steven Matz, 25-4. Five days later, because Matz was injured, they started Corey Oswalt in his place. […] Oswalt pitched much better than Matz did last Tuesday. Oswalt also pitches much better than Jason Vargas any day of the week. Yet Oswalt is considered to start only when somebody is injured. Despite Oswalt pitching well, the Mets lost, 5-4. That looks much better than 25-4, but it is still a loss. I wouldn’t discourage Oswalt from continuing to pitch well, nor the Mets from keeping their margins of defeat reasonable, but the real key to success for the team is not losing. This is a fundamental of baseball of which the Mets are likely aware, but given how infrequently they win, posting an occasional reminder seems necessary.

—August 6, 2018

(Free agent, 10/19/2021; signed with Giants, 1/12/2022)

___

REINALDO ALBERT ALMORA, Jr.

Outfielder

April 6, 2021 – September 14, 2021

J.D. was not alone in doing great things that involved the Citi Field fence. […] Albert Almora, Jr. took off toward it like Endy Chavez and slammed his body à la Mike Baxter into it, robbing Kyle Schwarber with a flair that was all Almora. Albert with the championship pedigree walked away in one piece unlike Mike from Bayside and will dress for a game again very soon, which unfortunately Endy didn’t following the Endy Catch. Chavez’s team had reached its end when he made his grab in 2006. Almora’s team is just getting going.

—April 26, 2021

(Free agent, 10/6/2021; signed with Reds, 3/20/2022)

___

JOSE FRANCISCO PERAZA

Infielder

May 2, 2021 – October 3, 2021

Jose Peraza leaves a team in Cincinnati, detours through Boston, and then without warning arrives in New York. How long does it take Jose Peraza’s second home run of the year to depart Citi Field?

—May 27, 2021

(Free agent, 10/29/2021; signed with Yankees, 11/29/2021)

___

RICHARD JOSEPH “Rich” HILL

Starting Pitcher

July 25, 2021 – September 30, 2021

Hill bunted and sacrificed McCann to second, just as NL hurlers have been asked to do for all but one of the past 145 years, or since Rich Hill was a lad. He had done his pitcherly duty, and I leapt to my feet to applaud. Then, armed with a 6-3 lead, he went out to work the fifth, throw his “69 MPH UNKNOWN” (by the scoreboard’s reckoning) and qualify for the decision. He preserved that lead — his lead — and left as the pitcher of record on the winning side. I stood and applauded again. Like autumn’s chill, a generosity of spirit pervaded the air.

—October 1, 2021

(Free agent, 11/3/2021; signed with Red Sox, 12/1/2021)

___

BRANDON SHANE DRURY

Utilityman

May 21, 2021 – August 31, 2021

[…] Luis Cessa gave up a walkoff single to Brandon Drury, and the everybody’s-the-hero Mets defeated the Reds, 5-4. Mets fans, I can report with accuracy, went nuts with appreciation. It didn’t appear we were “supposed” to win, but what was Brandon Drury supposed to do other than record yet another humongous hit? After all, Drury’s OPS in July was infinity. I could look up the real number, but I’m a Mets fan. I know pretty incredible statistics off the top of my head.

—August 1, 2021

(Free agent, 10/14/2021; signed with Reds, 3/21/2022)

___

EDNEL JAVIER “Javy” BAEZ

Second Baseman

July 31, 2021 – October 1, 2021

We might not remember how Baez helped the Mets in his first ten games in our colors because when he wasn’t sparking us toward a couple of victories, he was weighing us down badly (.171/.216/.343) as we commenced losing chronically. It thus dawned on me Sunday that Javy Baez is something akin to our Howard Cosell. He’s the best player we have on the field when he’s not playing worse than everybody else. He’s Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s little girl with the curl to whom Ralph Kiner was so fond of referring. “When she was good, she was very good,” Ralph liked to say. When she wasn’t, she struck out a lot and threw wide of first.

—August 22, 2021

(Free agent, 11/3/2021; signed with Tigers, 11/30/2021)

___

KEVIN ANDREW PILLAR

Outfielder

April 4, 2021 – October 2, 2021

It’s a hit by pitch and a run batted in, yet the scorekeeping is irrelevant. It’s a person down in the dirt bleeding badly, requiring medical attention and in no condition to rise and do something as presumably effortless as jog to first base. Watching on television, also in about a second, your priorities switch from let’s get at least another run here, it’s only 1-0, we need all the help we can get, c’mon Pillar to yikes! or interjections to that effect. You just want the blood to stop and the person on the ground to get up and, if you can find it in your heart to worry about the mental well-being of the pitcher whose fastball got away, the person on the mound to grab a seat and get ahold of himself, whatever form that takes.

—May 18, 2021

(Free agent, 11/5/2021; signed with Dodgers, 3/22/2022)

___

JONATHAN RAPHAEL VILLAR

Infielder

April 5, 2021 – October 3, 2021

I was never more home than with the Mets game coming out of my shirt pocket on the boardwalk in Long Beach in 2021. This was me in the summers off from high school and junior high and elementary school. Wayne Randazzo narrating a Jonathan Villar homer meshed with the soft crash of the waves. It sounded like my life. That baseball radio play-by-play was emanating from my person didn’t merit commentary from my wife, who is very used to the sounds my body makes, nor from my old pal Fred, who knows what I’m all about. The first thing I can ever recall Fred and I doing outside of school involved a walk and a Mets game on my transistor radio. I told him I don’t like to miss the Mets when they’re playing, and I never had to tell him again.

—July 15, 2021

(Free agent, 11/3/2021; signed with Cubs, 3/17/2022)

___

AARON CHRISTOPHER LOUP

Relief Pitcher

April 5, 2021 – September 29, 2021

Aaron gave up two Pirate hits and hit ex-Met Phillip Evans to begin the bottom of the sixth. That’s what is referred to in certain circles as a sticky wicket. But you know that stuff you see commercials for to resolve stickiness? It’s called Loup. Spray it on the toughest jams and it strikes batters right out! I know, it sounds like a scam, but it works. Loup struck out Adam Frazier, struck out Wilmer Difo and struck out Bryan Reynolds, thus leaving the bases loaded. “Wow,” you might be wondering, “can I get a can of that Loup for my sticky wickets?” Sorry, they’re all sold out.

—July 19, 2021

(Free agent, 11/3/2021; signed with Angels, 11/22/2021)

___

MARCUS EARL STROMAN

Starting Pitcher

August 3, 2019 – September 28, 2021

In Sunday’s finale, Marcus Stroman took the mound. Marcus Stroman isn’t Jacob deGrom, and not because nobody is Jacob deGrom except Jacob deGrom. Nobody who isn’t Marcus Stroman is Marcus Stroman, either. We’re not talking about asking for ID. Stroman approaches his outings like nobody I’ve ever seen in more than fifty years of watching Mets baseball. He doesn’t “attack” the batter or the strike zone. He attacks the entire game. If a top rope surrounded the rubber, he’d climb atop it, jump off of it, pin the batter he’s startled and egg the crowd on to chant his name. That’s “his attitude,” Conforto said of his 3-0 teammate in Sunday’s postgame Zoom, “the ultimate confidence in himself, and I think that can be contagious sometimes.” Rooting for our first-place team, we should all come down with a case of that kind of self-belief.

—April 19, 2021

(Free agent, 11/3/2021; signed with Cubs, 12/1/2021)

___

ROBERT JOHN GSELLMAN

Pitcher

August 23, 2016 – October 3, 2021

If Gsellman isn’t overpowering, he is effective. And the effect is electric. Instead of woe-is-us’ing the days away, we move up in the standings. What was more unlikely — the Mets being one game out of playoff qualification or knowing who the Gs-hell Robert Gsellman is at all? Given the pallor left behind by the previous 48 hours, focused mostly on Jacob deGrom and his mysteriously barking forearm, how could you not embrace this shaggy incarnation of vintage [Marty] Bystrom?

—September 4, 2016

(Free agent, 11/30/2021; signed with Cubs, 3/17/2022)

___

JEURYS FAMILIA

Relief Pitcher

September 4, 2012 – July 14, 2018

March 28, 2019 – October 1, 2021

With no cushion provided, Familia returned to the mound for the ninth with the same 3-2 lead that had been effect since the sixth. His first assignment was retiring the loathsome Chase Utley, who shouldn’t have been wearing any uniform this week other than an orange jumpsuit. Utley gave a ball a ride to right, but then the ball said, no thanks, I’ll get out here, and fell into Granderson’s glove. Met karma intact, Jeurys reared back and struck out A.J. Ellis and then Kendrick. Oh, by the way, that was the 27th out. The Mets had won the game and the series, both by a score of 3-2. The next sight you saw was their entire roster forming a ball of human Silly Putty. The next sound you heard was — for the 18th time in franchise history — the spritzing of champagne over everybody and everything orange, blue and otherwise. The next thought you had was “tonight the Dodgers, Saturday the Cubs.”

—October 16, 2015

(Free agent, 11/3/2021; signed with Phillies, 3/12/2022)

___

NOAH SETH SYNDERGAARD

Starting Pitcher

May 12, 2015 – October 3, 2021

For that matter, you only noticed the eleven runs a little, because all your focus was on Noah Syndergaard. Over eight innings, he registered as many strikeouts as the Mets plated runners: eleven K’s to go with no walks and no runs. There were three Pirate singles scattered, one in the first, two in the sixth. By the sixth, when Syndergaard shrugged off the mild threat by fanning Andrew McCutchen looking for Strikeout No. 8, the Mets led, 7-0. There was no danger. There was only Thor, tossing what could be best described as a Thor-hitter. Come the bottom of the eighth, Syndergaard batted, an excellent sign of what he’d be doing in the ninth. Sure enough, in the ninth, we got what we stayed for. We got Thor on the mound for another inning. All he needed was three outs to add to his previous 24. If he could proceed in mussless, fussless fashion, we’d be telling each other on the way out that we had just seen Noah Syndergaard’s first complete game and Noah Syndergaard’s first shutout. We already talk of Thor so much we need new material. We wanted it like he wanted it. We would have accepted simple groundouts or pop flies, though if it were put to a text poll, we would have entered “K” for another round of emphatic door-slamming, Pirate-pounding strikeouts. We wanted him to go out in blazes of glory and flourishes of phenomenal. We wanted Rivera cradling that last 97-MPH fastball, leaping to his feet and embracing his pitcher. We couldn’t wait to tweet that perfect-partnership image and hashtag it #Thorvera. That would have been something, but it will have to be something for another game.

—June 16, 2016

(Free agent, 11/3/2021; signed with Angels, 11/16/2021)

___

MICHAEL THOMAS CONFORTO

Outfielder

July 24, 2015 – October 3, 2021

After I got home and watched the replay, Michael Conforto’s one-on, two-out, ninth-inning drive to left-center proved ordinary. It was a deep fly ball but quite catchable, and sure enough Andrew McCutchen caught it to send Friday’s Mets-Pirates game to the tenth inning, knotted at one. From Row 21 of Section 109, however, it looked perfect. Too perfect, in retrospect. Who wouldn’t want the Mets’ top draft pick of 2014 to deliver a signature blow and add another chapter to 2015’s improbable first-place story? And if you happened to be monitoring the flight of the ball alongside somebody who was wearing a recently purchased CONFORTO 30 t-shirt…somebody who had a few hours earlier posed for a picture with his shirt’s namesake…c’mon, who could ask for anything more? So we — that would be me and Citi Field goodwill ambassador Skid (who swears he never wears shirts with players’ names normally, but on impulse he bought the rookie’s) and Mike, who’s visiting Skid from California — asked for simply that. We asked for Michael Conforto, in his fifteenth major league game and his second pinch-hitting appearance, to provide the proverbial storybook ending. The ball he hit appeared standsbound off the bat. We wished it and we hoped it toward the Party City Deck. We wanted it to be a gala ball. But it wasn’t. It was an out. The rule about not always getting what you want held, just like the 1-1 score, at least until the tenth. […] What is easy to see is that unlike the other new, likely rented faces you had to gawk at twice to recognize fully during BP because they haven’t been Mets very long (and they, too, wore unnumbered warmups), Michael is slated to be a Met for years to come. Conforto will drive other balls to deep left center. A few are bound to keep traveling.

—August 15, 2015

(Free agent, 11/3/2021; currently unsigned)

by Greg Prince on 21 March 2022 9:02 pm Armwise, I’m a righty who hails from a family of natural-born lefties. Sis is sinister by nature. So was Mom. Dad trended to the left side as a youngster, but this horrified his grandmother and he was converted to righthandedness before he was old enough to effectively protest. He lived 87½ years with the illegible penmanship to prove he was a righty trapped in a lefty’s body.

But I’m a righty all the way, save for philosophically. From Seaver to Gooden to deGrom, I’ve always instinctively identified most closely with Mets righties of the starting pitcher genus, yet I have no bias when it comes to the big picture. I recognize a pitching staff is not complete without solid lefty penmanship. Today, even in the wake of righty Mets starter Max Scherzer’s Grapefruit League debut — a juicy 72 pitches thrown over five innings, yielding only a single earned run that doesn’t count — we find reason to salute a few southpaws who gave the Mets as much relief as they could, even if they couldn’t all be Tug McGraw.

You know who could be Tug McGraw? Tug McGraw! (Trick question.) You know why Tug McGraw could be unhittable? Because he had a screwball that confounded the art of hitting. You know who taught him how to throw it?

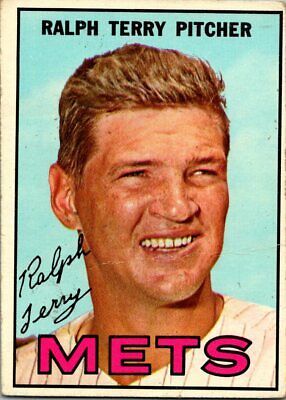

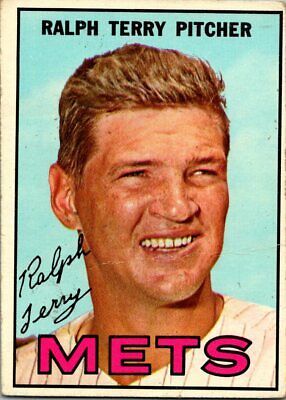

A righthander named Ralph Terry. See, left and right can work together. So can a pitcher known mostly for having been a Yankee and pitcher who came to prominence as a Met. Neither Tug nor Ralph were enjoying a particularly prominent phase of their lifetimes when their paths crossed as Mets in 1966. Tug’s first big moment, defeating Sandy Koufax after no Met had, was more than a year old. He wasn’t quick to craft a string of encores. Ralph’s big league peak was similarly past-tense, except much longer ago. In 1962, Terry went 23-12 for a world championship ballclub and he was the MVP of their seven-game World Series triumph. It marked a dramatic turnaround from two years earlier when “Game Seven” and “Ralph Terry” added up to “the Bill Mazeroski home run” that needs little elaboration.

By 1966, Terry was hanging on, which was a good description for most Mets who couldn’t be referred to as coming up. The Mets had a lot of hangers-on amidst their up-and-comers. Eleven appearances in ’66 produced a save and a loss for Terry. Two more in ’67 amounted to his big league exit. But in between, during the Florida Instructional League interlude of 1966, Terry and Tug got together. Ralph was around to discern how many competitive pitches might remain in his right arm if only it could figure out how to master a knuckleball — that and golf. Tug simply needed to hone his skills in a circuit designed for “brand new rookies and slightly used rookies like me who are having problems” — that and golf.

Pitchers of all ages and both dominant sides love to golf.

Say, the veteran mentioned to the youngster between juggling knucklers and Titleists, maybe you’d have some luck with the screwball. According to Tug in the helpfully titled memoir named for his signature pitch, Ralph “suggested that I turn the ball over when I pitched it, taking something off my fastball and turning my wrist in toward my body when I released the pitch. He showed me how it would spin, using a golf ball as a prop, and right there my screwball was born — on a golf course in Florida.”

Terry the teacher knew exactly how to screw up his student. It would take a while for Tug to master his new pitch (and for Met coaches to buy in), but once he got a good grip on it, McGraw and the screwball became synonymous. Consequently, the Mets bullpen blossomed once Gil Hodges planted Tug as the lefty late-innings complement to righty Ron Taylor in 1969, a year the Mets closed in the highest style possible. The Mets went to a second World Series four years later only after McGraw rediscovered his scroogie down the stretch (it had somehow scurried out the doggie door at the height of summer). And we can thank a pretty fair righthanded pitcher and golfer named Ralph Terry, who died on March 16 at age 86, for getting Tug and the rest of us to believe as we did. Deney Terrio billed himself as the man who taught John Travolta how to dance and got the syndicated show Dance Fever out of it. Ralph Terry was just helping out a young teammate as he himself was moving on.

We should also thank Tug’s singing son Tim McGraw for taking to Twitter and sharing the following anecdote on St. Patrick’s Day, because receiving an extra opportunity to think about Tug McGraw in the same week is like finding a four-leaf clover in each pocket of your warmup jacket:

His favorite holiday, really, was St. Patrick’s Day. He was very proud of “McGraw” and bein’ Irish. […] My uncle did a little research into our family and told Tug one day, “I don’t think we have quite as much Irish blood as you think.” It sort of pissed Tug off, and he just said, “[Bleep] you, I’m stayin’ Irish. It’s been good to me!”

However much Tug might have enjoyed March 17, 1968, by Opening Day, despite having pitched for the Mets at least some of each of the preceding three seasons, the 23-year-old would be down in the minors for the duration. “No argument from McGraw,” Tug third-personed in Screwball. “It was a good move, because in all honesty I hadn’t had enough time in the minors yet.” While Tug worked on turning the ball over in Triple-A Jacksonville (where during a previous stint he’d met the woman who gave birth to Tim; he did have some time in the minors), the Mets needed to fill whatever void he left in New York with another lefty. They did so, in part, with the veteran reliever Bill Short.

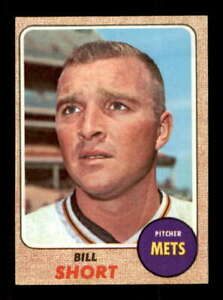

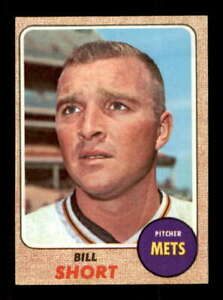

Apropos of his surname, Bill wasn’t a Met for long, although by recent Met reliever revolving-door standards, Short lasted a veritable lifetime: the entirety of the 1968 campaign. Historically, he occupies a couple of odd places for a franchise that’s always been a little bit out in left field. For one thing, Bill Short, who’d been in professional baseball since 1955, is the only player in Mets history you can’t call anything but a 1968 Met. I might not have bothered to look it up had it not been for what being a 1969 Met means.

I’ve always felt a little bad for Short and the eight other 1968 Mets who didn’t last with the club that one extra year. The rest arrived in Flushing somewhere between 1965 and 1967. Three — Jerry Buchek, Phil Linz and Billy Connors — reached the end of the line in ’68. Five — Dick Selma, Larry Stahl, Greg Goossen, Don Bosch and Don Shaw — found work with freshly minted expansion teams facing the endless miles of bad road the maturing Mets were about to be done with (though Selma would have his standing elevated by April when the front-running Cubs traded young Joe Niekro to San Diego to secure the former Met phenom’s services). It’s not like the 1969 Mets didn’t become the 1969 Mets without the nine 1968 Mets they cast off, and it’s impossible to determine whether the 1969 Mets would have gone as far as they did with them.

Still, talk about bad timing.

Bill Short (sometimes referred to as Billy, as players named Bill might be) resided somewhere in the middle of a cohort neither Bulova nor Armitron would have been anxious to sponsor. The Mets picked him up from the Pirates after Bill spent most of 1967 bringing his left arm back to life in the minors. Injuries had plagued him earlier in a career that never quite took off. His major league experience consisted of 35 appearances spread over four seasons that themselves spanned eight years. Yet here he was, of interest to the 1968 Mets for the reason many pitchers who don’t throw with their right arm are of interest to teams in any era.

“I want to see him in the bullpen,” Hodges said early in Spring Training. “I understand he can get lefthanded batters out.”

The siren song of the lefty reliever was enough to allow the 30-year-old southpaw to rise above stiff competition in a camp populated by young, live arms. Seaver was the known quantity. Nolan Ryan always drew attention. Jerry Koosman pitched his way into the rotation, shaking off his shaky ’67 auditions (Kooz, incidentally, was relieved in his first career appearance by Ralph Terry). But in the shadow of all that obvious talent, Short delivered 10 scoreless Florida innings, made the Mets and endured from April to September, accomplishing a niche that accounts for his second odd niche in Mets history.

Charter member of the No Homers Club. In sixty seasons of Mets baseball, per Baseball-Reference magnificent Stathead tool, only thirteen pitchers have faced at least 100 batters in a given year and surrendered zero home runs. Zilch. Zippo. The first of these gopherless ballers? Why, Bill Short. One-hundred twenty-eight hitters came to the plate against Billy. None took him deep. Not only was it a franchise first, it would stay a franchise rarity. No Met would be as nimble at not allowing homers again until Paul Siebert in 1977. The roster of other slugger-unfriendly hurlers includes high-profile starters Ron Darling (as a rookie in September 1983), Pedro Martinez and Noah Syndergaard (both in years — 2007 and 2017, respectively — when their appearances were curtailed by injury) and a handful of shooting not-quite-stars (Jaime Cerda, Orber Moreno and Juan Padilla among the early 21st-century contingent). The best Met pitcher at not giving up a single home run, which is to say the Met who faced the most batters in a season without having to stand on the mound and watch his opponent circle the bases?

That it was a Met pitching in 1986 probably wouldn’t surprise you. That it was Doug Sisk might make you rethink the “boo” you just mentally formed at seeing the name Doug Sisk. Say what you will about Sisk, but be sure to add “Doug faced 312 batters, gave up no home runs and the Mets won the World Series.” Context and nuance is your call.

But Bill Short got there first. Interestingly, despite Gil Hodges finding him attractive on the basis of being a lefty reliever who could trouble lefty hitters, Short’s splits in 34 games coming out of the pen indicate a southpaw who came north to get out batters on each side of the plate. Lefties slashed .222/.308/.311 against Bill. Righties posted a line of .219/.307/.266.

Bill, whose February 2 passing at 84 surfaced within the baseball community only in the last few days, proved himself a representative major leaguer in 1968, and maybe he could have contributed to the team that was about to become the 1969 Mets. Alas, the Mets left him unprotected in December’s Rule 5 draft and the Reds snatched him up. Detailed splits of the type cited above were not readily accessible more than a half-century ago. Otherwise, one gets the feeling his new manager, Dave Bristol, wouldn’t have reflexively echoed Hodges from a year earlier. “Short can get out a lefthanded batter,” was Bristol’s limited assessment…because isn’t that what lefthanded relievers do?

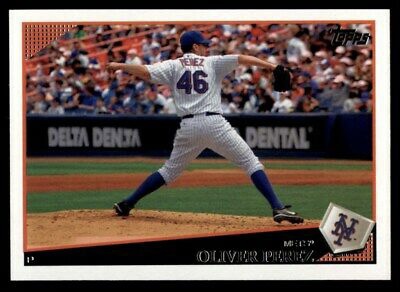

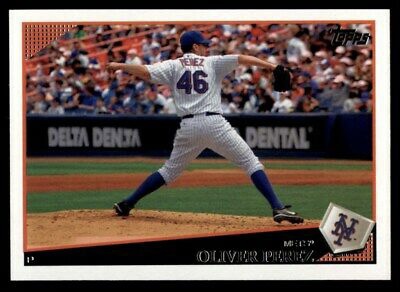

Oh, you know who you can ask? The lefthanded reliever whose arm, we can cheerfully report, may very well be deathless. Oliver Perez is back in a big league camp, seeking to resume his MLB tenure as an Arizona Diamondback. Of course he is. We’d last seen Ollie in a Cleveland uniform in April, and then we read over the extended winter that Ollie was going to give it one more go in the Mexican League and then definitively hang it up this year. But why hang it up when you can hang around and get out a lefthanded batter? Ollie’s 40th birthday has come and gone. No reason he needs to.

It’s hard to not embrace an active player who called Shea home. Why, you may wonder, would we so embrace the idea of a little more professional success for Oliver Perez, considering that when he finished wearing a Mets uniform in 2010 we were collectively founding Uber for the express purpose of giving him a ride to the airport? Because if Ollie — who revived his fortunes by reinventing himself as a lefty specialist when we were still fuming that he wouldn’t consent to set himself right in Buffalo — makes the D’Backs, he automatically doubles the number of big leaguers in 2022 who can say they played as Mets at Shea. And as long Shea Stadium personnel continue to ply their craft on a major league playing field, then Shea lives. There’s Joe Smith, a lad with us in 2007 and 2008, who just signed with the Twins, and there’s Ollie. Ollie of the 2006-2010 Mets preceded Smith on the Mets, ergo Perez is potentially poised to reclaim his LAMSA mantle, which is to say the Longest Ago Met Still Active. We thought Ollie was all done in the majors. Silly us. Giving up is for kids.

Good luck, Oliver (unless you face us, of course). Good luck, Joe, a righty, but vintage Shea is vintage Shea, regardless of theme. And, while we’re dispensing good fortune, good luck to another veteran reliever, Mike Montgomery, signed by the Mets in February of 2021, only to be released in March of 2021. Mike has been granted his second Metropolitan shot via a minor league deal because guess what arm he throws with.

Hope, like lefties, spring eternal.