The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 14 April 2022 12:42 pm “You gotta believe,” you may have heard once or twice in your life over these past 49 years. And you really do, especially in April. If you’re giving up this soon, it’s a long May through September in front of you. Yet here in the early won-lost portion of the season, when records are instantly recognizable to me in terms of Mets clubs who’ve had them before, I can remember not necessarily wrapping my doubts in a reassuring cloak of belief because, well, as much as you gotta believe, you also gotta believe what you’re trying to believe.

For instance, when the Mets won their first three games of this season, I remembered they won their first three games of the season ten years ago. I didn’t really believe in the 2012 New York Mets three games in. I believed I liked they were 3-0 and I hoped it was indicative of success over the next 159 games, but I didn’t expect much. Some years are like that. Some years, if you’re lucky, your expectations are dashed for the better. For a while, the 2012 Mets were outrunning what was expected of them. I barely budged from my certainty that it was all illusory and temporary. As they approached the All-Star break in still pretty good shape, I allowed to myself that maybe there was something there.

There wasn’t. The 2012 Mets, quick break from the gate notwithstanding, dropped off the face of the playoff race before July turned to August and finished 74-88. I never really got my hopes up, thus I didn’t feel much of a thud when the team crashed to where they were originally expected to land.

Other than the 3-0 and now 5-2 starts, I don’t know what else the 2022 Mets have in common with the 2012 Mets or any other Mets club that came before. We’ve only seen seven games from this edition. One road trip down, everything else to go. But I do know I expect good things.

How good, I’m not certain. Good, certainly.

This 5-2 Mets team is feeding into my expectations and my belief. A bounty of baseball spreads out before us. How can you not want to look forward to more? So what if they can’t go 162-0? They can go 160-2! Should clear horizons turn to abyss, as the preliminarily promising seasons of 20, 30 and 40 years ago did — we had high or at least high-ish expectations entering 1982, 1992 and 2002, all of which were not so much dashed as detonated — then we can revisit the process of raising one’s hopes next April. For now, these Mets who were supposed to be a damn sight better than they were last year are clearly a damn sight better, and perhaps then some.

After their finale in Philadelphia, they’re 5-2. If that itself does not provide compelling proof (it’s only seven games) perhaps those who’ve engineered the club’s winning ways to date can give us reason to believe and expect, expect and believe.

On the seventh day, corresponding with the fifth win, there was Max Scherzer. You’ve heard of him. He’s a New York Met now, with two starts under his belt. The results have been quite Scherzerian in that the team he pitches for, which is now the New York Mets (seems worth repeating at every turn), won. Scherzer went only five, with a lot of pitches in the first, but he gave up only one run. The one run he seemed to take personally, like he swore to himself that he’ll never let it happen again. You’re gonna bet against Max’s interior monologue? Because if you are, I’m sure MLB has an app to enable you.

There was also Pete Alonso, another Met with whom I’ll wager you’re familiar. Alonso matched Scherzer’s innings with runs batted in: five, three of them on a back-breaking home run, at least before a few Mets relievers attempted reconstructive surgery on the Phillies’ spine. Alonso DH’d on Wednesday afternoon. I worry about Pete with all that extra time on his hands during defensive innings. I picture legitimate businessman Tony Soprano planting himself at Barone Sanitation on advice of counsel in order to keep himself out of trouble and not responding well to remaining in what amounts to captivity for eight hours a day. Will Pete create a basketball pool? (MLB would probably enable that, too.) Get a little too friendly with the office staff? Develop a rash? Or will he just keep his head in the game despite not having a glove on his hand? His bat spoke volumes to the affirmative.

There were and are the Black Friday Three: Starling Marte, Eduardo Escobar and Mark Canha, a collective I will someday de-link and treat as individuals, but for now, I lovingly lump them together since they all signed with the Mets amid the same post-Thanksgiving shopping spree and, in their new team’s first seven games, have proven a bargain. Canha’s on-base percentage is .500, Escobar’s a tick below that at .481. If they’re your benchmarks, please update your cliché to, “Remember, in baseball, even the best players fail approximately half the time.” Although he hasn’t reached base nearly as often, Marte seems to be doing everything else. He’s brought speed to the bases and an arm to right field, having legged out a critical run in the fourth after cutting down a potential opposition double in the second. Marte gives off the aura of knowing what he’s doing on the diamond and actually doing it. You don’t always get that combination.

The Mets still have Brandon Nimmo, who is tied with Alonso for the team lead in homers with two; they still have Francisco Lindor, whose hustle on a would-be ground ball double play kept alive the sixth so it could continue on to Pete’s three-run dinger. And they have Edwin Diaz as the firewall of a bullpen that wasn’t keen on not immolating a segment of a seven-run lead. Sugar managed to not blow the remaining four-run advantage when he entered in the ninth…which sounds like damnation with faint praise, but in shallow Citizens Bank Bandbox, every out is deeply appreciated.

The Mets also absorbed three additional bruises from being hit by pitches on Wednesday. Nobody had to be removed out of an abundance of caution and no mounds needed charging. Still, it’s not a positive development when your team has more HBPs (10) than games played. Also, the post-Scherzer, pre-handshakes portion of the pitching staff is still, generously speaking, a work in progress. Diaz did Diaz. Lugo was sharp. Reid-Foley, Rodriguez and Ottavino weren’t. Buck Showalter’s still calculating who is capable of doing what when. It’s not something he could truly know in advance and it wasn’t something that was able to be addressed en masse during this briefest of Spring Trainings. Prefab bullpens are hard to come by, what with all the supply chain issues. Since Clayton Kershaw wasn’t doing anything Wednesday afternoon once he’d thrown seven perfect innings, you’d figure Steve Cohen could’ve sent a plane to Minneapolis to hire him for the rest of the day. That may not jibe with any of the most recent spate of rules changes, however.

Met imperfections aside, we can now count a 9-6 win to end the road trip; a 5-2 record on the road; a Home Opener on deck; and expectations of a team that’s supposed to be good being so far met. You don’t gotta believe, but you might as well.

When the Mets come home on Friday, they’ll be starting their fourteenth season at Citi Field. Where the time has gone and how the suddenly no longer “new” ballpark has held up for thirteen years is the main topic on the latest episode of National League Town, which you can listen to here or wherever you take your podcasts.

by Jason Fry on 12 April 2022 11:44 pm The first week of baseball is nearly always the same: a season’s emotional journey in miniature form, with the only difference what order the necessary components get assembled in this time.

So, for the 2022 Mets it’s been:

- Convinced the stars have aligned and your team will go 162-0.

- The first galling loss of the season that leaves you fuming and then making excuses because hey, it was close.

- The first gut-punch loss of the season that leaves you wondering why you subject yourself to chronic pain.

So what would come Tuesday night against the Phillies? A range of possibilities presented themselves, from Illusory Return to Invulnerability to Suspicion That All Will Not Go Swimmingly to Fuck Me It’s Too Early to Get My Heart Stomped On Again. The Mets tried all of those on for size before settling on Well I Was Wrong the Whole Goddamn Time and You Know What That’s OK With Me.

An early 3-2 record is also a fraught moment, because what’s actually just one game in a very long parade is granted a thoroughly manufactured fork-in-the-road significance. If the result is a 4-2 record, you’ll talk yourself into believing that they’re rounding into form and the sky’s the limit; if the result is a 3-3 record, it’ll be clear that they’ll never get out of their own way and a summer of muddling awaits.

Adding to my emotional baggage was the fact that the man on the enemy mound was Zack Wheeler, the last mortal sin inflicted on the Mets by the dreadful Wilpons and their hired stooge Brodie Van Wagenen, a man who should be remembered more than he will be for his oily chiseling and crumminess. It was the Wilpons who let Wheeler walk instead of resigning him; it was Van Wagenen who obediently stuck the knife in Wheeler’s back after he accurately described the Mets’ conspicuous lack of interest in retaining his services. Wheeler followed up Van Wagenen’s sneer about parlaying two half-good seasons into $118 million by proving he was worth that contract and was exactly what the Mets sorely needed instead of turning to the likes of Jerad Eickhoff and Robert Stock as their playoff hopes drained away. It pissed me off then, it pisses me off now, it will piss me off a decade after Wheeler retires.

That said, Wheeler took the mound not at his best, having had an even more abbreviated spring training than everybody else. His velocity was down and his location was off; still, he had enough to match an energized Tylor Megill — whose simplified mechanics and winter off have made him look like a different pitcher — into the fifth. This unlikely tie in a bandbox ended when Brandon Nimmo hit a missile off his old teammate into the right-field seats, but then Megill departed after two trips through the Phillies’ order and it was time for the Mets to somehow find 11 outs.

They did so at first behind Chasen Shreve — who still looks like he’s been living under a bridge, in case you were worried — and Drew Smith, whose dewy cheeks still suggest puberty has yet to arrive. The arm is fully developed, though — Smith looked particularly impressive, using his entire arsenal in the seventh to retire Bryce Harper, Rhys Hoskins and Didi Gregorius while sidestepping a Nick Castellanos double.

The Mets took a 2-0 lead to the ninth, but Edwin Diaz was coming in with Kyle Schwarber, J.T. Realmuto and Harper coming up, and let’s just say my confidence was not elevated.

There’s a great moment in the (underrated) 2017 movie American Made in which Tom Cruise, playing a restless pilot mixed up with drugs and guns and other bad ideas, turns on his usual high-wattage charm to ask his wife if she trusts him.

“NO!” she responds instantly, offended that he’d even try it.

That’s me with Diaz, no matter what the stats might say. The enemy ninth had “walkoff with no outs recorded” flashing red in my mind, and part of me wanted to hide downstairs until the inevitable had come crashing down.

But Diaz’s slider was working, either because he’s made some adjustment (let’s say so, because why not) or because randomness was on our side tonight (let’s not think about this). He struck out Schwarber, gave up a bad-luck infield hit to Realmuto, struck out Harper, and then coaxed a ground ball from Castellanos, which Francisco Lindor snared in the hole and tossed over to Jeff McNeil at second. Except Realmuto is annoyingly fast for a catcher, and was safe. That meant Hoskins would bat with the tying run on first as the tying run, with Gregorius behind him, and why exactly hadn’t I hidden downstairs when I still could?

Throwing all sliders to Hoskins, Diaz worked the count to 1-2 and then buried a slider in the dirt — the classic call, but not enough to tempt Hoskins. What was next? The high fastball to change Hoskins’ eye level and speed up his bat? Sure, but Diaz had to throw it high enough so Hoskins couldn’t square it up, a plan he hasn’t always proved able to execute. So the slider, then? Sure, but Diaz needed to not throw one that flattened out and sat in the middle of the plate, destined to become a souvenir. String together enough of those moment-to-moment agonies and you have a baseball game, but this game was destined to come down to the outcome of that one particular agony.

Diaz opted for the slider and it was another perfect one, diving at the knee on the opposite side of the plate. Hoskins swung helplessly and missed and the Mets had won. Won, and taken the correct path after reaching that fork in the road, the one that leads to the sky being the limit.

You believe that, right?

by Greg Prince on 12 April 2022 12:21 am “Hit it to Alec Bohm” shaped us as the winning formula in Philadelphia Monday night. The Mets kept beleaguering the Phillies’ third baseman, grounding balls in his direction; compelling him to pick them up; and forcing him to do something with them. Errant throws ensued in such volume that he was henceforth to be known as beleaguered Phillies third baseman Alec Bohm. By the third inning, Bohm had three errors and the Mets had three runs. Although only one of the errors took place in an inning with runs, and although the runs were earned, the 3-0 Met advantage came across as a product of shoddy Phillie defense. “Don’t get defensive, Philadelphia,” was an early favorite of the hypothetical Banner Day judges.

Also by the third inning, Taijuan Walker had thrown two perfect innings. That, however, is where threes stopped being relevant. The Mets would have to move on to a second pitcher because Walker, whose knee gave him trouble in Spring Training, left with shoulder irritation. You’re familiar with the phrase “shoulder irritation”. It resides in that same instantly repeatable section of the baseball dictionary where a couple of weeks ago a million Mets fans simultaneous turned to define “scapula”. Now the secret words were shoulder irritation. Find cause to say it aloud and lose a starter for at least the rest of the night.

To our rescue came David Peterson, good-looking young pitcher from two years ago, less good-looking last year, reborn in the moment as a brilliant piggyback reliever. Peterson — who Ubered over from the taxi squad when Edwin Diaz went on bereavement leave — jumped on the back of Walker’s two zeroes and totaled four of his own. The Mets were up, 4-0, by the middle of the seventh, with James McCann having stolen everybody’s commodity, an insurance run. A catcher should get to do that now and then. After he ran the bases with tempered abandon and was rewarded for his efforts, James returned to his main job of catching pitching. The Mets were on their third pitcher at this point, Trevor May. May and McCann, a vaudeville team in the making if I’ve ever heard one, had their act together.

Formidable four-run Met lead. Largely faultless Met pitching. All that was left to do was take a generous sip of water and see how the game turned out.

(Excuse me while I wipe my desktop monitor dry.)

Trevor May stuck around to start the eighth. Apparently, he hadn’t stuck around for a second inning of work in all of 2021 when he pitched a lot, but always within the confines of one inning. Was it the right call? It’s hard to say, because May, after walking redemption-seeking Bohm, had to vacate the mound so as not to make his teammate Taijuan feel so all alone in injury purgatory. Trev & Tai: not as fun a combo as May & McCann, since the hurlers’ two right arms were linked in discomfort. Trevor’s deal was described as arm fatigue. It’s tired from not enough Spring Training, he suggested later. Not a big deal, he guessed. Walker didn’t think his situation was all that alarming, either. Pitchers know themselves until they don’t. Let’s hope they both feel swell, they both have MRIs that confirm best-case scenarios and neither finds himself grouped with Jacob deGrom in the one context where a pitcher wouldn’t crave the honor of Jake’s company. This here IL ain’t big enough for every Met arm in creation.

It’s not that you can’t have too much pitching. It’s that you can have too many innings. Based on recent samples, the eighth seems like an ideal one to eliminate. Sunday’s eighth yielded three Nationals runs. Monday’s eighth provided the Phillies with five. The math for a team that had scored two on Sunday and four on Monday would prove punishing. May to Joely Rodriguez to Seth Lugo added up to a 5-4 deficit not to be overcome when the Mets faced old acquaintance (I’d hardly call him a friend) Brad Hand. They’re on a two-game losing streak after riding a three-game winning streak. That cackle in the distance belongs to beleaguered Alec Bohm, proprietor of the last laugh until the next grounder flummoxes him.

by Jason Fry on 11 April 2022 12:27 am One of the earliest lessons for a baseball fan is that you cannot, in fact, win them all.

The Mets proved that to themselves and fans new and old Sunday afternoon, falling 4-2 to the Nationals. Squint a little and there was a lot to like, most importantly an encouraging performance by Carlos Carrasco, whose 2021 was undone by lingering injuries and then by a baffling failure to perform, problems which might or might not have been the same thing. On Sunday Carrasco looked much more like the inspirational figure who’d been a Cleveland favorite, giving up a solo homer to the ageless Nelson Cruz (a long-ago paper Met) and a single to Josh Bell in the first but nothing whatsoever after that. Francisco Lindor hit a solo homer of his own, hit machine Mark Canha drove in a run to put the good guys up 2-1, and we all waited for the Mets to follow that up with a big inning that put the Nationals away once again.

We waited, and it didn’t happen.

Instead, there were failures to move runners over and then a disastrous inning in which Chasen Shreve and Trevor Williams got three runs hung on them. That brought the season’s first second-guessing of Buck Showalter, whose Sunday included neither pinch-hitting for Robinson Cano or bringing in more front-line relievers than Shreve and Williams. But hey, Shreve got in trouble by giving up a hit to a lefty, a rare occurrence that confounded the percentage play, and Williams would have escaped unscathed if not for two lousy plays in the field by Pete Alonso, which cost the Mets an out at home plate and then a double play. Lest we be too hard on Pete, let’s remember his first-ever grand slam was not even 24 hours old when he was undone on defensive woes, and not do that.

The Mets won three out of four in Washington, an excellent blueprint they’re welcome to carry throughout the rest of the year. The starters have been pretty close to spotless and the relievers not bad at all. The hitters have ground their way through at-bats and delivered two-out hits a lot more frequently than previous incarnations of the team. Players and coaches and manager have shown proper fire and indignation in the face of probably accidental beanballs, which isn’t quantifiable but still something you like to see.

There are reasons to worry, beyond the spaces in between good things that got them in trouble on Sunday. Jacob deGrom is probably the key to the Mets’ season and likely to be MIA for some time, and the starters behind the superlative JdG carry worrisome amounts of injuries, mileage or inexperience on their resumes. But there are always reasons to worry — that’s as much a baseball lesson as the unfortunate inability to win them all. The Mets head for Philadelphia having won three of four and giving us reason to hope that may be more the rule than the exception, and whatever may lie ahead, that’s not a bad way to start a season.

by Jason Fry on 10 April 2022 10:50 am It’s an axiomatic to what we do here at Faith and Fear that the Mets are front and center in life for at least six months a year, with 1:10 pm and 7:05 pm the times around which calendars get constructed, not to mention all the oddball 10s and 05s on the clock necessitated by road trips, holidays and television-partner arrangements.

But “front and center” doesn’t always mean “to the exclusion of all else.” Sometimes the rest of life gets in the way, even at 7:05 pm and even when there’s yet another prized new starting pitcher to be formally introduced.

Saturday night was the Mets debut of Chris Bassitt, recently arrived from the Oakland A’s and having introduced himself to me with an endearingly blunt assessment of why he pays an agent. But when 7:05 pm came, my phone — now the key to all Mets interactions if I can’t be in front of a TV or in a stadium seat — had been pressed into service to play music for a fundraiser at a distillery up here in Connecticut.

It was spoken for and so was I, making conversation and being pleasant company. If this sounds like a hardship, sign me up for more of them — I was at a distillery and had all the fancy bourbon I wanted, not to mention enough cheeses, meats and miscellaneous dainties to supply an army. But after some conversation and listening to a couple of speeches, I noted that the room where my phone was playing music had emptied out and most everyone in the room with me had chosen their conversational partners.

So could I … I decided I could.

Technology’s march isn’t always a succession of triumphs — witness the mixed reviews for baseball on Apple TV+. (Personally, I liked the crisp graphics, disliked the dopey parade of probabilities and thought the announcers were pleasant enough but excessively gabby.) But SNY’s new app is a very good thing. Once you’ve verified you give money to a sanctioned TV provider, you can watch it wherever you like — even, Heaven forfend, within the holy blackout zones that reduce MLB.tv largely to a vehicle for late-night baseball tourism. The SNY app includes the Channel 11 games, and if you leave the area, you can watch for a month before it requires you to toe-tap back into your home turf.

All very reasonable, particularly given the usual draconian nonsense of blackouts and exclusive territories. Pair it with a modern iPhone and well, then you’re really cooking.

I turned off the music, flipped over to the SNY app and there were the Mets, in miniature but perfect HD. (On a phone! I felt like George Jetson!) It was the fifth inning, there was no score, and Francisco Lindor — who’d subtracted a bit of tooth enamel but added a newfound regard for his teammates — had just worked out a walk to load the bases. Up stepped Pete Alonso, whose propensity for long balls has made him an All-Star Derby icon nationwide and a rewriter of record books here at home, but whose resume was missing a grand slam — an oddity akin to, I don’t know, being a traveling magician who’s somehow never extracted a bunny from a hat.

As I and a couple of interested onlookers peered down at my phone, Pete connected off Joan Adon, about whom I knew nothing except that he must have done something right given the score. It wasn’t a majestic blast, attended immediately by disconsolate outfielders or souvenir seekers in distant precincts. Still, Pete seemed pretty pleased with himself, flipping his bat away as he departed for first and hopefully beyond.

Had he? I recalled Gary Sanchez flipping his bat away as a Twin newcomer, leaving home a self-anointed hero only to discover that Target Field’s dimensions aren’t quite as laughable as those of new Yankee Stadium, which meant he was the game’s final out. It wasn’t a pleasant thing to recall, but the mind of a worried Met fan specializes in such associations.

Not to worry. The ball plopped down over the fence, beyond Lane Thomas‘s ability to have a say in the matter. Alonso had his first grand slam and the Mets and Bassitt had a 4-0 lead.

Here, we’ll add an additional bit of spice. I was watching without sound, as the best way to get to keep flouting convention is to do so in moderation. But I’d forgotten that my phone was still in music mode, supplying audio to a Bluetooth speaker in the other room.

In that room was a teenaged kid who’d been pressed into service handing out goody bags to departing fundraiser guests. Said kid, it turned out, was a Mets fan, and had been following the game on his phone as best he could. So imagine his reaction when some bearded old guy shut off the old-people music and took his phone away, only to have Gary, Keith and Ron materialize out of the aether and begin describing wonderful things to an audience of one.

I saw a little of Bassitt, with my three-minute scouting report consisting of “about a million different pitches and a peculiar arm angle that looks like mechanical hell but apparently works.” I saw Met relievers including newcomer Joely Rodriguez comport themselves blamelessly after Bassitt’s departure. I saw Brandon Nimmo do some ninth-inning hitting and scampering to tack on an additional run. I did not see Met batters lying in the dirt or having to provide up-close negative reviews about stuff vs. pitchability to a Nationals audience.

And I saw the Mets win — for the third time in the new year and the Buck Showalter era. Or the Chris Bassitt era, the Joely Rodriguez era, the Travis Jankowski era, or the Wayne Kirby coaching first while presumably unaware that I own the Mets uniform pants he wore as a lithe big-league player decades ago era.

Define this era however you like. Celebrate it while it’s the stuff of perfection. That won’t last — it never does. I’ve learned that about baseball. But I’ve also learned that means you should bask in these stretches when all is in perfect alignment and as it should be. This is the good stuff, necessarily finite and perhaps all the more enjoyable for that.

by Greg Prince on 9 April 2022 11:06 am Nationals Park was a little dim, I heard over the car radio. The stadium bulbs weren’t firing as intended, so Friday night’s game wasn’t commencing when intended. Fine by me, having mistimed my errands and running late toward what I’d looked forward to both all day and since late November. Now I’d get to hear and maybe see the Mets of Max Scherzer and the Nationals of no longer Max Scherzer from the beginning, depending on local traffic and the bringing upstairs of groceries.

I brightened up with anticipation, only to have my enthusiasm flicker a tad once I got a gander at Apple TV+’s Friday Night Baseball. Oh, it looked sharp, as far I could tell. Our household is not equipped to go wide on a production of this nature, what with perfectly functional televisions that didn’t get their master’s degrees in advanced technology, so I was eyeballing an iPad for video. The chatter from the tablet convinced me WCBS should remain my audio for the evening. It wouldn’t sync with what I’d be glancing at, but I had Howie Rose and Wayne Randazzo painting the word picture. I’d have the iPad for visual amplification. And I’d have the TV on to follow the Nets, contesting the Cavaliers for play-in seeding (busy night).

This wasn’t how Max Scherzer’s First Start as a New York Met was drawn up. This should have been a full-focus event, preferably at Citi Field, definitely aired over SNY, ideally following Jacob deGrom’s Opening Day mastery with a bookend shutout or something close to it. Not too many weeks ago, deGrom and Scherzer pitched in the same Spring Training game. Jake went three, Max went six. It was one of the more scintillating exhibitions in St. Lucie history.

But those visions were history by Friday. However one was to consume this Met milestone, the important thing is that it was happening. And it certainly did. Max Scherzer gave the Mets six splendid innings. The Nats cobbled together one run in the second, and Josh Bell nailed him for a two-run homer in the fourth (he gives those up sometimes), but otherwise three runs for a first start — particularly after the hamstring alert that pinged in Florida — was plenty satisfying for Scherzer and us. Max managed the emotions of returning in a new uniform to the scene of so many previous triumphs quite professionally.

Professionalism is rampant with Buck Showalter in the dugout…and Buck Showalter purposefully out of the dugout.

Showalter’s major move Friday night should have been writing “SCHERZER” wherever pitchers are listed on lineup cards now that one can’t say “in the ninth place in the batting order”. Scherzer’s night turned out to be not primarily Scherzer’s night. He went his six, he got his win and he is officially a Met in reality, not just on paper or in Photoshop. Those are accomplishments.

Leading your team is an accomplishment, too. Max will do that in his way. Various players will do the same, if differently. And the manager? The manager is the man in whom we invest all sorts of leadership qualities, only to be told these days that, nah, a manager doesn’t do what you think he does. Decisionmaking is cooperative and collegial with the front office and its analytics people. Players aren’t managed so much as they are handled. So manage your managerial expectations and don’t pin on Buck as much blame as you pinned on his predecessors when something eventually goes wrong.

Yet I’m ready to credit Buck coming out of the gate here in 2022 because I heard — then saw — Buck come charging out of the dugout in the top of the fifth inning Friday night after Francisco Lindor was hit on the C-flap of his batting helmet with a rising fastball from Steve Cishek. Lindor was down on the ground in an instant. Showalter was on the field wanting to know “WTF?” in so many words an instant after that.

Four Mets had been hit in the first fourteen innings of the season. Showalter knew that. More Mets seem to be hit per capita than members of anybody else in the majors. Over the past four seasons, no team has taken more hits to the body, with the Mets taking 307 for the team between 2018 and 2021. Add in the three from Opening Night, then Lindor, and that adds up to too many. Only so many pitches can be chalked up to having simply “got away” from so many pitchers. We don’t mind the base the batsman is awarded. We’re fed up with how the batsman (or his pinch-runner) finds himself there.

Buck’s been the manager since December organizationally and since Thursday night practically. But you think he doesn’t know the epidemic proportions of HBPs to which the Mets have been subject? You think there’s anything relevant Buck doesn’t know? Friday night he knew it was time to say something, say it immediately and say it loudly.

The umpires listened. The players on both sides heard it. In a blink, everybody was on the field. Lindor, thankfully, was up on his feet and feeling (he said) no ill effects. No punches were thrown. Provocation was in the air. Bloodlust maybe not so much. The point was the Mets were sick of being human dartboards, no matter that the targeting may have been unintentional. Throw your pitches better, was Buck’s essential message to the Nationals. “I don’t really want to hear about intent,” Showalter elaborated afterward. “When you’re throwing up in there, those things can’t happen.” The man is so savvy, he can manage two teams at once.

I don’t believe Cishek was aiming at Lindor. I don’t believe any Nat was aiming at any Met the night before. I also believe you can’t just pick yourself up, dust yourself off and trot to first without at least one highly audible ahem. That’s what Showalter brought to the field. That’s what his players brought in support. “There’s not one guy I didn’t see,” Lindor said about being surrounded by so many Mets, “and I appreciate that. That, to me, shows unity.” The umpires interpreted the collective throat-clearing correctly. They tossed Cishek as an “aggressor” amid the hopped-up milling about (not so much for the actual pitch) and they sent ex-Met coach Gary DiSarcina, now in the Nats’ employ, to join Cishek in selling seashells by the seashore for what they judged pot-stirring motions. Showalter wasn’t ejected or told about asses in jackpots. Buck made a defensible baseball decision. He did the right thing.

Buck may not have been seeking ownership, but Friday indeed became Showalter’s night. He changed the tenor of the evening, the series, potentially the season. “I’m super proud to be a New York Met,” Lindor said later. The whole scene, once it appeared Francisco didn’t incur injury, was reassuring to process, whatever media platform one chose to absorb it via. No less reassuring was Scherzer — warned not to retaliate — going out for the bottom of the fifth and mowing the Nationals down on a dozen efficient pitches.

The Mets were leading before the dust coalesced; they were leading when the dust settled; and they led after the game that had at started at dusk and ended near midnight turned to dust destined to be put in the books (or iBooks). A ninth-inning downpour didn’t help MLB in its attempt to showcase whatever it was trying to prove with its streaming exclusive. The game may have looked sleek on devices worldwide, but baseball will take its sweet time when the lights won’t work, when the tarp comes out, when the teams have to be separated from one another, and when a new pitcher has to be called in to replace an ejected teammate. The Mets devoted a hefty share of the three hours and forty-three minutes it took to play this game — not counting fifty-two minutes of electrical and meteorological delays — scoring seven runs, using five separate innings to effectively grind their offense and post their tallies. That was pretty sweet, too.

Jeff McNeil celebrated his birthday with his and the team’s first home run of the season, blowing out the candles for three RBIs in all. Robinson Cano had a big hit. Starling Marte had a couple. The relievers who followed Scherzer — Drew Smith, Seth Lugo and Sean Reid-Foley — allowed no runs among them. We’d complain if they had, so we should acknowledge they didn’t. Oh, and the Nets beat the Cavs; Durant scored 36. (Like I said, busy night.)

The 7-3 victory sounded crisp on the radio because we have Howie and Wayne, and theirs is a crystal clear stream of accounts and descriptions, intermittent AM static notwithstanding. I would have liked the option of the usual Met-centered telecast, but it wasn’t there. Apple apparently wants to stamp these productions with their own talent, otherwise they might want to think about putting to good use announcers who are already in town, maybe pairing one of the available visiting voices with a home team counterpart, thus giving everybody who’s actually interested in the game the most pertinent insights available. It was the only good thing the mid-’90s debacle known as The Baseball Network ever tried (it even got Bob Murphy back on television for a few nights).

I don’t want to be totally dismissive of this effort to “grow the game”. Perhaps somebody was genuinely excited that Apple TV+ had the Mets-Nationals game on its app and perked up to the broadcasters they hired to call and comment on the action. Maybe I missed out on the ground floor of something historic — besides Max Scherzer’s first pitch as a Met while putting away paper napkins and kidney beans. I’m good with that. Again, I had Howie and Wayne. The supermarket where I did my pregame shopping sits around the corner from an evangelical church. They had a sign out front that said HE IS RISEN. No, I thought later, HE IS ROSE. And when it comes to the Mets, his word is gospel.

by Greg Prince on 8 April 2022 10:37 am Wait. Wait a little more. Wait just a little more.

Now. Now you can have your Opening Day. I mean Opening Night. I mean Opening Night win. It’s yours. No strings. No hamstrings even, as far as we know. It arrived in our laps a little bruised, a little soggy and a little too late to be accepted in total alertitude, but at the end of the day/night and on the morning after, it’s clean and it counts.

Are you happy? Why shouldn’t you be? Because instead of COVID-19 locking everybody in until late July, as it did in 2020, or just the positive-testing Nationals with the Mets as collateral bystanders, as it did in 2021, the Major League owners conspired to lock everybody out until the middle of March? That? That was so one month ago. Spring Training simultaneously waited and rushed. It didn’t rush quickly enough to get us to the previously agreed upon date that was going to open 2022. So we waited an extra week. Opening at home on March 31 at one in the afternoon was out. Opening at Washington on April 7 at four in the afternoon was in.

Except rain was in the DC forecast, so four o’clock became seven o’clock, a sensible move. The forecast was righter than rain, so first pitch had to be pushed back another 76 minutes. The Nationals needed not only to dry the field but extravagantly introduce approximately every member of their support staff plus most of the residents of the region known colloquially as the DMV (for the District, Maryland and Virginia, not for sitting through ceremonies taking as long to complete as a trip to renew one’s motor vehicle registration). If the Nats were to lose, it wouldn’t be for lack of acknowledgment of support staff. After Nationals Park public address announcer Jerome Hruska dug deep to discover syllables in “JOSH BELL” that the Nats’ first baseman had no idea he had in either his first or last name — we wish Mr. Hruska’s throat well — and both pomp and circumstance dutifully tipped their caps, it was time to…oh, what was it we were waiting for the Mets to do for so long?

Right. Play ball. I mean PLAY BALL! You don’t need to be Jerome Hruska to cry those words out in excitement.

At 8:21 PM Eastern Rainlight Time, we proceeded. Starling Marte stepped in. Patrick Corbin delivered. And we were off on what projects as a 162-game journey. The Mets didn’t play 162 games on Thursday night. It only felt like it took six months.

Nah, it was a mere three hours and thirty-one minutes, and if you didn’t nod off briefly during the duration (which I must admit I did), you came away beaming from five runs for the Mets and only one for the Nationals. That’s a 5-1 Mets win, in case you’re out of practice remembering how this stuff works. The Nats were the losers here, and the Braves lost their first game, too. The Phillies and Marlins were idle. The Mets are alone in first place. In a wet spring when everything’s been late, it’s never too early to enjoy whatever we can.

Game One might have loomed as too early from a starting pitching standpoint, what with Jacob deGrom likely available no sooner than June and Max Scherzer needing an extra day to certify his hammy sufficiently loose to stick it to his former team, but you can’t say Tylor Megill wasn’t right on time for this affair, whenever it started. Megill’s Opening Night in the majors was only last June. I saw him before I really knew who he was. I was impressed then. I’m more impressed now. Unmoved by the season’s inaugural ceremoniousness and unwilling to succumb to self-imposed pressure, Tylor simply dealt. He shut out the Nationals of Juan Soto, Nelson Cruz and whoever else Hruska thrust into the vocal stratosphere for five innings, outpitching and outlasting the exponentially more decorated Patrick Corbin. Score one for the “just another game” crowd this Opening Night. Still, let’s not treat what Tylor did as ordinary. It was Opening Night! That’s something to rope off and treat with white gloves. Given the sense of occasion that belongs only to Game One, let’s call Megill just another Seaver, Gooden and deGrom, to name three starting pitchers who’ve tidily racked up Ws to commence Met campaigns.

Five of the Mets’ eight new players played and their collective contributions were palpable. Right fielder Marte, third baseman Eduardo Escobar (the Mets’ 179th man on third) and center fielder Mark Canha combined for four hits and displayed sound defense. Middle reliever Adam Ottavino threw a scoreless seventh. Travis Jankowski entered as a pinch-runner for someone simultaneously old and new, Robinson Cano, playing again at 39 after a year’s suspension for PED use. Cano had two hits, including a beauty of a bunt that laughed in the face of a Nationals’ shift. Cano belongs in that conversation of ballplayers who can fall out of bed and line a single to right in the dead of winter, assuming he’s eligible to lace up his slippers.

The Mets as a unit rapped out a dozen hits, worked four walks and absorbed three baseballs to the body. One wishes to assume each pitch got away from whichever Nat threw it. One also hopes Buck Showalter and Jeremy Hefner suggest a little high-and-tightness to Scherzer when he goes tonight. One believes Scherzer won’t have to be told. (Ah, pastoral baseball, where we only thirst for blood when we perceive we’ve been wronged.) James McCann was plunked twice, the first time on the foot with the bases loaded, so that surely wasn’t intentional. The pitch that dinged Pete Alonso looked as if it could have been serious, and he exited to be examined. As everybody’s favorite diagnosis goes, they looked at Pete’s head and found nothing.

This first game featured the first regularly scheduled designated hitter in Mets National League history, if we don’t count Interleague interruptions or the improvisation of 2020. That claptrap is here to stay, permanently upsetting longtime fans who use phrases like “claptrap”. I’ve decided to not be an ostentatious lost-causer about the removal of the bat from the pitcher’s hands. I mean, yeah, at heart, I will never give up on the notion that the ninth spot will rise again, but for practical purposes, I can’t bang the traditionalist’s drum every single game that has a DH because, well, every single game has a DH and you can only make so much noise to no purpose for so long (ask Jerome Hruska). J.D. Davis, who has always scalded Corbin, got the gig on Night One and chipped in a double, initially supporting the theory that the Mets have always built their roster with a surfeit of designated hitter types.

Megill, incidentally, was the last Mets pitcher to get a hit, in Atlanta last October. Just sayin’, as they say.

Showalter, meanwhile, surpassed Carlos Beltran, you, me and your uncle (unless your uncle is Joe Torre) on the all-time Mets wins managed list, notching his first. I look for Mike Cubbage and Salty Parker to be breezed by pretty soon. Buck, if you haven’t noticed, has been around. Every win for a while will seem the product of his wisdom and experience. I’m willing to go with that until we have some reason to derive dissatisfaction from his reassuring presence. We’re Mets fans. We’ll find one. I thought it might be Buck’s opting to insert Edwin Diaz into the ninth inning despite it not being a save situation and the non-save situation transpiring at National Park, where Diaz’s lifetime ERA is pretty close to infinity. The manager and the reliever got away with that one. Or maybe they’re both better at what they do when we believe we would be.

Whatever our irks, we are conditioned cheer a solid win like Thursday night’s; a triumphant return like that of Gary, Keith and Ron to on-site road telecasts; and the knowledge that even if 1-0 won’t necessarily become 2-0 (and we won’t see it without activating Apple TV+, automatically pre-empting GKR) baseball is back. No matter the indignities of lengthy lockouts, nearly as lengthy replay reviews (whose imperfect outcomes are now at least announced by umpires, as if that’s an innovation) and ubiquitous ads informing us we’d sure enjoy this rite of renewal a lot more if we put some money on it —all you kids out there, bet the over on time of game — we flocked back for this and most of us will keep flocking regardless of routine-disrupting streaming, gambling come-ons, rule changes we didn’t ask for and general slogginess.

We love coming together for a baseball season. We are forever flocked that way.

by Greg Prince on 7 April 2022 1:50 pm Steve Martin as Navin R. Johnson exclaiming, “The new phone book’s here!” in The Jerk has nothing on us in terms of ginning up excitement over the mundane, which is to say, the new roster’s here!

Specifically, the active roster of 28 players the Mets will carry into battle (or the first baseball game of the year; enough with the militaristic metaphors). This much-anticipated directory lists eight Mets who’ve never been Mets before, yet as soon as they take the field, the mound, a plate appearance, they will be Mets for real. Soon you’ll know them by their Met deeds. Welcome aboard to…

Eduardo Escobar

Mark Canha

Starling Marte (whom Ralph Kiner likely would have called Steve Martin at least once)

Chris Bassitt

Adam Ottavino

Travis Jankowski

Joely Rodriguez (the lefty reliever acquired over the weekend for Miguel Castro, whose only sin in these expansive bullpen days was not being a lefty)

Oh, and that Max Scherzer fellow!

If you’re scoring at home (or even if you’re alone), we enter 2022 with 1,153 Mets on the all-time roster, a document Navin Johnson would faint over. Doing the math will be your pleasure as to what that total will be once each of the aforementioned gets in a game.

Welcome aboard anew to Chasen Shreve, the 2020 Met slated to become the 54th Recidivist Met in franchise history (Recidivist Mets are Mets who left the club, played for another big league club, then came to his senses and back to us in that order.)

Welcome back is also due for Robinson Cano, who took off 2021 at the suggestion of the commissioner.

Two Mets among the 28 active remain from Mets playoff clubs of the past: Brandon Nimmo and Seth Lugo, neither of whom have yet played in a Mets playoff game, but they were here in 2016 and they had something to do with us winning our most recent Wild Card. Jacob DeGrom, who debuted in 2014, is the elder franchise longevity statesman and the only Met at the moment to know what it’s like to participate in a Mets postseason (four starts, all on the road in 2015), but our ace of aces, as you might have guessed, starts the season on the IL.

From the 2017 Mets and joining us for 2022, are Dom Smith and Tomás Nido.

From 2018 and still here: Luis Guillorme, Drew Smith and Jeff McNeil.

The 2019 debut crew, besides Cano: Pete Alonso, Edwin Diaz and J.D. Davis.

Except for Shreve, nobody who became a Met in 2020 is a Met in 2022.

And your new-for-2021 Mets who managed to stick it out for the new year: Francisco Lindor, James McCann, Trevor May, Taijuan Walker, Sean Reid-Foley, Opening Night starter Tylor Megill (I wonder if the Official Sports Betting Partner of the New York Mets gave odds on that), Carlos Carrasco and Trevor Williams.

Time flies, huh? Will the Mets soar along with it and put the majority of these guys in the playoffs as Mets six months from now? The telling begins tonight in Washington.

Remove the tarp ASAP and play ball already yet!

National League Town can help you fill the additional hours bad weather in Washington is making you wait for first pitch. Listen to Jeff Hysen and me mull over the season ahead here or at the podcast platform of your liking.

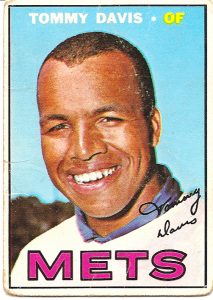

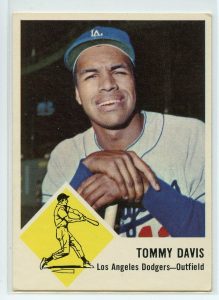

by Greg Prince on 6 April 2022 5:32 pm Baseball said goodbye this week to 83-year-old Tommy Davis, the two-time National League batting champ, the RBI king whose 153 in 1962 were the most in the NL in 25 years and would be the most in the NL for another 36 years, and the first American League hitter to make the most out of being designated on a daily basis (as an O, he was the only regular DH to crack .300 in the unfortunate experiment’s first year of 1973). There were any number of angles from which fans could remember and appreciate Davis and the career that encompassed 18 seasons spent with 10 teams.

I remember Tommy Davis as my gateway Met — his 1967 Topps card may very well have been the first picture I ever held in my hands where the word “METS” caught my attention — and I appreciate him for that. It doesn’t matter that by the time I understood what the Mets were and that I couldn’t live without them Tommy was no longer among them. It didn’t matter that once I had a little actual fandom under my belt and circled back to my 1967 Tommy Davis card I discerned he wasn’t wearing any item of clothing with a Mets or New York insignia. Not so much as a pinstripe was in evidence. Topps knew how to take a picture of a ballplayer from the shoulders up, hat removed, just in case that ballplayer moved on from where he was being photographed.

“Hey, kid, wanna root for my new team?” But I didn’t know that when I initially encountered Tommy Davis of the METS. The card said he was part of the outfit for which I was developing the first flickers of affinity. The jerseys and caps I’d latch onto later. For now, “METS” sufficed to entice me, with Tommy Davis their smiling emissary to a child who wanted in on whatever was making this man on the card appear so gosh darn happy.

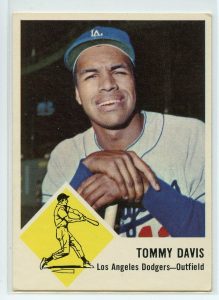

The Mets were Davis’s second major league stop. He was a kid from Brooklyn, an alumnus of Boys High, Class of ’56, who did what any boy from Bed-Stuy might have done if given the opportunity at the time: He signed with the Dodgers. In those pre-amateur draft days, he was pursued by more than one club. Recruiting on the home team’s behalf was Jackie Robinson. The kid from Brooklyn was swayed.

Unfortunately, the team from Brooklyn picked up stakes and moved to Los Angeles. Davis’s debut came toward the end of L.A.’s first West Coast pennant race as a fourth-inning pinch-hitter in St. Louis. It was a wild game. Tommy was batting in place of Clem Labine, who was Walter Alston’s third pitcher of the night (his first was Sandy Koufax, who gave up four runs in two-thirds of an inning). The youngster struck out in what became an 11-10 Los Angeles loss. The Dodgers recovered to reach and win the 1959 World Series.

Davis kept moving up, too, breaking through as an outfielder who’d force his way into the Dodger lineup any way he could, starting as many as 59 games at third base in a season. The OF-3B experiment didn’t really take, as Davis remembered for his SABR biographers Paul Hirsch and Mark Stewart, “They never really explained to me how you had to short-arm the ball at third. I was throwing it like an outfielder and the ball was sailing over Hodges’s head.” That bat of his would play anywhere, though, and it looked like a sure bet to be on display in the 1962 World Series. The Dodgers had developed a star-studded cast worthy of the Hollywood glitterati that flocked to their new stadium. Maury Wills was shattering stolen base records. Don Drysdale was winning 25 games. Sandy Koufax was being Sandy Koufax (no-hitting the infant Mets along the way, almost literally taking candy from a baby). Big Frank Howard busted out with his first 30-plus home run season. And knocking everybody in, not to mention every pitch he saw, was Tommy Davis.

Tommy was “probably the best pure hitter I ever saw,” Dodger broadcaster Jerry Doggett recalled three decades later for author David Plaut. “A great clutch hitter,” teammate Ed Roebuck attested. Koufax took notice, too: “Every time there was a man on base, he’d knock him in. And every time there were two men on base, he’d hit a double and knock them both in.”

“When I see those ribbies on the bases,” Davis confirmed, “it means more money in the bank. When I see men, I see ’em as dollar signs.” Whichever teller handled Tommy’s account was kept extraordinarily busy in 1962. Let us repeat that runs batted in total: 153. It was a sum unheard of in the senior circuit since the 1937 peak of Joe “Ducky” Medwick and not surpassed again until Sammy Sosa did it in 1998. Davis’s batting average smoldered at .346, on 230 base hits, a figure not reached in the NL since Stan Musial in 1948 and not topped since Medwick in 1937. The Dodgers rode Tommy’s bat to a first-place lead that looked impenetrable. After 149 games, the Dodgers led the Giants by four games. The Dodgers turned cold immediately thereafter, however, allowing their rivals to catch them at the finish line and force a three-game playoff that echoed the New York-Brooklyn dynamic of eleven Septembers earlier. Now, with the foes having morphed into San Franciscans and Los Angelenos, history repeated itself, with the transplanted Jints sticking it to the uprooted Bums in trademark dramatic fashion.

Down a stretch that lives in the same tier of Dodger infamy where 1951’s resides, Tommy Davis, from Game 150 through Game 165 (that playoff set counted as a regular-season series), hit .394 and drove in 14 runs. He didn’t get the MVP — Wills’ 104 steals were too obviously history-making; and he didn’t go to the Fall Classic — Willie Mays led the Giants there with his own Most Valuable-caliber campaign (49 homers and 141 RBIs not to mention being Willie Mays in center field); but Davis could lay as much claim

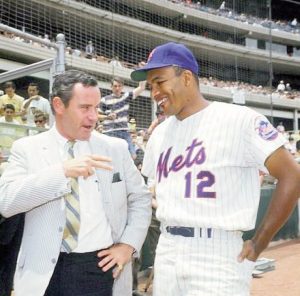

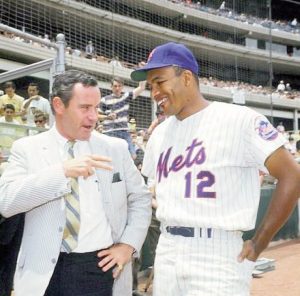

Being in New York suited a star who originally signed with his hometown Brooklyn Dodgers. to 1962 as anybody this side of Casey Stengel.

To say Davis would never repeat 1962 is to say nothing that diminishes the rest of his career. If 230 base hits and 153 RBIs were easy to replicate, they would have been garnered far more often by many others. Tommy’s 1963 encore was good for another batting crown (.326) and a no-doubt pennant en route to a four-game sweep of the Yankees in the World Series, a World Series that saw Davis lead all hitters with a .400 average.

Tommy Davis was at the top of the baseball world in the fall of ’63. Three years later, a span that included a gruesome broken ankle that derailed his prime, he’d be traded to the Mets. The Dodgers won the 1965 World Series without him and another flag in 1966 with him (when he batted .313 in 100 post-injury games). They were the Dodgers, the flagship name in their sport, whereas the Mets were…you know, the Mets. His stock had plummeted, à la John Olerud’s on his trip from Toronto batting and world champ to suddenly a Met in the mid-’90s. But coming to the Mets was OK by Davis, because it meant he was coming home. When he was asked about such a trade in theory, while still at work in Southern California, Tommy wasn’t reticent to embrace the notion — a geographic inverse of the sentiment that would frame Darryl Strawberry in a less than glowing light in 1988: “I love New York,” he told a couple of reporters from back east who were visiting Dodger Stadium in the midst of that last L.A. pennant chase. (He also maintained a special rapport with the gentlemen of the press from the media capital of the world. As George Vecsey recalled this week, “As soon as he sighted familiar faces — or heard familiar Noo Yawk accents — Tommy would turn to his teammates and announce, ‘Hey, these guys are from my hometown.’”)

If you believe in reasonably happy endings, the second stop of Tommy Davis’s baseball career should have been his last, or at least among his longest. Kid from Brooklyn, now an older/wiser veteran, setting up shop in Queens. He can still hit. He can tutor the outfielders of the Youth of America Cleon Jones and Ron Swoboda. The Mets climbed all the way to ninth place in 1966. Would it be too much to ask that fate position Davis and the Mets in harmonic convergence as the Mets reach for the moon, with Tommy guiding his juniors on their lunar mission?

Yeah, it would be. If things worked poetically, the main Met traded to the Dodgers to get Davis, Ron Hunt (who went west with Jim Hickman), would have stayed a Met long enough to help directly instigate 1969. Hunt was the Mets’ first more or less homegrown star. Hunt was supposed to be a harbinger of truly better times ahead, not sent away when 95 losses represented vast improvement. But Wes Westrum wasn’t as crazy about Hunt as Stengel had been and Alston was never too crazy about Davis and the deal got made shortly after Thanksgiving weekend of ’66.

“New York is my hometown and I’ve always loved the fans,” is how Tommy greeted the news. “My mother still lives in Brooklyn and all my relatives have been calling her and congratulating her that I’m coming home. So you’ll see I’ll be playing in familiar surroundings.”

Local Huntlessness notwithstanding, Davis’s return to the five boroughs — he was a lifetime .389 hitter in 54 Shea Stadium ABs and something about the baseball cards of his that were shot at the Polo Grounds always looked just right — made so much sense. As George Vecsey speculated in Newsday, this new acquisition “could be a solid hitter for the Mets, who have never had a solid hitter.” The Mets had been in business five years. It wasn’t much of an exaggeration.

“Davis will be in left field and he’ll play every day,” Westrum announced, offering Tommy a better deal than he was receiving in L.A. under Alston. “I can’t hit unless I play regularly,” had been Davis’s gripe (shared by most players). Now, on a new team and taking stock of the homey atmosphere, Tommy added, “I expect to go the full season and play to my capacity.” By Spring Training, he was also ready to fill that ideal role of veteran mentor, telling Jim Selman of the Tampa Tribune he liked what he was seeing from his fellow Met outfielders, “I see a lot of potential here. Take Cleon Jones. […] Ron Swoboda hits the ball good. If Jones and Swoboda can improve their fielding, they could be 10-year men.”

The Mets and Davis were hardly an odd coupling. Westrum indeed played Davis regularly and Davis returned the Met manager’s confidence by going the full season and playing to his capacity. In 154 games — 149 of them as the starting left fielder, Tommy batted .302. Only Ron Hunt in his All-Star starting season of 1964 (.303) had topped him among Mets with enough plate appearances to qualify for the batting title. Davis’s 73 RBIs were the third-best by any Met to date, bettered only by Frank Thomas’s 94 in ’62 and Joe Christopher’s 76. His 16 home runs led the 1967 Mets, whose most satisfying victory among 61 may have been the May night when Jack Fisher went 11 innings for a complete game W captured in walkoff fashion by Tommy Davis’s walkoff dinger. No Met pitcher had ever gone longer in service a route-going triumph, and no Met pitcher would ever go longer and be rewarded with a win. Yet Fisher couldn’t have been any more satisfied than Davis after he crossed home plate at Shea Stadium to beat the Reds.

“This,” he said, “is the first time I’ve had anything to cheer about since 1963.”

All of what Davis did in 1967 wasn’t enough to keep the Mets from sliding back into the basement and nothing the Mets could do, including promoting Rookie of the Year Tom Seaver, was enough to keep Wes Westrum from resigning in September before he’d find himself fired, but the comeback performance got some BBWAA member’s attention, because when the MVP voting came out after the season, Tommy Davis landed in eighth place on one writer’s ballot. It was a far cry from the 20 first-place votes Orlando Cepeda attracted in winning the award unanimously, but the tenth-place Mets finished 40 games behind Cepeda’s eventual world champion Cardinals. As small miracles go, Davis emerging from a severe ankle injury in ’65 and Walt Alston’s afterthoughts in ’66 to gain mention among the most valuable players in the National League in ’67 for a ballclub whose record nobody much valued rates as more than a footnote.

So does Tommy Davis’s one year as a Met. One year was all it was, but it was a very complete year in a very specific sense. Fifty or so players have been Mets for exactly one season. That is one season from Opening Day to Closing Day, no demotions to the minors, no time on the DL/IL, no military service, not even paternity or bereavement leave. They were brought up or brought in; they did their part for the orange and blue to their capacity, as Davis put it prior to 1967; and then, for one reason or another, they were gone. The reason was usually the business of baseball. In Davis’s case, the business was about filling center field, a void that during the 1960s vexed the Mets the way catcher did until Jerry Grote and third base until…well, that would vex on and off for a while.

Despite Davis’s rock-solid presence in left for six months, the 1967 Mets were a team in flux. They used 54 players, the most they’d use in a single season until 2018. Their manager, as noted, quit. Their general manager, the skilled Bing Devine, longed for home in St. Louis, sort of the way Davis had for home in New York. Executives had more agency than players. Before Devine departed, he laid the groundwork for a trade very much meeting with the approval of the new and highly valued manager of the Mets, Gil Hodges (the same Hodges to whom Davis had trouble throwing accurately when they were corner infielders together in L.A. early in the decade).

Gil Hodges very much wanted Tommie Agee in center field. He’d seen him look dashing in the American League, when Hodges managed the Senators and Agee flashed onto the scene for the White Sox. Chicago was willing to give up on Agee, the 1966 AL Rookie of the Year, because of his perceived offensive shortcomings after the Sox fell shy of the pennant in ’67. “The first thing Hodges wanted to do when he became manager,” Johnny Murphy, who succeeded Devine as Met GM, explained. “was to acquire Tommie Agee. He wanted a guy to bat leadoff with speed and that could hit for power. He also…needed a guy in center to run the ball down.” This was in the wake of one more Met center field experiment — the briefly ballyhooed Don Bosch — deteriorating on contact. Bosch started in center on Opening Day 1967, keeping the job for 15 of the Mets’ first 20 games, the 20th of which was on May 4. He’d get three more starts out there over the next month and then disappear from the lineup until September. Bosch’s batting average for the season (when he wasn’t shuttled to Jacksonville) was .140. So, yeah, the Mets were still keeping an eye peeled.

“We had to plug the hole in center field,” Murphy elaborated. “We’ve never had a center fielder. We’ve tried to develop our own and to trade for one, but we have never had any success. Now we’re getting a fellow we know can field and run and hit for power.” It was nothing personal toward Davis that as the best chip the Mets were willing to exchange, he was gonna be the outfielder the White Sox would get back. “Tommy did a good job,” Murphy affirmed. “Nobody here is mad at him. He played hard, and he played twice as many games as anyone expected. We simply are dealing for a need, a center fielder.”

The trade went down in December: Davis, Fisher, pitcher Billy Wynne and catcher Buddy Booker for Agee and infielder Al Weis. If you’ve read this far, you know the trade worked out spectacularly for the Mets. Agee had a rough 1968 but a transcendent 1969. Jones, who moved over to left, blossomed, too. Swoboda may not have had quite as long a career in store as Davis predicted for him (only nine years in the bigs), but boy, was he about to have his moments. The miracle these outfielders and their teammates — very much including Weis with his .455 World Series batting average — would overshadow essentially all of the incremental progress the Mets who didn’t make it to the mountaintop with them had forged. The Mets’ story, unless you were willing to get granular, was they were born a laughingstock; they languished; and then, as if out of nowhere, they rose to an apex unmatched in the annals of human achievement.

I’m fairly comfortable with that story in broad strokes, but granularity and the knowledge that the 1969 Mets didn’t exactly come out of nowhere has its appeal. I wasn’t watching in 1962; Channel 9 didn’t air in utero. I missed the extended infancy and toddler years. But sometime before fully discovering the Mets, perhaps when I was four, maybe five, I shuffled through my older sister’s short stack of baseball cards and decided Tommy Davis and METS were for me. As would be the cards once she grew bored with them. Maybe I’ll never fully appreciate how futile the Mets felt prior to 1969, but I’d like to think I can appreciate that there were Mets prior to 1969, and some of them, like Tommy Davis, left their mark on their times as best they could.

Could have the Mets won their division, their pennant and their world championship without Tommie Agee and Al Weis? It’s never occurred to me to ask. Why would I want the Mets to have been one iota different from what they were when they were at their most miraculous? Yet a person who’s familiarized himself after the fact with the Mets from when they attempted to master the conversion of their unsteady crawling skills into walking does wish, with loads of hindsight, that somehow Tommy Davis could have stuck around a little longer and been a part of 1969 and 1970 and kept being at home in New York (this same person also wishes Ron Hunt could have enjoyed the fruits of what his pre-trade contributions sowed, yet there’s not an alternate timeline handy that will accomplish every ancillary wish). Tommy joked more than once that because he played such an intrinsic role in building the ’69 roster, maybe the Mets should have awarded him something like half a World Series ring. “You’d think the Mets would send me something for helping them win,” he told his SABR biographers. He was no more than half-serious. I don’t know if he was any less.

Tommy Davis’s career was about half-over when he left the Mets. He may not have been in the best mood when he was told his tenure at Shea would be limited to one year. “Puppets have no feelings,” he said in the middle of December 1967. “We just have to go where our livelihood is. I’m glad to go with any major league club that wants me.” Yet, by the reckoning of Joe Donnelly in Newsday, Tommy was putting a stoic face on the situation because “a few nights” before the transaction, Davis declared, “I want to stay with the Mets. The club has been great to me. The fans, well, they’re unbelievable. I want to be an Ernie Banks.”

Banks had been a mainstay with the Cubs since 1953 and would be through 1971. Even in 1967, before the reserve clause was lifted, that kind of staying power was tough to cobble together for a baseball player, no matter how immortal. Banks would stay in one place. Mays wouldn’t. Hank Aaron wouldn’t. Frank Robinson had already been traded once and would be traded again. Tommy Davis was going to his third team. The second team, despite not being ready for prime time, gave Tommy the time he needed to prove himself anew. “By having a decent year,” he reflected in 2011, “I was able to play until 1976. I was certified good enough to play, thanks to 1967 with the Mets.” For that reason, Davis told his SABR biographers that he considered 1967, regardless of the ring he earned in 1963 (and the ring he wouldn’t be sent in 1969), the most significant year of his career.

Prospective contenders would continue to covet Tommy Davis, and he moved town to town, up and down the standings, forever a cog in somebody’s machine (though never Cincinnati’s). After his year with the White Sox, there’d be stints with some pretty good to very good Astros, Cubs, A’s, Orioles and Royals clubs, along with the Angels as he approached the end of his line. The Yankees, who missed out on him in 1956 when Jackie Robinson convinced him to be a Dodger, gave him a Spring Training look-see on the eve of their pennant run in 1976. “The designated hitter is taking care of this old man,” he said as he reached the twilight of his career. “It sure has helped me bring home the paychecks.”

In 1969, there was a stretch with the expansion Seattle Pilots, meaning there was a supporting part for him in the most influential baseball book of the twentieth century, a project to which he gave his blessing (not every ballplayer mentioned was so generous). “Jim Bouton was my teammate in both Seattle and Houston,” Davis told This Great Game in 2005, “and he mentioned me a few times in his book, Ball Four. […] Many players believe that anything that happens in the locker room should stay there, but I’m not an advocate of that. But, I’m not mad at him and I never was, because everything he wrote was accurate and he was honest. I know the Pilots manager Joe Schultz thought it was a distraction, but I thought it was well-written and damn funny.”

In all, Davis played one game shy of 2,000 and recorded more than 2,100 hits. He retired in the winter of 1977, just as the first class of free agents was able to hit the market and find the best deals for themselves. For many years, he’d work in community relations for the Dodgers, even if the Los Angeles community wasn’t initially his home. To be fair, even when he missed New York, he did admit he adored the Pacific Coast weather. No doubt the SoCal sun shone brilliantly on Tommy Davis when his star shone brightest. When he died, he was remembered primarily for what he did in 1962 and 1963. Still, we shouldn’t forget the year of his professional life he gave us in 1967. I’d say that even if I didn’t always love that baseball card.

by Greg Prince on 2 April 2022 9:48 am Pity the newsbreaker tasked with delivering momentous tidings on April 1, a date which, for some strange reason, gives everyone processing such information pause to wonder if it’s real. Indeed, it would be swell if the bulletin from the late afternoon of April 1, 2022 — that Jacob deGrom’s right shoulder is something short of shipshape and Bristol fashion — were standard lazy gag fare.

But, of course, it’s not. We were prepped for the sharp elbow to the face the night before when word went forth that Jake’s business shoulder was feeling tight, serving as a harbinger for the condition of the pit of our stomachs approximately seven seconds later. Jake wouldn’t be pitching Friday’s pretend game. Would Jake be pitching the following Thursday’s real game, the one slated to start the already delayed season?

We learned Friday he won’t be. Or any games for a while. How long that while will last can be calculated via the Metropolitan abacus or whichever app you have handy. Take how long they say he needs to rest (four weeks); add how long you’d figure working out and ramping up will take (at least a month); factor in setbacks (because when aren’t there setbacks?); remember this is the Mets we’re talking about; and it was nice knowing you, Jacob.

I don’t really want to be that way. It’s a stress reaction in deGrom’s right scapula, not a tree falling in the forest directly on his head. Nevertheless, we make a sound akin to “AAUUGGHH!!” no matter how conditioned we are to learning Jake will miss his next start(s). This was going to be The Year of the Two Aces, the best pitcher in the world who’s always been ours and the other best pitcher in the world who somehow is also ours. DeGrom and Scherzer/and to opposing batters murder! The good news is Max Scherzer’s hamstring tweak is said to be no real issue.

The bad news is WHAT DID YOU JUST SAY ABOUT MAX SCHERZER’S HAMSTRING?

Welcome to the Mets, Max. You probably didn’t even know you had hamstrings until you got here. We didn’t know the human anatomy comes equipped with all kinds of fragile doodads until we became Mets fans. Take the scapula, that bone that connects the humerous with the clavicle (now I hear the word of the Lord). The scapula sounded familiar when Jacob’s was diagnosed. Matt Harvey had a scapula. I suppose we all have them, but it was Harvey’s scapula that, among other things, kept Matt from continuing to be Matt in 2017. He was out a couple of months and very shy of pitching remotely like the same Matt Harvey we’d known and idolized once he came back. Not that Matt Harvey by then more than loitered at that level, so let’s not lump all Met scapulas into one enormous pile of deGromified anxiety.

Have you ever heard of a scapula in any context other than a Mets pitcher having problems with one?

“Hey, Ted, how’s the scapula?”

“My scapula’s doin’ great, Harry — thanks for asking!”

Nope, never happens. No wonder the word “scapula” has such a low Q rating.

DeGrom’s popularity, on the other hand (the one he’ll have to use if he wishes to pick up a baseball in April), has always been stratospheric with the likes of us. We love Jacob deGrom. We wish Jacob deGrom could pitch every fifth day and then some. Jake and Max and three days of Jake because we can’t get enough Jake. Now, as far as we can tell, it will be Max, followed by that nice Chris Bassitt fellow — his first start to beam over Apple TV+, apparently — then Taijuan Walker, Carlos Carrasco, Tylor Megill/Trevor Williams/David Peterson or whoever doesn’t have a scapula reacting to stress. Trade talks are in the air as well. So who knows?

We knew we had Jacob deGrom to throw our first pitch of 2022. Now we know less than we used to. Here’s to a speedy and comprehensive recovery for Jake. And for us.

|

|