Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

It was a glorious time…

It was when I met the world.

—Henry Hill, Goodfellas

Like the Mets are doing in 2020, the Mets fans of 1970 spent their summer at day camp. Well, this Mets fan did. Others, too. Based on personal recollection, if you were a kid in day camp in 1970, there’s an excellent chance you were a Mets fan.

And if you were a Mets fan in the summer of 1970, whether attending an area day camp, romping around in a neighbor’s backyard inflatable pool or biding your time until the Good Humor Man jingled down your block, Tommie Agee was a name you knew and mentioned daily. Tommie Agee was fun to say. Tommie Agee was fun to watch.

Fun. Mets. Agee. Summer. Throw in those ice cream bells and, when you got right down to it, what else do you need when you’re a kid?

Fifty years ago this summer, life was good. The defending world champion Mets were good. Tommie Agee was better than good. Maybe not great in the named to the All-Star Game sense, but plenty good enough for we who’d gotten our feet wet the previous fall and now, in our first full summer as Mets fans, were letting the water rise above our ankles, then our knees, then our waist. Before we knew it, we were fully immersed.

We had the Mets. We had names that my formerly seven-year-old brain has “1970” imprinted all over them regardless of my or their other summers. When you’ve had the 1970 Mets, it doesn’t automatically occur to you they’d been or would be anything else.

We had pitching like few others had. We had Tom Seaver, who wasn’t enough all by himself, but I swear he came close. We had Jerry Koosman, Gary Gentry, Jim McAndrew and Nolan Ryan, all of whom were talented even if none of them was quite Seaver and the latter of them was frustratingly wild, but boy could he throw hard. We had Ray Sadecki and Bob Murphy’s pronunciation thereof as if he were a Charoesque one-word phenomenon (“Raceadecki”).

We had Ron Taylor and Tug McGraw coming out of the bullpen because sometimes our starting pitchers didn’t throw complete games. We had Danny Frisella, who threw a forkball, and Cal Koonce before the Mets let him go, and Rich Folkers, once the Mets brought him up. We eventually had Ron Herbel and Dean Chance, too, because it turned out our pitching wasn’t always as extraordinary as we’d been told, but day camp was over by then.

We had Jerry Grote catching them all, except in the second games of doubleheaders, when we had Duffy Dyer. We had Buddy Harrelson and Ken Boswell turning double plays and rarely making errors. We had Donn Clendenon driving in so many, many runs. We had Ed Kranepool briefly demoted to Tidewater, but he came back and never went away again. We had Joe Foy, who I knew mostly from an old card I had that said Red Sox, and Wayne Garrett, whose card I didn’t have. Garrett had red hair, it was mentioned on TV, but we didn’t have a color TV, so I had to take the announcers’ word for it.

We had veteran Al Weis coming off the bench; and rookie Teddy Martinez being groomed as his utility infielder replacement; and Dave Marshall pinch-hitting; and Ken Singleton promoted from the minors when Kranepool went down; and Mike Jorgensen not breaking .200; and Art Shamsky who looked like he was gonna hit .300; and Ron Swoboda who I assumed hit more home runs than he did; and Cleon Jones who rated his own miniature comic book in a pack of baseball cards because he hit .340 the year before and .297 the year before that (which I learned from the comic book).

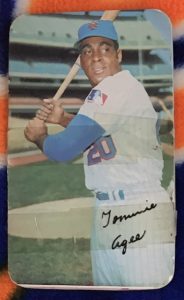

We had Tommie Agee. He didn’t have a comic book, but he had a Super baseball card, larger than those for the other Mets I got. Seems appropriate.

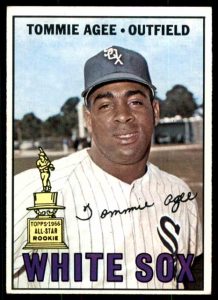

On the back was a cartoon. Not a full-blown comic book à la Cleon, but an illustration that illustrated the big news blowing out of the South Side of the Windy City: “Tommie was the A.L. Rookie of the Year.” A ballplayer wearing a Hawaiian shirt hugged a loving cup to drive home the point. An adjacent cartoon had a ballplayer in a blank uniform being “originally signed by the Indians”. I’ll leave it to you to imagine how the Indians were represented.

The Indians? Hey, if Tommie Agee was hot enough stuff to have won the Rookie of the Year, what was he doing on his second team? According to the MAJOR & MINOR LEAGUE BATTING RECORD Topps printed (I’m telling you, the back of the card is where the real action was), Tommie had three auditions with Cleveland from 1962 to 1964 and another with Chicago in 1965 before executing his award-winning campaign of 1966. The card was from 1967. In 1970, I learned Tommie had been a Met since 1968.

This guy got around more than I could comprehend. Apparently the White Sox weren’t as impressed by Agee’s promise as Topps had been. A year after Agee won his award, the Sox dealt him to the Mets. Our new manager, Gil Hodges, liked what he’d seen in the American League when he when he was running the Senators and pushed for his acquisition. (One of the players we traded to get him was Tommy Davis, whom I knew as a Met from the quickly outdated 1967 card collection I inherited from my sister.) Tommie’s first year as a Met was so massively disappointing it was constantly invoked for the rest of his Met days — not to be nasty, but to serve as prologue for what came next. He was a .217 hitter in 1968, not close to comic bookworthy. I picked up that he’d been hit in the head in Spring Training by Bob Gibson, making me dislike Bob Gibson very much. He went 0-for-10 in the Mets’ 24-inning loss to Houston on April 15. His average going into that marathon was .313. Coming out, it was .192. As late as September 7 it was .191. His RBI total in 132 games was 17. For everybody else, 1968 was The Year of the Pitcher. For Tommie Agee, it must have looked like The Year of Ten Pitchers at Once.

But by 1970, that was backstory that served to make 1969 only more Amazin’. By seven years old, I knew that’s how to spell the word. Tommie Agee was as much an influence on orthographers as anyone. His 1969 was legendary in an instant. He’s the Met who put ninth-place 1968 behind him with the most force. On April 10, 1969, in the Mets’ third game of the season, Agee hit two home runs, or forty percent of his 1968 total. The first of them nearly beat Apollo 11 to the moon by three months, landing fair on the left field side of Shea Stadium’s Upper Deck. Tommie was the first and last player to hit a home run to Shea’s highest tier. The ballpark stood 45 years. Only one player earned a commemorative marker way up yonder.

Agee’s Upper Deck blast waited nearly four decades for company that never arrived (photo by David G. Whitham).

In 1969, Tommie Agee hit 26 homers, second in Mets history to that point behind only Frank Thomas’s 34 in 1962. Five came leading off games, which will break up a shutout real fast. In August, he bopped one off Juan Marichal in the fourteenth inning to beat the Giants at Shea, 1-0. In September, he was dusted by Bill Hands to start a showdown series with the Cubs. He got up and got his revenge two innings later, stroking a two-run homer, reminding one and all this was no longer 1968. In the sixth, he slid incrementally past Randy Hundley’s tag to give the Mets the lead and, ultimately, the win, informing everybody that 1969 was like nothing else. The Mets would soon take first place and the division title.

Then came the postseason, first the inaugural NLCS versus the Braves (.357 average, a pair of homers) and then Game Three of the World Series, the one known forever more as The Tommie Agee Game. How many World Series games belong to a single player? Who would argue this wasn’t Agee’s? A leadoff home run. An impossible ice cream cone catch at the wall to cut off an Oriole rally. Another impossible catch diving across the grass to cut off another one. They said the first one, with him holding onto the ball despite its Good Humor impression, was more miraculous, but it was the second one I was determined to replicate diving across the grass of my backyard for much of the early ’70s.

“Batman at the plate, Robin in the field,” is how I read his Game Three performance summed up somewhere. Tommie Agee was a comic book hero, too.

That, and a world champion. His childhood chum Cleon Jones caught the last out of Game Five. They made their way safely from the enraptured throngs who had taken over the Shea Stadium sod into the clubhouse, joining a champagne-drenched celebration that is still going in the hearts and minds of Mets fans everywhere. Seaver draped an arm around Jones. Swoboda draped an arm around Agee. The city wrapped its arms around all of them.

Not quite as many home runs as in 1969 (24) but more stolen bases (31). The steals were a club record; one of them, on July 24 at Shea, was a tenth-inning steal of home to literally win a game against the Dodgers, the only time the Mets have stolen away with a walkoff victory. Tommie’s combination of power and speed was a revelation for a kid who understood the Mets were however good they were more because they pitched great and however lacking they were because they neither hit well or ran much. Agee’s aberrational skill set can be measured this way: his power-speed number, a calculation conceived by Bill James, was 27.1. The highest single-season PSN by a Met previously was 17.4 (Jones in 1968). Agee’s standard wouldn’t be topped until Darryl Strawberry posted a 27.5 in 1986. To this day, Agee’s 1970 PSN is the eleventh-best by any Met. And in the National League in 1970, Agee’s number was second only to Bobby Bonds. (He was also second to Bonds in strikeouts, but that only made him more human.)

Guy hits home runs. Guy steals bases. Guy continues to make great catches in center field and becomes the first Met to win a Gold Glove. Is it any wonder the guy becomes the talk of day camp in the summer of 1970? Tommie Agee is the name I remember taking up the most Met talk when I talked Mets with other seven-year-olds. Slugging, sprinting, snaring…that’ll get kids’ attention. He was fearsome in his talent, approachable in his demeanor. Me, I liked to talk about Tom Seaver, but I didn’t mind hearing about Tommie Agee.

It was a good Tom to be a kid.

That offseason, Tommie Agee was traded by the Cardinals to the Dodgers, a fact reinforced a dozen or so times in 1974 by the TRADED card I received quite often as I opened one Topps pack after another. But Agee never actually played for the Dodgers. L.A. released him in March and rudely went on to win the pennant without him. Nobody else signed him. He was 31 years old, not five years removed from The Tommie Agee Game, yet the game was over for him. In 1975, he told Sport magazine, “I knew I could still play and nobody contacted me. It hurt. It hurt my pride.” For a while, according to Sport, “he kept practicing his batting stance, his grip and his swing, in front of mirrors. And then, by the time he turned 32, he knew the dream was dead, and he stopped practicing.”

By the fall of 1975, Cleon Jones was no longer a Met, either, symmetry brutal in its poetry given that they’d been the Mets from Mobile together. Hell, there was a book by that title, delineating the journey of a pair of scholastic athletic stars from the Mobile County Training School who became a pair of world championship outfielders for the New York Mets. Though the Alabama city had been slow to embrace the Amazin’ nature of having two of its native sons shine in the same World Series, Tommie and Cleon did get some of their due after the Mets grounded the Orioles. A.S. “Doc” Young wrote in the aforementioned volume, “More than 5,000 people packed themselves into Mobile’s Bienville Square to participate in the city’s ‘Major League Day’” shortly after the Mets’ ticker-tape parade up Broadway. Though future Hall of Famers Hank Aaron, Willie McCovey, Billy Williams and Satchel Paige were feted, too, the guests of honor were “the Met men […] Agee received the greatest ovation when he said, ‘There’s no place like home.’”

Tommie and Cleon grew up in the same town at the same time, making their story that much more Amazin’.

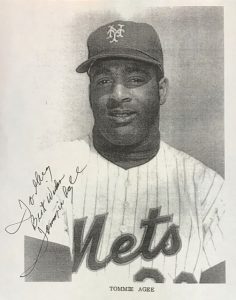

In retirement, every time there was any reason for Mets fans to be anywhere, it seemed Agee was there. It didn’t have to be an Old Timers Day or a 1969 milestone reunion or an episode of Everybody Loves Raymond. Agee made every appearance. I have a personally autographed picture of him secured for me by my brother-in-law who, trust me, doesn’t frequent sports gatherings, but Agee was on the scene at some trade show or another he visited. A blogging colleague has a personally autographed picture of Agee from a high school carnival in the late 1980s, never mind that to be in high school in the late 1980s was to have missed all of Tommie Agee’s Met tenure. I covered a press luncheon that reintroduced Rheingold to the New York market in the late 1990s. Agee spoke fondly of the old Met-sponsoring beer and his late manager Hodges and how he wished Gil could have been here today to enjoy one with us.

A co-worker of mine in 1996 handed me an envelope of photographs and told me to take a look, I’d get a kick out of it. I did. It was his son, who I was think was ten at the time. The kid had become friendly with another ten-year-old whose last name implied he was well-connected in a way my co-worker was sure I’d dig. The two kids, along with another friend of theirs, had gone to camp together that summer. The well-connected kid decided it would be fun to celebrate his birthday somewhere his connections made easily accessible to him: on the field at Shea Stadium during batting practice. Ergo, the pictures were of my co-worker’s son and his friends and a series of smiling 1996 Mets: them and Todd Hundley; them and Rey Ordoñez; them and Butch Huskey; them and Lance Johnson. Given the well-connected kid’s last name (began with a “W,” ended with an “n”), every Met happily paused his BP machinations to say cheese.

And then, amid all the 1996 Mets, there was a picture of the kids with a 1969 Met. A 1970 Met. It was Tommie Agee. The kids, who practically smiled their faces off in every picture, had no idea who he was but kept smiling. My co-worker had no idea why the old Met, out of baseball more than twenty years by now, was haunting Shea Stadium batting practice on a random summer evening with nothing more festive than another ballgame on the calendar.

I know why. Or I’ve decided I do. It’s because Tommie Agee was at home with us. Mobile had to think about making a big deal out of him? New York didn’t. At Shea in 1968, in the deepest doldrums of his slumping — he went 0-for-34 at one point — he lined a single up the middle, eliciting an enormous cheer. “It was not the cheer of sarcasm you hear so often in ballparks,” Dick Young wrote in the Daily News. “This was genuine elation from the fans, a show of appreciation that he had hung in there to snap his oppressive run of 34 consecutive outs.”

Tommie Agee elated us a lot in 1969 and 1970 and we never forgot. Unlike the Indians, the White Sox, the Astros, the Cardinals and some shortsighted stuffed shirts in the Mets executive suite, we the Mets fans never traded him. Unlike the Dodgers, we never released him. We appreciated him. Kids of 1969. Kids of 1996. We all got it when it came to Tommie Agee. We all appreciated him and he appreciated us all right back, right to the day he died too soon, in Manhattan in 2001 from a heart attack at the age of 58. I don’t believe there’s been a significant public congregation of 1969 Mets since — starting with Tommie’s posthumous induction into the Mets Hall of Fame in 2002 — when he wasn’t spoken of by teammates fondly, represented by members of his family lovingly, and cheered by the rest of us, his extended Mets fan family, heartily.

That’s my understanding of why Tommie Agee was always around and I’m sticking to it.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1964: Rod Kanehl

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1969: Donn Clendenon

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

2000: Melvin Mora

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2005: Pedro Martinez

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

OK, World Series perfect games and no-hitters are amazing accomplishments, but among position players, Agee’s Game 3 could be the greatest single game performance in Series history, as he did it with the bat and the glove. Saved 5 runs by himself and wrapped up the 1970 Gold Glove that day.

Heck, I’d put up with that W-n kid right now (my age even!) if it got me pictures with Polar Bear, Squirrel, and Ces, if they can get him off the stretcher.

Yes, that is what I took from the article :-P

Tommie Agee, the symbol of 1969.

Never really saw him play live, as I became a daily fan in 1973. But 1969 runs through my veins as big as any year in Met history.

Actually, I did see him live, though, as he hit a homer in the first game I ever attended at Shea, in 1971. And when I got home, my grandmother said, “who hit the home run, A-Gee?” Mispronouncing the G in his name. I thought that was very funny then, and still do now. And whenever I hear his name, it always reminds me of that incident.

I remember his crummy 1973 Topps card, with Houston, one of those terrible horizontal action shots, and then his 1974 Topps TRADED card with the Dodgers.

A short time before he died, I went to an autograph signing with him and Staub, who did not like to sign. I didn’t buy whatever it was, and did not get an autograph, but I just went to take a look at them. Or maybe they were just selling their autographs, I don’t know.

Finally, when I first saw the big Agee 20 circle on TV, in the upper deck, I thought it was made of some kind of material. Maybe I am the only one. I was very surprised when I actually went up there, put my hand on it, and found it was painted on the smooth concrete.

Good Times.

I trekked up to Section 48 on Closing Day 1997 to take the same head-on picture everybody but David G. Whitham took and was indeed surprised that the 20 was painted.

Guess it would have been stolen had it been made of material, so a good move.

1969 game 3 was the single greatest game played by any Met…Agee for those of us who experienced that will never be forgotten..

[…] FOR ALL SEASONS 1962: Richie Ashburn 1964: Rod Kanehl 1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice 1969: Donn Clendenon 1970: Tommie Agee 1972: Gary Gentry 1973: Willie Mays 1977: Lenny Randle 1978: Craig Swan 1981: Mookie […]

[…] been a break in the drought, but I can get by on the Mets Classics and the One-on-Ones and writing about Tommie Agee and reading about Todd Pratt. I’d understand if that was all the baseball we were gonna get in […]