Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

Come on along

Come on along

Let me take you by the hand

Up to the man

Up to the man

Who’s the leader of the band

—Irving Berlin (ideally interpreted by Lou Grant)

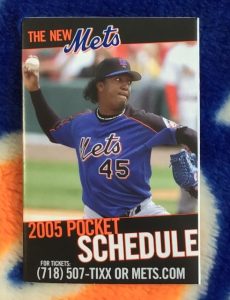

The first player this blog named its Most Valuable Met for a season just completed was Pedro Martinez. His prize in 2005? One whole paragraph devoted to his sparkling campaign. If, in fact, he clipped and saved it, there’s no doubt in my mind that it fits snugly to this day among the winner’s three Cy Young Awards and Hall of Fame plaque.

Still, just one paragraph for such a historymaking event? By way of explanation if not alibi, the Faith and Fear in Flushing Awards Committee (FAFIFAC) had convened on the fly that October and hadn’t really thought through its presentation protocols. Nor did FAFIFAC realize it was commencing a tradition that would endure for the next fifteen seasons — sixteen, if a next season happens to happen. Thus, whereas future winners would enjoy entire essays devoted to their deeds, Pedro Martinez received one paragraph…in which he was compared to a novelty beverage.

Drawing such a parallel wasn’t intended as an insult. Given where I was coming from in 2005, it was a genuine honor.

From 1989 to 2004, you see, beverage was a dialect I spoke fluently and frequently. Today, my drinktalk is a little, shall we say, watered down, but fifteen years ago, it remained on the tip of my tongue from the previous fifteen years, when the beverage world and the beverage spectrum were my daily concerns. As a business magazine reporter and editor, I wrote about beverages for those fifteen years like I would write about baseball for the next fifteen years as a blogger and author. It’s little wonder that the two B’s that have absorbed the bulk of my vocational attention for three-plus decades would overlap at the transition from one B to the next.

(And who knows — based on recent reports, knowing a little something about beverages might have more than a little to do with knowing something about one baseball team in particular pretty soon.)

In considering the Most Valuable Met candidates for 2005, I processed reliever Roberto Hernandez as Old Forester Bourbon (“dates back to the 1870s, but can still deliver when called on”); shortstop Jose Reyes as SoBe Adrenaline Rush (“works fast”); third baseman David Wright as Strawberry Quik (“Wholesome. Pure. Smooth.”); and left fielder Cliff Floyd as Miller Lite (“a new and improved formula that doesn’t leave you feeling weighed down by unmet expectations”). They all had good and valuable 2005s for the Mets, but there was only one Met who was Most Valuable in Faith and Fear’s first year, and he, Pedro Martinez, was Jolt Cola.

Twice the sugar. All the caffeine. Not only can’t you close your eyes, you won’t want to. The hum in your head is unmistakable. Your senses are tingling. Gotta have another blast of that stuff.

That, not incidentally, was Jolt Cola’s actual sales pitch: a surfeit of sugar and a cacophony of caffeine, presumably plenty enough for anybody cramming for finals or driving through the night. Otherwise, I can’t imagine it was an ideal dose. Nevertheless, Jolt created a tempting proposition. How could you not want to try it at least once? Jolt Cola was a cultural phenomenon when it launched in 1985, four years before I started getting my hands professionally wet. By the time I came along, it was pretty much yesterday’s news, though it would generate a little press here and there during my prime beverage years. Less significant than how much Jolt Cola sold was the idea it spawned. One can certainly draw a line from a pepped-up carbonated soft drink to the energy drink wave that was charging into view in the late ’90s, right around the period the future first FAFIF MVM was taking his world by storm. You bring a name like Jolt on the market, you oughta have an impact.

Similarly, when you bring a pitcher like Pedro Martinez into a situation thirsting for his brand of presence, you’re gonna feel a jolt. And when you reflect on a pitcher like Pedro Martinez and how valuable he was in the year he became omnipresent in your situation, you’re gonna need a whole lot more than a single paragraph.

So open the beverage of your choice and sit back. Or lean forward to edge of your seat, like you might have when this man chose to join our ranks.

Pedro Martinez was exactly one person, exactly one player. Yet it could be argued that on the greater baseball map, in the years directly preceding his arrival on the team he essentially took over in 2005, the extraordinarily famous righthander was a bigger deal by himself than the New York Mets were as a multi-person, multi-player unit. From 2002 to 2004, the Mets unintentionally disintegrated as a competitive entity, passively pulverizing the goodwill they’d carefully constructed in building themselves into a perennial contender between 1997 and 2001. While the Mets rose and fell in New York, Martinez reigned atop his realm mostly without pause. He was too good to be ignored in Montreal, then too great to be paid in Montreal. In 1998, he was off to Boston. The Red Sox were in for the ride of the franchise’s life, culminating in the capture of the biggest flag there is in 2004.

When the satiated Sox finally achieved with Pedro what they could never quite manage in the eighty years prior to the start of his starry New England tenure, they, like the eventually defunct ’Spos, saw no compelling reason to keep paying him what he wanted for as long as he wanted. Pedro Martinez, as celebrated a pitcher as there was in North America at the close of one century and the dawn of another, became a free agent.

What had been perhaps the most moribund large-market organization in baseball pursued him and signed him. That’s the same organization that an offseason earlier had the clearest shot imaginable at another ex-Expo advancing along a Cooperstown-bound track and couldn’t lowball him enough. Somehow, the same New York Mets who couldn’t be bothered to ante up for a readily available Vladimir Guerrero in January of 2004 pushed a blockbuster offer to the middle of the table in December of 2004 and asked Pedro Martinez to please take it to the bank.

Which he did. Suddenly, for the sum of $53 million spread our over four years — when committing more than three years to a starting pitcher past his thirty-third birthday caused heads to shake industrywide — Pedro Martinez became a Met. Technically, he was the second Pedro Martinez to become a Met. The first was Pedro A. Martinez, a lefty reliever who pitched in five games for the 1996 Mets. Pedro A. Martinez was best known, even in 1996, for not being Pedro J. Martinez. This was three years after we got Mike Maddux, who was best known, even in 1993, for not being his brother Greg. We tended to gravitate to the guy who was best known for not being somebody else.

Not this time. This time we got the Pedro Martinez. For a while, nothing would ever be the same.

Nevertheless, I suspect people forget just how big Pedro Martinez was as a New York Met, especially in 2005, but really pretty much to the conclusion of his contract in 2008. He loomed as large as an individual Met possibly could over the entire operation from the instant he got here. Pedro was where we looked for answers, for progress, for hope. In that first year, Pedro was where we got it.

I don’t know if “people forget” that it took a radical regime change in the front office (Jim Duquette to Omar Minaya) to positively alter the Mets’ roster-stocking methodology. I don’t know if “people forget” that there was a discernible span of time when the Wilpons weren’t called the Coupons. I don’t know if “people forget” that an enormous investment in a 33-year-old pitcher translated on the field, at least for a spell, as a bargain for the ages.

I do know fifteen years tend to fly by in perception yet actually measure out to fifteen years, which can be reasonably defined as a long time. I do know all those elements sound as if they occurred in an eon unrecognizable to how we’ve come to view the Mets over the past decade or so. But this was how we rolled. Let’s get a GM who’ll take chances. Let’s let the checkbook out of the desk drawer. Let’s be thrilled that we did and not ask too many questions about where the funds are coming from. It wasn’t a foolproof formula for long-term growth, but damn it was effective and fun for a couple of years, just as Pedro Martinez was effective and fun for those same couple of years.

Especially in 2005. Pedro wasn’t the sole marquee addition for the season ahead — the Mets stunned the sport by swooping in and carrying off five-tool dynamo Carlos Beltran that January (seven years, $119 million) — but Martinez represented an injection of charisma on top of capability that the organization practically ached for.

In beverage terms, they couldn’t have been flatter coming out of 2004. In further beverage terms, Pedro popped from the bottle in 2005 with such force that you had to be sure to uncork him away from your face. We hadn’t had that spirit here since 1999.

In Port St. Lucie, everything Pedro Martinez said or did was news of the most urgent order. Didja hear? Pedro dressed up in an orange suit! Pedro paraded through the clubhouse in nothing but a smile! Pedro messed around with a mannequin! Pedro absconded with the grounds crew’s tractor! Pedro said this! Pedro did that! Pedro! Pedro! Pedro!

And that was just Spring Training. The Marcia Brady of the Mets rotation would generate even more attention once the regular season started.

CINCINNATI, April 4 — The new season. The new ace. The new avatar of what it means to be Mets. In the bottom of the first inning maybe not so much, as Pedro Martinez surrenders two singles followed by a three-run homer to Adam Dunn. But then — nothing. A couple of walks, but that was it. Pedro retired every Red in sight, striking out most of them, twelve over six innings. The new manager, Willie Randolph, removed him after the Mets took a 6-3 lead in the top of the seventh, leaving the club’s Opening Day fate to Manny Aybar, Dae-Sung Koo and Braden Looper. How do you suppose that worked out? The Mets lost, 7-6, but save for Joe Randa’s walkoff homer, the talk of the Opener was Pedro. Loser Looper: “Pedro pitched a great game. He struck out the world.” Villain Randa: “Pedro was on top of his game. He was carving through us. He was unhittable. Once he was out of the game, there was a big sigh of relief on the bench.” Hapless Randolph: “He gets a certain look on his face: That’s it. I’m gong to shut you down and that’s it.”

ATLANTA, April 10 — The Mets were more Looper than Pedro as they continued their first road trip of 2005. Two more losses at Great American Ball Park. Another two at Turner Field. The Mets were 0-5 for the first time since 1964, a year when the Mets hadn’t invested in Pedro Martinez let alone Carlos Beltran. In their finale against the Braves, those investments paid dividends. Sure, it was still Turner Field. Sure, John Smoltz was still trouble. But Pedro picked up where he left off in Cincinnati and then went further: the full nine innings; only two hits; only one walk; only one run — and another nine strikeouts. Smoltz was also Hall of Fameworthy (15 Ks as he reacclimated to starting after four years as Atlanta’s closer), but in the eighth, with the Mets down 1-0, Beltran belted the three-run homer that guaranteed the Mets wouldn’t go 0-for-’05. After the 6-1 victory, Randolph savored a victory cigar and the savior of his season: “Pedro said, ‘I’m not coming out.’ That’s just the kind of warrior he is.”

FLUSHING, April 16 — Now the Mets couldn’t lose. After getting to 1-5, they swept the Astros, then rode Aaron Heilman’s one-hitter (!) over the Marlins to .500. On Saturday afternoon at Shea, with a Kids Opening Day crowd of more than 55,000 crammed in, all screamed for Pedro. He was officially a happening every time he showed his face. We loved him for beating the Braves. We loved him for batting down crazy WFAN talk that he skip the Home Opener so he could fly back to Boston to accept his World Series ring. We loved that during that Opener, when a batter’s eye ad with his picture got stuck between innings and delayed the game, he emerged from the dugout and did a little dance, which made a little love between us and him. Mostly we loved the pitching he did for kids of all ages. Versus Florida and their erstwhile-Met starter Al Leiter, Pedro threw seven innings, allowed three hits, one walk and two runs while striking out nine. Leiter made like Smoltz in the role of obstinate opposition, but karma was with the new Met over the old Met. Both starters were out by the time Ramon Castro drove home Victor Diaz with the walkoff run. “He pitched well,” Marlins first baseman Carlos Delgado conceded after his team lost, 4-3. “He was throwing harder than what he had last year.” Pedro was happy his Mets were playing “loose and with more confidence. If I am to lead, I am going to lead by example. That’s what they are going to see.”

And see, we did. In his fourth start, on April 21 in Miami, Pedro shut down the Marlins again, this time in a Met rout. Over the radio, Gary Cohen scored it a triumph for reality over reputation:

“Pedro’s been described as a diva. What he is is a maestro.”

The Maestro wouldn’t conduct a tour de force in every start — and the Mets couldn’t quite break free of the gravitational pull of .500 — but every Pedro Martinez start of 2005, home or away, was an event to be anticipated. You wanted to go. You had to tune in. You depended on Pedro to cultivate winning ways and rebuff losing inclinations. Win or lose, there was always a carnival going on around him. Step right up and don’t be shy. Because you will not believe your eyes.

Shea’s sprinklers went off one night while he pitched; he danced some more.

Twice he flirted hard with no-hitters; one was broken up in the seventh, the other in the eighth.

Twice he bore the brunt of old AL East jibber-jabber when his former archrivals from the Bronx appeared on our schedule; the Mets split those Subway Series games, though Pedro pitched well enough be the Yankees’ daddy in each of them.

Carlos Beltran, who otherwise slumped most of his first nervous season in New York, basically homered only when Pedro pitched; nine of his first ten Met dingers rang in the service of Pedro starts.

The high-profile presence of Martinez and Beltran, among other Latin players brought on board by a Latin GM, spurred the unofficial nickname Los Mets, which was interpreted in different quarters to mean different things, meaning it became another story with Pedro at its heart.

Mike Piazza, who didn’t exactly mesh with proto-Pedro when they were together as Dodger youngsters (plus Pedro plunked him at Fenway during Mike’s first weeks as a Met), navigated a public truce with his second-time batterymate and immediate successor as the franchise’s marquee star…though Pedro worked quite a bit with backup catcher Ramon Castro…and that became yet another Pedro story in the course of what was, above all else in Metsopotamia, a Pedro season.

On a personal note, on the May night our beloved cat Bernie died, Pedro took the mound and mowed down the Marlins. And on the September night we adopted the kitten who instantly became our beloved cat Avery, Pedro took the mound and mowed down the Braves. Each was a ten-strikeout masterpiece. Each was, in the view of the Prince household, the cat’s pajamas.

All of this while Pedro was inarguably in his 34th summer, more than half of them having been devoted to pitching competitively.

All of this while the bigger-than-life figure persevered in a slight-of-figure frame.

All of this as his MLB odometer clicked past 2,500 regular-season innings pitched, not to mention all those pressure-packed postseason outings with Boston.

All of this from a self-described “old goat”.

Physically, Pedro Martinez wasn’t as indestructible as a Mets fan might have preferred. He skipped the All-Star Game to which he was rightly named in deference to taking much-needed rest. In August, he didn’t fight Randolph’s inclination to take him out with an 8-0 lead over Washington after six innings. He’d been dealing with discomfort between his shoulder blades, so every little bit of preservation was a blessing for an ace trying to lead his acolytes toward a Wild Card bid.

The Mets’ reliably unreliable bullpen blew the lead, but the offense came back to win in extras, 9-8. It might have made sense to sit down an aching veteran with a seemingly insurmountable edge, but it was also a reminder that the 2005 Mets were mostly only capable of going where Pedro Martinez led them.

Many Mets made 2006 better than 2005. Nobody made the year before 2006 better than Pedro Martinez. His 2005 was not only the start of something bigger, it was a legitimate standout in Met annals beyond the every-fifth-day effervescence he brought to Shea along with the commensurate rise in the ballclub’s Q rating. Pedro went 15-8, recording an ERA of 2.82, striking out 208 batters in 217 innings. The innings total was as high as Pedro had posted in a regular season since he was a lad of 27 in 1998. Batters hit all of .216 against him while Castro caught, .191 against him with Piazza behind the plate (in his 2015 memoir written with Michael Silverman, Pedro admitted he preferred throwing to Castro). His four complete games hadn’t been exceeded by a Met since Dwight Gooden’s five in 1993 and wouldn’t be topped until R.A. Dickey’s five in 2012; no Met has had as many as four since Dickey.

Interpreted by the advanced metrics that were just then taking hold in the greater baseball fan consciousness, Martinez’s ’05 was even more special. His wins above replacement, according to Baseball-Reference, measured 7.0, ninth-best among all starting pitching seasons in Mets history. Metwise, Pedro’s bWAR has been surpassed in succeeding seasons only by Johan Santana in 2008 and Jacob deGrom these past two Cy Young campaigns. When he achieved it, the 7.0 was the best by a Mets pitcher since Dwight Gooden’s transcendent 12.2 twenty years before.

Whereas Doc was in the advanced stage of his prodigy phase in 1985, Pedro was as veteran as could be at his Met peak. He’d first been signed out of the Dominican Republic in 1988 and made his major league debut in 1992. While Piazza was winning the National League Rookie of the Year Award in ’93, Martinez was getting his reps in as a Dodger reliever. He began forging an identity for himself, not content to coast on being simply Ramon Martinez’s kid brother. Before L.A.’s front office could fully realize what the younger Martinez could do, they traded him to Montreal for Delino DeShields. Pedro refined his game in Canada, winning his first Cy Young in 1997. In Boston, he elevated the town and the team not to mention his own profile. Two more Cy Youngs came while he was a Red Sock, the second of them, in 2000, on the wings of a microscopic 1.74 ERA carved at the height of the (ahem) enhanced strength & training era in baseball. As a youngster, he threw incredibly hard. Time might have compelled him to adjust his repertoire (as it did Tom Seaver), but he knew how to make his pitches work for him.

“The heart and mind of Pedro is what has him in the Hall of Fame today,” Fred Claire, the man who traded Pedro from Los Angles, told Rob Neyer on Neyer’s SABR podcast in 2020. We saw that at Shea in 2005 and, to a certain extent, during the three years that followed. The thrill in watching a Gooden 1985 performance didn’t require much explanation; he was a poised youngster in the full bloom of talent and the results flowed. For me, the joy of Pedro as a Met (and any accomplished veteran who could still negotiate a tough inning) was watching him understand what he had to do and then figure how to do it. As he aged, batters occasionally got the best of Martinez, but I never sensed they were better at what they did than he was at what he did. It was one thing to pore over his statistics while he was in residence at Fenway or check in on him under the October spotlight. Focusing on him for thirty-one starts in his thirteenth full season helped me truly comprehend what all the Pedro Martinez fuss had been and was still about.

Another reason I find myself invoking Gooden vis-à-vis Martinez is because, stats aside, Pedro’s 2005 registered as the most vibrant pitching season at Shea Stadium since 1985. People showed up for Doc. People showed up for Pedro. We showed up for Cone and Viola and Saberhagen and so on, but showing up for these two guys was different. For fans of a certain generation, the Pedro sensation provided a flashback. For fans of the next generation…well, that’s of specific interest to me and what I’m doing at this moment. Just as I inextricably associate two of Pedro’s excellent starts with the going and coming of two of my beautiful cats, I can’t separate what Pedro did in 2005 with what I started doing and what a lot of us started doing that year.

We started blogging in 2005. Faith and Fear in Flushing commenced during Spring Training. In the weeks and months ahead, if memory serves, so did sabermetrically savvy Amazin’ Avenue, news-driven Metsmerized Online, historically curious Mets Walk-Offs, relentlessly friendly Mets Guy in Michigan, refreshingly clearheaded Mike’s Mets, the incomparable Metstradamus and a slew of others not necessarily still with us. The presence of Pedro Martinez didn’t directly draw Jason and me into this passion of a pastime, but boy did he help give us something to blog about. I think that feeling was widespread within the nascent Metsosphere. Those of us who’ve stayed on the beat from 2005 onward probably owe a tip of the cap (or a can of Jolt) to ol’ No. 45 and what he did once he took the ball out of that blue glove of his and fired to Piazza or Castro. Later we’d have as our charismatic aces/subjects of fascination the likes of Johan, R.A., Harvey, Thor and the magnificent Mr. deGrom, all of them the kinds of pitchers that made you grateful you had a platform from which to expound regarding their feats and their craft. But it was Pedro who initially made the Mets blogworthy, starting that first afternoon in Cincinnati.

And once you get started, oh, it’s hard to stop.

Time marched on, and Pedro moved in lockstep with it, giving it his all for the old goat in each of us eligible by then for OG status. He’d be giving it in 2006, 2007 and 2008, too, except he had less to give, injuries inevitably diminishing his availability and sapping his skills. Martinez still knew how to get out of innings, but he wasn’t able to start nearly as many of them. The leader of the band was tired and his arm was growing old. Muscle memory pushed him part of the way; mental acuity took care of the rest. The numbers weren’t impressive as his contract expired, but watching Pedro Martinez was special right up to the end.

Whaddaya know? Sometimes people do forget.

Nevertheless, that blog-commenting young person’s intuition from 2005 was definitely in the ballpark: the excitement stirred by Pedro was like the excitement around Doc. Never mind that Doc was homegrown and therefore automatically “ours,” while Pedro was a free agent acquisition who was bound to be remembered as a Red Sock primarily and an Expo north of the border. Pedro bridged the geographic gap to our hearts with his pitching and his personality. Sure, he wanted to get paid, but he chose to be among us and strove to help us be the best Mets we could be. When it came to baseball, Pedro Martinez was a missionary rather than a mercenary.

When he got to Cooperstown in 2015, even though his plaque portrayed him in a Red Sox cap — and even though it was his Boston exploits that dominated the chatter among the baseball commentariat — he remembered us, letting us know his “wild” side was essentially the “Mets fan” in him. “That’s how we are,” he told his induction audience in the first-person plural. “So Queens, I love you, too!”

Pedro, from the edge of this particular seat somewhere a little east of Queens, the feeling remains mutual.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1964: Rod Kanehl

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1969: Donn Clendenon

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

2000: Melvin Mora

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

“Shea’s sprinklers went off one night while he pitched; he danced some more.”

This is always what I remember when I think about Pedro.

His catcher that night wasn’t nearly so vivacious in those wet circumstances. I loved rooting for both of them, but revisiting this Met period reminded me that Pedro and Piazza were not exactly burgers & fries.

You gotta love Piazza, but he does not possess a happy-go-lucky soul. His post-retirment autobiography was a Festivus worthy rant!

Nothing against Pedro, but I rarely think of him as a Met. He gave us a good postseasonless year, and was never himself thereafter. His being here was fun (I remember his somewhat perplexing “It’s Lima time!” when the Mets added the completely unpromising Jose Lima for 15 minutes), the memory of him wearing blue and orange doesn’t make me cringe like G|@^¡ne, but in retrospect, I’ve just never felt like it added up to much.

One of the additional things I adored about Pedro is how he looked out for his lesser-light teammates. Like speaking up for Victor Zambrano when the generally shunned lefty ran off the mound in pain. Like convincing Randolph to keep Mike Jacobs when they were ready to send him down. And, yes, his affinity for the late Jose Lima.

Lima was indeed terrible in his few Met appearances, but he, too, struck me as a great guy to have around (perhaps as a coach by then). Next time you see an extended cut of Wright beating Rivera in 2006, watch who leads the celebration from the first base dugout. Lima Time may have been in its 14th minute, but he seemed to relish every Met second.

This is a fantastic post Greg, thank you.

I loved watching Pedro in orange and blue, especially @ Shea.

The first time my (then 5 year old) son and I went to a game without Mom making sure I could deal with a kid at a game by myself was this one:

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/NYN/NYN200507230.shtml

Were we PUMPED when we sat down for the 3pm start?

Yes

Did Pedro pitch great?

No

Did the Mets win?

Yes

Was Pedro awesome?

Yes

His Hall of Fame shout out to Queens still rings in my ears.

Viva Pedro!

Gracias Joe.

I hear the Pedro/Doc comparison. In another way, Pedro was a forerunner to Bartolo Colon’s Met career. Pedro was obviously the way superior pitcher, but Bartolo had the same oversized personality and sense of humor.

Different roles, different trajectories, different vibes, but at their respective Met peaks, similar levels of popularity.

Well, Greg, if you felt at all guilty of shortchanging Pedro in his 2005 Most Valuable Met writeup, you most certainly made up for it here, in quantity and especially in quality! This one is filled with gems, as always.

I was at one of those near no-hitters: August 14, 2005, Dodger Stadium. Pedro took a 1-0 lead into the bottom of the 8th, but Antonio Perez (who?) tripled off the center-field wall (Gerald Williams could have caught it) and Jayson Werth (argh!) homered. Can’t fault Willie for leaving in Pedro, even for the Werth p.a.; not sure what the bullpen rest situation was at that point in the season, and Pedro still had a 1-0 lead. In the top of the 9th, Victor Diaz failed with Marlon Anderson on third and one out (Anderson had lined a double to deep left-center and stolen third). Victor hit a soft grounder on a checked swing to a drawn-in 2Bman, who threw out Anderson at the plate. I was pissed at Victor, yelling “Take a full swing!” after the play. All we needed was a sac. fly, and Pedro would have had one fewer loss. Maybe it’s the curse of Miguel Cairo. Mets: one run on 10 hits, including four doubles. Looking back at the record, that lineup on the Dodgers was unimpressive. That was an important game we should have won.

The following year, I was back there for another Pedro start. The Mets hit early and scored a few (but I missed it, stuck in traffic on Sunset Blvd.). Pedro didn’t have much and got shelled. He’d thrown out his arm by that point. Mets didn’t win that game, either.

Thanks for both the kind words and on-the-scene report, Michael. Pedro’s second no-hit bid is, I’m pretty certain, the last complete game loss by a Mets pitcher (not counting rain-shortened games). With Brad Penny going all the way for the Dodgers, it’s the second-most recent dual complete game the Mets have been in, followed only by Dickey vs Hamels in 2010, unless I’ve missed one, Hamels had the only Phillie hit that night as the Mets won. Mike Hessman had a home run turned into an unlikely for him triple by replay review.

You are certainly welcome, Greg. I don’t recall if I went to the near no-hitter because Pedro was starting or just because it was the Mets, but I was let down in the 8th. At that point, we hadn’t had the Johan game of 06/01/12, so I was thinking ‘this might be our best shot at a no-hitter, with complete games going by the wayside’. Great research on the complete-game losses; I’m a little surprised that it hasn’t happened to deGrom or Syndergaard or someone else of recent years. Without me checking, was the R.A. game part of the three consecutive shutouts vs. Philly? I remember that series fondly: 8-0, 5-0, and 3-0.

The dual CG was in August 2010, three months after the Goose Egg Sweep, as Gary Cohen called it. So the Mets shut out the Phillies four times and finished a continent behind them.

I thought our first no-hitter was going to be Randy Tate in 1975. Darn Jim Lytle…

Same. Definitely in the first tier of heartbreak on a scale of One to Qualls. In fact, I’d give it a Tate.

[…] Unforgettable, That’s What You Are » […]