The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 26 April 2022 12:35 am Pitchers’ duels are one of the earliest tests of budding baseball fandom — dull to the casual observer who wants action and doesn’t get why those around him are oohing and aahing over hitters swinging and missing or just looking flustered at balls zipping from hurlers’ hands to places they weren’t expected to wind up. It takes a certain amount of time watching the game to understand that there’s a whole lot of something underpinning what looks like nothing — a labor demanding incredible physical skill as well as tactical cunning and laser focus.

And when both starting pitchers are operating at that level, it’s something special. One of my fondest baseball memories is standing in a bar on a beautiful May night in Rockaway Beach watching Pedro Martinez and Roger Clemens battle it out at Yankee Stadium — a pitchers’ duel so riveting that diehards and casual fans alike instinctively arranged themselves into perfect rows, as if the bar had become baseball church and we’d assigned ourselves to invisible pews.

But pitchers’ duels are premised on the promise that one of the combatants will yield, cruelly but inevitably. Someone will tire or make a lone inexplicable mistake or be done in by bad luck — two pitchers deserve to win, but only one can. That’s the classic template, but sometimes the game doesn’t cooperate.

Sometimes it’s a draw, which means the duel ends without a resolution, giving way to the anticlimax of middle relievers alternating to see who’ll draw the black spot. Which can be entertaining baseball but is lousy storytelling: Picture a showdown on a dusty western street where the guy in the white hat and the guy in the black hat stagger away, wounded but alive, allowing a parade of drunks to take turns blasting away at nothing in particular. Or a battle of the bands where the headliners never return for encores, leaving the opening acts to come on and say they guess they’ll play a few songs you’ve never heard of.

And sometimes the script gets torn up into little pieces and you get insanity.

Max Scherzer — he of the chewing-up-glass intensity, terminal hat head and relentless dugout pacing — simply annihilated the Cardinals’ tough lineup, trotting up his ungodly array of pitches and looking like he could do whatever he wanted with them. His counterpart, Miles Mikolas, might not have been as flashy but was every bit as good, befuddling a tough Mets lineup. (I felt vaguely bad for knowing almost nothing about Mikolas, and a little better when I realized his track record against us consists of a single start two years ago — he won — and a lone inning long before that as a baby Padre.)

Both Mikolas and Scherzer were done after seven, meaning it was time for reliever roulette. The Cards’ Genesis Cabrera — whose name I now know isn’t pronounced like the start of something — passed his test while Trevor May did not, giving up a leadoff single to perpetual nemesis Yadier Molina and another to lavishly locked Harrison Bader. May is the Mets’ most Jekyll-and-Hyde reliever and this was one of his unfortunate transformations — the Mets scratched and clawed through various defensive and pitching strategies but to no avail, as May left an offspeed pitch in the middle of the plate for Tyler O’Neill to whack into the outfield for a two-run single.

That looked fatal, particularly after Robinson Cano flied out as the tying run in the ninth — perhaps when the team doctors get done poring over Jacob deGrom‘s MRI they can evaluate Cano and what sure looks to me like a case of utensil-spinal impingement.

Mark Canha was the Mets’ final chance against Giovanny Gallegos, whose pace on the mound makes one want to give Rob Manfred permission to institute the pitch clock a year early. Canha has been an intriguing player so far, an Olerud-like professional hitter with a calm demeanor and a sneakily ironic sensibility. (This bit of MVP deadpan is from an interview as a A’s rookie.) He fell behind against two Gallegos sliders, refused to bite at three out of the strike zone, and then slapped Gallegos’s seventh pitch up the third-base line. That looked like a solid AB with an unfortunate outcome — it was a tough play for many third basemen, but not typically for Nolan Arenado.

Arenado, though, couldn’t get the handle. He took extra steps searching for the grip, ran out of time and uncorked a high throw to first, making the score 2-1 and leaving the Mets still alive. Travis Jankowski took over for Canha at first and took off when Jeff McNeil laced a pitch down the right-field line. Jankowski flew around second and steamed into the neighborhood of third, the precinct of the so far famously aggressive Joey Cora. Cora held him — which made me gasp in dismay, though the replay showed that to have been a good decision. And so the game would come down to Dom Smith, who’s been saying all the right things or rather not saying any of the wrong things despite finding playing time hard to come by.

Smith smacked a Gallegos fastball up the right-field line, where it was smothered behind the bag by one of the Cardinals’ many annoying Gold Glovers, in this case Paul Goldschmidt. But Gallegos had been caught spectating. Dom hustled to first as Gallegos tried to close ground and then dove in safely — the one time in approximately 5,000 where diving into first is indeed the right play. Gallegos belatedly looked home, just in time to see McNeil diving across the plate in Jankowski’s wake as the go-ahead run.

That was it for Gallegos but not for the Mets; SNY wasn’t quite back from break when Brandon Nimmo slammed T.J. McFarland‘s first offering into the right-field stands for a two-run homer. The Mets led 5-2, and while the much-ballyhooed best fans in baseball weren’t booing, it was only because they were as shocked as everyone else. Edwin Diaz navigated the bottom of the ninth with only minor fuss and they’d won somehow — I mean, just look at this record scratch of a win-probability chart.

If the Mets make something of this season, we’ll tell Just So stories about this game and throw around words like fire and grit and heart. And even if they don’t, that was the kind of game that keeps you in your seat for dozens and dozens of grindingly dull non-comebacks, waiting for the karmic wheel to come back to that giddy, gleeful space that makes all the misfires worthwhile.

by Jason Fry on 24 April 2022 10:05 pm We’ve been where the Diamondbacks are now — a team with hope for the future that’s trying to remind itself that future can’t be hurried. The guys who could be a part of it need to get there at their own pace, with all the growing pains implied; the caretaker players are important as teachers and public faces but will be gone by the time that day arrives. If it arrives, baseball being unpredictable in many ways but cruelly reliable in its ability to spill ink on blueprints.

We’ve been there, but mercy isn’t part of the equation. And so the Mets did what we hoped they would, not getting in Arizona’s way as the D-Backs made a whole bunch of mistakes that essentially handed the visitors a 6-2 win. So far the Mets have won five season series and lost none, and while I don’t claim to be a statistical savant, I suspect if they do that all year we’ll all wind up happy.

They won’t, of course — I’ll step on the moment by reminding us that the 2018 Mets also won their first five series en route to winning a grand total of 77 games. If you go back into the Faith and Fear archives, you’ll find all sorts of giddy posts about 11-1 starts, 17-9 Aprils and Mickey Callaway‘s Midas touch.

(In other words, don’t go back into the archives.)

Still. 12-5 will work nicely, with the record backed up by the eye test. Tylor Megill would have been forgiven if he’d spent the winter resting up after a season that took his arm places it had never been; instead, he reinvented his delivery and his approach to pitching, with great results so far. (Megill still got beat on his second-best pitch for his final act of the day, but hey, Rome and building schedules etc.) Francisco Lindor got two hits and nobody particularly noticed, which is a sign of how different his year has been so far. J.D. Davis whacked a home run into the right-field stands, which is an excellent way for making himself a bigger part of the plan. There was nifty fielding by the tragically Samson’ed Luis Guillorme, an impromptu game of leap frog by Starling Marte, and no Edwin Diaz to make my stomach turn gymnast. Oh, and the Mets pulled off the routine 1-2-3 put-out, thanks to a terrific play by James McCann on a ball that caromed off Seth Lugo‘s foot and somehow shot straight back at his catcher.

With so much going right, seeing Buck Showalter‘s Resting Pissed Face in the dugout only added to the entertainment. Buck will never be able to match Dallas Green for Managerial Facial Expressions You Don’t Want to See — Dallas witnessed a lot of baseball slapstick inflicted by his charges on the paying customers, and his helpless, gape-mouthed incredulity in response was the only good part of a lot of bad nights. Buck has a much better club and a slower resting heartbeat, so you mostly get steely glares over tight lips — but seriously, doesn’t Jeremy Hefner look a bit nervous every time Buck starts melting laser-beam trails in the field with his eyes?

Anyway, on the Mets go to St. Louis, somehow finished for the year with all things related to the Diamondbacks, states that stay on rebel time out of some kind of weird cowboy-hangover surliness, Madison Bumgarner, Sedona red and other annoying colors that don’t belong on uniforms, D. Baxter the Bobcat and his adventures in the uncanny valley, and games in an ill-lit stadium that looks like someone roofed over a second-tier mall. (Seriously, if you ever go to a Diamondbacks game … it’s deeply weird.)

It will be interesting to see what the Diamondbacks have become by 2023, what with Nick Ahmed and Christian Walker and Pavin Smith and Seth Beer and Sergio Alcantara. Maybe they will have taken a step forward or maybe they will have gone sideways, in which case Torey Lovullo will have started exhibiting a few of Dallas Green’s expressions. We’ll find out then; for now, they’re other clubs’ problem. We’re on to St. Louis, successful formula in hand and fingers crossed.

by Greg Prince on 24 April 2022 1:18 pm On Saturday night in Phoenix, we learned the Mets’ starting pitching depth only goes so far. Because of injuries, we had seen our No. 1A through No. 7 starters acquit themselves brilliantly this season. We haven’t seen No. 1 — Jacob deGrom — but we can vouch for his brilliance. Everybody else, from Max Scherzer (we’re not calling him No. 2) on through Taijuan Walker for a couple of pre-IL innings, Chris Bassitt, the rejuvenated Carlos Carrasco and the so-called depth pieces Tylor Megill and David Peterson, has delivered in real time.

Alas, we may have to grope around a bit for an eighth starter.

Trevor Williams, at least based on one game’s evidence, may not be the optimal answer for when we have to dig deep to take a stopgap start in a week that involves a doubleheader. Williams has some legitimate credentials as a big league starter, with a fourteen-win season from 2018 the shining star of his portfolio, but he didn’t have a lot of work heading into Saturday at Chase Field. Perhaps it was rust showing or perhaps it was what you get when you have to go to your No. 8 starters. Williams wasn’t necessarily hit hard, but he was hit. In the first two innings of work in what was projected as a bullpen game anyway, Trevor allowed three runs on six hits. To begin the third, he surrendered a resounding double that later came around to score after Sean Reid-Foley replaced him on the mound.

And that was Trevor Williams’ first start of the season, all but assuring the Mets were on their way to a languid 5-2 loss. They were welcome to mount an effective comeback, but they declined. As we’ll remind ourselves, as long as the losses are the aberrations, that’ll happen once in a while.

What hadn’t happened before, meaning at all, is a Mets pitching career encompassing exactly one inning and three strikeouts. But it happened Saturday, via the enticing right arm of Adonis Medina, a pitcher making his sixth major league appearance and first as a Met. Medina was called up with the all-hands nature of the night in mind (Peterson was the numbers game victim to create space) and was assigned the bottom of the eighth to provisionally prove himself.

Can you prove anything in one inning of work, even provisionally? Medina proved one inning can be enough to make an impression. The kid the Mets purchased from Pittsburgh as Spring Training was morphing into Opening Day faced three batters: Geraldo Perdomo, Daulton Varsho and Ketel Marte. The kid also struck out three batters: Geraldo Perdomo, Daulton Varsho and Ketel Marte. No other Met ever has pitched only one inning and did nothing but strike out everybody he faced. Per Baseball-Reference, seventeen Mets have thrown exactly one inning in their tenure in orange and blue (and possibly black). Nine of them were position players. Eight have been pitchers by trade. Only Medina has pitched at a ratio of 27 strikeouts per nine innings, albeit over only one inning. Granted, most relievers who get an inning get another and eventually they’re gonna pop up a batter or produce a ground ball or, sadly, give up a walk or a hit. Nobody stays perfect forever.

For the moment, however, Adonis Medina of the New York Mets is perfect. As much as we learned we can never have enough dependable starters, we already knew we never have enough competent relievers. Until a hitter gets the best of Adonis, we will gaze longingly at his gorgeous stat line and swoon.

by Jason Fry on 23 April 2022 3:23 pm Jeff McNeil lay face down in the Arizona turf, the last out of a 6-5 Mets win safely in his glove. He wasn’t hurt; he just needed a minute.

At that point, we all did.

The Mets moved to 11-4 on the season, which I will use bleeding-edge analytics to categorize as pretty damn good. But it wasn’t exactly a stately march to victory: The game started as a tense affair, became seemingly comfortable, turned a lot less comfortable, descended into debacle territory, and then rose again to end as a triumph. That’s about a week’s worth of emotions packed into the back end of a Friday night and too much of a Saturday morning.

David Peterson was terrific, but Zac Gallen was pretty good himself in facing the Mets for the second time in a week. Pete Alonso was all over the early innings. He ended the first by smothering a ball down the first-base line, followed by a heave to Peterson at first made while lying on his back, but later let in a run with an overaggressive attempt to pursue a ball that should have been McNeil’s. Alonso plays baseball like a Labrador retriever who just lapped up several spilled coffees, and most of the time that’s charming, but on defense our roamin’ first baseman really needs to render unto second basemen those things that are second basemen’s. (Arizona first baseman Christian Walker would later retire Starling Marte on an essentially identical play, which seems weird but actually isn’t because baseball is so reliably weird.) Alonso also chipped in two RBIs in less-than-Olympian fashion: one on a 120-foot pop-up that plopped down in right and the other on a 75-foot chip shot in the direction of first. Not the stuff that inspires odes to Ruthian power, perhaps, but whatever works.

All looked well at stretch time, thanks to a home run by James McCann that traveled about as far as half a week’s worth of McCann groundouts, a redistribution that McCann ought to try more often. But Trevor May gave up a homer to Walker to bring the D’Backs within one, and with two out in the ninth Edwin Diaz did the kind of thing we’d like to believe he no longer does: He left a 1-0 slider in the middle of the plate for Daulton Varsho, who sent it over the right-field fence just beyond Marte’s glove for a tie game.

Like McNeil (sorry, spoilers), I’m going to need a minute here.

The metrics new of fangle and old of school both say Diaz is a pretty effective closer. And no sane fan of any team trusts their closer. Regardless of allegiance, we remember with piercing clarity the saves that get away even as the fuss-free conversions blur into anonymity. Has there ever been a Mets closer I trusted? Off the top of my head, I’d say Jesse Orosco and Randy Myers, but I guarantee if you got into a time machine and quizzed teenage me about either man, I’d fly into a rage about blown saves that older me has mercifully forgotten. I once booed the reliably infuriating Braden Looper so vociferously that I felt something give way in my throat and could only produce a rusty croak for a day and a half. I still wake up in a cold sweat thinking about various Armando Benitez misdeeds, John Franco had me braced for impact every time he took the mound, and Jeurys Familia quick-pitched us into what became October oblivion. Hell, even the sainted Tug McGraw‘s legend was created by overcoming a long stretch in which he’d proved thoroughly unreliable.

Closers exist to torment you, so it’s really on the entire fraternity that I distrust Diaz as completely as I do. Still: Diaz could convert his next 200 saves, give me a kidney and perfect the tokamak fusion reactor, thus ushering in a golden age of free and clean energy for humanity, and when he took the mound I’d still cross my fingers and mutter at him to please not fuck it up this time.

Diaz fucked it up this time, and so the Mets played on, under rules that would have been incomprehensible to young Jace muttering about Orosco or Myers.

McNeil was the Manfred man, moved to third on a (productive) groundout by McCann, but didn’t break on contact when Brandon Nimmo grounded to short. That left it up to Marte, who hit a grounder that Matt Davidson fielded on the long hop behind third. Davidson threw accurately to first and just nipped Marte, who immediately exhorted his employers to challenge. Such insistence is often based more on faith than evidence, but Marte was right: His toe had arrived a split-second before Davidson’s throw, and the Mets had new life and a one-run lead, which they entrusted to Seth Lugo.

Lugo is a frustrating commodity: a highly useful pitcher with a balky elbow that makes his appearances even more of a game of reliever roulette than the MLB baseline. Some nights Lugo reports for duty with hiss on his fastball and sharp break on his curve, and some nights those essentials are missing. This, mercifully, was the first kind of night: Lugo fanned the first two Diamondbacks and then induced a popup from Walker that looked harmless at first and then less harmless as it carried into the outfield and McNeil and sundry outfielders pursued. But McNeil secured it, fell on his face, and the Mets were down but the opposite of out.

There are no moral victories in baseball — if you play with valor and gallantry and tally fewer runs than opponents who conducted themselves like they replaced their baseball caps with KFC buckets, all you’ve done is lose. Similarly, though, there are no immoral victories — come out on the long side of the final score and there is no asterisk denoting crummy middle relief, overamped first basemen or closers’ trustworthiness.

Wins are wins — even the ones that call for a little postgame meditation among the blades of ersatz grass.

by Greg Prince on 21 April 2022 5:38 pm Now it’s getting serious, to the extent that anything can be serious after fourteen games. The Mets are off to a seriously good start and maybe then some. I’m not sure when a start just becomes the season, but fourteen games will do for our purposes. A seven-game road trip with five wins, a seven-game homestand with five wins.

What’s to complain about? That’s a rhetorical question. I’m not interested in a cataloguing of petty gripes, thanks. There are going to be lousy nights, because baseball is notorious for its lack of winning ’em all, but maybe we’ll learn to take the less rewarding of ’em in stride. We do in the abstract. Sitting through them is another matter.

Sitting through games like Thursday afternoon’s 6-2 Mets victory, on the other hand, is a genuine pleasure. Carlos Carrasco gave up a run in the second inning, and guess what — neither the world nor the game ended. The Carrasco who got clobbered by every team in every earliest frame last year like the first inning was the personification of Kyle Schwarber himself overcomes adversity this year. Not that he’s faced much adversity. The batters who face Carrasco would tell a different story from their perspective. Between that single run scoring in the second and the leadoff runner reaching in top of the eighth, eighteen consecutive Giants bit off more Cookie than they could swallow. Eighteen San Franciscans up, eighteen San Franciscans down…and you know how steep those hills in San Francisco can be.

Any particular magic to eighteen consecutive batters retired? No more so than ten wins in fourteen games. Except Carrasco of the 1.47 ERA filed away six perfect innings in a row before allowing a solo home run after seven-and-two-thirds, which is simply very sweet, and the Mets are the first team to reach double-digit victories in the majors. I know that latter statlike factoid because one of MLB’s media rights holders tweeted a big graphic that shouted 10 WINS on our ballclub’s behalf, which made me think that if you give the Mets 14 games, they’ll give us something special.

At the very least, they’ll give us 148 more games.

Hopefully, they will continue to hit like they did at various inflection points of Thursday’s homestand finale, with Eduardo Escobar going deep for the first time as a Met; Francisco Lindor going deep for the fifteenth time as a Met at Citi Field (he’s already in the Top Twenty in that particular category careerwise); and Mark Canha chipping in a clutch two-out, two-run single to extend the Mets’ lead to 5-1 in the third. From there, Carrasco could relax and we could practice breathing easily.

The Mets’ 10-4 record represents the fourth-best 14-game start in franchise history, tied with 1972, 2006 and 2007, trailing only 2018 (12-2) and 1986 and 2015 (both 11-3). Those seasons had loads more games, too, along with varying trajectories and endings. I don’t throw this data point onto the informational table to draw absolute conclusions in April. Just showing you that a start of 10-4, good buddies, doesn’t happen often. Might as well enjoy it until the first pitch of the fifteenth game.

To co-opt a phrase from the late, great C.W. McCall, let these Metsies roll!

Still standing tall outside Citi Field and therefore not a dream is that Tom Seaver statue, a miracle of Metsian sculpting reflected upon in the latest of episode of National League Town. Listen here or anywhere you choose…except maybe over 1010 WINS, whose all-news format makes it an iffy choice to hear Mets podcasts.

by Greg Prince on 21 April 2022 9:11 am The game was lost when balls off the bats of Giants fell in and the balls off the bats of Mets didn’t.

The game was lost was when the Mets pitcher who’d previously given up almost nothing gave up a bunch.

The game was lost when the only Belt in the game delivered the only belt of the game.

The game was lost when the Mets’ resident speedster turned greedster and tried to steal a base that would have been better off left alone.

The game was lost when the visiting third baseman for whom this ballpark used to be home, and for whom the home infield was more useful as a stage for human emotions than as a showcase for elite defense, stabbed a potential momentum-turner out of the air.

The game was lost when the Met dugout revealed three temporary managers rather than the one usual manager, which is to say the Mets had zero managers.

The game was lost coming out of halftime when the Nets couldn’t stop the Celtics…sorry, that was the other thrill of my winless Wednesday night.

The one you came here to join me in moping about was the 5-2 defeat the Mets endured at the hands of the Giants, a game that wound up close on the scoreboard but failed to get there in feel. San Francisco pulled ahead early and never yielded its advantage (the Nets could take a lesson). Carlos Rodón went largely untouched. Chris Bassitt didn’t, even if he lasted a long while because no manager anywhere any longer has to think about pinch-hitting for the pitcher — which was fine, because the Mets had no manager. Certified Leader of Men William Nathaniel “Buck” Showalter had to take care of something medical and left the store in the six nominally capable hands of three lieutenants: Eric “Chavy” Chavez, Dick “Dicky” Scott and Jeremy “Hef” Hefner. I would have preferred a single interim skipper, just on principle. Lot of first mates on Wednesday night, but not a single Jonas Grumby to take charge.

The crowd around the helm didn’t matter. The Mets’ mini-rallies didn’t matter. Bloops working to one team’s advantage more than the other didn’t matter. The Mets’ inability to match Brandon Belt in the power department didn’t matter. Starling Marte getting erased at second on a two-on, two-out stolen base try that probably shouldn’t have been attempted, given that DID I MENTION THERE WERE TWO OUT, could have mattered, but didn’t. The two-on, two-out line drive that never touched grass (via Dom Smith’s sweet swing, bitterly thwarted by the glove of Wilmer Flores, to name an unlikely leaping defender) mattered in the moment, but didn’t matter ultimately. Even the last-second reprieve derived from Marte’s redemptive sprint down the first base line earning a reversed call with two out in the bottom of the ninth didn’t matter. There were always two out when something seemed ready to happen but didn’t.

It all mattered until none of it mattered. The Mets weren’t going to find a way to not lose this game. Some nights are just like that.

by Jason Fry on 20 April 2022 12:30 am Last season, as you may not wish to recall, Francisco Lindor had a rather rough introduction to New York: a batting average stuck below the Mendoza line until June; a frustrating run of injuries; an embarrassing public disagreement with his double-play partner that it was instantly obvious had nothing to do with furry four-footed creatures, no matter how much a smiling Lindor tried to sell it. That double-play partner, Jeff McNeil, saw his offensive production crater, going from much-admired line-drive hitter to baffled and baffling enigma. As for Max Scherzer, he was in Washington, where we hoped we encountered him and his filthy arsenal of pitches and his bulldog demeanor as infrequently as possible.

A year later, Scherzer is somehow here, having joined Lindor and McNeil — who sure look a lot happier. As do we all, suddenly.

The Mets came into a chilly Tuesday afternoon with a 7-3 record, but one amassed against teams whose prospects ranged from “flawed” to “pathetic.” The San Francisco Giants promised a sterner test, boasting a 7-2 record and coming off a season in which they shocked everyone, possibly including themselves, by winning 107 games.

What a difference 10 hours or so can make. The Mets won both ends of a doubleheader, meaning they’ve now beaten San Francisco more often in 2022 than they did in the entirety of 2021. They’re 9-3 and warnings about flight and proximity to the sun seem in order.

The afternoon didn’t start promisingly, as the Giants took a 4-1 lead against a suddenly mortal Tylor Megill, with the last two runs coming off the bat of Brandon Crawford in a situation where the Mets might have opted to pitch to Thairo Estrada instead. But Megill prevented further harm, and in the fifth the Mets erupted, with doubles from James McCann (???!!!), McNeil and Lindor tying the game. Seth Lugo looked shaky again but escaped in the eighth, slipping a fastball past Jason Vosler. The Mets looked like they had a wild Camilo Doval beaten in the ninth, but the young Giant found his slider in the nick of time, fanning Travis Jankowski and Dom Smith.

On to the 10th, and the first ludicrous Manfred men of the season. It looked like the Giants would draw blood in the top of the inning, as Lindor threw wide of first and pulled Pete Alonso off the bag, turning the third out into an error and a run scored. But hold the phone, or rather get an umpire onto said headset to ring up Chelsea. The Mets challenged the call, and the briefest look at the replay showed they’d been right to do so, as Alonso had contorted himself into an unlikely shape that ended with one toe just touching the base. “BIG STRETCH!” I hollered at the TV, which I suppose made Alonso an honorary housecat. He came off the field hooting with the joy you’d expect from a man making his case to be more than a DH — and a few minutes later Lindor completed a rapid ascent from possible goat to hero, lashing a ball to right-center that brought home the Mets’ own Manfred man, the just-returned Brandon Nimmo.

They’d won, 5-4, and that was just the matinee!

The nightcap belonged to the new guy, Mr. Scherzer of the heterochromatic eyes and ferocious mien. I’ve watched Scherzer for years, even seen him up close a time or two — most notably from the stands as he no-hit the Mets at the tail end of the 2015 season. (I was also in attendance for Chris Heston‘s no-no that June, a distinction I’d rather not repeat.) But it still seems faintly astonishing that he now wears our livery, transformed with the stroke of a pen on a checkbook from highly respected enemy to pinch-me ally.

Scherzer has that air of meanness common to great power pitchers from Seaver to Santana, a tunnel vision that’s admirable and a little scary to see in action. The wrinkle he adds is a slightly demented restlessness: Where most aces sit in the dugout fixing the field with a stony stare, Scherzer prefers to pace up and down in the dugout, cap off, looking not unlike an unmade bed. His frankly terrible hair does nothing to hide his encroaching male pattern baldness, yet it’s impossible to imagine Scherzer conceivably giving a rat’s ass about something so trivial — if he’s doing something important, he’ll have a baseball cap on, right?

On Tuesday night he was indeed doing something important — blitzing the Giants. He had all five of the pitches in his Saberhagenesque arsenal working, and as he rolled along the Giants hitters trudged up to their appointments with him bearing an air of hangdog disconsolation. You could see them wondering what terrible thing Scherzer was going to subject them to this time and then trudging away once said terrible thing had been revealed, slightly sadder and not particularly wiser.

Scherzer entered the sixth without allowing a hit, got the first two Giants in that inning and then seemed to tire, losing his velocity and location and walking two. Darin Ruf then ended the suspense with a single spanked to left — a mild relief, perhaps. Beyond the fact that it’s April and Scherzer’s debut was delayed by a balky hamstring, the Mets may well need the bullets in that extraordinary arm later in the season.

Anyway, the Mets were up 3-1 and Scherzer had done more than enough, but he came back out in the seventh and put an exclamation point on his night, with his 102nd pitch an absolutely evil 0-2 changeup that Steven Duggar watched in despair as he became Scherzer’s 10th strikeout of the ninth. Drew Smith survived an encounter with Mike Yastrzemski with an assist from the April wind, Trevor May looked the best he has all year, and the Mets had won again.

They won’t do that every night, alas. There will be moments when toes slide slightly off bases instead of adhering to them, and balls spanked into the gap get plucked out of the air, and even aces wind up stuck with bad hands. But worry about that when we have to — for now, enjoy Lindor hitting .310 and McNeil looking dangerous again and Alonso imitating the world’s gallumphing-est ballet dancer and Scherzer pacing and pacing until someone tells him he can escape the dugout again and inflict new cruelties on the opposition. Baseball can be exasperating and mean. We all know that. What we forget sometimes is that you’re allowed to smile and say silly things when baseball’s mild and kind.

by Greg Prince on 17 April 2022 7:43 pm Three paces that would be nice to keep up:

1) If the Mets go 7-3 fifteen more times (105-45) and they’ll be 112-48 with two games to go — and I probably won’t sweat the final two games too much.

2) If Pete Alonso matches his career total of 109 home runs six more times (654), he’ll pass Barry Bonds.

3) If the starters continue to pitch like a many-armed Jacob deGrom, Jacob deGrom would make a helluva middle reliever once he’s healthy.

When most things are going well, carried away is the way to go, if only in one’s head, if only before the San Francisco Giants — 114-59 in regular-season play since the dawn of 2021 — come to town. They may provide a stiffer test than the Nationals, Phillies and Diamondbacks have to this point. Conversely, the Giants have to play the Mets, who not only overcame a stiff wind Sunday, but threw caution to the wind and lived to tell about it.

Early on, when most everything’s been going well, a couple of not-quites have gotten in the way of presumably unattainable Metsian perfection. There’ve been a few instances of baserunners being aggressive and getting thrown out and we’ve seen some relievers come back out for that extra batter or more and be burned for it.

So how did the Mets succeed Sunday? By running the bases aggressively, and with a one-inning bullpen guy sticking around for two. It all worked.

Pete Alonso, before icing the chilly game at Citi Field with a seventh-inning home run that didn’t acknowledge the wind, ran in a gust of fury from first to home on Eduardo Escobar’s one-out double in the sixth. Pete forced a less than ideal throw from right field and trotted home, while Escobar, to whom speed comes more naturally, took third. Up 1-0 in the sixth, Escobar would move up to second when Dom Smith walked — against authenticated Shea-used lefty Oliver Perez — and score via J.D. Davis’s pinch-single. James McCann’s subsequent flyout, the second out of the inning, came in handy as Smith had zipped to third on Davis’s hit.

Now it’s 3-0 and about to be even more fun, though no runs would be generated in the extension of that sixth-inning good time. The Diamondbacks decided Dom left third too soon, potentially negating McCann’s sac fly. That he didn’t, and almost nobody ever does, didn’t matter. They were gonna put the appeal play on. Ollie stepped off the rubber, and…he’s got J.D. stealing second to contend with.

Except he doesn’t, because his job in that moment is to throw to third to theoretically retroactively nail Dom.

Except he’s distracted by J.D., who Buck Showalter has sent to second precisely to completely distract Perez. Had Perez picked off J.D., he of the five career stolen bases in five major league seasons, so be it, figured Buck. It would have been the third out of the sixth, but the important thing was the appeal play was off the instant Ollie didn’t throw to third, and therefore Smith’s run would count regardless of J.D.’s fate.

As it happened, Dom didn’t leave third too soon.

Also as it happened, J.D. stole second.

One more happening: Ollie got Luis Guillorme for the next out, stranding Davis, but the real happening at the end of an aggressively run inning was Buck made sure to protect that third run, the one Smith scored. That third run for a third out was a trade Buck would make in the time it took Frank Cashen to say yes to swapping Neil Allen and Rick Ownbey for Keith Hernandez.

Got all that? Buck did. The Mets did. Ol’ pal Ollie was flustered. The twenty-year veteran and reigning LAMSA or Longest Ago Met Still Active didn’t seem to know what exactly was going on, which was OK, because a) nobody at first glance seemed to understand this baseball version of the tuck rule (something that can’t possibly seem right but is — call it the Buck rule); and b) Buck knew and made sure his players knew exactly what was going on.

The Mets outsmarting the opposition. We could get used to that.

We could also get used to this starting pitching that has carried the Mets away toward their 7-3 record. The combined ERA of everybody who has taken the ball to begin a game is 1.07 through ten games. DeGrom, whose presence may be sorely missed but whose absence hasn’t yet represented a debilitating factor, put up an ERA of 1.08 in fifteen starts last year. It was David Peterson’s turn to give up nothing on Sunday, and he was exactly as miserly as he needed to be. Four-and-a-third innings pitched, no runs allowed. Stingy starting is apparently contagious.

Once the Mets had that 3-0 lead, Chasen Shreve, nominally a lefty specialist, was the pitcher of record, having thrown a perfect top of the sixth. Showalter stayed with him for the top of the seventh. Some of those dreaded ups/downs have seemed to go an up too far, as in, “Why is Shreve getting another inning?” turning into “I knew I was right to moan about getting Shreve getting another inning?” Like Joey Cora waving runners along, Buck isn’t deterred by our intermittent bleats of frustration. Shreve pitched a perfect second inning. It may not always work. On Sunday, en route to a 5-0 win — bolstered by Alonso’s two-run homer in the seventh and preserved by shutout frames from Drew Smith and Edwin Diaz plus a clutch two-thirds provided in the fifth by Trevor Williams — it did. Precedent won’t scare off this manager until he’s convinced it proves something.

The Mets’ 7-3 start is valuable in that four more games have been won rather than lost. Just keep going when the eleventh game begins. Easier said than done? We’re 7-3. That also comes off the tongue with ease.

by Jason Fry on 16 April 2022 11:32 pm On Saturday the Mets lost an oddly desultory affair to the Diamondbacks, 3-2. The ingredients were all there for yet another walk-on-air game: pregame honors for Gil Hodges, pleasant weather, a new statue to admire (haven’t seen it yet but can’t wait), and a big revved-up crowd eager to celebrate.

But having all the ingredients doesn’t ensure that the souffle won’t fall. The Mets and D’Backs ground along scoreless, which was equal parts heartening (Carlos Carrasco looks great!) and dis- (we can’t score a run against freaking Zac Gallen?), until Seth Lugo gave up a two-run homer to nonslugger Sergio Alcantara, followed by a run-scoring double by Ketel Marte. The Mets fought back with a two-run homer by Starling Marte, but it wasn’t enough, particularly not with Mark Melancon on the hill in the ninth. Melancon’s uniform seems to change every year, but the arsenal is the same cruel metronome — cutters on hitters’ hands and curves that dive out of the strike zone, generally with dispiriting effect.

It was one of those games that felt like a slow-moving avalanche that would eventually turn in the Mets’ favor — surely those Arizona outfielders would stop staggering under balls at the last moment to safely cradle them, and surely the Mets bats would discover their recent potency with this latest reliever — except then the hour was late and the avalanche somehow hadn’t happened and then the game was over and so that was definitely the case.

Blame? If I were determined to apportion some, I suppose I could craft an anguished paragraph about how Lugo has looked crummy in two out of his three most recent outings. I could offer you a pitch-by-pitch breakdown to decry how Pete Alonso came to the plate after a four-pitch walk and practically jumped out of his shoes at a pitch he couldn’t drive, producing a fatal double play.

Neither of those airings of grievances would be wrong — Lugo did indisputably look lousy and Pete was pretty obviously overeager. It’s more that it’s so early that I’m suspicious of the context — of any context. In April we’re filling in big patterns via extrapolation from a handful of dots, and a lot of those perceived patterns will be obviously just static by May. Joely Rodriguez looked awful in his first couple of Met outings but was effective today, stuck with the loss through no particular fault of his own. Alonso has been an RBI machine in the early going, even if he hit an empty chamber when needed today. Lugo has enough of a track record that he deserves more than to be discarded before Tax Day. Carrasco’s first two outings have been heartening, but let’s see him a few more times before we declare that he’s healthy and all is well.

It’s a marathon, yet we’re out here sprinting, sweating like sprinkler heads and gasping with our tongues hanging out of our mouths. I know that’s hard to resist when it’s a beautiful day and everyone around you is hooting and hollering. But it’s no way to finish the race. Pace yourself. Take water breaks. Stick with the pack. We’ve got a long way to go and a lot to see — and no idea what scenery lies ahead.

by Greg Prince on 15 April 2022 11:51 pm Technically, the win in the game that commenced the National League season in New York went to Chris Bassitt. Not so technically, actually. Chris, No. 40 in the common guise of No. 42, gave the Mets six superb innings, and when a Mets starting pitcher is backed by sufficient offense, that generally means the starting pitcher who has pitched superbly is in line for a win. The 2022 Mets are suddenly showing a knack for sufficiently offending opposing pitchers. Just ask Zach Davies and Caleb Smith of the Arizona Diamondbacks.

The home team in Friday’s Home Opener did not lack for runs. Three Mets — the aptly first-named Robinson Cano, Francisco Lindor and Starling Marte — produced four homers, with Lindor choosing to smack one from each side of the plate. Among them, the power trio knocked in seven runs. The Met most closely identified with crowd-pleasing home runs, Pete Alonso, satisfied 43,820 with a pair of run-scoring sac flies. Eduardo Escobar chipped in an RBI double as well.

Travis Jankowski likely wasn’t going to be in the lineup, but bench coach Glenn Sherlock wasn’t planning on a) testing positive for COVID-19 and b) coming into close contact with Brandon Nimmo and Mark Canha. Sherlock ended up not coaching and Nimmo and Canha were shuttled to the IL. Jankowski got a start in center, collected three hits and scored one of the Mets’ ten tallies that supported Bassitt and three relievers. The sunniest of baseball afternoons give credence to the adage that when it doesn’t rain, it pours runs.

Because of positive tests that eliminated a pair of outfielders from Buck Showalter’s finely honed plans, not only did Jankowski get a chance to shine, but Nick Plummer suddenly if tentatively owned a roster spot (as did potential next Recidivist Met Matt Reynolds). With a gargantuan lead safeguarding the ninth inning, Showalter allowed Plummer, misspelled by SNY as “PLUMBER” in the pregame introductions, the pleasure of making his MLB debut on defense. Nick thus notched his name (PLUMMER) in Metropolitan annals as the 1,162nd player in team history. His uniform number, you might have guessed, was 42. We’ll learn his “real” digits should he stick around one more day.

Yes, on April 15 everybody wore 42, for the only reason you’d do away with individual numerical identity: to honor the transcendent contributions of Jackie Robinson. Cano, who wears 24 because 42 usually isn’t available, had to love it; he was named Robinson because of Jackie. Jankowski, despite the circumstances that pushed him forward, couldn’t have minded — three hits in four unexpected at-bats look great however they’re cross-referenced. Chasen Shreve, at last a home team Mets pitcher pitching in front of Mets fans rather than the cardboard cutouts who stayed notoriously silent throughout his stint as a 2020 Met, was probably so gratified by the encouraging noise made by tens of thousands of friendly voices that he didn’t worry at all about his number (or NUMMER).

When uniform numbers go missing. For the 75th anniversary of Robinson’s precedent-shattering debut in Brooklyn, MLB decided a blue 42 on players’ backs would be de rigueur for every team, with no numbers on the front for any team. Though it wasn’t intentional, there was an inherent turn-back-the-clock element to the Jackie look for our side. The Mets wore no numbers on the fronts of their pinstriped jerseys from 1962 through 1964. From 1965 forward, the pins have always come numerically enhanced, backs and fronts, with one lone pre-Friday exception that I can recall. On August 30, 1992, the Mets revived their ancient NNOF practice for a Nostalgia Night celebration at Shea Stadium, commemorating their 30th anniversary. They wore 1962 throwbacks, as did the visiting Reds. Bobby Bonilla beat Rob Dibble with a walkoff dinger. As fans coast-to-coast tuned into ESPN witnessed, Dibble disgustedly tore his vintage vest from his torso and left it for somebody else to clean up.

Steve Cohen might relate to the additional task that faced Pete Flynn’s grounds crew that Sunday night. The Mets were a bit of a mess when they became his, and it fell to him to make things more presentable. I don’t know that it was the very first thing he did when he decided some sprucing up of his new property was due, but he clearly took care not long after taking the keys from the previous owners to think about remaking the landscape outside Citi Field.

Specifically, he thought a ten-foot statue would look, oh, Terrific right over…there. That’s the spot — more or less opposite the original Home Run Apple.

Tom is here. The Apple and Tom Seaver, destined to essentially flank the pathway by which so many mass transit-riding and Roosevelt Avenue-parking fans file into Robinson’s Rotunda, theoretically make strange gatefellows. Seaver was traded by an even worse ownership than the one that preceded Cohen’s in 1977. The Apple was installed beyond the right-center field fence by the next iteration of upper management in 1981. The top hat that housed it read “Mets Magic,” which made sense in the context of the advertising that dared to declare the Magic was Back in 1980 (as the campaign faded from relevancy, the text was switched to HOME RUN in 1984, but the Magically themed top hat never went away). The Franchise and the fruit only co-existed at Shea Stadium for one season, during Seaver 2.0 in 1983. Since the Apple only elevated when a Met went yard, it probably wouldn’t have bothered Tom to know someday that very same Apple would always stick up behind him, as if to imply he’d just given up a long one to Terry Puhl. I suspect the juxtaposition of his iconic pitching motion and produce symbolizing the conquest of pitching would probably make the pitcher laugh…and if Tom Seaver had laughed, he would have cackled.

On Friday morning, a couple of hours before No. 42 for the Mets threw the first pitch to No. 42 of the Diamondbacks, we all saw how inspired that choice of statuary really was. Then again, if you’re starting a Home Opener with No. 41, it’s hard to go wrong. Tom Seaver started eight Home Openers in his Mets career. The Mets won seven of them. Tom got the W in six of them.

You may have heard of “the Tom Seaver statue” dating back to all the seasons it could have fronted the Mets’ ballpark but didn’t. Late in the tenure of the previous ownership, the former caretakers of the organization let us know they’d put the statue on order. Mighty sporting of them, with the greatest Met the Mets had ever known or will ever know in no condition to ever see the concept become reality. In March of 2019, Tom Seaver’s family informed his legions of fans that Tom wasn’t doing well enough to be out and about any longer. In June of 2019, the previous ownership announced the statue was in development. Nice timing.

Seaver died late in the summer of 2020, about two months before Cohen took over as owner. I’d like to believe the first call Cohen made once he figured out how to get an outside line was to sculptor William Behrends to see how Big Tom was coming. The second call in my dream scenario was to the offices of Seaver Vineyards to make certain Nancy Seaver would be on hand for the unveiling when the statue arrived.

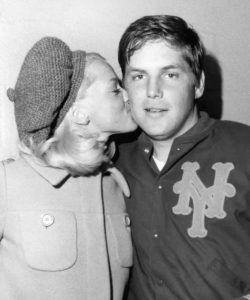

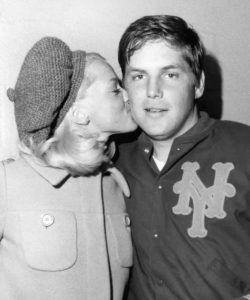

Big Tom and the big day converged at last, and Nancy, in the company of her daughters Sarah and Anne, along with a flock of Franchise family members, was there to greet both. Nancy Seaver used to be at Shea all the time when Tom pitched. They were a matched set. You grew up in New York as a Mets fan and you knew them both. You idolized one. You acknowledged the pair. Maybe you didn’t think about Nancy beyond realizing you knew the name of your favorite baseball player’s wife, but she was a constant. The rock of the operation, you got the feeling. Tom went out and racked up strikeouts and shutouts. Nancy kept the enterprise going. You saw her in the yearbook. You revisited the footage from the World Series where she was resplendent in her trademark tam o’ shanter. You respected them as an entity. The Seavers.

The Seavers. That statue Behrends sculpted — every bit as awe-inspiring as No. 41 himself — should have been unveiled in the presence of The Seavers. Tom should have looked slightly embarrassed by all the fuss, while Nancy should have reminded him, quietly but firmly, no, Tom, you deserve it, you earned it. The ballpark at whose front door it now resides opened in 2009. Tom Seaver visited in 2009. And 2010. And kept coming back until 2013. I don’t know what William Beherends’s schedule was in the years leading up to the opening of Citi Field, but I’m guessing he could have carved out time for a commission of this nature had he been contacted when Tom Seaver was alive and well.

Water under Shea Bridge, one supposes. The important thing is there is a statue of Tom Seaver outside the park where the Mets play, it is magnificent, and it stands tall for every Mets fan to admire. All 3,200 pounds and 311 wins of it. It’s even got the right knee where the right knee is supposed to be. The ideal proposed in this space in 2006 — when we go to games, we can meet by The Knee…the lovingly sculpted joint with the trademark splotch of dirt that Seaver absorbed every time he went into that perfect motion — has at last come to pass.

So has the widely held desire that Nancy Seaver would fly east to see it. She wasn’t here when they rechristened 126th Street Seaver Way. Sarah was here. So was Anne. Tom couldn’t make it by then, and Nancy wasn’t going to leave her husband alone in Calistoga. But one didn’t have to be a certified Seaverologist to infer Nancy wasn’t too happy with the Mets for not having already put up that statue. The street name was a grand gesture in the interim. That took too long, too.

Friday morning, all was forgiven. It was the era of Steve Cohen. It was the era of the larger-than-life statue of the larger-than-life Met. It was the era when Nancy Seaver returned to Queens, every bit the “Mets royalty” master of ceremonies Howie Rose labeled her. Watching her and listening to her was more than making the reacquaintance of a public figure from a prior age. For all the Seaver kids and grandkids who came to Citi Field in 2019 and were back again, Nancy was…Nancy. Of Tom and Nancy. Only Nancy could elegantly slice through the Flushing winds, battle her way to the podium and address the Franchise as he now stands. Prefacing her remarks of gratitude to the crowd, she spoke one-to-41 with Tom.

She was talking to a statue, but she was talking to the love of her life, and she let us eavesdrop. Tom Seaver is the love of our life every bit as much as he is hers. We all spent more than half-a-century together, fifty-plus years lifting each other up, rooting each other on. “Hello, Tom,” Nancy said on Mets Plaza. “It’s so nice to have you here where you belong.”

Due statistical respect to Chris Bassitt, the 10-3 win for the Home Opener this year has to be assigned as it was on so many Opening Days in the Met past. Put it in the books as another W for Seaver.

She deserves it, she earned it.

|

|