The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 11 January 2022 8:11 pm Keith Hernandez filled the hole between the two and four spots in the batting order for seven Met seasons. He filled holes between himself and either the first base line or the second baseman on balls that seemed destined for the outfield. He filled the hole in the knowledge base of one promising young pitcher after another before there was an All-Star catcher on the premises to guide them. He filled in who knows how many teammates on what to look for, what to think, how to be. Although it hasn’t been in uniform, he’s long filled a seat in baseball’s best booth with a proprietary blend of élan and absurdity. And now, finally, he fills a gaping void in Mets history.

Keith Hernandez’s No. 17 will be retired on July 9. With its official removal from circulation and its elevation above the left field stands, the 1986 New York Mets, the winningest team this franchise has ever known, will be represented at the highest level of consecration an organization can bestow.

It was strange that Keith’s 17 went unretired for more than three decades because, well, he’s Keith Hernandez. He transformed the Metropolitans upon his arrival and we view an entire decade for the better largely because of his impact. No number ceremony for Keith and none for anybody associated with 1986 was equally bizarre. Six members of our last world champions have been inducted into the Mets Hall of Fame along with their manager and general manager — Keith received his bust in 1997 — but not a soul responsible for the 108 regular-season victories had his digits totally and completely immortalized in the 35 years that followed their World Series celebration. Hell, Keith was the 17th-most recent Met to wear 17, which is to say 16 Mets have worn it since Keith, and that’s with nobody wearing it after Fernando Tatis in 2010.

The non-retirement of 17 and its continual random assignment made for a pretty dependable running gag in the SNY booth. Show the Mr. Koo clip (there’s only one) and Keith might let out a harumph. But after a while, fun was fun. How on Bill Shea’s green earth was 17 one of those numbers that any Graeme, Dae or Lima might take the mound in? Even Tatis the elder, a legitimate major league hitter during his Flushing residency, was a stretch. Keith Hernandez had to watch No. 17 in action on the back of anybody who wasn’t Keith Hernandez? While 1986’s hole went unfilled?

Enough of that, at last. We got Keith Hernandez in 1983. Keith Hernandez gets his number retired in 2022. Time lapse notwithstanding, it’s almost a good a deal as that June night we sent Neil Allen and Rick Ownbey to St. Louis in exchange for one of the best things that ever happened to us.

by Greg Prince on 4 January 2022 1:25 pm “There’s gonna be a lot of talk tonight,” Oscar Madison warned his audience during his tryout as a sports talk radio host in 1974. “Some of it you’ll like and some of it you won’t.” This was after he heeded his roommate Felix Unger’s advice and altered his style to reflect the hostility, sarcasm and venom that Felix identified as his strong suits.

Well, we have a few of those qualities warming up in the bullpen any given night, but we’ll save ’em for the next three-game losing streak. All the talk we’re about to tune in for is talk you should sincerely like because most of it reminds us how much fun the Mets can be when we come across them out of context and with no competitive implications.

It’s Oscar’s Caps time! For the tenth consecutive year, we review the previous twelve months’ worth of sightings of our New York Mets in the popular culture — television, movies, novels, basically anywhere you don’t necessarily expect to discover the Mets…and we don’t mean the postseason, ya wiseacre.

“The good news is it’ll be available again during the playoffs.”

—Wiseacre Seth Meyers, Late Night, January 13, 2021, on Citi Field being used as a 24/7 COVID vaccination facility…after which he acknowledged the Mets have a new owner but that he’ll keep making these stale jokes until the standings dictate otherwise

Seth Meyers announced early in 2022 that he tested positive for COVID. Because he’s vaccinated and boosted, he says he’s feeling fine, and we’re glad, even if he takes one too many shots at the Mets (FYI, Seth, Oscar’s foray into insult radio wasn’t a ratings-grabber).

Meyers’s jab might fall into the category of talk you won’t like. We’ll also throw in this scene from a 2021 episode of Showtime’s American Rust, which takes place in a downbeat town in Pennsylvania. The cranky dad played by Bill Camp is watching what looks like a Fox News report about immigration. His half-Mexican daughter who moved to New York is watching with him.

DAUGHTER: Do we have to watch this? Is there a Pirates game on?

DAD: I thought you would have become a Yankees fan by now.

DAUGHTER: At least it’s not the Mets.

DAD: That’s my girl.

Those two probably still carry NL East bitterness from 1973 and 1988.

Anyway, back to talk we do like.

As ever, the Oscar’s Caps, named for the Mets cap Jack Klugman wore in so many episodes of The Odd Couple (and Tony Randall put on for effect a couple of times), are awarded for whatever we noticed in 2021 if it’s something that was brand new; something from a previous year that we’d never seen before; or maybe something that we vaguely remembered from ages ago but were only lately able to flesh out. Although our internal staff is as vigilant as possible, it has limited shall we say bandwidth and can’t possibly monitor everything beamed or streamed. Thus, this project has become a manifestation of generous Metsopotamian crowdsourcing, and we extend our thanks to all who alert us when they see something or hear something relevant to our eternal quest to document every last Mets cap, Mets jersey or Mets murmur.

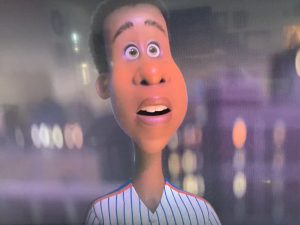

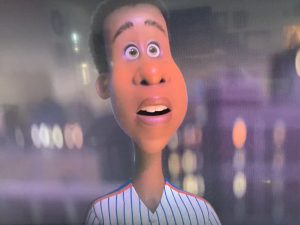

A great example of how the Oscar’s Caps works when it works best came at the end of 2020, when we presented the ninth annual edition of this feature and multiple readers piped up to let us know about Soul, the Pixar movie that had just debuted on Disney+, and why it was right up our alley. Sure enough, within the narrow window when I had access to a subscription, I was able to see for myself that, in a flashback scene, our hero Joe Gardner wears a 1980s-style Mookie Wilson jersey, replete with racing stripe (although designed with buttons, which weren’t a part of the racing stripe uni motif until 1991). Mets posters are visible on the wall of Buddy’s Barber shop as well. A great example of how the Oscar’s Caps works when it works best came at the end of 2020, when we presented the ninth annual edition of this feature and multiple readers piped up to let us know about Soul, the Pixar movie that had just debuted on Disney+, and why it was right up our alley. Sure enough, within the narrow window when I had access to a subscription, I was able to see for myself that, in a flashback scene, our hero Joe Gardner wears a 1980s-style Mookie Wilson jersey, replete with racing stripe (although designed with buttons, which weren’t a part of the racing stripe uni motif until 1991). Mets posters are visible on the wall of Buddy’s Barber shop as well.

Edward Burns’s 2021 Epix series Bridge and Tunnel definitely dispensed a flavor worthy of its Mets fan creator. Set in 1980, a Rusty Staub poster is visible, as is one of Burns’s own 1970s-era Mets road jerseys (worn by Pags, played by Brian Muller). Audio of Bob Murphy announcing a Mets foulout contributed to the soundtrack. In the third episode, Burns, as Artie Farrell, says of Tom Seaver, “I swear to Christ, it breaks my heart to see him in that Cincinnati uniform.”

If it breaks your heart to see another noteworthy righty in another uniform, maybe you couldn’t have imagined that on the night Pete Alonso won his second Home Run Derby (July 12, 2021), when Noah Syndergaard visited Late Night with Seth Meyers and discussed his book club, his ice baths and other aspects of his ongoing rehab from Tommy John surgery, he’d be trying on Angel togs by November. Yet because he hadn’t been anything but a Met by the time Jeopardy aired on December 28, 2021, we’ll count this, too, as Oscar’s Capworthy. It’s from the category “Noahs” for $600.

“With Scandinavian roots and a hammer of a curveball, pitcher Noah Syndergaard got this nickname. The hair helps.”

“Who is Thor?”

“Did you type up that Tom Seaver interview?”

—Oscar to a distraught Myrna (Sheldn — not Sheldon — has left her), “Rain in Spain,” The Odd Couple, Season 5, Episode 1, September 12, 1974

Tom, of course, was in a Mets uniform the night Myrna and Sheldn — real-life couple Penny Marshall and Rob Reiner — got together for good; on the night after, Tom would shut out the Cubs (on the night before, the Mets lost in 25 innings to the Cardinals).

Garry Marshall, who executive-produced The Odd Couple during its 1970-1975 run on ABC, wrote in his memoir Wake Me When It’s Funny that he always liked to cast character actor Hector Elizondo in his movies because Elizondo lent a sense of maturity to the business at hand. Perhaps it’s appropriate that Elizondo picked up Klugman’s — or Oscar’s — cap over the past year. In the November 4 episode of B Positive (Season 2, Episode 4 — “Baseball, Walkers and Wine”), Drew (Thomas Middleditch) takes Harry (Elizondo) to a Hartford Yard Goats game, where Harry wears a Mets cap, one with a blue rather than orange squatchee (implemented 1997) and no MLB logo (implemented 1992) on the back, indicating that, like Harry, the cap has been around, or is perhaps is a non-licensed knockoff. Garry Marshall, who executive-produced The Odd Couple during its 1970-1975 run on ABC, wrote in his memoir Wake Me When It’s Funny that he always liked to cast character actor Hector Elizondo in his movies because Elizondo lent a sense of maturity to the business at hand. Perhaps it’s appropriate that Elizondo picked up Klugman’s — or Oscar’s — cap over the past year. In the November 4 episode of B Positive (Season 2, Episode 4 — “Baseball, Walkers and Wine”), Drew (Thomas Middleditch) takes Harry (Elizondo) to a Hartford Yard Goats game, where Harry wears a Mets cap, one with a blue rather than orange squatchee (implemented 1997) and no MLB logo (implemented 1992) on the back, indicating that, like Harry, the cap has been around, or is perhaps is a non-licensed knockoff.

Harry continues to wear the cap in the next episode (“Novocaine, Bond and Bocce,” S. 2, E. 5, November 11, 2021) while playing bocce, potentially making the Mets cap a running character trait à la Oscar Madison.

“All right, H.B. If you’ll play ball with me, I’ll play ball with you.”

—Darrin Stephens (Dick Sargent), “The Phrase is Familiar,” Bewitched, January 15,1970 (S. 6, E. 17) — as soon as he spouts this cliché (per Endora’s spell), Darrin and the client to whom he’s speaking are suddenly wearing Mets uniforms. Darrin’s is No. 9, with the MLB patch from the 1969 season, à la J.C. Martin.

In Perilous Gambit: A Mike Stoneman Thriller by Kevin Chapman (2021), the titular New York City detective visits Las Vegas and stumbles across a January 2020 reunion of former Met farmhands who played for the Las Vegas 51s. Mike is pleased to exchange pleasantries with Dom Smith a couple of chapters after hearing “Takin’ Care of Business,” revisiting late-period Shea Stadium in his mind and declaring to his companion that the song “always makes me think about a Mets win”. (In Mike’s previous adventure, the football-themed Fatal Infraction, our baseball-first crimefighter took time out to take his godson to a Mets game.)

Mario Reyes (Luis Figueroa) is a Cy Young Award winner who has just signed a $175 million contract with the Mets and is buying a waterfront mansion in Connecticut in the 2014 film And So It Goes.

The third-season premiere of FXX’s mostly animated anthology series Cake (July 9, 2020) had a short showing the Miracle on the Hudson from the perspective of the geese, prominently featuring the soon-to-be demolished Shea Stadium.

In the 2021 novel Out of a Dog’s Mouth by McNally Berry (who’s never been seen in the same room as Mets non-fiction author Matthew Silverman), there are dogs not coincidentally named Choo Choo, Turk and Kooz, plus a person named Robert Person.

The induction of the Beastie Boys into the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame nearly ten years ago, on April 14, 2012, reminded their fans that as the Beasties were rising to superstardom, Adam Horovitz, a.k.a. King Ad-Rock, regularly showed his Met loyalty. One of the portraits of the trio that was projected while LL Cool J and Chuck D inducted them featured Horovitz in his mid-1980s pose, which meant it was topped by a Mets cap. After Adam “MCA” Yauch died on May 4, 2012, the Mets played nothing but Beasties Boys songs as starting lineup walkup music in his memory during their home game of May 5. “Fight For Your Right,” whose video is where Horovitz’s Mets cap got its most play in 1986 and 1987, started up Ike Davis’s trek to the plate.

“Do you remember the ’86 Mets-Red Sox World Series? Bill Buckner let a ground ball go between his legs and the Sox lost the game and eventually the World Series. Very few people remember who was on the field that day, but everyone remembers that Buckner missed the ball. And a baseball’s a lot smaller than your ball, which is not dropping.”

—Mr. Buellerton (Matthew Broderick) stressing to Claire Morgan (Hillary Swank) the importance of fixing the ball supposed to drop in Times Square in the movie New Year’s Eve (2011)

“I’m a big Mets fan to this day. The ’86 Mets was right like when I was 12, 13, this huge team […] I had a big crush on Tim Teufel because he seemed like a wallflower to me. He platooned at second base with Wally Backman and had chipmunk face, and I was just like ‘us!’ I had a very elaborate fantasy that I was married to Gary Carter, who was the star catcher, but that Gary Carter was mean to me and that Tim Teufel would be the guy who sort of wooed me. I fantasized about having a bad marriage to Gary Carter. And he was the kind of guy who was like, ‘Where’s a pen?! Is there a pen in this house?!’ And I’d go into the other room and Tim Teufel would take me out.”

—Jessi Klein, who would later perform as Jessi Glaser and serve as consulting producer on the Mets-friendly Netflix show Big Mouth, doing standup at Joe’s Pub, December 23, 2009

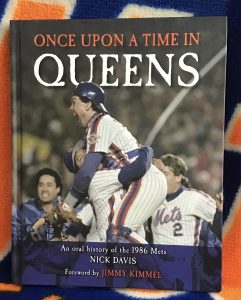

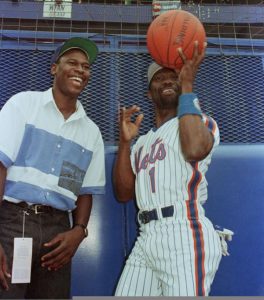

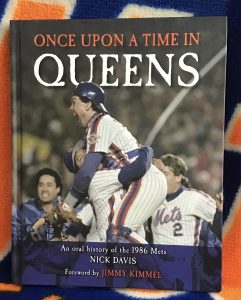

As long as 1986 has come up, let us note the back-in-the-day releases of the twelve-inch singles “Get Metsmerized” and “Let’s Go Mets” along with the visit of Roger McDowell and Lenny Dykstra to the MTV set, where Dykstra hit on VJ Martha Quinn, a little more than 35 years ago. All of this was featured in the Nick Davis opus Once Upon a Time in Queens, the Mets Pop Culture event of 2021. It was written about in some detail here. As long as 1986 has come up, let us note the back-in-the-day releases of the twelve-inch singles “Get Metsmerized” and “Let’s Go Mets” along with the visit of Roger McDowell and Lenny Dykstra to the MTV set, where Dykstra hit on VJ Martha Quinn, a little more than 35 years ago. All of this was featured in the Nick Davis opus Once Upon a Time in Queens, the Mets Pop Culture event of 2021. It was written about in some detail here.

Now for some more 1986-related content…

David Brenner invited a pair of world champion Mets on his ABC late night show Nightlife on consecutive Mondays in 1986, Ron Darling on November 24 and Keith Hernandez on December 1 (each airing followed a New York team playing on Monday Night Football). Brenner, a Philadelphia native, wore a Mets sweatshirt for the Hernandez show. Keith recalled the NLCS vs. Houston as a better postseason series than the World Series and told the already legendary story about retiring to Davey Johnson’s office with two out and nobody on in Game Six against Boston. He also explained he didn’t smoke in the offseason, only at the ballpark to relax. His take on Mets fans, no more than about 2,000 of whom would be at Shea when he came in with the Cardinals, is that they deserved this because they’d waited a long time, 17 years. (Hernandez would return to Brenner’s show the first week of the 1987 season.)

In the 2021 documentary Street Gang: How We Got to Sesame Street, a 1968 commercial that was part of the “Give a Damn” campaign from the New York Urban Coalition is cited as the primary inspiration for the look of the landmark children’s educational program. In that commercial, excerpted in the documentary, actor Lincoln Kilpatrick suggests viewers “send your kid to a ghetto for the summer” and leads a world-weary tour of what underprivileged city youth faced every day. Among other things, we see kids trying to play stickball in the street while having to dodge cars. Kilpatrick turns toward the camera and shrugs, “It’s not Shea Stadium, but it’s exciting.”

In the credits to Street Gang, the show’s cast and crew provides the chorus to a respectable rendition “Put Down the Duckie,” with one of the women singing quite visible in her white 1986 World Champion Mets sweatshirt. Mookie Wilson and Keith Hernandez were not on hand for this singalong, though they did appear on Sesame Street twice in 1987 — with the Count on April 15 and with Snuffleupagus on May 11 — and take part in a celebrity “Duckie” extravaganza that aired on PBS on March 7, 1988.

November 30, 2016 Wahlburgers (Season 7, Episode 4 — “Take Me Out to the Paul Game” on FYI): in the process of preparing to throw out the first pitch at a Brooklyn Cyclones game, Donnie Wahlberg meets Mookie Wilson, which inflicts Game Six flashbacks from 1986 on the Massachusetts native actor/singer.

“So anyway, Vlad, it’s 1986, and I’m at Studio 54 with Tommy Lee and Wally Backman. Bad guy, nasty guy, nice to me, though. He was in a platoon with Tim Teufel, do you remember Tim Teufel?”

—Seth Meyers, imagining Donald Trump riffing during a previous summit with Vladimir Putin, Late Night, June 17, 2021 — and not taking a shot at the Mets, so we’re cool with it

On July 4, 1989, CBS aired a pilot for a sitcom version of the hit film Coming to America, this iteration starring Tommy Davidson as Prince Tariq (younger brother of Eddie Murphy’s character from the movie). Tariq wore a period-appropriate satin Mets Starter jacket, festooned with pins, just as Prince Akeem did in the movie when he decided to blend in with common New Yorkers. Though the pilot was not picked up, the sitcom NBC showed the very next night, The Seinfeld Chronicles, starring another standup comic who worked the Mets into his show, would eventually find a spot on its network’s prime time schedule and within Mets Pop Culture legend.

On February 25, 2021, life imitated art as Francisco Lindor wore the same Mets jacket Eddie Murphy wears in Coming II America as he arrived for that day’s Spring Training activities. The team’s Twitter account captured him greeting nobody in particular, “Good morning, my neighbors!”

At the 44:45 mark of the 2021 Netflix movie MOXIE!, a 1989 Topps Record Breaker card hailing Kevin McReynolds for setting a new standard for stolen bases without being caught in a season (21) appears as part of a zine…except the card has been doctored to cover McReynolds’s face with a sad-face emoji and cowboy hat. At the 44:45 mark of the 2021 Netflix movie MOXIE!, a 1989 Topps Record Breaker card hailing Kevin McReynolds for setting a new standard for stolen bases without being caught in a season (21) appears as part of a zine…except the card has been doctored to cover McReynolds’s face with a sad-face emoji and cowboy hat.

When not stuck in a traffic jam in Harlem that’s backed up to Jackson Heights on Car 54, Where Are You? Toody gets jealous when Muldoon becomes friendly with an intellectual rookie cop. Feeling left out of suddenly elevated cop car conversation, Gunther finds himself partnered with Leo Schnauser and tries to conjure up a sophisticated level of dialogue himself, leading to this exchange:

TOODY: I hear they’re tearing down the Met.

SCHNAUSER: They’re tearing down the New York Mets, the new baseball team? How can they tear them down, they haven’t even been built up.

— “How Smart Can You Get?”; Season 1, Episode 23; February 25, 1962

This may have been the first Mets mention in the popular culture. The Original Mets were still stretching in St. Petersburg when the officers on Car 54 were talking about them. Truly, New York couldn’t wait one half-hour longer to get back to being a National League town.

The Mystery of the Mets by Kevin Mahon, published in 2019, is a murder mystery whose action is set at Shea Stadium. Released in 2021 as The New York Mets: A Shea Stadium Mystery.

Clips of Stone Cold Steve Austin, in his Mets jersey (No. 3:16), chatting with GM Steve Phillips from Austin’s first-pitch appearance at Shea Stadium, July 10, 1999 (the Matt Franco Game), show up in the Austin edition of Biography: WWE Legends that premiered on A&E April 18, 2021 We see the wrestler exchanging greetings with Derek Jeter and signing a baseball while GM Steve Phillips hovers nearby.

On Gilligan’s Island, “The Hunter,” (Season 3, Episode 18; loosely based on The Most Dangerous Game; January 16, 1967), Gilligan, the Professor, the Skipper and Mr. Howell are tuned in to a radio broadcast announcing that the Dodgers shut out the Mets 4-0, meaning the Skipper owes Mr. Howell “three-hundred thousand twelve bananas,” which the Skipper tells Mr. Howell he can subtract from the “nine hundred and sixty mangos you owe me from playing gin”.

“A fan rushed the field at the Mets-Giants game last night and stood on the pitcher’s mound. Thankfully, he was only able to strike out a few Mets before he was apprehended. Sorry, everyone on the crew.”

—Seth Meyers during his Late Night monologue, August 17, 2021 (we feel your pain, Late Night crew)

A subway station advertising billboard featuring Lee Mazzilli, Neil Allen, Joel Youngblood and Craig Swan using Gillette Foamy (with the message, “This year we’re getting back into the thick of it”) appears in the 1982 movie Smithereens.

On the June 1, 1989, episode of Classic Concentration, a drawing of a Mets player tipping his cap constituted a third of a puzzle whose answer was “Captain Kidd” (the other illustrations were of the ten of hearts and a couple of goats).

John Leguizamo wore his omnipresent Mets cap in the 2021 filmed production of the play Waiting for Godot, presented in the form of a Zoom call in these lingering pandemic times.

Visible behind Michael Che as he guested via Zoom with Howard Stern in 2021: a Darryl Strawberry poster of yore.

In the Wiseguy episode “Last Rites for Lucci” (Season 1, Episode 10 — or 11, depending on how you count the pilot; November 19, 1987), Nick Lucci (James Andronica) tells Vinnie Terranova (Ken Wahl) of his current state, “I get a check every week, a few beers every Friday. If the Mets win, I’m happy. I’m not aimin’ high anymore, Vinnie.”

“I see ya forgot about the ’69 Mets. They didn’t have the hitting or the fielding of the other teams, but they won the World Series. And you know why? Showers.”

—Coach Morris Buttermaker (Jack Warden), convincing his team they need to clean themselves up after games, in the sitcom version of The Bad News Bears, “Nakedness is Next to Godliness” (Season 1, Episode 3; April 7, 1979).

“First of all, uniforms do not a baseball team make. I mean, in order to have a good team, you gotta have determination… gotta have hustle…and skill…look at the New York Mets.”

“They have uniforms.”

—Chet Kincaid, unsuccessfully attempting to persuade his Little League team, the Tigers, that uniforms are not intrinsic to their potential success once a plan to purchase uniforms falls through The Bill Cosby Show, “The Worst Crook That Ever Lived” (Season 1, Episode 18; January 25, 1970).

The fact that the 1969 Mets took showers and wore uniforms may or may not have influenced guitarist Brian Bell’s decision to wear a Mets cap while performing with Weezer at Citi Field on the Hell Mega Tour, August 4, 2021.

“I looked at the building there in L.I.C., where all the Mets live.”

—One of Wally’s college buddies, musing over local real estate, Awkwafina is Nora from Queens (“Shadow Acting,” Season 2, Episode 8, September 29, 2021)

In the 2021 Netflix documentary Untold: Deal With the Devil, a photo of boxer Christy Salters Martin (the film’s subject) and Jason Isringhausen in his Mets uniform briefly appears.

Rapper Fred the Godson wore an orange Mets cap with a blue bill in his 2014 video for “The Session 4,” which was incorporated into the story of his death from COVID-19 in the first part of Spike Lee’s NYC Epicenters 9/11 —> 2021½, which first aired on HBO on August 22, 2021.

In the 2019 film Ode to Joy, lead character Charlie (Martin Freeman) — who has problems coping with joy — wears two different Mets t-shirts and a Mets cap

On Brooklyn Nine-Nine in “Renewal,” Season 8, Episode 8 (September 2, 2021), Jake Peralta (Andy Samberg) finds himself with no battery power in his phone because he used it “mining for MetsCoin. It’s the first cryptocurrency that is also the Mets.”

British comedy team Tony Hendra and Nick Ullett performed “The Agony of a New York Mets Fan” on The Ed Sullivan Show, August 7, 1966. Hendra donned a Mets cap and became not just an American, but a prototypical New Yorker. Ullett portrayed “an unintelligent, inquisitive, twittering Englishman — in other words himself”. Sitting on stage as if at Shea Stadium, Hendra’s Mets fan suffers both the Mets’ mishaps and his grandstand neighbor’s clueless queries. Key exchange:

“I don’t know anything about the game.”

“You and the Mets both.”

For a handful of performances in 1981, Paul Dooley donned a Mets jacket and portrayed the lead character in The Amazin’ Casey Stengel or Can’t Anybody Here Speak This Game? at the American Place Theater. Frank Rich did not care for the production, or as he ended his review in the New York Times, “Can’t anybody here write a play?”

In 2021’s dystopian novel The Body Scout by Lincoln Michel, baseball teams are owned and operated by big pharma. Fighting for the pennant? The Monsanto Mets. Their best player, JJ Zunz, dies while batting in a playoff game (but at least these Mets made the playoffs).

“Quick favor — could you look up all the Mets scores for me for the last 37 years?”

“Again, the Mets?”

“Just tell me how many RBIs Keith Hernandez had in ’87? Give me something!”

—Pete, the scoutmaster with an arrow lodged in his neck since 1985, Ghosts, “Viking Funeral,” Season 1, Episode 3 (October 14, 2021), beseeching the new owner of the haunted house where he and the other spectral title characters reside to put her laptop to good use

For the record, Pete, Keith Hernandez drove in 89 runs in 1987.

In “Fortunate Son,” the third episode of Season 3 of The Sopranos (March 11, 2001), Johnny Soprano, in a flashback, is shown reading a newspaper sports section on October 25, 1969. A partial headline says “Mets Decision,” likely alluding to the Mets having given Ed Charles his unconditional release the day before.

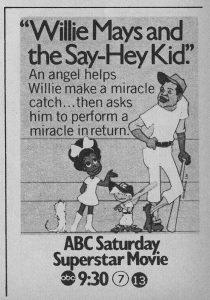

An animated version of Shea Stadium appears in Willie Mays and the Say-Hey Kid, which aired on October 14, 1972, as part of The ABC Saturday Superstar Movie series. In it, Willie has a guardian angel named Casey. Willie provides the voice to his character.

“You’re so desperate to stay relevant, to stay in the game, you can’t see that the game has passed you by. Willie Mays in center fielder for the Mets, misunderstanding the dewy eyes in the crowd for love.”

“You just never understood me or the Say Hey Kid. You play until your feet break. And they carry you off the field in a box.”

— Chuck Rhoades and Chuck Rhoades, Sr., Billions, “Victory Smoke,” Season 5, Episode 11, September 26, 2021

Richie Zyontz, an NFL producer for Fox and longtime friend of John Madden’s, appeared in the All Madden documentary that he was instrumental in shepherding to reality — it debuted on Christmas Day 2021 — and recalled, “I’m just a street kid from New York hired to be a broadcast associate…” while a photo of him in a Mets cap with Madden in the late 1980s pops up. Zyontz’s reverence for legends was apparent earlier in 2021 when he had a “Whack Back at Vac” note to Mike Vaccaro published in the New York Post calling for the Mets to retire 24 in honor of Willie Mays.

Heading from the sublime Say Hey Willie Mays to a let’s say less sublime New York National League icon, in the rebooted version of The Wonder Years (“The Club,” Season 1, Episode 3, October 6, 2021), Dean looks forward to getting to school and swapping baseball cards, especially the opportunity to “unload my Marv Throneberry card”.

It wouldn’t be a year in Mets Pop Culture without somebody sporting one very familiar head repeatedly sitting in front of us.

• In “Mothers and Other Strangers,” The Simpsons, Season 33, Episode 7 (November 28, 2021), Homer tries out a therapy app called Nutz that, among other things, promises “CBD gummies in the shape of your version of God,” with four icons appearing on his phone: Buddah, Jesus, a question mark and a pretty good Simpsonian rendering of Mr. Met.

• On the January 27, 2021, edition of Full Frontal, Samantha Bee explained getting a COVID-19 vaccine at a sports venue would be an issue for her since she’s “not allowed within a thousand feet of any professional sports stadium in this country” after “I tried to take off Mr. Met’s baseball and I realized it was his real head.” The gag was accompanied by a what we’ll call a disturbing image.

• On September 20, 2021, to welcome Mayor Bill de Blasio — who played himself on TV for eight years — to Queens Borough Hall for hizzoner’s week of conducting the city’s business from Queens, borough president Donovan Richards presented de Blasio with “a little mascot [of] the New York Mets. We hope to continue to try to convert you,” which the mayor accepted graciously: “Yeah, this is cool. This could do it right here.” The Red Sox-rooting mayor kept the miniature Mr. Met by his microphone for his further media appearances at Borough Hall. (A montage of Queens scenes behind him included a Mets logo with the message LET’S GO METS!!!!!)

In “Hello, It’s Me,” the premiere episode of And Just Like That…, the reboot/revival of Sex and the City (released on HBO Max, December 9, 2021), Carrie asks Big, “How was your day?” and he replies, “Perfect. The Dow and the Mets — both up.” Carrie’s reply: “Very nice.”

(Big, alas, doesn’t get to experience any more Mets games after that exchange.)

On the premiere of The Jerry Lewis Show on ABC, September 21, 1963, Lewis, from behind a desk, calls for a pack of L&M cigarettes as prelude to a live commercial read. Somebody off camera tosses him the pack, which hits Lewis in the chest, eluding his grasp in the process. As the host picks the cigarettes up, Lewis not quite good-naturedly remarks to the unseen person whose attempt an assist went awry, “You should play with the Mets.” On that very Saturday, the last-place Mets indeed committed three errors, yet prevailed over the Giants at Candlestick Park, 5-4.

Mets Pop Culture headliners Yo La Tengo promoted/commemorated their 2021 Chanukah residency (“I Am Curious Yo La”) at the Bowery Ballroom with a poster featuring animated figures very close in form to Mr. and Mrs. Met…minus the uniforms, if you will. Mets Pop Culture headliners Yo La Tengo promoted/commemorated their 2021 Chanukah residency (“I Am Curious Yo La”) at the Bowery Ballroom with a poster featuring animated figures very close in form to Mr. and Mrs. Met…minus the uniforms, if you will.

“I think the Mets are going to all the way this year.”

—“Glass half-full kind of gal” MJ displaying the “relentless optimism” Peter Parker loves in Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

“On Sunday Hugh attended a Mets game with his old friend Jeff Raen. He called yesterday to announce that he now loves baseball and tried to sound all butch about it. ‘Jeff’s son had a soccer match so we had to leave in the sixth inning,’ he said. ‘I watched the rest of it on TV and then read the review in this morning’s paper.’

“Review?”

—April 29, 2003 entry in A Carnival of Snackery: Diaries 2003-2020 by David Sedaris (2021)

Sharon Grote, wife of Jerry, “a catcher with the New York Mets baseball team,” is a contestant on the August 22, 1967, episode of Password, winning neither game, but attracting the admiration of guest Skitch Henderson, who avows he is both a National League fan and a Mets fan. The other guest, Arlene Francis, when asked by host Alan Ludden, “What does a catcher do?” replies, “He’s in the rye.” Indeed, in a sandwich vein, Sharon Grote would go on post-1969 to appear with her family in commercials for Gulden’s Spicy Brown Mustard.

Let’s stay with “Game Shows” for a thousand.

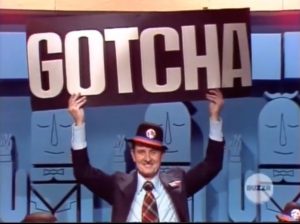

During the 1973-74 television season, the same year Bowling for Dollars with Bob Murphy premiered locally, the Sign Man, Karl Ehrhardt (and two masquerading as him), appeared as the object of guessing on the syndicated version of To Tell The Truth, pegged to the mystery man’s prominence during the 1973 World Series. Bill Cullen was the only panelist to correctly pick Ehrhardt — No. 2 — out of the crowd.

With that, we’ll hold aloft our sign that shouts HAPPY NEW YEAR! on one side and IF YOU SEE SOMETHING, SAY SOMETHING on the other. Thank you again for passing along your entertainment, media and literature scouting reports for our detailing delight.

by Greg Prince on 2 January 2022 3:56 pm The Mets turn 60 this year. They’re as old as the American League was when the Mets were first signing players in 1961, including their very first, a young feller named Bruce Fitzpatrick (Casey called him Fitzgerald) who not long ago told his story of being the original Met prospect. Bruce never made it to the big leagues, but the Mets did, and they’ve stayed, somehow.

We don’t feel a day over 1962. One is inevitably reminded, whenever a commemorative logo sees light, that as your franchise keeps on keeping on, it can’t help but grow further and further from its roots. The people who created the Mets are gone. The players who constituted the Original Mets are ever fewer. The people who made the Mets something special in the first (or tenth) place were never going to last forever, except in legend, where their place oughta be secure.

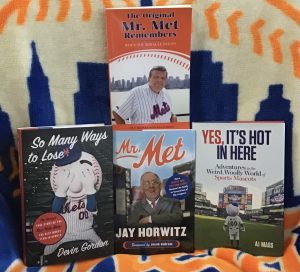

Dan Reilly recently passed away. His name may not be instantly recognizable to hardcore Mets fans the way we always knew Jane Jarvis was our organist or Karl Ehrhardt was the Sign Man, but his persona became a global phenomenon that lives on to this day. Dan was the original Mr. Met. He worked in the ticket office and handled multiple responsibilities when in 1964 he was asked to take on — or put on — one more. Please wear this head was the request from his supervisors. It was made of papier mâché, it had stitches drawn into it and it was topped by a Mets cap. Dan donned a baseball uniform and a baseball head and radiated baseball cheer. The Mets sent him out onto the field at Shea Stadium now and then. He caught on. Dan brought Mr. Met from concept (he existed first as an illustration) to a reality.

“Once I saw the reaction of everybody in the room,” Dan remembered, “I knew Mr. Met was going to be a hit with the fans.”

When it came to mascots, the Mets were ahead of the game. Mr. Met has evolved over the decades, but Dan was ahem ahead of the game. The head he wore is on permanent display in the Mets Museum at Citi Field, a magnet for snapshots like the Apple out on the Plaza. The first time I saw it up close was at a press luncheon to introduce the Amazin’ Era 25th-anniversary cassette in 1986. Even then it seemed startling to realize the Mets were as old as they were. They were the new kids in town just the other year. How were they having a significant milestone anniversary? Dan had brought his signature noggin to Jimmy Weston’s in midtown to help promote the VHS. I spotted it as it sat on a shelf in a foyer as Dan stopped to use a pay phone.

You don’t forget a sighting like that.

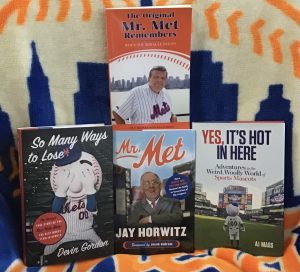

Mr. Reilly published a book some fifteen years ago, The Original Mr. Met Remembers, with Bill Curreri. It’s a wonderfully engaging memoir about life at the beginning of this thing of ours. Not just the low-tech unveiling of a mascot, but the close-knit vibe of the Mets family in the 1960s, when baseball might have been a business, but it didn’t seem all that imposing. Dan himself went in on the renting of a house in Whitestone with Ron and Cecilia Swoboda. The Swobodas, he wrote, had more room than they needed. If you knew this, you weren’t surprised that when Jay Horwitz passed along the sad news of Dan’s passing, Jay said he heard it from Ron, who’d stayed friends with Dan all these years.

Dan Reilly was first to fill the costume, but there’s a little bit of all of us in Mr. Met (and vice-versa). It’s also fitting that when Jay Horwitz succumbed to all the “you oughta write a book” suggestions he received when he ran Mets PR, he appropriately titled it Mr. Met. All of us who inadvertently take on the personality of our team have been tagged “Mr. Met” or something in a more honorifically appropriate ballpark. I’ve been “Mr. Met” to several well-wishers (and maybe ill-wishers) in my time. I’m sure you’ve been “Mr. Met” or “Mrs. Met” in your time. We take it as the ultimate compliment given that we each fill our heads like we fill our hearts with what it means to love the Mets. Dan Reilly was the first to make a suitably big thing out of it.

He wore it well.

by Greg Prince on 31 December 2021 4:24 pm The following scene occurred at Caledonian Hospital in Flatbush on this very afternoon in 1962. Or so I’ve decided 59 years after the fact.

I know ya might be in th’ mood t’ wail yer lungs out, young feller, what seein’ ya just got yerself born, but no need t’ be spooked. It’s just yer ol’ friend on a scoutin’ trip. Well, we ain’t ol’ friends yet, but we’re gonna be. It’s never too early t’ start gettin’ t’ know one another, I figger.

It’s all frank an’ earnest. I got in here with one of them keys t’ th’ city, so I’m legitimate. This key is what ya get if ya live long enough an’ maybe stay in one place without being removed from yer place of high-profile employment, which I was a couple of years ago, but not until after I won that other team a whole bundle of flags an’ titles. They showed their gratitude by dismissin’ me when I won one but not th’ other. That taught me t’ start turnin’ seventy. Keep it in mind fer when ya start gettin’ old.

This feller could talk a newborn’s ear off. I don’t mean t’ disturb yer sleep. Yer gonna need it after gettin’ born in th’ dead of winter, which is what a lotta men my age are at th’ present time, but commencin’ livin’ now is a good plan ’cuz ya get yer nappin’ in an’ not on th’ bench because we’re gonna need ya t’ start makin’ noise in April when we commence our second season. It’s gonna be yer first, which is why I come all th’ way t’ Brooklyn t’ have a chat with ya.

Ya don’t know me yet, but I wanna get t’ know ya an’ yer little chums. I guess ya don’t have any yet, but ya will. Ya need t’ come out t’ th’ Polo Grounds an’ help us as soon as ya can. I don’t think yer ready t’ take grounders, but maybe ya can get in th’ grandstand an’ start shoutin’ encouragements at my players. Between you an’ me, kid, they could use th’ help.

Here’s th’ truth, pal. We weren’t very good last year. Have they shown ya a sports page yet? We finished at th’ bottom of th’ league an’ even though th’ season ended three months ago, they’re still talkin’ about my Amazin’, Amazin’ Mets. I’ll let ya in on a secret, kid. I made up that “Amazin’” bit t’ keep th’ press’s an’ th’ public’s eyes from watchin’ my ballplayers too close. It caught on all ironical like.

Yer chart here says ya won’t be stickin’ around Brooklyn fer long. I got relocated from here myself an’ went t’ manage up in Boston. That didn’t work so good neither. Them Braves was so bad, they changed their name t’ th’ Bees. Losses found us irregardleess of identity. I didn’t get t’ be a genius until they got me some players. Life is like that, kid. Maybe ya should start writin’ this stuff down, as soon as ya can pick up a pencil.

Says on th’ chart yer gonna be takin’ up residence in Long Island. Oh, excuse me, on Long Island. Never met an infant that corrected my usage my burping at me. Well, yer in luck, pal, because we’re buildin’ a bee-YOO-tiful new ballpark out there near where yer gonna live. Ya can take one of Mr. Moses’s bright an’ shiny freeways, or maybe use th’ locomotive.

My players ain’t gonna be much better this year than last year. We’re gonna have some new players. Got this boy Hunt from Milwaukee, which used t’ be Boston. I’m gonna give him a shot when we get t’ camp. An’ this Bright feller…a very Burright feller, he’s comin’ over from th’ Los Angeleses with Darkness. Or Harkness. I can’t keep ’em straight. That’s why I didn’t want any more Bob Millers or Nelsons or whatever their name was. Th’ point is, son, my Amazin’ Mets won’t be Amazin’ fer th’ wrong reason f’rever. Mrs. Payson, th’ nice lady who owns all those horses an’ paintin’s an’ us, is preparin’ t’ fund a very generous payroll, my old friend George Weiss is hirin’ some first-class scouts an’ we’ve got that ballpark that’s gonna have escalators an’ clean restrooms when it opens an’ no pillars or posts. I’m hopin’ t’ not have t’ watch from a box seat just yet.

I used my key t’ th’ city t’ enter this here maternity ward t’ tell ya how Amazin’ it’s all gonna be an’ if yer lookin’ fer a ballclub t’ call yer own as soon as ya can talk an’ buy a ticket, ya oughta consider my Amazin’ Mets an’ make ’em yer Amazin’ Mets. I got this idea that we’re gonna be th’ Youth of America on th’ field an’ have th’ Youth of America pullin’ fer us in the new stadium, because even though we’re not world-beaters by any means yet, we’re gonna give everybody a chance, like that young Kranepool feller who ain’t as young as you but ain’t much older, an’, by th’ by, if yer thinkin’ of any other teams on th’ local baseball scene, yer not gonna be as comfortable as ya are in that blanket if ya go in another direction. That other team looks good now, but I know their farm system from th’ inside. It’s about run dry.

Look, I know ya prob’ly got a big night ahead a’ ya, bein’ born on New Year’s Eve an’ all. Fer me, every night is New Year’s Eve, except I don’t need t’ see a big droppin’ of th’ ball because my first baseman last year Mr. Throneberry dropped enough balls an’ when it came time fer a birthday party in our clubhouse, I preferred we didn’t give him no cake because he was prob’ly gonna drop that, too.

Hey, is that a smile on yer face? Look at that, yer a born Mets fan. I oughta be goin’. Just do me one favor, kid. Make yer first word “mama” or “papa”. Th’ parents in this here city are givin’ me grief how all th’ toddlers are goin’ around sayin’ “Metsie, Metsie” instead of “mama” or “papa”. They say “Metsie, Metsie”.

There’ll be plenty of time fer that. I’ll see ya at that ballpark soon enough.

by Greg Prince on 30 December 2021 4:03 pm Because The Tonight Show was taped in beautiful downtown Burbank, it didn’t seem odd that one summer night in 1979, Johnny Carson would include Tommy Lasorda while doing his Carnac the Magnificent bit. Playing to the Southern California studio audience was one of Johnny’s staples, and Chavez Ravine was certainly within driving distance. Carnac listed the Los Angeles Dodgers manager among three beleaguered figures in the news. One of the others was either Jimmy Carter or a member of the Carter administration. The other I don’t remember. After Ed McMahon repeated the trio — and Carnac gave him the side eye — the Magnificent one tore open his envelope and revealed what they all had in common:

They were three people who’d be out of a job by next year.

On the Carter front, Carnac nailed his prediction. Maybe the other person, too. But Lasorda, despite a subpar ’79, wasn’t going anywhere. And why should he? Tommy won a pennant in his first full year managing the Dodgers, in 1977. He did the same in 1978. After the aberration, already in progress, Lasorda would go on to steer the Dodgers into a one-game playoff for the NL West title in 1980, take them all the way in 1981, to the final day in 1982, another pair of NLCSes in 1983 and 1985 and, for his signature scene, a second world championship in 1988.

When Johnny Carson bowed out of The Tonight Show in 1992, Lasorda was still managing the Dodgers. He’d remain the man visibly in charge clear into 1996, officially retiring a week after The Daily Show debuted.

For 20 baseball seasons, Lasorda was himself a daily show, and it’s not like he went into syndicated reruns after stepping down as manager. Tommy Lasorda never really left the Dodgers or baseball. Even with his passing at the outset of 2021, you don’t think of him as gone. No manager alive, and hardly a handful of them less so, remains as famous.

We don’t have managers normal people have heard of anymore. We barely have managers baseball fans have heard of. Lasorda everybody had heard of. He wasn’t just baseball famous like, say, Whitey Herzog or Earl Weaver (or Buck Showalter). He was Johnny Carson famous. Famous enough for Johnny Carson to weave into his sketches. Probably as famous as Johnny Carson.

He earned it, not just by managing successfully for a long span in a large market but by making himself too big to ignore. Him and baseball. “Ambassador” is kind of a catch-all for the role Lasorda served to promote baseball, the Dodgers and, one supposes, himself. It may not be specific enough. Tommy was an entire diplomatic corps.

After managing the Dodgers, he coached the U.S. Olympic baseball team to a gold medal in 2000. He coached third base for Bobby Valentine at the 2001 All-Star Game. He starred in MLB commercials in 2006 coaching fans of teams that didn’t make the playoffs to watch the postseason anyway because it was still baseball. He was around Dodger Stadium a lot. In 2020, in failing health, he made it to the new ballpark in Arlington, home of the neutral-site World Series. If the Dodgers were on-site, and Tommy was present, there was nothing neutral about it. He wasn’t gonna miss the Dodgers winning their first world championship in 32 years, the first world championship in Dodgers history won under the guidance of somebody who wasn’t Tommy Lasorda or Tommy Lasorda’s direct predecessor Walter Alston. The first season the Dodgers won one, Tommy pitched for them. That was 1955. He never left the organization.

Alston had Lasorda on his coaching staff during the 1974 World Series. Alston didn’t call attention to himself from taking the reins in Brooklyn in 1954 forward. That wasn’t a problem for his third base coach, who was mic’d up and gave the producers of the official Fall Classic film something to amplify. They talked about him during the NBC broadcast that October. The network of Carson and Garagiola knew a star when it saw one. The following spring, in a preseason special, Tommy was featured preaching the gospel of Dodger Blue at Spring Training in Vero Beach. He bled it, the coach told the minor leaguers. When he died, he’d hoped somebody would tack a Dodgers schedule to his tombstone. Come to his gravesite, pay your respects, divine whether the Dodgers were in town, decide to catch a game.

That’s the life Tommy Lasorda extolled. That’s the life Tommy led.

Maybe you remember Tommy’s appearance in the movie Fletch. It came in a framed photo, the kind of brag-wall shot Lasorda lined his own office with. Chevy Chase, as Fletch, notices his nemesis Joe Don Baker (the police chief) with his arm around the Dodgers manager.

“Hey,” Fletch says, “you and Tommy Lasorda.”

“Yeah.”

“I hate Tommy Lasorda!” at which point Fletch punches the glass loose from the frame.

That’s sort of how I felt about Tommy Lasorda after all the Big Dodger in the Sky proselytizing had taken its toll on me, but as I figure it, we owe Tommy Lasorda at least partially for four indelible Mets.

There was, most obviously, Mike Piazza, who the Dodgers drafted as a personal favor to their manager in the 62nd round 10 years before Mike became a Met and 28 years before he became the second player to be portrayed with a Mets cap on his Hall of Fame plaque. If Lasorda isn’t pals with Vince Piazza, and Lasorda doesn’t have the sway of a Lasorda, Vince’s son goes unselected in 1988 and Mets history doesn’t have a chance to change for the better.

There was Bobby Valentine, one of his most eager protégés while Tommy L and Bobby V both worked their way through the minors, manager and player, in the late 1960s. Lasorda would be managing in the majors by 1976 and in the World Series four times; Valentine would skipper at the highest echelons, too, most notably with the 2000 National League champion Mets of Piazza.

There was also Tom Seaver, the first Met to be portrayed with a Mets cap on his Hall of Fame plaque. Lasorda heartily recommended the Dodgers draft the righty out of Southern Cal in 1965 after scouting him, but lowballed the righty so badly in terms of a bonus — $2,000 — that Seaver opted to continue his studies. “Good luck in your dental career,” Lasorda told him. A year later, the Braves would draft Seaver, there’d be a glitch in the transaction, the pick was voided, Seaver’s name went into a hat, and a lucky team from New York had its destiny called. (Dentistry would have to get by.)

And there was Sid Fernandez, the pitching prospect Lasorda signed off on trading away in the offseason following 1983, underestimating the durability of the beefy southpaw. “Everybody felt he was kind of overweight,” Lasorda explained in 1986 as El Sid was pitching his way to the All-Star team and adding however many ounces a World Series ring weighs to his frame.

We won a few because of the influence Tommy Lasorda had on the course of events. We lost a few to Lasorda’s Dodgers in the two decades he managed, especially four games of seven in the 1988 NLCS that still stings Mets fans of a certain age. But you couldn’t miss Lasorda if you were a baseball fan all those years he ambassadored for a sport he never stopped believing was the National Pastime. When he died in 2021, even if you didn’t bleed a drop of Dodger blue, you sort of missed the man whose veins flowed with the stuff.

One of the many aces Lasorda had at his disposal when he took over from Alston at the tail end of ’76 was Don Sutton. Had Sutton been more amenable to a trade proposal on the table the previous Spring Training, Lasorda would have known right away what it was like to have his team face this future Hall of Famer. M. Donald Grant was already mad at Tom Seaver for Seaver being not thrilled at being underpaid, so a swap was engineered: Tom to the Dodgers, Don to the Mets. Sutton, though, wasn’t too hot on coming to New York and, while potential sweeteners were being worked out to change the West Coast righthander’s mind, the blowback in the press back east brought the trade tumbling down. A few years later, Sutton would hit the free agent market and the Mets, under new ownership, made a run at him. Don listened, but opted to sign with Houston. We never wanted to trade Seaver, but we could’ve used a guy like Sutton.

Lasorda, Sutton and Hank Aaron were three full-fledged baseball immortals who left us in 2021. I wrote about Aaron in January. I wrote about the Hank Aaron of the feline set, Avery the Cat, in December. Through the years, when I’ve made the time, I’ve tried to acknowledge the passings of those who touched us as baseball fans or me personally. As the season and other matters distract a person’s attention, sometimes I don’t say what should be said right away. Not everybody who leaves us is a legend. Everybody leaves a little something behind.

Ed Lucas, who I met once, was a remarkable man. Blinded as a child, he worked as a baseball writer the rest of his days and authored an incredible life I recommend reading about. Jazz musician Dave Frishberg’s gift to baseball fans was “Van Lingle Mungo,” a song I swear you can’t hear enough (and I couldn’t resist attempting to pay my own brand of homage). Stephen Sondheim scored more than a few of my baseball days and nights, regardless that he was writing for the theater rather than the stadium. After my Mets won the World Series in 1986, fate doubled down and allowed me to experience my Giants winning the Super Bowl, with John Madden’s buoyant analysis intrinsic to watching them at last conquer the NFL. With Pat Summerall, Madden did every Giants playoff game to which CBS held rights from 1981 to 1993. There’s so much more to Madden’s impact on football, but having him be the voice detailing why your team is suddenly the best there is is a thrill unto itself.

Roland Hemond was a revered baseball executive. To me, he’s the White Sox GM who plucked Tom Seaver off an unprotected list on Super Bowl weekend 1984; in his defense, at least he valued obvious talent more than Tommy Lasorda did. LaMarr Hoyt won a Cy Young for the White Sox and started an All-Star Game as a Padre. To me, he’s the pitcher who took an Opening Day start while being on the same pitching staff as Tom Seaver (only three other pitchers could say that) and won one of the four decisions Dwight Gooden lost in 1985, driving in a pair of runs off Doc in the process. Richie Lewis, a reliever for seven MLB seasons, learned just how much Doc appreciated good hitter-pitching on the final day of the 1993 seasons when he surrendered a triple to Gooden, who was serving as a pinch-hitter (something Doc remembered well when I asked him about it a mere 23 years later).

Ray Fosse was an All-Star behind the plate and tremendous behind a mic….but through this Mets fan’s eyes, he’s always going to be the catcher who didn’t tag Bud Harrelson in Game Two of the 1973 World Series, even if Augie Donatelli was sadly mistaken in ruling he did (we won despite the blunder in blue). Julio Lugo, who’d bat .269 over 12 years in the big leagues, and I, who never made it out of tee ball, were briefly corporate teammates. He was a Houston Astro. I worked for a publication owned by the man who owned the Astros. The Astros let Julio go. Lugo left behind his bats. I know this because at an event my magazine staged at Minute Maid Park, I got to take batting practice with one of Julio Lugo’s abandoned bats. His name was etched into it. Despite the lumber’s pedigree, I didn’t hit .269.

In 2021, we lost nine men who at one time or another played for the New York Mets. We remembered Willard Hunter, Randy Tate and Pedro Feliciano in this space earlier this year. The other six deserve a tip of the cap as well.

Norm Sherry was a top-flight defensive catcher. He helped Sandy Koufax harness his talent in Los Angeles. He brought his wisdom to bear coaching Gary Carter in Montreal. And, let’s face it, it had to have been his defense that appealed to Casey Stengel in 1963 because Norm spent the entire season with the Mets, came to bat 161 times, and batted .136. No position player with as many as 100 plate appearances has ever recorded a lower season’s batting average as a Met. Twice Tom Seaver logged a lower BA with 100 or more PAs, but six times within those parameters Tom hit higher. It’s worth noting, however, a) Norm played with a bad back much of 1963; b) the 1963 Mets weren’t exactly bulging with better all-around catching options; and c) Sherry bounced a grounder over the head of Jimmy Wynn — playing shortstop — to bring home Rod Kanehl and beat the Colt .45s in walkoff fashion one fine July afternoon at the Polo Grounds. Norm managed all of 20 hits across a full campaign. One won one of 51 games the Mets won all year. That’s called making the most of your OPS+ of 13.

Duke Carmel was Norm Sherry’s teammate on the 1963 Mets. He began the season as Stan Musial’s teammate on the 1963 Cardinals. A midseason trade may have represented a precipitous drop in the standings, but the Mets’ second Duke — this was the year Snider was our All-Star representative — dealt the Cards a little regret about as soon as he could. In the first series in which St. Louis made their erstwhile first baseman/outfielder’s reacquaintance, they watched Carmel go deep off Bobby Shantz in the eighth inning to break a 2-2 tie and give Al Jackson all the support he needed to complete a rare Mets victory. “I’m getting a chance here,” the hero of the moment exulted afterward. Duke’s opportunity with the Mets wouldn’t last long, but his legacy still shimmers on two fronts. First, he became the first former Met to join the Yankees, which perhaps said a little something about where both franchises were heading once New York (A) deigned to acquire somebody New York (N) wasn’t hanging onto in the Rule 5 draft of 1964. Second, and of more lasting importance, he was a good man. My source? A gentleman who recently passed along a few tidbits about Carmel’s post-baseball life because “the guy deserves to not be forgotten”. Per our polite correspondent, Mr. Carmel “worked in the liquor business with an old friend and I met him a few time and he was great.” Good enough for us.

Bill Sudakis became a Met in 1972. I was excited we were getting a recent Dodger All-Star. Maybe I was conflating Bill Sudakis with Billy Grabarkewitz, the L.A. infielder Gil Hodges added to the National League squad in 1970, because this Bill had never earned such accolades. Nevertheless, I was reasonably familiar with Sudakis and welcomed him with open arms. Bill played a little first, caught a little, came off the bench to pinch-hit a little. During one of his starts, at San Diego, Bill’s two-run single in the top of the first, with Willie Mays and John Milner scoring on Sudakis’s hit to center, held up via the pitching of Gary Gentry and Tug McGraw to manufacture a 2-1 win on a starry Saturday night in July. When Sudakis reached again in the eighth, Yogi Berra pinch-ran for him with Tom Seaver.

Mike Marshall, the free-thinking reliever who won a Cy Young for the Dodgers after pitching in 106 games in 1974 (man, we sure do get or try to get a lot of ex-Dodgers), landed on the Mets after play resumed post-strike in 1981 and bolstered a bullpen that was a major reason the club hoisted itself into Second Season contention. By August of ’81, Mike had been inactive in the majors for more than a year, but at age 38 he picked up where his 188-save career left off and made a difference in Flushing. On August 27, Marshall threw a scoreless inning to keep the Mets within a run of the Astros, watched his teammates take a one-run lead, and then shut down Houston in the ninth to seal the deal at Shea, ensuring the Mets would remain barking in the NL East dogfight and raising his own record to 2-0. The Mets were surprising the National League in the wake of the strike, but Marshall wasn’t surprising Joe Torre. “Marshall is really what I wanted,” Mike’s manager said, “because he can still throw physically. And he’s got experience. That’s what we need with so many young pitchers,” an assortment that included Neil Allen, Jeff Reardon and, after rosters expanded, Jesse Orosco. “If you don’t love going out,” Marshall said of the mound where made his living for so long, “you can’t pitch.” Mike toed the rubber professionally for close to 20 years.

Dick Tidrow was another battle-scarred veteran who the Mets added to their bullpen, in 1984. His experience contrasted vividly with the rookie whose first major league start he took over for on April 7. Dwight Gooden, 19, gave the Astros a preview of what the rest of the NL would be looking at in ’84 by striking out five of them and holding them to one run in five innings. With Davey Johnson deciding young Dr. K had shown them enough, he handed the ball to the 36-year-old Tidrow, who held the lead for an inning and paved the way for Doug Sisk and Jesse Orosco to take care of the rest of that Saturday night’s business. The decision, a 3-2 Mets win, went to Dwight, his first in a career that was about five minutes from taking off for the stratosphere. Tidrow’s pitching days, however, were about at an end. The Mets released him a few weeks later, but he’d stay in baseball for decades succeeding wildly as part of San Francisco’s front office in the 2010s and receiving due credit for helping to construct the team that won three World Series titles in five years.

Phil Lombardi was a catcher in the Yankee organization who must have gotten a lot of local press in the mid-1980s, because when the Mets got him as part of the trade that sent Rafael Santana to the Bronx in December 1987 (sorry, Raffy), I was pretty pumped. We got their big-deal catching prospect? Perhaps I overestimated Lombardi’s potential once he joined the Mets’ organization, but he gave me and the Mets one big night. On June 28, 1989, in his first start as a Met, Lombardi led off the eighth inning at Olympic Stadium and crushed a Mark Langston pitch to somewhere amid the distant precincts of Quebec. I had just walked in the door from one of my first business trips as a trade magazine editor when I witnessed the blast. It was quite the welcome home.

Speaking of Canada, one of the best baseball expatriates the Mets ever picked up from the Great White North was former Blue Jays batting champion John Olerud. John had raked for Toronto until he didn’t. When he came to New York in 1997, he found his stroke again, with significant assistance from hitting coach Tom Robson. Bobby Valentine’s lieutenant was someone Olerud thanked mightily for reviving his sweet swing. “He was the perfect hitting coach,” John once reflected. “He helped save my career. We came from the same philosophical school of hitting — hit the ball where it’s pitched — and we really hit it off.”

One of my coaches, you might say, was a journalism professor named George Meyer (not to be confused with the Simpsons writer of the same name). Unlike Olerud and Robson, I had no deep personal relationship with Meyer. I had him for one semester of News Editing my junior year in college. By the time I was a senior, I’m convinced he would have no idea who I was if you mentioned my name to him. But damned if, as the years have gone by, I haven’t continually found myself remembering something specific Meyer taught in class and applying it to something I was writing, something I was editing or something I was thinking. I had several instructors in the Mass Communications department at the University of South Florida. George was in the distinct minority of those who left an impression I feel to this day (I’m holding up two fingers). He was also a mensch when I realized I’d totally misinterpreted an assignment as I was handing it in and asked him if I could do it over now that I figured out what he was looking for. “Sure,” he said, rescuing me from my own unforced error. More prepared for any eventuality than his addled student, George Meyer even wrote his own obituary in advance. There’s a person who understood an assignment.

The year I took News Editing was the year I hung out with John Pazman. John, you might say, is here on a do-over. My close friend from my dorm my junior year died in 2014, but I didn’t learn about his passing until a little curious Googling in 2021. Somehow the subject of clove cigarettes came up — John is the only person I knew to have smoked them — and I got to thinking about him. I’m sorry to learn he’s been gone all this time. I’m delighted I got to know him as I did when I did. We were down-the-hall neighbors, each of us with roommates who ghosted, so we visited each other frequently for company. He was kind of a surfer type, though I can’t recall if he actually bothered to surf. Maybe he just liked soaking up the rays (there was a lot of that going on at a college not terribly far from Clearwater Beach). I don’t necessarily remember much we had in common other than a fondness for Steely Dan and disdain for certain residents of our floor. Despite being from Pittsburgh, he had no interest in the Pirates, though the Steelers were sort of cool, he decided, because when they’d won all those Super Bowls, he got to go downtown and party.

John moved out of the dorm the following fall, and we remained friendly when I was a senior, but we were already drifting apart. The reason I’m moved to mention him here is the letter I received from him in the waning weeks of 1986, more than a year-and-a-half from the last time I’d heard from him. The line he dropped was to congratulate me on the Mets having won the World Series. He didn’t go in for baseball, but my room with all its Metsaphernaila had stuck in his mind, and he figured I must be very happy and he wanted me to know he was very happy for me.

One time our dorm had to clear out into the parking lot because of a false alarm, John took note of some scaffolding on the side of our high-rise building. Hey, he mused, we should get up in that thing and pull ourselves back up to our floor — everybody will see us and we’d be the coolest people here. Then he thought about it and decided, “Nah. We’re already the coolest people here.”

One of us was, anyway.

Conversely, there wasn’t much cool about Todd Feltman, which is what made him such a warm character to be around. I met Todd on the first day of fourth grade. Our teacher told us to introduce ourselves to somebody sitting near us and get to know each other. Todd and I shook hands and exchanged vital information: I was a Mets fan, he was a Yankees fan. This was 1972, when Yankees fans on Long Island were in short supply, so I assumed he wasn’t putting on airs. Despite our core difference, we hit it off and stayed, in some form or fashion, hit off for the next nine years of public school, then friends from afar while we were in college, then in touch sporadically for a pretty good while thereafter. Upon learning from an old mutual friend in September that Todd died this past spring, I found myself mentally opening my “Feltman, Todd” file. The memories filled a warehouse.

When I say Todd wasn’t cool, I don’t mean he wasn’t capable of wearing a stylish shirt. He just put himself out there with limited self-awareness. No pretenses. He didn’t care how he came across so much as he cared that you felt good about yourself. I mentioned we shook hands in fourth grade. We shook hands a lot. Todd was one of those gregarious guys who’d shake your hand every day if you saw him every day. When we were older, he’d want us, with our significant others, to meet up so we could “cocktail”. It was his approach and it was genuine. He was delighted to see you, to ask how you were doing, to listen to the answer. It didn’t matter that your cause wasn’t his. He wanted your cause to succeed for you. And yes, I’m talking about the Mets, but it applies to everything else. I’ll stick with the Mets here, though.

Monday afternoon, September 20, 1976. Eighth grade. Todd was coming over after school. On the way to my house, we stopped by the Lido Deli to pick up a snack. I don’t remember what I ordered. He asked the counterman for a seltzer and a sour tomato. He was 14 years old and ordering like his grandfather would. But it’s what he wanted, so why not? We take the food and drink back to my house, sit down at the kitchen table and I turn on the radio. The Mets are finishing up a series with the Pirates. I don’t know that every 14-year-old would have planned an afterschool get-together around the final innings of a Monday matinee, but it’s what I wanted, so why not? Todd, whose team was soon to go to the playoffs for the first time in his sentient baseball life, may not have been thinking this was the most fun activity, but he went along with it and he joined me in rooting for the Mets. It wasn’t a big game for them. It was a big game for the Pirates, who were chasing the Phillies, so the Mets were at least playing spoiler if they could come from behind.

With two out in the bottom of the ninth, trailing by one, John Milner singles off Kent Tekulve, Leo Foster runs for Milner and September callup Lee Mazzilli gives Tekulve’s final pitch the ride of its life, taking it over the right field wall for the 5-4 Mets win, or a win that I’m still talking about 45 years later. Todd and I celebrated. The high-five had yet to be widely disseminated. We probably shook hands.

Todd was living out of town when Stephanie and I got married fifteen years later, which is now thirty years ago, so he sent his parents in his place. He was back in the area when he got married five years after that, in 1996. We went. He and I not only shook hands a lot, but embraced. “We’ve got to get together more often,” he told me with utmost sincerity, the only sincerity in his portfolio. “I’m serious.”

We never saw each other again. I looked for him on Facebook, but remembered he was inevitably the kid who didn’t know to order the sixth-grade autograph book or that today was the day to show up for the yearbook photo. No, I never found him on social media. I didn’t need to. My mental file is blessedly crammed with silly, sincere and authentic interactions with Todd Feltman that spanned nearly a quarter-century and have lived with me for another quarter-century since.

I’ve still never “cocktailed” with anybody. Or seen anybody else order a seltzer and sour tomato.

by Greg Prince on 29 December 2021 1:27 pm The last two instances of the Baseball Equinox, marking the spot when we sit equidistant between the final out of last season and the scheduled first pitch of next season, were rendered inoperative in retrospect once COVID had its way with them. The opening of the entire 2020 baseball season was pushed back to July and the Mets had their first three games of 2021 postponed when too many Nationals tested positive. We can do the math, but we can’t control the science.

But, if you choose to believe that lockouts will be settled and variants will be tamed, this year’s Baseball Equinox arrives in our midst on Saturday, January 1, 2022, at 3:28:30 AM Eastern Standard Time. If you are in the greater New York Metropolitan Area, you’re forgiven in advance for possibly sleeping through it. But maybe you’re the type who saves it all up for New Year’s Eve and you’ll be partying deep into the morning. Or, if you’re like me, you’ll be digging on the WLNY 10/55 Odd Couple marathon (Felix and Oscar will be finishing their stint as mismatched hospital roommates just before 3:30 AM).

If you’re in another time zone in the Continental U.S., you stand a better chance of still being up when the enticing promise of the 2022 season becomes temporally closer than the lingering disappointment of the one from 2021. And if you’re in Hawaii —perhaps hanging with Benny Agbayani or Sid Fernandez as one imagines all Hawaiian Mets fans might — by all means, make the Equinox a part of your extended countdown to midnight.

Offer good in all fifty states and the District of Columbia.

by Greg Prince on 28 December 2021 1:34 pm Later this week I’ll be along with the Tenth Annual awarding of the Oscar’s Caps, recognizing the year in Mets Pop Culture. But one Mets pop culture sighting in particular was too big to confine to a sentence or paragraph amid a catalogue of other, albeit worthy sightings (all Mets pop culture sightings are worthy), so we’re going to dwell on it by itself here for a spell. And we’re going to start, as the Mets did in 681 regular-season games during the 1980s, by leading off with Mookie Wilson.

Mookie Wilson has never seen Do The Right Thing, at least he hadn’t when the Los Angeles Times asked him about it for a story regarding Mookie Blaylock joining the Dodgers. Most every high-profile Mookie came up, including the Mookie director/star Spike Lee played in his landmark 1989 film. “I’m not a moviegoer,” Wilson told LZ Granderson. “I heard people talk about it and I know it’s Spike Lee and he’s from New York, but I haven’t seen it yet. I have no idea if he named the character after me, but it sure seems that way, doesn’t it? I’m sure there were Mookies before me, but I didn’t know of any…definitely not one who was doing the things I was doing when I was playing. It’s just one of those funny timing things, I guess.”

Can you ever have too many Mookies? Funny timing, says Mookie? The L.A. Times article appeared on February 11, 2020, five days after I met the Mets fan who a) would soon be spending a decent amount of time himself speaking with Mookie Wilson and b) when asked if he has a particular favorite Metsian pop culture moment, replied, “I love that Spike Lee’s character was named Mookie.”

Timing says the Mookie who delivered pizza in Bed-Stuy while wearing Jackie Robinson’s 42 and called out hypocrisy when it stared him in the face in the summer of 1989 was not only trying to do the right thing, but he was in the right place at the right time. Mookie Wilson was in his tenth and final season as a New York Met. The New York Mets were in their sixth of seven seasons as a National League East powerhouse. The Mets of the era were a totem Spike latched onto while making or promoting movies during this period — TV appearances, trailers, dialogue or background in at least three features. Meanwhile, the nearby New Jersey Nets had just drafted, in June of ’89, Mookie Blaylock, pretty much the second (or third, depending on when you went to see the movie if you were a moviegoer) Mookie most folks had heard of. Wilson would be traded to Toronto by August and propel the Blue Jays to the playoffs, making Mookie an icon in two nations, but he’d retire from baseball in 1991 and inevitably fade a bit from the collective consciousness outside of Flushing.

Our Mookie was no longer the Mookie who leapt universally to mind when you mentioned a Mookie as the 1990s rolled on and the 21st century was born. He was for us, of course, but Blaylock would have his day in the sun as a 13-year NBA guard (and brief moniker for Pearl Jam before Pearl Jam was Pearl Jam); Lee’s film with its lead character maintained enormous cultural staying power; and then, in 2014, came All-Star-to-be Mookie Betts, and all wagers were off as to whom a later generation would point as the Mookie of record. When he was a Red Sox rookie, the newest Mookie — Markus by birth — explained his parents started calling him by that nickname from watching the Mookie who played basketball, not baseball.

But the guy I met in person on February 6, 2020, a New York-bred movie director in his own right, has done his best to keep the original Mookie atop the Mookie marquee — even if William Hayward Wilson wasn’t necessarily the lead character in his screen gem.

Nick Davis is the auteur behind Once Upon A Time in Queens, the four-part film documenting the ascent and ascendancy of the 1986 New York Mets, how they rose from the ashes of the lowest point in franchise history nine years prior to reach the heights of the baseball world for a moment that both ended too soon and lasts to this day. Soaring in approximate tandem with the ballclub was the city it represented. When we met New York at the outset of Davis’s story as it aired on ESPN as part of the 30 for 30 series in September, it was still smoldering from the great blackout of the night before, July 13, 1977, a Wednesday that clocked in exactly four weeks after June 15, 1977, the aforementioned franchise low point for the Mets.

New York was in rough shape that summer. The Mets’ shape was rougher. Tom Seaver was traded. Dave Kingman was traded. Last place was held on a long-term lease. And rooting for the Mets, despite M. Donald Grant doing the wrong thing, were kids like Nick Davis in Manhattan and me on Long Island. We didn’t know each other then, but we might as well have been each other. Every Mets fan of a certain age in the late 1970s was, when it came to the object of our baseball affections, determined to do the unpopular thing. We were all one. We were all alone. We couldn’t imagine there were any longer many of us constituting us.

We’d rooted for the Mets before Seaver was traded. We’d keep rooting for the Mets after Seaver was traded. We’d hope for the best. The hoping was laced with waiting, because there was a ton of waiting to be done. The Mets were down and were not getting up in 1977. Or 1978. Or 1979. A glint of light shone through in 1980 — the franchise was sold, a Magical slogan fleetingly resonated — but prone remained the default position for the Mets. As it did in 1981. And 1982. And well into 1983. Every one of those years lasted no more than 366 days and every one of its baseball seasons no more than 163 games (I’m a stickler for counting ties), but if you were Nick or me or perhaps you, every minute when the Mets were dismal and we were sure there were hardly any other Mets fans besides our hardy handful, lasted an eternity.

Then eternity turned around. You say “1983” differently from the years that immediately preceded it, last place or not. Then you say “1984” and “1985” and it’s an entirely new ballgame. Which gets us to 1986 and the rest of the story Nick had in his bones and was ready to cinematically spill by 2020.

Which is what got Nick and me together face-to-face for the first time that February. We had been in touch via e-mail and phone in the months prior as Nick, a faithful FAFIF reader for a few years to that point, let me in on this project he was working on about the 1986 Mets and asked if I would I like to be, in Ken Burns’ The Civil War terms, his documentary’s Shelby Foote, its voice of historical perspective.

He had me at “1986”.