The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 12 June 2020 5:47 pm Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

But there ain’t no Coupe de Ville

Hiding at the bottom of a Cracker Jack box

—Meat Loaf

If it feels like it’s been a while since the last official Mets game, it has been. As of Sunday, it will be the longest it’s ever been. June 14, 2020, will mark 259 days since September 29, 2019, last season’s Closing Day. That tops by one the 258-day void between August 11, 1994, the last game before that year’s players’ strike, and April 26, 1995, Opening Night of the next year at Coors Field. That arid spell stretched on forever, and we’re about to surpass forever.

So for reasons beyond the sport’s control and maybe a few within its negotiating grasp, we’ve involuntarily tried a baseball-less season. It doesn’t seem preferable to anything. But is it preferable the least favorite baseball season of your life?

No.

Of course not.

Are you crazy?

But isn’t not having any baseball somehow better than being subject to terrible baseball, specifically terrible Mets baseball made worse by the subtraction of the best Met ever?

Let me think about that for a sec…

Still no. You’re still crazy. Believe me, lacking any recent games to contemplate, I’ve thought it through thoroughly.

I’ve personally experienced 51 Mets seasons, from 1969 through 2019. I recently sat down and attempted to formalize some chronic late-night noodling, daring to list, from 1 to 51, my personal favorite Met seasons; or my least- to most-favorite Met seasons from 51 to 1. (This differs from dispassionately discerning and ranking The Best Met Seasons of All-Time, which I took my shot at here.) I’ve known what’s bundled at the top for some time. The bottom cluster, though, I had to dwell on, even though you wouldn’t necessarily want to dwell in it. You go down there, you better just beware of the bad, bad season you’ll call the one you liked least.

Yet you still liked it. I mean, no, you didn’t like like it, but there was baseball. There were occasional wins. There were intermittent great plays. There were players you looked forward to seeing play. There was, if you were lucky, a player you had no idea was going to play and you grew excited once you realized he was going to play every day.

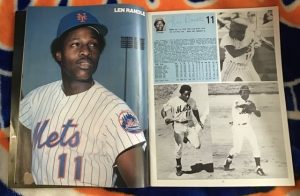

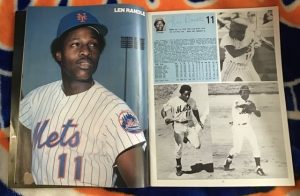

In 1977, my least favorite Mets season among the 51 I’ve truly inhabited, that player was Lenny Randle. He couldn’t save ’77, but he could make it go down incrementally smoother.

Players like Lenny Randle are why they revise editions of the yearbook — or used to. You want to examine his picture, pore over his stats, absorb his biographical nuggets. You want to root for Lenny and the Mets, sometimes in that exact order. You want to wrap yourself in the recurring surprise of the presence of someone who wasn’t there when the season began and now you can’t imagine your ballclub continuing without him. You want all the Lenny Randle you can get.

We got Randle by the bushel in 1977. It was one of the two elements of my least favorite season I remember most fondly. One was the first trip I took to Shea Stadium without adult supervision, an LIRR jaunt to see Lenny and the Mets take on (and lose to) the St. Louis Cardinals. That’s an unabashedly fond memory for a fourteen-year-old. Lenny coming aboard at the end of April and flourishing in the months ahead is the other. That’s a fond memory for a Mets fan of any age.

Otherwise, 1977 is the season the Mets fell through the floor of the National League East and traded Tom Seaver while most everybody I knew suddenly decided to switch their local baseball allegiances. No wonder it’s my least favorite season. What was wrong with it is easy enough to divine and despair. Let me evade the tag of “least” as best I can and stick to the favorite part of my least favorite season. Let me remember the revelation that was Lenny Randle of the New York Mets.

When the Mets gathered in St. Petersburg for Spring Training, Lenny Randle was not with them. He was a Texas Ranger, across the Florida peninsula in Pompano Beach. Randle had been a Ranger since before there were Texas Rangers, back to 1971 when the Rangers were the Washington Senators. In 1974, Lenny was one of the Rangers who shocked baseball, rising from the Seasons in Hell depths of the AL West to challenge the Oakland A’s for divisional supremacy. Texas fell short but behind Manager of the Year Billy Martin, MVP Jeff Burroughs, Cy Young runner-up Ferguson Jenkins and Rookie of the Year Mike Hargrove they excited a nation of baseball fans. They certainly got an eleven-year-old on Long Island stoked about their upset chances. Randle, mostly shifting between second and third base and switch-hitting .302, became one of my vaguely favorite American Leaguers from a distance.

In the Spring of ’77, I had no idea how close Randle would soon be getting to where I lived and rooted. The Rangers were maneuvering legacy prospect Bump Wills to second and Lenny to the bench. Tensions couldn’t help but be a little high between the incumbent infielder and his manager, Frank Lucchesi. Randle indicated he didn’t want to be a Ranger reserve. Lucchesi grumbled, “I’m sick and tired of these punks saying, ‘Play me or trade me.’ Let them go find another job.”

That’s what Randle did, indirectly, taking harsh exception to being called one of those things you don’t call a grown man in your employ (management training has come a long way over four decades). While the Rangers were in Orlando visiting the Twins, Lenny lost his temper and started communicating with his fists. Lucchesi took a punch under the right eye, with a fractured cheekbone to show for the altercation. It didn’t play as much of a fight in the public imagination. Randle was a 28-year-old athlete. Lucchesi’s age at the time of the incident was reported as 49 back when 49 seemed incredibly old. The manager went to the hospital. The player went on suspension, with his reputation severely bruised.

That was in late March. In late April, it was announced that somebody had made a deal to take the potential social leper off Texas’s hands: the Mets, of all teams. I say “of all teams,” because the Mets seemed like the last team in the world to take a flier on a presumed malcontent. M. Donald Grant didn’t like the players who talked back. Now the Mets were welcoming one who hit back? Somehow, the Mets managed to be sort of progressive in this instant, looking past the ugly episode and assuring themselves that Randle was still the person who, prior to Lucchesi labeling him a punk, had been “probably the most popular Ranger among his teammates,” according to Sports Illustrated.

“Every report on him from scouts and from people who knew him at Arizona State,” Mets GM Joe McDonald told the Times, “says that he is a gentleman and the incident in Florida was uncharacteristic.”

Still, it was uncharacteristic for the Mets of 1977 to take questionable-PR chances or attempt to improve their ballclub. They hadn’t made any moves in the offseason and the stagnation showed. Perhaps McDonald was inspired by a fairly recent episode of M*A*S*H in which Hawkeye and B.J. plot with a North Korean prisoner who happens to be an excellent English-speaking surgeon to create a new identity for the captured doctor, presenting him as One Of Ours so he can help heal the wounded, which is the whole idea of medicine in wartime, as the series mentioned once or twice. Not yet wise to the elaborate scheme, Col. Potter is surprised to find he’s in receipt of new, eminently qualified personnel.

“You know, Radar,” the 4077th’s commanding officer remarks to his company clerk, “this is the first time I Corps has sent us help without us screaming about it.”

That’s how I felt. It never occurred to me the Mets would go after Randle. After the first winter of free agency came and went with the Mets leaving all pursuable talent essentially unbothered, it never occurred to me the Mets would go after anybody. Yet here Lenny Randle was, in San Diego, coming in for defense in the eighth inning, replacing John Milner in left (Randle played every position but first base and pitcher during his twelve-year big league tenure). I can honestly say I’ll never forget that Saturday night of April 30, 1977.

I’d love to tell you it’s solely because Lenny Randle made his Mets debut in the 4-1 win that raised Tom Seaver’s record to 4-0, but in the interest of full disclosure that nobody asked for, it’s because I stopped up the downstairs toilet while my parents were out. We didn’t own a plunger, so I had no idea what to do except finish watching the Mets and the Padres, and work on crafting a delicate explanation for why the bathroom my parents relied on was shall we say out of order.

My explanation was not accepted any better than any of the words Lucchesi expressed regarding Randle in Florida, but we borrowed a neighbor’s plunger; bought one the next day for future emergencies; had a long discussion about how much paper to not use; and decided it would be best to confine my business to the upstairs bathroom for the rest of eternity.

Talk about fear in flushing.

Life went on. Randle went on. The first day of May found Lenny starting at second base, collecting three hits that included a triple, stealing home and sparking the Mets to completion of a three-game sweep of San Diego. Frazier was no Lucchesi when it came to managing the former Arizona State Sun Devil. “I wish I had four or five more just like him,” Cobra Joe said after a splash of exposure to his newest player.

We definitely could’ve used more Lenny Randles. The creeping malaise that was the 1977 Mets was impervious to the charms and impact of a lone burst of talent and personality, no matter how engaging. The wins against the Padres were an aberration. The Mets were headed for the basement, and their biggest stars — Seaver and Dave Kingman — were headed out of town. So was Frazier. On the last day of May, Joe was the ex-manager of the Mets. The new skipper was another Joe — Joe Torre, promoted from the active roster. The first move the player-manager made was to install Randle, who’d been mostly filling in at second while occasionally bouncing into the outfield, as his everyday third baseman and leadoff hitter. Torre had obviously kept his eyes open en route to taking Frazier’s job. Randle had batted .341 across his first month as a Met.

To thank Torre for the vote of confidence, Lenny singled, doubled, walked twice and scored twice on May 31, elevating his average to .352. The Mets were starting a hot streak (it wouldn’t last), Torre was starting a managerial career (it would take him to the Hall of Fame) and Randle was starting daily and becoming the undisputed best thing about the 1977 Mets. Once Seaver and Kingman were traded on June 15, there wasn’t much competition, but Lenny likely would’ve earned the distinction on his own.

Lenny is why they revised yearbooks. The hitting wouldn’t swelter forever, but the average stayed above .300 for the rest of the season. The running threw caution to the swirling Shea wind, resulting in probably too many caught stealings but also a new club record of 33 bags swiped. The fielding at third was fine enough so that the 1978 Mets Yearbook wasn’t engaging in hype when, after ticking off his string of offensive accomplishments, it praised Randle for having given the Mets their “steadiest play ever at that position”.

Beyond the production, Lenny Randle was a fun guy to have around, not a small factor in the most unfun non-pandemic season imaginable. Emerging from the stormy circumstances that the revised edition of the 1977 yearbook did its best to downplay (“his much publicized run-in with Rangers’ manager Frank Lucchesi in ’77 spring training made him available to Mets”), Gentleman Len seemed genuinely happy to be here when hardly anybody else did. “It takes a certain player to be able to play in New York,” Lenny would assess in retirement for ubiquitous oral historian Peter Golenbock, and he was clearly one of them. He lit up every Kiner’s Korner he guested on in a year when Mets were sorely lacking for stars of the game. Lenny had received good advice from one of his coaches when it came to the postgame show.

“Willie Mays would tell me to go talk to Kiner,” Randle remembered for the book Down on the Korner. “He was a legend to me.”

For one season, Lenny was a legend of perhaps not quite Kiner-Mays proportions, but in 1977, especially after June 15, you learned to not expect too much. On Saturday afternoon, July 9, a day devoted to playing stickball with/against a frenemy of mine (he’d committed the traitorous sin of quitting on the Mets and taking up with that other New York team, thus revealing a disturbing paucity of character), a transistor radio kept us apprised of what the Mets and the Expos were up to at Shea. They were up to extra innings. Extra, extra innings. In the seventeenth, with Lee Mazzilli on first and two out, Randle crushed a Will McEnaney pitch to end the game in the Mets’ favor, 7-5. I don’t remember how the stickball turned out, but as far as I’m concerned, I won the day.

And that wasn’t even Randle’s most memorable Met moment of the week. That would come at Shea on Wednesday night, July 13, as Lenny batted versus the Cubs’ Ray Burris in the bottom of the sixth with the home team trailing, 2-1. That’s when things went dark. Literally.

“I thought to myself, ‘This is my last at-bat. God is coming to get me,” the third baseman said of the situation that enveloped him. Randle’s mortality wasn’t really in quite so dire a shape. It was just a blackout of all five boroughs that lasted until the next day. That’s all. The Mets-Cubs game was suspended until mid-September, when Randle completed his plate appearance by grounding to short. It took two months to play the full nine innings, but the Mets lost. Usually it took only two hours.

The Mets’ darkest season was Randle’s brightest. The next year, Lenny was the Opening Day starting third baseman, carrying expectations. Perhaps they burdened him, for Randle in his second Met year couldn’t hold a candle to Randle in his first. Lenny ended April batting .155 and never broke .250. His stolen base total plunged and he was getting thrown out almost as often as he was being called safe. Before Spring Training ’79 was over, so was Randle’s Mets career, with the shining star of ’77 (and his salary) released altogether and replaced at the hot corner by Richie Hebner. The surly erstwhile Phillie seemed determined to prove the new former Met’s theory that it takes a certain player to be able to play in New York. Hebner wasn’t that certain player, but let’s call that another story for another least favorite season.

Randle didn’t last very long at Shea, but he surely put the favorite in “least favorite,” which is a most valuable asset for any fan who would never think to shop his loyalty around the Metropolitan Area. We don’t remember that his ship sank in 1978. We remember that he made us feel as if we were riding the high seas with him every time he batted in 1977. Knowing Lenny as we did, little wonder that in 2015 an MLB Network documentary celebrated this character who once endeavored to blow a fair ball foul as “the most interesting man in baseball”. And little wonder that he became a Mets fantasy camp coaching mainstay. As FAFIF correspondent Jeff Hysen reported from Port St. Lucie in January of 2009, “Lenny Randle stressed the importance of not colliding with anybody — he said that when a fly ball was hit his way, he would yell ‘get the [frig] out of the way!’ It was very windy and tough to catch the flies. After I did, Randle chest bumped me.”

Just as a gentleman does.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

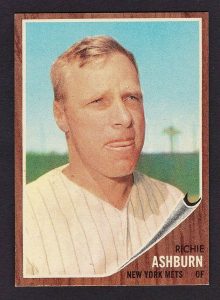

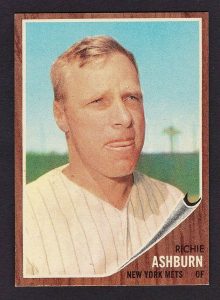

1962: Richie Ashburn

1964: Rod Kanehl

1969: Donn Clendenon

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1982: Rusty Staub

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1994: Rico Brogna

2000: Melvin Mora

2002: Al Leiter

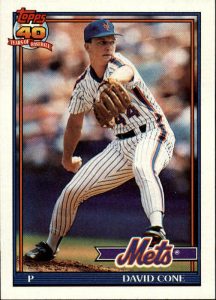

2003: David Cone

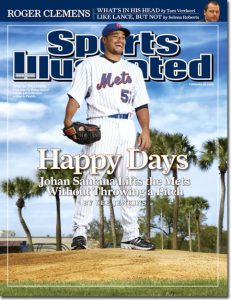

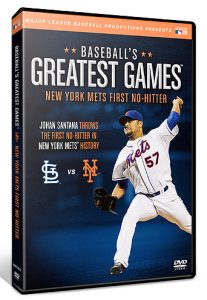

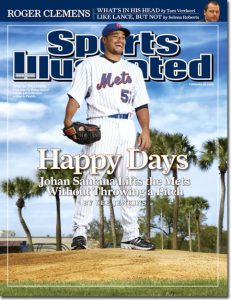

2008: Johan Santana

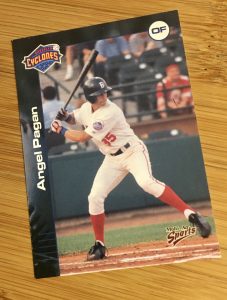

2009: Angel Pagan

2012: R.A. Dickey

by Greg Prince on 11 June 2020 4:44 am We are a few days from the 40th anniversary of the most Magical home run in Mets history — the Steve Henderson game-winner of June 14, 1980 — and should you care to treat yourself to a commemorative viewing, you can transport yourself to the evening in question and take in extended highlights of the Saturday night Shea Stadium rally to end all Saturday night Shea Stadium rallies (at least until the Saturday night Shea Stadium rally of October 25, 1986). Go to the 51:00 mark to experience it unfolding. Stay past the 52:00 mark, after Henderson’s opposite-field home run flies into the Mets’ bullpen. Watch Hendu’s teammates gather around him in jubilation; pound him on the back; lift him in the air; follow HENDERSON 5 to the dugout. You can identify the 1980 Mets in mid-giddiness by name and number.

YOUNGBLOOD 18

FLYNN 23

MORENO 4

TREVIÑO 29

STEARNS 12

TAVERAS 11

CAREDNAL 6

MAZZILLI 16

MADDOX 21

And right in the middle of the World Series-level celebrating those Magic is Back Mets absolutely earned, 15. No name, just 15. The lack of complete identification was sort of understandable in that the player who wore No. 15 was relatively new to Shea, though you’d figure there’d have been ample time to properly outfit a guy who’d been acquired a week earlier and who’d been playing for the team since Wednesday the 11th. Maybe there was a no-return policy on jerseys once you stitched a letter across their backs and the Mets just wanted to be sure their newcomer was a keeper.

No. 15 would soon make a name for himself in Flushing. Make no mistake about it, though. We who hung on every move the Mets made knew who No. 15 was. His presence in a Mets uniform in June 1980 was a cause for celebration unto itself. The irony in his name not being ironed on was that he was probably the biggest name the Mets had the moment he arrived in Flushing.

We got Claudell Washington. Eventually his uniform top fully reflected his affiliation with us, and ours with him. We might not have realized we’d be united in common cause for just that one summer, but, as Carol Burnett liked to sing every Saturday night, I’m so glad we had that time together.

Claudell looked pretty pumped about it, too. Watch the video and focus on the nameless wonder. He is as elated as any Met this side of John Stearns that the Mets have come back from six runs down to pull out a 7-6 victory over the Giants. You can understand why Stearns was thrilled. Dude had been trying to push the Mets into the end zone since 1975. Washington? As noted, he’d been a Met for a matter of days. Yet he was susceptible to Mets Magic. Hell, he was largely responsible for this particular megadose of it.

We know June 14, 1980, as the Steve Henderson Game, but it was also something of a Welcome Wagon fiesta for Washington. Frank Cashen traded minor league pitcher Jesse Anderson to the White Sox for Claudell on June 7 — the first exchange the GM engineered at the outset of his long, arduous post-de Roulet rebuild of New York National League baseball. The Mets were scratching and clawing toward provisional respectability. They needed another set of fingernails, preferably wrapped around a bat capable of driving in some runs. The day Cashen landed Washington, almost two months into the season, the Mets had gone deep exactly eleven times.

That is not a typo.

Washington wasn’t a slugger, per se, but he could hit a few homers, totaling 13 the year before with Chicago. The outfielder had been making things happen since 1974, when he was only 19, yet an integral part of the world champion A’s. Few teenagers play in the majors. How many bolster a dynasty already in progress? A year later, he’d sock 10 home runs, steal 40 bases, bat .308 and make the AL All-Star squad. When he got to the Mets, Washington was decorated, venerated, and still only 25. This was more than lefty punch combined with dangerous speed. This was a bona fide stud baseball player, the kind we weren’t used to having in our ranks. For Mets fans of the era, this was a genuine morale boost. We must be sort of serious about competing in this division. We just went out and got Claudell Washington.

On June 14, Washington, who’d made an impressive catch at the wall in right in the early innings, drove in the first Met run of the night in the sixth with a sacrifice fly. In the eighth, his right-side grounder set up the run that reduced the home team deficit to 6-2. And in the ninth, with The Magic bubbling up from the Met cauldron, it was Claudell who singled up the middle with two outs to score Lee Mazzilli and send Frank Taveras to second, making the score 6-4 and things very interesting. Two were on base as Henderson strode to the plate as the potential winning run. The potential tying run was Washington on first. The potential became reality four pitches into Henderson’s battle with San Francisco reliever Allen Ripley.

No. 15 touched home plate to make it 6-6 moments before Henderson officially put the comeback in the books. Steve was the obvious walkoff hero. Claudell was an unnamed co-conspirator. He wouldn’t be unsung in Met success for long. The following weekend at Dodger Stadium, he and we got a Claudell Washington Game for the ages. Four hits and five RBIs in a 9-6 victory to bust up a losing streak. Three of those hits were home runs. Magical finishes notwithstanding, Mets didn’t hit home runs in 1980. They dwelled in a dinger desert. As for doing it in triplicate, Jim Hickman had hit three home runs in game in 1965; Dave Kingman hit three home runs in a game (also at Dodger Stadium) in 1976; and Washington became only the third Met ever to do it, do it and do it once more. Of course he was an old hand at it, having whacked three homers in a game for the White Sox in 1979. To that point, three players had gone deep three times in one game in each league: Babe Ruth, Johnny Mize and Claudell Washington.

“If the game had gone on much longer,” first baseman Mike Jorgensen half-joshed regarding his normally power-deficient outfit, “Washington would be leading the club in homers.” Great self-deprecating line, except at the time, Jorgy led the Mets with five round-trippers. By the next afternoon at Wrigley, when Claudell reintroduced himself to the Windy City by belting one over the ivy, it didn’t seem like such a joke.

By season’s end, Washington would, in fact, be the Mets’ second-leading home run hitter with ten, six behind Mazzilli’s sixteen; the Mets slugged 61 combined. Considering he played in only 79 games, it represented a pretty powerful output. Combined with his notching 17 steals and 42 ribbies, Claudell had made a good case for continuing his association with the Mets. Cashen was able to grab him in June on the last year of a contract. Signing him to a new deal in the offseason made plenty of sense for a Mets club yearning to rely on something more tangible than Magic. Alas, Ted Turner made Washington — still only 26 as of next season’s Opening Day — an offer he couldn’t refuse. Claudell was off to Atlanta.

As enticing a proposition as Claudell Washington appeared for the long-term, especially the day he blasted those three home runs in L.A., the Mets had already secured their right fielder of the future in June of 1980. Four days before the Washington trade, the Mets drafted Darryl Strawberry — a Los Angeles product, it so happened — No. 1 in the nation. Darryl, then 18, wouldn’t be able to hit home runs for the Mets immediately, but he’d make it to Shea soon enough, and he’d give us something (including, in 1985, the fourth three-homer game in Mets history) to look forward to. Young outfield prospects will get your motor running like prospects at no other position. A supremely confident Southern California-bred center fielder named Pete Crow-Armstrong, whom the Mets selected in the first round of the abbreviated 2020 MLB draft Wednesday night, will do that, assuming he signs and assuming professional baseball gets its ass in gear again one of these days. Lefty-swinging Crow-Armstrong is 18. He’s presumably a ways away from Citi Field, but years tend to circle the bases at a brisk pace. We just drafted somebody born in 2002, for cryin’ out loud. That’s even crazier than realizing our summer with Claudell Washington took place forty years ago.

Washington played for the Braves until 1986. He’d see action with seven teams in all, plying his craft clear into 1990, by which time he was in his seventeenth major league season…and was still only 36. Almost half of his life had been spent as a big leaguer by then. Just a little of it was as No. 15 on the Mets. Nevertheless, when I learned on Wednesday that Claudell Washington had died at only 65, hours before we started thinking about a future with Pete Crow-Armstrong, I was back in 1980 with the Magic. I was thinking about the guy whose name was missing amidst the home plate Hendu hug, the guy who’d been a Met for about a minute yet greeted Steve Henderson like a true brother in arms.

“Claudell played for 7 teams,” Washington’s fellow ’80s Brave Dale Murphy tweeted in the wake of the sad news. “Guarantee he was a teammate/clubhouse favorite on each team he played for.”

I can see that. I saw it in 1980.

by Jason Fry on 9 June 2020 3:45 pm Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

Championship teams aren’t meant to last. When the New York Mets returned to Shea in April 1987 to defend their second title, supersub Kevin Mitchell was a Padre, World Series MVP Ray Knight was an Oriole, reliable pinch-hitter Danny Heep was a Dodger, oft-forgotten reliever Randy Niemann was a Twin, and backup catcher Ed Hearn was a Royal. Twenty-four Mets had been on the active roster when Jesse Orosco fanned Marty Barrett; more than 20 percent of them, it turned out, had been wearing a Mets uniform for the last time when they vanished into the pile near the Shea Stadium mound.

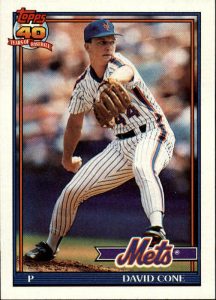

Hearn was a late subtraction, traded at the end of spring training (along with Rick Anderson and future recidivist Met Mauro Gozzo) to the Royals for a pair of unknowns: Chris Jelic and a rookie pitcher named David Cone. At the time, it seemed like one of those shrug-your-shoulders dog-and-cat trades, but with a side of sentimental melancholy: Hearn, nicknamed “Ward,” had filled in admirably for an injured Gary Carter that summer and seemed on his way to being a cult player and fan favorite.

It turned out to be one of the all-time steals in franchise history. Injuries ruined Hearn’s career, while Cone became the next great Mets hurler. By 1988, when Cone won 20 games as co-ace of the rotation, the trade seemed downright unfair. The Mets were a playoff-bound juggernaut; surely they had enough superb starting pitchers without fleecing other clubs out of theirs?

Cone would be a mainstay of the Mets rotation, then return to the city for a glorious run with the Yankees, making himself one of Gotham’s universal fan favorites. (He’s been a familiar face on the YES Network for some time, which we’ll reluctantly forgive.) He’d also prove an athlete who could handle the biggest of towns: open with fans, honest with the media, and no stranger to the far side of midnight. (This Sports Illustrated article, from ’93, is an excellent deep dive into Cone’s psyche that doesn’t shrink from examining his run-ins with tabloids and appearances in police reports.)

But in the beginning, his arrival in New York seemed more like a nightmare than a dream come true.

Cone was a Kansas City kid, raised in a blue-collar neighborhood by a tough-minded travel agent and a mechanic who saw success in sports as a way to ensure their children got the best possible education. (They also demonstrated where Cone got his quirky perspective, though — the Cone children’s backyard Wiffle Ball field was sometimes called Conedlestick Park.) Drafted by the Royals in 1981, Cone made his debut for his hometown team five years later. His first appearance on a big-league mound came in relief of Bret Saberhagen, which strikes me as spooky, given their similarities. At their peaks, both Cone and Saberhagen had more plus pitches than their catchers had fingers, along with a talent for improvising on the mound, and you wondered how they ever lost a game.

Cone was more serviceable than star in his first go-round, still trying to overpower hitters rather than outthink them. But he’d learn during winter ball, and reported to spring training in 1987 armed with two new pitches: a sidearm “Laredo” slider taught to him by Gaylord Perry and a split-finger fastball. Cone made the ’87 Royals rotation, only to be traded to the Mets on March 27.

He was convinced he’d be stuck in Triple-A, but with Dwight Gooden felled by cocaine, Cone began the season with the big club. He was coming into his own as a starting pitcher and a clubhouse presence in late May, when he broke his pinky bunting against Atlee Hammaker of the Giants. He’d be out until August, at which point everything that could go wrong for a Mets pitcher pretty much had — including Tom Seaver, last seen thankfully inactive on the Red Sox bench in the ’86 Series, reporting for comeback duty but then retiring for real after getting lit up by Barry Lyons. The Mets won 92 games, which was valiant but insufficient, but Cone had found he liked New York. He’d also grown as a pitcher, with Ron Darling helping him refine that splitter into a deadly weapon. (Cone would keep tinkering with the pitch, making another advance thanks to the tutelage of original Met Roger Craig.)

Perfection in motion. And oh my goodness did I love him. Cone was slim bordering on undersized — media guides generously listed him as 6’1″ — and bore an odd resemblance to a rather different hero of mine, Luke Skywalker. But while he wasn’t burly, he had the classic mechanics of a power pitcher and had honed them to near-perfection. His right hip was the focal point around which his arms and legs seemed to revolve, with no wasted motion. Cone has said Luis Tiant was his inspiration as a kid, and you can see that — Tiant’s famous for his hesitation and the turn of the back, but that obscures how tight and coiled his motion was. Plenty of power pitchers look impressive on the mound but arrive with mechanics that make you cringe because you can almost hear things grinding and fraying in their shoulders and elbows, but Cone looked like a gyroscope, from the way he loaded his arm down near his hip to the finishing, energy-dissipating kick of his right leg. It was like an engineer and an artist had collaborated to create the Platonic ideal of a pitcher.

Even Cone’s mistakes were mostly endearing. There was the famous play against the Braves where a livid Cone argued so vociferously with the first-base umpire that two enemy runners came home to score while Gregg Jefferies frantically tried to get his pitcher’s attention. I’ll even include the mishap that arguably cost the Mets a return to the World Series. Cone had written for his high-school paper and had a rapport with the beat writers, even joining them on occasion for pickup basketball games. In the ’88 playoffs, Bob Klapisch of the Daily News gathered Cone’s impressions for a ghostwritten column. Overamped after the Mets’ wild Game 1 victory, Cone compared Dodger closer Jay Howell to a high-school paper. Klapisch printed it, and Tommy Lasorda turned the unwise column into a rally cry, covering clubhouse bulletin boards with it and doing everything short of wrapping himself in the flag to protest this assault on Dodgerdom, fair play and the very idea of America. It worked — the vengeful Dodgers drove a rattled Cone from the mound in the second inning of Game 2, the Mets fell apart in Game 7, and I became one of the only people in America who watches Kirk Gibson‘s legendary home run with disgust about what might have been.

Remember that in ’88 athletes lied with a brazenness now characteristic of presidents; more often than not, a baseball player who’d said something stupid would blandly say he’d been misquoted, which too many fans then as now automatically believed. Cone didn’t do that; he owned what he’d done instead of letting Klapisch take the blame, and apologized to Howell. Three years later, cameras caught Cone and Buddy Harrelson arguing furiously in the dugout. Harrelson, a superb coach and baseball lifer but out of his depth as a manager in New York, tried to get Cone to lie about what had happened. Cone refused. The Mets clubhouses of the early ’90s were snakepits crawling with surly malcontents, arrogant and thin-skinned louts, and paranoid backstabbers, but Cone remained a standup guy. (And let’s throw in his sense of humor, best shown off in an Adidas ad that featured Yankee fans helping Cone safeguard his rehabbing arm.)

The Mets traded him in the miserable final weeks of 1992 to the Blue Jays for Ryan Thompson and Jeff Kent. (Like that clubhouse needed another socially inept sourpuss.) Cone won a World Series ring, while admitting that he felt like a rent-a-player, came home to Kansas City and won a Cy Young, was shipped back to Toronto after proving too outspoken for ownership’s tastes during the ’94 strike, and then returned to New York for the Yankees’ 1995 stretch drive. He arrived as a mercenary but would leave as an icon, winning four more rings with the Yankees, battling through an aneurysm that threatened to end his career, and pitching a perfect game on a day in which Don Larsen had thrown out the ceremonial first pitch, which is the kind of marvelous absurdity baseball seemingly has in inexhaustible supply.

A dislocated shoulder reduced Cone to a cameo in the 2000 Series against the Mets, pitching just five pitches, but they came in a crucial spot — he retired Mike Piazza in Game 4 with the Yankees clinging to a 3-2 lead. Then he was gone again, pitching for the Red Sox in ’01. His most notable start that year came against Mike Mussina, who’d replaced him in the Yankees’ rotation; with the score 0-0 in the top of ninth, Cone surrendered an unearned run. In the bottom of the inning, Mussina won the game but lost his bid for a perfect game with two outs and two strikes.

Cone sat out 2002, but still felt the pull of the game. Al Leiter and John Franco coaxed him into a comeback with the Mets for 2003 — the year he represents in our series, though it was his least successful campaign as a Met.

Cone, now 40, made the team and got off to a great start, pitching five scoreless innings against the Expos on April 4 with the loyal Coneheads in the stands to cheer him on. This time around, he was wearing 16 in honor of Gooden — another thing I loved about Cone was that uniform numbers meant something to him, as witnessed by his donning 17 for Keith Hernandez. (His original number, 44, is pretty damn cool too.)

Alas, the good times were not to last. Cone’s arm was sound, but the hip he used as a fulcrum for that perfect windup was worn down by decades of use. He went on the disabled list in late April, came back a month later and pitched two innings in relief in Philadelphia, the same place where he’d struck out 19 Phillies on the final day of the ’91 season, despite staying out all night and fearing he might be arrested midgame. (A woman had accused Cone of rape; Philadelphia authorities decided the charges were unfounded.) Cone pitched two innings, giving up a home run to Placido Polanco and exiting after coaxing a double-play grounder from Jason Michaels.

The next morning, Cone could barely limp across his hotel room. Like many a ballplayer, he’d stayed too long at the fair, and his body was telling him it was time to go. He retired, his roster spot going to 42-year-old Franco, who’d had Tommy John surgery and last been seen at the tail end of 2001, giving up a grand slam to Brian Jordan that still makes me want to lie down in a dark, quiet room for several hours. Franco mock-apologized for forcing Cone out; Cone joked that it was time to give the young guys a chance.

Two days after Cone’s final appearance, the fans at Shea responded to the announcement of his retirement and a video tribute with a standing ovation. Cone wasn’t there to hear it; he’d gone home to have dinner with his wife. He’d written a glittering story — 194 wins, 2,668 strikeouts, five All-Star nods, five World Series rings — but that story was over. Seventeen years later, though, I can close my eyes and still see him plain as day. He’s eyeing the hitter, thinking what he’s going to do with this pitch — and, if need be, with the one after that. He’s got a lot of options to choose from, and if any of them should prove lacking, well, he’ll think of something. And there’s no way I’m betting against him.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1964: Rod Kanehl

1969: Donn Clendenon

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1982: Rusty Staub

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1994: Rico Brogna

2000: Melvin Mora

2002: Al Leiter

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2012: R.A. Dickey

by Jason Fry on 5 June 2020 10:09 am Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

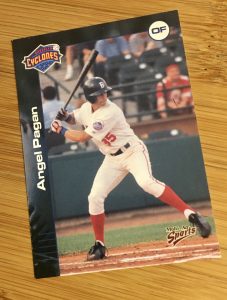

By 2001 I’d been a Mets fan for a quarter-century, which seemed long enough to have things down. But that was the year that introduced a new wrinkle. The Brooklyn Cyclones had come to town, returning pro ball to the borough for the first time since Walter O’Malley ruined everything. Now we could see minor-league games in Brooklyn as well as big-league games in Queens, and root for players who might eventually make their way to Shea.

The Cyclones were an unexpected phenomenon that inaugural season. Manhattan hipsters flocked to Coney Island, joining old-school Brooklyn leather-lungs and families from here, there and everywhere. They packed Keyspan Park, the Cyclones’ trim, sunny ballpark on the beach, tucked beneath the old Parachute Jump. Visiting players used to sleepy games with a couple of hundred spectators would look around in surprise as Cyclones fans made a hellacious racket thanks to the stadium’s metal bleachers. The stadium was great fun, offering between-innings skits that were appropriately bush league with just the right amount of irony added; musical choices a heckuva lot cooler than Shea’s; and an amusingly shambolic ringleader in Sandy the Seagull, a pudgy, sandaled mascot who seemed to have sauntered in through a side door from The Big Lebowski.

That would have been enough for a wonderful summer, but the Cyclones were also good, with a flair for the dramatic. They won their first home game, played before a host of dignitaries, after being down to their last strike in the bottom of the ninth. In the playoffs they beat their fellow newcomers, the Staten Island Yankees, and won the first game of the best-of-three New York-Penn League finals, giving themselves a chance to wrap up the championship at home. Unfortunately, that game was scheduled for Sept. 12, and was never played. The Cyclones had to settle for being co-champions — the tiniest of losses given the terrible circumstances, of course, but also not nothing.

Emily and I were in the stands several times that first giddy summer, and knew we’d be back. The Cyclones were now a part of our baseball lives. And honestly, going to Keyspan was sometimes more fun than a trip to Shea — it was both cheaper and cooler, it had better food, there was stuff to do before and/or after, and the games were typically a crisp two hours instead of a sometimes-soggy three.

The part that was new to us was assessing the players. It would be years before I’d understand the harsh reality of the lower minors: Each year’s Cyclones roster featured a handful of players considered real prospects and a bunch of teammates who were there to fill out the roster. The prospects would be given every opportunity to fail; the others would have to do extraordinary things over and over again to get noticed. It’s a caste system, and a cruel one.

For Emily and me, two players became emblems of that first summer.

One was John Toner, an outfielder with the endearing habit of looking over when the girls in the stands would yell for him. I wasn’t enough of a scout to assess Toner’s baseball abilities, but I’d been around long enough to see he was having the time of his life.

Dream a little dream… The other emblematic player was the Cyclones’ first heartthrob — a lithe, dark-eyed center fielder with a name borrowed from a shoegazer band you wanted your parents to hate. The girls screamed for Angel Pagan; so, in my own nerdy blue-and-orange way, did I. I was certain that he was the one, the Cyclone who’d solve the pitiless math of the minor leagues and show up one day at Shea. Pagan was going to be a star, and I was going to be able to point at him from the back of the mezzanine and tell people how I’d seen him play in a little park on the beach, not so long ago and not so far away, and now just look at him.

Which turned out to be true. Eventually. If you squinted a little.

Toner was back in Brooklyn the next summer, which we were yet to realize wasn’t a good sign; he was out of baseball by 2004. But Pagan kept going: Capital City, St. Lucie, Binghamton, Norfolk. In 2005 he hit .271 with 27 steals in a full Triple-A season. He was only 23; it looked like my dream might even come true a little early.

And then, in the offseason, the Mets sold him to the Cubs.

I was heartbroken — and seethed when Pagan made his big-league debut in Chicago in 2006. He was a part-timer as a Cub, plagued by both injuries and mental lapses, but I didn’t care. He’d been a Cyclone. He’d been meant to be a Met. Anyone could see that — except, apparently, the Mets front office.

And then, a miracle. The Mets reacquired him.

Pagan didn’t become a star in 2008 — in fact, he was lost for the year in July after he hurt his shoulder diving into the stands — but there he was at Shea, just like I’d imagined. (He even rehabbed briefly with the Cyclones.) And when the Mets made the move to Citi Field in 2009, so did he.

2009 — the year to which this profile belongs — was not a good year in Mets annals. We first heard the name “Bernie Madoff” and discovered what he’d done for but mostly to the Wilpons. Not just the country but the entire world was struggling to escape a horrific recession that had been set in motion by arcane investment instruments and the supposed wizards who’d invented them. The new park, emblazoned with the name of those suddenly shaky financial titans, felt more like a monument to Fred Wilpon’s Brooklyn childhood than a home for the actual baseball team he owned.

And the team? The one picked as World Series champs by Sports Illustrated after two heartbreaking finishes in 2007 and 2008? It was a goddamn dumpster fire. Daniel Murphy played left field like a soldier being shelled. In the home opener, Mike Pelfrey served up a home run to the immortal Jody Gerut on his third pitch and later fell down on the mound. Carlos Beltran forgot how to slide. Oliver Perez showed up looking like he’d eaten an entire ZIP code and soon had an ERA to match. Ryan Church missed third base out in L.A. Luis Castillo turned the last out of a win in Yankee Stadium into a walk-off error. Omar Minaya decided that the bizarre behavior of Tony Bernazard, the Mets’ VP of player development, was part of a sinister plot cooked up by beat writer Adam Rubin. David Wright was hit in the head by a fastball, which helped send his glittering career into a tailspin from which it never truly recovered. New acquisition Jeff Francoeur got with the program by hitting into a game-ending unassisted triple play. And the injuries, oh the injuries. Every day seemed to bring a new one: Johan Santana, Carlos Delgado, Wright, Beltran, J.J Putz, Jose Reyes.

If you weren’t there, count yourself lucky.

In a season like that, you take any bright spots you can find, and Pagan was one of them. He somehow avoided the Biblical plague of misfortune, got playing time and showed he deserved it: His final line for the season was a .306 average with 14 steals. The Mets, being the Mets, responded by reacquiring Gary Matthews Jr. for 2009. Matthews proved not to be the answer — it’s hard to play with a giant fork sticking out of your back — and Pagan took his job, then had a breakout year. He hit 11 home runs and brought much-needed speed to the club, stealing 37 bags and playing excellent defense in center. He may not have been the most consistent player — he was still prone to lapses on the bases and on defense, earning himself the nickname El Caballo Loco — but he was definitely exciting, turning a triple play and hitting an inside-the-park home run in the same game. (Alas, the Mets still lost.)

And so there we were — that first Cyclones heartthrob, playing center for the Mets. No, it wasn’t at Shea and there’d been that detour to the Cubs and the Mets were crummy and sometimes Pagan brought too much loco and not enough caballo, but it was at least close-ish to what I’d imagined. Remember those Family Circus cartoons where Jeffy gets sent on an errand and returns later than expected, with a tangle of dotted lines representing his distracted ramblings around the neighborhood? Kid still came home, right?

In 2011, though, Jeffy forgot about the quart of milk for Mom. Pagan got off to a slow start, reacted badly, was plagued by injuries, and alienated both teammates and management. There were highlights — most notably his walkoff homer against the Cardinals, nearly caught by Gary, Keith or Ron in the Pepsi Porch — but there weren’t enough of them, and in the offseason Sandy Alderson sent Pagan to the Giants for a much-needed reliable reliever, Ramon Ramirez, and a similarly dynamic/enigmatic outfielder, Andres Torres.

This time, I wasn’t heartbroken. The caballo/loco ratio was out of whack, and while I still felt affectionate about the original Cyclone who’d made good, I’d also decided Pagan was one of those players who’d benefit from a new clubhouse and new voices. Which turned out to be true — Pagan rebounded to garner some low-level MVP votes as the ’12 Giants won a title, then proved a useful player for them over several more seasons. (The trade was a disaster for the Mets, as Ramirez and Torres both imploded.) Eventually Pagan wore out his welcome in San Francisco too: When the team found itself in desperate need of outfielders in 2017, it was telling that they didn’t ink the guy they’d employed just the year before, the one who was unsigned and loudly advertising his availability. Pagan, by then one of the last of the Shea Mets, never did find a deal; his retirement turned out to be involuntary and more permanent than he’d imagined.

So what does all this mean? I’m tempted to conclude with a warning about how storytelling compels us to search for a moral even when it’s just a bunch of stuff that happened. But that feels both glib and cheap. Here’s a more worthy lesson: Baseball infatuations are part of being a fan, even if they aren’t yet supported by reality. There’s nothing at all wrong with that. Dreaming is free, to quote the philosophers Stein and Harry, and it’s to be celebrated and encouraged. But just remember that even those dreams that do come true might not exactly fit what you saw when your eyes were closed.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1964: Rod Kanehl

1969: Donn Clendenon

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1982: Rusty Staub

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1994: Rico Brogna

2000: Melvin Mora

2002: Al Leiter

2008: Johan Santana

2012: R.A. Dickey

by Greg Prince on 2 June 2020 3:57 am Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

They swept away all the streamers

After the Labor day parade

Nothing left for a dreamer now

Only one final serenade

—Billy Joel

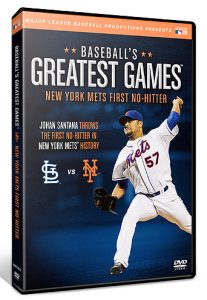

Eight years and a day ago, Johan Santana faced 32 St. Louis Cardinals. He walked five of them and retired the other 27. This might be how we’d express a no-hitter if there was a superstition that demanded you don’t jinx one after the fact.

If “no-hitter” didn’t roll pithily off the tongue, however, the date it occurred wouldn’t have emblazoned itself onto our brains for good June 1, 2012. Given the monumental nature and relative recency of The First No-Hitter in the History of the New York Mets, it may be the one regular-season game date most every Mets fan knows by heart without rancor. June 15, 1977, is pretty deeply ingrained within Metsopotamia’s collective consciousness, but that’s for reasons of infamy and has nothing to do with the Mets beating the Braves that particular Wednesday night. In this century, June 1, 2012, has competition mainly from September 21, 2001, though that’s a date that is subordinate in every telling to another date, from ten days earlier. “Mike Piazza’s home run in the first game in New York after the tragedy of September 11, 2001…” Mike’s homer was a big emotional deal for reasons we all understand, but too many chronological qualifiers preface the narrative and therefore crowd its clarity.

June 1, 2012, doesn’t need any explanation in the Mets fan calendar-to-significance translator. It’s the no-hitter! We all know it, we all love it. I’m not exclusionary as a rule, but it you don’t love it, you’re not part of “we” for the balance of this discussion. Party poopers of the worst order (and, yup, our ranks contain them) can dwell on the five walks; the one ball that may have landed a scooch on the fair side of the left field line without being detected by the only person whose judgment mattered; or the two hands required to count how many starts Johan had left in him after proving himself willing to march into hell for our heavenly cause. Santana spent all of 2011 on the Disabled List and was destined to while away the entirety of 2013 there, too. In between, in 2012, he pitched as good as new for a few months. You couldn’t ask for anything better than The First No-Hitter in the History of the New York Mets as evidence of an exquisite shoulder anterior capsule repair job. You and Terry Collins surely couldn’t ask for 134 pitches, but with Johan, you didn’t have to ask. He’d have been insulted if you thought he’d have to think about an answer.

That date in history. I don’t know how many no-hitters have been pitched in the eleventh-to-last start of a pitcher’s career, but Johan’s was, which is too bad because we liked having Johan around and it would have been swell to have had him stay in our midst as long as contractually possible. He was freaking Johan Santana, after all. From the moment in January of 2008 when we learned he’d be arriving on our scene until it was made clear in March of 2013 that he could no longer contribute to our glorious quest (though by 2013, our quests mostly involved slogging through the next 162 dates), it was freaking awesome to realize that one of the most imposing pitchers of the generation was wearing a Mets uniform.

We had Johan Santana! Pretty sweet, right? And we have a no-hitter thrown by Johan Santana. If that was the extent of Johan’s Mets accomplishments, Dayenu, it would have been enough. But Santana gave us more. In light of 46 Met wins, four successful Opening Day assignments, an ERA title, an All-Star selection and a steamy evening when he tossed a shutout and belted a homer (on the twelfth pitch of an obviously epic at-bat), I’d be willing to say “much more”. I want to say “so much more,” but that might be pushing it.

Johan Santana did not pitch us to a world championship, which was kind of the idea when we sent four young players of reasonable promise to Minnesota in order to have the two-time Cy Young winner wear No. 57 for us. That was probably too much to ask of one lefty, regardless of talent, bearing and track record.

Johan Santana did not pitch us to the playoffs. That is a true statement if we ignore that no Met did more to land us in the 2008 postseason than Johan, whose fiercely urgent presence in Flushing was largely attributable to the failure of the 2007 Mets to finish first in their division or anywhere with a Wild Card. We had a lefty with two Cy Youngs in his past in September 2007 yet came up one game short of where we wanted…no, needed to be. The trade to the Twins may have involved Carlos Gomez, Philip Humber, Deolis Guerra and Kevin Mulvey, but what we were really doing in the offseason preceding ’08 was trading up, casting off our no longer reliable Gl@v!ne for a sleek late-model Santana. Sure, it had a few more miles on it that we might have preferred (those Minneapolis winters can really wear on a vehicle), but the salesman said it could get us where we wanted…no, needed to be.

The fine print specified Santana was one of only dozens of Mets on the September 2008 roster. He wasn’t a member of the creaky bullpen, nor was he made available to play any of several on-field positions that cried out for improvement. Johan Santana could only be asked to carry a team from the mound every fifth day. OK, every fourth day when things got dire.

Johan looked good in February, but he was truly phenomenal come September. Oh, did he carry us that September. My god, do you remember how great Johan Santana was in September of 2008? Mind you, he ranged from pretty darn good to utterly superb from April to August, but in the September of our potential redemption, he was freaking Johan Santana: six starts, four wins, no losses, an earned run average under two, more than a strikeout per inning and the pièce de résistance of pennant-race pitching, an effort whose date you might not instantly recall but whose excellence should never escape you.

The Johan Santana start of September 27, 2008, lives in a class of its own. That it wasn’t a no-hitter — or the no-hitter — is immaterial. We’d never had a no-hitter. We wouldn’t have known what to have done with one. What we had was the cloud that followed us from the previous September to this one. What we required was someone to chase the cloud away.

That September, specifically on a gray Saturday afternoon, the last Saturday afternoon Shea Stadium would ever know, Johan Santana was every element under the sun. He was earth, wind and fire while chasing the clouds away.

What part did you like best? The fact that it was a shutout? That it was a complete game? I mean you had to love that not just for the bookkeeping, but for keeping the pen away. No Heilman. No Schoeneweis. No Ayala. Johan was Santana Claus, and his easily spooked reindeer stayed parked safely beyond the right field fence.

But how about that it was a complete game shutout pitched on three days’ rest when, even then, nobody pitched on three days’ rest? Johan wasn’t nobody. Or just anybody. He was Johan.

Ooh, how about a complete game shutout on three days’ rest with an unmentioned torn meniscus in his left knee, something a pitcher who throws with his left arm probably needs in the scheme of crafting short-rest route-going blankings? The man could have copped to physically falling apart but recognized his team was in more pieces that he might have been, so he strapped it on. Strapped what on, you might ask. Whatever Johan strapped on, it was serious stuff.

Let us not let the legend of September 27, 2008, go the least bit unembellished by the facts. Let us not forget that the three-hit, complete game shutout on short rest and one good knee was prefaced by a note from its author, one he penned in the clubhouse and taped to the wall when he wasn’t busy strapping everything else on. It said, according to contemporary accounts, “It’s time to be a MAN.” At the risk of getting carried away by the concept of manliness as it applies to a silly game of baseball, it might have just as easily said, “It’s time to be JOHAN.”

Why was JOHAN so specific in informing the other Mets what time it was on September 27, 2008? Because it was time for all of them to be as much like JOHAN as they could. It was the 161st game of the 2008 season, or 161 games since many of them gave up a playoff berth in the very same ballpark to the very same opponent, no less. As in 2007, the 2008 Mets held first place in the National League East in September and then, because they must have loved it, set it free. Now they were keeping Cliché Stadium open every bit as much as they were closing down Shea Stadium. This was for all the marbles. There was no tomorrow. Technically, there was one tomorrow, but it was gonna be one marble-less Sunday without a marvelous Saturday defeating the disgustingly pesky Florida Marlins.

Thus, to put it all together, Johan Santana pitched that complete game, bullpen-free shutout on one-kneed abbreviated rest so the Mets could contend for a playoff spot for one more day at Shea. Exactly one more day, as it turned out, because in Game 162 of 2008, the reindeer got loose from the bullpen and, when you got right down to it, it was in fashion if not form Game 162 of 2007 all over again. Santana Claus could give us only Christmas Eve, not Christmas Day, and our stocking came up one lump shy one more time.

But you can’t fairly say Johan Santana didn’t pitch us into the playoffs. He pitched us right up to its front door, or the edge of its chimney. Even Santa had helpers to get him through the necessary portal.

Two-plus months before Johan Santana’s first unforgettable Met date, Billy Joel invited Paul McCartney — a veteran of Shea’s multipurpose utility c. 1965 — on stage to add an indelible climax to the ballpark’s final big-time concert. In retrospect, Alec Baldwin narrated on a DVD commemorating what was billed as The Last Play at Shea, the grand musical performance constituted “the stadium’s last magic moment”.

It was indeed magic. But it took place on July 18, 2008. I don’t have a twelve-year-old calendar handy, yet I’m pretty sure September 27, 2008, came later.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1964: Rod Kanehl

1969: Donn Clendenon

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1982: Rusty Staub

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1994: Rico Brogna

2000: Melvin Mora

2002: Al Leiter

2012: R.A. Dickey

by Greg Prince on 1 June 2020 4:18 pm Imagine a world in which you walk down a fairly busy street; you feel perfectly fine; you carry no existential worries as you inhale and exhale without a second thought; you inherently respect everybody you pass, regardless of what they look like or where they come from; they inherently respect you; you take it as a given that everybody’s rights are valued and protected; maybe you have a few extra bucks in your pocket; you’re headed somewhere to say “hey” to those you know, those you’re happy to get to know, those you will greet by touch as well as by word; you’re gonna sit down with them; you’re gonna dig into good food and drink with them; and you’re gonna watch the game with them, whatever the game is. The game is likely secondary, but it’s on, as is the light in this place you’re so glad you know about.

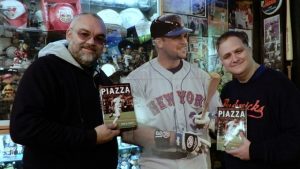

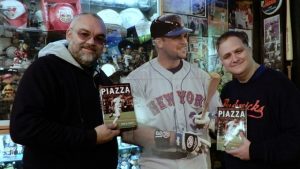

Imagine there’s a Foley’s. It’s easy if you try. For sixteen very recent years, it required no imagination. It was right there on 33rd Street in Manhattan, a few doors west of Fifth Avenue. I knew it from personal experience for about a decade in the middle of its glorious run. You couldn’t have drawn up a better model of or reason for human interaction.

The world in which Foley’s operated is on pause, therefore Foley’s has ceased to be a part of it. That hurts to know. A lot hurts to know these days, but in the context in which we’ve been fortunate to conduct ourselves on our better days — sports; sociability; soda or perhaps something stronger — word that Shaun Clancy is closing Foley’s stings more than a little. It doesn’t take away from understanding larger problems to acknowledge that this, too, leaves our heart aching.

Foley’s advertised itself as an Irish bar with a baseball attitude. I’d add it contained a Yiddish underpinning. It was, as my mother liked to say by way of her highest praise for anything, haimish. As Lou Monte might have translated for you nice ladies and gentlemen out there who don’t understand the Jewish language, that means it was warm, cozy, homey. You know…haimish.

The only problem with the above description is the use of the past tense where Foley’s is now concerned. “Was” doesn’t suit an establishment where you so look forward to returning as soon as the next opportunity arises. Sadly, opportunities have gone on hiatus for bars, restaurants and any place folks get together to do all the things Foley’s was expert at enabling.

Every time I’ve published a book, Foley’s has been there one way or another to support it. Every time almost anybody in New York has published a book or pursued a worthwhile cause, Foley’s has been there to support it. Lunch was splendid, dinner superb, the beer as accessible as you wanted it to be. The warmth was built into its walls in 2004 and radiated with enveloping coziness until COVID-19 did its number on the business. In announcing that this vital baseball shrine — proudly bearing the name of a revered sportswriter in these hysterically press-hostile times — was out for the inning, owner Clancy allowed the game itself hasn’t necessarily been irrevocably called. Hopefully Foley’s gets another at-bat somewhere else in town. Hopefully we all have the chance to pass through its transplanted turnstiles again.

At Foley’s, Shaun Clancy (left) made everybody feel like a Hall of Famer. Hopefully by then all of us are the things that none of us can take for granted at this moment. We’ll all feel well. We’re all feel reasonably well off. We’re all feel safe not just from viruses and hardship but from the kind of darkness you keep thinking must have been left to rot in the past, yet keeps resurfacing from the worst instincts of a country you’ve always truly wanted to believe is progressing relentlessly toward fulfilling its brightest ideals, periodic backslides notwithstanding. This should be about lifting a glass to a wonderful bar and its gracious staff and a restaurateur who made everybody feel like a Hall of Famer, but it’s hard to confine your thoughts to a baseball attitude when you know too many Americans are taking a beating figuratively, literally and everywhere in between.

In December of 2012, Friend of FAFIF Sharon Chapman went to typically selfless lengths to arrange a release party for one of my books, an event that doubled as a celebration of my fiftieth birthday, which has pretty much eliminated the need for me to ostentatiously celebrate any further birthdays, because nothing will ever top that Saturday afternoon. Of course it was going to be at Foley’s. Of course it was going to be imbued with a baseball attitude. Of course it was a fantastic day. We sang every verse of “Meet the Mets” loud enough so that maybe even the infiltrating SantaConners upstairs got an earful.

But the day before, I had my doubts about doing it at all because that was the day a madman opened fire at an elementary school in Connecticut and killed children and adults who looked after them. It just didn’t seem right to have a party. Maybe I’d seen one too many Aaron Sorkin productions in which everything comes to a stop because one American’s tragedy is every American’s tragedy. We had the party. I distinctly recall a few side conversations about the horror of Sandy Hook before getting back to the good times. Maybe that’s a metaphor for how we do things in this country when we’re fortunate to have options.

Here’s to everybody having options. Here’s to everybody having health. Here’s to Foley’s. Life may not be the best sports bar you can imagine, but we should all treat each other as well as Shaun Clancy treated everybody on 33rd Street.

by Greg Prince on 29 May 2020 1:57 am Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

You’ll never know the pleasure of writing a graceful sentence or having an original thought.

—Aaron Altman attempting to verbally torment a trio of toughs after his high school graduation, Broadcast News

I want to say that the first time I remember encountering the word “literati” was in a story that referenced Peter Gent, author of North Dallas Forty. The conceit was that Gent would come into Manhattan with the Dallas Cowboys in the days when their dates with the Giants awaited at Yankee Stadium and attend kickoff-eve cocktail parties where the football player would make highbrow book editor-types swoon primarily by being a jock who spoke in complete, complex sentences. In the article I’m sure I read yet can find no evidence of despite myriad searches combining “literati,” “Peter Gent” and “cocktail,” there was much backslapping on the Paper Lion circuit when it was learned that this sui generis receiver had been traded to the Giants and would therefore be accessible all autumn long to talk pigskin and existence in terms that went beyond hut-one, hut-two.

Alas, articulate Gent was waived by the Giants as training camp ended. Never a star in the NFL, he didn’t become truly famous until the publication, several years after his retirement, of North Dallas Forty, a novel that told a real story about life in professional football. Maybe he was a cocktail party secret in the ’60s before going big-time in the ’70s (so secret that even Tom Landry must not have realized his player was out and about). Or perhaps I’m confusing something I read in the book written by Gent with something I read in a magazine about Gent. Or Dan Jenkins wrote something similar somewhere about somebody else, actual or fictional, given that Semi-Tough and North Dallas Forty were published around the same time and I got around to reading them around the same time. Or am I conflating these cultural touchstones with that episode of The Odd Couple in which Oscar owes the owner of a football team from Texas (tycoon Billy Joe, portrayed by Pernell Roberts) a large sum from poker losses and, because this is The Odd Couple, Oscar settles up by convincing Felix to let his band the Sophisticados perform at a hoedown, albeit as Red River Unger and the Saddle Sores?

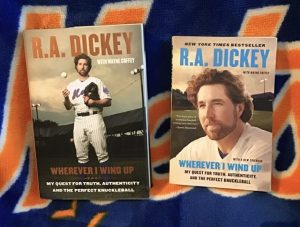

Whatever the hell it is I’m thinking of, the image returned to my consciousness right around this time of year — it’s late May, in case you’ve lost track — ten years ago. That was when R.A. Dickey was called up from what we used to know as the minor leagues and introduced himself to all who love the Mets, but sent out a subtle dog whistle to those of us who not only cherish the Mets but relish the English language. If our little subset had been indulging in a Gent-eel soirée, we’d have all set down our martini glasses and focused our attention at game’s end like a laser on what the stranger from somewhere South of Staten Island was saying on SNY.

He got his picture on baseball cards, too. Then we’d have each lunged for the nearest Thesaurus to craft a phrase less hackneyed than “like a laser”.

I doubt Dickey knew he was doing it. That’s what made him all the more rootable. He was just being himself — and in the process of evincing authenticity, he was endearing himself to everybody who’d gone after the verbal portion of the SATs with relative gusto while dreading the math portion. R.A. Dickey is to Mets baseball as [blank] is to [other blank]… There is no obvious answer or exact analogy. Rather than sweat a response, better you should fill in your name, settle for however many points a legible signature nets you, and ditch the test in time for first pitch Saturday afternoon. Besides, for as much as aptitude as he demonstrated by throwing a singular knuckleball between his unheralded arrival as a 35-year-old reclamation project in 2010 and the All-Star zenith of his Met tenure in 2012, there was nothing standardized about R.A. Dickey.

It’s been a decade since his Met debut, yet it hasn’t been so long since we tingled to the innings when R.A. baffled batters and the minutes when he described the process. He used words like “anomaly” and “propensity” and “compulsion” and “gingerly”. When he pitched well enough to win, he was satisfied his work “yielded this ripe a fruit”. His best pitch had to be “trustworthy”; it got better via “little mechanical nuances”; one swing could change “the culture of what’s going on in the moment”. The extra-large mitt he lugged from organization to organization so his next catcher could hope to handle his knuckleball? “This glove has a personality of its own.”

And that was just R.A. talking through his first season as a Met. Dickey didn’t have me so much at “hello” as “inconsequential.” That was the word Dickey chose to describe an atmospheric factor a beat writer asked him about after he’d lost a close one to Tim Lincecum in San Francisco. Did the wind play a role?

“Inconsequential,” he said. Swoon! Give Jon Niese a hundred hard-luck starts, he’d never come up with “inconsequential” (nor resist the opportunity to cop an alibi). It wasn’t the first time Dickey speaking about his pitching had gotten my attention, but there was something about casually tossing off five suitable syllables where nobody would have blinked twice at “nah” placed me in his corner forevermore.

The pitching didn’t hurt, either. The pitching was key, actually. The grandest vocabulary in the clubhouse doesn’t say diddly if it comes attached to an ERA over six. English Lit major Dickey and that hard knuckleball only he threw landed like a knuckle sandwich in the face of National League hitters who hadn’t seen anything like it cross a plate near them. R.A. had it going on when he emerged from the exurbs of nowhere in 2010; when he enhanced his knuckler’s strengths in 2011; and, come 2012, when he pulled down twenty wins and the Cy Young. Between revelatory starts, he collaborated on a best-selling not to mention intensely compelling book, co-starred in a delightful documentary about his signature pitch and scaled one of the world’s steeper mountains.

The language-lovers among us who absorbed every step of his Metsian journey, especially his accounts and descriptions thereof, felt a thrill going up our leg, to borrow a 2008 phrase from Chris Matthews (himself more about Hardball than a knuckleball). I noticed that as much as virtually every Mets fan in creation toasted R.A.’s success warmly and effusively, it was those of us who worked closely with the language who seemed most thrilled on the man’s behalf. We intrinsically felt we had one of our own was out there on our behalf. Editors. Writers. Educators. This wasn’t just a Met excelling at pitching. This was a kindred linguistic spirit. We were in awe that somebody like this was so good at the sport we cherished even if most of us had never had any hope of playing it at any competitive level beyond the schoolyard (and even back then not that competitively).

“Dickey is too good to be true on so many different levels that you almost expect to wake up and find out that you’ve dreamed him,” Prof. Dana Brand once wrote. Dana, in case you weren’t around in the latter 2000s and earliest 2010s, was a leading light of Met lit; his two books of essays — Mets Fan and The Last Days of Shea indicate the glow from his writing remains eternal. Before dying too soon nine years ago this week, Dana led the English department at Hofstra University and was putting together the Mets’ 50th-anniversary academic conference there. That Dickey and Dana crossed temporal paths, however briefly, vouches for some kind of cosmic karma in our world.

“He has none of the pretentiousness that ballplayers sometimes have when they use ‘big words,’” Dana elaborated on the subject of the soft-spoken Tennessean. “He uses the English language with thoughtfulness and precision. I hope he’s our ace for the next ten years.”

In December of 2012, barely more than a year-and-a-half after Dana’s passing, R.A. was traded to Toronto for minor leaguers who grew up to become 2015 National League champions Noah Syndergaard and Travis d’Arnaud. The record will show this trade as a win in the annals of our ballclub. With Dickey on the back end of his career and Syndergaard’s potential blatantly apparent, the deal made extraordinary sense on paper and revealed itself as prescient in pursuit of a pennant.

Still, you miss someone like R.A. Dickey the way you miss someone like Dana Brand, men who could make words dance regardless of the status of their respective ulnar collateral ligaments. I’m sort of sorry R.A. didn’t get to pitch in a more successful Met era, but part of me doesn’t mind that much. R.A. Dickey was an era unto himself every fifth day. He gave us something we never had before during a period when we surely needed an element that surpassed the sum of our sub-.500 parts. We’d be blessed by the presence of superb pitching aces in seasons to come, just as we’d been fortunate to have benefited previously from twenty-game and Cy Young winners.

But to get to continually tell R.A. Dickey stories for three seasons…and to now and then recall suddenly many years later the joy he provided through his elite manner of pitching and his singular style of talking…well, let’s just say R.A. Dickey is to Mets baseball as nothing else ever was or ever will be.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1964: Rod Kanehl

1969: Donn Clendenon

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1982: Rusty Staub

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1994: Rico Brogna

2000: Melvin Mora

2002: Al Leiter

by Jason Fry on 26 May 2020 4:00 pm Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

Richie Ashburn has two Topps cards as a New York Met.

The first, his ’62 card, is what’s known in baseball-card circles as a BHNH. That’s “big head no hat,” a shot taken capless and from chest up, without the team logo showing. Such shots were insurance in case a player was traded — or, in this case, if baseball expanded and Topps had to include players with their new clubs before spring-training photographers got to work. Ashburn, hatless, is wearing Cubs or Phillies pinstripes. He’s working his tongue over his lower lip, as if he’s about to stick it out, and his brows are lowered. He looks perplexed, like he’s sizing up something strange and possibly dangerous.

Ashburn’s second Mets card is from ’63, and shows him in a proper Mets cap, looking heavenward, as if spying some greater reward. It’s what’s known as a “career capper,” one that includes a player’s full lifetime stats. Because Ashburn never suited up for ’63 with the Mets, or with anybody else after ’62.

Between those two cards lies a story.

Just wait till you see the expression he wears after being a ’62 Met. Ashburn is one of the towering figures in the lore surrounding the 1962 Mets, they of the historically hapless 40-120 record and our year of consideration. But his role in that oft-told story is an interesting one. He’s not the jester (Marv Throneberry), the ringleader (Casey Stengel), the perpetual victim (Roger Craig), the shocked bystander (Gil Hodges), the sad clown (Don Zimmer), the guy in on the joke (Rod Kanehl), or one of the revealing cameos (Harry Chiti, Joe Pignatano, Choo Choo Coleman, the two Bob Millers as roommates). Ashburn was the straight man, the consummate professional at the center of the carnage and mayhem, perplexed by where he’d found himself and what he’d done to deserve it.

Which isn’t to say he didn’t have a sense of humor about it. Ashburn was Cyrano to Throneberry’s Christian, feeding Marvelous Marv lines from the locker next to his and turning a sad-sack failed minor-leaguer into a shambolic legend. He dined out on ’62 Met tales for years, or at least endured them, patiently answering fan mail and sprinkling the stories into his reminiscences in the Phillies’ broadcast booth and the Philadelphia sports pages.

You’ve probably heard those tales before, but they’re too good not to revisit.

The most famous yarn bestowed a name on a noted indie-rock band: Ashburn manned center for the Mets, but on pop flies he kept getting run over by Elio Chacon, the team’s enthusiastic but erratic Venezuelan shortstop. Eventually Ashburn figured out the problem was the language barrier, and enlisted the bilingual Joe Christopher to help. Christoper taught Ashburn that “I got it!” was “Yo la tengo” in Spanish. Ashburn tried out his new language skills on Chacon, who beamed. “Si, si, yo la tango.”

The next time there was a pop-up behind the infield, Ashburn hustled in to catch it and saw Chacon steaming in his direction. “Yo la tengo! Yo la tengo!” he hollered. Chacon obligingly pulled up and Ashburn camped under the ball — only to be knocked sprawling by Frank Thomas, the left fielder.

(By the way, when I was in college Yo La Tengo played a show in town and got a ride back to wherever they were staying, only to have the driver somehow mistake a pedestrian path for a city street, drive across our cross-campus lawn, and crash into a building. Which struck me as the ’62 Mets of indie-rock touring.)

But my favorite Ashburn story is a subtler one.