The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 10 October 2015 2:37 am A while back I declared that we’d already won, and anything else that came our way would be lagniappe — games stolen from wintertime. That wasn’t an attempted reverse jinx (though I’m far from above such things) — I meant it. The postseason’s a crapshoot but gets all the attention; the regular season’s the prize, but the narrative turns it into a participant trophy unless the finale is a parade. It’s a shame, and we should resist the pressure to think that way.

But that’s not to say that this month of glorified exhibition games isn’t electric, exciting, joyous and terrifying. It’s all of the above, and Friday night I realized that nine empty years have left me sorely out of practice. I was pretty calm during the day, watching the Blue Jays and Rangers try to defeat each other and the Strike Zone of Mystery and then seeing a slice of Astros-Royals. But by midway through the Cards-Cubs tilt I had tunnel vision and was reduced to fidgeting and checking the time. And by first pitch I was a disaster, sitting rigid on the couch and reminding myself to breathe.

The game wasn’t exactly one to encourage relaxation, either. It was fascinating and riveting, a duel between two pitchers throwing a baseball about as well as it can be done. There were only two questions:

- Which ace pitcher would make a mistake?

- Which ace pitcher would get tired first?

The answer, in both cases, was Kershaw. The mistake came in the fourth, facing Daniel Murphy — the same Daniel Murphy I’d just been grousing on Twitter shouldn’t have been starting. That’s another marvelous thing about baseball — sometimes you’re over the moon to be wrong. Murph crushed a 2-0 fastball to the back of the right-field bullpen, one of those bolts he delivers now and again. Seriously — the ball wound up with DANIEL imprinted on it, like a 105 MPH iron-on. I am not kidding. Having connected, Murph cocked his bat like a sword, then discarded it and floated around the bases having given the Mets a 1-0 lead. (Oh, and this is adorable.)

It looked like that was all the Mets would get, though, because Kershaw was spectacular, carving up hitter after hitter with evil sliders and curves that looked hittable at the 59-foot point but then dived through the bottom of the strike zone. Or, on occasion, veered around it to check in at the point at the back of the plate — witness the backdoor slider that erased David Wright in the top of the third, followed by an impossible curve that bagged Yoenis Cespedes. (The pitch that got Wright was a strike, though you’d never know it by TBS’s tire fire of a strike-zone widget, which seemed calibrated to the back of the plate rather than the front.)

Anyway, Kershaw was spectacular, but Jacob deGrom — he of the shaggy hair and sheepish grin — was a little bit better. DeGrom got there via a harder road, relying on high-90s heat at the beginning and then finding consistency with his slider and change-up late, but he wound up in a better place: 121 pitches, seven scoreless innings and 13 strikeouts, the last claiming old nemesis Chase Utley. The list of Mets to fan 10 or more in a postseason game is a short one: Dwight Gooden (in ’88) and Tom Seaver (twice in ’73), and now deGrom. And only Tom Terrific joined him in fanning 13. You don’t have to be as historically minded as this blog to know that’s pretty good company.

DeGrom’s final inning came after the Mets had broken through against Kershaw and Pedro Baez. The Mets were hunting fastballs early in counts, but the rest of their plan was to wear Kershaw down on a bizarrely hot night. Witness Wright’s terrific first-inning AB, a 13-pitch walk, and the group effort in the seventh. Lucas Duda, Ruben Tejada and Curtis Granderson all walked, sending Don Mattingly out to get his ace and bringing Baez in to face Wright with two out.

It’s been gratifying — to say the least — to see Wright return and contribute, but that seventh-inning at-bat was even more heartening than the first-pitch home run in Philly. The David Wright of his first years in Shea reminded me of Edgardo Alfonzo with his knack for taking a pitcher’s count and grinding his way to a neutral count or an advantage, then getting his pitch and hitting it hard. The David Wright of Citi Field looked different, too often expanding the strike zone and doing the enemy’s work for him. The Wright we saw in Game 1? That was Shea David. Facing Baez for the first time, armed only with a Michael Cuddyer scouting report, Wright worked his way to 3-2 and then rifled a fastball over the infield, making a terrifyingly slim 1-0 Met lead into a merely nerve-wracking 3-0 Met lead. Tyler Clippard hit a bump in the eighth, as he has too often of late, but Jeurys Familia collected four outs and the good guys had won.

We’ve survived Clayton Kershaw. Now here comes Zack Greinke, who’s as frightening as Kerhsaw, if not more so. But Noah Syndergaard‘s pretty capable too — and he’ll only be followed by Matt Harvey and Steven Matz.

Saturday night will be terrifying, of course — but after nearly a decade of spending October as a spectator in search of temporary loyalty, it’s a good kind of terrifying. And I’m looking forward to whatever these games bring, joyous outcome or not. We’ve had our cake, but I’ll take all the icing I can get.

by Greg Prince on 9 October 2015 11:05 am Every day between October 20, 2006, and October 8, 2015, had something in common. For those 3,276 consecutive days spanning exactly 468 weeks, the New York Mets did not play a postseason baseball game. The total is a little misleading since the vast majority of those days featured no postseason baseball games, but enough of them did so that — at least to us — the Mets’ absence from them was as noticeable as it was vexing.

Vex no longer, calendar. On the 3,277th day, we have a Mets postseason baseball game. For the 75th time in franchise history. For the first time since October 19, 2006, which is a date that is about to stop taunting us from its perch in the ever-more distant past.

In case you’ve forgotten (it rarely gets mentioned anywhere), the most recent pitch a Met saw in postseason competition was taken for a strike. The next pitch a Met sees in postseason competition will probably be taken, too. Curtis Granderson almost always leads off and Curtis Granderson almost always takes the first pitch. Ball or strike, we will be underway in our eighth postseason.

Can you believe it?

Of course you can. You know the Mets won a division title this year. You saw it for yourself less than two weeks ago. You maybe fretted in its aftermath. And then you were inundated with reminders that it was real. The Mets logo pops up here and there within listings of postseason games to be played. It’s right there among the perennials and the similarly unfamiliars. You keep running across dispatches about who will and won’t be on the roster for games about to be played. You grasp that it’s October 9, 2015, and there is a Mets game to be played tonight in Los Angeles, then another there tomorrow, and then another on Monday, that one at Citi Field. The other day the Mets sent out a press release announcing cricket will be coming to their ballpark in November. Usually in the fall, the only sound you hear at Citi Field is crickets.

It will sound different Monday night. It will feel different all weekend. It feels different already and the feeling just keeps intensifying. My god, every baseball game that remains this year will go toward determining the world champion. Only eight teams are playing in them. And ours is one of them.

Can you believe it?

Thursday night I watched the Royals and Astros begin their Division Series. That would have sounded half-ridiculous a year ago, completely absurd a year before that. But things change in baseball. The Royals stand as defending American League champs and the Astros have definitively turned their fortunes around. On the mound after a rain delay at Kauffman Stadium were Collin McHugh for Houston, Chris Young for Kansas City. It made for an ad hoc 2012 Mets rotation reunion, bringing together two pitchers I saw start Met losses two days apart three years ago, two pitchers in whom the Mets saw no future, two pitchers now flourishing on the October stage for somebody else.

In an October as recent as 2014, that would have stung. On October 8, 2015, the last of those 3,276 days when the Mets weren’t playing a postseason game, it was fine. It was more than fine. It was evidence that the Mets have such an excess of talent that they can be generous in spreading it around.

No recriminations for trading Collin McHugh for Eric Young. No thoughts that Chris Young might have been handy to have kept around. No second thoughts that Carlos Gomez, who entered for the Astros as a pinch-runner in the top of the eighth, should have been a Met again as he was heavily rumored to already be this past July, no revisionist reconsideration that he never should have been traded in the first place in 2008. No hard feelings that when the Astros’ lefty specialist Oliver Perez — starting pitcher for the Mets in their last postseason game prior to tonight; immense implosion for the Mets somewhere in the middle of these past nine years — came on and retired his only batter in the bottom of the eighth.

As advertised, even if a little later than planned, David Wright will be a part of TBS’s postseason coverage. (Image courtesy of Deadspin.) Live and let live when you’re a part of October. You might have forgotten, since it’s been so long. It wasn’t supposed to go on for nine years like this. TBS took on postseason baseball in 2007. They were excited to hype certain stars who they knew would be intrinsic to the action they were paying to broadcast. One of them was David Wright of the N.L. East-leading New York Mets. Somewhere I have a brochure with his picture on the cover touting TBS’s coming coverage. Somewhere a billboard was erected with his picture, signifying that he was going to be a key player on their air.

He will be. It just took a little longer than expected.

The Mets’ postseason highlights — despite what MLB erroneously advertised that November — were not embellished in 2007. They were not added to in 2008, either, despite the trade that sent Gomez and three others to Minnesota for Johan Santana, another pitcher from those 2012 Mets. Santana made 2012 worthwhile one June night in particular, but couldn’t singlehandedly shove the Mets into October in 2008. R.A. Dickey, the Most Valuable Met of 2012, is on a postseason roster of his own. He’ll start if-necessary Game Four against the Rangers on Monday for the Blue Jays, a team that’s waited about two-and-a-half times longer than the Mets to be in one of these series. R.A.’s been waiting his whole life for a moment like this. It will come two days after the pitching prospect for whom he was traded, Noah Syndergaard, makes his first postseason start.

There’s something for everybody this October. There’s something for select 2007 Mets, a handful of 2012 Mets and, most gloriously, all of the 2015 Mets. Granderson Wright, Syndergaard, as many as 22 of their teammates, depending on how benches and bullpens are deployed — they’re here. They’re a part of this. Check your schedules. It’s October 9 and the Mets are still indelibly inked onto them.

With that first pitch from Clayton Kershaw to Curtis Granderson, we’ll pass the “here” stage and the happy-to-be-ness that accompanies it. Ball one or called strike one will mean it’s all business. Just the thought that Curtis might be down oh-and-one to Clayton makes me exceedingly nervous, and first pitch is twelve hours away as I write this.

But that’s all right. We’re supposed to be nervous when the Mets are in the postseason.

These games will go by far too fast and far too slow. If the Mets grab a lead, we’ll wish there was a clock to run out. If the Mets fall behind, we’ll be shaking trees for extra outs just to keep the whole thing going. If it’s tied, all bets are off. All bets are off anyway. Maybe you’ve read previews that the Mets are a sure thing to win or not win. I glance at them but don’t take them seriously. We are in true Nobody Knows Anything territory here. When the season commenced, nobody knew Kansas City would be back or that Houston and Toronto would arrive or that our Metsies would be snapping a string of 3,276 days without a postseason appearance. If forecasts were that easily translated to fact, Bryce Harper would be a bigger topic of conversation in Washington today than Rep. Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) was yesterday.

There’ll be a new Speaker of the House before the Nationals are in the playoffs, and the Speaker of the House situation is in utter turmoil. McCarthy was a lock to get the gig on the Hill, almost as much as the Nats were guaranteed to win the division. Now his party has no clear successor to John Boehner and the Nationals have no party whatsoever. Like we said, nobody knows anything.

There are no 1-seeds vs. 8-seeds in baseball. There is no 7-9 fluke qualifier offered up as sacrificial snack for the 14-2 behemoth. Everybody who gets here after 162 games has a chance. Everybody who gets here is for real. We are for real. We are in the playoffs for real. Just like the Dodgers. Just like the Cubs and the Cardinals. Just like Dickey and Young and McHugh and Gomez and Oliver Freaking Perez.

Can you believe it? I can.

***

While you stand by (and hopefully stay fully awake) for first pitch, here are a few other items to occupy your stray attention.

• Andrew Wyeth produces a neat article in the Record of North Jersey about the wonders of #MetsTwitter. I’m quoted for more than 140 characters.

• W.M. Akers reflects wistfully on last Sunday at Citi Field for Vice Sports. Something I wrote here is graciously mentioned in passing.

• Pete McCarthy had Mets fan and minority-owner Bill Maher on the WOR Sports Zone a couple of nights ago. You should listen to their conversation. Maher gives some pretty good insight on what it’s like to have a literal stake in the team he loves. (McCarthy, by the way, gives sports talk radio a good name and I recommend enjoying his show nightly on 710 AM or the iHeart radio app.)

• Michael Garry takes his Game Of My Life: New York Mets book tour to the beautiful Bergino Baseball Clubhouse (67 E. 11th St., in Manhattan, between Broadway and University Place) on Wednesday night, 7 o’clock, October 14. It’s an off night for potential NLDS activities, so your priorities are safe. Michael will be bringing Ed Charles with him. Any night spent in the company of the Glider is a championship experience. RSVP info is here.

• If you relish the journey as much as the destination, check out a book focused on what it’s like when the Mets don’t have an October appointments. It’s called The Seventh Year Stretch: New York Mets, 1977-1983 by Greg Prato. I haven’t read it yet, but I did read one of Prato’s previous works, Sack Exchange: The Definitive Oral History of the 1980s New York Jets, and devoured it like Joe Klecko used to devour quarterbacks.

• And, oh yeah, Let’s Go Mets! Can’t say that enough.

by Greg Prince on 7 October 2015 4:04 am Regardless of what the Trade Winds told us in the mid-1960s regarding the plight of displaced Southern California surfer boys, New York’s an awesome town when you’re the only baseball team around.

Welcome to the autumn of our municipal content, the one featuring the Mets and, as of the completion of the Houston Astros’ shutout victory in Tuesday night’s American League Wild Card game, only the Mets. As some of the sanctioned t-shirts declare, the postseason is ours…and nobody else’s in the Metropolitan Area.

And as some other official MLB t-shirts might be amended to suggest, Take October Off, Yankees.

This will be a brief gloat, for there are substantial accomplishments to be nailed down, but a gloat is in order. The Mets, you see, did something they hadn’t done in a quarter-century. They finished with a better record and higher in the standings than their neighbors to the slightly north. That didn’t used to be an achievement worth noting. It was just the way it was: four times in five seasons between 1969 and 1973; six times in seven seasons between 1984 and 1990.

Then a period we shall refer to as an aberration set in and wouldn’t easily budge. But that’s over, at least for now. Just like the Yankees’ presence on your playoff calendar.

While we indulge our Sheadenfreudic impulses and enjoy a quick, low-key Elimination Day celebration (because, despite this occasion having occurred 14 times in the past 15 years, it never gets old), we turn our attention fully, as the rest of New York does, to what the Mets can and should do now that they’ve got the autumnal stage to themselves.

They can and should do big things.

Yet they can’t do big things until they take care of every little thing along the way. I’m reluctant to set a near-term long-term goal for them since I’m a firm believer in taking everything one game/day at a time. We know they’ve finally arrived at the entrance to the rainbow after laboring under only clouds for a veritable eternity. We know what the goal at the end of the rainbow is, but they need only concern themselves for the moment with Game One of the National League Division Series. Actually, they should just concern themselves with preparing for Game One since the game doesn’t start until rather late Friday night. In the interim, just have the best workout possible. Or, failing that, just show up to the workout as soon as possible. That would be a start.

As for the near-term long-term goal, let’s put it this way: New York needs the Mets. New York needs the Mets to go as far as a New York team can possibly go (and I don’t meant the way the Dodgers went as far as they possibly could from Flatbush).

New York needs a world championship. The Mets need to be the ones to give it to us. Not just us, as in the Mets fans, but we who live in these environs. We who have been aching to live in a Mets town, a shared Mets state of mind, an ADI with a capital M-E-T-S.

Finishing with a better record than the Yankees is nice (very nice). Remaining on the field longer than the Yankees is nice (very nice). But now that we’ve outwon them and outlasted them, it’s time to give New York what it deserves.

This is the greatest city in the world, we are continually told and love to tell ourselves. You’d figure there’d be a world championship banner flying somewhere around here. Yet there isn’t. There hasn’t been for quite a while.

How long? Long enough.

Let’s set our parameters. Let’s look at this through the prism of the traditional Big Four professional sports — baseball, football, basketball and hockey (sorry, soccer) — and the local franchises that represent the greater New York City area. Those would be the Mets, Yankees, Giants, Jets, Nets, Knicks, Islanders, Devils and Rangers. Yes, one of those teams calls itself New Jersey; one used to; and two others play there, but our rule of thumb is if they win a championship, it would be covered giddily by local New York television newscasts and generally treated in enthusiastic bandwagon fashion by other local New York media.

Mind you, the idea of a “New York” world championship doesn’t necessarily hold universal appeal in these parts. For example, there have been 27 I can immediately think of that I wish had never occurred. I doubt there’s anybody who isn’t paid to who roots or even pretends to root for all nine of the aforementioned teams. That brand of sentiment might work where there’s one franchise per league in a given city. We, on the other hand, compose a gorgeous mosaic of diverse and contrary interests. We love New York, even if we probably can’t stand at least half of the teams that play here.

Then again, there’s always gonna be somebody who sees a bandwagon, any bandwagon, and will hop on board toward its finish line without being weighed down by the morals and ethics attached to crafting fleeting loyalties on the fly. Call them “New York” fans. Or anything you like.

The last time New York had a bandwagon to ride successfully all the way to its logical conclusion was February 5, 2012, when the Giants won Super Bowl XLVI. That was 1,340 days ago. Given that there is no professional sports championship to be captured on October 7, 2015, that exact total is provisional. The real number of days to keep in mind lies somewhere between 1,364 and 1,368, which would take the New York championship drought up to somewhere between October 31 and November 4. That encompasses the soonest (Game Four) and the latest (Game Seven) the 2015 World Series can be won.

That’s when the Mets can end the drought. That’s when the Mets can be New York’s world champion. That would be very nice (very, very nice). But would it mark the end of a particularly or historically long New York championship drought? For some, who need a good bandwagon ride every few months, of course. Put up against other championship droughts, it’s not close to being the worst it’s ever been, but we are in danger of verging on feeling unusually arid.

The longest New York has ever had to wait between big-time professional sports championships goes back to the dawn of big-time professional sports in New York. The Giants — the baseball Giants, that is — won the World Series on October 14, 1905. They won it again on October 3, 1921, with nobody else (meaning the Robins/Dodgers and Highlanders/Yankees) winning one in between. That was a stretch of 5,843 days in the championship desert for New York. There were no local television newscasts to bemoan our shortcomings in those days, attributable entirely to the total lack of television. It’s probably not fair to compare those days to these days.

A semblance of these days didn’t really get rolling until the 1920s, when you had the three baseball teams, the football Giants and the earliest Rangers. The baseball Giants repeated as world champions in 1922, a mere 360 days following their 1921 triumph. Thereafter, though, mostly you had the Yankees. They won their first World Series on October 15, 1923, and then began breaking most of the resulting relatively short New York droughts themselves. Quite often it was a matter of the Yankees winning New York a championship on some October afternoon and then winning New York its next championship roughly 365 days later.

Now and then, New York was awash in champagne, albeit the bootleg variety during Prohibition. On October 8, 1927, the Yankees of Murderers Row fame won the World Series; 57 days later, the Giants won their first NFL championship (clinched in the regular season, as there was no playoff system yet in place); 132 days after that, the Rangers skated off with their first Stanley Cup; and 178 days after that, the Yankees won the World Series again. In just over a year, New York raised four banners in three sports.

Other than a pair of four-year droughts (1928-1932; 1943-1947) and one lasting three years (1958-1961), New York never had to go without for more than approximately ten minutes. That four-decade bounty came to an end with the last Yankee world championship of its dynasty epoch, won on October 16, 1962.

Then came a drought worthy of the name. The 1960s may have been a good time for surf music, but New York sports teams were collectively wiping out. Even though we had seven entries playing four sports in six professional leagues, there was no strength in numbers. The baseball Giants and Dodgers vamoosed west in 1957, but we had already gained the Knicks (founded 1946) and were about to add the Titans/Jets (1960), the Mets (1962) and the New Jersey Americans (1967), a basketball bunch that bounced to Long Island and became the Nets a year later. Yet even with all those new franchises joining the Yankees, the NFL Giants and the Rangers, we couldn’t win a single championship as a metropolis. It took until January 12, 1969 — a span of 2,280 days — for the AFL Jets to trump the NFL Colts and end the drought that had been so deeply entrenched during sports’ expansion boom.

Once the championship boom hit New York, it exploded in earnest. Only 277 days after Joe Namath made good on his Super Bowl III guarantee, the Mets won the World Series. And only 204 days beyond that blue-and-orange letter date of October 16, 1969, the Knicks were crowned NBA champions, on May 8, 1970. Another Knick title was registered just over three years later. A year after that, it was the Nets’ turn to make New York proud. Dr. J and his teammates turned the ABA trick again two years later.

Then the New York Nets (like their league) ceased to exist as such and no New York or New York-ish professional basketball championship has been secured since May 13, 1976 — not in Northern New Jersey, not in Manhattan and not in Brooklyn. But the sports championships kept coming to New York in the late 1970s, as the Yankees won a pair of World Series in back-to-back fashion in ’77 and ’78 (while the Cosmos were winning the briefly big-time Soccer Bowl in the same two seasons). As the 1980s dawned, the Islanders, formed in 1972, kept New York’s championship thirst slaked with four consecutive Stanley Cups.

After the last of those ice hockey chalices was hoisted in good old Uniondale, New York went dry for 1,259 days, which represented the longest drought to date of the post-Namath period. Who came to New York’s rescue while the Islanders, Rangers, Devils (who showed up in East Rutherford in 1982), Knicks, Nets, Jets, Giants and Yankees came up perennially short after May 17, 1983?

Why, the New York Mets! They won the World Series on October 27, 1986, and they provided such an inspirational example, the Giants went out and won Super Bowl XXI on January 25, 1987, exactly 90 days later. It made for the fourth-shortest championship drought in New York sports history, the briefest since 1956.

Things dried up again from there, though. The Giants had to pick up where they left off 1,463 days earlier by taking Super Bowl XXV on January 27, 1991. The Rangers kicked in a Cup 1,234 days after that, with the Devils matching their feat another 370 days hence. New York/New Jersey didn’t have to do a lot of waiting in the years ahead, with four baseball and two hockey championships falling the area’s way between 1996 and 2003.

Then it grew dry again, as there’d be a 1,700-day void between the Devils’ third cup (June 9, 2003) and the Giants’ third Super Bowl (February 3, 2008); New York had not waited that long for a championship since Broadway Joe’s signature moment. There’d be a World Series won by somebody local on November 4, 2009, then that fourth Giants Super Bowl on February 5, 2012, snapping a champless stretch of 1,157 days, a figure we’ve since surpassed as we wait and wait and wait for another…as we wait for the one we really want.

All told, there were 59 major professional sports championships won by eleven franchises situated in the New York City area between 1905 and 2012. New York needs a 60th in 2015. There’s only one New York team that can bring it home this calendar year.

There’s nobody else to whom we’d rather assign this vital task.

by Greg Prince on 5 October 2015 3:34 am Maybe all the Mets needed was a little sunshine. The sun makes living things grow. The Mets appeared to be the opposite of a living thing since departing Cincinnati with a division title stuffed in their luggage. Perhaps they were under the impression they had entered the afterlife.

Not quite. They had only qualified for it. There was a little business left to be taken care of back on earth, a little pulse to be shown. They proceeded to play five games under cover of either darkness or clouds. The results reflected the gloom.

Sunday the sun came out. And so did the Mets, who did just enough to make the rest of us shine. Heaven no longer waits. It arrives unencumbered, at a time to be announced, this Friday at Dodger Stadium.

Funny thing about depositing yourself at a sun-kissed ballpark for the last few hours it was supposed to be open for the year. You forget your problems. You forget your team’s problems. You forget the total lack of scoring from the several games before. You forget the total lack of hits from the game directly before. You remember that even though the game you’re at was slated to mark the end of yet another season, this year it serves as a gateway to something potentially divine.

Under the Sunday sun at Citi Field, in Game 162, the Mets beat the Nationals, 1-0. One run more than their opponent — any opponent at this point — was all we needed to burnish our brightness. We got it. We got it against the Nationals, which was a nice and I’d say necessary boost for our collective self-esteem. The Nationals lost and went home. That’s where they were headed anyway, but it was better to send them away emptyhanded. Their disappearance from October before October really gets going provided a healthy reminder that it is the Mets who are sticking around to take a bite out of the meat of the month.

The Mets are going on to play more baseball. They start the new fall season Friday. They were the breakout hit of the summer. We’ll see how their act plays in prime time. Right now just knowing that they’ll be there to tune in to is pretty special. It was special knowing that on Sunday.

Ah, Sunday. Closing Day. It’s my thing every year at the end of the baseball year. I’ve come to cherish it more than Opening Day. It’s when I reflect a lot and mourn a little and appreciate a ton. But what about the rare year like this one when the Day in question is less about Closing and more about keeping the gate ajar?

What one sacrifices in sense of closure is more than made up for by the sensation of anticipation. My gosh, knowing the Mets and Citi Field will remain open for a while longer, maybe a significant while longer, doesn’t detract from Closing Day at all. It adds a whole savory dimension to the experience.

Thus, I wasn’t my usual melancholy self on the train ride in Sunday. I wasn’t kissing, hugging or heartily handshaking the season and its inhabitants goodbye. I wasn’t slumped into my seat at the end as I tend to be when the last out is recorded. I was light on my toes in my head all Closing Day long.

There was still the pageantry I arrange for myself on the occasion of the final regularly scheduled home game, a date I have now kept with the Mets for 21 consecutive seasons, 23 in all. There was the Chapman tailgate extraordinaire, this year with a Seaver Vineyards-supplied toast to a division title just won and a division series just ahead. There was a dime (or more) dropped on a t-shirt, a pennant and a pin that confirms the Mets really are champions of something. Usually Stephanie and I search the team store for clearance items. This year the shelves were stocked with new merchandise. It was no bargain, but I can’t question the value.

We walked the field level one more time. We said hi to people we see mostly at Citi Field. People who see us mostly at Citi Field said hi to us. We stopped in our tracks when the PA gave me what I’d been wanting to hear since April: Bobby Darin welcoming us to “Sunday In New York,” a song that had been a Sunday staple in Flushing dating back to early in the century. I thought they stopped playing it, the way they stopped playing “Takin’ Care Of Business” after Mets wins. I was willing to move on from BTO to Ace Frehley in the name of changing our luck, but I’d been missing Bobby Darin something awful.

“If you’ve got troubles/Just take them out for a walk/They’ll burst like bubbles/In the fun of a Sunday in New York.” I’ve got troubles. We’ve all got troubles. The Mets aren’t one of them. Sometimes we act as if they are. Even when we’ve had an appointment with the Dodgers guaranteed for more than a week we could, amid the clouds and the darkness, convince ourselves the sky was if not falling, then drifting dangerously downward.

On Closing Day, with the sun prominent and friends along the trail and postseason logos in evidence, there was no trouble at Citi Field. There were no hits for the Nationals for most of seven innings, albeit without the drama Max Scherzer provided Saturday night. Terry Collins was changing pitchers like a neurotic foot changes socks, yet no arm — not deGrom’s, not Colon’s, not Verrett’s and, until it finally did so a little flukily, not Niese’s — gave up a Washington base knock. Then the regular bullpen guys Reed and Clippard resumed keeping the Nats hit out of luck.

The Mets who hadn’t scored since Cincinnati (or so it seemed) didn’t score until the eighth, when Curtis Granderson hit a ball over a fence. But they did score and they had an entire run more than the Nats. See? No trouble. It was 1-0, Jeurys Familia coming on for the save that would tie Armando Benitez’s single-season mark of 43. Two outs were quickly recorded.

Finally, it was Familia versus Bryce Harper to end it. Or not end it. Harper stroked the first pristine hit of the day, a double to left. Or was it a single and he was out on Michael Conforto’s bullet of a throw to second? Harper was called safe. Collins challenged. Good move, aesthetics notwithstanding. Let Terry get tactical. It’s not like those challenges can be saved for another day.

A replay was watched from a thousand angles. Harper was ruled safe again. Harper is a superb player. I hope someday the relationship between his excellence and our distaste for it has some edge taken off of it. I didn’t like that after he was hit by a pitch Saturday afternoon and briefly writhed in pain that he was hooted on his way to first. Karma doesn’t care for that reaction. Karma was disgusted when Mets fans cheered Kirk Gibson pulling up lame at second base in the 1988 NLCS. See where that got us. Saturday Harper, writhing shaken off, hit the home run that won the day game. I wasn’t surprised. Boo Bryce, but hold the malice. Trust me. It will work better for us in the long run.

Anyway, Bryce was on second and I guess he’s technically if not physically still there. Jeurys left him on base when he flied Jayson Werth to center to end the regular season. A Met had notched a 43rd save for the first time since 2001, which was when “Sunday in New York” entered my consciousness. The Mets, sporting a spiffy 90-72 record, won a 1-0 game for the first time in 2015, a veritable unicorn-style event for a season that featured back-to-back 14-9 affairs at the offense-fueled height of August. Better late than never to make with the pitching, defense and one-run homer.

The last time the Mets won, 1-0, on Closing Day was 1995, the year I began my current last scheduled home game attendance streak. They beat the Braves that Sunday in New York. Bobby Cox started John Smoltz and pulled him after five the way Collins removed Jacob deGrom after four. It was just a tuneup for the N.L. East champs. Their ticket to the postseason indelibly stamped, they were swept by the Mets that weekend. Those same Braves were so burdened by those three straight losses that they went out and won the World Series four weekends later.

You never know how these things will unfold, but I’ll happily take the 1-0 win in 2015 just as I happily took the 1-0 win in 1995. Strange habit I’ve developed. When I go to see the Mets play, I leave happier if I’ve seen the Mets win.

Connoisseurs of Closing Day know the day isn’t done just because the game is over. You stand and you applaud and you wait to see what will happen next. It used to be the best you could hope for was a montage of video clips from the season we’d just persevered through and maybe a cluster of Mets gathering outside their dugout and tossing a few wristbands and well wishes to the fans nearby.

This time we got something more. We got something I’d never previously seen a Mets team do.

The Mets, every wonderful one of ’em, transformed themselves into a human highlight film. They came out en masse and they waved, but they didn’t stop there. They jogged the circumference of the field. They greeted every segment of the stadium. It would have been easy enough to make a beeline to the 7 Line Army out in center and then a beeline right back into their clubhouse. The 7 Liners are the most visible cluster of fans at any game they hold down seats and they can’t help but attract the most attention.

These Mets, though, symbolically recognized everybody who came out to recognize them. It was such a simple gesture, yet it ran so deep. The manager circled the field. The captain circled the field (and later grabbed a microphone in order to share a few gratitude-laced sentiments with us before encouraging all of us, “Let’s go beat L.A.”). Everybody from Yoenis Cespedes to everybody who isn’t Yoenis Cespedes circled the field. The effect was electric. It was like they, the players, knew who we were and how much we care; like they knew we show up to see them across 81 home games plus however many times some of us hit the road to lend them support. All we ask for in the course of the season is that the hitters pile up runs and the pitchers allow almost none. We wouldn’t have thought of asking for this.

Yet they thought to give it to us. It was a splendid moment, maybe never to be repeated again in my lifetime. Or it will be repeated following another few clinchings and become Met tradition, like the video montage used to be, like “Sunday In New York” used to be. Who knows? I know I won’t forget it.

That’s my leitmotif every Closing Day, not forgetting because there’s so much to remember, so much to tie up and take into winter. This Closing Day, however, winter was nowhere in sight, ballpark chill notwithstanding. This Closing Day we bundled and stacked only so many memories. We are privileged to be able to add to them beginning this Friday in Los Angeles. It’s a shame Games One and Two and potentially Five won’t take place at Citi Field. It’s a blessing that our number of games remaining isn’t down to zero.

Here’s to the 2015 that’s happened. Here’s to the 2015 still to come.

by Jason Fry on 4 October 2015 2:56 am Back in June, Emily and I decided that a lovely summer night would be made even better by our attending a ballgame. So we did … and watched the Mets get no-hit by Chris Heston and the San Francisco Giants.

I grumbled and groaned for competitive and aesthetic reasons. The competitive reasons for not wanting my team to be no-hit and lose are, I’ll assume, obvious. The aesthetic reasons? From our perch in the Promenade we couldn’t see how well Heston was mixing or locating his pitches. All we saw was Met after Met after Met arriving at the plate, doing nothing of offensive note and departing — until the Giants were whooping it up.

Last night, Emily and I decided that though it was not a lovely night — in fact, it was windy, cold and thoroughly vile — the best way for us to spend our evening was by attending a ballgame. So we did … and watched the Mets get no-hit by Max Scherzer and the Washington Nationals.

Yes really. I don’t go that often — I think I attended around eight games this year. The Mets don’t get no-hit that often — I know that was the eighth time it’s happened to them. And yet there my wife and I were, stranded once again at the intersection of You’ve Got to Be Kidding Me and What the Hell?

If this is luck, someone else can have it.

At least there were some differences between the two nights. Our vantage point for Scherzer’s outing wasn’t that much better than it was for Heston’s — they were perfectly nice seats but unless you’re in the padded Shake Shack area you can’t really speak with authority about movement on pitches or working hitters or any of the stuff you can geek out about if you’re in front of an HDTV. (This is probably one reason I don’t go to Citi Field as often as I should.) But even from where we were, we could see the life on Scherzer’s pitches, and the Met hitters trying to steel themselves in the batter’s box, and we could tell that no one in orange and blue could catch up to what he was bringing. You needed a close-up view to appreciate how Heston was succeeding, but Scherzer’s performance was amazing to witness from any seat in the house.

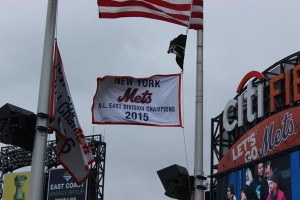

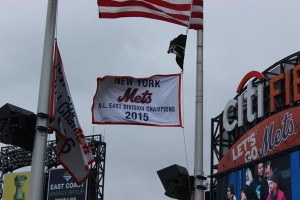

Competitively it came with a silver lining too. Believe it or not, being no-hit does not mean you immediately surrender 10 games in the standings. The Mets are still National League East champs, as their new flag accurately states — a fact that will come as news to the hysterical wing of Mets Twitter, and that was lost on the dopey, dyspeptic fans surrounding me and my wife last night.

Our section suggested the Mets got the promos wrong and Saturday was actually Wet Blanket Night. The guy in front of us was outraged at watching the Mets’ JV get throttled by one of the best pitchers in baseball on one of the most dominant nights of his life. The guy behind us was merely irritated, but perhaps that’s because he was busily mansplaining the game of baseball to his female companions, whose air of weary patience suggested this wasn’t a new experience. (Most of what he told them was wrong, which I think would surprise only him.) As for the guy at the end of our row screeching in outrage whenever Harvey threw a ball off the plate on an 0-2 count, I can’t even. I alternated wanting to throttle the lot of them with wanting to scream DUDES WE ARE GOING TO THE POSTSEASON, WE BEAT MAX SCHERZER WHEN IT MATTERED, SO CALM THE FUCK DOWN ALREADY.

The Mets are playing flat? I’ve noticed. Heck, it’s been impossible to miss. I’m not that concerned — one hallmark of the 2015 team has been routinely defying whatever it is we think we know about them. The Mets looked befuddled and tired against the Marlins ahead of their showdown with the Nats — and then effectively ended Washington’s season. They followed a grumble-inducing 3-6 homestand with annihilating the Reds. After Sunday’s game they’ll have four days off. It’s plenty of time to reset. And think of it this way: If the Met bats were hot, fans would be starting cars in garages while scribbling notes explaining that the layoff will obviously cause those bats to go cold.

(By the way, another team suffered the indignity of being no-hit twice this year. That’s right, it was the Dodgers.)

When the NLDS begins on Friday, the Dodgers will have home-field advantage. Eh, so what? If you want me to worry, bring up Juan Uribe‘s sternum and Steven Matz‘s back and Jon Niese‘s learning curve as a reliever. Clayton Kershaw and Zack Greinke are no picnic whether the shadows are between the hitter and the mound or on the other side of the planet. But our starters aren’t exactly a day at the beach either — give me today’s pitching performances from Harvey and Noah Syndergaard and I’ll take my chances with the Dodgers.

And let’s not forget the bigger picture. I wrote this a couple of days back, but it can’t be emphasized enough: The postseason is a crapshoot, a trio of exhibition series. Billy Beane famously remarked that “my shit doesn’t work in the playoffs. My job is to get us to the playoffs.”

Well, job done — and oh what a joyous mission accomplished. On Sunday that ends and we’ll wait for baseball’s autumn exhibition games to begin. I don’t know if we’ll get an ecstatic month that brings sweet memories for a lifetime or a few days of extra baseball followed by disappointment and winter. Either’s possible. If you’re tempted to make any prediction more specific than that, stop and remember the less-famous second half of Beane’s quote about getting to the playoffs: “What happens after that is fucking luck.”

by Greg Prince on 3 October 2015 4:59 pm “2015 is over as far contending for a postseason spot goes, and we should just admit it.”

—A post on a blog about a team, June 24

The Mets lost their fourth consecutive game Saturday afternoon. They’re still invited to the playoffs. That doesn’t get revoked on account of style points. But the style they are finishing the regular season in should have gone out of style in June.

June was the last time they lost as many as four in a row. June was when we had to remind ourselves, once the losing streak reached seven, that the Mets would someday win a game again. It seemed worth mentioning because it didn’t seem like a sure thing.

The Mets then went out and commenced to win a whole lot. From a nadir of 36-37, they roared to 89-67. If the “89” looks familiar, that’s the number of wins they’ve been stuck at since last Sunday, which was the day after they clinched that invitation to the playoffs. Again, it’s still valid. Hard to believe, based on the activities of the past six days. These games count, but they count differently from the games that preceded last Sunday. They’re in the standings and they help determine where future games will be played, but their outcome won’t prevent those future games from being played.

The invitation is still valid. We’re clear on that, right? The Mets are still playing as of October 9. The Mets are still 0-0 as of October 9, regardless that they’re 0-4 since September 29. The Mets hoisted a divisional championship flag Saturday afternoon prior to their fourth consecutive loss. Long may it wave…and soon may it be embellished to reflect further accomplishment.

OK. That said, this is mostly lifeless baseball the Mets are playing and they should stop it. Just stop it. We can be only so sophisticated about it for only so long. We’d like to stop being sophisticated about it tonight. Use the second half of this day-night doubleheader to humor us with a 90th win. That would look better than 89. Keeping pace with the Dodgers for home field would look better, too, whether it actually matters or not. Let’s pretend it does. Warm your patrons with something more than a fleece blanket.

Make double plays. Hit with runners on base. Confound the winds. Everybody be as much of a credit to your uniform as Noah Syndergaard (7 IP, 2 H, 1 BB, 1 R, 10 SO) was to his during the day portion. Embarrass the Nationals, if just for recent old time’s sake. Go on Mets, play like champions. That’s what you are.

Fill your between-games void by listening to me join Mike Silva on Weekend Watchdogs. About an hour-twenty in, Mike asks me about the Mets going to the postseason and I tell him…hell, hear it for yourself.

by Jason Fry on 1 October 2015 11:56 pm Several times this winter, I’ll sigh and tell my wife how I’d do anything to watch any baseball game — even say, a June snoozer pitting the Brewers against the D-Backs. I’ll mean it, of course — nothing comforts me while staring out the window and waiting for spring. Not winter ball, not Mets Classics, not hot-stove talk, not tending to The Holy Books.

Still, if I had a choice between watching today’s Mets-Phillies game and sulking at the window, I actually think I’d sulk by the window.

The game clocked in at a tidy 2:23 but seemed to take three times that long. Sean Gilmartin was fine but Jerad Eickhoff was better, Darin Ruf hit a massive homer, no Met other than Kirk Nieuwenhuis hit much of anything. Plus it was freezing and I think the uniformed personnel may have outnumbered the spectators.

The amazing thing? I almost went to this game. I hit a big book deadline on Wednesday and have a couple of days before I have to move on to the next project. On Wednesday night, with a little too much prosecco imbibed, it seemed like a grand idea to take the morning train down to Philadelphia for a Mets matinee. This morning, thank God, it seemed like an excess of fuss.

Proof that not every opportunity passed up is one you’ll regret. (Or, as someone put it on Twitter, this was my Carlos Gomez trade.)

So here are the Mets, freshly swept by the Phillies but not booted out of their division title by way of punishment, trying to get all hands healthy and unsuspended and used to bullpen work. They’re tied with the Dodgers for home-field advantage in the NLDS, though recall that a tie goes to the guys in orange and blue. The next three days will settle that, weather permitting. (And if we think a Monday or Tuesday extra game would be inconvenient bordering on cruel, just think how the Nats and their fans would feel about it.)

It would be good to finish even with or ahead of the Dodgers, seeing how they’re much better at Dodger Stadium. But it would be better, I think, to be as healed as possible. We don’t like to admit it, but three games out of five is a crapshoot — just as we don’t like to admit that the entire postseason is a crapshoot.

If the Dodgers get home-field advantage, Mets fandom will of course have a collective stroke. But then that’s going to happen anyway over Yoenis Cespedes‘s fingers and Steven Matz‘s back and Wilmer Flores‘s back and Juan Uribe‘s sternum and Matt Harvey‘s innings and whether it’s Gilmartin or Erik Goeddel or Jon Niese or Bartolo Colon and Juan Lagares or Nieuwenhuis or Eric Young Jr. And Twitter will be the frantic heart monitor paging nurses and doctors with electrified paddles.

Until next Friday and first pitch at a park to be determined, it’s silly season. Which, don’t get me wrong, is a whole heckuva lot better than stale season, when you’re trying to convince yourself that the last dregs of a losing season are to be savored even though you’re secretly ready for a break from baseball. But it’s still silly. We’ll play life-and-death games in a week, but that week of waiting is going to feel even longer than this lost series in Philadelphia did.

So hang in there, rest up, and be kind to each other. And, of course, Let’s Go Mets.

by Greg Prince on 1 October 2015 9:24 am Pour yourself two fingers of your favorite morning beverage (or perhaps something stronger; no judgments) and drink to the digital flexibility of Yoenis Cespedes…and to the postseason not being over before it begins.

Cespedes is nursing a bruise that covers his left ring and middle fingers after his hand got in the way of a Justin De Fratus pitch in the third inning of Wednesday night’s Citizens Bank slog. As he knelt in obvious pain, the 2015 NLDS flashed before our eyes and it was over in a blink. When word emerged three innings later that the X-ray review ruled it a contusion — and that contusion is a fancy word for bruise — it appeared the republic would survive to fight another day.

Let’s hope Yoenis followed Keith Hernandez’s sage advice and iced the fudge out of those fingers overnight. And let’s hope Cespedes responds to this HBP the way characters on your Gilligan’s Island-type sitcoms would respond when conked on the noggin a second time. Our slugger/savior, it will be recalled, was merrily bopping along, having blasted 17 home runs in just over a month’s time (enough to lead nine previous Met squads in homers over the course of their full seasons), when he took a pitch to the hip on September 15. He hasn’t homered since.

“If hitting him with a pitch turned off his power,” the Professor might have theorized to the Skipper, “Hitting him again might turn it back on. I know it’s unorthodox, but it may be our only hope.” At which point the Skipper apologizes to his Little Buddy before whapping him on the coconut with a coconut. And somehow the radio works again, even if you probably can’t get WOR very well in the middle of the Pacific (or many other places) and even if nobody is rescued until somebody thinks to make a TV movie more than a decade later.

The crew of the S.S. Minnow set out on a three-hour cruise, or for one hour fewer than Wednesday night’s ball of contusion lasted. Otherwise, the whole affair seemed to be an uncanny remake of The Flushing Globetrotters on Gilligan’s Island. A tropical storm loomed; every Mets baserunner from the second inning onward wound up a castaway; the “I’m telling you, Steven Matz is going to be seaworthy when the time comes” plot point sprang another leak; and Hansel Robles portrayed a pretty unconvincing headhunter.

Hard to believe the episode started frothily enough, with the Mets plastering five runs on the scoreboard in the top of the first, as Daniel Murphy and Michael Conforto each took Alec Asher on a tour of the many lovely areas beyond the Citizens Bank Park outfield fence. At 5-0, it shaped up as the most laughable of laughers. The audience simply assumed that against the bottom-dwelling Phillies we’d soon have a 90th win (not quite); an additional leg up for home field advantage (nope, though the Dodgers lost, so we still lead that mini-race by one length); and a relaxing evening to enjoy that rare state of grace between clinching a title and battling for a bigger one (alas, Wednesday’s 7-5 loss dropped the Mets’ lifetime record to 34-17 in regular-season contests they’ve played as a playoff qualifier — why, yes, there is a stat for everything).

When the shining highlight of your baseball game is your best player being hit in the hand but not so badly that anything was broken, it can be definitively stated that nothing good happened. Except that the game eventually ended. That was pretty good. And a week from today, should Cespedes find himself gripping a bat free of pain in playoff competition, that will be a victory.

by Jason Fry on 30 September 2015 2:18 am I’ll admit this: I never thought Fred Wilpon’s line about meaningful games in September was so embarrassing. Granted, I would have revised the line to “meaningful games in the last week of September.” If you’re playing those, your team’s kept you scoreboard watching, hoping and dreaming almost until the end, which I’ll always sign up for. But even without my suggested tweak, I thought Wilpon’s formulation was the product of baseball wisdom more fans should internalize: winning is more about luck than we like to imagine, a season can be great even without a World Series trophy at the end, and a sense of entitlement makes you a toxic shithead. If you disagree with all that, there’s a team in the Bronx tailor-made for you.

But this week is a reminder of something else: Meaningless September games can be just fine. Not the meaningless kind where you try to convince yourself that a second-tier prospect’s garbage-time quality start will mean great things in a couple of years, but the meaningless kind we’re playing now. In Philadelphia tonight, the Mets lost. Bartolo Colon and Jon Niese weren’t great, Carlos Torres returned and looked OK, Lucas Duda hit a pair of home runs, and brothers Travis d’Arnaud and Chase d’Arnaud seemed to have a pleasant time gabbing at home plate. That’s about it.

If you weren’t paying attention, you get a mulligan. The Mets are auditioning starters for bullpen roles, trying to figure out how to fill the last couple of roster spots, and looking to strike a balance between rust and rest. The only thing left to play for is home-field advantage over the Dodgers, which would be nice but isn’t worth an all-out sprint; the team also has to face the possibility that they may not get to play baseball for a ridiculously long time, what with multiple fronts and a hurricane converging on the East Coast.

In all likelihood nothing that happens this week will be remembered come October 9, which is fine. Baseball’s one of humanity’s greatest artistic achievements, but there’s nothing wrong with a bit of a break from it. This is a fine week to take your spouse out to dinner, take your kids to the movies, or pursue whatever evening plan normally gets neglected between April and October. Next month you’re going to be frantic and delirious and terrified and delighted and mostly tired, for at least a long weekend and hopefully the whole month. So rest up, y’hear?

This concludes the Mets-related portion of today’s blog post. Now I’m going to tell you about my adventures watching baseball in Missouri.

A few weeks ago I noticed that I had a $200 Delta credit that was about to expire. After various ideas proved unworkable, I hit upon one I should have thought of earlier: I’d go to one of the 11 big-league ballparks I’d never visited before.

I eliminated Pittsburgh because Emily wants to go. I tossed out Detroit, Cleveland and Cincinnati because I’ve always imagined combining them with Pittsburgh in a baseball great circle route some summer. I dropped Milwaukee and New Comiskey because Emily wants to go to Wrigley (I went last year), and it and the other two could be combined in a single trip.

That left Minnesota, Texas, Miami, Kansas City and St. Louis. I started checking Delta airfares and schedules and StubHub, and then realized that if I was willing to drive for a few hours, I could knock off Kansas City and St. Louis in one trip, with enough room to pursue a little genealogical exploration as well.

Done — and for surprisingly little money. The credit took care of most of the airfare, even with me flying into K.C. and out of St. Louis. The one-way car rental was reasonable. I used points for hotel rooms. And I found pretty great seats that weren’t crazily expensive, a surprise given both teams were headed for the postseason.

My biggest worry was that the Mets would falter and I’d be stuck halfway across the country freaking out and blowing my data plan watching At Bat. But that didn’t happen either — I returned to a magic number of one.

So, the parks.

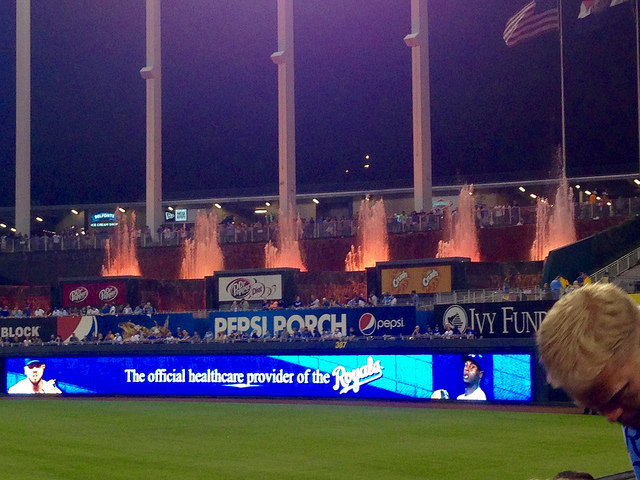

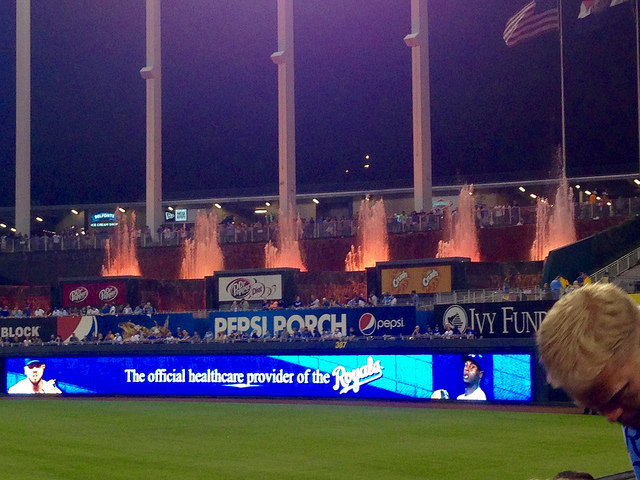

Kauffman Stadium dates back to 1973, though it got an extensive renovation a few years ago. It’s not bad for what it is — a pretty nice park from an era of lousy park design, given a thoughtful coat of paint.

Which isn’t enormous praise, granted. The biggest problem is one that can’t be solved: Kauffman isn’t in Kansas City proper, but plopped down east of the city next to Arrowhead Stadium and surrounded by highways. Behind those iconic fountains (about which more in a bit) are some statues of Royals greats, a few nondescript eateries (none of which feature local barbeque, for some absurd reason), and then this view:

Yeah, that’s not inspiring. People tailgate like fiends before Royals games because there is absolutely nowhere else to go.

But the park itself isn’t bad. The fountains are a bit doofy — after hearing about them for years, I was as underwhelmed as Greg to see them in action, which is probably a reflection of my enthusiasm for fountains rather than any failure of the park’s. (I don’t know what the world’s greatest fountain is, but I bet it’s a bunch of pipes that make water go up.)

But I liked the big gold crown atop the massive video board, and the Royals flags snapping in the wind, and even the arches on the concourse.

No, that isn’t old-timey brickwork or black iron. It’s just a bunch of concrete. But for 1973 it isn’t bad — Kauffman could have been some brutalist doughnut horror, but it has some nice sweeping angles and good bones that elevate it above such parks.

One thing that might have colored my perceptions is the fans are great. My pal Sterling and I were sitting in good seats behind first base, and we happened to be there on the night the Royals clinched the American League Central, which you might argue is the kind of thing that leads to grade inflation. And perhaps you’re right. But the folks around us in the good seats were into it from the first pitch, in a way the folks in a lot of good seats aren’t. It was rare to see anyone not clad in royal blue, and I was surrounded by baseball conversations all night.

Kauffman’s stadium-operations folks set the right tone as well, seemingly determined to get every cute kid a few seconds on the video screen and to find every banner exhorting the Royals to a division title, looking for romantic attention from Eric Hosmer, or both. The Royals won and mobbed each other on the field, the fans cheered and high-fived and took inept cellphone videos from the stands (I looked at mine and deleted it), and then everybody wandered out into the vast parking lot and waited in their cars to get somewhere else. But they seemed pretty happy doing it, and I found I felt the same way.

The next night brought me to Busch Stadium, a visit that will need a few asterisks upfront:

- The Cardinals are far from my favorite team.

- St. Louis is far from my favorite town. (Well, except for the bourbon shake at Baileys’ Range, which is awesome.)

- I was there last year but the Cardinals weren’t, which I resented even though it’s nobody’s fault.

Busch Stadium opened in 2006, the third park to bear the name (here’s Greg on Busch II), and if you’ve been to more than a couple of HOK parks you’ll instantly recognize this one — brick and arches, ironwork, a level that’s suites-only, fancy seats with waiter service behind home plate, quirky seating areas in the outfield, a gathering place for families and big parties on the top deck behind home plate. None of this is a bad thing — heck, I just described Citi Field. But Citi’s a lot more distinctive than Busch, somehow. Busch feels like it was assembled by a committee flipping through a Retro Stadium pattern book.

It does have some nice touches. I liked the Scoreboard Patio seating area in center field, and the statues of Cardinal stars outside (including Jack Buck), and the place is properly festooned with Cardinalia no matter where you are. Walking up the stairs you find images of team logos, and the signs for sections are topped with cardinals in various poses. Even this Mets fan found those pretty adorable.

The customer service at Busch is also top-notch. There are people everywhere to help you, and they’ve been trained to actually do that, rather than assume you’re the enemy. There are about a billion places to get something to eat, meaning lines are pretty short even with a packed house. No matter where you are there’s a TV showing the game or you can hear the radio feed, which is the kind of simple thing a lot of parks can’t manage. And the out-of-town scoreboard is great, packing a lot of information into an easy-to-read space.

But there’s also a certain too muchness going on. For example, that thing above is Ballpark Village, an appendage of Busch that’s basically a TGI Friday’s on steroids that only serves Anheuser-Busch products. (If that sounds great to you, we probably shouldn’t hang out.) Besides the invocation of fandom as a nation, which works a lot better as ironic shorthand than as a massive expanse of neon, that AT&T Rooftop contraption is a blatant ripoff of Wrigley Field’s neighbors, which you’d think the Cardinals would have shied from copying. And I can count three Ford logos and three Budweiser ones in that picture, which is approximately 0.00000000000000001% of the number of each you’ll find at Busch. St. Louis feels like a company town, the Cardinals feel like a company team, and Busch Stadium feels like a company headquarters.

I don’t mean to be too hard on Busch. It’s a perfectly nice park. I enjoyed myself and the fireworks show after the Cardinals lost, then took myself across the street to the Hilton at the Ballpark, which has pictures of Cardinals in every room. I had a perfectly good time — as I will most anywhere you give me a beer, something to eat and let me watch baseball. But I was relieved when the next day was Cardinal-free, and I don’t think that was just the Mets fan in me.

by Greg Prince on 28 September 2015 8:49 pm  At last, I get the picture. (Photo by Andrew Richter) Welcome to FAFIF Turns Ten, the long dormant milestone-anniversary series in which we consider anew some of the topics that defined Mets baseball during our first decade of blogging. In this, the tenth of ten installments, we make one last trip to our spiritual home.

Last week, I was taking the LIRR to the Mets game, which for me ultimately involves a change at Woodside, which sometimes involves a change at Jamaica. I’m generally on top of the changes that are involved, but sometimes a conductor looks at my ten-trip ticket — which identifies my destination as Penn Station — and asks if I’m staying on all the way to the end.

“I’m going to Shea,” I say. I always say that if a Mets game is involved. It’s been my own little act of defiance for seven seasons when there is no Shea to go to. It usually sounds good coming out of my mouth and going in my ear. Shea, I like to say, is a state of mind that transcends a demolished physical plant. Mets-Willets Point is bureaucratic and cumbersome. Citi Field is free advertising. Shea is Shea.

I change at Jamaica. I change at Woodside. But I don’t change so easily otherwise.

Yet when I said, “I’m going to Shea,” on Monday night, September 21, 2015, it didn’t sound right at all. It sounded out like I got on the wrong train in the wrong year. It momentarily confused the conductor. It may have permanently broken me of my habit.

So here, on this particular ride, for what I’m pretty sure will be the last time, I’m going to Shea. I’m certain it will come up in conversation again, but never again will I head there so purposefully.

***

You remember Shea, don’t you?

“…[A] picturesque, elaborate and once widely celebrated establishment. I expect some of you will know it. It was offseason, and by that time decidedly out of fashion, and it had already begun its descent into shabbiness and eventual demolition.”

Wes Anderson did not write the above paragraph to describe Shea Stadium, circa 2008, but he could have. Our Grand Budapest Hotel of a ballpark was doomed. We still visited, but we wouldn’t for much longer. But I kept going long after 2008, at least in my mind and on these pages. It was my default setting for where to find Mets baseball, past and stubbornly present.

Lately I don’t go there so much. It’s not too crowded.

Directors love referring to their settings as “another character” in their movies. Sometimes the locale for their story is as important as any actual character, but I guess they have to stop short of saying that so as not to offend their human actors.

I don’t have such concerns, thus I can say that the primary non-autobiographical character in the first decade-plus in the life of this blog to date, certainly from my perspective, was Shea Stadium. Even though it’s a place. Even though it ceased to serve as an actual setting for Mets baseball seven years ago tonight. Even though its last physical traces were swept from the landscape more than six years ago.

Shea defined the stories I sought to tell for the first four years of Faith and Fear. It informed the subtext of much of what I wrote in the six years that followed. It lingered prominently in my Met consciousness until fairly recently, when I came to accept once and for all that it’s not coming back.

Which, at last, I’m fine with. Hence, to Shea I say a belated good night. Figuratively, emotionally, whatever.

It was hard to miss Shea’s literal lights-out on September 28, 2008, and the christening of its successor facility come April 13, 2009, wasn’t exactly conducted secretly, so, y’know, I got the memo. Still, there was something about the latter days of Shea that wouldn’t let go of me.

Factors that contributed to Shea Stadium’s continued hold on my psyche well into 2015:

1) Citi Field’s incognito phase, during which your guess was as good as anybody’s as to who played home games there.

2) Citi Field’s inability to sustain excitement.

3) The Mets’ inability to generate sustainable excitement inside Citi Field.

4) The relative recency of 2008 even as 2009 became 2010, and 2010 became 2011, and chronologically so on. (When a person passes a certain age, the use of “a few years ago” can mean anything from a few to a whole lot.)

5) Video footage from 2008 appearing a damn sight clearer and crisper than the film clips of 1963. If Shea Stadium at the end wasn’t all grainy and splotchy like the Polo Grounds apparently was, how is it possible that it was not still standing?

6) MSG repeatedly showing The Last Play At Shea and Live At Shea Stadium, wherein Billy Joel performs, crowds cheer and surely Paul McCartney is returning for one more encore. Like game action from 2008, but more so, it looked, sounded and felt far too contemporary to have taken place in a building long gone.

7) Wishful thinking. As predicted here, Shea Stadium grew in stature after its demise. Those who didn’t care for it had nothing to complain about. Those who figured they’d miss it didn’t stop missing it, and since there’s no antidote to absence, they…we were more than happy to invest it with supreme qualities it probably wouldn’t contain if it were still around.

8) Symbolism. Shea Stadium was where we had fun. Ergo, it was always fun and nothing but fun. It was where Joan Payson and Nelson Doubleday bought us whatever we needed and Tom Seaver pitched two-hit shutouts every other day while Darryl Strawberry went deep daily and K’s fluttered from above as Doc Gooden struck out side after side and Mike Piazza never, ever grounded into a double play and the Sign Man offered wry commentary and Jane Jarvis led us in the Mexican Hat Dance and Rheingold was on the house and each and every one of us was a guest on Kiner’s Korner, where we quipped with Bud Harrelson about our winning Banner Day entry that praised Ron Swoboda to high heavens. Oh, and it was always packed. We are more than happy to invest Shea Stadium with supreme qualities it displayed sometimes, maybe ofttimes, but, let’s be honest, not all the time.

Our happiest recaps remain the ones we’ve constructed in our mind. Those are the ones that refuse to be dismantled by demolition machinery. That’s OK. We are the sentimental ones.

***

“I’ve crossed that fine line from theoretical home stretch to the beginning of the end of the line. This is no longer a drill. This is no longer me thinking about what it will be like at the end of Shea Stadium. This one’s for real, I already bought the dream. I can stop having little fits of emotion late at night and during the day and on the train listening to the wrong song on my iPod. I can quit wondering whether I am going to miss Shea as much as I say I will or if I’m just saying that because I think I should miss Shea that much.”

With a little help from Donald Fagen and Walter Becker, I wrote those words on September 26, 2008, two days before the final game. I was a wreck as the end encroached. So, on some level, were the Mets. They were in the midst of playing a final week of home games to determine if there would be any more to immediately follow. As someone said into a movie camera a couple of nights before, “We are hoping that this year will be different. Maybe one more day, one more night, you’ll be in Shea Stadium, and thinking, y’know, maybe this is the year we win a World Series.”

Actually, that was me, too, for ten seconds in The Last Play At Shea, which came out in 2010, two years after Shea did not give us one more day, one more night, let alone another World Series. During a drought-conscious period in the early 1980s, you’d see a sign by the picnic area that said, “Well Water Used,” assuring anybody interested that Shea was kept green via environmentally responsible methods. By the end, though, Shea’s well of magic ran dry a game short of extending its stay on the active roster. On September 27, Johan Santana worked wizardry. On September 28, everybody returned to mortal. A final pitch from Matt Lindstrom was lofted by Ryan Church into the glove of Cameron Maybin, and there went 45 seasons. One all too brief procession of Met immortals later, that was that. Shea was done.

Now what?

***

In the middle of June 2015, it occurred to me I had just reached the 40th anniversary of my sixth-grade graduation. It was probably the first rite of passage I went through conscious that I was experiencing it. All I had known for six scholastic seasons was elementary school. Junior high awaited on the other side of summer.

I remember my reaction after leaving the ceremonies with my family. “I am finally done with this!” I shouted on the way to the car, not really pausing to think, “Now what?” All I had known would no longer be accessible to me. When I arrived in seventh grade in September, roaming the same hallways with supersized eighth- and ninth-graders, it was a whole other world and not an easily inhabitable one. I was one of the big kids in sixth grade. I had tenure. I was somebody. Groping to get a grip on seventh grade in the fall of ’75, I had never felt quite so small.

Maybe that transition informed my reluctance to exult that I’m Finally Done with certain phases of my life. Maybe that’s why when All I Had Known Stadium was being taken away from me, I hesitated to embrace the unknown. Besides, it wasn’t my idea to take my educational business to Long Beach Junior High School; somebody said I had to go.

That’s how it felt with Citi Field.

Home is where the Mets are, I tried to tell myself, but Citi Field took forever to feel that familiar.

***

Seventh grade was harrowing for the first couple of months, but eventually I got used to junior high (though I was perfectly happy to skedaddle to high school when tenth grade rolled around). 2009 was an awful season, even if it wasn’t exactly Citi Field’s fault the Mets lost 92 games. But Citi Field wasn’t helping, either. It was built, I suppose, as a counterpoint to Shea. If Shea was symmetrical, Citi Field had kooky angles. If Shea could hold 56,000 people, Citi Field would limit its seating by a quarter as much. If Shea was referred to, lovingly and otherwise, as a dump, Citi Field would be presented as “world-class,” with exclusive club upon exclusive club wherein the favored could accumulate points in their Infrequent Rewards program.

It was like Shea and night.

In my bones, I hated that first year at Citi Field, a facility that wasn’t my idea, which only served to make Shea a paradise lost in retrospect. A paradise of puddles, perhaps, but in the heart, you don’t notice the standing pools of water.

I wasn’t the only one who felt that way, apparently. You could hear the longing in people’s voices and eventually you could see it on people’s chests. The creators of the I’M CALLING IT SHEA t-shirt were nice enough to send me a couple of their signature items in ’09, which I was happy to wear, even if it never occurred to me call Citi Field Shea. I appreciated the sentiment. Those items were a fairly common renegade sight in those pre-7 Line days. I don’t see them worn out and about much anymore, but I occasionally slip mine on, mostly because it’s blue, orange and fits. To this day, whether I’m modeling it at Citi Field or anywhere else, I’M CALLING IT SHEA elicits more comments than any other t-shirt I own. The reaction is universally approving, usually with an addendum:

“I miss that place.”

I don’t know how it worked in other places, if Vet diehards couldn’t cotton to Citizens Bank Park, if the Three Rivers loyalists found fault with PNC, if there was a prevailing sense that Turner Field could never truly replace Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. I do know that Shea kept getting better in the popular imagination the more it wasn’t there. I do know that Facebook groups sprang up to celebrate its every waking moment from 1964 to 2008. I do know that Shea became synonymous with Mets in a good way during the post-2008 years that Mets became synonymous with all kinds of unflattering adjectives.

Citi Field had no shot of winning if the Mets had no shot of winning. Shea couldn’t lose if there was no game today.

***

There’s a worm-turned moment coming in all of this; you just know there is. And you probably suspect it has something to do with the Mets being very, very good in 2015. It’s the logical conclusion. The Mets stopped being bad, and the author steps back and says, say, this joint ain’t so bad after all. Cue roar of the crowd, then a time jump to April 2016 where an eighth postseason banner (contents TBD) is affixed to the left field facing of the Excelsior level. Lesson learned: home is indeed where the Mets are.

OK, you can use that if you need to get going, but it wasn’t quite as simple as Wilmer Flores sockin’ that ball and making everything all right when it landed over the wall. Besides, this isn’t about Citi Field. This is still about Shea, Shea for the last time.

But we do have to go through Citi Field to get to Shea, and we have to do so when Citi Field is at arguably its worst. When it’s not world-class. When no gourmet burger can fix what’s wrong. It’s far more vexing a problem than any Upper Deck puddle ever was.

On the first night of July in 2015, I encounter standing pools of apathy. It’s the Mets and the Cubs and a stunning lack of offense. Nobody scores for ten innings. Ruben Tejada reaches third in the eighth but gets himself thrown out on a screwy squeeze gone awry. In the eleventh, the Cubs begin to successfully peck away. A walk, an out, three singles…a run.

Then chants.

“Let’s Go Cubs!”

“Let’s Go Cubs!”

“Let’s Go Cubs!”

And there is only faint retaliation. Little booing, little Let’s Go Mets-ing. This wasn’t one of those ballpark takeovers, mind you. The Cubs fans were not all over the place as the Giants fans have come to be on San Francisco’s annual trip in. There were enough— a.k.a. too many — of them, but not an infestation. It wasn’t the Victor Diaz game from 2004 when you understood the parameters — Cubs in a race, Mets nowhere near one — and could deal with the disproportionate cheers from the visiting fans (and truly relish Victor Diaz and Craig Brazell making it their game by the end). This was a light crowd to begin with, made lighter by the late hour, and now it was, as measured by volume, more a Cubs crowd than a Mets crowd.