The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 17 August 2024 8:36 am Given the ebbs and flows of a entertaining yet maddening season, perhaps we’ve lost track of a simpler formula to make sense of the 2024 Mets: They need to outhit their mistakes.

The rotation is pedestrian, a bunch of No. 4 starters with ceilings as No. 3s. The relief corps is spaghetti at a wall. The defense, while much improved from the early days of the campaign, is just adequate.

That puts it all on a lineup that’s potent but streaky. Francisco Lindor started out the season encased in a block of ice (which makes it hard to swing a bat), but has been an MVP candidate once thawed. Brandon Nimmo‘s season has been a long march of dismay. Pete Alonso has been productive overall but clearly regressed as a hitter. J.D. Martinez has been a great clubhouse mentor but hot and cold in the lineup. Jeff McNeil has combined an inert first half with a so-far sizzling second half. Francisco Alvarez‘s sophomore season has been largely frustrating. When those hitters and their colleagues are clicking in sequence, the Mets can blow teams out of the water; when they’re out of sync they flail and fume while hoping an iffy pitching staff survives another day.

The lineup clicked in sequence Friday night, erupting for six runs in a thoroughly satisfying fourth inning against the Marlins and Roddery Munoz, who’d muzzled the Mets effectively in two previous appearances this year while getting cuffed around by pretty much everybody else in baseball.

McNeil fought his way through a long, tough AB before getting a slider that didn’t slide and whacking it into the seats for a 3-2 Mets lead. Harrison Bader didn’t need his pink Crayola bat in drawing a walk. Lindor bounced a ball over Jake Burger‘s glove that chased Bader home and saw Lindor wind up on third.

Exit Munoz, enter George Soriano, who hit Mark Vientos to bring up Nimmo, whose trademark cheerfulness has been much reduced by a long slump and a recent bout of illness. Soriano’s inaugural offering was another slider that didn’t do what its name suggests; Nimmo crushed it into the Soda Salon and the Mets were up 7-2, a lead they wouldn’t relinquish thanks to seven strong innings from Sean Manaea and a tidy two from Jose Butto.

Your recapper was driving up to Connecticut and listening through MLB Audio, so I have nothing to offer about Players Weekend flourishes beyond Bader’s bat, which was lovingly described by Keith Raad, or about Daniel Murphy joining the SNY booth.

I’ve loved baseball on the radio for decades and rarely if ever see it as a step down from getting to watch on TV, but an MLB deal with Audacy has seriously damaged the digital version of the radio experience. (Additional demerits for Audacy’s deeply stupid name.) I’m not talking about dropouts and pauses, which are largely a product of cell reception and not on Rob Manfred and Co. But MLB Audio is maddening even without that, it’s Audacy’s fault, and that is most definitely on MLB.

The cuts to commercial breaks are mistimed 90% of the time, with the announcers vanishing while reminding you of the game situation. That’s bad; what’s worse is that the ad inventory is pitiful. The same four to five ads run in crushingly heavy rotation, rapidly turning a showcase for a product and/or service into an ordeal that would be highly effective in a CIA black site.

Every year there’s an ad — or three, or four, or nine — that wears out its welcome within a week and comes to elicit pleas for mercy. This year’s offender features Tiki Barber hawking underwear designed to be comfortable for men. That’s how an adult who doesn’t need a drool cup would describe this product; the actual ad is a barrage of not very clever references to balls and boys. I’m sure this would make a 12-year-old boy howl with laughter until he knew every syllable and became bored (a point he’d reach very, very quickly), but my reaction is that I will never, ever, ever use this product. If I were rescued naked from a house fire and someone gave me a pair of Tiki Barber’s supportive briefs, I would hand them back and insist that I’ll do fine with a hastily constructed breechclout of half-burned newspaper.

I’d also like to punch Tiki Barber in the face. That would end badly but be worth it.

Enough about Tiki and his boys and back to the Mets trying to outhit their mistakes. That formula is usually discussed derisively, with the not terribly hidden implication that a front office only did half its job.

Now that it describes the Mets, I’m inclined to be a little more charitable. This was always supposed to be a transitional year, with the Mets pivoting from mercenaries (some of them in uniform elsewhere but still on the payroll) to homegrown talent; a key question coming into the season was whether the Mets took half-measures, hoping to be competitive when they should have opted for a full teardown.

As it’s turned out (at least so far), their own performance, National League parity and the allowances of the wild card era has left them fighting for the bottom wild-card rung. It’s not the same as arriving a little early — last summer’s ballyhooed import prospects have mostly struggled or been hurt — but the outcome is pretty similar, and has left me thinking of this season as a free spin of the roulette wheel.

The pitching staff isn’t going to get magically transformed; if anything, innings woes are going to put it in further danger. So the Mets better continue to outhit the inevitable mistakes.

by Greg Prince on 16 August 2024 9:08 am If Shea Langeliers touches home plate with two out in the top of the fourth Thursday, two batters after JJ Bleday’s grand slam, the A’s completely make up the 5-0 deficit that stared at them when the inning started and they are on their way to an exhilarating victory. But Langeliers misses the plate, and after Carlos Mendoza realizes Scott Barry has misread the situation, the call is challenged and overturned, getting Jose Quintana out of the inning. Now it is the Mets with the momentum. They hang on to a 5-4 lead, Luis Torrens stands out as the headiest of catchers for tagging Langeliers despite Barry making with the safe sign, and once Mark Vientos launches his second homer of the day, it’s clear the Mets are the ones heading for exhilaration and victory. It was close there for a minute, but we’re up, 6-4, we’ve got the momentum, and everything’s obviously gonna work out for the contending Mets as they brush aside the also-ran A’s.

Sometimes the mood swings in a completely different direction than you anticipate. Except everything you think you know about how a baseball game is going to play out based on swings in mood doesn’t show up in the box score if the competing teams don’t cooperate. The A’s didn’t cooperate, scoring a run in the fifth and then two in the sixth. The Mets didn’t do their part at all after Vientos’s second blast. No more runs for New York, and no help whatsoever from a pitching staff that left its control in its lockers. Quintana and five relievers combined to walk eleven. You walk eleven batters — A’s batters or any batters anywhere in the alphabet — you’re setting the table for a dish of well-earned defeat. Requiring three hours and forty-five minutes in this age of pitch clocks and other move-it-along innovations to certify the loss as official was simply the sadistic chef’s kiss to this matinee disaster.

So Shea Langeliers (nice name, nice backstory) was out at the plate when he first appeared safe. The A’s won, anyway. Buddy Harrelson was called out at the plate against the A’s in Game Two of the 1973 World Series despite video evidence to the contrary in the pre-replay rule era, and despite Willie Mays having a better angle on Ray Fosse missing the tag than Augie Donatelli. The Mets won that game, anyway, but it still irks.

We didn’t need fresh irk in 2024, but we have it in the form of A’s 7 Mets 6 in the finale to a series that carried echoes of another three-game set at Citi Field versus a California club we were pretty sure we were gonna take two from but didn’t. I speak of the 2022 Mets-Padres Wild Card Series, whose pattern was two-thirds replicated this week. Padres won easily the first night, the Mets won easily the second night. The comparison loses its resonance when one remembers we were bleeping one-hit by Joe Musgrove, Joe Musgrove’s ears, and whoever else came on after Joe Musgrove, but the same bottom line unfurled. We lost two out of three. That series ended our postseason.

This series and its ramifications? The well-honed fan instinct says we’re not going anywhere after playing as we did Thursday and have lately, losing nine of our last fourteen and looking like so many distinct forms of dreck when we lose. Dreck that doesn’t hit in the clutch. Dreck that doesn’t hit at all. Dreck that plays down to the opposition. Dreck that walks the ballpark. Dreck that blows a five-run lead.

Yet Thursday was just one game and the Mets are just two games out of a playoff spot. They keep making playoff spots, thus we are compelled to continue acting as if our proximity to one indicates we could be a playoff team. In the ultimately playoff-bound year of 2016, the Mets played more than a few games like this as summer crested, and my towel was summarily thrown. Soon I was reaching into the linen closet for another towel to clutch, because bad games and rough patches can be overcome across a season’s last quarter no matter that you’re absolutely sure there’s no way your team is capable of getting its act together. The Mets are doing themselves no favors at the moment. They can start being good to themselves by, you know, playing better on a consistent basis. Maybe all they need is one break to go their way…like a run for the opposition disappearing from the scoreboard because a slide is off, a catcher is aware, and the system works.

OK, bad example.

by Jason Fry on 15 August 2024 8:04 am Things are getting chippy between the Mets and A’s — and you know what, that’s fine. Baseball should be a little chippy.

Tuesday saw Austin Adams, whom most of us forgot was ever a spring training Met, all but levitate after coming in and saving Joe Boyle‘s bacon, a display that culminated with Adams doing the Mets’ OMG pantomime. (Which I assume he never witnessed in Port St. Lucie, but who am I to police the pettiness of others?)

So on Wednesday, after Francisco Lindor homered off Joey Estes in the third inning to give the Mets a 2-0 lead, it was of course time for the obligatory OMG, which Lindor just happened to direct not at his own dugout nor at the stands but in the direction of the A’s pen. Unless Lindor’s message was for Adams’s relief colleague T.J. McFarland, whom I had no memory of as a 2023 Met and so required a trip to The Holy Books for verification. Yep, McFarland’s in there (as a Syracuse Met); no, I still don’t remember him.

I do remember Mike Cameron, who was at Citi Field to cheer on his son Daz, now employed by the A’s. Next to Cameron during a Steve Gelbs interview was Phil Nevin, whom I also remember, and whose son Tyler is also employed by the A’s. That got me wondering about Estes, who I figured had to be the son of Shawn Estes. Poor Shawn Estes — he homered off Roger Clemens, not something starting pitchers generally do, and yet is remembered primarily for failing to hit the Rocket with a pitch in that same game.

For the record, no, Joey Estes is not the son of Shawn Estes. And while he’s a little chippy himself, his location was off: In the second, Mark Vientos ripped a scorcher down the third-base line that Darell Hernaiz couldn’t corral, bringing in Jesse Winker for the Mets’ first run. Estes flung his hands up to his head, following that with an arms-out, WTF gesture; between innings, he walked right by Hernaiz. Ron Darling didn’t miss that and didn’t like it; after the game, Estes had a not very convincing alternative explanation for what had happened.

(Darling also noted it as a teachable moment for A’s manager Mark Kotsay, which I’m sure it was; we should always remember that baseball clubhouses are kabuki theaters, with Estes’ postgame comments the public display and something else quite possibly happening away from the cameras.)

Our last moment of chippiness came from David Peterson, who was not happy to see Carlos Mendoza coming out of the dugout to get him with two outs in the seventh and the Mets up 3-1. Peterson was superb (as he’s somewhat quietly been since making his belated season debut at the end of May) and wanted to keep going north of 90 pitches, which is something you’d like your starters to be a little chippy about. As it turned out, Huascar Brazoban cleaned up nicely and a six-run seventh drained the suspense from the game, with Danny Young and Adam Ottavino cleaning up.

Those last two Met runs came in on a double from scabby-nosed Pete Alonso, the last of his four hits on the night. Alonso had looked better in the first game of the series, not expanding the strike zone the way he’d been doing during a long slump, and I had the feeling something might be turning while refusing, as a lifetime Met fan with the scars to prove it, to say so with much confidence. An Alonso tear could mark yet another acceleration in this strangely stop-start Mets season and lead to more chippiness from opponents.

Which none of us would mind at all.

by Greg Prince on 14 August 2024 10:39 am Maybe the Mets were trying to tell us something by not letting us inside the ballpark until 90 minutes before first pitch. What they were telling us was at some point they changed the entrance time for a weeknight non-promotion game. For as long as I can remember, the gates opened at 5:10 for a 7:10 start. Stephanie and I showed up Tuesday around 5:15 only to find lines of people and nothing happening, as if we were all tourists queuing for a Broadway show. Geez, I thought, I hope there isn’t some kind of incident they’re keeping us out to address. Or, more likely, it’s the Mets being the Mets. The latter, definitely the latter.

I guess I haven’t arrived outside Citi Field in these circumstances — with a ticket kind of early — in a while. I’d have figured they wanted people inside so we could start spending and racking up those Mets Connect points, but maybe 5:40 keeps them from having to pay those who operate the concessions a half-hour’s worth more. Well, sooner or later they let us in.

And weren’t we sorry?

We weren’t, actually. Tuesday was Chasin Night at Citi Field, even if it had to wait an additional 25 minutes to get going. Chasin Night for Stephanie and me is Prince Night for our father-and-son friends Rob and Ryder, the Chasins. Really, it’s Our Night, the August date the four of us have kept for now fifteen consecutive summers, even the pandemic one when we watched a game together over Zoom. Our Night is not result-dependent. If it was, it would have gone the way of the 5:10 gates-opening.

An on-point gift from the Chasins to mark the 15th consecutive Our Night. (FYI to Augie Donatelli: Buddy was safe.) Citi Field management was against us coming in too soon. The Oakland A’s were against us once we were seated. As will happen with any opponent you don’t see too often and have vaguely warm feelings for, if the Mets lose badly to them, you despise them by the final out. The denouement of 1973 notwithstanding, I don’t know if I’d apply hatred to the A’s, who are in Queens for the first time in seven years and, once they leave, will never return as Oakland. Minor-league accommodations in Sacramento await this once-proud franchise for a spell and then, if shovels ever hit the ground, they’ll be the Las Vegas A’s, assuming they don’t change the most easily spelled, most mysteriously punctuated team name we’ve ever known. A kid fully decked out in A’s gear asked me on the platform in Sunnyside if the 7 Express went to Willets Point. I assured him it did. When our train pulled in, I watched him tear down the stairs like he was Shooty Babitt going for an extra base. He, like we, didn’t know he’d have to wait to get inside the ballpark. But I admired his enthusiasm for his A’s, no matter that A’s ownership merits none of it.

Simpatico for their fans didn’t extend to the occupants of their dugout. The A’s player who drew most of our attention was a relief pitcher who I kind of thought sounded familiar. Yeah, Austin Adams. Didn’t we have him in the offseason? We did. We sent him on his way in Spring Training, and he wound up on Oakland, and he’s still there, and good for him. Adams wasn’t here long enough to be an Old Friend™ or even a valued acquaintance. Austin Adams was that that guy I think we once shook hands with in Port St. Lucie. It appears he remembers us.

The Mets had a few truncated rallies in the course of their 9-4 loss. The one that seemed most promising had three runs in and two runners on, which didn’t wind up as robust as it ought have. The Mets had been down, 7-1, when that inning, the bottom of the fifth, began. Still, Ryder and I agreed, this game had felt “comebackable,” and there we were, coming back. Coming on for Oakland, trotting in from the bullpen at not quite the same speed as the stirrups guy from the subway was Adams. Citi’s A/V squad lowered the lights, pumped up the music, and set the stage for any fan who chose to wave a cell phone light, presumably in the name of home-team hype, though it came off as mindless taunting of some innocent middle reliever. The spectacle reminded me of when I was six years old at the circus and we were all thrilled to have those miniature flashlights our parents bought us. Maybe Adams felt clowned. He took the mound, retired his three hitters in order, and snuffed out the last productive Met inning of the evening.

Next thing we heard was booing. That’s pretty rough, I said to Ryder, booing the Mets after an inning when we closed to within 7-4. From our vantage point in the last row of 309, I hadn’t discerned the booing was directed at Adams, who decided to be this year’s Paul Sewald. Sewald, the Quadruple-A schleprock turned dynamite closer, did a thing with his hand to his ear a couple of years ago when he came into Citi with the Mariners and set down the Mets who (with reason) never fully committed to his potential. BOO! on Sewald in 2022. Adams, replay helpfully revealed, was doing his own private OMG bit in front of 30,000 not so friendly foes (plus the stirrups fellow, who presumably loved it). BOO! on this A’ss in 2024.

Later, the dude swore he meant no disrespect and he was just fired up. At least somebody was enjoying the way the game was going.

Call Adams the pitcher of the game. It surely wasn’t our trade-deadline savior Paul Blackburn, who gave up seven runs over four innings, and it wasn’t Joe Boyle, who came in with a 7.16 ERA; was staked to a six-run lead by the third; and didn’t last long enough to qualify for the win. Boyle’s ERA rose even as the Mets fell. We were also treated to an Edwin Diaz sighting — and more scoreboard histrionics that seemed out of place as no Met lead was being protected.

Pete Alonso, who delivered two ribbies, was hopefully OK after he face-planted in quest of smothering a ball ticketed for the right field corner and came up with a noticeably skinned nose that dripped blood (thanks, monitors, for the closeups). Behind the last row of 309 there was an area that beckoned loiterers, including three kids who couldn’t have been older than eight. They shrieked for a half-inning in Ryder’s and my ears while whichever dad brought them chatted with somebody a few feet away. They were quite taken with the video images of Alonso’s nose. So was the dad, who interrupted his conversation to let them know how “tough” Alonso was to wave off the trainer and stay in the game with blood in the middle of his face. Ryder and I concluded he was teaching these children a questionable lesson. “Kids, never go to the school nurse.”

The Met we focused on most once Alonso’s toughness went unquestioned was Jesse Winker. Winker, we concurred, was going to be the mid-season Met get who in three years we wouldn’t instinctively remember was ever a Met, a Matt Lawton for a more digital age. But then Winker got a single and drove in a run with a double (necessitating the warming of Adams in the A’s pen), and Ryder and I converted to Winkerism. Jesse Winker is halfway to the cycle. Jesse Winker should be known as the Wild Card, because if the Mets had 26 Jesse Winkers, they’d have the Wild Card in hand rather than be slipping away from it. All Mets currently on rehab must get pestered by fans in the hinterlands asking if they really know THE Jesse Winker.

Winker never did get that cycle, and the Mets never did get the Road Trip From Hell out of their system. But Stephanie and I did get in on some of that $5 Tuesday action. Earlier this year, just as the Mets were OMG’ing their way into our hearts yet perhaps hedging their bets on whether they’d need to attract a crowd with something other than exciting baseball, the club announced select food and beverage items would cost “only” five dollars on Tuesday nights. Five-dollar hot dogs. Five-dollar pretzels. Five-dollar bottles of water. In Pulp Fiction, five dollars for a milkshake was considered extravagant. Now it’s a bargain. We were so stoked to take advantage that we showed up at 5:15. The Mets told us to hold our horses and they’d hold our hot dogs. Per John Travolta as Vincent Vega, I don’t know if it was worth five dollars, but it was pretty fucking good.

The Princes and Chasins parted ways at the edge of the Rotunda. We Princes, as ever by this juncture in the journey, were laser-focused on our reverse commute. Stephanie had already stepped six inches outside the border separating Out There from In Here when Rob and Ryder told us they wanted to duck inside the team store before they went home. Stephanie stepped back in for a proper goodbye until next August, eliciting a glare from one of the maroon-shirted customer-interaction specialists stationed by the main exit to make sure you don’t try to sneak back in and sleep overnight behind a sausage cart in advance of tomorrow’s game (one way to solve the 5:10/5:40 gap). What’s that Jackie Robinson quote inscribed on the wall? “Glaring at your customers is not important except on the impact it has on other customers.” We got our hugs and handshakes taken care of without a supervisor having to get involved, thereby completing the Citi Field circle of life. Don’t come in too soon. Don’t come back in. And we hope to see you again.

by Greg Prince on 12 August 2024 3:46 pm Adequacy thy names are Quintana, Manaea, Severino, Blackburn, and Peterson. We’ve had some really good games from the starting pitchers who compose our rotation this season. Some not so good games, too. Some days you wish we had the Christian Scott who looked so promising in his debut or the Kodai Senga who was on point for five-plus innings before an injury subtracted him from our plans.

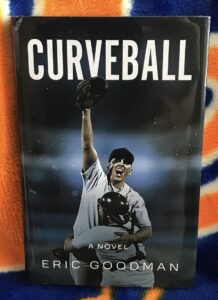

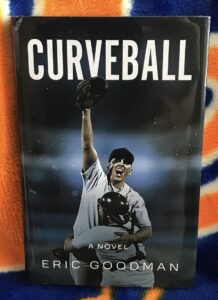

For about a week, the starting pitcher I wanted to see on our mound more than any other was Jess Singer, coinciding with the week or so I was wrapped up in reading Curveball, the new Metcentric novel by Eric Goodman. I imagine it’s a book more about the human condition than baseball, the way I’m always being told that baseball movies aren’t baseball movies so much as they’re this genre or that. But we’re Mets fans. Make two of the three main characters Mets and build the story around a Mets season, it’s a book about the Metsian condition.

I’m gonna guess Goodman wouldn’t mind that assessment, for he, too, is a Mets fan. Takes one to write one like this. The author, in a note introducing his work, let me know he’s been rooting for this team since 1962. He also first wrote about a Singer pitching for the Mets in 1991’s In Days of Awe. The pitcher at that juncture in Mets history was the great Joe Singer. We could have used a great pitcher right around then. Goodman decided some three decades hence that we needed a sequel. Thus, Jess, son of Joe. Two Singers. Two pitchers. Two Mets. Loads of talent…including Eric Goodman in bringing this pair to us. I’m gonna guess Goodman wouldn’t mind that assessment, for he, too, is a Mets fan. Takes one to write one like this. The author, in a note introducing his work, let me know he’s been rooting for this team since 1962. He also first wrote about a Singer pitching for the Mets in 1991’s In Days of Awe. The pitcher at that juncture in Mets history was the great Joe Singer. We could have used a great pitcher right around then. Goodman decided some three decades hence that we needed a sequel. Thus, Jess, son of Joe. Two Singers. Two pitchers. Two Mets. Loads of talent…including Eric Goodman in bringing this pair to us.

A couple of grabbers to get your attention.

1) Joe Singer was known in his heyday as Jewish Joe Singer. The nickname for Jess is Two-J’s, because Jack Singer — the irrepressible zayde or grandfather in this mishpacha and our third main character — proudly declared the boy was as “big as two fucking Jews”. The aura of Sandy Koufax exists in the world of Curveball, and the Singers are the closest thing we’ve seen to the, uh, sainted Jewish lefty since the Dodger southpaw took off Yom Kippur. As an homage, Joe and Jess were and are No. 32 on your overpriced scorecard.

2) The existence of Koufax (not to mention Ken Holtzman) within Baseball-Reference means a star Jewish pitcher, while unusual, isn’t unprecedented. But an openly gay pitcher in the major leagues is a different story. As of the present reality, we haven’t had any MLB players go to work making no secret of their non-heterosexual orientation. When Curveball begins, that’s the situation as well. The percolating question as one gets into the book is, will this be the situation by the last page? Let’s just say Jess Singer is harboring a secret and much of the tension revolves around his deciding if he’ll make it common knowledge.

Other issues, including literal life and death, permeate Curveball, and they deserve the reader’s consideration, but let’s not stray from the Metsiness of all this. The Mets of Jess Singer are a recognizable contemporary replica of what we’ve rooted for these past few years. There’s an owner you might mistake for Steve Cohen; a club president who seems to resemble Sandy Alderson; and players referred to as Pete, Squirrel, Nimms and the superstar shortstop. Goodman didn’t exactly drop Jess Singer onto the early-2020s Mets, but he knows his way around Citi Field physically and spiritually.

Each of the three Singer men presents his own emotional handful to those who care for them, which as the novel went on, included me. I raised my arms at least twice in triumph as I devoured their tale, and only once directly relating to the baseball action Goodman created. In the parlance of sports talk radio, I’m not a fiction guy, but my affection for this book was very real. In case you can’t make me out over PitchCom, I’ll put the signal in plain sight where any Astro can interpret it: don’t leave Goodman’s Curveball off the plate.

by Jason Fry on 11 August 2024 10:50 pm I generally keep track of what the Mets are doing even if I’m away, sneaking looks at MLB.tv, popping an airpod into an ear, or at least letting GameDay do its pantomime thing in my lap.

But combining a trip to Iceland with the Mets’ Road Trip from Hell was a perfect recipe for being well and truly out of pocket. With the additional time change, the games started after I was asleep and concluded before I was awake. I heard Paul Blackburn‘s debut against the Angels, with the last out recorded shortly before boarding a midnight flight (oh, things looked so promising then). And I caught the first couple of innings of the middle game against the Mariners because I couldn’t sleep.

Between them, nada: I’d look at my phone over skyr and coffee in the Icelandic morning and try to make sense of things that had already transpired. There’s always a funny moment when you look at the score of a baseball game and your brain needs half a second to parse it: Oh, the bigger number’s here and the smaller number’s there, that’s good/bad, and now that I’ve got it straight, let’s figure out exactly how that happened.

What this sequence of revelations told me was, above all else, frustrating: We can’t win a series against the Angels, really? Figured they’d drop that dumb makeup game in St. Louis, so whew. OK, nice bounceback series in Colorado. And then the buzzsaw of the Mariners’ starting staff and the bats returning to slumber.

I got to watch the Mets uninterrupted for the first time in nine days on Sunday evening, and for a while that even seemed like a good idea. Luis Castillo was dealing, but so was Luis Severino, with the shadows of a Seattle afternoon game turning an already tough job for hitters on both teams into the stuff of borderline farce. But then a taut, tight duel turned when the Mets let in a run on a little infield hit that Francisco Lindor‘s best effort couldn’t quite convert into an inning-ending out, Severino left a changeup in Cal Raleigh‘s wheelhouse, and suddenly the Mets were down 4-0.

Down 4-0, and it was about to get a whole lot worse. Jeff McNeil homered to keep the Mets from being shut out all three times in Seattle, but that was all that went right. In the sixth the annoying ESPN crew ooh’ed and ahh’ed over a bald eagle soaring above Seattle; a moment later I was fervently wishing this majestic bird would swoop down and carry Ryne Stanek off to Syracuse or the Ross Ice Shelf or some other place where I’d never have to see him again. Soon after that I was imagining other eagles dropping by to remove Adam Ottavino and Danny Young from view. Alas, those relievers stayed around to do unhelpful things until the Mets were mercifully allowed to slink back to New York, grateful the whole thing is finally behind them.

Except it isn’t. The Mets apparently pissed someone off in the MLB scheduling department, as they’ll be heading back to the West Coast in 11 days.

Maybe I’ll go back to Iceland and miss that one too.

by Greg Prince on 11 August 2024 2:22 pm The last shreds of Interleague mystery are falling away this season. We’re in Seattle for the first time since 2017, which hints at the randomness of the way NL vs AL used to be scheduled. When this gimmick was introduced in 1997, We in the NL East played They in the AL East every year for five years. Then the AL Central and AL West got involved in our lives on an alternating-season basis, though not always each team, and it didn’t necessarily elbow aside oddball intrusions. In 2007, for example, our Interleague slate encompassed the A’s, the Tigers, the Twins and the Yankees. In 2010, it was Baltimore, Cleveland, Detroit and the crosstown rivals. A year later, we were still getting paired with the Tigers, but also the A’s and Rangers (and Yankees, always the Yankees). I couldn’t detect patterns then and I can’t discern one now.

When the Astros departed the NL in 2013, it was supposed to become more predictable. We’d play one division every three years, and we’d switch off the sites accordingly…and the business with the team in the same city would remain annual. Yet circumstances still managed to ruffle the smoothness. We went fifteen years between hosting the team formerly known as the Indians. It took seventeen seasons to get the White Sox to Flushing. COVID certainly didn’t help. We’ve played three games in Buffalo (2020) since we were last in Toronto (2018), but we’ll be in Toronto in September. The last time we were on the South Side of Chicago (2019), the big story was we didn’t trade Noah Syndergaard and the jaw-droppingest home run (426 feet, 109.2 MPH) was launched by Michael Conforto. But we’ll be at whatever New Comiskey insists on calling itself in late August.

Conforto’s homecoming to Washington state was a prime storyline the last time the Mets visited Seattle, just over seven years ago, which might as well be seventy. The streak of the moment was Jacob deGrom — who was Jacob deGrom, to be sure, yet was still a season away from becoming Jacob deGrom — sitting on eight wins in eight starts. His streak got snapped in Seattle, and it would rarely again seem like deGrom’s excellent pitching was capable of producing a personal W. This was also the last weekend before the Mets did what most everybody was waiting on them to do and called up Amed Rosario. Remember when he was the personification of the future? That Mariners series was our first look at Edwin Diaz, who we might have heard was having an excellent season three time zones and another league away. We had just traded Lucas Duda for a minor league reliever named Drew Smith. We were about to trade a whole bunch of familiar names for the less familiar kind (none of whom attained a Met track record on the level of Smith’s, which, to be honest, isn’t all that voluminous). On the personal front, I had just said goodbye to one my beloved cats — RIP Hozzie, 2002-2017 — which might explain why the Mets’ trek to Seattle stays with me a little more than most fleeting Interleague entanglements.

Prior to the latest shutout at the hands of the Mariners, I concluded there is no organic reason I should particularly care about the Mets playing them ever in the regular season. There could have been. In October of 2000, the Mariners were in the ALCS when we were in the NLCS. A Mets-Mariners World Series would resonate to this day any time the two franchises crossed paths. The Mets will play the A’s and Orioles on the upcoming homestand. Echoes of 1973 and 1969, respectively, will drown out remembering that time we played them in 2010 or whenever.

In my unfrozen caveman heart, the World Series is the only proper setting for a National League team to play an American League team in a game with stakes. That’s organic. All other such meetings should be confined to Spring Training and exhibitions that fall out of the sky. The deluge of Interleague play ensures every World Series matchup of the past gets a rematch every year. There’s little charming about that when you can count on its arrival like National Potato Chip Day, but at least it’s something. Before it all got codified, those encores got your attention. Mets-Orioles. Mets-A’s. Mets-Red Sox. (Mets-Red Sox also qualified as an exhibition that fell out of the sky when they scheduled a charity home-and-home in September 1986 and May 1987 without any idea that they’d be getting together for stakes during the October in between.)

Mets-Yankees was better when it was the Mayor’s Trophy Game. Mets-Royals post-2015 lost its juice by 2019. Mets-Royals could have just as easily been Mets-Blue Jays (a World Series we would have won, I take it on faith). Mets-Orioles and Mets-Red Sox could have been Mets-Twins and Mets-Angels had the playoffs in the other league had different outcomes those years, but the two World Series in question worked out, so why mess with a good thing? We’d look at Mets-Tigers regular-season encounters differently had we done our part in the 2006 NLCS.

Had the 2000 Mariners of John Olerud, Rickey Henderson, Alex Rodriguez and whoever else was there before Ichiro Suzuki done their job in the ALCS and prevented a Subway Series, this weekend would be embellished by video clips of that unforgettable October twenty-four years ago when the long transcontinental flights were worth it, because the journey we were on allowed us to set the stage for (if we’d won in four or five) or bring home (if it had gone six or seven) our third world championship trophy. Or maybe it would have gone the other way, and we’d still sneer at the sight of anything smacking of Seattle.

Instead, it’s just another date with another opponent on another overstuffed schedule. Next time we play “at Mariners,” it will be in two years. Same deal with the White Sox and Blue Jays and every AL club we didn’t host this year. We’ll host them next year, just like we hosted them last year. Those we visited last year we’ll visit next year. And the nicest part of all, Val, I look just like you.

by Greg Prince on 10 August 2024 1:03 pm A pretty good baseball team soundly defeated another pretty good baseball team on Friday night in a corner of the country far from the one where I struggled to stay awake to witness the entirety of the contest. By drifting off as I tend to when baseball games begin inconveniently late where I am, I missed a couple of runs scoring, which was OK, since none of the runs scored in any inning were scored by the pretty good team I was rooting for. My team’s still pretty good even if it didn’t win. These things happen, just like my in-game naps. Maybe it will work out better tonight. I’ll probably fall asleep for at least part of it.

My team needs to play games earlier, and, if possible, only the games it wins.

by Greg Prince on 9 August 2024 8:59 am Oh, look — the three National League Wild Card teams at the moment are the San Diego Padres, the Arizona Diamondbacks and the New York Mets, while the three National League division leaders remain the Philadelphia Phillies, the Los Angeles Dodgers and the Milwaukee Brewers.

Who is missing from this “if the playoffs began today…” picture? Correct! It’s the Atlanta Braves!

The playoffs don’t begin today, and playoff positioning is more fluid than sweet tea on a scorcher of a Saturday amid the red clay of Georgia, but let’s enjoy Atlanta’s exclusion from postseason tournament calculations, if only for twenty-four hours.

“If the playoffs began right now, the Braves wouldn’t be in them,” I informed my wife after the Mets finished off the Rockies, 9-1, shortly before the six o’clock news Thursday evening.

“What a shame,” she deadpanned.

Stephanie is not exactly caught up in the daily fluctuations of the standings, but she can sort out the villains in our narrative without having to ask which one merits our contempt most. Eleven Octobers ago, first thing in the morning, I updated her on the postseason in progress, letting her know that the night before the Dodgers had eliminated the Braves. I expected no more than “that’s nice.”

Instead, she delivered, “See ya, Braves!”

Yes, yes, a thousand times yes. And that (2013) was a postseason we as Mets fans were merely watching, not one our team was trying to slug its way into. We didn’t have Pete Alonso going extremely deep twice as we did in our Coors Field finale. We didn’t have Mark Vientos chipping in a homer. We didn’t empty a gunny sack loaded with doubles as we did on the Rockies in the very first inning. We didn’t have Tyrone Taylor flying to and fro to track down balls before they could become mile-high trouble. We didn’t have David Peterson enjoying a gratifying Colorado homecoming. Thursday we did, and now we have floated ahead of our more-or-less archrivals for something of substance, keeping them away from what they want in the process. We have a half-game lead on the Braves for the third Wild Card spot with 47 games to go, which isn’t a prize they embroider t-shirts over, but with 47 games to go, the best place to see the Braves is behind us.

Chances are we’ll see the Braves in our nightmares as the National League derby continues. It’s too much to ask they plummet through the contending tier that lately encompasses the Cardinals, the Pirates and the Giants and find themselves sliding down toward, well, the Rockies. In fact, the Braves get to play the Rockies this weekend, while we travel — we always travel — to Seattle to take on a bona fide contender in the other league.

Can’t get too comfortable in the second week of August over positioning for October. But I’ll be damned if I’m not going to enjoy the current reality for however long it’s current.

by Greg Prince on 8 August 2024 12:22 pm Aw, I missed a triple? I did. I nodded off in the seventh, shortly after Jose Butto came on in relief of Paul Blackburn, the score at Coors Field knotted at two. That’ll happen with any game that starts any time after 7:10 where I sit; then stretch out; then close my eyes for just a little bit, I’m sure. Extended day, abbreviated night. But I did stir in the bottom of the ninth. Things had changed, per the SNY graphics. The Mets were up, 5-2. Wait, now it’s 5-3, but Gary Cohen didn’t seem concerned. The Mets, he said, would gladly trade a run for an out here. How many Rockies are on base, anyway? Why is Edwin Diaz giving up a run and why is this considered a fair exchange? While I was in the process of discerning there were two out, Edwin finished striking out Charlie Blackmon. “And the ballgame is over!”

I didn’t have the energy to stay awake for the postgame show, but I reached for my phone, clicked on the At Bat app, and satisfied my curiosity at how a game that had been tied for so long went the Mets’ way. Francisco Alvarez had tripled with one out in the top of the ninth — and I missed it. Triples are so great, yet so rare. Maybe that’s why they’re so great. And a catcher triple! Francisco has hit two this year, practically leading the team (Tyrone Taylor has three). Fralvarez, as I sometimes address him from the couch, isn’t our catcher of the present and future for his tripling. Luis Torrens is an ace backup, though he has yet to triple as a Met. Nobody really expects a triple to begin with. Other than Lance Johnson for one year and Jose Reyes for a bunch, “somebody needs to triple here” never passes through your mind. They weren’t catchers.

When I think of a catcher hitting a triple, I think of Gary Carter tripling in Game Four of the 1988 NLCS. Sixth inning. Kid’s three-bagger sends Kevin McReynolds home from second, putting the Mets further up on the Dodgers, 4-2. Nobody’s out. We’re gonna blow this game open, we’re gonna be one game from the World Series, we’re gonna have our hands full with Oakland, but I know it’s coming. Instead, Carter is left on third and another catcher for the other team hits a four-bagger. To me, our dynasty didn’t turn on Mike Scoscia’s home run. It withered when the Mets didn’t take advantage of a catcher triple. (And I stopped making World Series plans in advance of pennant-clinchings.)

Yet I still relish a catcher triple like few other hits by few other players. Jerry Grote tripled nineteen times as a Met, which ties him for nineteenth among all Mets in triples. I wouldn’t have guessed that. John Stearns is part of a six-way tie for forty-fifth place in triples with ten. I would have figured Stearns, who could run, had more than Grote. Turns out he has as many as, among others, speedy Roger Cedeño and Wednesday night’s RBI hero Francisco Lindor. It was Lindor who delivered the key single — a common but essential form of base hit — to put the Mets ahead in the same ninth that Alvarez did three times as much as single. Fralvarez was shown mercy and to the bench after tripling. You wear the tools of ignorance for eight innings and then chug 270 feet. Harrison Bader pinch-ran. Ben Gamel (still on the team, apparently) and Tyrone Taylor walked. Then Lindor came through to make it 4-2. One out later, Jesse Winker, who to this point in his Met tenure hadn’t been any more a factor in any day’s Met offense than Ben Gamel, singled for insurance. A three-run lead while I slept. A three-run lead trimmed to two as I briefly eschewed sleep. A two-run lead to put me pleasantly back under a moment or two later.

I would have liked to have seen that triple as it happened, but getting the gist did just fine.

|

|