The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 20 May 2011 4:17 am Welcome to The Happiest Recap, a solid gold slate of New York Mets games culled from every schedule the Mets have ever played en route to this, their fiftieth year in baseball. We’ve created a dream season consisting of the “best” 40th game in any Mets season, the “best” 41st game in any Mets season, the “best” 42nd game in any Mets season…and we keep going from there until we have a completed schedule worthy of Bob Murphy coming back with the Happy Recap after this word from our sponsor on the WFAN Mets Radio Network.

GAME 040: May 26, 1964 — Mets 19 CUBS 1

(Mets All-Time Game 040 Record: 28-23; Mets 1964 Record: 12-28)

For what very good teams could do in one year, the toddler Mets required two-and-a-quarter seasons, namely win their 103rd game (ever). But how much the Mets scored to win their 103rd was more than some teams managed in a week — like the 1964 Mets, for example.

In the seven days before they touched off an offensive outburst for the ages, the Mets played seven games, lost six of them and scored 12 times. Pretty typical stuff for the Mets in their formative years, which is what made the events of this particular Tuesday in Chicago so Amazin’ly atypical.

Come to think of it, maybe those weren’t really the Mets out there at Wrigley Field. Their lineup featured two guys named Smith: Dick, batting leadoff and playing first, and Charley, playing third and hitting sixth. Smith is one of those names a fellow uses when he’s pretending to be somebody he’s not. Dick and Charley masqueraded as superstars, going a combined 8-for-12 with seven RBIs between them. Then again, guys who tended to register at motels under every possible Met name — from Christopher and Cannizzaro to Hunt and Hickman to Thomas and McMillan — were registering base hits and runs batted in and just about everything positive a box score would allow.

Each member of the Mets’ starting lineup hit. Dick Smith alone tripled, doubled and singled thrice. Charley Smith contributed a three-run homer and five ribbies. Hickman drove in three, scored three and notched three singles. Overall, in 49 official at-bats, the Mets collected 23 hits, a total that remains unsurpassed as the most the Mets have ever accumulated in a nine-inning game.

The beneficiary of all this largesse was Jack Fisher, a 1-for-6 batter himself, but mostly a four-hit complete game pitcher. When all the dust the Mets kicked on the Cubs settled, he was the winner of a shocking 19-1 decision.

“This,” announced Bob Murphy, in a masterstroke of understatement as the final out approached, “is some kind of a day, I want to tell you.”

Clearly, the best line to come out of this unforeseen explosion was the one that stretched out across the Wrigley scoreboard:

NEW YORK 430020406

But there were a few other lines that, like the Mets’ club-record 18-run margin of victory, still stand the test of time.

Like Tracy Stallard’s, after the Mets tacked on a six-run ninth: “That’s when I knew we had ’em.”

Like Casey Stengel’s, after finally not being on the receiving end of a blowout: “I suppose most of the club owners will be trying to contact me now to get my players.”

And, most enduringly, like that uttered by the eternally quoted caller to the sports department of the Waterbury Republican, a Connecticut gentleman who sincerely wanted to know if what he thought he’d heard was true…that the cellar-dwelling Mets had actually scored 19 runs that afternoon. When he was told yes, they most definitely did, the fellow offered the follow-up question that, given the state of the Mets since there had been Mets, absolutely needed to be asked:

“But did they win?”

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On May 17, 2007, the Mets hit their snooze button repeatedly for eight innings, but then jumped out of bed and bolted out the door like Dagwood Bumstead scrambling to make the bus. Left in his wake, like that poor mailman Dagwood was always creaming in his last-minute rush, were the Chicago Cubs, who thought they were delivering a pretty simple 5-1 decision to their win column. Turned out Cubbie plans needed to be returned to sender. Once the Mets got going in the ninth inning of that heretofore sleepy Thursday matinee, they couldn’t be stopped. A “B” lineup, fortified by some unusually potent bench strength, methodically took apart Lou Piniella’s bullpen, with everyone from utilityman David Newhan to rookie Ruben Gotay to pinch-hitter David Wright singling. Throw in a couple of walks, and the stage was properly set for Carlos Delgado to poke a ball into right field, chasing Endy Chavez home from third and Gotay from second with the fourth and fifth runs of the bottom of the ninth, giving those suddenly alert Mets a rousing 6-5 comeback victory.

GAME 041: May 20, 1999 (2nd) — METS 10 Brewers 1

(Mets All-Time Game 041 Record: 22-29; Mets 1999 Record: 23-18)

Just when you thought you’ve seen everything at the ballpark, sometimes you see a little more. It helps when you are shown two ballgames, though after the spectacle they witnessed in the opener of a Thursday twinight doubleheader between the Mets and Milwaukee at Shea Stadium, 19,542 couldn’t have been looking for anything else all that grand. The first game, after all, gave them plenty.

Al Leiter and Jim Abbott faced off in the opposite of a pitchers’ duel, though each of them lasted to the fifth inning. Leiter wasted an early 4-0 lead and let his team fall behind when ex-Met Alex Ochoa doubled in a pair to give the Brewers a 6-5 edge. But Leiter was rescued when the recently recalled Benny Agbayani continued his scalding ways by blasting a three-run home off reliever Steve Falteisek. The Mets kept building on that lead, ultimately getting it up to 11-6 in the seventh on Agbayani’s second homer of the game.

Good thing Benny was bringing the Hawaiian punch, because Allen Watson gave up a three-run homer to Jeff Cirillo in the top of the eighth. John Franco came on to quell any more comebacks, but the closer — who in April locked down his 400th career save — couldn’t possibly make this one easy. Franco put two runners on, and disaster threatened when a Sean Berry pop fly to short right with two out couldn’t be handled by second baseman Edgardo Alfonzo. Marquis Grissom sped home from second to make it 11-10. Ochoa, who had been on first, tried to tie the game but (after losing a shoe on the basepaths) was thrown out easily by right fielder Roger Cedeño to clumsily end the contest.

After a game like that, the fans at Shea needed a breather. You might say they got it via the ease with which the Mets took the nightcap. As Marty Noble wrote in Newsday, the Mets “played nine innings of dreadful baseball and won in spite of themselves. Then they played nine more and won convincingly. They are the schizophrenic Mets, splitting a doubleheader and sweeping it at the same time.”

So much breath was held and so much action was folded into the late innings of the 11-10 lidlifter, it was hard to remember how the Mets got their first four runs, back when it appeared they were on their way to a laugher. Those initial tallies came in the bottom of the first, on one swing of the bat (when the stadium was almost completely empty) by the Mets’ new-for-’99 third baseman Robin Ventura. That was a nice detail for the box score, but hardly the shining highlight in a game that encompassed 21 runs, 25 hits and 4 errors (three by the Mets, including the nearly fatal miscue by the normally steady Alfonzo). Ventura’s Game One grand slam might have gone completely forgotten except for something he did in Game Two.

He hit another.

Not that the Mets particularly needed it. Second-game starter Masato Yoshii was having a much better night than Leiter, holding a 3-0 lead over the Brew Crew through four innings of work. Still, it couldn’t hurt to have a bigger cushion, so the Mets provided him one.

Agbayani led off the home fourth with a triple…of course he did. As he stood on third, Benny may or may not have realized he had established himself as the most quickly revered cult hero in the history of Shea Stadium. That three-bagger, on top of the two-homer, four-hit performance from Game One, raised Agbayani’s batting average after 28 at-bats to an unfathomable .536. Chants of “BEN-NEE!” filled the air. Hawaiian punch, indeed.

“Benny,” Bobby Valentine said later, “is the player of the week, I guess.”

Yet Agbayani’s sizzle was about to become a secondary story of the doubleheader, consigned to sidebar status alongside Leiter’s frustrations, Ochoa’s misadventures and everything else, including the Luis Lopez double and Cedeño single that upped the Mets’ second-game lead to 5-0. Milwaukee starter Steve Woodard dug himself a deeper hole when he allowed Roger to steal second and third, walked Alfonzo and hit John Olerud with a pitch. He departed the mound, bequeathing a two-out, bases-loaded mess to reliever Horacio Estrada.

Ventura was happy to help Horacio clean up that mess. For the second time in the same evening, Ventura homered with three men on. That made it two grand slams in one doubleheader. As they rose to salute all those RBIs, the Shea faithful buzzed with one overriding question:

“Has anybody ever done that before?”

The scoreboard would post an answer almost as satisfying as the 9-0 lead the Mets now held: no. Those in attendance had just witnessed a major league first. Robin Ventura, in two very different games, had accomplished the same unusual feat: a grand slam in the first inning of the first game; a grand slam in the fourth inning of the second game.

Yoshii took the cushion Ventura gave him and pitched with requisite relaxation through the seventh. Rigo Beltran fired the final two frames — with Jermaine Allensworth belting the sixth Met home run of the twinbill — and the Amazin’s had their schizo sweep, 10-1. Robin, meanwhile, had his singular doubleheader record.

“It was different,” the third baseman reflected for reporters, “because it was two games. You have time to forget about the first one a little bit and actually think it didn’t happen because it happened during the day. The sun was out and now you’re playing a night game and you think it might’ve happened yesterday.”

It was an explanation almost worthy of Yogi Berra, but the knack for hitting with the bases loaded placed Ventura in the company of other baseball immortals. Those homers were the eleventh and twelfth grand slams of his career, most of which had been played with the White Sox. He now had as many as Ken Griffey, Jr., and Mark McGwire and was one shy of his former teammate Harold Baines. Up ahead on the all-time grand slam list were names like Gil Hodges (14), Babe Ruth (16) and all-time National League leader Willie McCovey (18). Whether Robin would eventually catch any or all of them was unknown in May of 1999 (though he would). What Mets fans had figured out for certain after that pair of wins over Milwaukee was they had on their side a guy who could really come through with the bases loaded.

It might be a good skill to call on again.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On May 19, 2006, a large object in the Mets’ rearview mirror turned out to be smaller than it appeared. Randy Johnson — the Big Unit — loomed as large as he had for a generation when he took the mound in the bottom of the first of the first Subway Series game of the season. It wasn’t just because he was the legendary Randy Johnson. It was because he was the legendary Randy Johnson with a 4-0 lead, constructed by Johnson’s Yankee teammates off journeyman fill-in starter Geremi Gonzalez. The Unit was (and wore) 41, but still figured to be a tall order to bring down to size when staked to such a comfortable margin. Turned out the big guy could have used a more immense lead. Carlos Beltran, whose introductory press conference in Queens in January 2005 was trumped on the back pages by the one held in the Bronx for Johnson that afternoon, stole the Unit’s thunder by striking a three-run homer, and before the second inning dawned, the Mets’ deficit was down to 4-3. Neither Gonzalez (3 IP, 6 ER) nor Johnson (5 IP, 6 ER) lasted long in this battle of New York, and it eventually came down to bullpens, specifically closers, each of whom was identified with the same stentorian soundtrack. Wagner, as the home Sandman, entered the arena first and turned out the lights on the Yankees in the top of the ninth, striking out Jason Giambi, Alex Rodriguez and Kelly Stinnett, all swinging, each on four pitches. He was countered by Mariano Rivera in the bottom of the inning. Mo, however, heard no Metallica, only heavy Met hitting: a one-out double by Paul Lo Duca and a two-out long single by David Wright pulled the covers over Rivera and his teammates, 7-6.

GAME 042: May 23, 2009 — Mets 3 RED SOX 2

(Mets All-Time Game 042 Record: 23-28; Mets 2009 Record: 23-19)

What happens when a Monster meets a monitor? One devours the other.

The legendary Green Monster has swallowed its fair share of assumptions in all the decades it has towered over left field at Fenway Park. Its height has turned homers into doubles and doubles into singles. Its relative proximity to home plate has turned fly balls into home runs, left fielders into wanna-be psychics (‘which way is that thing gonna bounce?”) and pitchers into nervous wrecks. The Monster also became one of baseball’s biggest television stars. You tuned into a game from Boston, you were treated to shots of the Monster even when there were no shots at the Monster.

But the cameras that made the Green Monster so famous also came to work against its proprietors one Saturday night when the Mets came to town. Things were going the Red Sox’ way since the first inning, when Kevin Youkilis knocked in two runs to erase an early 1-0 Mets lead. From there, Mike Pelfrey and Josh Beckett traded zeroes, and Boston’s 2-1 lead stood up clear to top of the ninth.

Red Sox All-Star closer Jonathan Papelbon appeared prepared to end it when, after walking Gary Sheffield, he struck out David Wright and Jeremy Reed. The Mets’ last hope was rookie catcher Omir Santos, valued by manager Jerry Manuel for his “short swing”.

When a compact stroke met a wall no more than 310 feet away, good things could happen. But how good, was the question. Omir’s first swing drove a Papelbon pitch to the very top of that old Green Monster, almost into those seats that were added to the ancient structure a few years before. A red line was painted to help umpires make their calls. Balls above the line were homers. Balls below the line were in play.

Third base ump Paul Nauert couldn’t really tell because of the Fenway lights, so he did what Mets fans assumed all umps did when in doubt: he ruled against the Mets, deciding Santos had hit a ball that didn’t clear the line, which limited Santos to second base, Sheffield to third. Nauert’s logic, as communicated by crew chief Joe West, was if he called it a double, he could always change it to a home run later, thanks to one of the great innovations of the 2000s, umpire video review.

This was the process by which the officials huddled out of view of the crowd and both teams and examined, on a monitor, as many replays as the MLB office in New York could transmit to them. If there was ample evidence that a call was wrong, they were empowered to change it. Anyone who had watched armies of the men in blue present an imperious, impervious front to any and all suggestions that they might occasionally make the wrong call, this was truly revolutionary. At Fenway, it gave the Mets hope that they could take an unlikely 3-2 lead off one of the best relievers in the sport.

On the other hand, a machine held their fate, and if technology didn’t cooperate, the game would still be one out from over and the Mets would still be one run behind.

It took maybe five minutes to render a decision, though to Santos, “It felt like I was waiting an hour.” A two-run homer came to those who waited. Yes, the replays did show Omir’s fly cleared that line. Everybody watching at home could see it, but the important thing was the umpires saw it. The Mets led 3-2.

“That’s what the replay is for,” Manuel reasoned.

Perhaps because the depleted Mets had been so close to defeat — and probably because the video delay heightened the drama — Santos’s teammates poured out of the dugout to greet him as if he had just beaten Papelbon on the final swing of the night. But then the Mets were forced to look around and notice they were the visiting team and they still had to get the Red Sox out in the bottom of the ninth inning.

The Mets would have to keep the Red Sox off the board without the help of any friendly monitors and without their All-Star closer. Frankie Rodriguez suffered from back spasms and was at a Boston hospital when the bottom of the ninth rolled around. It was becoming depressing business as usual for these 2009 Mets, who were also without mainstays Carlos Delgado, Jose Reyes and Ryan Church and had to get by with fill-ins like the all-but-retired infielder Ramon Martinez at shortstop. Martinez had made two ugly errors the night before, and Manuel admitted he was back in the lineup only because the Mets had “no options”.

J.J. Putz, taking up the closer role, did his best to let the Red Sox get back their lead when he walked Youkilis to lead off the ninth. Then Met defense — shoddy throughout the previous week in San Francisco, Los Angeles and Boston — took over. David Wright and Luis Castillo teamed (diving stop, shaky throw, excellent scoop) to force Youkilis at second on a Jason Bay ground ball. Angel Pagan, for whom right field was a recurring adventure all season, gloved a tough line drive from J.D. Drew. And then, most surprisingly, the maligned Martinez dove and corralled a grounder from Mike Lowell and fired to Daniel Murphy at first to preserve the 3-2 Met win.

It was a good if ultimately deceptive night for the teetering 2009 Mets. “We’re a little beat up,” Manuel said, “but it looks like we’re going to be OK.” It was a very good night for the previously obscure Santos, who was playing often only because regular catcher Brian Schneider was yet another DL denizen. Omir was making an impression that secured him at least a share of the starting catcher’s job for the rest of the year.

And it was an excellent night for accuracy.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On May 17, 2002, the “pitcher’s best friend” got chummy with starter Steve Trachsel in San Diego. With the Mets leading the Padres 5-1 in the bottom of the fifth at Jack Murphy Stadium, Trachsel allowed a leadoff single to Deivi Cruz and then walked Sean Burroughs. Pads catcher Wiki Gonzalez could have conceivably caused Trachsel trouble with just one swing, but he did the opposite, grounding to Edgardo Alfonzo at third, who stepped on the bag, whipped the ball to Roberto Alomar at second, who in turn relayed it to Mo Vaughn at first. Around the horn in three outs: a 5-4-3 triple play to extract Trachsel from danger. Mets pitchers’ other best friend, backstop Mike Piazza, embellished the box score with a grand slam in top of the seventh, as the righthander cruised from there to a 13-4 win. Offense is nice, but a triple play? Ooh-la-la, said Steve: “That was a beautiful thing. Triple plays are cool. If a double play is a pitcher’s best friend, I don’t know what a triple play is. A sexy mistress?” As much as every pitcher wants to be pals (or maybe friends with benefits) with a triple play, it turns out they’re usually the enemy of good Met fortune. In their history, the Mets have turned ten of them, yet lost the games in which they occurred eight times. Perhaps the prevalence of opposition baserunners is a sign that something is awry. This particular 5-4-3 triple-killing is the last (thus far) to have arrived wrapped in good Mets news. The first? At Shea, against the Astros, on April 15, 1965, an unconventional 9-2-6 TP in which a Jimmy Wynn flyout to rightfielder Johnny Lewis morphed into Houston runners attempting — and failing — to tag up first from third, and then from first.

Thanks to FAFIF reader Sharon Chapman for providing digital audio from the game of May 26, 1964.

by Greg Prince on 19 May 2011 7:46 pm The 2011 New York Mets are the best thing to come out of Buffalo since Scott Norwood’s penchant for kicking wide right.

How many Mets were playing in the vicinity of Lake Erie when the major league season commenced? Half of them? Most of them? However you do the Bison-slicin’, what counts is these Erie Couny refugees made the cut eventually and they’re playing hard by Flushing Bay…very hard.

Fine young fellers, these BuffaMets. Someday soon they could be held up as Exhibits “A” through “Q” in making the case against the Mets’ chronic lack of depth as we inevitably wail over our annual litany of killer injuries, but for now, I’m down with the kids from upstate.

Dillon Gee — he’s here. There was a moment when it appeared he’d be shipped postage-paid back where Gee came from. He gave us those two solid starts in April when Chris Young disappeared onto his first Disabled List. He did what he was asked to do and the assumption was he wasn’t going to be given a chance to outlive his usefulness. Assumptions went asunder, however, and praise be for such Aldersonian reasoning.

Let me take you back to an evening right around this time of year in 2005. There was another three-lettered last-named pitcher on the Mets, Jae Seo. Seo, like Gee, had been brought up from Triple-A to fill in when the Mets had their pitching shorts in a bunch. Like Gee, Seo had a bit of a track record (more substantial, actually). Like Gee did at Citi Field today — and once before — Seo flirted with a no-hitter. All told, Jae gave up just a single in seven innings to the Phillies at Shea Stadium on May 4, 2005.

Any team could use a feller like that, right? Any team except the 14-14 Mets, it turned out. Because Seo was considered a stopgap, the Mets sent him back to Norfolk, that year’s version of Buffalo. No flexibility, no creativity, no recognizing talent or hot hands.

“Maybe if he threw a no-hitter, I might have had second thoughts,” then-manager Willie Randolph said, maybe half-jokingly.

I’ve thought of Seo going as he did because of the way Gee was invited to stick around after Young (briefly) returned. It was D.J. Carrasco who was sent north instead, and it may have been one of the best moves of this particular season. It’s not so much that I expect Gee — potentially a postmodern Rick Reed in terms of command — to make a habit of going 7⅔ and allowing no runs on almost no hits. It’s that a player who could help the Mets in the near term was retained, and another player who wasn’t helping at all was demoted. Gee would have likely wound up back here eventually because of Young’s bum shoulder, but it was sensible as salmon to keep him around in the interim. Ideally, you might want a kid like Gee starting somewhere, like Buffalo, every fifth day rather than being subject to uncertain use in the Met bullpen, but as we’ve learned over and over, the Mets do not operate in an ideal world.

I love that the Mets make that sort of decision now. I love that they (finally) dropped Chin-Lung Hu so far down in the order that he plummeted past Jorge Posada. I love that Ryota Igarashi was advised to rocket toward Niagra Falls when his Rocket Boy repertoire failed to launch. Nothing personal, gents, I just see no need to let poorly performing players absorb roster space when games need to be won…which happens to coincide exactly with the timeframe in which games need to be played.

So no Seo for Gee, and gee, that is so good to know. Other positive or promising personnel shifts may not have occurred because we wanted them to, but how nice that they’re working. Justin Turner would never be playing third base if not for Carlos Lee, but JT handles the hot corner A-OK — and he handles the bat like a maestro. Ruben Tejada would never be playing second base if third and first hadn’t needed to be occupied by second basemen not named Hu, but I need no convincing that Ruben Tejada should be playing second base for the New York Mets. And there may be good reason not to buy Daniel Murphy, briefly a Bison himself in 2010, as a first baseman, but he sure knew how to sell an out call in the ninth to get Thursday afternoon’s 1-0 win closer to satisfying completion.

These Mets as constituted at this juncture are not overly talented. They’ve had the good fortune to line up mostly against other not overly talented conglomerations of baseball players. It’s only fair, I suppose, that the gods who took away Wright and Davis and Young and Pagan and so forth at least gave them the Astros and the Nationals in the past week (not to mention that ridiculously generous out call against Werth; screw him anyway always). The competitive atmosphere, however, is about to take on heavier dimensions. We’re going into a three-game set in an unappealing venue with Justin Turner at third, Ruben Tejada at second, Daniel Murphy at first, Jason Pridie in center, Fernando Martinez DH’ing and a herd of recently transitioned Bisons grazing out in the pen. From now until Sunday night, it will be pointed out to them that they don’t belong on the same field with those they are about to engage.

But the lot of them were already told they didn’t belong on a major league field once this year, so why should they listen?

Oh, and as far as the latest entry to nonohitters.com…c’mon. You knew Liván Hernandez would be the one to break it up. He’s a real hitter…more of a real hitter than most Nats. I once saw him homer — off Jae Seo, come to think of it.

by Jason Fry on 19 May 2011 12:26 am As Mets fan, we know that all too often the jokes write themselves: On Tuesday the Mets canceled a game while the sun was shining, and sat around at home while the evening was more or less dry. Tonight the Mets played on and on, while the rain fell in sheets and the infield turned into a bog. It was like Bishop Pickering in the monsoon during Caddyshack, except no one was laughing. (And happily, nobody got hit by lightning.)

I did have one of my more or less random moments of precognition. After the Nats walked Jose Reyes in the sixth, I entreated Justin Turner to “knock one up the gap, make it 3-0, the ump can put the tarp on, and in an hour everybody goes home.” Well, at least I got the important part right. Turner did as I asked, but Bill Miller remained rooted in place in the rain behind third base, refusing to let anybody do anything except wipe rain out of their faces and hurl wet balls in the general direction of home plate. (I even stayed my hexing of fans on their cellphones waving at the camera. If you were still there after 9:30 tonight in that mess, I hope you called everybody in your contacts list and waved your ass off.)

Why keep playing? I assume Miller was stuck with the same baffling weather-as-videogame forecast we’ve all endured this week, with mist and monsoons and dryness and even teasers of sunshine randomly succeeding each other as the same apparently immortal low pressure system chases its tail around and around the Ohio Valley. That not being any fun, though, Emily and I sought a more interesting answer. Miller, we decided, was some kind of flinty scorched-earth type, a fire-and-damnation ballfield preacher seeking to save players and fans and his umpiring brethren from the fleshpots and booze factories of New York City, the Sodom of the West. “For ye shall not be set free to sin in Manhattan; nay, ye shall play on — and so be purified by the Lord’s heavenly rains.” (For the benefit of dim future Googlers, let me state for the record that this is almost certainly not true.)

Games played in such conditions are almost always close (since otherwise everybody would have been sent home), and so teeter uncertainly between farce and tragedy. Tonight’s followed the blueprint: In the seventh, as things cratered, Jonathon Niese clearly couldn’t control his pitches, batters were peering at them between raindrops, the field was nearly submerged, balls put in play were doing unpredictable things, and no one could run or throw. The Mets were one Roger Bernadina calamity away from descending into a baseball Verdun, and I held my breath as Daniel Murphy grabbed a soaked baseball and set sail for first across a drenched, strangely reflective infield, with Bernadina on a different course for the same destination. Would Murph get there first? Would he drown en route? Happily, he made it. That was enough for me and probably everybody else, but the game continued, with Izzy and K-Rod keeping the Nats down and victory achieved. Will we play tomorrow? Don’t ask — not even the weatherman knows which way this wind is blowing.

Meanwhile, something struck me tonight beyond the immediate business of chronicling: At least for the moment, the Mets are fun to watch again. I know most of that is simply that they’ve been playing better baseball, but that’s not the entire explanation. With Ike Davis and David Wright and Chris Young all shelved, we’re way past Plan B: I felt like I was reading those interminable “X begat Y” sections of the Bible as I explained to Joshua how Murph and Turner and Ruben Tejada had wound up where they were to start play. With half of the Buffalo Bisons in residence in New York, expectations have been adjusted accordingly, and our fan prophecies become self-fulfilling. If the Mets win, they are spunky and gritty and more than the sum of their parts. If they lose, they are snakebit and outmanned and we figured it would happen.

It’s not the stuff of making plans in October, or even meaningful games in September. But it beats the heck out of being pissed off by 7:20 every night. Lets go Mets, whomever that category might conclude on a given soggy evening.

by Greg Prince on 17 May 2011 10:41 pm Welcome to The Happiest Recap, a solid gold slate of New York Mets games culled from every schedule the Mets have ever played en route to this, their fiftieth year in baseball. We’ve created a dream season consisting of the “best” 37th game in any Mets season, the “best” 38th game in any Mets season, the “best” 39th game in any Mets season…and we keep going from there until we have a completed schedule worthy of Bob Murphy coming back with the Happy Recap after this word from our sponsor on the WFAN Mets Radio Network.

GAME 037: May 24, 1973 — Mets 7 DODGERS 3 (19)

(Mets All-Time Game 037 Record: 24-27; Mets 1973 Record: 20-17)

How much coffee was brewed in the name of staying up to catch every last pitch of a West Coast start that became the Mets’ longest win to date? An extra three hours on top of an extra ten innings…Postum wasn’t gonna getcha to the postgame.

Someday Mets fans would rise with five o’clock in the morning approaching to take in a pair of season-opening games from Japan. But that was 27 years into the future. For now, it was enough to hang in there until 4:47 AM to watch the end of a Mets-Dodgers game that didn’t have its first pitch thrown until after 11 PM New York time Thursday and showed few signs of finishing before sunrise Friday.

Tom Seaver faced off against Tommy John, though neither would last past the seventh inning, which is when the Mets, down 3-1, began ensuring a long night would ensue for everybody. Buddy Harrelson doubled home George Theodore to pull the Mets to within 3-2. An inning later, with Pete Richert pitching, the Stork singled home Cleon Jones to tie it.

That was in the top of the eighth. The score would stay rigid for quite a while, though the basepaths would get a workout, starting with the bottom of the eighth. Tug McGraw replaced Phil Hennigan and found himself pitching with the bases loaded and one out. L.A. could go ahead and put the Mets to sleep early, but instead, Bill Russell grounded to Harrelson, who threw home to Duffy Dyer, cutting down the Dodgers’ elusive fourth run. Tug would get out of it.

The theme would be revisited in the tenth. Two Dodger singles and an intentional walk started the home half of the inning, a tangle from which it would be tough for Tug to emerge unscathed. But emerge he did: twice! First, he drew Ron Cey into a 5-2-3 DP that snuffed out Willie Davis at the plate. Yogi Berra ordered a second intentional walk, and it worked again, with pinch-hitter Chris Cannizzaro grounding to Wayne Garrett.

One more chance arose for the magical McGraw to make a Dodger rally disappear, in the twelfth. Hits by Joe Ferguson and Willie Crawford were followed by an unintentional walk to Cey. There was one out. A golden opportunity awaited…and was wasted when Russell touched off yet another play at the plate, another 5-2-3 double play that nailed Ferguson coming in from third.

Thus ended the long evening for the Tugger. He pitched five innings, the eighth through twelfth, gave up four hits, walked five men (two intentionally) and had to overcome a Willie Davis steal of second — with Davis taking third on Dyer’s throw into the outfield — but somehow he went unscored upon. Three plays at the plate all went in the favor of the New York defense.

Tug also singled in the tenth and landed on second on a poor throw by Russell, but was left stranded there.

McGraw did all he could for five, and now the Mets’ portion of the affair was handed over to George Stone for the next six innings. Seven Dodgers reached base between the fourteenth and seventeenth — including two who made it to third — but nobody scored. Stone had pitched only seven innings in 1973 to that point, yet it took a marathon to put him squarely on his skipper’s radar (in California…same state as Oakland).

“You have to give their pitchers credit for the way they got out of all those jams,” said admiring Dodger manager Walt Alston. Meanwhile, Charlie Hough and Doug Rau both kept the Mets at bay as night became day on both coasts and all the players were noticing just how late it was getting.

“I wore out two gloves,” Harrelson reported. “My regular glove and the golf glove under it.”

Rosters were stretched thin, too. Berra used every Met except for a handful of pitchers. Jon Matlack was called on to pinch-run for John Milner at one point, but Matlack, like every other Met, proved allergic to advancement home. On the Dodger side, Davis racked up six base hits in nine at-bats to equal a franchise record that dated back to Cookie Lavagetto in Brooklyn. Manny Mota, on the other hand, might have preferred a rainout. Starting in left field, the pinch-hitting specialist took a size 0-for-9 collar. For the Mets, Garrett was 1-for-2 by the third inning, 0-for-8 thereafter, striking out four times.

The tipping point came in the top of the nineteenth when the Mets’ offense finally loosened up. Jones led off with a single. Rusty Staub doubled him home with his fifth hit of the evening/morning. Pinch-hitter Ken Boswell (batting for Stone) picked up Rusty up and suddenly, after all these hours, runs were coming cheap. The Mets were up 5-3, then 7-3 when Ed Kranepool doubled in a pair.

Jim McAndrew came on for the bottom of the nineteenth, recorded two quick groundouts, gave up a single to pinch-hitter Von Joshua but then induced a grounder from Davey Lopes to Felix Millan. Millan was a 1-for-9 batter on the night, but blissfully surehanded here, feeding Harrelson for the 114th out of the game, five hours and forty-two minutes after it began. The Mets, with 7 runs, 22 hits and 3 errors, defeated the Dodgers, who totaled 3 runs, 19 hits and 3 errors. An estimated 1,000 Angelenos — or 26,000 fewer than showed up in the 8 o’clock hour — were on hand to witness the conclusion of what became George Stone’s first Met victory.

At 1:47 AM Pacific Daylight Time and 4:47 AM Eastern Daylight Time, the Mets had secured their longest win. They had been on the wrong end of a 23-inning score in 1964 and were shut out 1-0 over 24 tedious innings in 1968. For Mets fans who pried their eyes open clear to the end as Friday dawned, that morning’s last or perhaps first cup of coffee tasted anything but bitter.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On May 11, 1997, Mets fans pinched themselves, so to speak. Trailing 4-3 in the top of the ninth at Busch Stadium, Bobby Valentine called on Carl Everett to pinch-hit with one on and one out against Cardinal closer Dennis Eckersley. Everett came through as much as any pinch-hitter could, by belting a two-run homer to right. Butch Huskey came up next, also to pinch-hit. And Huskey also homered off Eckersley. In a span of three pitches, the Mets notched two pinch-hit home runs and three pinch-hit RBIs. John Franco came on and preserved the 6-4 lead to give Cory Lidle his first major league win; finish off a three-game sweep of St. Louis; and, most fortuitously, raise the Mets record to 19-18. After starting the 1997 season at 8-14, Valentine’s club got rolling and had suddenly — almost as suddenly as Everett and Huskey struck — taken 11 of 15 games to claim a winning record. The Mets had ended every one of the previous six seasons a sub-.500 club, and entered ’97 with no expectations that would change. But it was changing, and rising to one win above .500 this deep into the year offered tangible evidence.

GAME 038: May 25, 1981 — METS 13 Phillies 3

(Mets All-Time Game 038 Record: 23-28; Mets 1981/1 Record: 12-25-1)

In what spreads out before a baseball fan as an incredibly long season, sometimes you have to practice self-delusion. If you see anything that looks uncommonly encouraging, you don’t write it off as an aberration — you convince yourself it’s the new normal.

The old normal had nothing to recommend itself where the 1981 Mets were concerned. After 32 games, they were a mind-bogglingly bad 8-24 (yet not in last place, thanks to the even worse 5-26 Cubs). Then, for the first time in what seemed like ages, progress presented itself in the form of four games that resulted in three Mets wins.

For other teams, that’s three out of four. For the 1981 Mets, that was the start of something big…maybe.

But why look a quasi-hot streak in the mouth? On Memorial Day, the defending world champion Phillies visited Shea, and all any one of the blue and orange ilk could ask was that the Mets make it four of five and, perhaps, make visions of a sunny summer not wholly hallucinatory.

Son of a gun, that’s what those heretofore ragtag 1981 Mets did on a brilliant Monday in Flushing. Peer through the box score and you could very easily be blinded by the light.

Nothing didn’t go right, right from the start. After Greg Harris set down Lonnie Smith, Pete Rose and Mike Schmidt to open his second major league start, the Mets went to work on Phils twirler Dick Ruthven. Mookie Wilson walked and stole second. Frank Taveras walked, too. Joel Youngblood singled home Mookie and sent Taveras to second. A struggling Dave Kingman tried his luck bunting, and it worked, at least in the sense that it moved both runners up a base…and that paid off when Lee Mazzilli singled the two of them in. A John Stearns single got Mazz to third, and Hubie Brooks knocked Lee in with another base hit.

Just like that, the Mets were leading the world champs 4-0. Still, maybe there could have been more. Why was Kingman, brought back to New York in Spring Training, bunting? A .200 average will make a home run hitter look for any way to contribute, though as a rule, manager Joe Torre wasn’t crazy about SkyKing flying so close to the ground.

“I asked Joe in Montreal if I could bunt in certain situations,” Kingman said. “He chewed me out. He told me to swing the bat.”

Torre didn’t discipline Kingman after his sacrifice proved instrumental in building the 4-0 lead. Good thing, too, because in the bottom of the second, Dave came up again, this time with no one out and little opportunity to bunt. Mookie had singled, Taveras had doubled him to third and Youngblood was hit by a pitch. Ruthven had to face Kingman with the bases loaded.

Nope, no bunt this time. SkyKing swung the bat, and the next thing anything saw of Ruthven’s decisive pitch, it was landing fair in Loge. Dave Kingman’s tenth career grand slam had just staked the Mets to an 8-0 lead.

“The way I’ve been swinging lately,” Kingman humbly admitted later, “you don’t even think home run. You just try to hit the ball. I’ve been struggling.”

Not anymore, at least not on Memorial Day. Mets fans had grown accustomed to booing their favorite team as they limped out of the gate and their individual numbers sagged. But it was a new day, and cheering was now in vogue. They cheered Kingman as he crossed home plate. They cheered that new apple in the Mets Magic top hat that rose with every Mets home run. They cheered…well, there was much to cheer as the Mets chased Ruthven and held Dallas Green’s troops in check:

• Mazzilli broke out of his Kingman-like slump with three hits.

• Rookie Wilson scored thrice.

• Fellow freshman Brooks added three hits.

• Youngblood was 3-for-3 and raised his average to .363.

• Mike Jorgensen, brought in to give Kingman a breather at first, made a sensational diving grab of Ramon Aviles’s tailing foul pop, landing headfirst in the just-constructed photographer’s box down the first base line.

• Ambidextrous Harris proved handy with his right arm, allowing the Phillies two runs over 5⅔ innings. Mets fans saluted him by putting together both hands as he exited the field.

• Jeff Reardon saved the kid’s first win by retiring 10 of the final 12 Philadelphia batters.

• And between innings, the San Diego Chicken entertained 20,469 patrons who had absolutely nothing to balk at.

The final was 13-3, with the Mets pounding out 15 hits along the way. They were now 4-1 in their last five. And while it still appeared on paper to be a long season, late May was growing legitimately jaunty at Shea.

Things only looked better when, at week’s end, the Mets announced the acquisition of a second proven slugger who would join Kingman and get that apple really bobbing. They traded for right fielder Ellis Valentine of the Expos, one of those “all-around” players other teams always seemed to have. Valentine had suffered a fractured cheekbone a year earlier and hadn’t yet fully recovered his five-tool form, so Montreal chanced dealing him for much-needed bullpen help in the form of Reardon (plus Dan Norman, a would-be Valentine-type who never panned out). Reardon threw hard and had pitched very well for the Mets, but they had Neil Allen to close games, so it was a good risk for the usually offense-starved Mets to take.

In the meantime, the Mets’ tear extended to 7-3 by the end of the month. They had put more distance between themselves and the Cubs, and were a mere six games behind the Pirates for fourth place…and if a fan really wanted to dream, just ten behind the front-running Phillies.

Would the Mets keep it up? Would they continue to take seven of every ten games? Would Valentine truly fortify the lineup? Would there be reason to regret dealing the 25-year-old Reardon? Nothing could be definitively answered in the transcendent giddiness that accompanies a bad team’s good run, but at least one thing became clear soon enough: 1981 wasn’t going to be a long season. In fact, this section of 1981 was about to go in the books as the shortest on record — though it would take some finagling by the Lords of Baseball to create that particular slice of bizarre reality.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On May 16, 2004, Mike Piazza singlehandedly beat Roger Clemens…sort of. He beat him out of a win, even if it didn’t include bloodying him to a pulp (which is what all Mets fans not so secretly rooted for any time the two men were in the same stadium after the notorious events of 2000). Clemens, in his first year as a National Leaguer, had retired to Houston’s Minute Maid Park clubhouse this Sunday afternoon with a 2-0 lead. He had struck out ten Mets over seven innings and was surely counting on collecting his eighth win of the year against zero losses in what had been his eighth Astro start. Although he wasn’t on the mound in the ninth, his old nemesis Piazza ruined his day by blasting a two-out, two-run home run off closer Octavio Dotel. The 2-2 tie meant Clemens — who had won each of his previous eleven regular-season starts, dating back to his presumed final month as a Yankee in 2003 — would not gain another W. Just as sweet for Mets fans, Jason Phillips homered off Brandon Backe in the top of the thirteenth and the Mets went on to a satisfying 3-2 win. The next time Piazza and Clemens would be seen together, it was as the N.L.’s awkwardly aligned All-Star battery at Minute Maid in July. That night, the first time the two foes were thrown together as teammates, American League batters jumped on the Rocket for six first-inning runs. One can only imagine which finger Mike put down when he wanted “his pitcher” to throw a fastball.

GAME 039: September 20, 1981 — METS 7 Cardinals 6

(Mets All-Time Game 039 Record: 18-32-1; Mets 1981/2 Record: 19-20)

To watch the reaction to the stunning climax of this Sunday afternoon at Shea would be to believe you had been invited to the cast party that marked the end of what some would call a forgettable five-year run. Yet nobody who lived through the Mets of 1977 through 1981 — the Joe Torre era, essentially — is capable of forgetting them. It was an intensely memorable time for anybody who stayed with the Mets as they sank, bubbled briefly to the surface and eventually drowned.

But boy, could they toss themselves a goodbye bash. That, in a sense, is what the Mets of the second season of 1981 were doing when they mysteriously crept into an honest-to-goodness pennant race that looked like no other but felt very much like the real thing.

And it was. As odd as it appears that a 39th game of a season could have occurred on a Sunday in September…well, welcome to the second season of 1981. It was different, all right, and for a few weeks, it hinted at greatness.

Mets fans from the Torre era didn’t need any more than a hint, not after five years of being enveloped in cluelessness.

Here’s how we got there:

Unable to reach accord with team owners over free agent compensation, major league players went out on strike on June 12, 1981, freezing the standings in the four divisions. The Mets had played 52 games through June 11 (including one tie). They were hopelessly out of the pennant race, sitting in fifth place with 17 wins and 34 losses. Their predicament was not uncommon. The Mets were one of seven teams at least a dozen games from first place. Thus, when the strike ended and the season was set to resume on August 10, the owners realized they had a problem. It was going to be tough enough to lure bitter fans back to ballparks. To ask them to come see teams that were all but mathematically eliminated with roughly 50 games to go was not one of their marketing skill sets.

So they wiped the slate clean. Baseball declared all games from before the strike constituted a first season of 1981. The teams in first place then — the Phillies, the Dodgers, the Yankees and the A’s — were guaranteed a spot in an expanded eight-club playoff format. They would play the winners of a second season, commencing August 10 and going to October 4 (teams were picking up their schedules as previously assigned).

Thus, when play resumed, the Mets were no longer a godforsaken 17-34. They were 0-0. Everybody was. This second season was totally up for grabs. The Mets theoretically had as good a shot at making the playoffs as anyone.

They took their out-of-the-blue opportunity to heart. After fifteen second-season games, the Mets were 9-6, good for a virtual tie with the Cardinals atop the National League East. The Mets…the Mets who had finished last in 1977, 1978 and 1979, next-to-last in 1980 and were almost certainly going nowhere perceptibly better had 1981 not been torn apart…these Mets were in first place on August 25.

The slate-cleaning was a competitive godsend.

Of course, there’s a reason the pre-strike Mets were 17-34. They weren’t very good, and the edition that took up the second-season cause was comprised of mostly the same players. Same old Mets, in other words. They fell out of first, drifted below .500 and, by September 18, were barely entertaining any notion of contention…even jury-rigged contention. The only thing the Mets had going for them was the Cardinals, still in first, were coming into Shea for three games. If the Mets could somehow sweep them, they’d pull within 2½ of the top spot in the National League East with two weeks to go.

It was a longshot, but these were the Mets of the early 1980s. A long shot was far better than no shot at all.

The Mets won Friday night, 8-1. They prevailed again on Saturday, 6-2. The margin between them and St. Louis was 3½, and the Metsies had edged into third place. Yet it would all be for naught if they couldn’t take the final game of the series. But if they could…

That was the thing. You just didn’t know. You didn’t know this second season was coming in the first place. So why couldn’t first place come when this second season was done?

Seriously, why not?

Well, maybe because the Mets chose this sunny Sunday to leave runners on base like they were empties for the milkman. Except nobody was picking up anything in the early going, and that trend seeped uncomfortably into the game’s squishy middle. Through five innings, the Mets had nine hits and no runs. Eight Mets were stranded. It was Gilligan’s Island out there between first and third.

In the meantime, Pat Zachry — whose arrival in exchange for Tom Seaver was still symbolic of all that had gone wrong for the franchise since June 15, 1977 — came up amazingly small in this do-or-die mission. Zachry surrendered a two-run double to Dane Iorg in the first and a three-run homer to George Hendrick in the third before Torre removed him. The Mets trailed 5-0.

Finally, the Mets’ hits became timely. Ron Hodges and Mookie Wilson each connected for run-scoring doubles in the sixth and the Mets pulled to within 5-2. An inning later, John Stearns, Doug Flynn and Rusty Staub each drove in a run to tie the game at five. Though Zachry had spit the bit, the Mets’ pen had held the fort brilliantly from the third inning on: Ray Searage, Mike Marshall, Jesse Orosco and Neil Allen kept St. Louis scoreless until the ninth.

But in the top of the ninth, after Wilson caught two flyballs, Tito Landrum sent a third over his head. Worse for the Mets, Mookie could not find the handle as it lay on the warning track. Landrum never broke stride, and circled the bases. It was ruled a triple and an E-8.

“Shadows were tough and the ball stayed in the sun an extra second,” Mookie said. “Once I got to the ball, I just dropped it and he kept going.”

So, apparently, would the shadows of failure in which the Mets had been consumed for five long years. The Mets were behind 6-5 going to the bottom of the ninth. For all intents and purposes, three outs remained in their season.

Bruce Sutter came on to close out the win for the Cardinals. His split-finger fastball was working per usual and he grounded Flynn to short and flied pinch-hitter Alex Treviño to center. Now the Mets were down to their last out and their last ounce of hope. The batter was Frank Taveras.

Taveras stroked a line drive to short left for a single. But wait — Taveras, perhaps inspired by Landrum, also never broke stride. St. Louis left fielder Gene Roof gathered the ball and fired to second, but too late to catch Taveras. He could have run himself and the Mets out of contention. Instead, Frank put himself in scoring position.

The next batter was Mookie Wilson, the same rookie center fielder who let Landrum score. “All I was trying to do,” he’d say later, “was keep the rally going once Frank got on base.” Tying the game was Mookie’s goal: “Taveras really hustled to get that double and I just wanted a hit. You have to tie it before you can win it, and that’s all I was trying to do.”

Mookie Wilson tied the game before he won it, but make no mistake about it. He won it. Or as Bob Murphy put it on Channel 9 in his last year broadcasting television as well as radio:

“Home run! Home run! Home run by Mookie Wilson!”

Home run by Mookie Wilson, indeed; the Mets’ 22nd hit of the day. He got hold of a Sutter delivery and sent it over the right field fence at Shea, into the Mets’ bullpen (where it was caught by Hodges, who had been removed earlier for a pinch-runner). Taveras scored for the tie…and Wilson, with four hits in six at-bats on the day, scored for the win.

Mets 7 Cardinals 6. It was the sweep the Mets needed to stay alive in the September no one could have seen coming. They were 2½ out of first place with fourteen games remaining. Never mind they were only 19-20 since play resumed in August. Forget completely that they were 36-54 when you factored in April, May and June. None of that mattered now. The only thing that mattered was the downtrodden Mets of the Joe Torre era had just captured a must win in the midst of their first deep-September pennant race in nearly a decade.

It had been “the most exciting game of my life,” Wilson, 25, declared in the clubhouse. “It was definitely a game to remember. I still haven’t come down. I’m as high as I could possibly be. This was something.”

Something else was even more worth remembering if you were a Mets fan in 1981. The home run itself was amazing. The win was amazing. The circumstances surrounding the standings were totally amazing. But for as excited as the players themselves were — and they all greeted Mookie at the plate — the fans who dared to believe in the second-half Mets of 1981 were beside themselves with joy.

Shea was beset by “pandemonium,” said Murph. A siren could be heard amid the celebration. “Shades of old times at Shea Stadium…like the thrills of ’69 and ’73, the crowd not wanting to leave. They’re enjoying it so very, very much.”

Bob Murphy wasn’t exaggerating. There may have been only a paid crowd of 13,337 at Shea that Sunday, but every Mets fan in attendance understood the stakes. They understood a gift pennant race fell into their laps and they were going to savor every last bit of it.

As Murph continued to wrap things up, much of the crowd was still standing at their seats. Still clapping. Still exulting. This was a year before DiamondVision, before orchestrated cheering began to take hold. This was truly a completely organic explosion of love and gratitude for Mookie, for the Mets, for the assurance that being a Mets fan didn’t necessarily consign a person to a lifetime of futility. It hadn’t felt like this since 1973. It was impossible to know when it might feel like this again.

So why leave?

Murph: “The crowd is just staying here. They don’t want to go home. It’s unbelievable!”

Mets fans had waited so, so long to arrive in a moment like this. Of course they didn’t want to go or let it go. Eventually, though, the moment would be gone. The Mets didn’t capitalize on their sweep, though the Cardinals certainly rued it. The three losses to the Mets would prove devastating, as the Montreal Expos surged past St. Louis to win the second-season crown by a half-game (the Cardinals had the best composite record in the N.L. East in 1981, but by not winning in either half, that was nothing more than trivia). When the second season came to an end, the Mets were in fourth place, and GM Frank Cashen proceeded as if his team hadn’t had its moment.

The Joe Torre era ended. The manager was fired. His coaches were let go. Mainstays Taveras, Flynn, Treviño and Lee Mazzilli would all be gone before Opening Day 1982. The cast was being broken up, and in the long run, there wasn’t much to mourn in that development. Nevertheless, Mets fans who had been winding down, say, eighth grade when Tom Seaver was traded were now in college. The four full seasons and the two demi-seasons in between had been almost uniformly beyond dismal. But during that critical period of life, those Joe Torre era Mets — they were the Mets as this fan base knew them. Taveras. Flynn. Treviño. Mazzilli. Zachry. Swan. Youngblood. Stearns. Allen. All any Mets fan, whatever age he or she happened to be from 1977 to 1981, dreamed of was that group coming together and fighting for a championship.

For one sunny, shadowy Sunday afternoon at Shea Stadium, they did.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On May 27, 1986, the Mets officially became a team opponents didn’t want to screw around with. In the sixth inning at Shea Stadium, with the Dodgers already trailing 3-1, Tom Niedenfuer replaced Bob Welch with the bases loaded. George Foster greeted him with a grand slam. Niedenfuer, whose life hadn’t been too keen since the previous October when he gave up tide-turning home runs to Ozzie Smith and Jack Clark in consecutive NLCS games, took out his frustrations on the next Met batter. It was a really bad idea, since the batter was Ray Knight and Knight was a former boxer and fulltime badass. Knight charged the mound and both teams poured on the field. After a few punches were thrown, two inalterable facts remained: The Mets were winning by a lot and the Mets didn’t take crap from anybody. None of that changed en route to an 8-1 New York victory.

Immense thanks to FAFIF reader LarryDC for providing broadcast video from the games of May 25, 1981 and September 20, 1981.

by Greg Prince on 17 May 2011 1:39 pm I’ll never forget, we used to play a lot of ball out in the front yard, and my mother would say, “You’re tearing up the grass and digging holes in the front yard.”

And my father would say, “We’re not raising grass here, we’re raising boys.”

—Harmon Killebrew, Cooperstown, 1984

Early in my beverage magazine days, I was writing a story that had nothing to do with baseball, but my instinct, naturally, was to inject baseball into it. The subject doesn’t matter now, except that it involved something going on in Minnesota. I had two frames of reference for Minnesota: The Mary Tyler Moore Show and the Minnesota Twins. I wanted to drop them both into my story, but I wasn’t certain of their universality.

So I checked with my editor, who had established his lack of familiarity with baseball for me when I casually mentioned Lenny Dykstra and Bobby Ojeda in my job interview and he stared at me blankly (in the late 1980s, when most New Yorkers’ faces lit up in recognition at those names). Hey, I said, if I mention “Mary Richards” in this story about that bottle bill in Minneapolis, you think people will know what I’m talking about? Sure, he said. Mary Tyler Moore was iconic that way. OK, I thought, I already knew the guy watched a lot of TV, but this is one of those guys who, although I liked him a lot, “didn’t care for sports”.

“What about ‘Harmon Killebrew’? Do you know who that is?”

“Of course I know who Harmon Killebrew is,” my editor — who once watched a World Series ticker-tape parade go by with no idea what the commotion was all about — assured me. “Harmon Killebrew. The Minnesota Twins. Everybody’ll get that.”

With Harmon Killebrew widely and lovingly recalled in the wake of his passing, I thought of that moment specifically and, more generally, how one ballplayer sometimes stands for an entire genre of ballplayer. Harmon Killebrew was The Slugger. Harmon Killebrew was The Slugger from the Minnesota Twins. Harmon Killebrew showed up on American League Home Run Leaders cards. Harmon Killebrew kept working his way up the all-time Home Run Leaders chart. When people who loved baseball talked about slugging, they brought up Harmon Killebrew. When you brought up Harmon Killebrew to people who barely knew from baseball, they understood what Harmon Killebrew meant.

He was synonymous with home runs, and he was synonymous with Minnesota, especially if you had never been within 500 miles of the state. The name “Harmon Killebrew” suggested singles were accidents and triples were unlikely. You’d look up home runs in the dictionary, and you’d find two things: Harmon Killebrew’s picture and a notation to “See also, MINNESOTA.”

That’s what used to happen when players settled in with teams. Tony Oliva was the Minnesota Twins. Jim Kaat was the Minnesota Twins. Rod Carew was the Minnesota Twins. But really, no doubt about it, Harmon Killebrew was the Minnesota Twins. Never mind that he started with the Twins when they were the Washington Senators and that he finished up as a Kansas City Royal. Just as there was no debate over what cap Harmon Killebrew would wear when he was inducted into the Hall of Fame, there would be no question whose face would be pictured on the plaque if the Hall of Fame decided to induct a Minnesota Twins cap.

Harmon Killebrew. Slugger. Minnesota Twins. If I didn’t know a whole lot more about him when he was playing, it felt as if that gave me the entire picture.

Though, eventually, you couldn’t talk about Harmon Killebrew without also at least mentioning beverages.

by Jason Fry on 17 May 2011 1:01 am Remember Back to the Future Part II, in which Biff sneaks back through time to hand his younger self a sports almanac, and so makes himself a mogul in an alternate 2015? If I had a similar opportunity, I think I’d head for Vegas, use my Delorean and make a killing on this game.

1. Odds it’s even being played? Seemed slim given a forecast for this week that suggested gathering useful animals two by two. Then, when game time brought a continuous mist instead of rain, it sure looked like the Mets had shenanigans on their mind: I don’t think I’ve ever seen a general manager inspecting an infield minutes before game time, but there was Sandy Alderson, with Terry Collins and Edwin Rodriguez and Pete Flynn and the grounds crew in tow. Gary, Keith and Ron began openly speculating that the Mets were engineering a rainout, which would likely be followed by a more-natural one tomorrow, which would push this two-game set into a future featuring Ike Davis and David Wright. Seemed good to me, though I had to pause for a very long moment when Joshua asked, “Isn’t that cheating?” (Yeah, pretty much.) But after a lot of mysterious infield work, conspiracy theory debunked and game on.

2. Odds Mike Pelfrey would outduel Josh Johnson? OK, it was more of a draw, thanks to Pelf surrendering a cloud-piercing shot by Mike Stanton, whom I may soon come to particularly dislike for beating us while reminding me of Mike Stanton, warm-body reliever who made no secret of the fact that he preferred being a Yankee. (Minor point in Stanton the Elder’s favor: He once referred to the American League as “a beer league.”) Still, Pelf was impressive yet again, continuing a string of solid starts that of course began once our collective fan needle swung over to “Given Up on Him.” Johnson had an off-night — which, being Josh Johnson, meant he was merely very good.

3. OK, I bet you Jon Niese winds up with more triples than Jose Reyes. Niese? Ha ha, he’s not even starting! That one alone would have funded my own island with a hidden submarine base and a menagerie of lap giraffes. (Even though Emilio Bonifacio dropped it.)

4. Perhaps Willie Harris will win it. Or at least have a moment. Pressed into service at third with David Wright the latest Met felled by invisible ninjas, Harris looked like the Nationals’ version of himself, going airborne to make a terrific lunging catch and showing sure hands on a couple of tough chances. I decided that this would be the night’s theme, and that Harris would indeed have his moment, winning the game in the bottom of the ninth. But Collins pinch-hit for him, bringing in Chin-lung Hu as a right-handed bat instead, though Hu’s baseball card should really say “Bats: None.” That’s a bit unfair, as Hu smacked a Randy Choate pitch up the middle, but to no avail. (Update: Terry won’t be doing that again for a while.)

5. Weren’t you worried Hanley Ramirez would be the death of us? Of course I was. So were you. I wanted to scream when Terry had K-Rod intentionally walk Chris Coghlan to get to him in the ninth. It worked out, not that that made it a good idea.

6. Can even a man who has his own island and lots of lap giraffes be happy with just ONE submarine base? Good point. Excuse me while I go back in time with this blog post and this ESPN play-by-play info. Hmm, I wonder what the odds are on a Justin Turner grounder hitting Ramirez in the shoulder for an apparent Mets win, only to bounce perfectly to Omar Infante for a smooth-as-silk 6-4-3 double play?

7. How about the odds of Burke Badenhop collecting the decisive RBI? Burke Badenhop? Sure, he’s got one of those ya-gotta-be-kidding-me baseball names, but isn’t he 1-for-23? Holy Rick Camp, Batman. Ah well, more lap giraffes for me.

8. You seem awfully chipper considering Wright’s going on the DL, two pitchers had season-ending surgery and the Mets lost a cruel, cruel game tonight. Look, some games let their freak flags fly from the get-go, and this was one of them. Those several hundred diehards out there spent the night peering through mist at a theater of the absurd. Games like that, you just let go and see where the ride takes you. Great plays, weird plays, some skullduggery, a very long home run, unlikely pinch-hitters, and never knowing what’s coming next? I wish we’d won, but I can’t deny that I was hugely entertained on the way to not winning.

But do me a favor in the future — don’t say “chipper.”

by Greg Prince on 16 May 2011 4:36 pm David Wright is one second opinion away from going on the Disabled List. MRI revals lower back stress fracture. Examination of Mets roster reveals no obvious alternatives for third base or the batting order. True, he was mostly sucking, but just as true, he’s David Wright.

Rest is allegedly what’s required to get this injury better. Also, Ryan Church should be ready any day.

Sorry, reflexive Mets fan injury-related cynicism and dread kicking in. Hope it doesn’t kick too hard, because then I’ll be day-to-day.

Feel better, kiddo. That run for the senate can wait.

by Greg Prince on 16 May 2011 12:46 pm The Mets aren’t bad unless you’re a strict constructionist who sees a team with more losses than wins as definitively not good. Nineteen wins against twenty-one defeats is sub-.500. It doesn’t look great in isolation (or when you pull the 19-21 apart and notice the Mets are 8-14 against teams currently above .500).

Within the context of how the 2011 season has unfolded, however, it’s damn good. When the Mets were 5-13, it felt highly unlikely that we’d be watching a team that was about to post almost the National League’s best record from that point forward, up to and including this very moment.

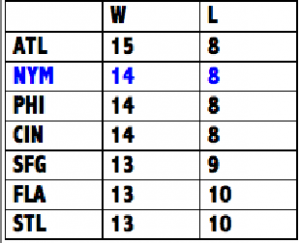

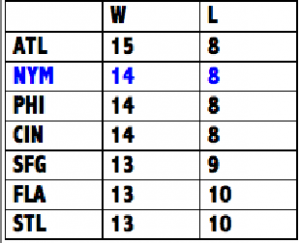

From April 21 through May 14:

Surely that’s encouraging. It’s a better trend than that we were riding before. But it’s also a trend. Seasons are comprised of trends. We’ve already seen several in 2011, as broken down by bundles of wins and losses:

3-1

2-12

6-0

1-5

7-3

As fans, we are entitled to grow overjoyed/disgusted with every twist and turn the schedule takes. Still, when the bottom line after 40 games is 19-21, or just about even, we might want to go with “not bad…not great” since there’s no guarantee that the latest upward trend is the definitive one.

A quarter of the season theoretically seems like a reasonable sample from which to draw conclusions about the overall direction of where 2011 will go. But that’s probably just theory. Consider not just how much the year thus far has twisted and turned in terms of winning and losing, but how the composition of the team keeps resetting itself.

• Josh Thole was the everyday catcher. Now he’s more or less in a platoon with Ronny Paulino.

• Ike Davis was the everyday first baseman. He got hurt.

• Daniel Murphy was a man without a position. Then he became the part-time second baseman, then pretty much the regular second baseman. Now, because of the injury to Ike, he’s the starting first baseman — for a while.

• Brad Emaus was the everyday second baseman. He’s gone. He gave way to Murphy and Justin Turner. In the short term, it’s mostly Turner’s position.

• Jason Bay was out for several weeks and left field was juggled unsuccessfully by Willie Harris and Scott Hairston. Bay is back, though there’s talk he may shift to center.

• Angel Pagan has been out for several weeks. Jason Pridie has more or less commandeered his position, subject to change.

• Other than Jose Reyes batting leadoff, David Wright batting third and Carlos Beltran hitting cleanup, the lineup has been in continual flux. The two-hole has been occupied by six different players. Thole, Turner and Harris have each batted in three different positions.

• Injury has removed one of the projected five starters (Chris Young) from the rotation. Inconsistent results notwithstanding, starting pitching personnel has managed to remain fairly stable. But the bullpen, except for Frankie Rodriguez closing, has evolved and morphed from the first week on.

• Through one circumstance or another, D.J. Carrasco, Blaine Boyer, Bobby Parnell and Tim Byrdak have each disappeared or been diminished. Pedro Beato earned greater responsibility sooner than envisioned, then he got injured. Jason Isringhausen reappeared and took hold of the eighth inning, a spot initially reserved for Parnell. Ryota Igarashi seemed to be working his way up the ladder, though lately may have slipped a rung. Only Rodriguez, Byrdak and Taylor Buchholz have been in the pen since Opening Night.

It’s been a roster in flux, a lineup in flux, a defense in flux and a relief corps in flux. But y’know what? That happens. That happens probably every year to some extent. Injuries and disappointing performance are nothing new to any Mets fan who’s been paying even moderate attention the past few years.

Baseball seasons are what happen while you’re busy making other plans. That’s why I can’t full-out look at the 14-8 since 5-13 and say, “That’s what the Mets really are.” The Mets have achieved their turnaround while in constant motion. The team that beat Houston two of three over the weekend isn’t wholly the same team that won six in a row in April — not in composition and not in form…not when so many roles keeps shifting.

They’ve had to shift. Players have gone down and players haven’t performed. Standing pat was not an option for Terry Collins, and he’s reshuffled the deck on the fly pretty much as best he could. It’s gotten him close to .500 less than a month after they seemed destined to drift inevitably south of that mark.

They’ve done it with their presumably best player, Wright, aching and almost not hitting at all. They’ve done it with their technically most vital slugger, Bay, not really slugging. They’ve done it having lost the services of their blossoming first baseman, Davis, and with their square peg, Murphy, squeezing himself into one round hole after another.

They’ve gotten more out of Beltran than could have been reasonably requested and they’re getting almost ideal production out of Reyes. It’s compensated for the ups and down of a young Thole and the uninterrupted downs that beset Pagan prior to disabling. That’s two everyday players who have exceeded expectations compensating for two projected everyday players who haven’t fully (or partially) lived up to them.

What if Pagan comes back and returns to his 2010 form? What if Thole builds on his successes and gains the confidence sufficient to limit his failures? Will Reyes still be running wild and Beltran still be smoking? If Wright comes around, will it be when Murphy slumps? If Bay gets it together, will it happen when Davis is back, and will Davis come back the same Ike as he was when he was at his best?

I don’t know. Nobody does. There really isn’t enough of a composite trend to be drawn out of the partial and individual trendlets, if you will, to say the Mets sure are on the right track, or the Mets can’t possibly keep this up. And then throw in that the roster rejiggering we’ve seen thus far may be of the “ain’t seen nothing yet” variety pending the trade deadline and all it implies in 2011.

All this is said without getting into the bench, which has either been a fine resource in terms of contributing useful fill-in starters or a terrible liability when it comes to extracting the occasional pinch-hit. It also overlooks the frightening fluctuations of Pelfrey, Niese, Gee and Dickey, three youngsters and one odd knuckleballing duck who have shown no reliable patterns of performance through forty games (except for R.A. being a Pagan-level disappointment). Bullpens and their inherent mysteries are a perennial given.

The not knowing is pretty standard, but the not truly sensing is particularly acute. We can make judgments based on past performance as constituted by one-quarter’s worth of performance, but I doubt they’re going to tell us a whole lot that can guide us to understand even partially what the next three-quarters hold in store.

Which is why we should really take care to watch these games, one game at a time.

***

Although one season differs from another in a style generally attributed to snowflakes, I wondered whether 40 games have traditionally offered any kind of Met clue for what the remainders of seasons past have brought us. So I looked — went back to the 40-game mark of every Mets season since 1962, excluding strike-torn 1981 and strike-truncated 1994. For 1972 (156 games) and 1995 (144 games), which we knew, once they started, would contain fewer than 162 games, I used a slightly smaller quarter-season sample size (39 and 36, respectively).

Do the Mets generally give us a reasonable accounting of themselves at the quarter turn? Is a 19-21 start — a .475 winning percentage — necessarily predictive of 77-85 final record…also a .475 winning percentage?

Sometimes. Which is to say not necessarily.

METS TEAMS WHOSE HELLACIOUS STARTS

WERE PREDICTIVE OF MAGNIFICENT RECORDS

The 1986 and 1988 division winners rolled out to 29-11. They couldn’t main that pace but they didn’t have to. 108-54 and 100-60, respectively, were quite sufficient. Nobody wins 72.5% of 162 games, after all. The 25-15 1985 Mets kept it up as such to get near 100 wins (98), if not close enough to first place in those pre-Wild Card days. At 24-16, the 2006 Mets were on track to wind up with 96 wins; they wound up with 97, gripping first place in the process.

METS TEAMS WHOSE HELLACIOUS STARTS

PROVED A FRUSTRATING MIRAGE

The 1971 Mets’ lack of offense caught up with them after a 25-15 launch; they finished an indifferent 83-79. The 1972 Mets seemed destined for greatness at 28-11, but they were dinged to death by injuries and lost 186 points off their winning percentage before whimpering out the door at 83-73. The 2007 Mets wasted an impressive 26-14 en route to an ultimately historic fizzle (88-74).

METS TEAMS WHOSE MIDDLING STARTS

BARELY HINTED AT GREATNESS TO COME

The 1969 Mets were 18-22 after 40 games, the kings of the world before long; the 100-62 eventual world champions were one of only two Mets teams to lose as many as 22 of their first 40 decisions and finish with a winning record. The 1999 Mets were 22-18 and in a bit of a rut around the quarter turn. They’d turn it on and stay turned on to make the playoffs at 97-66. In 2000, the 20-20 Mets were still waiting to take off toward 94-68 and the World Series.

METS TEAMS WHOSE MIDDLING STARTS

NEED TO BE UNDERSTOOD IN CONTEXT

The 1973 Mets were 20-20, a dead-on .500, and they finished the year .509 — but also with a pennant, so You Gotta Believe the rest of the N.L. East helped out by not being very good. The 1984 Mets were 22-18, or .550, and ended up .556, which doesn’t sound like much of a bump, but it meant 90 wins, second place and a renaissance. The 1987 Mets, on paper, got their act together, rising from a disappointing 19-21 start (.475) to win 92 games (.568). But not finishing first the year after 1986 couldn’t help but represent a massive letdown. At 19-21, the 1990 Mets were about to cost Davey Johnson his job; by ending 91-71, they made Bud Harrelson look like a Leader of Men. The .500 mark of the 1997 Mets was part of a seasonlong upward swing to 88 wins. The 2008 Mets would go on to play a little better than their 21-19 start presaged, but not better enough (89-73, blowing both the Wild Card and the division).

METS TEAMS WHOSE MIDDLING STARTS

WERE PRETTY MUCH REPLICATED ALL SEASON

These Mets got to 40 games with between 19 and 22 wins and wound up over .500, but didn’t garner enough momentum to create a resounding/uplifting stretch run: 1970 (19-21; 83-79); 1975 (21-19; 82-80); 1976 (22-18; 86-76); 1989 (22-18; 87-75); 1998 (21-19; 88-74); and 2005 (21-19; 83-79). Some edged closer to glory than others, but none ever fully got over their quarter-turn flirtation with mediocrity.

METS TEAMS WHOSE DECENT STARTS

EVENTUALLY TURNED IRRELEVANT

A pox on those Mets who threw it all away: 1982 (22-18; 65-97 — the loss of 149 percentage points from the quarter turn to the finish line is the second-worst in Mets history, behind only 1972); 1991 (22-18; 77-84); 1992 (22-18; 72-90); 2002 (21-19; 75-86); 2004 (19-21; 71-91); 2009 (21-19; 70-92); and 2010 (19-21; 79-83).

METS TEAM WHOSE TERRIBLE START

CAST AN IMPOSSIBLY STUBBORN SHADOW

The 2001 Mets couldn’t defend diddly, let alone their 2000 National League championship through 40 games, limping to a dreadful 15-25 start. Amazingly, they finished up over .500 at 82-80, a 131-percentage point in-season improvement, second-best to only 1969’s Miraculous 167-point gain.

METS TEAM WHOSE SUB-.500 START AND FINISH

DESERVE A PASS IN CONTEXT