The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 19 November 2010 6:00 am Welcome to Flashback Friday: Take Me Out to 34 Ballparks, a celebration, critique and countdown of every major league ballpark one baseball fan has been fortunate enough to visit in a lifetime of going to ballgames.

BALLPARK: Wrigley Field

HOME TEAM: Chicago Cubs

VISITS: 4 games, including 1 doubleheader

FIRST VISITED: August 3, 1994

CHRONOLOGY: 13th of 34

RANKING: 5th of 34

When I was nine years old, I briefly held quite the clever theory, namely that everybody famous did not exist. When we saw Tom Seaver on television, it was some kind of setup, I figured. How could it not be? How could anybody so much larger than life actually be living in the same life that we regular people lived?

I tried this theory out on my mother. She was good enough to shoot it down pretty quickly and plainly. No, she said, they’re real; who do you suppose is in those pictures anyway?

Ultimately, I couldn’t argue with that — I’ve always done better with logic than conspiracies — but still, it was tough to conceive that anybody or anything fantastically famous could be something you could just come upon. It’s probably why when I looked down from the Excelsior level at Citi Field and saw Tom Seaver walking through the Delta Club stands last June in civilian clothes (as, ironically, part of the nightly salute to military veterans), it was kind of shocking. I walk through the stands in civilian clothes. I’m a regular person. Tom Seaver is like a person-plus…y’know?

It’s that same concept of what’s real and what is simply too big a deal to be real that hit me the first time I approached Wrigley Field. I’d been aware of Wrigley Field for the previous quarter-century. I viewed it on TV at regular intervals every year. It was as photographed and filmed a ballpark as had ever been. It’s that same concept of what’s real and what is simply too big a deal to be real that hit me the first time I approached Wrigley Field. I’d been aware of Wrigley Field for the previous quarter-century. I viewed it on TV at regular intervals every year. It was as photographed and filmed a ballpark as had ever been.

Yet there it was, on the street, in Chicago, right in front of me.

In some ways, I still can’t believe it.

***

To say there is nothing like Wrigley Field is one of the more obvious statements one can make about ballparks, but perhaps it is more telling for me to tell you that when I was growing up there was nothing like Wrigley Field. I watched the Mets play eleven different opponents annually and only one of them held its home games in a facility that appeared completely different from all the others.

Shea was Shea and everything else looked like everything else, just about. Dodger Stadium had those seats behind the netting that lined up right behind home plate, and the Astrodome was clearly indoors, what with its weird lighting, and once the Expos moved out of Parc Jarry, you couldn’t help but notice the lingering track markings of Olympic Stadium, but mostly it was all a blur of Mets gray and road game bland.

But not Wrigley. Wrigley was a break from the sameness. Wrigley belonged somewhere. Our announcers talked about Wrigley like it was something more than a baseball stadium, like it was…like it was somewhere. Dave Kingman (for us, against us and then again for us) hit balls on to Waveland Avenue. If he were a lefty, he would have hit them onto Sheffield Avenue. These were streets on the North Side of Chicago, where the wind might blow in from Lake Michigan, but if it didn’t…watch out, ’cause Dave Kingman was goin’ to town.

I knew about Chicago geography because the Mets played nine games a year at Wrigley Field. I knew more about Chicago geography than I knew about any other city’s, and I had never been there. I knew Wrigley Field’s address was 1060 West Addison because that’s the address Elwood Blues claimed as his own in The Blues Brothers. Did other ballparks even have addresses? Did Ralph, Lindsey or Bob ever mention the names of the streets behind left field at Veterans Stadium?

Wrigley Field was somewhere and it was definitely something. Only Wrigley had ivy. Only Wrigley had that hand-operated center field scoreboard. Only Wrigley had day games and, for the longest time, nothing but day games. Only Wrigley kept its capacity way below 50,000 (it wasn’t even close). Only Wrigley had Bleacher Bums. I read about them and I didn’t like them with their hating on hippies and throwing of beer, but they were identifiable. Who sat in any part of Three Rivers Stadium? Who knew? Nobody ever talked about any other ballpark in the National League the way everybody talked about Wrigley Field.

And the damndest thing was how long it had been there. Built in 1914 for the Chicago Whales of the Federal League as Weeghman Park, it became home to the Cubs in 1916 and changed its name to reflect Cub ownership in 1926. By then, the National League lineup of ballparks was well set for the next half-generation: Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis; Forbes Field in Pittsburgh; Crosley Field in Cincinnati; Braves Field in Boston; Ebbets Field in Brooklyn; the Polo Grounds in Manhattan; the Baker Bowl in Philadelphia; and Wrigley Field on the North Side of Chicago. In 1938, the Phillies abandoned the tin-fenced bandbox to share Shibe Park with the A’s. With that switch, the octet of N.L. home fields remained unchanged clear through to 1952.

None of those buildings has seen major league baseball action since 1970. None except for Wrigley.

You can pick any spot you like in the last 95 years and reach a similar conclusion. In the year before the first National League expansion in 1962, the senior circuit’s ballparks of record were Crosley, Forbes, Shibe (renamed Connie Mack Stadium), Sportsman’s (renamed Busch Stadium, predecessor to the round version), County Stadium in Milwaukee, the Los Angeles Coliseum and the recently opened Candlestick Park…and Wrigley Field. No baseball in any of those places not named Wrigley since 1999.

For sixteen seasons, from the day the Expos took up uncomfortable residency at the Big O in 1977 until the next expansion kicked in, these were your stadia: Three Rivers, the Vet, Riverfront, Busch II (the circular one), the Astrodome, Fulton County, Jack Murphy, Candlestick, Dodger Stadium, our very own Shea Stadium, the aforementioned Big O…and Wrigley Field. Only Dodger Stadium has survived to keep Wrigley Field company on the National League schedule. And once the Marlins slide southward from their overly named facility in Miami Gardens to their as yet unnamed park in Miami proper, both ballparks from the 1993 expansion will be off the N.L. map.

By 2012, the National League ballparks with the longest stretch of continuous use by their primary occupant will be:

1) Wrigley Field, since 1916

2) Dodger Stadium, since 1962

3) Coors Field, since 1995

Or, to put it another way, starting with 1916 and running through the season after the next one, 14 National League franchises will have played regularly scheduled home games in 40 different venues, including two (the Polo Grounds and County Stadium) that were used by two different N.L. clubs. The only teams to call only one place home will be the Cubs and the Arizona Diamondbacks…who came along a mere 82 years after Wrigley Field took in its apparently permanent tenant.

To say ballparks come and go from our midst is an understatement — and an inaccurate one when applied to where the Chicago Cubs play.

Wrigley Field not only perseveres, it preserves. Catch a glimpse of it in a newsreel from the 1930s and it appears not much different from the Wrigley you’ve been seeing on TV all your life. Its vicinity may have grown more commercial, and various owners may have upped the modernity ante here and there, but when you look at it, Wrigley is still Wrigley.

Television opened my eyes to Wrigley, but Wrigley wasn’t made for TV. It was made for me to go see for myself. That was the goal for many years. Long before I fathomed I could, as a matter of course, visit ballparks other than Shea, well in advance of my fashioning a dream of seeing as many ballparks as I could, there was only one that was specifically on my must-go list.

I already knew where it was. Now I just had to get there.

***

Maybe, as the Fox promos from a few years back put it, you can’t script October, but Stephanie and I scripted our first multipark journey in the summer of 1994 exquisitely. Land in Chicago on Saturday. Visit the overwrought sequel to the late Comiskey Park on Sunday. Tool up I-94 to Milwaukee, the main Miller plant, Edwardo’s phenomenal stuffed pizza and homey County Stadium on Monday. Tool back down I-94 on Tuesday, take in something that has nothing to do with baseball — in our case, the Art Institute of Chicago — so we don’t seem overly one-track minded. And then, as if to build to a crescendo, you save the best for just about last.

Wednesday was Wrigley Field day…day, to be sure. Night games had been around the North Side since 1988, and I’m sure they served a purpose, but they didn’t serve mine. I could go to a night game anywhere. This was the day I’d been waiting some 25 years for, ever since I first heard of the Cubs and decided I didn’t like them. By 1994, the Mets and Cubs had been separated, made to sit in separate divisions, perhaps a result of them having talked too much and disturbing their N.L. East classroom. It was too bad. I loved the Mets-Cubs rivalry, from when it worked out well for us (1969) to when it didn’t work out well for either of us (1970) to when nature displayed its bizarre sense of humor (1984, 1989) and gave the Cubs a break at our expense.

The goal was to see Wrigley Field. The übergoal was to see the Mets there, preferably on a Friday afternoon (where else did they play on Friday afternoons?), with the Mets and Cubs battling it with something on the table (instead of merely knocking around that basement co-op they shared in the late ’70s and early ’80s) and, as long as we’re dreaming, make it a doubleheader, the way Ernie Banks would. That wasn’t happening this afternoon on the North Side. I’d have to settle for the Cubs and the Marlins, just one game.

I could handle that. I could even handle taking the bus to the ballpark, an option I had never considered outside of a camp trip to Shea. Stephanie and I began our Wednesday with a detour to the Chicago Historical Society — everything on this vacation felt like a detour once Wrigley loomed as our prime destination — and when we stepped outside to make our way to the El (the elevated line to Wrigley…that was part of the übergoal, too), a bus appeared that was headed to where we needed to be.

Imagine that: you get on a city bus and it just happens to stop a ballpark that’s been in operation since 1914, and the ballpark is where some people get off because their team has playing home games since 1916, and it’s where they go the way the rest of us go to our ballparks that, whatever their charms, are not Wrigley Field.

But this, once off the bus, was exactly that. It was Wrigley Field.

It was really here, right where Elwood Blues said, at the corner of Clark and Addison. It was really here, with the red marquee, clarifying that the Chicago Whales of the Federal League had long gone off to sea, that this was, no doubt about it, WRIGLEY FIELD HOME OF CHICAGO CUBS.

It was really here. Buses rolled by. A McDonald’s was across the street. Bars were nearby, too. Somebody I interviewed a couple of weeks earlier, from a beer importer, told me they had an account he could recommend where we could stop in before the game for a cold one.

Like I needed a cold one. I had Wrigley Field in my face. I was already intoxicated.

***

The Cubs, after thieving two division titles from the Mets in 1984 and 1989, went through phenomenon phases, as if Wrigley Field wasn’t phenomenal enough. Lee Elia’s caustic 1983 appraisal of critical Cubs fans — “Eighty-five percent of the fuckin’ world is working. The other 15 come out here.” — proved prophetic, in a way. There were times when it seemed 15% of the world was filing into Wrigley Field. Day games, night games, didn’t matter. Word was you couldn’t get a ticket.

1994 was not one of those years. We got the tickets pretty easily (ordering them “online” for novelty’s sake) and there were still plenty left when we arrived. Paid attendance for our first game at Wrigley was a little over 26,000, not the crowd scene I’d anticipated.

Which was fine. I didn’t want a scene. A scene I could get on television. I caught Wrigley when it was relaxed, when it was just a ballpark with two ballclubs playing one ballgame as might have been going on in just about any year since 1916. There was nothing on the table for the Cubs or the Marlins. I could sit back with an Old Style and take that in with ease.

Here’s what I remember about the ballgame itself: almost nothing. Here’s what I remember about Wrigley Field: almost fainting from how beautiful it was. Our seats were great. Maybe all seats there are great, but these definitely were. Got a great downstairs panorama of Waveland over there and Sheffield over there, and the ivy in the foreground. Jesus, there’s really ivy on that wall! It wasn’t a photographic illusion. It was small yet it was grand. The players were close by. Harry Caray led us in “Take Me Out To The Ball Game.” The wind blew out more than in. The Cubs scored eight. The Marlins scored nine.

Didn’t matter what either team did. The day was a dream. I was enthralled. Stephanie, to date a modestly interested observer on these sojourns, was enchanted. She loved Wrigley Field enough in 1994 to stop and watch every Cubs home game that has come on TV since. Hasn’t made her a Cubs fan (lord help her if it had) but she knows the place as any baseball fan would.

We walked around the park afterwards. We took the El back downtown. We went for German food that night. We flew home the next day.

What could be better?

Four years later. That’s what.

***

GOOOAAALLL!!!

No, strike that.

ÜBERGOOOAAALLL!!!

It’s 1998, and my fondest Wrigley Field wish is about to come true. I am about to get everything I ever wanted. And for that, I have two entities to thank.

1) Nature, for raining out a Mets-Cubs game in April (a makegood for that bizarre behavior from ’84 and ’89).

2) Jeff, for everything else.

Jeff has made a few cameos in these ballpark chronicles, but now it’s time you meet him in full. It’s all right that it’s taken this long. It took me a while, too.

We were what you’d call ships who passed in the night. Technically, we passed in the day, which was appropriate, given we’re talking about Wrigley Field. In March 1989, I was interviewing for my new job with a beverage magazine on Long Island, almost stumbling into it. When I inquired about openings by phone, I was thinking freelance. The editor said they had a fulltime position newly available. It had been, up to that week, Jeff’s. He was moving on, to Chicago, to a dairy magazine. When I first came in, Jeff was still at what was about to become my desk. We were introduced, we shook hands, and that was that.

Fast-forward a year-and-a-half later, to a trade show in Chicago. Jeff dropped by the convention center to say hi to his old friends from the beverage magazine. I wasn’t one of them, but he was friendly toward me nonetheless. In our first brief chat since our earlier handshake, the subject of baseball came up (funny how quickly that happens in my conversations). I said something about envying his locale given the ballpark geography at his disposal. Well, Jeff said, next time you’re in Chicago during the season, look me up and we can go to a Cubs game.

For a few years thereafter, I’d see an article in the Times about milk or one of its related products, clip it and mail it to Jeff. He would reciprocate with a clipping about soft drinks from the Tribune. No biggie. Then one day I received a beverage article from Jeff with the news that the last dairy story I sent him was forwarded to him at home. He hadn’t been with that magazine for a while and, since his daughter was born, he had taken up a life of freelancing. I snapped up his editorial services until he moved back into fulltime employment. Of more lasting significance, we developed a baseball-centered line of communication. I was a Mets fan, he was a Tribe fan (originally from Ohio) but our common ground was our love of ballparks and our desire to see as many of them as often as we could.

Somewhere in there, the “next time you’re in Chicago…” invite, which I had never forgotten, remained alive, especially since Jeff’s new job was with the company that owned — wait for it — the Chicago Cubs.

We were pretty good e-mail buddies by early in the ’98 season when rain fell on Wrigley and a single Mets-Cubs game in July was rescheduled into a Friday doubleheader. Hey, Jeff suggested, maybe you can come out for that.

Yes, maybe I could.

Jeff worked his levers and I did what I had to do. A public relations person was delighted to hear that (ahem) I would be in town in late July and would love to drop by and visit with her client. Whaddaya know, they’d love to have me! There — I had an official reason to be in Chicago, and let my magazine know I had real important business in the Midwest, I’ll be out of the office toward the end of that week (such initiative I was mysteriously showing). I flew out on a Wednesday night, checked into a hotel near O’Hare (with decent if staticky AM reception of the Mets-Brewers game from Milwaukee; Bob Uecker referred to our manager as “Bobby Valentin”) and devoted Thursday to making sure the dream would indeed manifest into reality. Jeff worked his levers and I did what I had to do. A public relations person was delighted to hear that (ahem) I would be in town in late July and would love to drop by and visit with her client. Whaddaya know, they’d love to have me! There — I had an official reason to be in Chicago, and let my magazine know I had real important business in the Midwest, I’ll be out of the office toward the end of that week (such initiative I was mysteriously showing). I flew out on a Wednesday night, checked into a hotel near O’Hare (with decent if staticky AM reception of the Mets-Brewers game from Milwaukee; Bob Uecker referred to our manager as “Bobby Valentin”) and devoted Thursday to making sure the dream would indeed manifest into reality.

The hotel had a shuttle to the airport. The airport had a light rail terminal with a train that took you into downtown. Bam, I’m there. I meet Jeff at his office…first time I’d actually seen him in eight years, third time I’d shaken his hand ever. He introduced me to several co-workers as the Mets fan he’d be going to the game(s) with tomorrow.

And every one of them sneered. Playful sneers, friendly sneers, but a definite undertone of animus. They didn’t like the Mets anymore than I liked the Cubs.

Which I loved. They still resented us for 1969. 1984 and 1989 didn’t do a thing to salve their souls. For a moment in 1998, I was the embodiment of all that had gone wrong in their baseball lives. They actually cared about the Cubs and the Mets the way I cared about the Mets and the Cubs.

My existence was validated.

Jeff and I had a nice lunch, he handed me my ticket for the next day (he’d meet me at our seats after a half-day of work, a very Chicagoan thing to do, I thought) and he pointed me in the direction of my appointment. Right…I had to go interview somebody to justify this wonderful boondoggle. No problem, I could do that.

***

Friday dawned hot and sunny. Perfect. The shuttle to O’Hare was at my door. Perfect. I knew exactly where I was going by CTA. Blue line to downtown. Transfer to the Red line uptown. Lots of Cubbie blue on the Red, and just a little Mets blue…mine.

“Mets fan, huh?”

Spotted. And guilty. And wearing HUNDLEY 9 on my back. Took a bit of ribbing from my trainmates over how non-adept our new left fielder was with fly balls. Todd Hundley, the conversation went, what a joke.

Which I also loved. Not the part where Todd Hundley couldn’t catch a wave if he were a Beach Boy; that part sucked in the overarching quest for the Mets to snag the 1998 Wild Card. I loved that these Cubs fans knew what was going on. That they knew from Hundley’s travails. That even if they were too young to remember 1969 (which I was old enough to remember only sketchily) that the Mets were a dark part of their family heritage. When they saw a Mets fan on the train, they weren’t exactly welcoming, but they weren’t threatening, really — and they were definitely acknowledging. The Mets, 3½ behind the Cubs in the multidivison playoff race, were on their minds. I was the Mets’ surrogate for the moment.

I took the brief barrage of abuse with a smile. I wouldn’t have done that on a train to anywhere else. It was early Friday afternoon and I was a couple of stops from Wrigley Field where I was about to watch a couple of games. How could I not be smiling?

We pulled into the Addison station, and there it was once more, right where I left it in 1994, right where it had been since 1914. Wrigley Field…since I was last here three National League ballparks had risen and two had been swept away. The army of steamrollers Terrence Mann spoke of in Field of Dreams would just keep coming. The Vet would be replaced by Citizens Bank. Three Rivers would make way for PNC. Riverfront would disappear and Great American would materialize. Jack Murphy would bow out and Petco would be let in. The second Busch would become the third Busch. Shea would be dismantled before my eyes in favor of Citi Field.

Wrigley Field wasn’t going anywhere. But I was going inside.

***

Jeff told me he was securing us what he called the Rock Star Seats, the company box of boxes. He wasn’t kidding. These were seats worthy of Styx or REO or Chicago themselves. These were on a line with the Cubs on-deck circle, so close that the pine tar practically spattered off Mark Grace’s bat onto your lap. It was a few rows from the field, and at Wrigley, that meant you were close to everything. You were practically in play. It was the first time I truly feared for my well-being vis-à-vis foul balls.

Everybody wanted to be in the Rock Star Seats. An usher was charged with shooing away children who were hoping for a souvenir or an autograph or a nod from a Cub Star. The usher’s job was to be suspicious, unless you produced the Rock Star ticket, in which case he couldn’t have been more courteous. I got courtesy and a query about my HUNDLEY 9 shirt. The usher, so close to action, wasn’t really up on what was going on in baseball. I briefly explained what Todd had been doing since his pop Randy left the North Side in 1977.

Me and the usher, we got along fine.

Even Lee Elia would have been impressed by the crowd of over 40,000 this Friday. More than 15% of the world’s population was crammed into Wrigley Field, or so it felt. Small park, big interest, old logistics. If I wanted comfort, I would have stayed back at the hotel. It was a little cramped? Who cared? I was at Wrigley Field on Friday afternoon for a Mets-Cubs doubleheader in the midst of a battle for the National League Wild Card.

I ran down all those particulars in my head about six-dozen times in the course of the afternoon just so I could be sure I wasn’t dreaming any of them.

Jeff joined me in the first inning. Even he seemed impressed by how good the Rock Star Seats and what they showed us were. Friday afternoon doubleheaders weren’t exactly common, not even in Chicago. It was good for him to be out of the office. It was good for me to be next to him, the one Mets fan (politely) cheering the visitors in a sea of homestanding partisans. I’m a good guest. I didn’t boo any Cubs. Hell, this was the Summer of Sosa. I had brought my camera and clicked off any number of shots of Sammy loosening up his arm, Sammy ducking into the dugout, Sammy taking practice swings, Sammy — 2-for-8 on the day — not homering.

But I rooted for the Mets, and that’s where the dream really took wing (that’s a birding allusion in deference to Jeff’s other great passion, which he brings to life quite accessibly here — treat yourself and read it). Armando Reynoso was making his long-awaited first start of the year, and he picked up where he more or less left off in 1997, by being largely untouchable. Eight innings, five hits, no runs. The Mets pecked away at future Met Geremi Gonzalez and we (or should I say “I,” since I didn’t have much company in my affections among the Rock Star set) won going away, 5-0.

Butch Huskey had a couple of hits. I mention that because Butch Huskey was Jeff’s favorite Met of the era. His favorite Met name anyway.

Between games, I got up to find the men’s room and something to eat. Both were challenges, linewise. 1914 comes home to roost again. The sound system sucked. There was no replay. Even Rock Stars lacked amenities; Jeff noted a game earlier in the season at which one of the NBA champion Bulls had to queue up at the trough like everybody else.

And again…so what? It’s amazing how ivy and intimacy and a hand-cranked scoreboard and bricks not for effect but because they were an excellent building material and two games at a time of day when there are usually none trumps everything. Plus, the Mets won. Ralph Kiner always advised winning the first game of a doubleheader was crucial. You had one in your pocket.

Everything else would be gravy. But what gravy!

The Mets came out for the second game in different uniforms. This was the first year of the wearing of the black, and the Mets weren’t shy about sporting everything in their wardrobe. For a little while it appeared they might be changing their luck and not for the better. Todd Hundley displayed his unfamiliarity with left field when a Tyler Houston line drive eluded his glove (he should’ve worn a chest protector) but no harm was done. Still, the Mets trailed going to the eighth. But Mike Piazza drove in the tying run, Lenny Harris drove in the go-ahead run and, in the ninth, the Mets tacked on a few more.

It was a sweep! A Mets doubleheader sweep of the Cubs at Wrigley Field on a Friday afternoon that I took in from the kinds of seats reserved for the Eddie Vedders of the world. The Mets were the real rock stars, however. They were now 1½ in back of the Cubs for the Wild Card. There were still two months to go in the season, but this would be, thanks to expansion, realignment and general Seligism, the last series between the two old rivals. We had to get to the Cubs while the getting was good.

The getting was very good this Friday. Wrigley was very great. I didn’t want to leave. Savoring victory, I took out my Chinon 35mm camera (huge by 2010 standards) and took some more pictures. The memories, however, would suffice. I can still see Wrigley filling up; Wrigley jammed; Wrigley filing out; the green, green grass of Wrigley, so close to me…I didn’t want to pull back from it.

Who would?

Even though we took our time exiting, it was still a mob scene getting out. Absorbed at least one not so gentle ribbing about my Mets cap and shirt from someone who had obviously enjoyed a few Old Styles in the course of the long day. I might have answered a little chippily at that point, but I had two wins in my pocket. No need to ruin the sensation.

You know what’s outside Wrigley Field? Wrigleyville! It wasn’t planned that way, and I understand it’s pretty annoying for people who just want to live in the area (those who consume too much Old Style can pose a threat to local lawns), but what a boon to those of us who don’t want to let go of our experience. We don’t have to! Jeff guided us to a used bookstore he told me about. I had mentioned a few times in our stream of correspondence my twenty years of disappointment at losing my copy of Screwball, Tug McGraw’s 1974 autobiography and one of my all-time favorite books. It fell off the back of my bike in tenth grade after I had just used it for a book report (which I had also done in eighth grade and sixth grade), and never, prior to the invention of eBay, could track it down.

We browsed the book store, I had no luck with Screwball, though I was delighted to find Joy In Mudville by George Vecsey, the story of 1969 (I’m surprised it wasn’t repackaged for this neighborhood as Misery In Wrigleyville). It was a swell consolation prize and I was prepared to pay for it when Jeff, very matter of factly, pointed to a wall.

“There’s Screwball.”

And so it was. Two decades of searching ended two blocks from Wrigley Field, not too far from a brewpub called Weeghman Park and just up the street from a Chinese restaurant with the name Prince.

Could it get any better than this?

***

I’d fly home Saturday morning and listen to the Mets lose to the Cubs on the drive back from LaGuardia. The Mets would also lose Sunday. The margin was again 3½. We’d alternately sparkle and fade down the stretch in 1998. The Cubs gave us a fantastic opening one memorable September afternoon when their left fielder, Brant Brown, handled a fly ball like he was Todd Hundley and allowed three Brewer runs to score in the bottom of the ninth. Every Mets fan believed this was a sign of 1969 reincarnate, but the Mets themselves had no such illusions and went about losing their final five games of the year, leaving the Wild Card to be settled between the Cubs and Giants on a sudden-death Monday night at Wrigley. I tuned in, but I couldn’t bring myself to watch. That was supposed to be our Wild Card, dammit. Somewhere deep in my thinking, as the hurt of the ’98 proto-collapse eased, I would sate myself with my Friday from July. That was my playoff, and I won.

Twice, per Mr. Banks.

As for Wrigley at night…what’s the point? TV, I suppose, and maybe competitive realities, but c’mon. It puts me in mind of when cold-weather NFL teams parade their cheerleaders down the sidelines in warmup suits, as if the important thing is they lead cheers, not show off their…outfits. Covering up Wrigley’s sunny fashion with darkness demonstrates the same questionable taste.

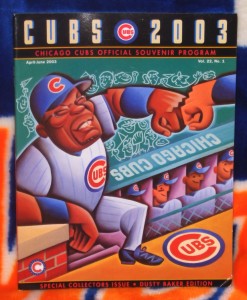

Jeff told me he actually preferred night games at Wrigley and was kind enough to take me one evening in 2003 when I was back in town on business. The seats were good if not Rockin’, and Wrigley was still nice, but not sunlit, and therefore not as special, not in my book. But Jeff saw some birds he liked and it was very much baseball, so it was by no means a total loss.

One more Wrigley opportunity presented itself that season — or postseason. I had a trade show in Chicago and called Jeff to get together for dinner when my day was done. This was the night off between Games Five and Six of the NLCS between the Cubs and Marlins. The series was coming back to the North Side, the Cubbies just one game from their first World Series since 1945. Jeff had tickets — bleachers — for tomorrow night.

Did I want to go?

It was a terribly tempting offer. I had been caught up in the Cubs’ march to glory of late. It was the first time they’d made the playoffs in a way that had nothing to do with the Mets, so I could be magnanimous in their direction. Most of decent baseball-loving America was dreaming of a Cubs-Red Sox Fall Classic, and Chicago was doing its part to hold up its end of the bargain. Everybody in town was talking about a Cubs’ pennant as a done deal. The newscasts were full of warnings about not overdoing the celebrating like was done for the Bulls — let’s not loot, OK? The PBS affiliate devoted a half-hour to mulling the bad old days and how they were about to be erased.

There might as well have been a MISSION ACCOMPLISHED banner strung up across Michigan Avenue.

Even I, old Cubs-hater, was talking about it in definite and approving terms. No way, I said to Jeff, can the Marlins come back, not with Prior going in Game Six and Wood, should it get that far, going in Game Seven.

Tantalizing as Jeff’s latest invite to take in a Cubs game was, I turned it down. I was in my third week of acute bronchitis, and it was all I could do to muster the strength to make my trade show. My flight home was the next day and I truly wanted to be on it, even if it meant passing up a chance to play eyewitness to baseball history. Besides, I told Jeff, you should find a real Cubs fan to accompany you. Somebody who’s been waiting his whole life for this moment should have that ticket.

***

Stephanie and I rooted my ancient nemeses on from home. It may have been the first time I sincerely hoped good things for the Cubs, but I was no luckier for them than any black cat or Brant Brown. Down 3-0, with one on and one out in the eighth, Marlins second baseman Luis Castillo popped a ball to the left side. Cubs left fielder Moises Alou seemed to have a bead on it, but it might be going into the crowd and…

Whoever had what could have been my ticket in the bleachers was an eyewitness to history, all right. Actually, he may not have been able to make out from that vantage point what happened, but he and Jeff and everybody else would learn soon enough the name Steve Bartman (poor kid) and what happens when you assume. Eight Marlins runs scored, the Cubs lost Game Six, the Cubs lost Game Seven and the Cubs are still waiting.

I haven’t been to Chicago since. Haven’t had much reason to pay a ton of attention to the Cubs except when they’ve come to Flushing or the Mets have gone to Wrigley. No rivalry anymore, except in my head. I’ve never let go of the Cubs as Metropolitan Enemy No. 1 on my most loathed list — I mean, sure, the Braves and the Philies and the Cardinals have all taken their turns, but it’s never stopped being 1969 in the depths of my being. I still resent them the way a six-year-old would for trying to keep my team from winning what I decided I wanted my team to win more than anything else. How dare they?

This feeling doesn’t dissipate easily. Or at all.

In the fall of 2006, on the eve of the Mets’ ascending to the National League playoffs, HBO was running a documentary chronicling all the dratted luck the Cubs had experienced in the past century. When they got to ’69, I forgot all about the Dodgers and the present. I was lost in love for my first Mets team, and took ungodly pleasure in how they destroyed the best Cubs’ team of its generation.

Eff you Durocher. Eff you Santo. Eff you 37-year-old footage of Bleacher Bums promising you’d have a little “surprise” for Cleon Jones when the Mets come in next week. I was so seriously revved up — especially by the lady TV reporter stationed at empty Wrigley Field on October 11, whining that the Cubs were supposed to be in Baltimore for Game One of the World Series, and instead she’s standing in the rain, and there’s nothing going on behind her and “it’s a lousy day in Chicago” — that when the documentary got around to Bartman, I couldn’t help myself. The ball again eludes Alou, Castillo is still batting and the Marlins are once more putting an eight-spot on that old-fashioned scoreboard.

“YES!” I suddenly let on to a genuinely surprised Stephanie, three years after the fact. “YES! I’M GLAD THEY LOST! I WANTED THEM TO LOSE!”

It was liberating to admit. It had nothing to do with 2003 or the Marlins and everything to do with 1969, 1984, 1989, 1998 and however many hundreds of Mets-Cubs games I’ve experienced in my unyielding memory. I just don’t like them, and I’m not good-natured about it.

Yet I’m absolutely, eternally in love with Wrigley Field. Even irrational hatred must have its limits.

by Greg Prince on 18 November 2010 10:14 am Melvin, Collins, Backman, Hale

One will succeed

When the other three fail

Melvin, Collins, Backman, Hale

A quartet contends

Yet just one can prevail

Melvin, Collins, Backman, Hale

The talks continue

As speculation grows stale

Melvin, Collins, Backman, Hale

From this crew a skipper

Once the others set sail

Melvin, Collins, Backman, Hale

A mushy middle manager

Or a true alpha male?

Melvin, Collins, Backman, Hale

Interviews by the bucket

Lest their answers prove pale

Melvin, Collins, Backman, Hale

May the winner drive straight

And avoid the third rail

by Greg Prince on 17 November 2010 7:34 am  Saluting No. 41 on the Empire level (couldn't find his statue). It’s amazing how the memory of Seaver’s greatness has faded in New York over the last 20 years. Pitchers whose accomplishments are anywhere near Seaver’s might have been expected to have gained in reputation from having pitched 12 seasons under the scrutiny of New York baseball writers. Seaver’s seems to have suffered.

—Allen Barra, The Village Voice, 5/19/2010

Tom Seaver is 66 today.

Tom Seaver was 41 for the first time on 4/13/1967.

Tom Seaver was 0 0 0 1 1 vs. Conigliaro, Yastrzemski, Freehan and Berry on 7/11/1967.

Tom Seaver was 2 0 0 0 5 vs. Carew, Yastrzemski, Oliva, Azcue, Powell, Mantle, Wert and Monday on 7/9/1968.

Tom Seaver was 0 0 0 0 11 for the first 8.1 vs. Kessinger, Beckert, Williams, Santo, Banks, Spangler, Hundley, Qualls, Holtzman and Abernathy on 7/9/1969.

Tom Seaver was 6 1 1 2 6 for 10 vs. Buford, Blair, F. Robinson, Powell, B. Robinson, Hendricks, Johnson, Belanger, Cuellar, May and Dalrymple on 10/15/1969.

Tom Seaver was 25-7 after 162 in 1969 and 2-1 after 8 more that October.

Tom Seaver was 19 on 4/22/1970, the final 10 of them in a row.

Tom Seaver was 20-10, 1.76 and 2.89 for all of 1971.

Tom Seaver was 0 0 0 4 11 for the first 8.2 of 7/4/1972.

Tom Seaver was 1 in ERA, CG, SO, ERA+, WHIP, H/9, SO/9 and SO/BB in 1973.

Tom Seaver was 200 for the 7th consecutive year on 10/1/1974.

Tom Seaver was 200 for the 8th consecutive year on 9/1/1975.

Tom Seaver was 0 0 0 3 8 for the first 8.2 of 9/24/1975.

Tom Seaver was 16 H, 3 R, 3 ER, 6 BB and 29 K in 27 IP on 7/17/1976, 7/23/1976 and 7/28/1976 yet came away from those 3 starts 0-2 with 1 ND.

Tom Seaver was 9+ on 18 regular-season occasions from 1967 to 1976.

Tom Seaver was 200 for the 9th consecutive year on 9/3/1976.

Tom Seaver was 41 for what seemed like the last time on 6/12/1977.

There isn’t a person in the world who hasn’t heard about Tom Seaver. He’s so good, blind people come out to hear him pitch.

—Reggie Jackson, Oakland A’s, 1973 World Series

Tom Seaver was 0 0 0 3 3 after 9 on 6/16/1978.

Tom Seaver was 3,000 on 4/18/1981.

Tom Seaver was 7-1 in the first half-season of strike-sundered 1981.

Tom Seaver was 7-1 in the second half-season of strike-sundered 1981.

Tom Seaver was 41 again on 4/5/1983.

Tom Seaver was 1 in 3B, with 2, after the games of 4/20/1983.

Tom Seaver was 41 for what, in retrospect, seemed like the last time on 10/1/1983.

Tom Seaver was 0 0 0 0 0 in the top of the 25th when the game of 5/8/1984 resumed on 5/9/1984.

Tom Seaver was 3 4 4 1 0 in 8.1 in the regularly scheduled game of 5/9/1984.

Tom Seaver was 2-0 on 5/9/1984.

Tom Seaver was 300 on 8/4/1985.

There is actually a good argument that Tom Seaver should be regarded as the greatest pitcher of all time.

—Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, 2001

Tom Seaver was 198-124 for us, 113-81 for others.

Tom Seaver was 106 over .500 from 1967 through 1986.

Tom Seaver was 2.86 after 4,783.

Tom Seaver was 2.62 for every 1 after 20 seasons.

Tom Seaver was 41 on 7/24/1988.

Tom Seaver was 98.8% on 1/7/1992.

Tom Seaver is 66 today.

Tom Seaver is 41 always.

by Greg Prince on 15 November 2010 5:41 am Bob Melvin. Terry Collins.

Terry Collins. Bob Melvin.

Really? That’s the best Team Genius can do for serious managerial candidates?

Seriously?

Yeesh.

Caveat: I haven’t interviewed Bob Melvin or Terry Collins. I haven’t worked with them. I haven’t spoken to their peers. I haven’t played baseball for either of them. Thus, I could be missing whatever it is that has catapulted them to the reported top of the list among candidates considered for the post of manager of the New York Mets.

That said, this is who it comes down to? Two retreads whose winning was limited in their previous engagements and whose reputations did not seem to make them particularly hot commodities within the industry during their time at liberty?

This is it?

Like many curious Mets fans, I suspect, I’ve found myself rereading Moneyball to discern the Alderson philosophies and have stared relentlessly at the most oft-cited passage regarding our new GM’s theories on what he wants — and doesn’t want — out of a manager.

“In what other business,” he asked, “do you leave the fate of the organization to a middle manager?”

The context for the remark was a discussion of Moneyball’s signature aspect, the value of on-base percentage, and how it was no simple task to implement it as the guiding principle from bottom to top within the Oakland A’s system since longtime (and undeniably successful) manager Tony La Russa had his own ideas about what he wanted his players doing. Downgrading a Hall of Fame manager to the status of midlevel apparatchik was Alderson’s way of saying the A’s weren’t necessarily La Russa’s players. They belonged to the A’s, and there was an A’s way of doing things that was to take precedence over any manager’s theories.

That was the idea, according to Moneyball, but La Russa stopped figuring in the equation once his contract was up and he split for St. Louis. The vacancy gave Oakland Art Howe, likely every Mets fan’s idea of a middle manager after he chalked up two ineffectual seasons in the Mets dugout.

Howe led (or middle-managed) Oakland to three consecutive playoff berths, so one can infer that the system worked better out west, or that the A’s had better players from 2000 to 2002 than the Mets did in 2003 and 2004. Not every situation syncs to every person, and Alderson indicated amid the press gaggle that followed his formal introduction at Citi Field on October 29 (as transcribed by ESPN New York’s Adam Rubin) that his entire thought process on managerial selection had not been fully reflected in Lewis’s nearly eight-year-old work.

I know there’s been some discussion about the three paragraphs in Moneyball that relate to me. I do believe, just putting it in a broader context, that a manager needs to reflect the general philosophy of the organization. That’s important not just for a manager. That’s important for a player-development system. It’s important for every element of a baseball operation to have some sense of consistency of approach, of philosophy.

At the same time, the manager is a very critical part of the overall leadership structure. His job is very different from mine, it’s very different from the director of scouting, etc. There are certain qualities that he has to bring. I have in my years worked with managers ranging from a Tony La Russa to a Billy Martin. So I can appreciate a fiery manager. And I think a fiery manager is actually quite desirable. I think that in some cases a manager is not only representing an organization, but the fans in maybe frustrating situations and acts as a proxy for all of us.

I also think it’s important for a manager to be somewhat analytical, but at the same time occasionally and sometimes often intuitive. We’re looking for somebody that is right for our situation. What is our situation? You start with the fact that it’s New York City.

We’re looking for somebody that fits intellectual requirements, but also intuitive and emotional ones. That manager may have experience, may not have experience at the major league level. We’re very open-minded about it at this point. But I do want to emphasize that whoever is selected is going to be the manager and making those decisions and needs to have a certain level of independence in order to accomplish what he needs to accomplish.

This was a little more than two weeks ago. Multiple candidates have been interviewed and what we’ve wound up with are Bob Melvin and Terry Collins.

Are either or both of them any or all of the following?

• Fiery

• A proxy for all of us

• Analytical

• Occasionally to often intuitive

• Suited for New York

• Meeting intellectual requirements

• Meeting emotional requirements

• Likely to maintain a certain level of independence

Last week he appeared on SNY’s Mets Hot Stove after the managerial interviewing was well underway (but before the consensus that Melvin and Collins as the favorites had publicly leaked), and this was his rather broad description of what he is seeking in a manager.

From a general standpoint, I think that what you’re looking at [are] the two basic aspects of leadership, which is professional competence and personal qualities, and [,,,] how they fit together into sort of a total package.

If you’re not professionally competent, it ain’t gonna work.

But also personal qualities are very important, and some kind of blend into the professional side. Things like communication and a sense of empathy, the ability to articulate a philosophy or an approach.

So there are these two basic areas — personal qualities and professional ability — that I think we try to plumb to see what’s there.

We’ve had pretty direct conversations with our candidates about their recent experiences and specific things related to their coaching or managing history, so we’ve learned quite a bit.

If we are to take the consensus of reporting as reliable and assume that is really is down to Collins and Melvin, do these sound like words that could be applied to either of these men?

• Leadership

• Professional competence

• Personal qualities

• Communication

• A sense of empathy

• The ability to articulate a philosophy or an approach

It’s all bland enough that it could apply to anybody in any job, and, given that it was his position after the first round of interviews, it (more so than what he outlined on the day he met the media en masse) likely serves as a barometer of what Alderson wants out of a manager:

The bare minimum.

That’s what it feels like. That’s what the search for the next manager of the National League franchise in the nation’s largest market has built toward — someone who won’t get in the way. In other words, a middle manager.

Maybe it’s the way to go. Maybe the Alderson-DePodesta-Ricciardi genius transcends personality in the clubhouse and dugout. Maybe it’s enough to transmit the idea that batters should take pitches and pitchers should throw strikes and not give up runs. Maybe consistency of approach is what the Mets have been missing these past several seasons when various actors definitely seem to have been ad-libbing their parts to the detriment of the entire cast, crew and production.

Maybe. But I can’t get past the idea that a manager does have an influence on the outcomes of seasons, and not just lousy managers managing teams into the ground by stubbornness, inscrutability or whistling past the graveyard.

If we are to accept the idea that running a baseball club is a “business,” per the quote from Moneyball, I’d ask in what businesses do middle managers march solely in lockstep with upper management’s directives?

Dreary businesses, I’d say. Dreary businesses where the middle managers and the rank-and-file employees dread coming to work because the life has been sucked out of them. Dreary businesses where there’s little creative tension and, probably, little creativity.

It’s not a perfect metaphor. It may not even be an apt one, because as logical as applying business principles to baseball may be for much of what needs to be done to build a solid foundation, baseball’s a game. It’s a game of people more than principles. It’s also a game whose greatest moments are its most unlikely ones. You can endeavor to minimize risk and plan to maximize results, but sooner or later you’re going to need somebody to come up with an idea…somebody in the middle of things…somebody who knows his people.

In trying to reckon what it might be about Bob Melvin and Terry Collins that have brought them to the forefront of the Mets’ managerial search, I’ve been thinking about the managers who’ve succeeded at the highest pinnacle a manager can succeed — those who’ve won a World Series. In the past decade, nine different managers have stood at the end of the postseason cradling the Commissioner’s Trophy. They’ve been a diverse group:

• Bob Brenly

• Mike Scioscia

• Jack McKeon

• Terry Francona (twice)

• Ozzie Guillen

• Tony La Russa

• Charlie Manuel

• Joe Girardi

• Bruce Bochy

Beyond the prize they’ve attained, I’m at a loss to determine a common denominator among them, but I never got the sense that any of them was a cipher. They lent their teams a sense of urgency. They never panicked. They were preternaturally serene. They fired up their troops. They were tough. They were reasonable. They laid down the law. They were players managers. They were just what was needed for this team, and now the whole world knows it.

Maybe we’ll be saying something similar someday for Collins or Melvin. Someday, perhaps, we’ll be writing that we didn’t know the inner fire that burned inside Bob Melvin, the desire to win that overtook him and spread quietly but effectively to his troops. Someday, it could be, we’ll be telling one another that Terry Collins took the hard road to this moment, that he ironed out the kinks that tripped him up at previous stops and learned a lot along the way and now it is we who reap the benefits. We might very well be saying that after Jerry Manuel, Terry Colins/Bob Melvin was exactly the antidote for the Mets’ malaise…and now the whole world knows it.

But I’ll bet, should we feel compelled to praise one of them to the high heavens because he has accomplished the most any major league manager can hope to accomplish, that we won’t be saying, “That guy was good the way he shut up and quietly went along with whatever the front office decided.”

There’s got to be more than that to managing, whether it’s managing innings or egos. There has to be a reason Bobby Cox had so many in the sport — Braves players past and present in particular — tipping their caps to him on his way out beyond how well he absorbed memos from John Schuerholz. “I’ll be loyal to Bobby Cox as long as I live,” a bit player from his earliest team said in 2010, and he wasn’t alone in expressing such enduring devotion. No mere functionary inspires those kinds of feelings.

There had to be a reason, too, that Sparky Anderson was eulogized so warmly upon his recent passing besides a predilection for next-generation Stengelese. Joe Posnanski, not surprisingly, wrote a beautiful remembrance of Anderson, featuring these thoughts from one of Sparky’s most celebrated players:

“I don’t know why we did the things we did for Sparky,” Pete Rose said. “But we all did. All of us. Johnny. Joe. Me. All of us.” In 1975, middle of the year, Sparky Anderson asked Pete Rose to move from the outfield to third base, a position he had not played in 10 years (and had hated when he did play there briefly). And Pete Rose moved. “We wanted to win for Sparky,” Rose said. “He just had this way about him.”

“We wanted to win for Sparky.” I don’t know whether that’s a sentiment Rose expressed upon hearing that his old manager died or was recorded when Posnanski was writing his book about the Big Red Machine. Either way, it’s telling, even if it describes a scenario from 35 years ago, from the tail end of the age when players had no choice about the manager for whom they played.

We wanted to win for Sparky. Not play for Sparky. But win for Sparky. Rose and Bench and Morgan and Tony Perez (who, on another occasion, used the exact same phrase) and the rest of the Machine probably wanted to win for themselves as well, but every possible motivation in the name of a championship is welcome.

(And, for what it’s worth, shifting Rose, a perennial All-Star left fielder to third base with the season a month old to create a spot for emerging slugger George Foster, was pretty gosh darn creative.)

Can you imagine any 2011 or 2012 New York Met declaring he wants to win for Bob Melvin? For Terry Collins? Can you imagine any 2011 or 2012 New York Met pledging lifelong allegiance to Terry Collins? To Bob Melvin?

Is this a little much to ask? Aside from the modern ballplayer being primarily loyal to himself, we are comparing two almost random former big league managers to two legends of the game, one who is ensconced in Cooperstown, one who will be at the first opportunity.

But is practical randomness the best the Mets can do for a manager? Are we to believe that it didn’t matter who succeeded Wes Westrum as fulltime Met manager in 1968, that Gil Hodges didn’t have a profound impact on the fortunes of this franchise? That Davey Johnson was not essential to the unprecedented long-term success that coincided with his appointment prior to the 1984 season and all but expired with his dismissal in 1990? That when the Mets snapped a veritable six-year losing streak in 1997 and contended every year through 2001 that anybody could have been filling out lineup cards and that Bobby Valentine’s handwriting and fingerprints were just incidental?

I just don’t buy that.

I have no hunch if the next manager will be Bob Melvin or Terry Collins or a late-breaking dark horse, but I’d sure like him to be ideal. I’d like him to be a difference-maker. I’d like him to turn this club around, to get it to play intelligently and passionately. I’d like him to outthink his opposite number. I’d like him to be managing in the sixth while Fredi Gonzalez and Charlie Manuel are still fumbling around with the fourth. I’d like him to take no guff from umpires when they make their usual spate of bad calls. I’d like to hang anxiously on his every pregame and postgame word. I’d like him to bunt only when it makes sense, to give the take sign because he’s picked up something the other team’s pitcher is doing, to shuffle lineups and personalities expertly. I’d like him to keep Pedro Feliciano’s left arm from falling off if Pedro Feliciano’s arm is still here.

I want frigging miracles, I suppose, yet I’m not going to get those. I don’t know what’s in store, but managerial miracles don’t appear in the forecast. Maybe I don’t know enough about Collins or Melvin as individuals, but I’m trying to imagine a moment when the Mets rally behind one of them and drive to glory. I’m trying to see one of these hired hands having his head doused by bubbly after he hands the Commissioner’s Trophy back to Alderson, and Alderson hands it to a Wilpon.

Bob Melvin. Terry Collins.

Terry Collins. Bob Melvin.

The picture comes up blank.

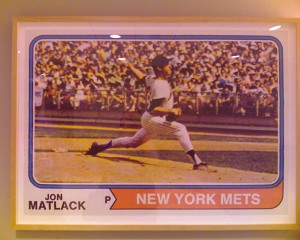

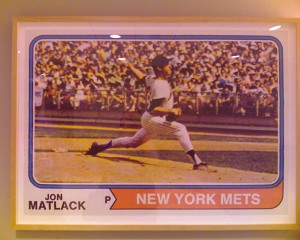

by Greg Prince on 12 November 2010 8:03 pm  A pretty darn good pitcher? Yes! Horizontal cards are weird because approximately 98.8% of their peers are vertical, but they can be beauties, too. In honor of the release of this year’s The Holy Books collection, I present, as captured on the cordoned-off walls of the Empire level at Citi Field last August, what I believe is my partner’s favorite card of all time, the 1974 Jon Matlack. I asked him once and I think this was the answer…and if it wasn’t, there are worse things to look at in the middle of November.

Jon Matlack was a great pitcher, not incidentally. I’m so Jonned up over him, in fact, I think I’ll reprint what I wrote about when I declared him the No. 39 Greatest Met of the First Forty Years:

Mystery guest, please sign in.

OK, let’s get started.

Is your middle name Trumpbour?

Yes.

Were you the second Met to win Rookie of the Year?

Yes.

Were you named to the National League All-Star team thrice?

Yes.

Did you get the win in one of those games?

Yes.

In your first five full seasons, did your record 75 victories?

Yes.

Was that the most any Met not named Seaver or Gooden ever totaled in his first five seasons?

Yes.

Was your ERA for those five years a mere 2.84?

Yes.

With the Mets trying to win a division in a five-team scramble on what was supposed to be the final day of the regular season, did you strike out nine Cubs in eight innings?

Yes.

Did you wind up losing that game 1-0 on a run scratched out in the eighth?

Yes.

Was this kind of run-support typical of what you received while you were a Met?

Yes.

Was the only game you pitched in a playoff series a two-hit shutout against one of the greatest-hitting teams of all time?

Yes.

Were those two hits collected by Andy Kosco?

Yes.

Not Pete Rose, Joe Morgan, Tony Perez or Johnny Bench, but Andy Kosco?

Yes.

Did you start three games in the ensuing World Series against another historically great team?

Yes.

Did you yield no earned runs in 14 innings over those first two starts?

Yes.

Did you pitch two more shutout innings in Game Seven before running out of gas in the third?

Yes.

Would have you avoided that situation had Yogi Berra pitched George Stone in Game Six, thereby saving Seaver for Game Seven?

Yes.

But you took the ball?

Yes.

And did you come that far in 1973 despite Marty Perez of the Braves whacking a liner off your head and fracturing your skull?

Yes.

Yet were you back pitching eleven days later?

Yes.

On June 29, 1974, did you pitch a one-hitter against the Cardinals at Shea Stadium?

Yes.

Was it the first win ever witnessed in person by at least one eleven-year-old Mets fan?

Yes.

Shouldn’t you be mentioned more often as one of the best pitchers the Mets ever had?

You tell me.

by Jason Fry on 11 November 2010 5:28 pm Yoo-hoo? Anybody miss me?

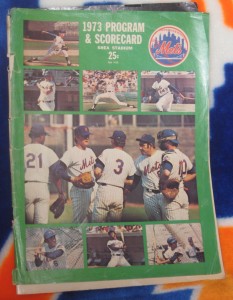

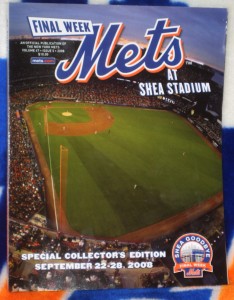

After a month of insanity (finishing a Star Wars book, grueling new freelance gig), I can finally think once again about my beloved New York Mets. (Nod to the beyond-awesome Citi ad set in Istanbul.) So let me sally forth by looking back — and giving a slightly overdue welcome to the THB Class of 2010. (Previous annals here, here, here, here and here.)

Here’s a recap for newcomers: I have a pair of binders, dubbed The Holy Books (THB) by Greg, that contain a baseball card for every Met on the all-time roster. (News flash: Binder #2 is now full. The Alderson Era will be a fresh start in more ways than you thought.) The binders are ordered by year, with a card for each player who made his Met debut that year: Tom Seaver is Class of ’67, Mike Piazza is Class of ’98, Jose Reyes is Class of ’03, etc. There are extra pages for the rosters of the two World Series winners, including managers, and one for the 1961 Expansion Draft. That includes the infamous Lee Walls, the only THB resident who neither played for nor managed the Mets.

Welcome, new boys! If a player gets a Topps card as a Met, I use that unless it’s truly horrible — Topps was here a decade before there were Mets, so they get to be the card of record. No Met Topps card? Then I look for a Bisons card, a non-Topps Met card, a Topps non-Met card, or anything else. Topps had a baseball-card monopoly until 1981, and minor-league cards only really began in the mid-1970s, so cup-of-coffee guys from before ’75 or so are a problem. Companies like TCMA and Renata Galasso made odd sets with players from the 1960s — the likes of Jim Bethke, Bob Moorhead and Dave Eilers are immortalized through their efforts. And a card dealer named Larry Fritsch put out sets of “One Year Winners” spotlighting blink-and-you-missed-them guys such as Ted Schreiber and Joe Moock. (A new wrinkle: Topps has recently been selling off its stock of old photos, including ones of guys who never got proper cards. I was outbid for the Ted Schreiber, to my moderate but slowly escalating annoyance.)

Then there are the legendary Lost Nine — guys who never got a regulation-sized, acceptable card from anybody. Brian Ostrosser got a 1975 minor-league card that looks like a bad Xerox. Leon Brown has a terrible 1975 minor-league card and an oversized Omaha Royals card put out as a promotional set by the police department. Tommy Moore got a 1990 Senior League card as a 42-year-old with the Bradenton Explorers. Then there are Al Schmelz, Francisco Estrada, Lute Barnes, Bob Rauch, Greg Harts and Rich Puig, who have no cards whatsoever — the oddball 1991 Nobody Beats the Wiz set is too undersized to work. Best I can tell, Al Schmelz never even had a decent color photograph taken while wearing his Met uniform. (Here’s a crappy black-and-white photo I felt compelled to buy.) The Lost Nine are represented in THB by DIY cards I Photoshopped and had printed on cardstock, because I am insane.

During the season I scrutinize new card sets in hopes of finding a) better cards of established Mets; b) cards to stockpile for prospects who might make the Show; and most importantly c) a card for each new big-league Met. At season’s end, the new guys get added to the binders, to be studied now and then until February. When it’s time to pull old Topps cards of the spring-training invitees and start the cycle again.

Anyway, here they are, the final class of the already unbeloved Minaya regime:

Manny Acosta: Lanky reliever threw hard, but had problems hitting the plate and with dinger-related neck strain. This description suffices for approximately 73,541 relievers in baseball history. If not for having surrendered a couple of huge hits in big spots, I’d probably think of him more fondly. But he did and so I don’t. Manny gets a mock Topps ’52 card from a few years ago, on which he’s depicted as a Brave.

Joaquin Arias: Stats-minded Mets fans appreciated Arias for not being Jeff Francoeur, but I thought the Mets deserved praise for a different reason: It looked as if the Rangers organization had denied Arias food in Oklahoma City, which is mean. Seriously, the guy made post-Marines Buddy Harrelson look like an offensive lineman. Has since been waived, and possibly is being hand-fed gruel by Sally Struthers as you read this. Topps ’52 card as a Ranger.

Rod Barajas: Seemed like a fine acquisition when he was slugging clutch home runs, not so much when it became obvious that nobody had told him that Ball 4 = First Base. Still, a decent sort who was an interesting interview and kept the catcher’s seat warm for Josh Thole, whom the Mets didn’t hold back because someone with Veteran Leadership TM was on the roster. So no particular harm, no particular foul. Barajas got a Topps Update card as a Met, despite spending the last six weeks of the season employed by the Los Angeles Dodgers. While we’re on the subject, Alex Cora got a Mets Topps Update card despite being released two weeks before Barajas left town. I’m sure it’s completely unrelated that 2010 was the first year in three decades in which Topps was given a monopoly on major-league baseball cards. Competition, kids! It makes products better!

Jason Bay: Sitting in the stands at Citi, I noticed Jason Bay’s at-bat music — an odd, off-kilter riff leading into a metalesque singer who sounded a bit like David Lee Roth. To my surprise, the song was by Pearl Jam, which has always been a band I admire rather than like. Anyway, “The Fixer” became a favorite of mine, and I rehearsed a blog post in which I’d talk about the song and weave in its lyrics — which are about redemption and taking a problem on your shoulders and making things better — with an account of a big Jason Bay hit. All I needed was the big Jason Bay hit. Topps Update card.

Henry Blanco: Tattooed, imposing catcher did about all you could ask from a back-up catcher. Really good back-up catchers are like pleasant laundry rooms — they’re a nice thing to find in a house, but nobody’s ever stalked away from a showing because the laundry room was lacking. I’d call Henry Blanco a stacked washer-dryer with a sufficient supply of off-brand dryer sheets and maybe a plastic laundry basket that’s a no-longer-fashionable color but still serviceable. Blanco got a Topps Update card, which must make back-up catchers in Pittsburgh or Houston mad.

Chris Carter: The Animal was amusingly intense, got some big hits, and was also a welcome antidote to the assumption that baseball players’ mental activity away from the stadium pretty much consists of thinking about hitting baseballs. Carter went to Stanford, where he got a degree in human biology — in three years. He’s interested in things such as the dedifferentation of blood cells, stem-cell research and cloning. What does Carter get for this doubly impressive resume? A lousy Buffalo Bisons card — and it’s a dreaded horizontal to boot.

Frank Catalanotto: Catalanotto was given the heave-ho after showing very little as a pinch-hitter early in the year, which wasn’t particularly fair but is how things work: Pinch-hitters, like middle relievers, wind up unemployed if one of their bad stretches happens to come at the start of their tenure. Topps showed they were paying at least fitful attention by not giving him a Mets card seven months later, leaving THB to content itself with last year’s update card, on which he is a Brewer.

Ike Davis: Oh, Ike. Tall, outwardly amiable, and looked like an overgrown Nadia Comaneci with a dugout railing at hand. Ike swiftly displaced Mike Jacobs — part of the ample evidence in the case of Fans v. Omar Minaya — in the lineup and gained a spot in our hearts. He hit tape-measure home runs, he had some idea of the strike zone, and he was wonderfully sure-handed at first base. (He should’ve won a Gold Glove except for the award being a stupid popularity contest.) Best of all, he suffered through a rough early summer and then had a pretty fine September, which bodes well for future years. Topps snuck in a short-printed Series 2 of Ike after he’d been crowned with a shaving-cream pie, which I refused to buy because a) it was expensive and b) that kind of card is a Yankee thing. His Topps Update card will do just fine.

R.A. Dickey: Exhibit A in the half-hearted case made by the defense in Fans v. Omar Minaya. Dickey was one of the finest stories to come around these parts in years: a fireballer who got jobbed out of most of his signing bonus for the sin of being born without an ulnar collateral ligament, had to reinvent himself as a knuckleballer and somehow made it work. The Mets had never had a knuckleballer of any merit, but Dickey proved he was no novelty act: He was a student of pitching, a terrific fielder and a pretty fair hitter to boot. Plus he spoke like a character from a W.P. Kinsella story. Baseball players like this typically only exist in novels and overheated blog posts, but every time we pinched ourselves, Dickey was still there. His lone card is a Buffalo horizontal, a Topps oversight that upset me to an unhealthy degree.

Lucas Duda: With his huge frame, vaguely smash-faced visage and lumbering strides in left field, Duda looked like an 1990s Milwaukee Brewer or the understudy for Lennie in “Of Mice and Men.” And during September his brand-new career took a decidedly tragic turn — he collected his first hit in Chicago and then went so cold that you wondered if he’d ever get another one. He was 1 for 34, and you wanted to time your bathroom trips for his at-bats, not because you were mad at him but because his struggles were so pitiful that it felt cruel to watch. But Duda then broke out of it with a monstrous home run and went on an honest-to-goodness tear, hitting tracers out of Citi Field. Far too much baseball writing attributes getting a hit to character (or not getting one to a lack of it), but being 1 for 34 in the big leagues and staying even-keeled really does seems indicative of some measure of it. I don’t know if we’ll ever hear from Lucas Duda again, but I’ll remember the story of his September for some time. He gets a horrible 2008 Bowman Chrome card for now; here’s hoping for an upgrade down the line.

Jesus Feliciano: Feliciano toiled in the minor leagues for 13 seasons before finally getting his chance at the age of 31. That’s a lot of time staring at the ceiling of cheap motels and riding around on crappy buses in pursuit of a dream that must have come to seem like it wasn’t going to come true. It’s great that it did. All that makes me feel shrivel-hearted and small-souled for now pointing out that Jesus Feliciano wasn’t really very good. Topps Update card.

Dillon Gee: If you circled Dillon Gee’s big-league debut in Washington in red pen, you probably have the same last name as him. (And this is coming from a guy who drove from D.C. to Philly to see the Mets take the wraps off Bobby Jones.) But Gee took a no-hitter into the sixth in his debut and didn’t even get accused of not caring about injured veterans later. He pitched pretty well, all told, for the rest of the year — certainly well enough to merit a 2011 look. Gee is one of those guys who has to have very good location and command all his pitches to succeed, and guys like that generally sit at the back end of rotations and get hit. But sometimes they don’t: It’s overly optimistic assuming every change speeds/hit spots guy can be Greg Maddux or even Rick Reed, but it’s overly pessimistic to dismiss the idea that a guy like that has no chance. Got a 2010 Bowman card.

Luis Hernandez: Hit a home run with a broken toe, which is pretty impressive. Beyond that, I have trouble remembering much of anything he did beyond Not Being Luis Castillo. We can do better than that from now on, right Mr. Alderson? Depressing Factoid: Luis’s homer was the only one hit by a Mets second baseman in 2010. Yipes. His card is a Topps ’52 style Oriole. There were a bunch of those this year for some reason.

Mike Hessman: Late in 2010 I was trying to explain the concept of “Quadruple-A player” to my son. Once I used Hessman as an example he got it instantly. Represented by a Topps Pro Debut card.

Ryota Igarashi: Nicknamed Rocket Boy. Rockets that miss with the depressing frequency shown by Igarashi are generally destroyed remotely from the control room. Got a two-year deal, while Hisanori Takahashi got a chance to walk after one campaign. Good job, Omar! Represented by a 2008 Baseball Magazine Japanese card on which he is a Yakult Swallow.

Jenrry Mejia: There was Gary Matthews Jr. in center, Mike Jacobs at first, the stubborn insistence that John Maine and Oliver Perez would be just fine, and the continuing presence of Luis Castillo. But what really got the torch-bearing mob advancing on Castle Omar was sacrificing a year of the fireballing Mejia’s development while wasting him as a middle reliever. I’m annoyed all over again just thinking about it. Here’s hoping young Jenrry has a career good enough that I eventually think of him without automatically also thinking of Met front-office stupidity. Got a Topps Series 2 card that I’d be happier never to have seen, given why it existed.

Mike Nickeas: Minor-league journeyman makes average. His father sort of played for Liverpool. Got a 2005 Bowman Draft Picks card in which he was a Ranger. Curious amount of Mets-Rangers traffic this season.

Hisanori Takahashi: Wily, brave Japanese veteran who pitched capably as a middle reliever, starter and emergency closer. Headed elsewhere in 2011 after seeking what I’ll admit seemed like a lot of years to commit to a pretty old pitcher. We’ll miss him whenever Igarashi gives up a double in the gap or K-Rod punches a relative. Didn’t get a Topps Update card, but did get a Topps Chrome card. Damn it, Topps.

Ruben Tejada: Slick-fielding second baseman clearly wasn’t ready with the bat, but survived a grueling season and the existence of Jerry Manuel to put up encouraging numbers in September. His soft hands and precocious baseball instincts were a joy to watch, but one has to be realistic about that bat. Got a Topps Series 2 card.

Justin Turner: Showed flashes in a brief midsummer callup, but didn’t return in September. Given the collective wattage of the Mets braintrust in 2010, it’s possible they forgot he existed. (Reading this, Nick Evans squeezes the mouse too hard and breaks it.) Can we take another moment to sing hallelujahs that people with functioning cerebellums now run our club? Has a card as a 2009 Tide, which continues to startle me even though I know perfectly well the Tides were an Orioles farm team by then.

Raul Valdes: The definition of warm body. Has a 2006 Bowman card on which he’s a Cub and his name is spelled “Valdez.” This undoubtedly strikes him as more of an injustice than it does me.

by Greg Prince on 10 November 2010 12:27 am  Band on the run...or at the end of it. Sharon's right wrist and the rest of her savors the NYC Marathon finish line. Six hours, twelve minutes, twenty seconds. Six-thousand two-hundred forty-one dollars. Obviously you recognize those figures as how long it takes the Yankees and Red Sox to play seven innings and how much it costs to see them do so at Yankee Stadium. But there’s more to those numbers.

The first figure is how long it took Sharon Chapman — and her Faith and Fear in Flushing wristband — to traverse the 26.2 miles that coursed through all five boroughs Sunday, meaning she was good to her goal and finished the New York City Marathon. Good Metsopotamian that she is, her self-imposed time limit was six hours and fifty-three minutes, or the length of the inartful yet memorable twenty-inning staring contest that ensued between the Mets and the Cardinals last April. Sharon beat it by better than forty minutes, and no position players were compelled to pitch in the process.

It should be noted 6:12:20 was her running time, but the time spent on preparation was exponentially longer — not just intense training for the Marathon, but the heartfelt fundraising Sharon led in conjunction with her entry into the race. That’s where the $6,241 comes in — it’s the final total that has made its way to the Tug McGraw Foundation. It’s $6,241 committed to improving the quality of life for victims of brain tumors and for seeking out treatments and cures for brain cancer, post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury. What blows me away beyond the 26.2 miles run in 6:12:20 is the $6,241 raised inside of 11 months. The sum and the effort it took to build it represents dedication and generosity and hope…and it’s fantastic.

Thanks once more to all of our readers who contributed to Sharon’s cause. Thanks to Sharon for making the Tug McGraw Foundation her cause and for engaging this humble blog to serve as her run’s decidedly uncorporate sponsor.

by Greg Prince on 9 November 2010 5:00 am I want to go to a 2011 Mets game. I can’t wait. I never can. Theoretically, I want to go to them all, but that’s a prohibitive desire, despite all the swell enticements the Mets are offering. Right now, with the days suddenly disgustingly shorter and the air disagreeably colder, I think I need just one 2011 Mets game so see me through the long night of winter.

The Mets are so busy trying to sell season tickets that they’re not officially doing anything yet with single-game sales, still I was hoping I could apply for early admission. Hence, I headed to Citi Field — the advance ticket windows. Go there and you don’t have to pay convenience fees. It’s much more convenient to avoid those, I find. Not surprisingly, there were no lines yet. Lots of windows, my choice.

But which one could sell me tickets? Would it make a difference

“Hello,” I said at the first window. “I know it’s only November, but can you sell tickets to Mets fans?”

“I don’t know if I can,” the vaguely recognizable face replied. “I’m Don Wakamatsu. I used to be manager of the Seattle Mariners.”

“Were you any good at it?” I asked.

“For a while there, I suppose,” he told me. “We had an 85-77 record my first year, 2009. Big improvement over 2008.”

“So what’re you doing here?”

“It didn’t work out in 2010 so good. We were 42-70 and I got canned.”

“And you think you’re gonna sell tickets to Mets fans?” I asked incredulously. “No thanks.”

Next window revealed a face that elicited a glimmer of recognition.

“Hi,” I said, a little more brusquely. “Can you sell tickets to Mets fans?”

“I can do any number of things in baseball,” this face said.

“You can?”

“You bet. I’m Bob Melvin. I was Manager of the Year!”

“You seem pretty proud of that.”

“You bet I am. I won 93 games in Seattle in 2003.”

“That was your Manager of the Year year?”

“No, I didn’t get an award for that. I took over a pretty good club after Lou Piniella left.”

“But going to the playoffs was its own award, I’ll bet.”

“Um, we didn’t go to the playoffs that year. Oakland was pretty good.”

“Then which year did you take the Mariners to the playoffs?”

“I didn’t. I only lasted another season. We lost 99 games and I was gone.”

“So the award…?”

“Oh, that was in Arizona. We had a swell team. Won 90 games in 2007!”

“Not bad,” I said, beginning to fish for my wallet. “You must’ve done some kind of rebuilding job. Who’d you take over for from 2006. Some sap, I’ll bet.”

“No, that was me the year before. And the year before that.”

I shoved my wallet back into my pocket before proceeding, though I allowed, “That’s still a pretty good year.”

“It sure was. We steamrolled Piniella and the Cubs in the division series.”

“Uh-huh. Then what happened?”

“Kind of got swept by the Rockies.”

“Too bad,” I said. “But at least you gained valuable experience and built on it the next year.”