The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 12 October 2010 5:48 am Dad, I beg you to reconsider! Tractor pulls! Atlanta Braves baseball! Joe Franklin!

—Bart Simpson, imploring father to continue to steal cable, “Homer vs. Lisa and the 8th Commandment,” February 7, 1991

The most comforting thing about watching Bobby Cox’s tenure as Braves manager end — besides knowing the Braves had lost, I suppose — was where I was watching it: on TBS.

It was lovely and all that Cox could go out in front of the home crowd at Turner Field Monday night (though 8,752 fewer fannypackers showed up than had Sunday), but the real sentimental touch, however unintended, was that it aired where Braves games always used to air. It aired where Bobby Cox became a living room presence via the outlet that allowed Atlanta to become a regional team.

That region was America.

The TBS through which Ted Turner shared the Braves until they became — with only mild exaggeration — America’s Team isn’t exactly the same one it was when the concept of a “superstation” was something of a phenomenon. That TBS was WTBS of Atlanta, formerly WTCG, the Turner-owned independent channel that aired Braves games locally. Ted got himself a satellite in the 1970s and suddenly he was a genuine programming provider.

The Braves were the programming; that and a flood of old sitcoms, none more repeated than The Andy Griffith Show. If you tuned into TBS to see baseball and you were thwarted by rain, that was OK, because the superstation would entertain you with an endless supply of Andy Griffiths. Rain being as common as it is down south come summertime, you were as likely to see Barney Fife in Mayberry talking wistfully about a weekend in Mount Pilot as you were to watch a tarp being pulled in Atlanta.

Manager Bobby Cox filled the role of beloved Sheriff Andy Taylor in the Brave dugout quite amiably unless you were a short-fused umpire or a frustrated fan of a divisional foe. Cox became that kind of Griffithesque staple on TBS, same as Brave wins. Just ask a San Francisco Giants enthusiast with a long memory to recall tuning in the Superstation down the stretch in 1993. If you lived on the West Coast on the final day of that season’s scorching pennant race, you could tune in the Rockies and Braves live from Fulton County Stadium at 9:05 AM (TBS broadcasts always started five minutes later than every other frequency’s) and find out very early what kind of day you were going to have. Atlanta beat Colorado 5-3 to notch their 104th win of the year and take a half-game lead over San Francisco in the last divisional duel guaranteed to leave the second-place team emptyhanded. The Giants took on the Dodgers after the Brave result went final and got whupped badly at L.A., 12-1. The Giants wound up going 103-59…and home for the winter.

Giants fans might be feeling a measure of latent redemption for 1993 after taking this NLDS against the Wild Card Braves, a designation that was not available to their club seventeen years ago. They can be proud of their team for winning a taut — if not defensively tight — series of four one-run games and maybe more proud for the way their team took a moment from hugging and dogpiling to turn toward the Brave dugout and applaud the departing pilot of their vanquished opponents.

Twenty-nine seasons of managing were technically over for Bobby Cox once Melky Cabrera grounded to third with two out in the bottom of the ninth (and Juan Uribe didn’t throw the ball past Travis Ishikawa), yet he couldn’t disappear from view the way managers of losing playoff teams generally do. The TBS cameras caught him ducking into the runway, but the Braves fans called him back out, even as the Giants players were still on the field celebrating their victory.

Cox had to return and acknowledge that he was being acknowledged. The Giants then had the good taste to momentarily halt their obligatory orgy of self-congratulation to turn and face the Brave dugout. Suddenly the NLDS winners were applauding the man they beat. It was appropriate and it was beautiful. Cox didn’t milk it for long and the Giants soon enough beat a retreat to their clubhouse to give each other alcohol baths. In an instant, the only people you noticed wearing uniforms were members of the Turner Field grounds crew, tending to the area around home plate (what’s the rush, fellas?). The image of the 25-man cap tip in Cox’s direction, however, left everybody watching on TBS a perfect grace note to take from this postseason round and perhaps cherish during the five-day interregnum now ensuing in advance of the next postseason round.

Baseball, Keith Olbermann reflected at the outset of Ken Burns’s The Tenth Inning, is “the only sport that goes forward and backwards.” Other sports have histories, but only baseball’s is an ever present past. Cox’s past was all over Game Four of this Division Series. You couldn’t help but watch this game wind down, once the Giants took a lead in the seventh, and not think about Cox finishing up.

It reminded me of when the Mets went to the bottom of the ninth on the last day at Shea — after all the talk about how the stadium would be closing at season’s end, and how unimaginable it felt to consider that it wouldn’t be there the following year. I’d thought and thought and thought throughout 2008 of facing a future without Shea Stadium, and now there were three outs separating me from that inevitability. Maybe the Mets could score a couple, could win in extras, could play a tiebreaker against Milwaukee, could go on a postseason run…but it probably wasn’t going to happen. The inevitable was becoming that reality.

I see Bobby Cox and, though I understand his record earns him a spot on managerial Mount Rushmore (or Mount Pilot, if you will), I don’t necessarily get all the fuss about what a sweetheart and humanitarian he is. It could be because I don’t necessarily see TBS Bobby Cox, where he was the home team sheriff (and Leo Mazzone was cast as his lovable deputy). I guess I see Prime Time Bobby Cox, from the 1999 NLCS and recall how the sight of him and his seemingly impenetrable Braves angered the blood beyond healthy levels. I’m not a Braves fan and I didn’t love Bobby Cox hovering in the other dugout all these years. I surely didn’t go for how most Mets-Braves games concluded when seasons hung in their balance.

But Cox was always there, continuously since 1990, intermittently since 1978. He was on TBS almost every night for six months and then, come October, took his act to CBS or ABC (The Baseball Network, anyone?) or NBC or ESPN or Fox. TBS rebranded itself a few years ago and stopped beaming Braves baseball into every cable home in America. It became the home of the Division Series in 2007, providing a platform to promote shows nobody would ever want any part of after being inundated by an endless loop of commercials for them — where have you gone, Frank Caliendo? — and enough videotaped rope with which clueless Chip Caray could hang himself. What TBS didn’t have once October got going in ’07 and ’08 and ’09 was the Braves of Bobby Cox, which was fine. For a few nights this month, however, they did. Just in time…and just like old times, if not always great times, depending on your rooting interest.

Bobby Cox taking his final bow on his old station was indeed comforting. Jarring, on the other hand, was watching his postgame press conference, which for losing playoff managers is usually quick and dirty business. We lost, they won, that’s it is usually the extent of the public reflection. But this wasn’t going to be an ordinary Q&A for Cox. No questions about strategy. Nothing about what next year looked like. Everybody knows next year will be different in Atlanta. All the inquiries were of the “how did you feel?” variety.

It was obvious how Cox felt when he couldn’t continue with one of his answers. The man who wouldn’t stop squawking at umpires all those years couldn’t spit anything out, not for a few very long seconds anyway. “A grown man shouldn’t do this,” he said as he stood on the brink of his own rain delay. Then Bobby Cox did what they sooner or later managed to do all those nights when the Braves starred on TBS.

He pulled back the tarp and got on with the baseball.

“I can’t say enough about Derek Lowe,” Cox saw fit to interject, even though nobody had asked him about Derek Lowe. “He’s going to be a 20-game winner next year, I think, if they get him any support at all.”

It wasn’t jarring that Bobby Cox nearly broke down while conducting his final media session as a major league manager. It wasn’t jarring that the assembled media members sent him off with an ovation, prohibition on press box cheering be damned. What jarred, in the end, was that Bobby Cox referred to the Atlanta Braves as “they”.

They, not we. Their team will go forward, but without their manager.

You’ve been watching Atlanta Braves baseball on Superstation TBS. Stay tuned for Andy Griffith.

by Greg Prince on 11 October 2010 6:00 am You may recall that the one element Bobby Cox always lacked as he led the Braves through their almost endless divisional dynasty was a certifiable steel-toed, kick-ass closer. He was never able to hand the ball to a National League version of Mariano Rivera — not that there are too many of him lying around — or Dennis Eckersley. He didn’t even have a Trevor Hoffman or a John Franco, in-their-prime relievers piling up tons of saves if not inspiring the masses with confidence as they danced between baserunner raindrops. Cox had to improvise October after October, early on with ex-Mets who either weren’t that good or were no longer nearly as good as they once were.

Alejandro Peña was plucked from the wreckage of the 1991 Mets to serve as temporary savior during the modern Braves’ very first pennant drive, replacing the injured Torre-era Met relic Juan Berenguer (I can still hear the not-quite-all-there older brother of a junior high friend of mine referring to him as “Beren-jower” circa 1978). Jeff Reardon then swooped in in 1992 to pick up for the faded Peña. Reardon was a great closer a decade earlier, but by the time he alighted in Atlanta, he wasn’t the same flamethrower the Expos fleeced from the Mets in exchange for Ellis Valentine.

The record should show it was ex-Mets who sabotaged Brave hopes of obtaining the ultimate prize their first couple of chances; if only current Mets in a given year could have been so effective once the Coxmen moved from N.L. West to N.L. East.

Peña was the losing pitcher in what many consider the greatest World Series game ever played, the ten-inning, 1-0 Game Seven triumph of the Twins over the Braves in 1991, the night Jack Morris went the distance. Alejandro’s activity was overshadowed, but it occurred. After unjamming a mess of future washed up Met Mike Stanton’s making in the ninth, Peña got into his own trouble — allowing a leadoff double to Dan Gladden — and never recovered. (It’s true: the Minnesota Twins used to find ways to not lose postseason series.)

A year later, with Reardon as Cox’s trusted right arm, the Braves were three outs from taking a 2-0 World Series lead on the Blue Jays. Reardon retired his first batter in the ninth inning, but then walked future Met yachtsman Derek Bell. Bell sailed home when Ed Sprague took Reardon deep to give Toronto a 5-4 lead which their closer, Tom Henke, maintained. The Jays never let go of that momentum and the Braves wound up losing the Series in six.

Bobby Cox stayed away from ex-Mets as closers after 1992 but he never really found a pitcher to nail down that role for good for another decade. Instead, he rode hot hands as far as they would carry him, which worked only once — Mark Wohlers, in 1995. Wohlers couldn’t preserve a three-run lead in the eighth inning of the fourth game of the 1996 World Series and there went the Braves’ chance of repeating as world champs (which is fine until you recall who started their own dynasty as a result). Wohlers eventually gave way to Kerry Ligtenberg who gave way soon enough to lovable John Rocker who charmingly talked his way out of Atlanta. The Braves finally deployed big-time closer when Cox converted ace starter John Smoltz — Morris’s opponent from Game Seven in 1991 — into a reliever toward the end of the 2001 season. Smoltz, who came to relieving after a severe injury knocked him from the Brave rotation, definitely had an Eckersley thing going on for a while (144 saves from 2002 to 2004). It was fun while it lasted, but it was destined not to last because:

a) Smoltz was 34 years old when he reluctantly took on the role of closer;

b) Smoltz was essentially on loan to the bullpen until he could get back to doing what he wanted to do and was designed to do all along, which was start…and start very well despite a five-year hiatus from starting, which was one of the most remarkable retransformations any pitcher has ever made.

The last N.L. East champion Braves club, 2005’s, reverted to piecing together its ninth innings from spare parts; anybody remember Chris Reitsma and Danny Kolb? Perhaps Cox did. Maybe they and their non-Eck ilk are why he sought proven ninth-inning insurance for 2010, the year the Braves returned to regular-season glory.

That’s how Billy Wagner wound up in Atlanta. Despite his injury history and the many miles on this former Met closer, Wagner was enough of an answer to satisfy Cox after his own five-year hiatus from the postseason. Billy, 39, helped keep his latest team in first place much of the season while getting them into the playoffs as the Wild Card by the margin of a single length over San Diego.

Then, as we saw Friday night, he was gone. Wagner strained his left oblique muscle, exited Game Two in San Francisco and was removed from the Braves’ NLDS roster before Game Three — all of which combined to make the top of the ninth inning Sunday evening at Turner Field a little extra fascinating to contemplate.

Here was Bobby Cox, trying to extend the last days of his managerial career. Here were his Braves, one inning from outlasting the Giants, having withstood a marvelous outing from Jonathan Sanchez, magically taking a 2-1 lead in the eighth inning thanks to a two-run pinch-homer from the human good-luck charm Eric Hinske. Here were three outs that stood in Atlanta’s way.

The same three outs Peña didn’t get in the seventh game in 1991.

The same three outs Reardon didn’t record in the second game in 1992.

The same three outs that were supposed to be Wagner’s, according to the grand plan.

No plan now, however. Cox said he was going to improvise based on matchups, and he was good to his word.

It didn’t work. It almost did, but it didn’t.

Cox started the ninth with Craig Kimbrel. He was successful (popping up loathsome Cody Ross), then he wasn’t (walking Travis Ishigawa), then he was (striking out Andres Torres), then he wasn’t (giving up a single up the middle to Freddie Sanchez on a 1-and-2 count).

For better or worse, a big-time, big-name, big-money closer of the stature of a Billy Wagner would stay in to finish this chapter. Instead, Cox is desperate to write the ending, so he removes the pen from Kimbrel’s relatively hot right hand and passes it to lefty Mike Dunn.

Which totally doesn’t work, as lefty Aubrey Huff singles to right, scoring Ishikawa from second, knotting the game at two. So Cox does the matchup fandango again, removing Dunn and inserting righty (and Met bête noire) Peter Moylan to face righty Buster Posey. The matchup was a boon for the Braves as far as Moylan inducing a ground ball to second, but Cox didn’t factor in the matchup of ground ball versus overmatched second baseman Brooks Conrad. Posey’s grounder merely visited the area between Conrad’s feet — just passin’ through! — before E-4’ing its way into the outfield. Sanchez scored, the Giants led, and that would essentially be that for the Braves…though Cox did bring in one more reliever, Kyle Farnsworth, to get the final out of the top of the ninth.

No closer, four relievers, two runs, a 2-1 series deficit. Tough, hauntingly familiar luck for a franchise whose fairly recent history of excellence always did seem to stop at the edge of ultimate victory.

Wagner was unavailable, so no point posing a “what if?” on Billy’s behalf, but what if Cox had simply left Kimbrel in to face Huff? What if a manager who is lauded in all precincts for showing unmatched loyalty to his players had stuck with one live arm to capture one more out? What is it about ninth innings that make even a Cooperstown-bound skipper so goofy?

There wasn’t much to recommend the final third or so of the 2010 Mets season, but I personally adored the way the Mets never missed their high-priced closer once he landed simultaneously on the shelf and court room docket. I was a fan of Frankie Rodriguez. Though I’m sympathetic to arguments that teams rely way too much on closers — I’ve made them myself on occasion — I watched 2008 melt away once Wagner went down and believed we needed somebody not just dependable but stellar to take ninth innings. Rodriguez was coming off a record-setting 62-save season in Anaheim. Though he could be nerve-wracking as an Angel and showed signs he was anything but angelic in terms of temperament, I couldn’t argue at all with the Mets grabbing him off the open market.

He had his ups and downs prior to partaking in K-Rod Smackdown 2010. He was sometimes horrible, sometimes reliable, no more aggravating than any of his 1990s and 2000s predecessors. Then after one fit too many, he was out of the picture. The Mets were pretty much out of the race at that point, so it didn’t matter immensely who would pick up for him, but, still, I hoped somebody would.

And Hisanori Takahashi did. He was the anti-Frankie, the non-Billy. There was nothing exciting about Hisanori Takahashi except that he generally got results. Pulses didn’t quicken when he appeared. Music didn’t blare. The words prima and donna didn’t go steady in his presence. He was simply the guy who was given the ball to close out ninth innings when the Mets had a lead, and he went about his business professionally and effectively.

What it means for 2011 is unknown. Takahashi will be a free agent and he wants to start. He won’t be a starter with the Mets. He put in some nice yeoman work in that role when called upon, but didn’t seem to have the stuff to persevere as such once teams got a look at him. Hisanori was quite valuable as the closer pro tempore but the new manager, whoever that soul will be, wouldn’t likely be penciling him in. Rodriguez’s status is unclear for next year, but he is owed a closer’s ransom. Francisco throws hard and causes a fuss…for anybody else, that would be reflexively considered an asset; with this guy, who knows? And if K-Rod is otherwise detained (or dismissed), there will be sentiment mounting to give Bobby Parnell a long look, though he didn’t seem quite ready for the added responsibility in August.

In any event, what the Mets have experienced across their pre-Takahashi late innings and what the Braves are going through as a pressing concern right this very minute shows, perhaps, what a crap shoot the concept of the closer truly is. Unless you’ve got that stiff from the Taco Bell commercials, you really do have to kind of touch and feel your way through ends of games. You might get lucky with a Craig Kimbrel, or you may be right to feel impatient. You might miss your Billy Wagner or Frankie Rodriguez, or you might come up with a Hisanori Takahashi and be surprised how little stress you feel in the process. Bruce Bochy no doubt counted his lucky stars that Brian Wilson could get three outs Sunday after cursing the darkness Friday that he couldn’t get six.

Makes a baseball fan appreciate the following fellows even more:

• Mariano Rivera. Grrr… My friend Kevin and I like to remind each other that the guy universally considered untouchable in October gave up a series-turning home run to Sandy Alomar in 1997, a killer soft liner to Luis Gonzalez in 2001 and was unable to slam the door shut at Fenway Park in 2004. Those failures would tase closers who didn’t have other opportunities to make up for them. Rivera’s had a zillion and he’s converted, I think, a zillion. Grrr…

• Cole Hamels — also not a favorite here, but what better way to avoid relief troubles than by avoiding relievers? Hamels Sunday night tossed a five-hit, nine-strikeout series-clinching shutout that, to date, stands as only the third-best starting pitching performance of this postseason. More Hamels, more Halladays and more Lincecums, and you’d have less nonsense in ninth innings.

• Tug McGraw, for what he did 37 years ago yesterday. With a tiring Tom Seaver having loaded the bases with one out in the top of the ninth in the deciding game of the 1973 NLCS, Yogi Berra called on his indefatigable fireman to secure the Mets’ second pennant in five years. Sure enough, on October 10, 1973, Tug popped Joe Morgan up to short and grounded Dan Driessen to first. The Mets won 7-2, took the series 3-2 and successfully bolted to their clubhouse with their lives intact in the face of onrushing Shea hordes (who had a funny way of showing their love back then).

All the other lifesaving Tug had done in the previous six weeks was figurative, but it was just as valuable to the Met cause. His final five saves down the stretch in ’73 — when all that was at stake was Met survival — were recorded in outings that lasted 2⅓; 3; 3; 2⅓; and 3 innings, respectively; the last of them was the division-clincher in Chicago. During that same fifteen-game span, McGraw picked up a pair of wins after pitching 1⅓ innings and 2 innings of shutout baseball.

We’re so used to doubting our closers, you may be surprised to learn we had no problem believing in Tug McGraw as 1973 was becoming 1973. We encapsulate his essence in a pitch-perfect slogan, and we revere his singular personality (while we continue to try to derive some good from his untimely passing), but something else is worth noting about Tug McGraw, particularly if you weren’t around to see him in action during his signature season as a Met:

That screwball could really pitch when it really mattered. You have someone who can do that in a given September and October, you don’t take it lightly, and you never forget it.

Thanks for that, Mr. McGraw, wherever you are.

by Greg Prince on 9 October 2010 7:57 pm Funny how little you know about a baseball team until you spend some time focused on them. The San Francisco Giants, for example, disappeared from my radar screen the moment the Mets were mistakenly awarded a victory against them in the middle of July. And the Atlanta Braves? We saw them as recently as the third weekend in September, but they were playing the role of opponents. Opponents never fully capture my comprehension.

Now both the Giants, a team that’s always been on my take-or-leave pile, and Braves, a team I wish had been left in their pre-1994 division so they never would have grown into quite such a Met obstacle, are teams I’m following closely. I have little choice if I want to watch baseball in October.

What struck me about these particular playoff combatants as the drama in their NLDS ratcheted up exponentially late Friday into early Saturday is how many familiar names and faces dot each roster. Yes, they look familiar and they seem familiar, but the context is strange. I may have been intellectually aware that these individuals were presently wearing Giants uniforms or Braves uniforms, yet to see them competing as Giants or Braves when it mattered most…it was jarring. This isn’t about intellect. It’s about instinct.

I instinctively know these guys can’t be who they say they are.

Pat Burrell, Giants: Pat Burrell powered the Giants to an early 3-0 lead when he took Tommy Hanson deep to left in the first inning. HUH? Pat Burrell is that phucking Phillie Met-killer who started hitting home runs at Shea in 2000 — including the longest one I ever saw (it bounced over the back fence of the visitors’ bullpen and into the parking lot) — and hasn’t yet stopped. What do you mean he hasn’t been a Phillie in two years?

Edgar Renteria, Giants: Edgar Renteria laid down a beautiful bunt to start what appeared to be the winning rally in the bottom of the tenth. HUH? Edgar Renteria drove in the winning run in the 1997 World Series, seventh game, eleventh inning, single through the middle to plate Craig Counsell. Edgar Renteria is a world champion Marlin, a real budding star. What do you mean he’s 34 and on his sixth team?

Troy Glaus, Braves: Troy Glaus turned one of the gutsiest double plays I’ve ever seen, going around the horn with Buster Posey’s one-out, bases-loaded grounder to end the bottom of the tenth instead of firing home. If anything goes wrong on the attempted 5-4-3, the game is over and the Giants win. HUH? Troy Glaus breaks Giants hearts, sure, but he does it as the slugging Anaheim Angel who won the 2002 World Series MVP award by bashing three homers and hitting .385. What do you mean it’s been almost a decade since Troy Glaus was besting Barry Bonds for all the marbles?

It felt like this all night as the Giants’ 4-0 lead melted into the Braves’ 5-4 win. Freddie Sanchez isn’t a Pirate? Aubrey Huff isn’t a Devil Ray? That little bedbug Cody Ross gets to be in the playoffs? The most dramatic examples were the two ex-Royals whose stays in Kansas City all but escaped my attention earlier this season.

• Kyle Farnsworth was the winning pitcher. Last time I thought about Kyle Farnsworth, I was advising some Yankees fan in the winter of 2005 that no matter how fast you think he throws, you don’t want to trust this new setup man of yours with anything of substance (I was right then, less so now).

• Rick Ankiel was the winning hitter. His story is too famous to facilitate disingenuousness regarding what he’s been doing for the past ten years, but the name “Rick Ankiel” will always mean pitcher, not hitter to a Mets fan — tragic figure from 2000, not hero in 2010…not until last night anyway.

When Ankiel pulled a J.T. Snow of sorts (speaking of ten years ago), my right arm, the one I use for raising in triumph, shot up on his behalf. That surprised me, as I wasn’t rooting for the Braves, but I guess I liked the great story suddenly unfolding — both in the sense of scatter-armed phenom hurler having completely re-established himself as an offensive force in postseason play, and because it was good to see somebody come back on anybody this month. Winning teams were ahead in their League Division Series by a collective seven games to zero entering this particular contest. With Burrell’s homer and then some in the books, it looked like the orange-clad Giants had relegated the Braves to hopeless pumpkin status and we would be lulled to sweep everywhere in this round. But the Braves were making a set of it after all, down by four, now ahead by one. That alone seemed worth cheering for.

As would be the return, somehow, of Braves closer Billy Wagner, should we be lucky enough to see it.

If Billy hadn’t been a Met, I might have the same cognitive dissonance issues with him as I’ve had with all the other mercenaries on the field last night (whaddaya mean he’s not an Astro anymore?), but once you’re a Met, you’re a Met all the way, and I keep tabs to your last playing day. Like anybody else even slightly sentient this season, I knew Billy Wagner was saying goodbye to America whenever he got through pitching in 2010. When he came on to start the tenth, I treated his appearance like I have every Billy Wagner appearance since he came to be one of us in 2006 — I greeted it with ambivalence.

Oh, of course I wanted him to succeed as a Met when he was taking our big innings, just as I rooted against him as a Brave when he was facing us this year, but I’ve never decided how I really feel about him. I read wonderful stories like this one Michael Bamberger wrote in Sports Illustrated and I want to cheer him on. Then I remember how he got on my nerves for multiple reasons as a Met — mound-related mostly, but occasionally for not sticking up for a teammate. There was one game in 2008 when Oliver Perez simply didn’t have it (big surprise, I know) and Wagner called him out in the press for the crime of making the bullpen work overtime that afternoon, a day game after a taxing night game. You mean Perez wanted to blow up early? I’m no fan of Ollie — who is? — but even I assume a pitcher would rather succeed than fail. It seemed like the sort of criticism you address in private, not in the papers.

Then again, there was something to Billy Being Billy that couldn’t help but be appealing. He apparently said what he apparently meant. In this David Waldstein Times story on the potentially waning days of the Los Mets brand, for example, there seemed a good opportunity for Wagner to take a parting shot at certain former fellow Mets and pile on the Mets at a moment when piling on the Mets was de rigueur. But he didn’t go for it. I appreciated that.

His Met pitching? Like any other closer’s, I appreciated it when it wasn’t hair-raising. When it was, hoo boy. After the recent Ken Burns documentary aired on Channel 13, they ran a New York-centric version in which fans of all four NYC teams shared their baseball recollections. One of them, a Mets fan, chose to elaborate on the atrocities of May 20, 2006 — Pedro Martinez’s seven sparkling innings (four hits, eight strikeouts), Duaner Sanchez’s clean eighth, the Mets leading the Yankees 4-0 and in came Wagner.

Single. Walk. Run-scoring single. Flyout. Walk. Run-scoring walk. Run-scoring hit by pitch.

Seven batters, six baserunners, three scored, three willed to the next guy, Pedro Feliciano, who couldn’t prevent the score from being tied. The Mets went on to lose in eleven.

Fuck PBS, I thought as I watched it all over again. And fuck Billy Wagner, I thought that Saturday afternoon (and the Sunday morning after) four years ago and not a few times during his Met tenure. The horror shows wrought by closers are never fully countered by the saves, particularly the saves that don’t come easy. No matter what he did after May 20, 2006, Billy Wagner was always the guy who let a 4-0 lead over the Yankees dissipate into a 5-4 loss. Or the guy who entered a tied second game of the ’06 NLDS and allowed a leadoff home run to So Taguchi and two runs after that. Or the guy who very nearly let life-or-death Game Six slip away (another 4-0 lead, this one cut to 4-2 — Taguchi doubling home Juan Encarnacion and Scott Rolen). Or the guy who disappeared down the stretch in 2007 and couldn’t remain in one piece in 2008.

Mad at a closer I didn’t trust for not staying healthy so I could not trust him some more? It’s a little short on logic, but it comes with the highly compensated three-out territory.

Billy Wagner, too close to Y.A. Tittle territory for comfort. When Wagner came on Friday night, I was sort of rooting for him to succeed, sort of not. What I wasn’t rooting for was him straining his left oblique muscle while fielding Renteria’s bunt in the tenth. Nobody noticed he had hurt himself and Billy didn’t say anything. Everybody noticed he had hurt himself after his next pitch was put down for a sacrifice by Andres Torres. Billy threw it to first and then went down on one knee grabbing his side. He didn’t look a whole lot different from Y.A. Tittle in his bloodied, beaten, can’t go on any longer moment made iconic by this photograph, taken by Morris Berman in September 1964…though Tittle actually kept quarterbacking the Giants for another dozen games before calling it quits.

Can Wagner pick himself up, dust himself off and relieve all over again? They’ll check on his well-being tomorrow, but it doesn’t look good for the NLDS or, almost certainly, the NLCS. Maybe the World Series.

But the Braves would have to get to the World Series. That was Wagner’s stated reason for working his way back from the elbow miseries that sidelined him as a Met in 2008 and signing as a Brave in 2010: one more shot to get where he never quite landed as an Astro, Met or Red Sock in six previous postseason attempts. Can the Braves get that far without their closer? Well, they won their first Division Series game after Wagner was compelled to limp away. The dirty little open secret of last night’s extra-inning drama was Billy bequeathed to Farnsworth a man on second with one out. Had his oblique been fine, you think Wagner would have kept Renteria from scoring? Would have provided an opportunity for Ankiel to homer into McCovey Cove and send the series back to Atlanta 1-1 instead of 2-0 Giants?

I don’t. But maybe that’s Billy Wagner the Met I’m seeing out there.

by Greg Prince on 8 October 2010 8:58 pm Welcome to Flashback Friday: Take Me Out to 34 Ballparks, a celebration, critique and countdown of every major league ballpark one baseball fan has been fortunate enough to visit in a lifetime of going to ballgames.

BALLPARK: Turner Field

HOME TEAM: Atlanta Braves

VISITS: 1

VISITED: April 5, 1998

CHRONOLOGY: 20th of 34

RANKING: 9th of 34

By the final Sunday of the 1998 baseball season, I’d have nothing good to say about the Atlanta Braves nor anything good to think about their home ballpark — we would be swept there to end that star-crossed season and we would be defeated six out of six times in Dixie when all was said and done that year. But those feelings were still nearly six months from fully materializing on the first Sunday of the 1998 baseball season. I spent that first Sunday at Turner Field in Atlanta, and I came away thinking nothing bad at all about a team I was about to spend the next half-decade truly loathing and a stadium of which would provoke in me nothing but Met fear.

But this particular afternoon wasn’t about fear or loathing and it wasn’t more than peripherally about the Mets (who were represented by the cap on my head and my inveterate applauding of the visiting first baseman, ex-Met icon Rico Brogna). It was about extreme satisfaction with a venue and intoxication by the performance put on within.

Turner Field was that good that day. And the game was even better.

I developed a theory about Turner Field after spending nine sublime innings in its company. It had to do with the name on the door. Something about Turner Field looked and felt uncommonly perfect for baseball. It transcended what we were already calling “retro”. Turner Field didn’t feel retro. It felt traditional, like if you had to conjure a “ballpark” in your mind, you might come up with how this one looked while you were sitting in it.

Ted Turner, I thought. Ted Turner’s in the entertainment business. Ted, I decided, put his best showbiz people on Turner Field. He called in his set designers after the 1996 Olympics were over, before the stadium would be converted for the Braves’ use, and said give me something that allows our patrons to get lost in baseball as they watch our games: not gimmicky, nothing distracting, just appropriate.

If that’s the way it happened, then thanks Ted; it worked. And if it didn’t go down that way at all, it’s enough that I believe it.

Maybe it was the seats I had (Loge-like) or the shadows enveloping home plate (as they will anywhere in early April) or, ultimately, the kind of game I had the good luck to draw out of a proverbial hat when I ordered my tickets in the offseason (the date was keyed to a craft brewers conference I just had to cover for my magazine). However it happened, it all came together. My circumstances coalesced magnificently at Turner Field. Perhaps mine was a unique experience, as I’ve rarely heard anybody else include the Ted as one of the best ballparks going.

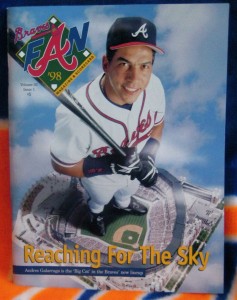

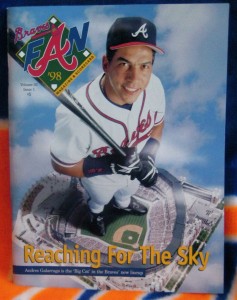

Turner Field went light on many of the flourishes on which its contemporaries rely. It’s got plenty of bricks (1.265 million of them, according to my copy of Braves Fan Magazine & Scorecard) and it features terraces and plazas and its share of modern-day distractions, but I never sensed any of it getting in the way of the game. Those things were there if you wanted them — I loved that there was a wall of TVs showing all other in-progress games from around the majors, particularly Pirates at Mets — but they didn’t pull you away from the action.

I also loved that only so many molds were broken in the building of this ballpark, architectural peer pressure be damned. Intimate? From my seat, absolutely, but the capacity was a shade over 50,000. What good is a team that wins its division with disgusting regularity if you can’t have everybody over whenever they want to drop by? And the dimensions of Turner Field were close to symmetrical: 335-380-400-390-330, not a sharp corner in sight. This wasn’t a popular tack to take in the 1990s, as everybody was going for quirky, desperately evoking what street grids made unavoidable when the old century got going. It was charming to a point, but it struck me as pretentious after it was repeated endlessly in ballparks that went up in parking lots. I appreciated Turner Field not forcing the matter.

It may not have been a lyric little bandbox à la Fenway and it may not have produced 289 different angles off its scoreboard like Ebbets, but it didn’t have to. Those places were the way they were because of where they were built. Turner Field did fine being what it was without being overly cute about it. It hit its marks is what it did.

It also served as a soundstage for what I’ve always referred to internally as The Duel in the Sun, which is probably the most compelling reason I left Turner Field feeling so good about the place. The starting pitchers for that Sunday game between the visiting Philadelphia Phillies and the homestanding Atlanta Braves were Curt Schilling and Greg Maddux.

How great does that sound? Not nearly as great as it actually was.

I was still glowing from the first game I saw in 1998: Opening Day at Shea, a classic in its own right. The Mets won 1-0 in 14 innings over those same Phillies. The starter for us had been Bobby Jones, the starter for them was Schilling. We won, but their starter pitched most sensationally: 8 innings, 2 hits, 1 walk, 9 strikeouts. That it was the first game of the season made it all the more impressive — aren’t these guys supposed to take it easy coming out of the gate?

Now I was following Schilling to Atlanta and realized Opening Day was just a warmup for him. As for Maddux…he was Maddux. He went eight innings against Philadelphia that sunny, shadowy Sunday at Turner Field: in 96 pitches over 8 innings, he allowed just 5 hits. His only walk was intentional and that was in service to untangling an eighth inning that went like this:

• Chipper Jones error on an Alex Arias grounder

• Curt Schilling sacrifice bunt, Schilling safe at first

• Doug Glanville sacrifice bunt

• Intentional BB to Gregg Jefferies (2-for-3) in hopes of teasing a ground ball double play out of Scott Rolen

Rolen overcame Bobby Cox’s strategy by lifting a fly ball to right for the second Phillie run — unearned. It broke a 1-1 tie. Philadelphia earlier scored on a 4-6-3 DP. So Maddux didn’t allow any opposing batter to drive in a run off of him. Pretty darn good, huh?

Nevertheless, Schilling, a very different type of pitcher, was better and it was still barely enough to top Maddux. After he struck out his first two hitters in the first, he gave up a pretty convincing home run to Chipper/Larry. Then he struck out Andres Galarraga, and he never looked back. Curt Schilling outpitched Greg Maddux in the fifth game of the season, just as he outdid himself from Opening Day against the Mets: 9 innings, 5 hits, 1 walk and just that solo blast early for the only Brave run.

And 15 strikeouts.

The thunderous Atlanta Braves couldn’t touch Schilling. Galarraga alone struck out 4 times. Jones and (bafflingly) Rafael Belliard were the only starting Braves who didn’t K. It was phenomenal watching this battle of styles unfold. Maddux the craftsman, Schilling the power thrower. On this unbelievably perfect early April afternoon in what would become the year of the home run, pitching ruled.

So did Turner Field.

by Greg Prince on 7 October 2010 8:17 pm There are three postseason games scheduled this October 7. By definition, they are all lacking a certain something. What is it? Oh right — us.

Once upon a time the Mets played postseason games on October 7. Once upon three times, actually…or thrice upon a time. However you measure it, let us recall the three best October 7 games in Mets history (all tied for first):

October 7, 1973. Tom Seaver had been sublime in the National League Championship Series opener, striking out 13 Big Red Machinists, walking none and allowing just six hits in a complete game. Alas, the last two safeties on his docket were a Pete Rose home run with one out in the bottom of the eighth and a Johnny Bench home run in the bottom of the ninth. As the totality of the Met attack that day at Riverfront Stadium was accomplished via a Tom Seaver double, the result was a heartbreaking 2-1 Met loss. Thus, on October 7, the next Met pitcher would somehow have to be even better than Seaver. And he was. Jon Matlack quelled the Reds even more effectively than his more celebrated rotationmate. The sophomore lefty struck out nine, walked three and surrendered no hits at all to the likes of Rose, Bench, Joe Morgan and Tony Perez. He did give up two hits to the likes of journeyman right fielder Andy Kosco, but nobody wearing red scored that Sunday. The Mets were about as blue offensively as they had been the previous afternoon, clinging to a 1-0 lead most of the game (thanks to a solo home run off the bat of Le Grand Orange), but they finally broke it open with four much-needed runs in the top of the ninth. Appropriately cushioned, Matlack went out to complete the game: Morgan flied out, Perez flied out, Bench struck out. Mets win 5-0, tie NLCS 1-1.

October 7, 2000. Sure, I could tell you all about this one, too, but I’ve done that before. You’ll recognize it as the Benny Agbayani Game, the one our electrifyin’ Hawaiian won with one swing of his magic bat in the bottom of the thirteenth inning. For a fresh perspective/special treat, I direct you to Amazin’ Avenue, where Matthew “Scratchbomb” Callan has been expertly recreating the entire 2000 season and postseason these past few weeks. You’ll get tenth-anniversary chills when you read his account, appropriate given not just the subject matter but how cold it grew in the Upper Deck of Shea as that particular Saturday turned to night turned to ice. Don’t worry, you’ll feel warm all over by the end. Mets win 3-2, lead NLDS 2-1.

October 7, 2006. Has it been four years already? I’m afraid it has. The Mets returned to Dodger Stadium for their first playoff game in Los Angeles in eighteen years. The last one hadn’t worked out so well, but this was going to be different. Orel Hershiser wasn’t on the mound for the Dodgers and the Mets’ backs weren’t against the Chavez Ravine wall. With a 2-0 series lead, Willie Randolph handed the ball to Steve Trachsel. Trachsel…he was no Matlack, but his opposite number, the late-period Greg Maddux, was no Hershiser. The Mets piled on the relief pitching and the runs and slightly before midnight EDT they avenged 1988 with a rousing victory that sent them soaring to the NLCS. Several hours earlier, the Detroit Tigers won their ALDS matchup, which would be neither here nor there, except the Tigers ushered New York’s other baseball team to the postseason exit, which made us understandably and uncontrollably giddy. The legend of Holy Saturday (fleeting but fantastic) was thus born. Mets win 9-5, win NLDS 3-0.

One month from the marathon, Sharon Chapman keeps running for Tug. Speaking of births and October 7, Faith and Fear in Flushing wishes a most happy birthday tonight to a reader whom we hope enjoys a longer and ultimately more successful run this fall than the aforementioned beloved Mets clubs did in their respective autumns, Sharon Chapman. She’s one month from lacing up her running shoes and taking on the New York City Marathon and, as you may know, she’s been making her strides under the auspices of official blog sponsor FAFIF. She’s got the wristband to prove it, as she showed just the other week while acing Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue Mile.

Most inspiring of all, Sharon has used her year on the run to raise funds for the Tug McGraw Foundation, which is devoted to fighting the scourge of brain tumors. You can read about their great work here. Thanks to Sharon and everybody who has contributed to her cause — including readers like you — nearly $6,000 has been raised to help battle the disease that felled 1969 and 1973 Met hero Tug McGraw and remains too much of a factor for too many others. The Foundation seeks effective treaments and attempts to make the lives of those who suffer tangibly better. It isn’t easy, and they need all the help they can get.

You know how you’re not spending a dime on Mets postseason tickets or gear in 2010? If you could take just a smidgen of that windfall (let’s call it the Fourth-Place Dividend), whatever you can afford, and direct it toward the Tug McGraw Foundation here, I think you’d find yourself revisiting that “warm all over” feeling once again.

You Gotta Believe you’ll like how you feel, no matter who’s not playing ball this October 7.

by Greg Prince on 7 October 2010 3:40 am Geez, Roy Halladay’s good. Or as one of my dear friends in all matters Mets put it, “Can’t believe you wanted him to pitch the no-hitter. F history, F the Phillies.”

Normally, yes, but this was something F’ing special. The Reds weren’t coming back. Games aren’t over until they’re over and all that, but it was pretty F’ing obvious Cincinnati could only dream of maintaining high hopes in this one. We’re nine outs, six outs, three outs from watching the only postseason no-hitter anybody has ever seen on color television. I know it’s the Phillies, I know we hate them in Yankeesque proportions, I know it’s anathema to not want anvils falling on every red-capped head at Citizens Bank Park — pitcher’s mound included — but it wasn’t like the Mets were gonna pick up a half-game in any of this.

Or, if I may invoke the 1992 election for the second time in a week, the first George Bush settled with minimal hesitation into his chair on the Truman Balcony to watch the fireworks show hailing the imminent inauguration of Bill Clinton, the man who was sending him packing from the White House. What the hell, the outgoing president said to a companion, we’ve got the best view in town for this.

Mets fans have grown accustomed to great views of postseason baseball on TV just as we have no-hitters beamed in from distant precincts. So if the two things we can’t have are right in front of us, we might as well sit back and enjoy as best we can.

I enjoyed watching Halladay close shop on the Reds. What an exclamation point on this lower-case year of the pitcher. What a game of catch he was having with Carlos Ruiz. It looked quite a bit like the night Armando Galarraga was dealing to the Indians, but those were the Indians. These were the Reds, from the hard-hitting portion of Ohio. This was the playoffs, for goodness sake. This was a brilliant pitcher who toiled in relative obscurity — also known as Canada — for more than a decade. Shouldn’t stepping up to the big stage make a fella a wee bit nervous?

Didn’t seem to bother Halladay. As the game wore on, he grew untouchable. The only Reds bat that remotely threatened his exquisiteness was a bat left on the ground. Brandon Phillips whacked Halladay’s last pitch a good 80 or 90 inches and his lumber threatened to tangle up immortality the way Jim Joyce got in the way of Galarraga’s. But stuff like that never seems to work against the Phillies, does it? Ruiz pounced on the ball, threw it to first and Halladay completed the no-hitter in as mussless, fussless fashion as one could imagine.

The man was so calm afterwards. Perhaps he was dazed or, more likely, he’s immensely professional. Halladay gave interview after interview indicating all the satisfaction of a man who had gotten his throwing in before running wind sprints in Clearwater in February. He didn’t seem unhappy (he’s not Steve Carlton) but he kept his emotions in check. Good move. It’s Game One. The Reds were through before they even started Wednesday, but even these short series can become long series, and Cincy — league leaders in home runs, runs scored, batting average and OPS — has been known to hit.

Just not off Roy Halladay, just not in Game One of this particular NLDS.

The Phillies were pretty good a year ago, but all they had by way of reliable starters was Cliff Lee (who’s still pretty good), and they traded him. Yet here they are, deeper than ever in the pitching department. Roy Halladay replaced Lee. Cole Hamels returned from his sabbatical of immaturity and, for good measure, they nabbed Roy Oswalt at the trading deadline. If the no-hit bid had been Hamels’ or Oswalt’s, I probably would have passed on history. Hamels has a big mouth. Oswalt once brushed back Cliff Floyd a little too feistily. Halladay? All I really knew about him before 2010 (beyond his numbers) was now and then I’d flip by YES when the Yankees were in Toronto and he’d be winning 6-1. I have nothing against this guy beyond his uniform and how good he is in it against us.

But, again, we’re not there. The only no-hitter we were a part of last night happened 35 years ago and, per usual, it didn’t actually happen. After the traditional October Twinplosion occurred on TBS, I discovered Mets Yearbook: 1975 was reairing on SNY. It was expert propaganda in its time and of course it holds up beautifully. Mike Vail, Roy Staiger, Mike Phillips, Ken Sanders…good lord, we’re going to be great in ’76! In the midst of all this spectacular futurizing, there’s Randy Tate, the fourth starter in a rotation that begins with Tom Seaver, Jon Matlack and Jerry Koosman. Tate was a 5-13 pitcher in his one and only major league season, running up an ERA of 4.45, but he did have his moments in 1975, just about all of them one night at Shea against Montreal.

As the highlight film elaborates and a shot of the scoreboard illustrates, Randy Tate has pitched a no-hitter through seven innings. The Shea crowd of 10,720 is applauding heartily as Tate strikes out his first batter, Jose Morales, in the top of the eighth. What the film doesn’t show is a 12-year-old version of myself, in the bathtub, hanging on Bob Murphy’s every word. No Mets pitcher has ever thrown a no-hitter, but young Randy Tate now stands five outs… And with that reality acknowledged over WNEW-AM, Jim Lyttle singles. There goes the no-hitter, but the Mets are still winning 3-0. Four batters later (Pepe Mangual, Jim Dwyer, Gary Carter and Mike Jorgensen — every one of them eventually a Met), Tate is on the wrong end of a 4-3 score. When the game is over, his record falls to 4-10.

But not to worry. Randy Tate, according to the 1975 highlight film, will be a big part of the Mets’ plans for years to come.

In a sense, he is. I’m still waiting for someone to pick up his final five outs. I’m still waiting for the first no-hitter in Mets history. Therefore, I’m still amenable to generally rooting for no-hitters that don’t do us direct damage in lieu of relishing one of our own. We have none of our own 35 years since Randy Tate couldn’t put away the Expos — eighth in the National League in home runs, tenth in runs scored and OPS, last in batting average.

It would have been pretty F’ing special if Randy Tate could have no-hit the Montreal Expos on August 4, 1975.

by Greg Prince on 5 October 2010 2:34 pm George H.W. Bush, one of six U.S. presidents to have served while a Wilpon has been running the Mets, once attempted to combat perceptions that he was oblivious to people’s problems by declaring, “Message: I care.” Bill Clinton, the president who succeeded him when that message proved unconvincing, famously empathized with Americans, “I feel your pain.”

Constituencies don’t want to hear that you get it. They want to know that you get it.

Fred Wilpon and Jeff Wilpon, as of yesterday, seem to get it.

Monday morning, the Band-Aid that inadequately covered the wounds inflicted by every Mets mishap that has transpired since the night of October 19, 2006 was ripped from the Body Metropolitan in one quick (if you’ll excuse the expression) yank. The manager was removed. The general manager was removed. As twinbills go, this was a double beheader sweep.

You of course recognize the concomitant firings of Omar Minaya and Jerry Manuel as a big story, but you may not realize that it’s essentially unprecedented in these parts. The Mets have dismissed skippers before and they’ve axed GMs before, but they’ve never done it on the same day before — never. Changes in front office and on-field administration have occurred in close proximity a couple of times, but they had never previously been coupled like this.

It’s not a trivial distinction.

I don’t believe the ownership of this baseball team, when given time to prepare, uses any words it hasn’t chosen extremely carefully. Fred Wilpon sat in front of a room full of cameras, microphones and notebooks Monday and said these past four years have been the most “painful” he’s experienced in the three decades he’s been an owner of the New York Mets. Jeff Wilpon added, “We failed.” Those words were designed to leave no room for interpretation. Neither were their actions.

There were no rationalizations, no paeans to patience in the face of a crying need for urgency. An organization that has reliably hobbled itself with half-measures…

• not sacking Davey Johnson when it was clear Frank Cashen was itching to deliver the pink slip;

• waiting so long to split GM duties between Joe McIlvaine and Al Harazin that McIlvaine slipped away to San Diego;

• replacing Harazin with McIlvaine seven weeks after Dallas Green replaced Jeff Torborg;

• supplanting McIlvaine with Steve Phillips while leaving McIlvaine’s manager, Bobby Valentine, firmly in place;

• allowing Phillips to undermine Valentine by taking away three of his coaches;

• bouncing Valentine while retaining Phillips;

• attempting to lure Minaya back from Montreal after one year away with an offer to share responsibilities with Jim Duquette;

• getting rid of Art Howe without actually sending him away;

• flying Willie Randolph across the country and giving him one more game before telling him at midnight local time (3 AM in New York) that he was being let go;

• and steering Minaya out of the spotlight after his embarrassing attack on Adam Rubin’s character, but letting him linger in his high-profile job for more than a year

…went the distance this time.

The next general manager won’t be saddled with a manager he didn’t hire. The next manager won’t have to wonder quite as much what dysfunctional situation he’s walking into. The next GM and the next manager will be coming in together, as close to arm-in-arm as they possibly could. It may not represent an instant formula for winning, but it’s worth trying.

Everything before this did fail. And it was painful.

If Fred Wilpon carefully chose to call 2007 through 2010 the worst of the worst of a tenure that’s included oldies but goodies like 1993 and 2002, it may have been for effect (message: he cares), but it wasn’t without cause. The Mets have played worse under previous Wilpon-approved regimes, but in ways tangible and otherwise, they may never have been worse than they’ve been lately.

Somewhere on a legal pad at Citi Field, it’s quite possible someone jotted down the notation that 79-83 was the best losing record the Mets have ever posted; that at four games under .500 — a net difference of two — they weren’t really that far away; that they did contend until the All-Star break in 2010; and that we sure have had a run of bad luck that is bound to change. If everything’s gone this wrong for this long and we didn’t completely disintegrate into the Pittsburgh Pirates, then maybe we’re doing something right, and what we need to do is make a few adjustments and otherwise stay the course.

That would have been a half-measure. A half-assed measure, at that. It’s what I would have expected out of the Mets after 2009. It’s what we got. It led us in 2010 to the best losing record the Mets have ever posted.

Which isn’t progress. Which isn’t close to progress. Progress is admitting that the Mets have failed for four consecutive seasons. It’s not a selling point, but it is reality, and since selling points weren’t exactly filling the new ballpark, truthfulness as a first step toward genuine progress — along with maybe not failing in a fifth consecutive season — is most welcome.

I’m guessing what’s made 2007-2010 most painful to Fred Wilpon is that the Mets so seemed to be on the right track in 2005 and 2006. This — collapse, collapse; debacle, debacle — wasn’t supposed to happen to them again, certainly not so soon. Almost every team endures up cycles and down cycles. The Mets’ up cycle, however, stalled after only two seasons. In the four seasons that followed, the Mets averaged 81.5 wins per year, but nobody who has watched them closely (or even casually) since Called Strike Three could possibly call them winners over that span.

This wasn’t supposed to happen. Omar Minaya was supposed to prevent this. A high payroll, supported by the revenue streams provided by a heavily viewed proprietary television network and a well-attended state-of-the-art 21st century stadium, was supposed to prevent this. 2006, when the Mets won the National League Eastern Division, SNY debuted and Citi Field began to rise, was supposed to be a launching point…a template. You would have figured your only October press conferences for years to come would be the kind MLB makes managers and starting pitchers do before and after postseason games.

The leading indicators and the great vibes that were in such evidence in October 2006 turned out, alas, to be an aberration. Everything that went wrong before 2005 and 2006 started going wrong again after 2005 and 2006. The New Mets were at best a passing phenomenon…a mirage. The Mets bought a bunch of the right players while they were still capable of performing at something approaching their best; they mixed them with the only two star players they’ve managed to produce in the past generation; and they sprinkled in a few key ancillary parts. The results were wonderful.

Then they were over with. On the surface, the Mets proceeded after October 19, 2006 in the same manner they had before. They weren’t afraid to spend, they sought complementary components, they continued to nurture their two homegrown stars. It just didn’t work as well. Then it worked hardly at all. The Mets who were going to be special deteriorated into disappointments, heartbreakers, buffoons and, at last, utter ordinariness. The afterglow of 2006 was snuffed out by the way 2007 ended. The midyear revival of 2008, under Manuel, evaporated as that season’s déjà vu conclusion doubled down on the previous year’s devastation. 2009 was an avalanche of awfulness that 2010 could never quite dig out from under.

Attendance remained strong in 2007 because 2006 raised the excitement level around Metsdom to stratospheric. The final season of Shea Stadium provided a one-time extraordinary boost to the gate in 2008, and 2009’s advance ticket sales couldn’t help but be plentiful with the debut of Citi Field. But the seats grew emptier and emptier as the annus horriblis ensued and they never refilled in 2010. The logical conclusion was the gaunt final month we just lived through in Flushing.

Nobody was home.

The back catalogue of Met disasters is voluminous, and the Tal-Met-ic scholars among us can spend hours debating and dissecting why any one of them was worse than all the others. But even if Fred Wilpon’s designation of this particular now-completed blue period as the most painful was a line massaged to let us know he feels our pain, it doesn’t mean it wasn’t an accurate assessment. The Mets as an organization really tried with this arrangement, this era. They really thought they had something. They did, for a while. 2006 was really something. As a veteran of the good times as well as the bad, I can vouch for 2006 as a member in good standing of the pantheon. Never let Yadier Molina’s last swing — or Carlos Beltran’s last take — obscure the joy that emanated continuously from those Mets that one magical season. It was a sensation so strong that while it was in effect, it would have been positively unfathomable to believe it would be the only magical season of its time.

But it was. Once the Reds, the Rangers, the Giants and the Braves take the field this week, there will have been 19 different baseball teams to have played a postseason baseball game since October 19, 2006, the night the Cardinals defeated the Mets for the National League pennant. Two nights later, the Cardinals were playing the Tigers in the World Series. One year later, an entirely different cast of characters was competing in the postseason. And so it’s gone until we’ve reached this point at which the following clubs are the only ones to not play a meaningful game in October after 10/19/06:

The Orioles. The Blue Jays. The Royals. The Mariners. The Athletics. The Padres. The Astros. The Marlins. The Nationals. The Pirates.

The Mets.

That’s the company we keep. Four years since the future couldn’t have appeared any brighter, we are consigned to the shade with the also-rans and the have-nots. We’re still a big-market team, we’re still a high-payroll team, but we are also a go-nowhere team.

Which is why Fred Wilpon and Jeff Wilpon had to go to their offices Monday and tell two men they hired and they liked that they would be relieved of their roles. It’s also why the Wilpons will have to figuratively leave the organization themselves to find a new general manager who, in turn, will have to find a new manager. That’s the way it has to be: new blood, fresh perspective, whatever you want to call it.

The Mets haven’t reached outside their own frame of reference for a head baseball man since Fred Wilpon and Nelson Doubleday reached out to Frank Cashen on February 21, 1980. Before that, the Mets, in the days of Payson and Grant, hadn’t picked an outsider to lead them since November 14, 1966, when they lured Bing Devine from St. Louis to succeed George Weiss. Weiss, hired as Mets president on March 14, 1961, also came from outside the organization, but he had to, as there was no Mets organization to that moment.

You might say there isn’t one now, at least not in the sense that the Mets are organized for what lies ahead in 2011. No general manager, no manager…I wouldn’t say “no problem,” but this is the necessary next step. This is the starting-over point. The Mets need to start over and they are, as Weiss’s most famous hire liked to say, commencing to do just that.

Even if the search for new leadership in the autumn of 2010 is not as invigorating as it might have felt on September 29, 1961 — the day Casey Stengel came on board; or makes being a Mets fan as thrilling as it was on this very date in 2006 — the evening Willie Randolph managed the team Omar Minaya constructed to a 2-0 NLDS lead over the Dodgers, it’s still pretty exciting. I don’t know who the GM will be and I don’t know who the manager will be, nor do I have a favorite for either spot beyond a fervent hope that the right people will be selected. I’m just gratified there will be a selection process. I’m relieved that the owners of the New York Mets recognized this had to be done.

Now, of course, I hope they don’t screw it up. Today, with nobody yet having made any obvious mistakes we know of in the selection process, I will cling to that hope. The Wilpons spoke their version of truth to pain, truth to failure yesterday. In an October when the Mets again have no games remaining, after a fourth consecutive season that guaranteed that paucity of meaningful baseball, it’s all we’ve got.

It’s something.

by Greg Prince on 4 October 2010 6:06 am Yo DJ, pump this party!

The song is called “I’m Gonna Get You,” a snappingly energetic dance number. I remember hearing it quite a bit on Z-100 in the summer of 1993 and enjoying it enough to purchase the 12-inch single. Very, very catchy. Listen to it for yourself here — if you’ve been attending Mets games since August of 2006, the intro should be at least passingly familiar to you.

Unless you mostly went this year, in which case you’ve almost never heard it.

The name of the artist? Bizarre Inc. And why would you hear Bizarre Inc. at a Mets home game? Because it’s the song to which Oliver Perez warms up.

Bizarre Inc. … perfect. Welcome and farewell to the 2010 Mets.

You want an incorporation of bizarre? Go to Closing Day, sit in the wind and the cold for fourteen innings, wait for the Mets to do something, to do anything. Then see them do the last anything you’ve been led to suspect they ever would: insert Oliver Perez into a tie game.

Yo DJ, pump this party!

Oliver Perez entered the field of play at the top of the fourteenth inning. He was greeted predictably by the 2,000 or so tortured souls who remained into the fifth hour of the 162nd game of the season. He was a boo magnet as he stepped on the mound. After loosening up to Bizarre Inc. (why waste your time? you know you’re gonna be mine! you know you’re gonna be mine!) — he pumped that party as only Oliver Perez could.

You might say he pumped vitality into Citi Field the way Silly String used to liven up parties. The Mets and the Nats for the first thirteen innings was the bore war, perfectly indicative of what a majority of the previous 161 games had been when the Mets were one of the participants. Here’s the game recap as best as I can remember it:

• Somewhere along the way Washington scored a run.

• Later, the Mets scored a run.

• At all other intervals nothing else happened, unless you count Jerry Manuel — the imminently erstwhile Chief Logistics Officer for Bizarre Inc. — pulling his two star players from the game in the top of the ninth while the game’s outcome remained completely in doubt. Neither David Wright nor Jose Reyes was retiring after Sunday, neither had broken a cherished record, neither was the Pope or anything like that. Yet Jerry treated his two best players as if they were Hank Aaron and Cal Ripken at an All-Star Game.

Earth to Jerry: The game counted. It was 1-1. We could have used our two best players to theoretically help win it. That would have been nice. Instead, it was six innings of Mike Hessman and Joaquin Arias — fine fellows, no doubt, but not David Wright and Jose Reyes in a 1-1 game. Not even close.

Maybe the Mets still would have flailed without success for several more innings and hours with Jose and David remaining active, but I’d prefer watching my team go down with its best as opposed to the pronounced opposite.

Which brings us back to Ollie.

Yo DJ, pump this party!

In case you’ve forgotten who Oliver Perez is, he was a lefthanded pitcher of eternal promise and modest success prior to 2009. Then he was paid a king’s ransom to potentially build upon his modest success. Instead, he pitched poorly and behaved worse. When given an opportunity to temporarily rehone his skills at an outpost where he couldn’t do anybody undue damage, he declined. His contract said he didn’t have to do anything he didn’t want. He didn’t want a week or two or three in Buffalo (where he would have continued to have received his ridiculous ransom).

So Jerry Manuel stopped using him altogether, which was the path of least resistance. Ollie took up roster space, appeared in baseball games once in a blue moon and facilitated the lighting up of scoreboards from Arizona to Atlanta to (almost) Astoria on those rare occasions when he was asked, pretty please, do you think you could earn a bit of your ransom and maybe not suck in the process?

Not who you’d trust with maintaining a 1-1 tie in the 14th inning of the 162nd baseball game of your season, a game that meant only as much as any game means if a playoff spot isn’t involved. It was a professional endeavor. People paid money to enter Citi Field Sunday, they paid money for food and drink and maybe bought a fleece sweater or something to stay warm. Beyond the tangible, people invest their souls in the success of their team. Success in the broadest 2010 sense was unavailable and success in the narrow Game 162 sense was unguaranteed. But somewhere in the fine print there must be a promise that both teams will really and truly try to win every contest in which they compete.

The Nationals tried to win. They didn’t remove David Wright and Jose Reyes from their lineup and they didn’t insert Oliver Perez as their pitcher. Wish I could say the same of the Mets.

Yo DJ, pump this party!

Ollie teased us. He struck out Ian Desmond to lead off the fourteenth. With one out, we dared to dream that maybe the 27-day layoff since Oliver Perez last pitched wouldn’t adversely impact him and maybe he could get through one lousy inning.

Instead, we just got the lousy inning.

• Ollie hits Adam Kennedy.

• Kennedy steals second.

• Ollie walks Roger Bernadina.

• Ollie walks Wil Nieves.

• Ollie walks Justin Maxwell.

In case you’re wondering, Adam Kennedy was a .249 hitter in 2010; Roger Bernadina, .246; Wil Nieves, .203; and Justin Maxwell, an exceedingly cool .144. Their respective OPSes, in case batting averages aren’t your thing, were .654; .691; .554; and .593. Those aren’t threatening OPSes — those are SAT scores.

Ollie flunked his exam. Thirty pitches, five batters, one out, one hit by pitch, one stolen base, three walks and the magic final run to grease the exits to the offseason. His sudden benefactor Manuel — somehow the only manager in the history of expanded rosters to be short of relievers at the end of a season — stepped out of the dugout to pull him. The crowd (if you wanted to call us that) greeted him predictably, too.

Then Pat Misch, eight-inning starter from Friday night, throws three pitches and elicits a ground ball double play.

Bizarre Inc. all around.

What a weird team, and it was never better exemplified by the confluence of the pitcher who never deserved to pitch winding up pitching and the manager who has managed to remain in his post through two of the creepiest, crappiest, cruddiest consecutive seasons any Mets team has ever put up. 2009 was a horror show. 2010 was the lamest of crime dramas. The most glaring crime was Oliver Perez stealing $12 million. The drama was wondering what the hell Jerry Manuel was thinking.

It was bad and bizarre at Citi Field Sunday. It was dullsville, mostly, but then it was insulting. Out go your best players, in comes your worst nightmare. Oliver Perez finished 2010 and hopefully his Met career with an 0-5 record, a 6.80 ERA and the distinction of making Kenny Rogers’s final Met appearance appear outstanding by comparison.

But give Ollie this: he did get us interested when he took the ball, interested enough to be loudly revolted. You might think a desultory 2-1 loss spread out over four hours, fourteen minutes and fourteen innings might lull you into a coma. It didn’t. The mere sight of Ollie woke us from the last of our stupor, even if our offense eventually left us sleeping with our eyes open.

And that was the highlight of Closing Day 2010. How bizarre.

***

Shortly after Ruben Tejada flied out to end this wilted campaign, a highlight video rolled on CitiVision. It was pretty non-descript. I generally don’t like using that word because it seems designed to save writers the trouble of describing things, but there was no theme to it, no arc to it, no distinct musical cues to inform it — there was just shot after shot of Met after Met not failing in a home uniform in 2010.

The highlight video used to be a staple of Closing Day and it could give a Mets fan chills: “Here’s To The Winners” in 1985; “Back In The High Life Again” in 1988; “Reach” in 1997. Those were uplifting regular seasons set to soaring soundtracks. We stood and we cheered and I swear we even cried a little when they were over. I haven’t seen the Mets produce a video of that nature at the end of a regular season in quite a while. I suppose their seasons of late have produced too many outtakes and not enough actual highlights.

Still, I’m conditioned to think a great one is coming after the last out, so I create one in my mind. I can see that 2010 highlight video and it’s riveting. The footage is all my own (which is good, as it saves me from having to pay MLB a licensing fee).

In my video, I see the people with whom I spent a season at Citi Field. I see the warmth, the consideration, the conviviality, the fun I experienced with them. I see high-fives and hugs and hear a lot of laughter. I am caught up in the dialogue of how we would make our team play better and make our park work better and, inevitably, when we’re gonna do this again because we had such a good time here, didn’t we? I’m gripped by our common Met bond and I am astounded by how much love a 79-83 ballclub can generate among its devotees.

I see the great days and nights a ballpark gives you when you’re with the kind of people you like so well and find yourself caring about so much. I see it clear to the end, straight through a final weekend that lasted 33 often interminable innings but somehow didn’t go on quite long enough.

It never does.

I thank all those people who appear in my personal 2010 highlight montage for having been an integral part of my Mets season, and for allowing me at least a cameo in theirs.

by Greg Prince on 3 October 2010 9:00 am Six years ago today, the Mets were proactively pulling the plug on one era in hopes of jump-starting the next one. At Shea Stadium on Sunday, October 3, 2004, the Mets were severing ties with their manager, inaugurating a new front office administration and putting the latest in a string of disappointing seasons to bed.

Beyond the finality of sending off Todd Zeile, kissing off John Franco, waving off the Montreal Expos and — with limited affection and maximum awkwardness — blowing off Art Howe, we were welcoming Omar Minaya home to Queens. The former assistant general manager of the New York Mets took over the top job at the very tail end of 2004 as the team he had been running was expiring. Montreal was moving to Washington and here in New York, there wasn’t a moment to waste. Omar had to commence general managing at once.

As Closing Days pitting fourth- and fifth-place teams go, the one from six years ago was genuinely transcendent. Zeile homered on the final major league pitch he ever saw; Franco, in relief of Heath Bell, popped up Ryan Church with final Met pitch he ever threw; Endy Chavez made the final out any Expo would ever make; Joe Hietpas made his first, last and only appearance as Zeile’s defensive replacement behind the plate in the bottom of the ninth…Zeile hadn’t started and departed a game as catcher in fourteen seasons, but he ended his career catching one-third of an inning from the all-time leader in saves by a left-handed pitcher. The last time Todd Zeile was legitimately a catcher was 1990, the first year John Franco was a Met closer.

Amid all that backglancing and foreshadowing, with Omar trotting in from the braintrust bullpen to take the ball from a struggling Jim Duquette, there was also the faint hum emanating from the sealed fate of Art Howe. He was as gone from the Mets as the Expos were from Montreal the moment Jeff Keppinger fielded Endy Chavez’s grounder to second and tossed it to Craig Brazell (filling in at first base for Mike Piazza). The Mets had enjoyed a surprisingly good stretch under Howe earlier in 2004 — 34-25 from May 1 through July 7, propelling them to within a game of first place — but their contender status proved fleeting. Nobody recalled the success by September. They only noticed the failure that had taken hold since.

Howe was fired before the season was over, but the Mets didn’t remove him from office for 17 more games, asking him to finish out the season despite his being the lamest of incapacitated ducks. Ownership took a typically clunky route to arrive at the correct ultimate decision, but either way, we knew for sure the next time we returned to Flushing to watch our team, somebody else would be managing it. Yet despite the finality in the air on Sunday, October 3, 2004, there was no acknowledgement of or reaction to the impending departure of Art Howe. Nothing on DiamondVision, nothing on the scoreboard, nothing from the stands.

Six years ago today, the Mets were doing what they’re about to do again. They’re even doing it while the team that used to be the Expos is in town.

This, then, is where we came in.

You could almost plot the path of the 2010 season on the same graph as 2004’s: there was an invigorating stretch of 39-24 baseball from April 19 through June 27; there was growing confidence or at least hope regarding the team’s ability to complete for a playoff spot; then there was a bottom that fell irrevocably out. In 2004, the Mets sputtered (16-22 from July 8 to August 21) until they simply went splat! (2-19 directly thereafter). The 2010 Mets’ extended moment of doom was a 7-17 sag between June 28 and July 25 that sucked all significant signs of life completely out of them. They’ve been sputtering ever since.