The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 13 April 2010 2:47 pm Say — or should I say hey — you know who was a really good baseball player? Willie Mays.

You probably knew that already, but you’ll really know it if you read Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend by James Hirsch. You’ll know a ton by the time you float through its 560 pages of text. You will, I’m certain, feel what Brad Hamilton meant in the “no shirt, no shoes, no dice” scene from Fast Times At Ridgemont High when he instructed Spicoli and his stoner buds, “Learn it. Know it. Live it.” Even if you’re fairly familiar with the Willie Mays story (as I was going into this book), you’ll likely be astonished by at least three iotas of information per chapter, stuff that transcends his 660 home runs, his 1,903 runs batted in, his 3,283 hits, his 2,062 runs, his two MVP awards, his 12 Gold Gloves and his 24 All-Star selections.

Willie Mays was the last of the big-time barnstormers.

Willie Mays positioned his teammates from center field.

Willie Mays tended to a bloodied John Roseboro after his own pitcher, Juan Marichal, took a bat to his head, thereby defusing one of modern baseball’s ugliest confrontations.

Willie Mays received multiple standing ovations from the Ebbets Field crowd in his last game before reporting to the army despite being the enemy.

Willie Mays cleared the basepaths for trail runners like he was a fullback, deking relay men and bowling over catchers in the process while the guy behind him inevitably moved up 90 feet.

Willie Mays’s respective last at-bats in the 1962 regulation season, pennant playoff and World Series produced crucial hits each time he swung.

Willie Mays played in 150 or more games in more consecutive seasons than anyone, including Cal Ripken.

Willie Mays gave a kid in San Francisco a ride to the ballpark simply because the kid rang his doorbell.

Willie Mays said “hey” a lot but never said “say hey,” except on a record.

America could hardly get enough of Willie Mays for 22 seasons. I couldn’t get enough of Willie Mays for 560 pages, though Hirsch gave me a lot. If Willie Mays is not the most incisive of personality studies, it is an absolute first-rate biography of a baseball career set against the backdrop of a couple of baseball and generational eras. It is highly recommended to any baseball fan who thinks being absorbed deep within one of the game’s golden legends constitutes the most delightful road trip possible.

Still, I’d like to get more Willie Mays, and I know where I’d like to get it. I’d like a generous helping at Citi Field, home of the last team for which Willie Mays played, situated in the city Willie Mays made his own when he first rounded first and took off for immortality. If Hirsch’s book makes anything implicitly clear, it’s that New York’s National League ballpark must commemorate the career of New York’s greatest National League ballplayer.

That’s not Hirsch’s stated agenda, but it is mine.

Citi Field is much improved in the history department in 2010. To that I say wonderful. The banners, the bricks, the museum…it’s as if they’ve opened Mets Stadium after a year spent killing time at a neutral site. Sincere applause from this heretofore critical corner for those efforts.

But more can always be done, and I’d like to start with something for Willie Mays at Citi Field. It’s not so much that Willie Mays deserves it. It’s that we deserve it.

“New York was home,” Hirsch writes of Mays’ attitude when word broke that Horace Stoneham was planning on moving the Giants to San Francisco. “Everything was familiar; the fans loved him. He didn’t particularly want to say good-bye to New York, and New York certainly didn’t ant to say good-bye to him.”

Willie Mays is our legacy. San Francisco — which was reluctant to accept an East Coast import as its own — celebrates him in retirement, but it was New York that embraced him from the moment he appeared on the horizon in 1951 and it was New York that welcomed him back when a historic wrong was righted in 1972. The feeling was mutual. Mays, upon his trade to the Mets:

“This is like coming back to paradise.”

It wasn’t overstatement given the depth of feeling Willie generated as a Giant between ’51 and ’57 and maintained as a visitor from ’62 onward. It wasn’t out of the norm when the St. Francis Monastery of Manhattan’s recorded telephone message — “Your Good Word for Today” was “New York has reason to rejoice these days. Willie Mays has returned. There is some heart in professional sports.”

Willie and Joan, two jewels in our crown. The heart wanted what the heart wanted, particularly Joan Payson’s heart. Mrs. Payson made Mays II happen. She was the minority Giants stakeholder who voted (through her bag man, M. Donald Grant) to keep the team, like its centerfielder, where it belonged, in New York. She was the Met owner who was happy to fund a new franchise in part because it meant Willie Mays would come around nine times a year. She tried to buy the Giants from Horace Stoneham. She tried to buy Willie Mays from Horace Stoneham. On May 11, 1972, she succeeded.

And on May 14, 1972, it paid dividends when Willie Mays adjusted headgear adorned with an NY for the first time since September 29, 1957 and hit what turned out to be a game-winning home run. He did it, strictly speaking, for New York, as in for the New York Mets. But he also did it, not so metaphorically, for New York as well.

We, as in New York, loved Willie Mays all along. The Giants fans of the early ’50s recognized immediately they’d been granted a gift from the gods when he came up from Minneapolis. The Dodger fans throughout the ’50s cheered his genius for the game they loved even if he played of the team they hated. In July 1961, nine months before the Mets existed, Yankee Stadium hosted an exhibition between the Yankees and the San Francisco Giants. The game didn’t count except in the hearts of “Giant-starved New Yorkers,” as Charles Einstein put it. More than 47,000 parishioners showed up, and “they rocked and tottered and shouted and stamped and sang. It was joy and love and welcome, and you never heard a cascade of sound quite like it.”

“New York,” Mays said later, “hadn’t forgotten me.”

New York would take every opportunity to remember Willie Mays when he began returning regularly in 1962 — “The center field turf at the Polo Grounds looks normal this weekend for the first time in almost five years,” wrote Arthur Daley in the Times upon San Francisco’s first trip in. Old Giants fans, old Dodgers fans and new Mets fans all embraced him. The Mets held a night for him in the Polo Grounds on May 3, 1963, when Bill Shea publicly asked, before an appreciative crowd, “We want to know, Mr. Stoneham, Horace Stoneham, president of the Giants — when are you going to give us back our Willie Mays?”

The answer was nine years later. Willie Mays’ homecoming was as storybook as it could get, No. 24 for the Mets homering against the Giants at Shea to win on Mother’s Day 1972. No mother was any happier than the big mama of the Mets, Joan Payson. It had been a decadelong quest of her to put Mays into A-Mays-in’. When the Mets were forming, Payson still owned 9 percent of the Giants, valued at $680,000, and she had to sell it. According to Hirsch, she offered it to Stoneham free and clear of financial compensation. All he had to give her, for her new ballclub, was his center fielder.

Willie Mays for 9 percent of the Giants…it would have been a steal for Payson, but Stoneham didn’t go for it. It took until ’72 to make the dream a reality. Of course Willie wasn’t the Willie he was in ’62 by then (which is why all it took was pitcher Charlie Williams and a reported sum in excess of $100,000, though Stoneham claimed he never took any of Payson’s money; he just wanted Willie to be “taken care of”). His superstar emeritus status, however, hadn’t diminished one bit, which is why Willie Mays becoming a New York Met was and remains one of the most mindblowing midseason trades in Mets history.

He played well, too. He was 41 years old yet helped the Mets reel off eleven consecutive wins that May, putting New York six games ahead of the field in the N.L. East. Murray Kempton described a sequence of events from May 18 in which Mays, having walked, confused Expo fielders into a flurry of bad throws that resulted in two runs, each “the unique possession of Willie Mays, who had hit nothing except one tipped foul.”

Eventually injuries took their toll on the roster and age slowed down an overworked Willie, yet Mays was no charity case in ’72. No Met put up a better on-base percentage and he was second on the club in batting average and slugging percentage. Plus he was Willie Mays. Wrote Jeff Greenfield at year’s end, “Willie Mays is reminding New York of our own best moments, and our own best hopes.”

The trade of Williams for Mays was no mere agate type transaction and this was no mere spare first baseman/outfielder. Willie Mays as a New York Met was, in every sense of the word, a big deal.

Hirsch explores 1973 as well as 1972, which was the proverbial double-edged sword of Mays’ Met tenure. On one hand, Mays could be prickly (to put it mildly) at this advanced stage of his career and a handful for Yogi Berra, who didn’t particularly crave having him around at the owner’s behest. Willie hit .211, which reads like blasphemy. On the other hand, he was Willie Mays, he knew more about baseball than anybody around, and he shared with grateful teammates. Tom Seaver told Hirsch Mays conferred with him on where he wanted him playing depending on who was batting and how he’d be pitching to him — and that no other position player ever did that.

Willie Mays’ final Met season might have gone down as a footnote to his 1972 return, except the 1973 Mets were destined to live on in memory. The Mets gave him a night at Shea, September 25 in honor of his impending retirement. A sellout crowd developed something in its eye for a very long time, no more so than when Willie gave his valedictory:

I see these kids over here, and I see how these kids are fighting for themselves, and to me it says one thing: Willie, say good-bye to America.

With that, Shea erupted and the Mets fought for their pennant. They got the divisional half of it within the week. With Willie taking a very mighty swing in Game Five of the NLCS against the Reds, delivering a key run and scoring another, they secured the rest. Proper editing would make that the last scene of Willie Mays’ career, but the World Series he played a role in securing would result in some pretty gory bonus footage. He played center, the sun field, in Oakland and he was no kid, Say Hey or otherwise, out there. Mays fell down, balls fell in and a simpleminded summation was born. Whenever a great athlete started showing his age, it became easy enough to write him off with, “What a shame it is when a star hangs on too long. Look at Willie Mays in the 1973 World Series.”

Yes, look at Willie Mays in the 1973 World Series. Look at who drove in the eventual go-ahead run in Game Two: Willie Mays. Look at who capped off a 22-year career the way he began it, as the center fielder for a miraculous New York National League pennant winner. Look at an all-time great who gave millions the thrill of being on their team even if he was at the end of the line.

Mays and the Mets were supposed to ride off into the sunset together after 1973. Willie maintained a coaching position in retirement, but his responsibilities were ill-defined and once Mrs. Payson was out of the picture, good old M. Donald Grant began spitefully insisting tabs be kept on Willie’s comings and goings. Mays outlasted Grant, however, and when Willie was voted into the Hall of Fame in 1979, he was supported by a Met contingent in Cooperstown.

Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, as was his habit throughout the ’70s, stepped in to ruin things. Willie had taken a rather ceremonial job with Bally’s of Atlantic City, mainly playing golf with high rollers. Kuhn ordered Mays to quit at once or lose his coaching job. Willie needed the Bally’s gig, so he stepped away from baseball. Nevertheless, the new Doubleday-led ownership group continued to have Willie back for Old Timers Days in the early ’80s, and Mays was always introduced last at Shea, always garnering the biggest hand.

Then, as was the case in 1957, he disappeared to the West Coast. The San Francisco Giants got around to retiring his number in 1983 and brought him back into their fold once Bowie Kuhn’s successor, Peter Ueberroth, lifted the nonsensical ban on Mays (and Mickey Mantle). Peter Magowan, who saved the Giants for San Francisco when they were nearly moved to St. Petersburg, gave Willie Mays a lifetime contract to serve as Willie Mays…as if there could be a higher calling.

The Mets-Mays connection has been understated over the past 25 years. He has returned to where he finished up twice that I can recall, in July 2000 when the Mets commemorated their 10 Greatest Moments (Willie was given a discrete introduction as part of the ’73 Mets) and when they Shea’d Goodbye in 2008. Willie, in a Mets batting practice cap, came out third-from-last, just after Darryl and Doc, just before Mike and Tom. He was received enthusiastically both times. In St. Lucie, there are three thoroughfares named for Met legends: Tom Seaver Curve, Gil Hodges Road and Willie Mays Drive. In Mets Plaza, if you come down the back stairs from the 7 train, the first two player banners on the first lamp post you encounter portray Bobby Ojeda and Willie Mays. In the montage of images that fill the Mets Hall of Fame, there’s one very nice one of Willie Mays chatting with Joan Payson. His 1973 Topps card has been spotted on the Field Level alongside Jerry Koosman’s, Bud Harrelson’s and those of other beloved Mets.

And of course No. 24 almost never makes it out of mothballs. Kelvin Torve famously wore it for a few minutes in 1990 until an outcry ensued and Rickey Henderson, not too shabby a player himself, donned it as a player and coach.

I’m not going to advocate here for the retirement of Willie Mays’s number by the Mets. Oh, I think it should have happened years ago, and that if Lindsey Nelson had announced on Willie Mays Night in 1973 that no Met would ever wear it again, New York would have nodded and roared. But given how emotional the issue of number retirement is, particularly among this notoriously insecure fanbase (What about Mike? What about Keith? We can’t multitask!), I don’t see it happening. The vague non-retirement retirement of Willie Mays’ number carries its own cachet at this point anyway.

I am, however, here to advocate for something to be done to honor Willie Mays at Citi Field. A real honor, not just an incidental “he played here, too” type of thing. There’s no shame in sharing a lamp post with Bobby Ojeda, but the Willie Mays who electrified New York in the 1950s, glowed on every occasion here in the 1960s and absolutely lit up the Metropolis’s face in the 1970s deserves something more.

Bobby gets to spend lots of time with Willie. Give us a day when we can hang out with the Say Hey Kid. We who love and appreciate the breadth and depth of New York National League baseball deserve something more.

I have a few ideas.

The Say Hey Concourse. Center field was Willie’s address at the Polo Grounds and Shea Stadium. Let’s rename the area behind center at Citi for the man who defined it. All you need is a sign, a few pictures from ’51 to ’57 and ’72 to ’73 and you’d have a marvelous bracket to complement the Jackie Robinson Rotunda. The great Dodger at one entrance, the great Giant/Met at another. The tradition of New York National League baseball spoken loud clear from front to back. Talk about strength up the middle. And if you’ve ever stood out there and tried to have a conversation while music is blasting and burgers are cooking, you know you pretty much have to say “HEY!” to have any kind of conversation.

The Catch Installation. As you can read in detail here, artist Thom Ross created an incredible five-piece monument to one of the greatest catches in New York postseason history (right up there with Endy in left and Rocky in right) and it needs a permanent home. What better place than where National League baseball continues to be played in New York? Given the dimensions of the Citi Field outfield, what better statement to make than honoring on our premises The Catch Willie Mays made in a park — the one where the Mets were born — a mere Triborough Bridge away? The San Francisco Giants are having a Catch bobblehead day this year. Let’s do them four better and show that The Catch was no kitsch.

(And while we’re at it, let’s restore the Tommie Agee home run marker high above left field. Like Mays’ 1954 run, catch and throw off Vic Wertz, the only fair shot to the Upper Deck at Shea deserves to live on even if its environs were torn down.)

Willie Mays Day. The Mets gave him a night in the Polo Grounds. The Mets gave him a night at Shea Stadium. Let’s complete the trifecta. Let’s have a day for him next month, the afternoon of May 9, three days after Willie Mays turns 79. Why then? It’s the Giants at Mets, and it’s Mother’s Day. What an opportunity to recall both Mays and Mrs. Payson. There’s no other promotion scheduled, so let’s do it. Let’s reach out ASAP to the Mays camp. Make a contribution to the Say Hey Foundation, Willie’s cause for kids. Promote the book (an authorized biography) on the scoreboard that weekend. Make this happen. The Mets have really elevated their historical game in Citi Field’s second season. Take it higher. Bring in the greatest ballplayer most people who saw Willie Mays will swear they ever saw.

In 1999, the Mets held a night for Hank Aaron, who played against the Mets. They held a night for Ted Williams, who retired before the Mets ever played. There was no good reason for either but they were both lovely gestures in the spirit of love for baseball. Ralph Kiner got a night three years ago for no other specific occasion than it was an excellent idea to pay tribute to Ralph Kiner. The timing of Willie Mays Day to coincide with Mother’s Day and the Giants coming is helpful, as is the release of the book, but there’s no reason needed to do this beyond he’s Willie Mays, he defined New York baseball and he was and is one of ours.

Willie Mays said “hey” to this city nearly sixty years ago and to this franchise almost forty years ago. Let’s say it back one more time.

by Jason Fry on 12 April 2010 8:00 am On Saturday Emily and I were watching the game upstairs with my visiting parents, while Joshua was downstairs looking at the TV in our bedroom. (I don’t remember why this came about — he wasn’t being punished or anything. Unless you count watching the Mets as punishment, which right now I’d have trouble disputing.)

So Rod Barajas smacks his liner to left, Willie Harris dives for it, and Willie Harris being Willie Harris, it winds up nestled safely in his glove. We all groan, and I let a couple of obscenities fly. For obscure reasons involving this digital thingamabob and that digital doohickey, the downstairs TV is a couple of seconds behind the upstairs one. As shock and anger give way to grumpiness, we hear a little moan from downstairs. A minute later Emily finds Joshua lying on our bed completely still, head mashed into the covers.

Yeah, it was that kind of loss.

When the kid came upstairs, I asked him if he remembered the first time he saw Willie Harris in a game. He shook his head, and I reminded him: You were four years old. You and I went to Shea. It was really hot. The Mets fell behind against the Braves and came almost all the way back in the ninth, and Carlos Delgado hit one over the fence — and one of the Braves caught it.

“I remember that!” he chirped.

“You know who that Brave was?” I asked. “It was Willie Harris.”

When my kid is really interested in something he kind of looks at you for a moment and then gets quiet and stays that way. So it was on Saturday. I could see the wheels spinning around in there: Willie Harris isn’t a Brave anymore but a National and Carlos Delgado is gone and I’m a lot older but Willie Harris is still killing us. (I didn’t even tell him about Ryan Church.)

Fast-forward a day, and Emily and I are glumly watching the Mets finish mailing it in against that tomato can Livan Hernandez and the Zimmerman-less Nats. K-Rod nails Harris in the elbow and we watch the vaguely amusing, vaguely embarrassing semi-near-brawl — until Joshua realizes who the batter is and starts howling for blood. The kid is screaming at him for sticking his elbow in, for not getting out of the way, for saying mean things to K-Rod … basically, for being Willie Harris.

We hope our shared fandom will bring our children joy, and sometimes it does. But in making our kids into fans we’re also asking them to stick their innocent fingers into emotional light sockets over and over again. We’re signing them up for 60 days of disappointment a year even when things go swimmingly. It’s really kind of sick — sick to put our children through it, and sick to be not so secretly proud when they arrive at each new station of the fandom cross.

My kid now has his first Spike Owen, his debut Robby Thompson, his initial Brian Jordan. And he’ll never forget him. He’ll be in his late twenties and notice Willie Harris is the Diamondbacks’ third-base coach and his significant other will be left to wonder why the sight of some old coach pulling on one ear has provoked her beloved to spluttering rage. And then he’ll text me and maybe I’ll apologize for having done this to him. Though it’s more likely that I’ll laugh, and we’ll both hope that some Diamondback smashes a hard liner that catches Willie Harris in the seat of the pants. And then does so again.

by Greg Prince on 11 April 2010 7:13 pm I wonder how many Ollie Perez starts Johan Santana would have to make to have me look at him in anything but awe. Even after he gave up five runs in five innings Sunday, when I saw him giving postgame interviews, all I could think was, “There’s the man who threw a three-hit shutout on three days’ rest with everything on the line the second-to-last day of 2008.” And I reflexively swooned.

We Mets fans might hold grudges, but we also cling to goodwill for quite a long time if given anything at all to which to cling. Of course Johan has given us some very nice days since 9/27/08, including last Monday, so his benefit of the doubt is heftier than anybody else’s on the team. He might give up another grand slam like the one he gave up to Josh Willingham en route to an inarguably dispiriting defeat, but I’ll never give up the image of him being The Man against the Marlins when it counted most.

The rest of this team has a shorter leash. Jeff Francoeur is surely lengthening his — what an arm, and what a lousy 90 feet of baserunning from Adam Dunn in the third; Mike Jacobs finally earned a link in the chain for the first time in almost five years (he always did hit well at home in losses to the Nationals on Sundays); and never let it be said Raul Valdes has ever done anything wrong in a Mets uniform, but overall this was a cheerless game at the end of an erratic homestand, to put it kindly.

Baseball being baseball, the 2-4 Mets are not far removed from being the 4-2 Mets. Tatis is a little quicker or shrewder Wednesday night, and that’s a win. Barajas is schooled in the dangers of hitting it to Harris Saturday, and that’s a win. If that’s the case, we’re talking about a team that either clubs teams to death (as the Mets did Monday and Friday) or one that never says die and finds ways to win.

Sadly, they didn’t find ways to win the games they lost and they have died four times, if indeed a team can be said to have encountered death after six games. By the one-third measurement discussed here recently, the Mets have won one game they were going to win (Opening Day), lost two games they were going to lose (today and Thursday, because how are you supposed to touch the likes of Livàn Hernandez and Burke Badenhop?) and are 1-2 in those games that determine your season, slotting the Pelfrey game, which was 2-2 entering the seventh, in this category. It’s an inexact science, but based on what we’ve watched, 1-2-1-2 reads about right.

There are some encouraging signs around this team. Jeff Francoeur is a six-game superstar to date, and that’s on top of his solid second half last year. Rod Barajas has demonstrated a pulse, a bat and a presence behind the plate. The unknown quantities comprising the bulk of the bullpen — Igarashi, Takahashi, Nieve, Mejia and now Valdes — have acquitted themselves mostly well. Frankie Rodriguez saw fit through those awesome goggles to answer Willie Harris’s yapping (if he wanted to hit you, he would have found your back, not your inside elbow) and I only wish the minor kerfuffle that ensued would have found heretofore yappy Brian Bruney taking one from K-Rod. A few other Mets have played fine to dandy for moments or stretches, and that is fine as well as dandy.

On the other hand, whatever the starting pitching occasionally has going for it, length has not been among its attributes. No starter has seen the seventh from the mound. One can accept that the first time through the rotation if one isn’t too demanding, but now we go to Coors Field, where bullpens tend to get leaned on, and Busch Stadium, where Mt. Pujols looms in the distance. Our lineup in any given deficit situation has been a disheartening exercise in anticipation. Depending on the daily configuration — which is to say whether Francoeur is batting fifth or sixth — you take a deep breath and hope something happens with the batters who are best described as “…and the rest” à la the Professor and Mary Ann before the Professor and Mary Ann earned their own ID in the The Ballad of Gilligan’s Isle.

Best news? Six goes into 162 27 times. The first 1/27th of the schedule has not been optimal. Yet it’s the last 26/27ths where the stories of seasons are told.

by Greg Prince on 10 April 2010 10:27 pm You can’t take the numbers you see after five games terribly seriously. Do we really think Jeff Francoeur will hold to an on-base percentage of .500? That Ollie Perez will be hitting .500 all year? That Jose Reyes will be fielding .875 when all is said and done?

On the other hand, it would be hard, based on recent precedent, to bet against Ollie’s 6.35 ERA being the norm. From the looks of him, I can’t imagine Frank Catalanotto raising his batting average from .000 to any higher than .001. And then there’s the performance that doesn’t show up in the boxscore, that of the Mets fans.

Are we going to be a bunch of bumps on logs from now to October 3? I sure hope not. I’d like to think not. But honestly, I don’t know.

I was hoping to come home Saturday afternoon not just celebrating a Mets win (thwarted on that count) but also elevated by being At The Mets Game on a big day, when Jose Reyes returned. This was no mere undisabling. It was a month ago tomorrow that we received the news of the thyroid setback. Jose, it was said, would be restrained from “baseball activity” for two to eight weeks. Turned out to be not quite two, and it took only eighteen days between that all-clear coming down and Jose Reyes, once again, batting leadoff and playing shortstop for the New York Mets.

His first appearances were greeted warmly. I had hoped they’d be greeted hotly. It shouldn’t have been chilly at Citi Field this afternoon. It should have been downright Dominican out there. But Jose brings enough heat on his own. Nevertheless, we met him in lukewarm fashion: a nice hand when the lineups were read, a semi-standing O when he came to bat the first time. Jose drained the drama a bit by swinging overanxiously and not getting hits.

But then, in the ninth, it was perfect. Jose’s the leadoff hitter. There’s nobody you’d rather have up when you’re down by one and you wanna be starting something. Sure enough, the prodigal sparkplug singles.

Jose’s on first and we…what? At first, nothing much. A few of us Jose!‘d, but not en masse. Perhaps everybody was spent from that wave they were doing in the top of the ninth when their 20-year-old phenom reliever Jenrry Mejia was mowing down the opposition on nine pitches, keeping us viable for the bottom of the inning. Or perhaps they were tired from taking pictures of each other against the appealing backdrop of a major league baseball game in progress. Or it could be that nothing any Met was doing could be as interesting as comparing scores from the Masters, as the fellas in front of me in Section 508 were doing when not drinking beer.

Then DiamondVision interrupted and ran a graphic in which the screen was filled with Jose!s. That cue, along with the traditional Jose! music, got the crowd going briefly. Then the music stopped and the DiamondVision showed Alex Cora’s face and it was back to nothing.

What, we can’t cheer unless we are electronically cajoled? Really? We, Mets fans, need that?

The rest of the ninth-inning rally progressed the same way. If DiamondVision suggested a LET’S GO METS! then the suggestion would be followed. When the suggestion was over, so was the enthusiasm, as if most Mets fans have no idea that it’s OK to keep yelling without specific provocation. Despite Reyes being moved to second on Cora’s sac bunt; despite David Wright walking; despite Jeff Francoeur walking; and despite this being a one-run game against a closer with no known well of ice water in his veins, most of the crowd could not bring itself to sustain a cheer for more than a few choreographed seconds.

Oh, and it was Scarf Day. The scarves were nice. They came in handy against the cold and the wind, but it was warm enough by the ninth to take them off and twirl them. Imagine a sea of blue and orange stripes getting Matt Capps’ attention, or maybe even Willie Harris’s.

You must imagine Mets fans making noise and distracting opponents because if DiamondVision didn’t actively tell them to do it, they didn’t. It’s probably absurd to believe that was the difference between winning and losing, but it was the difference between feeling people who go to Mets game have a stake in what happens down on the field and noticing how distant everybody seems from the action in this intimate ballpark. In a season when we’ve been accommodated with a fantastic museum and all kinds of extraordinary nods to team history (the P.A. played two Jane Jarvis recordings before the game!), the oldest tradition in the Met books, that of proactively urging the players on, seems to be dangerously close to extinct.

It’s sad. It really is.

Don’t mistake this for Mets fans being polite. We’re not polite, as Ollie Perez could tell you every time he went to ball two, but we’re not properly engaged either. We’re not being the Mets fans we’ve always been. We’re not generating Let’s Go Mets! without a video nudge; we’re not seeking soft spots in the other team’s psyche; we’re not exuding anxiousness over the outcome like nothing else matters for those few minutes when the final score is definitively in doubt. The acoustics at Citi Field are such that I pick up on far more conversations than I care to, and I hear everything being talked about except baseball. It’s a free country, but it’s not a free ticket, so why would you come to a baseball game to be immersed in anything but? The only guy I heard who seemed into what the Mets were doing was a coot a few rows back whose gems included:

• A singsong chant for “ROO BIN TEH HADA!” when Reyes batted because, well, Reyes wasn’t perfect and Tejada wasn’t there.

• A cursing out of Reyes for making a poor play on an Adam Dunn grounder, oblivious to the fact that it was Wright who didn’t handle the ball per the overshift employed against Dunn.

• A loud declaration that “HE’S ANOTHER ROBERTO ALOMAR!” after Jason Bay struck out in the ninth.

Citi Field has never been a better place to visit, yet those who visit it aren’t living up to the ballpark’s early-season standard-setting. Get up and walk around and chat and do whatever the hell you want, but if you’re in your seats in the ninth inning and your team (as indicated by your garb) is loading the bases and attempting to tie, then how can you not be heart and soul into what’s going on?

I really don’t understand it. This isn’t an entirely new revelation for me; it’s been coming for a few years, dating back to Shea’s overreliance on its automated cheerleading, but not in the ninth, not when the tying run’s on third and the winning run’s on second. Maybe there’s an element of “Won’t Get Fooled Again” to the mass reticence after the disappointments of recent seasons, but you’re already in the ballpark and the Mets are alive and kicking. They’ve survived the bare adequacy of Oliver Perez, they’ve persevered through Willy Taveras and Tyler Clippard (which, FYI, was a great ventriloquism act in the ’70s) and they don’t know yet — all previously compiled evidence notwithstanding — what Willie Harris’s glove is going to do to Rod Barajas’s sinking two-out liner.

So how come these people can’t roar for their team without a gigantic television screen telling them to?

by Greg Prince on 10 April 2010 9:30 am “I don’t know what it is about your face,” Rob Riggle as Randy the corporate douchebag enforcer tells Brennan (Will Ferrell) in Step Brothers, “but I just wanna deliver one of these right in your suck hole.” One of these refers to a fist Randy has made. Brennan asks if there’s anything he can do to change Randy’s opinion.

No, Randy says, even as he acknowledges “we’re all having a great time, having fun,” at the Catalina Wine Mixer Brennan has organized against all odds. It has nothing to do with the job he’s doing.

“It’s your face.”

“All I can do,” Brennan replies in his best professional manner, “is take that in, consider it, and I’ll just do my best version of whatever that would be.”

“I don’t even hear you,” Randy says. “You’re face is driving me nuts.”

Will he even last two innings? He lasted six! At the risk of being a corporate douchebag enforcer, this, I’m afraid, is my default visceral reaction to Mike Pelfrey. He seems like such a nice guy — almost too endearing for someone who tries to throw a baseball hard and repeatedly every five days — and Ron Darling keeps insisting he’s an incredibly talented pitcher, but damn it, there’s something…I’d have to call it goofy about him that keeps me from believing Mike Pelfrey can ever mix his own pitches consistently and successfully.

For the uninitiated, the Catalina Wine Mixer is the biggest helicopter-leasing event in the Western Hemisphere. It’s where you make your nut, it’s where you run with the bulls, it’s…it’s not just the Catalina Wine Mixer. It’s the Fuckin’ Catalina Wine Mixer. In the realm of Step Brothers, it means more than pitching against the Washington Nationals, but Mike Pelfrey, bless his goofy face and heart, had to start cashing checks and snapping necks somewhere in 2010. The Nationals would be the first challenge.

I didn’t think he had it in him, not in the second inning when a leadoff walk to Adam Dunn developed into a two-run triple from the eighth-place hitter Ian Desmond. I thought we were drifting even further from Catalina when Pelfrey stuck out his pitching hand in the third to flag down a bouncer from Nyjer Morgan. That was a Big Goof move right there, akin to his 2009 epidemic of falling down on the mound. Hell, it’s only the hand with which he makes one of these — a living.

Mike may drive me Pelfrey, but I want the best for him and us, so I held my breath and my visceral mistrust of his makeup and watched him try a warmup pitch. He survived the barehanded contact (two walks notwithstanding) in the third. He put a couple more baserunners on in the fourth, but survived that, too. He got several unlikely assists from his infielders as the night progressed — had to love Pelf galloping alongside Wright on that overshift, windblown popup in case David needed company — and, after six innings, Mike Pelfrey was, per Randy’s assessment of Brennan, nailing it.

Oh, runners got on and Pelf’s cap kept falling off, but he managed to stay on his two feet and not give up any more than those two runs from the second. There was some talk that at a relatively efficient 94 pitches he could have stayed in for the seventh, but soon enough, we had Francoeur and Barajas going “Pow! POW!” while Wright hit one that was tall enough to clear most walls, but not the Pelfrey-sized one in left, and besides, Fernando Nieve had to pitch again. Fernando Nieve has to pitch every day. He’s Jerry’s new toy. Watch out Perpetual Pedro, here comes Nonstop Nieve.

By the end of Step Brothers, Brennan has nailed it so effectively, that all Randy the corporate douchebag enforcer can do is shed tears of ecstasy. I haven’t gone that far in response to Mike Pelfrey’s admirable first outing of the season, but when I saw his goofy face in the clubhouse afterwards, the only one of these I felt moved to give him was a hearty handshake.

But only if he promised to use his glove hand.

by Greg Prince on 9 April 2010 3:29 pm Welcome to Flashback Friday: Take Me Out to 34 Ballparks, a celebration, critique and countdown of every major league ballpark one baseball fan has been fortunate enough to visit in a lifetime of going to ballgames.

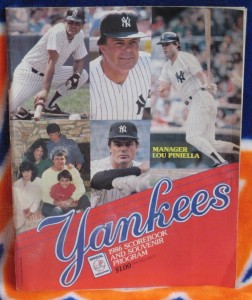

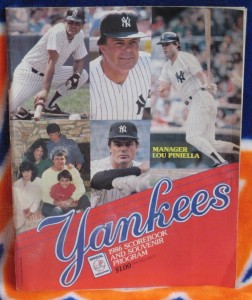

BALLPARK: Yankee Stadium (Renovated)

HOME TEAM: New York Yankees

VISITS: 5

FIRST VISITED: May 26, 1986

CHRONOLOGY: 3rd of 34

RANKING: 29th of 34

Long before Joe Torre discovered the joys of Bigelow, I realized Yankee Stadium wasn’t my cup of tea. I didn’t care for the team in residence and I didn’t care for its patrons, so why would I find the structure itself terribly appealing?

I try to give every ballpark a fair hearing on its own merits before bringing my own biases to bear. Just because I don’t like a ballclub doesn’t necessarily mean I won’t or don’t like its ballpark. Quite the contrary, as you’ll see as we move up the countdown. I’ll even refer to a Yankee legend, Mel Allen, as regards this school of thought vis-à-vis the way he broadcast ballgames: he said he was “partisan,” but not “prejudicial”. Thus, if I had thought the Yankee Stadium that stood from 1976 to 2008 was a wonderful place to experience baseball, even if it was Yankee baseball, I’d tell you it was so.

Instead, I will tell you it was not. Not for me, at any rate. I would have been happy to have found otherwise. Each trip to what the late Art Rust, Jr. referred to as the Big Ball Orchard in the South Bronx was a time-consuming journey. For the hours I’d spend coming, watching and going, I’d prefer to have felt enhanced. Yet my soul always arrived home a bit diminished.

My first time at Yankee Stadium was the only one I remotely enjoyed, probably because the Yankees lost. It was the only time I bought a ticket, the other four having been freebies, usually connected to business and, I must say, with pretty good seats on all occasions. In those later games (1992, 1998, 2000, 2003), I carried less and less enthusiasm to the adventure. From ’98 on, the MFYs were either dynastic or thought they were, so the overbearing factor was off the charts. It just wasn’t where I wanted to be, even though technically I prefer being near baseball to anything else at all times.

A few kind things to say so this doesn’t just become standard-issue Yankee-bashing.

• The shape was fascinating. During my 1998 visit, I got up midgame to wander, which wasn’t the easiest thing to do on a Yankee Stadium concourse. I wound up in one of the escalator towers that was used as a smokers’ depository. Inhaling wasn’t enjoyable, but I got a good look at how Death Valley stretched out — or at least how center was carved far and wide in relation to the rest of the outfield. It may not have been as endless as it had been in days of DiMaggio, but it was distinctive.

• The proximity to water was intriguing. Shea was the one whipped by a wind blowing off a bay, and Pac Bell would make much of splashdown hits, but the Harlem River flowed only blocks from Yankee Stadium. When I’d see the tableau from a train or car, I liked the effect. I don’t know that it made any impact on the games themselves.

• It wasn’t in New Jersey, no matter how much I wish I could gain a restraining order to keep the Yankees at least five states away from me at all times. The football Giants moved to the Meadowlands from the Bronx in the 1970s and it was no sure thing the Yankees wouldn’t follow suit. They didn’t. That’s only a good thing in terms of not giving up on New York City when it seemed the thing to do. I don’t know whether the continued presence of the Yankees did anything tangible for their neighborhood, but try to imagine any professional sports franchise deciding the Bronx was the place to be. Maybe in 1923, but you weren’t going to get another team there had the Yankees left. Score one for Urban America, at least 81 times per year.

None of this speaks to enjoying going to a game there, because I mostly didn’t. Again, Yankees and Yankees fans — not my thing. Monument Park wasn’t my thing, though it was probably ruined for me by a professional colleague who kept barking during our tour, “Who would the Mets have in one of these, huh? John Stearns? Mookie Wilson?” Sounded good to me. Roll calls and synchronized chants and narrow corridors…no thanks, Yanks.

I would have liked to have seen the real Yankee Stadium, the one that existed in full for a half-century. I only saw that one on Channel 11, and then only if the Mets weren’t playing (and even then in short doses and with distaste — distaste for Jerry Kenney, Rich McKinney and Celerino Sanchez…I was capable of hating Yankee third basemen well before Alex Rodriguez was born). That place was legitimately historic. The place I got to visit I never bought as the same one. I’d looked at too many pictures of the original to think the renovated version was anything but a knockoff. Granted, the ’76 iteration hosted its own history over 33 seasons, but I never had the sense I was in the house that anyone but John Lindsay built. The Yankees may not have moved to the Meadowlands, but their refashioned building, escalator banks and all, reminded me more of Giants Stadium (also class of ’76) than a pure idyllic ballpark.

For anyone who wasn’t buying in to the myth in advance, it wasn’t an alluring proposition. It combined 1920s efficiency with 1970s charm. It was renovated Yankee Stadium.

***

But, as mentioned, I did have a semi-decent time there the first time, which I why (along with that distinctive shape) I’ve garnered the goodwill to not automatically rank renovated Yankee Stadium the last baseball place on earth I’d ever want to be. Two years ago, when they were playing their final baseball games there — same season as Shea, which was the only one I really noticed — a very nice fellow with a really good Yankees blog asked me to contribute “a classic hater perspective” to a series he called Lasting Yankee Stadium Memories. (Not to be confused with Lastings’ Yankee Stadium memories, as Mr. Milledge never played there.) Because of my regard for Alex Belth and Bronx Banter, I behaved myself and wrote about that first time, when I wasn’t so much hateful as curious.

An excerpt follows…

***

On Memorial Day 1986, I got a call from my friend Larry who used to be a Yankees fan before withdrawing from baseball altogether; he wasn’t really much of a sports fan in the first place, but the trade of Sparky Lyle to Texas drove him away for good. Anyway, he had been talking to another friend of ours, Adam, a genuine Yankees fan. There was nothing going on for either of them that day and they thought it might be fun to drive up to the Bronx from where we all lived on Long Island and see a game. They wanted to know if I wanted to go.

What a strange idea, I thought. I’d always held to a principled stand of never setting foot inside Yankee Stadium or anywhere the Yankees were playing. I refused to go on a day camp field trip in 1975 to Shea Stadium because it was for a Yankees game. At twelve years old, I was highly principled.

At 23, I was a little less so. I had nothing going on that Monday in 1986 either, which is to say the Mets weren’t playing. I didn’t feel I was being disloyal by using the off day to see another baseball game. It wasn’t like I was going to root for the home team.

When I discovered baseball in 1969, I discovered it as a Mets fan. They became everything to me instantly. I found out New York had another baseball team, too, but I didn’t understand why. I never understood why anybody who was a New Yorker would ever need another baseball team besides the Mets let alone instead of the Mets. I’ve never lost that six-year-old’s sense of bafflement. First, in ‘69, I ignored the Yankees, which wasn’t hard. Then as they occasionally won their share of games and attention, I resented their existence. By the late ’70s, with the Mets going to seed and too many Mets fans in my junior high switching allegiances to the championship Yankees as if exchanging Keds All-Sports for Puma Clydes, my resentment flowered to full-on hatred.

Actually, it was probably hatred back at resentment, but I’m trying to maintain a sense of proportion about this.

Yet I did harbor a vague long-range goal of seeing every ballpark someday; Yankee Stadium was the one second-closest to my house and here was Larry offering to drive, and the Mets weren’t playing anyway…sure, I said. Let’s go.

Walking into Yankee Stadium for me was like walking into the Republican Convention. I’ve never walked into the Republican Convention, but as a lifelong Democrat, I can only imagine. It was just different. There was a team called “New York,” but it wasn’t the Mets.

Shocking.

I’d heard for years that you didn’t want to go anywhere near Yankee Stadium, you were taking your life into your hands. True, I wasn’t used to walking by a House of Detention before a baseball game as I did in the Bronx, but it didn’t seem like that big a deal. The area right outside the ticket windows struck me as rather pleasant, nicely paved, good landscaping. It all seemed newer than Shea. Every contemporary list of ballparks by age I had seen listed Yankee Stadium between Royals Stadium (1973) and Olympic Stadium (1977). It never occurred to me that this was the same Yankee Stadium from 1923. Such a big deal had been made in 1976 about the “new” Yankee Stadium, I assumed everybody was on board with the chronology.

We bought three very good field boxes behind first base no more than a half-hour before first pitch. I was surprised they were available. At Shea in 1986, you couldn’t get those seats. We were three of a little more than 30,000 in attendance on Memorial Day at Yankee Stadium. I was a little surprised there weren’t more people.

Yankee Stadium, from the inside, didn’t seem all that imposing. I’d read about how big it was. It didn’t seem that big. It felt very scaled down. Must have lost something in the renovation, I figured. I’d seen it enough on television so that it was more like walking onto a set than into a stadium. It definitely felt newer than Shea. It should have; it was a dozen years younger.

I bought two items at the concessions. One was an Angels cap. It was kind of a jerk move, but the Yankees were playing the Angels and I was instantly an Angels fan for the day. The girl who sold it to me at the souvenir counter couldn’t have been nicer. I think I was a mite disappointed I wasn’t growled at.

The other item was a program, two elements of which stood out.

1) An article by a fan who caught a foul ball off the bat of Tony Kubek in 1963. He exulted that “I was no longer a mere participant in the present. Kubek played with Mantle who had played beside DiMaggio who had played with Selkirk who had played with and had taken over right field from Babe.” Circle of life and the chain shall be unbroken and all that, but isn’t enough that ya caught a ball from Tony Kubek?

2) The Yankee roster listed, among others, No. 12 Hassey, Ron; No. 29 Shirley, Bob; and No. 3 Ruth, Babe.

The Yankees were so full of themselves that they listed EVERY RETIRED NUMBER in their scorecard as part of their roster. Hence, if Mattingly, Don needed a day off, manager Lou Piniella (who had replaced Billy Martin who had replaced Yogi Berra who had replaced Billy Martin who had replaced Clyde King who had replaced Gene Michael who had replaced Bob Lemon who had replaced Gene Michael who had played with Mantle who had played beside DiMaggio…) could always insert Gehrig, Lou in his place. DiMaggio was listed. Howard, Dickey, Rizzuto — what a bench!

Since there wasn’t much sizzle in the way of recent success to sell — and the most hyped prospects in an article on minor leaguers included future superstars Mike Christopher, Troy Evers, Bill Fulton and Steve George — the 1986 Yankees program reminded the reader again and again (and again and again) just how great the team used to be. Those pants your 1986 Yankees wear? They’re part of the “same uniforms” their predecessors put on, presumably one leg at a time. We were invited to learn more about those on-hiatus ghosts at Memorial (not Monument) Park, “a smorgasbord of Yankee tradition”.

Only the Yankees could hype a veritable mausoleum like it was an all-you-can-eat buffet.

It wasn’t like the 1986 Yankees were bad. They had Mattingly, Henderson and Winfield, if not much pitching. They were in second place entering Memorial Day, just a hair behind the Red Sox. The biggest cheer of the day, however, wasn’t for anybody current. It was for the grainy Thurman Munson tribute video which I was told they showed pretty regularly.

I got the sense every day was Memorial Day at Yankee Stadium. The history, the championships, the glorious past…I got it. But how about the present?

How about it? When the past wasn’t being applauded, the real-time Yankees of 1986 did not seem overwhelmingly supported. Maybe I was just used to the ongoing joyride at Shea, but it seemed pretty quiet, almost fatalistic, for a pretty exciting game, albeit a prototypical Yankee defeat for its era.

The Bombers hit. They scored seven runs. Mike Easler blasted a three-run shot off Mike Witt in the first. Ron Hassey tagged him for a two-run job in the seventh. Problem was, when it came to pitching, the Bombers were blasted. Four Yankee hurlers — Joe Niekro, Al Holland, Bob Shirley and Brian Fisher — worked the sixth, the inning when the Angels scored five runs. But all looked great for the home team when the extraordinary Mattingly drove home Bobby Meacham from second with the go-ahead run. They might have gotten more, but Brian Downing threw out Willie Randolph at third base.

The crowd stirred, if not to Munson tribute levels. Then its fatalism was validated. Dave Righetti came in and allowed a Downing single and Wally Joyner to homer. The Yankees put the tying run on third in the bottom of the ninth, but Terry Forster escaped. The Angels won 8-7. I cheered under my Angels cap as I’d been doing all day. Most of the crowd filed out quietly. I still felt like a stranger in a strange land, but I’d sure had a great time. Adam grumbled. Larry felt Sparky Lyle had been avenged. The walk back to the car past the Bronx House of Detention was most delightful.

I wouldn’t feel right, however, about leaving Yankee Stadium in this space on this note. As pleasant a place as I found it when it was humble, that’s not what Yankee Stadium was. Yankee Stadium was hubristic. It sure as hell was fourteen years later, a Saturday afternoon when the Mets visited and somebody gave me tickets for the boxes in left. This time I wore my Mets cap. This time I had a reason beyond hardwired spite to root for the visiting team. This time I was not gratified by the result. Bobby Jones couldn’t hold a 5-3 lead. In a blink, the Mets were down by six. Those of us there to support the Mets sat quietly while the game got further and further away from us and the majority in attendance roared. Somebody standing behind me bellowed at the Mets’ rookie leftfielder, “HEY TYNER! IT’S TIME FOR YOU TO MAKE AN ERROR!”

And in that very same at-bat Jason Tyner made an error.

I won’t pretend to have enjoyed it, but it compels me to admit that no matter how long it took, the late Yankee Stadium had a way of evening the score against visitors who dared to walk away from it in glee.

by Jason Fry on 8 April 2010 10:43 pm The Mets didn’t commit an error tonight in losing the rubber game of the series to Ronny Paulino, Burke Badenhop and company.

But don’t tell Jon Niese that.

Niese pitched pretty well, mixing his pitches and generally hitting his spots. (Said spots perhaps were a wee too near the heart of the plate in the late goings, but that’s forgivable.) He pitched even better when you factor in how little help he got.

The play-by-play will tell you that in the first Cameron Maybin singled to right and a bit later Dan Uggla singled to left to put the Marlins up 1-0. The play-by-play doesn’t mention that Maybin’s ball journeyed approximately through Fernando Tatis, or that Uggla’s skipped by David Wright’s awkward backhand. Both go more in the category of Plays Not Made than Bad Plays, but they still meant extra pitches to make, extra outs to find and an extra run for the enemy.

The play-by-play doesn’t mention Wright pausing in semi-consternation before routine throws to first, which I’d rather not see become a habit again. It doesn’t mention that Jeff Francoeur gave up on Jorge Cantu’s third-inning double, which should have yielded a Marlin run except for a Met fan who corralled the ball and the gaggle of umpires who decided not to give Hanley Ramirez home plate, even though there was no way Francoeur would have thrown him out. (The Met fan made the defensive play of the night.) None of those misdeeds cost the Mets on the scoreboard, but that doesn’t mean they were pretty to watch.

Oh, and the play-by-play doesn’t mention that Maybin’s fifth-inning single traveled past a nearly immobile Luis Castillo. Cantu, that beady-eyed killer, would soon make it 2-1 Marlins.

No defense would have caught the balls Niese served up in the sixth, so that run’s on him. But with better glovework from his teammates, he might have been in a 1-1 game with 15 or so fewer pitches expended. Again, there were no egregious misplays behind him, and nothing that shows up in the box score. But plays not made can kill the confidence of starting pitchers and tax the bullpen and lead to losses just as surely as big glaring Es on the scoreboard can. It’s demise in slower motion, perhaps, but you wind up in the same place.

by Greg Prince on 8 April 2010 3:56 pm After Sean Green — who elicited the first visceral couch-to-TV reaction of 2010: “Get Sean Green the fuck off my team!” — gave up the laser shot home run to Dan Uggla in the seventh, building the Marlin lead to 6-1, I filed Tuesday night’s game in that one third you’re going to lose, per the ancient and reasonable equation that dictates:

• You’re going to win a third of the games you play.

• You’re going to lose a third of the games you play.

• It’s what you do with the other third that determines your season.

Granted, the first four editions of the Mets couldn’t handle winning a third of their games, and a handful of superteams not clad in Mets uniforms managed to avoid losing a third, but otherwise, it’s a very logical and comforting thought. It keeps you from taking at least 54 games per regulation year too hard. You don’t want to lose, but you accept that losing’s a fact of life.

But when you are compelled to refile a game from “a third you lose” to “the other third”…well, that’s not comforting and it usually causes you to devalue logic. I say usually because a game that sees you come back from 6-1 to tie it 6-6 only to lose it 7-6 tends to favor raw emotion over calm reflection. Yet, unlike Samantha Sang, there was no emotion taking me over (save for Green, and that was earlier) when the game went final. I didn’t expect the Mets to win this game for very long, so it didn’t feel as if the fates were smacking us around.

It came down to a team playing badly beating a team that showed little sign of being very good. We should have taken advantage, but we were incapable. The Marlins winked at us, flashed us some thigh and all but pointed us to the casbah, but we stood there with our thumbs in our gloves not getting the message.

Nevertheless, just standing there almost worked. Just standing there served us well on June 30, 2000, when four consecutive walks were put to astoundingly good use, eventually qualifying them for a plaque among the bricks running down the first base line adjacent to Citi Field. Thing is, that Mets team also had Edgardo Alfonzo singling home the second and third of those walked runners and Mike Piazza homering home the fourth of them, along with Fonzie and himself.

That’s how you earn a plaque, and that’s what was missing last night: big-time stepping up. The Mets scored six runs via two sac flies, a whisper-subtle balk, a well-placed groundout (well-placed because it was eventually founds its way to Uggla, who threw it away) and two bases-loaded walks. Runs are runs, but none of them was driven in by a base hit. According to Adam Rubin of ESPN New York, that’s a franchise record…and that was without the passed ball that wasn’t, the one on which Fernando Tatis didn’t score (I would have liked to have seen an isolated shot of his break from third to determine if he had any kind of chance to begin with) and without the would-be sac fly that I thought Jason Bay could have scored on had he tagged and been in position to take advantage of Chris Coghlan’s rainbow toss to the plate once it flew over the river and through the woods.

No Piazza or Alfonzo in sight (although Alex Cora in No. 13 makes me think of Edgardo every time). No Reyes yet, no Beltran for a bit. No sustained offensive threat with Wright batting third, Bay batting fifth and everybody else gamely battling but indicating only sporadic capability of driving runs home.

And yes, John Maine needed to call a plumber. Or he needed to call me. I feel I sent my boy down the block without training wheels for the first time considering last night was Johnny’s first home start in ten — encompassing his last two at Shea and his first seven at Citi — for which I wasn’t on hand to lend him requisite encouragement. Boy did he look lost without me and his good stuff (probably more the latter than the former). Does he still have good stuff? Late in Spring Training, a friend and I chuckled over a Mets.com headline inviting one and all to watch MLB.tv to observe John Maine “build up his shoulder strength,” as that’s just what draws a fan in to technology.

Maine’s shoulder or whatever body part he depends on wasn’t bringing it last night and his face betrayed that. I’m usually watching him from no closer to the mound than a Promenade seat, so I don’t know if that’s a common expression for him when he’s in Queens. Does he always look so frustrated?

Last night, thanks to SNY, was also my first good look at the bullpen. The physical bullpen, I mean. Yet another Citi Field improvement, being able to see who’s warming up. The problem is getting an even better view of who’s coming in…which is both a cheap shot after one bad night and probably fairly accurate. I’m going to cut Jenrry Mejia first-game slack, but his electric stuff was short-circuited by those teal bastards who saw him enough in Spring Training to know what was coming.

Let’s hang on to this kid at least ’til we go to Colorado, against whom (save for video) he’s a completely unknown quantity. FYI: Jerry Koosman made the Mets out of camp in 1967 as a reliever, was sent down after five appearances and eventually grew up to be Jerry Koosman, greatest lefthanded starter in Mets history. Jenrry Mejia may not be Jerry Koosman, but I’m not willing to assume he’s Jerry DiPoto, either.

Sean Green — striding warily into DiPoto territory by my reckoning — I’m not slack-cutting because I’m a Mets fan and I have to blame at least one reliever for my problems, but Hisanori Takahashi also gets a provisional pass here, partly for being Wes Helmsed to death (nine-pitch at-bat, ouch), partly for it being his first MLB and USA game. Takahashi’s a rookie in that been a Japanese professional a long time way, but he was one of three Mets to make his big league debut Wednesday night. Takahashi was doing it from the vantage point of someone born in 1975, which is rather dated for a freshman in 2010. Mejia and Ruben Tejada, on the other hand, were doing it from the perspective of youngsters born in 1989, the first Mets who could ever say that.

Six Mets have made their team debut this season, four of them born in the ’70s, two in the very late ’80s; DNPers Henry Blanco and Ryota Igarashi, for the record, came to be in 1971 and 1979, respectively. It thus appears, unless somebody revisits January’s mysterious John Smoltz scenario, that we’re done with Mets who were born the same decade as the Mets themselves.

First Met born in the 1960s? Brian Giles, born April 27, 1960, debuted September 12, 1981.

Last Met born in the 1960s? Gary Sheffield, born November 18, 1968, final game as one of us September 30, 2009.

Then again, there was a six-season gap between the going of Rickey Henderson (b. 1958) in 2000 and the coming of Julio Franco (b. 1958) in 2006. And Jesse Orosco (b. 1957) is still lefthanded.

Meanwhile, LHP Jamie Moyer is the scheduled starter for the Phillies Saturday night. Jamie Moyer, who began pitching in the majors in 1986, is the last active player I can call my senior. I will not root for the 47-year-old southpaw to win, but I will root for him to endure.

Being older than all but 749 of 750 major leaguers means I’ve seen a lot, and being me means I remember much of it. I remember thinking in past years that first losses after Opening Day wins have been the only losses I’ve not automatically resented. It’s an annual ritual: We’re 1-0, I can’t imagine the horrors of being 1-1. We’re 2-0, I’m certain the world will come to an end if we’re 2-1. We’re 3-0, I’m usually out in the street all night swilling champagne, so don’t bring me down, man.

But there are exceptions.

• The first loss of 1986 of all years was a debacle I still regret: a 14-inning, 9-8 defeat in Philly, featuring seven walks from Sid Fernandez and seven walks from various relievers. Just think, if we hadn’t lost Game Three that year, we could have gone 109-53, giving lie to that “you’re going to lose a third” nonsense.

• In 1991, there was another first loss in another third game to Philadelphia, at Shea — also a horror show: the Mets walked nine, left 18 on base and lost 8-7 in ten innings. Time of game then made last night’s 4:12 look like a sprint: four hours and fifty-one of the longest minutes I’ve ever spent staring at, ultimately, nothing.

• And the dream of a perfect 2006 went up in smoke in the second game of that season, a 9-5, tenth-inning defeat at the hands of the Nationals, particularly those belonging Jose Guillen, whose bat launched off of Jorge Julio the proverbial ball that’s still going…except it wasn’t proverbial. A NASA satellite just captured a fleeting image of it en route to Jupiter.

Yeah, the 2006 Mets were so disturbed by dropping to 1-1, they were 10-2 within twelve days. First losses, no matter how brutal, don’t necessarily set tones for anything except an antsy next afternoon.

by Jason Fry on 8 April 2010 12:36 am If you had to choose, would you rather be hobbled by horrible starting pitching or terrible relief?

Too much bad starting pitching and the air is consistently out of the fan balloon by the third or fourth inning, leaving you grousing about wasted evenings and wondering if there isn’t something else you should be doing, possibly including tapping yourself over and over again in the kneecap with a hammer to see when it crosses the line from annoying to painful. Too much bad relief and you don’t trust anything good that happens early, because you know the middle innings will be brought to you by Frogger: It sure would be inspiring to hop across this busy highway, but you know you’re going to get pancaked by a semi.

The Mets got the bad starting pitching, while the Marlins got the hopeless relief (or most of it — the Mets weren’t exactly immune themselves) and Game 2 — by turns depressing, inspiring and repeatedly wacky — wound up in the loss column. Which brings up another age-old and unanswerable question: Is it better to fall behind by five and quietly expire, or to come all the way back and then face-plant into defeat anyway?

Speaking of face-planting, John Maine was so horrid that the joy I felt at having survived baseball-less Day 2 was snuffed out almost immediately. His location was hide-your-eyes awful, and he spent most of his time on the mound looking like a guy confronted by an overflowing toilet. And this, folks, is our Number 2 starter. Ricky Nolasco, on the other hand, was terrific, with his only sin getting tired and turning over the ball to his incompetent teammates. The Marlin pen was so staggeringly awful that the Met relievers’ poor showings will get lost in the shuffle a bit, but it was a depressing march: Jenrry Mejia looked pretty much exactly like a kid who throws hard but needs to harness secondary pitches in the minors, Sean Green looked like his usual blandly awful self, and if you’ll forgive me a thoroughly unfair comparison based on a tiny sample size, Hisanori Takahashi sure reminded me of the last Takahashi thrown in over his head in extra innings.

OK, there were positives to take away beyond “Hey, there’s baseball on again!” (Which ain’t nothing — hey, there’s baseball on again!) And some of those positives weren’t exactly ones I’d been counting on. Jeff Francoeur can’t seem to resist swinging at that 0-0 slider in the dirt, but he then reined himself in and had a couple of pretty decent at-bats, and has somehow walked in two straight games. Rod Barajas’s OBP makes Francoeur look like a Kevin Youkilis clone, but he some good counts, and has shown pretty good thump at the plate. Heck, even Mike Jacobs had a game if ultimately futile at-bat.

Maybe it’s just that it’s early, but I found myself feeling like this game was mildly encouraging — even though if I’d shown you a couple of key plays and said they were from 2009 we’d all be yowling about being lousy and snakebit. Having Fernando Tatis thrown out at the plate on an insufficiently wild pitch with David Wright up in a two-out, bases-loaded situation was obviously awful, the first baseball kick in the nuts of 2010. But I can’t bring myself to scold Tatis. When that ball bounded away, I was screaming “Go!” and you probably were too. The ball didn’t carom right off the back wall, but ricocheted left, and it took a awfully good play by John Baker to get Tatis. If Gary Matthews Jr. makes a throw that’s slightly more on target, Wes Helms is out and maybe we’re still playing — but if Helms slides decently, that play isn’t close anyway. And I still can’t figure out exactly what Leo Nunez did to constitute a balk.

A couple of finger-lengths of bad luck, and we lost. It sucks, but it doesn’t feel like a curse or destiny or incompetence or anything like that. It just feels like bad luck. For right now, I can live with that.

by Greg Prince on 6 April 2010 10:28 pm Weather.com says the high in Zip Code 11368 today was 74 degrees. What a waste of temperature.

I get why there’s a blank spot on the schedule between the first home game and the second home game, but nevertheless, Safety Day is a terrible way to follow up Opening Day, particularly an Opening Day as sweetly embraceable as 2010’s. How are the Mets supposed to build on their 1-0 momentum? How are we supposed to build on our reawakened ardor for our team?

Will ya look at that? I’m irked that there isn’t enough Mets baseball to go around. That was the one complaint you didn’t hear much last year.

About the only truly dumb thing I encountered Monday at Citi Field was the ticket-scanning protocol at the Right Field entrance. They have four turnstiles set up, but only two were working (because Opening Day wasn’t on the calendar all winter), and one of them was unable to withstand that brand new bug in the UPC system, the sun. No kidding: when it’s sunny, the scanners have a hard time working, resulting in stupidly long lines and flummoxed supervisors unsuccessfully shielding the code readers from Ol’ Sol with their hands. Instead of worrying about our open water bottles posing a threat, they should just issue tickets to perceived security threats. It’s the best way to keep them out.

Oh, who am I kidding? That was but a minor annoyance, just like the LIRR connection at Woodside smugly speeding off seconds before the passengers who intended to board it could do so, just like the fellow who backed into me steps from Catch of the Day and decorated the front of my hoodie with about a buck’s worth of Long Island-brewed Blue Point Toasted Lager from my just-purchased $7.50 cup. Major league action can withstand modestly minor annoyances when it’s Opening Day. I had made it to the park, I was inside the gates, I was balancing beer and crab cake at one o’clock on a Monday afternoon and, as my co-blogger took perverse delight in noting, there was no need for my hoodie or Starter jacket on the sun-splashed Porch. Monday’s high in Corona, says Weather.com, was 71 degrees and I was decidedly overlayered.

That was my biggest problem? Ohmigod, I went to a Mets game and have nothing substantial to kvetch about. I have only happy memories, 30-some hours removed from the event itself. Jason already gave you the essentials, so, given that I have no new Mets game to watch, I’ll just recap happily.

I happily swung by Team Chapman’s annual tailgate fiesta, still festively delicious and deliciously festive. Bonus track: the WFAN van drove right up to their spread and handed us a stack of 40th anniversary highlight CDs from 2002…which is the sort of thing that literally happens in my dreams.

I happily bulldozed the lines by the Rotunda so I could check in with my brick, still where I found it last April.

I happily scooped up my Citi Field Apple bank, now flanking my Shea Stadium Apple clock along our living room’s Bobblehead Row.

I happily accepted two pencils with my yearbook and program even though I, like the Marlins, had no intention of scoring that much. But at $17 for a yearbook and a program, I’m taking what they give me.

I happily and lustily booed every Fish during the introductions (which I watched from Field Level, having been held up at the Right Field entrance by the recalcitrant scanner), following up on my bile from the end of the Mets’ open workout Sunday when the Floridians nefariously materialized for their turn on the field. Clad in black by the third base dugout, it was too much like a vision from the moments after the last game at Shea thudded to an end. “HEY MARLINS, YOU SUCK!” I was thoughtful enough to inform them on Sunday. Fans need an open workout, too.

I happily applauded when I was supposed to be observing a moment of silence for Jane Jarvis when Howie Rose noted her offseason passing. A great performer deserves applause, not silence. (I happily swooned in the middle of the fifth when the Mets saw fit to play Jane’s 1996 recording of “Meet The Mets”.)

I happily listened as my fellow savvy fans let the Met training staff know we’ve been paying attention. No offense, Ray Ramirez, Mike Herbst and your colleagues. I didn’t boo, though, instead admonishing, “DO YOUR JOBS BETTER!” and hoping maybe everybody connected to Mets medicine and baseball would get the message.

I happily dug on the aforementioned crab cake sandwich and Blue Point Toasted Lager. Try both at Catch of the Day, even if in Year Two of Citi Field, food and drink no longer appears to constitute the only reason to make the trip to the ballpark.

I happily agreed with the only truly engaged member of our row, the guy who advised the rest of us that Rod Barajas is “the shit,” that we wouldn’t know that because “he’s from Canada” and that we were all too quiet for his liking. I always feel bad for the one slightly belligerent LET’S GO METS! guy in any given section if he’s sincere about it. You can’t let the LET’S GO METS! guy chant by himself. He gets louder, he gets more desperate, we all come off as snobs because of it. Hence, I gave him a little air cover, even though the Mets were going fine on their own steam by then.

Happy, happy, joy, joy, the Mets are 1-0, the Mets have a marvelous museum and a ton of Amazin’ accoutrement in our midst and the only problem I have is there was no second consecutive afternoon in the Citi Field sun. What a downer to have to wait until 7:10 Wednesday night.

The Mets worry about rain on Day One the way I worry about it being colder than it feels. Yet the last time the Mets were rained out in their Home Opener — which is why the second day is reserved for a precautionary makeup that would accommodate a theoretically postponed sellout crowd — was 1997. As it happened, that was the year the Mets scheduled their Opener for a Saturday because they were hesitant (to put it kindly) to open on the same Friday afternoon as another team in the same city on the day that other team would be having some sort of flag-raising ceremony…and the two teams were opening in New York on the same weekend because MLB had sent them both to California in early April to avoid bad Northeastern weather…which is what New York was soaked by when the Mets attempted to open that Saturday…while it was perfectly fine in early April when neither local club was home.

End result: The Mets wound up playing and being swept by the Giants in an Opening Day Doubleheader on the Sunday after the Saturday rainout, and — because the Mets were bad in 1996 and looked no better on that extended West Coast trip to open 1997 (3-6) — no large crowd was inconvenienced. Paid attendance for the makeup doubleheader that began the home schedule 13 years ago was a shade under 22,000. That was the worst Home Opener crowd Shea hosted since 1981 (15,205), the previous time a rainout necessitated use of the Safety Day. That was also the year I had tickets to my first Home Opener and couldn’t use them thanks to precipitation and my limited flexibility as regarded high school truancy.

Not that I’m still bitter about it 29 years later.

You can’t fool Mother Nature, but you can’t negotiate with her, either. So why bother trying? Instead, as Steve Winwood told me repeatedly one summer long ago, roll with it, baby. Once the Mets saw the forecast for Tuesday, they should have added on an extra game on the spot. Seriously, what do the players have to do but enthrall us? I had been thinking it was a little pushy to make them play every day down the stretch in Spring Training and then drag them to Flushing for a public workout, then have the Opener the next day and then shuttle them to a Welcome Home dinner Monday night, but then I read a dispatch from the Major League Baseball Players Association advising us that the Opening Day average player salary stood a little north of $3.3 million. There went my sympathy for their lack of “me time”.

It’s too late to do anything about it now, but let’s take the impromptu second game plan under advisement should the meteorological and Metropolitan atmospheric conditions intersect this gorgeously again. Make it like the snow day that, if our school district didn’t use it all winter, was tacked onto Memorial Day weekend. The Mets play the Marlins approximately 50 times a year. We’ll be bored with/tortured by them come September. So let’s play all we can in April, while the weather’s warm and we’re all as happy as clams.

Or is that crab cakes?

|

|