The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

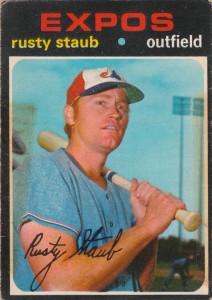

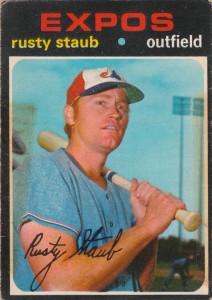

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 14 February 2010 12:16 am Anyone who knows Dan Quayle knows that, given a choice between golf and sex, he’ll choose golf every time.

—Marilyn Quayle

The Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue arrives in my mailbox every February to no particular anticipation or fanfare. Certainly its contents are well put together, and I wouldn’t argue they don’t merit an objective hubba-hubba! and a few wolf whistles from those given over to such expressions of approval. Yet I find the Swimsuit Issue disappointing these days because it’s a copy of Sports Illustrated that ain’t got no sports in it.

I’m not kidding. I like sports. I like other things, too, but I don’t like my sports magazines to be scantily clad when it comes to what they usually cover.

Newsstand and ad sales indicate, however, that the Swimsuit Issue is greeted with what might be called broad-based enthusiasm by its reading public, no matter how little there is to read beyond the captions of where the swimsuit models are being languid and who manufactured what little they’re wearing. Indeed, SI hit upon a goldmine when it figured out swimsuit modeling, particularly in the dead of winter and after the Super Bowl, makes for excellent Illustrated, lack of Sports notwithstanding.

Whichever way you wish to classify it, they do a nice job of displaying the merchandise (the swimsuits, I mean). Even if it’s a Brooklyn Decker on the front instead of a Brooklyn Dodger — which had to disappoint Fred Wilpon when he took a second glance at the cover lines — one has to appreciate the photography, the fashion, the artistry…the whatever you like to appreciate.

Even if it ain’t got no sports. Which is what I like in my sports magazines.

Still, I’ve maintained one particularly pleasant memory of a Swimsuit Issue from years gone by. OK, I have a few — I’m not completely made of cork, rubber, wool and stitched white cowhide, y’know — but one edition above the rest stands out: February 9, 1987. Elle MacPherson was on the cover, taking “a dip in the Dominican Republic,” which was as fine as it was dandy, but that’s not the memorable part. It was a two-page spread, shot in the same Caribbean country, described as such:

Kathy and Monika, who waits to bat, are a hit with the Cedeño team, in uniforms by H20 ($72).

I don’t mind telling you that this was a pretty hot picture. Kathy is Kathy Ireland, who was to supermodeling back then what Doc Gooden was to pitching, and you know what she’s wearing besides that “uniform”?

Same thing Doc wore when he was on the cover of SI: a Mets cap.

Now who’s saying Hubba-Hubba?

What made this tableau particularly attractive was the reason Kathy was topped off so stylishly. In the winter of 1987, if you’re posing a model in a baseball motif, you know the ensemble is not complete without royal blue millinery accented by a splash of orange. Baseball, in the winter of 1987, following the fall of 1986, equals Mets.

World Champion New York Mets, if you want to be a model of accuracy.

You’ve got a supermodel? You can’t have her modeling the colors of anything less than a super team. No team loomed as more super or superb at that moment in time than the Mets. It would have been a fashion faux pas to have her in anything less (not that Miss Ireland could have been wearing much less).

Monika, incidentally, is Monika Schnarre; she’s waiting her turn in a Red Sox cap — a perfect pecking order in the wake of ’86.

Kathy Ireland in a Mets cap? With defending champion Pitchers & Catchers barely two weeks away? Suddenly the dead of winter was indisputably springing to life in early February of 1987.

Yes, this is clearly the best illustration in the history of Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issues, which, back then, weren’t standalones. They had some actual sports in the pages that came after the modeling, which is significant for our purposes as Mets fans because of the sentence that followed the plug for Kathy’s and Monika’s swimsuit designer.

Turn the page for more on the Dominican Republic’s favorite sport.

At si.com/vault, you can actually virtually turn the page of any Sports Illustrated issue, so I took the advice from the spread of pages 150-151 and did what the magazine suggested 23 years ago. And I came upon a story I vaguely recalled but, for some reason, not as vividly as I recalled Kathy Ireland in a Mets cap.

The article is headlined “Standing Tall at Short,” and is written by Steve Wulf. As long as SI was headed to the Dominican to take advantage of its “lush setting” for shooting models, they decided to explore its other great natural resource: shortstops.

There was a point back in the mid- to late ’80s when it seemed every shortstop under the sun hailed from the Dominican Republic. On April 27, 1986, Wulf wrote, nine different Dominicanos played short in the big leagues. One, Rafael Santana, was doing so for the Mets. Two others, Tony Fernandez of the Blue Jays and Julio Franco of the Indians, would eventually become Mets

“Nosotros somos la Tierra de Mediocampistas,” says Felix Acosta Nunez, the sports editor of Santo Domingo’s Listin Diario. “We are the Land of Shortstops.”

Sadly, the setting for those Dominican youths who grew up to play in the majors wasn’t anything close to lush. From Wulf:

In the Dominican Republic, where the average family income is $1,200 a year, poverty is not an isolated problem; it’s the way of life. Also, the quality of education is very low, lower than in the Caribbean’s other pools of baseball talent, Puerto Rico and Venezuela. So the kids don’t stay in school, not when they can be out on the streets or in the fields playing baseball. “It’s very much like the United States in the ’30s, during the Depression,” says Art Stewart, director of scouting for the Kansas City Royals. “Those were sad times, but they produced great ballplayers because baseball was one of the only avenues of escape.”

Talent plus motivation equaled a plethora of shortstops, particularly the San Pedro de Macoris region, from whence seven 1986 major league shortstops hailed. It was a curiosity, all right, but there was more to the story than the trivia of so many players playing the same position from the same relatively obscure area. The men who made the majors — several of whom Wulf gathered for a shortstop summit — provided baseball equipment and hope for the kids who would come up behind them. Alas, there wasn’t always enough of either. “The players who have made it in the big leagues generously buy gear for the kids, but there is never enough to go around,” Wulf writes. “Too often the youngsters must make do with a glove fashioned from a milk carton, a ball that is a sewed-up sock and a bat made from a guava tree limb.”

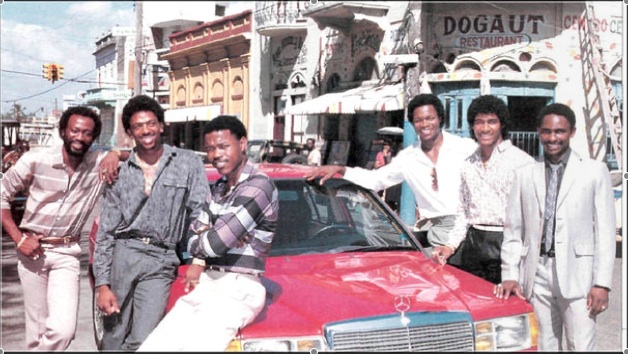

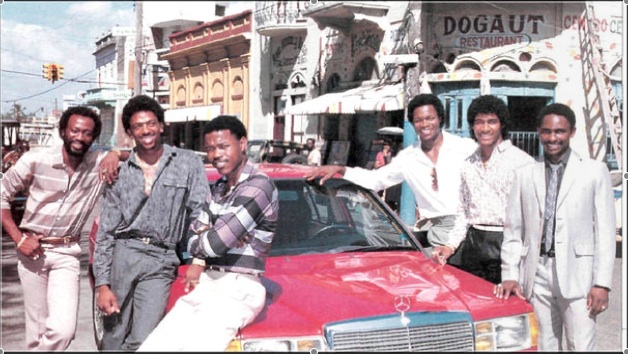

From left to right in the above photo, we meet the cream of the ’86-’87 Dominican shorstop crop: Alfredo Griffin, Julio Franco, Rafael Santana, Tony Fernandez, Mariano Duncan and Jose Uribe. Santana was hardly the star of this Dominican shortstop class; that distinction belonged to Fernandez (whose game mysteriously flickered during his abbreviated 1993 Met tenure). But Ralphie, as his teammates used to call him, shines in the story, nonetheless, quite befitting his status as a World Champion New York Met.

Though he was never considered on the same lofty level with his fellow Dominican shortstops (or ’86 teammates), Wulf describes La Romana native Santana — “the only one with a World Series ring” — glowingly in his piece. He’s the man who “paid [his dues] the longest,” stuck first in the Yankee farm system, then the Cardinals’, where Ozzie Smith left everybody waiting. “Playing in the minors for so long taught me patience,” Santana told Wulf.

You can see the patience in the way he plays shortstop, the way he makes every play close. The Mets finally turned to him in the middle of the ’84 season, and he has been their starter ever since.

Rafael lasted only one more season as a Met. The organization was high on Kevin Elster and traded the incumbent shortstop after 1987. Santana was steady defensively if indifferent offensively. Demographically, though, he was a sign of shortstops to come. According to Ultimate Mets Database, fifteen of the 107 Mets to play shortstop through 2009 were from the Dominican Republic — nearly 14%. Eleven of them were Santana’s successors. Rafael lasted only one more season as a Met. The organization was high on Kevin Elster and traded the incumbent shortstop after 1987. Santana was steady defensively if indifferent offensively. Demographically, though, he was a sign of shortstops to come. According to Ultimate Mets Database, fifteen of the 107 Mets to play shortstop through 2009 were from the Dominican Republic — nearly 14%. Eleven of them were Santana’s successors.

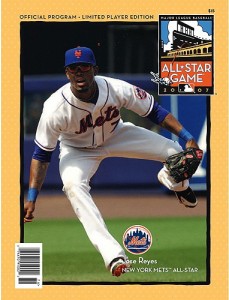

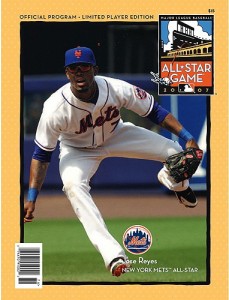

The most famous and accomplished of them as a Met, at least individually considering he doesn’t yet have a World Series ring, is Villa Gonzalez’s Jose Reyes, hopefully back in the saddle on Opening Day 2010. San Cristobal’s Jose Vizcaino held down the position effectively for a couple of years in the mid-’90s. The rest didn’t necessarily distinguish themselves as Met shortstops.

Chronologically, they were:

• Junior Noboa (1992)

• Tony Fernandez (1993)

• Manny Alexander (1997)

• Wilson Delgado (2004)

• Anderson Hernandez (2005-07, ’09)

• Argenis Reyes (2008-09)

• Fernando Tatis (2009…a pair of emergency cameos)

• Wilson Valdez (2009)

• Angel Berroa (2009)

Before Santana? It had been three years since a Dominican played short for the Mets when Rafael joined the club in ’84. His most direct predecessor was Frank Taveras of Las Matas de Santa Cru. Taveras manned short, not always brilliantly, from ’79 to ’81. Frankie’s stock-in-trade was base-stealing. He set the pre-Mookie single-season record with 42 bags in 1979, despite playing the first two weeks of that year with the Pirates (who — perhaps coincidentally, perhaps not — went on to win the World Series without him). Before Taveras, the most recent Dominican shortstop on the Mets was Barahona-born utilityman deluxe Teddy Martinez, who played six positions in five Met seasons. As the Super Joe McEwing of his day, Ted filled in often at short during Buddy Harrelson’s various injuries in 1973’s pennant campaign.

Prior to Martinez’s 1970-74 stint, there was only one Dominican who played shortstop for the Mets. In fact, he was the first Dominican Met — and the first Dominican shortstop in the majors. I would not have known about him had I not been staring (in disappointment that it ain’t got no sports, I swear) at Brooklyn Decker’s Sports Illustrated cover earlier this week. If I hadn’t seen Brooklyn, I wouldn’t have thought to look for Kathy Ireland in a Mets cap. If I hadn’t tracked Kathy’s picture down, I wouldn’t have revisited Steve Wulf’s profile of Rafael Santana and his contemporaries. And if Wulf hadn’t drawn me in to his tale of San Pedro de Macoris, I wouldn’t have suddenly become aware of the contribution of Amado “Sammy” Samuel to baseball history.

Amazingly, even in the baseball-mad precincts of San Pedro de Macoris in 1987, Samuel was a bit of a prophet without honor. The locals, Wulf reported, thought outfielder Rico Carty was the first Macorista to make the major. Not so — Sammy got to the Braves ahead of him in 1962. Even Wulf concedes his discovery of “the very first Dominican shortstop to reach the big leagues” could be considered underwhelming.

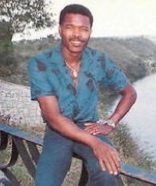

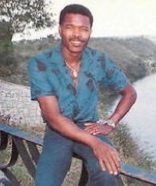

It’s not hard to overlook Amado Samuel. He played in only 144 major league games over three seasons for the Braves and New York Mets, batting .215 with three home runs and not one stolen base. About the only time his name comes up is when some publication lists the 78 men who have played third base for the Mets. Even the Dominican aficionados have lost track of him; some say he is living in New York City, others say he is in Santo Domingo, still others think he has passed away.

Turns out those folks were wrong. Sammy made Louisville his home from the time he played there in the minors in 1961. He married a Louisville lady, picked up a southern accent and went to work after he was done playing ball at the General Electric plant. “I didn’t play too long after the Mets ’cause I tore up my knee in Buffalo,” Samuel, then 48, told Wulf. “Missed out on the big bucks, I guess, but I’m healthy, doing fine, no complaints.” Not only no complaints, but some justifiable pride:

“Now that you ask, I am proud of being the majors’ first Dominican shortstop. I guess there are a lot of them now. You know, one reason there might be so many is the ground they play on. You’ve got to have very good hands to play on those fields.”

About the only thing I knew about Sammy Samuel before Steve Wulf (and Brooklyn Decker, indirectly) got me up to speed was his nickname. I only knew that because my friend Joe Dubin sent me a recording of the first radio broadcast in Shea Stadium history, and Bob Murphy referred to the Mets’ starting shortstop that momentous day as Sammy, not Amado. Murph, Ralph Kiner and Lindsey Nelson were preoccupied by the wonders of freshly opened Shea to spend a lot of time relating Sammy’s story to their audience on April 17, 1964. Ralph, however, had the privilege of calling the first multiple-run, extra-base hit in Shea Stadium history in the fourth inning this way:

“And SAMUEL has put the Mets out in front! Sammy Samuel with a sharp line drive right over the bag that hit in fair territory, right down the left field line.”

Sammy, who wound up on second, drove in Jesse Gonder and Frank Thomas (despite Thomas falling down en route to home). It put the Mets up 3-1 on Bob Friend and the Bucs. It wouldn’t get any better for the Mets that day. They’d lose 4-3 to Pittsburgh.

It wouldn’t get much better for Samuel as Met, either. Despite the two ribbies and a batting average of .364 after three games, Casey Stengel sent Ed Kranepool up to pinch-hit for him in the eighth. Sammy was never quite the same after that. The first shortstop Shea ever saw watched his offense plummet. Within a few weeks of Shea’s opener, Samuel’s average was down below .200. On a team that wasn’t going anyplace but tenth, Sammy’s spot was soon enough on the bench. Eventually, right after Shea hosted its only All-Star Game, it was Buffalo, then (as now) the Mets’ Triple-A affiliate. He never made it back to Flushing.

Amado Samuel was in on some Met history besides his Opening Day onslaught. He came on for defense, replacing Roy McMillan, after the Mets opened a 13-1 lead on the Cubs at Wrigley on May 26, a game that we would hold on to win 19-1. From it was born the legend of the phone call to the newspaper sports desk:

“How’d the Mets do today?”

“They scored 19 runs.”

“Did they win?”

It was 1964. It wasn’t out of line to ask the followup.

Sammy went 0-for-1 in Chicago that day. His next appearance, May 31 at Shea, would net him two hits and a hit-by-pitch, which sounds like a splendid day’s work…except he had seven at-bats…and the game went 23 innings…and the Mets lost 8-6 in the second game of a doubleheader to the Giants…with Sammy flying to right to end it…after losing the first game 5-3. Sammy played second base from the third (Casey had pinch-hit for starter Rod Kanehl in an effort to score early) through the 23rd.

Starting at third base in the opener of another Sunday Shea doubleheader three weeks later, against Philadelphia, Samuel lined out (the New York Times reported Phillie shortstop and future Met coach Cookie Rojas had to jump “about two or three feet” to make the catch) and popped up in two at-bats. He was pinch-hit for by George Altman in the bottom of the ninth. Altman didn’t do any better, striking out. Then John Stephenson struck out. Every Met who batted made out. That was June 21, Jim Bunning’s perfect game. It kind of took the edge off Samuel’s June 20. As Centerfield Maz noted recently, Sammy collected three hits the day before Bunning cooled him off.

For a guy who played in only 53 Mets games total, Amado Samuel was a part of more weirdness than most men experience in a lifetime. Upon coming across his name in Wulf’s 23-year-old Sports Illustrated article, I wondered if there was more Sammy’s Met tenure than Gumplike accidental tourism. So I asked Joe Dubin what he remembered about Samuel. Joe’s been watching the Mets since there were Mets and he seems to have seen everything that I missed.

“I remember having high expectations for him as a Met,” Joe kindly told me. “But for me, that feeling applied to every new player we got. I immediately envisioned Sammy as a potential superstar as I did every other player we obtained. When I was a kid growing up as a New Breeder, everything was seen through rose-colored glasses.”

That’s funny, I thought. I viewed Teddy Martinez the same way. And Frank Taveras. And Rafael Santana. And Jose Vizcaino. And Jose Reyes. Wilson Valdez…not so much. But there’s still time.

I appreciated Joe’s recollection, but still I wondered. I flipped through Bill Ryczek’s essential early-Mets history and learned only that Amado Samuel was, come 1965, part of “probably the sorriest Triple A club in baseball”. For the record, the ’65 Bisons, chock full of discarded ’62-’64 Mets, went 51-96, placed eighth of eight and finished a distant 34½ games out of first. They were even worse than the notoriously bad Bisons of 2009 (a league-worst 56-87 despite being stocked with so many past and future Mets).

The only 1964 Mets yearbook I have is a revised edition, an edition out of which Sammy Samuel was revised right out of once he was demoted to Buffalo. The only 1964 program I have offers no biographical information either, but the scorecard portion offers a happy recap. Thanks to whoever filled it on May 13, I can tell the Mets beat the Milwaukee Braves 5-2, that Jack Fisher beat Tony Cloninger and that Samuel, wore 7, batted eighth, flied out to right, grounded to short, grounded to the pitcher and grounded to third (5, unassisted). I also learned from an advertisement accompanying the scorecard portion of the program that for a Grouchy Stomach or a Nervous Tension Headache, I should take Bromo Seltzer. I suppose with the Mets in the midst of a 53-109 season, the Bromo Seltzer people figured Mets fans were a prime target audience for their product.

Still, nothing much on Samuel. I checked next with Jason. I asked him to pluck Sammy’s 1964 card from The Holy Books and let me know what it said on the back. After declaring it “Strangest. Request. Ever.” he dutifully reported that Topps dutifully reported, “The Mets acquired Amado from the Braves in late ’63. The youngster jumped from Class D to Triple A before coming to the majors in ’62.”

There was also a trivia question regarding the holder of the Giants’ record for hits in one year. Then as now, the answer is Bill Terry.

Before getting completely off track, I discovered the SABR Biography Project had not long ago profiled one Amado Samuel, a.k.a. our Sammy. According to Malcolm Allen’s comprehensive research, major league shortstops have continued to come out of the Dominican Republican at a rapid rate in the two-plus decades since Steve Wulf visited San Pedro de Macoris. By 2007, more than a hundred had taken a turn at the position. And during the games of September 24, 2005, Allen writes, fourteen different Dominicans trotted out to short (including Reyes and his opposite number that night, Cristian Guzman of the Nationals). The author confirmed what Wulf asserted in 1987, that Samuel was indeed the “first Dominican major leaguer to primarily play shortstop, as well as the first big leaguer from San Pedro”.

Allen does a magnificent job of following Samuel’s entire life — which, at age 71 is still going strong in Louisville — including his sale by the Mets back to the Braves after the ’65 season. Samuel needed to be moved out of the organization to make room for a younger shortstop…a fellow by the name of Bud Harrelson.

Thus, in a way, Sammy Samuel is connected to both World Champion New York Met shortstops. His departure created space for Buddy and, regarding his countryman Ralphie, he told Wulf in 1987, “I’ll go to a game in Cincinnati once in a while…but the Mets are still my team. I like the shortstop with the Mets, Santana. He’s pretty good.”

Twenty-three years ago, a retired baseball player who most everybody had forgotten about — and who hadn’t been a Met for twenty-three years to that point — pledged allegiance to the team that let him go and offered an elegant benediction to the unassuming player who followed twice in his footsteps: as a Dominican major league shortstop and as a New York Met shortstop. So it turns out Kathy Ireland in a Mets cap wasn’t the most beautiful thing Sports Illustrated featured in that Swimsuit Issue after all.

Thanks to the blog Condition Poor for unwittingly lending us the image of the 1964 Topps Amado Samuel card.

Please join Frank Messina and me on Tuesday, February 16, 6:00 PM, at the Cornelia Street Cafe in Greenwich Village for a night of Mets Poetry & Prose. Details here, directions here.

by Greg Prince on 12 February 2010 5:48 am “Who can go the distance?” Don Henley asked some thirty years ago before the Eagle answered his own question: “We’ll find out in the long run.”

There’s a long run coming this November, and I have a pretty good hunch about who’s going the distance that day.

Sharon Chapman, like you a Mets fan and like you a reader of Faith and Fear in Flushing, is training for the New York City Marathon. It’s a long run, all right — 26.2 miles for those of you scoring at home. It’s a run with more than a dash of Met meaning, too, because of what Sharon’s doing while preparing.

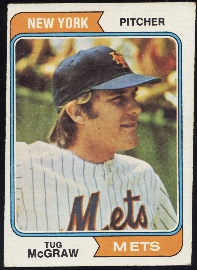

She is using this personally momentous occasion to raise money for the Tug McGraw Foundation, a group devoted to making the lives of people coping with brain cancer, post-traumatic stress disorder and trauma brain injury better. TMF was established as Tug himself — the man who originated the credo “You Gotta Believe” while closing out games for the 1973 National League Champion Mets — was fighting brain cancer. Tug, a Met stalwart from 1965 through 1974, died in January 2004. The Foundation continues to seek solutions to a deadly scourge in his name.

The intersection of Sharon Chapman’s marathon aspirations and the memory of Tug McGraw crosses our doorstep because Sharon reached out to us and asked if she could represent “Faith and Fear Nation” on her journey and wear a wristband with our blog logo. I didn’t even know we had a nation (maybe a dorm), but Jason and I said, sure, we’d be honored.

Since we’re unofficial sponsors, I thought it appropriate to check in with Sharon and find out a little more about how all this came together, how it’s progressing and get a greater sense for her fellow FAFIF readers why a Met legend, her Met fandom — and another Mets fan she has yet to meet — coalesced to make this more than just one woman running one race.

How long have you been running?

I started running in the spring of 1999. I ran three times a week until the fall of 2008; at that time I had started Weight Watchers. Weight Watchers cajoled me into increasing my exercise by allowing me to exchange the earned Activity Points for Food Points, and as a result I started running virtually every day.

How did your running progress from simple exercise to a try at the New York City Marathon?

I blame Valerie Bertinelli. Seriously.

Even though Valerie is a Jenny Craig spokesperson and I’m a Weight Watchers kind of girl, I attached to Valerie as my weight loss role model. She’s only slightly older than I am, she was looking to lose a similar amount of weight, and she wasn’t looking to become ultra-skinny; I could relate to her. Even though Valerie is a Jenny Craig spokesperson and I’m a Weight Watchers kind of girl, I attached to Valerie as my weight loss role model. She’s only slightly older than I am, she was looking to lose a similar amount of weight, and she wasn’t looking to become ultra-skinny; I could relate to her.

To digress — I promise this comes together — in January 2008 I went to Bermuda and ran the 10K race as part of their International Race Weekend. Except I wasn’t prepared for Bermuda’s steep hills, and I couldn’t run the whole way. I was very disappointed to have done poorly in a race in Bermuda, which is my favorite place in the world.

So flash forward to July 2009. My husband Kevin and I were in the car, and I told him that, now that I was at goal weight and in the best shape of my life, I wanted to return to Bermuda to get the 10K right. I also told him that I had no desire to run anything longer than 10K; I wasn’t interested in running a half marathon or anything like that.

Not 20 minutes later, in my Entertainment Weekly, I read this headline: Valerie Bertinelli Runs Her First Half Marathon! “Damn!” I said. “Now I have to run a half marathon!”

I ran that half marathon in Jersey City in September. At first, I thought that would be it. But then, the idea of running the New York Marathon started hitting me. When Kevin and I were in law school in Boston, I would watch the New York Marathon on television just to watch shots of New York because I was homesick.

To go from wistfully watching the Marathon on television to actually running it is something I never imagined, and I realized that it’s something that I need to try.

And I did go back to Bermuda this past January. Not only did I conquer the hills of Bermuda’s 10K race, but the next day — wearing my FAFIF wristband — I ran the half marathon there as well.

By the way, Valerie Bertinelli is running the Boston Marathon this spring as her first full marathon. So I’m still working on keeping up with her. But if she ever decides to go for a triathlon, she’s on her own.

What has the training been like to this point? What’s ahead?

Initially, the training wasn’t all that different for what I’ve been doing since the Fall of 2008. I just kept running every day. But recently I started increasing my long runs, which also means I need to build a rest day and a cross training day into my schedule. I hit a wall during my first attempt to run 20 miles, so now I’m working on proper nutrition for long runs — making sure I’m eating breakfast on those days, finding out which gel packs I like best, adding electrolytes to the equation, etcetera. I’ve gone from being a recreational jogger to someone who is becoming more knowledgeable about running, which is a transformation I never anticipated going through.

I started panicking about making the New York Marathon my first marathon, so I signed up for the New Jersey Marathon in May. I call it my training marathon; I can make all of my mistakes there so I’ll know what I’m doing in New York. The timing is good. I’ll have six months between the two races. That will give me two months to go back to easier running before I have to train again.

You met and interviewed Tug McGraw once. What were the circumstances? As someone who grew up a Mets fan, watching Tug, describe that experience.

I used to write a column called Fan’s Voice for New York Mets Inside Pitch. In early 2003, I had the opportunity to interview Tug by phone for the magazine. It was a great experience, and an instructive one. I was a novice, and Tug teased me about things like not recording the conversation. He was also very personable, entertaining and witty. The interview was basically everything one would ever expect from the man who coined the phrase “Ya Gotta Believe,” and it was a wonderful experience.

The interview was published a couple of weeks before Tug’s diagnosis that he had a malignant brain tumor. I was absolutely shocked. In retrospect, there may have been two times in our interview that he didn’t have an answer off the top of his head, but for the most part he was sharp and on the ball. It was inconceivable to me that he could have been ill at the time we spoke.

The postscript to this story is that my husband and I attended a Mets-Phillies game in the Phillies suite at Veterans Stadium in September of that year because we were involved in a local Cub Scouts group outing that season. I remember sitting down in my seat, looking over to the next section, and seeing a kid who looked like Tug McGraw’s son Matthew. At second glance, I noticed that it was indeed Matthew, and that Tug was sitting next to him. I went over and introduced myself in person to Tug, who remembered me and was very excited to meet me in person. That was one of the biggest thrills in my life.

How did you find yourself involved with the Tug McGraw Foundation vis-à-vis the marathon? And what is Team McGraw?

Kevin and I have actually attended several Tug McGraw Foundation events since the foundation’s inception. We went to a party at Citizens Bank Park in 2004, and to gala dinners in Philly and in New York. BTW, at the two gala dinners, each time I wanted my husband to take my picture with Tim McGraw, and both times we had camera malfunctions. Maybe one day I’ll get my picture taken with Tim…

But back to your question. When I decided that I wanted to run the New York Marathon, I started researching how I could get in. One cannot count on getting in through the lottery, and I was never going to be fast enough to get in via a qualifying time, but I saw that one could get in by raising money for certain charities that had spaces in the Marathon. I remembered reading about Team McGraw from a Tug McGraw Foundation newsletter, and looked into that. It seemed to me to be the perfect fit; I could achieve my goal of running the New York City Marathon and help an organization that has meaning to me at the same time.

Team McGraw is comprised of runners who participate in races to raise money for the Tug McGraw Foundation. It is headed up by musician Jeff McMahon, who is a distance runner himself and is also Tim McGraw’s keyboardist. The coach is Kevin Leathers, who’s given me some excellent distance running advice. Throughout the year different Team McGraw teams participate in races throughout the country. In fact, in addition to the NYC Marathon, I’m also participating in the NYC Half Marathon on March 21 as part of Team McGraw.

Being able to run the Marathon with a support group is a very comforting feeling. I won’t have to worry about finding my way or figuring out certain things on my own. I’ll have a group of wonderful people guiding me and watching my back. Because, frankly, I’m a little scared about tackling this kind of a distance; having Team McGraw there to support me is making the concept of 26.2 miles much less daunting than it would otherwise be.

You and I were both kids when Tug was traded to the Phillies. What do you remember most about Tug as a Met? Was he one of your favorites?

I remember liking him. Everyone loved Tug, but I can’t remember too much about his Met playing career specifically. I do remember reading his Scroogie cartoon in the newspaper, though, and enjoying that very much. That’s the most specific memory of Tug from my childhood that I can muster. I remember liking him. Everyone loved Tug, but I can’t remember too much about his Met playing career specifically. I do remember reading his Scroogie cartoon in the newspaper, though, and enjoying that very much. That’s the most specific memory of Tug from my childhood that I can muster.

Does what you’re doing now give you a new perspective on Tug’s signature phrase?

Ya Gotta Believe it does. That truly is a great motivating phrase. For that matter, it was also a motivator for my Weight Watchers success (I used whatever mind games I could in order to drop those forty pounds). Whenever you need to give yourself a kick in the rear, Ya Gotta Believe is a great motivator.

Tug spent roughly half his career with us, half with the Phillies, and he remained associated with them right up the time of his diagnosis with brain cancer. The Phillies are to be commended for having done a great job supporting the Foundation, no matter the rivalry that’s developed between the two clubs and their fans. Still, how odd is it for you to be wearing red in this context?

It’s odd, for sure. But, as you said, understandable. Tug was a Spring Training coach for the Phillies when he got sick, and spent much of his final year living in the Philly area.

For what it’s worth, while I don’t root for the Phillies, I do have to admit that the organization has always treated me very well. I live in Central New Jersey, and have attended many games in Philadelphia over the past several seasons. The Phillies have always treated me as a valued customer, which, sadly, I can’t say about my own team.

Kevin and I will be attending the Tug McGraw Foundation Awareness Night in Philly on April 30, which will be during a Mets-Phillies game I’m hoping that by wearing my Team McGraw shirt that the Phillies Phans won’t give me too much abuse for wearing my Mets cap to the game.

And how much blue do you hope to inject into the Foundation?

I’m definitely hoping to inject some more blue into TMF. I think that a lot of the TMF personnel are simply unaware of just how evenly split Tug’s career was. Also, it’s to their benefit to court Mets fans, since we’re certainly at least as generous as the Phillies Phans! Everyone who knows me at the Tug McGraw Foundation knows that I’m a passionate Mets fan, and I think that’s a good first step toward getting TMF to be more aware of the fact that Mets fans are a resource they should be approaching more proactively.

Could the Mets be doing more — or something — in this area?

For sure! If the Phillies can do a Team McGraw Awareness Night, it seems like the Mets could do something similar. I’m not sure whether that kind of thing would be initiated by the TMF or the Mets, but someone should look into making that happen. Tug is a member of the Mets Hall of Fame. The team should definitely honor his memory by supporting the foundation that bears his name.

Tell us a little about the young man you’re running for. We understand he’s a Mets fan, too. What does it mean to be “running for” twelve-year-old Connor McKean?

Team McGraw asked whether they could pair me up to run on behalf of one of their members. Ultimately, they paired me up with Connor.

I haven’t met Connor in person yet, but I have exchanged e-mails with his mom and I hope to meet them sometime this season. Connor was diagnosed with a rare brain tumor called an ependymoma on October 17, 2007. He still suffers from headaches, but is working hard to keep up in school. I chose to run for Connor after I heard that he only wanted to wear his David Wright jersey when he was undergoing chemotherapy. I haven’t met Connor in person yet, but I have exchanged e-mails with his mom and I hope to meet them sometime this season. Connor was diagnosed with a rare brain tumor called an ependymoma on October 17, 2007. He still suffers from headaches, but is working hard to keep up in school. I chose to run for Connor after I heard that he only wanted to wear his David Wright jersey when he was undergoing chemotherapy.

As the parents of two teenage boys and a girl in college, Connor McKean’s situation makes us really appreciate our own kids’ health all the more. It definitely makes running the Marathon for Connor McKean all the more poignant for me, because it could just as easily be one of my own kids going through the treatments and adjustments that he has gone through.

What do you hope you will have accomplished by November after the funds have been raised and the finish line is crossed?

Wow — I really haven’t thought in terms of the Big Picture much. So far I’ve been thinking about all of the small pictures leading up to November 7. For me, personally, I will have the satisfaction of having completed the New York City Marathon. I love this quote by Marathon founder Fred Lebow: “In running, it doesn’t matter whether you come in first, in the middle of the pack or last. You can say, ‘I have finished.’ There is a lot of satisfaction in that.” Since I was never blessed with speed, even as a youngster, I definitely hold this thought dearly.

Obviously I want to raise as much money for the TMF as possible. They are a great organization, and I want to support them. Even after my retirement from long runs, I hope to be able to help support Team McGraw in the future.

I love the concept that I can be the poster child for the idea that anyone can run. Two years ago I was forty pounds overweight and had never run longer than a slow 10K before. If I can run a marathon, then anyone with enough desire and dedication can do it. If that can help motivate other people to strive for things they previously thought were out of reach — just like Tug and Valerie have helped motivate me to strive to lose weight and run marathons — that would be an incredible thing.

You’re about two-thirds of the way to your fundraising goal. What does it mean to you to have elicited so much support from so many different people?

It’s very touching to have received so much support from so many people. Obviously some of it is the result of having picked the right charity to run for — so many people love Tug and want to honor his memory. But it also means a lot that people are supporting me as well. It gives me extra motivation to train seriously for this, because I don’t want to let down all of these generous people!

Finally, the wristband and “Faith and Fear Nation” was all your idea. We’re honored to come along for the run, so to speak, and talk it up, but why us?

Why not you? Well, as you pointed out in “The Wrist of the Story,” I did get the idea from Stephen Colbert and his Colbert Nation. Since I know you’re a fan of The Colbert Report, I figured you’d appreciate the reference. Plus we had discussed the fact that you and Jason would help publicize my fundraising efforts throughout the baseball season, which is something I appreciate very much. It dawned on me that the wristband would be a nice way for me to thank you guys for your support.

Plus, again, running for the Faith and Fear Nation provides me with even more incentive to take my training seriously so I can finish the Marathon and earn that medal!

If you would like to support Sharon Chapman’s efforts on behalf of the Tug McGraw Foundation, please visit her fundraising page. Any and all contributions are greatly appreciated.

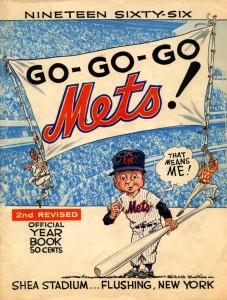

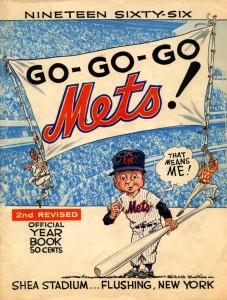

by Greg Prince on 10 February 2010 10:55 pm  The seventh installment of the critically acclaimed (by us, anyway) Mets Yearbook series debuts Thursday night (2/11) at 7:30 on SNY. The year in the spotlight is 1966, the first season in Mets history that was merely bad and not horrific. Of course, everything is relative. A 66-95 ninth-place finish sounds garden variety wretched, but consider this was the first time the Mets didn’t lose at least 109 games and didn’t finish last. A 16½-game turnaround is nothing to sneeze at in any league…even its second division. The seventh installment of the critically acclaimed (by us, anyway) Mets Yearbook series debuts Thursday night (2/11) at 7:30 on SNY. The year in the spotlight is 1966, the first season in Mets history that was merely bad and not horrific. Of course, everything is relative. A 66-95 ninth-place finish sounds garden variety wretched, but consider this was the first time the Mets didn’t lose at least 109 games and didn’t finish last. A 16½-game turnaround is nothing to sneeze at in any league…even its second division.

The propaganda value of improving from 50-112 to 66-95 should prove outstanding. And it’s gotta beat shoveling snow. As a bonus, SNY follows up this world premiere with reruns of Mets Yearbook from 1975, 1976, 1968 and 1984.

Image courtesy of kcmets.com.

Please join Frank Messina and me on Tuesday, February 16, 6:00 PM, at the Cornelia Street Cafe in Greenwich Village for a night of Mets Poetry & Prose. Details here, directions here.

by Greg Prince on 10 February 2010 10:07 am  It’s September 2009. The last thing I want to do is give the Mets more of my money. But there I am, at Citi Field, in the team store browsing, when I see a sign advising me that player number t-shirts are on SALE. It’s September 2009. The last thing I want to do is give the Mets more of my money. But there I am, at Citi Field, in the team store browsing, when I see a sign advising me that player number t-shirts are on SALE.

See, this is why I’ll never be an effective participant in a boycott of all things Wilponian. The desire to support this ownership group’s product is Pavlovian. No, actually, it is Simpsonian. Homer Simpson couldn’t resist a half-price sale on chocolate even though he was already (in his imagination) in the Land of Chocolate, where everything was made of chocolate and he could take a bite out of everything without dropping a dime. I live in the Land of Met t-shirts. I don’t need any more, not at the tail end of 2009 when I’m far more fed up with the reality of the Mets than I am in love with the concept of the Mets. But there is a SALE — $28 marked down to $16 — so I could feel myself stepping up my browsing whether I wanted to or not.

Where do I go with this with this 40% or so discount? Who don’t I have? What’s available? The most plentiful inventory is for injured Mets.

Lots of PEREZ 46. I pass. It would send the wrong message that I’m in favor of his $36 million contract; should Omar see one fan in PEREZ 46, he’ll sign Ollie to an extension.

Lots of MAINE 33, too. I could have gone for one of these in 2007, but how do I know he’ll be back in 2010? I don’t feel nearly enough for Johnny to become a MAINE 33 martyr if he’s not on the team.

An ample supply of SHEFFIELD 10…I might have jumped in May when I was briefly enchanted by his presence, but it’s clear Sheff will not be cooking here much longer. And I’m no longer enchanted.

I look to see if maybe there’s SANTOS 9 available, but an investment in SANTOS 9 seems an invitation for fate to unconditionally release him five minutes and sixteen bucks later.

Then, in blue, with that neat-o alternate inaugural season logo (the one with the rendering of the Rotunda, not the unspeakable Domino’s ad), I see what I want: REYES 7. I don’t just want REYES 7. I need REYES 7.

By September 2009, I need REYES 7 more than I need a t-shirt that says that.

No shortage of JoseWear in my drawers at home, mind you. There’s a blue REYES 7 from 2003, his rookie year. There’s an orange REYES 7 from early in the ’07 season and a black National League All-Star REYES 7 from that same summer. Though I officially condemn the existence of the World Baseball Classic, I added a Dominicana REYES 7 last March. So I’m pretty well set. But staring at REYES 7 in concert with the faux patch that links him to 2009…yes, it will make a handsome addition to my apparel library (as would, given that I’d just theoretically “saved” $12, the REYES UNIVERSITY tee over on the next rack that I snap up as well).

How much better would have the Mets been in 2009 with Jose Reyes playing his customary 153 to 161 games instead of the 36 to which his right hamstring limited him? Would have they been better than 70-92? Would they have been markedly better than hopeless, which is what they were not long after Jose limped away from the scene of the grisly accident that last season was? An extra 120 games of Jose Reyes and concomitantly less Cora, Martinez, Valdez, Hernandez, whoever playing short…I don’t need to check Wins Above Replacement to know that a lot more Jose would have made some kind of difference.

All things being equal, there may be no worse position from which to lose your regular player than shortstop. I base this assertion on two very strong sets of recollections.

• Whenever Bud Harrelson missed copious amounts of time, the Mets seemed to tangibly suffer.

• Whenever Rey Ordoñez missed copious amounts of time, the Mets seemed to tangibly suffer.

No disrespect to the likes of Teddy Martinez, Mike Phillips, Luis Lopez or Melvin Mora, all of whom put in yeoman work as fill-ins in seasons when Harrelson and Ordoñez were shelved by injury for lengthy periods, but a top-flight shortstop never seems easily replaced. At their peak, Harrelson and Ordoñez vacuumed up everything in sight — and in Ordoñez’s case, everything in general. Neither of these guys was an offensive force in the Ernie Banks or Cal Ripken mold, but you didn’t care what they hit when they were in the field. A ground ball at or near Buddy or Rey-Rey was one less thing for the pitcher, the manager and the fans to worry about.

Same could be said for Jose, except Jose at his best extended his anxiety-clearing qualities to the plate and all over the basepaths. In any given game from 2005 through 2008, he had a pretty good shot at being the Mets’ best all-around player. As a classic catalyst, he was unmatched in Met annals. Tommie Agee was power plus speed for a couple of great years as a leadoff hitter. Mookie Wilson could be literally unstoppable on the basepaths (see Mets Walkoffs for just how unstoppable). But Jose Reyes…you know what he was when he was playing every day for four years.

Yeah, you know what I mean.

Subtract that Jose Reyes from any team, and it’s going to show. It was easy to forget as 2009 ground on, given that everybody was injured. It all became one big clump of missing players. Thus, it wasn’t until I stared at that t-shirt that the lack of Reyes in our midst really struck me. There had been so little intertwining of 2009 logos and Jose Reyes. He was the missing person, the kid who was absent when they took the class picture. I didn’t realize how much I missed him while Cora & Co. kept his position lukewarm.

I also glossed over it because of a nagging suspicion that Reyes had stopped being the Reyes I loved toward the end of 2007 and never really recovered his total Joseness thereafter. I know he put up numbers in ’08 that fit in nicely with what he’d been doing since emerging as a full-time player in ’05, but something was always just a little off once the rest of the world discovered how great he was. Not as off as the entirety of Wilson Valdez or Anderson Hernandez, mind you, but askew enough to diminish my innate Jose-loving ways, no matter how many REYES 7 t-shirts I kept wearing. He stopped hitting down the stretch in ’07. His stolen base total froze. He’d choose odd moments to not run to first or to throw tiny, unflattering tantrums. About the only thing I remember well about Jose actually playing in 2009 was the game-winning homer he thought he hit against Atlanta in the twelfth inning on May 13, the one that Citi Field’s daffily designed dimensions kept in play. Had Jose run out of the box, he’d have been on third easily. He broke into a trot and settled for second. The Mets lost by a run.

A week later he was day-to-day, which, per Met medical procedure, kept him out for the rest of the season. Somewhere between May and September, as the ’09 Mets numbed my nerves, Reyes was just another DL casualty in a lost campaign. Since September and that t-shirt, however, with every interview he’s given, every interview somebody else has given about him and every stride he’s taken toward — fingers crossed tight — full recovery, he’s become to me what he’d been since 2003:

My favorite player.

It dawns on me now one of the reasons I found 2009 so toxic, besides the losses and the severe and appalling lack of fundamental baseball skills applied by the Mets in compiling those losses (as their manager and coaches looked on with apparent disinterest), was I had no favorite player to get behind. I had Mets, sure, and I generally root for all Mets. I always find myself rooting a little extra hard for a while for somebody new (like Santos), somebody familiar but new to us (like Sheffield), somebody struggling gamely against adversity (like Maine) and sometimes somebody whom I couldn’t bring myself to completely turn against no matter how compelling the evidence that I should cut bait (like Perez). I was delighted to have Frankie Rodriguez on board. I deepened my admiration for Carlos Beltran before and after his absence. David Wright by now is part of the skyline logo. He’s a landmark. It’s easy to overlook the Woolworth Building, but you still have to root for it. And I do.

But none of them was Jose Reyes to me. None of them was my favorite player. I don’t care how long you’ve been at this rooting thing. You need a favorite player.

Tom Seaver carried that title for me as long as he was a Met or a Met in exile (and, of course, always will in the all-time sense). There was Tom Seaver and everybody else from ’69 until the middle of ’77. I made do with the Mazzillis and Hendersons during the interregnum, but Seaver was my favorite player even when he was a Red.

It took the second idiotic banishment of Tom Terrific and the rise of Doctor K to effectively replace him on a going basis. Dwight Gooden was my favorite player from ’84 until the middle of ’94. Then he was gone, and I was adrift, albeit for only about ten minutes.

Very quickly, I adopted Rico Brogna, who got me through the strike and had me revved up for when baseball returned in ’95. Rico was my favorite player until he was traded just before Thanksgiving 1996 (which gave Thanksgiving a bad name around here for the next decade).

Edgardo Alfonzo came out of the shadows under Bobby Valentine in early 1997 and immediately cemented his place as my favorite player until he was allowed to walk away in December 2002. Not unlike Seaver in Cincy, Fonzie in San Fran retained his ranking for a while thereafter.

I couldn’t handle a long-distance relationship, though. I needed a Met as a favorite player. Not that Fonzie wasn’t still a Met at heart, but I wasn’t about to leave my heart in San Francisco. June bloomed soon enough and, with it, Jose Reyes was brought up from Norfolk. Steve Phillips said it was going to be temporary. Steve Phillips says a lot of things I wouldn’t trust. Reyes was here permanently from June 10, 2003. By June 12, 2003, Steve Phillips was asked to remove himself from his place of employment.

I’d say both were the right call.

Reyes won me over right away, partly because I was dying to be won over, partly because he his good notices from the minors didn’t seem out of line with what he was presenting, partly because he just beamed from the outset. That’s a kid who loves to play baseball, I thought. Loves to play it and can play it well. A little raw, but he just turned twenty. Who wouldn’t be raw that young? It wasn’t a tough consumer decision when I wandered into the Mets Clubhouse Shop on 42nd Street and bought my first REYES 7 in July of ’03.

I was horrified when Jose ended his season in a heap of pain at second base in 2003. I was insulted when he was shuttled to the same base in the spring of 2004 in favor of Kaz Matsui, the Toyota of his time (a big-time Japanese brand whose operating problems should have kept it off the road well before its recall). I was horrified when I saw what the Met braintrust had done to Jose’s beautiful stride after he rehabbed from injury. I was protective of his ascent in 2005, irritated no end when so-called experts snorted that Jose Reyes didn’t walk enough. Not walk? Why walk when you can run like that?

When it all came together in the heart of the 2006 season, when the Mets were becoming Jose Reyes and the Mets…wow, that was gratifying. He was a celebrated prospect a few years earlier and now he and Wright and the rest of the Mets were celebrating a division clinching and a bright future. I loved that my favorite player was the favorite player of so many Mets fans. I loved the serenading. I loved that there were about as many home runs as triples, and there were plenty of triples. I loved the All-Star selections, particularly his moment with Willie Mays in 2007. I hate the WBC, but I loved that his shortstop-rich country thought enough of him to make him a part of its team. Even as I found myself occasionally disappointed at how Jose was playing and acting, I loved him. He was my favorite player. You gotta have a favorite player. Baseball’s not the same without one.

My favorite player is coming back. I look forward to wearing my heart on my sleeve along with his name and number on my back.

And speaking of welcome comebacks, Mike Steffanos is returning to the blogging beat after a winter’s hiatus. If I didn’t see all that snow outside my window, I’d swear spring is right around the corner.

Also, another Mike is reportedly returning. Congratulations to our longtime commenter Jacobs27 for maintaining the same screen name since Mike Jacobs’ departure. Talk about keeping the Faith.

by Greg Prince on 9 February 2010 2:13 am I have lost and I have won, losing isn’t any fun. Rain is fine, but when it’s done — sun is better.

—Edward Kleban, “Better,” A Class Act

The Saints were coming, I read Sunday morning. A couple of days later, the Saints are still going, while the Mets will be here soon enough. Excellent news on both counts.

Unlike Jason, I have no particular attachment to New Orleans or its world champion football team. I visited on three business trips in about a nine-month span not quite ten years ago and — a run of several splendid Hurricanes notwithstanding — nothing much happened to me there. A cab driver did engage me in baseball talk upon seeing my Mets jacket, but I can’t say it was a momentous occasion.

Still, I’m glowing the reflected glow I glow when a team that hasn’t won before or in a very long time has won. It’s the kind of result for which I instinctively pull when a team I call my own isn’t involved in a championship round. The ’01 Patriots, the ’02 Angels, the ’02 Buccaneers, the ’04 Red Sox, the ’05 White Sox and now the ’09 Saints all grabbed my temporary allegiance out of what I consider decent sports fan empathy (and, in the Saints’ case, reasonable human empathy for New Orleans). When each of them won, I felt very good…not frontrunner good, but rather “it’s about time the world proves it can be fair” good.

The Saints winning the Super Bowl was the first professional sports championship to be decided since the World Series ended ignominiously in early November. Football beat baseball in this matchup. What would you rather witness: a perpetually downtrodden franchise get off the schneid or somebody/anybody spill tears over a 27th ring? The only thing wrong with the Saints’ celebration Sunday night was a crowd shot from the French Quarter: thousands of happy, deserving fans and, blighting the bliss, one idiot in a Yankees batting practice jersey. Go home and count your rings, buddy. You’re not wanted anywhere people who have waited an eternity are finally being rewarded.

Naturally, the inclination here is to translate that temporary goodwill from the Saints (or Bucs or White Sox, et al) to where it really and indelibly counts by our reckoning, to the Mets. Hence, one is left once again to remember what it was like the last time the Mets won a championship and, more so, imagine what it will be like the next time the Mets win a championship.

That’s what it’s all about. When you’re between or before championships, it’s about everything else, and everything else offers plenty of valid rewards. But a night like the one Saints fans will be experiencing for the next month is the end zone for every football fan and home plate for every baseball fan. Don’t kid yourself. As great as a pretty good season can feel, and as enormously as a nearly great season might loom, World Champion New York Mets is the Holy Grail. It’s not shallow to want it above all else and it doesn’t expose our character as anything less than sturdy to admit it. For all the secular spirituality with which we approach our fandom, it’s impossible to ignore there are wins and there are losses. The wins are the desirable part. The championship is the most desirable.

The losses you can keep.

Sports fans, Mets fans included and maybe in particular, often act in a counterintuitive fashion when it comes to losing. Of course we hate it. Of course we don’t want to go through it. Of course when we’re stuck in its rut, we endlessly strategize methods to eliminate it. Yet god help anyone who would deny us claim to the losses that have been accumulated on our ledger. Those are our losses, damn it, and don’t you dare question our purity for having endured them.

At the risk of being overly judgmental of people whose heads I cannot possibly be inside (or, in one obvious case, have no desire to get anywhere near), it’s safe to say fans of the following professional sports teams have forfeited any claim on long-suffering status:

• The Saints

• The Yankees

• The Lakers

• The Penguins

Those are the defending champions in their respective realms. Their fans are fine until they’re not (except for the Yankees fans, who are sated for life, no matter how many World Series Don Mattingly didn’t win when they were kids). If you root for the runners-up to those champions — the Colts, the Phillies, the Magic, the Red Wings — I’d estimate that you’re exempt from long-suffering status for now as well. We’d like it if the 2009 World Series-losing Phillies fans were as long-suffering as they claimed to be prior to 2008, but given that they won it all two years ago, we’ll have to settle for knowing the Delaware Valley was deluged by snow over the weekend and Phillies fans were among the immensely inconvenienced. Colts fans see their team win 12 games every single year and enjoyed one championship a mere three years ago. A tinge of frustration might be setting in, but that’s not suffering in the wider fan vernacular.

If we consider championships Holy Grails and everything else killing time, we could probably extend this exercise clear back to the 1908 Cubs and eventually decide their fans take the suffering cake and deserve the biggest, most empathetic trophy of all — unless your impression of the Cubs as a bunch of preening bullies was formed as a six-year-old Mets fan in 1969. In that case, every time someone runs the Steve Bartman clip, your smirk demonstrates a mind of its own. This is why patterns and formulas will only get you so far in calculating who can kvetch and moan the most. Not a Mets fan who was watching Terry Pendleton take Roger McDowell deep on September 11, 1987 was thinking, “aw heck, that’s OK that we just missed our big chance to move within a half-game of the Cardinals — we won last year.” There’s no point in trying to look at sports in an unbiased fashion. Rooting is nothing if not an expression of permanent bias.

Every fan has to decide for himself or herself what’s really painful and what’s just not winning. Though I’ve just kind of told Colts fans to take a hike (and maybe not run the ball as the clock winds down), nobody can define your suffering for you. The Great Bill Simmons recently threw the kitchen sink at trying to decide what fans have been tortured more than any other. Per usual for the man who essentially invented sports blogging, his effort was very entertaining but irritatingly overreaching. Simmons’ rankings and system are neither here nor there — he goes with the Cubbie legions as No. 1 among the most put upon — but what’s really revealing is the responses he received from those he didn’t place in his Top/Bottom 15.

For example, Simmons ranked the Minnesota Vikings second and the Detroit Lions not at all. The Vikings, you might recall, almost made this year’s Super Bowl, losing the NFC championship on an overtime interception. They almost made the Super Bowl eleven years ago, losing on a missed field goal as time expired. I looked it up and discovered the Vikings have made the NFL playoffs 26 times in the past 43 seasons. They’re 0-for-26 in attempting to win a Super Bowl from there. Sounds reasonably tortured, right?

Screw them, wrote in a Lions fan, roaringly offended by Simmons’ blithe dismissal of his pain:

“What more do we have to endure? We haven’t won more than one playoff game in a season since the merger. Most Lions fans would KILL to lose four Super Bowls, or even make it back to the NFC Championship Game. We’re jealous of Vikings fans.”

While Simmons gave his benediction to fans of the Cubs, the Vikings, the Bills, the Browns, the Indians and ten others, loads of other fans from the four major sports were disappointed they didn’t get the call and wrote in to tell him so — fans of teams that have Viking-like luck when the clutch overcomes them as well as fans of Lionesque franchises that disappear down the competition hole for decades at a time. If we’re gonna have to lose, one can infer from the reaction, at least give us credit for having lost memorably and painfully.

This is frontrunning in reverse. This is backpedaling into a brick wall.

I don’t know that I necessarily want a piece of this type of action. I can, and I have, sat here this winter and attempted to quantify the downer quotient of being a Mets fan these days. For example, you know it’s been 24 years since a world championship has been celebrated by the deserving citizens of Metsopotamia. Esteemed blolleague Matt Artus of Always Amazin’ noticed quite recently that we are in the midst of the 14th longest World Series drought in captivity; 14 teams have gone longer than we have without a title and two that didn’t exist on October 27, 1986 have yet to win one. I can add to this cavalcade of despondency that:

• We are no longer in the upper half of the big leagues in terms of recent playoff qualifications, which in itself is no crime, but also indicates how long ago, all of a sudden, 2006 was. Fifteen teams have played a postseason game since the Mets last did, on October 19, 2006…which, in case you’ve forgotten, ended with three Mets on base and three strikes on Carlos Beltran.

• Should the Mets by some chance make the 2010 playoffs, and our first playoff game is played the Wednesday after the Sunday when the regular season ends, 1,447 days will have passed since 10/19/06 and that nasty curveball from Adam Wainwright.

FYI, a recent viewing of the bottom of the ninth inning of Game Seven on MLBN indicates Wainwright had that curve working hellaciously against Floyd and Reyes, which I swear I didn’t notice the night it happened or in January 2009, the first time I watched a replay of the game (when I think I was still reeling from the idea that I was watching this stupid game all over again). This third viewing and first really good look has changed my default “Beltran knew what he was doing taking” stance from 1,209 days ago to “how the hell could have he not been protecting the plate?”

Either way, it’s still too long since the Mets have played a postseason game. Just because the Royals have gone a lot longer and the Nationals have yet to play even one doesn’t make our wait seem any shorter.

• The Mets have been to four postseasons since 1986 and have not won a World Series in any of them. It’s hardly the stuff of Vikings…or the Phoenix Suns, 28-time NBA playoff qualifiers yet never champions…or the NHL St. Louis Blues, whose 35 trips to the Stanley Cup Playoffs have sent them home without a Cup every time. It’s also not quite Cubbish — 13 postseason appearances after 1908 with no winning it all — nor is it what happened in Atlanta after 1995: ten consecutive playoff appearances, no more world championships (shucks).

Even using life after 1986 as the baseline, we don’t have it as bad as others where October futility is concerned. Beginning with October 1987, the Indians (7), Giants (6), Astros (6) and Cubs (5) have all made more playoff appearances than the Mets and come away completely emptyhanded. Of course we don’t care that much about any team that isn’t the Mets, so four lousy playoff appearances over 22 seasons (not counting 1994 when there were no playoffs) and no stilted handshakes from Bud Selig…while it’s not the worst showing in sport, it’s more than a little disturbing when you’re immersed in the quest for that Holy Grail.

Baseball is still more selective than the other sports in inviting teams to its tournament, so there is a specialness to just being there, even without a big parade to cap it off, even with crash-landing endings like those that ultimately defined 2006 and 1988. The holy-ish grails can do a nice job of distracting you, particularly if there are 1999-style dramatics or a couple of rounds of victories as there were in 2000 before the shadow of defeat eclipsed every happy thing in our midst. Though we haven’t paraded up Lower Broadway in nearly 9,000 days, it’s not like we don’t drop a little drama on our way out of tournaments.

• Nearly 9,000 days, you ask? On the 8,702nd day of my life, the New York Mets defeated the Boston Red Sox 8-5 to capture the 1986 World Series. This July 24 will mark 8,702 days since that moment. On July 25, 2010, I will, therefore, have lived more than a half a lifetime since the Mets were last crowned world champions.

Yeah, I could do this sort of cheerful accounting all day, and sometimes I have to stop myself from doing just that. It’s easy enough to get caught up in fan hardship. It’s a perceived badge of honor to say we were around when the team was losing, so that when the team wins, we can show off the texture of our bona fides. There is no doubt that nights when you clinch something are a lot more meaningful for all the nights you compiled caring about a team that was clinching nothing.

Nevertheless, we didn’t become fans of a team to prove to ourselves and anyone who’ll listen that we have it worse than others whose teams haven’t won lately or ever. That stuff only sounds good once you’ve won and it’s all in your colorful past.

The Saints’ ascension and their accompanying mythology revived the legend of the paper bags. Paper bags, you were probably reminded along the Super way, became de rigueur in New Orleans in 1980 when the so-called Ain’ts lost 14 of their first 14 games en route to their 14th losing season in 14 tries. If anybody could make paper bags look sharp, it was the Saints fans. It’s not something anybody else would be advised to try on for size.

Seeing the inevitable montages of such Saintly images from New Orleans’ notorious football past eventually brought back to mind the dope I noticed lingering in Shea’s Upper Deck on Collapse Day, 9/30/07. The final game of the season several minutes over, he was wearing a paper bag on his head and shouting “I’m embarrassed to be a Mets fan!” I was embarrassed he was a Mets fan, too.

Listen, that day sucked. As stunning culmination of a 7-game lead blown in 17 games’ time, it sucked more than Beltran taking Called Strike Three, which at least followed a division title and a division series sweep. I was disgusted with every Met who lost 8-1 that Sunday, but I still couldn’t abide the paper bag guy as a symbol of our so-called suffering. Besides it being derivative of another team in another circumstance in another era in another sport, why would a Mets fan hide his head? It was bad enough the players and manager had hidden theirs up their collective rear end. What was this guy proving? That he was suffering? That the Mets did something so heinous to his identity that he now had to obscure it?

I don’t particularly expect us to stop being a non-juggernaut in 2010. Still, I don’t want to get caught up any more than I have to be in the Mets’ lack of successes. We’ll report them, analyze them, comment on them, rue them and, perhaps as a defense mechanism, mock them as applicable, but I’m not going to bask in them. I’m not going to go the Bitter Bill route and constantly moan about all the wrong the Mets are doing me. Bill Price, like Bill Simmons, can be quite amusing and fairly sincere in his shtick, but the Mets fan as tortured soul bit (which fits well into the Daily News Yankee-worshipping narrative, doesn’t it?) feels more forced than genuine.

Suffer? The Mets? Baseball? In the words of Gob Bluth (the Jeff Wilpon character in Arrested Development), come on! It’s the game we love, the affiliation we embrace, the camaraderie we adore. Why do you suppose so many of us mourned the loss of Jane Jarvis? Why were we insistent that the Mets open a Hall of Fame? Why do we treat the countdown to Pitchers & Catchers like a prisoner scratching days interred into his cell wall? The day-by-day of baseball in all its reassuring rhythms, its infrequent rewards, its small disappointments, its debilitating devastations and its 162-part comic drama is a prize unto itself. Maybe it’s not the Holy Grail, but it’s not a bad set of dishes, either.

No, this isn’t suffering. This is what we willingly live for. This is not the suffering portion of life. Sometimes (or a lot of the time) we are prevented from exulting to our maximum capability by front office negligence or an uncertain starting rotation or somebody else’s unhittable curve, but it’s still the good part of life.

The Mets can let us down, but only we can make ourselves suffer. Why, exactly, would we want to do that?

Please join Frank Messina and me on Tuesday, February 16, 6:00 PM, at the Cornelia Street Cafe in Greenwich Village for a night of Mets Poetry & Prose. Details here, directions here.

by Jason Fry on 7 February 2010 12:07 am In a few short hours the New Orleans Saints will play the Indianapolis Colts in the Super Bowl.

I bet you remembered that.

Four and a half years ago, Hurricane Katrina gave the city of New Orleans what can be described as a devastating near-miss. The city was spared the direct hit from a powerful hurricane that had long been feared in a place largely below sea level, but failed levees flooded it nonetheless, leading to a disaster marked by terrible human suffering, anger and anguish and searing visuals beamed to a shocked country.

I bet you remembered that too.

The once-lowly Saints’ march through the NFC South and the playoffs has been accompanied by something else: Katrina fatigue. On one level, this is completely natural. If we haven’t already given our hearts over to a team, we turn reflexively cynical when we hear the stentorian tones of sports announcers trying to channel epic seriousness to describe the outcome of a contest between a bunch of young men running around on an athletic field wearing motley. When Fox or CBS or ESPN gets its Ken Burns on and shows black and white pictures accompanied by mournful music, we dig in our heels, because we know soon enough there will be martial music and fireworks and CGI logos and the whole rest of the routine sports show.

I get all that. But I’m asking you, on the doorstep of this Super Bowl, not to be jaded. I understand what motivated all those people who responded to Garrett Hartley’s kick against the Vikings by groaning about the number of Katrina columns they’d now have to endure for two weeks. I know that the miseries of Katrina are not going to be magically remedied by flights of fancy from knights of the keyboard who watched a little CNN on YouTube. But those people who bemoaned the coming Katrina frenzy were letting the cliché get the better of them. They needed to look past all that, to look deeper.

You’ve probably guessed by now that I am a Saints fan. Though truth be told, I’m really a New Orleans fan. This was inevitable: New Orleans was the city where I drew my first real adult paycheck. It’s where I first lived by myself without the immediate safety net of parents or college administrators. It was the first place I was taught my craft, was treated as an adult, had to figure out grown-up stuff on my own, and succeeded tolerably enough at all of those things to give me hope that I might find my way through. (And, a summer later, it’s where I’d meet my wife.) Even if it weren’t one of the world’s greatest cities — which it most certainly is — that would be enough to grant New Orleans a lifelong place in my heart.

For me the Saints were and always have been secondary to New Orleans. I’m a half-assed Saints fan by any real measure. I can moan about Bobby Hebert and John Fourcade and Jim Everett, but this isn’t real knowledge or real suffering. I can’t name all the guys on this year’s team, or most of them, or even an acceptable percentage of them. If the Saints lose, I will be sad for a couple of hours and wake up on Monday morning thinking about spring training and complaining about Omar. I have nothing against the good people of Indianapolis. I think the Colts should be admired for the scientific way they approach rosters and strategy and the consistent excellence they achieve. I give Peyton Manning credit for having grown up with a preordained spot as an NFL quarterback and still managing to be mildly interesting. All things considered, my stake in this is pretty small.

But like I said, I am a New Orleans fan. And as one, I’m asking you to try and step back, to listen again to what you’re tired of hearing about, and to consider two things.

First of all, Hurricane Katrina did not happen in another century or in a world so technologically different as to seem apart from us. The most powerful, technologically advanced nation on this planet saw a storm drown one of its oldest and most-famous cities and proved astonishingly impotent at providing its own people the basic means of survival in a timely, organized fashion. More than 1,800 people died, most of them in the houses and neighborhoods they held dear, killed by an impersonal enemy no ideology or army will ever be able to conquer. More than four years later, whole swaths of the city remain unrecognizable, with decades of families and stories literally washed away. Bourbon Street may stagger happily along, but New Orleans will never be the same. Neither, I would argue, will the United States of America. Regardless of whom you voted for or what political creed you profess or how you assign blame, Katrina matters. What happened in New Orleans in 2005 pierces the uncomfortable heart of whatever we think about race, about class, about the proper role of government, about the possibilities of technology, about the demands of personal responsibility, about fairness, about bias, about faith, about luck. Those who live far from New Orleans will find it bound up in their arguments about these things for decades. Those who live in New Orleans will never escape it.

Which brings us to the Saints.

I know, it’s a cliché to talk of cities rallying around a team. But in New Orleans, the Saints cast a spell that it’s hard for us to grasp in our pick-an-allegiance, this-one-or-that-one metropolis of many sports and choices. The Saints command the affection and allegiance of New Orleans’ gentry and its destitute alike, as they have in good years and bad. And in the immediate aftermath of Katrina, it seemed all but certain that the team was gone for good. Katrina punched holes in the Superdome, where as many as 20,000 sought shelter from the storm in the heat and filth. While the tales of horror in the Superdome proved wildly exaggerated, six people did die there. Meanwhile, the Saints had decamped to San Antonio, where their owner had made his fortune selling cars. Negotiations were under way for the team to relocate permanently. What were the chances the team would return to a wrecked stadium in a ruined city whose population had largely dispersed? We’ve been through a lot as Mets fans, but for all our woes, we’ve never even endured or even imagined anything close to that.

But the Superdome was repaired, and the Saints returned. They have been led by players and a coach who have embraced the city and its people, and not just in the way a millionaire pitcher embraces, say, the idea of commuting from Greenwich and occasionally hitting a museum or an expensive restaurant. A few months after Katrina, former Chargers quarterback Drew Brees was picking a new professional home. His choices were New Orleans and the undestroyed precincts of Miami. Newly hired head coach Sean Payton drove him around the city, took a wrong turn and wound up giving a horrified Brees an extended tour of the ruins. Brees, amazingly, chose the ruins. He has given millions to the effort to get the city back on its feet, and he is far from alone. Many Saints players have done the same.

The Saints are close to religion in New Orleans. In that city’s darkest hour, it seemed certain that they too would be taken away. But they returned and endured, and now shine more brightly than they ever have. All the hoary old maxims about the love of a team making a city whole? They’re said in cities that don’t need to be rebuilt, and they’re no more true in New Orleans than they were in those places. If Brees and Payton lead the Saints to a Super Bowl victory, no houses will spring back to life in the Lower Ninth Ward and no levees will be made strong enough to resist the next storm. But the idea that the Saints have bound up the wounds of a city and its people and given them something to love and cheer for and believe in when there’s been very little else? That’s absolutely true, and it’s been desperately needed in ways most of us, thankfully, can only imagine.

The problem with a cliché isn’t that it’s inaccurate, or a poor turn of phrase, or fails to capture the reality of something. Rather, it’s that a cliché does those things too well, and therefore is employed so often that it becomes empty and shopworn. Every cliché hides in plain sight something that was new and valuable before we got used to it. So don’t get used to it. Don’t let media overkill make you numb to Katrina, or dismissive of the idea that the Saints really do mean something more to their fans than what we’re accustomed to.