The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 6 November 2023 12:02 pm Whether it was out of quaint National League loyalty, appreciation for vanquishing the Phillies, or a fleeting fancy born of the whims of October, I was an Arizona Diamondbacks fan for five nights in the World Series, extending the quick hop I made aboard their slithering bandwagon during the NLCS. An interim fan, you might have called me. It didn’t work out in terms of a burst of vicarious championship satisfaction, but I was glad enough they were my team for a week or two (Brent Strom’s unbecoming September crankiness toward a Ford C. Frick Award nominee notwithstanding). They played good Diamondbacks baseball for as long as they could, moving runners over and the like; they were young and athletic, with a dash of experience to provide a little faith that they knew what they were doing. I didn’t know much about the Diamondbacks before the postseason. I was happy to make their acquaintance until, inevitably, I reverted to not much caring about them.

But it helps to have a rooting interest if you wish to be engaged by a Metless tournament. By Game Five of the World Series as Arizona tried to hang on for dear life, I believe I was rooting less for the D’Backs and more for more baseball. There was a ground ball as the middle innings were becoming the late innings that I really wanted to see reach the outfield but didn’t. C’mon, keep going. That grounder was carrying within its stitches my hope that the postseason would keep going, too. A month since they made their last out, I hadn’t missed the most recent edition of the Mets whatsoever, but I did feel a void when November baseball expired ahead of its allotted time frame.

The Texas Rangers dictated the World Series would last no more than five games, just enough to escalate onlooker interest by a tick. Our last two World Series of surpassing Metsian concern, in 2000 and 2015, teased us during fifth games that a sixth was somewhere between probable and possible, and if we could get a sixth game, who was to say there wouldn’t be a seventh? In 2000 and 2015, it was the Mets’ opposition answering that question. Winners of Game Five who enter said competition up three games to one too often write the history…though we didn’t mind that in 1969.

Despite cheering on their opposition like I meant it, I found nothing to dislike in the Rangers, an affable and talented bunch with a few faces fairly familiar to us lurking in the shadows. Goodness knows those who truly cared about them had waited long enough. A first-time/long-time world championship for a franchise — whether actually its first or the first most any living fan of that team has experienced — should be a cause for sportwide celebration, fans affiliated with the losing side excused if they’re not feeling the love. I watched a bit of the Rangers’ parade through the streets of Arlington. I imagine some in the crowd were simply big proponents of success and celebration, but you know plenty lining the sidewalks had waited what was, for them, forever. In the context of Texas Rangers baseball, transplanted from Washington in 1972 and proceeding ringlessly until Wednesday night, it had been forever.

Although I was on the side of the Diamondbacks, I could not see those shots of the Rangers dugout where their manager stood tall and not be all for Bruce Bochy. I rallied around the skipper during the Giants’ three World Series conquests in the previous decade and never developed any animus for the man despite his sending Madison Bumgarner to shut us out in the 2016 Wild Card Game. “Boch,” as they call him, just seems to have a feel for what needs to be done in any situation, whether it’s leaving a MadBum into finish a seventh game as he did versus Kansas City nine Series ago, or plucking an umpteenth reliever from the mound despite a seemingly unblowable lead and going to his closer to put the hammer down, which he did in Game Four this year when he replaced Will Smith with Jose Leclerc (Leclerc gave up a hit that made things a little closer, but in the end it worked). Every Ranger pointed to Boch’s calmness as the constant that got them through every bumpy moment in the season and postseason, and I could totally see it, especially when Rangers interviewed in the minutes after they eliminated their last obstacle and gained their first ring were cool and collected rather than shouting “WOOOOOOOOOOO!!!!!!!”. After Bochy retired from San Fran in 2019, I wondered if anybody in Flushing thought to give him a call on those several occasions we had an opening. He was apparently lurable and was damn well worth a feeler.

Eventually got a callup. Should’ve been called to manage the big club decades later. Of all within the Texas traveling party claiming Mets ties — idled pitchers Jacob deGrom and Max Scherzer, fill-in right fielder Travis Jankowski (whose performance helped his club remained calm following the injury to otherworldly Adolis Garcia), general manager Chris Young and pitching coach Mike Maddux — Bochy’s connection is both the most ancient and the least outwardly consequential. Bruce spent two years in the Mets organization, in 1981 and 1982, mostly with Tidewater. Perhaps he whispered something useful in the ear of a young Orosco or Darling that paid off long-term. Mostly, he was the guy who got written about in his first St. Petersburg Spring Training for having an oversized head and needing to tote his own batting helmet from team to team, where it would be painted whatever color would allow him to blend in. Bruce scored four runs as a Met. He has exactly that many World Series trophies to his credit now.

What a difference a manager makes. Or so we will allow ourselves to assume, considering San Francisco never celebrated a title until Bochy guided them to the promised land in 2010 (and 2012 and 2014), and North Texas wasn’t the capital of baseball until 2023. We will also wish to assume there’s something to this Leader of Men stuff because the Mets believe Carlos Mendoza is their next difference-maker, one who, if he’s as impactful as can be, will add his name to a very short list. Forty years ago at this time, the list of managers who had made all the difference to the Mets from a world championship standpoint contained only one name: Gil Hodges. That fall, fourteen years removed from the only Mets manager who had ever worked a miracle working that miracle, I don’t know if any of us imagined the newest fella hired to fill Gil’s old office was going to lead us toward a doubling of the names on that list.

The Contemporary Baseball Era Committee recently announced which managers, executives and umpires it is considering for Hall of Fame induction next year. Eight people have been nominated. One is Davey Johnson, whose bona fides reflect winning seasons in Cincinnati, Baltimore, Los Angeles and Washington (with all but the Dodgers earning division titles on his watch), but his ultimate selection would serve mainly as acknowledgment of the underrated work he did in New York. If this committee votes Davey in, it will be because 1986 remains A Year to Remember, but it oughta be as much about what faced him when he took over in October 1983 and how quickly he transformed everything around him.

I don’t know if Davey elevating a moribund major league club toward and eventually to the highest of heights will resonate with the voters. The others they’re mulling (Jim Leyland, Cito Gaston, Lou Piniella, Bill White, Ed Montague, Joe West and Hank Peters) are well-credentialed, too, and certainly each manager in the group can claim an element of franchise-spurring. But I’m gonna be parochial here. I know what the Mets were before Davey, during Davey, and after Davey. I know Davey was difference personified. The Mets were never better as a going concern than they were when Davey Johnson managed them. They were never better in a single season than they were when Davey Johnson managed them, and few teams have been better than his 1986 Mets. In case you hadn’t noticed, the Mets haven’t won a World Series since Davey Johnson managed them.

The distance from the mood at Shea when he took over — and introduced himself to the New York media by thanking Frank Cashen “for having the intelligence to hire me” — to the day slightly more than three years later when Davey and his team accepted plaudits at City Hall measured far more than 13 miles. Davey’s presence at the helm in Queens may not have represented the first mile in zooming the Mets from winning infrequently to winning it all, but he sure accelerated the process, and it’s impossible to imagine anybody else guiding the trip. Should the committee recognize Davey Johnson’s role in turning a perennial loser into one of that generation’s most compelling winners, may the rigors of travel to Cooperstown for the acceptance of a plaque not too many spots from Gil Hodges’s be easy on him.

Right before Johnson began to stamp his eternal imprint on the Mets’ story, the manager who immediately preceded him stepped aside about as gracefully as one could fathom. On October 1, 1983, one day before the Mets swept a Closing Day doubleheader to put the best ending possible on their fifth sixth-place campaign in seven seasons, that Mets manager couldn’t announce definitively whether he’d be with the club in 1984, though he probably knew. All he would allow to reporters was, “I’m sure my boss, Mr. J. Frank Cashen, will show sincerity, generosity and compassion in his decision. I’m sure that whatever happens will happen for the best.”

That last part was right as could be. Davey Johnson coming aboard a couple of weeks later was absolutely for the best. As for the rest, the generosity was all Frank Howard’s. The man was about to be fired as manager of the New York Mets, in that way it is said every manager is hired to be fired. When Cashen broke the news to the media on October 2, the GM said “circumstances” did Howard in, with the Mets’ 68-94 final record a circumstance bound to tower over even the tallest of managers, which the 6-foot-7 Howard surely was. Cashen also said he made up his mind to not retain Howard in September, once the all-but-inactive Dave Kingman declined his manager’s invitation to start a game at first base. Kingman felt like he hadn’t had enough defensive reps recently — and hadn’t worked out at the position much since Keith Hernandez arrived — to acquit himself adequately in the field. Howard chose to respect the veteran slugger’s wishes rather than order him to grab his mitt and get out to first. It didn’t go over well in the front office.

No hard feelings? Howard, Swan and Bamberger intimate all is well on the 1982 Mets. Frank Howard’s title from early June until early October was interim manager. The interim manager was clear on what that meant: “They made me no promises.” Howard was in the job because the permanent manager he served as a coach, the previously retired George Bamberger — who cut short his tenure with the Brewers after heart bypass surgery in 1980 — had enough of the Mets and quit to literally go fishing. Bamberger, a Cashen favorite from their days in Baltimore, never seemed enthused about leading the Mets. He gave it a year and change and, well, never changed. “I was starting to get headaches from the tension,” George said a couple of months later. Howard, on the other hand, never lacked enthusiasm in 1982 and 1983, whether it was running the Jumbo Franks in intrasquad games versus fellow coach Jim Frey’s Small Freys, or setting Craig Swan straight at the end of a road rip when the veteran pitcher griped a little too long and loud about the travel arrangements (Swannie was beefy, but a shoving match with someone 6-foot-7 will make a person who isn’t at least 6-foot-8 change his tone). Frey had managed the Royals to the 1980 World Series, yet Cashen chose Howard, whose managerial record in San Diego was brief and unspectacular, as Bamberger’s successor.

“I have the highest regard for Jimmy Frey,” Cashen said in June, “but felt we needed a strong personality — and that’s why I chose Big Frank.” Translation: somebody who could be described as “jumbo” was more likely to be listened to in a sullen, last-place clubhouse than somebody described as small…even if longtime beat writer Jack Lang sized Howard up as “a giant of a man with the personality of a pussycat”.

With Howard taking over, the 1983 Mets intermittently purred. The young talent, featuring Darryl Strawberry, indicated last place wasn’t going to be the Mets’ residency into perpetuity, and the trade for Keith Hernandez said something about Cashen’s sense of purpose. When he was promoted, Howard said he wouldn’t stand for play that was “indifferent and haphazard”. For a time there was none of that to the team’s approach. Frank Howard’s Mets, at their August best, were vibrant and brimming with promise, as boisterous if not as big as he was, giving a fan the idea that this team was a growth stock. How much Howard and what Lang referred to as his “quiet but driving leadership” had to do with it was in the eye of the beholder. Under their interim manager, the Mets went 52-64, with a little too much coming down to earth to be ignored by September.

Still, the enthusiasm was always in evidence, and when one flashes back to the best parts of the interim summer of Frank Howard, one sees the big man on the top step congratulating his players if they crossed the plate, and clapping for them as long they hustled from home to first. In his 2009 memoir The Complete Game, Ron Darling, a September 1983 callup, recalled his first manager as a “hard charger,” if perhaps a bit over the top. “Frank is pushing for everyone on the club,” young Straw said as he got his feet wet in the majors. “He wants you to give 100 percent. It’s great to see a manager who wants you to give effort all the time” (even if neophyte Darryl didn’t always play as if he fully interpreted that particular message). Howard struck this home viewer as the quintessential upbeat coach in a sport in which people called coaches are assistants; I could never quite wrap my mind around the idea that Frank Howard was The Manager. Maybe his interim status played into that perception. Deciding whether he was genuine managerial timber, redwood stature aside, would be best left to those who got a closer look. Howard never managed again after Cashen removed both “interim” and “manager” from his title. Yet when he was let go, older Mets who’d seen their share of skippers offered only glowing reviews for public consumption.

Tom Seaver: “Frank is a fine man. I can’t think of anybody warmer to play for. His sincerity was tremendous.”

Mike Torrez: “Howard is a good man to play for. He’s an honest man. He gives you the ball and he asks you to give 100 percent.”

Bob Bailor: “I liked playing for Frank. His enthusiasm for the game is unmatched. Especially on a club like this where there isn’t too much electricity in the dugout to start with.”

Rusty Staub: “I enjoyed playing for Frank. I hope something positive happens for him. A lot of people here are going to miss his patience.”

Turns out they wouldn’t have to. Rusty and the 1984 Mets would continue to benefit from whatever Frank Howard brought to the enterprise, as Cashen’s invite to remain in the organization, along with Davey Johnson’s half-throated assent, convinced him to stay on among the new manager’s staff. “I like Frank Howard,” Johnson said about his predecessor. “I like his enthusiasm. I like his energy and I like the fact that he is a good baseball man. I want to surround myself with the best baseball men I can find.” Having apparently taken time out from steering Tidewater to the 1983 Triple-A championship to watch what might affect his 1984 job prospects, Davey couldn’t help but add, “I did not like the way he managed.” When Davey was asked how he’d handle a situation like Big Frank encountered with Kingman, the new sheriff in town responded, “If a player did that to me, I’d tell him to pack his bags and go home.”

Frank Howard kept his bags unpacked for another year in New York, still bringing that trademark enthusiasm, energy and size to the dugout the year the Mets finally turned it around, going 90-72 and finishing 6½ games from first place after leading the division much of the summer. They weren’t quite ready to make the postseason, but they were getting there. When they did, Frank Howard would be in Milwaukee, reunited with Bamberger, who, like Bochy, resisted staying retired from managing. Frank had coached for Bambi when George first ran the Brewers, and baseball men tend to stay in touch with one another.

Clearly, baseball organizations liked having Frank Howard around as a coach, as he’d spend almost every season through the end of the 20th century assisting one manager or another. For three seasons, from 1994 to 1996, he’d be back in Queens, as one of Dallas Green’s Mets coaches. It was an era when the records were losing and the outlook was dim, quite a bit like 1982 and 1983, but Big Frank’s enthusiasm never wavered. Howard had coached for Green in the Bronx in 1989. Like Bamberger, Green knew a good and loyal baseball man when he saw him, and Howard returned the loyalty in kind, not to mention effort. Frank was known, per Newsday’s Marty Noble, as “the foremost workaholic among baseball coaches,” an extension of what Howard asked of his players when he managed them. “The cheapest commodity in our business,” he preached, “is 90 feet.”

Before there was Judge and Altuve, there was Hondo and Buddy. For someone whose Met contribution is chronologically distant and whose Met footprint is admittedly light — when he died at the age of 87 on October 30, amid the Rangers-Diamondbacks World Series, his time as Mets manager was mentioned in passing at most — it says something that Frank Howard’s career was intertwined at least a little with a whole bunch of Mets managers. Played in Los Angeles with Jeff Torborg. Coached for Green and Bamberger and Johnson, as mentioned. Coached alongside Buddy Harrelson in 1982 (separated by a listed eight inches in height and triple-digits in weight, they made quite a picture together), Mike Cubbage in 1994 and 1995 (they could compare notes on their respective experiences as purely interim Met managers), and Bobby Valentine the first two months of 1983 and all of 1984, with Bobby V serving as his third base coach in between.

“It was an honor to coach with and coach for Hondo,” Valentine tweeted last week, invoking Frank’s most commonly referenced nickname. Howard had a few, including the Capital Punisher and the Washington Monument, nods to not only his prodigious power — 382 home runs, enough hit so high and far to inspire the repainting of several seats at RFK Stadium — but his importance to D.C. baseball when he was essentially the lone star of the Senators in the years before that franchise abandoned Washington for the Lone Star state to become the pre-championship Texas Rangers. In paying tribute to him in the Washington Post, Tom Boswell wrote the region’s undying affection for Hondo and continual invocation of his exploits “were a core piece of what kept Washington fighting to get another team.”

The Washington Senators featured Frank Howard once they traded reliable lefty starter Claude Osteen to the Los Angeles Dodgers to have Hondo as their own. On the Dodgers between 1959 and 1964, Howard played some first base. So did another future Mets manager, Gil Hodges. They were teammates in L.A. before Gil returned to New York to play for the new National League expansion club at the Polo Grounds. When Gil had no more playing left in him, he departed for the District to earn his managerial stripes, running a hopeless club and making them a little less hopeless through the mid-’60s. It was the apprenticeship that paved the way for Gil’s immortal difference-making at Shea in 1969.

That part would come soon if not soon enough for Mets fans. In the interim, in the lower reaches of the American League, Hodges had work to do, and he did it best with Howard, changing the slugger’s perspective on how to think about what pitchers were thinking, and, by Frank’s own reckoning, improving his game. “He’s made me a better ballplayer, no question of that,” Hondo said of Hodges while he was building his Monumental résumé in Washington. Howard expanded further on Gil’s influence decades later for Hodges biographer Mort Zachter: “When you manage a marginal club, you really have to manage.”

Frank Howard went to four All-Star Games as a Senator between 1968 and 1971 — “a line drive by Howard could behead someone” was Seaver’s impression after taking stock of him in the batter’s box during the 1970 Midsummer Classic — and earned a World Series ring with the 1963 Dodgers, setting the stage for L.A.’s Game Four 2-1 clincher with his fifth-inning homer off Whitey Ford. After hitting the last home run ever for the Senators in September of ’71, he hit the first home run ever for the relocated Rangers in April of ’72, months before the Tigers scooped him up for the power boost he could provide down the stretch as they outdueled the Red Sox for that year’s AL East title. Yet it was a ballclub that didn’t exist as such when he played, the Washington Nationals, who tended to his legacy in retirement. The Nats unveiled a statue of Frank in front of their new ballpark and inducted him into their Ring of Honor. They would be the ones to announce Howard’s passing, and it was the Nats who made sure Frank was an honored guest when they brought the World Series back to Washington in 2019 after an 86-year absence.

Bogar, Howard and the Met ties that bonded. As Nationals Park public address announcer Phil Hochberg was taking a moment to direct the crowd’s attention to D.C.’s legend emeritus prior to Game Four, Howard, seated on the field and wearing a Nats jersey, received a visit from the home team’s first base coach, Tim Bogar. Bogar was a Met when Howard coached for the club the second time, in the ’90s. Frank was Tim’s first base coach and everybody’s “attitude coach”. The visit was brief but warm. Their bond, forged well before the Nationals moved from Montreal, jumped off the screen like a homer off Howard’s bat. Those Mets where Bogie met Hondo may have been a marginal club, but you always knew Frank Howard really coached.

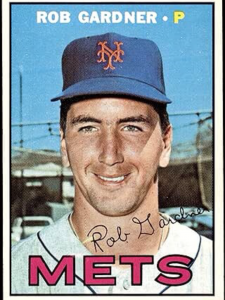

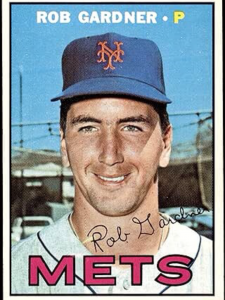

by Greg Prince on 31 October 2023 12:40 pm Atop the annals of below-the-surface New York Mets history — that place where the significance of 1969 and 1986 and Mike Piazza’s home run on September 21, 2001, are implicit — The Rob Gardner Game has long lurked. The Rob Gardner Game may be NYMIYKYK incarnate. If you know, you know. Yet it isn’t something everybody knows. If you don’t know, you’re hardly alone. A few weeks ago, on the National League Town podcast, I referred to The Rob Gardner Game in the context of the eight Mets games that have ended without a winner or loser (when we weren’t sure what was going to become of the suspended Mets-Marlins game of September 28), and I received a social media response from someone who said he’d never heard of the game nor the pitcher…and to subconsciously authenticate the comment, this Mets fan referred to the pitcher as Ron Gardner.

Given that Rob Gardner, who died two Saturdays ago at age 78, hadn’t pitched for the Mets since 1966, or anybody in the majors since 1973, it’s understandable that his name and his feat would be enveloped in the unknown among future generations. His name doesn’t come up very often, and his feat is so unapproachable in modern starting pitching that it takes unusual circumstances to summon it above the surface. If a Met has a perfect game going, you’d probably mention Seaver and Jimmy Qualls or maybe Matt Harvey and his bloody nose. If a Met is threatening to strike out ten consecutive batters or approaching as many as nineteen in nine innings, the names Seaver and Cone are going to cross your mind, lips and, if your phone is readily available, fingertips. Even a tidy shutout might usher the above into your head.

It would be more difficult to organically start thinking about The Rob Gardner Game because nobody’s come close to doing anything like it since The Rob Gardner Game.

Feats and names like those referenced above are the sunniest side of Amazin’, whereas If You Know It, You Know It pretty much transcends or perhaps eludes what we think of as Amazin’. There’s no formula for this, but it’s been my experience as a student and consumer of Mets history that in the best moments of the Mets, when our boys surge from behind with the odds stacked against them, that’s what we call Amazin’! In the lesser moments of the Mets, when our lads somehow find a way to lose when you can’t imagine anybody else would, well, that’s more or less what Casey Stengel meant the first time he called us Amazin’.

The Mets have been Amazin’ in victory and the Mets have been Amazin’ in defeat. But to do what Rob Gardner did and for the Mets — Rob included, but not limited to Rob — to come away with nothing more than a no-decision?

That would seem to be something else altogether.

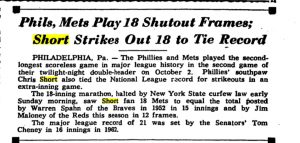

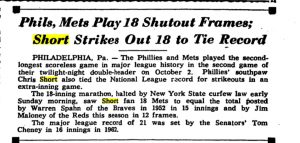

On October 2, 1965, the Mets hosted the Phillies in a Saturday twi-night doubleheader necessitated by rain Friday night. The doubleheader was necessary, as far as completing the schedule went. Why it had to be a twi-nighter isn’t clear, as the Saturday game was initially scheduled in the neighborhood of 2 PM. Perhaps Shea’s notorious outfield puddles needed the extra three-and-a-half hours to drain. But this was the era when games went quickly, even without a pitch timer. Starting Game One a little after 5:30 might have fouled up some moviegoing plans, but otherwise, what was the harm in making it a twi-nighter?

Game One proceeded swiftly enough, over in 2:31, with a result common to the 1965 Mets, a 6-0 loss at the hands of Jim Bunning, who deserves a digression, even if we are paying tribute to Rob Gardner and The Rob Gardner Game. Bunning allowed three baserunners — singles to Ron Hunt in the first and Bud Harrelson in the sixth, a walk in the second to Johnny Lewis — in going nine, or three more than he allowed in the opener of another doubleheader at Shea the season before. He won that game, 6-0, too. Jim’s effort from June 21, 1964, was a perfect game, so it’s remembered a little more than this one. Actually, almost every time Bunning faced the Mets in 1964 and 1965, it was either a harbinger or an echo of what is indisputably The Jim Bunning Game, when it wasn’t that very game.

04/15/1964 @ PHI: 9 IP; Phillies 4 Mets 1 (7 H, 3 BB, 1 HBP, 11 SO)

06/13/1964 @ PHI: 9 IP; Phillies 8 Mets 2 (5 H, 0 BB, 4 SO)

06/21/1964 @ NYM: 9 IP; Phillies 6 Mets 0 (0 H, 0 BB, 10 SO)

08/09/1964 @ PHI: 9 IP; Phillies 6 Mets 0 (5 H, 0 BB, 6 SO)

08/14/1964 @ NYM: 9 IP; Phillies 6 Mets 1 (5 H, 2 BB, 7 SO)

05/05/1965 @ NYM: 9 IP; Phillies 1 Mets 0 (4 H, 0 BB, 5 SO)

05/24/1965 @ PHI: 5 IP; Mets 6 Phillies 2 (7 H, 2 BB, 7 SO)

07/24/1965 @ NYM: 9 IP; Phillies 5 Mets 1 (2 H, 1 BB, 12 SO)

08/01/1965 @ PHI: 7 IP; Phillies 3 Mets 2 (5 H, 0 BB, 8 SO)

10/02/1965 @ NYM: 9 IP; Phillies 6 Mets 0 (2 H, 1 BB, 10 SO)

That’s ten starts in two years, a 9-1 record with eight complete game victories, four of them shutouts, four of them of registering double-digit strikeouts and one of them the epitome of perfection. Conclusion: Bunning, eventually elected to the Hall of Fame, didn’t need to be perfect when he pitched against the Mets. He just had to pitch against the Mets.

And on October 2, 1965, just as on June 21, 1964, the Mets had to return to the diamond and play a whole other ballgame.

Game Two actually went more swiftly on a minutes-per-inning basis than Game One. Each inning of Game One took a little more than sixteen-and-a-half minutes to navigate. In Game Two, the innings averaged out at shade under 15 minutes. Had you a babysitter on the clock or were worried about rising early Sunday morning for reasons sectarian or otherwise, this would indicate you were in decent shape, even with Game Two starting toward 8:30 PM.

Only problem was Game Two would encompass twice as many innings as Game One. Neither starter, Chris Short for the Phillies nor Rob Gardner for the Mets, was throwing a classic Bunning, but they each kept pace with Jim’s Game One performance.

And then some.

The Phillies blogger version of this story might refer to our contest of interest as The Chris Short Game, except Chris Short Games were numerous in a career that spanned 1959 to 1973, every season except the last one spent with Philadelphia. The lefty posted between 17 and 20 wins four times in a five-year span and made two All-Star teams. Manager Gene Mauch relied on Short and Bunning to carry the Phillies to the 1964 pennant, which proved too much of a burden for the team that was collapsing all around them. The duo started ten of the final fifteen games those Phillies played — five apiece. Short went on rest that mirrored his last name: two starts with only two days’ rest, the other three on the then more common three days’ rest. It was crunch time, and Mauch wasn’t messing around. Except crunch time devoured the pair of pooped pitchers at season’s end, and the 1964 pennant wound up flying over St. Louis.

Still, 301 starts as a Phillie, with 132 wins and 24 shutouts, enough to earn him 1992 induction onto the Phillies Wall of Fame. Lots of candidates within such a portfolio for The Chris Short Game, you’d figure. But could you do better than 15 shutout innings punctuated by 18 strikeouts, or as many as any National Leaguer had ever struck out in an extra-inning affair to that point? With no vested interest in Chris Short’s story (one that sadly ended when he was 53 years old in 1991), I’d have to think that would qualify quite nicely as The Chris Short Game.

Those totals were accumulated in the nightcap of October 2, 1965. Fifteen innings pitched. No runs allowed, with nine Met hits and three Met walks scattered. Eighteen Met batters struck out. Yikes.

But let’s toss the “yikes” into the visitors’ dugout so we can see how they look on the other foot, because Chris Short’s Phillies did nothing to support him. They, too, faced a starting pitcher for fifteen innings — a rookie, no less, though a rookie who had once thrown sixteen innings in a minor-league start — and they, too, didn’t score. Five hits and two walks, but no runs. They didn’t strike out quite so often (only seven times), but the bottom line was the same.

Where it mattered, on Shea Stadium’s massive scoreboard, the Phillies couldn’t touch Rob Gardner. Of course they couldn’t, because the nightcap of the Mets-Phillies doubleheader of October 2, 1965, was The Rob Gardner Game.

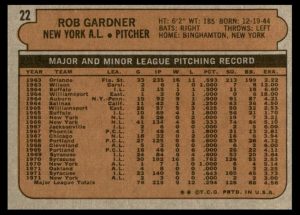

Rob had more than one game as a Met, actually. Let us be clear that Rob Gardner had other good games in his Met career, including two route-going wins the following May, 2-1 over the Cubs and 6-1 over the Giants. Also, Rob enjoyed a very solid season in a New York uniform in the next decade, even if it wasn’t what we’d consider the most desirable New York uniform. The southpaw came up to the majors on September 1, 1965, the day before the Mets retired Casey Stengel’s number, and lasted, as a Milwaukee Brewer until July 13, 1973, by which time pitchers in that league were no longer encouraged to hit for themselves (which, in Rob’s case, might have been for the best, as he represented four of Short’s eighteen strikeouts). He didn’t stick on any one roster for all that long, but he stuck around in general. The Oakland A’s, while they were in the process of winning three consecutive division titles, thought enough of Rob to acquire him three separate times. Gardner’s ledger shows 109 games pitched altogether, starting and relieving.

But only one could possibly be The Rob Gardner Game. If the TRGG’s calling card was merely 15 innings — endurance matched by only one other Met pitcher, Al Jackson in 1962 — that would likely be enough. If TRGG’s credentials were simply embellished by the fact that the 15 innings translated to 15 zeroes, so many that you know Shea’s “Stadiarama” technology, however breakthrough it was considered when it debuted, couldn’t display them all that once, that would be more than enough. No other Met has thrown fifteen shutout innings in one game (Little Al in ’62 was nicked for a run in the fifth and gave up two to take the loss in the fifteenth). What makes The Rob Gardner Game The Rob Gardner Game is its resolution.

There was none. Certainly not for the starting pitchers there wasn’t. Short threw fifteen scoreless innings. Gardner threw fifteen scoreless innings. Short got a no-decision. Gardner got a no-decision.

Everybody got a no-decision.

Picture Oprah Winfrey telling each of however many among the paid attendance of 10,371 who remained as the teens kept piling up to look under their seats. “You get a no-decision! You get a no-decision!” Same for those sitting in the dugouts or the bullpen, same for those standing at their positions. For as swiftly as those innings were going on a minutes-per-frame basis, there were a lot of innings. Extra innings, obviously, not to mention the hours that entailed: four full, plus almost half of another. By October 2, 1965, Mets history was already informed by how long it could take this team to play and usually lose some games, most notably the one from the end of May in 1964, also the nightcap of a doubleheader. That’s the one that went 23 innings and 7:23 on wristwatches. Except that had lots of scoring — Giants 8 Mets 6 — along with lots of anecdotes (the Mets turned a triple play; Willie Mays played shortstop; What’s My Line? referenced it live on the air, flipping many a channel in the Metropolitan area from 2 to 9) and, most importantly regarding its conclusion, it started on a Sunday afternoon, far earlier than the first pitch Gardner threw to commence the nightcap action on what could no longer be called Saturday evening. Blue Laws lingered on the books in 1965. You could play late into the night any night as far as the National League was concerned by then, what with NL curfews having been done away with after 1964, but heaven forefend you start an inning as 1:00 AM closed in and Saturday night became Sunday morning in New York. Then again, with Saturday games usually executed in the afternoon and most games proceeding with alacrity, how often was that likely to come up?

It came up on what was now October 3, 1965. Over the succeeding three innings following the respective departures of the starting pitchers, the relievers who succeeded Short and Gardner — Gary Wagner and Jack Baldschun for the Phils, Darrell Sutherland and Dennis Ribant for the Mets — kept the zeroes coming. That’s how we got through eighteen innings of total shutout ball. That’s how, with the Longines clock atop Shea’s scoreboard ticking relentlessly, 0-0 got called a tie. They didn’t suspend games of this nature then. They declared the game happened individually — with the stats of Gardner, Short and all those flailing batters going into the books — but not in the standings. No sense picking up a game with zero pennant implications the next day, the final day of the season, in the nineteenth inning.

Nor was there any sense in doing what they used to do with ties and playing it over from scratch. But they did, anyway. It, like everybody being told to go home from a gathering at Shea Stadium before 1:00 AM on a Sunday, was the rule, so it was followed to the letter. The weary second-division finishers had to do a little extra finishing on Closing Day and play a doubleheader in daylight on October 3. The Mets lost both games, both by scores of 3-1. The second game went thirteen innings. Jack Fisher pitched all thirteen, the third-longest outing by any Met pitcher ever. Al Jackson, who pitched fifteen innings in a losing cause in 1962, started the opener and lost, going eight-and-a-third (piker). Jack, like starter Larry Bearnarth in Saturday’s opener versus Bunning, was beaten by a future Hall of Famer, Fergie Jenkins, who pitched two innings of relief. It was Jenkins’s second major league win and his last as a Phllie; he’d be traded to the Cubs come April. Fisher’s final record for 1965: 8-24. Jackson’s: 8-20, his “you have to be pretty good to lose 20 games…” mark clinched in the doubleheader. It was the last time one National League staff harbored a pair of twenty-game losers and there they were, losing on the same day, the final day of the season.

Fisher’s and Jackson’s hard-luck exploits on top of Gardner’s should have made great or at least acrid copy in the New York papers, except the New York papers were on strike. The Philly press, in whatever space wasn’t given over to the Iggles by Monday, was understandably more interested in the visitors’ angle — Gene Mauch denied the Phils were, as Stan Hochman in the Philadelphia Daily News termed them, “a pack of malcontents” — though there was a day-after quote from Bunning, reflecting on the callow competition he and his staffmates dominated all weekend. “What are they doing,” Jim asked of the Mets brass’s thinking, “rushing those kids to the majors?” True enough, Saturday’s and Sunday’s lineups included quite a few representatives of the Youth of America, as Stengel liked to hype them before he and his broken hip gave way to Wes Westrum. Maybe kids named Ed Kranepool, Bud Harrelson, Ron Swoboda and Cleon Jones weren’t yet fully enough formed to take on the Bunnings and Shorts of the National League. Longines’ clock would tick on where they were concerned.

The Mets had tried to bide time with the baseball-elderly in their first season, and lost 120 games. Slowly but surely, youth was coming to define the franchise. Lindsey Nelson, in Backstage at the Mets, a book he published with Al Hirshberg in 1966, tried to dissect the futility he’d witnessed so much of for four seasons and asked, “how do you achieve victory? Where is your future? In the kids, of course, in the Kranepools and the Hunts and the Swobodas and the Napoleons.” Lindsey rattled off more potential comers, “kids like Kevin Collins and Darrel Sutherland and Tug McGraw and Johnny Lewis and Jim Bethke and Dick Selma and Larry Bearnarth and Jerry Hinsley and Ron Locke and Johnny Stephenson and Greg Goossen and a whole crop of others you haven’t heard of yet.”

Presumably, one of the latter cohort was Rob Gardner, as Lindsey, despite his admirable thoroughness, left out the lefty (and Cleon Jones).

Geographically in between New York and Philly, writing for the Record in North Jersey, Gabe Buonaro noted, “The Mets had to play 49 innings in less than 30 hours before realizing they weren’t much better than when they started in 1962.” The perceived progress of climbing from 40 wins the first year to 51 in ’63, then 53 in ’64, was wiped away when the Mets’ 0-3-1 final weekend left them at 50-112 for ’65. The most positive number to come out of the Mets’ fourth season? Home attendance was, as the AP put it, “a highly successful 1,768,387,” better than the year before, when Shea Stadium opened, trailing only the league champion Dodgers and the newly domed Astros in the NL. Shea was absolutely still an attraction, even if the novelty would probably need some Ws to enhance it down the line. As Lindsey advised at the end of his future-leaning chapter, “Keep trying.”

When the Sporting News got a chance to mention what had happened on October 2 & 3, in its October 16 issue, the so-called Bible of Baseball gave the eighteen shutout innings the Mets and Phils played three Short paragraphs, which is to say Chris Short was lauded for tying the NL extra-inning strikeout record, and Rob Gardner went altogether unmentioned.

You forgot a pitcher, Bible. Given the lack of dedicated on-site coverage of the Mets’ side of the Saturday night tie and the sparse crowd through the turnstile (no doubt lessened as Sunday approached and pay-phone calls to babysitters resulted in early exits), not to mention that a final weekend with no postseason implications tends to not draw focus to begin with, the rarity of an eighteen-inning 0-0 tie in which both starting pitchers went fifteen shutout innings seemed destined to fade into immediate obscurity, a field of zeroes falling in a forest whose trees glistened with the dewdrops of puritanical residue. Baseball’s attention turned to L.A. and Minnesota, where the World Series was about to start up. “Curfew” was accepted as just one of those things that arose. Same for a tie. Today, one imagines, the likes of Sarah Langs, Jayson Stark and Mark Simon would be all over this kind of game, and our contemporary baseball curiosity culture would lap up every extraordinary nugget with an oversized spoon. Then, you either saw the game or leafed past something about it in the Sporting News later in the month.

The Mets in their brief history had played three other ties before October 2, 1965, including one at the end of that May (due to darkness at Wrigley). They happened, as did replays of ties; the system wasn’t any daffier than suspending a game in a rainy first inning on April 11 and picking it up as if five-and-a-half-months hadn’t gone by on August 31, as occurred by MLB fiat with the Mets and Marlins in 2021. It couldn’t have not seemed odd or a little illogical to make these immediately winterbound teams make up the eighteen resolution-deprived innings from Saturday night with an additional nine on top of the nine scheduled for Sunday (which turned out to be thirteen), but 162 is 162, and the Mets and Phillies were on the premises, so a Sunday doubleheader it became in the name of the sanctity of the schedule. But then it was over, and everybody moved on.

All of which is to say what should have been legendary in the most textured sense of the word — people should have been telling stories of the night the recent minor league callup for the perennial last-place ballclub went toe-to-toe with a star pitcher for fifteen innings only to have a rarely invoked calendar-dependent technicality get the best of both of them and their teams — all but disappeared from the Metsian discourse. Bob Murphy, Ralph Kiner and Lindsey Nelson were marvelous in bringing me up to speed on all the charisma and color and hijinks of the Mets I missed before tuning into this franchise in 1969, especially that 23-inning game from 1964 and the doubleheader it was a part of, but I don’t ever remember them filling time between pitches with recollections of that night at the end of the 1965 season when Rob Gardner did something no other Met had done. Lindsey had a good excuse — he called Notre Dame games on Saturdays in the fall and was in South Bend, which may also explain why he omitted Rob from his Youth of America roll call in 1966. Maybe the fact that their newspaper compadres weren’t on the job in early October ’65 to bring it up to Bob and Ralph in some random pregame press room chit-chat (“hey, Murph, remember that night when that kid went fifteen and they called it a tie?”) cut the legs off the tale. It seemed to miss all the post-’69 team histories I read growing up, probably because those tended to be written by the beat reporters who were remembering what they saw, and having been on strike that weekend, they didn’t see it.

Thus, the basic qualities of Amazin’ eluded The Rob Gardner Game. It wasn’t an unlikely win that would draw a hearty hand clap when its particulars were rolled out yet again. It wasn’t a mind-boggling loss over which you could only shake your head and chuckle ruefully/knowingly about how those Mets could be. It was a tie that didn’t get sufficiently chronicled and wouldn’t be batted around in the years to come. The Mets’ record in 1965 should be expressed properly as 50-112-2. Yet when was the last time you heard a baseball record carried out to a third column?

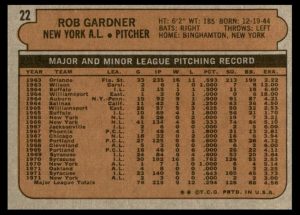

Me, I’m almost certain I had no idea this game existed for the longest time, even though I knew who Rob Gardner was when I was a kid. When I was a kid, Rob Gardner was a Yankee. I knew that because he was having a pretty good go of things in the Bronx. Not that I was in favor of that, but it was what it was. Gardner’s best year in the majors was 1972: fourteen starts, eight wins, a hand in helping the Yankees to legitimate contention (something else I wasn’t in favor of). That was the year I got my first Rob Gardner baseball card. I’m pretty sure I got several that year. One day I turned one of them over and examined Rob’s stats. For 1965 and 1966, he was listed as a member of New York, but the league then was “N.L.”. Son of a gun, I thought, this guy was a Met. I experienced that sensation once in a while in my formative years. I’d get a Bob Johnson (either Bob Johnson), a Larry Stahl, a Don Shaw and notice New York N.L. in their past. Who knew? Not me. There must have been more Mets way back when than our announcers talked about these days was my conclusion.

Do I see a New York N.L. hidden in plain sight? Had Topps not opted to fill out Gardner’s stats with his many minor league stops, I might have learned about his fifteen-inning virtuoso performance from seven years before, but there was no biographical info beyond height, weight and birthdate, how he threw, how he batted, and his home being Binghamton. A kid handling card No. 22 in the first series of 1972 was left to deduce that if they were showing you minor league records from 1963 forward — which included time at Syracuse in 1971, because Gardner still hadn’t truly established himself in the majors — there must not be much more to tell.

Had I had Gardner’s 1967 card, like I had Chris Short’s, I might have retained the salient details of his career to date:

Rob is one of the bright young pitchers in the New York Mets’ organization. The smooth throwing southpaw holds the club record along with Al Jackson for most innings pitched in one game. Rob accomplished this feat by hurling fifteen scoreless innings against the Phillies on the next to the last day of the season in 1965. Watch him go in 1967.

Though Topps left out the part about the tie, they couldn’t have been more on point. In Dick Young’s not yet jaundiced view, Rob was right up there among the “young pitchers who made Alvin Jackson expendable” when the Mets traded for Ken Boyer in the offseason following ’65, namechecking him in the same up-and-comers list that included Tug McGraw and Dick Selma. By May of ’66, Barney Kremenko was celebrating Rob in the Sporting News for his self-taught curveball, noting the fifteen-inning performance from the previous October “gave him extra status when he reported in camp for spring training. Before his performance against the Phillies, Rob was just another young pitcher in the Mets’ organization.” The upshot of Gardner’s foothold in the bigs was at least he, his wife and their baby could lease an apartment in New York this year without worrying about getting sent back to the minors.

Ah, but Topps saw what was coming, for even though Gardner’s breaking stuff helped him to those complete game wins in May, the rest of the season didn’t go all that well, and in 1967, Mets fans did watch him go. He was traded to the Cubs for another lefty, Bob Hendley. As they crossed agate-type paths, perhaps the portsiders compared notes on what it was like to pick the wrong night to throw the respective game of his life. You think Gardner was overshadowed by Short’s eighteen strikeouts? On September 9, 1965, Hendley twirled a masterful one-hitter at Dodger Stadium versus the eventual world champions. The only run he gave up was unearned: walk, sac bunt, steal of third, throw got away. His mound opponent? Sandy Koufax. Koufax threw a perfect game. Also going to Chicago as the player to be named later in that deal was Johnny Stephenson, who struck out to end Jim Bunning’s perfect game in 1964.

Irony is swell, but it doesn’t secure leases in major league cities. There’d be a lot of bouncing between the majors and the minors for Rob Gardner between 1967 and 1975. The solid ’72 with the Yankees made him attractive anew to Charlie Finley in Oakland. Finley liked to wheel and deal, and Rob got caught up in a trio of green-and-gold transactions. Once he was traded for Felipe Alou. Another time, he was traded for Matty Alou. How he was never exchanged for Jesus Alou is almost as big a mystery as the 0-0 tie of October 2, 1965. No more astounding performance in Mets history feels as shrouded in as much fog as The Rob Gardner Game. Contemporary accounts are few, vague and terse. Footage isn’t in evidence. It may have earned the pitcher in the home uniform “extra status” when it came to a fleeting leg up on a full-time role the next season, but even the man himself didn’t remember how it all went down until he was reminded of it.

In 2020, with the pandemic demanding creativity from idling baseball writers, Hannah Keyser, then with Yahoo! Sports, reached out to Gardner, 75 at the time, to explore the game as in-depth as possible from the vantage point of nearly 55 years later. “You’ve probably never heard the story of the best pitching performance in Mets history” was the headline. It’s an engaging article, highlighted by…

a) Rookie Swoboda recalling he left the stadium to dine at nearby Lum’s with his parents once he was ejected for arguing balls and strikes in the first inning of the nightcap, and then, after a leisurely dinner, noticing the lights were still on at Shea (“I wasn’t supposed to leave,” he found out the next day).

b) Gardner’s opposite number Short going as long as he did because, per scuttlebutt Rob heard later, Chris insisted to Mauch, “I’m not coming out until that other son of a bitch comes out.”

c) The protagonist of the story not knowing until Keyser reminded him that the game was a tie that was started over from scratch the next day. He sort of remembered it resuming from where it was called for the curfew, but nope, it wasn’t. Then again, like Swoboda on Saturday, Gardner had left the ballpark. Since Westrum wasn’t going to use him on Sunday, he and his wife got an early start on their drive home to Binghamton.

“That means that game never existed,” is how Rob in 2020 processed his fifteen innings of superlative effort.

But of course it existed. Individual stats always existed in ties. And, though I understood what the headline writer at Yahoo! was going for, I resented slightly the implication that I had never heard of this pitching performance. By 2020, I was well-versed in the topline details of what had happened on October 2 into October 3, 1965. Thing is, I have to admit, I’m not sure when I first heard of it. As it wasn’t one of those legends that seeped into my consciousness through the courtesy of Bob, Ralph and Lindsey, it wasn’t “always” a part of my Mets knowledge base. I likely learned of its existence sometime after 2000, long after I put aside that 1972 Gardner card, once Baseball-Reference came into being. Before Baseball-Reference (and its essential and still extant forerunner Retrosheet), if you didn’t quite remember something, you either started combing your baseball library or planned a visit to your public library. Mostly you remembered murky details as best you could and went around unaware of everything else you never heard of.

If I stumbled into The Rob Gardner Game, I’m guessing it was in service to looking up Game Scores on Baseball-Reference. I learned what a Game Score was shortly after we began blogging here in 2005. It’s a Bill James-devised metric meant to deliver a thumbnail sketch of a starting pitcher’s effectiveness in a given outing:

50 point baseline

1 point added for each out/3 points for each complete inning

2 points added for each inning completed after the fourth

1 point added for each strikeout recorded

2 points subtracted for each hit allowed

4 points subtracted for each earned run allowed

2 points subtracted for each unearned run allowed

1 point subtracted for each walk issued

You recognize a superbly pitched game when you see it, whether you’ve actually seen it or just read the box score, but Game Score was a way to quantify it, and what baseball fan doesn’t want a digestible number to bandy about for comparing and contrasting purposes? In the mid-2000s, I may have been looking up best Mets Game Scores because of something Pedro Martinez had done in the present, or out of curiosity for something Tom Seaver or David Cone had done in the past, but when I got there, one name topped them all: Rob Gardner. Rob Gardner’s Game Score of 112 on October 2, 1965, was and remains the top Game Score in Mets history, six points better than the runner-up, Seaver in a twelve-inning no-decision en route to a fourteen-inning Mets loss in 1974, and thirteen points better than Cone, who set the nine-inning record when he struck out nineteen Phillies on Closing Day 1991 (as the cops waited to talk to him). Pedro, incidentally, posted his highest Met Game Score, 90, when he flirted with a no-hitter in June of ’05. Not so incidentally, Chris Short’s Game Score from The Rob Gardner Game was 114.

Like I said, I think this was when I first learned of Gardner’s night of brilliance. Or I kind of knew it, but the metric cemented it enough that in the years to follow, I’d casually drop it into conversation on an IYKYK basis, confident that whoever I was talking to it knew. For example, I was fully aware of it as Jason and I departed Shea on September 27, 2008, the penultimate game at the ol’ ballpark, when Johan Santana blanked the Marlins for nine innings on one knee. We didn’t know he only had one good knee as we watched him shut down Florida. We knew we couldn’t afford to lose in pursuit of a playoff spot as the season (and Shea) were ending the next day, nor could we afford to see the bullpen gate swing open with any 2008 reliever entering, as Jerry Manuel’s circle of trust’s circumference resembled a pinprick. Our breath was taken away by what Johan did, and as we made our way down the ramps, we asked each other if we had just seen the best pitching performance in Mets history. I remember speaking up for The Rob Gardner Game as a candidate, knowing Jason knew what I was talking about. I also remember we sort of hastily dismissed it because on that penultimate Saturday forty-three years earlier, when hitters on both sides might not have been locked in on any pitch as much as they were mentally loading their automobiles and heading home, nothing was really at stake for the 1965 Mets.

Certain moments’ ability to defy quantification represents another reason The Johan Santana Game with its very good if not dazzling Game Score of 87, holds a place of honor alongside The Imperfect Game and The Ten Consecutive Strikeouts Game and The David Cone Game and The Bobby Jones Game in the 2000 playoffs and The Jon Matlack Game in the 1973 playoffs and The Al Leiter Game to get us into the 1999 playoffs and The Nosebleed Game a couple of weeks after The Harvey’s Better Game and some others that don’t require much elaboration above the surface in the annals of New York Mets history where best-pitched games are concerned. And maybe why The Rob Gardner Game has simmered below the surface as a hidden gem, an overlooked classic of the genre.

But if you know from The Rob Gardner Game, you know fifteen scoreless innings — even if the Mets were in tenth place and a tie would be called — rates as good as a Met start gets even if one resists declaring it the absolute best.

And if you didn’t know, now you know.

You should also know that Rob Gardner’s post-baseball life had him returning to Binghamton and becoming a paramedic for the fire department up there and, when he was 56 years old, he joined other firefighters who came down from upstate to Ground Zero to help however they could in the unspeakable aftermath of 9/11. He told Keyser, “Every one of us got involved, in some corner helping somebody dig for something.” Revisiting that 2020 story, which climaxed with Rob revealing, “I felt a lot more relevant as a firefighter than I did as a baseball player,” I thought about how proud we were as Mets fans that our players in 2001 were visiting the site and reaching out to rescue workers trying to find anybody or anything in the rubble, and that the Mets’ presence was said to mean a great deal to those who had lost their brethren. And Piazza’s home run on 9/21, too, which forever sealed the bond between the Mets and those who were doing the heavy lifting. One of those people in the thick of it, however, even if it was for just one day, was a real, live New York Met, not there to lift spirits, but actually lift.

I’m guessing he didn’t tell anybody there who he’d been or what he’d done in 1965.

by Greg Prince on 26 October 2023 8:46 pm For the second World Series in a row, the Mets can take satisfaction in knowing they dominated their season series with the National League champions, and that if baseball ran along the lines of college football, that might be worth a few points in the coaches’ or writers’ poll.

Baseball running as baseball does, this provincially sourced footnote is worth whatever you wish it to mean. It didn’t count for much in 2022 when the Phillies’ 5-14 record versus the Mets didn’t prevent them from their appointment in the Fall Classic, and going 1-6 in their Mets games presented no obstacle to the 2023 Diamondbacks arriving where they have landed. Still, we did have our Whacking Days, and they were fun, I vaguely recall.

The Snakes, however, are the ones who whacked the Phillies decisively in the NLCS to earn the honor of representing the senior circuit beginning Friday night. We who choose to not change the channel are about to witness a Diamondbacks-Rangers tilt you could have pulled out of a hat had you had a big enough hat from which to pull and were sanctioned to continue pulling potential World Series matchups until you got this one. The Snakes, however, are the ones who whacked the Phillies decisively in the NLCS to earn the honor of representing the senior circuit beginning Friday night. We who choose to not change the channel are about to witness a Diamondbacks-Rangers tilt you could have pulled out of a hat had you had a big enough hat from which to pull and were sanctioned to continue pulling potential World Series matchups until you got this one.

To be not just fair but accurate, at any given instant in the course of the long regular season, you would have found Arizona and Texas ensconced in playoff position. There were also moments when you would have found them on the outside scratching to get back in. The six-per-league format is very forgiving of stumbles from on high. We saw each eventual pennant-winner come to Citi Field in the closing weeks of the season and produce nights that indicated they’d be as destined for spectating in late October as we’d be. Yet they each bounced back and took advantage of the shortcomings of whoever couldn’t grab a Wild Card in the NL or AL, and here they are, your respective league champs.

Sizing them up in more recent samplings whisks away reflexive paeans to randomness and righteous grievances about the best teams slipping through autumn’s cracks, because, honestly, the Diamondbacks played like the best team in the National League for several weeks when it mattered most, and same for the Rangers where they competed. Maybe it’s effective Men in Black-style erasure at work here that makes the postseason viewer forget, or at least shove to the back of the mind amid each LCS going seven, who actually finished first in various divisions. The clean-slate baseball aficionado instead winds up impressed with what’s been playing out in the championship tournament and has no complaints. To this fan, who was just somebody peering in the window at the action where they were still peddling cotton candy and bubble gum to emotionally engaged crowds, Texas looked neither lucky nor fluky in outlasting Houston, and if Philadelphia was intent on painting October red in a shade other than Sedona, they had their chances. Sizing them up in more recent samplings whisks away reflexive paeans to randomness and righteous grievances about the best teams slipping through autumn’s cracks, because, honestly, the Diamondbacks played like the best team in the National League for several weeks when it mattered most, and same for the Rangers where they competed. Maybe it’s effective Men in Black-style erasure at work here that makes the postseason viewer forget, or at least shove to the back of the mind amid each LCS going seven, who actually finished first in various divisions. The clean-slate baseball aficionado instead winds up impressed with what’s been playing out in the championship tournament and has no complaints. To this fan, who was just somebody peering in the window at the action where they were still peddling cotton candy and bubble gum to emotionally engaged crowds, Texas looked neither lucky nor fluky in outlasting Houston, and if Philadelphia was intent on painting October red in a shade other than Sedona, they had their chances.

For a spell that carried over from their welcome demolition of Atlanta, the Phillies appeared inevitable. At first, I figured I could live with it. But by late in Game Two of the NLCS, I decided I’d had enough of them. The turning point in my patience came at a specific moment. TBS was coming back from a commercial, and its booth was going on and on about how unstoppable these Phillies were and how untoppable this atmosphere at Citizens Bank Park was. I don’t believe networks actively “root” for one team over the other the way you and I might, but the more accessible the storyline, the easier the sell. And, boy, were they selling the Phillies.

Like the Eagles, but baseball!

Like Red Sox Nation, but louder!

Like Murderers Row, but in living color!

The Phillies and their burgeoning brand had won Game One and were winning Game Two by a lot, and they’d go on to win it by a lot, but it was all becoming a bit too much for me to keep sticking my head in without solidly picking a side. The TBS camera godded up Kyle Schwarber coming to bat in such a way to make him glow, at the same time casting Arizona’s catcher Gabriel Moreno into veritable darkness, almost to the role of prop. I didn’t know much about Gabriel Moreno, but I sensed he and his team deserved better.

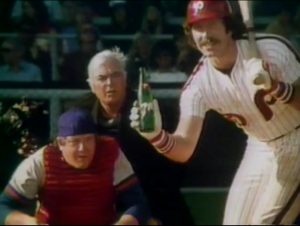

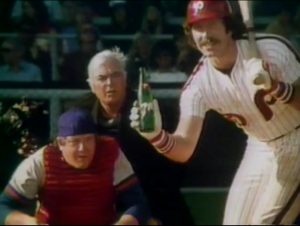

I flashed back more than forty years to my disdain of another successful Phillies unit, the Phillies who came close to winning it all in the late 1970s and would win it all in 1980. The Mike Schmidt Phillies, in other words. Those Phillies won division titles when there were no Wild Cards. Those Phillies won season series from the Mets without sweat. Schmidt was a big enough deal to co-star in a commercial for a carbonated soft drink (back when commercials featured active baseball players more than they did retired ones), positively glowing at home plate like Schwarber in 2023, also overshadowing the ineffectual catcher in his midst. Schmidt, resplendent in red pinstripes, informed the public he was Turning 7 Up by tapping home plate and having a bottle of the sponsor’s product pop up from the ground, with the forlorn visiting-team catcher crouching haplessly as he realized not only was his pitcher probably not gonna get Schmitty out, but this bastard in the box was gonna be refreshed as he rounded the bases. I flashed back more than forty years to my disdain of another successful Phillies unit, the Phillies who came close to winning it all in the late 1970s and would win it all in 1980. The Mike Schmidt Phillies, in other words. Those Phillies won division titles when there were no Wild Cards. Those Phillies won season series from the Mets without sweat. Schmidt was a big enough deal to co-star in a commercial for a carbonated soft drink (back when commercials featured active baseball players more than they did retired ones), positively glowing at home plate like Schwarber in 2023, also overshadowing the ineffectual catcher in his midst. Schmidt, resplendent in red pinstripes, informed the public he was Turning 7 Up by tapping home plate and having a bottle of the sponsor’s product pop up from the ground, with the forlorn visiting-team catcher crouching haplessly as he realized not only was his pitcher probably not gonna get Schmitty out, but this bastard in the box was gonna be refreshed as he rounded the bases.

That blue-capped catcher was, to the trained eye, wearing not just any gray jersey, but a gray Mets jersey, as if the commercial’s creators thought, “What would represent the most easily overcome object in Mike Schmidt’s world?” The blue-orange-blue trimming around the sleeves, the motif by which the Mets modeled their flourishes on the road pre-racing stripe, was the tell. Part of me was insulted; part of me was flattered to be included. That unnamed backstop was the only Met c. 1980 appearing in a national campaign for a product you’d heard of then. That blue-capped catcher was, to the trained eye, wearing not just any gray jersey, but a gray Mets jersey, as if the commercial’s creators thought, “What would represent the most easily overcome object in Mike Schmidt’s world?” The blue-orange-blue trimming around the sleeves, the motif by which the Mets modeled their flourishes on the road pre-racing stripe, was the tell. Part of me was insulted; part of me was flattered to be included. That unnamed backstop was the only Met c. 1980 appearing in a national campaign for a product you’d heard of then.

Not that there weren’t possibilities, if only Madison Avenue had been more creative.

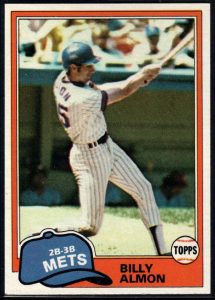

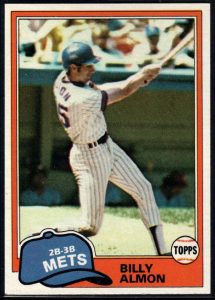

“Hey, kid, give me a handful of those Blue Diamond Almons.”

“Don’t you mean Almonds?”

“I’m universally recognized New York Mets utility infielder Bill Almon, so no, you heard me right the first time.”

“I’m sorry, Mr. Almond…I mean Almon.”

“Don’t worry about it, kid. But seriously, give me some nuts, or I’ll be blue on the diamond.”

“Sure thing! Say, are you going to share them with your equally recognizable New York Mets teammates Doug Flynn and Frank Taveras?”

“As soon as they share some of their playing time with me.”

“Hey, both those guys just went down with injuries! Looks like YOU’RE playing today, Mr. Almon!”

“Don’t you mean Almonds?”

“Blue Diamond sure does!”

But, no. The only Met to merit ad space back then was nameless and incidental, just as TBS seemed to be treating the defensively excellent Moreno now. As soon as all this sunk in, I was a dyed-in-the-temporary-wool D’Backs fan for the duration, and Gabriel — or Gabby, as we drop-of-the-hat loyalists call him — was my guy. But, no. The only Met to merit ad space back then was nameless and incidental, just as TBS seemed to be treating the defensively excellent Moreno now. As soon as all this sunk in, I was a dyed-in-the-temporary-wool D’Backs fan for the duration, and Gabriel — or Gabby, as we drop-of-the-hat loyalists call him — was my guy.

Gabby had a heckuva series, as did the rest of the Snakes, a team that came to remind me of another NLCS combatant from the era when Schmidt and the Phillies were usually riding high, the 1981 Montreal Expos. Within the same stream of consciousness that instinctively called up a 43-year-old soft drink commercial to illustrate something going on 43 years later, I found myself remembering watching the Expos take on the Dodgers for the National League pennant after Les ’Spos had taken down the Phils in the contingency division series that followed the split season of ’81. I was in my first semester of college, watching the series in my dorm’s TV lounge without company, learning that despite 7 Up having recently enlisted Schmidt, Dave Parker and Bruce Sutter to endorse its beverage, the pull of baseball might not have been as pervasive as I assumed among my own demographic. Sitting alone, I was rooting hard for the Expos because I knew the Yankees awaited the NL champs in the World Series, and I’d already experienced the Dodgers losing twice, in ’77 and ’78, to the one team I did not want to see collect another ring. That I was far from New York didn’t make that possible outcome any more palatable.

One guy who lived on my floor wandered by to watch the game with me. He admitted he wasn’t much of a baseball fan (he was a fan of starting up conversations about whatever happened to be in front of him, I would learn in the months ahead), so he confessed he didn’t really know anything about the teams playing. I offered my two-cent tutorial that the Expos would be preferable to the Dodgers from my perspective, because as someone who didn’t want to watch the Yankees celebrate again, the Expos would be hard for them to beat. “They’re that good, the Expos?” he asked. It’s not that they’re so good, I elaborated, but they run a lot and they play on Astroturf, and that’s something that stands to flummox the Yankees. The Yankees had just swept Rickey Henderson’s A’s in three straight, so I was probably overselling Expo speed’s efficacy as Yankee Kryptonite, but I believed what I was saying, however much I knew what I was talking about.

I looked it up the other night. The Expos attempted three stolen bases in their best-of-five versus the Dodges and were successful stealing twice. The Dodgers were 6-for-6 in that department, though what’s mostly remembered is Rick Monday homering off Steve Rogers in the top of the ninth inning at Olympic Stadium to decide the series for L.A. in the fifth game. Fortunately, the Dodgers went on to beat the Yankees in six in the World Series, simultaneously quenching my thirst for Sheadenfreude and dampening my enthusiasm for always being certain I’ve got things figured out in advance.

The 2023 Diamondbacks weren’t necessarily packing modern-day analogs to Gary Carter, Andre Dawson or Tim Raines, but they were emerging as a formidable bunch as they won Game Three and Game Four in dramatic fashion. They lost Game Five to this generation’s greatest postseason pitcher, Zack Wheeler, but they let neither that result nor their impending trip back east to the “madhouse” of CBP deter them. Somewhere over America, the Phillies’ inevitability fizzled like unsealed Uncola left to sit out too long. The running that reminded me of the Expos of yore came to the forefront (Snakes were 9-for-9 in stolen bases in the series); almost everybody Arizona threw at the Phillies confounded them; and, in the end, the ball was in the hands of one of the best postseason closers of this generation — the bullpen version of Wheeler, you might say — Paul Sewald.

And everybody knows there’s no hitting Paul Sewald with a big game on the line.

In the Old Friend™ derby, Sewald has outdone for impact every ex-Met left standing, and good for him. Quite clearly, Paul had some excellent karma coming to him after the black cloud said to hover above him in Flushing during his Met stay, and now he’s a World Series pitcher. So will be Max Scherzer, who, by getting in with the right bunch of Texans, won the de facto arm wrestling match with Justin Verlander to see which future Hall of Famer gets to have absolutely everything he could possibly want in this life. Scherzer, through no doing of his own pitching, gets to be part of a World Series team three months after that association seemed highly, highly unlikely. Verlander’s consolation prize, besides still getting paid an astronomical amount by a franchise for whom he did very little while briefly in their employ, is an extra week at his estate with Kate Upton, unless Kate’s on a shoot, and even then, no tears to be shed for either ex-Met.

The Rangers! The Diamondbacks! The World Series! Here’s to the enduring appeal of anything that can happen actually happening.

The Mets! Forgot about them, didn’t ya? Yet National League Town remembers some good-ish days of theirs from 2023.

by Greg Prince on 14 October 2023 1:20 pm “The moon belongs to everyone,” a wise man once informed a hallucinating man, though the subject could have been the playoffs, and that would have been wise, too. They’re here for all of us every October that isn’t October 1994, even if the best things in life include the Mets playing in them, and that’s not going on this October.

Rare treats being what they are, the Mets’ playoff involvement doesn’t go on most Octobers, so a Mets fan oughta be practiced at this type of adjustment. A Mets fan watches two non-Mets teams and picks a side, sometimes consciously, sometimes just pulled in one direction or another by the moment. You didn’t have to be a Mets fan to enjoy the National League Division Series elimination of the Braves. That belonged to everyone. For anyone reflexively pointing out that at least the Braves made the playoffs, nah. It’s too late for those who advocate on behalf of an ousted playoff team to take out their frustrations on the snickering peanut gallery far removed from the action. You’re on the big stage, you stumbled, we get to guffaw. The best things in life are free.

Enjoying Atlanta’s exit from the postseason necessarily meant being in favor of Philadelphia’s advancement therein, which is akin to a person beset by nut allergies digging into a tin marked Planters. Except it’s October, and we can be inoculated against the usual impact of our chronic allergens if we wish. We just have to forget how much we can’t stand one half of a postseason series’s participants, either because we are smitten by a fleeting storyline or we really can’t stand the other half of that postseason series’s participants. For Phillies-Braves, we had a practice round. We had Phillies-Marlins. The Phillies — who we can’t stand for getting in our face — eliminated the Marlins — who we can’t stand more for getting under our skin — in less time than it took for the Marlins to have been declared losers of a suspended game at Citi Field the week before. That’ll buy a hated foe a cup of goodwill that comes with free refills.

Once we got to the Phillies and Braves, neither were the Mets’ hated foes. They were each other’s problems, and we were so there for it. When Philly pulled out in front, I know I was there for it. The Braves lost only 58 times in the regular season. It wasn’t enough. Them losing in ratcheted-up circumstances felt too good to not want to see more. Ahead in the series and with universally acclaimed ace Zack Wheeler on the mound (Zack Wheeler…where have I heard that name before?), I was frothing for the Phillies putting their foot on the neck of the Braves. The Phillies? Really? Honestly, they had me at “…foot on the neck of the Braves”. I wasn’t going to ask too many questions regarding the color scheme of the pants leg above the foot.

Then Travis d’Arnaud hit a home run (Travis d’Arnaud…where have I heard that name before?) and the Braves eventually pulled ahead in the second game, sealing it when Bryce Harper, who has been known to use the postseason to remind everybody of his all-timer status, got caught off first base in a somewhat understandable fashion, as an 8-5-3 double play had never before been turned in a postseason, let alone to end a postseason game.

Then the Phillies clobbered the Braves in Game Three, as Bryce Harper returned to using the postseason to remind everybody of his all-timer status, though by that measure, every Phillie was an all-timer, as they were all clobbering the Braves. The chef’s kiss aspect, of course, was Harper’s pair of glares at the Braves’ shortstop, Orlando Arcia, who thought it was a hoot that Harper had been caught off first base to end Game Two and let it be known volubly and de facto publicly, then acted all hurt about his precise sentiments getting out. Atta boy, indeed.

By Game Four, as the TBS cameras made me wish I had the maroon and powder blue concession at Citizens Bank Park, I’d forgotten that I normally hate the Phillies; forgotten that they’d employed Chase Utley longer than and before the Dodgers ever did; forgotten that I can’t look at Citizens Bank Park in sunshine and not see Brett Myers striking out Wily Mo Peña to end the 2007 regular season, which clinched eternal darkness in my soul where the 2007 Mets were concerned; forgotten that I chronically cackled harder than Orlando Arcia ever did at whatever missteps or misstatements Bryce Harper made in a Washington Nationals uniform in 2015. Gotta say, in the nighttime moment, I was all in on the Phillies.

Because I was all in on the Braves being all out. How could I not be? They’re just so…Braves. Or they were, as they are no longer involved in the present tense of the postseason, having lost their NLDS in four games, or one more that it took for the similarly successful regular-season Los Angeles Dodgers to take their leave. I don’t see the Dodgers enough in the regular season to embellish my ongoing animus in their direction beyond what still exists for Chase Utley’s assault on Ruben Tejada, but the playoffs belong to everyone. Everyone can enjoy the Dodgers being bounced in October.

After two years of giving baseball’s best regular-season teams time to freshen up before re-entering the fray while their statistical lessers stay engaged by playing games that count, questions have arisen if this is the best way to conduct a postseason. Whither the 104-win Braves? The 100-win Dodgers? The 101-win Orioles, for that matter? They all withered, whisked aside by teams that won 90 games, 84 wins and 90 wins, respectively. How do we deal with this unintended disparity?

We deal with it. Or those teams can deal with it. My team won 75 games. This isn’t my problem. My team won 101 games last year and couldn’t take two out of three in their mandatory first-round series. So much for staying engaged and playing games that count. Maybe something is wrong with a setup that doesn’t more easily enable the teams with the best records over 162 games to carve a path to the World Series. Or maybe something is wrong with each of those teams on an individual basis in a given week. Or maybe a team that can be very good for a few days, like the Diamondbacks, isn’t tangibly lesser when compared to a very good team not playing its best, like the Dodgers.