The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 15 May 2023 12:39 pm On May 9, 1972, it rained in New York, which, then as now, is an unfortunate occurrence when a baseball game is scheduled in the Metropolitan Area. The Mets were to play the Dodgers at Shea Stadium that Tuesday night, meaning that baseball game would have to be made up. The good news was the Dodgers would be sticking around Queens for a couple of days. They had games scheduled Wednesday night and Thursday night. With no significant travel on their itinerary — their next stop was scheduled to be Philadelphia — it wouldn’t put anybody out if a twi-night doubleheader was scheduled. Instead of opening the gates for an 8:05 PM start, the norm in 1972, the Mets could invite fans to be in their seats by 5:35 PM for the first pitch of the first game, and then continue to maintain those seats as theirs through the final pitch of the second game. Such adjustment to circumstances by the management of the home team was traditionally one of the unexpected bonuses of a given baseball season. You didn’t expect there to be two games for the price of one on that date when you saw the schedule at season’s beginning, but sometimes you’d get a chance to partake. What a bargain!

Author Charlie Bevis, a baseball historian of all things night-game related, breaks down the utility of the twi-nighter on his incredibly informative website, explaining its application peaked between 1942 and 1972, when the NL and AL were shifting from almost exclusively day games to mostly night games. “The twi-night doubleheader originally developed to facilitate the makeup of postponed games,” Bevis writes. “The potential problem with night baseball was the postponement of a night game, since teams couldn’t just add on another night game as they easily could to an afternoon game, since spectators would not tolerate the second game starting very late at night.”

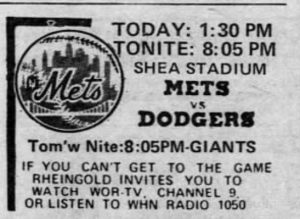

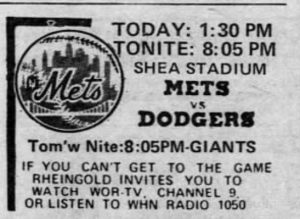

A ready-made answer hence existed for the Mets. Ah, but M. Donald Grant, running the show, had or at least signed off on a different idea. Perhaps because a players’ strike had lopped a few dates off the front end of the season, or perhaps because the Dodgers were too enticing a draw to make him tolerate losing the receipts they usually generated (a reluctantly hosted makeup doubleheader versus L.A. from the previous August might have remained fresh in the chairman’s mind), Grant approved a Shea Stadium first: a split doubleheader on Thursday, May 11. Mets and Dodgers at 1:30 PM, with all fans clearing out when that game was over. The second game would be at 8:05 PM, as scheduled. Each would require its own ticket. No freebies in Flushing this Thursday. No bargain.

Two for the price of two the first Met time. Coverage of baseball might not have been as consumer-friendly or at least as consumer-conscious as it is today. Reporters in the press box didn’t have instant access to what fans were thinking nor were they necessarily compelled to find out. Thus, when one plumbs various archives, one comes up empty in search of explanations for why, in the Mets’ eleventh season, they are suddenly deciding to charge two admissions for two games in one day after, for ten seasons, hewing to the beauty of two for the price of one, sometimes on purpose (Sunday doubleheaders were fairly standard), sometimes out of rainy necessity. In Boston, the Red Sox regularly held day-night doubleheaders when compelled by the weather, but that was understandable. Fenway Park was comparatively tiny in the emerged age of multipurpose stadia. With about 32,000 seats and decent demand, you maybe wanted to make sure every possible fan in New England could be accommodated amid a ticket squeeze. Shea held 55,000 or so seats. People weren’t likely to be left altogether out in the cold if a date went by the wayside somewhere between April and October. Rainchecks could do wonders in an enormous outdoor facility. Joe Trimble in the Daily News provided the most service journalism in this realm by detailing Thursday morning a little what would be different at Shea Thursday afternoon and evening.

“Incidentally, the matinee begins at 1:30 p.m., 35 minutes earlier than usual for a day game. The reason is obvious. The cleaning crew has to have time to sweep up the house. Season ticketholders must use coupon E-1 today. No tickets were printed for today’s game as it wasn’t on the original schedule.”

While the Mets beat writers didn’t explicitly address what the heck Grant was doing here, a reader more than a half-century later can discern more than one raised eyebrow. After covering a 14-inning affair on Wednesday night that lasted until close to midnight Thursday (“by the slender margin of 10 minutes, the Mets lost a chance at a unique tripleheader sweep”), Joe Gergen in Newsday alluded to the upcoming day-night doubleheader, attributing its scheduling to “Tuesday night’s rainout and a new management policy.” What the policy was may have been edited for space or never chronicled in the first place, but a person gets a sense that “new management policy” is code for Grant grubbing money. The Times didn’t seem to think much of what the policy wrought, with its non-bylined story devoting its fourth paragraph of ten to noting, “The two games — two for the price of two — were watched by a total of 28,732 persons, not many for a rivalry with ancestral overtones. Only 8,299 paid to watch the afternoon half of the program, a makeup for Tuesday’s rained-out game, and 20,433 turned out at night.” Indeed, during the last series in which Mets hosted weeknight games against the Los Angeles Dodgers of no longer Brooklyn, in June of ’71, paid attendance topped 35,000 twice.

Once the two-for-two occurred, there didn’t appear to be much followup on the subject of Shea’s experiment with day-night doubleheaders in the local media. To be fair, there was a lot going on in Metsopotamia that week.

• There was that 14-inning game on Wednesday, won by the Mets on Teddy Martinez beating out an infield single following Buddy Harrelson stealing second and taking third on a wild pitch, all after Tug McGraw pitched five innings of shutout relief. “It was a long night,” Harrelson observed in the home clubhouse as the calendar pushed forward. “It was almost a long tomorrow.” There was, too, the quick turnaround for that day half of the split-admission extravaganza ahead. (Gergen: “McGraw still was in his underwear at 12:30 and he was due back at 11:45 AM.”)

• There was the Mets’ win in the day portion Thursday which featured Tom Seaver’s 100th career victory, achieved despite what had become chronically aching legs; imagine how terrific Tom would be feeling totally healthy.

• And, oh, there was the little matter of a trade the Mets were working on with the team that was coming into the Shea once the Dodgers left town after the nightcap (which L.A. salvaged to not make their stay in New York a total washout). The Mets and Giants were talking through a deal that would send one of San Francisco’s high-priced veterans back east so he could finish his career in the city where he started it. The Giants weren’t having a great season and weren’t drawing well. The Mets could afford him and, though he wasn’t the player he was in his prime, the 41-year-old’s appeal was undeniable. You might have heard of him. His name was and is Willie Mays, the Say Hey Kid who recently turned 92. Although the Giants were playing in Montreal, Mays had his club’s permission to fly ahead to New York to get involved in the talks himself. Everybody had to be satisfied by the brewing transaction that was filling newspaper column inches Wednesday and Thursday. On Friday, May 12, Willie, in a suit and tie, was on the back page of the four-star edition of the News, pictured sitting in the press box taking in the Thursday afternoon action in the company of the sparse crowd; Grant presumably didn’t charge him to count among the 8,299 who went through the turnstiles. Willie appeared to be watching intently. He should have been. Those were his new teammates down on the field. The Mets had swung the deal for Mays on May 11, 1972 — exchanging pitcher Charlie Williams and a reported $100,000 in cash — the day that doesn’t primarily go down in franchise history as the day Tom Seaver notched his hundredth win nor as the day the Mets experimented with day-night doubleheaders.

Willie Mays watches history at Shea just before making his own. The experiment lasted a combined 18 innings. The Mets went back to making up rainouts the old-fashioned way, with single-admission doubleheaders, or as we old-timers call them, doubleheaders. On August 1, the Mets and Phillies played a twi-nighter to compensate for a rainout from the end of May. As if karma was trying to get a message to Grant, the first game of this twinbill lasted 18 innings and nearly four-and-a-half hours on its own, and the teams couldn’t play the nightcap until between-games festivities were completed. It was Banner Night, with 2,176 bedsheets and placards marched through the center field gate. Game Two (a 1:45 Koosman-Carlton special executed sans pitch clock) didn’t end until 12:45 AM. Thankfully for the players, August 2’s lone Mets-Phillies game was scheduled for 8:05 PM.

Shea Stadium wouldn’t host both segments of another day-night doubleheader until 2007, when pretty much every team resorted to split-admission twinbills if the weather was uncooperative. The Mets could reasonably tell their customers that with attendance riding high in the ballpark’s final two seasons of existence, they sure wouldn’t want to shut out raincheck holders who might not be able to turn in their vouchers for a comparable seat so easily. In 2009, the Mets would move into a smaller ballpark, where the same argument could be made with an approximately straight face. Fans, particularly those who didn’t grow up in the age of single-admission doubleheaders as essentially the only kind of doubleheaders, didn’t think anything was particularly unusual about this kind of double-dipping into their pockets.

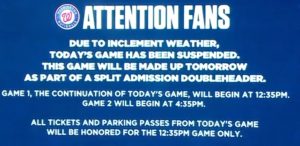

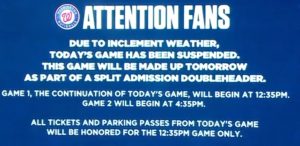

Yet nobody could instantly remember anybody doing to its ticketholders what the Washington Nationals did on the weekend of May 13-14, 2023. The Nats, who provided the opposition when the post-Grant Mets revived the split-doubleheader experiment at Shea on July 28, 2007, sanctioned the starting of their game versus the 2023 Mets this past Saturday at 4:05 PM despite ongoing rain. Maybe it would pass. It didn’t. The tarp went on the field within 40 minutes of first pitch, in the top of the third inning. It came off more than two hours later. The grounds crew came out and worked to make the field playable. It was no longer raining, but nobody was playing. People sitting on hold amid a loop of “your call is important to us…” had more of a clue as to what was going on in their endeavors than did anybody curious as to whatever became of Saturday’s contest. Ultimately, just short of four hours since play was stopped, the game was suspended. It was still the third inning, the Nationals ahead, 1-0. The Mets had runners on second and third. Daniel Vogelbach on third base and Michael Perez on second had the good sense to come in from the rain. But they and their colleagues would return to the field the next afternoon, the environs sunny and dry. It hadn’t made for an ideal scenario — not starting in the first place and preemptively rescheduling didn’t require much hindsight to anybody staring at the sky or a weather app — but these things happen.

The unusual if not wholly unprecedented part: the Nationals, who kept progress reports so quiet that not a single fan in attendance at Nationals Park, let alone anybody following along via any channel of popular communication, had any idea when another pitch might be thrown, decided Sunday would be a split doubleheader. That’s two for the price of two. Except this was a suspended game, not an outright postponement from a rainout. Baseball doesn’t let partially played games get washed away any longer. You’ll recall in 2021 the Mets and Marlins barely got a rainy game underway on April 11, halted it, and picked it up right where they left it at Citi Field on August 31 (with five Mets playing in the “April 11” game despite not joining the team until well after that date). They concluded that game eventfully in the afternoon — the Mets scored a passel of runs in the bottom of the ninth to win it, making fans forget that several players had been thumbs-downing in their general direction a couple of days before — and then cleared the ballpark for the regularly scheduled night game (which, during the Abundance of Caution era, was declared in advance a seven-inning game despite a doubleheader technically not taking place). It was basically two games for two admissions, plus the Marlins weren’t in town between April 11 and August 31, so if you squinted generously, you could almost see the semblance of sense in the solution.

Missing: any word indicating apology for inconvenience. This, in Washington, was different…or “shameful” as Gary Cohen dubbed it over SNY. This was the Mets at the ballpark the very next day when a 1:35 first pitch was on tap. Also, it was Mother’s Day Sunday, with MLB pinking up the joint. A holidaylike atmosphere in theory. Here’s what the Nationals could have done: pick up the game, right were it was left the night before, finish that game, and then have the game people paid for and call it one happy gate for those who were in the house, with rainchecks for whoever got soaked the night before.

Nah, the Nationals didn’t do that. They made it first furtive, not as much as tweeting an update once the tarp went on the field Saturday until an hour after the suspension went into effect, then, without so much as a “we apologize for the inconvenience/thank you for your support,” they made it difficult. Show up 12:35 Sunday for the suspended game, if you had a ticket Saturday. Watch that one wind down, box score and agate type curiosities included at no extra charge. It became a 3-2 Mets loss despite recalled catcher Perez rapping out four hits from the nine-hole in his first game back from Triple-A, only the second time the Mets have ever lost a game with that kind of bottom-of-the-order production, and surely the first time they’d been held to a mere two runs with their last batter proving himself entirely unretirable. It also contained the rarity of a starting pitcher, Joey Lucchesi, being optioned to the minors while the game he started more or less had stepped outside for a smoke. “Lucchesi, you’re going to the showers. Then you’re going to the airport. Then you’re going to Syracuse. Yeah, we know you gave up only one run in suboptimal conditions, but them’s the breaks, Churvy.”

Then, with the curly Ws unjustly rewarded with a competitive W despite their bad-karma creativity in consumer relations, they took the “split” in split admission seriously, more or less imploring the crowd already in the ballpark to “split!” so they could commence ushering in the originally conceived Sunday afternoon gathering at 4:35 PM for what was now a late Mother’s Day outing. The Mets won the Lerner-rigged nightcap, 8-2, with Max Scherzer returning to form (5 IP, 1 ER) and the Mets cramming all their offense into a single inning (the fifth). I’m sorry the Mets didn’t win both games, not just because I prefer the Mets win every game, but because Nationals management doesn’t deserve to benefit in any fashion from the way they presented baseball to their fans or, for that matter, visiting fans.

Somewhere down there — and I don’t mean the District of Columbia — M. Donald Grant was monitoring the Nationals’ decisionmaking process Saturday and Sunday and asking himself, “Why didn’t I think of that?”

by Jason Fry on 13 May 2023 10:38 am The important thing: The Mets actually won.

The less important thing: The Mets barely won a thoroughly strange, confounding game against the Nationals, one that left you without much confidence that any kind of worm has turned in any direction one would want a worm to turn. (If you’ve ever wondered, that strange turn [ahem] of phrase turns out [ahem again] to be a modern version of a medieval expression popularized by Shakespeare.)

The first half of Friday night’s game looked a lot like the kind of dismal games the Mets have played too many of recently: Tylor Megill gave up a run in the first and was maddening to watch, throwing not enough strikes, unable to put hitters away and trudging around on the mound with the body language usually seen with guys standing in highway medians in August wearing sandwich boards touting party-supply stories. (See also: Megill’s little friend David Peterson.)

But Megill never broke, giving up just two runs and hanging around through five; meanwhile, the Mets were grinding out at-bats against MacKenzie Gore in a fashion that reminded you of their 2022 offensive approach. That was a welcome change; what was distressingly familiar was their inability to turn those ABs into anything. Starling Marte flied out with the bases loaded to end the first; Francisco Lindor fouled out with two on to end the second; and Mark Canha flied out with two on to end the third. Gore departed after four with an ungodly pitch count but also with a 2-0 lead, and that certainly felt like it would be enough to beat the Mets.

Hell, these days an enemy runner on first with two outs in the first feels like enough to beat the Mets. Even beyond that, though, it was a sloggy, frustrating game, the kind that felt more like waiting in line at a DMV than like anything a person would voluntarily choose to do with precious hours of their life.

And then, somehow, the thoroughly unexpected happened.

In the sixth the Mets greeted Andres Machado with a Marte single and a poke-job double by Canha to put runners on second and third with nobody out, which in better days would call for the licking of chops but these days was a warning to assume the fetal position. All looked like it would come to naught as Brett Baty slapped a little grounder to third that erased Marte (with Canha failing to take third) and Francisco Alvarez grounded to first. Exit Machado and enter Carl Edwards Jr., who always makes me think of Idiocracy‘s gag involving Carl’s Jr., to secure a third out from Brandon Nimmo. Edwards walked Nimmo and looked hell-bent on walking Lindor, who went into protect mode while I peered at the proceedings from between my fingers.

Lindor didn’t walk and also didn’t make an out — he rifled the ball over the second baseman’s head and into right-center. Here came Canha, then Baty with the tying run and then — whaaa? — Nimmo steaming along right behind him, courtesy of Joey Cora‘s habitually aggressive right arm. It wasn’t even close: The Mets led 3-2 with Lindor taking second on the back end of the play, proud owner of a three-run single.

A three-run single? I wasn’t immediately sure I’d seen one of those, though that’s probably wrong: Edgardo Alfonzo recorded one against the Giants in 1997, which I would almost certainly have seen, though the first one would have eluded me as it was delivered by Tug McGraw back in 1970. (Greg noted Pete Rose recording one off the Mets — and sure enough, it beat Dwight Gooden back in ’86.)

Now, a one-run lead in the sixth isn’t exactly a ticket to the promised land: The question remained of how, exactly, the Mets were going to secure 12 outs before something terrible happened. Jeff Brigham got the first three, Adam Ottavino notched the next three, and then Buck Showalter sent David Robertson out in search of the last six.

Many things have gone wrong this year, but absolutely none of them have been Robertson’s fault — he’s been a godsend, doing his business with the no-fuss efficiency that’s sustained a long, successful career. Robertson cruised through the eighth, but walked the leadoff hitter in the ninth. He secured the next two outs, but the fuel light was blinking red and the car was gasping and starting to seize. A wild pitch, a five-pitch walk to newcomer Jacob Alu, and here came Showalter with the tow truck: Drew Smith, proud owner of zero career saves, was going to get us home safe or be left standing on the mound in shock as Nats frolicked and bumped cherry blossoms. There’d be brave talk about better approaches and fighting back and sticking with the plan and guys doing everything asked of them, but there’d also be grim sets to mouths and faraway eyes and the unavoidable statistical fact that the Mets had now lost 32,948 of their last 32,950, or whatever the exact figure is, though that feels more or less correct.

Except Smith got an 0-2 count on Lane Thomas courtesy of two fouls, threw one up and away that didn’t tempt him but also didn’t escape Alvarez, and then came back to the top of the strike zone for one Thomas could neither resist nor hit. All’s well that ends well, but I felt like spending the next hour throwing up was what was called for.

At least this time it would be throwing up out of relief.

by Greg Prince on 11 May 2023 5:00 pm When the Mets’ 5-0 loss at Cincinnati completed its appointed rounds on SNY Thursday afternoon, the postgame show came on, with Todd Zeile seated as the designated authority on all things disappointing. He was a good choice for the job, seeing as how Zeile was right in the middle of disappointment aplenty as the 2001 Mets steadily ran themselves into the ground. Thirty-eight games into the 2001 season, the Mets were 15-23, which, for reference purposes, is three games worse than where the 2023 Mets sit at the same juncture of what appears to be their voyage to nowhere.

Twenty-two years ago, Zeile wasn’t off to a good start. Twenty-two years ago, no Met was off to a good start. The Mets had been to the World Series the year before. When the season began, you could imagine them making another such run. As the season neared the one-quarter mark, your imagination had been overtaken by the prevailing reality. May 2001 ended with the Mets ten games under .500, thirteen games out of first place and not close to the one Wild Card spot that existed then.

Long season short, the Mets made a run before 2001 ended. Their horrid first quarter, which extended to a horrid first half, then a horrid first three quarters, didn’t preclude them from turning everything around. It wasn’t enough to vault them all the way from nowhere to the playoffs, but it was invigorating, at the very least. Come the final weeks of their unlikely chase of a division title, you weren’t thinking about how bad they looked in May. May, along with everything from early April to late August, still counted toward explaining why they hadn’t climbed higher in the standings, but there were games left and games won, and as long as the Mets looked alive, they represented a suitable object of support for a Mets fan who himself was turning around attitudinally. I was disgusted by the Mets in May of 2001. It didn’t stop me from sincerely applauding every good thing they did come that September.

What kind of year is this being? Not one that stays crunchy in milk, despite what this attractive cereal box is meant to imply. All of which is to say should the 2023 Mets, 18-20 at the moment following five consecutive series losses — four to teams allegedly unfit to shine their fluorescent shoes — find whatever made them a postseason qualifier in 2022 or simply shed whatever has made them sink in quicksand through the opening weeks of the year after, I will mostly forget how frigging lifeless and incapable they have appeared almost every inning of almost every week thus far. I won’t be a hypocrite when I chant “Let’s Go Mets” as if it’s 1969 or 1999. I will be a fan.

I’m a fan right now. I’m a fan who is having a hard time feeling supportive of a group of players I’d generally describe as guys I like. I don’t like the way they are playing. Fans love teams but can disapprove everything about those teams’ actions and results. There is not a lot to love, let alone like, at present.

Lousy Mets teams in May aren’t necessarily destined to be lousy Mets teams in September. I gave you one example. Others are scattered through franchise history. None among the front office, the coaching staff and the players gives up on improving. Improvement is always possible. I won’t say likely in this case because, despite the ample opportunities SNY provides me to wager, I wouldn’t have bet on an 18-20 start in 2023. Or a 15-23 start in 2001.

We commit unconscionable portions of our lives to staring at rosters and wondering how they’re not producing as we believed they would. “You’re never as good as you look when you’re winning and you’re never as bad as you look when you’re losing” is a phrase that gets thrown around quite a bit when a team projected to win does otherwise. When Tim McCarver repeated it often during rough Met patches, it seemed sensible, even compassionate. Ooh-oo child, Timmy seemed to be trying to tell us, things are gonna get easier/brighter.

These days, “You’re never as…” lands like a cudgel to the part of your brain that processes sucking and tries to come to grips with an evolving reality. It’s the baseball version of a line I heard once that advised the two worst words you can tell somebody you wish to be calmer are “calm down.” “You’re never as…” is rarely invoked when a team is exceeding expectations. You’re winning? You look good? Carry on. At worst, you get a “don’t go crazy” barked at you in a Mad Dog Russo-style voice, the spoilsport wet-blanket types telling fans of the perennially downtrodden to know our place should we dare to be excited at, say, not losing five series in a row. There’s nothing better than ignoring those scoldings, nothing better than exceeding expectations, nothing better than being surprised for the positive.

Conversely, not stepping right up to meet expectations makes a so-so season so much worse than the record indicates. There are fans of teams in this league and the other one that probably think 18-20 looks pretty good right about now. We’ve helped a few of those teams pull to within that charmed circle of a little less mediocre than they were resigned to being in 2023. Our team can’t take series from Cincinnati or Colorado or Detroit. We have a chance to take a series from Washington next, but we already had one chance and didn’t take advantage. To be fair, we didn’t beat Atlanta more than one out of three, either.

It’s an indisputably not great situation. It might get better. It could get worse. It could stay approximately the same, which would stand in for worse just fine.

by Greg Prince on 11 May 2023 12:47 am The New York Mets currently have on their roster five pitchers who were born before their last world championship, which speaks to both the age of the pitchers and the last world championship. One, Max Scherzer, hasn’t been able to make his most recent scheduled start because of neck spasms. One, Tommy Hunter, missed time in the bullpen because of back spasms. The team, not quite treading water to date, has chalked up its successes spasmodically at best. At one point, the Mets won 11 of 14 this very year. You might not remember that, given that they followed up that stretch by immediately losing 12 of 15.

Good thing, then, that they had the pitching Wednesday night in Cincinnati to pull them closer to sea level. All three arms on which they relied were attached to babies born prior to October 27, 1986. The babies grew up to become major league hurlers with uncommon amounts of experience, at least as measured in places other than the 2023 New York Mets clubhouse. On these Mets, you don’t flinch when told the pitchers in action were born in 1983, 1985 and later in 1985.

You’re just glad they’ve been around long enough to know what they’re doing.

When Justin Verlander was born, on February 20, 1983, Tom Seaver hadn’t pitched for the Mets since before the Wednesday Night Massacre. Darryl Strawberry had not yet played a single major league game. Keith Hernandez was ensconced as the first baseman of the defending world champion St. Louis Cardinals. Everything we’d come to associate with 1983 and the Mets — Seaver’s triumphant Opening Day return; Strawberry’s hotly anticipated promotion; Hernandez’s sudden arrival by midseason trade — was in the future. Baby Verlander came first, forty-plus years ago.

Then Old Man Verlander waited a while to make his Met debut, not only by spending his first 18 seasons in Detroit and Houston, but then shaking off a teres major strain for a month. We didn’t know from teres when Verlander went on the IL a couple of hours before the first pitch of the new season. We could have guessed missing him would be major. So it was. When you have a righty who’s won not only two World Series and three Cy Youngs and made those totals current within the last twelve months, you want to see what he can do for you.

In his first start, he endured one inning that had us scanning the fine print to see if his megacontract came with a refund clause, then settled down to remind us what a fully developed, reasonably healthy starting pitcher looked like. Had the Mets hit for him at all in Detroit, his two runs over five frames would have looked mighty good. They seemed fairly satisfying even in a loss.

Six days later, Justin faced another opponent he seemed readily capable of steamrolling, but we’ve been just as susceptible of rolling over for alleged bottom-feeders, middle-dwellers that we’ve become. The Reds hit plenty the night before, but that was off David Peterson, a.k.a. pitching depth. Verlander’s the front line, or was going to be had not teres major ordered him to the sidelines. Wednesday night, his entire body was back in form. Another shaky first inning, but maybe that’s his m.o. at the moment. When Seaver would encounter danger, then limit damage in a first inning, you nodded that things would probably be OK. Get to the great ones early or not at all.

The Reds got to Verlander in the first inning, for one run, then not at all. Somewhere along the way at Great American Ball Park, the 40-year-old locked in and made calendar pages irrelevant. On this occasion, Justin went seven innings in a Mets uniform, which is something only Joey Lucchesi had done among starting pitchers in 2023. Of all the new sensations Justin Verlander looked forward to as a New York Met, aspiring to match Joey Lucchesi for length probably didn’t top the list.

Thank goodness he did, though. Verlander gave the Mets the best start they’d had this season, two hits over seven innings, just that one run in the first, hardly a baserunner from the second inning on. Thus inspired, the Mets offense supported him…barely. Pete Alonso, who seems to take to steamboat architecture and the siren song of the mighty Ohio, hit a solo shot to tie the game in the second. The Mets otherwise mostly left runners here and there, but in the fourth, they accidentally strung together a double from Luis Guillorme, a walk to Francisco Alvarez and a single by Brandon Nimmo — all with two out — to take the lead. The Mets would leave eleven runners on base in all. Consider the two that crossed the plate manna from heaven.

Consider Verlander’s successors, the similarly venerable Adam Ottavino (37) and David Robertson (38), sentries worthy to stand watch over the manna. Holding an edge of 2-1 after seven, in the wake of losing 12 of 15, didn’t make one think, “This would be a great game to win!” No, this would have been a terrible game to lose, because to lose it would be to tell Verlander he really shouldn’t have stopped by on his way to Cooperstown, while hinting to the rest of us that we shouldn’t expect much to get better soon.

Fortunately, good old Adam and slightly better, slightly older David were both very much on. Plus the Reds are pretty crummy. Sooner or later we were bound to meet the enemy and it wouldn’t be us. Ottavino’s eighth was clean. Robertson’s ninth was spotless. Having tethered their lines to Verlander’s effective seven, we were treated to a rare three-man two-hit victory. How rare? Dismissing rain-shortened or pandemic-truncated doubleheader versions, Baseball-Reference’s Stathead tool tells us the Mets have now won two-hitters via three pitchers thirteen times in their history. It happened only once prior to 1998, because it used to be (when Verlander, Ottavino and Robertson were kids) that if you had a starting pitcher working on a two-hitter, he kept working on a two-hitter. The only pre-modern iteration of the three-to-give-up-two combo occurred in 1968 when Jim McAndrew went eight-and-a-third before Gil Hodges turned to Bill Short and Cal Koonce to retire one batter each to top the Cubs, 1-0.

Such specific combining wouldn’t happen again for thirty years, when the starter was Masato Yoshii and the relievers, for an inning apiece, were Greg McMichael and John Franco. The Mets beat the Cardinals that night, 4-1, on a two-hitter. What the 1968 game didn’t have; and the 1998 game didn’t have; and what none of the ten three-man two-hit victories that followed between 2001 and 2022 had that Wednesday night’s in Cincinnati featured was this much experience. The Mets had never before won a three-pitcher two-hitter in which each pitcher was a member of the 37 & Up Club. The life experience was implicit. The baseball experience was off the charts. Verlander’s been in the majors since 2005, Robertson since 2008 (he made his big league debut at Shea), Ottavino since 2010. From the vantage point of 2023, that’s a lot of years and a lot of innings, starting in one case, relieving in two others. That, as we’ve already seen this year, tends to place the risk in front on the risk/reward scale. Older pitchers had to do a lot to last as long as they have and still be trusted at this stage of their career. To ask them to defy chronological gravity as a group is trusting them even more. For a night, it absolutely worked.

On this night, it really had to.

Two Mets pitchers who may have been an even bigger deal than Justin Verlander are in the spotlight on the latest episode of National League Town. One retired last week. One made a comeback the week before. One you heard about everywhere. One you had to be watching a particular cable network to know from. Come and listen to the story of two aces too good to be true.

by Jason Fry on 9 May 2023 10:52 pm The Mets have been both bad and unwatchable for the better part of two weeks, so Tuesday night counted as progress: They were watchable.

Watchable, as they fought back after being put in a deep hole by David Peterson, Stephen Nogosek, and (one could argue) the umpiring crew, which missed a ball headed for Francisco Lindor‘s glove hitting Wil Myers in the hand as he slid into second. Intentional? Probably not. Against the rules? Certainly. Enough to make Buck Showalter mad? Oh yeah. Buck was ejected for the first time as a Mets skipper and at least got his money’s worth, indicating via a one-two-three-four pantomime visible across the river in Kentucky that four umpires had been on the field and not one of them had managed to fulfill the basics of the job.

Showalter departed dissatisfied, Nogosek gave up a two-run triple and a sac fly, and somehow it was 7-1 Reds, as the Mets continued their ill-advised run of making the dregs of the major leagues look like world-beaters. Seriously, since the wheels came off in San Francisco the Mets have lost series to the Nationals, Tigers and Rockies, and they’re now off on the wrong foot against the Reds, the sole remaining entity on Earth that hasn’t received the memo that drop shadows are out.

Down by six, the Mets did at least fight back: Posterity will record that they scored five unanswered runs. Unfortunately, mathematics will record that they needed to score one more than that. Francisco Alvarez started the futile comeback with his second homer of the night, with additional runs courtesy of homers from Pete Alonso and Lindor and a run-scoring GIDP by Mark Canha. That GIDP wound up typifying too much of what’s been happening, though: It came with the bases loaded and nobody out in the seventh, short-circuiting the inning, and Canha fell on his face after stumbling across first base.

In other words, it was the last two weeks of Mets baseball distilled into about eight thoroughly shitty seconds.

Elsewhere, well, where do you want to start? Peterson, called upon after Max Scherzer was scratched with neck spasms, looked like he’d been replaced with a heretofore unknown identical twin who had no idea how to pitch. He couldn’t throw strikes and when he somehow did you wished he hadn’t. Peterson’s short career has been marked by false starts and reversals, to be sure, but he looks absolutely lost right now, a young pitcher whose stuff, location and confidence have all deserted him. It was cruel summoning him from Syracuse when that’s pretty clearly where he needs to be, but the Mets had no choice — and, in case you weren’t already depressed, he was filling in for a guy who’s destined for the Hall of Fame but hasn’t exactly looked like himself all year either, which is starting to look like a much bigger problem than Peterson’s growing pains.

As for the Myers play, a basic equation of baseball and life is that when you’re going horseshit they fuck you. The Mets have demonstrated proof of the numerator for two weeks now, so getting smacked in the face by the denominator isn’t injustice but simple cause and effect.

by Greg Prince on 8 May 2023 12:38 pm In the Mets’ first four seasons, the club twice lost home games by a score of 13-6. The first of them, on May 30, 1962, marked the coming out party for a chant you might hear enthusiastically when the Mets are coming on strong or ironically when the Mets pausing from going down meekly: “a full, furious, happy shout of ‘Let’s go, Mets! Let’s go, Mets!’” This explosion of emotion, captured by Roger Angell in his first season occasionally covering baseball for the New Yorker, burst into the Polo Grounds atmosphere after Gil Hodges led off the bottom of the fourth with a home run that cut the home team’s deficit to 10-1.

Ironically enthusiastic? Enthusiastically ironic? Maybe more than a little defiant, given that the opponent was daring to show its face again in the city of New York after abandoning our town for better weather and better parking. Whatever the mechanism of the motivation, Mets fans were into it and the Mets went on to lose to the Los Angeles Dodgers of no longer Brooklyn, 13-6.

The second of such losses occurred three seasons later, this time at Shea Stadium against the Reds, on September 14, 1965. If Angell attended this particular defeat, he did not incorporate into any of the essays that constituted his breakout book The Summer Game. Summer was effectively over in New York by mid-September of ’65. Cincinnati’s pennant hopes were still alive. The Mets’ chances of playing meaningful games in September weren’t yet as much as a gleam in the eye of even the most anticipant fan. Not that patience was altogether in abundance. Chanting wasn’t the story at Shea that night. According to the not yet villainous Dick Young in the Daily News the next day, the pertinent sentiment of evening could be found on a two-sided banner.

Side A

GIVE US A TEAM, NOT A DREAM

Side B

PROMISES, PROMISES

The Mets entered play at 46-100, ensuring a fourth consecutive season of triple-digit losing. It’s hard for the hardiest of crowds to not come prepared to express dismay when the novelty of cheering anything and everything that isn’t consistent winning begins to wear off. A 13-6 loss, even to a contender, is a kick in the teeth of good nature, even if your team is down only 8-5 heading to the ninth.

Especially if your team is down only 8-5 heading to the ninth.

Much would happen between the Mets falling to 46-101 on September 14, 1965, and the Mets waking up to a record of 17-17 on May 7, 2023. The Mets have never otherwise been 46-101 (praise be) nor 17-17 (quite curious, considering they’ve been 18-16 eleven times and 16-18 six times). They also had lost only once at home in that span by that score of 13-6.

I know. I was there.

The date was August 12, 1982. I was two weeks from returning to college for my sophomore year, so I was intent on cramming as much Mets into my system as I could before departing. Tuesday night the Twelfth was going to be the first of three games for me over the course of five days, attendance frequency not at all unusual in the seasons to come, absolutely unprecedented in my life when I was nineteen.

Also unprecedented: standing on the ticket line outside Shea and being approached by somebody looking to get rid of a pair. He was a reverse scalper. Had two tickets — plus Diamond Club passes! — and simply needed to dump them. He’d give them to my friend and me for five bucks each, or two dollars less than the face value of a Field Level box seat in 1982. Although it seemed a little good to be real, we accepted the hard bargain. The tickets were real. First base side, very good view of the Mets and Cubs.

We didn’t avail ourselves of the Diamond Club passes (the fine print indicated we would have had to have dressed for a session of the General Assembly at the United Nations to have passed muster at the door), but the game was enough. The Mets were trailing, 3-1, until a sixth-inning rally punctuated by a John Stearns double that pulled the Mets to within a run. George Bamberger proceeded to send up Rusty Staub to pinch-hit for Ron Gardenhire after Dallas Green ordered Dickie Noles to intentionally walk Hubie Brooks to load the bases and one out. National League strategy; there was nothing like it. Green was angling for a double play ball. Rusty had a different, better idea, slamming a double to right and clearing those bags. The Mets led, 5-3. Jubilation reigned. I can’t swear “Let’s Go Mets!” arose from all the box seats, but I’m pretty sure it did from mine.

Swearing, however, would follow in short order, as the top of the seventh brought on a Cub rally that dwarfed the one Rusty capped. Chicago scored eight runs off four Met pitchers. Staub’s clutch double grew smaller and smaller in the rearview mirror. What was developing into the greatest Shea Stadium experience I’d ever had to that point dissolved into familiar angst. Just one run after another scoring off one pitcher after another. Orosco replaced Scott. Leach replaced Orosco. Falcone replaced Leach. Misery replaced ebullience. Two drunk business types a few rows down thought it was hilarious in that way people automatically laughed at the Mets. One biker type sitting closer told the business types to cut it out, but in language and with menace that I believe convinced the business types to call it a night before the seventh-inning stretch.

The Mets went on to lose, 13-6. I returned as planned Thursday night and Saturday afternoon. The Mets lost those, too. But never again at home by that same score.

Until Sunday, May 7, 2023, a day that at its start had only one obvious element in common with August 12, 1982. I was there. I’ve now been there for exactly half of all Mets home losses of 13-6 in their 62-year history.

Unlucky score. Lucky me.

No, really. I’m sitting here 41 years since 1982 and recalling at no additional harm to my psyche what it was like watching the Mets dramatically grab a lead and then be assaulted a half-inning later for all their lunch money. Yet I’ll never forget the victory of the seven-dollar box seats costing only five bucks, nor the righteous anger of the biker type, nor Rusty doing what Rusty did in a pinch.

The 13-6 loss I could have done without, but you can’t have everything. Or sometimes get saddled with a little too much.

You need a gargantuan scoreboard to fit a combined 19 runs. From the game of 41 years later, I could do without the 13-6 loss the 2023 Rockies pasted on the 2023 Mets. I could do without Joey Lucchesi no longer being a pleasant surprise. I could do without the march of mediocrity the Mets’ bulging middle relief corps represents almost daily of late. Even when Buck Showalter’s veritable Lotto drawing pulls up an occasional solid inning among your Hunters, your Brighams, your Leones and your Yacabonii, we’re playing those numbers far too often. Lucchesi, who was removed from a so-so outing in Detroit on Wednesday to make sure he’d be available to provide a so-so outing in New York on Sunday, lasted four innings (felt like three).

Admission to Sunday’s 13-6 loss cost me five dollars less than admission to the one from 1982. I was a guest at a Party Deck soiree, courtesy ultimately of a friend of a friend whose company was having an outing far better than Lucchesi’s. Also courtesy of my friend’s wife who opted not to take in beautiful weather and iffy baseball, thus the empty bar-style stool just waiting for me to top it. No stuffy business types in evidence. These are the seats in right and right-center where children — and adults briefly taking on the behavioral patterns of children — wave their arms to get the attention of outfielders who might be convinced to throw a baseball their way between innings. Every time Brandon Nimmo was entrusted with that opportunity, he sought out a genuine child and made an accurate toss. For that, Brandon Nimmo is my player of Sunday’s game.

Don’t know if you can make it out from this angle, but if you focus, you can see a bonehead play developing. No other Met garnered much consideration, despite the three-run bottom of the first that immediately erased a 1-0 Rockies lead off Lucchesi. The Mets were reaching base so routinely (and I was sitting so far from the infield) that I began to lose track of who was where. For example, when the Mets were up, 3-1, and Luis Guillorme had singled to right with two out, I was sure he had driven in Brett Baty from second. You know who wasn’t? Rockies right fielder Kris Bryant, who threw purposefully to second, as purposefully as Nimmo did to the kids in the stands. A “4” did not go up on any of the scoreboards, including the enormous one over my left shoulder. A groan of discontent went up from all seating sections.

“What happened?” I asked my friend. “Did Canha get tagged out at second?”

“No,” he told me. “Vogelbach.”

Like I said, there had been so many baserunners that I briefly lost track of who was where. Canha had made an out before Vogelbach reached first. Vogelbach made an out after reaching second, rounding the bag — with Bryant more alert to it than he was — before Baty could cross the plate with that fourth run. Vogelbach was tagged out first.

Score at the end of one: Mets 3 Rockies 1.

Score at the end of nine: Rockies 13 Mets 6.

So forgive me if I gloss over the details of the trajectory of the game from the second inning forward and share with you instead a few other observations from my first trip to Citi Field this season.

• The main video board, which swallowed dainty little Citi Vision, is indeed gargantuan, but once you get used to it, it’s seems the right size for baseball, what with baseball being the biggest thing in our lives.

Nothing’s sacred. • While I needed a few innings to just adjust my senses to watching the infield from all the way out in the outfield, I pretty quickly noticed that one of the ribbon advertising boards that wraps the seating bowl flashed a logo for New York-Presbyterin. That’s their typo, not mine. It was spelled “Presbyterian” in every other iteration across the ballpark, but “Presbyterin” on the one above and behind home plate. Make a sleeve patch out of that, why don’t you?

• Basic ballpark food is included with a Party Deck affair, but unlike those obnoxious car ads that deride basic, I’m here to tell you, per Humphrey Bogart, that a hot dog on the Party Deck beats roast beef at the Ritz, and I don’t need to know from the Ritz to assert this truism. I know from Citi Field. That was one of the venue’s better hot dogs, and it was accompanied by an even better box of chicken tenders.

• I learned at least one genuine coupon good for one Carvel Ice Cream Sundae in 1984 still exists in mint condition because it was not “redeemed at the appropriate station” at Shea by 3 PM on its day of issuance. Another friend of my friend who invited me produced a photo on his phone of said Strawberry Sunday voucher, issued to celebrate Darryl’s Rookie of the Year campaign the year before. He’s willing to donate it to the Mets Hall of Fame. I say he should take it to a Mr. Softee stand at Citi — before 3 PM, of course — and see if it will be cross-honored à la the MTA when something’s up with the subway and/or LIRR.

Is it ever too late to celebrate Strawberry Sunday? • Arithmetical skills notwithstanding, I also learned that it’s been 40 years since Darryl Strawberry was a rookie.

• I also learned there’s a limit to my Mets fan patience when eleven losses have piled up in fourteen games. Perhaps extending himself past second base for no helpful reason whatsoever moved me to articulate it, but I told my friend, “I’ve never said this out loud, but I [bleeping] can’t stand Daniel Vogelbach.” I don’t think I said “hate”. I hope I didn’t say hate. There’s nothing hateful about Daniel Vogelbach except he’s such a [bleeping] DH, and I still [bleeping] hate the DH, and I can’t believe he so thoroughly personifies the position I [bleeping] hate so thoroughly, right down to rounding second on an obvious RBI and then not getting back to the bag in time to let the runner score.

• When Vogelbach later hit one of those Estée Lauder home runs that altered the blowout loss no more than cosmetically, I theatrically applauded and cheered because I felt kind of bad about admitting the unkind thoughts I’d been harboring for weeks. “Let’s go, VOGEY! Let’s go, VOGEY!” Also, it was a Met home run and I’m not made of stone.

• My friend who invited me, who wouldn’t quite join me in my animus for Vogey, suggested quite sincerely that slumping Pete Alonso be sent to Triple-A for seventeen days to a) preserve another year of service time; and b) get Mark Vientos up here to play first, which would c) set up Alonso to DH, which I suppose would take care of my Vogelbach problem. When you’re en route to losing, 13-6, and falling under .500, there are no sacred cows. Or Polar Bears. Or the spellings of leading religions.

• Fantastic weather. Brought a jacket. Didn’t need it. The weather shares Player of the Game honors with Nimmo.

First game of the year in The Log I keep of every home game I’ve ever attended. Hopefully not the last. First 13-6 loss in The Log in 41 years. Hopefully the last ever.

by Jason Fry on 7 May 2023 10:02 am The Mets, all $430-odd million of them, are a mess.

The hitting is anemic. The starting pitching is mediocre. The record is the literal definition of mediocracy. The vibe, not an official stat but readily detectable, is a lot worse than that, with fans increasingly fuming before taking their seats, looking for someone to blame and finding no shortage of targets.

It ain’t good, folks.

It ain’t good, and after you’ve shelled out approaching half a billion, fixes probably aren’t coming from outside. Brett Baty and Francisco Alvarez are already here. Justin Verlander is back. Expecting poor Mark Vientos to be a savior seems cruel; ditto for Ronny Mauricio. Improvement will have to come from within.

And you know what? It probably will — the gremlins of sequencing will afflict some other team, guys will play more to the back of their baseball cards than they have in a month and change, and buzzards’ luck will turn to whatever the opposite of buzzards’ luck is. (I’m imagining those cheerful little bluebirds that help out Snow White.)

Or maybe none of that will happen, and 2023 will go down in the annals as one of those years when Too Much Went Wrong, a bump on the road to future glory or a flashing warning sign to the downturn that in retrospect we’ll of course all have seen coming. Baseball in the moment is a strange beast, doing what it does attended by a swarm of observers’ stories zooming this way and that; we impose the rules of narrative on it when looking back, which baseball shrugs off because it’s moved on to a new present formlessness.

That’s a wordy-ass way of saying nobody knows. Right now the Mets are not good and not fun, something that unfortunately everybody knows.

* * *

Bill Pulsipher threw out the first pitch in Saturday’s game — the same Bill Pulsipher who a million years ago was part of Generation K, arriving alongside Jason Isringhausen and Paul Wilson to form a triumvirate of arms that were going to be the rock upon which rose a new Fortress Mets.

That never happened — the trio combined for less than 100 Met starts, and were never on the roster at the same time. At the time we argued equivalents, discussing who was Seaver and Koosman and Matlack; as it turned out all three guys were Gary Gentry, Exhibit A for the caution that ought to attend each and every young flamethrower.

A couple of baseball generations later, the memories of Generation K are almost entirely sad or bad. There’s Pulse and Izzy hurling balls around the field with reckless abandon, ignoring John Franco‘s prescient warning that they’d hurt their arms. There was the day the Mets caught a rehabbing Isringhausen playing co-ed softball for a team sponsored by a strip club. There was Wilson getting left in too long by Dallas Green against the Cubs and surrendering a Sammy Sosa homer that turned his imminent first triumph to ashes. And most of all there were injuries and reversals, self-inflicted and team-negligent and simply random. Pulse went from prospect to suspect, hanging on for a variety of teams as a spare part. Injuries reduced Wilson to ordinary with cruel speed. Only Isringhausen forged a notable career, and that was as a reliever. (Look back here, if you dare.)

Pulse was at Citi Field on Saturday for Mental Health Awareness Day, a concept whose mere acknowledgment by MLB would have been unthinkable in the days when Generation K stumbled across the earth. Between innings, he talked about his struggles with Steve Gelbs, offering an admission that struck me for its honesty: He’d felt anxiety bubble up for the ceremonial pitch. (I saw that later; at the time I was listening on radio, and Howie Rose did a nice job discussing not only Pulse but also the work of Allan Lans as the Mets’ long-ago team psychiatrist.)

Pulsipher and Lans were pioneers of a sort; these days baseball specifically and all of us in general are wiser and kinder about acknowledging mental health issues and treating them as real things to be dealt with like any other injury, instead of dismissed as weaknesses or failures. Pulse threw out the first pitch; the Rockies’ Austin Gomber and Daniel Bard have been open about anxiety and seeking treatment. That’s progress, though more is needed — no family or circle of friends is untouched by mental health, and the sooner we remove the stigma from such discussions, the easier it will be for those we love to open up, reach out and get help.

And there’s another context for Bill Pulsipher: His June 17, 1995 debut was the first meeting for a pair of Mets fans who’d become friendly while working through their Met-related angst on an America Online message board. I’d just moved from Maryland to Brooklyn and the Mets’ prized prospect was coming up to the big leagues, so Greg and I made plans to meet at Shea. (Trivia time: In some alternate universe this blog is called Meet Me at Gate E.)

Pulse’s first pitch went to the backstop and he gave up five in the first as the Mets bowed to the not-yet-exiled Astros. Not exactly the starting point of a glittering career, but it did cement a friendship, which led, a decade later, to the blog you’re reading today.

by Greg Prince on 6 May 2023 10:43 am The primary bus scene in Bull Durham, the one in which wise, older Crash Davis informs young, wild Nuke LaLoosh that nobody gets woolly, rushed across the strike zone of the mind Friday morning, specifically the line, “You could be one of those guys.” One of the realest-life Nuke LaLooshes to have toed a rubber in the Show since the realest-seeming baseball movie ever made was released had just announced his retirement. That pitcher, the real one, was born slightly nine months after that film opened in theaters. It was as if Matt Harvey’s parents came home from the cinema and decided to create a baby toward whom the gods would reach down and turn his right arm into a thunderbolt.

Make no mistake about it: Matt Harvey was One of Those Guys. In the Show, nobody could hit Matt Harvey’s fastball. Nor could they touch his ungodly breaking stuff, let alone his exploding slider. That mastery and mystification of major league hitters didn’t last forever, but at its peak — a span measuring what felt like the greatest 27 days of our life, spread out roughly every five days over the course of one early April to one late August (26 in the regular season, one in an exhibition that lived up to its billing as the Midsummer Classic) — Citi Field was a cathedral. In 2013, now suddenly a full decade ago, anywhere Matt Harvey pitched approached holy site status.

There’d be more pitching beyond 2013, the year of Harvey Days. Some of it proved quite sublime. One night of it we either wish could have lasted a tad longer or, maybe, been cut off a batter or two before it went awry. Matt Harvey pitched us to the 2015 World Series. He had company and he had help, but it doesn’t feel wrong to credit Matt as the driving force. The World Series was a destination that was difficult to imagine in the summer of 2012 when the Mets were in the midst of a meandering bus trip to nowhere, but it may have begun to come ever so slightly into imagination’s view when the rookie righty made his major league debut in Arizona and blew Diamondback after Diamondback away.

The taste he gave us across ten starts in ’12 whetted our appetites for ’13. The Mets were still driving in circles in ’13, but you could begin to discern an off ramp. Just pull over to the right shoulder so we can get a sense of where we’re going. Y’know what, can we just let Matt drive us? We would, in fact, ride the homegrown highway of pitching to an October that suddenly burst onto our GPS. Matt Harvey was the first exit to a most rewarding trip. We’d pick up speed when we’d pick up other arms to aid and abet him, but the starting started with Harvey.

Those were the Harvey Days, my friend. Even with hindsight, we thought they’d never end.

There’s a statue of Tom Seaver outside Citi Field since 2022. There could have been a statue of Tom Seaver outside Citi Field since 2009. There could have been a statue of Tom Seaver outside Shea Stadium while Tom Seaver was pitching inside Shea Stadium. When you start talking Met starting pitchers, particularly righthanders who led the way to better days, you start with a high bar. Seaver wasn’t just One of Those Guys. He was the guy where we were concerned. Still is. After Seaver stopped pitching for us in 1983, only one righthander neared and occasionally cleared that bar: Dwight Gooden, who came along in 1984. Gooden had Friday nights in particular and a couple of years when every day he pitched was Friday night. If he didn’t maintain a Seaverian peak quite as long as Tom did, Doc’s right arm resided in the same league long enough. He was a Show unto himself.

Gooden’s last Met pitch was thrown in 1994. Doc wasn’t quite Doc by 1994, but you could watch him and remember. The Mets developed some quality righthanded pitchers over the quarter-century that followed Doc’s mid-’80s apex, but for the most part, they generated as much electricity as a hamster wheel. If you wanted to light up Shea, you signed a free agent like Pedro Martinez. Actually, there wasn’t anybody else like Pedro Martinez, and even the great Pedro could be fully like Pedro for not much more than a veritable blip once he accepted our friend invitation.

No, you want to develop your own righties. Lefties, too, but since Seaver, we’ve led with our right arms. It’s a Met thing. Or it was. From the denouement of Doc to the post-Pedro period, we came up with what righty starters from our minors? The cream of the crop included Bobby Jones, Jae Seo, Mike Pelfrey and Dillon Gee. Good guys, but none among them One of Those Guys. Paul Wilson could have been had injury not befallen him way too early. Jason Isringhausen sure looked like he was gonna be One of Those Guys, but injury rerouted him to relief and success elsewhere.

Matt Harvey comes up in 2012, two years after the Mets drafted him in the first round in 2010, and by 2013, there’s no doubt he’s One of Those Guys. Three more guys who you deem in the same vicinity as Matt follow in rapid succession: Zack Wheeler, Jacob deGrom and Noah Syndergaard. With a rotation like that, our bus could really start rolling. It’s not quite as neat as all that in practice, because by 2014, while Wheeler, plucked young from the Giants, is still learning command; and deGrom is convincing the brass he’s not here to merely soak up innings while Rafael Montero gets his big break; and ex-Jay farmhand Syndergaard wonders why nobody’s calling him in Las Vegas, Harvey is sidelined altogether, rehabbing from Tommy John surgery. That’s why 2013’s span of best days of our life ends in late August. The last time we see Matt is on a sunny, shadowy Saturday at Citi. He’s facing the Detroit Tigers. Max Scherzer is pitching for them. They’d both pitched in the All-Star Game in the same park the previous month. Everything is unprecedented about this matchup, especially how not quite right our righty looks on the hill. The Tigers, who are playoff-bound, keep hitting Matt. Matt scatters as many as he can, but something is off. It’s his elbow. It will need to be repaired.

We’d miss Harvey Day like a phantom limb in 2014. We’d get Matt back in 2015 and still talk up Harvey Day, and there’d be some splendid numbers and performances, but the One of Those Guys era ended that August afternoon in 2013. Matt could do no wrong to that moment. Or if he did wrong, we didn’t sweat it. He evoked Seaver and Gooden. They were our big three. A dominant righthander of our very own is what we came for roughly every generation. We had to skip a generation from the mid-1990s to the early 2010s. Harvey brought it back to us all at once.

Then the gods took it away from him and us, bit by bit. Again, heckuva year in ’15. Matt clinched the division title in Cincinnati. He settled down after a bumpy second inning to go five and notch the win the first time a postseason alighted at Citi Field, Game Three of the NLDS versus the Dodgers. He quashed the Cubs in the opener of the NLCS that followed. Of course he was given the honor of starting the World Series for the first Met pennant-winner in fifteen years. Of course he didn’t want to leave the last Met World Series game the Mets have played since then, eight years ago, when he’d shut out the Royals for eight innings. Terry Collins had a different idea. Matt Harvey changed his manager’s mind.

He couldn’t change history, though. You thought he might. He’d been One of Those Guys so effectively that you wanted to see him do it a little more. He couldn’t. He never would again. Damn.

Matt Harvey’s Met career ended in the bullpen in May of 2018, and not as a reborn closer. He was excess pitching inventory at the unseemly end. It had been over between him and us for going on three seasons. None of really wanted to admit it. Matt’s big league career continued a few more years with a few other teams. He last pitched in the majors in 2021. It’s 2023, the year Matt Harvey, 34, announced his retirement. He’d been through a lot. He gave us his best. His best was frigging phenomenal. We should remember that.

In the first game the Mets played after Harvey confirmed he was done, the Mets looked alive. A righthander pitched. This righty, a rookie (but not really), doesn’t mind flashing a logo advertising a personal brand on his gear. In Kodai Senga’s case, it’s a ghost, for his signature pitch the ghost fork. It’s all in good fun. The Dark Knight imagery Matt took up was fun for a spell, too. The Mets very much needed an outstanding start from Senga after Scherzer imploded on Wednesday night and Justin Verlander needed an inning to get right on Thursday afternoon. The Mets had lost four in a row. Kodai wasn’t imported from Japan to be the stopper, but on Friday night at Citi Field, he had to be at least an approximation of One of Those Guys.

And he was. Senga went six innings and permitted no runs. Walked four, but no base on balls became a Rockie run, so no problem. Kodai gave up only two hits and had all his pitches, not just the animated one, working. Like many of the fine righties who have preceded him as Met starters, Senga went largely unsupported by his offense. But not wholly unsupported, as Brandon Nimmo, the goat rather than GOAT of Thursday’s ninth inning, went deep in the fourth inning to provide his pitcher a 1-0 lead. Nobody else in the Met lineup did anything nearly as useful, but that’s why you pay for pitching. No runs given up by Senga over six; no runs given up by Drew Smith in the seventh, David Robertson in the eighth or Adam Ottavino in the ninth. Colorado seemed poised to close in those last couple of innings, but our bullpen corps stiffened. I was a little worried when I saw 2015 Royal Mike Moustakas come out to pinch-hit for the Rockies. Moustakas was the batter coming to the plate when Collins finally pulled Harvey from the mound in Game Five. The 2-0 lead had been trimmed to 2-1. Versus Jeurys Familia, Moustakas grounded to first, advancing Eric Hosmer to third. A blink later, it would be 2-2. Matt Harvey, who’d striven to the point of resistance of authority to complete a World Series shutout, got a no-decision.

Back in the present, Moustakas struck out versus Ottavino for the second, unproductive out of the ninth, and Charlie Blackmon lined to Starling Marte to end the game with the potential tying run on third. Four Mets pitchers had shut out the Rockies, 1-0. I shunted aside the regret-laden memory of Moustakas and Hosmer and all those dratted Royals and replaced it with the recollection that I was in the park to watch Matt Harvey shut out Colorado all by himself on one of those Harvey Days in 2013. It was the first shutout of our ace’s career. Blackmon singled with two out in the ninth that August night for the Rockies, but the 24-year-old Met righty popped up Troy Tulowitzki to successfully finish what he’d so brilliantly started. We didn’t know it at the time, but it was Harvey’s final win of 2013. We also didn’t know and couldn’t have guessed it would turn out to be the only shutout of Matt’s career, postseason included.

We expected more, but it was just one of those things.

National League Town licked its wounds after a band of Tigers scratched and clawed the Mets. Listen to what that sounds like here.

by Jason Fry on 4 May 2023 10:17 pm I know nobody wants to hear it, but Justin Verlander didn’t pitch that badly.

Even I don’t particularly want to hear it. I’m up in New England, running around doing nonsense, and so on Thursday afternoon I got MLB At Bat fired up a little late and this was more or less my reaction: Waitaminute, 2-0 already? Back-to-back homers? Ya gotta be kidding me.

I was stewing. You were stewing. Verlander, one presumes, was stewing. (Hey, at least I got to recap a game — my last three had been rained out, which I’m pretty sure is a Faith & Fear record.)

Nothing bad happened after that — in fact, a lot of good happened, and you don’t even need to squint to see it that way. Verlander was throwing 95/96, unlike his fellow former Tiger Max Scherzer, now officially the subject of worries. He worked out of a couple of jams by throwing hard and throwing smart in equal measure. He seemed physically sound. All to the good, particularly given the perilous state of the Mets’ rotation.

What wasn’t good was that the Mets were all but helpless against Eduardo Rodriguez — I’d make a cheap “who the heck is Eduardo Rodriguez?” crack except off the top of my head my list of Tigers would be a) Javier Baez, from whose bat an excess was heard this week; b) the decaying corpse of Miguel Cabrera; and c) uhhhhh. Well, the jokes on us — that collection of no-names just swept the Mets behind a comeback, a bludgeoning and a tight game that never felt tight. On Thursday the Mets never had a runner reach second — Tommy Pham and Brandon Nimmo were thrown out attempting to achieve this modest feat, with Nimmo’s erasure coming, for some unfathomable reason, in the ninth with Starling Marte as the tying run. (Buck Showalter likened the decision to a guy trying to make a 30-foot jumper, and I can’t improve on that.)

The Mets are now 16-16, and their mediocrity understates what a confounding season it’s been. The team either looks unbeatable or inept, with little in between, and the best description of that I can think of is “exhausting.”

There’s hope, of course — only the terminally cynical or conspicuously unserious write off a team before Mother’s Day — but at least for me, even that hope comes with a side of disgruntlement. The Mets’ biggest reason for hope is of course the fact that there are now 22* wild cards in addition to playoff spots obtained more or less honestly, which means all manner of flawed teams will make the playoffs and then hope, perfectly reasonably, to ride a handful of small-sample-size coin flips to a title.

We’re a flawed team, but probably not one so flawed it can’t clear that middling bar. The question that’s creeped into my head of late, whispering in a voice I don’t like but haven’t been able to silence, is how much of an accomplishment that actually is.

* This number may be incorrect, but ask me if I give a fuck.

by Greg Prince on 4 May 2023 11:38 am The Wednesday morning news where Detroit was concerned was good. The Spinners, the enduring, melodious R&B group out of Ferndale, Mich., had made it at last to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Their most fervent fans — a cohort that surely includes me — had been waiting what felt like forever to hear they had been chosen. Imagine how long “like forever” that felt to Henry Fambrough, the last surviving founding member of an outfit whose roots date to the 1950s. Fambrough is about to turn 85 and only recently retired from performing. He’s been out there, on the road, with dedicated, talented successors to the late Billy Henderson, Pervis Jackson, Bobby Smith and Philippé “Soul” Wynne. Those five legends will be inducted by the Hall as the classic lineup from the heart of the 1970s (“I’ll Be Around” to “Rubberband Man”), but props are also in order for John Edwards, who succeeded Wynne when Wynne left for a solo career, and G.C. Cameron, who Wynne had succeeded.

Wynne, de facto front man for the quintet during its prime, joined the group as the Spinners were about to achieve their trademark success under the guidance of producer Thom Bell at Atlantic Records, but it is Cameron’s voice you hear most prominently on their first true pop hit, the pre-Atlantic “It’s A Shame” from 1970. The real shame is that it took the Spinners as long as it did to score that radio breakthrough, given that they were signed to a label otherwise known for launching superstar acts.

The Spinners were on Motown. Usually when Motown is invoked, America feels a warm glow reflecting on all those fantastic vocal groups it gave us. And why shouldn’t we? The Supremes. The Four Tops. The Temptations. The Miracles. The Jackson 5. (Not to mention solo acts like Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder.) Somewhere down the deepest roster music may have ever known, never getting much of a chance to show their stuff while Berry Gordy was turning Motown HQ into Hitsville U.S.A., were the guys from Ferndale. They were not a priority. In short, Motown didn’t know what to do with the Spinners. They had to leave Detroit to reach the big time — if they weren’t Motown’s Nolan Ryan, they were at least their Amos Otis. The Spinners, from right there in Michigan, would become known as the leading practitioners of Philly Soul. “It’s A Shame” amounts to a footnote in the hallowed label’s discography.

The Spinners, while still at Motown. Like the Mets, they didn’t really score enough in Detroit. Hence, when Motown is invoked, my warm glow is tempered by a bittersweet chill. You had the Spinners, you all but ignored them for the better part of a decade, you let them get away. Fambrough had to wait until his mid-eighties to be told his music qualified as immortal? He had practice waiting. Motown made his group cool its heels, standing in the shadows of everybody else. I was elated and emotional when I learned the Spinners were going into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame on Wednesday morning, but, as with the family of Gil Hodges having to absorb election after election of disappointment before he finally got into baseball’s Hall, I found it hard to forget that so much for the Spinners could have come sooner.

***The concept of a wasted opportunity in Detroit was therefore top of mind come Wednesday afternoon and Wednesday evening. A visit to Comerica Park, coupled as a day-night doubleheader after rain on Tuesday, theoretically provided a better-than-even chance to pile up wins. The Tigers entered this series 10-17 and in the midst of essentially a seven-year losing streak. Every day, however, is a new day. With two chances to win, the Mets went back to their hotel with a pair of losses.

It’s a shame, indeed.

The lightly attended day portion was the shamier half of the festivities. The Mets seemed to have handle on that one, leading, 5-4, after falling behind early. Joey Lucchessi had straightened out after gophers got loose on his ledger. Eric Haase bit him for a three-run homer in the first and Old Friend™ Javy Baez led off the fourth to nip him again. With five more frames scheduled plus nine come nighttime, Joey the Churve could have continued to chomp up innings, but Buck Showalter removed him because he might need him Sunday against the Rockies…which is what Met starting pitching has come to, treating Lucchesi four days in advance like he’s Randy Johnson in Game Six of the World Series, coming out with a big lead after seven because he might be needed the next night to close out a dynasty.

Say goodbye to Joey the Churve, say hello to Jimmy the Yak, and Jimmy the Yak — Jimmy Yacabonis on your scorecard — was a beast: nine Tigers were claws poised to do damage; nine Tigers tiptoed to their dugout ready for a mid-afternoon nap. Maybe you could have your Churve and eat it, too. The Yak made Buck look like a bigger genius than Bob Melvin removing the Big Unit 22 years ago. It helped that in the half-inning interval between Lucchesi and Yacabonis, the Mets had wrestled the lead from the Tigers, boosted by Francisco Lindor’s fifth homer of the season and the Mets’ third of the day. Tommy Pham and Mark Canha had previously gone deep in a ballpark previously known as stingy for allowing home runs. Bring in the fences and watch the balls fly out.

The Mets’ penchant for assuring they wouldn’t be swept in a doubleheader got pinched in the eighth. Adam Ottavino, perhaps rusty from not pitching much since going on paternity leave or sleepy from having become a new father, was not sharp. He gave up a single and a steal to Matt Vierling; hit Baez; allowed both runners to move up on a groundout; and succumbed to the newest Metkiller to haunt our dreams, Haase, he who knocked in each of his teammates from whence they stood on base. Suddenly, the Tigers were ahead, 6-5. Alex Lange came on to save it and was successful.

If the Mets wanted to maintain their freakish string of going no worse than 1-1 on days with two games, they’d have to take the nightcap. Good thing they had Max Scherzer returning to the mound…is what you might have said before Scherzer actually pitched. The legendary former Tiger ace (we have a couple of those) was rustier and flatter than Ottavino. Max hadn’t pitched since his suspension for sweat and rosin nearly two weeks before, and before that, he had been sidelined by back issues. So maybe that’s it. Let’s say that’s it. To say worse — like at 38 and in a sped-up world of pitch timers, the aging Max is not physically equipped nor mentally prepared to grapple with the current state of baseball — is just too depressing. Haase homered again. Vierling homered. Max gave up six runs, all earned, in three-and-a-third.

The Mets didn’t do much to Tiger starter Michael Lorenzen. We got one run, driven in by Daniel Vogelbach, the designated hitter. Maybe if they designated every Met a hitter, our hitters would better understand the nature of what to do while attempting to hit. Lefty reliever Zach Muckenhirn made his debut for us, and it didn’t go badly. Muckenhirn is the 1,197th Met overall and, barring who knows what before today’s first inning, will always have the pleasure of knowing he will always sit directly above prospective Met No. 1,198 Justin Verlander on the franchise’s all-time chronological roster. Jose Butto also successfully soaked up excess batters, which is all one can ask of a person announced in advance as the 27th man in an endeavor that usually encompasses 26 men. “Hey, Lastie, they’re puttin’ ya in!”