The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 5 December 2022 4:00 pm What I have in common with Baseball Hall of Famer Gil Hodges I could count on very few fingers, but it delights me that one of them is a ring finger. Gil earned three World Series rings, two as a player in 1955 and 1959, one as a manager in 1969. I was presented with what is likely the closest thing I’ll ever claim as a championship ring on Saturday, and it wouldn’t have been possible without Gil Hodges.

Saturday brought around the more or less annual Queens Baseball Convention. QBC has been a staple of the offseason calendar since January of 2014, except when a blizzard canceled it in January of 2016, a Mets-run fanfest in January 2020 rendered it temporarily superfluous, and that pandemic business discouraged crowds from populating indoor spaces a winter later, no matter how much that crowd might have loved the Mets. Other than those pauses, QBC has marched on. Different months some years. Different venues other years. This year it was December in downtown Flushing, at a hotel located a relatively convenient walk (albeit through rain and wind) from the final stop on the 7 train. I almost never take the 7 east of Mets-Willets Point. On Saturday I did and noticed that as you pass Citi Field (the parking lot of which has been transformed into a glittery Christmas village), you get a generous glimpse of the left field Promenade and a full-on view of all those retired numbers the Mets suddenly sport, as if they have a real and proud history.

Which they do, which explains why, other than for fun, I was heading to QBC. My primary role at this offseason gathering spot is to present the Gil Hodges Unforgettable Fire Award, a token of fan recognition for keeping the Met-aphorical torch lit. Recipients prior to this QBC have included Gil himself (presented posthumously to his son Gil Hodges, Jr.), Ed Charles, Bud Harrelson (presented that summer at the Long Island Ducks’ pond in Central Islip, a contingency necessitated by the aforementioned blizzard), Tom Seaver (who couldn’t be there, but his teammate Art Shamsky graciously swung by to pick it up and later bring it to Tom in Napa), Bobby Valentine, David Wright (who accepted it via classy video) and the late communications specialist and friend to all Shannon Forde (with her family on hand to help us pay tribute to her memory). Real and proud history, indeed.

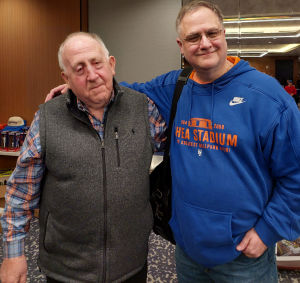

One of the reasons we can feel proud of the Mets, despite sometimes being, you know…the Mets, is the man who holds the titles vice president of alumni relations and team historian for that organization so close to our heart, Jay Horwitz. You can’t ride the rails to Flushing-Main St. and grab that peek at the rafters and not get a sense of some of the work Jay has done. A few years ago it took less time to read the numbers up in the rafters than it did to confirm that there’d once again be no Old Timers Day. Since Jay was appointed to his current positions, we’ve seen three numbers added to the four that sat waiting too long for company. We’ve also stopped confirming that the Mets would never again have an Old Timers Day, because, thanks to Jay’s leadership, Old Timers Day returned in 2022 for the first time since 1994. The vibe associated with the Mets as an entity that lived in the present, was clueless about the future and pretended there was little past to them has done practically a 180 since Jay shifted from public relations to alumni relations. We have a present. We have a future. We salute our past.

That’s worthy of an award. That, the folks who put together QBC decided, was worthy of selecting Jay Horwitz as this year’s recipient of the Gil Hodges Unforgettable Fire Award. They courteously asked me if I agreed. I did. They doubled down on courtesy and asked me if I would present the award to Jay. I agreed to that, too. I’m always up for the ceremonial aspects of baseball. To be a part of this one particular ceremony more or less annually gets my torch lit as is. To do this presentation in the wake of reaching one of the goals of establishing the Gil Hodges Unforgettable Fire Award — contribute in whatever way possible to keeping Gil’s name on people’s minds until he was elected to the Hall of Fame — made the Hot Stove flame burn that much brighter for me.

So through the rain and wind I clomped from the final stop on the 7 to the hotel a little north of Northern Blvd. (getting flummoxed by construction for a few minutes before I found the entrance), shook out my umbrella, stepped into the men’s room and waited to wash my hands behind somebody using the sink on the right when I heard somebody using the sink on the left tell the man using the sink on the right, “IT’S YOU!”

I was standing behind Endy Chavez. Because that’s the sort of thing that happens at QBC. Endy said to the other fellow, “yes” and smiled. When my turn came to wash my hands, I soaped, rinsed and dried quickly so I could casually follow Endy out of the men’s room and blurt the first thing that occurred to me:

“It’s an honor to share a men’s room with you!”

I think Endy smiled. And perhaps picked up his pace to get away from me.

Just a couple of guys who’ve written Mets books (thanks to my friend Jessie for introducing me to R.A. Dickey). Endy Chavez! R.A. Dickey! Howard Johnson! Bartolo Colon! Nelson Figueroa! DOC GOODEN! Those were the players who were at QBC in one capacity or another. Well, one capacity above others: they were Mets among Mets fans. That goes over pretty well, especially when it’s barely half-a-day since we learned one Met chose to no longer be a Met among Mets fans, even if we agreed to keep our distance and not follow him into or out of men’s rooms. Let’s just say “Jacob deGrom” was no longer a surefire applause line in this environment.

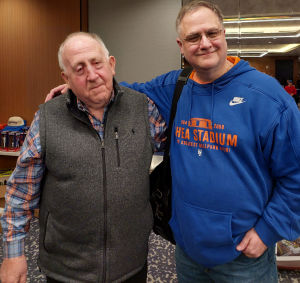

The departure of deGrom (before we knew about the arrival of Verlander) didn’t put any more of a damper on this event than did the howling rain that lasted into mid-afternoon. That was outside. Inside, warmth was in the forecast. People talked Mets. People listened Mets. Mets fans renewed acquaintances. I ran into Dave, a guy I knew in high school. Then, we were two Mets fans happy to find anybody who’d identified as such. There weren’t many of our kind in those days. On this day, “Mets fans” described everybody in sight. For all the procuring of players’ presence, and Mets themselves are certainly a draw, I don’t think it’s the chance to score an autograph or a photograph or even a men’s room sink encounter that makes QBC click. It’s me in my SHEA STADIUM THE GREATEST BALLPARK EVER! hoodie running into Dave from high school in his SEAVER 41 jersey, introducing me to his son who’s a bigger fan than he is, even if unlike his dad and me, he’s still waiting for a world championship — it’s that interaction multiplied by who knows how many hundreds of times in the course of a Saturday. Mets fans running into each other is the lifeblood of a day of this nature.

And, a little bit, it’s prime QBC movers Keith Blacknick and Dan Twohig — aided in their heavy lifting by a raft of volunteers in cleverly designed t-shirts — carving out a few minutes to make sure we talk about Gil Hodges and Mets history. That’s where I come in, and that’s where my championship-style ring comes with me. See, I’m enjoying my impromptu reunion with Dave from high school when Dan pats me on the shoulder and lets me know I’m up next. I excuse myself and, within a couple of moments, I’m sitting on the dais, next to Jay, promising him that I plan to embarrass him with praise any second now. I’m also looking out on the crowd, as we wait for people to sort themselves out after HoJo has given of himself generously in his panel (moderated elegantly by WFAN host and fellow Mets fan Lori Rubinson). In the first row, there’s Irene Hodges. Jay introduced me to Irene, who I recognized from her speech inducting her father at Cooperstown this summer. I shook her hand and thanked her for that. I’m thinking she’s probably heard something like that before, but then again I’m pretty sure HoJo, R.A., Bartolo, Figgie, Doc and Endy have heard what they’re hearing all day before, give or take the men’s room sentiment. I’m gonna guess that they don’t altogether mind the repetition or enthusiasm for aging accomplishments. They agreed to come to a venue for the express purpose of being recalled lovingly to their faces.

Lest we forget, Jacob deGrom’s Met legacy includes the foreword to an Amazin’ memoir. I’m there for the express purpose of remembering Gil Hodges lovingly. Irene is there to support Jay, which tells you something about Irene as well as a good deal about Jay. Jay stayed in close touch with the Hodges family through the long, long wait for good news from the Hall of Fame. He was a true friend to Mrs. Joan Hodges. He’s a friend to Irene. He’s a friend to more Mets and Mets-affiliated folks that can be counted. If you wanted somebody to say something nice about Jacob deGrom on Saturday, you needed only to turn toward Jay Horwitz if you were lucky enough to be sitting next to him on a dais as you waited to make a formal presentation. Jacob, I reminded him, wrote the foreword to his memoir. Through a bit of a pained expression, Jay acknowledged deGrom’s defection (my word, not his) but wanted to remind me “Jacob’s a very good person.” Well, I said, at least you have another Met alumnus now.

As the room settled down, Dan the co-organizer stood with a mic for a moment and made an announcement. He explained what we were about to do, said a few words about the transcendence of Gil and the worthiness of Jay and that he was about to turn it over to me, but first, he and Keith had something for me: a ring, in appreciation for being QBC’s resident “historian” since the “by the fans, for the fans” fanfest hit the drawing board nearly a decade ago. The ring bears the logo of QBC and evokes the kind of jewelry one receives for winning a title. My title is fan who gets to do the Gil Hodges Unforgettable Fire Award presentation more or less every winter. I wasn’t expecting a ring for doing it. When you’re a Met fan, you learn to never expect a ring, though when one does slip onto your finger, you’re most grateful for what it represents.

It’s not all about the ring, but it’s pretty nice getting one. I’ve toggled between referring to it for my own amusement as the Gil Flores Unforgettable Fire Award (don’t tell me you’ve forgotten the outfielder who roamed THE GREATEST BALLPARK EVER! when Dave and I were in high school) and the Royce Ring Ring (an homage to both our Closer of the Future c. 2005 and the hastily arranged Francis Scott Key Key from the “Privateers” episode of The West Wing), but mostly I’m touched that Keith and Dan paused amid taking care of the umpteen-thousand details necessary to put on a show of this magnitude and give me this other pat on the shoulder. Or ring finger. Thanks very much, guys. Thanks to everybody who takes a few minutes from roaming around and gabbing excitedly and queuing up for autographs to listen to me doing my Mets historian thing, particularly when I’m doing it with the guy who actually is the Mets historian.

The following is the text I wrote and delivered at this year’s Queens Baseball Convention in honor of Gil Hodges and Jay Horwitz (who made his acceptance remarks all about Gil, because that’s who Jay is). I hope you enjoy it.

***As we close out the 60th anniversary celebration of our New York Mets, I want to wish all of us a Happy Mets Anniversary in the year ahead. Every year is the Mets anniversary of something. In 2023, we will be marking…

• The tenth anniversary of peak Harvey Day and the All-Star Game Matt Harvey and David Wright started at Citi Field;

• The twentieth anniversary of the first base stolen by Jose Reyes and the last broadcast by Bob Murphy;

• The thirtieth anniversary of Anthony Young persevering until he finally won a game after losing 27 in a row;

• The fortieth anniversary of the days we got to Shea hello to Darryl Strawberry, Keith Hernandez and Ron Darling;

• The fiftieth anniversary of Tug McGraw instilling within us the evergreen philosophy, You Gotta Believe;

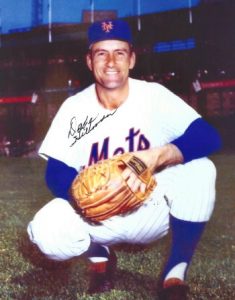

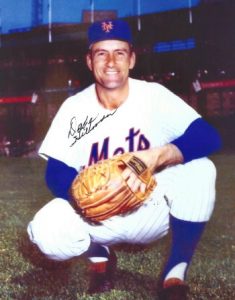

• And the sixtieth anniversary of a ninth-inning, two-out ground ball to shortstop Al Moran from Jim Davenport of the San Francisco Giants to end the nightcap of a doubleheader at the Polo Grounds on May 5, 1963, a Mets victory sealed when Moran fielded it and threw it to a first baseman you knew would handle just about anything coming his way.

The Mets’ first baseman was Gil Hodges. It was the last play Hodges made in the major leagues, twenty years after his debut for Brooklyn. Gil was an achy 39 in May of 1963, about to be done as an active player. By the end of the month, he’d be traded to the Washington Senators, who immediately appointed him their manager. It was a very quick transition and, from our perspective, made for a very useful apprenticeship. Following the 1967 season, Gil would be traded again, as a manager, back to the New York Mets, and I think we know where this transaction — and this man — would lead us.

When the Queens Baseball Convention conceived of an award to honor members of the Mets community past and present for making us forever proud to be Mets fans, there was only one name that could instantly describe its inspiration: Gil Hodges. At the same time, QBC wanted to make a point of at least once every year calling as much attention as possible to the name Gil Hodges.

Gil, you probably remember, had missed making the Hall of Fame too many times despite being one of the top run-producers and THE premier defensive first baseman of his time before managing the 1969 New York Mets to the most unlikely world championship ever. Not in the record books: the universal esteem in which EVERYBODY in baseball held this man. So we thought maybe, just maybe, we could add our voice to an already strong chorus and raise the volume, however slightly, in service to making sure the unforgettable fire Gil Hodges represents in our Met story would remain lit for all to see.

One year ago this weekend, the fondest wishes of QBC and Mets fans everywhere — really, baseball fans everywhere — came true, and Gil Hodges was elected, AT LAST, to the Baseball Hall of Fame. We got to witness it, his children got to witness it, and, in Brooklyn, Mrs. Joan Hodges, 95 years old and waiting a half-century for the phone call that affirmed the news, got to witness it, and we are so thankful that she lived to see her husband’s election and induction.

I can’t tell you what a thrill it is to sit up here and refer to this symbol of QBC’s affection for contributions to what has made the Mets the Mets in the best sense of the word for more than six decades as the Gil Hodges Unforgettable Fire Award — and to add, it is named for Baseball Hall of Famer Gil Hodges.

I have a feeling Gil would nod in approval at this year’s recipient. This person has given his all to make the Mets better in every way he possibly could. He’s been a team player as long as he’s been with the team. He’s kept the fire burning when it comes to Met history meeting the Met present.

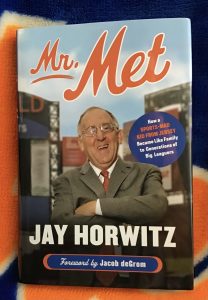

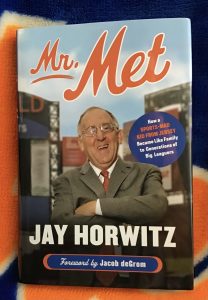

He’s Jay Horwitz, the “sports-mad kid from Jersey,” as the cover of his book “Mr. Met,” foreword by Jacob deGrom, identifies him. Of course he’s from the METropolitan Area. Of course when you see him you think of him as the embodiment of the New York Mets…no offense to the other Mr. Met.

I was a sports-mad kid from Long Island when I first learned who Jay Horwitz was. He’d been in his job as Mets public relations director for less than two months when a Mets game from Pittsburgh went into rain delay, as so many Mets games from Pittsburgh do. While the tarp sat on the field and before Channel 9 fired up — as they invariably did in these situations — the 1969 World Series film and the 1973 World Series film, they needed to fill some time. Thus, invited into the Three Rivers Stadium visiting television booth, alongside Ralph Kiner and Steve Albert, was this fellow who on first glance I mistook for Marvin Kaplan, the character actor who played Henry the lovable telephone repairman on Alice, if that rings a bell.

This guy, however, wasn’t an actor. He was a genuine character. Jay slides into the booth and enthusiastically explains to our announcers and those of us at home that he just came to the Mets from a similar role at Fairleigh Dickinson University, but never mind his story, because he wants to let everybody out there in TV land know what an incredible assortment of personalities is dotting the 1980 Mets roster. Did you know, he asked Ralph and Steve, that Craig Swan has a green thumb for gardening, that Lee Mazzilli was an Olympic-level speed skater, that Doug Flynn has a flair for country music? Jay used his moment in the sun, or technically the rain, to put the players he represented in the best, most fascinating light he knew how, keeping us as Mets fans watching and wanting to know more.

And he’s continued to do exactly that ever since. Jay handled Mets PR for nearly four decades, which meant serving an array of constituencies: a necessarily demanding, deadline-tethered media he strove to inform while building their trust; the hard-working members of his own staff — we were fortunate to honor one of his most wonderful protégés, Shannon Forde, last year; the individuals and groups who benefit enormously from having a friend in Flushing — a shining example being all Jay and the Mets have done and keep doing for the families who lost loved ones in the tragedy of September 11, 2001; the club owners, the front office, FOURTEEN different managers, and hundreds of players who couldn’t help but maintain specific preferences regarding what they wanted or didn’t want publicized; and, in the end, the fans who got to understand the team better because Jay worked so hard to put the Mets in a good yet realistic light. Through no more than simply doing his job, I’d say Jay became as recognizable a face to Mets fans as any Mets player between 1980 and 2018. More recognizable than Marvin Kaplan, certainly.

In 2018, Jay took on a new role, one that was crying to be created, one that he was born to fill, directing Met alumni relations. His efforts and the fruits they have yielded have been a revelation for everybody who cherishes this team, as Jay has connected those of us who love the Mets with Mets who might otherwise not realize that we’ve kept them in our hearts long after they’d played their last game.

Jay won’t take credit for Old Timers Day, and no doubt everybody from current ownership on down helped him make it happen, but give Jay credit for Old Timers Day, the first one the Mets had held in 28 years. Having someone so dedicated to “his players,” which at this point is everybody who’s played for the Mets since 1962, was the difference-maker in bringing us to a party that was unprecedented in Met annals and an event that was SORELY missed by Mets fans in the decades it was absent. Jay also provided a guiding hand in so many of the other signature historically minded moments of 2022: the commemoration of Johan Santana’s no-hitter; the overdue unveiling of the Tom Seaver statue; the overdue retirement of No. 17 for Keith Hernandez; the LONG overdue retirement of No. 24 for Willie Mays; and, through his fervor for a goal we all held dear, the LONG, LONG overdue election of Gil Hodges to the Baseball Hall of Fame. Jay didn’t have a vote, but he did have a voice, and he politely and respectfully raised it at every turn to ensure nobody should forget about Gil and that the Hall of Fame should not go another year without enshrining him.

One other gift Jay gives us on a regular basis is the Amazin’ Mets Alumni Podcast, where he showers attention on Mets and Mets personalities from 1962 forward. When Jay talks into his microphone, he speaks to the soul of this franchise. I also notice Jay introduces nearly every episode as a “special” edition, and he’s absolutely accurate in doing so. It’s truly a portal into living Mets history and I urge you to listen to it, not only because it’s a splendid show for Mets fans like us, but so Jay knows we’re hearing him. I told him once that I really enjoy his podcast. “So you’re the one,” he said. I imagine there’s lots of us, Jay.

I also imagine I could go on about a person who has brought uncommon humility and humanity to the Met cause for so much of his lifetime, but it’s my sense that Jay doesn’t really seek attention, let alone awards. We apologize for giving him both.

On behalf of the Queens Baseball Convention and Mets fans everywhere, it is my privilege to say this year’s SPECIAL EDITION of the Gil Hodges Unforgettable Fire Award goes to the one and only and unforgettable Jay Horwitz.

After the awarding, one more moment with Jay. On behalf of Mets fans everywhere, Jeff Hysen and I attempt to put the deGrom defection into something approaching perspective on the latest, hopefully special edition of National League Town. You can listen here or on the podcast platform of your choice.

by Greg Prince on 5 December 2022 1:12 pm I’ll sure miss Jacob deGrom…that is when I’m not watching Justin Verlander pitch for the New York Mets this year and next. So maybe I won’t be actively missing Jacob deGrom quite so much, dashed lifetime Met status notwithstanding.

Yes, the word is out: Justin Verlander will be a Met, landing in a different context from that which the deGrom news did less than three days ago but with the same ratio of surprise/shock to it. We can be surprised. We can’t be shocked. These are the New York Mets of Steve Cohen. Lose one all-time great, go out and replace him with another all-time great. Older, but maybe more durable in the short term. And all-time greater, truthfully. In his most recent term as an Astro, Verlander was a world champion and a Cy Young winner. It wasn’t the first time he’d been either. He comes to a new league and a new city and he’s doing it on the cusp of 40. But he’s Justin Verlander. He’s familiar with Max Scherzer. He’s familiar with getting batters out. He’s expensive, but how is that my problem? (Don’t be a mope and invoke ticket prices and cable subscriptions.)

Friday night was kind of miserable. Monday afternoon is rather ebullient. That’s the opposite of how things are supposed to work. We’re Mets fans who aren’t stuck empty-armed after losing an ace. That’s the opposite of how things used to work. We’ve got Verlander and Scherzer and, I suppose, some other spots to fill. But let’s give ourselves a respite from playing GM. Let the GM do his job. The owner has done his.

Justin Verlander is joining the New York Mets. Enjoy that for today. Enjoy that in 2023. Whatever happens in Texas can stay in Texas. Except for Verlander. He left Houston and is coming to Flushing.

We, too, move on. It’s what we do.

by Greg Prince on 3 December 2022 9:42 am All hail the free market! All hail labor empowerment! All hail the ability of the Texas Rangers to commit as many dollars and years as they choose to Jacob deGrom, and all hail Jacob deGrom’s ability to choose to take the dollars (185 million of them) and years (five, carrying him past his 39th birthday). Enabled by the miracle of the collective bargaining process, we get to see the American way in action.

Isn’t that just swell?

The Rangers figure they’ll benefit from deGrom’s right arm doing its wondrous thing for as long as it can. DeGrom will benefit from being paid at a level commensurate with his level of achievement stretching back the past five years. And Rangers fans will have a closeup view of a pitcher described regularly and with minimal hyperbole by the acronym for Greatest Of All Time.

The only people who might lose out in this scenario are us, the jilted Mets fans who will not see Jacob deGrom continue his essentially incomparable career as a Met. Nine years and out for Jacob, whom I’m no longer in the mood to refer to as “Jake” or deGOAT, for that matter. Jacob exercised his negotiated right to opt out of his contract. Leave a door open on a goat pen and bet on whether the goat will wander away (the commissioner of baseball will gladly process your gamble).

And now it is done. Jacob deGrom is a former Met. I imagine at some point the franchise pitcher on whom we hung our hat and pride since 2014, especially since 2018, will issue a statement thanking the Mets and Mets fans for their support to date. He’ll probably say something out loud when he tries on his new jersey and cap in Arlington or over Zoom from DeLand. I think he’s enough of a mensch to stand and deliver that much. Maybe it will be supplemented by a social media gesture, the contemporary version of departing free agents taking out full-page newspaper ads. We used to rely on daily newspapers. We used to rely on Jacob deGrom.

Month’s off to a heckuva start. Those were the days, my friend. Even allowing for cynicism, I kinda thought they’d never end. Why should have they? At every turn, Jacob deGrom exulted in the exultation we as Mets fans devoted in his direction. We shrouded him in our affection, we waited with longing and loving for his return from various trips to the injured list, we stood and swooned over his Lynyrd Skynyrd-scored simplicity. Sure, he’d opted out of his very nice if not absolutely nicest possible contract, but that contract was signed when the signatory on the other side of the pact was a Wilpon. You knew Steve Cohen could take care of business as needed.

Except in Texas, bidness is bidness, if you will indulge the stereotypical oil baron dialect, and their version of Cohen decided it would be great for bidness to take care of bidness to the extreme, offering Jacob deGrom those five years, which math will tell you is two more than the three the Mets apparently put out there. The average annual value for deGrom in New York was reportedly a little more: $40 million per annum versus $37 million. The total was a lot more from Texas: $185 million over five years versus $120 million over three. DeGrom doesn’t have to do math like he does pitching to do the relevant math.

The relevant emotion to a certain strain of Mets fan, perhaps best classified as the unsentimental kind, is how few innings Jacob deGrom threw between July 7, 2021, and August 2, 2022: 0. Intermittently during his Met run, particularly in the most recent years, Jacob became one of those sitcom tropes. Vera from Cheers. Maris from Frasier. Captain Tuttle from M*A*S*H.

“Anybody seen Jake?”

“Ah, ya just missed him.”

“What, again?”

“Don’t sweat it. He’ll be back soon.”

The relevant emotion to a certain strain of Mets fan, perhaps best classified as the sentimental kind, is how few innings Jacob deGrom threw from his debut of May 15, 2014, forward for any team that wasn’t the New York Mets: 0. That data point paired with the hope that Jake (had he stayed here, that’s what I’d call him) would become that rarest of birds, the elite Met starter who was nurtured in the nest and never flew the coop. We know it’s never happened before. We have learned it is not likely to ever happen again.

Once you let deGOAT opt out of his pen, there’s no telling where he’ll seek greener pastures. The “elite” nature of deGrom was never in question, save for a little collar-tugging and throat-clearing at the sight of Jake maybe running out of petrol in sixth innings as his late-starting 2022 wore on. I chose to believe he was still getting up to speed after not pitching in the major leagues for thirteen months. I chose to believe his excursions to the IL were the exception, not the rule. I chose to believe a lot in Jacob deGrom. I believed he wouldn’t leave us. You can’t always get what you believe.

You can get a replacement. You have to. Emotionally, I’d be OK with inscribing No. 48 on the Citi Field mound and everybody going home the first time what would have been his turn comes up, but business doesn’t work that way, and what would have been his turn will come up approximately 32 times in 2023. The Mets will sign some very fortunate free agent pitcher, whoever it will be. That pitcher’s negotiation position just rose substantially. We don’t have deGrom, but we do have Cohen. This takes the sting out of the news in a way unavailable to us when the Mets were under previous ownership.

It’s all still wrong, mind you. Jacob deGrom slipping into the uniform of the Texas Rangers is wrong. Somewhere in this great country, somebody thought Max Scherzer slipping into the uniform of the New York Mets was wrong, but we cheered it. His wardrobe change gave us the pair of Aces to die for. It gave us a helluva rotation in theory last offseason and in reality for a couple of months. It didn’t yield a division title or a playoff series win. That loading up of Aces worked to its fullest extent only once for Atlanta when they had Maddux, Gl@v!ne and Smoltz, and it never completely panned out for Oakland when they had Hudson, Zito and Mulder. You never know with September and October. But you liked heading into the end of a season and the beginning of a postseason with the likes of deGrom and Scherzer.

Now we’ll go into the beginning of the season with Scherzer and whoever. We’ll look back on nine years of deGrom less and less while he’s doing whatever he does as an American League Westerner. Every time I want to do one of my historical dives about Met starting pitching, there will be an implied ruefulness and an explicit wistfulness to bringing Jacob deGrom into the conversation. One year, it’s all “we” and “our” for a player you understood could take a hike but didn’t really think would. The next year, he’s “former” and “erstwhile,” and we’ve moved on because we have to. Someday down the road, far down the road if the former and erstwhile Met is lucky, he will have a reason to come back in a ceremonial, celebratory capacity. We have Old Timers Days again. At the one we had this year, we warmly greeted Jose Reyes who left to be a Marlin and Daniel Murphy who left to be a National. That, we should all live so long, comes later.

For now, it’s just business.

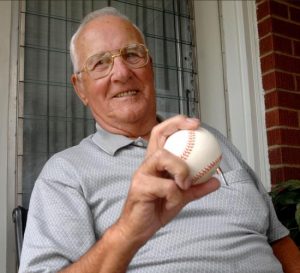

by Greg Prince on 23 November 2022 8:18 pm When Yogi Berra died in 2015, Dave Hillman ascended to the role of Oldest Living Met. Yogi Berra is among the most famous baseball figures of the past 75 years, perhaps ever. People still quote Berra, still invoke Berra, still remember Berra. He’s been gone seven years, but his legacy is likely to live on for generations.

When Darius Dutton “Dave” Hillman succeeded Lawrence Peter “Yogi” Berra as Oldest Living Met, I had almost no idea who Dave Hillman was, other than “member of the 1962 Mets,” and then mostly from looking at a list of the vital statistics I keep of Every Met Ever: birth date; date of first game as a Met; date of last game as a Met; and, where applicable, death date. Sad to say, I just the other day tabbed to the last column on Dave’s entry and made the necessary revision to his line on the list. Dave died Sunday in Tennessee at age 95, ceding his title of Oldest Living Met to Frank Thomas, 93.

Dave Hillman threw his first pitch for the New York Mets on April 28, 1962, becoming the 29th man to play for them overall. The chronological numbering is modestly significant if you want it to be. The first 28 Mets were the Original Mets who made it out of Spring Training. They won one game with that initial crew — and lost eleven. While cutting down their roster to the mandatory 25, they opted to make some changes besides. Their first in-season moves included bringing in righty Hillman, who washed out in Cincinnati following a robust season of relief in Boston.

In pursuing Dave, a friend also named Dave reminded me, the esteemed Met brain trust of George Weiss and Casey Stengel passed on the opportunity to sign none other than future Hall of Famer Robin Roberts, whose right arm at that moment was considered more done than Dave Hillman’s (the almighty Yankees dropped him), yet actually had several decent seasons left ahead of him. Had the Mets taken a chance on a four-time 20-game winner then at liberty, Robin and fellow Phillie expatriate Richie Ashburn might have shared dugout time reflecting on their Whiz Kids exploits; sizing up their Cooperstown prospects; and plotting to elevate the Mets to a record slightly better than 40-120. But that was a road the Mets were adamant about not taking. “I have spoken to Casey Stengel,” Weiss practically harrumphed, “and he is definitely not interested in Roberts.”

Robin posted double-digit win totals in 1963, 1964 and 1965. His final game in the majors came on September 3, 1966. For context, eight days later, Nolan Ryan debuted. Robin Roberts, 35 in April of 1962, lasted quite a while, Weiss’s or Stengel’s interest in him be damned. Like Roberts and Ashburn, Stengel and Weiss are in the Hall of Fame. Alas, even in the grandest of careers, not every pitch is a strike, not every swing is a hit and not every move proves the best choice in hindsight. The Mets needed a pitcher at the end of April 1962 and went with Hillman. Dave’s major league journey began in 1955 with the Cubs. He was, in the most honorable sense of the phrase, a journeyman pitcher. A journey that takes a man to the Polo Grounds and assume the mantle of (almost) Original Met can’t help but be honorable in our eyes.

The date of the first game Dave Hillman ever pitched as a Met stands as absolutely significant. April 28, 1962, marked the first Mets home win ever, over the Phillies. Jay Hook started and was hit hard. Bob L. Miller entered before the first was over and eventually allowed the visitors to extend their advantage. Dave, however, stood to be the winning pitcher after departing his one inning of work, the sixth, and the Mets taking the lead directly thereafter. The official scorer disagreed, taking into account a) the first batter Dave faced in the sixth (Don Demeter) leading off with a home run; and b) Met ace Roger Craig, the club’s Opening Day starter, coming on and throwing three scoreless innings to seal the 8-6 victory. Craig could have been credited with a save, but saves hadn’t gained official statistical traction by 1962, so Roger was awarded the win. Scorer’s discretion, as they say.

Dave Hillman, living his Met life. At least Dave Hillman was in the big leagues again and at least he took part in a New York Mets win…a historic New York Mets win. So did newly acquired Sammy Taylor and newly acquired catcher Harry Chiti. Chiti, while no Berra at or behind the plate, would become famous in a very Metsian manner a little later in 1962, returned to Cleveland when the Mets decided he wasn’t the receiver for them. The player to be named later turned out to be named the player named Chiti. This transaction went down in Originalist lore as Harry Chiti being traded for himself. Harry batted .195 and was never quoted on the subject of what to do when you come to a fork in the road (“take it” — Y. Berra), but his aftermath read as colorful.

Dave’s Met tenure left fewer footprints in franchise legend and was not much rosier in the way of statistics. He’d contribute to a few more wins and a whole bunch of losses — the song of essentially every 1962 Met — almost exclusively in relief. He notched the sixth save in Mets history. The sixth save in Mets history materialized in the Mets’ 51st game overall, an indicator less that starting pitchers went deep in those days than there weren’t many Met wins to save. Still, it was pretty clutch pitching. Dave came on in the eighth and popped up former teammate Ernie Banks with runners on, then stranded the bases loaded to finish the ninth. That the win Hillman secured improved the Mets’ record to 14-37, or that Hillman’s ERA for the year (including his stint with Cincy) hovered above 8, does not detract from a Mets win being a Mets win nor Hillman making sure it didn’t evolve into something less. In 1962, every win was sacred.

Three appearances later, Dave Hillman sported an ERA under 7, which was progress. It was also the end of the line for an eight-season veteran who’d certainly overcome obstacles to be able to put that many years into big league ball. The Mets wished to send Dave to the minors. Dave wished to move on, specifically back home to Kingsport, Tenn. — you might recognize the town as site of a long-running Mets farm club — with a career in clothes retailing in front of him. The 29th Met ever also became the seventh major leaguer to play his final game as a more or less Original Met. Forty-five players in all were 1962 Mets. Nineteen of them would never play again in the bigs after serving the 40-120 cause (Chiti, who Cleveland sent down to Jacksonville upon reacquiring him, was the sixth of them). In a 2008 interview, Hillman said of his last team, “It was a joke, the ballplayers they had assembled. It was all old players who were over the hill. There were one or two young pitchers that were good, but with the ballclub, they couldn’t get them a run.”

Dave Hillman, enjoying life after the Mets. Hillman, nearing 35, may have resembled that remark, but he wasn’t inaccurate in his scouting report. And he couldn’t be blamed for considering the path of his baseball journey, which had landed him at being told he wasn’t quite good enough for those tenth-place Mets, and deciding trying to get it together at Syracuse wasn’t his best next step. Selling clothes at a store with his family’s name on the door (Fuller and Hillman, owned by his uncle) had more of a future to it than an excursion to Triple-A. This was 1962. Eight years in the big leagues didn’t set a person up for life. Life had six more decades to it in Hillman’s case. He’d be recognized from time to time for having been a ballplayer and he’d kindly answer inquiries about having been a Met or a Red or a Red Sock or a Cub way back when, but he wasn’t, when one ventured outside the borders of Kingsport or completism, what you’d call famous.

Then the famous Yogi Berra died, and Dave Hillman may or may not have thought much about inheriting the status of Oldest Living Met, a distinction that carried with it a note of renown or at least curiosity. I’d see his name and his birth date and get a little curious. When he died at 95, I poked around a little more. The Mets were a small segment of a life that went on and on, the longest life any Met has ever known. Being a 1962 Met wasn’t necessarily Dave Hillman’s calling card. But it’s how we came to know him or know of him. We thank him for the pleasure.

***Not all expansion teams are created equal. The National League didn’t develop much practice in building them between 1962 and 1993 — there were only the Padres and Expos in 1969 — but it seems they figured out how to put together squads whose baseline was much closer to meh than Mets. The brand, spanking new Florida Marlins, for example, didn’t get spanked to extremes, going an ordinarily bad 64-98 rather than a still writing books about it 40-120. Those first Fish finished out of last place, for which they could partially thank the 1993 Mets, and they featured a bona fide league leader, for which they could partially thank the Mets of a couple of years earlier.

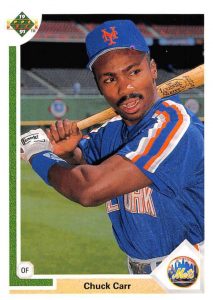

The 1993 Marlins featured atop their lineup and tearing around their bases Charles Lee Glenn “Chuck” Carr. Chuck was known in some circles as Chuckie. He’d refer to himself that way first-person style, as athletes exuding self-confidence have tended to do. He’d be referred to that way by colleagues, with varying degrees of affection or disdain. I have one overriding memory of the baseball career of Chuck Carr, a gifted outfielder who died at the indisputably too soon age of 55 on November 12, and it comes from 1993, three years after he’d broken into the big leagues as a New York Met, two years after the New York Mets decided they’d seen all they’d needed to see of him before making him a former New York Met.

It was, I’m pretty sure, from a morning in late June of ’93. The Mets were already certifiably dismal. I mean worst team money could buy dismal, and this was with cognizance that there was a book out that spring about the previous year’s Mets and it was called The Worst Team Money Could Buy. This team was worse. Much worse. But, as even the worst Met teams do, it cobbled together its moments, and one it desperately needed came at the expense of those expansion Marlins. On the night of June 29, following an extended stretch of the worst baseball I’ve ever seen the Mets play — they’d lost 48 of their previous 63 games, which translated to a winning percentage of Basically Never — they limped into Joe Robbie Stadium on a Tuesday night. They had been off Monday. On Sunday, at Shea, Anthony Young had lost his record-setting 24th consecutive decision. The Mets, not just Young, hadn’t won since the Monday before that, a victory that itself was the first since the Monday before that, which itself was the first Met win since the Monday before that. Garfield the Cat hated Mondays. The Mets by June of 1993 were the personification of them. No wonder it’s the only day when they won.

Storm clouds followed the 1993 Mets everywhere. Natch, they’d meet them upon their inaugural visit to Joe Robbie, which would become notorious for summertime rain delays over the next eighteen years, which is why they now play in Big Empty Park with a retractable roof downtown. The damp notoriety began in earnest on the next-to-last night of this particular June. It wasn’t so much that precipitation came blowing in hard on the Mets and the Marlins after three innings. It was that the grounds crew of the facility hadn’t been schooled on the proper method for unrolling and spreading out a tarpaulin. Tim McCarver grew quite amused that right field was well-tarped…which was quite an accomplishment…if that was the goal…which it wasn’t.

In assessing the left side of the infield as “absolutely inundated with water,” Tim took a page from Joe Namath’s most memorable trip to Miami. “I guarantee you,” Tim promised, “that shallow right is dry as a bone!” The men in teal tops and tan shorts missed most of the infield with their efforts, meaning a lot of futile dragging was done in a downpour before the crew rerolled and tried again. The Joe Robbie PA commented on the action like any good movie soundtrack, blaring the theme from Mission: Impossible.

“What,” McCarver asked Ralph Kiner with trademark incredulity, “is going on?” That had been the sentiment surrounding the Mets for nearly three months of a season gone awry. Tim thought about it some more and declared that for the dugout-sheltered players watching another team — “the wet brigade” — struggle, “this is the most fun the Mets have had all year!” By the time the crew, supplemented by additional stadium personnel, hit its mark and covered the entire infield, the rain had come to a full stop. Even Eddie Murray paused from his two-year commitment to taciturnity and broke into a grin.

Fun somehow became the watchword of that Tuesday night, provided the 21-52 Mets hadn’t sucked the good humor out of you and you didn’t mind staying up late. The tarp was eventually taken off the field (no crewmen were lost) and the Mets managed a 10-9 win. “Managed,” as in after the delay of 88 minutes, the Mets broke a 1-1 tie in the fourth; built a 6-1 lead in the top of the seventh; gave it back when the Marlins scored seven runs in the bottom of the seventh; grabbed the lead anew on three runs in the eighth; saw the Marlins even it up in the bottom of the ninth; and finally go ahead for good in the twelfth. Time of game: 4:20. Time when game ended: closing in on 1:30 AM. Saves blown by Mets: two — one by Pete Schourek, another by John Franco. Homers hit by Mets: four — one apiece by Murray, Jeff Kent, Todd Hundley and, before the rains came, Jeromy Burnitz, the rookie’s first as a major leaguer. Not only did the Mets win this game, it kicked off their first winning streak since the middle of April. It was a two-game winning streak in the middle of April and a two-game winning streak at the end of June, but when you’re bracketing a stretch of 15-48, you don’t have to be Crash Davis to know you don’t [bleep] with a winning streak.

In the midst of the madness of June 29, specifically in that seven-run seventh that gave the Marlins an 8-6 lead, Chuck Carr singled home Greg Briley to cut the Mets’ edge to 6-2. Carr had to leave the game after straining a rib cage. That meant by the time Dave Telgheder came out of the Mets bullpen to pitch the tenth, eleventh and twelfth, Carr was not playing. I mention this because either the morning after this game or maybe the morning after the game that followed, Telgheder was a guest on WFAN. I was definitely interested in hearing what he had to say. Dave had been up for a couple of weeks at that point. He’d started one of those Monday Met wins and earned the W. He finished the Tarp Game and rose to 2-0. As far as I was concerned, Dave Telgheder at 2-0 was the 1993 equivalent of Ken MacKenzie.

I remember exactly one thing Dave Telgheder said to whoever was interviewing him. I remember the gist of it, at any rate. The conversation was upbeat, befitting the veritable coming out party for a rookie pitcher who was succeeding when most about him were doing the opposite. I don’t remember who was asking the questions, but I don’t think it was much more of an interrogation than “what did you like best about getting that win in that crazy game?”

According to my memory, Telgheder said something that included his delight at the Mets getting to “shut up little Chuckie Carr.” Dave laughed when he said it, but devilishly. For a more modern reference point, maybe you recall John Buck assuming pie duties from Justin Turner one postgame when Jordany Valdespin was being interviewed about his walkoff heroics in 2013. It wasn’t a gentle “yay, we won!” whipped cream smush in JV1’s face. It was “this is an excellent excuse to hit you who irritate your teammates hard in front of everybody and make it look celebratory.” As I try to reconstruct Telgheder’s tone and words in my head, that’s what it sounds like. Dave, who came up through the Met system, was kidding about Chuck, who came up through the Met system, so maybe it was all good-natured. Or, to borrow a phrase introduced by Al Franken about ten years later, maybe he was “kidding on the square”: kidding…but not kidding.

As I took this all in (which was better than taking in the pennant chances for a team almost 30 games out of first place before the season’s halfway through), I wondered what, exactly, was so bad about Chuck Carr? Was he notably yappy when he was on the Mets? He’d been here for so brief a time, that I can’t swear I’d formed a strong impression. In that way that I was absent from typing class the week we were taught how to type numbers without looking at the keyboard — and therefore I still have to look at the keyboard when I want to type numbers — I wasn’t intently watching the Mets the week Chuck Carr first joined the team. It was the last week of April 1990. I was in the process of moving into my first apartment and flying to Tampa for my fiancée’s college graduation, after which my first apartment would become our first apartment. Big doings in two people’s lives. Three if you count what Chuck Carr was up to.

The 1990 Mets didn’t roar to the sort of start traditionally expected of them. Keith Miller, one of the better utilitymen the franchise has ever employed, emerged out of lockout-shortened Spring Training as the starting center fielder. Notice I didn’t refer to Keith Miller as one of the better starting center fielders the Mets have ever employed. Keith was a stopgap. Then Keith was injured. The Mets weren’t loaded with center field depth. To fortify their ranks, they had to reach down to Double-A Jackson and promote by two levels speedster Chuck Carr. I read New York Mets Inside Pitch and listened to the Farm Report on Mets Extra enough to know Chuck Carr was a speedster. Carr stole 62 bases in 1988 when he was a Mariner minor leaguer, 47 more in 1989 once the Mets got him. If the Mets had a speedster running wild in their system, word rose to New York before the player with the fast feet did. We didn’t have that many speedsters. In the ’80s we’d had Mookie Wilson and Lenny Dykstra. This was the ’90s. They were gone.

Davey Johnson, still managing the Mets in the new decade, shed about as much light as possible on the coming of Carr: “My needs now are somebody who can pinch-run, play some defense. My center fielder [Miller] has a tight hammy, and we needed another outfielder. How much Carr plays or how long he’s here is uncertain at this point.”

Not quite a heralding befitting a prime prospect. Davey was just trying to keep together what turned out to be his last Mets team. Carr played one game for Johnson, a loss on April 28, before returning to Jackson. Center field at Shea would find its groove in short order, with Daryl Boston coming over from the White Sox to platoon with perennial fourth outfielder Mark Carreon, usually a corner man. By the time their skills meshed to create one steady center fielder within a potent lineup, the Davey Johnson era had morphed into Buddy Harrelson’s managerial tenure. Somewhere to the south of New York City, mostly at Jackson and a little at Tidewater, Chuck Carr continued to run. He stole 54 minor league bases to go with one that he nabbed during a swift August jaunt to Queens.

Chuck Carr, living his Met life. In 1991, the Mets decided a single speedy center fielder was exactly what they needed to start the season. Except it wasn’t Chuck Carr. It was Vince Coleman, signed to a four-year deal that isn’t primarily recalled for how it blocked the path of Chuck Carr, but it did that, too, one supposes. Carr was up and down with the Mets the year they stopped altogether contending. The game in which he was granted his first big league start, August 28, was also the game in which he notched his first career RBI (off T#m Gl@v!ne, no less) and the game in which he injured himself in the field while misjudging a fly ball. There’d be one more appearance about a month later. The Buddy Harrelson era was about to end. So, in Met terms, was the Chuck Carr era, such as it was. The Mets swapped him and the 28 bases he stole between Norfolk and New York in 76 games that summer to St. Louis for a Single-A reliever. Across three seasons, Carr stole 128 bases for Mets affiliates and two for the Mets.

Artificially turfed Busch Stadium had been traditionally friendlier terrain for outfielders whose game was defined by their speed. The brief glimpse the Cardinals gave Carr in September 1992 generated Chuck’s kind of results: 22 games, 10 steals — plus a two-run double off Jeff Innis in one of Carr’s first games back in the majors, his way of invoking Simple Minds. Don’t you forget about Chuckie. The franchise coalescing in Florida took note. The Cardinals exposed Carr in the expansion draft. The Marlins took him with their seventh pick. He was about to be an Original Fish.

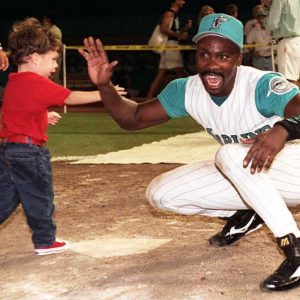

Within two weeks of the birth of the Marlins, Chuck Carr established himself as every day center fielder and leadoff hitter. By the time the Mets showed up at Joe Robbie for the Tarp Game, Carr was proving the skills he’d hone in the minors could play in the majors. He had 28 steals, en route to an NL-leading 58. A member of a first-year club leading his league in something was something else. As towering as Frank Thomas’s 34 home runs soar in the annals of the 1962 Mets, they placed him only sixth in the National League.

From the perspective of nearly thirty years on, the NL’s Top Ten Stolen Base Leaders of 1993 grabs a Mets fan’s attention. Gregg Jefferies, who wasn’t known for a bag thievery in New York, placed fourth with 46 sacks swiped. Eric Young, Sr., finished seventh with 42 for Colorado (his namesake son would lead the league in that category as a half-season Rockie/half-season Met two decades later). Brett Butler, two years before the Mets would sign him four years too late, totaled 39 stolen bases for the Dodgers, good for ninth in the circuit. Dykstra, as part of his MVP runner-up portfolio for the pennant-winning Phillies, absconded with 37, tenth among NLers. And that guy the Mets thought would be their speedster supreme, Vince Coleman, stole 38 bases, or ninth-best sum in the league. Vince might have swiped more had his Met career not come to an inglorious end in late July after he staged his very own Fireworks Night in the Dodger Stadium parking lot.

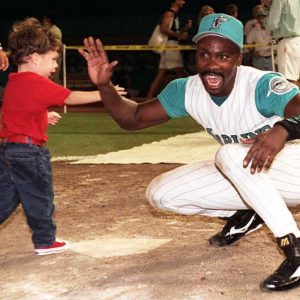

Chuck Carr outstole them all. His 58 bases were as many as any Met had ever stolen to that point, matching Mookie’s total from 1982. Chuck was also the most thrown-out base stealer of 1993, caught 22 times. He didn’t walk much for a leadoff hitter, and his OPS, when measured by contemporary standards, doesn’t amount to numbers associated with a spectacularly effective offensive player. But this was 1993. It wasn’t so far removed from the ’70s and ’80s that a base stealer who played fairly spectacular center field defense couldn’t be appreciated on his own terms. Marlins fans (they existed before they didn’t) appreciated Carr plenty. Far from wishing someone “shut up little Chuckie Carr,” they voted the kid from Southern California their Most Popular Marlin after the club’s first year of existence. He rewarded their support by stealing another 32 bases in strike-truncated 1994 while leading the league in singles and continually flashing his trademark smile. Chuckie may have been derided by some peers for the perceived crimes of excessive chatter and personal aggrandizement, but the folks who gave their hearts to the game (and slid their dollars across the ticket window counter) at a juncture when the game was on the verge of walking out on them noticed when a player gave his heart right back to it and them. Chuck Carr didn’t scowl his way to 90 stolen bases over the course of his two best seasons. The Memories section of Carr’s Ultimate Mets Database page confirms that if a person outside the baseball industry crossed paths with Chuck Carr, they were highly likely to identify as a Chuck Carr fan.

Chuck Carr, enjoying life after the Mets. Against Dave Telgheder’s recommendation, I maintained a slight fondness for Chuck Carr even as his Met affiliation faded from view. We know how Old Friends can be in their wrath toward the team that gave up on them, and indeed, Chuck Carr drove in more runs against the Mets than he did any opponent in a major league run that lasted through 1997. Then again, driving in runs wasn’t exactly Carr’s specialty, so I don’t think it did any harm to give Chuck a light hand when he’d be announced as part of the Marlin starting lineup at Shea. I’ve always tried to acknowledge the prodigal sons when they’re in for a visit, at least until their post-Met success erodes my lingering goodwill.

After Carr left the Marlins, I stopped keeping up with his doings. I didn’t realize, until I read his obituaries, how much injuries depleted his primary skill set as the ’90s wore on. I didn’t know that he pretty much talked himself out of Milwaukee in 1997, albeit in the stuff of an anecdote Ron Shelton has to wish he’d written. It seems Carr swung on two-and-oh against manager’s orders and popped up. When confronted, Carr reasoned, “That ain’t Chuckie’s game. Chuckie hacks on two-and-oh.” Chuckie also packs for his next stop after such an explanation. The good news for Carr was his next stop was playoff-bound Houston, for whom he would hit his only postseason homer, off John Smoltz in the ’97 NLDS.

Then, while I was too busy focusing on the late ’90s/early ’00s Mets to notice, Chuck Carr was out of Major League Baseball. But not out of baseball. Carr’s smile in games and toward fans was genuine. He loved the sport enough to keep working at it wherever he could. He went to China and played on the Mercuries Tigers with future Met Melvin Mora (thus making them Mercuries Mets). He played in the Atlantic League when independent ball in the Northeast was a fresh concept. One of his two indy seasons was as a Long Island Duck, reuniting with Harrelson as Buddy was getting his quackers off the ground. Chuck then took his talents to Italy and then finished up in the Arizona-Mexico League, a 35-year-old player-coach ten years removed from his stolen base crown. Had Chuck Carr’s career crested later, in this day and age, he might have been hailed on social media for his “swag”. Or his flair/bravado might have rubbed some teammates and opponents the wrong way anyway because big league baseball still has more John Buck than Jordany Valdespin at its stodgy core. Or as someone who could run a lot but not hit nearly as much, he might not have been handed more than a cup of coffee — to go.

But if Chuck Carr was the person he was all along, he probably would have kept on talking and kept on smiling and there’d have been a reason to keep on applauding. It’s never too late for a baseball fan to put two hands together for a baseball player who let you know how much he loved the game.

by Greg Prince on 19 November 2022 5:47 pm Those wisps of smoke visible in the autumn sky remind us that this has been a busy birthday week amid the lofty heights of the Mets’ Mount Pitchmore, with Dwight Gooden turning 58 on November 16 and the 78th anniversary of Tom Seaver being born having come around on November 17. Next date to celebrate, commemorate and blow out candles up on that mountaintop: December 23, Jerry Koosman’s 80th birthday.

What each of these three icons of taking the ball; throwing it; and succeeding lavishly have in common, beyond their place atop the topography of Mets hurling, is they started their major league careers as Mets…yet didn’t finish it that way.

You don’t have to be the fourth face on the Mets’ Mount Pitchmore to claim common ground with Seaver, Gooden and Koosman on that count, but more on him in a while. A slightly lesser mountain populated by Met starters who started in the bigs as Mets — pick your pitchers — would say the same thing. Maybe your name is Matlack. Or Swan. Or Darling. Or Jones. Or, of more recent vintage, Harvey or Wheeler or Syndergaard or Matz. Your MLB debut (even if you were first signed professionally elsewhere) came as a New York Met. You would eventually make plenty of pitches as a Met. But you wouldn’t make all of them.

When David Wright stepped aside at the end of a long if not long enough career as nothing but a New York Met, we practically fainted from lack of precedent. With the exceptions of Ed Kranepool and Ron Hodges, nobody who’d lasted double-digit years in the majors did so exclusively as a Met. When we mourned the too-soon passings of Pedro Feliciano and Jeff Innis, we noted they were relievers who provided all the relief they could for the Mets and only the Mets. Feliciano in particular captured our imagination for flitting in and out of other organizations but not wearing their uniform in official action, especially when he took the Steinbrenners’ money for two years and used his time in their employ to rehab rather than pitch for them. True to the orange and blue, indeed.

But starting pitchers, the signature actors on the Met stage, have been a different story. There have been no high- or mid-profile exceptions to the Everybody Leaves Home Eventually rule. While we toast the memory of Tom Terrific every November 17 (every day, really), we try to forget that 38.949 percent of Seaver’s starts came as something other than a Met. The percentages we prefer to remember are 98.84, his Hall of Fame vote; .781, his W-L pct. in his first Cy Young season from going 25-7 in 1969; and 61.051, or the inverse of 38.949. Tom made more than six of every ten of his starts as a Met. William DeVaughn advises cleansing the Seaverean section of your mind of Reds and White Sox and Red Sox imagery and just being thankful for what you got. We got a lot of Tom Seaver.

Not all of him, though. Never all of it with our most substantial starting pitchers. Doc Gooden the no-hitter crafter for the Yankees. Jerry Koosman the 20-game winner for the Twinkies. Jon Matlack placed second in league ERA in 1978 as a Texas Ranger. Ron Darling went to the playoffs in 1992 as an Oakland A. We’ve already hit of late on the sore-ish subjects of Zack Wheeler and Noah Syndergaard. But we could go way back, too. Before Seaver was traded to Cincinnati, Jim McAndrew pitched for San Diego, Gary Gentry pitched for Atlanta and Nolan Ryan pitched for California. Some of the moves that led to those reassignments were better than others for the Mets — the trade of Gentry begat Felix Millan; the trade of Ryan begat Jim Fregosi (plus a half-century of Ryan-related regret) — but within the context of a Met starter starting, continuing and finishing a career as a Met, the outcome was essentially the same.

Anybody of note come notably close to being a Met and nothing but a Met? A few. McAndrew, for example, started 110 games as a major leaguer, 105 of them for the Mets. That’s better than 95 percent made for the Mets. Yet those five times he took the hill as a Padre starter spilled an infinitesimal if indelible brown and yellow blot on Jim’s Metsian purity. A little short of a hundred miles up Interstate 5 from San Diego, another Met starting pitcher of considerable tenure drove off the road of his journey to keeping it 100. Craig Swan started 184 games as a Met between 1973 and 1983. In 1984, the onetime National League earned run average champion was languishing in the Met bullpen. The club released him in May. Swan was 33. Two entities decided he still had competitive pitches embedded in his right arm: Swan and the California Angels. Thus, Craig went to Anaheim, gave extending his career a shot with one more start (and one more relief appearance) before finding himself off MLB mounds once and for all.

One-hundred eighty-five career starts in all. One-hundred eighty-four career starts as a Met. That’s 99.459 percent for us. So, so close. Swannie, you coulda been practically the pitching version of Ed Kranepool. Alas, that probably wasn’t your goal as summer approached in ’84.

How about a loophole? Jason Isringhausen came up to the majors with the Mets, made 52 starts between 1995 and 1999 with the Mets in that period and never made a start for anybody else. Eureka? Fool’s gold. Izzy never threw the first pitch of a game for the A’s, Cardinals, Rays or Angels, but he surely threw pitches at other junctures of loads of games for them. Jason appeared in 724 major league games. In 611, he was something other than a Met, usually as one of the leading closers of his day. The most accomplished of the Generation K trio posted 300 saves overall. His first, in ’99, and final seven, in Recidivist 2011, were for the Mets. The rest were for the A’s and Cardinals.

Verdict: not much of a loophole.

Let’s take a deeper look at this phenomenon through the prism of the first 60 years of New York Mets baseball. Here’s every Met pitcher who a) started his major league career as a Met; b) started at least 50 games for the Mets; and c) didn’t pitch for the Mets in their 61st year.

MOST GAMES STARTED AS A MET BY PITCHERS

WHOSE MLB CAREER STARTED WITH METS

(% of career starts as a Met; excludes 2022 Mets)

Tom Seaver 395 (61.051%)

Jerry Koosman 346 (65.655%)

Dwight Gooden 303 (73.902%)

Ron Darling 241 (66.209%)

Jon Matlack 199 (62.579%)

Bobby Jones 190 (78.838%)

Craig Swan 184 (99.459%)

Jon Niese 179 (90.863%)

Mike Pelfrey 149 (58.203%)

Zack Wheeler 126 (64.615%)

Gary Gentry 121 (87.681%)

Noah Syndergaard 120 (83.333%)

Dillon Gee 110 (85.938%)

Steven Matz 107 (73.288%)

Jim McAndrew 105 (95.455%)

Matt Harvey 104 (57.777%)

Ed Lynch 98 (82.353%)

Nolan Ryan 74 (9.573%…with 295 wins elsewhere)

Nino Espinosa 67 (53.175%)

Jae Seo 66 (64.706%)

Mike Scott 60 (18.809%)

Rick Aguilera 59 (66.292%…and 311 saves elsewhere)

Masato Yoshii 58 (49.153%)

Walt Terrell 56 (19.048%)

Jason Isringhausen 52 (100%…but 292 saves elsewhere)

In case you’re wondering, Sid Fernandez’s big league career had a John Stearns-style start to it. Stearns made one appearance in a Phillies uniform, on September 22, 1974, before his trade to the Mets the following December. El Sid was an L.A. Dodger for two games at the tail end of 1983 — first as a reliever, next as a starter — prior to Frank Cashen gladly taking Fernandez off Tommy Lasorda’s hands. Sid proceeded to make 250 starts for the Mets between 1984 and 1993, fourth-most by anybody in Mets history. Unlike Stearns, who never played for anybody else beyond his Met years, Fernandez logged innings (including 49 starts to bring him to 300 in all) for three other teams from 1994 to 1997. And in case you’re really wondering, Sid Fernandez and John Stearns shared a Met starting lineup exactly once, on September 26, 1984; John was the first baseman that Wednesday night at Shea, as Sid notched a 7-1 win over Jerry Koosman and the Phillies in the season’s final home game.

If you were wondering any of that, I truly value the cut of your jib.

ANYWAY…that’s 25 pitchers who made at least 50 starts as a Met from the beginning of a major league career and none of them spending an entire major league career as a Met through 2022. That tells us how hard it is to hang on to a starting pitcher and how effective the pitchers who became icons for us were, given that they had to establish their iconography in something less than the span of an entire career.

But what about starting pitchers who began their careers as Mets, made at least 50 starts as Mets, and happened to be Mets in 2022? They’ve been left out of the above accounting because there is a TBD nature to their careers. Also “they” are exactly one Mets starting pitcher. Maybe you’ve caught on to where this is going, beyond the chance to acknowledge the birthdays of Dwight Gooden and Tom Seaver.

To be determined, indeed, is the nature of Jacob deGrom’s career, specifically where it will continue in 2023. Free agent Jake is already one-quarter of the Mets’ Mount Pitchmore. If we’d included deGrom’s 209 starts in the list above, he’d rank between Darling and Matlack, but (with no disrespect to Ron and Jon) his peers sit at the top of the chart. Seaver. DeGrom. Gooden. Koosman. Shuffle the second, third and fourth names as you like, but they belong in a row. Jake’s got nine seasons in the books, all of them as a Met. In every one of those seasons, he has never been less than one of the two most significant pitchers in the Met rotation, and usually he hasn’t had even that much company.

In the context of the list above, he not only blew past the likes of Jon Niese and Dillon Gee practically upon arrival, he outlasted contemporaries Matt Harvey, Zack Wheeler, Noah Syndergaard and Steven Matz. Those four plus deGrom shaped up as the core of a pitching staff that was going to grow into full maturity together. As individuals, each of the other four had his extended Met moment prior to a departure that appears inevitable in retrospect. DeGrom’s Met life, meanwhile, self-renewed without a ton of fuss — only a torrent of success. Except for not remaining unfailingly, unquestionably in what we refer to as one piece, Jacob deGrom has done nothing to make a Mets fan wish he won’t be celebrating his 35th birthday in a Mets uniform on June 19.

Of course Jake hasn’t remained unfailingly, unquestionably in one piece in his eighth and ninth seasons in the bigs and, as more than implied a sentence ago, he will turn 35 this coming June. If you want to pick apart the case for never letting him leave, beyond a need to count Steve Cohen’s money or calculate luxury tax impact on the construction of the rest of the roster, there were a couple of walls he hit in some of his September starts and there were a couple of starts where his core competency of being absolutely untouchable wasn’t in evidence inning after inning. A slightly diluted deGrom was still a sensational bet in Rob Manfred’s gambling-obsessed enterprise. Jake notched the first postseason victory by a Mets starter in seven years, and you wouldn’t wager against him notching the next one fairly soon if given the chance to lead the Mets toward another, hopefully deeper October run.

Mount Pitchmore is so named because its occupants are the pitchers good sense told you should pitch more for the Mets. In a given inning. In a given game. In a given series. In a given career. Seaver, Koosman and Gooden weren’t given the opportunity to keep it 100. Maybe in a given moment it didn’t seem off to have them out of the contemporary picture. Yet you look back and you wish you could see each as only a Met. DeGrom still has 100 in play. Began as a Met. Excelled as a Met. Can still go on as a Met and finish as a Met and nothing else. That would be 100% my preference.

If I have to eventually understand that progress moves the Mets and Jacob in different directions, I will pivot as events dictate. I acknowledge the risk/reward ratio of re-signing deGrom entering 2023 looks different than it did heading into 2019. Nevertheless, my choice is to view at least one quarter of the Mets’ Mount Pitchmore is something other than historical perspective. I’d like to watch Jacob deGrom pitch in a New York Mets uniform for all his baseball years to come. And when he’s done, I’d like to see his name ensconced atop the list of most starts by a pitcher who began his MLB career as a Met and never pitched for another MLB team.

Do you know who’s atop that specific list right now? Well, Jake, obviously, but that’s with the TBD caveat. Not only is deGrom first with 209 starts, David Peterson is second with 43 and Seth Lugo — only sometimes a starter (other than in his heart, perhaps) — is third with 38. Peterson’s been on our scene barely three seasons and Lugo is actively shopping his services around the industry. Tylor Megill, a rookie in 2021, is already sixth on this list with 27 starts. You can see the inherent folly of referring to players just getting going or going through free agency as Lifetime Mets.

If we limit eligibility to Met starting pitchers who we know for certain never pitched and never will pitch for another Major League team, the list sits at the foot of Mount Pitchmore. If we remove 2022 Mets from consideration, we can’t use a baseline of 50 starts as a Met. Or 40 starts as a Met. To get a list with enough names to make the exercise worthwhile, let’s set our minimum as a mere 5 starts. That’s pitchers who started their MLB careers as Mets, made at least FIVE STARTS and never pitched for anyone else in the bigs. You wouldn’t think we’re asking for a lot. All we’re going for is the amount equivalent to the quantity of fingers on one standard-issue human hand.

Let’s count upward this time.

BOB MYRICK (5 starts): A reasonably effective lefty reliever from 1976 to 1978. Got his starts for teams going nowhere. Bob’s starting career went the same place. Two of his starts were second games of doubleheaders, usually a tipoff that the manager simply needed someone to eat a few innings. Myrick also got the in-season starting assignment that in most years was the hallmark of a pitcher the manager didn’t have many other starting plans for: the Mayor’s Trophy Game, in 1977 (it doesn’t count toward Bob’s total). Was traded to Texas in 1979 with somebody to be mentioned several slots ahead on this list. Like his trade companion, Bob never made it back to the majors after being a Met.

BRENT GAFF (5 starts): The Mets had lost four in a row and really could have used a boost from their minor league callup on July 7, 1982. They got one for seven innings from Brent, who kept the Giants off the board…until the eighth. He wound up losing, 3-2, in his debut (and the Mets’ losing streak would reach seven), but a potential starter was born. “He really showed me something pitching out of that bases-loaded situation in the seventh,” George Bamberger said. “I wanted him to win real bad. I was heartbroken when he didn’t.” Bambi’s heart mended enough to give Gaff four more starts in ’82. Brent merged anew as a valuable reliever for Davey Johnson in 1984, prior to injury curtailing his career.

CHRIS SCHWINDEN (6 starts): Less remembered for his half-dozen uninspiring starts early in the Terry Collins era — the final results of which were 6-5 losses three times and 10-1, 18-9 and 8-1 losses the other three times— than for his coming through the waiver process with his right arm somehow intact. After what proved to be his final big league appearance in 2012, Chris was waived by the Mets and picked up by the Blue Jays; waived by the Blue Jays and picked up by the Indians; waived by the Indians and picked up by the Yankees; and waived by the Yankees and picked up by…the Mets…all in a span of less than five weeks. Last pitched professionally for the Lancaster Barnstormers of the Atlantic League in 2014; started 25 games and won 14 of them.

BOB MOORHEAD (7 starts): The first Met to make his major league debut as a Met, in the very first game the Mets ever played, too. Bob might have been the canary in the 1962 Mets’ coal mine. In April, he made six appearances in relief; the Mets lost them all. From May 6 through June 9, he pitched in nine games, starting and relieving; the Mets went 5-4. Prosperity took a holiday thereafter, with the Mets posting a record of 1-22 when Moorhead took the mound in any capacity. Bob wouldn’t pitch for the Mets again until 1965: nine relief appearance in nine losses. One hopes he didn’t believe the Mets’ lack of success reflected upon him personally. Most every Met was kind of a bad-luck charm in those days.

ALAY SOLER (8 starts): A lifesaver, or at least a holeplugger, for a spell in 2006. The first-place Mets weren’t exactly drowning, yet they never seemed to have enough reliable starting pitching. They turned to Alay, a Cuban defector whose MLB debut came at age 26, and he threw a couple of early-June gems, most notably a two-hit shutout at Arizona in the midst of the 9-1 road trip that all but clinched the division title. Soler’s effectiveness wore off, Willie Randolph found other options, and the righty fell out of the Mets’ plans before the Fourth of July.

BOB APODACA (11 starts): The reliever who wore the fireman’s helmet between the trade of Tug McGraw and the acquisition of Skip Lockwood — leading the 1975 Mets in saves with 13 — Bob was given handfuls of starts in 1974 and 1976. That would happen with relievers back then. His first came in a contingency role when Matlack was ailing. Yogi Berra handed Dack the ball and Dack handed him five innings of two-run ball and a win over Bob Gibson and the Cardinals. Ultimately, Apodaca’s role would be to sit on the DL for a very long time following ligament damage to his right elbow in a Spring Training game in 1978. He never pitched in the majors again, but sure did a lot of coaching there, including for Bobby Valentine’s renaissance Mets of the late ’90s.

SCOTT HOLMAN (14 starts): Every generation has that Triple-A comer a fan is convinced is gonna come up and be the answer, based on nothing but a vague sense generated by staring at his name in the back of the yearbook or The Sporting News’s Tidewater stats. My guy was Scott Holman. Just wait until Scott Holman gets here, I told myself in the early 1980s. Three quality starts after the rosters expanded in 1982 made me look like a visionary. By the summer of ’83, things grew a little blurry, as Scott receded from rotation to relief. His last MLB appearance came on September 29, 1983. Great days awaited the Mets. Holman would spend them in the minors, striving to get back for a taste.

COREY OSWALT (14 starts): Corey Oswalt called and said he doesn’t belong on this list, that after a dozen Met starts in 2018 and one apiece in 2020 and 2021, he’s still very much active, pointing to his presence with three different organizations in 2022 as proof, that for all I know he’s gonna have another start in the majors. I reluctantly responded that his Triple-A stints in Sacramento (the Giants), Lehigh Valley (the Phillies) and Albuquerque (the Rockies) — and the combined 6.57 ERA he posted at those stops — may not be the compelling evidence he believes it to be. Corey is currently a free agent. He’s welcome to pitch for another major league team and hop off this list ASAP. Until then, he’s sticking around next to Scott Holman. Should Oswalt get another chance at the major league level, may he enjoy the run support he received the day he notched his second MLB win, in the first game of the doubleheader of August 16, 2018. Final score at Citizens Bank Park: Mets 24 Phillies 4; it was the most runs the Mets have ever tallied in one game. The record will show Oswalt protected an eleven-run lead in the fifth inning to secure his victory.

JENRRY MEJIA (18 starts): An alternately promising and injured righty whose starts were scattered within four seasons of mostly relieving. Some of his stints were positively mouthwatering. The afternoon half of a day-nighter in Washington in 2013 stands out in memory: seven innings, zero runs, an 11-0 late-July whitewashing that elevated the Mets to 22 wins in their previous 36 games, or the high point of that otherwise godforsaken season. Jenrry found his groove as the Met closer in 2014, nailing down 28 saves for a team finally on the upswing. Then there was something about PEDs and that was basically that for Mejia.