The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 26 September 2022 2:59 pm Those graphing skills you may have retained from geometry class will finally come in handy if you are yearning to illustrate the upward trajectory of the Mets’ single-season runs batted in record.

1962: 94 — Frank Thomas

1970: 97 — Donn Clendenon

1975: 105 — Rusty Staub; tied by Gary Carter in 1986

1990: 108 — Darryl Strawberry

1991: 117 — Howard Johnson; tied by Bernard Gilkey in 1996

1999: 124 — Mike Piazza; tied by David Wright in 2008

Each of those totals loomed as singularly impressive until somebody surpassed it (even if somebody matched it). They’re still impressive in and of themselves. Whatever limitations the run batted in might encompass as an indicator of overall offensive production, we still know a high number of runs batted in when we see it. We intrinsically understand that a number must be pretty high if nobody comes along and posts a higher one for quite a while despite every batter’s literal best-case scenario — and therefore every batter’s deep-seated goal when he comes to the plate (even those just trying to get on base) — being that a run scores as a direct result of what he does while batting.

We never in the course of a game think, “I wish our team hadn’t just scored another run.” Everybody who isn’t the opposing pitcher or among those invested in that opposing pitcher’s team’s cause is thrilled to see a run batted in. Advanced though modern statistics may be, the RBI perseveres as aspirational in every game, good or bad, in every season, good or bad. Geez, Thomas’s 94 RBIs on the 1962 Mets are more than twice as many games as the outfit for whom he was driving them in won. A supercut of Frank’s at-bats could have constituted a pretty complete team highlight film in living black and white.

Thomas held the Met RBI record for eight years, Clendenon for five, Rusty for fifteen (four shared with Carter), Straw for one, and Hojo for eight (three shared with Gilkey) until Mike put it out of reach of all but one Met (David) for the next 23 years. It had been ages since somebody smashed or pulled up alongside the Mets runs batted in barrier.

But now we and the Mets Record Book are living in the Age of Alonso, and in the Age of Alonso, we’re gonna need a taller sheet of graph paper.

The most urgent takeaway from Sunday in Oakland was the 13-4 thumping the Mets laid on the A’s. Unless we’re overthinking draft order, we never wish our team hadn’t just won another game. This isn’t a year for draft order thinking. This is a year when every win matters and, as Monty Python might suggest, every run is sacred. There was no saving any of it for tomorrow, currently today. Today’s an off day anyway.

Sunday was largely taken care of in the bottom of every inning Max Scherzer pitched (the first six, with one run allowed) but destined to be defined in the top of the fourth. The Mets already led, 3-0, thanks to a rare RBI from Tyler Naquin and two increasingly common ribbies from Eduardo Escobar. It represented a promising start, but the Mets weren’t finished. They couldn’t be. The Mets led Saturday, 3-0. It didn’t keep. Sunday they added on, first via Francisco Lindor doubling with two runners on (no mean RBI machine himself, Francisco the shortstop’s season sum stands at 103), then Pete Alonso homering with Lindor on second. That gave Pete 125 RBIs, or the most runs any Met had ever driven in within the confines of a single season. More than Piazza in ’99 and Wright in ’08. More than the standard that had stood for so long that a person suspected it was forever unbreakable.

But not as many as Alonso would have by the end of Sunday, specifically after the three-run double he lashed into the right field corner in the eighth turned an 8-1 laugher into an 11-1 howler. Pete Alonso now held a brand new Mets single-season runs batted in record of 128. Chances are that record will rise more than once between tomorrow night and the end of business on October 5.

There is no such thing as too many runs, regardless of lead, regardless of opponent. The Mariners’ 11-2 lead at Kansas City on Sunday became the Royals’ 13-12 victory. The Mets lead the National League East by 1½ games. Alonso leads the NL RBI race by 16. I had to look up the latter standings. I’m not sure I realized Pete was still ahead of all National League batters — Paul Goldschmidt is a distant second — in what has become his signature category in 2022. I don’t spend a waking moment not cognizant of where the Mets stand relative to the Braves. The Mets are barely ahead of Atlanta after 154 games on the shoulders of at least a couple of dozen fellas making the most out of their orange-and-blue opportunities. The strongest of those shoulders belong to the regular first baseman, intermittent DH and tolerable pitchman (he’s more convincing anticipating a delivery of pancakes than he is sneaking up on Nathan in the front seat) we call the Polar Bear and we call when we need a run batted in.

Over the next eight games, we will be pulling hard for the Mets to pull away from the Braves. That’s the prize that counts most, at least until after October 5. Pete putting further distance between himself and everybody else who drives in National League runners for a living, not to mention anybody who ever drove in Met runners before, will amount to a powerful bonus.

by Greg Prince on 25 September 2022 3:44 am “Gary Apple back in our New York studio, following the Worst Game Ever, as the Mets lose, 10-4, to the Oakland Athletics, though mentioning just the score and the opponent doesn’t do it justice, does it, Todd Zeile?”

“No, the score only hints at the awfulness of the entire sorry episode, Gary. That’s why I have to give everybody in this game and everything about this game my Zeile of Disapproval. My Zeile of Dismay and Zeile of Disdain, too.”

“It’s harsh, but merited. We’re going to go live now to the visitors’ clubhouse at Ring Central Coliseum in Oakland to Steve Gelbs. Steve, you weren’t even scheduled to be on the West Coast today, but instead of preparing to host our Jets pre- and postgame shows tomorrow, you flew out for this.”

“That’s right, Gary. For this historic occasion, SNY spared no expense, and we have live coverage of the celebration.”

“On the monitor, it’s clear the tenor of this celebration has a different tenor than the one the Mets participated in last Monday after clinching a spot in the upcoming postseason. That was more of a muted affair, whereas I see the champagne is flowing after this Worst Game Ever.”

“That’s right, Gary. The champagne is, of course, flat and off-brand, much like the effort it is celebrating.”

“And the t-shirts we see the players wearing, the ones that read ‘THE WORST’?”

“Irregular and a bad fit.”

“Under the circumstances, that’s appropriate. I see you have a special guest, Steve.”

“Thank you, Gary. We are joined here in the visitors’ clubhouse by Mets president Sandy Alderson. Sandy, this has to be a special feeling for you.”

“It is, Steve. These are the two franchises with which I’m most associated, and finding myself watching the Worst Game Ever from the perspective of somebody who had a role in building the losing team after my history with the winning team, knowing that the losing team is actually a winning team most days, and that the winning team is a consistent losing team, gives me a particular sense of pride.”

“Sandy, you’ve been on the wrong end of a lot of losses for both the A’s and the Mets. You were the general manager when Kirk Gibson hit his legendary home run off Dennis Eckersley in the 1988 World Series, and Mets fans can name any number of stinging defeats from your two tenures in New York. What made this one the Worst Game Ever?”

“I think there were a certain number of variables present in this game that you simply don’t see every day. You had arguably the best pitcher in the sport, Jacob deGrom, appearing totally clueless. Jacob was followed by one reliever after another who couldn’t record outs before giving up runs. You had the Met defense breaking down at critical junctures. You had the dimensions of the ballpark here playing a role. You had the elements, at least one of them in the form of a bright midday sky, also making themselves felt. You had the Met offense coming to a dead halt after a while, with every ball it hit hard somehow finding a glove, and every potential rally snuffed, and this was against a team that analytics suggest is notoriously incapable defensively.”

“And you’re considered the godfather of ‘Moneyball’. Sandy, even with all of that going sideways, was there something else, something intangible that pushed this loss into the Worst Game Ever column?”

“Well, you can’t ignore the expectations. I think our fans, whether they were here or watching from home or wherever they were following, had this game listed as a win if not before it was played, then probably after Jacob was staked to an early three-nothing lead. There is a level of disbelief that can be reached, even in an industry where it’s not uncommon for a so-called lesser team to beat an ostensibly better team, where you’re convinced there’s no way something can go wrong. I think today we proved everything can go wrong.”

“The final from Philadelphia, where the Braves won and trimmed the Mets’ lead in the National League East to a game-and-a-half, would seem to underscore that assessment. Sandy, final question: you’re transitioning soon from your role as team president to that of special advisor to Steve and Alex Cohen and the Mets’ senior leadership. Can you give us an idea of the kind of advice you’ll be providing?”

“There’s a degree of discretion when you serve in an advisory role, and every situation needs to be treated as its own challenge, so I don’t know that there’s a one-size-fits-all answer to your question, but in broad terms, I would strongly advise not playing any more games like the one we saw today.”

“Thank you, Sandy. We now talk to somebody who had a big part to play in the Worst Game Ever. Darin Ruf, owner of a .427 OPS as a Met, what’s it like to receive LVP honors?”

“I didn’t see it coming.”

“That could describe most any ball hit in your direction in right field.”

“It was a team effort, Steve. I may have the hardware here…”

“Which I see just fell apart in your hands.”

“…but it wasn’t just me. Maybe I’ve just become the most visible reason for our team losing.”

“Least valuable, most visible?”

“None of us really could see the ball well or hold onto it for very long, and after the second inning, none of us could make anything happen when it came to getting us back in the game. I don’t want to take all the credit. Together, we were all Least Valuable. If it were up to me, I’d divide this award 28 ways and give a little bit to each guy here.”

“The award is not made very well, so you may have that opportunity. Darin, you haven’t been hitting much, you don’t run well and your experience in the field hasn’t been fruitful. How have you managed to put all that together for the Mets since coming over from the Giants for J.D. Davis and three minor leaguers?”

“Y’know, it’s funny. When I was across the Bay with San Francisco, I got to meet Willie Mays, and they say Willie wasn’t only the epitome of a five-tool player, but when you factored in his baseball intelligence, he was really a six-tool player. When he and I met, I realized that between the two of us, we had six tools.”

“Thank you, Darin. I’ll let you get back to the celebration with your teammates. Like you said, you were all a big part of what we saw today. Meanwhile, we have another couple of special guests in the clubhouse here, Sun and Space. Sun, you’ve been around practically forever, even longer than Albert Pujols has been hitting home runs. Darin Ruf just mentioned the great Willie Mays. Older baseball fans remember Willie’s last game in center for the Mets, right here in the Oakland Coliseum, and all the problems he had fighting you. Did today bring back any of those memories?”

“Oh, absolutely, Steve. I hope people who instantly invoke Willie’s difficulties that afternoon in 1973 as some kind of evidence that he shouldn’t have still been playing baseball at his age will realize that when I’m over the outfield in a day game here, especially when it’s fall, nobody, regardless of age, should be playing baseball.”

“You do make things difficult, Sun. As do you, Space. You had one of the most expansive days we’ve seen this year.”

“Great day, Steve. I don’t get the opportunity to inflict a whole lot of foul territory on too many teams anymore, but here in Oakland, I really get to roam, just like since the place opened in 1968.”

“True, few ballparks are built in this era with so much space for so many balls to fall in and for so many players to fall down like they have here, and the Mets, who are used to comparatively tiny slices of foul territory at Citi Field, definitely didn’t look comfortable dealing with what you had going today.”

“I’m wide open, Steve. It’s a great feeling.”

“Thanks, guys. We are now joined by two others who helped write the story of today’s game, Projection and Anticipation. Projection, you had everybody thinking that with Jacob deGrom on the mound and Pete Alonso having crushed a two-run homer after Francisco Lindor drove in his hundredth run on the season that there was absolutely no way the Mets could lose. And even after those four runs Jake gave up in the first, once Mark Vientos crushed his first big league homer, it had to seem there was no way the Mets could lose. But maybe you had different ideas?”

“Honestly, Steve, I had no idea. You gotta remember: I’m Projection. I just project what figures to be ahead, and I figured the Mets would stay ahead and be ahead, and it sure looked like it.”

“It’s the little things that make a bad game the Worst Game Ever. Anticipation, I think it’s fair to say you were really looking forward to this game, Jake on the hill against a last-place team and the playoffs on the horizon, almost too perfect a setup for a Saturday afternoon.”

“What can I say, Steve? I tend to look forward and look ahead. It’s what I do. Yet for all that looking ahead, sometimes I can’t see what’s coming.”

“A green and yellow freight train, apparently, in the form of the underestimated Oakland A’s, underestimated today at least, and a deGrom performance it’s safe to say nobody was anticipating. Jake lasted all of four innings and for the first time in more than three years gave up more than three runs. He just didn’t look sharp at all.”

“I didn’t see that coming.”

“One of your buddies at the end of the bench might have had a different idea. Come up here, Karma. Karma, you don’t always figure into the outcome of a given baseball game, but you seemed plenty invested in seeing the Mets lose the way they did today.”

“That’s right, Steve. I haven’t had the opportunity to contribute much lately, but I stayed loose, stayed ready and I saw I had an opening to make a difference, however slight, when I got word that somebody expressed a few unkind thoughts about Yogi Berra a couple of hours before first pitch.”

“Yogi of course managed the Mets in this very stadium in the 1973 World Series, where the Mets lost Games Six and Seven to a very talented Oakland A’s team, a Series some Mets fans to this day believe hinged on Yogi not starting George Stone in one of those games.”

“That’s correct. I went back a long way with Yogi. He may not have been the best manager in the world, but you’ll recall he was considered very lucky in his day, almost a human rabbit’s foot, and maybe it wasn’t the best idea to call out Yogi — I think the phrase was ‘shambling ignoramus’ — when the team you’re rooting for is in a pennant race and every game counts and you need all the help you can get. It’s something like those old margarine commercials where ‘it’s not nice to fool Mother Nature’ and suddenly there’s thunder and lightning.”

“In other words, bad Karma?”

“I’ve got access to a bulletin board and I’ve got a Ziploc bag full of thumb tacks if you know what I mean. Look, I don’t wanna take too much credit. Like Darin Ruf said, everybody in this room had something to do with today being the Worst Game Ever. But deGrom getting whacked around like that? McNeil slipping in left? All those problems the Mets had chasing foul balls? The A’s nabbing almost everything in sight? Let’s just say that even though Yogi’s been gone a while, he still has some friends among the higher-ups at Big Karma — and that his wife’s name was Carmen. Think about that, Steve.”

“We will, Karma, though maybe not until after we talk to our next guest. Angel Hernandez, we didn’t expect to find you in the losing clubhouse. To what do we and our viewers owe the pleasure?”

“Steve, I heard you were covering the aftermath of the Worst Game Ever, and you know the old expression: when something in baseball is considered the Worst, Angel Hernandez must be lurking somewhere.”

“Sure enough, you were the home plate umpire today, and it looked as if Jacob deGrom was a little unhappy with some of your calls.”

“Every pitcher is unhappy with my calls, Steve. Every batter is unhappy with my calls. Every manager is unhappy with my calls and, really, everybody is unhappy to see me. You’re probably not too happy seeing me standing here next to you.”

“I have to admit, Angel, it is taking all my self-control to not wretch in your mere presence. But I haven’t been myself since that sausage race in Milwaukee.”

“I saw that, Steve. I’d say that was the best, but I wouldn’t know anything about that.”

“I don’t suppose you would. Thank you, Angel Hernandez.”

“Funny, people only say that when I’m leaving.”

“We’re leaving, too. Back to you guys in the studio.”

by Jason Fry on 24 September 2022 1:56 pm To get us rolling, a sample of my strongly held opinions that make people either smile politely until I shut up or quietly back away from me when they think I’m not noticing:

- The American League is a jumped-up beer league, the National League should never have agreed to treat it as an equal, and John McGraw is a hero for standing against the tide and refusing to sully titles his team had already earned with an unnecessary exhibition against some upstart alien outfit.

- If February/March and October exhibitions against said beer league are accepted as a vaguely necessary evil, National League teams at least shouldn’t besmirch their regular-season schedules with further intrusions. Let alone swap league affiliations like poker chips when it suits someone.

- Yogi Berra‘s public persona as a cuddly gnome beloved by fans of baseball and language alike is a con that approaches Verbal Kint/Keyser Söze levels. Berra was a shambling ignoramus whose overthinking (not that he was a whiz at the regular variety) cost the Mets the ’73 World Series against the A’s. (Pointless exhibition games, perhaps, but you still ought to win them.) Berra also should never have been named Mets manager when Gil Hodges died. The job should have gone to Whitey Herzog, the architect of the ’69 Miracle Mets, and by making the wrong decision the Mets short-circuited what could have/should have been a dynasty.

- People paid to take part in guerrilla marketing for horror movies should be ejected from seats in which they’re a distraction for viewers watching at home, or at least they shouldn’t be spotlighted by regional sports networks whose trucks are full of people who take justifiable pride in being masters of their craft and so ought to know better.

(OK, that last one’s a new addition to my pantheon of grumpiness, and also probably not particularly controversial.)

This is an odd way of getting to my point, which is that the Mets playing the Oakland A’s will always feel strange. Friday night’s game was only the 24th against Oakland that counted — the first, played back in 2005, sent Greg back into childhood memories that weren’t particularly pleasant. (That post was also one of the early markers that our oddball blog would become something a little different than most baseball destinations, but that’s a whole nother post.)

Combine the West Coast with the American League and one’s first through fifth reactions to “Mets at A’s” will be something along the lines of, “Was this trip really necessary?” Particularly when said trip comes inexplicably in the season’s final sprint. A Mets-A’s evening tilt in May or June? I suppose, if we must. But when the rest of the schedule fits on a single easy-to-read SNY graphic, it’s bizarre. At least this weird part of the season comes sprinkled with off-days, which every team could use at this point and a team with its collective pedal on the floor trying to stay ahead of a relentless pursuer could use even more.

Ah, about that relentless pursuer. I was busy and didn’t get to catch up on what was happening in Philadelphia until shortly before game time, then needed a moment to process that the scoreboard did indeed say PHI 9 ATL 0. So the Mets had an opportunity all but secured when they took the field in cavernous Whatever It’s Called Now Coliseum against a thoroughly anonymous A’s team — looking at the enemy lineup, I recognized Stephen Vogt, though I doubt I could pick Vogt out of a police lineup and I had to double-check the ph/v thing.

Granted, I’m not sure I could have picked Chris Bassitt or Mark Canha out of a police lineup when they became Mets in the offseason. (American League + West Coast again.) Their homecoming was a little connective tissue at least, not that it registered much with the crowd, though there are a number of caveats there: a) a lot of visiting Mets fans; b) not a lot of A’s fans hardy enough to care about a lost season; and c) the fans in the Coliseum are so far from the field that you barely register them, unless of course they’re wearing highlighter-yellow shirts and creepypasta expressions.

Ah, the Coliseum. My one visit there left me with respect for A’s fans, a cheerfully ragtag bunch who’ve armored themselves with ironic detachment above a stubborn bedrock faith, and rage at MLB for how it’s treated this franchise and its fans. Here’s a sample from my writeup, which gets even more vicious from there: “[T]he O.co struck me as a Mad Max version of Shea. Instead of Shea/Citi’s tangle of chop shops and unpaved streets and rumbling els, you get caged walkways leading over industrial yards. Eventually, the caged walkways dump you in the vicinity of an ugly gray concrete pile that rises from a weird hill of xeroscaped dirt, which you search for entrances a la Tomb of Horrors.”

I wrote that eight years ago; the stadium’s still there and the A’s are still imprisoned in it, victimized by the twin plagues of sewer backups and piously vaporous statements about their future from MLB. One of these plagues is a nauseating health hazard; the other features shit coming out of drains. A’s ownership has been campaigning for a new stadium at Jack London Square, an odyssey that’s melded corporate blackmail with the toxic NIMBYism of the Bay Area Eloi, while playing a showily indiscreet game of footsie with Las Vegas. Given that baseball is now engaged in constant frottage with the disgraceful sports-betting industrial complex, I’d bet that the A’s head for Vegas. That will be another example of MLB defining deviancy down and rightly unleash a flood of outraged commentary, but not enough of it will be about the fanbase and city that deserved better.

Jesus Fucking Christ, 900 words that read like the kind of screed you’d normally find wrapped around a brick and we haven’t even gotten to the game yet! What is wrong with you today, Fry?

I dunno, but you’re right, there was a game in here somewhere. Alrighty then. Bassitt was his usual indomitable self, picking from his Saberhagenesque arsenal of pitching and sending balls plateward with the ax-thrower motion I find more and more delightful each time I study it. Brandon Nimmo looked thankfully none the worse for Milwaukee wear (though Starling Marte remains distressingly far from returning), Eduardo Escobar hit his first-ever grand slam, Jeff McNeil and Mark Vientos added to the barrage, Drew Smith followed his disastrous return in Milwaukee with a clean inning, and even Darin Ruf got a hit.

The A’s deserve better and I’m angry at a host of entities that have done them wrong, but once the game starts baseball is a zero-sum endeavor, which means no mercy and no quarter. The Mets offered neither, moving to two and a half games up on the Braves Phillies (ed: Jesus) and reducing their magic number to nine. I doubt we’ll make a big show of that countdown in these posts, as you’ll find a season chronicled in our archives where zero never arrived, but the number exists and is in single digits, so pretending otherwise seems like taking it a bit far.

Anyway, it’s nine. Hopefully the Mets and whoever’s playing Atlanta will swiftly reduce it further, leaving us to delve into the new math involving tiebreakers and how a game between the two teams entangled in magic-number computations can reduce a magic number by three instead of two, which is the way mathematics worked until MLB screwed that up too.

Deviancy defined down, once again. I’m telling you, it all started with agreeing to admit the American League exists.

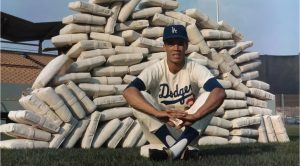

by Greg Prince on 23 September 2022 2:47 pm How is it possible Maury Wills stole only 22 bases at Shea Stadium?

In watching a montage of the thievery that made him famous, it seemed every third clip was Maury swiping second at Shea. That probably owes to the Mets recording and preserving on film more of their game footage than those franchises outside media capitals. When you see highlights of baseball greats from the 1960s and 1970s, you see mostly postseason games, All-Star Games and Mets games. There were only so many baseball greats in Mets uniforms then, so it’s often those in road grays or powder blues who are featured throwing strikes, hitting bombs or running wild.

Maury Wills, who died this week a little shy of his 90th birthday, ran wild. He stole bases literally like nobody before him and he stole bases so that everybody who came after him followed in his footsteps…if they could keep up. Few have.

Wills, shortstop mostly for the Los Angeles Dodgers between 1959 and 1972, was known best for stealing 104 bases in 1962. He was known as a more complete player than that, but like Roger Maris socking 61 home runs in 1961, it was his instant identifier. Those Dodgers of the early ’60s were as much about Maury Wills on the run as they were Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale on the mound. Being in a media capital themselves, they were as recognizable as any baseball players in America.

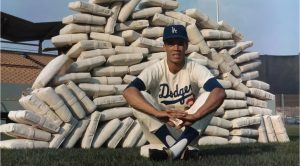

You couldn’t watch Wills, even in the latter stages of his career, which is when I saw him, and not be amazed that he had piled up triple digits in a category where that seemed unfathomable. A photographer once posed him in front of 104 bases. That picture made the rounds quite a bit when Wills was still taking second on hapless batteries. Gaping at the image made his accomplishment only more incomprehensible to me. (Rooting for the generally lead-footed Mets, who never had anybody steal more than 31 bases during their first fifteen seasons, only added to my awe.)

Lou Brock broke Wills’s record in 1974. By then Wills was part of the NBC Game of the Week crew. I saw him wearing his headset while taking part in an Old Timers game at Shea. The Cardinals were the Mets’ opponent that Saturday. Lou and Maury posed together. Brock was already chasing down Wills, eventually totaling 118 bases on the season. It was immense and impressive, just as Rickey Henderson’s astounding 130 bags in 1982 would be, yet like Maris’s 61, Wills’s 104 somehow looms larger as a single-season record than the greater quantities that succeeded it. Lou Brock broke Wills’s record in 1974. By then Wills was part of the NBC Game of the Week crew. I saw him wearing his headset while taking part in an Old Timers game at Shea. The Cardinals were the Mets’ opponent that Saturday. Lou and Maury posed together. Brock was already chasing down Wills, eventually totaling 118 bases on the season. It was immense and impressive, just as Rickey Henderson’s astounding 130 bags in 1982 would be, yet like Maris’s 61, Wills’s 104 somehow looms larger as a single-season record than the greater quantities that succeeded it.

He broke a hundred before anybody. He broke a record that was set by Ty Cobb. He broke a record that had stood since 1915. He woke up an entire sport’s dormant skill set. One shouldn’t say “nobody” stole bases en masse in the decade before Wills came along, but it was practically a lost art. Maury made the basepaths a canvas few were used to seeing. That method of gunning by running, personified at the high end by the likes of Wills, Brock, Henderson and Tim Raines and injecting the game as a whole with hold-onto-your-hat excitement, would take off and not slow down until the 1990s.

Lest we think of Maury Wills as someone who only took from the Mets (54 steals overall), the man attempted to give something back to us. In the Spring of 1993, at the invitation of his old Dodger teammate and current Met manager Jeff Torborg, Wills put on a Mets uniform and served as baserunning instructor for a few weeks in Port St. Lucie. The Mets were thought to have the makings of a potential baserunning machine — they already had Vince Coleman, Howard Johnson and Ryan Thompson and had just added Tony Fernandez — and how could they not benefit from a master class? Not only did Maury steal like crazy, he was a state-of-the-art bunter. “I can’t make them faster,” Wills said, “but I can get them from first to third, across the plate from second.”

That all the expert coaching in the world couldn’t help the preternaturally doomed 1993 Mets get to first base let alone out of last place was hardly Wills’s doing. Maury tried to enhance Vince’s toolkit in particular. Coleman had outdistanced Wills’s 104 SBs three times in St. Louis, where the artificial turf helped him find his way on base. On Shea’s natural grass, Coleman had to try to rev up his offense on his own. “It’s a miracle he’s done what he has without bunting,” Wills said of his primary pupil. They worked together in camp, Vince showed a modicum of acumen, but…well, it was Vince Coleman on the Mets. It wasn’t a bad idea, though. In 1965, the club had hired track and field legend Jesse Owens to coach baserunners in Spring. At least with Maury Wills, they had a ballplayer.

The same could be said of the Dodgers all those years.

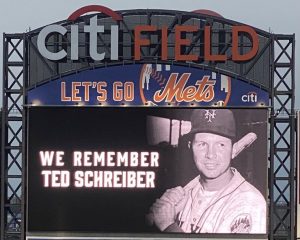

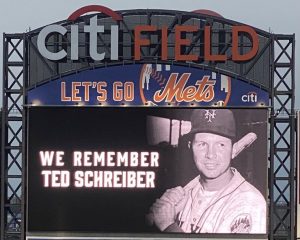

***How is it possible Ted Schreiber didn’t get more of a shot with the 1963 Mets?

That’s something Ted Schreiber allowed himself to wonder in the years following 1963, his only year as a Met, his only year as a big leaguer. “To this day,” he admitted to author Bill Ryczek in the 2008 book The Amazin’ Mets, 1962-1969, “I don’t know how much ability I had.” Ted played on a club that wasn’t exactly lighting the National League ablaze, and you’d guess any youngster with a glove and a clue would have been welcome to show his stuff. Schreiber, 24, was an infielder the Mets went out of their way to acquire, drafting him as a minor leaguer from the Red Sox the previous winter. The previous summer, they’d lost 120 games. Any newcomer should have figured to get a long look, especially one who grew up a relatively short drive from the Polo Grounds.

Brooklyn native (as such, a contemporary of Joe Torre and Bob Aspromonte) and St. John’s alumnus Ted Schreiber, who passed away at age 84 on September 8, should have been right at home on the Mets. Johnny Murphy, who ran scouting, knew Schreiber from the time they shared in the Boston organization. Murphy convinced George Weiss to grab the infielder with the first pick in the Rule 5 draft. Sheriff Robinson, in the ’70s the Mets’ first base coach but in 1963 one of their minor league skippers, had Ted when he ran the Allentown affiliate for the Red Sox. His impression: “Great scrapper. Good power to right-center. Adequate speed. Good arm. Very cocky.” Sounds like a boy straight outta Brooklyn in the 1950s. The Mets got the man they wanted, but maybe not the man their main man — Casey Stengel — wanted. Schreiber had a hunch he just wasn’t Stengel’s guy and, as a result, found himself overlooked early in the season and later, after he was recalled from Buffalo. Only 39 games in the majors, only 55 times to bat.

Aside from him and his manager not necessarily being on the same page, there was the issue of a lack of pages in New York. As a hometown kid, Ted had the savvy to believe he could be a cause for newspapers looking for a good story. Except in the Spring of 1963, the newspapers went on strike, so whatever the James Madison High grad had to offer in the way of colorful copy wound up theoretical. Then there was the issue of not having “a rabbi,” as Schreiber put it, no coach looking out for him the way he noticed Cookie Lavagetto taking Larry Burright under his wing or Solly Hemus mentoring eventual Rookie of the Year runner-up Ron Hunt. All he craved was more of a chance on a club that was losing 111 games with him mostly on the bench — and, as Ted would recall for his SABR biography in the 2000s, “where I was positioned, I needed a long bat if I was going to get a hit.”

Nevertheless, when Ted saw action in September, history would show it was momentous. On the eleventh of that month, with the San Francisco Giants visiting their old haunts, Schreiber entered the game for defense at third base in the top of the ninth inning and Al Jackson protecting a 4-2 lead. The first batter of the inning, Jim Davenport, grounded to Ted, who threw to Tim Harkness for the first out. With two outs, San Fran second baseman Ernie Bowman stepped up, the last obstacle left between Jackson and a complete game victory. Like Davenport, Bowman grounded to third. Like before, Schreiber fielded the ball and threw it to Harkness. Bowman was out. The Mets had won. Nevertheless, when Ted saw action in September, history would show it was momentous. On the eleventh of that month, with the San Francisco Giants visiting their old haunts, Schreiber entered the game for defense at third base in the top of the ninth inning and Al Jackson protecting a 4-2 lead. The first batter of the inning, Jim Davenport, grounded to Ted, who threw to Tim Harkness for the first out. With two outs, San Fran second baseman Ernie Bowman stepped up, the last obstacle left between Jackson and a complete game victory. Like Davenport, Bowman grounded to third. Like before, Schreiber fielded the ball and threw it to Harkness. Bowman was out. The Mets had won.

It was the final game the home team ever won at the Polo Grounds. We’re talking about a ballpark that dated to 1911 (four years before Ty Cobb stole his 96 bases) and a site, Coogan’s Hollow, that had been hosting big league baseball since 1889. Generations of New York Giants fans had ascended to the Bluff above or out to the Ninth Avenue El buoyed by triumph. It didn’t happen too often for Mets fans. When it happened one last time, it was sealed by Ted Schreiber.

The 1963 Mets being the 1963 Mets meant that the last game they won at home wasn’t close to being the last game they played at home. The Mets had seven games left at the Polo Grounds on that homestand after September 11. They lost all seven (including the major league debut of Cleon Jones). On September 18, the Mets pulled down the shades on the matron of the majors for good with a 5-1 defeat at the hands of the Phillies. The last batter? Ted Schreiber, who grounded into a double play that the batter would remember as a ball second baseman and future Met coach Cookie Rojas “made a great play on”.

Schreiber’s last game in the majors came on September 29, at Houston, the season-ender, also a loss. Brand new Shea Stadium beckoned for the Mets, but 1964 would find Ted back in the minors, where he felt he had proved himself by 1963, long after signing with the Sox in 1958. From the Mets system, he’d go to the Orioles’, where he wouldn’t get the call to Baltimore but would provide one more Metsian footnote: at Rochester, he’d take the roster spot of a rising infielder and future manager. We’d come to know him as Davey Johnson.

Ted did not pursue lifer status in baseball. He completed his degree at St. John’s and instead took up teaching. It may have been the role for which he was meant. Visit his Ultimate Mets Database Page, click on the Fan Memories header and learn what he meant to students who remembered him decades after crossing paths with him. You might even say he became their rabbi.

***How lucky was Joan Hodges?

In the end, one supposes, lucky to have lived to almost 96 years of age. Longevity in and of itself isn’t the point when we think about how long Joan lived, a lifetime that lasted until September 17, 2022. The point for all of us cheering her and her cause on from the sidelines was that Mrs. Hodges would get to see her husband, Mr. Hodges, inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

We watched Joan Hodges get her hopes up and then have reality let her down for some fifty years, and that was after reality dealt her and her family a crushing blow. Some luck. A heart attack took her husband Gil two days before he was to turn 48. We lost the manager who led us to a World Series title and respectability all at once. She lost the love of her life. Her children lost their father. Whatever else they would do, Joan, son Gil Jr. and daughters Irene and Cindy would make it their business to see Gil get his due.

So we got to know Joan to an extent that we considered her an essential member of our baseball family. We saw her solemnly accept Gil’s jersey from GM Bob Scheffing when No. 14 was retired in 1973. We saw her at anniversary celebrations of the 1969 Mets. We saw her whenever there was an event commemorating the franchise’s proudest milestones, because pride in the Mets didn’t really enter the picture until Gil Hodges took over as manager. Joan represented Gil for as long as health would allow her. The kids, long adults by the 21st century, would, too, but it was Joan we instantly recognized on TV, in interviews, at Shea. Joan was always gracious, always classy, always selfless. She was making the appearances she did on behalf of a man who’d been gone since 1972. We never forgot Gil Hodges. Maybe it’s because we have a strong memory. Maybe it’s because Joan Hodges wouldn’t let us.

One suspects had Gil lived he wouldn’t have said one word on his own behalf for the Hall of Fame. That’s not who he was. But he was a Hall of Famer, and Joan knew it, the kids knew it, we knew it. It took a half-century to convince those who could do something about it. As the decades went by and Gil went unelected, we couldn’t help but wonder if Gil’s day would ever come, and if it was gonna come, would the woman to whom it meant more than anything be around to see it?

We got our answer on December 5, 2021. The most revered manager the Mets ever had in Queens, the ballast of the powerhouse Dodger lineup in Brooklyn, a first baseman who by all accounts could’ve given Keith Hernandez defensive tips, was chosen for Cooperstown, scheduled for induction in the summer ahead. By this point, with their mom not up for traveling, one of the kids would have to head Upstate and accept. But Joan, still living in the Borough of Churches all these years later, still keeping the candle lit for her love and her cause, would be able to watch it on TV. Whatever was on her mind in her final weeks, she could think of her husband as a Hall of Famer and know it wasn’t only her thinking it.

Though many of us came to picture Joan as the vigilant widow, smiling through perennial disappointment, after she passed, I went to YouTube to see her in a different context. It was the best context in the world: October 16, 1969, Mets 5, Orioles 3 on the scoreboard, Mets 4 Orioles 1 in the Series. Lindsey Nelson’s on assignment for NBC interviewing anybody and everybody. Before he can direct his attention to the players, he is compelled to exchange words with balding, clubby men in suits far less colorful than his own. Then, like a blast of Retsyn from a freshly popped Certs, appears a lady in a green-and-white checkered coat with fur-lined collar, formidable dark red coif, and eyes protected from flying champagne by shades stylish for any era. She could very well be one of my mother’s friends from the beauty parlor.

“Here’s Mrs. Gil Hodges,” Lindsey informs the viewing audience. “Hello, Joan. He was here,” he tells her in case she just happened to be wandering by in search of her spouse. “Here’s Mrs. Gil Hodges,” Lindsey informs the viewing audience. “Hello, Joan. He was here,” he tells her in case she just happened to be wandering by in search of her spouse.

“Lindsey, oh I just can’t believe it!” is her high-pitched response. “It’s been a year of miracles, and it’s marvelous, really, really marvelous!”

And then Joan Hodges moves on, presumably finding her husband so they can share this greatest of moments together. You’d like to believe that somewhere they’re sharing it still.

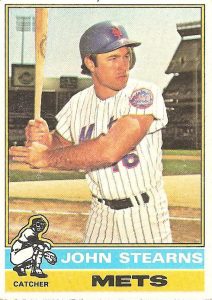

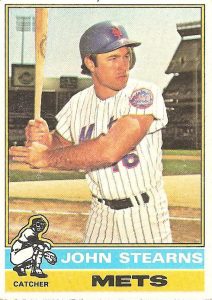

National League Town remembers Mr. Wills, Mr. Schreiber, Mrs. Hodges and Mr. John Stearns on its current episode. You can listen to it here.

by Greg Prince on 22 September 2022 1:54 pm Brandon Nimmo finally remembers how to steal bases and in activating his dormant skill aggravates a quad that merits exiting the game early, receiving imaging later and monitoring on a day-to-day basis.

But I don’t want to talk about that.

Jeff McNeil throws his body into every possible defensive play and has trouble getting up a couple of times, getting up anyway, yet leaving you worried he’d just lie there after one too many acts of all-or-nothing derring-do.

But I don’t want to talk about that.

Mark Canha keeps attracting pitches to his person and he establishes a franchise record for getting hit by them (24) and the team establishes a major league record for getting hit by them (106).

But I don’t want to talk about that.

Tomás Nido, a very good bunter but lately a quite decent hitter, attempts a bunt at a not particularly opportune time to do so — the Mets trail by one in the seventh with a runner on first and nobody out — only to bunt badly (twice) then strike out, signaling yet another rally that will fade into the Wisconsin ether.

But I don’t want to talk about that.

Drew Smith, off the IL after nearly two months, is brought in to face his first batter with the bases loaded. The batter, Mike Brosseau, responds with a grand slam.

I really don’t want to talk about that.

The Mets, down 1-0 to the Brewers in Milwaukee going to the bottom of the seventh, headed to the eighth down 6-0, and the score never budged from there. The Atlanta Braves had already lost to the Washington Nationals, an inverse of everything we’d expect from a sentence involving those two combatants, so the Mets, by losing, would lose only the opportunity to extend their first-place lead, not a share of first place. On the menu of undesirable choices, you’ll take one that isn’t a total loss.

But I don’t want to talk about Taijuan Walker keeping the Mets viable through six only to have stayed in a little too long; or David Peterson not fully solving the situation Walker bequeathed him in the seventh; or any more about Smith being tossed into the fire and Wednesday’s game immediately going up in flames; or the Mets producing only four hits all day after producing only four hits the night before, except two of the four hits the night before were a three-run homer and a grand slam, while none of the four hits the following afternoon were anything of the sort; or that after finally snapping their obscure/specific streak of not winning a penultimate game in a series at Milwaukee since 2008, the Mets find themselves not having won a final game in a series at Milwaukee since 2015.

Ah, crap. I guess I just talked about all that. Well, on to the stuff I’d prefer to talk about.

***I want to talk about Willie Mays in the wake of the Mets disseminating photos of retired Number 24 having been installed in Citi Field’s left field rafters (rafters — a word you can’t necessarily define but you know exactly what it means) where it will greet fans for the final five games of the regular season, then every game they play in the postseason, then forever after. Willie sprinted to mind as Brandon left the game Wednesday. It would be understandable if center fielder Nimmo has to miss a little time, just as almost every Met has had to miss a little time this year, some more than others.

A daily if not everyday phenomenon. Center fielder Mays, in his prime, almost never missed time. Citing his father working five days a week in an Alabama steel mill and then spending his weekends as a Pullman porter on a train that rolled to Detroit and back, Willie said in his 2020 book 24, “I was taught if you can go out there and walk around, you could play. I played every day.” His co-author John Shea added, “The easiest three seconds of a manager’s job was writing Mays’s name on a lineup card.”

From the beginning of 1954, when Willie was out of the Army (age 22), to the end of 1966 (age 35), the Giants played 2,048 games. Mays played in 2,002 of them, or 97.75% over a span of thirteen seasons. Some of that was no doubt luck. Most of that was Willie’s determination and his managers’ common sense. This was Willie Mays. You didn’t not play him — and Willie didn’t not play like Willie Mays when he was in the lineup, which is to say like a dozen Nimmos blended with a dozen McNeils. Said one scout who focused on him solely during one random game, “The man is never still out there,” not only on the move for the ball or an extra base, but taking charge of his teammates’ defensive positioning while playing the field. And that was with the demands of being Willie Mays to a general public that ceaselessly sought his attention.

From 1954 through 1966, Willie Mays averaged 109 runs batted in annually. The last two Mets to drive in runs, Pete Alonso (three-run homer Tuesday night) and Francisco Lindor (grand slam one inning hence), have played in 150 of 151 games this season. They’ve driven in, respectively, 121 and 99 runs. And though we’re in an era when the phrase “load management” has entered the sporting lexicon, how often could have you seen Buck Showalter making the case for sitting either Alonso or Lindor? The DH is a compromise that didn’t exist for Mays, and maybe that’s helped a day here or a day there, but Pete and Francisco have both gone to the post daily, bruises, fractures and general soreness notwithstanding. I seem to recall Leo Durocher saying all Willie needed was a rubdown from the trainer and he was good to go. Conditioning has advanced a bit since the 1950s. Rest is sometimes the better part of valor. Yet the Mets lead the Braves by one game. Alonso knows it. Lindor knows it. Showalter knows it.

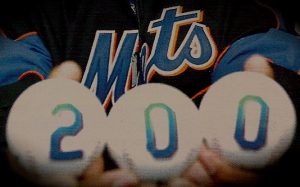

***I want to talk about Max Scherzer winning his 200th game on Monday night. Under circumstances that didn’t include the clinching of a playoff spot, that milestone would have been the big story, or at least shared space with Max pursuing perfection. He threw six innings without allowing a baserunner before departing, and it was somehow no big deal that a shot at a perfect game was dismissed in the big picture Max has been such an enormous part of painting. Personal glory isn’t Max’s goal. He’s had plenty of that in a career that goes back so far that it included a stop at Shea Stadium as an Arizona Diamondback. Scherzer’s thrown no-hitters, won Cy Youngs and can brandish a World Series ring. He seems to like that last bauble most of all and considers adding to it his overriding priority. Preserving his right arm after a trip to the injured list was more important to him than attempting to join one of the most exclusive clubs in sports. Only 23 pitchers have notched perfect games. None has done it since Felix Hernandez in 2012. If this were a year like 2012 for the Mets, maybe Max Scherzer makes it clear to anybody who’s ostensibly his supervisor he’s not leaving before the seventh inning.

He’ll settle for being in the pretty exclusive company of those who’ve won world championships twice. His accepting a seat after six innings doesn’t guarantee that, but his distinctive eyes recognize the prize and what goes into attaining it. As for 200 wins as an afterthought, that, too, felt selfless. Max seemed way happier that the Mets had made it to the playoffs than that he’d made it to 200. Yet 200 is essentially the new 300, and deserves to be celebrated. Among active pitchers, only Justin Verlander and Zack Greinke have more wins than Scherzer. Nobody’s threatening to bump Randy Johnson from most-recent status among pitchers who’ve reached 300. Before Johnson, the most recent 300-game winner hit the round number in a Mets uniform. I’m fine not talking about him.

Only four Mets have had cause to handle these particular baseballs. Before Scherzer, three pitchers won their 200th game in a Mets uniform. Like Scherzer, they were each varying levels of great before donning the orange and blue. Like Scherzer, we found ourselves grateful to have their services late in their careers.

• On July 22, 1999, Orel Hershiser clocked his 200th win while a Met. From the perspective of 1988, that would have sounded like a fever dream. In 1999, it added up beautifully. Since 40-/41-year-old Orel lent his veteran presence and what was left of his considerable skills to the Mets’ playoff push, I’ve never thought of him as anything but a Met, and that’s with full cognizance that Hershiser received the NLCS MVP for what he did against the Mets as a Dodger eleven years before. In 1999, that seemed like trivia.

Hershiser’s 200th win came in Montreal, included two hits of his own, and inadvertently touched off a uniquely 1999 Mets controversy. Orel’s milestone was reached in the same series as one for another veteran presence not automatically associated with the Mets, Rickey Henderson, who passed Willie Mays for fifth place on the all-time runs scored list. What Hershiser and Henderson accomplished was certainly worthy of celebration as soon as the Mets returned to Shea Stadium from Olympic Stadium. Instead, Shea hosted what amounted to Sammy Sosa Appreciation Night as they began their next homestand. Technically it was Merengue Night, which brought in a lot of Dominican customers whose interest in supporting the locals was limited, particularly when Sosa — the summer after he racked up 66 home runs as a Cub — was honored pregame, while — as Bobby Valentine noted — Orel’s and Rickey’s career achievements went unnoted by the home team’s upper management. This was the same homestand as Mercury Mets Night. As Cindy Adams might have said, “Only the 1999 Mets, kids.”

• Seven seasons and a seeming lifetime later, on April 17, 2006, Dominican icon Pedro Martinez won his 200th game as a Met, cause for cheers throughout Shea Stadium, where the opponent was the Braves and the evening’s promotion was simply the home team continuing its fantastic start. The Mets were 10-2 and burying their erstwhile tormentors five games behind them. Martinez was treated to a postgame presser in front of a “200” banner in distinctly Metsian colors.

• On August 8, 2014, in a year that was little like 1999, 2006 or 2022 in terms of the Mets going anywhere near the playoffs, Bartolo Colon made it to 200 wins as a Met, besting the Phillies in Philadelphia. Bartolo was 41 then and, really, just getting started on scaling the next level of his career. By 2015, he’d part of a postseason staff for the Mets. Before he’d leave Queens following 2016, he’d be a bona fide folk hero.

In all, twelve pitchers who’ve pitched for the Mets have won 200 games in the major leagues, even if only four won their 200th as Mets and none has won 200 for the Mets. Tom Seaver holds the franchise mark with 198, and you can throw a few extra darts at your M. Donald Grant dartboard if you like for depriving us of all the milestones Tom should have reached as a Met.

At the end of July, you might recall, we toasted the pitchers who made it to the not-too-shabby 100-win club as Mets after Carlos Carrasco, now up to 104, turned the trick. Because I went to the trouble of looking it up, I will now share with you the identities of the most accomplished pitchers to have logged time with the Mets without doing anything remotely like what Carrasco, Scherzer or anybody who ever won a game as a Met did.

There are eight members of the 100-win club who pitched for the Mets yet never won a single game as a Met.

They are…

Dick Tidrow

Dave Roberts

Ralph Terry

Chan Ho Park

Doc Medich

Aaron Harang

Dean Chance

Kevin Tapani

Tidrow was a reliever at the very end of his distinguished career when he came and went as a Met in 1984, just as the stars at Shea commenced to rise in earnest. Roberts’s arm could also be said to have been on its last legs in 1981; unlike Dick, Dave couldn’t say he was around for the start of something special, as the team Roberts joined was still wallowing at the bottom of its division. Roberts, as a Padre, finished second in NL ERA in 1971, a fact commemorated by a 1972 Topps card that places his head next to that of the league leader: Seaver.

Terry, as we mentioned in March, did something bigger than collect a Met W during his 1966-1967 Met stay. He taught Tug McGraw how to throw a screwball. Chan Ho Park was one and done in 2007 in terms of games pitched as a Met. The game was a 9-6 loss to the Marlins on April 30. Park’s ERA was 15.75 before moving on to several more organizations and seasons of pro ball. Medich’s lone Met appearance at the ass end of 1977, the year we lost Seaver the first time, amounted to a pre-free agency audition. Doc had already put in his share of innings for the 1977 A’s, who lost 98 games, and the 1977 Mariners, who also lost 98 games. On September 29, Medich lost to the Pirates. It was the 96th defeat for the 1977 Mets, who’d go on to lose…98 games. Medich was either a victim or a carrier. Either way, he’d sign with the Rangers.

Aaron Harang actually pitched pretty well (3.52 ERA) for the September 2013 Mets when warm bodies with loose arms were welcome to try and ply their craft. Four starts resulted in zero wins for the perfectly competent righty who went on to pitch two more seasons after he stopped by these parts for a month. Also in the category of September-only Mets was Dean Chance, once upon a time a Cy Young Award winner for the Angels. That time had passed by 1970, when Chance was picked up late to do what he could for the Mets’ rapidly faltering attempt to repeat as champs. Dean pitched in relief thrice to an ERA of 13.50. No wins, or he wouldn’t be mentioned here.

Mentioned here but different from all the other oh-and-sorry Mets is Kevin Tapani. Tapani indeed won 100+ games in the majors, 143 to be exact. Unlike the aforementioned characters, Tapani’s 143 victories came after, not before, he was a Met. The righty appeared in three games as a rookie in 1989, barely enough time for his arm to clear its throat before he was thrown into a deal I seem to invoke at least three times a year, the Frank Viola deal, also known as the Rick Aguilera deal, at least once known as the David West deal. It was five-for-one, the one being Twins superstar lefty Viola, the five being Aggie, West, Tim Drummond, Jack Savage and Tapani. Aguilera, winning pitcher of Game Six of the 1986 World Series, merely the most dramatic game the New York Mets have ever played (don’t ask to see his line), was the best-known quantity going to Minnesota, but the Twins definitely saw something comparably appealing in Tapani. Within a year of his leaving the Mets, Kevin would be a staple of the Twinkie rotation. A year after that, he’d be a 16-game winner and, oh by the way, a world champion, alongside Aguilera and West. Viola was leaving for free agency by then, having won 20 games in 1990 and making the All-Star team twice as a Met, but not taking his new team any farther than a little shy of the gates to the promised land.

Had Viola had the two months we hoped for in 1989 or a second half on par with his first half of ’90, and the rest of the Mets done slightly greater things, too, we might still talk about Sweet Music and that trade today. Or had the collective output of Aguilera, West and Tapani measured up to that of Nolan Ryan after 1971, we might be reminded regularly to rue it with relish. Instead, I seem to be the only one who brings it up on the reg. I don’t do it to condemn it. I think it was worth the risk. Frank wasn’t bad as a Met. He just wasn’t great.

Good on Aguilera (and his fortuitous birthday) for converting himself into an elite closer. Good on West (and his fortuitous name) for cobbling together a lengthy career as a lefty reliever. And good on Tapani, a lad of 25 when the Mets decided he was disposable, for notching those 143 wins in a career that extended into 2001. Kevin also lost 125 games. One of those came when he was a Cub, at the hands of the Mets, on July 23, 1999.

You might recognize the date as the Merengue Night Sammy Sosa was feted lavishly at Shea Stadium.

***I want to wind down my avoidance of the Mets’ 6-0 Wednesday loss in Milwaukee by talking about the only Met in the 100-win club to have won exactly one game as a Met. That was Rick Porcello, who notched a pretty fair round number while calling Citi Field home, Win Number 150 in a career that would have no more wins beyond that and no more years beyond his one Met season of 2020.

I’m not exactly looking to dwell on Rick Porcello, a former Cy Young winner in the tradition of Chance and Viola, other to remember his Met tenure in the context of that most recent spate of years we put behind us on Monday night. Porcello was one of the unlucky Mets. He was a Met when the Mets didn’t qualify for the playoffs. There are a lot of those in our history. Porcello may have been triply unlucky, because he grew up a Mets fan in New Jersey and really cared about the Mets making the playoffs for more than the standard competitive reasons — and because 2020 was inarguably the worst year to pitch in front of the home crowd as a Met because there was literally nobody in the ballpark when you pitched. Chalk it up as a symptom of pitching amid a raging pandemic.

Porcello’s record of 1-7 with a 5.64 ERA isn’t what I remember when I think of his Met tenure. I remember his Zoom-delivered remarks after his final outing and loss, following the doubleheader that officially eliminated the 2020 Mets from contention:

“I’m sorry we could haven’t done better for you, and given you something to watch during the postseason. I wish I could’ve done better for this ballclub. Unfortunately, we’re out of time. I gave it my all and it wasn’t good enough for us.”

Usually when the Mets emerge from one of their playoffless droughts, I think back on the players who toiled without proximity to the ultimate reward, and think, too, about the players who endured in those seasons and made it to the season that certifies we’ve arrived in another timeline. When the Mets clinched their postseason berth on Monday, I wasn’t really that moved to think in that direction. It had been long enough from 2016 to 2022, but it hadn’t been that long. Not 1973 to 1986 long, or 1988 to 1999 long, or 2006 to 2015 long. It didn’t feel remotely as long as 2000 to 2006, even if it was the exact same number of years.

But, like I said, it had been long enough. So I thought a little more and I thought of Rick Porcello and his lone win and heartfelt apology for his team and him not winning more. I thought of Michael Wacha, who I pair with Porcello as veteran starters who in 2020 were seeking to recapture what once made them stars elsewhere and neither of them finding it. I thought of Todd Frazier, maybe the signature Veteran Met of his day, which included the one year in the five barren seasons between 2017 and 2021 that encompassed a genuine playoff stab, even if the stabbing fell shy of its target in 2019. I thought a little of Jed Lowrie, who probably worked harder than we’ll ever know to take a few at-bats in 2019, yet all we remember is he never played an inning in the field while under contract to the Mets through 2020.

I thought of how quickly the door spun in 2017 and 2018. I thought of the final game in 2017, an 11-0 thrashing at the hands of the Phillies that pointed Terry Collins to the exit. Five Mets played their final major league games that day. One, Nori Aoki, was here out of Aaron Harang circumstances, a veteran who was available when injuries otherwise swallowed a chunk of the roster. Aoki went home to Japan and is still playing ball. Four were rookies, one of whom, top 2012 draft pick Gavin Cecchini, at least got a sip of celebratory champagne as a 2016 callup. The other three, relievers Kevin McGowan and Jamie Callahan and outfielder Travis Taijeron, were new to the bigs in 2017. All they tasted with their cup of coffee was the dregs of a 92-loss season.

I thought of Austin Jackson, who had a solid career, and Jose Bautista, who had an outstanding career. Nobody thinks of them as Mets, but I did, because they were among us in 2018. Ditto Adrian Gonzalez.

Anybody remember Jack Reinheimer? AJ Ramos? Tyler Pill? Tyler Bashlor? Neil Ramirez? Jose Lobaton? Buddy Baumann? Hector Santiago? Brooks Pounders? Donnie Hart? That once we wondered how to fit Brad Brach and Brad Hand into our bullpen? That Dellin Betances once loomed large in those plans? That there was a Bench Mob and Cameron Maybin was briefly a part of it, an entity anchored by Kevin Pillar and Jonathan Villar and personified by Patrick Mazeika? That when 2021 wound down, we faced the loss of Noah Syndergaard, Michael Conforto, Marcus Stroman, Javier Baez, Aaron Loup and Rich Hill and you could have made a reasonable case for bringing any of them back?

When was the last time you thought about those guys? Outside the main team store on Sunday, where they have the discount rack, the SYNDERGAARD 34 merch was abundant. And untouched.

It wasn’t really one of those droughts where when it’s over we congratulate ourselves for making it at last. It wasn’t a period when we got to know terribly well too many of the short-timers and day players who filled out too many losing box scores. But we’re Mets fans and they were Mets, whether they were Mets in a good Met year or not.

This has been the kind of Met year we would have killed for in 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021 or any year that hasn’t resembled in the least 2022.

This has been a very good Met year. A very good Met year in which a bunch of Mets who endured all or some or one of those previous arid Met years have merged their abilities with Mets who were somewhere else altogether before 2022 and in unison they became the 2022 Mets, one of the best Met teams that’s ever been.

A very good year. One of the best. Three Met teams have spent as much as a day 40 games above .500. One of them is this one.

Ten Met teams have qualified to spend as much as a day in the playoffs. One of them is this one.

We want this one to be a division champion, a league champion and a world champion. We’ll see what happens on those counts.

In the meantime, what they’ve done and what they’re doing is really something worth talking about.

A new episode of National League Town is out. Jeff Hysen and I celebrate these 2022 Mets having the pre-Jamaica portion of their postseason ticket punched and pay tribute to a few members of the Mets family we’ve recently lost. You can listen here or on your favorite podcast platform. Honestly, you should listen anywhere you can.

by Greg Prince on 21 September 2022 3:01 am Pete Alonso grabbed his lumber

And laid on the Brewers

A three-run number

When Francisco Lindor

Saw what Pete had done

He bettered Pete’s bomb

By a sum of one

That’s basically the story of how the Mets employed a Lizzie Borden-style attack in Milwaukee Tuesday night to hack their way to a 7-5 victory in the penultimate game of their series at Miller Park.

HOLD EVERYTHING! The Mets won the penultimate game of their series at Miller Park! Or whatever it’s called now. From 2009 through 2021, the Mets never won the second-to-last game in any series they played in their annual trip to Milwaukee. Never, as spelled out in this 2016 examination of the trend, and never, as confirmed in this 2021 update of the trend, revisited a year ago because this particular and peculiar string continued to defy snapping.

This year however, isn’t interested in what the Mets could never do before 2022. This year, the Mets consider what can be done and then, far more nights than not, they go ahead and do it. They come from behind; they beat the Brewers the night after clinching a postseason berth; they stay ahead of Atlanta for the postseason berth they want most; they win their sixth in a row; they obliterate the memory of being swept by the Cubs a week ago; they soar 40 games above .500 for the first time in 34 years; and they break the most obscure or at least most specific losing streak in North American team sports.

Happy yet? Provisionally even? Or did the glow from the cream soda with which you toasted the mathematical securing of no worse than Wild Card qualification Monday night wear off as Carlos Carrasco nearly drowned in a deluge of hops, barley and pure, high-quality water sourced from deep lakes, cold springs and ancient aquifers in the early innings Tuesday, particularly the second, when the Brewers posted three daunting runs on the No Longer Miller Park scoreboard? Perhaps the Mets really were hungover from their something slightly stronger than Dr. Brown’s-fueled celebration. Perhaps they were due for a Midwest, mid-evening nap. Perhaps all your anxieties were bound to surface after five consecutive nerve-quelling contests.

Oh, like your nerves were quelled by five wins in a row let alone a guaranteed playoff spot. If anything, heightened stakes heightens tension. I found myself rounding into postseason form as Tuesday’s game went along, which is to say I was utterly on edge and manufacturing dread with every pitch. Usually I wouldn’t wait for the pitch. Between pitches provided ample time to create worst-case situational scenarios all adding up to grim projections for the game at hand, for the season remaining, for the limited engagement to which we were condemning ourselves come October.

But then came Pete, with his three-run missile in the sixth, lopping the Brewers’ lead to 4-3, and then came Francisco, with his grand slam erasing their advantage by vaulting the Mets ahead, 7-4, in the seventh, and I could sit back.

And worry some more.

What, you thought seven runs in two innings, built on two blasts that capitalized on Brewer pitching placing runners on base, would calm a Mets fan in September? It wouldn’t calm a Mets fan in October, and suddenly October is a) officially a given; and b) approaching at Terrance Gore speed. A Mets fan wouldn’t be a Mets fan without rehearsing the worst and meaning it.

Thus, my apologies to Trevor May for all the miserable things I barked at you as you wriggled out of the seventh, and no hard feelings, I hope, regarding what I was thinking of you, Adam Ottavino, as you gave way to Edwin Diaz in the eighth. Once Diaz was on, I actually did relax. Well, once he got out of Ottavino’s eighth-inning contretemps that had cut the Mets’ lead to 7-5. I was more than a little antsy when Edwin missed with a slider to let Rowdy Tellez work his at-bat to one-and-two with the tying run on first and two out.

You think I’m kidding.

The bottom of the ninth served as the kind of sedative Joey Ramone would have treasured. Diaz threw eleven pitches. One was fouled off. One was grounded out. Everything else was a called or swinging strike, including the last six pitches Sugar delivered. We were fine and remain fine and will be fine until, of course, we are not.

That’s how a Mets fan negotiates the postseason. No point in waiting to drive yourself crazy.

by Jason Fry on 20 September 2022 12:32 am The Mets said all the right things after taking apart the Brewers Monday night — how they’d picked each other up all year, how it was a great bunch of guys, how this was just a first step, how they had other goals.

All the stuff a team that’s clinched October plans but nothing more specific in terms of a destination ought to say — not with the Braves staying stubbornly behind them, like the metaphor-freighted posse Butch and Sundance couldn’t seem to shake. Newman and Redford at least needed to peer into the distance to spot their pursuers; the Mets don’t have to look more than a length behind. (And we know “those guys” all too well.) The outcome of that particular pursuit will occupy our thoughts for another two weeks and change — the blink of an eye during the course of a baseball season but an eternity for an anxious fanbase.

But but but but.

This is what we’ve done all year — spend a remarkable season worrying about the gap between “really, really good” and “could be even better.” Well, until the Mets and Brewers go back into battle Tuesday night, we’re all relieved of that particular duty.

Max Scherzer faced 18 Brewers. Max Scherzer retired 18 Brewers. There’s one place where that Mets-fan gap — the one studded with but but buts — simply didn’t exist. Max literally couldn’t have been any better. He was electric, determined and everything we ever dared to hope he might be, collecting a richly deserved 200th career win.

Pete Alonso has worried us to no end of late, but it was Alonso who took Corbin Burnes deep, smashing a three-run homer into the upper reaches of Miller Park to give the good guys a heckuva jolt (and, by the way, to bring that club RBI record a little more easily in view). On the couch up here in Maine, I let out a primal scream and applauded so hard that my hands hurt for half an hour.

But the other Met bats contributed too, drilling ball after ball up the gaps, most dramatically with back-to-back triples from Brandon Nimmo and Francisco Lindor, most emphatically when they answered a Rowdy Tellez two-run homer with an immediate two runs of “oh yeah?” — authored by Tyler Naquin and Tomas Nido, no less.

We have October plans, after a long stretch of accentuating the positive through gritted teeth, or sometimes just the gritted-teeth part. We’re back in the conversation we’ve been left out of for far too long, back in the fight that truly matters, back where we sometimes let ourselves stop imagining we belong.

The Mets took a small step Monday night, or at least that’s what they treated it as. But it was a giant leap for Metkind — whatever explorations lie ahead.

by Greg Prince on 19 September 2022 1:06 am Glop is the word that occurred to me after sitting through the Mets and Pirates getting gloppy with one another at Citi Field Sunday afternoon. I don’t even know if I’ve ever used the word glop before, but it seems to fit. I had to look it up to make sure it really is a word. It is. It refers to a baseball game in which one team commits four errors, issues a half-dozen walks, hits one too many batters, strikes out twenty times and generally stretches the parameters of what constitutes a “professional” baseball team (they get paid, but otherwise, what a bunch of amateurs), yet that team remains competitive in this game almost to the end because the opposing team turns first, second and third bases into America’s fastest-growing retirement community, while its virtually literally untouchable ace pitcher comes down with an acute case of the touchables.

Hold on, I have to take a phone call from the bottom line. I’ll put the bottom line on speaker phone so you can hear what it has to say.

“Yeah, hi, Greg. Just calling to let you and anybody reading this know Sunday’s game looks good from my perspective. All I see is the final score, which was Mets 7 Pirates 3, meaning the Mets swept the Pirates and remain in first place by a game over the Braves. I don’t really see anything else. Gotta go. Bye.”

As you just heard, the bottom line hung up before I could dissect the myriad elements I found disturbing during Sunday afternoon’s game at Citi Field. Typical bottom line.

Really, I have no beef with the bottom line. Give me a Mets win, and I’m clam happy. And, honestly, I was clam happy the whole homeward-bound journey, from the descent down the stairs to the Rotunda, through the weaving in and out of slow pedestrian traffic to the 7 Super Express platform, and in the LIRR’s hands from Woodside to Jamaica and beyond. The Mets did pull out a win that for much of the day seemed predestined and in the end went official. It was never fully exquisite, but it seemed to be getting its job done. Still, dropped into the middle of it were a couple of innings of searing doubt, an interval when aspects of the glop became too gloppy to ignore. Fortunately, the most repelling portion of the glop was eventually whisked away.

Thus, here I sit, happy as that aforementioned clam, even if I spent several hours squirming in my Excelsior seat wondering what all 36,291 of us in attendance had done to deserve this game.

I have the feeling that if I was planted on the couch watching what unfolded, the glop wouldn’t have necessarily oozed through the television screen so tangibly. It was from watching this in person that I couldn’t ignore not only the subpar aesthetics but their potential impact on the bottom line before the bottom line made itself clear. There was a sense of occasion that was curdling by the inning.

Since 2008, Stephanie and I have attended the final Sunday home game of every season but two (2011, before it evolved into our thing, and 2020, a year when the ballpark admitted only cardboard cutouts). Often this outing coincides with Closing Day. The first, in 2008, was Shea Goodbye, the ultimate Closing Day. That was in a category all its own. The second, Citi Field’s first Closing Day in 2009, was seminal. We were able to wrangle semi-reasonably priced seats in 327 — third base side, in the shade, only as close as we need to feel to the field, helluva view if the game isn’t altogether absorbing — which became our favorite spot in the ballpark. Maybe not my favorite spot for all games, but definitely our favorite spot for our game. That Closing Day, my 36th game of Citi Field’s inaugural season, was probably the first time I decompressed from my smoldering resentment of Citi Field’s existence and concomitant role in Shea Stadium’s demise. That’s right, I willingly went to 35 games kind of angry at the facility at which I was regularly spending time and money. I had to keep taking one more taste just to make absolutely sure I didn’t care for what I was sampling.

The preferred view on certain Sundays. Game 36, in 327, began to nudge Citi Field into my tolerant graces. Good graces would take a while longer. Even in the crummy seasons with their desolate Septembers, I looked forward to our day or, if ESPN was being a jerk about it, night in 327. Sometimes I’d settle for 328. Sometimes I’d hit StubHub paydirt and land 326. But let’s call it 327 for convenience sake. I scanned the resale market this week until I found something I considered doable from a purchasing standpoint. In those crummy seasons with their desolate denouements, 327 can be extremely reasonable. The first-place Mets of the moment are a hotter ticket on weekends than I’d prefer. Except for the first-place part. I wouldn’t change that.

Without necessarily aiming for a reduction in attendance, I’m really not the “I’m going to the game” guy I used to be. I always liked hearing myself say, “I’m going to the game.” “I’m going to the game” was practically my way of life once Shea cleared its throat to deliver its adieu. That ethos carried over into Citi, the place I already mentioned I didn’t love, yet you couldn’t have discerned that from The Log II, the steno notebook in which I record the most vital stats from every game I go to. After the 36-game tasting menu of 2009, I never went to fewer than 26 games in any of the succeeding half-dozen regular seasons, or just enough to decide I guess I kinda liked Citi Field sorta OK.

Yet I haven’t been to as many as 25 games in a season since 2015 (when The Log II opened its postseason section), as many as 20 since 2016, or as many as 15 since 2018. I haven’t set foot inside frigid Citi Field in April since 2017 and have gone on back-to-back dates only once over the past five years. The whole business of going to the game as a matter of course has become just a little too much for me. Too much in multiple senses of the phrase. Mostly I’m comfortable on that couch, enjoying the multiple camera angles delivered on that television, relishing the company I keep with the voices emanating from the speakers (they don’t know that I’m the fourth man in the booth, filling in their blanks for them, even if they can’t hear me doing so). Some nights I think, “man, that would have been a fun game to have been at,” only to think a second later, “man, it’s great that I’m already home.” That’s the tradeoff, I suppose. I continue to Log just enough games every year so my self-image as a ballpark regular, pretty much all I ever aspired to be when I was a kid for whom Shea loomed as Oz off the Grand Central, remains legitimate in my mind, yet maybe not so many that novelty isn’t baked into the bargain. Sometimes there’s nothing I’d rather do than go to the game. Sometimes covers it nicely.