The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

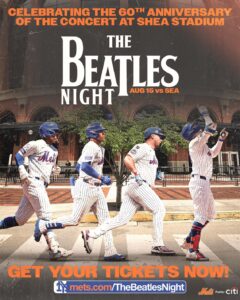

by Greg Prince on 13 August 2025 2:45 am It throbbed. It pulsated. It got down with the beat, not to mention the Bear. It lit up like crazy, so much so that they shot off every last firework within reach. Maybe this is what the Ritchie Family was referring to in 1976 when they paid homage to the best disco in town.

Citi Field grooved on Tuesday night as Pete Alonso went clubbing and we all went along with him. We were up on our feet when Pete belted the 253rd home run of his Met career, which instantly became the most of any Met career. Our third-inning response was so nice, the Polar Bear saw fit to do it twice. Following Pete’s sixth-inning blast, the club record therefore ticked up to 254.

You know who holds it. And you know who couldn’t hold back its appreciation? This crowd.

Yeah, we were into Pete Alonso passing Darryl Strawberry for the franchise long ball mark. And we were into Alonso passing himself to establish another franchise long ball mark. We were into Francisco Alvarez going deep two times, Brandon Nimmo homering with two men on, and Brett Baty icing the cake with a homer of his own.

Oh, by the way, the Mets won this curtain call carnival in which they slugged like they forgot that they had forgotten how to slug for the last week and change. They scored 13 runs in all, every last one of them with two outs. They allowed five to whoever they played (the largely irrelevant Braves), which appeared to be a problem when the score was briefly 5-5, but the bats were out for the home team. So were the fans.

We came to praise Peter, who out-Berry’d Straw. This was a night to overlook that Clay Holmes couldn’t escape the fourth inning, and that the Cincinnati win over Philadelphia represented a mug half-full situation, as we’re five behind the Phillies for the NL East lead but only two ahead of the Reds for the final Wild Card slot. It was even a night to overlook that this Met win, as rousing as it was, was their first in eight games. We eventually got the pitching necessary to put 0-7 behind us, thanks to Gregory Soto coming in way earlier than usual (the fourth) and Justin Hagenman staying in way longer than could have been forecast in a game that wound up a 13-5 romp (Justin no-hitting Atlanta from the sixth through the ninth earned him one of those delightful “no, really” saves).

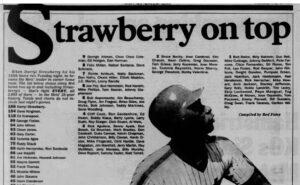

Pitching, however, could not be the theme of the night when Pete Alonso was crashing and remaking history. When he swung off Spencer Strider — now there’s a swing-off that means something — and the result was laser-tagged until it landed in the visitors’ bullpen, it dawned on those of us fortunate enough to be in attendance what we just saw. We saw seven seasons of Alonso culminate where we projected he’d land as soon as we got a load of what he could do as a rookie. We saw the Straw Man wave him into the top spot on the Met home run chart. Darryl hit career home run No. 155 on May 3, 1988, to take the all-time Met lead from Dave Kingman. It was noteworthy, to be sure, but the lead story from Shea that evening was David Cone making his first start of the year and bulling his way into the rotation to stay, shutting out the Braves (them again), 8-0. Pitching was the theme of that night. Pitching was often the theme while Darryl was adding 97 more home runs to his record between 1988 and 1990. Pitching has been the theme of the Mets most of their life. Darryl’s 252nd home run, off Greg Maddux of the Cubs on September 23, 1990, supported eight winning innings from Dwight Gooden. When you’re hitting home runs and your pitchers are the likes of Cone building a 20-win season and Gooden heading for 19-7, your home runs are only part of the story.

True for 37 seasons, not so much any longer. Pete Alonso won the Rookie of the Year award in 2019, the same year Jacob deGrom earned his second consecutive Cy Young. From there, it seems the paths of Met hitters and Met pitchers have diverged. Pitching is something we never have enough of in the 2020s. Hitting (recent trends notwithstanding) is more the Met signature in this generation. It is, after all, the Polar Generation. Drink it in, drink it in, drink it in.

That we did. Pete choosing the second Tuesday in August at home to whack his record-breaker and record-extender was thoughtful, considering that more or less every second Tuesday in August at home is the date the Princes make to meet up with our favorite father-and-son combo, Rob and Ryder Chasin. We first met the Chasins when Ryder was thirteen (it’s a whole story). We went to our first game with them when Ryder was on the verge of turning fourteen. Ryder will soon be twenty-nine. Along with the sustained excellence of Pete Alonso, the Chasin Game at almost precisely the same juncture every August is, certainly to me, Citi Field’s greatest ongoing success story.

We shared Pete and the new power generation’s success with more than 39,000 this Tuesday night. The Mets reminded us why we willingly flock to see them. They can’t always promise history, let alone victory. But when they deliver, man, just keep playing that groove.

And when you need to sit out a set, hustle on over to your podcast provider of choice and take in the 200th episode of Jeff Hysen’s National League Town, to which I returned to sit in for a spell this week, because who can resist being on hand for a milestone?

by Greg Prince on 10 August 2025 6:27 pm Although the architecture for this blog indicates it remains dedicated to the New York Mets, we have changed the format for today to a blog dedicated to our new favorite team, the Milwaukee Brewers. See, we don’t wish to think about the Mets any longer, but we don’t mind thinking about some other baseball team, particularly a real good baseball team. Thus, you can now think of this site as Millie Helper, Millie, as in our affectionate name for Milwaukee, and Helper, as in we’d like to help our new favorite team get as far as they can. (And, yes, Millie Helper was a character on The Dick Van Dyke Show, portrayed by actress Ann Morgan Guilbert, an alumna of Solomon Juneau High School in Milwaukee, a fact we’re sure all Brewers fans like us already knew.)

Today, we are all Millie — that’s short for Milwaukee — helpers. Good news, fellow Millie Helpers — we won on Sunday! Is that news? Don’t our Brewers always win? Sure seems like it, especially when we take on those Mets. Wow, those Mets, huh? Seems like not so long ago the Mets were a problem for us, specifically last October, but that was last year, and now they’re really quite the welcome sight on our schedule, or I suppose, the schedule of any team’s fans. Maybe not that of Mets fans, but they’d have to speak to that issue.

The Mets led in the series finale, 5-0, and if you hadn’t been watching the Brewers much, you might have thought a five-run deficit would be daunting. But not for our Millie! Our Brewers chopped and chipped away at that New York lead, and before you knew it, we were tied, 6-6. This was with our starting pitcher, Quinn Priester, lasting only four-and-a-third. Quinn gave up two home runs, one to Brett Baty, who I understand was once a top Met prospect, and one to Cedric Mullins, who hadn’t hit much since the Mets acquired him from Baltimore. Of course Quinn could relate to the Mets starter, Sean Manaea. Manaea went only four-plus innings, which is about what most Met starters top out at. Or so I think I read on the screen during Sunday’s game. I watched the Mets feed, and their announcers mentioned two things repeatedly:

1) Their starters, except for David Peterson, never last.

2) Our team, the Brewers, is really impressive.

I could have told them the second part.

Anyway, Quinn didn’t have it, but you know our Brew Crew, never out of it until we’re out of it, and against the Mets, we were never out of it during this entire series. There we were in the fourth, getting on the board via a William Contreras leadoff home run, the poke that clued us in that this would be like any other day that ends in y, a day where coming up with a way to beat the Mets was inevitable. Later in the same inning, Joey Ortiz — we call him Pal Joey — singled to left to bring in two more runs. We were trailing the Mets by two, but you knew it was only a matter of time.

The bullpens eventually took over, and I know I saw something about the Mets beefing up their pen (sort of like we Brewers fans beef up our tailgates when we’re not grilling brats), but Met pens seem to run out of ink no matter who’s in them. Witness the uncapping of Reed Garrett who gave up Contreras’s second homer of the day, this one with a man on. We couldn’t get to Brooks Raley or Tyler Rogers, but sure enough, come the eighth inning, when we were down, 6-5, we built a rally versus Ryan Helsley, who I have to admit I’m having a hard time not thinking of as a Cardinal, what with our frame of reference being the National League Central. Funny thing, I was watching the Mets’ postgame show on Saturday night (know thy enemy and all that), and a reporter asked Helsley to comment on Pete Alonso tying their franchise record for home runs, and I was thinking, why would Helsley have an opinion on that? Ask him about Stan Musial.

But I digress. Helsley came in and, before you knew it, our Brewers had a scoring threat that culminated in Pal Joey singling in the tying run. I’m not one for those constant gambling come-ons that have infiltrated baseball broadcasts, but I thought, man, I have to put down my brat and place a bet, because I know our Brewers are gonna win, whether it’s in the eighth, or ninth, or tenth.

As a fine, upstanding fan of a Midwestern-based baseball team, I try to think only positive thoughts, but when the bottom of the ninth began, the game still tied at six, I envisioned the game ending with a shot of Edwin Diaz walking forlornly off the mound. I mean I planned on enjoying however we won the game, but you didn’t have to be a Mets fan to have known that was coming. Diaz is a great closer, but he hasn’t closed anything since I don’t know when, because the Mets never take any leads into the ninth. I’ll bet even his jars of mustard are open for when he grills (that’s a little Midwestern tailgating humor there, of course). Unsurprisingly, one of our many fine Brewers, Isaac Collins, took Diaz over the right field fence, not far from where Pete Alonso did that thing last October that we don’t think about as Brewers fans anymore, because we’ve moved on from 2024. The final was our Millie Brewers 7, those New York Mets 6.

I really should have placed that bet. I knew it would come out like that. That’s what life as fan who doesn’t root for a team that has wrapped itself in predictable doom is like. I don’t have to tell you that if you love the Brewers the way we love the Brewers here at Millie Helper, but in case there are still any Mets fans reading, I thought you might like to know that baseball still has the ability to fill some people with joy these days.

by Jason Fry on 9 August 2025 10:48 pm The Mets were playing the Brewers Saturday night.

I had recap.

I went to see “Superman” with my family — a movie I’d already seen.

I did that because I’d reached the point where I can’t stand this team, which right now combines a deep-rooted cruddiness with a magnetic attraction to disaster. Knowing they’ll find a way to lose and wondering how they’ll do it was starting to infect the rest of my day, and two hours of the determined optimism and indefatigable sunniness of James Gunn’s “Superman” felt like exactly what I needed.

Which it was! We walked out of the theater and for a minute or so I completely forgot the Mets were playing.

And then I remembered and we turned on the MLB Audio feed for the drive home. The Mets were up 4-3 in the bottom of the seventh, with Ryne Stanek on the hill, nobody out and a runner on first.

Yes, that’s when I tuned in — sometimes the jokes really do write themselves.

You know what happened next — or if you don’t, you’re better off and I’d strongly advise you to stop reading now.

Lineout to shortstop. Ball off the right-field chalk that bounced into the stands, sending runners to second and third. A grounder to shortstop where Stanek got in the way of Francisco Lindor‘s throw home, forcing Lindor to take the out at first as the tying run scored. Enter Ryan Helsley, who got a grounder to Ronny Mauricio, who muffed an in-between hop to give the Brewers the lead. Helsley got William Contreras to line out to Juan Soto — only, incredibly, to have the out nullified on a pitch-clock violation. Contreras then clobbered Helsley’s next pitch into the stands, and the Mets were dead.

As a friend noted on Bluesky, I should have seen a double feature.

(Yeah, Pete Alonso tied Darryl Strawberry‘s franchise home-run record. Don’t really care right now.)

Going to the movies was a smart move. Returning to the reality of the Mets was a deeply dumb one, a lesson they rubbed my face in by giving me the so-far worst 10 minutes of a rapidly decaying season.

Honestly, I should find a movie to see Sunday. Why should I watch this team? Why should you? Why should anybody?

The Mets’ vaunted lineup hasn’t hit in weeks (they struck out 12 more times Saturday night), and the response of David Stearns isn’t to fire coaches whose failure is statistically obvious but to serve up happy talk about a process that pretty self-evidently isn’t working.

But it’s not just the nonexistent offense that’s gone rotten. The defense has collapsed (particularly Lindor, who’s having an inexplicably horrible year), there’s only one reliable starter, the newly acquired relievers have mostly been terrible and the previously employed ones have been taxed beyond their capabilities. If there’s a way to lose, these current Mets will find it — whether early and limply or late and tragically.

There’s no urgency and worse than that, there’s no accountability — which sure isn’t something I expected from a business run by Steve Cohen.

Until there is, why give this team any of your time?

by Greg Prince on 9 August 2025 10:54 am Starling Marte got a good lead off second, had a good jump as soon as Jeff McNeil singled into center, took a good route around third, sped home at a good rate, and made a good slide toward the plate. He did everything well on the two-out play intended to tie the Mets-Brewers game in the top of the ninth. He was out, anyway.

Such things happen in the course of a baseball season. Such things happen to end baseball games. Such things happen to teams of all stripe. That it’s all happening to the Mets right now is what makes the conclusion to Friday’s 3-2 loss in Milwaukee that much more vexing. The Mets totaled five hits. Two of them were solo home runs, one struck in the first inning by Juan Soto, the other blasted by Marte in the second. Two of them were the double and single strung together by Marte and McNeil in the ninth. In between, there was a McNeil single in the fourth and nothing more. McNeil in the fourth was erased on a double play.

The Mets outhit the Brewers, 5-4. But Brewer pitching, led by Brandon Woodruff for seven innings, struck out more batters while walking fewer of them. The only pitcher on either side to hit anybody was a Met, Brooks Raley. That came with the bases loaded in the fifth, after Brice Turang had socked a two-run homer that was set up by a Kodai Senga error, the only error made in the game. That shot had tied the score at two. After getting one out, Senga walked a batter, had one reach when catcher’s interference was called on Francisco Alvarez, and walked another batter. That was the bases-loaded situation Raley stepped into, the one that led to the HBP.

Throughout the game, there emerged slight edge after slight edge the Brewers had on the Mets. Another “such things happen” situation, perhaps, but haven’t we been seeing this versus the Padres, the Giants, and the Guardians? Look what the opponents brought to bear. Tighter fielding. Clutcher pitching. A home run hit with a runner on base. A bases-loaded opportunity taken advantage of just by letting the Mets hand it to them. Such things keep happening.

Senga was OK for four innings, didn’t last the fifth. Woodruff looked like the ace we thought Senga was. Our bullpen, despite Raley’s one pitch that hit dinged Isaac Collins in the foot at the worst possible juncture, was sufficiently sound. Ryne Stanek, Gregory Soto, and Tyler Rogers were fine (and hopefully don’t become unavailable the rest of the weekend for having been used once). They kept the deficit at one run. So did the Met offense. The composite of three hits in the first eight-and-two-thirds-innings left lots of white space the Mets never filled. Strikeouts. Groundouts. Flyouts. Uninterrupted futility. Hitters who didn’t exactly jog to first, but they sure as hell didn’t sprint. The Met lineup seems to have subscribed to the notion that nothing is going to happen, so why pretend they can make something out of nothing?

Yet there they were in the ninth, Marte delivering his second extra-base hit and McNeil singling for the second time. Starling was ready to run. He can still do that. Maybe Tyrone Taylor — the capable pinch-runner trepidatiously held up at third on Monday — could have gotten a better lead, a better jump, and been a better bet, but I saw nothing that indicated Starling was physically compromised (and do you really want Taylor as your DH should the game find itself in an eleventh inning?). McNeil came through, Marte executed, and Mike Sarbaugh had no reason to put up a stop sign. In the end, the Brewers had one more slight edge on the Mets. Blake Perkins made an excellent throw, William Contreras caught it where he needed to be, and he tagged Marte out. The Mets challenged, perhaps for the first time all night in any sense of the word, and they were rebuffed. The Brewers won one of those one-run games that didn’t feel quite so close.

The Mets have lost five in row, nine out of ten. Everything feels like it’s the reason. Senga’s gotta go longer. Taylor coulda been in there. Acuña oughta be up here (he oughta, actually). Mistakes have to be minimized. Catcher’s interference? Yeesh, absolutely, but there was one Met hit from none out in the top of the second to two out in the top of the ninth. Some nights, like the night of the third game of last year’s Wild Card Series in the very same ballpark, you can wait until the ninth inning to pull out all the stops, but that was a special occasion in a special year. There’s nothing special going on here now.

Not so fab of late. Try something. My possibly goofy suggestion is take the so-called Fab Four, whose golden slumbers atop the lineup are weighing down the offense as a whole, and break them up for a spell. Shuffle the deck. Bat one of them second, one of them fourth, one of them sixth, and one of them eighth. Or first, third, fifth, and seventh. I don’t care which Met you put where at this point. I know Lindor, Soto, Alonso, and Nimmo are far better than they’ve shown, but I swear they’re infecting each other with their contiguous mediocrity, and the effect on everybody else is that of a superspreader. Let a couple of them bat where the pressure feels lighter. Maybe they’ll rediscover the approach that made them stars. Maybe the opposing pitcher will be flummoxed that he has to face a repuational big bat every other spot. Simultaneously, move Mullins, who isn’t getting anything done wherever he’s batted, to the top of the order. Or Mauricio. Or McNeil. Or whoever. Anything for one or two games. Whatever they’re doing and continue to do clearly isn’t working. It ain’t Panic City if constancy for constancy’s sake is stranding you in Also-Ran Village.

The Mets continue to hold a playoff spot because they played very well for a while in this very same season. Both facts are hard to believe based on what we’ve been watching for the bulk of nearly two months. It’s hard to believe they will play very well again in this season and it’s almost laughable to anticipate them participating in the upcoming postseason. The tenor of laughs can certainly change from early August onward. Can you believe we ever doubted the 2025 Mets? HA on us! But not at this rate. Try something. Try almost anything. To not change up some aspect of the Mets while they wither is most trying of all.

by Greg Prince on 6 August 2025 5:22 pm I greeted Juan Soto’s bottom-of-the-ninth solo home run with more enthusiasm than Juan Soto greets extra-base hits he has to gather and fire back into the infield, which is to say with minimal enthusiasm. Until he ended Gavin Williams’s no-hit bid Wednesday afternoon, I’d allowed myself to almost root for the no-hitter to happen. Almost. Once it wasn’t going to happen, well, good — the Mets just scored a run to cut the Guardians’ lead to 4-1 and maybe they’ll get a couple of runners on, bring the tying run up, and remind us of who they are or at least who they seemed to be not that long ago.

They didn’t do any of that, but at least they didn’t get no-hit. Spiritually, they’ve been no-hit for the last week-plus. Statistically they’ve gotten hits. The hits haven’t much mattered. The Mets are playing like nothing matters, and what if it did? I thought they were a special team when the season started and progressed, even when it ran into rough spots. Now I wait for these players to coalesce into something resembling cohesion. They’ve come together of late mostly to not get base hits in unison.

A tip of the hat need be directed toward the opposing pitcher. Permitted to remain on the mound and chase history, Williams retired a major league lineup over and over without allowing a hit across eight-and-a-third. I know the Mets constitute a major league lineup because I’ve seen the Major League Baseball logo stitched onto the backs of their caps and jerseys. That’s the only clue I have.

Watching a no-hitter would have been novel. A dreary loss was more same old squared. The Mets have lost eight of nine. They’ve tried astoundingly frustrating. They’re tried deadly dull. Might as well mix it up with a game that pops, even if it pops for the wrong team. Then again, the Mets simply winning would be novel. Maybe they’ll try that in Milwaukee.

by Jason Fry on 5 August 2025 10:35 pm The Mets have sunk from amazing to confounding to unwatchable.

Tuesday night’s one-run loss to the Guardians showcased everything about this team right now that no one sensible would put in a showcase: one bad inning from a starting pitcher who (once again) didn’t give his team much length, a bit of ill-timed bad luck, and an absolutely inert offense. The Mets scored their first run of the game without a hit, which feels like the punchline to a joke, their second run on a single, and that was the sum total of the scoring. In fact, Jeff McNeil‘s leadoff single in the fourth was their final hit of the night, with the last 14 Mets making outs without so much as a whimper.

The Guardians, for their part, took the lead in the seventh on a mildly absurd trio of two-out hits against Tyler Rogers: a grounder that bounced through the 5.5 hole into left, a little poke job over the infield on a pitch 18 inches outside, and finally a disgustingly Sojo-esque seeing-eye single up the middle.

After all that, Jeremy Hefner strolled out to the pitcher’s mound to talk to Rogers; we were in the car and wondered what a pitching coach possibly says in that situation.

“Hang with ’em?”

“Keep doing what you’re doing?”

But then Emily nailed it: “Sorry that you’re now on the Mets.”

by Greg Prince on 5 August 2025 11:53 am Third base coaches’ names rarely come up in spaces like these unless one finds fault with a third base coach’s decision or execution on a pivotal play.

The Mets’ third base coach’s name is Mike Sarbaugh.

I don’t think I’ve ever brought it up here before despite Mike having been the Mets third base coach these past two seasons, one of which extended into the playoffs, another of which is — despite recent trends — poised to do so again.

Ignoring Mike Sarbaugh until something goes wrong is probably not fair.

Here’s why I and no doubt you noticed Mike Sarbaugh Monday night.

Mike Sarbaugh should have sent Tyrone Taylor.

You know what I’m talking about.

Carlos Santana dropped the relay throw.

You know which relay throw I’m talking about.

Taylor was around third when it was dropped.

Sarbaugh has to make a snap decision based on the best available evidence.

The best available evidence to Sarbaugh was a relay throw had been made cleanly by Nolan Jones.

But Taylor was in there Monday night in the bottom of the ninth in a tie game as a pinch-runner, somebody who can score from first on a double to deep right.

Francisco Lindor doubled to deep right.

Taylor took off with every apparent intention of getting as far as he could.

He could have gotten home.

He could have won the game right then and there.

The game was 5-5.

The Mets had been behind, 5-0.

Sean Manaea had pitched beautifully through five before imploding in the sixth.

The Mets came back.

Pete Alonso hit his 251st career home run, putting him one behind Darryl Strawberry, a three-run job that got us on the board in the sixth.

Alonso was part of another rally, driving in one of two Met runs in the eighth.

Our bullpen didn’t do anything appreciably wrong for four-and-two-thirds.

Our defense was unforgivably sloppy.

But theirs was no great shakes, either.

It may or may not be fair to say Monday night’s 7-6 loss in ten innings to Cleveland at Citi Field came down to Sarbaugh holding up Taylor.

I understand what the third base coach saw.

I understand Juan Soto was up next with one out, and runners would be on second and third for him.

I understand that once Soto was intentionally passed (a predictable decision by the Guardians), the bases would be loaded for Alonso, he of the 4-for-4, 4 RBI night.

I understand that if Pete hits a bases-loaded fly ball with one out, Taylor trots home with the winning run.

I also understand that this team needs to grab chances when they appear.

Taylor rounding third was a chance.

Santana dropping the relay throw from Jones was a bigger chance.

The Mets took no chance.

Alonso struck out.

Jeff McNeil lined out.

We went to the ghost-running tenth, where Ryan Helsley pitched fine, but plays were not made on his behalf, and there, essentially, went the rest of the ballgame.

Sarbaugh should have sent Taylor.

Some night when the Mets win because Sarbaugh stopped a runner, I hope I remember to acknowledge the third base coach’s contribution.

It’s only fair.

Just as it’s fair enough to say his stop sign Monday night helped doom the Mets to their sixth loss in seven games.

Goodness knows they didn’t need any more help like that.

by Jason Fry on 4 August 2025 8:12 am I suppose I could take care of Sunday’s game by writing Saturday’s post backwards: The Mets zoomed from amazing back to confounding, the offense was crummy, they wound up way behind before the merciful conclusion, and a few hours later the Phillies kicked them out of first place. And all this against the Giants, who fooled people with some early-season eyewash before reverting to being a fundamentally unsound team that can’t play defense and sometimes appears less than interested in the other aspects of baseball.

The highlights? Francisco Lindor hit a home run in the brief pre-debacle part of the game. Austin Warren pitched effectively in bulk relief, for which he’ll undoubtedly be rewarded with a bunch of HR paperwork. Luis Torrens didn’t give up a run, which Ryne Stanek sure can’t say. With the Mets down to a last out in a foregone conclusion, Mark Vientos and Francisco Alvarez didn’t give away ABs and put two runs’ worth of lipstick on the pig.

It’s not a lot to celebrate.

David Stearns has had a pretty good eye for reclamation projects, but it’s getting late for Frankie Montas to add his name to that list. Listening to Montas miss locations and turn his head to watch balls head up gaps and over walls, I kept thinking to myself that it might be time for the Mets to choose an alternate strategy, the exact details of which are to be filled in but which can be broadly summed up as Not Frankie Montas.

The Mets have talked up Nolan McLean and Brandon Sproat, both of whom stayed at the trade deadline and are increasingly looking like the lessons they need to learn can only be learned against big-league hitters. Surely a C- with some encouraging teacher comments for McLean or Sproat would be better than another F or D- hitting the desk for Montas. (Speaking of teacher comments, let’s just say Carlos Mendoza‘s postgame review of Montas didn’t drip encouragement: “He has to be better.”)

One other thing did stand out as praiseworthy from Sunday’s game: We were listening to the radio feed, and Howie Rose noted it was the 21st anniversary of Bob Murphy’s death. Howie spent the better part of an inning reminiscing about the father of Mets radio, and he was warm and wise, offering an affectionate look at the past that never strayed into grousing about the present. He also talked movingly about Murph’s last years, not sugarcoating the sadness of watching a great broadcaster in decline. Howie praised Murph’s ability to stay optimistic even during a game that was a lost cause, giving Mets fans something to think about and enjoy; he gave his mentor the best possible honor by doing the same.

by Jason Fry on 3 August 2025 10:17 am Emily and I spent Saturday getting to the summer house in Maine and starting to return it to a vague state of habitability, so the Mets and their adventures were less the centerpiece of Saturday’s doings and more of an accent, followed in spurts and snatches as other things transpired.

Those brief looks, however, revealed the Mets to be as confounding as they’ve been all season. They were ahead, they were not ahead but also not behind, they were behind, they were ahead, they were way ahead. It was relaxing near the end, when their way aheadness reached a level where only, say, a recent vintage Pirates fan needed to worry. Before that, though? Brows were furrowed, as threatens to be their default brow position.

Kodai Senga was not great, and hasn’t been great since returning from the IL. Senga, for all his talent, is something of a Ferrari: sublime when running in tip-top shape, but all too often in the shop or in need of a mechanic’s attention.

As for the Mets’ Big Four, those occasionally roaring but also occasionally sputtering engines of offense, they did their jobs for the afternoon: Brandon Nimmo, Francisco Lindor, Pete Alonso and Juan Soto went 9 for 17 on the day, racking up 10 of the Mets’ 11 RBIs. Alonso was front and center, connecting for his 250th homer in the first off the Giants’ Kai-Wei Teng, who was making his first big league start.

Alonso is now three homers from passing Darryl Strawberry and claiming the franchise mark for his own; he also has 86 RBIs with two months of baseball to play. For all that, it’s been a strange year: The Polar Bear started off looking like a strike-zone light switch had gone on, with bait sliders and pitches best addressed with an oar no longer swung at, but that mental strike zone had ballooned of late, with a corresponding lack of success.

And he’s far from alone: Lindor keeps having a day or two where you think he’s out of the woods and returning to MVP form, only to plunge back into dark hitless forests; Nimmo has blown hot and cold as an offensive force; and Soto has been bizarrely ineffective in clutch situations and currently ineffective in any situation, which is little short of stunning for a player who’s been billed, not sardonically, as the “modern Ted Williams.”

For a day the offensive blueprint worked — aided, it should be said, by some slapstick Giants defense that culminated with poor Tristan Beck left out there to take a beating while his teammates averted their eyes from his plight. Tyler Rogers, the last of the Mets’ deadline acquisitions to suit up, made his debut against his old team; Rogers combined with Reed Garrett, Gregory Soto, Brooks Raley and Rico Garcia to build on the not much that Senga had given the Mets, with only Garcia scored upon and that coming in a situation when he was just trying to get the game over with.

David Stearns’ deadline strategy has been an interesting one, and to my eyes a logical one: The Mets simply aren’t going to get the consistent length from their starters that they’d hoped for, and weren’t willing to pay the prospect cost for fixing this problem on the trade market, so they opted to rent top-flight relief arms for the sixth and seventh innings. The river’s not getting narrower, so let’s build a big honking bridge, more or less.

It’s not a crazy strategy — we saw the Dodgers employ it against us, after all — and the prospect cost was mostly back of the pantry stuff. I’ll be curious, in a dispassionate baseball sense, to see if it works; I’ll be highly invested, in an insane Mets fan sense, to see if it works.

For a day it did; the Mets ended the day back in first place, having leapfrogged the Phillies yet again. Those two teams have seven left to play, and if you listen closely you can hear the war drums getting closer. Will the outcome, for us, be confounding? Amazing? Here’s betting on guaranteed portions of both.

by Greg Prince on 2 August 2025 2:16 pm They changed personnel. They changed locale. Their results didn’t much differ. The post-trade deadline New York Mets lost, 4-3, at Citi Field on Friday night to a San Francisco Giants team that looked familiar, and not just because they were who the Mets took on last weekend, the last time the Mets won a game. Wilmer Flores, who was a Met in the company of Dom Smith, who was a Met in the company of Joey Lucchesi, who was a Met in the company of Jose Butto, who was a Met until the other day, all represented the opposition. Perhaps it confused the players who were wearing Mets uniforms. The whole thing required ten innings to sort itself out. Smith drove in what proved the winning run. There was a time that would have been swell. There was a time the 2025 Mets were swell.

That time can return, you’d think. It’s still mostly the same guys who were in the midst of a seven-game winning streak a week ago. It’s still mostly the same guys who’ve occupied first place more than they haven’t. Not that they occupy first place at the moment, not after the Phillies won while the Mets were losing their fourth in a row. This is the Mets’ second four-game losing streak since they lost seven consecutive in the middle of June. There was also a three-game losing streak in there somewhere. These are not the trends one associates with a first-place team.

To regain the momentum that elevated them to/near the top of their division, the Mets got busy as the deadline approached. We’ve now seen two of the three relievers recently obtained in action, Gregory Soto twice on the West Coast (once for better, once not so much), Ryan Helsley Friday night at home. Helsley is accompanied by a hellacious entrance music and light show, though once you’ve enjoyed your incumbent closer’s entrance music and light show, all you really want to see are outs recorded without fanfare. Helsley rang those bells successfully, striking out three batters in the ninth to keep tied a game that the Mets had just evened, the same one Edwin Diaz would lose, despite all those trumpets. The new late-innings specialist gave up no runs, so that was a small victory within the larger defeat. Tyler Rogers has yet to pitch, so we’ll wait on appraising his first tiny sample size and whatever flourishes soundtrack his appearances.

We also traded for a center fielder at the deadline, Cedric Mulllns, late of the Baltimore Orioles. I want to call him Moon Mullins, because I’m pretty old, but his sanctioned nickname, per Baseball-Reference, is The Entertainer, which makes more modern sense. Cedric didn’t get much of an opportunity to entertain his new audience Friday. He pinch-hit with two out in the bottom of the ninth to no great effect, and was not moved along meaningfully by his new teammates when he returned to the basepaths as the Mets’ unearned runner in the bottom of the tenth. In between, he played an inning in center field, notable because, man, do the Mets need a center fielder, specifically one who can hit.

They didn’t need to find a new center fielder to play center field. They’ve had themselves a fine one all along. Center field has been well covered this year primarily by Tyrone Taylor. The 70% of the earth being covered by water equation disseminated by Ralph Kiner on behalf of Garry Maddox pretty much applies to how Tyrone gets around out there. If David Peterson is an ironman in this age when our mouths hang agape for solid six-inning starts, Taylor is a veritable Gold Glover for tracking almost everything down when he plays. Of course he doesn’t play as often as a regular might because somebody’s gotta hit. Taylor in 2025 has been a center fielder who has barely done a lick of that.

Listen, somebody’s gotta hit from every position within the Mets’ lineup. Friday night, we got a little hitting from Pete Alonso, including his twenty-third home run, which put the Mets on the board when they’d trailed, 3-0, and the deep fly ball that caught the Mets all the way up to 3-3; a little hitting from Juan Soto, when a ball he grounded up the middle caromed off the mound and became an essential eighth-inning RBI; and a little hitting from Francisco Lindor, who preceded Soto’s somewhat lucky shot (Juan’s hit into enough hard outs) with the single that helped build the Mets’ second run. A little hitting from the Mets’ Biggest Three is more than they’d been receiving in San Diego. A little hitting isn’t going to do it.

A little hitting would look fantastic from Taylor. A lineup featuring three slugging stars and a strong second line of support, should be able to carry a glove-first, bat-last fella. Tyrone, who might hit ninth if the pitchers still swung, has taken the defense dispensation to extremes. On June 21, Taylor contributed two hits to the Mets’ 11-4 romp in Philadelphia. Since then, across 28 games, he’s collected six hits in 67 at-bats. In the parlance of trying to get off the Interstate, Tyrone’s been stuck on a state road since summer kicked in.

That, along with the Mets’ effort to fit all their slight irregular square pegs into reconfigured round holes, helps explain why he’s shared much of the available center field playing time with Jeff McNeil, who’s not a center fielder but does get hits. Jeff’s played center well enough. Jeff’s played it like he plays it like he plays every position, by scowling it into submission. You’d rather have McNeil at second base, even if that means you won’t have Brett Baty at second, which you may or not want, anyway, but you would like to get Baty in there somewhere without having to sit Ronny Mauricio, who’s more or less the third baseman now, if it’s not Baty or Mark Vientos, who’s probably the DH, except when it’s Starling Marte.

In the literal middle of all this, welcome Mullins, the new lefty-swinging center fielder, complementing righty Taylor, if we’re being kind. Cedric had one truly excellent season as an Oriole, then one somewhat less excellent, then a couple that got progressively more unimpressive. I don’t want to say “worse,” because I’m trying to stay positive. He’d been hitting well before getting traded, and he can make the plays in center. Maybe that’s enough to make a significant difference for the Mets. Or maybe we’re gonna get lifted by the players we expect to do the heavy lifting, and anything we get out of Cedric will constitute a small but vital boost.

Acquiring Mullins got me to contemplating Met center fielders through time as a species and it occurred to me that almost never is a Met center fielder the player who is front and, well, center for this franchise. We’ve had some splendid ones, a couple who could do it all, more than a few who could some things wonderfully, but in a sport not to mention a city where center fielders have been eternally romanticized, have the Mets ever been “led” by theirs?

A little, maybe. Join me on a selectively crafted and not necessarily thorough 410-foot trip to center, from our beginnings to right now. If the apple of your eye or bane of your existence isn’t explicitly shouted out, you can trust that their names at least flitted through my consciousness amidst this exercise.

Richie Ashburn, a Hall of Fame center fielder, was our first All-Star and perhaps spiritual leader, but he played a lot of right in 1962 before retiring.

Jim Hickman has a claim on most accomplished player in the portion of Mets history that ended prior to 1969, however faint that praise lands, but he also got moved around quite a bit (and, in real time, wasn’t considered someone making the most of his potential).

Cleon Jones became a regular in the majors as the Mets’ primary center fielder in 1966. His marvelous Met future awaited in left.

Don Bosch was, in 1967, going to give the Mets the true center fielder they’d lacked from their inception. He didn’t.

Tommie Agee broke out for two seasons of sensational production from every angle of the game in 1969 and 1970, and that alone is worthy of his place in the Mets Hall of Fame. Honestly, Game Three of the 1969 World Series should have certified his induction. But the Tom who led the Mets in Agee’s day didn’t play center.

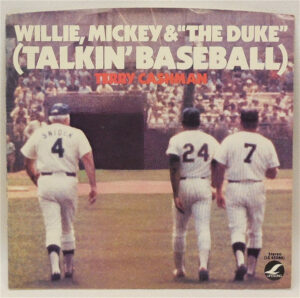

Willie Mays, perhaps the most romanticized of any center fielder anywhere ever — I can think of five songs of the top of my head that mention him prominently — is Willie Mays, and for 95 games, he was center fielder for the New York Mets. I never tire of peering up at No. 24 in the Citi Field rafters and warming all over. But he wasn’t brought back to town after fifteen years to play center field. He was brought back to be Willie Mays. Willie Mays, perhaps the most romanticized of any center fielder anywhere ever — I can think of five songs of the top of my head that mention him prominently — is Willie Mays, and for 95 games, he was center fielder for the New York Mets. I never tire of peering up at No. 24 in the Citi Field rafters and warming all over. But he wasn’t brought back to town after fifteen years to play center field. He was brought back to be Willie Mays.

Don Hahn: Nice defense. Pennant-winner. Didn’t hit. Got traded for Del Unser. Don Hahn: Nice defense. Pennant-winner. Didn’t hit. Got traded for Del Unser.

Del Unser, who benefits from his one full Met season coinciding with the year I was twelve, was an outstanding player for us in 1975. But even I who adored Del Unser as I stood wobbly on the precipice of adolescence didn’t look at a team that featured Seaver, Matlack, Koosman, Kingman, Staub, and Millan, and think, “here come Del Unser and the Mets!” (And there went Del Unser from the Mets in 1976.) Del Unser, who benefits from his one full Met season coinciding with the year I was twelve, was an outstanding player for us in 1975. But even I who adored Del Unser as I stood wobbly on the precipice of adolescence didn’t look at a team that featured Seaver, Matlack, Koosman, Kingman, Staub, and Millan, and think, “here come Del Unser and the Mets!” (And there went Del Unser from the Mets in 1976.)

Lee Mazzilli…now we’re talking about a center fielder who led the Mets. In 1979 and 1980, he was the heir to Willie, Mickey & The Duke, not to mention Joe D. He was talented, he was glamorous, and he could do everything very well if you didn’t count throwing. He also got moved to first base before being moved out of Queens altogether. Still, there was a genuine period when if you we’re going to see the Mets, you were going to see Lee Mazzilli and the Mets. You were also probably going to see the Mets lose, but let’s not pin that on Lee. Lee Mazzilli…now we’re talking about a center fielder who led the Mets. In 1979 and 1980, he was the heir to Willie, Mickey & The Duke, not to mention Joe D. He was talented, he was glamorous, and he could do everything very well if you didn’t count throwing. He also got moved to first base before being moved out of Queens altogether. Still, there was a genuine period when if you we’re going to see the Mets, you were going to see Lee Mazzilli and the Mets. You were also probably going to see the Mets lose, but let’s not pin that on Lee.

Mookie Wilson wasn’t a natural leadoff hitter, but he did lead off the rebuilding of the Mets when he arrived in 1980. You could legitimately say the Mets built a championship club around him, promoting and adding piece after piece until it was 1986. Mookie may have been the heart of those teams. We know he was their feet when it mattered most. He wasn’t their face, regardless of how much you were ready to kiss it in the early hours of October 26, 1986. Mookie Wilson wasn’t a natural leadoff hitter, but he did lead off the rebuilding of the Mets when he arrived in 1980. You could legitimately say the Mets built a championship club around him, promoting and adding piece after piece until it was 1986. Mookie may have been the heart of those teams. We know he was their feet when it mattered most. He wasn’t their face, regardless of how much you were ready to kiss it in the early hours of October 26, 1986.

Lenny Dykstra gnawed into Mookie’s playing time, turning Wilson into a part-time left fielder. From 1985, though the platoon he forged with Mookie to win a World Series, to the Sunday afternoon in 1989 he was sent from the visitors’ to the home clubhouse at Veterans Stadium, Nails could be really nails. Never quite made the case to be a regular in New York, though. Philly was a different story, as have been as his post-playing let’s call them adventures.

Lance Johnson (doing some skipping over some short-term solutions and lesser ideas) was a dynamo in 1996. Led our league in hits (227) and triples (21). Still owns both single-season Met records. Probably always will. Stole fifty bases. With Todd Hundley and Bernard Gilkey, stood as the reason to keep watching a furshlugginer ballclub. Traded in 1997.

Brian McRae was who we got for Lance Johnson, and who we’d trade for Darryl Hamilton.

Darryl Hamilton delivered one huge base hit in the 2000 postseason. Sometimes one huge base hit is all you need.

Jay Payton had already usurped center field from Hamilton and the others who’d had their turn-of-the-millennium moments as 2000 grew successful. Big prospect. Long career. Didn’t really and truly click as a Met except in spots. Certainly didn’t last as a Met.

Mike Cameron put together a quietly gaudy season in 2004. Thirty home runs. Twenty-one steals. Exciting defense, which is to say he liked to play shallow but usually caught up to balls. With Cliff Floyd, installed “The Way You Move” by Outkast as that season’s “L.A. Woman,” not that that’s much remembered, because 2004 wasn’t 1999. And Cameron wasn’t long for center field.

Carlos Beltran…he’s Carlos Beltran. He meant a lot of things to the Mets as soon as he signed for seven years in 2005, beginning with ending Mike Cameron’s tenure in center field, and ending with beginning Zack Wheeler’s affiliation in Flushing. As good an everyday player as we’ve ever had. Our all-time center fielder by consensus. Faith and Fear’s Most Valuable Met for 2006, when he had a lot of competition. Gold Glove. Silver Slugger. Many-time All-Star. Got what we paid for. And yet, can’t be called THE Met of his time, not when David Wright and Jose Reyes were the marquee attractions at Shea Stadium and Citi Field. Not that Wright and Reyes would have starred on contending clubs without Beltran doing his share alongside them. The marquee between 2005 and 2011 no doubt implied “and featuring…” for Beltran. Definitely played a huge role in his his era, never quite the defining character of his era. That’s not a knock. It’s relevant only to the notion of the Mets rarely being unquestionably led by their center fielder, whoever their center fielder has been. If it didn’t happen when Carlos Beltran was their center fielder, maybe it’s not fair to expect it to have happened ever.

But it did happen on other teams in the prime of Mays and Mantle and DiMaggio and Trout and Griffey and Dale Murphy, to name a handful of immortals; we’ll omit Pete Crow-Armstrong for the sake of our sanity. It’s not like those center fielders are garden-variety, so perhaps the bar is raised too high. If the Mets could be getting Carlos Beltran-level production in center field today, boy would we take it. We’d take the best of Angel Pagan, which we had for approximately a year (he was here longer); or the best of Juan Lagares, which we had for approximately a year (he was here longer, too); or the best of Brandon Nimmo (who delivered it in center in more years than one, but age shifted him to left). In 2024, we got by with Tyrone Taylor and Harrison Bader, two guys who surely had their ups and downs hitting but caught what needed to be caught, and you almost didn’t notice that they didn’t necessarily hit what needed to be hit. This year, with a powerful enough cast to theoretically excuse a hole in the bottom of the lineup, the top of the lineup has become too hollow to excuse anything.

Center fielder Tyrone Taylor, meet center fielder Cedric Mullins. Neither of you has to be Willie Mays from when he was really the Say Hey Kid. Two or three months making like vintage Mookstra would suffice.

|

|