Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

The biggest moment in Mets history is also one of the quietest. You’ve seen it: With two outs in the ninth of Game 5 of the 1969 World Series, Davey Johnson hits a fly ball to left. At first the ball looks like it has the distance to be trouble, but the peril is illusory. Its momentum dies in the cool air of October and gravity pulls it down, to where Cleon Jones is waiting at the edge of the warning track. He catches it with two hands, almost gingerly, and then both his glove and his knee come down, until his knee brushes the dirt and his hands are clasped — as if in prayer, or benediction, or a little of both.

The celebration begins — Jerry Koosman jacknifed in Jerry Grote‘s arms while Ed Charles dances happily alongside, fans pouring onto the field, Jones and Tommie Agee seeking safety in the visitors’ bullpen — but first there’s a moment of stillness, of hush. That moment’s simultaneously gone in a blink and seems to linger, to draw in everything that led up to it.

Which was quite a lot — for the franchise, for those who knew its tragicomic and star-crossed history, but also for the author of that quietly moving and strangely elastic moment. Cleon Jones arrived during one ignominious era of Mets history and departed during another, and was treated unfairly coming and going. In between, he won a World Series and a pennant, ascended to the top of the team’s record books, and forged what should have been an enduring legacy. And he did it facing obstacles few of us can imagine.

Jones made his debut at the end of 1963, as the Polo Grounds neared its demise. He was barely 21 and wrapping up his first year of pro ball, having played in the low minors in Raleigh, N.C., and Auburn, N.Y. Sizing up the Mets’ new outfielder, the beat writers found a shy young man who was sensitive about the deep scar that seamed one side of his face (left over from a car accident when he was a teenager) and spoke so softly he could barely be heard, when he spoke at all.

If that sounds like too much too soon, well, you don’t know the half. Jones would admit later that he was scared to death, plucked from his hometown of Mobile, Ala., and dropped into a world he had no idea how to navigate.

The Mobile of the early 1960s was the heart of the Jim Crow south, with Black and white lives kept rigidly apart. Stepping over those lines brought unease at minimum, with the threat of far worse. The threat of racial violence had shaped Jones’s childhood — he was raised by his grandmother because of an incident involving his parents that had happened when was a baby. Jones’ parents had been waiting in line for a bus when a white person in the line objected to being behind them. A yank on Jones’ mother’s hair caused his father to raise his fists. The Joneses fled north, aware of what might happen if they stayed. Jones’ mother died when he was 12, having never returned home. “I never saw my mother except in photographs,” her son recalled.

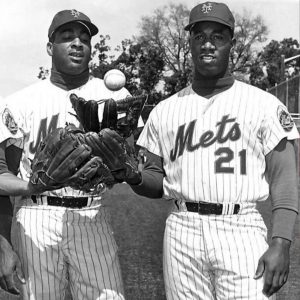

Jones wasn’t alone in having a childhood so shaped. His best friend in Mobile was Agee, who was five days younger than Jones and the other half of a formidable combination on the gridiron. While Jones’ family had been in Mobile since the 1850s, Agee had grown up in Magnolia, about two hours north. The Agees had hurriedly pulled up stakes after Tommie’s sisters fought with white children who lived nearby, causing their father to get his shotgun and threaten to kill his Black neighbors.

Black Mobile was an insular world defined by strict racial boundaries, but for those willing to stay within them, that little world had its pleasures — particularly if you were a young athlete. Jones threw right-handed but batted lefty, an oddity that was a product of the field where he’d played baseball as a kid: He hit so many balls into a creek that his friends refused to let him hit from his natural side. Mobile was fertile ground for Black baseball stars — besides Jones and Agee, its fields and lots produced the Aaron brothers, Satchel Paige, Willie McCovey, Billy Williams and Amos Otis. Jones and Agee, however, were best known as football stars. At Mobile County Training School, Jones was a running back and Agee a wide receiver for a team that lost just one game in three years. One of their favorite plays was an option where Jones would take the ball from the quarterback and hit Agee downfield. Agee and Jones took their show to Grambling, with Agee departing first, signing a baseball contract with the Indians in 1961. Jones transferred to Alabama A&M before signing on with the Mets in 1962.

Even in such a small world, Jones’ neighborhood of Plateau stood out. Plateau was known chiefly for the miasma from its paper mills, but it had another name: Africatown. For once, that wasn’t a disparaging nickname bestowed by whites. Africatown was settled by Blacks who’d arrived not generations earlier, but in 1860 aboard the Clotilda, the last slave ship to sail to America. The Clotilda survivors banded together after the Civil War, founding a town and pooling their money to return to Africa. That dream never came to pass, but they held onto their language and traditions — in Africatown’s cemetery, all graves faced east, towards their lost homeland. After his playing days were over, Jones returned home and built a brick house on the same lot where he’d grown up in a shotgun shack. “I can’t imagine being anywhere else,” he’d tell many a visitor.

In 1963, though, he was most definitely somewhere else. Jackie Robinson had blazed a trail for Black ballplayers, but the road to the big leagues remained a difficult one. In writing about Jones and Africatown, I’m indebted to Wayne Coffey’s terrific book from a few years back, They Said It Couldn’t Be Done. One of the best things about that book is that it doesn’t shy away from what Jones, Agee, Charles and Donn Clendenon faced on the way to getting their World Series rings — horrific racial abuse from fans, restaurants that wouldn’t serve them, having to board in gyms or decrepit housing, and much more besides. Young ballplayers still struggle when playing a supremely difficult game far from their families and friends; Jones and others in the post-Robinson generation had to do all that while dealing with searing daily reminders that they weren’t welcome playing the game they loved.

The Mets at least, knew that Jones wasn’t ready. He spent all of ’64 and most of ’65 in the minors before moving up to the big club for keeps in ’66 as part of the Mets’ vaunted, largely fruitless Youth of America. Jones’ talent was obvious — he provided both power and speed at the plate and was a superb defensive outfielder — but he was dogged by questions about his commitment and work ethic, and his shy, awkward manner made him a figure of fun in the press box.

But in 1968 — the year Jones represents in A Met for All Seasons — it all came together. After a slow start, Jones wound up hitting .297 with 29 doubles and 23 stolen bases, the latter mark breaking his own club record. Part of that was simple maturation, but he was also helped by two new arrivals to the Mets. The first was Gil Hodges, who mentored Jones where Wes Westrum had hectored him, and helped create a clubhouse remarkably free of the racial tensions and resentments of the era. The other was Agee, whose career had stalled with the White Sox but had been brought to New York on the new manager’s recommendation.

1968 went a lot better for Jones than it did for his boyhood friend — an anxious, discombobulated Agee hit just .217. In the offseason, Jones and Agee spent the afternoons fishing and talking hitting, then went out to take swings with Tommie Aaron. In 1969, that hard work would pay off. Jones finished third in the National League at .340, a Met record that would stand for nearly three decades. Agee rebounded too, hitting .271 with 26 homers. And, of course, they won the World Series, with the two Mets from Mobile at the center of much of that lore — and Jones giving us that indelible moment of quiet genuflection.

Besides securing the final out, Jones had a ringside seat for Agee’s two circus catches, though he insists neither surprised him: In both cases, he saw Agee pound his glove, something his buddy never did unless he was sure he’d make the catch. The famous shoe-polish play? That was Jones’ foot that the ball hit on its way to the Mets dugout and whatever might have happened between the time it rolled in there and when Hodges brought it out for Lou DiMuro’s inspection. (Coffey’s book has an answer, by the way.)

And then there’s Hodges’ long walk — the one part of the ’69 lore that’s been so thoroughly bent by the power of storytelling that it’s come to mean the opposite of what it actually did.

It happened at the end of July, on a soggy and decidedly less-than-miraculous day for the Mets: The Astros had beaten New York 16-3 in the first game of a double header, then scored six in the third inning of the nightcap, all with two out. Johnny Edwards doubled down the left-field line, with Jones pursuing the ball half-heartedly and throwing a little parachute back to the infield. Hodges came out of the dugout, walking with his usual deliberate pace, passed the mound and the infield, and kept going until he reached Jones. After a brief conversation, he turned and walked slowly back to the dugout, trailed by his .346-hitting star.

The incident would become part of the Hodges legend and proof of his steely reputation: The manager demanded his players give their all, no matter who they were or what the situation was, and embarrassing Cleon Jones was the proof of it. And Jones himself has burnished that legend over the years.

But it’s a profound misreading of the incident. The corollary to the story of Hodges’ long walk is that nearly every other story is about him handing out discipline quietly, either behind closed doors or by opting for a long stare and/or a few choice words. It’s Ron Swoboda calling Hodges out and then being unable to pee because he could feel his manager’s eyes boring into his back. It’s Charles coming sheepishly into Hodges’ office without being asked so he could apologize for slamming a bat into the rack — and Hodges remarking that he knew Charles would come. It’s Hodges quietly but pointedly rebuking Ron Santo — not even his own player — at home plate, with no one to know but the two of them and an umpire.

How Hodges handled Jones has been misused because it’s convenient shorthand for something that was so rarely visible. But rather than exemplify Hodges’s toughness and wisdom, that day in July was a rare mistake born out of frustration — one that could have derailed a fine season from a sensitive player the Mets couldn’t afford to lose. After the incident, Hodges was more himself — he challenged Jones behind the closed door of his office, made vague excuses to the writers about a bad foot, kept his star player on the bench for a few days, then declared that bad foot healed once he knew the point had been made. That was much more his style. On occasion Jones hasn’t obeyed the script written long ago and been more forthright about his feelings: “I thought it could have been done another way. I was upset and hurt.” He wasn’t alone. When Hodges came home after the doubleheader, a stunned Joan Hodges had a pointed question for her husband: “Whatever possessed you to do it?”

As we all know, the Mets won, with Jones hitting .429 against the Braves and catching that final out. And he’d remain a mainstay of the team for the next several years, becoming the Mets’ all-time leader in hits, runs, steals and RBIs in 1971, becoming the first Met to 1,000 hits in 1973, and playing a key role in the Ya Gotta Believe charge to an unlikely World Series berth — Jones hit six homers in the last 10 games of ’73 and was the man in the middle of Dave Augustine‘s famous “ball off the wall.” But his knee was betraying him, and ended his season early in August 1974.

The next year, Jones remained in St. Petersburg, Fla., to rehab his knee after the Mets went north. What followed was one of the most shameful incidents in team history. It started in early May, when police arrested Jones on indecent-exposure charges. The cops said he’d been found sleeping naked in the back of a station wagon with a 21-year-old white woman, also naked, who was carrying narcotics — and yes, the racial identification was most certainly relevant in Florida in 1975.

The story quickly fell apart. The station wagon morphed into a panel van, casting doubt on the idea that anyone had been exposed according to any standard of decency. The narcotics turned out to be a joint and a couple of pot pipes in the woman’s purse. Jones insisted that the only part of him that had been naked had been his feet. The charges were dropped.

At that point, whatever happened in Florida should have been no one’s business outside of the Jones house, but the Mets wouldn’t let it go. M. Donald Grant fined Jones $2,000 and forced him to hold a press conference at Shea before his teammates and his wife. He was made to read an apology written by the front office, with mea culpas addressed to not only his wife and children but also “all Mets fans and to baseball in general.” Union boss Marvin Miller accurately called out Grant’s stunt as “a tasteless display of economic power.” Grant’s ouster of Tom Seaver would be remembered with more bitterness, but no part of that sordid affair was as cruel and demeaning as what he did to Jones. Reporters who were there would reference the palpable unease in the room for the rest of their careers.

It was the beginning of the end. Jones returned to the Mets, but Dave Kingman had taken his job, his knee still wasn’t right, and Grant had it in for him. Jones’ doctor told him not to do calisthenics with the team, which got twisted into more evidence that Jones was lazy. Things came to a head in July, when Yogi Berra sent Jones up to pinch-hit and to take over outfield duties. Jones refused — because he’d been stuck on the bench and was angry about it, but also because he hadn’t taped up his balky knee, as he did whenever he knew he was going to play defense.

Berra accused Jones of disrespect and insubordination, and told Grant it was the outfielder or him. The Mets tried to trade Jones, who refused two proposed deals (as was his right as a 10-and-5 man), then released him. A couple of weeks later, after Seaver told Grant Berra had lost the clubhouse, they got rid of the manager as well. Jones would return for a cameo with the White Sox in 1976, then retire. He was only 33. Thirty-three, a World Series hero, and the man who held several Mets’ offensive records. He deserved better — but then even a cup-of-coffee guy deserved better than what Grant did.

Time would heal some of the wounds — Jones returned briefly as a minor-league hitting instructor in the early 1980s, with Darryl Strawberry one of his star pupils. But with a little better health and a lot less Grant and Berra, he might have been Strawberry’s teammate — a legendary pinch-hitter who briefly overlapped with a budding superstar, knitting two eras and two titles together.

Instead, he went home to Africatown — where he’s still hard at work, fixing houses and seeking business deals and serving as the town’s unofficial mayor. When reporters chat with Jones these days, he sounds different than the instinctively accommodating player who excused Hodges’ worst day as manager, or downplayed Grant’s cruelty to him. “Growing up in the Jim Crow south, I learned my lane,” he said earlier this year. “Hell yes, I stayed in that lane. Now every lane is ours, and we have changes to make.”

It’s easy to overthink Jones’s little genuflection in the outfield — a baseball season is a grueling marathon, and he was a hard-nosed athlete looking to put away a last out in a magical season. That’s enough. But I don’t think it’s too much to imagine that at least some of those other things informed his reaction. He’s standing next to his boyhood friend — Jones even pounds the glove as the ball descends, nicking Agee’s habit. They’re a long way from Mobile, in a world that hasn’t always been kind to them. But they’re there, and once that ball finishes its journey, they’re going to be atop that world. That’s not going to change everything — nothing’s ever that simple — but if something like that can happen, what else might be possible one day?

“Come on down, baby,” Jones tells the ball, and it does.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1965: Ron Swoboda

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1967: Al Schmelz

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1971: Tom Seaver

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1974: Tug McGraw

1975: Mike Vail

1976: Mike Phillips

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1985: Dwight Gooden

1986: Keith Hernandez

1987: Lenny Dykstra

1988: Gary Carter

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1997: Edgardo Alfonzo

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2007: Jose Reyes

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2010: Ike Davis

2011: David Wright

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2015: Michael Conforto

2017: Paul Sewald

2019: Dom Smith

2020: Pete Alonso

This series is easily one of the most enjoyable and evocative expressions of Mets lore. Thank you for reminding me of why I love this team.

I have to add my compliments to those of the previous commenter. I’ve been enjoying this series immensely, and I’ve learned more than a few things I didn’t know before. I hope for your sake that this will eventually become a book, because I’m sure that folks beyond this blog would enjoy reading it as well.

That’s the plan! More soon!

I loved Cleon, scar and all, and he remains today an idol, hero, and saint to me. And he had/has a unique speaking voice, it is very fast, loved hearing it on Kiner’s Korner, and in those celebratory clubhouse interviews.

But Jeez, couldn’t he have just pinch hit and played the field that day? If it wasn’t wrapped, it should have been, and just get out there.

And who among us has not fielded a high fly ball in the outfield and dropped to one knee while doing it, a subconscious tribute to one of our heroes.

Always one of my favorite early 70’s Mets, and I never realized that was a scar. I just thought it was part of his (very familiar) face.

A bit late to the conversation, but nice job of telling Cleon’s story. I read this and then my wife and I were talking about what Cleon endured…we’re not talking about somebody who was alive 150 years ago, he’s only something like 17 years older than me. From what happened to his family to M.Donald Grant (May He Rot In Hell For All Eternity) treating him like a child who deserved to be punished, to the fact that he still lives in a neighborhood that can be traced back to slavery…shows how far we still have to go. And throughout it all, I’ve always seen him as a gracious mild-mannered man, while people who haven’t dealt with 1% of the crap he has go through life screaming with the veins in their neck popping out.

And Seth, there was always Grote with that little white discoloration above his upper lip. I just thought he had just drunk some milk before he went on Kiner’s Korner.

[…] Ashburn 1963: Ron Hunt 1964: Rod Kanehl 1965: Ron Swoboda 1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice 1967: Al Schmelz 1968: Cleon Jones 1969: Donn Clendenon 1970: Tommie Agee 1971: Tom Seaver 1972: Gary Gentry 1973: Willie […]