Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

When I was a teenager, a lot of people assumed I’d be a sportswriter. Which made a lot of sense: I loved baseball and writing, so why not put the two together? But I was pretty sure I didn’t want to do that.

For one thing, I knew enough about sportswriting to understand that you couldn’t be in the press box and be a fan, and I didn’t want to stop being a fan. There were other ways to write, but you either were a Mets fan or you weren’t, and being a Mets fan was important to me.

For another thing, I’d read enough scoop-in-the-locker-room stories to learn that daily exposure to millionaire athletes was probably not going to lead to my liking them more, and almost certainly was going to lead to my liking them less — in some cases, a lot less. I didn’t want to know that my team’s veteran first baseman was a surly asshole, or that the ace of its starting rotation was a leering, juvenile dipshit. I was already beginning to sense that there was a huge gulf between my life and that of baseball players. In the vast majority of cases, we’d have nothing whatsoever in common, and the professional relationships I’d have to forge would only widen that gulf. Their paychecks would come with two or three extra zeroes, and there’d be many times — a bad game, a clubhouse controversy, a messy collision between on-field and off-field worlds — when they’d see me as an adversary.

Why in the world would I trade being a Mets fan for that?

Then there was a third thing, one I was nowhere close to understanding then and am still sorting out now that I’m north of 50. I didn’t want to cross that gulf. I had no particular interest in meeting ballplayers or knowing them as people.

Is that snobbery? I’m sure there’s more of that at work than I’d like to admit, some jocks vs. nerds residue that can never be cleaned out of the gears. But I don’t think it’s the real reason. For one thing, I don’t think of ballplayers as dumb — I’m floored by their ability to recall long-ago at-bats, their radar for picking up patterns and tells, and the superhuman discipline and focus possessed by even the most marginal big-leaguer. They outclass me as thoroughly in those respects as they do in hand-eye coordination and fast-twitch musculature, and those mental weapons are as important to their success as their physical gifts.

The gulf is more about the fact that the players determine the outcome of events on the field that mean everything to me, and I can have zero effect on those outcomes, no matter how hard I cheer or how eloquently I write or how diligently I follow whatever whammy seems to be working at the moment. I am not part of a shared endeavor, no matter how much I’d like to think otherwise and how many times I refer to the Mets as “we.” The players are doing a job for which they are uniquely suited, by genetics and lifelong training; I am living and dying on the outcome of their job performance. They may as well be superheroes, both in terms of ability and in terms of being participants in a drama I can only observe.

There’s no bridge long enough or strong enough to cross that gulf, and knowing ballplayers as people has always struck me as a doomed attempt to rivet one together. Still, I’ve done more metalwork than I might have guessed: In one of life’s ironies, technology and friendship and chance conspired to produce this blog and make me at least a quasi-sportswriter after all. During the Mets’ Prague Spring of outreach to bloggers, I found myself meeting players in occasional media-room and dugout sessions. It was fascinating hearing R.A. Dickey break down his approach to pitching, it was fun asking Dwight Gooden what he might have accomplished if he’d been allowed to hit left-handed, and it was a treat to interview Ron Darling at length for a Queens Baseball Convention panel. But those brief forays were about as far down that road as I wanted to go, and did nothing to make me think I’d chosen the wrong path years earlier.

All of which has brought me, at last, to Lenny Dykstra.

I was 16 when Dykstra made his debut for the Mets in 1985, and I loved him instantly. He was pint-sized in a game of giants, and he played baseball with ravenous joy, gorging on it like a kid in that two-hour grace period from nutrition and house rules that ends Halloween Night. Whether at the plate, on the basepaths or in the field, he was an agent of gleeful chaos, a player who seemed able to will himself to success.

And it didn’t hurt that he was ferocious bordering on crazy. I loved that the Mets of the mid-80s seemed more like a mob of banditti than a baseball team. I gloried in their bad behavior: the arrests in Houston, the plane they trashed so thoroughly that it’s a minor miracle it stayed airborne, their serial fistfights and dust-ups, and the fact that other teams and other fans hated them. They were brash and loud and crass and backed up every obnoxious thing they said. When you’re a teenager, that’s pretty appealing.

Dykstra fit in perfectly, paired at the top of the lineup with his partner in grime Wally Backman. I can close my eyes and bring him to life, blinking out at the pitcher with what looks like impatience, jaws worrying at the baseball-sized hunk of chewing tobacco in his cheek, fingers twitching and rearranging themselves on the barrel of the bat. In a minute he’ll have spanked a ball three-quarters of the way into the gap, certainly a single and just maybe a double, except it’s Dykstra and there’s no way he’s going to settle for a single, and he’s sliding into second face-first. Now he’s standing out there filthy and triumphant, with the enemy fans muttering and the pitcher stalking around in a little circle, and here’s Backman, his twin terror, staring out from the plate with his bat cocked like a trigger of a pistol, and if the pitcher doesn’t get Backman out the Mets are already up 1-0 and Keith Hernandez and Gary Carter are coming up and oh boy.

And if Dykstra doesn’t get that hit? If the ball hangs up long enough for the center fielder to glide over and pluck it out of the air? Then he’ll take himself back to the dugout, every step of the way marked by blinks of disbelief — Roger Angell described that Dykstra reaction as “his disbelieving, Rumpelstiltskin stamp of rage,” and as always it’s perfect. Dykstra succeeding made you laugh out loud for the sheer joy of what you’d seen; Dykstra failing made you laugh out loud for the cartoon fury he radiated. Years later, Dykstra told Larry King that after every game he’d take a minute to sit at his locker and ask himself a simple question: If he were a fan, would he have paid money to sit and watch him play? The answer was yes, most emphatically yes.

In October 1986 Dykstra struck a pair of critical blows for the Mets. He won Game 3 of the NLCS with a two-run walkoff homer off Dave Smith, averting what would have been a 5-4 Houston win and a 2-1 series lead. It’s another moment imprinted on my brain: Backman throwing his arms skyward, seeing the ball is gone; a few seconds later, Dykstra vanishes into a sea of blue jackets worn by larger teammates at home plate, nothing visible but his face. I was briefly worried his teammates would strangle him in their enthusiasm, but of course he was fine — wouldn’t you be, in the greatest moment of your life? Later, charmingly, he said the last time he’d hit a game-winning homer in the bottom of the ninth had been playing Strat-O-Matic against his brother.

Dykstra was at it again in Game 3 of the World Series, leading off at Fenway against Oil Can Boyd with the Mets down two games to none and panic in the streets of New York. Dykstra connected on a 1-1 pitch, the swing and trajectory reminiscent of the contact he’d made against Smith. The ball dropped beyond the Pesky Pole for a homer, leaving Boyd stalking around the mound and sending mutters through the Red Sox crowd. Dykstra all but strutted around the bases, walking into the dugout looking like a gunfighter who’d just cleared a street of outlaws. Though the ’86 Mets being who they were, maybe he looked more like an outlaw who’d just eliminated all the deputies.

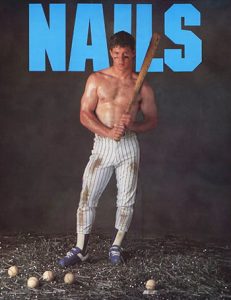

Of course he was a folk hero — how couldn’t he be? There was the poster — a shirtless Dykstra, looking about 12, surrounded by nails and baseballs. It was simultaneously awesome and deeply ridiculous. Or the video from 1986 Mets: A Year to Remember, which showed highlights of Dykstra and Backman, complete with extremely mid-80s effects, accompanied by Duran Duran’s “Wild Boys.” OK, that one was a lot more ridiculous than awesome — I remember realizing what was happening and trying, unsuccessfully, to sink through my couch and keep going until I hit the Earth’s core. Or how about his book, also called Nails? Dykstra wrote that one with Marty Noble, whom I imagined must have dined out on the stories of their collaboration for the rest of his life. After it came out in 1987, Dykstra proudly brought a copy into the spring-training clubhouse; a bemused Backman paged through it and said something like, “if you took all the ‘fucks’ out of this, it would be a 25-page book.” (Lenny’s verdict on Calvin Schiraldi, by the way: “Everybody gets the tight asshole sometimes.” Which might not be how I would have phrased it, but isn’t wrong.)

Of course he was a folk hero — how couldn’t he be? There was the poster — a shirtless Dykstra, looking about 12, surrounded by nails and baseballs. It was simultaneously awesome and deeply ridiculous. Or the video from 1986 Mets: A Year to Remember, which showed highlights of Dykstra and Backman, complete with extremely mid-80s effects, accompanied by Duran Duran’s “Wild Boys.” OK, that one was a lot more ridiculous than awesome — I remember realizing what was happening and trying, unsuccessfully, to sink through my couch and keep going until I hit the Earth’s core. Or how about his book, also called Nails? Dykstra wrote that one with Marty Noble, whom I imagined must have dined out on the stories of their collaboration for the rest of his life. After it came out in 1987, Dykstra proudly brought a copy into the spring-training clubhouse; a bemused Backman paged through it and said something like, “if you took all the ‘fucks’ out of this, it would be a 25-page book.” (Lenny’s verdict on Calvin Schiraldi, by the way: “Everybody gets the tight asshole sometimes.” Which might not be how I would have phrased it, but isn’t wrong.)

1987 is the year Dykstra represents in A Met For All Seasons; it’s also, in retrospect, the year things started to go wrong. Besides his new, gloriously fuck-strewn book, Dykstra showed up encased in new muscle. “Lenny, what the fuck happened to you?” asked Backman. Dykstra’s response, delivered in front of teammates and reporters and everyone else: “Dude, been taking some of those good vitamins, you know?”

Dykstra hit 10 homers that year, a career high, but feuded with Davey Johnson about having to share center field with Mookie Wilson. Wilson didn’t like it either, and asked for a trade. The Mets eventually solved the problem in the worst of all possible ways, by trading both of them. In June 1989 Dykstra and Roger McDowell went to Philadelphia for Juan Samuel, who wasn’t a center fielder. Six weeks later, the Mets traded Wilson away too. Center field would be a tragicomic disaster in Flushing for years, and even as the Mets floundered and flailed to fill the position some small, mean little part of me would remember the day I’d heard Dykstra had been traded and think, Good, it’s exactly what you all deserve.

Meanwhile, Dykstra and Philadelphia proved a perfect match. In 1993 Dykstra — by now so inflated that he looked like a sidekick of Popeye’s — led the league in runs, hits and walks, finishing second to Barry Bonds in the MVP race and hitting .348 in the World Series with four homers. A town with a chip on its shoulder embraced a player with a boulder on his. Phillies fans adored Dykstra for his grit and hustle, for his belief that he was immortal, and for his refusal to be anything other than himself, regardless of the scorn that being himself brought his way. In ’93, after the World Series, Major League Baseball sent Dykstra on a goodwill tour of Europe (no seriously, they did), which you can read about here — is the best detail Dykstra buying a German shepherd in Dusseldorf because “this is where they come from” or the second bottle of Château d’Yquem he ordered to go after dining at Paris’s La Tour d’Argent? It’s a minor tragedy, at least, that this visit never produced a Get Him to the Greek-style comedy.

Phillies fans so loved Dykstra that they were willing to overlook the stuff that wasn’t so funny — such as the May 1991 car crash after a bachelor party that could easily have killed him and Darren Daulton, or someone else. (Dykstra blew a 0.179 on the Breathalyzer test, indicating a level of impairment somewhere between “you may fall and hurt yourself” and “standing and walking may require help, as balance and muscle control will have deteriorated significantly.”) They overlooked when Major League Baseball put him on probation for losing $78,000 playing illegal poker games with shady company in Mississippi. They laughed off stories like this one, from Philadelphia Magazine. But I read those stories too, and I gave him a pass of my own. Dykstra made mistakes, sure. He was obsessed with money, the trappings of wealth and the thrill of playing for high stakes — any Mets beat writer could have told you that. But he didn’t strike me as having a mean bone in his body — and there was an up-by-his-bootstraps honesty to his live-in-the-moment vulgarity that’s deeply American.

After 1993 injuries took their toll, particularly for a player incapable of pursuing baseball at anything less than dangerous speed. Dykstra retired after 1996, 33 years old and beloved in two very different cities. And since he retired, everything has gone horribly wrong. Or, perhaps, it’s gone pretty much as it went then, except there are no baseball heroics to make us want to hand-wave the rest away.

Sure, some of the stories were entertaining, such as Dykstra’s brief time in the spotlight as a stock-market guru, anointed by CNBC’s Jim Cramer as a homespun American genius. But others weren’t, at all. In 2011 he was charged with indecent exposure, allegedly for advertising for housekeepers on Craiglist, then announcing the job duties included massages and disrobing. (He served nine months.) In 2012 Dykstra pleaded guilty to bankruptcy fraud, concealment of assets, and money laundering and was sentenced to six and a half months in prison, the end point of an odyssey that began in 2009 with a bankruptcy filing connected to his purchase of Wayne Gretzky’s house. In 2018 he was charged with pulling a gun on an Uber driver who refused to let him change destinations, and for possession of cocaine and methamphetamines. (The drug charges were dropped and he pleaded guilty to disorderly conduct.) Dykstra launched a magazine, The Players Club, that he envisioned as the beginning of a concierge-cum-investment service for wealthy athletes. It crashed and burned, with one employee writing this scathing account of his time there. Among other things, he alleged that Dykstra had said that “nobody can call me a racist—I put three darkies and a bitch on my first four covers.”

Trying to untangle all this, I ran across this clip of Dykstra talking with Larry King in 2016. It was sad to watch Dykstra, still restless and fidgety but also now pudgy and gray, veer between defiance and remorse and never quite manage to land on either one. He almost makes it at one point, telling King that “that mentality that I had in baseball – do whatever I have to do, win at all costs – when you take that mentality out to the normal world…” But he never completes the thought. He’s off grabbing for the next thing.

Dykstra is a supporting character in Moneyball — Billy Beane told Michael Lewis about a day in the Mets’ dugout when the two were watching the opposing pitcher warm up and Dykstra asked who “that big dumb ass” was. An astonished Beane told Dykstra it was Steve Carlton, one of the greatest left-handers in the game. Dykstra took this in, sized up Carlton and announced, “Shit, I’ll stick him.”

“Lenny was so perfectly designed, emotionally, to play the game of baseball,” Beane said. “He was able to instantly forget any failure and draw strength from every success. He had no concept of failure. And he had no idea where he was.”

The same qualities that made Dykstra great on the baseball field made him a train wreck away from it. That’s what he almost finished telling King, and it seems like a grim but simple lesson. But then, last year, things got more complicated.

Darling wrote a book in which he revisited the Mets’ Game 3 World Series victory, and said something we hadn’t heard before. He said that while Boyd was warming up, Dykstra was in the on-deck circle “shouting every imaginable and unimaginable insult and expletive in his direction – foul, racist, hateful, hurtful stuff. I don’t want to be too specific here, because I don’t want to commemorate this dark, low moment in Mets history in that way, but I will say that it was the worst collection of taunts and insults I’d ever heard – worse, I’m betting, than anything Jackie Robinson might have heard, his first couple times around the league.”

By then, I was used to wincing whenever Dykstra’s name crossed my radar — because, as with Gooden, I assumed the news would be something sad and/or ugly. But this new allegation seemed hard to believe. It wasn’t that I was inclined to side with Dykstra over Darling — my inclination would be the reverse — but that I looked askance at the details and the setting. Fenway is tiny, with fans and players practically on top of each other, and Bad Stuff About the ’86 Mets has been a cottage industry since, well, 1986. Darling was clear that he heard what Dykstra said, and that Boyd did too. Which means dozens if not hundreds of other people must have heard it as well. And yet that story stayed under wraps for nearly a quarter-century? How was that possible?

Dykstra sued his former teammate for defamation and libel, which led to a rather extraordinary decision. The judge in the case reviewed Dykstra’s past missteps in excruciating detail, and wrote that “Dykstra’s reputation for unsportsmanlike conduct and bigotry is already so tarnished that it cannot be further injured by the reference. … In order to [assert a cause of action for defamation], Dykstra must have had a reputation capable of further injury when the reference was published.”

In other words, Dykstra’s reputation was already so wretched that it was impossible for him to be defamed — a hell of an addition to his other baggage.

Dykstra’s post-baseball life has been a drumbeat of stories that made you say, “Oh God, really?” — a few amusing, some merely tawdry and embarrassing, others frankly disturbing. And yet, even after all this, I find myself wanting to do mental gymnastics on his behalf — not to claim these things didn’t happen, but to somehow separate them from the exploits of a ballplayer who was always worth paying to see. I keep wanting a gulf between these two Lenny Dykstras. I think that’s why I don’t want to believe Darling’s story about Game 3 — it’s a bridge over that gulf, an insistence that no such separation is possible, and an assertion that there’s only ever been one Lenny Dykstra.

I keep fighting that idea, and I’m not sure why. Because isn’t it the same insight I had all those years ago, the one that steered me away from sportswriting? Appreciate the players for what they do, and be careful about delving too deeply into who they are. Because you might wind up liking them less. Even if that’s a verdict you want desperately to resist.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1965: Ron Swoboda

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1967: Al Schmelz

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1971: Tom Seaver

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1974: Tug McGraw

1975: Mike Vail

1976: Mike Phillips

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1986: Keith Hernandez

1988: Gary Carter

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1997: Edgardo Alfonzo

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2007: Jose Reyes

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2010: Ike Davis

2011: David Wright

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2017: Paul Sewald

2019: Dom Smith

A very thought-provoking read. I,too, loved Lenny as a player, and I thought the Samuel trade ripped the guts out of the team. But there was definitely a certain amount of Ty Cobb in Lenny, an obsessive desire to win bordering on the pathological. Reading about his post-baseball life just makes me sad. It’s hard to tell whether he’s just a coarse-souled con man who happened to have an insane talent for baseball in his younger years, or a troubled soul who can find no peace in a world more complicated than balls and strikes. Or both.

“Dykstra’s reputation was already so wretched that it was impossible for him to be defamed” – Ouch. I thought this level of infamy was reserved for people drowning kittens in a barrel. Those that do it for a living, and those that do it for joy.

That *is* some Nails picture above there, though. Must have been good vitamins. Some A, some C, and all the Bs.

I hear Boston was a *pretty racist* place in the days. Maybe slurs of sorts weren’t out of the ordinary there even in the 80s. People wouldn’t remember Dykstra doing it, because some guy or other would do it all the time. I might be wrong. My knowledge of Boston baseball is limited to like three MLB broadcasts a year and whatever appearances of Bill Burr on Conan have been uploaded to Youtube.

This really hit home for me. I loved watching Nails play and will never forget watching his playoff home run against the Astros from the best seat I ever had at Shea Stadium, a few rows behind the Mets dugout. But then there was Lenny the person. As an associate producer for “Mets Extra” for three-plus years starting in 1987, I spent a lot of time in the Mets locker room before and after games and Dysktra was the only player who was ever a dick to me, and on more than one occasion. I will never forget the look of horror on rookie Keith Miller’s face when a snarling Dykstra tried to kick me out of the locker room for no reason. I went out of my way to avoid him from then on and a week later when he got a game-winning pinch hit against the Cardinals, I was directed to track him down for the postgame show. Instead, I suggested that Randy Myers (a real good guy, by the way) just won his first major league game so let’s have him on instead. I also felt a lot better when the other associate producer told he how nasty Dysktra was to him as well.

And for those keeping score at home (that would be me), I am now 2-for-3, sort of. I picked Lenny, but for his 1985 rookie season. My ’87 pick was the totally unforeseen ace of the staff that year, Terry Leach. Now there’s a guy who probably had a much happier post-baseball life than Mr. Nails.

Well if you ask me Jason, you (and Greg) are sportswriters, and damn good ones. It’s a profession/calling/thing that’s evolved over the years, but bottom line is that you both write about sports. Therefore, sportswriters, and this was a beautiful example of your craft. There hasn’t been much to laugh about in 2020, but that judge’s ruling in Dykstra’s suit against Darling was one of the biggest and best laughs I had this year.

And this was timely too. Just earlier today a friend and I were having a text conversation. He is a regular at Mets Fantasy Camp, and is someone who appreciates that there is more to life than baseball even when you get to meet guys who got famous by playing it. He was telling me about a few former Mets who – I’ll spare everyone the details that would change the subject significantly – hold beliefs that I find really abhorrent. My response was that I do my best to separate Mets I cheer for from guys I likely would not get along with at all. But in Dykstra’s case, I can’t separate them. People like Doc are pitiable, he simply wasn’t strong enough to successfully battle his demons. But Dykstra is just a selfish, entitled, irresponsible asshole who sees nothing in any way other than how it benefits or entertains or pleases Lenny Dykstra. Everybody makes bad decisions. But if you want to be a responsible adult, you learn from your mistakes. Dykstra doesn’t and doesn’t seem to think he needs to.

As much fun as it was to watch Lenny on the baseball field, I have to believe he is a graduate of the Trump University School of Financial Responsibility. I wouldn’t be surprised if he told the judge in the Darling lawsuit, “Oil Can Boyd. I don’t know who he is.”

Ah, Lenny. His walk-off in Game Three was on my 21st birthday, to date still the best birthday I’ve ever had. As much fun as he was to watch on the field, it’s sad how he embraced his inner scumbag and became such an unrepentant little slimeball. But we’ll always have those homers and his heroic triple in the 9th inning of Game Six of the NLCS.