The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 14 June 2017 12:49 am We’ve not yet reached the longest day of the year, but Zack Wheeler was off the mound and in the clubhouse before literal darkness descended over Citi Field Tuesday night, so either it’s staying light later or the pitchers are growing short.

Or both.

Wheeler’s reign as undisputed Mets ace lasted one turn of the improved rotation, as he was shelled, shellacked, schlemieled, schlimazeled, what have you by the defending world champion Chicago Cubs in a stint that was both disturbingly brief (1.2 IP) and dragged on interminably (62 pitches). It was a Zack kind of an evening, except for the lack of nightfall and the part where Wheeler guts it out admirably for five to seven innings.

Joe Maddon shuffled the Cubs’ lineup and his alchemy produced its desired effect. First baseman Anthony Rizzo batted first and hit a leadoff homer. Second baseman Ian Happ, born the day the 1994 baseball strike began, batted second and belted a second-inning grand slam to raise Chicago’s lead to 6-1. The Mets’ aspirations toward a fifth consecutive victory pretty much walked off the job right there. Pitchers named Josh and Neil and another Josh were asked to soak up inning after inning after Zack was removed. Cub batters continued to spawn more runs. Jon Lester notched his 150th career win. He could’ve nailed down his 151st and 152nd if they’d let him.

Yoenis Cespedes left the game as a precaution against everything that could go wrong going wrong. Asdrubal Cabrera’s left thumb returned to the disabled list, taking the rest of Asdrubal with it. Michael Conforto’s back stayed stiff and was again kept out of harm’s way. Nobody else seemed to get hurt, though with this team you never can tell.

The final was 14-3, the lone Met bright spot being the re-emergence of the Topps card crate Gary, Keith and Ron dig out of their broadcast lair to make these recurring thrashings go down smoother. The Mets have never come back to win a game in which the announcers pluck cards at random and riff accordingly, yet once Topps time rolls around, my sole rooting interest is for lengthy plate appearances and baserunners galore, no matter who’s up. Fewer outs equals more cards, more cards equals more riffing.

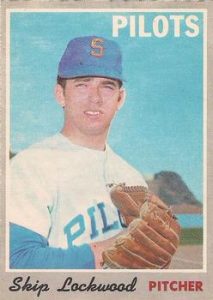

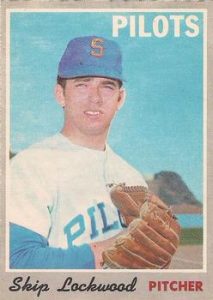

Skip and I hung out a lot when I was seven. My favorite find in this particular blowout treasure trawl was Keith’s 1970 Skip Lockwood, pictured then with the Seattle Pilots who were already the Milwaukee Brewers by the time the unassuming righty from the transferred franchise infiltrated my consciousness. By the end of the ’70s, Skip Lockwood would be the Mets’ closer and I would maintain a vested interest in securing his cardboard image. At decade’s dawn, when I was seven and first buying packs, I was inundated with 1970 Skip Lockwoods. Didn’t want ’em; got ’em anyway. When I wasn’t getting a Skip Lockwood, I was getting a Skip Guinn, yet it never crossed my mind to skip a chance to accumulate more cards, just as I never dreamed of skipping out on Tuesday’s night’s debacle. By the third inning, at which point it was Cubs 9 Mets 1, I was honestly thinking, “Oh boy, maybe they’ll do the cards tonight!” I was like a kid in a candy store, or, more precisely, “the candy store,” which is what we called Belle’s Luncheonette, the place where I committed dimes to packs, straining futilely to discern which ones might contain within them the stars who were destined to never appear.

I’d go through all those packs in hope of a Seaver or a Mays. I learned to accept the Lockwoods and the Guinns. I sat through a double-digit pasting forty-seven seasons later and I considered myself rewarded when Skip Lockwood appeared. And to think, the summer solstice is still a week away.

Spend a few innings with me this Thursday night at Bergino Baseball Clubhouse in Manhattan for a discussion of Mike Piazza, Tom Seaver and maybe Skip Lockwood. Details here.

Many thanks to WOR Sports Zone host Pete McCarthy for having me on to discuss Piazza. Listen to Pete before and after every Mets game on 710 AM. You never know who you’re going to hear.

by Jason Fry on 13 June 2017 8:23 am Jacob deGrom was good. He was really good.

Not so long ago, this wouldn’t have been a surprising thing to write. But it’s been a surprising season, to put it mildly.

The key to deGrom’s successful night was that he reintroduced his change-up to complement his fastball. In the postgame debrief, DeGrom passed along analysis from Dan Warthen that he’d thrown the change 4% of the time this year, compared with 20% in years past. Delve a little deeper into the postgame comments and you wound up in chicken-and-the-egg territory: deGrom had shelved the change-up because it kept floating up to the plate and getting hammered, and so worked on his mechanics to keep himself closed and restore the change-up’s bite. Which led to reclaiming the pitch. Or maybe it was the other way around.

But then pitching is often chicken-and-the-egg stuff, with mechanics and command and confidence all in the mix and solutions hard to tease out. Whatever Jake had been doing wasn’t working — he got mauled by the Brewers and then by the Rangers, and suddenly looked like the outlier with Zack Wheeler continuing to improve, Matt Harvey achieving better results and Seth Lugo and Steven Matz returning with debuts better than we’d dared imagine.

One run over nine innings — yes, that was a Met starter with a complete game — ought to take care of that narrative.

Flies in the ointment? But of course — this is still the Mets, after all. Seeing deGrom throw 116 pitches made me cringe, even if the last one was a 97 MPH fastball that erased Willson Contreras for the win. DeGrom hit 118 pitches in his turn as a fairy-tale hero against the Pirates, a number he’d only exceeded twice in his career, and that outing was followed by the two stinkers. Correlation isn’t causation, of course, but there’s no arguing the chronology.

Still, I’m inclined to forgive both deGrom and Terry Collins for this one. DeGrom clearly wanted an emphatic notice that he’s not the pitcher we saw slumped on the bench in Texas with a consoling managerial arm around his shoulders. A complete game would be a marker for the entire pitching staff, whose competition has turned healthy of late. And goodness knows the relief corps doesn’t need anything added to the odometer. (Jerry Blevins was unavailable and Addison Reed was iffy.)

On the other side of the ball, Asdrubal Cabrera declared himself not dead yet with a pair of home runs, and Jay Bruce chipped in another one — that’s 17 in what’s shaping up as a pretty interesting season for a Plan B outfielder that plenty of people (including me) wanted to leave by the curb in Port St. Lucie. Though Yoenis Cespedes came out of the game with leg issues, and Michael Conforto never got into the game with a sore back.

Cespedes’s leg issues, we’re told, have nothing to do with his balky and less-than-completely healed hamstring — this was a sore left heel. Oh, OK. On the one hand, I suppose that’s good because it’s not the hamstring but something else. On the other … it’s something else.

But that’s a pretty good description of this season, come to think of it. Accompany it with a smile, a groan or just an all-encompassing shrug, but it’s been something else.

* * *

Were you at Shea Stadium the night of the ’77 blackout? If you were, Patrick Sauer would like to talk with you for an article. He’s @pjsauer over on Twitter, or email him here. Thanks!

by Jason Fry on 12 June 2017 1:38 am Watching baseball is a fine way to spend an afternoon, but not quite as fine as watching the Mets finish taking three of four from the Braves with another fine pitching performance and relief that makes you exhale instead of rolling into a ball and the only sighting of Freddie Freeman one that involved Steve Gelbs and some earnest questions near the aromatherapy room.

Yeah, I’ll take that way of spending an afternoon any chance I can get.

For the second day in a row, the Mets welcomed back a prodigal pitching son with an uncertain elbow — and for the second day in a row our anxiety turned into relief and then glee as he looked better than good. This time the returnee was Seth Lugo, the Jason Isringhausen lookalike (seriously, it’s uncanny) who came out of nowhere last year to help lift the Mets to an unlikely wild-card play-in game. Lugo, partially torn UCL and all, rode his uncanny breaking ball, found the stride on his fastball after a couple of innings and held the Braves at bay much as Steven Matz did on Saturday.

For the second day in a row, the Mets’ defense wasn’t a killer with the game on the line. In the fifth, Matt Adams strode to the plate with the bases loaded, one out and the Mets up 2-1. (Actually Adams walked to the plate the same way he does most every at-bat, but “strode to the plate” is what you’re supposed to say at such a juncture, so there you have it. Matt Adams strode to the plate like a colossus and may or may not have said “Grrr.”)

Lugo got ahead 1-and-2 and threw a fastball at the knees and moving off the plate, which has been the conventional strategy in such situations for nearly a century for good reason. If Adams offered at it he was likely to chop it to the shortstop; if he took it, Lugo would have sped up his bat and got him looking outside as preparation for a breaking pitch on the inside corner.

The strategy worked … sort of.

Adams slapped it to short, but it was a hard one-hopper to the right of Asdrubal Cabrera, whose range has decayed precipitously this year the way everyone insisted it would last year. Today Cabrera had just enough range and corralled the ball on the infield dirt, with his momentum spinning him clockwise to face the outfield and then second. He reached into his glove, failed to get the handle on the ball, reached again, got it and shot-putted it to Neil Walker, who came across the bag, twisted and hurled a not-entirely-on-balance relay to first to Wilmer Flores, stretching about as far as Wilmer Flores can stretch.

It was just a hair too late, and the game was … oh wait, this is 2017 and first-base umpiring has become a collective shrug. (Actually this one was very close, but the point stands.) Relays were consulted, Mets and Braves peered at giant screens, baseball employees in Chelsea huddled, umpires stood around, the Freeze limbered up somewhere behind the outfield fence, and eventually Adams was called out.

It was a very close play whose very closeness ebbed and flowed through tiny factors: Cabrera’s direction of spin, Adams’s speed, Cabrera’s fingertips searching for seams, Wilmer’s stretching. Very close and just tipped enough to the Mets’ side of the ledger to be good news.

For the third day in a row, the Mets were locked in a close game late. This time the cavalry didn’t arrive: this time, Yoenis Cespedes batted with the bases loaded but popped the ball straight up.

That at-bat was also the Weird Terry Collins Decision of the Day, a streak we’ll settle for describing as prolonged. Cespedes was lurking on the Mets’ bench in the top of the ninth, but after Rene Rivera failed to get a bunt down, Collins let Jose Reyes bat — the same Jose who celebrated his 34th birthday by raising his OBP to a rollicking .261 and short-circuiting an inning by trying to steal third with a lefty up. Reyes golfed a little pop that Dansby Swanson grabbed over a sliding Ender Inciarte. Collins sent Curtis Granderson up to hit for Jerry Blevins, then decided that the arrival of lefty Ian Krol was the time to hit Cespedes for Michael Conforto, who’d had two hits off a lefty that same day and is a far better defender than Granderson, his replacement in left field. Of the three available pinch-hitting slots for Cespedes, Collins chose the one that made the least sense.

Anyway, the Mets had to do things the hard way, except Addison Reed made it look easy. He got Tyler Flowers on a routine fly ball, struck out young Johan Camargo and then faced Swanson, newly inaugurated as the latest in an excruciatingly long line of Braves tormenters.

Faced Swanson and struck him out.

All in all, not a bad long weekend in Atlanta.

by Jason Fry on 11 June 2017 4:29 am Even Mets fans get to have good days.

Honestly, Saturday’s doubleheader with the Braves was about as stress-free as a day dealing with the confounding, confounded 2017 Mets has been. You got drama in both games, with Robert Gsellman and then Steven Matz pitching marvelously but being largely matched by Atlanta competition. But then the drama went away — in the matinee it was Yoenis Cespedes making like Kanye, while the nightcap saw Jay Bruce ride to the rescue, with T.J. Rivera and Juan Lagares adding on to keep any Brave scoundrels at bay.

Heck, Steve Gelbs even let us know what was up with The Freeze.

The second game was accounted for in a crisp 2:41, which for modern baseball is like someone pushed the fast-forward button. Credit the pitchers: to go by his jumbo ERA, Matt Wisler only reserves his A game for starts against the Mets, but we’ve seen plenty of them. He used his big curveball to great effect until the fifth, when one of those big curves came up medium and sat obligingly on the plus part of Jay Bruce’s bat, vanishing into those weird office-cube-looking seats out in right field. Karma alert: it was a pretty good reproduction of the home run Bruce struck here more than a month ago, the one that winked out of existence when a driving rain turned an unofficial game into nothing.

Matz claimed he didn’t have his best stuff, but it looked pretty good to me — he was around the plate, aggressive, and let his defense do the work, which isn’t necessarily a wise strategy with this group but was effective for a day. Gary Cohen and Ron Darling — who have evolved into a terrific duo, by the way — noted that Matz has scrapped his slider, which he felt put a lot of strain on his arm. That was part of a discussion of pitching with pain, something that’s been a source of friction between Mets and Matz; it also struck me that Matz may be one of those brainy pitchers who’s better with fewer choices, something Darling would know about. With his fastball, curve and change-up Matz has plenty to get big-league hitters out, so if a slider puts undue strain on what’s proven to be a somewhat fragile arm, why bother with it?

Cespedes returned in the first game, though — where I have heard this before? — he’s still not running 100 precent. Matz made his 2017 debut a couple of hours later, and it was far more than we could have asked for. Seth Lugo returns later today. Zack Wheeler‘s been terrific of late; Matt Harvey‘s been pretty good; Jacob deGrom has enough of a track record that one can hope he’ll turn back into Jacob deGrom. No one can pull Noah Syndergaard out of a hat quite yet, but patience is a virtue, young Mets fans. Meanwhile Wilmer Flores is hitting everything in sight, Michael Conforto keeps finding walks even while hits prove elusive, and Bruce is quietly putting together a very good year.

Record-scratch time: All that still adds up to six games below .500 with the division and wild cards both steep and perilous climbs above us. The bullpen and defense remain execrable, Terry Collins keeps making bizarre decisions or not making obvious ones, and players who no longer merit it keep getting playing time. T.J. Rivera’s reward for his pinch-hit homer was to be sent down, with Jose Reyes and his no-that’s-not-a-typo .257 OBP inexplicably remaining on the roster.

But for a day that’s the caveat and not the headline. If didn’t let yourself dream a little after eight hours of consistently good news, live a little, willya? The Mets won, nothing bad happened, and dreaming is free.

by Greg Prince on 10 June 2017 5:23 pm I adored Entourage when it began airing in 2004. Then I tolerated it. Then I asked myself why I was still watching it. Then I rooted for it to go away, yet stuck with it to the bitter end in 2011 because I can be that way. My gripe with the HBO series that ran for eight loooong seasons was that whatever predicament Vincent Chase and his boys would get into, there was always some magic solution that rescued them. The worst of it (at least through Season Four) was the episode when Vince’s crew had to get to Cannes and implacable forces conspired against their travel plans. They were stuck. There was no way they were flying.

Then Kanye West shows up at LAX with his amply spacious private plane, invites them aboard and ferries them hassle-free to France. Hey, look — everything worked out fine again!

How freaking ridiculous is that? You can’t expect your problems to be solved every time by some larger-than-life superstar conveniently ambling by with an enormous problem-solving vessel.

Unless you’re a Mets fan.

Yoenis Cespedes and his bat take care of everything, don’t they? Yo comes back from six weeks of major league inactivity, he barely plays any rehab games, he lets it be known his legs aren’t really fully ready for everyday action…and he hits a ninth-inning grand slam to put a tenuous doubleheader opener definitively out of reach.

How could that possibly happen so easily? Because he’s Yo, that’s why. Because he’s Yo and he took a very Yo swing and deposited a very Yo home run over the SunTrust fence. In that instant against Atlanta, he became the plot point to end all plot points. You can be picky about whether he was actually the game changer — the Mets were winning, 2-1, when he took Luke Jackson into the clouds — but I know he’s a blog changer. I was gonna write about how good Robert Gsellman (6.2 IP, 3 H, 2 BB, 0 R) and Wilmer Flores (2-for-4, run scored, run batted in, nice grab at first) looked, how horrifying Asdrubal Cabrera (two errors in the first inning) and Fernando Salas (a home run surrendered to Brandon Phillips on the second pitch he threw) were, and whatever else was about to go right or wrong across a tense Saturday afternoon.

But, nah. I’m just gonna get on Yo’s plane and enjoy the very sweet ride.

by Greg Prince on 10 June 2017 10:44 am What an impressive young man, that Dansby Swanson. The cut of his jib is first-rate, tip-top, simply splendid. Let me show you a few choice selections from his defensive portfolio Friday night…

Hmm, I can’t seem to find any of them. Why, that Dansby Swanson seems to have leapt as from out of nowhere and snatched them from my grasp. What a rascal. What an impressive young man.

Have I told you of the bang-up job that Dansby Swanson did in the sixth inning? Oh, it was something to behold. Matt Harvey had thrown five innings of shutout baseball, nothing but zeroes, and it took him only a thousand pitches to do it. Mister Collins removed Harvey for this Paul Sewald character — he comes highly recommended — and, speedier than a spur-winged goose, the Atlanta fellows had two on and two out and Dansby Swanson, a real sparkplug that one, well, Dansby lashes a double and those two Atlanta fellows come scampering home. Such a sight to see. I’d love to push this button and share the entire tableau with you, but that scalawag Swanson seems to have whisked it away in one furtive motion — the filmed evidence and the device on which I was about to display it. Lightning quick that Dansby Swanson. Have I mentioned what an impressive young man he is?

The best part I am only now arriving at. The score is two to two in the ninth of innings and Dansby Swanson, the very same Dansby Swanson, is the batter with one out. Now Dansby seems to single to center. Old Curtis Granderson, he rises gradually from his rocking chair and steps with great deliberation toward the ball. No need to hurry this along. Old, weathered Curtis picks up the single…and you’re in for a treat here. It turns out it was a double all along! Curtis, a really pleasant sort when you chat with him, had no idea. The Mets, all of them really pleasant sorts, had no idea. Only that impressive young man Dansby Swanson knew as soon as he laid bat to ball that he’d wind up on second base. The youth and impressiveness of that impressive young man has to be beheld to be appreciated. It happened so fast, too. I timed it on the technologically advanced watch on my wrist here, so I can tell you exactly how long it took him to execute this unique feat of derring-do. Forgive my hesitation in retrieving this information, because I can’t seem to find my watch. It was right here on my wrist a moment ago..

Why, young Swanson seems to have made off with my valuable timepiece. Impressive!

All right, all right, then, impressive young Dansby Swanson is on second base and up steps…you know, it doesn’t matter. Mister Collins has arranged a nice, spacious hole for the next batter, who takes advantage as if scripted. The ball travels wide of the Met inner defenders and Dansby literally hops, skips and jumps between second and third bases before continuing on his impressive, young, merry way home. Michael Conforto deems himself so fortunate to have scooped up the ball in left field that he massages it in his glove repeatedly before opting to let it fly freely through the air. Well, by the time he delivers it to that d’Arnaud chap at the plate, Swanson has already crossed with the prevailing tally. The Braves win, the Mets lose. An unfortunate result if you are predisposed to dislike it, I concede, but witnessing the emergence of such an impressive young man on the level of Dansby Swanson was surely worth the price of admission. And, you know, with the secondary ticket market structured as it is, I paid only…wait, let me check…

Oh dear. Dansby Swanson seems to have picked my pocket while I wasn’t looking. What an impressive young man!

by Greg Prince on 9 June 2017 11:22 am Bergino Baseball Clubhouse proprietor Jay Goldberg possesses the wryest of wits. In graciously inviting me to pull up a chair and talk about Piazza: Catcher, Slugger, Icon, Star at his one-of-a-kind shop a few blocks south of Union Square, he offered me the date of June 15. We would discuss my new book, of course, “and given that it’s the 40th anniversary of one of the worst days for both of us, we would certainly discuss that, too.”

How do you dispute intuitive scheduling like that? The symmetry, I agreed, was too good to pass up, and thus I will be there (and hope you will be, too) this Thursday night at 7 o’clock. Not coincidentally, I told Jay, June 15, 1977, inhabits the narrative of Piazza like a ghost. I’m not sure a person, especially a Mets-loving person, could have grasped the concept of a superstar franchise player being traded in the middle of his prime in the middle of a season for blockheaded management reasons if it hadn’t happened before.

In May of 1998, it was the Dodgers who were the blockheads. In June of 1977, it was the Mets who made their fans cry good grief.

This guy made for a Terrific catcher. The story of Mike Piazza as a legendary Met is informed by the precedent of Tom Seaver in a couple of ways. One, most obviously, is that Tom represented the previously unreachable precedent which Mike, to our way of thinking, was striving to match. Everything that was said about Mike’s prospective Hall of Fame enshrinement and number retirement tended to be placed in the context of Tom. “First Met since…” “Only Met other than…” The Seaver standard served as a relevant emotional metric, and Piazza was, by consensus, the first Met to measure up. Nobody announced in advance that the final Shea Goodbye pitch would be Seaver to Piazza, but when the ceremonial battery formed, and 31 joined 41 as the only two Mets to walk through the center field gate, it made total sense to us.

Cosmically speaking, I’d like to believe it’s no accident that Tom Seaver’s Hall of Fame induction and Mike Piazza’s major league debut came within a month of one another, on the back end of the Summer of ’92. The fact that the former event occurred on August 2 and the latter September 1 — with the bridge between them thirty days of unrelentingly crummy Metsiness that foreshadowed the annus horribilis ahead and, ultimately, the several years of toxic-spill cleanup that 1993 would necessitate in Flushing — struck me as too good to be serendipity. It’s why I started the story of Piazza in Cooperstown with Seaver; shifted it to Shea for everything that was going wrong with the team Tom had long before legitimized; and then moved the focus to Wrigley Field the day the Dodgers promoted the kid catcher who’d hit .377 for San Antonio and .341 for Albuquerque.

Within the book’s first act, I also sought to establish how difficult it can be to cast in bronze an eternal identity once you start taking your talents elsewhere…or if somebody is sending you and them away. Seaver’s image for the ages was always going to be tethered to the Mets in our hearts and minds, and the record books testified it wasn’t just our imagination running away with us. Yet fate kept finding bad terms for Tom to leave New York on. You think Seaver was thinking kindly of his Mets association forty years ago next week when he found out he was about to call Southern Ohio his professional home? When he pitched against the Mets on eleven separate occasions? When he sat in the dugout opposite theirs with a world title hanging in the balance?

Given the “go in as a Met” topic that hovered over all our talk of Piazza before 75% of BBWAA voters made the inevitable a reality — and Mike made it crystal clear whose cap he’d be wearing forever after — I thought it would be instructive to examine for my book how much of a sure thing it was that Tom Seaver, the Met of Mets, would himself go in as a Met. My conclusion is that, as one of Tom’s managers might have put it, it wasn’t a certainty until it was a certainty.

What was certain was I had to cut certain sections of my manuscript for space, and the extended Seaver discussion wound up being one of them. In commemoration of the 40th anniversary of one of the shall we say most memorable days Mets fandom has ever known, and in anticipation of a much happier night at Bergino Baseball Clubhouse, I decided to share what I wrote here.

***

Conceivably, it could have looked different, though there was a time that itself was inconceivable. That time was prior to June 15, 1977, a date destined to live in infamy among Mets fans of a certain age. It was the day Tom Seaver was traded to Cincinnati.

It never should have happened, not if you believed that some players and some teams were made for one another. Tom had been a Met for more than a decade by then, most of it under the ancient system in which ballplayers played ball and management did with them what it wanted. Then came free agency and, with it, the chance for ballclubs and ballplayers to improve their respective lots. Seaver wasn’t happy with how his club was running its affairs — shunning the opportunity to enhance the offense behind him — and he didn’t care for his suddenly outdated compensation package. In a nutshell, the man he worked for, Mets chairman of the board M. Donald Grant, didn’t care for what he considered Seaver’s uppity attitude.

The match made in heaven in 1966, when a pitcher’s name was pulled out of a hat in a special lottery on behalf of a franchise desperate for a transcendent figure, was on the verge of dissolution. The Mets had gotten lucky when Seaver’s original professional contract was voided by then-Commissioner Spike Eckert. Twenty-one year-old Tom, from the University of Southern California, found himself in a murky void, caught between the pro team that drafted and signed him, the Atlanta Braves, and USC, where his amateur status hadn’t fully worn off. The Braves couldn’t keep Seaver, but Seaver, it was decided, couldn’t be kept from pursuing his career. Thus, the lottery that every team besides Atlanta was invited to join, yet only three did: the Cleveland Indians, the Philadelphia Phillies and the New York Mets. All it took to get him was a willingness to match the $51,500 bonus the Braves had planned on paying him and fate.

Fate sided with the Mets. It was their name on the slip of paper Eckert drew from the most charmed hat in Mets history. They got Seaver. Seaver went to Triple-A Jacksonville for a year, then made Flushing, Queens, major league a year later. The team that had never finished higher than ninth prior to Seaver’s arrival…well, they finished tenth with him, but one could only recoil at imagining where they might be headed without him. Fortunately, for ten years, the Mets never had to seriously contemplate such a question.

Seaver pitched. The Mets improved. Hodges, beloved Brooklyn Dodger and Original Met, came home to manage him and Harrelson and Koosman and Grote and a clubhouse of young players who possessed talent but craved guidance. Gil guided. The Mets improved exponentially. Seaver excelled. The Mets followed suit and won a world championship in 1969 that could hardly be fathomed and would never be forgotten. Then the Mets leveled off. Seaver didn’t. He kept pitching and kept excelling. His right arm was as strong a reason as any that the Mets stitched together another pennant, this one under Berra, in 1973. Through a torrent of innings and a paucity of runs and even in the aftermath of the tragic death of his professional mentor Hodges, Seaver kept going.

In the spring of ’77, though, he was going out the door. Trade rumors began to boil over that spring. The pot was stirred to excess by Grant’s ally, the legendary Daily News columnist Dick Young. Young invoked a supposed jealous streak Tom’s wife Nancy maintained toward Nolan Ryan’s wife Ruth. Ryan, the Met foolishly dealt to the Angels half-a-dozen years earlier, had grown into a star pitcher in California. Young’s story had it that Nancy Seaver was upset Ruth Ryan’s husband was getting paid more than her own. Tom didn’t care for this tactic whatsoever. His demand to be traded was set in stone. Late on deadline day, June 15, he went to Cincinnati in exchange for four players who weren’t and never would be the equivalent of one Tom Seaver.

“As far as the fans go, I’ve given them a great number of thrills,” an uncharacteristically emotional Seaver told reporters in front of the locker he was compelled to clean out, “and they’ve been equally returned.” It was a transactional assessment, but it was also correct.

The Mets were back where Seaver found them when he joined them: in the cellar. They struggled in his absence. They might have struggled anyway, given Grant’s aversion to modernity. The organization was rotting from within. No viable reinforcements were graduating from the minors and no significant help was being obtained on the open market. The Mets of the late 1970s were probably doomed with Seaver or without him. But the Mets without Seaver, on principle and on the field, were unbearable.

Tom thrived in Cincinnati, no matter how odd his familiar form appeared trimmed in red. He pitched a no-hitter for his new team. He pitched them into the playoffs once, to the best record in baseball another time…but not the playoffs, amid the bizarre split-season contrivance of strike-sundered 1981 (a baseball version of the electoral college trumping the popular vote). Wear and tear was finally showing on him in 1982, his sixth season with his second club. The Reds, rarely less than very good for a generation, had finally stopped winning. They didn’t necessarily need to continue paying an all-time great starting pitcher whose every-fifth-day effectiveness was ebbing.

The Mets had undergone many changes in Seaver’s absence, though you couldn’t tell it by the National League East standings. They continued to dwell near the bottom of them, but behind the scenes, things were very different. Grant was gone. The team had been sold. The new owners hired a general manager, Frank Cashen, determined to overhaul the entire operation. Cashen was building from within, drafting and nurturing a contender, occasionally shelling out for external help to patch over the rebuilding process. In the winter heading into ’82, he did some headline-grabbing business with Cincinnati, taking off their hands the bulging salary demands of George Foster, an RBI man of the highest order. It was a crowd-pleasing move. That it didn’t work out — Foster’s production couldn’t have diminished any faster had that been the plan — didn’t mean it wasn’t a good idea. Rebuilding was taking its not-so-sweet time. The goodwill attached to the 1980 regime change faded almost as quickly as Foster’s talent for driving in runs. Nineteen Eighty-Two marked the sixth consecutive year of the Mets holding down one of the two lowest spots in their division. A diversion couldn’t hurt.

Especially one that could still pitch a little.

Five-and-a-half years after the unthinkable trade of Tom Seaver from the Mets, Tom Seaver was traded to the Mets. All was right with the world again, save for the standings. The Mets remained well south of contention as 1983 dawned, but finishing last with Seaver loomed as so much more pleasant than finishing last without him. Opening Day told the story beautifully. Shea Stadium was packed. Public address announcer Jack Franchetti introduced “Number Forty-One” as the starting pitcher. No more needed to be said. Tom Seaver, in his native colors of blue and orange, strode down the right field line from the home bullpen. He stepped on the mound and threw to Pete Rose, these days a Philadelphia Phillie. His first pitch was a strike. His return was a home run.

Seaver the second-time Met was a phenomenon. Then it was just how it was supposed to be. Tom’s presence blended into another sixth-place finish. He still pitched well, but the team still didn’t score much for him or any of its pitchers. The losing continued. Cashen continued to conjure. The Mets’ slogan, when they were sold to a group headed by Nelson Doubleday and Fred Wilpon, was “The Magic is Back.” That prematurely ballyhooed wizardry was about to manifest itself for real.

In May, the Mets promoted Darryl Strawberry, the first draft pick Cashen had made for the Mets. Strawberry probably wasn’t yet ripe, but the season wasn’t producing a bumper crop of wins. Darryl could learn in New York as well as he could in Tidewater. In June, on the sixth anniversary of the Midnight Massacre that made Seaver an ex-Met, the GM stunned baseball by making Keith Hernandez an ex-Cardinal. Hernandez was an in-his-prime Gold Glove first baseman and clutch hitter. He was exactly the kind of player Seaver lobbied the Mets to acquire when free agency dawned. Cashen all but pulled him out of a hat — more magician’s than commissioner’s — giving up two young pitchers he could do without. St. Louis didn’t want Keith any longer and New York didn’t particularly care why.

Last place wouldn’t be escaped in 1983, but by August, the Mets no longer looked like long-term occupants. Strawberry was learning. Hernandez was getting comfortable. Others were coming around. Seaver was Seaver. A team on the rise and a legend in residence. For the first time since Tug McGraw implored a city to Believe, Mets fans had the sense they really could, and not live to regret it.

Then they were consigned to a sickeningly familiar state of disbelief. Tom Seaver, missed for so long, welcomed back so warmly, was gone again. It wasn’t as ugly as the first time it happened, but it was awful enough. This time, the culprit amounted to a whopper of a clerical error. That strike that cost Seaver’s Reds a postseason berth in 1981 yielded a strange compromise between players and owners called the compensation pool. In essence, if Team A signed a free agent from Team B, Team B was entitled to pick a player from Team Z, a.k.a., a team that was otherwise uninvolved in the initial transaction if Team B so chose.

For example, the Toronto Blue Jays opted to engage the services of pitcher Dennis Lamp, previously of the Chicago White Sox. The White Sox, under the terms of the Basic Agreement, were allowed to seek compensation from a pool of players left unprotected by everybody else. Floating in that pool was a 39-year-old pitcher who had just had a pretty good season for a last-place team. Because of his age, let alone his symbolic importance to his team, he seemed like the kind of player another team would leave alone.

The Mets protected the names that represented their immediate future in that compensation draft. They weren’t going to expose a Strawberry or a Hernandez or any of the youngsters who had just arrived or were on their way. A veteran like Tom Seaver, however, seemed safe enough to not technically guard. Who would dare pluck the Mona Lisa from the Louvre?

If the Louvre was careless enough to leave its doors unlocked, the Chicago White Sox, that’s who. They went for the masterpiece of veteran pitchers, Tom Seaver. Without warning, without an M. Donald Grant or a Dick Young stoking the tabloid fires, Seaver was again an ex-Met.

If January 20, 1984, the day Seaver’s contract was transferred to Chicago’s American League entity, didn’t live in infamy, it resided not too far down the block from June 15, 1977, in the same neighborhood of dates and events that made Mets fans shudder to their core. On both occasions, the Mets rolled out the moving van and packed their greatest player ever off to a distant city. It wasn’t as obnoxious or as obvious as what happened amid the Grant-Young maneuvers that sent Seaver to Cincinnati, but the result was the same. Tom Seaver was no longer a New York Met.

In short order, as conspiracy-theorists wondered just how much of an accident Seaver’s departure really was, the New York Mets revealed themselves as no longer a last-place ballclub. All of Cashen’s planning and planting began to pay off in the summer ahead. Under a new manager, Davey Johnson (who may or may not have wanted a strong figure like Seaver exerting influence inside his youthful clubhouse, if you bought the conspiratorial thinking), the Mets challenged convincingly for the NL East title in 1984 until the season’s last week. They challenged even harder in 1985, falling heartbreakingly short on the last weekend. Then, as if it had been marked as the destination on their road map all along, they blew the doors off the division in 1986 en route to winning their first World Series since 1969.

It would be simple enough to say that after a while, Mets fans didn’t miss Tom Seaver, not when their ballclub was leaping from 68 wins to 90 to 98 to 108 and the brassiest of brass rings, yet that is to not fully appreciate fan loyalty. Sure, there is the uniform, and there is the cap, and there is a fealty to success. The fan can be guided by the same transactional impulses as front office architects and free agent players.

But some things you don’t take away and expect to go unmissed. You don’t take away a first love. You don’t take away a first star. You don’t go to the trouble of bringing back the FRANCHISE POWER PITCHER WHO TRANSFORMED METS FROM LOVABLE LOSERS INTO FORMIDABLE FOE only to let him go a year later. You also don’t not notice that Tom Seaver, who left New York the second time with 273 career wins on his ledger, wore garish horizontal stripes and a shirt that screamed SOX on the hallowed occasion of his 300th victory. It took place in New York, in front of Mets fans, but the Mets fans were one-day visitors to Yankee Stadium, same as Tom. The milestone was a fine moment, but it was also indicative of a right arm that was still churning out productive pitches. During the season of No. 41’s No. 300, the Mets were battling St. Louis for first place. Seaver was in the process of winning sixteen games for the White Sox. The Mets finished three games behind the Cardinals. The math suggests those wins of Tom’s would have looked much more attractive adorned by Mets gear. The 1985 Mets were formidable foes on most fronts, yet relied on soft-tossing Ed Lynch and still-learning Rick Aguilera for starting pitching depth down the stretch. They weren’t terrible, but Tom was still Terrific.

When Seaver, having reached the age that he’d been wearing on the back of his jersey since he was 22, requested another trade, in 1986, it was to be closer to his home in Connecticut. The Mets didn’t need much of a boost that season, so he was off to Boston, mentoring a meteorically rising righthander named Roger Clemens (“At home, I’ll tell him what time the game starts. On the road, I’ll tell him what time the bus leaves,” is how Tom described the extent of his guidance) and helping another team to the playoffs until his right knee, the one that absorbed dirt from the pitching mound when his motion was ideal, gave out in September. Tom was forced to sit inactive in the dugout during the ensuing World Series at Fenway Park and, yes, Shea Stadium. Seaver the Red Sock was a footnote to the circumstances of the Mets’ second world championship seventeen autumns after he was the heart and soul of the first one. Had he, instead of sacrificial lamb Al Nipper, been available to pitch for Boston in Game Four, it could be legitimately wondered whether the Mets would have won that second world championship when they did.

Seaver versus the Mets in the World Series…shudder.

Desperation less than fate boomeranged Seaver to Flushing the following June. His recovery, along with more ownership shenanigans — collusion had squeezed the free agent market of its usual brisk high-dollar activity — seemed to quietly end his career. But the Mets, trying to defend their title, were short of starting pitching. Injuries were taking a toll, and there was a spry gent up the road in Greenwich who knew how to get hitters out and was quite familiar with the route to Shea. The Mets and Seaver reunited one more time, conditionally. Tom would have to pitch his way into shape. He and they would have to be convinced that at 42, No. 41 could still do what he’d been doing all those years before.

It didn’t work out. Seaver started an exhibition at Tidewater for the Mets. He didn’t look great. He pitched what were called simulated games, throwing his best stuff to a cadre of bench players. He didn’t look right. Backup catcher Barry Lyons in particular wracked him around. If Seaver couldn’t handle little-known Lyons, what were the chances he could tame the Hawk, Andre Dawson, or the Cobra, Dave Parker? Finally, on June 22, 1987, at a press conference called not because of a feud with a feudal-minded executive and not because of a too-clever-by-half paperwork omission, Tom Seaver and the Mets parted ways, at last more or less on the same page. Their relationship was described as strained in the press — Cashen and Johnson were by no means Grantlike villains, but they hadn’t exactly fallen over themselves to keep Tom on their team when he still had some competitive pitches left in that right arm. Yet in front of the cameras and microphones, only the most conciliatory of sentiments were uttered. “The single most important player in the history of the Mets,” the GM declared, was “retiring as a Met.”

Considering how rarely any player retired as a Met, it was more of an achievement than face value would imply. Rusty Staub received a knowing ovation on Closing Day 1985. Otherwise, Koosman ended with the Phillies, Harrelson (before returning to Shea to coach) played his last games with Texas, Grote bounced to Los Angeles, then Kansas City…and so on. Cleon Jones went out with the White Sox, Tommie Agee faded away as a Cardinal, Ed Kranepool was allowed to walk and keep walking after parts of eighteen seasons as a Met — the first eighteen seasons there were Mets. If Tom Seaver couldn’t pitch any longer as a Met, then retiring as one was the next best resolution in light of the wary ride the Franchise and the franchise had intermittently shared over the previous decade and change.

Seaver’s 41 had been out of circulation since the end of the 1983 season. Nobody wore it in Queens during his Cincinnati exile, either. Cashen announced the number, like he who wore it so elegantly, would be retired. That ceremony would wait a year. The Hall of Fame would wait five. Given the firmly established rapprochement between former pitcher and old team, there could be no doubt that Tom Seaver would enter that august institution embodying the New York Mets. The statistics wouldn’t have it any other way and there was no discernible reason for the twice-spurned Seaver to want it any other way.

It would be a first. Since the founding of the Mets a quarter-of-a-century earlier, several men with blue-and-orange ties had gained Cooperstown induction: Warren Spahn, Willie Mays, Yogi Berra and Duke Snider as players, Casey Stengel as a manager, George Weiss as an executive. None, however, was in primarily by dint of what he accomplished as or with the Mets. Ralph Kiner remained on the BBWAA radar for a necessary fifteenth ballot, his last eligible year to be voted on by the writers, perhaps because he was a highly visible Mets broadcaster, but it was Ralph’s production as a Pittsburgh Pirate that finally earned him election in 1975. Lindsey Nelson came to be so closely identified with the Mets between 1962 and 1978 that Yankee outlet WPIX-TV enlisted his services on August 4, 1985, to call Seaver’s 300th win. Nelson received the Ford C. Frick Award in 1988, Cooperstown’s paean to excellence in broadcasting. It was a substantial honor, but not exactly the same as being elected to the Hall (and Lindsey was a national broadcaster of considerable renown before and outside his work with the Mets).

Tom Seaver went into the Hall of Fame in 1992 because of what Tom Seaver did as a Met. It was all enshrined so as to be marveled at: 198 of 311 wins; 2,541 of 3,630 strikeouts; all of his Cy Youngs; his only World Series ring; and, if you still weren’t sure, the NY on the cap on the plaque. That couldn’t be traded for Pat Zachry, Doug Flynn, Steve Henderson and Dan Norman, and it couldn’t be left exposed as potential compensation because Dennis Lamp lit out for Canada.

***

Out in California, Tom recently received a visit from Bill Madden, who wrote about it in the Daily News. If you wish to catch up with the greatest vintner to ever toe a big league rubber, you can read about it here.

The recent passing of Frank Deford brought to mind a profile the acest of ace reporters wrote for Sports Illustrated in 1981, while Seaver’s Reds “best record in baseball” campaign was on hold due to the summerlong strike. It captures a fascinating moment in time for a Met in exile. I recommend you click here and read it.

To reiterate, I will be joining Jay Goldberg at Bergino Baseball Clubhouse, 67 E. 11th St. in Manhattan, to discuss Piazza: Catcher, Slugger, Icon, Star, Thursday night, June 15, 7 PM. No doubt Tom Seaver will come up. No doubt, also, that Jay will put that night’s Mets game on in the store once the official chatting winds down. Copies of my book will be available from Bergino and I’ll be happy to sign. I really do hope you’ll swing by. The details are here.

by Greg Prince on 8 June 2017 10:05 am My preferences have little impact on determining the outcome of baseball games I sit down to watch, or maybe you’ve noticed the unbroken winning streak the Mets haven’t been on for the past five decades. Nevertheless, I decided I was going to be reasonably content with a Mets loss Wednesday night provided Zack Wheeler and I got out of it what we needed. We didn’t need Yu Darvish mowing down the Met lineup, but I took that as a given. What wasn’t so obvious going in was what Zack would do. In 2017, we’ve learned to expect nothing from Mets starting pitching. Get any more than nothing, and how can you not be sort of satisfied?

Darvish was Darvish for the first nine Met batters, each of whom politely took a turn and made an out across the first three innings. Wheeler was the Wheeler we anxiously clench our fists over in his initial inning on the mound. We don’t shake these fists, but we do clutch our anxieties inside of them. How many balls, Zack? How many baserunners? How many gosh darn pitches you gonna throw? For other Met starters, the pitch count might get your attention if it appears alarming. For Zack, we automatically keep track.

The bottom of the first in Arlington was vintage Zack, which is to say borderline agony. Four pitches for a single. Six pitches for a walk. A first-pitch single to Elvis Andrus, which was good news/bad news. Only one pitch and the runners only moved up a base, but oy, the bases are loaded, nobody is out, Zack is in trouble. After Jacob deGrom, the putative ace of the staff, was shellacked the night before, how could the bad news not overwhelm the good news in a matter of pitches?

Wheeler would answer. He’d need six pitches to produce a fielder’s choice groundout that scored the first Texas run, and then exactly one more for a double play grounder that curtailed the damage. Every other Mets pitcher, I’d be thinking, all right, we gave up one run. With Wheeler, I was an adding machine: let’s see, eighteen pitches…if he can rein it in, he can go at least five, maybe six.

Count Zackula had me paying less attention to my fingers and toes as the innings went by, because it was no longer about how many pitches he was throwing, but how well he was throwing them. That he did very well. Zack was in command in a way I’ve seen few Mets steer a start this year. He knew what he was doing on the inside of the plate. He fooled Texas hitters when he had to. He was economical, even. He was what he had to be, maybe what he is about to be. Six years since he was traded to the Mets and hailed as an ace-in-waiting, perhaps his future has arrived.

Zack Wheeler is the best starting pitcher the Mets have right now. Until his start against the Rangers, that was by default. For the moment, in the wake of a start where he got better the longer he went, it is a title rightly bestowed. Zack gave the Mets seven full innings on 108 pitches. Over the final six he threw, he allowed only four hits (three of them singles), two walks and no runs. He transcended serviceable and veered toward masterful.

Darvish, meanwhile, continued to be very good, but decidedly imperfect when it came to facing, if you’ll excuse the expression, the Mets’ designated hitter, Jay Bruce. For the first eight innings, our gloveless native Texan was also our lone star on offense, belting two home runs, one with a man on. We had a 3-1 lead through seven marvelous Wheeler innings. The outstanding outing I’d hoped for didn’t have to be mutually exclusive from defeating Darvish.

As long as they insist on silly rules in American League parks, maybe we could have ended it there, neat and tidy. But no, junior circuit baseball encompasses nine innings, however bastardized their lineups, so it came to pass that when Wheeler was removed and Jerry Blevins entered, the game was still up for grabs. Alas, in the bottom of the eighth, good ol’ Jer’ gave up a single to Nomar Mazara and a home run to Robinson Chirinos. This revolting development fit snugly within the prevailing sense that nothing ever goes right for the Mets, yet somehow I didn’t feel overly distressed about the bottom line. Wheeler was still wonderful during his seven innings. No, they couldn’t take that away from him. Or me.

And, surprise of surprises, the Mets didn’t proceed to find a way to lose. Blevins got out of the eighth and the Mets did something constructive with the ninth. With one out, Lucas Duda doubled authoritatively down the right field line off Matt Bush and immediately gave way to pinch-runner Matt Reynolds. With two out, Curtis Granderson patiently elicited a seven-pitch walk after being down oh-and-two to the Rangers’ closer. Jose Reyes, whose major league career commenced in this very same facility fourteen Junes and who knows how many corporate identities ago, was up next, attempting to wring a little more life from what remains of his professional tenure. Jose has earned his way to the bench, but he was in the lineup Wednesday night. Prior to the ninth, he’d done little to liberate himself from the pine on a going basis, par for the sad course of late.

On Tuesday, SNY showed a delightful flashback to the evening in 2003 when a highly touted 19-year-old shortstop alighted in Arlington to make his Met debut, the Amed Rosario of his time, you might say. You couldn’t miss the smile or the potential on Kid Jose. Then the 2017 camera spotted a reserve infielder, on the edge of 34, sitting forlornly in the dugout, not hitting, not happy. You could have penciled in your own thought bubble of despair. Jose’s looked slow in the field, lost at bat and head up his ass jogging to first, but — and this is not intended as faint praise — he still appears to be a helluva teammate. When another Met scores, he’s the most animated of fans. He greeted Bruce like a brother when he went deep. He does it with everybody. Nobody is more ebullient in congratulating a colleague, nobody seems to enjoy his fellow Mets’ successes as much. It reminds me warmly not only of vintage Jose from 2006 (when he was regularly on the receiving end of enthusiastic handshakes and hugs), but of the late summer of 2016. It wasn’t so long ago that Reyes was hailed as the veteran team leader, he and Asdrubal Cabrera praised for getting and staying on Yoenis Cespedes, and the three of them setting an example for all to Do Your Thing, as the clubhouse slogan went.

We haven’t seen much of Cespedes lately; Cabrera of these days isn’t the Cabrera of those days; and Reyes is back to craning his neck to get a gander at .200. You can’t as effectively urge others to Do Their Thing when you can’t do a thing at all.

As the ninth unfolded, I had the sense it would be slumping Jose up with the game on the line, aging Jose in the spotlight in the stadium where it all began for him. I had a sense Granderson would find his way on base to unintentionally pass the buck, the baton and the responsibility for Wednesday’s result to Reyes. I had no sense of whether this would be good for him or us. On instinct, I stood and I paced in small circles as I don’t think I’ve done before this season. It hadn’t previously seemed worth the trouble.

On a two-oh pitch, Jose lined a ball past Bush. Could he have actually driven in the go-ahead run? The liner up the middle wasn’t struck terribly hard and the Ranger defense was positioned to corral it. From the outfield grass to the right of second base, Rougned Odor picked it off the ground on one hop. It was a just difficult enough play to make so that Odor wound up bouncing his throw to Andrus, covering second. Andrus went about gathering it in ahead of Granderson’s slide. With Elvis’s back to us and his glove obscured by his body, it looked like Curtis was going to be out to end the threat and the inning.

Looks were deceiving. Texas’s shortstop had a hotter potato on his hands than we at home could discern. Slowly but assuredly, second base umpire Chris Guccione determined Andrus never fully controlled the ball before dropping it altogether. As Guccione went about declaring something had gone horribly awry for a Mets opponent for a change, Reynolds — too callow to know any better — kept running until he crossed home plate. Replay review was deployed, but to no avail for the Rangers. The Mets led, 4-3, on a modestly vexing fielder’s choice facilitated by a .187 hitter who came through barely by not coming up empty.

Buoyed by the unlikely circumstance of some other team imploding to the Mets’ advantage, Addison Reed retired the Rangers in order in the bottom of the ninth. Reed recorded his ninth save, Blevins — whose gopher to Chirinos rendered Wheeler’s effort non-decisive — his third win. It was every bit the W that Clayton Kershaw was awarded earlier Wednesday for going seven and fanning nine in vanquishing Washington. Kershaw pitched lengthily and brilliantly. Blevins had a bad blip that negated Wheeler’s efforts within the box score. Yet Kershaw and Blevins were both victors in the ancient statistical sense. Assignation of pitcher wins can be as ridiculous as the designation of a player to do no more than hit and sit, but when it all works out for what we consider the best, we’ll quietly ride our high horse out of Texas with a split in our saddle bag and try not to raise too much of a ruckus regarding what we find objectionable in the details.

Between you and me, though, pitcher wins are rather inane and the DH remains an absolute travesty.

For one ultimately pleasant evening, the Mets paused their ongoing re-enactment of 1974, the year this year is most reminding me of (also, the last year I paid rapt attention to the Texas Rangers). Nineteen Seventy-Four represented the comedown from the adrenaline rush of 1973. The only significant change those Mets made after their near-impossible surge into the postseason was cutting ties with an iconic quadragenarian. The post-Willie Mays Mets were stuck in the kind of mud these Mets, post-Bartolo Colon, have been. After 57 games in 1974, the Mets were 23-34. After 57 games in 2017, the Mets are 25-32. Wayne Garrett, a .422 hitter down the ’73 stretch, was batting .176, eleven points lower than Reyes. Tom Seaver’s ERA was 3.61, which for 1974 — and Seaver — was as unsightly as 4.75 is for deGrom. Hell, Tom, following his second Cy Young season, had only three wins…or as many as Blevins does at present.

One September’s inspiring heroes were the next June’s mere mortals. The pitching didn’t nearly match its reputation. Roster replenishment was mostly eschewed. Sound familiar? For what it’s worth, those Mets had no You Gotta Believe encore in them. They were in fifth place and eight games out of first at this juncture 43 years ago en route to finishing in fifth, seventeen behind the division-winning Pirates. The only NL East team the Mets led after 57 games in 1974, however, was that very same Pittsburgh crew, which wallowed nine games from first. Like the Mets the season before, they didn’t lay down and die just because they were pretty much dead. Not every cause apparently lost in June stays irretrievably lost until October. If you choose to Believe as we did in 1973 and 2016, you may wish to take note that the 2017 Mets are, as of today, nine games out of a Wild Card spot.

Nah, I’m not buying it, either, but you never know.

You are cordially invited to Bergino Baseball Clubhouse on Thursday, June 15, 7 PM, where I will be discussing my book Piazza: Catcher, Slugger, Icon, Star and other matters related to New York Mets history. Details are here. I hope to see you there.

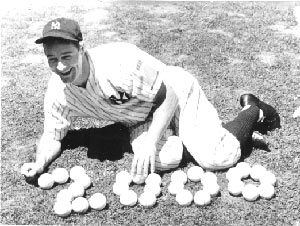

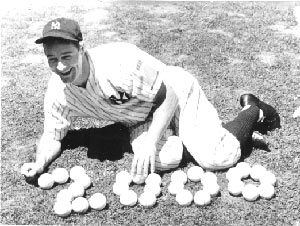

by Jason Fry on 7 June 2017 12:56 pm Hmm, is that how you spell Milestone Achieved? It looks a little funny, but there’s no wavy red line under it, so I guess it must be correct.

As you may have heard, Tuesday’s night game — played in whatever suburb of Dallas that’s considered to be in whatever that park that looks perfectly new but is soon to be replaced is called — was the 2,000th in a row we’ve chronicled here at Faith and Fear since the winter day we decided to celebrate the inauguration of the Carlos Beltran era by exchanging our thoughts about the Mets in a public forum instead of in extremely long emails.

Whether or not you’re talking baseball, milestones are rarely particularly interesting in themselves — the significance is in what’s come before, not what’s occurred in the moment. There are exceptions — Derek Jeter comes immediately and apologetically to mind — but most 3,000th hits are singles necessitating a pause in run-of-the-mill games, most 300th wins are corralled by bullpens while everyone waits impatiently, and lots of playoff spots are secured on the road before a few temporarily nomadic loyalists amid indifferent home crowds.

So no, we didn’t get a second no-hitter, four home runs from an unlikely source, or anything like that. We didn’t even get Gary Cohen — though vacation play-by-play guy Scott Braun’s only sin was being unfamiliar, which is more about us than his work alongside Ron Darling.

What we did get was an all-too-typical 2017 Mets loss: more hitting than you might expect, bafflingly horrific starting pitching, inadequate defense and an extra twist of the knife in case you’d forgotten what an utter drag this season has been.

Jacob deGrom was terrible again, offered a consoling arm after his removal by Terry Collins and later insisting to reporters that he feels fine and doesn’t know what’s wrong other than location and pitches doing nothing, which is more than enough to ensure a bad day. The defense behind him was execrable in ways big and small, with Met fielders just missing converting some difficult plays and quietly botching some not-so-difficult ones. The bats put up big numbers in the box score, but left a bushel of runners in scoring position. Of course there was a ferocious ninth-inning attempt at a comeback that got you a bit excited despite knowing better. And of course that comeback fizzled, with a game-ending double play coming as a petty, mean-spirited coup de grace.

What’s to be done with this team as we ponder recaps 2,001 and up?

Sports Illustrated’s Jay Jaffe recently looked at the Mets as one of the teams that has to decide whether or not to sell, and noted that a Mets sale could net a pretty good return: Jay Bruce, Lucas Duda, Neil Walker and Addison Reed are all pending free agents who would be among the best options at their positions for playoff-hunting clubs, while Asdrubal Cabrera is signed through next year and could be moveable. Hell, someone might be even persuaded to take a flier on a couple of months of Curtis Granderson and/or Jose Reyes.

Surveying that list, my reaction is: Goodness, trade as many of them as you can. Bruce, Duda, Walker and Reed might net a couple of actual prospects, or at least some interesting lottery tickets. Both Amed Rosario and Dom Smith look ready to try their hand at the big leagues, and are a week or so away from escaping Super 2 status. Rosario would immediately help the Mets’ infield defense, taking some of the pressure off the pitchers. Once Yoenis Cespedes returns — as stubborn hope insists he will — the Mets will be back to trying to solve a corner-outfield logjam.

Most significantly, a summer sale wouldn’t be a long-term rebuild but a short-term reload. Even without factoring in returns on trades or potential winter acquisitions, Rosario and Smith would join a lineup that would still feature Cespedes, Michael Conforto and Wilmer Flores (who’s somehow still only 25). They’d get more time to find their big-league footing without being treated as saviors. And you’d be returning all the starting pitchers, with fingers crossed for better health and luck.

I’d be intrigued by that team for the rest of 2017. I’d be eager to see what they could accomplish in 2018. Maybe they could even help the Mets attain milestones instead of millstones.

by Greg Prince on 6 June 2017 3:11 pm The Mets winning 11 games in a row.

Dwight Gooden winning 14 games in a row in one season.

Tom Seaver winning 16 games in a row over two seasons.

Tom Seaver striking out 200+ batters a year 9 years in a row.

Tom Seaver striking out 10 batters in a row to finish a game.

Jacob deGrom striking out 8 batters in a row to begin a game.

R.A. Dickey pitching one-hitters 2 starts in a row.

Turk Wendell pitching in 9 games in a row.

Moises Alou hitting in 30 games in a row.

Mike Vail hitting in 23 games in a row as a rookie.

John Olerud reaching base 15 times in a row.

Richard Hidalgo homering in 5 games in a row.

Mike Piazza recording an RBI in 15 games in a row.

Jose Vizcaino recording a hit in 9 at-bats in a row.

Rusty Staub recording a pinch-hit in 8 pinch-hit at-bats in a row.

Jeurys Familia converting 52 saves opportunities in a row.

Jose Reyes playing in 200 games in a row.

And, barring uncooperative weather, electrical shenanigans or some other stripe of catastrophe in the hours ahead, Faith and Fear recapping 2,000 regular-season Mets games in a row.

He was referred to as the Iron Horse, yet how many games in a row did Lou Gehrig blog? You read that right, if you read it all. We are on the cusp of FAFIF 2,000 (or F2K). There’s Cal Ripken, there’s Lou Gehrig, and then there’s us, if you’re not too picky about what actually happened in our respective consecutive games played/blogged streaks.

Some Mets streaks are more famous than others. Anthony Young’s streak of 27 losses in a row may be the most famous of them all, but it wasn’t delightful. Jose-Jose’s all-time Mets best games-played streak from 2005-2006 isn’t famous at all (even I had to look it up), but it does get at the consistency inherent in our heretofore unknown streak. How obscure is FAFIF’s run at 2,000? You’ve just now heard of it. Jason only heard of it last week when I told him about it, and he’s one of the two bloggers responsible for it. Nevertheless, this streak is real and it is spectacular. Or maybe it’s just real. I don’t know. We started a blog before the beginning of the 2005 season, we recapped the first game (a loss), we recapped the next game (a loss) and we kept going until suddenly we were up to 1,999 on Sunday (a loss).

Contrary to the impression I’ve crafted directly above, they haven’t all been losses. The Mets’ record since we’ve taken it upon ourselves to have something to say out loud about every game they’ve played is 1,011 wins and 988 losses. That, like Jeurys’s streak, takes into account the regular season only. For the record, we’ve recapped 25 postseason games in a row. We’d be happy to recap more of those.

We don’t know when more of those will be available. We do know a game between the Mets and Rangers is scheduled tonight and, should it be played to a decision, we plan to tell you our thoughts about it sometime between its final out and the first pitch of the game after it, which projects as the 2,001st in our streak.

Not to get ahead of ourselves. As has been the case since April 4, 2005, we blog ’em one game at a time.

|

|