The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 29 September 2011 2:37 am It wasn’t long ago that I was a fan of a franchise that never had a batting champion but was saddled with the Worst Collapse Ever. Neither is my problem anymore.

The Mets still Collapsed with a capital C in 2007, but it was a stumble in the park compared to what we as a baseball-loving people have just witnessed from the Braves and the Red Sox. THUD! THUD! And the way they thudded! Jesus…and I don’t mean Alou.

The series of events that had to unfold to dislodge two surefire playoff teams from the postseason before they could ever get there was mind-boggling enough before the final night of the schedule. Then the boggled mind rocketed into the stratosphere. Braves blow lead in ninth, lose in thirteen to Phillies after Cardinals rout Astros. They were up by 8½ on September 6. They’re behind by 1 now.

How did this happen? Easy: the Mets beat the Braves twice down the stretch while they chose to beat the Cardinals only once. We determined this Wild Card race, obviously. And good for us, for while I hate the thought of the Cardinals, I detest the sight of the Braves. Something to do with repeated exposure and Fredi Gonzalez.

The National League change of fortunes was incredible, yet it rather paled by comparison to what happened in the American League, certainly on the final night. You knew the Red Sox were tumbling and you figured the Rays could take advantage, but still…

• A six-run eighth to pull the Rays from 0-7 to 6-7.

• A two-out homer from Dan Johnson in the ninth off whoever was pitching for Scranton/Wilkes-Barre to tie it at seven.

• Jonathan Papelbon having Omir Santos flashbacks in the ninth at Baltimore.

• Carl Crawford proving Carl Crawford money can’t necessarily buy you glove.

• Evan Longoria. The twelfth inning. The Red Sox out. The Rays in.

Holy crap.

There’s probably some very good reason to credit the Rays and the Cardinals for their late elevation into the playoffs, but as in 2007, this doesn’t feel like it’s about those who rose up. It’s about those who fell down.

Glad somebody else fell farther and faster than we did. I wouldn’t even say it’s the usual Sheadenfreude making me giddy. It’s nothing personal against the Red Sox (up 9 on September 3), and it’s not even about traditional antipathy for Atlanta. I’m not happy it happened to those teams. I’m just glad it happened to somebody else.

As for that batting championship, congratulations to Jose Reyes, no matter how unideal the denouement of his chase turned. When he bunted his way on to lead off Closing Day and ramp his average up to .337, I jumped in the air and clapped. My feet weren’t yet on the ground of Section 108 and my palms hadn’t yet fully separated before I saw Justin Turner trotting to first from the dugout.

They’re taking him out? Is something wrong with him? He looked fine beating out the bunt. Why is Terry doing this? What’s his bleeping problem? He had talked about not playing him at all, and now you give him only one at-bat in what might be his last game ever as a Met?

Wednesday marked my 17th consecutive Closing Day (a.k.a. final regularly scheduled home game of the year), my 19th overall. I hold Closing Day sacred. I can miss Opening Day. I can’t miss Closing Day, not if I can help it. A year ago I stuck it out into the fourteenth Oliver Perez-riddled inning and would have stuck it out fourteen more if necessary. I don’t understand how anybody comes to the last baseball game of the year and leaves early.

But honestly, after Reyes left the field, I wanted to follow him. If I was at the game alone, I would have left. As it was, I sank into a snit that lasted the second, the third and the fourth. I had to get up and walk away from my seat and imbibe a Blue Point Toasted Lager to calm me down.

Eventually I got over how weird it was that Jose would be pulled, even if it was in the service of the batting crown, which I desperately wanted for him (and for us). The night before, the fella I was with asked me if I could have only one choice between a Mets win and Jose taking the collar, or a Mets loss in which Jose goes 5-for-5, which would it be? After remarking how this seemed like the kind of decision fans of certain other teams probably don’t mull, I didn’t hesitate with my answer: Jose, 5-for-5, batting title. On Tuesday night I was en route to losing “my” fifth in a row at Citi Field, and all I cared about was that Jose homered twice and gathered up three hits altogether. I’d gladly sacrifice Wednesday, too, if it meant my favorite player could do something no Met had ever done.

Calculations were made and Jose was removed. The calculations, however, didn’t seem to take into account that this was potentially Jose’s last game as a Met, and that the maybe 15,000 in the house were there primarily to see him. One of those joining me Wednesday had to arrive late. The last time Jose Reyes batted (whether in 2011 or forever in our colors), he had to watch it on the radio.

Then, after Mike Baxter made his childhood dreams come true by homering halfway to Whitestone and Miguel Batista turned back time with a two-hitter, word spread that it wasn’t Collins’s idea to take out Reyes. It was Reyes’s idea to take out Reyes, though Collins signed off on it.

It was growing weirder, even as it was kind of understandable. That .337 wasn’t all crafted in one day, so why endanger a lead that probably would have been larger had Jose’s hamstrings not barked twice in midseason? Plus, baseball lore is chock full of these kinds of machinations. These aren’t accumulative numbers; they’re averages. You play the percentages, assuming you have no compelling reason to play nine innings.

Did Jose? Depends on your priorities, I suppose. I suppose if your goal was to watch Jose bat as often as possible before he might not bat for you again — and why wouldn’t you want to see Jose bat again and again? — you feel somewhat betrayed. I suppose if your goal was the batting title, you could get with the math and say (as some businessman type who noticed my REYES 7 shirt at Jamaica did), “Smart.” Hike your average, make it challenging on Braun, play that percentage. Or you could still strive for that crown but want it to land on Jose’s head in a more sportsmanlike fashion. “Did I ever tell you the story of how in Two Thousand And Aught Eleven Jose Reyes insisted he be deducted three points from his batting average so as to give the rest of the league a fair chance to catch him? And then he played twenty innings even though the game wasn’t tied!”

Ultimately, these are the Mets, and few are their clear-cut triumphs. Three years earlier to the day, they couldn’t kiss their stadium goodbye cleanly because they had to miss the playoffs just before the farewell. Five years ago next month, they couldn’t fully enjoy arguably the greatest defensive play in their history because they had to be ousted from the playoffs shortly after that play was made. In some other year, something else went well, but it wasn’t unsullied because something else went awry. It just bleeping happens that way for us. This time it was Jose’s turn to not do everything right…except hit for a higher batting average than anybody else over the course of an entire National League season.

Which he did. If somebody wants to find a reason to not enjoy that, I welcome that person to his or her problem with it.

I’m inclined to let Jose off the hook (and won’t he be relieved?) because he’s Jose; and because he emerged from the Met dugout a good ten minutes after the game was won to greet the many who congregated behind it to wish him well; and because he partially gets how much the fans love him, even if maybe somebody should have told him the fans didn’t want him only to wave at them but to play for them. Above all — even above that batting crown — was the chill I felt watching him being replaced by a pinch-runner. That was a signature scene too often these past few seasons: Jose busts it down the line, Jose grabs something, Jose has to come out, we wait and wait for Jose to heal so we can watch him bust it down the line with no encumbrance.

It’s horrible enough when that sort of thing happens organically. Why court the image?

For now, Jose earns a line in the record books, and I’m happy. I’m happy I got to see him for nine seasons. I’m happy I got to see his bunt single Wednesday. And I’m happy that Blue Point drank some sense into me and I stayed for the remainder of Closing Day. I’m happy I got to spend precious innings with a few good friends and happy I ran into several more over the course and the aftermath of the finale. Who would go to see the 77-85, fourth-place Mets take their last gasps as a bedraggled unit? Me and seemingly everybody I know.

I love that. I love this, the part where I get to write about the game I just attended. I will miss it all before long. I always do. I missed it when Shea shuttered annually for what we baseball fans prematurely call winter and I miss it now that Citi Field is our ballpark-in-residence. I wound up inside its overly precious walls on 29 separate occasions in 2011. I had, at the very least, a good time on 29 separate occasions, despite the wan 13-16 record the Mets gave me for my troubles. It took three seasons, but I’m at peace with Citi Field. It’s where the Mets play. It’s where I seemed to go more than anywhere else I technically didn’t have to be this spring, summer and early fall. It’s where I spent Sunday, Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday. It used to be I’d go the final home game of the year. Now I take in the entire last series. I guess I’m chronic where the Mets are concerned.

To my enablers and friends who made those 29 occasions never worse than not bad, I thank you from a place much higher than fourth. To all who read this blog and occasionally seek us out to tell us what it means to you, I thank you, too. To my fellow Mets fans, with whom I anticipate sharing the otherwise barren months ahead in this space, I am moved to invoke the words of lyricist Phyllis Molinary:

May all your storms be weathered.

And all that’s good get better.

One of those with whom I parted ways on Closing Day reassured me that it will be April soon enough. I sure hope so. After all, it became September awfully quick.

by Greg Prince on 28 September 2011 10:01 am We interrupt this annual limp to the finish line to remind you baseball is wonderful and the Mets aren’t so bad themselves.

Put aside the third consecutive losing record, the now-perennial fourth-place finish and all that has contributed to the long-term disappointment that seems to define this franchise around this time of year. Consider instead what baseball can do for its fans sometimes, and what the Mets did recently.

Roger vs. the Elements, heading up Denali. In June, Faith and Fear shared the story of David Roth and Roger Hess. David’s the Mets fan who was diagnosed with a brain tumor while on a family vacation late last summer. Roger’s the Mets fan who’s been his friend going back to elementary school and the mountain climber who dedicated his ascent up Denali in Alaska to David by using it to raise funds for the Tug McGraw Foundation. Longtime readers of FAFIF will recognize TMF as an organization founded by one of the all-time Mets greats to work toward treatments and improved quality of life for those burdened by the disease that afflicted Tug and afflicts David.

Roger made it pretty far up that mountain and pretty far up his fundraising goal, too. He returned from Alaska having garnered more than $10,000 for the Tug McGraw Foundation, including donations from some thoughtful Faith and Fear readers. It was a compelling enough story to get the attention of Otis Livingston, one of Channel 2’s sports anchors. Otis had David and Roger on CBS 2’s Sunday Morning in July, where early birds got to hear about what one Mets fan will do for another. You can see their appearance here.

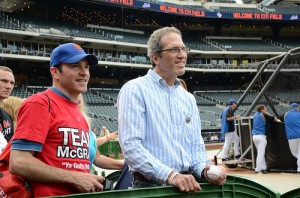

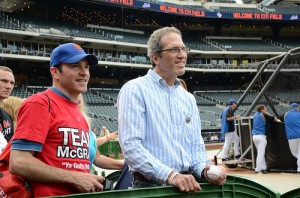

The Mets took note, and as alluded to in Channel 2’s coverage, they wanted to thank these fans of theirs by having them out as their guests for batting practice. Roger and David weren’t about to say no.

David and Bonnie get the lay of the land from the Mets' Ethan Wilson. Given our interest in how David and Roger had persevered — and with their blessing — I asked the Mets’ Media Relations department if Faith and Fear could be credentialed for BP that same day, September 1, so I could follow them around and report on their experience. I’d been on the field pregame a couple of times in 2010 and noticed there were always knots of people (kids as well as adults) on the edges of the action. These were guests of the Mets, too. The Mets generally didn’t call attention to their presence. It was just one of the pieces of the pregame mosaic, easy enough not to notice. But there was usually a generous reason the Mets made it available to those people who formed those knots.

Not a bad place to be welcomed. I wanted to notice it. I wanted to see how it worked and explain, if I could, what it meant for a couple of fans like Roger and David to have this kind of moment so close to the players and the diamond and everything a Mets fan usually watches from relatively far away. I also wanted to bring along crack photographer and longtime Tug McGraw Foundation supporter Sharon Chapman to capture the scene in pictures. Any photos you see with this story that aren’t from mountaintops she took.

Mets Media Relations, in the person of Shannon Forde, couldn’t have been more accommodating of my request, which I greatly appreciated. Sharon and I picked up our Field Passes the same time David and his wife, Bonnie, were picking up theirs. Somebody in the office where media checks in made a call on the Roths’ behalf, and out came Ethan Wilson, one of Shannon’s colleagues. He had been the point of contact between the Mets and Channel 2, I gathered, and was ready to lead David and Bonnie to the field (Roger and his son, Josh, were stuck in traffic and would join them a bit later). I quickly explained to Ethan what Sharon and I were doing — this was coincidentally the same night the Mets had invited bloggers to a function for Tuesday’s Children, so Ethan at first thought we were making a wrong turn when we started to follow him — and Ethan shrugged, said OK and we all set out for BP.

I won’t endeavor to weave a narrative from here. Rather, I’ll just share my observations.

Though it was a particularly busy day for Media Relations, Ethan took the time to provide a condensed guided tour for David and Bonnie as we walked through the labyrinth of corridors “regular” folks don’t usually see. He pointed out why certain artifacts hung on the walls. Here was a blowup of the lineup card from the first game at Citi Field. Here was a 2009 team picture, the ballpark’s inaugural squad. Off to the left, unmentioned by Ethan, were three Mets broadcasters — Gary Cohen, Howie Rose and Ron Darling. They bantered as they waited for the elevator, three guys whose day at the office was just starting. We hung a right and were headed down one more short hallway, the one that leads you to the field.

This was empathetically exciting to me. I’d been down here a few times, but I have a way of switching into professional mode (even if nobody pays me to blog), so my reflex is to play it cool even in a situation that rates as cool in its own right. But Roger and Bonnie were under no such obligation; nor was Sharon, who’s been taking pictures from the stands all year and now she was going to be able to do it from up close. I was getting goosebumps not for what I was about to see but for what these people were about to see. (I got all my “IT’S THE FIELD!” goosebumps out of the way on September 6, 1998.)

Mets fan, about to meet the Mets' field. It was September 1, the day callups join the team, the erstwhile minor leaguers who insist they are just happy to be here. I’m pretty sure David and Bonnie — and Sharon, for that matter — were happy to be there. And I was happy they were happy.

David Wright, practicing the taming of his Citi Field demons. Once we got positioned somewhere between the Mets’ dugout and the batting cage, David’s phone sounded. It was Roger. The Whitestone traffic had been punishing, but now he was closing in on Citi Field. David was standing feet from the players on his favorite team and in the midst of that kind of proximity, he was navigating his friend into the parking lot and toward the correct entrance. He could have been doing it from anywhere, but I had to smile when I heard him say, “I’m on the field.” You don’t get to say that every day.

As close as one can get to batting practice without a bat. Bonnie and David planted themselves at the special-guest barricade. Sharon wandered a little further down the right field line (as the Field Pass allows). I sort of hung back to take in the scene, to see who else showed up, to watch how people react to being almost in the heart of Metsdom. I was amazed how quickly a person gets used to it. “I’m on the field,” is where you are, so it’s where you belong. Why shouldn’t you be on the field?

One of those on the field was a gentleman in a PAPD cap — Port Authority Police Department. Part of the Tuesday’s Children contingent, I assumed. I’d learn later he was former PAPD Officer Will Jimeno, and his 9/11 tale is as chilling as any. Still, I overheard him tell somebody, he “doesn’t regret” any of it.

Mr. Jimeno was trapped in the rubble of a fallen tower almost exactly ten years earlier. He was one of the last to be pulled out. He was injured badly and he lost comrades-in-arms.

But he was at Mets batting practice wearing his own smile.

It's not only the batters who practice during BP. Only if you show up early enough for a Mets game do you necessarily glean how much commemorating and honoring the Mets do of different causes and groups, and only then do you see how much preparation is involved. Among other things, September 1 was Hispanic Heritage Night, sponsored by Goya. Several ladies in Goya-branded outfits came out for national anthem rehearsal. One of them, Nicole Toro, belted it out hours in advance, just to make sure her and the stadium’s pipes worked. Both did.

“The Star Spangled Banner” is a touchstone of any baseball game. Everybody rises when it’s delivered a few minutes before first pitch. When it’s delivered early, it maybe gets a little light applause. Maybe.

For a supposedly unpopular team, the New York Mets sure do inspire a frenzy when they’re feet away from you. People want to be on the same field with them. People want to stand next to them. People want them to sign whatever they’ve brought with them. Every Met, no matter his statistics or his prospects, is a star when you’re in their midst.

Jose: Nobody's more magnetic. Nobody is more of an attraction as the final month of the 2011 season commences than Jose Reyes. Nobody. David Wright was the bigger attraction last year. He’s still pretty attractive to many — Bonnie’s wearing a WRIGHT 5 jersey and wouldn’t mind an autograph — but Jose’s magnetic. He draws the most squeals. He’s asked to sign the most things. He is the most recognizable. He’s also taller and more muscular than you’d assume somebody who plays “shortstop” could possibly be.

If you were brought up reading phrases like “standing around the batting cage” in baseball columns, you might be surprised no reporters actually stand around batting cages. They loiter in the dugout until the given player they want is done. Maybe they follow him into the clubhouse to get what they need. I don’t know what happens when the field is vacated. But I do know I only saw one Mets writer cross right behind the batting cage, presumably en route to talk to somebody on the Marlins’ side of the field: mlb.com’s Marty Noble, who’s been covering the Mets longer than anybody. That, I decided, is why Marty is Marty. He doesn’t sit back and wait for the story to come to him.

In the stands, Citi Field’s environs seems almost tiny. I can pick out individual sections by number from wherever I am. Sometimes I can make out faces in those sections. At ground level, though, the field itself is huge. The outfield is green acres. No wonder Jason Bay can’t hit a ball out of this yard. Please, by all means, bring in a fence or two. Lower a wall. We don’t have the outfielders to cover all that space and we don’t have the sluggers to overcome its dauntingness. If we improve our pitching even a little, we’ll cope with that end of the equation.

Also happy to be here: September callup Josh Satin. Batting practice produces batted balls. They lie on the infield as if dropped by a flock of overhead geese. If one bounced to a fan, a fan would go wild. Yet they just sit there, scattered about like Rawlings confetti on New Year’s Eve.

Roger makes it through traffic and past security in time to have a ball with David. Roger fought through traffic and then talked his way past Hodges entrance security. My big contribution to the evening was when I told David to tell Roger to tell the guard who didn’t want to let him in because he didn’t have his and Josh’s ticket yet, “I need to go to media check-in.” I can’t believe I actually knew something approximating magic words, but it worked. When Ethan brought Roger and Josh out to join us, I asked Roger what was more difficult: climbing 13,000 feet or getting by an overofficious guard.

The guard, he said.

Two Mets fans enjoy well-earned Met proximity. Together again at last, David and Roger filled me in a bit on their Mets fan story. We’re of more or less the same vintage. They were eight years old in 1969. The Mets became their team up in Connecticut. Done deal for the rest of their lives, no matter that it wasn’t necessarily the thing to stay over the next bunch of decades. They recalled a “vehement Yankees fan” of their childhood acquaintance whose mere existence seemed to confirm their choice as the right one.

Without much provocation, Roger took me on his journey up Denali. During the retelling of one particularly tense episode, he clutched my arm as he described the severity of the elements and the self-doubt he faced (“I thought I was toast”). He mentioned, too, how much it took out of him, that when he was back at his job in early July, he found himself nodding off at his desk. Yet he expressed no regret for taking on the challenge. Way the hell up there, as close to the heavens as a human being could reasonably hope to get, he looked around, and he said, “it felt like being an astronaut.”

Ethan had earlier suggested that because the Mets finish their half of batting practice by 5:30, that might make a good time to go and grab some dinner. Once the visitors begin to take BP, he joked, “the thrill is gone.” We laughed when he said it, but when the Mets left and the Marlins were swinging in their place, we didn’t even seem to notice. You’re on a major league field, even one swimming with Marlins, the thrill doesn’t vacate.

“I still have cancer.” David says it matter-of-factly, not for shock value, just to keep you updated when you ask how he’s doing. But he’s here at the ballpark. You wouldn’t have bet on that a year earlier. He’s doing a lot of things. There are checkups and there are tests and there are steps he’s taking and his own mountain-climbing, figuratively speaking, is pretty damn impressive. After a while, though, we’re not talking about David’s cancer. We’re talking about how each of us met our mutual friend, Jeff, the unseen hand in making this night happen. We’re trading Jeff stories on the field where the Mets play. I’m stunned at how quickly two people fall into casual conversation on the same grounds that a little more than an hour ago they approached with at least a little awe.

Bonnie and David, Roger and Josh...they seem to have a good time. Bonnie Roth didn’t acquire a WRIGHT 5 autograph. But HYDE 17 of the Marlins — our new all-time favorite bench coach Brandon Hyde — tossed her a BP-used baseball. She clamored for it, but respectfully. So he tossed it gently. A real baseball from real batting practice from a real coach…a real mensch. Dozens of balls were strewn behind the pitcher’s mound, but this one was truly special. It belonged to one of us.

Roger had climbed a mountain. David had made it through a year of cancer. Bonnie had a baseball. Everybody was no more than an arm’s length from the ballplayers. Everybody was standing on the same sod where the ballplayers stood. Everybody was leaning forward over barricades. Everybody was getting their picture taken. Nobody was in a rush to leave. Nobody wasn’t thrilled.

Everybody was an astronaut.

If you can, please contribute what you can to Roger Hess’s continued fundraising for the Tug McGraw Foundation in honor of his friend David Roth by visiting here.

If you like to run, Sharon Chapman would love to have you run with Team McGraw in the New York Rock ‘n’ Roll 10K on October 22. Registration details are here.

by Greg Prince on 28 September 2011 8:06 am On the first night I was inside Citi Field in 2011, well before the season started, someone who works for the Mets said to a group that included me, “You guys are the diehards.”

On the last night I was inside Citi Field in 2011, just before the season ended, we still were, at least by the standard definition that implies implacable devotion to a cause. Our cause is the New York Mets, for modestly better or predictably worse. That much is clear after 161 mostly unsuccessful games — except “diehard” implies a resistance to prevailing trends, and I don’t necessarily think that describes people like us, people who dotted select portions of the stands for the Mets and Reds on a Tuesday night long after the Mets and Reds on a Tuesday night would mean anything to anybody else.

It’s not that we’re resistant to prevailing trends. We’re indifferent to them. We’re impervious to them. We don’t know that there’s a whole wide world out there that doesn’t give a damn about the 2011 Mets when 2011, in Met terms, is innings away from expiring. It doesn’t occur to us to notice. And if we happen to be accidentally cognizant that the 2011 Mets are high on nobody’s list of priorities but our own, what do we care about anybody else’s list? Ours commences, continues and concludes with the 2011 Mets, until there are no more 2011 Mets.

When that occurs, which it will innings/hours from now, we’ll start a new list, under the heading of 2012 Mets.

But we don’t leave the 2011 Mets until every last one of them has left us. We don’t leave the 2011 Mets until the 13th inning of the second-to-last game, and if we can, we plan an instant return for the last game. We go nowhere where our team is concerned.

Our team also goes nowhere, but we figured that out quite a while ago.

Last night at Citi Field — the last night at Citi Field for this year — was great until it wasn’t, and it wasn’t great then only because it ended the way it did, with another Mets loss (despite a dissonant scoreboard message that insisted METS WIN! after Justin Turner lined into a game-losing double play).

Jose Reyes was great as he embraced his chase for five decimal-place immortality before he probably chases nine digits preceded by a dollar sign. Jose homered deep twice. Jose singled shallowly once. Jose was on handmade signs. Jose was on everybody’s minds. Jose was on second as Ruben Tejada endeavored to drive him home in the bottom of the ninth. Jose was on third by the time Ruben worked one of his already-patented ten-pitch walks. Jose was atop the batting race by a scintilla of a whisker of an eyelash when he came out on deck as the potential not-losing run in the 13th. Jose stood there and watched his last plate appearance evaporate before it could materialize, just as Ryan Braun did when some Brewer got picked off before he could surge ahead of or, better yet, drop further behind Jose.

We watched Jose closely. We watched the out-of-town scoreboard obsessively. We watched TAM overcome NYY, BOS fend off BAL, PHI crush ATL and STL inevitably pound HOU to ensure two last-day Wild Card ties in a sport that allegedly requires another playoff round to generate late-season drama. Add that to whatever we divined (and confirmed, via smartphone) Braun was doing as MIL took on PIT, and I was moved to remark to my companion that even though somebody who likes something I don’t might not understand why I don’t like what he does, I don’t understand how anybody couldn’t like baseball as much as I do. We’re watching results from games we’re not even watching, and it’s thrilling — AND we’re watching a game right in front of us!

That was before the game right in front of us got all Acosta’d and Parnelled, but the point holds. How could anybody not want to be a diehard if being a diehard means one more night outdoors with baseball all around you? In the company of diehards like you to whom you don’t have to explain yourself?

Got something you’d rather do than go to the last night game at Citi Field last night? I mean besides go to the last day game at Citi Field today?

I didn’t think so.

by Greg Prince on 27 September 2011 2:42 pm Welcome to The Happiest Recap, a solid gold slate of New York Mets games culled from every schedule the Mets have ever played en route to this, their fiftieth year in baseball. We’ve created a dream season that includes the “best” 151st game in any Mets season, the “best” 152nd game in any Mets season, the “best” 153rd game in any Mets season…and we keep going from there until we have a completed schedule worthy of Bob Murphy coming back with the Happy Recap after this word from our sponsor on the WFAN Mets Radio Network.

GAME 151: September 22, 1988 — METS 3 Phillies 1

(Mets All-Time Game 151 Record: 20-27; Mets 1988 Record: 94-57)

Love, according to lyricist extraordinaire Sammy Cahn, may be sweeter the second time around, but what of clinching your second division title in three years? How could an event that replicates something that was so sweet and so longed-for just two seasons earlier possibly hold up by comparison?

Consider the reactions of the team’s co-captains, Gary Carter and Keith Hernandez, as captured in New York magazine by Eric Pooley:

“Was it sweeter in ’86?” Carter asked rhetorically. “No. It’s just as sweet now. Just as sweet.”

“Actually, it’s kind of anticlimactic.” Hernandez countered. “I mean we have a lot to be proud of, but we played some terrible baseball this year. This doesn’t rate with ’86. Then, the team had been through all those lean years, and we brought it back. This time, we’ve won it before, and we expected it to win it again.”

So at the crest of the 1988 club’s season, things were as good as they ever were…and they couldn’t possibly be that great. Ask Carter, ask Hernandez, ask a Magic 8 Ball. The answer might as well be, “Reply hazy, try again.”

To enjoy what the Mets did in September 1988, it is, perhaps, best to put aside all they did throughout 1986…and try not to think about what lay ahead in October 1988. It should be enough to appreciate the finishing kick the Mets put on to get the Thursday night at Shea when the Mets put away the Phillies, 3-1, to officially eliminate their last competition for their fourth National League East crown.

After surging to a 30-11 start, the ’88 Mets stalled, sputtering through the summer at a 41-41 clip. They allowed the Pirates to sail practically right up alongside them in the standings in July. And though they always managed to hang on to their divisional lead, the Mets left their fans with the sense that it could all go awry at any minute. Except for Darryl Strawberry and Kevin McReynolds, they weren’t hitting. In general, they were lethargic. The Mets were ripe for the taking, perhaps by the Pirates, maybe even by the Expos.

Then they weren’t. In a veritable blink, the Mets lived up to their hype. They started winning at the end of a West Coast trip in August and they refused to lose thereafter. Gregg Jefferies came up. Mookie Wilson went into the everyday lineup. David Cone proved invincible. Everybody began to hit. Entering the potential clincher, the Mets had been on a 22-7 roll.

The roll continued against Don Carman and Kent Tekulve with single runs in the fifth, sixth and seventh, handing Ron Darling the 3-1 lead he dearly wished to pitch to its successful conclusion. “To my thinking,” Ronnie would write in his aptly titled career retrospective, The Complete Game, “it was complete game or bust. If I didn’t finish the game and we still managed to win, I supposed I would pop a bottle of champagne and celebrate with my teammates, but it wouldn’t be the same.”

It wouldn’t be a worry by the ninth, when the Mets still led by 3-1. As Darling faced Philadelphia’s 4-, 5- and 6-hitters, SportsChannel’s Fran Healy and guest commentator Jack Lang of the Daily News suggested there were nothing but blue and orange skies ahead for the team they covered:

Fran: Jack, [can] you believe that the Mets right now will win their second division under the regime that took over in 1980?

Jack: That’s right. And what a machine they’ve built. This won’t be the last of these we’re gonna see from them. Not with that pitching staff.

Darling, 28, and headed for a 17-win season was as good a sample of that arsenal as anybody. He and Cone and Dwight Gooden would be leading these Mets into the National League Championship Series. Cone wasn’t even here in 1986. Nor was Jefferies. Nor, except for cameos, were Randy Myers, Dave Magadan and Kevin Elster. These Mets were more loaded than their championship predecessors. GM Frank Cashen had indeed built a machine. Hernandez and Carter might not be Mets forever, but the talent was in place to make sure the Mets would be in this kind of position on a going basis. They’d be on the verge of great things.

Von Hayes struck out. Juan Samuel grounded to Darling, who threw to Hernandez. And on a 1-2 pitch, Lance Parrish couldn’t check his swing. It was strike three and the Mets’ were champions again. Carter no doubt thought the ball he held in his mitt represented something sweet — and the 45,000-plus in attendance certainly evinced a sense of ecstasy — but Darling was particularly appreciative of how the seconds after the third out unfolded:

“Kid was the first one to reach me, and he came at me with his right hand extended. I remember thinking it was such a professional, businesslike approach. Every other time I’d seen a pennant-clinching game, there were hugs and high-fives and backslaps all around. Guys were jumping all over one another. But here Kid just walked purposefully to me with a congratulatory handshake, his eyes wide with excitement.”

In his book, Darling describes a picture of that exchange as his favorite image from his tenure with the team. “[I]n that one freeze-frame moment,” he wrote with Daniel Paisner, “was everything I knew and loved about those Mets teams of the 1980s. There was our thoroughgoing professionalism. There was a sense that we were expected to win, and to carry ourselves as winners. And there was a sense of pure joy about to burst forth.”

The joy burst through soon enough. The champagne would pop and the Mets would drink some and douse more. As it occurred, nothing could have been sweeter. It’s easy to overlook just how sweet it was when compared to the celebrations of two years earlier and the lack of any more of them in the month ahead.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On September 18, 1973, the rallying cry “You Gotta Believe!” was picking up new users every day, probably because it was gaining credence in every way. The Mets hadn’t shown the slightest inclination toward getting involved in a pennant race through most of the season, but in September, as exemplified by Tug McGraw’s power of positive thinking, they were making their move.

Now came the time for them to turn it into a great leap forward.

The night before, belief could have taken a hit. Tom Seaver pitched at Pittsburgh and was battered, with the Mets losing 10-3, sticking the team 3½ back, leaving them in fourth place. But the key phrase there is “3½ back”. It was anybody’s division with a dozen games to go. It could be the Mets’, as it was the Pirates who sat in first place and the Mets were about to play four more games against them: one more at Three Rivers Stadium, three directly thereafter at Shea.

Seeing their ace get spanked and watching their momentum frozen could have seemed like a bad sign to Metsdom, but that’s where that positive thinking comes in. That’s what Tug’s mantra was all about. Tug hadn’t been going well in the middle of summer, either, but he had been convinced by no ordinary Joe that he could turn his season around.

The Joe was Joe Badamo. As Tug put it in Screwball, “He sells insurance. Insurance and motivation.” Tug knew Joe through Duffy Dyer, who, along with some other Mets, was introduced to him by the late Gil Hodges. He may not have been a guru, but Tug was willing to follow what he had to say.

“We rapped a while and decided there wasn’t anything wrong with me physically,” Tug wrote (with co-author Joe Durso). “But first we had to get my confidence and concentration back. The only way to do that, Joe kept saying was to believe in yourself. Realize that you haven’t lost your ability. Start thinking positively. Damn the torpedoes, and all that jazz.

“When he said, ‘You got to learn to believe in yourself,’ I said: ‘You gotta believe. That’s it, I guess, you gotta believe.’ And he said, ‘Yeah, you gotta believe, start believing in yourself.’”

From one conversation with one person, a movement was born. Tug threw “You Gotta Believe” to a few fans and they threw it back to him like in a game of catch. He brought it into the clubhouse, and it caught on. Without thinking, he blurted it in the middle of a pep talk delivered by chairman of the board M. Donald Grant (and later had to convince the stodgy executive he wasn’t mocking him). “You Gotta Believe” took root in July, when the injury-riddled Mets were still in last place, when Tug was still in his epic 1973 slump.

Yet it was ready to bloom come September when the Mets and their fans were brimming with belief that a team in the last place on the next-to-last day of August could roar from behind to win the division. Before the Pirates beat Seaver, the Mets had taken 12 of 17. In a year when nobody could gather a head of steam and take control of the N.L. East, the Mets could still be the ones to do it. They just had to, per Joe Badamo and Tug McGraw, believe.

And start beating the Pirates head-to-head immediately.

Game two of their five-game series loomed as a turning point either way. For eight innings, it appeared to be turning clearly in the direction of where the Allegheny and the Monongahela met to form the mighty Ohio. Pittsburgh took a 4-1 lead off Jon Matlack in the third inning, knocking out the talented lefty one night after having their way with Seaver, and the score remained unchanged through the eighth. Ray Sadecki and McGraw had pitched well to keep the Mets in the game, but New York hadn’t done anything with Pirate starter Bob Moose or his successor Ramon Hernandez, who stood two outs from victory when he fouled out Bud Harrelson to start the Met ninth.

Ed Kranepool was due up next, but Yogi Berra pinch-hit with Jim Beauchamp, a righty batter versus lefty pitcher decision. It worked, as Jim singled. Then Wayne Garrett, in the midst of a career month (OPS 1.015) doubled. Felix Millan, who would establish a new franchise record for hits in 1973 with 185, got his most important to date: a two-run triple that cut the Mets’ deficit to 4-3. After Hernandez walked Rusty Staub, Danny Murtaugh pulled Hernandez in favor of his fireman Dave Giusti.

But Giusti only enflamed the Mets’ rally, giving up a pinch-single to Ron Hodges to tie the game at four. Teddy Martinez ran for Hodges. Cleon Jones followed with a walk. And Don Hahn, who played more center field than any Met in 1973 despite never being fully entrusted with the full-time job by Berra, singled in Martinez and Jones.

The Mets led the Pirates, 6-4, heading to the bottom of the ninth. Clearly, the tide had turned away from the Three Rivers and toward Flushing Bay. But first, a little business would have to be taken care of. Three outs had to be nailed down, and this was where Tug and his Belief would come into play.

Except Berra had to pinch-hit for Tug in the eighth. So he went to as untested an arm as he had: 23-year-old Bob Apodaca, a righty being asked to make his major league debut in the makest-or-breakest situation imaginable.

Apodaca nearly broke the Mets. He threw eight pitches: four to Gene Clines, four to Milt May. Each was a ball. The Pirates had two on and none out. Dack’s trial by fire had burned Berra, so he took out the kid and brought in a slightly more seasoned hand, 25-year-old Buzz Capra.

Would there be a feelgood, Capraesque ending from all this maneuvering? Well, Dave Cash bunted the runners over. Al Oliver grounded to the right side to score one of them. Willie Stargell was intentionally walked, then pinch-run for by rookie Dave Parker. Richie Zisk walked.

The bases were loaded. There were two out. The Mets led by one. The dangerous Manny Sanguillen stepped to the plate. It was all on Buzz to keep the Mets alive. Could he?

You had to believe it was so. Capra, whose strategy was “go with my fastball and make sure he hit it,” flied Sanguillen to Jones in left and the Mets held on, 6-5. They were now 2½ behind the first-place Pirates, but they had three more shots at them, and all of them would come at Shea.

Cue the power of positive thinking.

GAME 152: September 19, 1973 — METS 7 Pirates 3

(Mets All-Time Game 152 Record: 20-27; Mets 1973 Record: 75-77)

If you’re going to have momentum, there’s no sense in waiting around for the optimal moment to use it. The Mets came out of Three Rivers after winning a thrilling come-from-behind victory the night before, so who better to bring with them to Shea but the same Pirates they had just beaten?

Strange schedulemaking, but there it was and here they were, the Mets and Bucs, now locked with the Cardinals and Expos in a four-way battle to determine who, if anybody, was going to emerge as National League East champion for 1973.

These two contenders go back and forth in the early innings. The Pirates strike first on a leadoff home run by Rennie Stennett off George Stone. Cleon Jones one-ups Stennett by smacking a two-run homer off Nelson Briles in the second. Advantage Mets. Stennett returns with a vengeance in the third by tripling and scoring on Dave Cash’s single to left. Advantage Pirates? Felix Millan grabs back the momentum on behalf of the Mets when he singles home the .271-batting Stone, who had led off the inning by helping his own cause (something decent-hitting Mets pitchers were known to do for much of the first half-century of Mets baseball).

The Mets’ 3-2 lead grew by a run in the fifth when Jerry Grote doubled, Bud Harrelson singled and Stone grounded to second. That insurance policy became a smart buy when Stone was befallen by an act of Pops: Willie Stargell, who hit more home runs against the Mets than any opponent in the team’s history, delivered per usual. Luckily, Stargell’s sixth-inning blast was a solo job, so the Mets still held a 4-3 lead when George let after six.

Stone’s successor was Tug McGraw, Yogi Berra’s favorite reliever in September — everybody’s favorite reliever in September, but it was Berra who wouldn’t or couldn’t wait to use him. Firemen, as closers were known then, weren’t saved for the ninth. McGraw came bounding onto the mound in the seventh and wasn’t particularly sharp. He walked pinch-hitter Gene Clines and surrendered a pinch-single to Fernando Gonzalez. The runners wound up on second and third with one out, but Tug stiffened as he almost always did in September 1973, popping up Stennett and grounding out Cash.

Tug encountered a bit more trouble in the eighth, allowing a leadoff single to Al Oliver, but two ground balls — the second of them a 5-4-3 double play — resulted in three outs and kept the Mets ahead by a run. Finally, some breathing room emerged in the eighth when, against Dave Giusti, Rusty Staub singled, John Milner walked and Jones homered for the second time on the evening. With his third, fourth and fifth RBIs of this Wednesday evening, Cleon had put the Mets up 7-3. Tug mowed down the final three Buc batters in the ninth and the Mets moved into a third-place tie with St. Louis, a half-game behind Montreal for second and a game-and-half from first-place Pittsburgh, with two more games against those Pirates at Shea.

It all made for very exciting bookkeeping…and it was about to make for so much more.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On September 21, 1989, Sid Fernandez did everything right. Everything. For one, he pitched a two-hitter, with the hits confined to one inning, the bottom of the fifth at St. Louis. Those hits — a Terry Pendleton triple and a Todd Zeile single — produced a single run for the Cardinals this Thursday night. The other eight innings saw the sometimes maddening, often brilliant El Sid display perfection: no hits, no walks, no Redbird baserunners.

As for the Mets’ offense, it had Sid Fernandez’s imprimatur all over it, too. The Hawaiian southpaw singled and scored in the third, singled in the fourth and homered in the ninth. Fernandez himself outhit the Cardinals, 3-2. When you factor in his not striking out as a batter but striking out 13 batters as a pitcher, then it’s no wonder El Sid prevailed in this most complete of complete game victories, 6-1.

GAME 153: September 20, 1973 — METS 4 Pirates 3

(Mets All-Time Game 153 Record: 22-25; Mets 1973 Record: 76-77)

It was time to carefully remove the m-word from the ark in which it had been kept undisturbed for nearly four years, for the Mets were about to perform the most sacred act their faith allowed.

It was time for a miracle.

But first, the relatively mundane from this about-to-be extraordinary Thursday night at Shea Stadium:

• Jerry Koosman pitched eight innings, struck out eight Pirates and allowed only one unearned run, which unfortunately put him behind 1-0, because Jim Rooker had held the Mets scoreless through seven.

• Jim Beauchamp, making the final regular-season appearance of his ten-year career, pinch-hit for Koosman to lead off the bottom of the eighth and singled. After he was pinch-run for by Teddy Martinez, and Martinez was bunted to second by Wayne Garrett, Felix Millan singled home the tying run.

• Harry Parker, usually a rookie revelation in Yogi Berra’s bullpen, came on to preserve the tie in the top of the ninth but couldn’t quite do the job. Two runners were on when Dave Cash doubled one of them in to return the Pirates to their lead, 2-1.

• Bob Johnson, who pitched two games for the 1969 Mets, was tabbed by Danny Murtaugh to finish off his old team. A win here would erase the Mets’ recent momentum, leaving them 2½ back with a scheduled nine to play. It wouldn’t clinch anything for the Pirates, because others were still alive and contending, but it would put a crimp in the Mets’ plans, no matter much they Believed. But Johnson allowed a leadoff pinch-single to Ken Boswell and a sacrifice bunt to Don Hahn before exiting for Ramon Hernandez.

• Hernandez struck out pinch-hitter George Theodore for the second out of the ninth, but another pinch-hitter, Duffy Dyer, delivered a double, scoring Boswell to tie the game at two.

• The two teams went to extra innings, as Yogi Berra went to veteran swingman Ray Sadecki. Sadecki gave Yogi three perfect innings. The Mets, meanwhile, failed to score against Jim McKee and Luke Walker. The game would go to a thirteenth inning, when Sadecki, with one out, would allow his first hit, a single to Richie Zisk. After he retired Manny Sanguillen for the second out of the inning, he faced September callup Dave Augustine.

This is where The Miracle occurs.

This is where it’s best left to Bob Murphy to deliver The Word:

“The two-one pitch…

“Hit in the air to left field, it’s deep…

“Back goes Jones, BY THE FENCE…

“It hits the TOP of the fence, comes back in play…

“Jones grabs it!

“The relay throw to the plate, they may get him…

“…HE’S OUT!

“He’s out at the plate!

“An INCREDIBLE play!”

If you’re scoring at home, the interpretation would be 7-6-2, Cleon Jones to Wayne Garrett to Ron Hodges, the rookie catcher who ascended to the Mets’ starting lineup for much of the summer from Double-A Memphis because of injuries. Zisk, the runner from first, tied a piano to his back when he took off around the bases. The man was slow. But The Man Upstairs was quick-thinking. He (or Something) prevented what looked like, on Channel 9, a sure home run for Augustine from landing in the left field bullpen for what would have been his first — and only — major league home run. Had the ball made it past the wall, the Mets would have been down 5-3.

But it didn’t go quite far enough, at least from a Pirate perspective. It bounced off the very top of the fence and caromed right back into Cleon’s glove. He made a strong throw to Garrett, who made a strong throw to Hodges, who made a strong stand in front of the plate, bringing down an emphatic tag on Zisk.

“The ball hit the corner and it just popped up to me,” Jones recounted. “I didn’t think he hit it high enough to go over. I knew the ball was gonna hit the fence, but it could’ve gone anywhere.”

Garrett, who had moved to shortstop from his usual third base in the tenth after Bud Harrelson had been pinch-hit for, aimed low when he made his relay throw to Hodges. “I wanted it to hit the ground,” Wayne said, and he got his wish. The ball arrived in Hodges’s mitt the same time Zisk was charging into Hodges’s body. The kid catcher held the ball and home plate ump John McSherry held his right arm upwards, signaling the lumbering Pirate runner out.

“It has to be one of the most remarkable plays I ever saw,” Garrett swore.

The Mets weren’t done being remarkable. The aptly named Walker walked his first two batters in the bottom of the thirteenth. Luke walked off the mound. Dave Giusti walked on. He got one out, but that was all. Hodges, having the night of his career, singled, scoring John Milner from second. The Mets had won 4-3 in a game that would be forever remembered for the Ball Off the Top of the Wall and how it bounced in the only direction it could.

Namely, the same direction the Mets were going in.

This third straight win over the Pirates didn’t put the Mets in first place. It didn’t even put them then at .500. But both of those events would happen the next night, when Tom Seaver would throw a five-hitter to beat the Bucs, 10-2. In a four-day span in September, an unprecedented Metamorphosis occurred. The Mets not only picked up one game per day in the standings, they picked up one place per day. From fourth and 3½ out after Monday, they climbed to first and a half-game up on Friday. It had been barely three weeks since they were in last place. Now they were in first place.

They were in first place. The Mets. The 1973 Mets.

You Gotta Believe.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On September 18, 1975, one Met slugger turned an odometer while another turned a page in the team annals. On a quiet Thursday night in Flushing, with the Mets done contending, their two biggest hitters hit some big milestones. First, there was Rusty Staub swatting a two-run homer off Cub rookie starter Donnie Moore in the fifth. That became the final home run of Staub’s initial tenure as a Met, which couldn’t have been known at the time. What could be ascertained was that Rusty had just become the first Met in team history to drive in 100 runs in one season. The Met who came closest in the previous 13 seasons was Donn Clendenon, in 1970. Le Grand Orange had already taken the record, and now he’d taken it into triple-digits.

In the bottom of the ninth, the score would be tied at five. The Cub pitcher would be a familiar face to Mets fans: Darold Knowles, he who pitched in all seven games against the Mets during the 1973 World Series. Knowles set a record then, but now he’d be on the wrong end of a piece of Met history. Knowles gave up a two-out single to Staub and then had to pitch to Dave Kingman. The pitch didn’t stay at Shea long. Kingman creamed it for a walkoff home run, Sky King’s 35th roundtripper of 1975. That gave Dave the team record, one better than Frank Thomas’s total from 1962.

That Thomas, who was on hand in Pittsburgh when Kingman tied him with his 34th circuit clout of the season, had held the mark for so long with a relatively slight total speaks both to the dearth of Met power bats for most of the life of the franchise to that point and to an anomaly for the ages. Frank Thomas was a fine hitter in his day — he outhomered both Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris to reign as New York City’s home run champion in the Mets’ first year — but how is it possible that something as significant as the franchise home run record could have stayed in place from 1962, a.k.a. the worst season any team ever had, all the way to 1975?

That wasn’t Thomas’s problem, just as it wasn’t Kingman’s. But the two were linked as Dave chased Frank, even if Dave wasn’t making too big a deal out of passing him. “It doesn’t means as much, since we’re out of the pennant race,” Kingman told the media following the 7-5 win his 35th homer secured. “Maybe when I’m 80 and sitting in a rocking chair, it will mean something.”

Thomas, in his 2005 memoir, Kiss It Goodbye: The Frank Thomas Story, gently took issue with Kingman’s attitude from three decades before:

“Kingman was only 26 at that time and it’s hard to imagine old age at that point in your life. When I was 26 and in the prime of my baseball career, being 80 years of age seemed impossible. But here I am, 76 years of age at the writing of this book, and heading fast to 80. And those old baseball records and memories are more and more treasured to me every year that I’m removed from my playing days. I haven’t seen Kingman in years, but I’ll bet he, too, has a greater appreciation for his accomplishments now that he’s only 23 years away from his rocking chair.”

by Jason Fry on 27 September 2011 3:56 am What was fun: watching Jose Reyes hit, hit and hit again. Ryan Braun later followed Jose Jose Jose Jose’s three-hit performance with a pinch-hit double, but with two days to go Jose’s .334 is a whisker of an eyelash above Braun’s .334, or at least so says ESPN.

What was less fun: watching Jose Reyes go too far around second base and get tagged out. D’oh.

Also less fun: Chris Heisey robbing David Wright and smashing a fatal home run. Terry Collins’ obsession with the bunt and Nick Evans’ inability to get down a component one conspiring to short-circuit a promising ninth-inning rally. Dusty Baker winning. Chris Schwinden’s awkward wind and chuck on every pitch. All those empty seats. I wanted to grab this game and hold it close, but it took forever and was mostly indifferently played, and I found myself yo-yoing madly back and forth between wanting it to slow down and wanting someone to get on with it already.

Really less fun: Realizing we’re already a backwater. The Red Sox and Rays are staring each other in the face with two games to go. The Cardinals almost caught the Braves before being tripped up by the spoilerific Astros. It’s exciting stuff, with Ozzie Guillen getting traded to the Marlins as a sideshow. Very soon, the bright lights will come up and the only Mets you’ll see will be on the wrong end of the highlights.

We’ve known it’s coming for a while. But it doesn’t make it any easier to take.

by Greg Prince on 26 September 2011 3:32 am “Hey, this is really nice.”

“Well, we decided it was a special occasion, so we should rent out one of the suites.”

“I’ve never been to one of these before.”

“We throw one every five days — just in case.”

“So this isn’t just an end of season thing?”

“Usually we just do it in Promenade and keep it simple, but since this is the last one of the year, we figured why not go all out?”

“I’m glad you did. Now how does this work?”

“You can order anything you like, and they’ll bring it you.”

“Anything?”

“Anything you’d normally have to wait in line for. Isn’t that amazing?”

“Wow. What a shame I’m really not that hungry.”

“Oh, come on, you have to try to the Failure to Take a Step Forward.”

“They’ll bring me the Failure to Take a Step Forward? I mean right here, to the suite?”

“That’s part of the package.”

“Package?”

“Oh yeah, it’s a whole production. They start you with a Deep Hole, just to set the tone — and from there you can order anything.”

“Anything? What about the Lack of Confidence?”

“You can get the Lack of Confidence AND the Lack of Command.”

“Geez, it is tempting.”

“I already ordered the Mountain of Earned Runs. It’ll be here in a minute.”

“The Mountain of Earned Runs? Geez, don’t you usually have to wait like three innings for that?”

“Not today. All the Earned Runs you could possibly imagine will show up instantly.”

“I don’t know. I don’t wanna overdo it.”

“Listen, you have to at least help me finish the Endless Frustration.”

“My god, how vast is that thing?”

“It’s Endless. And it comes with a Look of Bafflement.”

“Well, I’ll have a taste…mmmm…that really is Endless!”

“Try it with a few of the Earned Runs from the Mountain of them.”

“Just a few…”

“‘Just a few.’ You know you can’t have ‘just a few’ Earned Runs at one of these things.”

“No, you really can’t. What’s that they have at the other table?”

“That’s Patience. They said they were running out of it, though.”

“Say, didn’t one of the concessions used to sell a Real Sign of Progress?”

“We asked about that. They said it’s no longer available. They replaced it with the Pile of Base Hits.”

“I could use a drink. Any hard stuff here?”

“No hard stuff, at least nothing that’s effective. I tried it with a Carrasco chaser, but that only made it worse.”

“Any Kool-Aid?”

“Plenty, but nobody wants to drink it anymore.”

“This has been fun, but I’m really full.”

“You can’t go before they bring out the dessert.”

“Dessert?”

“What’s a party without dessert?”

“What do they have?”

“It’s like a very well-done dish, something left in the oven too long, probably. And it’s kind of chewy. Tough, almost.”

“That doesn’t sound very appetizing.”

“Well, it’s gotta be tough. It’s the Non-Tender.”

“Ooh, THAT I gotta try!”

A little afterparty chat with The Happy Recap Radio Show fellas, here.

by Greg Prince on 25 September 2011 10:34 am I’m kind of sorry I ever heard the admonition to not trust what I see in September since I’d like to believe what I watched and listened to Saturday was a true indication of where the Mets (and the Phillies) are headed. Yet I understand that they were just two games getting played because contractually they had to get played. The Phillies’ main interest, presumably, is avoiding injury and shedding rust; the best that can be said for their seventh and eighth consecutive losses since clinching their fifth consecutive division title is nobody got hurt…but the key phrase in there is “since clinching”. Per Leo Durocher, except in a more complimentary light, those weren’t the real Phillies we saw yesterday, particularly in the second game. But we’ve seen our share of the real Phillies since 2007, so I’ll take beating whoever showed up in their uniforms.

As for the guys in our uniforms, well, huzzah! When Dillon Gee was welcoming baserunner after baserunner to enjoy all that Citi Field’s basepaths had to offer, I pretty much wrote off the night half of Saturday as just one of those things. The Phillies were bound to change their losing ways and Gee just hadn’t been what we hoped Gee would be when we decided Gee was something else.

Yet in an echo of Thursday’s assumption-sundering turnaround, perceptions morphed slowly but surely. On Thursday, as the Cardinals began to have their way with Chris Capuano, and all the hitting shoes in St. Louis were Pujols red, I just assumed those bastards would sweep us efficiently and embarrassingly. But here and there, I noticed the Cardinals couldn’t quite overwhelm the Mets when they had the chance, and in baseball, what doesn’t get overwhelmed has a tendency to stick around. By the ninth inning, even down 6-2, the Mets were very much around to take advantage of Rafael Furcal’s whoopsie and Tony La Russa’s spastic lineup card, the one that couldn’t control itself from penciling in one ineffective reliever after another. The Mets weren’t bounced when they could have been, so instead they bounced back and won, 8-6.

In that vein, Gee, against the Phillies, looked ready to be shoved into his locker and stripped of his lunch money from the outset Saturday night. But damned if he didn’t turn bases loaded, nobody out into inning over, nobody scored. Dillon absorbed three runs worth of damage in the second and third, but he was still in there for three innings after that and went mostly untouched. The Phillies failed to give him the characteristically sadistic wedgie they had planned, and now Gee was free to roam the halls en route to victory. His 13th win, no matter how irrelevant an individual pitcher’s win total can be, was one of his most encouraging — no matter that the fiber of the Phillie lineup wasn’t as strong as it might be under other circumstances.

Under other circumstances, I might have looked at a starting Mets outfield of Willie Harris, Jason Pridie and Nick Evans and let out the groan heard ’round the world (or at least my living room), yet I wasn’t discouraged when I saw this “B” alignment come out for the nightcap. These guys were as good as we had right now. They were pretty much all we had right now, given the various maladies afflicting Jason Bay, Angel Pagan and Lucas Duda, but what else is new in 2011? You know how often we had our more or less ideal lineup together this year?

Never.

Never was Terry Collins able to present Josh Thole, Ike Davis, Any Second Baseman, Jose Reyes, David Wright, Bay, Pagan and Carlos Beltran on one field at one time. Even the various lowered-expectations combinations that we’ve conditioned ourselves to accept as provisionally ideal — post-Beltran, sans Davis — have been hard to come by. So you want to tell me my team is sending Harris to left, Pridie to center and Evans to right? I’ll say OK, let’s see what they’ve got.

What they had was good enough to manufacture five runs in the bottom of the third. Harris batted in the three-hole, the province of the Hernandezes and the Oleruds and the Beltrans in better years. Willie hadn’t batted third once in 2011 until Saturday night. But he muscled a fly ball to right that would have been out of a normal ballpark and was deep and treacherous enough to twist Hunter Pence into the perplexed llama I believe he will be in his next life. It may have been scored a three-base error, but Harris did the heavy lifting, and it drove in two runs to get the Mets and Gee back into the ballgame.

Evans, this year’s right fielder of no better than third resort, tied the game with a double, and Pridie — who had scored the first run of the third — scorched a ground-rule double to start another successful rally in the fourth. All three reserves contributed to making what had been an already good day into a sweepingly good day, yet none seemed like reserves in the Bambi’s Bombers or Rando’s Commandoes sense. They just seemed like Mets getting a game won, the way Mets have intermittently gotten games won in 2011 when you’ve all but consigned them to the Goodwill bin.

Both the games and the Mets.

It’s September, so I’m trying to remain logically detached from most of these positive results since it’s considered blatantly inadvisable to read too much into them. When your team is long out of the race (and by “long,” I mean three years), the emphasis can’t help but be on next season and the season after that. Sandy Alderson and his minions were brought in to clear away Septembers like this one and, let’s face it, most of the players who’ve populated them. Harris, Pridie, Evans and others have given us a few nice moments this September — many days late and many dollars short, but nice nonetheless. Winning five of eight against playoff-caliber teams following the stunningly depressing four-game sweep at the hands of the Washington Nationals, however, has had a Weekend At Bernie’s feel to it. The corpse can be dressed up spiffily and dragged around convincingly, but it’s still a corpse.

Tonight at six, The Happy Recap Radio Show is scheduled to include a dose of Faith and Fear. Tune in here.

by Jason Fry on 24 September 2011 7:55 pm The Mets are playing a day-night doubleheader, and so are we: My take on the day game will be followed by Greg’s report on the nightcap.

The Mets’ late-season swoon has annoyed me of late, but the morning still found me down in the dumps. Joshua and I were headed to Citi Field for our last visit of 2011. Taking our seat in the left-field seats under the Gulf sign, amid a red sea of hooting Phillies fans, I looked around sorrowfully, wanting to fix things in memory, wondering about what would be different the next time we were here. (The Mo Zone sure looks better with that added picnic area! But, man, seeing someone else wearing 7 is an atrocity!)

For a while it looked like we might have a day to truly remember: R.A. Dickey was ripping through the Phils, including Cole Hamels. I found myself getting testy as the countdown-by-threes reached 15, then 12, then nine, shushing my kid and crabbing at him that you didn’t discuss what was going on, even as the Mets and Phils fans behind us were yelling about first a perfect game and then a no-hitter. Nick Evans’ stumbling, staggering, sprawling catch on the warning track seemed like it might be a harbinger of wonderful things, but no, we are still the Mets. That Metsness would assert itself with eight outs left to get, as Shane Victorino received his ticket to the Clubhouse of Curses (how perfect that it was him), and Ryan Howard promptly drove him in.

The maroon invaders rose up to bray and cackle, and those of us in blue and orange slumped in our seats. Two minutes before we’d been floating along on a cloud of what-if; now we were neck-deep in despair. One brave Mets fan in the neighboring section came to the railing to berate the Phillies rooters, his wild, scraggly hair and bad teeth and helter-skelter clothing marking him as a ballpark crazy. His stare was baleful enough to get everybody’s attention, whereupon he screamed that “THE YANKEES WILL BEAT YOU IN THE WORLD SERIES!”

Dude, shut the fuck up.

The Mets, though, had a little gumption in them. The left-field corner isn’t the best place for judging long fly balls, particularly ones hit right at you, but the second Valentino Pascucci connected I was up and out of my seat, howling with glee. The ball landed about 25 feet in front of us, with Joshua’s late scramble just failing to end with a souvenir. An inning later Ruben Tejada turned in another terrific at-bat, digging himself out of an 0-2 hole and singling on a 3-2 count, after which he stole second and David Wright bounced one that had Placido Polanco going this-a-way and third-base ump Mike Estabrook going that-a-way and Tejada heading home. Manny Acosta survived a moderately frightening ninth and we were homeward bound.

All in all, not a bad way to go out.

by Greg Prince on 24 September 2011 10:49 am I yearn to crowd into Times Square and watch the zipper deliver the updates. I hanker to gather around the upright Philco in the parlor and receive the word seconds after it arrives via Teletype. I want Walter Winchell to deal me the dope.

Good evening Mr. and Mrs. America, from border to border and coast to coast and all the ships at sea! Let’s go to press!

Dateline Flushing, where National League hitting honcho Jose Reyes swings jauntily through Gotham’s baseball jungle to cling to his edge in the batting derby they way Tarzan gripped his vine…by the skin of his teeth. No New York Met has ever accomplished the above-average feat Sir Speed-A-Lot is on the cusp of achieving. All of Metropolis is pulling for you, Jose — hang on tight!

In hot pursuit: Milwaukee’s Braun bomber, Ryan Braun, seeking to become Dairyland’s first batting champeen since Hammerin’ Hank Aaron “Bravely” ascended to the title for a different franchise in a different century. Should Braun explode Reyes’s stick of Dominican Dynamite, he’d become both the first Brewish AND the first Jewish fellow to count his decimals higher than any of his National leaguesmen. L’chaim!

But wait! Who’s that coming along on the outside rail? It’s Hollywood star Matthew Kemp, seeking to don a crown three times as wide as any worn by any player in the senior circuit since Joe “Ducky” Medwick took home run, RBI and batting average honors in Nineteen Hundred and Thirty-Seven. In light of the flourish with which Matt is putting a cap on his spec-TAC-ular campaign, Camp Kemp overflows with happy Kempers as dawn kisses Southern California.

Yes, Mr. and Mrs. America, this one is a humdinger! Saturday’s action promises to unfold in a blur of bloopers, bleeders and Baltimore chops!

Where our Hillerich & Bradsby barons stand this morning…

Reyes: Point-Three-Two-Nine-Four-Eight-Zero

Braun: Point-Three-Two-Nine-Zero-Nine-One

Kemp: Point-Three-Two-Five-Eight-Six-Two

These lords of the line drive storm the field this very Saturday with cases so compelling that FBI Director Hoover may demand a gander at their files. Reyes COULD very well be nearing the end of his Metropolitan line. Braun COULD very well be damp from bathing in Milwaukee’s best…champagne, that is. Kemp’s COULD very well be the head that hangs heavy from the specter of wearing the elusive triple crown. And there are moundsmen in Philadelphia, Florida and San Diego finery who will do their best to have a say in who prevails pre-eminently in this race to reach base.

Stay tuned, Mr. and Mrs. America. Baseball hasn’t offered this kind of old-timey gallop to glory since youngsters were required by an act of Congress to learn how to spell “Yastrzemski”!

by Greg Prince on 23 September 2011 1:09 pm Welcome to The Happiest Recap, a solid gold slate of New York Mets games culled from every schedule the Mets have ever played en route to this, their fiftieth year in baseball. We’ve created a dream season that includes the “best” 148th game in any Mets season, the “best” 149th game in any Mets season, the “best” 150th game in any Mets season…and we keep going from there until we have a completed schedule worthy of Bob Murphy coming back with the Happy Recap after this word from our sponsor on the WFAN Mets Radio Network.

GAME 148: September 21, 2001 — METS 3 Braves 2

(Mets All-Time Game 148 Record: 19-28; Mets 2001 Record: 75-73)

Matt Lawton hit 3 home runs during his brief 2001 term as a Met, each of them prior to the bottom of the eighth of the game of September 21, an inning he happened to lead off by grounding out to Braves shortstop Rey Sanchez. Edgardo Alfonzo swatted 15 from Opening Day until he was walked by Steve Karsay with one out in that same frame. The 2001 home run totals, up to that bases on balls, of other Mets who batted from the first inning through the seventh inning that Friday night:

• Robin Ventura: 20

• Tsuyoshi Shinjo: 10

• Todd Zeile: 9

• Jay Payton: 7

• Rey Ordoñez: 3

• Bruce Chen: 0

• Joe McEwing: 7

Combined, those nine Mets had hit 74 home runs in the first 147 games of that Mets season. None had hit one out in the 148th, which was nearing completion when Alfonzo walked and Desi Relaford was sent in to pinch-run for him. While several of those Mets seemed unlikely to hit a homer on veritable demand, it wasn’t inconceivable that a few of them might take an Atlanta pitcher deep. Fonzie, Robin and Shinjo were all in double-digits. Zeile, Payton and McEwing had certainly homered enough that year so it wouldn’t be a novelty.

Yet none of them did homer on September 21, 2001. Mike Piazza, however, did. Mike Piazza hit his 34th home run of the season after Alfonzo walked. It put the Mets ahead 3-2. They’d go on to beat the Braves by that same score.

By now you no doubt recognize the home run in question as the most famous home run hit by any Met in the half-century that there have been Mets. It didn’t end a game. It didn’t ensure a playoff berth or a postseason series victory. It was an eighth-inning home run on a night whose cachet was generated less by competitive context than by the simple fact that more than 40,000 New Yorkers gathered at Shea Stadium to watch a baseball game ten days after terrorists destroyed the World Trade Center and killed more than 2,700 human beings in the process.

A game, yes. But also a civic memorial service and a municipal grief counseling session for more than 40,000. And that was just Friday night. In the days before, the Shea parking lot was where recovery efforts were staged — led at first by Bobby Valentine and aided by Mets players before their schedule resumed in Pittsburgh on September 17. And that was just part of what the Mets did between the stoppage of play on September 11 and its resumption six days later. The players offered themselves up as solace at hospitals and firehouses. When they were back on the field against the Pirates, they wore the caps of the FDNY and the NYPD and the PAPD, all of which lost members who rushed into burning buildings to save total strangers.

The Mets’ overall presence may have been no more than a slight psychological balm for the grieving and the shaken, but it was what a baseball team could give, and the Mets gave it.

As for the game that is generally remembered as more than a game, there was somberness, there was lingering unease and there was a handful of electrifying performances. Among those belting our their best on September 21, 2001 were Diana Ross with “God Bless America,” Marc Anthony with “The Star Spangled Banner,” Liza Minnelli with “New York, New York,” and Mike Piazza with the go-ahead home run off Karsay.

As Fox Sports Net New York focused on the almost dissonant cheering in the Picnic Area bleachers after Mike rounded the bases, Howie Rose emphasized how Piazza’s ball metaphorically reached beyond the scoreboard:

“And why is baseball back? Why was it so important to give fans a few hours to forget about their troubles? Those firefighters smiling — because of a baseball game in Flushing.”

Piazza’s solo was the most memorable star turn of them all, but nothing that Friday night was about standing alone in a spotlight. It wasn’t about any one person. It was about thousands of people, too many of whom could not be at Shea Stadium. It was about the thousands they left behind and the millions who mourned for them. It remains remarkable to understand that the act of going to a Mets game — no matter the opponent, no matter the standings — could represent so much to so many.

Though it’s probably worth noting from a purely baseball standpoint, the opponent was the archrival, first-place Atlanta Braves, whom the Mets had battled so fiercely through Valentine’s tenure as manager, and that the standings were something the Mets were rapidly climbing. The two teams embraced as part of a pregame show of unity, but at the end of the night, it couldn’t help be noticed (if you were so inclined) that New York had moved to within 4½ of the top spot in the National League East. That was a nine-game improvement from where they sat in the middle of August.

And in the center of everything — the final score, the psychological boost, the sense that maybe life does go on — was Mike Piazza. There’s no tangible reason it had to be Piazza who hit the home run that recalibrated our municipal emotions. It could have been Ventura or Alfonzo or Shinjo. In theory, it could have been Ordoñez.

But if you were at all cognizant of the Mets during his eight-season tenure in orange and blue, you knew it had to be Piazza. These types of moments always found Piazza. Or maybe Piazza and the moments always met in the middle. Anybody who would go as deep as Piazza did on a night that ran as deep as that one did would deserve to be remembered, but it’s near-impossible to picture anybody else doing it. On some other Friday night in some other circumstance, sure, anybody could swing and connect. Not that night. That was the sort of thing Mike Piazza did. We accepted it as extraordinary and perfectly normal, which is what the 40,000+ in attendance were seeking on September 21, 2001, ten days after the events of September 11, 2001. We as Mets fans went on to hold it fondly and we hold it still. We hold the days and nights of Mike Piazza in the same regard.

It’s a moot question, but if the home run had come off the bat of another Met, would we have embraced it immediately and continued to grip it like it mattered beyond a 3-2 lead in the eighth?

Honestly, it’s probably never seriously occurred to any Mets fan that it could have been anybody else.

Now and again from 1998 to 2005, Mike Piazza stepped up and played the hero for the Mets. On September 21, 2001, on the heels of ten days that sent a city reeling, we realized that’s exactly what a baseball player who hits a big home run is doing: playing. Piazza, we understood, wasn’t a hero. But at a Mets game — specifically that singular Mets-Braves game — nobody could have possibly filled the role better.