The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 14 June 2011 3:13 pm Welcome to The Happiest Recap, a solid gold slate of New York Mets games culled from every schedule the Mets have ever played en route to this, their fiftieth year in baseball. We’ve created a dream season consisting of the “best” 61st game in any Mets season, the “best” 62nd game in any Mets season, the “best” 63rd game in any Mets season…and we keep going from there until we have a completed schedule worthy of Bob Murphy coming back with the Happy Recap after this word from our sponsor on the WFAN Mets Radio Network.

GAME 061: June 14, 1965 — Mets 1 REDS 0 (11)

(Mets All-Time Game 061 Record: 21-28; Mets 1965 Record: 21-39-1)

There was rarely a penalty for any pitcher deciding to pitch the game of his life versus the New York Mets in their first four years. Ask Jim Bunning, whose 1964 perfect game at Shea Stadium raised his profile so high that it probably edged him into the Hall of Fame and maybe Congress. Ask Sandy Koufax, who would pitch plenty of his games of his life before he was done but chose the 1962 Mets for his first no-hitter. Ask most every ace moundsman nine National League staffs sent to face the basement babies throughout ’62, ’63, ’64 and well into ’65.

But don’t ask Jim Maloney. He didn’t get to take full advantage of excelling against the Mets, not on this Monday night at Crosley Field. But, oh, did he excel, and oh, was he taking advantage of the generally easily duped Mets.

From striking out Billy Cowan to lead off the game to striking out the side in the third and striking them out again in the eighth, Maloney was untouchable. His only imperfection was walking Ed Kranepool to open the second…and choosing the wrong night to go so long without being touched.

His opposite number on the mound was Frank Lary, known in his American League days as the Yankee Killer, but he was doing an admirable job of snuffing out Reds. He wasn’t as close to flawless as Maloney, but for eight innings, he did what he had to do, holding Cincinnati to five hits, three walks, a hit batsman and — this is key — no runs. In the top of the ninth, Casey Stengel pinch-hit for Lary with Joe Christopher, but Maloney struck him out. He did the same to Cowan for the third time in the evening.

By the middle of the ninth, Jim Maloney had faced 28 Mets batters. One of them walked. Twenty-seven of them made outs. Fifteen of them struck out. But Maloney wasn’t winning. He was only tying because of Lary, also known as the Mule. Frank was at his most mulish in the eighth when after hitting Tommy Harper, Harper stole second and raced to third on Chris Cannizzaro’s bad throw. With the go-ahead run ninety feet away, Lary grounded Pete Rose back to the mound to erase the Red menace.

Met defense had been surprisingly obstinate, too…after a fashion. In the fourth, Vada Pinson made it second on a stolen base attempt in which Cannizzaro’s pitchout worked beautifully until shortstop Roy McMillan dropped the throw. Gordy Coleman (who would later make a dazzling stop on the Mets’ only bid at a hit in regulation) continued his at-bat and struck out, but strike three got by Chris, who chased the passed ball. While he did so, Pinson kept running from second. Cannizzaro found the ball and fired it to Lary, who tagged him at home.

In the bottom of the ninth, it fell to Mets reliever Larry Bearnarth to display a little stubbornness, and he proved plenty recalcitrant. Pinson flied to rookie Johnny Lewis in right before Frank Robinson drew a walk. But Bearnarth bore down, getting Coleman to foul to Gonder (who had replaced Cannizzaro behind the plate) and Deron Johnson to ground to McMillan, forcing Pinson at second.

For Maloney to cash in on his incredible night’s work, he’d have to keep going. So he did. Chuck Hiller lined out to start the tenth. Charley Smith struck out swinging. Kranepool stuck out looking. Maloney had now pitched ten hitless innings and collected seventeen strikeouts. “A catcher’s dream,” Cincy backstop Johnny Edwards would call him.

Yet he still wasn’t winning.

An Edwards single to lead off the bottom of the tenth and a sacrifice of pinch-runner Chico Ruiz by Leo Cardenas got a Red into scoring position for the fourth time all night, but Ruiz never got past third. It was 0-0 heading to the eleventh.

Lewis led off for the Mets. On a 2-1 pitch, he homered to center. There — just like that Maloney was not only not winning, he was losing, 1-0. He’d recover to strike out Swoboda for his 18th K of the game and two batters later, after allowing a single to McMillan, get a double play ball out of Gonder, but the spell was broken. Bearnarth made sure it stayed that way by pitching a scoreless eleventh, and the Mets came away with a 1-0 win.

Despite being no-hit for ten innings. Despite being struck out eighteen times. Despite being the 1965 Mets.

“I can’t help but feel good,” Lewis, who had struck out thrice, said afterwards. “But it was a heartbreaker for Maloney to lose. He threw good, real good. In fact, I never saw a pitcher throw as hard to me as Maloney did.”

What was hard on Maloney was losing the game of his or most pitchers’ lives. “I’d just as soon win ballgames as pitch a no-hitter,” the flamethrowing righty insisted before taking his postgame shower, though he acknowledged he knew the no-no was in progress and that he really wanted it. He may not have felt terribly enriched by the experience of losing a game he judged “by far the best I’ve ever pitched,” but Reds owner Bill DeWitt immediately announced a $1,000 raise for Maloney, big money in those days for the son of a California car dealer.

Not bad for losing to the last-place Mets.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On June 13, 1988, David Cone was making a habit of not giving up the ball. Eleven days after going 10 innings in an eventual 13-inning win over the Cubs, Coney found himself working overtime once more. Versus St. Louis at Shea, he had given up only one run in nine innings (on a Bob Horner sac fly in the fourth), so Davey Johnson let him ride. Cone gave his manager no cause to regret the decision, retiring Tony Peña, Luis Alicea and pinch-hitter Duane Walker — up for Card starter Larry McWilliams, who had gone nine — in order. The Mets got Kevin McReynolds to third base in their half of the inning and chose to pinch-hit for Cone. Alas, Lee Mazzilli popped to third. The teams kept playing until the twelfth, when Mazz, who stayed in the game at first, made amends by singling home Wally Backman with the decisive run. The bulk of the pitching this Monday night was performed by Cone, but the 2-1 win went to Randy Myers, who hurled two perfect innings of relief. More than just another win for the East-leading Mets, the game marked the last time a Met starting pitcher pitched ten innings twice in the same season, let alone month.

GAME 062: June 11, 2005 — METS 5 Angels 3 (10)

(Mets All-Time Game 062 Record: 25-24; Mets 1965 Record: 32-30)

It wasn’t an easy assignment awaiting Marlon Anderson. He was coming off the bench to pinch-hit against one of the best relievers in baseball, one he had seen only once before. Then again, Marlon Anderson was one of the best pinch-hitters of the National League in 2005, having connected for a dozen pinch-hits since signing as a free agent with the Mets.

Still, he was going to be facing Francisco Rodriguez of the recently redubbed Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim, the 23-year-old fireballer they didn’t call “K-Rod” for nothing. As if there was some doubt to the kid’s effectiveness in this Saturday night Interleague Shea showdown, Rodriguez had just struck out David Wright to start the bottom of the ninth. The Mets trailed 2-1 and were down to their final two outs when Willie Randolph chose Anderson to hit for fellow utilityman Chris Woodward.

Anderson chose this moment to do something no Met had ever done before, on a 3-1 pitch from K-Rod. We pick up the action from Gary Cohen on WFAN:

Fastball driven in the air toward right-centerfield…chasing back is Finley…on the track, reaches out…

CAN’T GET IT! Kicks it away! It’s rolling toward the corner!

Anderson around second! He’s on his way to third! Finley’s tracked it down! Anderson is being…WAVED AROUND! He’s comin’ to the plate…the relay throw…he slides…

SAFE!

It’s an inside-the-park-home run! And it ties the game!

Marlon Anderson with an inside-the-park home run…he is shaken up…Jose Molina arguing the call, Mike Scioscia out as well, but Marlon Anderson has tied the game at two and two with an inside-the-park home run. Finley tried to field it on the warning track, kicked it toward the corner, and Anderson came all the way around ahead of the relay throw by Adam Kennedy…

Anderson still down on his knees as Mike Herbst and Willie Randolph look after him, but with his FIRST home run as a New York MET, Marlon Anderson has tied the game, and as he gets to his feet, he gets a ROUSING ovation from the crowd at Shea Stadium!

A stunning turn of events, and not just because it was the first pinch-hit inside-the-park home run in New York Mets history. Consider that Anderson was not blessed with great speed, so no wonder he was down on his knees when the play was over. Consider that he hit it between two of the great outfielders of their time, Steve Finley in center and Vladimir Guerrero in right, but the ball eluded them both. Finally, consider what the television replays showed as Anderson huffed and puffed his way around the bases.

He was blowing bubbles. Chewing bubble gum and blowing bubbles from it while tying the score at three.

Marlon was hardly the only star of what became a 5-3, ten-inning Mets win. Kris Benson had pitched seven strong innings, allowing his only two runs on a double play grounder to Bengie Molina (later replaced in a double-switch by his brother Jose) and a Kennedy sac fly. He got his last out when Carlos Beltran robbed Molina (Bengie) of a two-run homer with a leaping grab at the center field wall. Aaron Heilman followed with two scoreless frames. After Anderson’s PHITPHR — and K-Rod’s subsequent strikeouts of Kaz Matsui and Doug Mientkiewicz — Braden Looper was nicked for an unearned run in the tenth. Jose Reyes, turning 22 that Saturday, opened the bottom of the tenth by reaching first base on a pop fly over third that fell into very shallow left. He moved to second on Mike Cameron’s seven-pitch walk against Brendan Donnelly and, after Beltran and Mike Piazza struck out, stole himself a birthday present — third base — with two down.

That little surprise came on the eighth pitch of Donnelly’s battle to the bone versus Cliff Floyd (the Angel reliever thought time had been called). Floyd, healthy and thriving as a Met after two injury-riddled seasons, jumped on the ninth pitch from the rattled Donnelly — who threw 32 pitches in all in the tenth — and sent it soaring into the Flushing night for a three-run game-ending homer.

The win went to Looper, the walkoff mob surrounded Floyd (whose epic at-bat included a drive to right that appeared homerbound before hooking foul), but it was Anderson, 31, who created the indelible image of the Bazooka blast. It may not have been as majestic a shot as Floyd’s, but it sure was something to see. Anderson turned on as many afterburners that were available to him once his ball hit Finley’s knee. Third base coach Manny Acta waved him toward the plate, and Marlon blew bubbles and sucked wind until he was all the way home.

In the annals of New York National League inside-the-parkers, it may have been the most dramatic of the genre since 33-year-old Casey Stengel sped as best he could around the bases to give the Giants a 5-4 lead in the top of the ninth in the opening game of the 1923 World Series at Yankee Stadium. That was a trek Damon Runyon captured it 82 years earlier in prose very much of its time.

With apologies to Mr. Runyon, then…

This is the way old “Marlon” Anderson ran Saturday night, running his home run home.

This is the way old “Marlon” Anderson ran running his home run home in a Met victory by a score of 5 to 3 in the second game of an interleague series in 2005.

This is the way old “Marlon” Anderson ran, running his home run home, when there was one out in the ninth inning and the score was Angels 2 Mets 1 and the ball was still bounding inside the Met yard.

This is the way—

His mouth wide open.

His warped old legs bending beneath him at every stride.

His arms flying back and forth like those of a man swimming with a crawl stroke.

His flanks heaving, his breath whistling, his head far back.

Angel infielders, passed by old “Marlon” Anderson as he was running his home run home, say “Marlon” was muttering to himself, adjuring himself to greater speed as a jockey mutters to his horse in a race, that he was saying: “Go on, Marlon! Go on!”

People generally laugh when they see old “Marlon” Anderson run, but they were not laughing when he was running his home run home last month. People — 34,000 of them, men and women — were standing in the Met stands and bleachers out there in Flushing roaring sympathetically, whether they were for or against the Mets.

“Come on, Marlon!”

The warped old legs, twisted and bent by many a year of baseball campaigns, just barely held out under “Marlon” Anderson until he reached the plate, running his home run home.

Then they collapsed.

They gave out just as old “Marlon” Anderson slid over the plate in his awkward fashion with Jose Molina futilely reaching for him with the ball. “Larry” Young, the Major League umpire, poised over him in a set pose, arms spread wide to indicate that old “Marlon” was safe.

Half a dozen Mets rushed forward to help “Marlon” to his feet, to hammer him on the back, to bawl congratulations in his ears as he limped unsteadily, still panting furiously, to the bench where Willie L. Randolph, the chief of the Mets, relaxed his stern features to smile for the man who had tied the game.

“Marlon” Anderson’s warped old legs, neither of them broken not so long ago, wouldn’t carry him out for the top half of the next inning when the Angels made a dying effort to undo the damage done by “Marlon.” His place in the lineup was taken by “Braden” Looper, whose legs are still unwarped, and “Marlon” sat on the bench with Willie Randolph.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On June 14, 1963, a Met of great renown achieved a long-in-the-making career milestone. Since the Mets hadn’t been around even two years and they had done little as a unit to earn anything but infamy, it figured that most of what this Met had done before was done as something else altogether. Nevertheless, Duke Snider wore a Mets uniform as he blasted a first-inning, two-out pitch from Bob Purkey out of Crosley Field. When Snider drove himself and Ron Hunt home, it gave the all-time Dodger great the 400th home run of his career, making him the eighth player in big league history to hit that many. The Mets would go on to beat the Reds, 10-3, and sixteen summers later, a plaque would hang in Cooperstown featuring Snider’s likeness and a notation that somewhere between 1947 and 1964, Snider logged time with NEW YORK N.L.

GAME 063: June 21, 1984 — METS 10 Phillies 7

(Mets All-Time Game 063 Record: 27-22; Mets 1984 Record: 36-27)

If Believing with a capital “B” hadn’t been much in vogue at Shea Stadium for the previous ten years, there was a pretty good reason: there had been little to Believe in, certainly not in the vein of when Belief was last in style there.

1973 was a very long time removed from 1984, and it wasn’t just the chronology that made it seem so distant. The Mets had only now and then sniffed contention since the autumn Tug McGraw made the phrase “You Gotta Believe” part of the Mets’ Talmud. They certainly hadn’t made the most of their fleeting acquaintance with success in the ensuing decade, but 1984 was unfolding in a very different, very pleasing manner.

After losing their first Opening Day since 1974, the ’84 Mets won their next six games. Fueled by two sterling rookie pitchers, Dwight Gooden and Ron Darling, and led by first-year manager Davey Johnson, exploded expectations, never fading from contention as April became May and May became June. Once they reached seven games above .500 on June 14, it was as high as they had gone beyond break-even since 1976 ended. As summer dawned, they found themselves in a three-way dogfight for first place with the similarly surprising Chicago Cubs and the perennially contending Philadelphia Phillies. They Mets entered this Thursday Shea matinee against the Phils in second place, a half-game behind their neighbors to the south. Overall, it was as good a position as they’d been in this late in a season since 1975.

Most Met seasons were effectively over by June. This one was just getting to the good part.

A tight 1-1 duel between starters Walt Terrell and Charlie Hudson veered in a completely different direction come the bottom of the fifth as a Juan Samuel error helped the Mets score five times and chase Hudson. Their 6-1 lead, however, began to crumble in the top of the seventh when Terrell walked his first two batters and Jeff Stone beat out a bunt (his third hit of what would be a 4-for-5 day) to load the bases. Terrell left in favor of Jesse Orosco, but Orosco allowed a pair of two-run singles to Mike Schmidt and John Wockenfuss and, before long, the Mets were down 7-6.

It was a familiar script from what life had been like at Shea since 1973, but the Mets called the press box and bellowed, “Get me rewrite!” Or something like that. Phillie reliever Bill Campbell opened the home seventh by allowing back-to-back singles to Danny Heep and Hubie Brooks. Ron Hodges, one of two 1973 Mets still extant in Flushing, grounded to second, resulting in a fielder’s choice to first, scoring Heep from third. Now it was tied. George Foster, getting the day game off, was brought on to pinch-hit for shortstop Jose Oquendo and was intentionally walked to set up a double play.

Orosco was due up, and a pinch-hitter was in order. Usually in a late-game situation, that would be the other 1973 Met on the active roster, Rusty Staub. A cursory glance at Campbell would lead one to infer it would definitely be Staub. He was a righty and Rusty was a lefty. Perfect matchup…except for one thing. Rusty couldn’t hit Campbell. Dating back to 1976, when Staub was with Detroit and Campbell was with Minnesota, he didn’t hit him…at all. Over fourteen at-bats, Rusty was 0-for-14 versus this pitcher. And if any manager in 1984 was aware of matchups, it was statistic-savvy, computer-literate Davey Johnson.

But Johnson also knew Rusty Staub was one of the best pinch-hitters ever and figured he was due. Besides, Rusty, like Ron Hodges, had been around Shea the last time the Mets made a move on first place. Hence, as if 1973 had just been reincarnated, Rusty swung and singled home Hubie with the go-ahead run. And if the ghosts of pennant races past didn’t already seem present, Phillie right fielder Sixto Lezcano misplayed a Wally Backman foul fly, extending the second baseman’s at-bat long enough for him — facing Jim Kern, who had replaced Campbell — to manage a run-scoring grounder that plated Foster. The Mets were up 9-7.

Doug Sisk negotiated a tough top of the eighth and kept the margin at two. In the bottom of the inning, Kern (a Met on paper for two months in 1981-82 before being sent to Cincinnati as part of the Foster deal) loaded the bases for Hodges who, per the prevailing Belief of the day, walked to drive in a tenth New York run. The Mets led 10-7 and Sisk ended it that way.

The Mets leapfrogged the Phillies to take a half-game lead in the N.L. East on the first day of summer. Their ascension occurred sooner than it did in 1973 (when it happened on the first night of fall), but with Hodges and Staub coming through when it counted, it felt a lot like that year of blessed memory. Except that Tug McGraw, in his final season as a player, was languishing on the Philadelphia disabled list.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On June 20, 1985, the Mets didn’t win that year’s division title but they did everything they could to take care of the previous year’s business, understanding it would pay definite dividends in the present. The Cubs had come into Shea for a midweek quartet of games so big to both team’s fortunes that a stadium attendance record for a four-game series was set: 172,092. Every Mets fan who paid his way into Shea got his money’s worth when the Mets swept all four from their former nemeses from the Windy City. The ’84 division champs came to New York on a five-game losing streak. They left it absolutely reeling, with nine losses in a row. The Mets, on the other hand, were surging in the general direction of first place after Sid Fernandez struck out ten Cubs in six innings and George Foster drove in four runs on one grand slam swing in the third inning to complete the sweep. The good it did the Mets in the standings was plain as day following this matinee — they stood in a flat-footed second-place tie with St. Louis, a half-game back of Montreal for the lead in the East. What it meant to the Mets psychically a year after the Cubs beat them out for first? Let’s just say that when the Shea public address system blared Paper Lace’s 1974 hit “The Night Chicago Died” after this Thursday afternoon capper, nobody in New York questioned the taste behind the musical choice.

Congratulations to David Hurwitz, Mickey Lambert and Ken Mattucci for winning our 1986 World Series DVD Happiest Recap Quiz. And congratulations to you if you order what they won from A&E Home Entertainment.

by Jason Fry on 14 June 2011 12:27 am To be clear, I love Ken Burns — I’m a sucker for every move in his arsenal, from the slow pans of old photos to the sage talking-head in his (or her) study. And I read Bart Giamatti’s invocation of baseball and the seasons at least once a year and wind up sniffling. What I love about baseball, and what this blog celebrates, is how the games get bound up with our lives. We have nothing to do with the games’ outcomes, and nothing we do is reflected in a box score, but each baseball season gets woven into our own, with what we were doing and thinking and feeling bound up with what happened on the field. I’ll always be able to tell you that for Game 6 I was sitting on the end of a bed in a motel room in Lawrence, Mass. with my Mom the only other one awake and believing and that for the 10-run inning I was in the mezzanine with Greg and Emily and Danielle and for the horrible collision between Beltran and Cameron I was walking over West Street from the World Financial Center. It doesn’t matter in the historical record, but it does — immensely — where our own chronicles are concerned.

The thing is, sometimes those mystic chords of memory can drown out what actually happened on the field. Which is what happened with tonight’s game.

Let’s rewind. Emily and I spent the weekend up in Massachusetts for her 25th high-school reunion, with Joshua in tow, and came back early this evening. In my younger years I spent many a foolish evening driving hell-for-leather between distant points, holding on to the faintest strand of the Mets’ radio broadcast as distance and storms chewed away at it. Those nights are mostly gone: I now live in the same city as my team, watch them on a humongous, crystal-clear TV, and even when I’m on the road the telephone I carry in my pocket can summon up WFAN’s feed with a few taps on its glass screen.

It’s Jetsons stuff that would have left the 20-year-old me agog and eager for such a wonderful world to hurry up and arrive. And he would have been right, mostly. Except Friday night MLB’s servers were on a smoke break, and no matter what we did the radio feeds on At Bat ’11 returned only the message CONNECTION ERROR. So up through Connecticut and out across Massachusetts we went with the old analog radio as companion, and by the far side of Worcester WFAN was fading in and out, whining and dipping and threatening to be replaced by the babble of some other station on a nearby frequency.

You know what? It was great. Emily and I were in front, listening to the Mets wallop the Pirates and complaining good-naturedly about Wayne Hagin, while Joshua slept in the back and all was darkness outside. I kept up vaguely with Saturday and Sunday’s games on Gameday, but 7:10 tonight found us somewhere around White Plains, rocketing the rental car down the Hutch having thoroughly enjoyed our long weekend but also eager to get home to our regular places and rituals. Being present for the Mets game was one of those rituals — the first familiar piece to fall back into place, in fact. Joshua put aside his book and cheered on the Mets and asked questions about rookies and batting averages and the game was our companion as we got ourselves back to Brooklyn. It kept Emily company on the radio as she returned the rental car; in the house, I turned on the TV and there were the Mets again in big beautiful living color, for me to keep an eye on as I sorted through the mail and the newspapers and for Joshua to peer at from the bath. The kid went to bed and Emily came home and we did more restoring of order and moved downstairs to our own bed for the final inning. The Mets lost, but they had shepherded us back to where we belonged, and so that was OK.

Well, except someone please yank the needle off that scratchy old acetate of “Ashokan Farewell” for a moment. Because while all of that stuff above is true, and deeply felt, it wraps tonight’s actual game in a blanket that’s warm but also obscures some pertinent facts. Like the Mets lost because a) Jose Reyes got called for a dopey obstruction play; b) Daniel Murphy screwed up on the basepaths; c) Lucas Duda screwed up on the basepaths and d) Manny Acosta and Tim Byrdak failed on the mound. In doing so, the Mets once again failed to move to .500. They missed out on stashing away another victory in the absence of David Wright and Ike Davis and Johan Santana. They wasted a good start from the enigmatic Mike Pelfrey. They left their wraparound series in Pittsburgh with a split instead of the sweep they could have had if they’d played better ball.

That’s harder to render in sepia tones.

Maybe years from now Joshua will strap his EKG headset on to project an entry into his holographic memory blog and it’ll be recalling how when he was a kid he put down a book by the guy who wrote The Lightning Thief because the Mets were on the radio and an obscure Met named Justin Turner was one of his heroes as an eight-year-old and some of his favorite early memories are of talking baseball with his Mom and Dad while on one of their nutty car trips. Should that happen, I doubt he’ll remember that Reyes got called for obstruction and the next morning he found out the Mets had shot themselves in the foot a couple of more times and lost. He may even spend an hour poring over some advanced version of Retrosheet in an effort to figure out what game it might have been — I’ve been stuck doing that myself. Which is OK — the feeling and the memory will be the important part.

But that other part should be recorded too. And so here it is: It was a joy to slip back into our lives, starting with listening to the Mets as a family.

It would have been even more joyous if the Mets hadn’t played so crappily.

by Greg Prince on 13 June 2011 11:30 am What do you mean you don’t have the boxed DVD set from the 1986 World Series? What do you mean you’ve lived this long without eight discs that include each game of that blessed Fall Classic (yes, even the losses use Games 1, 2 & 5 as coasters or give them to your cats) plus the final game of the NLCS, all sixteen scintillating innings of it?

Well, let’s put an end to that right now. A&E Home Entertainment wants to award three such boxed sets to Faith and Fear readers right now. To help them do you the solid of the year — or quarter-century, as it’s turned out — I will now provide you with one of the easiest contest quizzes in FAFIF history. All the answers to the questions I’m about to ask you have been published on this blog since April 5, 2011, either on a Tuesday or a Friday, in your favorite twice-weekly feature, The Happiest Recap.

For those of you who have committed every last word of every one of my painstakingly researched, meticulously crafted essays to memory, this will be a snap. For the rest of you slackers, you can just look ’em up (if you’ve never clicked on the tag “The Happiest Recap” at the bottom of one of those bad boys, this would be a good time to do so) and track down what you need. It’s an open-blog quiz.

First three FAFIFites to e-mail all twenty correct answers (hint: specificity helps) to faithandfear [at symbol] gmail [dot] com will be our three winners. All decisions of the judge are final.

***UPDATE: WE HAVE OUR WINNERS. THANKS FOR PLAYING.***

For those who don’t win this contest, here’s a link to order the set. It’s well worth having, even if it doesn’t come free to you.

But let’s hope it does. Good luck!

1) Who relieved Tom Seaver in his first win?

DON SHAW

2) Who made the final out of Bob L. Miller’s first Mets win since 1962?|

RON CEY

3) Who homered to lead off the game Armando Benitez ended by surrendering a home run to Carlos Delgado?

RANDY WINN

4) Who was the last batter Victor Zambrano faced as a Met?

ANDRUW JONES

5) What musical special aired on NBC opposite the game that featured Darryl Strawberry’s first major league home run on WOR-TV?

MOTOWN 25

6) Who scored the first run against Dwight Gooden in his major league debut?

DENNY WALLING

7) Who collected the last base hit Tom Seaver gave up before the Mets traded him?

JOE FERGUSON

8) Who homered twice to support Dick Rusteck’s four-hit shutout?

EDDIE BRESSOUD

9) Whose flyball did Mookie Wilson misplay to put the Mets behind 6-5 before his home run off Bruce Sutter beat St. Louis 7-6?

TITO LANDRUM

10) How many home runs did Mike Piazza need to hit in 2004 to break Carlton Fisk’s career home run record for catchers?

FIVE

11) Whose grand slam precipitated the appearance of John Cangelosi on the cover of Sports Illustrated?

RYAN THOMPSON

12) What lefty did Terry Francona have warming up in the ninth inning when Curt Schilling allowed five runs to the Mets?

JIM POOLE

13) How many pitches were thrown in the twenty-inning Mets-Cardinals game of 2010?

652

14) What was the name of the promotion Carvel sponsored at Shea Stadium on the day the Mets and Pirates wound up playing eighteen innings?

SUPER SUNDAE SUNDAY

15) What reliever did Larry Bearnarth replace prior to Bearnarth pitching ten innings of relief versus the Cubs?

TOM STURDIVANT

16) What Met player’s uniform lacked a name on the back when Steve Henderson homered to beat the Giants on June 14, 1980?

CLAUDELL WASHINGTON

17) Who threw the pitch that resulted in the home run that would come to be commemorated by a marker in the left field Upper Deck at Shea Stadium?

LARRY JASTER

18) Who made the final out of the Mets’ first home win ever?

FRANK TORRE

19) Who struck out directly before Omir Santos’s video-review home run at Fenway Park?

JEREMY REED

20) One week before Jack Fisher won an eleven-inning start, he lasted 11⅔ innings only to be removed for what reliever?

DON SHAW

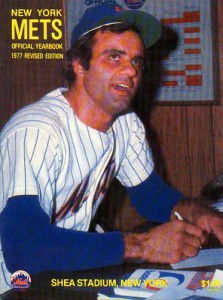

by Greg Prince on 13 June 2011 2:09 am  The debut of Mets Yearbook: 1977 somehow eluded me last week, but luckily I noticed it was coming on after Sunday’s game and learned it will be repeated Tuesday afternoon at 1:30, so consider this your DVR alert. The debut of Mets Yearbook: 1977 somehow eluded me last week, but luckily I noticed it was coming on after Sunday’s game and learned it will be repeated Tuesday afternoon at 1:30, so consider this your DVR alert.

Sadly, the 1977 season itself did not elude me, and even less fortunately, it was repeated in spirit throughout 1978 and 1979, so be warned that if you watch this particular edition of the best show on television, you will (especially if you lived sentiently through 1977 as a Mets fan) require the latest the pharmaceutical industry has to offer in the way of antidepressant medication.

Ohmigod, Wes Westrum might have muttered had he been paying attention to his old posting, wasn’t 1977 awful? I’ll assume you, as a FAFIF reader and therefore de facto intermediate student of Mets history, understand why. Yet you’ll want to watch Mets Yearbook: 1977 anyway. You will want to see propaganda take off in new and unpredictable directions. You’ll want to hear new manager Joe Torre explain (from a horse farm in an undisclosed location) how he’s stopped thinking of the atrocity that was committed on June 15 of that year as the Tom Seaver trade and has begun to think of it as the Steve Henderson trade.

Kudos to anyone who can think of it at all and look forward to coming to work the following year, but Torre is upbeat about his “new look pitching staff”. Ed Kranepool (whose reams of service time is featured early, a dead giveaway as regards how few actual highlights a particular highlight film encompasses) visits his old high school ballfield in the Bronx and is as upbeat as Ed Kranepool can possibly be, which is to say reassuringly grim. We also meet Lee Mazzilli and Steve Henderson, even if neither of them can enunciate worth a damn (and these were my favorite post-Seaver players). We are treated to a festival of leather jackets and out-of-control coiffure and a general late-1970s vibe of Shea despair.

Elliott Maddox is coming! Willie Montañez is coming! Tim Foli is coming back! Jerry Koosman isn’t going anywhere (yet)! And, in a moment of genuinely inspirational reportage, Jackson Todd survives a cancer scare. Plus there’s the great blackout of ’77; Doug Flynn complaining about the high cost of Big Apple living; the four great center fielders of New York lore alighting for Old Timers Day and inspiring Terry Cashman to write a song about three of them; Met wives playing softball; Jon Matlack’s kid running in circles before Dad is traded to Texas; Lenny Randle solving the third base problem (somebody’s always solving the third base problem on Mets Yearbook); and a parade of banners that the miserable management of this miserable team still had the good grace to permit on the field, making us wonder yet again why a beloved tradition that survived arguably the worst year in Mets history isn’t immediately revived by the club’s current cup-happy marketers. (Afraid the fans’ feet will ruin the grass for soccer?)

Mets Yearbook: 1977 is, either in spite of or because of its content, a triumph of the highlight film genre. You’ll never want to live through a 1977-style season again, but you won’t want to miss evidence that it actually occurred.

Image courtesy of “Mario Mendoza…HOF lock” at Baseball-Fever.

by Greg Prince on 12 June 2011 8:14 pm In one of those misbegotten seasons when Daniel Murphy doesn’t leave too soon on Jason Bay’s sacrifice fly but Angel Pagan forgets to brush a foot over second, Pagan is out at first before Murphy gets home — and Murphy likely leaves too soon anyway. But the whole thing is moot because Bay strikes out looking.

In one of those seasons we’re too used to, Pagan doesn’t catch Lyle Overbay’s high fly ball with his glove to the wall. The wall catches it and his glove gets there a second too late for it to count as anything but a trapped double — and it probably bounces off his glove and over the wall so that the opponents’ fireworks show is gloating rather than embarrassing.

In another season that isn’t this one the way this season is right now, Willie Harris comes up with two out and immediately makes it three out. Scott Hairston remains stuck on one home run forever. Chris Capuano patiently explains away his frustration at being saddled with another no-decision or loss. Jose Reyes doesn’t smile once when asked about the obvious toll the pressure is taking on him as he attempts to carry the club on his slender shoulders. R.A. Dickey may be ready soon to throw off a mound for the first time in weeks, or he may not be ready for a while. Carlos Beltran isn’t close to resuming baseball activities. Justin Turner toils away in Buffalo. Johan Santana is shut down until next spring. Terry Collins storms out of his postgame presser…again.

But that’s not this season. Not now it isn’t.

I don’t know what it will be before long. I’ve attended too many dadgum Met rodeos that went all to tarnation to allow me to completely buy into the exhilaration these 2011 Mets are providing more often than not of late. These are the same 2011 Mets who have yet to rise above .500 since April 6. Their most flattering relevant recent sample size — 7-3 since June 2 — isn’t large enough to have tipped the overall scales in their favor. Their long-term success — 27-20 since April 21 — hasn’t been, from an objective statistical standpoint, all that successful.

They’re a surprising 32-33 in 2011? They were 43-32 in 2010, 33-29 in 2009, 82-63 in 2008, 83-62 in 2007, 68-60 in 2005, 43-40 in 2004. I wouldn’t give you more than two plug nickels for the way those rodeos disintegrated when crunch time arrived.

Nevertheless, I watch the 2011 Mets bear down and hang with ’em. They scratch out the run they need to take a lead; they make the catch they need to preserve the lead; they kickstart the rally they need to extend the lead; and they dock serenely on the shores of the Allegheny with a tougher-than-it-sounds 7-0 win over Pittsburgh in Pittsburgh.

It’s not important to wonder how long this kind of thing might last. It’s important to enjoy that it’s going on now.

To support Roger Hess’s climb up Denali to raise funds for the Tug McGraw Foundation in honor of his friend David, who has fought so valiantly to beat his brain tumor, please visit here.

by Greg Prince on 12 June 2011 2:10 am Was it the lure of the Mets that crammed PNC Park’s third-largest crowd into the home of the Bucs the way only Greece, Ecuador and soccer draw throngs to Citi Field? Was it the promise of fireworks and Huey Lewis & The News postgame? (Can Huey Lewis really be considered “news” 27 summers after Sports?) Or is Pittsburgh turning on to its non-football, non-hockey, non-awful baseball team at last because, well, at last they’re not altogether awful?

Despite openly declaring them my doomsday team a couple of years ago, I tend to not consider the Pirates when they’re not on our dance card, but lately it’s been blacker and golder than usual, so learning that they’re both chasing mediocrity and not chasing away customers…that’s nice, I guess. When the Mets are at sublime PNC Park and the talk drifts to Manny Sanguillen and Al Oliver, you can’t help but hope that once they fall off our schedule, the Pirates somehow fall into contention in the N.L. Central. At a game under .500 and four behind St. Louis in the loss column, maybe they already have.

And what about us, whom I consider continuously? Are the Mets in contention in the N.L. East? They’ve been playing like a team that wins a lot for a little while now. It’s not quite the same as winning a lot — Saturday reminded us of the difference — but it’s made this season of low expectations one of medium reward…at least.

Examine the pertinent numbers that go into determining the c-word: The Mets are two games below .500, which is extraordinarily ordinary until you connect it to its distance from a playoff spot, which is, as we speak, 5½ out, with 98 to play. That’s borderline contending if there’s anything to contend for when there are still 98 to play. The two teams that hold provisional claim to the National League Wild Card are the last two teams we played, Atlanta and Milwaukee. And we just beat them each two out of three.

So why not us?

Well, ’cause we’re not going to, that’s why. I mean, c’mon. Look at these Mets. They’re playing about the best they possibly can and the best they have to show for it is six wins in their last ten games. 6-4: not bad. 6-4: pretty good. 6-4: not extraordinary.

Which is what the Mets are. I chuckle when I hear mentioned that if not for some shabby bullpen work, the Mets would have been on some hellacious winning streak of late. As if the bullpen isn’t part and parcel of the whole package. When the bullpen was untouchable, the outlier was so-so starting. Or not enough hitting. Or uncertain fielding. Or injuries. We overcome something sometimes but it overcomes us just as often. We’re not that good, teamwise.

Yet that’s OK. Honestly, it really is. It’s not very much fun to watch the Mets not convert ten hits into more than two runs against Pittsburgh. It’s not very much fun to watch nine Pirates leaping (or however many made rally-killing catches in the course of Saturday evening). It’s not very much fun to watch Chip Hale choose caution over the last, best chance the Mets had to tie the score in the eighth. It’s not very much fun to watch Daniel Murphy test positive for Guinness Stout…or play third base as if he had.

But these Mets are fun on their own terms, in their own dosage. They’re an almost-.500 club playing in small spurts at a .600 pace. Maybe the spurts will extend themselves. I’m guessing they won’t. Right now the starting pitching, all of it, is superb. It can’t last. It could, but it probably won’t. There have been downpours of basehits, but few bolts of lightning to generate runs all at once. There is admirable stick-to-it-iveness where guys playing out of position in fact play as well as they can out of position, but that’s not the same as playing really well overall.

If this is it, as Huey Lewis suggested in 1984, this isn’t the worst thing I’ve ever seen as a Mets fan. I’ve seen worse in 2010 and 2009 and I could keep going. This is fun enough. This is a season whose medium reward surpasses what we could have reasonably anticipated, both from when we had the 18-game start that inspired one blogger to use some form of the word “atrocious” 15 times and from when we saw our first and third basemen trip over each other and onto the DL from there.

Maybe it gets even better. Maybe these five starters are the goods more than I’m believing. Maybe the bullpen is done blowing up. Maybe Murph becomes a master of one or more of his trades. Maybe Reyes is the object of no trades. Maybe, maybe, maybe. Or maybe not.

Beats the hell out of definitely not.

To support Roger Hess’s climb up Denali to raise funds for the Tug McGraw Foundation in honor of his friend David, who has fought so valiantly to beat his brain tumor, please visit here.

by Greg Prince on 11 June 2011 5:10 am Kinda busy, kinda distracted. Mets score a run in the top of the first on no hits, I hear out of one ear. That’s nice, I think. But why didn’t we get any hits?

Three straight Pirate hits and the tying run right after, it is mentioned while I’m still doing something else. Damn, I think, that’s not good. Gee must not have it. He was bound to not have it eventually.

A single here, a single there. One by our Jose, one by their Jose. Each erased on a double play. Is it still tied? It is? Gee still in there? He settle down? What about Charlie Morton? Is he really going that well after last year going so poorly?

Is there any way I can use “Morton’s Stake House” as a headline tonight if we win and not have people think I can’t spell steak? And what does that even mean?

Not concentrating, still have things to do. Still kinda listening, kinda not.

Wayne, get to the point of your Three Rivers press box story already. I’m sure there is none.

Pagan doubles. That’s good. What’s that? He scores? So now we’re winning, right? The Pirates never did get more than that one run in the first. I guess Gee doesn’t not have it after all.

Duda did something? And now he scores? We’re up 3-1? This is a better game than I thought.

Tejada does something good. Tejada always does something good. How is it I was seemingly the only person in the world who wanted Ruben Tejada playing second base for this team this year from the get-go? Don’t wanna make it about me, but damn it, I was right to love this kid from the start.

Then again, I thought Tim Bogar and Luis Rivera got raw deals in 1994, so what do I know?

Hey, Reyes beat out a weird hop or something. So, what, the bases are loaded?

Turner…isn’t he slumping? Oh well, he couldn’t keep it up forever. Hey, Turner singled home two more runs! Guess he isn’t slumping. Where’s Reyes in all this? Scoring, that’s where. What is it now?

Mets 6 Pirates 1. Hey, I gotta start paying attention.

Pagan triples and scores. It’s 7-1. Time to sit down and focus. Lemme just find something to microwave.

Did Gary say Reyes homered? Sonofagun, Reyes homered! It’s 8-1! And it wasn’t like Reyes was trying to homer, so we can enjoy it, right? Reyes will be 28 tomorrow. Can everybody stop treating him like he’s 14?

Man, they gotta keep Reyes.

Gee’s still in there, huh? Gee gave up three hits to start the game and I assumed he was running out of luck. He’s not running out of anything, even gas. He’s gone seven and has gotten more effective.

Eight-one. This is great. Beltran’s being taken out for a pinch-runner up seven runs. You sure, Terry? Is a seven-run lead safe at PNC Park? It wasn’t safe for the Pirates at Citi Field. Don’t we usually find a way to blow these here? Maybe not.

Hey, look at Beltran with that big smile on his face talking to Duda. Didn’t I see something like that earlier in the season or maybe last September? Those two have a bond. Duda’s like the only Met who makes Carlos light up like that. Keith just said something about “that’s veteran leadership.” It’s not just two guys having a good time ’cause their team’s winning by seven runs?

Jason Bay’s not playing. I don’t miss him at all.

Gee in trouble, a little. Two on but two out and — and there’s a seven-run lead in the eighth. Calm down. Gee gets out of it by getting Xavier Paul to ground out. Pirates have had more Xaviers than anybody the last few years.

He probably isn’t gonna pitch the ninth. Nobody ever pitches the ninth. No Met starter, anyway. I wish everybody studied as many old box scores as I do just to appreciate how everybody used to pitch the ninth.

Jack Fisher was better than people probably realize, but I only look at the winning box scores, so of course I’m going to think Jack Fisher does nothing but win. And, let’s be honest: I don’t think anybody besides me walks around in 2011 thinking about how good or not good Jack Fisher was 45 years ago.

Just as well Dillon comes out. The kid was in a little trouble there before Xavier Paul. Man, if nothing horrendous happens, Gee’s gonna be 7-0. Gee hasn’t sucked since they were in Houston and he was probably trying to impress his pass list. Can somebody tell me why we weren’t supposed to take this guy seriously after he pitched so well last September?

Who’s in? Byrdak? Why not? Will Terry let him face lefties and righties with a seven-run lead? I feel like I just started watching this game and now I’m totally invested in it. C’mon Byrdak, don’t make this messy. I don’t wanna see Manny Acosta come in. I never wanna see Manny Acosta come in.

Nice slow grounder, Reyes to Tejada to Murphy…double play!

We win. That was fun.

To support Roger Hess’s climb up Denali to raise funds for the Tug McGraw Foundation in honor of his friend David, who has fought so valiantly to beat his brain tumor, please visit here.

by Greg Prince on 10 June 2011 5:07 pm Welcome to The Happiest Recap, a solid gold slate of New York Mets games culled from every schedule the Mets have ever played en route to this, their fiftieth year in baseball. We’ve created a dream season consisting of the “best” 58th game in any Mets season, the “best” 59th game in any Mets season, the “best” 60th game in any Mets season…and we keep going from there until we have a completed schedule worthy of Bob Murphy coming back with the Happy Recap after this word from our sponsor on the WFAN Mets Radio Network.

GAME 058: June 12, 1977 — Mets 3 ASTROS 1

(Mets All-Time Game 058 Record: 20-29; Mets 1977 Record: 24-34)

In so many ways, it was typical of every fifth day in the Mets’ life for the previous decade: a tight game in which great pitching beat good pitching and made up for light hitting. The starter went the route, as he had 165 previous times. He gave up one run in compiling his complete game, the 90th occasion in which he gave up no more than that while finishing what he started. He earned the win, as he had in 188 previous outings.

Yes, a 3-1 victory over Floyd Bannister and the Houston Astros, achieved by allowing only five hits and two walks while striking out six opponents was typical of what Tom Seaver had given the Mets approximately every fifth day since 1967.

Yet this was hardly just another game.

It would be the last appearance for Seaver in a Mets uniform until…well, nobody could say for certain this Sunday at the Astrodome. Certainly nobody wanted to. The hope was no more than another five days would pass before the ace of the Mets’ staff took the ball from manager Joe Torre the way he customarily had, same as he had taken it from Joe Frazier and Roy McMillan and Yogi Berra and Gil Hodges and Salty Parker and Wes Westrum. Tom Seaver was the single most reassuring fact of life for Mets fans. His nickname was The Franchise, but what he really was was our rock. Upon this rock we had built our dreams.

That rock wasn’t long for this land, however, and if everybody didn’t or couldn’t yet fully or officially acknowledge it, we knew the earth was moving under our feet.

Oh, you couldn’t necessarily tell it by listening to WNEW-AM that Sunday afternoon, where Bob Murphy, Ralph Kiner and Lindsey Nelson proceeded to tell the tale of the game inside the Dome, not the larger story that was roiling the world outside it. If you had read no newspapers that morning and picked up on none of the surreal trade talk surrounding the Mets’ best pitcher, all you would discern from the Mets’ original three announcers was that Seaver came to the bottom of the ninth with a 3-1 lead — one he helped construct with a sacrifice bunt in a two-run top of the eighth — and that he proceeded to get Jose Cruz to line to Dave Kingman and then a grounder back to the mound from Willie Crawford, which he handled himself and tossed to first baseman John Milner. That put Tom Seaver and the Mets two outs from the end. But then Joe Ferguson singled to left and Cliff Johnson worked a four-pitch walk.

As Wilbur Howard came into pinch-run for Johnson, Skip Lockwood continued to warm up in the Mets’ bullpen and Torre visited Seaver on the mound. “Seaver’s gonna stay in the ballgame,” Lindsey Nelson said matter-of-factly. “They wanted to talk it over.” Seaver finished talking with Torre, offered a word or two to home plate ump Frank Pulli, and turned his attention to the next Astro batter, righthanded second baseman Art Howe, hitting .288.

“Seaver is set. Runners lead first and second. Pitch is swung on and fouled off to the right side. It’s strike one.”

Howe fouled off the first four pitches he saw, before Tom wasted a fastball high and away to make the count 1-and-2. Seaver then looked into catcher John Stearns before firing a sixth pitch. “Again, Seaver comes set,” Nelson announced, before calling the next and final delivery of the day:

“Kicks and fires, and the pitch is swung on, HIT WAY BACK in left field…going back there is Kingman, he’s at the wall…KINGMAN MAKES THE CATCH! Leaning against the wall and the ballgame is over! Kingman at the three-ninety sign, made the catch leaning against the wall! As that ball is really leaned ON by Art Howe. When it left the plate, looked as though it might be out of here! In which case it would have been a win for the Astros. Instead Kingman went across the warning track, reached up, leaning against the wall at the three-ninety sign, he pulled it in to end the ballgame in favor of the New York Mets.”

Lindsey sounded pretty excited, though he didn’t mention that there was anything extra noteworthy about the ending, just that it worked out for the Mets. “Seaver gets the win,” Nelson reported, “he struck out six and he walked two in getting his seventh victory of the year. In the ninth inning, no runs, a hit and a walk, two left. We’ll be back in a moment with the final summary and totals. Right now, the final score of the game is the Mets three and the Astros one.”

This was June 12, 1977, just another fifth day in the life of the New York Mets. Life as we knew it, however, would not see another fifth day like it until April 5, 1983. But if you listened to Lindsey and willfully ignored everything else you had heard in the preceding weeks and months about a star player and a front office engaging in an intractable feud, you would have sworn it was just another typically terrific fifth day, courtesy of Tom Seaver.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On June 8, 1998, the antennae went up again, as 24,186 at Shea could swear they felt it coming. A no-hitter…no, make that a perfect game was in the air this Monday night. The signal had crackled in the atmosphere before, but this, surely, was coming in loud and clear. Rick Reed, a master of control, had the Tampa Bay Devil Rays under his spell. Think about it: the Devil Rays were an expansion team — not the most pathetic ever, necessarily, but certainly ripe for the taking by a pro’s pro who could paint the corners like a Da Vinci or (as the comparisons went) a Greg Maddux. Reed had the Devil Rays cornered on his canvas, all right, and could do no wrong. After retiring the Rays in order twice, Reed drove in the Mets’ second run of the game to put himself up 2-0, heading to the third. From there, he struck out two of his next three batters to give him five for the game thus far. Still no Tampa Bay baserunners. Reed stayed perfect through five innings. His flawlessness was contagious — his catcher, Mike Piazza picked up on it and belted his first Shea Stadium home run since coming to the Mets a few weeks earlier. And Piazza, in turn, continued to do an excellent job catching Reed. Through six, the soft-spoken West Virginian had collected eight K’s and allowed absolutely nothing to the visitors from Florida. Yes, the signals were clear. Tonight would be the night. A Quinton McCracken pop fly to Carlos Baerga…one out. A Miguel Cairo grounder to Rey Ordoñez…two out in the top of the seventh. Rick Reed was seven outs from immortality. But he was also facing a Hall of Famer in waiting, Devil Ray third baseman Wade Boggs. And Boggs doubled, which meant the Mets were still waiting for their first no-hitter. But Reed, a month from making it to his first All-Star Game, hung in to complete a three-hit, ten-strikeout, 3-0 gem. It wasn’t perfect, but what Met starter ever has been?

GAME 059: June 9, 1999 — METS 4 Blue Jays 3 (14)

(Mets All-Time Game 059 Record: 21-28; Mets 1999 Record: 31-28)

There was no disguising what a strange ride the 1999 Mets’ season had been to this point in their schedule. A promising start (17-9) gave way to a stretch of competitive doldrums (10-11) that was nonetheless punctuated by some dramatic moments (Robin Ventura’s two grand slams in one doubleheader; a five-run ninth inning that beat Curt Schilling). But then, without warning, the bottom fell out.

The Mets played three games at Shea versus the West-leading Arizona Diamondbacks. They were swept all three, two by one run, one by nine runs. The Mets then hosted the Cincinnati Reds for three…three losses, as it turned out. A six-game losing streak, considering all the offensive talent the Mets had gathered in an effort to overcome the near miss that haunted them from the conclusion of the 1998 season (when they dropped their final five contests to let slip their first playoff berth in ten years), was considered an ominous sign. Worse yet was the next point in their schedule, their shortest geographic road trip of the year.

It was off to Yankee Stadium, home of the crosstown rivals they never asked for, and the timing could not have been less propitious. The defending world champions were doing their usual cruising toward another A.L. East title and took the first two games of the Subway Series, 4-3 and 6-3. The Mets had now lost eight in a row, and that was that, just about, where the Mets hierarchy’s patience was concerned. Manager Bobby Valentine, considered on the hot seat, got to continue to sit where he sat, but three of his coaches were ordered to take a hike. Out went Bob Apodaca, Randy Niemann and Tom Robson. In came Dave Wallace, Al Jackson and Mickey Brantley. A press conference to announce the changes was held at Yankee Stadium, replete with an interlocking “NY” microphone emblem provided by the home team. It made Bobby V appear, an observer noted, as if the Mets’ skipper was starring in a hostage tape.

Were the new coaches necessarily better suited to their respective tasks at hand than their predecessors, or was this just general manager Steve Philips’s heavy-handed warning shot at Valentine that he’d better shape up lest he, too, be instructed to ship out? Whatever the answer, 55 games had passed since the season’s beginning, and the Mets were a limp 27-28. Nobody thought a continuation of that trend would result in more episodes of revolving coaches. More losing would mean a new manager. As Valentine’s seat heated up further, he put his cards on the table, publicly stating if the Mets couldn’t win 40 of their next 55 games, he deserved to be gone. And just to ratchet up the stakes for himself, those 55 games began with the ESPN Sunday Night Baseball Subway Series finale at the Stadium, with Roger Clemens on the mound for the Yankees.

And the Mets, written off to the edge of oblivion, won, with Al Leiter besting Clemens, 7-2. It was one game, but it was a start. Interleague play continued the next night at Shea, where the Blue Jays winged into town. The Mets won that game, and the next. It was three victories since the coach-axing/message-sending and the Mets were responding. But it was only three games. This momentum could stop anytime, and Toronto brought to Flushing the man capable of ruining any good party, David Wells.

Wells was one of the mainstays of the Yankees’ rotation as they romped to their 1998 title, but he was jettisoned like he was just another pitching coach when his former employers saw a chance to provide a soft landing spot for the antsy Clemens, suddenly unhappy despite pitching very well in Canada. The Bronx Bombers bid adieu to their dependable if flaky large lefty, sending him to Toronto with a massive chip on one or both of his sizable shoulders.

It wasn’t a homecoming for Wells, since Shea had never been his home, but he did have his supporters in the stands, including not a few women who resembled him in bearing and manner, save — perhaps — for his trademark mustache. His first two months in his second Toronto go-round hadn’t been terribly successful, but Wells was surely on this New York night. For eight innings, the Mets couldn’t touch him, garnering just five singles and no runs. The Jays appeared on their way to an easy 3-0 win as Wells prepared for the bottom of the ninth and, it was reported, a quick jaunt to one of his old Manhattan haunts, the China Club (Toronto was off the next day and had Philadelphia next on its itinerary).

Well, there was to be no party for David Wells on this Wednesday night. The Mets woke up against their nocturnal nemesis in the ninth, scoring a pair off Wells on a Robin Ventura two-out, two-run double (preceded by a Mike Piazza steal of second). Wells exited one strike from his complete game shutout and then saw his win dissipate altogether when Brian McRae doubled home Ventura versus rookie reliever Billy Koch, a Long Island native.

After eight relatively calm innings and an uplifting ninth, things would get hairy for the Mets as extras arrived. For one, they were undermanned, having lost hot-hitting rookie Benny Agbayani when Benny lined a batting practice pitch off the cage and onto his face. They were also without Bobby Bonilla, of whom Valentine wanted no part given the sulking reserve’s insubordination the night before when Bonilla refused to pinch-hit. The Mets, then, were down two players when their manager found himself also no longer eligible to play his role in the game.

Home plate umpire Randy Marsh made a catcher’s interference call against Mike Piazza in the top of the twelfth, awarding the Jays’ Craig Grebeck first base and sending baserunner Shannon Stewart to second with one out. Valentine argued the case with Marsh and found himself ejected. In situations like those, managers are supposed to completely disappear from view.

But Mets fans had long before learned Bobby Valentine wasn’t a manager who did was he was supposed to, so no wonder television viewers were treated to a glimpse of Bobby V in the bottom of the twelfth. Valentine, against all rules and regulations, poked his head into the Mets’ dugout. Oh, he was wearing a t-shirt and a non-Mets cap and hid his eyes under sunglasses and, oh yes, took a couple of strips of eyeblack and crafted himself a mustache that would soon become more famous than Wells’s. But there was no disguising that it was Bobby Valentine.

“I tried to loosen up the team for just a minute,” Valentine would say later.

Did it work? Or were the real catalysts behind the Mets’ eventual 14-inning 4-3 win Pat Mahomes’s three shutout innings of relief and Rey Ordoñez’s single to score Luis Lopez with the decisive tally? As with the coaching changes, one couldn’t definitively say. But the Mets could say they had won four straight after losing eight in a row, and 1999 had just gotten even more interesting.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On June 6, 2003, two remnants of the Mets’ suddenly distant if relatively recent glory days came face to face to settle the outcome of an unlikely Friday night matchup in Flushing. It was the Mets and the Mariners, two teams who had never before played a regular-season game, though they had very nearly crossed transcontinental paths a mere three years earlier. The Mets had won the National League pennant on October 16, 2000, and awaited their World Series opponent the next evening. It could very well have been the Seattle Mariners, already in New York. All the M’s had to do was win a pair of games in the Bronx, and they and the Mets would soon board flights bound for the Pacific Northwest to begin the 2000 World Series. But winning a pair of games in the Bronx was a tough task in those days, and down 3-2 in the American League Championship Series, the Mariners failed to win one. Hence, it wouldn’t be until 2003 that the Mets and Mariners would get a modestly meaningful look at each other, and most of the meaning for Mets fans was derived from the return to Shea Stadium of one of their favorite players from the club’s late ’90s surge to prominence, first baseman John Olerud. Olerud, allowed to leave by GM Steve Phillips as a free agent prior to 2000, was greeted warmly if not universally by the not quite 27,000 on hand for the novelty of seeing Seattle. Fate would have it that the former Met hero came up in the ninth as the potential go-ahead run versus someone else with a Met postseason pedigree, Armando Benitez. The closer from the 1999 and 2000 playoff teams had long ago lost the goodwill of the Shea faithful — along with his location — but now Mets fans with any kind of memory were forced to choose: root for Olerud, who in the collective Met mind represented the untarnished good times, or stick with Benitez and all his baggage. The only argument against pulling for Olerud to knock in Bret Boone from first base with two out was he wore a Seattle Mariners uniform, while Benitez, reviled as he was, was still the Met closer. When Armando delivered a 3-2 pitch and Olerud swung through it to end the game as a 3-2 Met victory, it was clear where a cheering Shea crowd’s priorities lay.

GAME 060: June 9, 2000 — Mets 12 YANKEES 2

(Mets All-Time Game 060 Record: 22-27; Mets 2000 Record: 34-26)

It had started innocently enough. The Mets were playing the Blue Jays at SkyDome in one of those Interleague matchups that came with the territory. Nobody clamored for Mets-Blue Jays, but in the early years of N.L. vs. A.L., it was decided parallel divisions should annually play one another. Thus, it was New York (N.L.) at Toronto on a Tuesday night, top of the first, two out, when the Mets’ designated hitter Mike Piazza — getting a night off from catching, thanks to Junior Circuit rules prevailing —faced Blue Jays starter Roger Clemens for the first time.

It was nothing special, certainly not for Piazza. He grounded out to short to end the inning. Mike was 0-for-1 against Roger, though before the night was out, he’d be 2-for-4. Not that it much mattered to Clemens, one would figure. The Rocket would strike out eleven batters and throw a six-hit complete game (complete games coming much cheaper in the DH league) to defeat Mike Piazza’s Mets, 6-3. Still, the great hitter had gotten a little bit of the best of the great pitcher. No other Met had collected more than one hit off Clemens.

The next time the two superstars met, the atmosphere was heightened. By then, in June of 1999, Clemens had engineered a trade out of Toronto (for whom he had won two Cy Young awards but where he ascertained there was no hope of legitimately contending for a postseason berth) and onto the defending world champion Yankees. The Subway Series had arrived at Yankee Stadium. Mets-Yankees was what Commissioner Bud Selig had in mind when he authorized Interleague play two years earlier. The intracity matchups had been so successful that this year the “natural rivals” would play two sets, home and home.

It was a big deal, per usual, and in the game within the third game of the first set, Piazza picked up where he left off against Clemens in Toronto: a double in the second inning instrumental in building a 4-0 Mets lead, then a two-run homer in the third inning to make the score Mets 6 Yankees 0, setting the stage for an early Clemens exit. The eventual 7-2 Mets win snapped Roger’s personal 20-decision winning streak that dated to his Blue Jays days. And, for what it was worth, Mike Piazza now possessed a career .667 batting average versus the Rocket.

The Subway Series passion play moved to Queens a month later. It was the Rocket’s second regular-season appearance at Shea, having pitched there once with the Jays, in 1997. His history in Flushing, however, extended back to October 1986, when young Roger Clemens started the sixth game of the World Series, a game his Red Sox lost in memorable fashion despite his own stellar pitching. It was ages ago by 1999, but Mets fans had long memories and they didn’t particularly care for what they remembered of Clemens from when Clemens was a Red Sock. They showed it in ’97 when he visited as a Blue Jay. Now that he was showing up at Shea as a Yankee. You could say his newest uniform wasn’t winning him any new admirers.

Despite a good won-lost record (he was, after all, pitching for an offensive juggernaut), Clemens had been struggling toward the midpoint of 1999. His ERA sat at 4.50 when he took on the Mets, and he wasn’t all that sharp in this go-round, giving up a run-scoring single to Rey Ordoñez in the second and a solo home run to John Olerud in the third. If it was of any solace to Clemens, he had held his nemesis Piazza at bay in two at-bats, grounding him out twice.

But Mike emerged from the bay in the sixth. With Edgardo Alfonzo on second and Olerud on first, Piazza laced into a 2-1 offering from Clemens and sent it soaring deep over the left-center field fence to give the Mets a 5-2 lead and the Rocket another unwanted early shower. The Mets would go on to defeat Clemens for a second time in 1999 and Mike would finish his season’s encounters versus Roger with a lifetime .556 batting average.

It was only three games’ worth spread out over two seasons, but it was becoming clear to anyone paying attention: Mike Piazza owned Roger Clemens.

Clemens no doubt was paying attention as the 2000 edition of the Subway Series pulled into Yankee Stadium on a Friday night in June. Its first stop was another Rocket vs. Mike matchup. The first encounter went Clemens’s way via a called strike three in the top of the first. The second, in the top of the third, was a different story.

Recently recalled rookie left fielder Jason Tyner, the Mets’ first selection in the 1998 amateur draft, reached first when Yankee catcher Jorge Posada made an errant throw to Tino Martinez. Clemens then walked Derek Bell on a 3-2 count. Posada allowed a passed ball to move up both baserunners before Edgardo Alfonzo took first on another 3-2 walk.

The bases were loaded and nobody was out when Piazza approached the plate. Mike took one ball and then took Roger Clemens clear over the Yankee Stadium wall for a grand slam home run. The Mets’ portion of the Bronx sellout crowd erupted. Clemens silently seethed. And the Mets led 4-0.

The next time Clemens saw Piazza, he was behind 5-1 in the top of the fifth. Piazza greeted him with a leadoff single and came around to score the Mets’ sixth run when Todd Zeile drove him in from second. Their next meeting was called off by Yankee manager Joe Torre after a Bell RBI double and an Alfonzo two-run homer shoved Clemens into a 9-2 hole in the sixth. Mike was due up next, but it would be Todd Erdos, not Roger Clemens who would pitch to him.

Piazza treated Erdos as if he were Clemens, though maybe not quite as harshly. He singled, though he didn’t score. Once the Mets build their lead to 12-2 (Erdos surrendering a three-run jack to Bell), Bobby Valentine removed Piazza, too, giving his catcher a breather. By then, the Mets were safely en route to a 12-2 victory — their widest margin in any Subway Series win — and Piazza had upped his lifetime batting average versus Clemens to .583. In a dozen at-bats, Piazza had raked seven hits, walloped three home runs and driven in nine Met baserunners.

Roger Clemens was one of his generation’s finest pitchers. Maybe one of the finest ever. But against Mike Piazza, he was just another Todd Erdos.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On June 17, 1985, it was time for the Mets to commence getting even with the team that cost them the previous season’s National League East title. They were playing the Chicago Cubs for the first time all season a season after the Cubs’ unexpected resurgence trumped their own 90-win feelgood story. Though the Mets held a 4½ -game lead over the Cubs as late as late July in 1984, the Chicagoans — a generally older bunch reinforced at the trade deadline by a slew of mercenary types — blew by them as August dawned; they outlasted the young Mets by 6½ games when all was said and done. But now it was a new year and it was an opportunity for the Mets to say and do something else altogether. By this point in the ’85 campaign, the Mets’ attention was focused more squarely on their newest competition for divisional supremacy, the St. Louis Cardinals, but the Cubs still loomed as formidable and were still in the thick of a four-way battle for first with the Mets, the Cards and the Montreal Expos. And that bitter 1984 ending still lingered in the Met consciousness. Come this edition of Monday Night Baseball (ABC aired the game for the whole nation to see), the Mets began to make amends. Gary Carter, acquired by the Mets for battles like these, homered off ’84 Cy Young winner Rick Sutcliffe to give the Mets a 1-0 lead in the fourth, and Danny Heep doubled in Wally Backman to extend the lead to 2-0 in the fifth. Sutcliffe didn’t give up anything else, but Ron Darling gave up nothing at all, defeating the Cubs 2-0 in a five-hit, seven-strikeout complete game. Advantage: Mets…with three more games to follow at Shea.

Thanks to old friend Mark Simon for providing audio from the game of June 12, 1977.

To support Roger Hess’s climb up Denali to raise funds for the Tug McGraw Foundation in honor of his friend David, who has fought so valiantly to beat his brain tumor, please visit here.

by Jason Fry on 10 June 2011 3:20 am Jason Bay is on the bench. David Wright and Johan Santana are on the shelf. Jose Reyes is being poked and prodded like a prize steer by 29 other covetous baseball teams. It’s an unsettling time to be a Mets fan. (Maybe you’ve heard.)

Yet quietly, some of the less-expensive and less-discussed Mets are making strides, refining their game in ways that make you think about 2012 and 2013 and imagine good things, instead of some threadbare version of the Marlins North or the Royals East fighting over canned goods in a tattered, dingy Citi Field.

Jonathon Niese, for instance, is more and more a pitcher you trust. Tonight he was awesome, dazzling the Brewers with variations on a deadly curveball. Would you like a swooping parabola, or a knee-buckling rainbow? Oh, why decide — how about both? Niese undressed Carlos Gomez rather cruelly in not one but two at-bats, leaving Go-Go staring helplessly at everything happening down there on the black and at his knees. But nothing was more fun than the Jonathan Lucroy at-bat to close the seventh. Niese was looking mortal, having began the inning giving up a hit in the hole to Ryan Braun and walking Prince Fielder. But he then got Casey McGehee to fly out and retired Yuniesky Betancourt and his ridiculous name thanks to a nifty play by Josh Thole, and then it was 2-2 on Lucroy, representing the tying run.

Niese threw him a curve, of course. It was absolutely unhittable, denting the outside corner at the knee, and led to one of my favorite sights in baseball. Once in a while, in that situation, the pitcher throws a perfect pitch when the hitter’s either helpless against it or looking for something else. The pitcher sees the batter locked in place, knows the ball will be a strike, and begins to exit the mound before the umpire even has his say. The catcher knows the same thing and catches the ball with his momentum headed dugoutward. Actually, this is pretty much the stuff of illusion — the pitcher maybe takes a half-step a split-second early and the catcher sensibly stays where he needs to be. But it doesn’t feel that way. It feels like the pitcher, catcher and their teammates all leave way before the pitch goes where it’s supposed to, leaving the poor batter standing on an empty field in lonely contemplation of just how out he is while the umpire almost apologetically signals the coup d’grace.

Niese wasn’t alone Thursday night — the Mets continued their gnat attacks on enemy teams, buzzing the Brewers for single after single and building a lead that shouldn’t have felt safe, given what happened the night before, but somehow did. And alongside Niese in the spotlight was another Met growing in leaps and bounds as we watch.

Ruben Tejada has been a silky-smooth fielder since he arrived, but last year he was pitiful with the bat. Seeing him clearly overmatched, none of us had any particular objection when the Mets were firm about sending him to Buffalo with the apparent intention of leaving him there. It was a fine plan, until everything that’s happened happened. Now, bizarrely, Tejada is pushing to the front of a second-base line that’s proved a lot longer than we figured back in March. He doesn’t have the pop of Justin Turner or Daniel Murphy, but he no longer looks overmatched, to put it mildly. He looks like he has an idea of the strike zone, a quick bat, and confidence that he isn’t just here for his glove. He looks like he belongs.

To support Roger Hess’s climb up Denali to raise funds for the Tug McGraw Foundation in honor of his friend David, who has fought so valiantly to beat his brain tumor, please visit here.

by Greg Prince on 9 June 2011 12:11 pm What are we as Mets fans but our collective sense of self? Or our sense of what we’re not? Consider the case of David, a man I encountered last summer for the first time through my friend Jeff at Citi Field when we, along with Jeff’s son Dylan, attended a Mets-Phillies game together.

David struck me as a really decent human being — plus he wore a Shea Stadium Final Season pin on his golf shirt. I liked him immediately. And he liked Citi Field enough to come back with his wife and two daughters a couple of weeks later to see the Mets play the Marlins. Describing a bottom-of-the-ninth rally that came up one hit shy, David wrote to Jeff, “I never felt so excited and hopeful, and in the next minute, ‘What happened?’ It got real quiet.”

This was in August. Come early September, Jeff sent me horrifying news: David was in Colorado, on vacation with his family, when he experienced a seizure. His wife took him to a hospital where he was told he had suffered an aneurysm and was diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor.

Stunning. Terrible. Blatantly unfair. David could not have appeared any healthier when we parted ways on the 7 Super Express in August. Now this. Just miserable, miserable news. Talk about real quiet.

But there was this slender blue and orange lining, as related by Jeff:

“When the Colorado doctor saw that he was from New York, he asked if he was a Yankees fan, and David, despite his condition and pain, objected and said that he was a Mets fan.”

Yeah, this is definitely a Mets fan we’re talking about. And he’s a Mets fan who, through resolve, treatment and some kind of faith, we’re still talking about very much in the present tense. That is to say I saw David at Citi Field in early May. He plans to drive his oldest daughter to college in August. He intends to run the New York City Marathon in November. He is, in the face of overwhelming odds, alive and — all things considered — relatively well.