The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 30 March 2010 3:24 pm It seems Kiko Calero and I shared a stadium twice last season, two games in late May when he pitched and I watched, yet I must confess I have zero recollection of him. It was too late in the action to be up and cruising for Daruma, hence all I can think is I was engrossed in conversation or so focused on the Met hitters he was facing (10 in 2 IP, none managing to score) that the presence of Kiko Calero simply escaped my notion.

I apologize to Kiko Calero. I apologize that he made zero impression on me even though he pitched for Florida against the Mets in six different games last season, and I watched all or part of every one of them. I apologize that he’s been in the majors since 2003, yet when the Mets signed him at the outset of Spring Training, my first thought was “who the hell is this?” I apologize for asking the same question in my head whenever his name crosses my mind, namely, “Isn’t Kiko Calero the tropical drink mix that sponsored those extraordinarily festive variety shows on Channel 47?” Finally, I apologize for thinking that all Kiko Calero has done this March is give up game-winning hits to marginal utility infielders…though to be fair, that’s exactly what he’s done the two times I’ve noticed him.

Kiko Calero, 35 years old, seven-season veteran, 67-game righthanded workhorse for the second-place Marlins, may make the Mets despite coming aboard late and wearing No. 94. When not surrendering home runs in the ninth to Ruben Gotay or Alberto Gonzalez in the tenth, he’s apparently been not bad. He is reportedly in the mix to make the Mets’ pen. Usually I hate that phrase, “in the mix,” but since I chronically confuse Kiko Calero with Coco López, it seems apropos.

Seasons have been known to turn on relief pitchers to whom I was paying scant attention in Spring Training, from Harry Parker in 1973 to Pedro Feliciano in 2006. Maybe Kiko Calero is that guy in 2010.

Or maybe not. A lot of relief pitchers parade in and out of our lives, some sooner than others (and some not nearly soon enough). This is why I get less caught up than the average fan in penciling in the roster that will start the season. I develop opinions in the course of a spring like anyone else, but my attitude is mostly get 25 guys into Met uniforms and we’ll take it from there. I don’t have that much confidence in Jerry Manuel’s observations on who belongs, but I have even less in mine and surely he has more of a vote on the matter than I do.

What saves us all is trial and error, even if some of that error takes place when games count. You don’t go from April to October with the same 25 guys. You don’t go from April to the end of April with the same 25 guys. Flux is the state of things in roster construction, now more than ever it seems.

Kiko Calero could be here to start the season. He could stay a while. He could stay a full year. Or he could be gone and not return before we know it. It wouldn’t be unprecedented. April may signify the fresh beginning for us as Mets beginnings, but in 39 episodes, it’s marked the end of a Met career. That is, 39 different players have made their final Met appearances in April, the month when everything is supposed to commence anew.

What a kick in their head.

This doesn’t count those who were cut in the waning days of Spring Training in those years when the grapefruit league extended into April (which is more years than not). It also doesn’t count the curious case of Pete Schourek who made the team out of St. Lucie in 1994, was carried north by perpetually besnarled manager Dallas Green, didn’t pitch in the opening series in Chicago and was then waived after three to make room for Doug Linton. Schourek would compile a 25-7 record with Cincinnati over the next two strike-shortened seasons. Linton seemed like a nice fellow, too.

Gotta be a bummer. You work all spring, you get the green light (or don’t get the red tag à la Major League), you’re a Met…and then, just like that, you’re not. You can play your last Mets game at any point, one supposes, but to do so in April must be what T.S. Eliot was talking about. Or was that the Elias Sports Bureau?

There are, in general, two kinds of April And Out Mets. There are the 16 who have been Mets before and their demise waited an entire winter to step right up and meet them; and there are the 23 for whom one April was it. Either way, there’s no denying the truism declared by the Buckinghams: to be exiled from the Mets in April is kind of a drag.

Unless it works out for you the way it did for Schourek. You could say the same for shortstop Tim Foli, who never got along particularly well with Met Aprils (or many other people, which helps explain the nickname Crazy Horse). In April 1972, Foli was part of the three-youngster package — Ken Singleton and Mike Jorgensen were the others — that brought Rusty Staub to New York. The season started late that year because of a players’ strike. Foli came back in 1978 but didn’t impress Joe Torre enough to ward off the onrushing Kelvin Chapman experiment in 1979. Chapman, who won a job in camp, was installed at second on Opening Day, moving superb defensive second baseman Doug Flynn to short, moving Foli to the bench.

If you can’t start for the impending 1979 Mets, maybe your days are inexorably numbered. Foli was traded to the Pirates for speedy Frank Taveras after a couple of weeks and clearly made the best of things. He solidified the Buc infield and was next seen holding down short for the world champions, Howard Cosell declaring Foli as “the glue” of the Fam-a-lee. Kelvin Chapman was next seen at Shea in 1984. Frank Taveras was seen in the interim waving at everything, including ground balls.

Crazy Horse is part of a subgenre of April And Out Mets: recidivist Mets who apparently overstayed their second welcome. Pitcher Ray Sadecki came home in 1977 only to leave home a little more than two weeks later. Pinch-hitter Marlon Anderson‘s first successful go-round as a Met was a fading memory in the first week of 2009, and he was let go in short order. Outfielder Brady Clark wandered through the non-Met desert for five seasons before his 2008 return; his fare thee well came April 22 two years ago. Reliever Pete Walker had two walk-ons as a Met, the second cameo coming to a close on April 20, 2002.

Pinch-runner Lou Thornton was a Lost Boy Found in 1989, but the Mets told him to get permanently lost on April 24, 1990, which was particularly hasty given that that season got off to a late start thanks to a Spring Training player lockout. Particularly horrible timing belonged to erstwhile starter Ed Lynch, who got to be a 1986 Met for exactly one April game after steadily hanging in there as the Mets eleveated from the depths of September 1980 to the precipice of glory. He was injured, then traded, then a Cub the night the Mets clinched against Chicago in September. He was not a happy ex-Met, telling Jeff Pearlman in The Bad Guys Won, “It was like living with a family the whole year and getting throw out of the house on Christmas Eve.” GM Frank Cashen went out of his way to favor Lynch with a World Series ring, which may be like getting your stocking stuffer around January 18, but at least it’s something.

The 1986 World Champion Met with the least claim on the title also said goodbye in April, albeit April 1992. Shortstop Kevin Elster was plagued by a bad right shoulder that wouldn’t get appreciably better without surgery. There went the last man to be added to the ’86 postseason roster. Another Met with ties to legendary times — quite different legendary times — who hit the road in April was catcher Choo Choo Coleman, Negro League veteran and one of the avatars of the absurdity of the ’62 Mets. Coleman kept catching even when Casey Stengel had seen enough, hanging around AAA long enough to bubble back up to the bigs in April ’66. After six games, he was sent down to Jacksonville where he caught a young pitcher named Tom Seaver. Choo Choo was still donning the tools of the Bubmeister for Tidewater while Tom Terrific was leading the Mets to the Promised Land in 1969.

Among other Mets for whom April wasn’t their only month but it was their last were:

• the relentlessly peripatetic pitcher Bruce Chen, ending his Met tenure in April ’02 (third team down, seven teams to go…and still counting);

• the reluctantly historic Ralph Terry, throwing his final pitch in April ’67, 6½ years after Bill Mazeroski took him deep, but 4½ years after Willie McCovey, much to Charlie Brown’s consternation, took him not quite high enough;

• Grant Roberts, out in April ’04 a while after it was revealed he had been plenty high, and not necessarily in the strike zone;

• mini-Manny Victor Diaz, whose truncated Mets outfield career was permanently condensed in April ’06;

• infielder Larry Burright, who got to play in the first two games ever at Shea but was sent out before the Mets’ first win there in April ’64;

• and outfielder Andy Tomberlin, whose Met tenure ended while on the season-opening West Coast road trip in April ’97, meaning he missed the Jackie Robinson retirement ceremony, but also never had to wear the unlamented ice cream caps that debuted that very same night.

One other April And Out Met, “been here before” division, deserves most special mention, as he is a cult figure among those who know about him. On the day Tom Seaver returned to the Mets, April 5, 1983, he faced a Phillies lineup that included Joe Morgan, Tony Perez, Mike Schmidt and his opposite number, Steve Carlton. That’s five Hall of Famers in one ballgame. But for a penchant to bet, we’re pretty sure Pete Rose would have made it six. Immortals were the order of that magical Shea Opener.

Tom’s supporting cast included one former MVP (George Foster), one defending home run champ (Dave Kingman), one fellow 1973 National League pennant winner (Ron Hodges), three world champions to be (Mookie Wilson, Wally Backman and — through no fault of his own — Doug Sisk) and, arguably, the most trivial Met who ever lived.

Q: Who was in the Opening Day lineup for the Mets in 1983, drove in the winning run and never played for the Mets again?

A: Mike Howard.

Yes, good old…that guy. Howard, starting right fielder a month and a day before Darryl Strawberry came up, went 1-for-3, stroking a run-scoring single in the home seventh in support of Doug Sisk (Tom having exited after six). Mike not only never played for the Mets again, he didn’t bat in that game again. He was sent out to Tidewater, replaced in the lineup by Danny Heep, on the roster by Mark Bradley and in the annals of Metsdom by no one. Nobody else owned a piece of Opening Day the way Mike Howard did and was less rewarded for it.

April was the end of Mike Howard as a Met, but it wasn’t the whole of him. He was called up on September 12, 1981, doubled in his first plate appearance and reached on catcher’s interference in his last. Fourteen games in 1981 and 33 in ’82 couldn’t keep Mike Howard from an April exit, but it gave him other Met months on which to look back and reflect.

The same could not be said for the 23 Mets for whom it was all about April. Their first games, last games and, in some cases, only games came as they were just shaking the rust off. Maybe if they’d been allowed to stay until May, they may have met a kinder fate.

Maybe not.

When you’re starting a brand new team, it’s a shakedown cruise all the first month. Casey Stengel shook down his 1962 Mets and had every reason to not like what he saw. Four Mets in the vicinity of Originality made way for new members of the cast almost at once. The first to come and go was catcher Joe Ginsberg: two games, five at-bats, no hits, but only an 0-4 record for his team when he forever departed. Perhaps Joe — carrying the designation First Met To Play A Last Game — took perverse pride in thinking, “Big deal, they went 40-116 without me.”

Three later Met catchers — Rick Sweet in 1982, Mike Bishop in 1983 and Gustavo Molina in 2008 (of whom it must always be said, “no relation”) — would follow Joe Ginsberg’s early example and find themselves out at the plate in the Aprils of their disconnect.

Meanwhile, two other Original Mets who couldn’t be held responsible for too much of the mess they left behind, ex-Bum Clem Labine and journeyman Herb Moford, also were done in the bigs once they were done pitching for the 1962 Mets. Outfielder Bobby Gene Smith, on the other hand, found his way to the Cubs and Cardinals before the season was out and played in the majors as late as 1965 with the California Angels, where his peers included Jimmy Piersall, who ran out his hundredth homer as a backward Met (Casey didn’t care for that, either), and three men who’d be Mets much later to no positive effect whatsoever: Dean Chance, Jose Cardenal and, most notoriously, Jim Fregosi.

Fregosi, eternally recalled in Met lore as what you get when you give up on talent, played on the same Met team in 1973 with Rich Chiles, who is what you get — or got — when you give up your soul. It wasn’t as resonant in 1969 abandonment as Nolan Ryan (+3) for Jim Fregosi, but Tommie Agee for Rich Chiles (and Buddy Harris) wins Bob Scheffing no blue and orange brownie points. Chiles, a lefty-swinging outfielder, went 3-for-25 in April ’73. Then he went to the minors, disappearing from major leagues for three full seasons. By comparison, Jim Fregosi’s .233 in 146 games over two seasons was stalwart…but only by comparison.

Rule 5 infielder Bart Shirley may not have lasted all of April 1967, but he kept interesting company. He debuted one day after Tom Seaver and three innings after Jerry Koosman. Shirley bowed as a pinch-hitter for Kooz; alas, like Fear in the movie they made about Piersall, Bart struck out. Also, unlike Kooz and Seaver, he had no staying power. Wes Westrum gave Bart only a half-dozen April looksees before Bing Devine cut his losses and returned Shirley to the Dodgers.

April was no less cruel to the Met aspirations of Mac Scarce, who arrived as partial payment for yet another 1969 Met, Tug McGraw, and probably never believed his name would describe his Met experience: one game on April 11, 1975, one batter faced in relief, two pitches (to eventual ray of Shea sunshine Richie Hebner), one walkoff hit, one adios. Mac, thus, became the first of the April sect of Moonlight Graham Mets, but not the last. On April 13, 1977, Luis Alvarado would give the Mets an 0-for-2 in a 7-3 loss to the Cardinals. The Mets would then give Alvarado an airline ticket to Detroit. Others for whom the April Band-Aid approach (just rip it off in one game’s time) was deemed appropriate were two emergency starters who created full-scale disasters:

• Brett Hinchliffe, 2 innings pitched, 9 hits, 8 earned runs — but only one walk — against the Brewers, April 26, 2001.

• Chan Ho Park, 4 innings pitched, 6 hits, 7 earned runs — and two walks — against the Marlins, April 30, 2007.

Milwaukee fans weren’t done tailgating before Hinchliffe’s Met and major league careers were over. Park, somehow, righted himself, contributed to the division-winning Dodgers and pennant-winning Phillies the last two seasons and has since joined the defending champion Yankees. Only some good deeds go unpunished.

High hopes were a hallmark of the career of Ken Henderson. In 1965, as a 19-year-old Giant outfielder, he was tabbed (we are reminded by James Hirsch’s monumental current work) “the next Willie Mays,” which is always the kind of tag with which you want to saddle a kid. Henderson never turned into Mays, but he turned out all right, serving as a solid outfielder in San Francisco and a few other teams. In 1978, as a 32-year-old newly minted Met, Henderson was off to a reasonably promising start: not Willie Mays, but certainly a decent complement to Willie Montañez, who came over in the same four-way trade the previous December. The promise was never fulfilled, however. In Henderson’s seventh game, April 12, he crashed into Shea’s right field fence, did a number on his left ankle and that was that for K-K-Kenny and the Mets. He’d go on the DL and then to Cincinnati for Dale Murray, a reliever who made a lot of opposing hitters look like the next Willie Mays.

The rest of the April And Outs can be divided essentially two ways: Guys who didn’t get much of a chance to show they didn’t belong; and Guys who didn’t get much of a chance but proved they didn’t belong. The kinder category includes a man who stands to break from this pack any day now, Gary Matthews, Jr. An April pinch-hitter and an April pinch-runner, he was an April pinch-packer in 2002, but he stands ready to rectify his record should he stick with the Mets and stay ’til May. The same can’t be said for the Met who replaced Matthews, McKay Christensen. McKay didn’t stay ’til May, but last we heard, he expressed no regrets.

Three relatively recent righthanded relievers — Calero precursors, perhaps — got the heave-ho mysteriously quickly. Brian Rose put in three relief appearances in April 2001 and was in no way worse than the comparatively enduring Donne Wall; Mike Matthews‘ four decent turns out of the bullpen in April 2005 were overshadowed by one that was dismal and another that was dreadful and, ultimately, Mike’s coffin-nailer; and Darren O’Day, who was given the ball four times in April 2009, was victimized by a numbers situation and was soon off to Texas where he pitched quite brilliantly the rest of the year.

Then again, we saw enough off the bat, literally, from righty retread Jonathan Hurst in April 1994 (7 games, 12.60 ERA); novelty knuckler Dennis Springer in April 2000 (2 starts, 8.74 ERA); and sagging southpaw Casey Fossum in April 2009 (whose 2.00 WHIP and 3 of 8 inherited runners scored can be traced directly to being the first Met to wear No. 47 since another Met portsider thoughtfully left it steaming on the mound at Shea at the conclusion of the 2007 season).

One other lefty began and ended his Met career in the same April, though I’m not sure how to characterize him. Make no mistake: nobody except Willie Randolph wanted Felix Heredia on the 2005 Mets. King Felix I was what we had to take from the Yankees so we could get rid of crusty Mike Stanton…sort of a scaled-down unwanted lefty-for-unwanted lefty version of Mel Rojas for Bobby Bonilla. Heredia had had his moments as a Marlin, particularly on the ’97 champs, but was Bomber non grata by 2004. This didn’t make him the least bit attractive as a Met proposition in the spring of ’05, but Randolph put him on the team to start the season. The Metsosphere, then encompassing far fewer blogs, collectively groaned. WFAN grew staticky with calls to GET RID OF HEREDIA! After three appearances, he was shut down with an aneurysm in his left shoulder. Nobody except maybe the feral felines at Shea missed Felix Heredia.

Funny thing, though, is I can’t for the life of me figure out what Felix Heredia did wrong as a Met. Oh, he had sucked for the Yankees, which wasn’t what you’d call a résumé-grabber for Mets fans. And he tested positive for steroids after rehabbing in St. Lucie — the fault of supplements, his agent said. But those were before and after situations. While a Met in April 2005, Felix Heredia faced 10 batters and retired 8 of them. He gave up a hit in one appearance, a walk in another and allowed no runs in any of his outings. He inherited no runners, so that didn’t become a problem either. As best as I can recall, we expected the worst out of Felix Heredia and were collectively relieved to see him DL’d before it could actually occur.

In other words, we got all worked up over nothing. As 39 April And Out Mets could have told you, it’s been known to happen.

Special thanks to FAFIF reader ToBeDetermined for bringing up the Opening Day heroics of Mike Howard a couple of weeks ago and unwittingly spurring the research that became this article.

Appreciation as well to Justin Sabich of the New York Times‘ Bats blog for soliciting the 2010 thoughts of Jason and me, along with Sam Page of Amazin’ Avenue and Matt Cerrone of MetsBlog. Part Two runs today; Part One was posted yesterday.

by Jason Fry on 29 March 2010 11:35 pm At the end of Absence of Malice, the great 1981 newspaper movie, the reporter played by Sally Field finds the tables have turned on her, and sits numbly while a colleague runs through everything that’s happened for the story she’s been told to write. Her account is a proper recitation of the facts, but one that says nothing about intentions or bad luck or missed chances, and you see this play out on Field’s face as she listens.

“That’s true, isn’t it?” the other reporter asks.

“No,” Field says, then pauses, trapped. “But it’s accurate.”

That scene went through my mind when I read about the denouement of the affair of the plaque outside Citi Field commemorating Game 7 of the 1986 World Series. The plaque is part of a series that’s been added to the Fan Walk, our greatest moments set amid the expressions of belief purchased by fans. It’s a nice juxtaposition — official recitations of great events echoed by a surrounding chorus of fan memories. And it’s welcome evidence that Year 2 of Citi Field may see the addition of a lot of what was missing in Year 1, starting with a healthy dollop of Mets’ history in their own home.

So what’s the problem? As originally worded, the Game 7 plaque told us that “first baseman Keith Hernandez and third baseman Ray Knight delivered key hits, and Sid Fernandez earned the win with exceptional relief work.”

Well … not quite.

Sid relieved Ron Darling with two outs in the fourth and the Red Sox up 3-0. Dave Henderson was on second and Wade Boggs was due up. Sid walked Boggs — the only baserunner he would allow — and got Marty Barrett to fly to right. He then shut down the Red Sox in the fifth and again in the sixth, after which Lee Mazzilli pinch-hit for him with one out in the bottom of the inning. Maz singled. So did Mookie Wilson. Tim Teufel walked. Keith Hernandez drove in Maz and Mookie to make it 3-2, and Gary Carter’s RBI groundout tied the game. Roger McDowell worked a scoreless seventh; Ray Knight led off the bottom of the seventh with a home run, and the Mets were on their way.

The win, of course, goes to McDowell. And that’s what the updated plaque will say.

Kudos to Ken Belson of the New York Times for an excellent rundown of the plaque on the Times’ Bats blog — and for giving our blog pal Shannon Shark of the Mets Police center billing for his work calling attention to the issue and driving the awareness that helped get it fixed posthaste. As Shannon told Belson, this is about “making sure we teach our children correctly.” Amen to that.

But if ever there was an understandable mistake, it’s this one. Those of us who watched the Mets claw their way back into Game 7 remember that it was El Sid who calmed the waters and allowed a better story to emerge. Boston had battered Darling around; Sid’s deceptive deliveries and sneaky speed disrupted the Red Sox’s’s’s’s’s timing and got them thinking about lost momentum and missed chances. McDowell followed his spotless seventh with a ghastly eighth, yielding two singles and a double to make the score Mets 6, Red Sox 5 and bring Jesse Orosco in to face a raging conflagration.

Wins can be silly things. Starting pitchers sometimes get them when they give up runs by the bushel but last five innings because their mates are scoring runs by the double bushel. And relievers sometimes get them not because they were particularly competent, but because they were in the right place at the right time.

It’s unassailably accurate that Roger McDowell was the winning pitcher in Game 7. (Heck, you could look it up.) But is it true? That’s a little murkier.

(Speaking of the Times, Greg and I discussed the 2010 Mets this morning on the Bats blog, along with MetsBlog‘s Matt Cerrone and Amazin’ Avenue‘s Sam Page. Check back in tomorrow for Part 2 of the discussion. Thanks to Justin Sablich for including us!)

Update: And here’s Part 2.

by Greg Prince on 26 March 2010 8:15 pm Welcome to Flashback Friday: Take Me Out to 34 Ballparks, a celebration, critique and countdown of every major league ballpark one baseball fan has been fortunate enough to visit in a lifetime of going to ballgames.

BALLPARK: Veterans Stadium

HOME TEAM: Philadelphia Phillies

VISITS: 3

FIRST VISITED: August 13, 1986

CHRONOLOGY: 4th of 34

RANKING: 31st of 34

There was nothing to like about Veterans Stadium. But repeated exposure to it made me like it just a little — just enough to recall it with a modicum of fondness.

Which makes no sense, considering that each of my three visits to the Vet was to see the Mets play, and the Mets lost each time. The Mets weren’t any good on those occasions and it wasn’t like the Vet was improving with age. Yet…damned if I know, by the time it was gone, I sort of felt bad about it.

Which makes no sense.

Speaking ill of departed ballparks seems rather insensitive (and you know what suckers for sensitivity Philadelphia fans are). Perhaps it’s because the Vet was the first park I visited that eventually disappeared from the landscape, I felt something for it in death that I’d barely detected in life. For years, it sat beneath the infinitely and objectively more pleasant Royals Stadium and Jack Murphy Stadium on my list. It was only when I had to face the fact that a place I got to know a bit better than most out-of-town venues was going away that it mysteriously floated up slightly in my affections.

Call it misplaced sentimentality. Call it the Dead Vet Bounce. Call it an appreciation of sincerity: The Vet sincerely didn’t care what you thought about it, and at the end of the day I kind of respected that.

Veterans Stadium was as unpretentious as a ballpark could get, which was appropriate because what could it possibly have pretenses toward? It was hard. It was plastic. It was numbingly round. You didn’t rush to embrace it and you wouldn’t dare hug it. If you tried, I suspect you’d come home with bruises on the inside of both arms, and maybe a jab between your shoulder blades. But it got the job done, no matter how unpretty the job. Your job, as the fan, was to watch the game. You watched the game at the Vet. There was nothing else to look at.

Also, it was there. Veterans Stadium appeared unmovable. I had come to count on it as the out-of-town ballpark that, if I wanted to be adventurous on a moment’s notice, I could be. A map showed me Philadelphia was very close to New York. When I was a kid, my idea of living it up would be to hop on Amtrak, buy one of 62,000 tickets and see the Mets in Philly. The whole thing couldn’t cost that much and I could be there and back in the same day. My exotic impulses have always been tempered by a limited desire to leave the house.

I followed through, at last, in the summer of 1986. It was almost spur of the moment — spur of the four days, at any rate. The weekend after my friend Fred’s first Mets game ever (as God was his witness, he had no idea one could just walk up to a baseball stadium and purchase a ticket), I upped the ante. Hey, I said, after a couple of beers at a barbecue, the Mets are in Philadelphia this week, we should just, like, GO.

And Fred was, to my gratification, YEAH! He’d had a few beers, too.

It wasn’t a big deal. Midafternoon on Wednesday, I picked him up and, save for a mysterious wrong turn that had us touring some unanticipated Pennsylvania precincts, we were at the Vet well before gametime. It wasn’t as easy as getting to Shea from the South Shore of Long Island, but it wasn’t that much more difficult, not when I was 23 and still had my driving legs. Fred and I always aspired to a ROAD TRIP! and this was pretty much it.

After we bought our tickets (along with a lot of other Mets fans), I insisted we walk the circumference of the Vet. A year earlier, on my first trip out of town for a ballgame, to Fenway, the walk around the park was fascinating. The walk around the Vet was less so. I think we gave up after discovering that no matter how much one walked, nobody ever saw anything different.

The theme followed inside. Circular is as circular does. Boy was that place round. And plastic. This was my first in-stadium exposure to artificial turf and it was not a shade of green found in nature. Not one found in ballparks prior to 1965, certainly. The Phanatic himself looked less synthetic.

This was the first time I ever sat in the outfield for a baseball game. The Mets helped the Phillies draw nearly 40,000. We were up there somewhere, PhillieVision breathing down our necks. No complaints, however, considering ten days earlier we were in the Upper Deck at Shea when Ray Knight singled home the winning run over the Expos. Not too many complaints over the Mets losing 8-4 given that the defeat trimmed our National League East lead over the Phillies to a trusty 20 games. If you were a Mets fan in the summer of 1986, your problems were few. It was very amusing to me that a home team fan sitting in front of us, oblivious to the scoreboard but probably mindful of the standings, kept declaring how much better the Flyers were than the Rangers since neither of those teams were participants in the sport taking place on that godawful carpet downstairs.

I was also endlessly amused by my own shtick of the moment, which consisted of popping out the bottom of a soda cup and blaring in what I thought was a hilarious voice, “MOOKIE WILSON, THIS IS YOUR CONSCIENCE SPEAKING — HIT A HOME RUN!” Fred laughed the first three or four times I did it. Then he told me to knock it off. Approximately half a lifetime later, I publicly apologize to Fred for overshtick.

Other nuggets that stay with me:

• Lee Mazzilli hit his first Mets 2.0 home run that night.

• The public address announcer sounded suspiciously like “Mr. Thompson,” secretary of the Continental Congress in 1776, which also took place in Philadelphia. This led to my other shtick of the evening, pretending that every batter he announced was one of the thirteen colonies: “NOW BATTING…DELI-WARE!” This didn’t grate on Fred as much for some reason.

• I bought a bootleg rubbery Phanatic in the parking lot after the game for Philadelphia expatriate friend then living in Florida. Five bucks.

• We stopped at a Roy Rogers on the Turnpike halfway to New York.

And then we drove the rest of the way home. Got in around 1:30 in the morning (technically the next day, but the convenience factor held) to find my parents up in the kitchen, eating cantaloupe and watching TV. How was it? they asked in earnest. I told them it was fun despite the loss. It’s also fun to remember that my parents were Mets fans in 1986. (Then again, who wasn’t?)

In the ensuing decade, I’d visit 13 more baseball stadiums, several of which redefined what fans could expect out of their ballpark experiences. The Vet was as much the norm as anything in the mid-’80s but was clearly was old hat by September 1996, yet I got the itch go again. I decided I wanted to make another trip to Philadelphia. The All-Star Game had been there in July and I’d inquired into FanFest tickets (unsuccessfully). Undaunted, I pitched an overnight trip to Stephanie, who had never been to Philadelphia, and she swung at it.

We chose the last Met-Vet series of the season, late September. This time the Mets’ lead over the Phillies was 5 games; sadly, it was the margin between fourth and fifth place in the N.L. East. Neither team was going anywhere but home, yet I still managed to secure lousy seats. Attendance — paid if not physical — was in the 27,000s, perhaps attributable to it being Phan Appreciation Day wherein everybody was handed a random premium that had gone unclaimed over the course of other 1996 promotional dates. We were the proud recipients of a pair of Phillies yearbooks.

The Vet may not have been completely empty that Sunday, but it wasn’t like the city was buzzing in anticipation of this Philly finale. The Inquirer was full of hype over the Eagles playing the Falcons on ESPN come evening. Yeah, I’m pretty sure we were the only ones who made a weekend out of the Mets and the Phillies.

Funny thing, though. With nothing on the line for either team, I sort of took to the Vet more than I had in ’86. Rain threatened — I’ve been very lucky never to have avoided a rainout on a ROAD TRIP! We took Philadelphia’s adorable version of a subway from our Center City hotel and, as was the case in ’86, got there very early. While the skies held out, we tried another walk around the premises. Found a few statues and trees and such this time. It wasn’t altogehter blah.

Up in whatever level I landed us, it was very quiet before the game. Eerily quiet. This wasn’t going to be an overly anticipant crowd. No ushers or anything like that up there either. Preparing for the imminent passing gullywasher, I grabbed about a hundred paper towels from the men’s room. Nobody in there either. It occurred to me one I could plant the Mets flag in this section of the Vet, claiming it for the descendants of Queen Isabella, and not a sole Philadelphian would raise an objection. Not a sole Philadelphian was in sight.

It cleared up eventually, and there would be Phillies fans on hand, as well as Mets fans. It was pretty mellow. Nobody who shows up on the last Sunday of the home season to watch a fourth-place team and a fifth-place team actively seeks trouble. By the time the Vet called it quits in 2003, it was best known for its internal criminal justice system — several holding cells and an actual courtroom for overly “enthusiastic” Iggles fans — but to be perfectly fair, I never had a problem with any threatening Phillies pholk there. I even found three things to like about it before we headed back to the SEPTA, our hotel and, ultimately, Amtrak:

1) Funnel cake. Advantage Philadelphia; beloved Shea had no such baked dessert option, unless you counted beer.

2) Blue seats and a fresh carpet, incrementally ratcheting down the hideousness factor

3) The revelation that this here is what my sister and people like her (not sports fans) must think a ballpark is. It had been four years since the opening of Camden Yards. Like a lot of baseball fans, it and the retro wave that followed it changed my perception of what a ballpark could be. But when the Vet was being squeezed from the same mold as Three Rivers in Pittsburgh and Riverfront in Cincinnati — two places I never checked out since I was assured they were basically Veterans Stadium — this was the standard. The standard had since been raised since the Vet opened in 1971. Thank heavens for Camden Yards, I thought. Too bad for Suzan (and her fellow non-fans) that they’d never appreciate the difference.

The cake, the blue and the conclusion all dulled the slight pain of a perfunctory 4-3 walkoff loss. Technically, we weren’t stung until later, for we had walked away in the eighth because we had to catch our Northeast Direct at 30th Street Station. One makes choices when one commutes to the old ballgame.

But we were back home the same night. All hail relative proximity!

My final trip to the Vet was not at my instigation. It was September 1999. My friend Richie’s birthday was approaching, his milestone 40th. He had never been to see the Mets anywhere but Shea. So how about it? he asked. I responded in the affirmative while he was still on “about”. He and his son picked me up early on Sunday, September 26, and, as with Fred and me thirteen years earlier, we were there in what felt like no time. The trip took easily less than two hours. Heck, we were so early, we drove around South Philly looking for brunch (settling adventurously on McDonald’s) and were still in the Vet parking lot before noon. It never occurred to me there was anything approximating a neighborhood there. In ’86, I was focused on not getting hopelessly lost. In ’96, all I noticed near the subway entrance was the Spectrum and the replacement for the Spectrum. My final trip to the Vet was not at my instigation. It was September 1999. My friend Richie’s birthday was approaching, his milestone 40th. He had never been to see the Mets anywhere but Shea. So how about it? he asked. I responded in the affirmative while he was still on “about”. He and his son picked me up early on Sunday, September 26, and, as with Fred and me thirteen years earlier, we were there in what felt like no time. The trip took easily less than two hours. Heck, we were so early, we drove around South Philly looking for brunch (settling adventurously on McDonald’s) and were still in the Vet parking lot before noon. It never occurred to me there was anything approximating a neighborhood there. In ’86, I was focused on not getting hopelessly lost. In ’96, all I noticed near the subway entrance was the Spectrum and the replacement for the Spectrum.

For luck, we parked under a lamp post with a sign that said 17. Gotta be lucky, I said: Keith! Alas, that was the only reminder of the 1986 Mets that day, except that it was yet another Mets @ Phillies loss for me. Unlike ’86 when we had all the cushion in the world, and unlike ’96 when the string was being played out, this one hurt a great deal. It was the sixth loss of a seven-game skid that saw the Mets tumble from fighting for the division title to just about blowing the Wild Card. Oh, it was not a happy birthday for Richie. I had to all but literally peel him off the floor of a Super Box, the Vet equivalent of a Diamond View Suite. Truth be told, it was about as luxurious in there as the Vet jail, and how we wound up inside it I’m still not 100% sure. Richie had bought us some nice Loge-ish tickets, but he had a friend, and she knew somebody and…let’s just say that no seat is a good seat when your team seems to be playing its way out of the playoffs.

If the Mets hadn’t come back one week later at Shea to forge a Wild Card tie on the timeless timeliness of Melvin Mora, I’d have nothing good to say about that last trip to the Vet (or Shea…or baseball). But with hindsight colored by the sweet victories of October 1999, that final September Sunday left me feeling simpatico with the Vet. It was kind enough to have a 17 in the lot. It must not have minded our presence too much.

Something about the ease with which we pulled in and pulled out of that parking lot, from and to Long Island in a veritable blink, and maybe the way we cheered for our team with impunity in a technically restricted area of the stadium (most of those on the “luxury” level were watching the Eagles battle the Bills on TV), gave me a sense of comfort at what was otherwise rightly considered an uncomfortable edifice. “Home away from home” would be too strong an endorsement — more like a change of pace rather than a totally alien environment. Less hostile than I understand its successor in Philadelphia has become, too, though that probably has something to do with the recent competitive composition of the National League East; the Mets may have lost all three of my games there, but the Phillies were never better than the Mets in any of those seasons. All told, if I didn’t exactly mourn the passing of the Vet, I didn’t curse it all the way to hell, either.

It was hulking and unapologetic. It was simple that way. It was Veterans Stadium.

by Greg Prince on 25 March 2010 10:57 am “I went to rehab. My friends embraced me when I got out. You relapse, it’s not like that. ‘Get away from me’ — that’s what it’s like.”

—Leo McGarry, “Bartlet for America,” The West Wing

Hello, my name is Greg, and I’m a Docoholic.

I’ve been hooked on Doc since 1984. It started when I was in college. I’d heard and read so much about Doc that I just had to see for myself what it was all about. My first time was in St. Petersburg.

Doc was everything they said it would be. It was exhilarating just to be around Doc. It was a rush. Everything just sped up. Things would rise. Things would break. It was a high like no other.

Before I knew it, I had to have Doc every fifth day.

I graduated from college in 1985 and went back to New York just so I could get as much Doc as I could. I wasn’t the only one, either. We were all addicted to Doc in those days. Every exposure to Doc made you want more. Doc was everywhere in ’85. Doc was all that mattered back then. I should have been out getting a job, starting a career, but all I wanted to do was sit in my room with my Doc paraphernalia and think about how amazing Doc was.

My Doc addiction — and yes, it was an addiction — was unstoppable, impenetrable. I would have taken Doc every fourth day if I could have. I didn’t think there could be any side effects. Doc was too awesome for that.

Thing is, you get hooked on Doc, you can’t believe anything can ever go wrong. It’s always gonna be a high, right? Always the rising, always the breaking, always these visions of letters, one after another, like you’ve really seen the light or something. Doc took you to places you never imagined really existed.

Then you find out they didn’t exist, not permanently. But you can’t help yourself from thinking it does. You think Doc is the answer to everything. I did, anyway. I kept up my Doc addiction in ’86. It didn’t feel quite the same, but I told myself that maybe it was just a bad batch. I took Doc as long as I could that year, a whole month longer than I did in ’85. But it wasn’t as good as ’85. Not bad, just not great.

Had to be a mistake, I figured. Doc’s good stuff, right? Doc won’t let me down. Next chance I had, I was ready for more. But then…oh man. I couldn’t get my hands on any Doc in ’87, not for a long while anyway. It was my first withdrawal and it was painful. That should have been a sign, y’know?

But I didn’t take it that way, and when the Doc supply became plentiful again, I was right there, ready to partake all over again like it was never missing.

You can’t fathom the lengths of self-deception you’ll go to when it comes to Doc. I mean all you want is that high again, that indescribable state of dizziness and euphoria. All the while, a little voice is telling you it’s not as potent as it once was, but you shut out the little voice. The little voice gets louder. Then your friends chime in: “Hey, maybe Doc’s not so great after all. Maybe it’s time we stop depending on Doc to get us high.”

So you break it off with your friends because how can they be your friends if they’re not into Doc the way you are? The addiction is so powerful that you refuse to acknowledge any evidence that Doc’s not as effective as it used to be. You can’t accept that Doc’s just not that great anymore.

How could Doc not be? Doc made you feel like the world was yours. Every fifth day nobody could lay a finger on you, man. You were the greatest because Doc was the greatest. How can you give up on that? How?

Time goes by and it’s getting clearer and clearer that not only is Doc not what you were sure it was, but that it’s actually kind of dangerous. It clouds your judgment. You’re so hooked, though, all you want to do is defend Doc, to keep Doc around, to take as much Doc as there is. “It’s still good,” you say to yourself. “It’s perfectly safe, too.”

The little voice telling you otherwise gets louder. All you want to do is drown it out. Doc was the best thing that ever happened to you. How could it not be all right?

Then one day you wake up and find out Doc’s not around anymore. They got rid of it as if it never existed…’94, I guess. Just like that, they cleaned it up. Everybody acted like it was a no-brainer, like you had to do this for the good of all concerned. It was so cold — left me positively shaking. I couldn’t stand the idea of being without Doc, even the diluted Doc, even the dangerous Doc. You’ve been on Doc for a decade. You thought you’d always have Doc to get you through those fifth days.

Cold turkey is tough. I tried, sort of. I’d still find myself watching my old Doc videos late at night, staring at my old Doc magazines. That was how I tried to put Doc in the past. I told myself it was working. I mean, what was the harm of looking at images of Doc, right? Then, suddenly, I hear Doc’s back. Yeah, they said, you can get some Doc for yourself — all you gotta do is go to a really bad part of town and they’ll fix you up good.

I did it. I’m ashamed of myself, but I did it. Real seedy characters, not the kind of place you’d be caught dead. Maybe I was dead, in my soul anyway. Maybe I was just a Doc junkie. All that Doc had done something to me. Still, there was a night in ’96, beautiful night, and I couldn’t believe how much I wanted Doc. I just let myself go. Fell in with a very bad crowd for that one night, but I swear I thought it was worth it.

That should have been a wakeup call. For a little while maybe it was. I tried not to think about Doc even though it was right over there on that other side of town. I got involved in other things and I stayed clean for a while, I really did. Sure, now and then I’d think about Doc, but fleetingly, like nostalgia for when I was young and gullible. It was harmless. I’d moved on.

Truth is you never move on from Doc, not when you’re an addict the way I am. The years went by and I never got the taste out of my mouth or out of my veins. If they’d just bring Doc back, just a little. I understood perfectly the Doc you were gonna get these days wasn’t the Doc I remembered, but I just wanted, I dunno…I wanted it to feel like it was. I wanted to see Doc, to hear Doc, y’know? I wanted to know Doc was with me, not just in my memory.

They didn’t bring Doc back, though. I always thought they would, but something always prevented it. What would have been the harm? At this point it would just be recreational, for fun. That’s all, just a little reminder of the good times. I didn’t have to have the full dose I used to have. Just a taste, I swear. Didn’t happen. Instead, I kept hearing about how bad Doc had gone, how nobody should want anything to do with it anymore.

Intellectually, I understood Doc was probably bad news. But I couldn’t get Doc out of my head. Bring Doc back, I said, and everything will be all right. Just bring Doc back. Please. I gotta have Doc.

Then it happened, it really did. They brought Doc back. Brought it back to that place where you used to be able to get it all the time. It was right before they closed it. I couldn’t believe they were doing it. This was 2008. Fourteen years I’d waited for a taste.

It was so, so good. I don’t know if it was flashbacks I was having, but I swear for a minute or two it was like 1985 all over again. Things were rising. Things were breaking. It was like I was up on my feet clapping and cheering and crying and losing my mind, as if nobody had ever found anything wrong with Doc in the first place.

Oh I wanted it so badly to keep going. They were building this new place next door to the old place and I heard rumors they were gonna have Doc there, like it had gone mainstream again. I knew it could never be like it was, but somehow just to have some permanent reminder of Doc…that was gonna be enough. That was gonna make me feel it again.

One day in January they did it. They said Doc was OK. Doc was a part of everything. It was my dream come true. Doc had been my reason for living 25 years ago and now they were gonna enshrine Doc. They were gonna have a day for Doc. Imagine that, a whole day devoted to Doc! All that talk about how bad Doc was for us couldn’t be true if they were doing that, right?

But the little voice returned. I tried to shut it out, but it kept whispering to me. It said, “When’s the day for Doc? They oughta have it as soon as possible because ya never know. There might not be any Doc by the time they say they’re gonna have it.”

That little voice, man…that little voice is scary for what it knows.

I guess you heard the same things I heard yesterday about Doc, that it looks like Doc is way more dangerous than they said, that Doc is potentially lethal, that Doc, given the circumstances, could kill you.

I’ve always thought that sort of thing was overblown, that you could handle Doc. I’ve always thought that no matter what they said, that I could handle Doc. Doc gave me the best moments of my life. I didn’t want to quit Doc. But now, it’s finally dawned on me there really isn’t any more Doc, not the way I idealized it.

***

UPDATE: The agent for Dwight Gooden tells the Record of North Jersey it was Ambien that caused the car accident in question. Docoholics everywhere who are powerless over their addiction to Doc hope it’s true…’cause that’s what Docoholics do.

by Greg Prince on 25 March 2010 8:42 am Once upon a time there was a runner named Rosie Ruiz who completed the 1979 New York City Marathon with the assistance of a subway ride, which will make the 26 miles and 385 yards just fly by. Nobody found that out, however, until after she was the first woman to cross the finish line at the 1980 Boston Marathon…a race she mastered by joining it while it was in progress. You wanted to know from shortcuts, Rosie was your gal.

Half marathon, full effort. On the other hand, Faith and Fear reader Sharon Chapman went the distance this past Sunday in the New York City Half Marathon, 13.1 miles through Manhattan, concluding near Battery Park, which is where she showed off her uniquely NYC medal and FAFIF wristband.

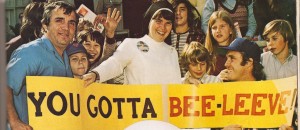

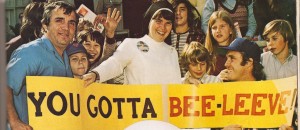

Sharon, as you can read here, is working her way toward the 2010 New York City Marathon while raising funds for the Tug McGraw Foundation’s ongoing battle against brain cancer every step of the way. We want to take this opportunity to both congratulate Sharon on running a heckuva race and thank all who came out to Two Boots Tavern for AMAZIN’ TUESDAY and contributed to this most worthy cause. Everybody’s efforts on the Foundation’s behalf add a whole new layer of meaning to You Gotta Believe.

***

Tug McGraw, converting Mets fans into Believers, 1973. You can learn more about the Foundation’s research and awareness efforts here and, if so moved and able, donate here.

Photograph of Sharon Chapman by the incomparable David G. Whitham.

by Jason Fry on 24 March 2010 7:00 am “People like to see human error when it’s honest. When people see you swing and miss, they start to root for you.”

— Paul Westerberg

I became a Mets fan in 1976, when the team had seemingly perfected an imperfect formula: combine superb pitching and defense with no offense and finish third. Miracle Met stalwarts Tom Seaver and Jerry Koosman were still around, as were Jerry Grote, Wayne Garrett, Buddy Harrelson and Ed Kranepool, who’d always been around and one assumed always would be. Joining them were representatives of the Little Miracle — guys like Jon Matlack and John Milner and Rusty Staub.

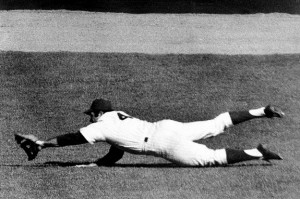

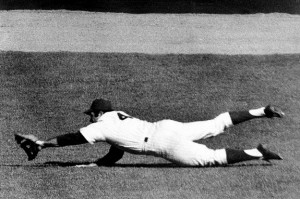

Staub was my favorite player, though of course I loved Seaver, rooted for Harrelson and appreciated Kranepool. But as a newly minted Mets fan with a dorky, proto-blogger’s bent, my hunger was for history. Desperate to know what I’d missed, I inhaled books about my team — if the Emma S. Clark Memorial Library had a quickie book about the ’69 or ’73 team (or any other year), I read it and then immediately wanted to read it again. With DVDs and Web video yet to arrive, I got most of my postseason lore from the written word and static pictures, from descriptions and reminiscences and snapshots and sportswriters’ flights of fancy. Tommie Agee in awkward mid-stride, a plume of white at the end of his arm. The unhurried way Gil Hodges strolled from the dugout to visit Lou DiMuro with a spotted baseball in one big hand. Tug McGraw dodging and diving and weaving and bulling his way to the dugout. Willie Mays on his knees in vain supplication. Jerry Koosman jackknifed in Jerry Grote’s arms, with Ed Charles in the early stages of liftoff nearby. And, of course, Ron Swoboda — fully outstretched and parallel to the right-field grass, approaching an uncertain intersection with the ground and a baseball.

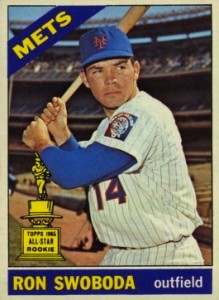

The Youth of America Swoboda was gone by 1976, but in every account of the ’69 Mets he loomed large. Not just because of The Catch, but because he was smart and funny and reflective and complicated. Which, though I didn’t know it yet, made him my prototype for what we wish every baseball player would be.

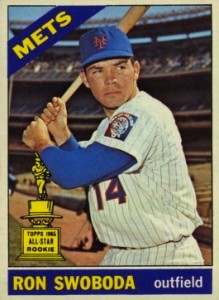

The lore was pretty thick around Swoboda even before 1969. He signed with the Mets for $35,000 in 1963 as a 19-year-old from the University of Maryland. (Ironically, given what came later, Swoboda was born and raised in Baltimore and had played high-school exhibitions in Memorial Stadium.) His last name is Ukrainian for “freedom.” In 1964, he caught Casey Stengel’s eye — the young slugger reminded Casey of Mickey Mantle — and was hyped as part of the Mets’ about-to-arrive Youth of America.

Casey pronounced his name Suh-boda, which stuck with fans. Teammates called him Rocky, a reference to his mental lapses in the field and his ability to say the wrong thing at the wrong time off of it. He came to the Mets to stay in 1965 — a callup he would come to regret — and became a fan favorite. Writers loved the fact that he had a Chinese grandfather, which was sort of true — his grandmother had married the owner of a Baltimore Chinese restaurant. Fans loved his ability to hit long home runs and sympathized with his outfield misadventures — you were never quite sure what Swoboda might do out there, but you were pretty sure it would be memorable. In his first big-league at-bat, a terrified Swoboda fell into an 0-2 hole against Don Drysdale, and considered it a triumph that he lined out to second. (“I felt like a fish that had been dragged into the boat and somehow managed to flop back out,” he’d remember.) Two days later, his second big-league at-bat produced a home run. RON SWOBODA IS STRONGER THAN DIRT, fans proclaimed at Banner Day.

In one game, Swoboda forgot his sunglasses, misplayed a Dal Maxvill fly ball into a triple, returned to the dugout in a fury and stomped on a batting helmet. The helmet got stuck on his cleats and left Swoboda hopping around trying to dislodge it while Stengel turned the color of a ripe tomato. Casey pulled Swoboda from the game, asking, “Do I go around breaking up his property?” Another time, Casey groused that Swoboda “thinks he’s being unlucky, but he’ll be unlucky his whole life if he don’t change” — a bit of baseball wisdom I’ve recycled for Come to Jesus moments with a few wayward journalists. Yet for all his misadventures, Swoboda hit 19 home runs in 1965 — a Met rookie record that stood until Darryl Strawberry eclipsed it 18 years later.

Immortality achieved Swoboda managed the difficult and dubious feat of hurting his development as a ballplayer by alternately thinking too much and not at all. (Years after he retired, he admitted he still had nightmares about facing one of the great hurlers of the ’60s and not being able to get set in the batter’s box.) He wasn’t always popular with teammates, who were annoyed by his on-field mistakes and his off-field gift of gab. When reporters entered the clubhouse after a Met win, it wasn’t uncommon to hear someone yell out “Tell them about it, Rocky!” It should come as no surprise that one of his best friends on the team was the irrepressible, quotable Tug McGraw. (The other was Kranepool.) But Swoboda was pretty quotable himself: In ’69, he was booed after striking out five times in one game, and opined that “if we lost, I’d be eating my heart out. But since we won, I’ll only eat one ventricle.”

1965 was a template for everything else — heroic moments mixed with ignoble ones. On Sept. 15, 1969, Steve Carlton struck out 19 Mets, with Swoboda accounting for two of the Ks as well as the two home runs that beat Carlton. He went 6 for 15 in the World Series. And, of course, there was The Catch. It wasn’t a particularly smart play — obviously he should have played it on a hop — except for the fact that hey, he actually caught it. “I had no time for conscious thought or judgment,” he’d recall. “The ball was out there too fast. I took off with the crack of the bat and dove. My body was stretched full out, and I felt as if I was disappearing into another world. … Somehow it happened. Somehow I got it. A miracle? Wasn’t the entire season a miracle?” In that one play the ignoble and the heroic did battle, the heroic came out on top, and because of that Ron Swoboda was a baseball immortal. As Tigers manager Mayo Smith put it, “Swoboda is what happens when a team wins a pennant.”

Two years after the Mets’ champagne celebration (“they’ve sprayed all the imported and now we have to drink the domestic,” he griped cheerfully), Swoboda was traded to Montreal after complaining a little too loudly about playing time. He hung around for a bit with the Yankees, failed to catch on with the Braves and was out of baseball by 29. He then began a long career as a broadcaster, one that’s taken him to New York and Milwaukee and Phoenix and New Orleans. It sounds like a more successful version of his playing career: He was thrown in before he was ready, learned on the job, and periodically forced to pull up stakes by events he couldn’t entirely control.

Swoboda was a sportscaster in New Orleans when I arrived there in 1989 as a pathetically green Times-Picayune intern, and a lot of people I came to know at the newspaper knew him. This finally registered with me when the woman I was dating mentioned in passing some bantering exchange she’d had with him. She had no idea then that I was a Mets fan, and must have wondered why I stared at her in amazement. She knows Ron Swoboda. Which means I could meet Ron Swoboda. But I never did. The idea terrified me — I was a kid, and incapable of thinking of him as another journalist. After all, I’d read about him and looked at pictures of him since I was seven years old. He was a Met, a World Series hero, the man who made the Catch. He was Ron Swoboda. Meet him? And then what? It would have been like chatting with Zeus.

One of the reasons I never became a traditional sportswriter was that I wanted to stay a fan, and I figured out early that entering a press box would kill my fandom. Which is also why I’ve never had much interest in meeting baseball players in real life. What’s the upside? Since I couldn’t possibly like the flesh-and-blood people more than I love their on-field personas, it’s almost certain that I’d like them a lot less. They can’t compete with who they’re allowed to be on TV and down there on the field, as seen through fandom’s lens. I’ve shaken hands with Fred Stanley and Ron Darling, exchanged a couple of dopey words with Rusty Staub, done a double-take on Canal Street after passing John Franco, and had Wally Backman step on my foot. That’s enough for me.

Well, mostly. Now that I’m older, I do wish I could sit down over beers with Ron Swoboda. I don’t know if I’d like him or if he’d like me. But I do know I’d find him interesting. After all, I always have.

Swoboda with Faith and Fear reader Jeff Hysen I don’t assume baseball players are dumb — I’m amazed at how many of them can analyze pitch sequences and find little tells during the game, and how they remember at-bats in vivid detail years later. Beyond their superhuman physical talents, many of them have an extraordinary ability to focus that most of us don’t know enough to understand we lack.

When we grouse that ballplayers don’t seem smart, most of the time what we’re really lamenting is that they don’t seem big on self-reflection. There’s an entertaining W.P. Kinsella story called “How I Got My Nickname” in which the ’51 Giants are all hyperliterate gents given to pondering the cosmos — a story that works because it’s immediately and obviously a fantasy. Back in ’92, the writer Kelly Candaele (Casey’s sister) penned a great piece in the Times in which, among other things, she wondered about the fact that her brother and his teammates didn’t lie awake thinking about their purpose in life. Astros shortstop Rafael Ramirez’s answer for her? “When I wake up in the middle of the night, it’s because I want a sandwich.”

There are exceptions. Players like Seaver or Darling or Keith Hernandez can dissect baseball like generals or prize-winning academics, and I’m invariably riveted. The 2000 Mets had three such players in Al Leiter, Mike Piazza and Todd Zeile — all smart, complicated guys who weren’t afraid of being interesting. But those players are exceptions that prove the disappointing rule. The first Met I knew of who was exceptional like that was Swoboda.

It’s clear that Swoboda spent some middle of the nights lying awake, and not because he wanted a sandwich. He isn’t just a good quote, but bracingly honest about himself. (You’ll find great interviews with him — the sources of many of this post’s quotes — in Stanley Cohen’s A Magic Summer and Maury Allen’s After the Miracle.) He’s talked wistfully about he never got along with Seaver, admitting that he was the one who sabotaged any chance at friendship. “I wanted to be the best in the game at my position; I wasn’t,” he said. “He just made it look so easy, was so good — and it just frustrated me so much.” And he’s told the story of confronting Gil Hodges in the clubhouse bathroom over his use of Kranepool — after which, feeling Hodges’ glower on his back, “I was standing against the urinal and I couldn’t pee.”

Of course, Swoboda will always be bound up with 1969 and the Miracle Mets — a bit of typecasting he has taken to cheerfully. (At last year’s 40th anniversary celebration, he pantomimed his famous catch, now immortalized above the right-field gate.) That’s no surprise, but Swoboda’s reflections on ’69 have almost invariably been interesting, too. “We were ingenues,” he recalled once. “We had that wonderful, clear-minded innocence of not having the responsibility of winning it, of not having to doubt ourselves if we stumbled, and that’s a marvelous state to achieve.” Another time, he said that 1969 “wasn’t destiny. I don’t believe in destiny. What I believe is you can get to a state where you are not interfering with the possibilities.” That’s a long way from taking them one game at a time, pulling together as a team and all the other rote nonsense players have been taught to say so that reporters go away as quickly as possible.

And Swoboda has always understood what that summer meant to the fans, and refused to see what he did and what we did as disconnected. He has always been willing to bridge that gap, and make us feel like it doesn’t have to exist, even though we know better. “I never felt above anyone who bought a ticket — I just had a different role than they did,” he has said. “We were part of the same phenomenon.”

When I saw the ’69 team at Citi last summer I cheered for all of them, of course. I applauded the McAndrews and Gaspars and Dyers. I cheered for the departed Tug and Gil and Donn and Don and Cal and Tommie and Rube. I gave Seaver and Koosman and Ryan their due, as one must. But the player I cheered longest and loudest for from that team?

It was Ron Swoboda. It always has been.

by Greg Prince on 23 March 2010 11:48 am The Mets, it was established when they were established, represented the New Breed. Their fans were descended from a tradition of Giants and Dodgers, but they — we — were something else altogether. We were not the past. We were the present and, by implication, the future. We were the stuff of 1962 when 1962 was as cutting edge as it could get. Everything about our existence shouted PROGRESS! as much as it roared LET’S GO METS!

That’s why I find it incongruous when a direct link can be forged to something old, musty and unmissed. If the Mets were all about the new, how old could they be?

In the case of five Mets, pretty old. And very unmissed.

Four players who wore the Mets uniform in the early years of the franchise as well as one extraordinary player who wore it when the team was approaching adolescence had previously worn uniforms that were no longer in style when the Mets came to be. They were the uniforms of the Indianapolis Clowns, the Kansas City Monarchs, the Atlanta Black Crackers and the Birmingham Black Barons.

Five Mets played in the Negro Leagues.

Maybe in 1962, while civil rights legislation still awaited its mighty push, this didn’t seem so anachronistic. It had been only sixteen years since Jackie Robinson broke the minor league color line with the Montreal Royals, fifteen years since he took it a step further with the Brooklyn Dodgers. The Cleveland Indians, St. Louis Browns and New York Giants were all integrated by the end of the 1940s, though by integrated, we mean no more than a few African-American players joining the white players. Even the most “progressive” organizations weren’t flinging open the doors to everyone regardless of race. Quotas kept the number of black players to a handful throughout the Fifties, and no team dared field as many as five black players at the same time, lest fans do the math and figure a majority of their team at a given moment wasn’t white.

And those were the progressive organizations. Several took their not-so-sweet time signing any black players at all. The Boston Braves and Chicago White Sox became the fifth and sixth franchises to include a black player in 1950 and ’51, respectively. More than six years had to pass between Robinson’s April 15, 1947 debut with Brooklyn before the Philadelphia A’s and the Chicago Cubs got on board in 1953. It was barely a month before Brown v. Board of Education was handed down on May 17, 1954 that the Pittsburgh Pirates, the St. Louis Cardinals and the Cincinnati Reds deigned to field a team that wasn’t wholly white.

The highest court in the land struck down “separate but equal,” yet five major league baseball teams clung to separate beyond Brown. No black Washington Senator played until September 1954; no black New York Yankee played until 1955; no black Philadelphia Phillie played until 1957; no black Detroit Tiger played until 1958; and no black Boston Red Sock played until July 21, 1959. That was a dozen years after Jackie Robinson became a Dodger, nearly three years after Jackie Robinson retired.

Who was the first black Met? Beautifully, that’s never been an issue. By 1962, there was no color line to break. The expansion teams were integrated from their beginning, the Mets included. The first three batters the Mets sent to the plate on April 11, 1962 were, for the record, Richie Ashburn, Felix Mantilla and Charlie Neal — a white man from Nebraska, a Latin man from Puerto Rico and a black man from Texas.

They were all Mets is all that mattered.

But let’s not kid ourselves. Brown v. Board of Education didn’t erase discrimination in this country any more than Jackie Robinson erased all vestiges of racism in baseball. Likewise, the matter-of-fact integration of the New York Mets, the Houston Colt .45s, the Los Angeles Angels and the second edition of the Washington Senators (the first one having vamoosed to Minnesota partly for reasons of race, by owner Calvin Griffith’s ineloquent reckoning), didn’t signify that everything was equal for everybody everywhere. The 1962 Mets trained in St. Petersburg, a southern city by dint of more than geography. The big Spring Training hotel in town then was the Soreno. It was where the Cardinals stayed and where the Yankees had stayed before they moved to Fort Lauderdale. The Mets planned on making it their base, too, but as a Newsday article from 1987 noted, “the Soreno Hotel wouldn’t take their black players, so the entire team stayed at an unrestricted hotel inconveniently located on St. Petersburg Beach.”

The team’s new place, the Colonial Inn, wasn’t an unalloyed bastion of equality. As recounted by Janet Paskin in Tales From the 1962 New York Mets, Al Jackson was “greeted by the vestiges of segregated Florida” upon arriving at the Colonial, namely a “request” from the hotel manager that Jackson, while certainly welcome to sleep in his room, stay out of the restaurant, the bar and the pool.

“I thought, ‘I’ll be damned,'” Jackson told Steve Jacobson in Carrying Jackie’s Torch. Mets traveling secretary Lou Niss “raised hell,” but to only partial avail. Mets players — black or white — who stayed at the Colonial would eat in their own private dining room and, by club edict, avoid the hotel bar altogether. It wasn’t a perfect arrangement by any means, but it was the Mets’ clumsy way of saying everybody here is a Met, not a black Met, not a white Met. Just a Met.

“I guess if the blacks couldn’t go in the restaurant,” Jackson recalled to Paskin, “the white guys couldn’t go in either.”

We were a long way from Utopia in 1962; we’re a long way from it now, too, but can you imagine having players on the Mets whose baseball backgrounds included a stint in a league that was identified by race? A league that no matter how great the level of competition may have been — and it’s generally considered to have been major league — existed because custom and law dictated it?

Yet it was so in 1962 and 1963 and 1964 and 1966 and as late as 1972 and 1973. Five Mets began their professional baseball careers as Negro Leaguers.

• The third batter and first second baseman in Mets history, Charlie Neal? He was one of those ex-Dodgers the early Mets had a predilection for collecting, but before he signed with Brooklyn and starred for the ’59 world champs in L.A., he had been an Atlanta Black Cracker.

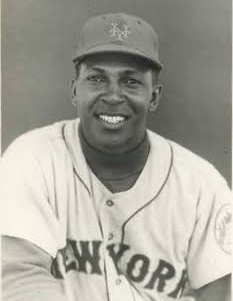

• The taciturn catcher whom we know mostly from Ralph Kiner’s timeless anecdote — “her name’s Mrs. Coleman and she likes me, Bub” — Choo Choo Coleman? Prior to his legendary answer regarding his wife’s name and “what’s she like?” he had been an Indianapolis Clown. (Update: In January 2012, Coleman told Nick Diunte of examiner.com that the Clowns with whom he played in 1956 and 1957 was a touring club not affiliated with any specific league.)

• The One-Year Wonder who started in right field in the very first game at Shea Stadium, George Altman? Before flanking Jim Hickman on April 17, 1964, he had been a Kansas City Monarch.

• The Say Hey Kid who electrified Shea upon his return in 1972 and drove it to tears by saying “Goodbye to America” in 1973? Willie Mays? Willie, perhaps the greatest player to ever wear any uniform, became a big league ballplayer for the first time as much with the Birmingham Black Barons as with the New York Giants.

Mays, as recounted in James Hirsch’s wonderful biography, was definitely a product of the Negro League, technically the Negro American League, the one that continued to operate for more than a decade after Jackie Robinson began to render segregated baseball obsolete. Hirsch describes Mays as a “new archetype,” blending speed and power as it had not been combined by previous superstars.

His base-stealing skills had developed out of necessity. There, most squads had fewer than twenty members, so versatility was required, and pinch runners were an unaffordable luxury.

[…]

Stolen bases were the easiest way to quantify Mays’s running skills, but he also accumulated extra bases through speed, cunning and force of will. In this area, more than any other, he imported the Negro League philosophy of daring, exuberance and pugnacity.

Willie Mays was the last Met to have Negro League experience in his background and the penultimate major leaguer to have played in such a circuit (the last was Hank Aaron, who retired in 1976). There was no more Negro League baseball after 1960, so any of its veterans who made the Mets were necessarily young when they played in those generally overlooked uniforms. There were still onerous quotas to stretch and stubborn barriers that had to crumble as they were coming up, but men like Neal, Coleman, Altman and Mays had more opportunity than the generation that preceded them.

Sammy Drake was briefly a Kansas City Monarch. A fifth player who shared the Negro League pedigree with those four Mets was Sammy Drake, an ostensibly unremarkable member of the remarkably bad 1962 Mets. Drake was an expansion draft choice of the Mets in October 1961, but didn’t make the club until the following August. He played in 25 games and registered 10 hits. The last of them led off the top of the eighth at Wrigley Field in the final game of the season. With Drake on first, Richie Ashburn singled. Then Joe Pignatano, later to earn a World Series ring as bullpen coach of the remarkably good 1969 Mets, hit into a fly ball 4-3-6 triple play. It was the last swing of Pignatano’s career. The last time Ashburn would be on the bases, too. Same for Drake. Their major league careers all ended that day, September 30, 1962.

I knew about Pignatano making his last big league at-bat overly memorable. I knew about Ashburn retiring after that 120th loss. I didn’t know about Drake, though. Until I looked it up, I had no idea he was one of the three outs. I didn’t know that he kept plugging away in the minors through 1965. Frankly, I knew next to nothing about Sammy Drake until last month when word of his death filtered onto the Internet a few weeks after he passed away at the age of 75. It was only then that I learned Drake, like Altman — and Satchel Paige, Ernie Banks and Jackie Robinson himself — was briefly, on a “tryout” basis in 1953, a Kansas City Monarch…a Monarch who would become a Met.

In an earlier time, he would have stayed a Monarch or maybe moved on to the Baltimore Elite Giants or Homestead Grays — or continued with the Carman Cardinals of Canada’s Mandak League, where he played in 1954. That would have been as far as Sammy Drake could have gone as a baseball player. But by the end of the ’54 season, with Brown v. Board of Education sinking into the American way of life with all deliberate speed, Drake signed with the Cubs. They sent him to the Single-A Macon Peaches of the South Atlantic League, or the Sally, in 1955. There had been Macon Peaches playing baseball in Georgia since early in the 20th century. It wasn’t until 1955, however, that there were black Macon Peaches. The first of them were Ernest Johnson and Sammy Drake.

It was eight years after Robinson. It was eleven months after Brown. It was a future Met making history in Macon seven years before he’d become one of ours.

There were no parades for this pioneer. As Drake told the Macon Telegraph in 2009, he and Johnson were limited to dining in a “little hole-in-the-wall restaurant there they had for us.” Macon and the Sally League of 1955 weren’t close to even the limited options permitted by St. Petersburg circa 1962. If you were Drake and Johnson, you stayed on the bus when your teammates got off to eat. They brought you your food and you ate it there.

“That was very degrading,” Drake told Coley Harvey of the Telegraph. “It hurt, man. It really did.”

That was just an element of a painful year in Macon, according to Drake’s recollections.

“It was the fans and the city itself where I had the problem,” Drake said. “It was the same way they treated Jackie Robinson. They threw black cats on the field, called me all out of my name and everything else. They called me the ‘N’-word, OK. They called me burr head. Or ‘black this, black that.’ And these are my home fans. I’m not talking about when I would be traveling to Savannah and all these other Southern cities.”

Sammy Drake moved on from Macon. He made the majors in 1960, with the Cubs, playing alongside Banks as well as his brother Solly (the Drakes were the first African-American brothers to play on the same major league team). Sammy got into 28 games with Chicago over two years before being drafted by the Mets. His last professional baseball experience was as a Buffalo Bison, amid an eclectic roster that included Choo Choo Coleman, first black Boston Red Sock Pumpsie Green, first Dominican major league shortstop Amado Samuel and champion Mets to be Cleon Jones and Bud Harrelson. In retirement, Sammy Drake taught Sunday school at the Greater Ebenezer Missionary Baptist Church in Los Angeles, a congregation led by Pastor Solly Drake.

As a .192 hitter on team that lost 120 games, we could probably get away with calling Sammy Drake an unremarkable Met. But it would be inappropriate to say anybody who persevered as he — or Willie Mays or Charlie Neal or George Altman or Choo Choo Coleman — did to make the majors when talent alone wasn’t nearly enough of an entrance fee was anything but a rather remarkable human being.

Image courtesy of New York Baseball History Examiner. Thanks to Crane Pool Forum for helping to gather the names of the ballplayers in question.

Please join us tonight at the first AMAZIN’ TUESDAY of 2010, 7 PM, at Two Boots Tavern on the Lower East Side, as we read aloud, rally around and try to raise a few bucks for the Tug McGraw Foundation. Details here.