The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 31 May 2022 2:24 am For whoever molds the story of the 2022 New York Mets into a controversial albeit highly entertaining limited series for HBO, here are a few data points to keep in mind when deciding where to be dramatic and where to be accurate.

• Left fielder Nick Plummer was not making his major league debut when he hit his first career home run, and he didn’t hit his first two home runs in the same game. Plummer dipped a toe into the Met outfield in April before returning from the minors in late May to start the two consecutive games over which he hit those first two home runs, one against the Phillies to tie a game that was about to get away, one against the Nationals that was relatively incidental to a blowout victory in progress (though definitely very nice to see). Producers will probably wish to frame Plummer as a rookie who never set foot inside a big league ballpark before and perhaps combine his two big games into one. Yet it didn’t happen exactly that way.

• Right fielder Starling Marte, despite reminding at least one longtime fan of having an impact on the 2022 Mets similar to right fielder Rusty Staub’s on the 1972 Mets, wasn’t visited in the clubhouse by Rusty Staub before continuing on the hot streak that, among other things, helped destroy the Washington Nationals, 13-5, on May 30. It would make for a better story if Staub and Starling forged a bond that transcended a half-century, but, sadly, Rusty passed away in 2018 while Marte was a member of the Pittsburgh Pirates.

• Owner Steve Cohen didn’t burst through the doors of a raucous Delta Sky360° Club and announce at game’s end, “This franchise just posted the first 13-5 win it’s ever had — it’s a Unicorn Score, everybody, and the drinks are on me!” because, as everybody knows, the Mets had previously won by a score of 13-5 on August 3, 2003, meaning this second 13-5 win merely represented a Uniclone Score.

• Shortstop Francisco Lindor may have been on a mission to win fans over after a rocky start at Citi Field, but Lindor played an entire season for the Mets prior to 2022. The series based on real events will be tempted to portray Lindor as a free agent with a chip on his shoulder, but he seems to have settled in in real life after a rough 2021 that feels less and less relevant with every passing day given how he’s thriving at the plate (eight consecutive games with a run or more driven in — not eighty consecutive games, which, admittedly, would be more dramatic).

• Second baseman Luis Guillorme, who spent the last portion of May on an incredible tear, did not march into Billy Eppler’s office one day in mid-May with an ultimatum to play him or trade him, then come thisclose to being sent to Cincinnati before Eppler was handed a note that informed him Brandon Nimmo would be out for the rest of the season and only then he realized the perennially underestimated Guillorme was his sole option as a leadoff hitter. Guillorme had been playing very well and then stepped up some more to fill in at the top of the order while Nimmo was listed as day-to-day. Also, Guillorme’s defense needs to be in the script, and we don’t believe Eppler ever fired a trophy through his office window (we’re not sure Eppler’s ever won a trophy).

• First baseman Pete Alonso’s thirteenth homer of the season did not have him on a pace suggesting he would break any of Barry Bonds’ home run records, though he did pass Ed Kranepool on the Mets’ all-time home run list. Additionally, the ghost of Hack Wilson was not at Citi Field on May 30; was not situated adjacent to the Mets’ dugout; and did not interrupt any of Steve Gelbs’s puckish hockey playoff updates by drunkenly raging at Alonso, “I dare you to break my single-season RBI record, you…you…you ‘POLO’ BEAR — I double-dare you!” At least the SNY broadcast did not pick up any evidence that any of this happened.

• Lefthanded pitcher Johan Santana didn’t come out of retirement on the eve of the tenth anniversary of his no-hitter to start for the Mets “to make things right with HI57ORY”. While Santana will be the Mets’ guest Tuesday night as they commemorate his no-hitter of June 1, 2012, another lefty, David Peterson started for the Mets on Monday night and pitched into the fifth, falling one-third of an inning shy of qualifying for the win. After the game, it’s possible Peterson wandered out onto Mets Plaza and sought advice from Tom Seaver’s statue, but no contemporary accounts of such an encounter currently exist.

• Atlanta Brave manager Brian Snitker, watching from Phoenix, where the Braves fell 9½ games behind the Mets, didn’t see Buck Showalter conduct his postgame press briefing; didn’t see Buck stare directly into the camera; and didn’t see Buck address him specifically with remarks like, “Get it straight, Snit: you’re not getting anywhere near first place as long as I’m riding herd on my Queens stallions” or anything else implying hallucinations were running rampant between fierce rivals. Besides, the Braves’ loss to the Diamondbacks on May 30 finished later than the Mets’ win versus the Nationals, so chances are Snitker wasn’t watching television at the moment Showalter met the media.

• The Mets did not clinch a playoff spot on Memorial Day in 2022. While we accept that certain events will be condensed to move the action along, 112 games remained after the Mets won their fourth game in a row and raised their record to a nonetheless impressive 33-17. Teams don’t clinch postseason berths in May.

Though that seems like a buzzkill detail at this point.

by Greg Prince on 30 May 2022 6:23 am “Kid, we’re short of staff this weekend. I need you to go out to Citi Field and cover Sunday night’s Mets-Phillies game. The main thing is the lede. Watch what happens, and when you think you know what the main story is, type up a graf and shoot it back to the copy desk. We have multiple editions coming out, one after another, so make sure you label each one clearly so we know at what point in the game you’re filing. Ya got that? Good — and good luck.”

***

BOTTOM OF THE 1ST

FLUSHING — Helped along by shaky Phillies defense, the Mets notched three runs to take a commanding early advantage as they attempted to complete a three-game sweep of their National League East rivals. While old friend Zack Wheeler struggled with his pitch count, his former teammates discovered ways to confound the talented righty, abetted by Philadelphia gloves that seemed intent on sabotaging the visitors’ cause. Following Luis Guillorme’s leadoff double and Starling Marte’s single that advanced Guillorme to third, Francisco Lindor grounded to first baseman Rhys Hoskins, whose hesitation cost Wheeler both a run and an out, as Guillorme crossed the plate after Hoskins’ throw to second pulled shortstop Jean Segura off the bag and Segura’s throw flew wide of home. Productive groundouts from Eduardo Escobar and Mark Canha eventually brought home Marte and Canha, digging a 3-0 hole for Wheeler, who had to expend 32 pitches to escape the first.

TOP OF THE 3RD

FLUSHING — Chris Bassitt’s holiday weekend cruise through the Phillies’ order took a detour in the third inning, sent off course when rookie left fielder Nick Plummer, making his first major league start, allowed a sinking liner to tick off his glove, gifting leadoff batter Odubel Herrera a double and setting the stage for a troublesome frame that saw Bassitt, the Mets’ de facto ace these injury-inflected days, throw 34 pitches, yet surrender only one run. The Phillie tally came home on an Alec Bohm double play grounder with the bases loaded after both Johan Camargo and Kyle Schwarber worked full-count walks. Despite being forced to work extra hard, Bassitt emerged from the lengthy inning with a 3-1 lead.

BOTTOM OF THE 5TH

FLUSHING — A one-out Starling Marte triple went to waste, as did a golden opportunity for New York to increase its 3-1 lead over Philadelphia. The triple, gained on a combination of baserunning guile and defensive mishap, occurred as Marte stroked a Zack Wheeler delivery into the right field corner. The hit appeared ticketed to land Marte on second until the Met right fielder correctly judged the trouble his Phillie counterpart, Nick Castellanos, was having trouble picking it up and getting it back into the infield. Marte slid into third with the Mets’ thirteenth triple of the season, the most by any team in the majors. Nevertheless, Marte wound up stranded on third as Zack Wheeler sandwiched an intentional walk to Pete Alonso with strikeouts of Francisco Lindor and Eduardo Escobar. While Marte’s triple could be interpreted as indicative of the aggressive approach that has vaulted the Mets into first place in the National League East by a wide margin, their failure to capitalize on the three-bagger may be a sign of a more troubling trend, as the triple was their first hit since the first inning and they let Wheeler keep them off the board for four succeeding innings.

TOP OF THE 7TH

FLUSHING — After Chris Bassitt threw six effective innings, Buck Showalter turned his club’s 3-1 lead over to young righty Drew Smith, but Smith may have gotten in the way of the Mets manager’s best laid plans. By attempting to field a two-out grounder from J.T. Realmuto with his pitching hand, Smith seemed to have injured his right pinky finger and had to leave the game, forcing Showalter to shuffle his bullpen plans sooner than he expected. While x-rays revealed a dislocation rather than a break, Smith’s removal loomed as a bad break for the Mets, even though his successor, Joely Rodriguez, stranded Realmuto on first base.

TOP OF THE 8TH

FLUSHING — The tenuous advantage the Mets held over the Phillies for seven-and-a-half innings came crashing down as Nick Castellanos belted a three-run homer to left field, catapulting Philadelphia over New York for a 4-3 lead. The right fielder’s bat swung in synchronicity with the game’s momentum, which had been teetering away from the Mets for quite a while, given their inability after the first inning to manufacture any offense against Zack Wheeler (6 IP), Brad Hand and Jeurys Familia, each an alumnus of the Met pitching staff. The crushing blow came off Adam Ottavino, pitching for the second night in a row. Ottavino came on in relief of lefty Joely Rodriguez, who had entered for an injured Drew Smith. Rodriguez had recorded two eighth-inning outs, but also walked Johan Camargo and Alec Bohm, leaving a troublesome tableau for his righthanded successor. The Mets, down one heading to the home half of the eighth, were already plagued by inertia from the bottom of their lineup as the game unfolded, with neither eighth-place hitter Nick Plummer nor nine-hole batter Patrick Mazeika reaching base all evening. What had been a very formidable Met attack appeared weakened by the precautiounary rest manager Buck Showalter gave his banged-up duo of Brandon Nimmo and Jeff McNeil.

TOP OF THE 9TH

FLUSHING — If nothing else, perhaps Buck Showalter found a new component for his bullpen’s “circle of trust,” with unsung reliever Stephen Nogosek coming on to pitch a scoreless top of the ninth for the Mets, retiring the Phillies in order and keeping the Mets clinging to hope they could overcome a one-run deficit as they prepared to come to bat for their last licks. Nogosek, wearing No. 85, has ridden the options express between New York and Syracuse this season, but with Trevor May on the IL, Drew Smith leaving this game early due to a dislocated right pinky, Adam Ottavino surrendering the pivotal home run to Nick Castellanos and old reliable Seth Lugo and new face Colin Holderman each deemed unavailable after they pitched Saturday night, Nogosek’s emergence as another legitimate righty option may rate as a factor to watch and, potentially, the sliver lining to a cloudy loss in the making. Longtime Met penwatchers can’t help but note the significance of a clean ninth inning after such a disastrous eighth.

BOTTOM OF THE 9TH

FLUSHING — Despite Joe Girardi having aligned his Phillie defense into its victory formation, inserting Roman Quinn in center and moving starting center fielder Odubel Herrera to right to replace slugger and provisional star of the game Nick Castellanos, the Mets found their way into the proverbial end zone, leaning on heretofore unknown Nick Plummer to go deep. Plummer connected for his first major league hit and home run off Phillie closer Corey Knebel, as the leadoff blast, soaring decisively inside the right field foul pole and landing on the soft drink-sponsored porch, dramatically tied the back-and-forth Sunday night affair at four apiece. The proverbial whole new ballgame headed for extra innings once Knebel escaped further damage. In the tenth, each manager anticipated starting his team’s respective at-bats with a runner on second. But while Buck Showalter could look forward to the speedy Starling Marte being his free runner, Girardi moved toward extras knowing that the fourth Phillie up in that inning, originally scheduled to be the dangerous Castellanos, would instead be the light-hitting Quinn.

TOP OF THE 10TH

FLUSHING — Eduardo Escobar, to date a disappointment with the bat, turned in one of the defensive gems of the year, racing to third base railing to grab a foul ball popped toward the visitors’ dugout by notorious Met-killer Kyle Schwarber. When he reached over the rail and into the Phillies’ lair to make his catch, Escobar ensured Schwarber would continue his weekend of frustration and futility against his usual punching bags. The Phillie left fielder, who hit nine home runs against the Mets last season, wore an 0-for-14 collar following his foulout. Escobar’s play also meant good news for Met closer Edwin Diaz, on to protect the 4-4 tie the Mets brought into the tenth. With the pop fly serving as the inning’s first out, Diaz proceeded to ground out Alec Bohm and intentionally walk Bryce Harper rather than let the reigning MVP hit with automatic runner Bryson Stott (running for Johan Camargo) on second. Buck Showalter’s decision to have Diaz face the next batter, Roman Quinn, who had come into the game for defensive purposes, replacing eighth-inning home run hero Nick Castellanos, paid off, as Diaz struck out Quinn, whose average dropped to .167, to end the half-inning.

BOTTOM OF THE 10th

FLUSHIING — A fairy tale season brimming with Met heroics added another unlikely chapter Sunday night, as third baseman Eduardo Escobar drove in the winning run in the bottom of the tenth to defeat the Phillies, 5-4. The Mets appeared on the verge of beaten after Nick Castellanos drove an Adam Ottavino pitch over the left field wall in the eighth, erasing a lead the Mets had held since the first, but after solid relief work from Stephen Nogosek and the first home run in the major league career of Nick Plummer in the ninth, extra innings told the tale of the two rivals, with Edwin Diaz pitching the top of a scoreless tenth, with help from Escobar’s stunning catch at the Phillies’ dugout railing of a popup off the bat of a slumping Kyle Schwarber. Working with the reprieve the Mets had earned for themselves following Castellanos’s blow, Escobar batted with free runner Starling Marte on second and the intentionally passed Pete Alonso on first and one out. While Escobar hadn’t been hitting much, he is an established major leaguer who knows when he is being taken lightly by an opposing manager. Joe Girardi’s decision to have his beleaguered closer Corey Knebel, who had given up the game-tying homer to Plummer, face Escobar rather than Alonso backfired when Escobar lashed a ball into right field that easily plated the swift Marte from second. With the win, the Mets swept their three-game set versus the Phillies, sending an opponent projected as a strong National League East contender spiraling. Philadelphia currently languishes 10½ games out of first place, while the pacesetting Mets, fifteen games above .500 for the first time since their pennant-winning romp of 2015, maintain an 8½-game lead over second-place Atlanta. It’s the largest advantage a Mets club has ever enjoyed in May.

***

“Good work, kid. We’ll use that last lede for the home edition.”

by Greg Prince on 29 May 2022 10:43 am “It’s gonna be a good summer.”

—Jimmy Burke to Henry Hill as they divvied up the loot from the Air France heist

The Mets do not score in every inning. It only feels as if they do. Or maybe it’s just that it feels as if they score every inning when it would be most helpful.

In the bottom of the fourth Saturday night, directly after Taijuan Walker’s gutting out of the Phillies paused for a two-run blip, the Mets’ offense answered. They’re very good at offering rebuttals lately. Francisco Lindor reached base by a walk. Often he hits his way on, but as he was leading off, this was fine. Pete Alonso singled. Often he leaves the park, but advancing Lindor from first to third in the process of taking first himself was dandy. Runners at the corners, and it was about to rain a little.

Two cloudbursts at once formed over Citi Field: a passing shower that didn’t require a tarp and Jeff McNeil blasting a ball off Zach Eflin until it landed above the right field corner and on Carbonation Ridge. The Mets had trailed, 2-1. The Mets now led, 4-2. You couldn’t count on the score flipping so soon; you kind of felt it was bound to happen eventually.

A lifetime of Mets-watching girds you against expecting the best, but this past week or two of watching the Mets tells you to relax, they got this. On Saturday night, they got this every way they needed to. Walker gave them five innings without his best stuff, giving up nothing more than those two runs in the fourth. Lindor did more than walk. With two hits (one of them a triple), he drove in three runs. McNeil we know about. McNeil we knew about before he batted. Among him, Pete and Francisco, you could sense Eflin’s one-run lead wasn’t going to stand up for long. Throw in the probability of lightning striking at any moment off the bats of Starling Marte and Luis Guillorme (your new leadoff hitter, at least for Saturday, as Brandon Nimmo rested his wrist), the grinding platework of Mark Canha and the signs that Eduardo Escobar may be about to follow the weather into heated-up territory, and virtually no inning passes without suggesting the strong possibility of a run or more.

On Saturday night, the Mets scored in four innings, totaling eight runs. After Walker left, the bullpen — Colin Holderman for two, Adam Ottavino and Seth Lugo for one apiece — kept the Phillies off the board altogether. Travis Jankowski may be on the IL, but Nick Plummer materialized to take on his pinch-running duties. The defense generally doesn’t miss a beat and the Mets rarely take a beating. The Mets absorbed one on Wednesday in San Francisco. They’ve recovered to administer in kind. They were taking one on Tuesday night. They overcame it like crazy (if not quite enough). They’ve been hitting the hell out of the ball since right about the minute Max Scherzer left the mound for the next “six to eight weeks”. In the last ten games, they’ve opened 72 cans of runs on opponents. Without either ace up their sleeve, they’re 7-3 in that period, elevating their National League East lead to 8½ games after winning, 8-2, on Saturday night. Also, Jacob deGrom reports, “I feel completely normal,” which means I feel completely giddy, even though I know it will pass. But maybe not for a while.

I’d close amidst this Memorial Day weekend by adding, “Have a good summer,” but it appears the Mets will take care of that for us.

by Greg Prince on 28 May 2022 9:46 am The Phillies put up a six-spot in the sixth inning, which would have been a problem had the Mets not treated the fabric of Friday night’s game with a solution that prevented such spots from staining their outcome: a 7-0 lead.

We’ve seen this season, usually from the encouraging side of things, the way tides can turn in a game. The Mets are occasionally down; the Mets are never out. Who invited the Phillies to try their hand at a momentous comeback? The six-spot in the sixth inning was a little unnerving — a pitcher rolling on his thumb, a ball thrown away, scads of soft contact, finally the wrong reliever giving up a long bomb — but it wasn’t fatal. The Phillies threw all they had at the Mets and still trailed.

Then the Mets threw a little back. They built their 7-0 lead on grinding at-bats, daring baserunners and Pete Alonso power, and protected it on Carlos Carrasco’s professionalism. It was only when Carrasco couldn’t corral one of the infield tricklers and flung it away (bothering his thumb in the process, supposedly only a little) that the Phillies sensed and exploited an opening. The Mets managed to close that crack some in the bottom of the sixth, thanks to another trademark Mets rally. Tomás Nido walks on three-and-two, Brandon Nimmo doubles, Starling Marte directs a ground ball where it needs to go. Breathing gets a little easier. Drew Smith, Joely Rodriguez, Seth Lugo and Edwin Diaz — the same quartet that sealed a no-hitter against these same Phillies four weeks earlier — nursed the two-run advantage to its happy ending. Seven-nothing was nothing but fun. Seven-six was nothing to sneeze at. Eight-six was two pumps of nasal spray to clear your sinuses and let you sleep easily.

Back to Pete for a moment. In the first, he brought home a run the Mets were determined to score. It was only a fly ball to medium right field, but it was enough for Nimmo to take advantage of Nick Castellanos’s uncertain (to put it kindly) arm. The action would be repeated one batter later, with Eduardo Escobar producing the not so deep fly and Starling Marte flying in from third. Those first two runs were joined by another DIY production, Francisco Lindor having walked, stolen and tagged up to get to third and crossed the plate after Mark Canha worked, worked, worked Bailey Falter for ten pitches until he singled to center.

Alonso was an element of the first inning. He was the star of the third, launching a cannon shot to left with Lindor on base to make the game 5-0, and the exclamation point of the fourth, when he sent a ball to the wall in right. It was good for a double to drive home Francisco again. Factor in five (five!) assists at first base to go with five putouts, and the night was too Polar to be overcome by a mere six-spot.

The home run in the third elevated Pete into a twelfth-place tie on the all-time Mets home run chart, which would be Bear-ly worth noting except for whom he tied. Alonso’s 118th career homer paired him, until 119 leaves the park, with Ed Kranepool. Those 118 Eddie whacked were the franchise record from Krane’s involuntary retirement in 1979 until Dave Kingman blew by them in 1982. Ed needed 18 seasons and season fragments to mount 118 trophies on his wall. As Mets fans, we understood it wasn’t a daunting franchise leadership total, but it was ours, thus it looked impressive. It still looks impressive when viewed through Krane-colored glasses, specs we of a certain age inevitably don when we examine Mets history. Eddie remained the only Met around from 1962 forward throughout the 1970s. Eddie established the home run record when hit his 94th in 1976 and kept building it, however slowly. Eddie was the Met standard for accumulated power.

And now Pete Alonso, who’s in his fourth season, has tied Ed Kranepool’s former franchise-best home run mark. It won’t be too many plate appearances before Pete unties Eddie and, health willing, tramples over Edgardo Alfonzo (120) and Kevin McReynolds (122) to enter the Top Ten. Todd Hundley (124) and Lucas Duda (125) will be just up the road from there, and if slumps stay to a minimum, MLB MIA Michael Conforto’s Met sum (132) looms within conceivable reach in the second half. A pretty good Pete Alonso slugging season — nothing fancy, noting standard-shattering — will place him seventh among all Mets in home runs hit as a Met, all before his fifth season begins.

That, too, is pretty good.

by Greg Prince on 27 May 2022 2:50 pm With apologies to Moonlight Graham awaiting a lifetime for his first at-bat in Field of Dreams; Blue Moon Odom, mainstay of the dynastic 1970s Oakland A’s; Wally Moon’s “Moon shots” down the right field line when the Flatbush-abandoning Dodgers put down temporary stakes at the woefully misshapen L.A. Coliseum; and even Pete Alonso’s shall we say acting in his current commercial endorsement of CarShield (“it’s an absolute moonblast to the third deck”), when we think of the Moon in the context of baseball, we think of the 1969 Mets, who proved correct the cynical conventional wisdom that man would walk on the Moon before New York’s reliably laughable National League franchise ever won a pennant. The Mets planted their championship flag at Shea Stadium fewer than three months after Neil Armstrong took the stars and stripes to a new frontier, but technically, man did get to the Moon first. If you bet NASA and took the over, you cashed in.

But c’mon. The wonder of Apollo 11’s journey and its temporal proximity to the ’69 Mets conquering disbelief on this here rock was and remains too good a storyline to pass up. You can’t tell the tale of the Miracle Mets without inevitably pausing on July 20 to note the Mets were in Montreal, outlasting the Expos in ten and then enduring mechanical trouble with the aircraft intended to fly them home. Our astronauts could get where they were going, but our suddenly second-place Mets were stuck on the ground, waiting out their delay by witnessing Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin set foot on the lunar surface via airport bar TV.

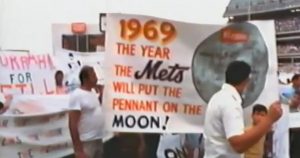

“I wondered what was more unusual,” that Sunday afternoon’s hero Bobby Pfeil told Wayne Coffey in 2019’s They Said It Couldn’t Be Done, “Man walking on the Moon or winning a game with a pinch-hit bunt single.” Ron Swoboda had similar thoughts as he looked back for Art Shamsky’s After The Miracle: “Everything was possible in ’69. The ‘man on the Moon’ was a part of that season we could never forget.” Although “We Cherish the Ground the Mets Walk On” was the winning entrant among 3,611 bedsheets and placards on Banner Day come the Sunday of Woodstock weekend August 17 — it encompassed actual grass (maybe not the kind abundant at Yasgur’s farm) — the one that lives on as indication of where fans’ heads were between July and October at Shea is one that pops up on the official 1969 highlight film. It reads…

1969

THE YEAR

THE METS

WILL PUT THE

PENNANT ON THE

MOON!

And so they did, Met-aphorically speaking, capturing the NL pennant on October 6 and earning the world championship banner ten days later. The Moon, as Robert Morse as Bert Cooper sang to Jon Hamm as Don Draper on July 21, 1969, may belong to everyone, but the Mets things in life are free to be associated with us.

2023 is the year Lunar Codex will put the Mets on the Moon. This is why when I very recently noticed a news story on television involving a glimpse of the Mets wordmark and something about artwork going to the Moon, and it had nothing directly to do with the summer of ’69, I had to investigate further. In a sense, it was only tangentially related to the reality-altering events of fifty-three years ago, and then only if you wanted it to be. In another, how could I not see or hear something involving the Mets and the Moon and not discern the intragalactic connection?

Which is to say I wanted it to be.

My conduit to the Mets meeting the Moon anew was someone at least a little touched by the twinned entities at the center of our 1969 consciousness. Like me, Nanette Fluhr was a youngster in the age of Armstrong and Apollo. Her dad woke her up at their New Jersey home to watch Neil take his one small step/giant leap. And like me, Nanette grew up with an affinity for the Mets, though maybe not exactly like me. The Tom Seaver trade kind of turned her off from baseball for a while, she confesses, but she did cotton to the club as a kid, coming as she did from strong National League roots (Grandpa loved Dem Bums in Brooklyn) and raising a son who certainly adored the likes of Reyes and Wright. “And,” Nanette wanted me to know, “we all loved Mike Piazza.”

Now we’re getting somewhere. Now we’re getting to what I saw on News 12 Long Island one lazy Saturday morning. It was a roundup show called On a Positive Note, sharing an array of good-vibes notes from around the Metropolitan Area. The segment in question focused on Nanette and the fact that a representative sampling of her portraiture — she’s a most accomplished painter — would soon be headed for the Moon on a mission that is admittedly of a lower profile than Apollo’s, but still something literally out of this world.

Step right up, then, and meet the Lunar Codex, an ambitious, artistic project curated by distinguished futurist Samuel Peralta in which three time capsules will be launched moonward. All the details are here, but the upshot of these moonshots is digitized versions representing some of the beauty we as a people are capable of creating back on Earth are being transferred to a flash drive in anticipation of launching and landing in the next couple of years. Included within this mission will be highlights from Nanette’s portfolio.

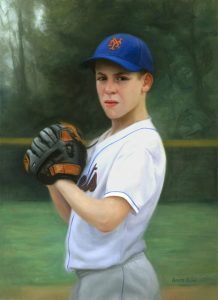

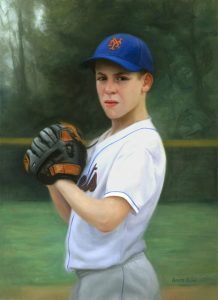

That News 12 piece showed a montage of her splendid work, without specifying exactly which paintings were chosen for the Moon. This made me curious because one of the paintings shown was of a pre-adolescent boy wearing a Mets cap and a Mets jersey, staring in from the mound for his catcher’s signal with an expression that could best be described as determination. As you may know if you’re a regular here, I’m on constant vigil for instances of the Mets infiltrating the popular culture. Every December, I endeavor to capture what I’ve seen in the preceding twelve months in an annual feature we call the Oscar’s Caps, named for the Mets cap Oscar Madison wore regularly on The Odd Couple. These sightings usually involve TV shows or movies or perhaps passages from novels. Fine arts, however, rarely come up. And the Moon? When the Mets hit your eye like a big pizza pie in a story about a lunar expedition, that’s amore.

It’s certainly curiosity. Thus, I set out to contact Nanette Fluhr; explain my purpose in bugging her; and ask if that portrait in which the word METS, accompanied by the familiar NY, was visible on television would be heading for the sky.

Before I asked, the answer was nope.

But — get this — because I asked, the answer became yup.

Sign of a quality Bar Metsvah. The Mets are going to the Moon! More specifically, “Lonny” is going to the Moon. Lonny, you see, is Nanette’s son. In 2012, he was nearing Bar Mitzvah age and, having a talented mom, Lonny thought it would be neat to greet his guests not with a standard sign-in poster at the Mets-themed party he was planning but with an appropriate portrait conveniently painted by his in-house artist, who is only an all-star in her professional circles. It’s not like Nanette had nothing else to do (she was due at an exhibition in Beijing) and it’s not like circumstances didn’t conspire against her a bit (maybe you’ve heard of Superstorm Sandy), but how often does your son’s Bar Mitzvah come along? Working off a photograph of her Mets fan son in his preferred garb, she created a portrait that was not only the hit of his coming-of-age celebration, but wound up on display at the Long Island Children’s Museum. It captures a boy on the cusp of manhood taking seriously the one thing we can all relate to taking seriously: baseball.

“He was happy-go-lucky in all his other pictures” from the photo shoot Lonny participated in as prelude to his mother choosing something perfect to paint, Nanette recalls. “But he was so serious” once he got into his Mets-tinged headspace. Initially, she referred to the portrait as “Determination,” though she now simply calls it “Lonny”. It stands today as a reflection of another time. Lonny is 22 today, but Nanette is grateful to have such compelling evidence that he was once 12 going on 13.

When it came time to answer Dr. Peralta’s initial call regarding what works of hers she’d like to see make the Gallerist Collection of “itinerant art, photographs and poetry” and make their way to the Lunar South Pole in 2023, “Lonny” did not make the cut. Not because she didn’t cherish it. If anything, it was because she cherished it too much. Part of the deal in choosing Moonbound art was, for the most part, it had to be art that was out in public, up for sale. A portrait of her son on the eve of his Bar Mitzvah, was not something a proud and sentimental mother had any intention of selling.

But what are deals without loopholes? Once your correspondent got in touch with Nanette to find out if “Lonny” was going to make that big trip, the query moved her to ask Dr. Peralta if an exception could be made to whatever rule prevented her from adding “Lonny” to her selections. “Let’s get ‘Lonny’ on board,” was his response.

Coming to a Moon near you. Thus, “Lonny” is going to the Moon — and the real-life Lonny is over the moon about it. Turns out Nanette’s son is “an astronomy nut…obsessed with the vastness of the universe” who was a little disappointed that his likeness wasn’t originally ticketed for liftoff. But now that he, and by extension, the Mets are part of the Lunar Codex, everybody’s happy. I’m thrilled because by watching TV and getting curious, I’ve apparently played some small role in getting the Mets to the Moon, just like that banner in 1969 suggested was franchise destiny. Nanette is delighted not only because she could do this for her son, but because she’s earned an Oscar’s Cap. No kidding. Not that she knew what an Oscar’s Cap was before I told her about them, but she played the one and only cigar-loving Oscar Madison in a junior high sketch, so how perfect is all of this? “Serendipity” is the word Nanette uses to describe this sequence of events. Amazin’ fits the bill, too.

by Greg Prince on 25 May 2022 9:56 pm To paraphrase the late, great Roger Angell (for neither the first nor last time in this space), specifically what he said about his presence in Boston during Game Six of the 1986 NLCS while the Mets were cheating death in Houston and baseball had “burst its seams and was wild in the streets” in New York, what I missed by not being awake for the Mets’ stunning comeback and subsequent backslide amid the wee, small hours of Tuesday night may have been less than what I gained from having absolutely no idea of what transpired at Oracle Park as I sawed wood. Drifting off with SNY on across the living room is nothing new, particularly when a continent separates us from our home team. But the 8-2 trailing of the Giants, combined with an overwhelming desire to visit dreamland, compelled me to smash the “off” button on the remote control, something I almost never do, regardless of hour, when the Mets are in progress. Zs sometimes win out, just as the Mets occasionally appear destined to take an L. “I just hope this” — Chris Bassitt’s 11.32 ERA in two starts versus San Francisco in 2022 — “isn’t a thing if we see these guys in the playoffs,” was my last waking baseball thought as I reluctantly silenced Gary and Keith.

Less than six hours later, I stirred to tentative life on the same couch where I conked out in the fifth. I discerned the time from the clock that has sat atop the Princes’ sturdy standard-definition TV since 2004, deduced that the game I slept on must be over by now, then reached for my modern phone in search of the final score. There was a notification of a text greeting me. Chances were it was either a marginally helpful automatic reminder (a prescription is ready, a payment is due) or it was Kevin. Some Metsian correspondents reliably email me. Some choose to DM or IM their LGMs. If this wasn’t a utility or a pharmacy — and it wasn’t — the medium was going to be the message. I instinctively knew the text was Kevin’s; Met-related; and potentially momentous. Kevin wouldn’t be texting me during a late night West Coast game on a whim.

“Holy shit,” is what Kevin needed to let me know at 12:42 AM. Three minutes after, he added, “It was 11-8 at the end of the 10 run 8th in 2000.”

YOU MEAN WE WON? That wasn’t my response via text. That was what I thought, because who invokes The Ten-Run Inning and all it implies on spec? Kevin, especially; he doesn’t mess around when it comes to Mike Piazza. It wasn’t yet 5:30, so I wasn’t fully unfuzzed from sleep. I needed further confirmation that sleep was a bad choice. I made my way to the MLB app. It would tell me what I needed to know — if not what I wanted to read.

The Giants, as you know by now, won, 13-12. There was indeed an 11-8 Mets lead, which didn’t jibe with the 8-2 deficit I shut my eyes on, but these Mets are regularly unimpressed with other teams’ advantages. It still looked too weird to be true. I picked up my iPad and hoped Baseball-Reference’s late city final had been delivered to my digital doorstep.

It had. The full box score with its line-by-line play-by-play was hot off the presses. The Mets had hopped from 8-2 to 8-4 on a Lindor homer in the seventh, BB-Ref explained, and then leapt the leap of a thousand Endys by scoring seven runs in the eighth. Seven-run innings have become to the 2022 New York Mets what portraits were to Felix Unger, commercial photographer: a specialty.

Mets magic greeted me in data detail. The bold type indicating run-scoring plays. The multiple Rs indicating multiple runs driven in. The pleasingly steep column of Met at-bats. A three-run triple from Lindor (six RBIs in all) catapulting the Mets above the apparently undaunting hills of San Francisco. The lead taken on a sac fly by Pete Alonso. Ohmigod, it really was 11-8, Mets.

So how did we lose, 13-12? I rode up and down the Baseball-Reference rollercoaster to piece together however many of the three hours and fifty minutes of highs and lows I missed in my misguided fit of drowsiness. Why do I keep seeing Joc Pederson’s name? And wait…we gave up the lead, got it back, and lost anyway? The penultimate Met lead was surrendered by Drew Smith, huh? All right, but what about Edwin Diaz?

Oh. Or, more accurately, oh, Edwin. For Diaz’s first three seasons in Queens, that would have been snarled. Here, it was offered with empathy. I felt bad for the closer who’d mostly slammed doors since April. Surely he’d done his best. They all had. They would have been forgiven by dawn’s early light for throwing in the towel as I had. It’s been too beautiful a season to date for serious recriminations. That they held that towel in abeyance with as much grip as they could manage instantly placed my gut reaction to this game in a special cupboard I keep for losses that are too gratifying in their feistiness to festoon with anger.

There was the third-ever Subway Series game, June 18, 1997, two days after Dave Mlicki pitched The Dave Mlicki Game. David Cone was no-hitting the Mets until the seventh. Trailing by one in the eighth, pinch-runner Steve Bieser, at third, teased a balk from the intermittently perturbable Cone and earned a free trip home to tie the game. That we lost it in ten almost didn’t bother me. We’d taken the first game, lost the second and spiritually rated a draw in the finale versus the big deal defending world champions across town. We’d done good, I told myself. It’s been too beautiful a season to be mad at coming close and falling short. We’re on our way up.

There was Game Six, the 1999 NLCS, Braves 10 Mets 9 in 11 innings, except it had been Braves 5 Mets 0 in the top of the first, and everything thereafter filled me with shock and pride (give or take a few balls out of the left hand of Kenny Rogers). That the pennant was lost that night at Turner Field is no small detail, but I can never really rile up over how the Mets ultimately fell. They were practically squashed from the outset yet somehow they almost won, almost forced Game Seven, almost went to the World Series and hypothetically almost won it all. We’d done good, I told myself again. It was too beautiful a season to be mad at coming close and falling short. We glimpsed the mountaintop.

That’s what Giants 13 Mets 12 felt like, especially since I didn’t live through its crushing conclusion in the conscious sense. On the iPad, via the team-friendly Mets.com highlight montage and in the string of quotes testifying to the benefits of clean living and staunch determination — “Remarkable to watch them compete every night”; “The whole team did well”; “We came from behind, and they came back in the eighth”; “I’m super proud of everybody here” — the near-miss was a triumph in the soul if not the line score.

I love the feel of perspective in the morning. It feels like victory.

***

Cribbing Angell again, this time from his regretting wasting Memorial Day weekend in the country while the 1969 Mets found their footing at Shea…

MAY 25: Giants take third game of series while I stay awake for entire affair. Bad planning.

This one goes down as The Thomas Szapucki Game, a far cry from what it meant to be Mlicki a quarter-century ago. We last met Szapucki on a steamy night somewhere on the outskirts of Atlanta at the end of last June. The final then was 20-2. The final Wednesday afternoon was only 9-3. Neither could be processed as any kind of win, not for the Mets (who broke their heartening streak of wins following losses and finally dropped a series to a National League foe), not for the youngster whom we have to stop meeting like this. In 2021, Szapucki was one of a seasonlong long parade of relief cameoists. This time he was plucked from the bottom of the Mets’ starting pitching depth chart to fill an unforeseen hole in the schedule. Once you got past March’s projected rotation — it used to include Jacob deGrom — then the injuries that have occurred since (Megill, Scherzer), then dealt with the icy fallout from last Friday’s Denver snowfall, after which no starter on staff reached Wednesday with ample rest, you found yourself relying on your No. 9 option.

If you can’t get a few decent innings out of a pitcher you deem competent at Triple-A, you may want to drop him into double-digits as you rank future possibilities for a stray spot start. Young Thomas, bereft of command, rhythm and savvy, gave the Mets one-and-a-third frames of the most dreadful sort. Joc Pederson was still scalding the ball, as if rock ‘n’ rolling all night allowed him to party every day. Evan Longoria was at least as hot. Mike Yastrzemski warmed to Szapucki’s stuff, too. The San Francisco trio homered four times among them. Wilmer Flores doubled twice before Buck Showalter realized Szapucki shouldn’t be there for us. It was 9-0 and the second wasn’t done. Four relievers proceeded to hold San Fran at bay the rest of the way, but by the point Szapucki’s short stint served to instigate a full employment act for Williams, Holderman, Shreve and Lugo, the game was irredeemably all wet. Three Met runs crossed the plate between the third and the eighth, and we now cling semi-seriously to the notion that we’ve got them right where we want them whenever we’re way behind, yet there was no hint of the kind of comeback that roared while some of us slept. The spirit can only will so much in a single 24-hour period.

This week’s episode of National League Town pays its respects to both Roger Angell and Joe Pignatano, two figures who immeasurably enhanced the Mets-loving experience from 1962 forward. You can listen listen here or wherever you seek your podcast pleasures.

by Jason Fry on 25 May 2022 2:03 am Once upon a time the Mets were down six runs in the seventh and with my eyes on bedtime I composed a minor recap I knew wasn’t a classic but thought did its duty well enough, particularly grading on the curve for West Coast night-owl duty. It was called “Ten Commandments for a West Coast Loss,” and it was mildly melancholy and warmly philosophical and other things you can probably guess.

And then all hell broke loose and the backspace key and I spent some quality time together.

In the eighth the Mets scored seven runs on eight singles and a triple, sending 12 men to the plate yet somehow only seeing 38 pitches. They didn’t need to work deep counts because slapstick reliably ensued — fielding miscues, balls sneaking through holes and pretty much any other form of mayhem one might imagine. When the dust settled some time later — 40 minutes? a week? — that 8-2 deficit had become an 11-8 lead, Stephen Nogosek was in line for his first career win after doing yeoman work in a seemingly lost cause, and the entire dugout was exchanged dazed grins.

Ah, but innings feature two halves. Drew Smith retired the first two Giants and it looked like San Francisco would slink off to think about what they’d collectively done, but then Smith allowed a single and a walk and Joc Pederson hit his third home run of the game, a cruise missile that came down in McCovey Cove. The Giants settled for sending nine guys to the plate, collecting four singles and that homer on 36 pitches, and the game was tied.

So of course Dom Smith tripled to lead off the ninth and of course he scored and somewhere in there I told my kid, “Pederson is totally coming to the plate as the potential last out.”

And of course Edwin Diaz came out and looked shaky and got a double play and walked a guy and allowed a single and holy cats there was Pederson again, with a muse singing of his rage. Would he hit a fourth home run? No, but a bolt of a single up the middle was enough to tie the game (and give Pederson an eighth RBI) and before anyone could get done being mad at Diaz Brandon Crawford had spanked a single to left and there was going to be a play at the plate on Darin Ruf, recently seen caught in the netting like a crew member doing pre-viz for The Hobbit, and I allowed myself a brief bump of hope before realizing that the throw was coming in a half-second too late, which was correct and the Mets had lost.

I mean, that was madness. It was bonkers. You could have had both teams play in zero gravity and do Whip-Its before each pitch and it wouldn’t have been much nuttier. And somehow these two teams will be expected to play tomorrow, instead of sleeping for three days and then starting therapy.

Yes, tomorrow. Which, for those of you who aren’t lunatics, means today. Late-afternoon matinee New York time, Thomas Szapucki reporting for circus duty. As I now don’t need to tell you, anything could happen and probably will.

by Greg Prince on 24 May 2022 2:41 pm Joe Pignatano was the bullpen coach. He was the bullpen coach when I got here. He was the bullpen coach forever. I’m using past tense only on a technicality. Forever is a mighty long time.

Piggy, as he was known also forever, has died at 92. The ballpark in whose bullpen he famously cultivated tomatoes preceded him in death, but like Joe, Shea is eternal. Picture an affable chaperone keeping loose tabs on a clowder of purring arms — firemen, long men, swingmen, journeymen, screwballers, forkballers, young fastballers seeking the zone, old junkballers fooling the years — and you see Joe Pignatano. Dad’s in the dugout. He can’t be everywhere. “Hey, Piggy,” he asks his next door neighbor, porch to porch. “Do me a favor and watch the kids while I’m working.”

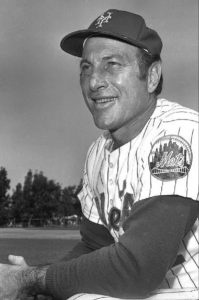

Piggy, preparing for another season. Sure thing, Gil. And Yogi. And Roy McMillan, Joe Frazier and Joe Torre. Piggy was on the staff of every Met manager from 1968 through 1981. He tended the bullpen’s vegetation and he raised relief pitchers. His garden proved plentiful.

Joe Pignatano, in case you hadn’t heard while he wore a Mets uniform, came out of Brooklyn. Of course he did. “He was a Brooklyn Italian,” his son told ESPN’s Elizabeth Merrill not long ago. “You give them a patch of dirt and they plant tomatoes.” Naturally enough, Piggy sprouted as a Brooklyn Dodger. He tagged along to Los Angeles when the Bums decided they needed to be glitzier and ritzier. The backup catcher to Johnny Roseboro stayed tight with certified Boy of Summer and future Hall of Famer Gil Hodges. The last miles of their active-player journeys crossed paths on the 1962 Mets — Piggy’s final batted ball resulted in a triple play in his team’s final loss among many — and joined forces anew in Washington mid-decade. Hodges managed the Senators. Pignatano became his trusted aide. Like fellow lieutenants Rube Walker and Eddie Yost, they followed the manager home to New York. With Gil, they grew a champion.

On April 2, 1972, as Spring Training ground to a striking halt, Gil golfed with his trusted coaches. Then he fell, never to rise. Pignatano was with him to his dying breath. Then, once there was a season, he stayed at Shea, assisting Yogi Berra as he would assist the men who succeeded Gil’s successor. Eventually Piggy took on first base coaching duties, but that, like the past tense, gets filed under technicalities. He was…is always our guy in the bullpen, always one of Gil’s guys, always as warm and funny like everybody says, always around to relive 1969 — and a Mets fan always finds time to relive 1969.

Go ahead. Pick up the dugout phone. Call down to the pen. Piggy will step around the vines, answer promptly and relay the proper instructions to the right lefty and the appropriate righty. The man knows his crops.

by Jason Fry on 24 May 2022 1:57 am What was going through Darin Ruf‘s mind as he lay on or perhaps in the netting in San Francisco while the ball he’d been pursuing bounced around somewhere nearby in an entire-world sense but entirely too far away in a make-a-baseball-play sense while a less-than-ideal quantity of Mets hustled around the bases?

Perhaps he was thinking that it might be a long night.

Or maybe he wasn’t thinking anything like that. Yes, two Mets scored on the play, but only two because the ball that had so rudely eluded Ruf did him a slight favor and hopped into the stands. There were two outs, it was only 2-2 and David Peterson hadn’t looked invulnerable out there, surrendering a home run to Brandon Crawford. And the Mets hadn’t so much pounded Alex Cobb as they had pecked at him with infield hits and little dunkers. And hey, slapstick is an occupational hazard when you’re a first baseman pressed into service in left field because a whole roster worth of outfielders are on the IL.

Maybe Darin Ruf is an optimist. I don’t know the man.

If he is, well, that was about to be tested. The next guy up for the Mets was Pete Alonso, and Cobb’s first pitch to him was a 12-3 curveball.

I know what you’re thinking. Jace, c’mon man. I know it’s late and West Coast recaps are tough, but for God’s sake you’re thinking of a “12-6 curveball.”

You’re right! That is what I was thinking of and presumably what Cobb had in mind too. But it wasn’t what he threw. The ball hung about midway down the center of that imaginary clock face, and at about 3 p.m. it encountered Alonso’s bat and then was last seen becoming a souvenir 391 feet away. It was 5-2 Mets, and that turn of events would make even an optimistic out-of-position first baseman feel a little down.

It was 5-2 and it would get worse, as Peterson settled in and the Giants’ bullpen surrendered some more infield hits and some of the outfield variety and two that went over the fence, with one hit by Jeff McNeil threatening to land in Alameda. Eventually they had outfielder Luis Gonzalez out there on the mound, and he put up a better line than Mauricio Llovera, who got whacked around enough to deserve at least two Ls.

Not a bad birthday for Buck Showalter. Not a bad start to the series in San Francisco. But when you win by 10, there’s not much bad to be found anywhere.

by Jason Fry on 23 May 2022 2:21 am The Mets have now played the Rockies for more than a baseball generation, but games in Denver will always seem bizarre — incredible shifts in temperature, snow-outs in late May, humidors and breaking balls (or the lack thereof), and the strange neither-here-nor-thereness of the team being far from home but not quite on a West Coast trip.

But the constant through it all has been that a five-run lead feels like a two-run lead, being ahead by three feels like a tie, and being up by one or two can even somehow feel like you’re behind. That was true from the jump, when the Mets helped the Rockies open Coors Field back in April 1995: The Mets came back from a 5-1 deficit when Todd Hundley connected for a sixth-inning grand slam, lost an 8-7 lead in extra innings (with nary a free runner in sight), took the lead again, and then got walked off by Dante Bichette. So was the template established: In Denver the other shoe is always about to drop, and when it does, the lack of air makes it land heavy. Succumb to a late-afternoon baseball nap and you can easily wake up to find home plate has been worn out by foot traffic and the score has gone from hectic to insane.

Very occasionally, though, you get a different kind of ballgame, one that resembles baseball on Earth. Back in 2010 the Mets won at Coors by a 5-0 margin behind Mike Pelfrey — the only time they’d shut the Rockies out in their home park. (Turns out I had recap that day and didn’t mention the feat, though for some reason I did include a still from Being John Malkovich. If you’re curious, the Mets have been shut out once at Coors Field, back in 2001.)

Then came Sunday.

Taijuan Walker may be the rare pitcher suited for arena baseball — Rockies hitters spent the better part of seven innings hammering his splitter into the ground, with only four outs recorded in the air. But the Mets didn’t have much luck against Austin Gomber, and the game was 0-0 in the sixth. Yes Virginia, at Coors Field. That was when the Rockies came apart, as Randal Grichuk turned a Brandon Nimmo single into a triple, followed by hits from Francisco Lindor and Jeff McNeil and an RBI groundout by Pete Alonso.

The Mets had a 2-0 lead, though this was Colorado, so it felt like they were actually behind — the first two Rockies singled, leaving Walker’s victory in danger of evaporating in the thin air. Walker coaxed a double-play grounder from Jose Iglesias, but pesky rookie Brian Serven slammed a ball past third.

Past third but not, it turned out, past Luis Guillorme.

Guillorme has been one of my favorites for years, with soft hands, a calm demeanor and flawless baseball instincts — he’s one of those players you can rely on to be in the right place and throw to the correct base without having to think things through. Severn’s hot shot knocked Guillorme backwards, but the ball stayed in his glove and he scrambled to his feet, completing the circle momentum had already begun, and fired a missile to Alonso at first, retiring Serven by two steps and getting Walker out of the inning. And he’s somehow hitting .338!

Of course, there were still six outs between the Mets and victory, which can be a hard road in Colorado — and the journey looked harder when Adam Ottavino sandwiched a pair of walks around a groundout. Ottavino rides his frisbee slider to great effect except when said frisbee starts sailing a little too far, in which case that slider can wind up riding him. It can be frustrating to watch, but Ottavino doesn’t scare, and he took apart the dangerous C.J. Cron on three pitches, then left in favor of Joely Rodriguez, after which Edwin Diaz secured the win.

Ho-hum — except a 2-0 win in Coors Field is anything but ho-hum. Here’s one to remember in another decade or so, when the Mets once again finish a game in Denver with that rarest of sights on the scoreboard — a zero.

|

|