The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 7 July 2025 7:20 pm Funny what a week can do. Last Monday, we were all grateful the Mets didn’t have to play baseball following a long weekend’s disaster in Pittsburgh — and not terribly distressed when Tuesday was also a washout. Now, it feels a little irritating to not be tuning in to watch them.

On Sunday the Mets battled the Yankees in what turned out to be a perplexing, frustrating finale, but one that also yielded some valuable context.

The forces of good put themselves behind the eight ball from the start, ad-libbing a bullpen game against Max Fried. That was unavoidable; some of the in-game decisions, however, were not: Why not bring in a lefty to face newly minted Met Killer Clay Bellinger? Why pitch to Aaron Judge when the worst-case scenario is anything other than a solo homer?

Those stuck in the craw, as the Mets wound up in a 5-0 hole. But they fought back, showing a quality that had been lacking during their June swoon, drawing within a single run and nipping at the well-gashed heels of the Yankee bullpen for the rest of the game. In the end, they were undone by a trio of double plays: Hayden Senger grounded into one in the sixth with the bases loaded and nobody out, Juan Soto lined into one in the seventh (more on that in a bit), and Brett Baty lined into another in the eighth. Three golden or at least potentially shiny opportunities turned to dross before our eyes in three straight innings, which is the baseball gods not being particularly subtle about telling you it isn’t your day.

The middle double play was another sign from those baseball gods: With nobody out and Francisco Lindor on first, Soto hit a seed into left that Bellinger somehow caught a whisper off the grass, the ball almost behind him. Most of the time, a ball like that skips by the left fielder, with announcers bemoaning not playing it safe once all the enemy runners have stopped pell-melling their way to the farthest base they can reach. But nope, Bellinger caught it — and had the presence of mind to spot Lindor too far off first and make a remarkable throw to double him off. That’s quite enough from you, Clay.

(Yeah, there was a ninth-inning AB by Luis Torrens that made you want to give John Bacon a cane and a tin cup. Robots umps now and all that, but it didn’t tip the game.)

Still, perspective. Here we are grumbling about not sweeping the Yankees and about how Soto isn’t an All-Star (just wait, there’s invariably roster-shuffling ahead of the event), when a week ago we were all pushing and shoving each other to see who got to be first to swan-dive off the nearest ledge.

I’m reminded of something Joe Sheehan wrote earlier this year: “A team projected to play .550 ball doesn’t go exactly 11-9 every 20 games. I keep hammering this point because it’s critical to not overreacting to every four-game winning or losing streak: Whatever you think the in-season variance of a team’s performance is, it’s higher than that. The Angels started the season 9-5, then went 9-18. The Braves followed up 5-13 with 14-8. Last year, the 121-loss White Sox had a stretch in which they won eight of 12. Back in 2023, the A’s were 12-50 when they ripped off a seven-game winning streak that included a sweep in Milwaukee over the playoff-bound Brewers.”

(BTW, you should subscribe to Joe. You’ll be a smarter fan and thoroughly enjoy the education.)

Granted, there’s no being stoic about 3-13. But while we have no idea what this year’s Mets will turn out to be, that stretch is no longer a black cloud spitting gouts of rain and bolts of lightning while we run around in frantic circles beneath it. It’s behind us and today is just a Monday, one which we find ourselves faintly bummed to discover comes without a game.

by Jason Fry on 5 July 2025 10:45 pm The Mets and Yankees spent Saturday afternoon wailing away at each other like concussed prizefighters, as balls were flying out of Citi Field and pitchers took the mound looking like they were bracing for impact.

The Mets struck first, with Brandon Nimmo connecting for a grand slam off Carlos Rodon in the bottom of the first. (After Juan Soto had bunted, which there’s no earthly reason for him to be doing.) Establishing a pattern, the Yankees punched back, though their top of the second only netted them a single run. It wasn’t until the ninth that the pattern broke down: The Mets scored in five separate innings and the Yankees answered back in four.

It wasn’t exactly a game for fans of nuance and small ball: The teams scored 18 runs total, 12 of them via home run — with each team hitting three. The difference was all three Yankees round-trippers were solo shots (Jazz Chisholm Jr., Austin Wells, Anthony Volpe), while the Mets’ homers were a grand slam (Nimmo), a two-run shot (Pete Alonso) and a three-run shot (Alonso again, off luckless major-league debutee Jayvien Sandridge).

The good news, beyond the final score being tilted in the direction of righteousness, was that the Mets finally looked like they’ve shaken off whatever malady wrecked the second half of June. They hit, they played crisp defense, they pitched … well, they pitched better than the other guys.

More on that in a minute; first, though, I have to brag about my predictive powers. Before the bottom of the seventh, I suggested the Mets might make the bullpen’s job easier by scoring, say, four runs. They immediately did so. I also suggested Alonso look for Sandridge’s first pitch and wail on it if he liked it; he did and did. (Rest assured the ~900 times I’m dead wrong before the next winning prediction will go unchronicled.)

Back to the pitching: Frankie Montas pitched better than his final line — he was removed in the sixth after getting nicked by an infield single and a pair of bloops, yet another reminder that baseball is fundamentally unfair. Before that he was both aggressive and effective, washing away the bad taste of the debacle in Pittsburgh. And after Montas’s departure, the Mets survived. Richard Lovelady got nicked for a homer but also advanced the Mets three outs closer to a win; Ryne Stanek and Edwin Diaz then finished up, with Stanek allowing a run but Diaz only contending with a single.

The presence of Stanek and Diaz stuck in my craw, though the braintrust did have an reason, which we’ll get to. Given how hard Stanek’s been worked recently, it was galling to see him come in with the Mets up six; and indeed Stanek’s stuff looked less than crisp and he wound up struggling through a 37-pitch inning, which almost certainly will leave him unavailable on Sunday. (The Mets’ plan for Sunday is to open with Chris Devenski, hand the ball to Brandon Waddell after that, and hope for the best.)

Nor, in isolation, did it make sense for Diaz to defend another six-run lead in the ninth, which might take him out of consideration for Sunday.

But “in isolation” is doing a lot of work here. Both complaints ignore when pitchers started warming. Stanek started throwing with the Mets up just two and searching for six outs; yes, they stretched the lead to six — but by then Stanek was already warm. The same Catch-22 then ensnared the Mets with Diaz, who started warming with Stanek leaking oil and the Yankees a long ball away from cutting the lead back to a perilous two.

So OK, the Mets had their reasons, and fell into a bit of bad luck. But we had our reasons for nervousness too. If it feels like the the Mets are looking no further than the game at hand, it’s probably because that’s exactly what they’re doing, frantically mixing and matching relievers and tapping anyone who can start and saving worries about tomorrow for tomorrow. The good news is that both reinforcements and a reset aren’t too far away: Kodai Senga and Sean Manaea may start before the All-Star break, and the break will let everyone in the beleaguered bullpen rest and reset.

Granted, that break is seven games away. Until those games are in the books, well, scoring 12 runs a game would paper over a lot of problems. It generally does.

by Greg Prince on 5 July 2025 1:36 pm Friday’s late-afternoon sun bathed Jeff McNeil’s chin in enough of a glow to make the touch of gray in his beard quite noticeable to me. Live long enough, and that kid who had torn up Binghamton and Las Vegas so much that he forced a callup and a trade of the veteran in front of him becomes kind of an old player.

Of course McNeil wasn’t exactly a kid when he first crossed the general Mets fan radar in 2018. At 26, he’d never been hailed as a comer the way the various erstwhile Baby Mets we’ve been waiting patiently to emerge into full-blown stardom were. At 33, he’s had his brushes with above-the-marquee prominence, but few have been the enticements to come out to see Jeff McNeil and the Mets. When healthy, he’s usually in the “and the Mets” part of the package, positioned as needed, transcending Super Joe-type utility, if not ever completely releasing his inner Zobrist. Slumps and snits and injuries sometimes get the best of him. There’s a reason “Happy Jeff” arose as a meme. Happy Jeff isn’t always visible. Jeff McNeil as an idea is usually one step shy of Jeff McNeil the ideal.

On Friday, however, good ol’ Jeff McNeil was the first Met you thought of when you considered how the Mets topped the Yankees, 6-5, at Citi Field. The Fourth of July game featured several heartening performances, but it was our very own Squirrel putting us the hell ahead and keeping us the hell there. You always brace for Jeff McNeil to raise a little hell on the baseball field. He’s a carrier.

McNeil at the bat launched a no-doubter of a home run to right in the seventh inning, no doubts detected as long as its flight path remained fair. It did. The Mets were down, 5-4, before Jeff swung. The New Yorks flipped on the scoreboard as soon as he touched home plate, where he was embraced by the runner who’d been on base when he batted, Pete Alonso. Pete Alonso has sat above the marquee ever since he arrived in Flushing, temporally a little behind McNeil. They were having a great run in Triple-A together seven years ago. You tend to forget they’ve been together all this time.

Mets 6 Yankees 5 was hard earned. Yankees 2 Mets 0 was immediate. Our starter, Justin Hagenman, gave up back-to-back homers to Jasson Dominguez and Aaron Judge to commence the very first inning. You don’t want to extrapolate what the “at this pace” will work out to from there, but Hagenman, who had the ball because there was essentially nobody else to give it to, changed the calculation. Making his first start in the majors, Justin adjusted and stopped giving up home runs to Yankees. That’s our idea of stepping up. Soon after, a former Mets starter, Marcus Stroman, gave up a two-run homer to a former Yankees star, Juan Soto, and we had a clean slate as of the bottom of the first.

We haven’t missed Stroman since his departure following 2021. That was another Mets era. But Jeff McNeil was here then. Jeff McNeil has played with a lot of Mets we haven’t missed as well as a few we remember fondly. The veteran who McNeil bumped from second base in 2018 was Asdrubal Cabrera. Cabrera we remember primarily for one bat-flipping, arms-raising home run amid the crescendo of 2016’s Wild Card surge. Cabrera will be back for the Alumni Classic. Jeff and Asdrubal overlapped a little. Hell, Jeff and David Wright overlapped for approximately a minute. Those touching images of Wright waving goodbye at the end of his final September, when David manned his signature base for a few precious innings, steps away from his baseball brother Jose Reyes? It was Wright at third, Reyes at short, and Jeff McNeil on second that night. The rookie was making his bid to join the 2006 division winners.

Reyes will be at that Alumni Classic on September 13, and at Wright’s number retirement ceremony and team Hall of Fame induction on July 19. David and Jose were two above-the-marquee Mets in their day. Their day was long, and stands as eternal, but their apogee was ages ago. Yet they were teammates of Jeff McNeil in the first of Jeff’s thus far eight Met seasons. That will happen around guys who’ve been here forever. In Metsopotamia, eight seasons qualifies as forever.

Some guys you want to be here forever. Someday we’ll say Juan Soto has been here forever, assuming contracts hold and catastrophes hold off. We are in the part of Soto’s extended stay when we are delighted that he’s on the books to be a Met into eternity. The National League’s Player of the Month for June put an early stamp on July with that tying homer in the first, then an authoritative double in the third, which set up the first go-ahead Met run of the day, when Alonso singled to make it Mets 3 Yankees 2. Juan as baserunner read the situation perfectly and slid home ahead of a throw that might have nabbed a less cognizant pair of legs. Juan Soto in July isn’t Juan Soto from May, when the Subway Series all but crashed on his head. Juan Soto is head and shoulders above the crowd these days.

I know, we were talking about Jeff McNeil, but Jeff wasn’t alone in taking down the Yankees the day after the Toronto Blue Jays took the Yankees down from first place in the AL East. We’re not supposed to care too much about what the Yankees are down to, but since they were up next on our schedule, I felt it was due diligence to observe they’d been swept four in Canada. They’re still the Yankees, whatever that means, and these games against them are still what they are, whatever that means. In practical terms, it means Aaron Judge comes to bat once every nine men. We don’t have to ruminate on what that can mean.

Hagenman struck out Judge to end the third, right before Soto and Alonso teamed up to create a Met lead. Hagenman also gave up the home run to Cody Bellinger that retied matters in the fourth, but in light of many a Mets fan likely thinking “Justin Whogenman?” when the game began, he did all right for himself by going four-and-a-third and leaving it at 3-3. Unfortunately, his final baserunner, DJ LeMahieu, trotted in on Dominguez’s second homer of the day, surrendered by Austin Warren. If you’re lining up your pitching for the Subway Series, your plan isn’t Hagenman until the fifth, then Warren, but you don’t make pitching plans if you’re the Mets. You just ask for volunteers.

Warren didn’t give up anything else of substance. Neither did Stroman, though there was another Soto single on his ledger in the fifth. If you were optimistic, it appeared the day would be all about what Juan Soto did next. If you were pessimistic, Aaron Judge’s name would be in that spot. Above-the-marquee names elbow their way into your consciousness during a spotlight series.

With thoughts floating from Soto to Judge and back, here came Ian Hamilton to pitch the bottom of the sixth, and here came Brett Baty, one of those erstwhile Baby Mets, growing up a little more and homering to tie the game at four. The Mets of Hagenman and Warren would arrive in the seventh even. The Mets of the relievers you know better would take over. Those Mets are their own challenge.

Son of a gun, though, Huascar Brazoban returned to the land of the viable in the seventh by pitching a scoreless inning that included a strikeout of Judge. And in the bottom of the inning, we had McNeil performing that aforementioned heroic deed of his, homering off Luke Weaver with Alonso on first.

A most heroic deed, indeed,, but not the most heroic deed the old gray Squirrel would come up with. In support of Reed Garrett — himself struggling to emerge from a Brazobanian zone of purgatory — we’d take notice of McNeil at second. That’s where he was playing on Friday. Sometimes he plays center. We’ve seen him in left and right over the years. Third, too, though lately, what with all the erstwhile Baby Mets learning to crawl as major leaguers with the Hot Corner as their playpen, venerable Jeff prowls other environs. McNeil was a second baseman when we first made his acquaintance. McNeil will be a second baseman when we rush to embrace him when Friday is over, à la Alonso’s greeting for Jeff after that seventh-inning homer. But we’ll get to that.

First, Reed Garrett, huh? On Thursday night, Carlos Mendoza required the services of Ryne Stanek and Edwin Diaz to quell the Brewers. That was an important game to win, just as Mendy needed Ryne and Edwin for Brewer-quelling on Wednesday night. Oh, that was an important game, too. When you’ve very recently been a team losing fourteen of seventeen, every win in your grasp is important. Every grasp at a win figures to merit your two main relievers. But the Mets, so rarely within win-grasping range over the previous three weeks, somehow retained the institutional memory to remember you can’t run out to the mound every single day high-leverage relievers who each give it their all every appearance, necessity notwithstanding.

So no Stanek, no Diaz. Instead, two innings of Reed Garrett, a righty who had less hype when he arrived in our midst in 2023 than Jeff McNeil did in 2018. We reflexively dismissed Garrett as another arm that had fallen off the churn-it truck. Garrett persevered to make a back-end staple out of himself, a circle-of-trustee, if you will. A little off and on, a little up and down, the way almost all relievers are, yet in bullpen parlance a Mets fan considers the highest praise available, he never totally sucked so much that you automatically groaned at the first sight of him warming up.

Though, lately, he has come close to totally sucking. But this was the Fourth of July. This was the opener to the Subway Series. This was a time to believe in our guys. This was a time for our guys to deliver. This was a time for Reed Garrett to face four Yankees in the eighth inning, retire three of them, and allow no runs. It took him fourteen pitches, all of them pressure-packed. But he did the job of a setup man, setting up somebody to protect a lead in the ninth.

What he did was set himself up, because there was no way Reed Garrett was coming out of the ballgame. The bullpen depth chart was in tatters. Go be a closer, Reed. That one-run lead is still a one-run lead in the ninth. Make like Randy Bachman and Fred Turner and take care of business.

Oh, and if you don’t mind, kick it into overdrive and face only three batters in this inning because the fourth Yankee up will be Aaron Judge. Nothing personal, but we don’t want you to face him. We don’t want any Met to face him. He’s Aaron Judge. You understand, don’t you, Reed?

Assignment clear, Reed lined out 2022 NLWCS nemesis Trent Grisham to Brandon Nimmo in left for the first out. Then he teased something of a bouncer out of former batting champion LeMahieu. Oh, it was something, all right. DJ, himself an almost-37-year-old second baseman who’s made himself useful at other postings around the diamond, earned a crown in each league when he was quite a bit younger. Jeff the Queens Army Knife earned his own Champion of Batting title in the senior circuit three years ago. Maybe these two understand one another intrinsically. Maybe it’s why LeMahieu directed his full-count bouncer in the vicinity of McNeil. Maybe it’s why McNeil recognized the bouncer as anything but simple.

The ball, didn’t take its one solitary bounce until it was on the edge of the right field grass. Shifts having been outlawed, Jeff was stationed on the infield dirt, where a second baseman is supposed to be. Unfortunately, the ball was headed well to his left. Fortunately, Jeff recognized its trajectory as it remained in the air. A diagonal dive toward right and an informed lunge smothered the would-be liner after its blessedly brief bounce. Then Jeff was the one doing the bouncing, to his feet, as he grabbed the ball from his glove and fired it to Alonso to cut down LeMahieu.

Two out. If Garrett gets the next batter, Hammerin’ Yank Aaron’s last swing of the day is in the on-deck circle. On Reed’s 29th pitch, Dominguez grounded out simply to McNeil to make it so. The game was over. Mets 6 Yankees 5, see Judge tomorrow.

The old gray Squirrel, he is what he used to be. See McNeil and appreciate a lifelong Met. We expended so much anxiety on Alonso’s decision to stay a Met last winter (and might resume contemplation of his destination again this winter, opt-out pending), that it probably didn’t cross our minds that Jeff McNeil was going on his eighth season as one of us, one of ours. He signed an extension a few years ago. Our 2B-CF of the moment is under contract through 2026, with a club option for 2027. He’ll have ten seasons as a Met by then should nothing derail his presence among us. He encounters approximately one significant ding per year, so his statlines tend to get interrupted by trips to places he assumed he outgrew by his mid-twenties. Fans in St. Lucie, Brooklyn, Binghamton, and Syracuse have all grabbed glimpses of the rehabbing Squirrel. He received a special dispensation to get up to speed in the Arizona Fall League last October because he had been hurt prior to the playoffs, and the Mets wanted him back for the NLCS. He drove in a few runs against L.A., but wasn’t really himself.

Jeff McNeil was himself and then some on Friday. Jeff McNeil hit the lead-taking homer, made the lead-preserving play, and earned himself a piece of above-the-marquee Subway Series history. You know The Dave Mlicki Game. You know The Matt Franco Game. You know The Mister Koo Game. You’ve just met The Jeff McNeil Game. It’s not like you haven’t met Jeff McNeil before, but it’s always nice to remind ourselves who he can be.

by Greg Prince on 4 July 2025 2:40 am Two out of three from Milwaukee…where have we heard that one before? If it wasn’t quite October 2024 at American Family Field in July 2025 at Citi Field Thursday night, at least it wasn’t any more of the second half of this June seeping into this July. Maybe this July will tell a different story from what we were sadly getting used to. Or get us back to where we thought we were going until the middle of June.

It always helps to have your most reliable starting pitcher on the mound. It could be argued the Mets had their two most reliable starting pitchers of the past calendar year toeing that rubber, as David Peterson dueled Jose Quintana. The erstwhile lefty teammates carried much of the 2024 load from midseason onward. Jose then left to join our Wild Card Series enemy, but will always merit Old Friend™ affection. David, meanwhile, continued to emerge as Ace Peterson, Met Corrective. Two subpar starts haven’t detracted from his status, not when there’s been nobody else to challenge him for it. We’d welcome a challenger. We’d welcome anybody remotely capable to join the rotation. These days it’s Peterson, Clay Holmes, and fill in some blanks. Sean Manaea (a fairly reliable 2024 southpaw himself) supposedly isn’t far off from making his return. Nor is Kodai Senga. But they’re not here yet.

Few are.

Before Thursday night’s series finale, which your correspondent covered as credentialed media (meaning a furtive fist pump here, a silent boo of Rhys Hoskins there), the Mets announced Paul Blackburn was going on the IL with a right shoulder impingement, not as serious as the right elbow sprain that is also IL’ing Dedniel Nuñez. Missing Paul Blackburn will mean missing a warm body, based on his performance to date. The next three scheduled Met starters — for the Subway Series, oy gevalt — will be Justin Hagenman, Frankie Montas, and Brandon Waddell. Warm bodies are having a moment.

I found it most instructive to sit in on Carlos Mendoza’s pregame presser and listen to him retrace Blackburn’s steps from last weekend, when the righty tried to give the Mets a little more length after waiting out a rain delay in Pittsburgh. The Mets wanted, and the pitcher did his darnedest to deliver, “another 35 pitches,” which Mendy equated to “asking a lot”.

That, it occurred to me, is what this current season has come down to: somebody, anybody, please give us 35 pitches. Then maybe somebody else can throw another 35 pitches. However many innings that adds up to, just get us there, and maybe somebody else can come in, somebody we’ve heard of. Or somebody whose identity we can learn as we go along. After the Mets made their nightly flurry of moves besides the injured list additions (Hagenman and Rico Garcia are up; Blade Tidwell is down; Austin Warren, designated 27th Man on Wednesday, sticks around), it was reported the Mets signed to a major league deal reliever Zach Pop.

My reaction was, “I’ve never heard of Zach Pop.” I’d also never heard of most of the additions the Mets have made to their bullpen these past few months, even though most of them could claim anywhere from a smidgen to a modicum of MLB experience. Zach Pop has more than that; since 2021, he’s pitched in 162 games, a full season’s worth, despite my failing to notice a very noticeable name clearly destined to join our roster of very noticeable, if preternaturally obscure names. My childhood devotion to absorbing the names and faces on baseball cards notwithstanding, I’m coming to believe that just because somebody is a professional big league pitcher, it doesn’t automatically qualify him as famous.

The view from the other side of the glass. David Peterson, on the other hand, should have his name up in lights for the way he escorted us from the darkness. In this era’s version of Koosman versus Seaver at Shea, August 1977, or perhaps Pedro versus Ollie at Citi, August 2009, this time it was the Met who remained besting the Met who went away. Quintana was pretty darn good for the Brewers, the way he was often pretty darn good for the Mets. From the first to the fifth, the only damage he incurred was a Brandon Nimmo solo home run that bounced giddily off the Cadillac Club roof in right in the second. His undoing in the sixth was of the mythic Wee Willie Keeler variety, as the top of the Met order — Starling Marte, Francisco Lindor, and jersey-giveaway inspirer Juan Soto — all hit balls where Brewer fielders weren’t. Soto’s well-placed single drove home Marte to give the Mets a 2-1 lead and chased Quintana. Versus Q’s successor, Pete Alonso immediately banged one where the left field fence most definitely was, driving in Lindor to put the Mets up, 3-1. Four consecutive hits constituted a rally straight out of magical 2024. Huzzah that it took place in hard-bitten 2025.

All Peterson had allowed through six was one unearned run, in the fourth, the result of the kind of dripping you’d expect on a night that began with a 37-minute rain delay. Nothing was hit terribly hard. Nothing fatally impeded Peterson. Having reached the point where if we can’t count on Peterson, we can’t count on any starter, we were able to count on him to get us into the seventh.

The seventh! No Met pitcher pitches into the seventh! Except for David Peterson, who’s done it a few times this year. This was a great time to do it again, despite his giving up a two-out solo home run to Andrew Monasterio and, with the last of his 103 pitches, an infield single to Sal Frelick. The good news is when your starter has taken you into the seventh, you can skip over the Poches and Pintaros and Pops and proceed directly to the back of your bullpen. That meant Ryne Stanek to get us out of the seventh and through the eighth before handing it off to Edwin Diaz for safe keeping in the ninth. Stanek and Diaz pitched Wednesday night as well. “They won’t be available Friday,” I thought. Then I added to my thoughts, “There is never any tomorrow with this team and this bullpen. Just take care of tonight, and we’ll bring up three more mysterious arms to deal with what comes.”

Stanek did his part to keep it Mets 3 Brewers 2. Diaz struck out his first batter before giving up a Wee Willie special to pinch-hitter Christian Yelich, who made soft but clever contact. Yelich being on first implied Yelich might very well be on second, given that Diaz isn’t a fanatic about holding on baserunners. Fortunately, he’s been working on getting the ball to the plate sooner, and, more fortunately, he had Luis Torrens catching and throwing once Yelich took off; he had Lindor catching and tagging once Yelich slid; and he had replay review seeing how many stitches on a baseball can dance on the head of a pin.

Yelich was initially called safe on a very, very close play. Lindor was adamant the Mets challenge. The Mets did their own due diligence and went along with their shortstop’s judgment that he tagged Yelich’s leg before Yelich’s hand touched second. The challenge was on. I watched replays on the enormous screen in distant center as well as the nearby monitors in the press box. I saw nothing that indicated there was any reason the out call wouldn’t stand.

But somebody in Midtown saw something. What appeared too inconclusive to overturn got overturned. Yelich went from being the tying run on second to the second out. An instant later, Diaz resumed striking out Brewers to end the game in the Mets’ favor.

On nights the Mets have just enough pitching, just enough hitting, and an extra dollop of defense, it’s as if they’re the Mets again. Not the Mets we’ve been thinking they were, but the Mets we were thinking they were before that. I realize it can be difficult to tell them apart. The Mets they were Thursday are the Mets who have a handful of relief pitchers you couldn’t pick out of a sellout crowd, but aren’t compelled to use them.

by Jason Fry on 3 July 2025 8:00 am You know it’s bad when you’re relieved your team isn’t playing.

After getting curb-stomped by the 100-loss Pirates, the Mets didn’t play baseball Monday and that felt like a respite. Then they got rained out Tuesday and that felt like a gift. One could be forgiven for thinking, “Maybe they’ll be rained out for the rest of the year and both they and we can take this opportunity to reconsider our recent life choices.”

But the weather cleared, as it eventually does. The vast majority of us kept watching, as was probably inevitable. And so the Mets went back to work for a Wednesday day-night doubleheader against the Brewers.

The day part, which I listened to via a vaguely clandestine earbud while at work, went about as well as the last couple of weeks have gone. There was a sweet moment when the fans applauded Pete Alonso‘s RBI single with what sounded like empathetic delight; no one takes failure more personally than Alonso, who turns into a Margaret Keane waif during his achingly morose trudges back to the dugout.

That gave the Mets a 2-1 lead, but it wasn’t nearly enough. Reed Garrett reported for duty in the sixth and it didn’t go well: two middle-middle cutters spanked for hits, a robot-umps-now assisted walk, and a Joey Ortiz grand slam. That wasn’t ideal, to say the least, but let’s pause, shovels in hand, before burying Garrett: The Mets’ offensive output on the day consisted of a pair of singles and an HBP, and honestly, converting that into two runs was a near-miracle.

Emily and her dad met up for the night portion of the doubleheader while I was volunteering on the water for Brooklyn Bridge Park’s kayak program. My absence seemed like a wise choice with the Mets set to face Brewers phenom Jacob Misiorowski, whom I wouldn’t have been able to pick out of a police lineup but whose approximate scouting report I’d absorbed through box-score osmosis: stands eight-foot-two, fastball tops 130 MPH, slider comes in at 105 MPH, known to literally eat enemy batters if displeased.

So it was a record-scratch moment when I got off the water, fired up MLB At Bat and saw Mets 5, Brewers 0. Wait, what?

Let this be your latest reminder that baseball makes no sense. Misiorowski had started off his career by winning three straight against the Cardinals, Twins and Pirates but came crashing down to earth with two outs in the second inning against the now-lowly Mets: walk, walk, weird little squibber that Brice Turang couldn’t corral, Brandon Nimmo grand slam … followed, five pitches later, by a Francisco Lindor home run.

Yes, Nimmo and Lindor got flipped in the batting order; given the power of ballclub superstititons and recency bias, we’ll see if that was truly only a one-day thing. (Lindor also got voted onto the National League starting squad for the All-Star Game, an accolade he locked up last October.)

The Mets threatened to give the game back: Blade Tidwell ran out of gas in the sixth and the Brewers clawed their way back to within two runs. Milwaukee then brought the tying run to the plate in the eighth against Edwin Diaz, sending several thousand Mets fans under their couches. But Diaz came back from a 2-0 count, mixing up sliders and fastballs to freeze Jake Bauers, then punched out the Brewers 1-2-3 in the ninth.

Does one really rejoice over splitting a doubleheader with the Brewers in early July? If you’ve been through what we have of late, you better believe you do.

by Jason Fry on 30 June 2025 8:19 am So the Mets had another team meeting … and things got worse.

Worse as in 12-1, worse as in out of it by the top of the second, worse as in Travis Jankowski finished up on the mound (before seeing a 2025 Mets AB, no less). Frankie Montas was terrible, the relievers who followed him weren’t much better, Oneil Cruz destroyed two baseballs, and the Mets’ ABs were wan and lacking conviction. It was terrible and endless, concluding with the Mets not only swept by a 100-loss team but defeated by a combined reckoning of 30-4, the most lopsided series defeat in team history.

The lovable, terrible Mets of Jimmy Breslin chronicles? Never beaten this badly. The in-denial North Korea Mets of the first years after Messersmith and McNally? Never beaten this badly. The not so lovable, exquisitely terrible Mets of the Alomar/Phillips era? Never beaten this badly.

And, I must confess, it broke me.

Being a fan in enemy territory means minding your Ps and Qs — you mute your unhappiness, similar to how criticism of the president used to be on hold when he was overseas. But as Montas trudged off the field after the first something came unglued in me and I began booing vociferously, pausing only to scream “HAVE ANOTHER TEAM MEETING!”

I’m a little embarrassed … but only a little. Sometimes you can’t take any more. The last such eruption I can remember came after Braden Looper was incompetent for the fourth or fifth straight appearance; I booed Looper so loudly that I felt something in my throat give way and was reduced to a whisper for a few days.

The Mets are off today, and few teams have needed an off-day more. It will be interesting to see what happens in response to the weekend’s debacle. Maybe nothing — more stoic “such is life” stemwinders from Carlos Mendoza or Francisco Lindor or David Stearns. Maybe a roster shuffle — luckless relievers out, new luckless relievers in. Or maybe it will be decided that a head or two must roll — if I’m Eric Chavez or Jeremy Barnes, I’d be a little nervous every time my phone buzzes.

Should such a thing happen? Don’t ask me that right now — as attested above, I’m a little too PO’ed to see things clearly.

* * *

Baseball aside, Emily and I had a lovely visit to Pittsburgh and PNC. The first time I saw PNC, I was seeing a lot of new ballparks and wrestling with the question of how to weigh the view from parks in assessing them. My caveat about PNC, as stated at the time, was that the Pirates didn’t build the view of the Pittsburgh skyline, so why fall to the earth praising it?

I’ve rejected that idea since then — siting is part of the design process, and there are plenty of parks that do nothing with lovely views. (Looking at you, Nationals Park.) But my other (mild) criticism of PNC remains: For a park hosting a team called the Pirates, it’s strangely light on pirate-themed stuff. There are watering holes called the Crow’s Nest and Skull Bar, but they’re just names. Three cannons sound when an enemy better gets struck out, but it’s just a graphic on the video board.

PNC needs a big dumb pirate ship, like the Tampa Bay Buccaneers have at Raymond James. You could put it above the spiral ramp in left field, which is currently topped by an unadorned steel trellis of sorts. Have it fire actual cannon blasts (just smoke, you maniacs) after strikeouts, raise flags and launch fusillades after home runs, and hoist the Jolly Roger after wins. The Crow’s Nest should have shrouds and sails and cutlasses; the Skull Bar should have treasure chests and parrots and old maps. PNC is lovely, but it’s also weirdly subtle. You’re the Pirates! Go all in!

* * *

At the beginning of May I started a new dumb tradition: Every month I try to spot all 30 MLB caps in the wild. (T-shirts and what-not count, provided they’re adorning a person and not, say, on a shelf in a clubhouse store). I found 29 out of 30 clubs in May, with only the Texas Rangers escaping me, and so started over in June — with nine days in Europe making this go-round a little more challenging.

On Sunday Emily and I circled PNC a couple of times before the game started, looking for the three remaining caps I needed: the Brewers, Rays and Rockies. I found a Brewers cap relatively quickly (paired, oddly, with a Toledo Mud Hens jersey), then spotted a Rays t-shirt in an outfield bar.

That was 29 of 30, but a Rockies sighting seemed highly unlikely: Who would wear the gear of an 18-win team while several time zones away and attending a Mets-Pirates game? At least the Rays and Brewers are having good years.

But hey, keep hope alive: As we neared our seats, an older gentleman walked by wearing not only a Rockies cap but also a jaunty Hawaiian-themed Rockies shirt. That meant 30 of 30 for June, and earned the passing fan a salute from me: It’s hard to be Mile or High or Die given what the Rockies are enduring this year, but one man was up to the challenge. Respect!

by Jason Fry on 29 June 2025 9:41 am Honestly the rain delay was the best part.

The Mets led 1-0 in the top of the second on Saturday and were at least mildly threatening to lead by more, with Mark Vientos at the plate against the Pirates’ Bailey Falter, two outs and runners on first and second.

Then the skies opened up. It would be 89 minutes before Vientos could resume his AB, this time against Braxton Ashcraft. Vientos struck out; the Mets sent Paul Blackburn back out to the hill and he gave up five straight singles. Exit Blackburn, enter Jose Butto; by the time the inning was over the Pirates had a 3-1 lead.

Emily and I spent the rain delay wandering PNC Park, which upon a repeat viewing lives up to its reputation as one of baseball’s best parks. There’s the journey to and from the park over the Roberto Clemente bridge, the dazzling view of the Pittsburgh skyline across the Allegheny River, and the statues of notable Pirates outside; these attractions have made PNC famous, and with good reason.

But there are also ample areas in which to stroll and gather and even hide from a downpour, and the people who run PNC Park have a welcome laissez-faire attitude toward what you get up to. Emily and I were looking for a spot offering shelter from the rain but also exposure to a cooling breeze, and at one point sought refuse in a semi-closed-off nook next to a Pittsburgh police officer, used to house trash bins and a booth for the Pirates’ kids club. I waited for someone to tell us we couldn’t be there, but that was years of conditioning from Shea and Citi Field — no one so much as batted an eye.

The Pirates fans and Pittsburghers in general proved good hosts on Saturday: The fans at PNC accepted an invasion of Mets fans (many gathered, like us, by the 7 Line) with cheerful grousing at worst; the folks at the flagship Primanti Bros. managed to stay friendly despite New Yorkers’ ignorance of all the sandwich shop’s decades-old routines.

(PNC had a pregame moment of silence for Dave Parker, the legendary Bucs slugger who died just a month from induction at Cooperstown; about half the crowd hadn’t heard of the Cobra’s death, and the shock and grief in the park were palpable.)

Post rain delay, the Mets’ sorely taxed bullpen performed admirably, or at least it did so initially, with Brandon Waddell and Reed Garrett following Butto to the hill and keeping the Pirates at bay. Meanwhile the Mets continued being annoyingly peaceable at the plate, but did draw within one run on a Brandon Nimmo RBI single; in the seventh Nimmo came within a whisker of tying the game, driving a ball to the left-field fence but not off it or over it.

But in the eighth, everything fell apart. Earlier this season Huascar Brazoban looked like he’d figured out how to trust his stuff and throw strikes, chalking up a win for the Mets’ pitching development corps. But Brazoban has given back all those gains in recent weeks, and once again looks like the chronically wild, saucer-eyed reliever the Mets acquired last summer. Brazoban was terrible and newcomer Colin Poche was worse in his Mets debut; Poche arrived with an ERA of 11.42 and somehow left with an ERA of 12.54, which is both hard to do and not advisable. (He also has annoying baseball cards to track down for The Holy Books, which isn’t his fault but … actually who cares, I’m going to blame him for that too.)

When the Mets finished ducking and covering it was 9-2 Pirates, not much of an improvement on Friday’s debacle and proof, I suppose, that baseball offers multiple roads to disaster. The Mets then held a postgame players’ meeting, something they’d resisted during this depressing swoon until it all apparently became too much Saturday.

I’m normally cynical about players’ meetings, but hey, last year’s get-together did coincide with a turning point, when the Mets were far worse in the standings and seemingly far more of a hopeless case. Will the 2025 Mets now also import fast-food mascots and vague-wattage digital-meme celebrities? Encourage Brett Baty or Ronny Mauricio to try their hands at Latin pop songs? Hey, whatever works — because right now nothing is working.

* * *

A postscript: An oddity of my baseball fandom is that I’ve never come away from an MLB game with a baseball. None secured off a foul at the plate, no home runs, nothing tossed into the stands by a fielder or a bullpen catcher.

I’ve come close a number of times, and the problem is that I just don’t react. Balls have bounced in front of me, whizzed past me, spun at my feet — all for naught. Emily, witnessing a ball nearly take out our child while in my arms, exclaimed “for God’s sake give me that baby!”

It’s become A Thing, but Saturday at PNC took it to another level. After the bottom of the first, a Met flipped the last out into the stands, over the net. I was busy taking a picture of the Pirate Parrot for some fucking reason; the Mets fan next to me was looking at his phone. The ball stuck between our shoulders, somehow not hitting either of us in the face and attracting no apparent notice from anyone in front of us.

The next-door fan looked at me; I looked at him; he took the ball. I now feel safe in saying that I will never wind up with a ball at an MLB game — and that this is not an injustice.

by Greg Prince on 28 June 2025 1:31 pm I hope SNY, having sat Jose Reyes in the studio co-anchor chair next to Gary Apple this weekend, never gives our old shortstop any “how to be on TV” lessons, because he’s wonderful as is. On the postgame show Friday night, following the Mets’ 9-1 loss in Pittsburgh, Apple asked Reyes about falling victim to Mitch Keller, a pitcher who came into the game on a ten-game losing streak. Jose’s answer was, in essence, that when he was a player, he and his teammates would be licking their chops to face a pitcher doing so badly. No “every athlete is elite and can compete on any given day” or “Keller is really a much better pitcher than his numbers would indicate” rationalizing. Jose’s message, if I heard it correctly, was the Mets had no business getting shut down by somebody dragging a 1-10 record around.

The same would go for losing to the Pirates, the team that had been 32-50. They’re now 33-50. Against the Mets, they appeared transposed and transformed. The Mets? Behind their heretofore most reliable starter David Peterson, they appeared adrift. The only saving grace to their performance was Blade Tidwell returning from the minors to take Griffin Canning’s place after Canning went down with what has been diagnosed as a ruptured left Achilles and pick up all the innings Peterson couldn’t finish. Blade (3.1 IP, 4 ER) wasn’t any more effective than David (4.2 IP, 5 ER), but he kept the bullpen, including fresh callup Colin Poche, rested. This team always needs fresh bullpen, same as it can use fresh perspectives like those Reyes offered.

The freshest thing in the world on April 23, 1962, was a 9-1 Mets game in Pittsburgh. It was the first win the Mets ever had. Yes, the Mets were once capable of dropping the Pirates by the same score they had dropped on them Friday night. One would guess the 10-0 Pirates of yore, and anybody covering that game for Bucco-coded media, licked their chops aplenty as the sight of the 0-9 Mets. The 0-9 Mets loomed as one big Mitch Keller. The 1962 Pirates had no business getting shut down by some team dragging an 0-9 record around.

But they did, slipping to 10-1 as the Mets rose to 1-9, and even though they managed a dollop of revenge sixty-three years later by flipping the score back on us, it will always stand as the first positive milestone in franchise history. We’ll take a milestone over a millstone any day. And we’ll use any excuse to invoke 1962 if we can. We’d rather do it because “wow, the 2025 sure didn’t play like the 1962 Mets on Friday,” but we’ll take what we can get.

Selective interpretation of results notwithstanding, the 2025 Mets, at 48-35, are a better team through 83 games than the 1962 Mets were through nine or even ten games. Other than occasionally posting an evocative score, the 2025/1962 comparisons should be scant. Yet there is one thing the first and most recent editions of this ballclub have in common:

Really excellent names.

Here in 2025, we have or have had…

One Genesis (beginning anew with the Pirates now)

One Luisangel

One Dedniel

One Huascar

One Tylor

One Minter

One Winker

One Zuber

An Azocar

An Adcock

A Devenski

A Jankowski

A Senga

A Senger

A Stanek

A Kranick (wherefore art thou Joe Panik?)

A Siri who hasn’t answered any queries since early April

Blade Tidwell

Dicky Lovelady (sadly opting for free agency following his humorless designation for assignment)

And, hanging by the bullpen telephone, one call away, Colin Poche

Back in 1962, we had…

One Roadblock

One Choo Choo

One Hot Rod

One Marvelous Marv

One Throneberry (double-dipping, but we’ll allow it)

One Butterball (Bob Botz, cut in Spring Training, but we’ll also allow it)

Two Bob Millers (one known internally as Nelson, neither known as Butterball)

Two Sammys (one a Taylor, one a Drake)

Two Craigs (one whose last name came first, one who was vice-versa)

Elio Evaristo Chacon

Edward Emil Kranepool

Christopher John Cannizzaro

Clement Walter Labine

Donald William Zimmer, a.k.a. Zip, Zim, and Popeye

(Bill “Spaceman” Lee hung “The Gerbil” on Don Zimmer later)

Myron Nathan Ginsberg, better known as Joe

Joseph Benjamin Pignatano, eventually known as Piggy

And, best of all, Vinegar Bend Mizell, whose given name was Wilmer David Mizell, but Baseball-Reference doesn’t even bother with that — he’s Vinegar Bend in their listings, because if you’ve got a Vinegar Bend Mizell on top of a Sherman “Roadblock” Jones, a Clarence “Choo Choo” Coleman, a Roderick “Hot Rod” Kanehl, and a Marvelous Marvin Eugene Throneberry (M.E.T.), hiding it would earn you a demerit.

Oh, and the 1962 Mets had John DeMerit. DeMerit, the 19th Met overall, is still around, one of seven survivors from that first inimitably Marvelous season. Let the 2025 Mets rack up 9-1 scores in the wrong direction. Let the 2025 Rockies rack up immeasurable losses. We have the Originals. We always will.

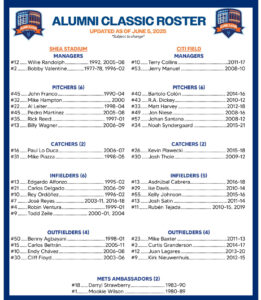

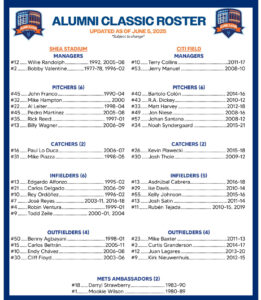

Herrscher from 1962 holds court in 2025 (photo courtesy of Dirk Lammers). DeMerit is joined on the Mets Alumni active roster — if not the itinerary for this September’s Mets Alumni Classic Game — by Rick Herrscherr, who’s been holding court this weekend at the national SABR convention in Dallas; Cliff Cook; Jim Marshall; Craig Anderson; Galen Cisco; and Jay Hook. Howie Kussoy recently caught up with most of these fellas in a terrific story in the Post. These fellas have been telling terrific stories since 1962. The tenor can’t help but have changed with the passage of time.

“We’re at that age, so many have passed away,” Hook, the winning pitcher in that 9-1 decision of so many April 23s ago, reflected. Jay went the distance then, just as he’s going the distance these days. “After the pope passed away, we were watching TV and they were saying the pope was born in December 1936. I turned to my wife and said, ‘Hey, I was born in November 1936.’”

In 1962, that made you practically a kid. In 2025, that makes you, well, someone with quite a memory to mine. Kussoy asked Cisco what it was all like to be one among that first batch of New York Mets.

The Mets Alumni Classic will have team Shea Stadium face off versus Team Citi Field. What’s left of Team Polo Grounds wins simply by sticking around. “It was the perfect time for a new club to step in because they were hungry for National League baseball again,” the pitcher said. “They were such great fans. They loved their Mets. Whenever we’d win a game, the fans would go nuts. They didn’t expect you to win two of three. If you got one, they were satisfied.”

Our expectations have risen since. But win today, and we’ll be satisfied until tomorrow.

by Jason Fry on 27 June 2025 12:15 am Is this glass half-empty or half-full? Griffin Canning left early with an ankle injury, one that looked innocuous on the field but decidedly less so when Canning had to be helped to the dugout. (It appears to be an Achilles injury, which would quite likely be season-ending.) But even as dark clouds gathered overhead, the Mets then dominated the Braves to earn a split and go back into first place courtesy of the Astros’ daytime victory over the Phillies.

Good day, or bad day?

If you want to delay your answer pending MRI results, that’s perfectly understandable. But for me, this split felt like a sweep — a big exhalation for a team and a fanbase that felt like it was strangling.

Canning departed in the third inning of a scoreless game in which he matched up with Grant Holmes, a rotini-haired hurler who looks like Kenny Powers with a primo hair-product endorsement. The portents weren’t great as an overworked revolving-door Mets bullpen tried to pick up where Canning had left off, with Austin Warren first to the hill … and against Ronald Acuna Jr. no less.

But youneverknow, to quote a noted baseball philosopher’s favorite word. Warren only needed two pitches to dispatch Acuna, and then hung around for another two innings, during which he gave up only a single to Marcell Ozuna. The baton then got passed to Dedniel Nunez, who looked gratifyingly like his 2024 self — you could see Nunez’s confidence rising higher and higher as he marched through the Atlanta hitters. Six up, six down and then it was Ryne Stanek‘s turn — and Stanek, too, looked better than he has in some time. Last up was Edwin Diaz, who allowed a solitary annoyance single before closing things out. On the day, Mets pitchers allowed just a trio of singles and nary a walk — not bad for any game, let alone one involving an early emergency and called audibles the rest of the way.

The hitters showed signs of life, too, led by three hits from Pete Alonso. Alonso chipped in an RBI single, but the big blow was a two-out, two-run single from Jeff McNeil on the first pitch from Dylan Dodd in the seventh. Dodd’s name on the back of his uniform looks weirdly like 0000 unless you look closely; guess the Braves could use a font coach.

McNeil’s hit turned a 2-0 Mets lead into 4-0, and I felt at peace for the first time in what’s felt like ages. It felt like the Mets had shaken off whatever this recent bad dream has been, remembering the value of timely hitting and solid pitching and postgame group kicks.

No explanation for wearing road uniforms at home — footage of that one will be a puzzler years from now — but we’ll let it slide.

by Greg Prince on 26 June 2025 1:49 pm “Does anyone still wear a hat?” Elaine Stritch was known to ask. If anyone does — and I know it’s done at Citi Field — I hope hats have been held onto tightly, for the Mets won a ballgame in their ballpark Wednesday night. Surprising, I know.

The Mets, losers of 10 of their previous 11, looked liked their old selves, the selves who’d won 45 of 69 ahead of the skid that commenced nearly two weeks ago and paused only once. Now, they’ve won one of one. Now, overall, they’ve won of 47 of 81, which is to say they are 47-34 after 81 games, which is also to say we have reached the halfway point of the 2025 baseball season.

How the hell did that happen? Wasn’t it just March 27, the Mets in Houston, the new year getting underway? Where did it go? It went to some of the highest Met heights in recent memory before plunging back toward the middle. The heights were too high to let a even a severe two-week dip dent the record too badly, though I suppose there’s still time.

There’s always time. It’s the thing that flies.

Fortunately, there are also still the Mets of the current campaign, the Mets who were, I’m pretty sure, too good to continue spiraling. Living in every season at once as I do, the way the Mets have played versus the Braves and Phillies in particular has sent me back four years to 2021. Remember 2021? I’m gonna guess, despite its relative recency, not much. It’s one of those seasons that evaporated from common Met discourse as soon as it was over. Luis Rojas was the manager. Several people were the general manager (one of them signed James McCann; another of them traded Pete Crow-Armstrong). Marcus Stroman was the rotation’s rock. Miguel Castro saw more action out of the pen than anybody. The Bench Mob — Villar and Pillar; Peraza and Mazeika, Prancer and Vixen — constituted the collective toast of the town for an eyeblink. Things looked good for a while before things looked dicey. Then things went simultaneously west and south.

As of August 12, the 2021 Mets sat in a tie for first place with a record of 60-55. Their next four series encompassed two apiece versus the Dodgers and Giants, a pair of clubs en route to crashing the 100-win mark. You know why L.A. and San Fran won 106 and 107 games, respectively? Because they had the good sense to schedule the Mets. Between August 13 and August 26, they combined to play the Mets 13 games and beat them 11 times. When the carnage was over, so, effectively, was the Mets’ shot at reaching the playoffs.

Ancient four-year-old history, except the contemporary Mets, after losing three of three to the Rays at home; going to Atlanta and losing three of three; going to Philadelphia and losing two of three; and coming home and losing their first two against the Braves, gave me unwanted flashbacks to that not-so-golden interregnum of Jake Reed and Chance Sisco. We’re good as long as we don’t play good teams? Playing good teams is what torpedoed us in ’21.

It’s not ’21 anymore. We have Francisco Lindor and Pete Alonso and Edwin Diaz and Brandon Nimmo and Jeff McNeil and David Peterson now. We had them then, too, but it’s much different in ’25. I’m sure of that.

Pretty sure.

True, we’ve cycled through our share of Dicky Loveladys, Tyler Zubers, and, as of Wednesday, Jonathan Pintaros — 30 pitchers in all this season, plus a designated hitter who threw a scoreless inning — but we also have Juan Soto in ’25. We’re slated to have him in years I can’t guarantee will arrive in a world-teetering-perilously-on-the-precipice-of-extinction sense, but we’ll worry about those years should they get here. We have the Soto we craved in December, the Soto I remember looking at during that first series in Houston, when he was exchanging a few words with Jose Siri in the Daikin Park outfield after one of them had called off the other on a fly ball, and thinking, “Wow, he’s actually a Met, not just a stunning acquisition who shows up at press conferences and swings for sizzle reels, but the guy in right who communicates with the guy in center for our team, just like any Met would.” Except he was Juan Soto, celebrity baseball player I wasn’t yet used to being a Met.

I’m not a hundred percent certain I’m used to it yet, but I’ll take what he’s gotten in the habit of giving us when swinging in real life, a real life that includes two swings like those Soto put on two Brave pitches last night. Juan homered twice for the 27th time in his career, or more than anybody ever has before the age of 27. When Soto was with other teams, we’d hear of such youthful exploits and at most nod toward his excellence. Yeah, that Soto is quite a hitter. What’s that got to do with us? Apparently, everything. Based on his output of June 2025, when Juan Soto of the New York Mets has scalded like the temperature and passed the previously unassailable Polar Bear for the club’s home run lead, Juan Soto being a New York Mets is a condition a Mets fan could and should get used to.

Soto’s two home runs accounted for two runs batted in. Ronny Mauricio’s one home run, one of three hits for the kid who seems to be warming to major league competition, accounted for one run batted in. All three Met homers were spectacular to watch soar into the sweat-soaked night, but they were, when you got right down to it, solo home runs. The beauty of the Mets finally beating the Braves Wednesday was that four other runs scored as a result of other hitting outcomes: two runs on sac flies, two runs on singles. Five runs in all scored in the home fourth, as if the Mets just found out about this new thing called keeping the line moving.

Run prevention also came in handy. McNeil, never a center field for more than a minute until this year, robbed Marcell Ozuna of a home run in the first inning. Clay Holmes, the starter from March 27 and every five or six days since, continued in what had been a novel role for him, going five and allowing only one run. You’d like more length from your starter, even if you have to keep reminding yourself Holmes is a starter like McNeil is a center fielder — just lately. Though you’d always like more length from your starter, you’ll accept as something for your starter-length troubles scoreless innings from Brandon Waddell, Jose Butto, and Ryne Stanek. You’ll even give Pintaro a pass for not quite shutting the door in the ninth inning when tasked with protecting a six-run lead. It was his first-ever big league appearance, and things never got too out of hand. He was even thoughtful enough to create a save opportunity (four-run lead, two men on, potential tying run in the on-deck circle) for Diaz, who efficiently cashed it in by recording one quick out.

The 7-3 win by the triumphant team that makes you forget how bad they look when they lose (just as when they’re losing 10 of 11 they make you forget how good they look when they win) was gratifying especially from a big-picture perspective. The 47-34 record they hold at the season’s halfway point is damn fine. Practically, it’s good enough to have them a half-game out of first in the present. Historically, it’s the same mark the 1969 Mets and 1984 Mets held after 81 games, and we know those live on as transcendent years in the common Met discourse. I’ll try to ignore that the 1991 Mets were also 47-34, yet finished 77-84, having experienced their own 2021-style plunge but worse in the second half (a 4-23 stretch ended not only their division title hopes but destroyed what remained of the most successful era the franchise has ever known).

However other Met years have shaken out, 47-34 after 81 games remains damn fine. Still, the way we were going this year, when we were 45-24 two weeks ago, I figured we’d have touched if not passed 50 wins by now.

OK, I assumed we’d have touched if not passed 50 wins by now.

OK, I assumed we’d have passed 50 wins and be waaay ahead in first place, no sweat.

Alas, there’s been a lot of perspiration in these parts these past few days.

Get a grip… As for time flying, let me redirect your attention to Clay Holmes’s mound opponent in the 81st game of 2025. The Braves’ starter Wednesday night was Didier Fuentes. Didier Fuentes is a young man. How young? Didier Fuentes was born on June 17, 2005. On June 17, 2005, this blog was busy commemorating the 10th anniversary of Bill Pulsipher’s June 17, 1995, major league debut, a 7-3 defeat at the hands of Houston, an event that is a touchstone in the development of Faith and Fear in Flushing. It’s the game for which Jason and I first met in person, outside Gate D at Shea Stadium. We were online friends for a year prior, now we were friends for real. Not quite 10 years later, on February 16, 2005, we started a blog about the Mets, a blog that is still going more than 20 years later.

And, we have learned, four months and a day after we started this blog, a baby was born in Colombia, and that baby has grown up to pitch against the Mets — and lose to them by the same score Bill Pulsipher lost to the Astros in front of Jason and me exactly ten years prior to the day that baby was born.

That baby, now 20-year-old Didier Fuentes, is the first major leaguer younger than Faith and Fear in Flushing. That’s a youthful exploit not even Juan Soto can claim. Living in every season at once as I do, I shouldn’t be shocked at how time’s flight path maps out directly overhead. But, oh baby, this piece of information would have me holding onto my hat if I wore one anywhere outside of Citi Field.

|

|