The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 31 March 2021 11:47 pm Multiple sources are reporting the Mets and Francisco Lindor have agreed on a ten-year extension worth $341 million, meaning the all-world shortstop will remain in orange, blue and occasionally black through 2031, or Steve Cohen will be paying him off handsomely to go away after a while.

Just floating the worst-case scenario to ensure it never happens. Because my words are just that powerful.

Let’s get giddy over this. We were giddy to trade for Lindor. We’re giddy to keep Lindor. Imagine what it will be like to actually root for Lindor as a Met doing something besides smiling and negotiating. Happily, we get to do that Thursday night and a whole lot more nights and days over the decade ahead.

I really like the “41” part in $341 million. If Lindor says it was important that be in there because he understands how much the number means to Mets fans, I’ll love that he’s here even more. But I can probably love that he’s here plenty even without explicit Seaverian acknowledgment.

I also love that Steve Cohen is here. Know any other recent Met owners who would have gotten this done? Hell, I love that we’re all here, us and Francisco and the rest of the gang. Opening Night awaits. The Francisco Lindor Mets await. The 2021 season will feature them any hour now.

We were gonna root for the Mets anyway, and now they include Francisco Lindor for the long haul. What a bargain!

by Greg Prince on 29 March 2021 9:26 pm With Spring Training having concluded Monday following a .500 result (3-3 vs. the Cardinals) and a .500 exhibition record (11-11-2), we offer a hearty Faith and Fear welcome to the all-but-official ten about-to-be new Mets of 2021, each of whom appears slated for inclusion on the Opening Day 26-man roster. Mind you, speaking conditionally is a symptom of living in uncertain times.

Jacob Barnes

Trevor May

James McCann

Francisco Lindor, ideally for years to come

Joey Lucchesi

Aaron Loup

Albert Almora, Jr.

Jonathan Villar, hamstring willing

Taijuan Walker

Kevin Pillar

Your blank slates beckon to be filled with Amazin’ accomplishments. We can’t wait to write about all the great things you’re about to do. Occasionally in black, even.

Looking forward? You betcha!

Looking behind? That, too.

This annual interval on the calendar when we get caught between the Spring and New York City provides us a golden orange & blue opportunity, per Academy tradition, to remember fondly or otherwise those Mets who have — in the baseball sense — left us in the past year.

Cue the montage…

___

BRODIE VAN WAGENEN

Executive Vice President & General Manager

October 29, 2018 – November 6, 2020

But no. “Come get us.” I don’t know if front offices in Atlanta, Philadelphia and Washington reverberated with giggles or were too busy preparing their own rosters to notice the Brodie bluster, but if you’ll excuse a fan for thinking like a fan, somehow I’ll bet the Baseball Gods heard. You know their Karma Council took note. They’re worse than Joe Torre when it comes to handing out fines. Brodie, my man. We embrace confidence in winter. We appreciate positivity when it’s merited — and you were making moves that we could process as positive. But we didn’t need to be overly impressed when simply impressed would do, and we absolutely shudder at the thought of karma being disturbed. Think of it as the oral equivalent of Jacob Rhame throwing high and tight at Rhys Hoskins. Do it once, swell. Do it twice, you’re asking for a 900-foot home run in retaliation. Karma’s not known as a sweetheart.

—June 18, 2019

(Relieved of duties, 11/6/2020; joined Roc Nation Sports as chief operating officer, 1/27/2021)

___

JED CARLSON LOWRIE

Pinch-Hitter

September 7, 2019 – September 29, 2019

Mr. L began our session by telling me he had “that dream again,” his very specific variation on the dream in which a person shows up for the final exam and realizes they haven’t been to class all semester. In Mr. L’s case, it’s what he calls “the baseball dream”. It’s not the first time Mr. L has discussed “the baseball dream” with me in therapy, but it had a different twist today. As usual, it starts with Mr. L wandering around in a mostly empty baseball stadium in winter. He says it’s sort of familiar to him, but not a place he knows intimately In the dream, he again refers to “an agent” who was supposed to be “my agent,” except in “the baseball dream,” the agent is now an authority figure inviting him to join a new baseball team. At first, Mr. L is happy for the invitation.

—September 8, 2019

(Free agent, 10/28/2020; signed with A’s, 2/10/2021)

___

ARIEL BOLIVAR JURADO

Starting Pitcher

September 1, 2020

Perhaps someday I’ll find myself engaged in conversation with Ariel Jurado. We’ll likely talk about his baseball career; how it brought him to the Mets; and the challenges he endured, particularly that night in Baltimore in 2020 when, in the process of becoming the franchise’s 1,107th player overall and that season’s tenth Met starting pitcher 36 games into a 60-game campaign, he experienced what Wayne Randazzo termed a “bloodbath”: six hits allowed his first time through the Oriole order, punctuated by a three-run homer from Renato Nuñez. Or maybe we’ll gloss over that part and focus on his final two innings, for after giving up five runs in the first and second, Jurado gave up no runs in the third and fourth. True, it still calculated to an 11.25 ERA and the Mets were en route to a 9-5 defeat, their fifth consecutive loss, but I’d like to think that tact is the better part of discretion. Hopefully, in this hypothetical scenario, Ariel and I will find happier topics to talk about.

(Free agent, 12/2/2020; currently unsigned)

___

RYAN THOMAS CORDELL

Outfielder

July 27, 2020 – September 27, 2020

Over and over we grow used to baseball that isn’t quite the baseball we are whetting our appetite for less than four weeks from today. It’s the baseball with possible stalemates instead of decisive outcomes. It’s the baseball whose broadcast availabilities are piecemeal depending on your subscription choices. It’s the baseball played predominantly under the sun rather than the lights. It’s getting the hang of things on Piazza Drive as prelude to life on Seaver Way. Mostly, it’s numbers and names. The names that we know will be the names we’ll summer with. For two innings, generally speaking, it’s McNeil, Alonso, Conforto, what have you. For the next seven (no extras), it’s vague familiarity that fills in with increased exposure to Mets who’ve never been Mets in the official sense, may never be Mets in the official sense, but are Mets in late February and, presumably, a while in March. I don’t much know them yet, so until they make a lasting impression, they are who I decide they are. They’re Quinn Brodey, a small-town New England operator with an accent to match in the latest Ben Affleck passion project. He can pahk his cah with the best of ’em and doesn’t even use Smaht Park. They’re Ryan Cordell, a cross between Rydell High from Grease and Cordell Hull from FDR’s cabinet. Ryan and the outfield go together like rama lama lama ka dinga da dinga dong.

—February 28, 2020

(Free agent, 10/28/2020; currently unsigned)

___

JAMES BRIAN DOZIER

Infielder

July 30, 2020 – August 14, 2020

In the eighth, the Mets began to rally a bit. Amed Rosario, shortstop of future past, doubled. Brian Dozier, a Met I will be trying to convince you was once a Met by 2022, was granted an iffy walk on a three-and-two count. Then Jeff McNeil comes up and lines a ball above the second baseman’s head, and… NO! IT WAS CAUGHT! DAMN IT! Nice play, though.

—August 8, 2020

(Released, 8/23/2020; retired, 2/18/2021)

___

ANDREW WALKER LOCKETT

Pitcher

June 20, 2019 – August 28, 2020

I’d formed one impression of Walker Lockett during his 2019 cameo appearances — if Walker Lockett had been around when the annual baseball writers hot stove dinner included musical skits, Dick Young or Phil Pepe or somebody of that vintage would have penned this ditty, to the tune of “Love and Marriage”:

Walker Lockett

Walker Lockett

Every pitch he throws

Becomes a rocket

—September 30, 2019

(Selected off waivers by Mariners, 9/1/2020)

___

TODD BRIAN FRAZIER

Third Baseman

March 29, 2018 – September 29, 2019

September 2, 2020 – September 27, 2020

There was a shadow over home plate not long after the 3:07 PM start in Buffalo on Sunday, but the minor league park there doesn’t have multiple tiers, so the effect of the shadow was negligible. As is the feeling that the Mets are still in it. Sometimes it seems the only commonality between the Mets of this September and last September is an overreliance on Todd Frazier.

—September 14, 2020

(Free agent 10/28/2020; signed with Pirates, 2/19/2021)

___

ALI MIGUEL SANCHEZ

Catcher

August 10, 2020 – September 1, 2020

This, therefore, is what 2020 has come to. Seventeen games in, we’ve had a position player pitch, yet our National League franchise hasn’t had a pitcher hit. Guillorme’s catcher was Ali Sanchez, who came in to relieve subdued birthday celebrant Wilson Ramos when the score was a million to nothing or whatever it was by then. Sanchez became the fifteenth new Met of the year, which is almost as many runs as the Washingtonians walloped. We doff our mask to Met No. 1,106 for coming into our world under the bleakest of circumstances and presumably coming back for more.

—August 11, 2020

(Sold to Cardinals, 2/12/2021)

___

HUNTER DREW STRICKLAND

Relief Pitcher

July 25, 2020 – August 31, 2020

Reliever Hunter Strickland was a Met (fourth club in three years) and, for all we know, might be again. His ERA in three appearances ballooned to 11.57, which will make you an ex-anything awfully quick. Strickland is currently off the 40-man roster but at the Alternate Site in Brooklyn. That’s where relievers with 11.57 ERAs are sent to consider the error of the their ways.

—August 9, 2020

(Free agent, 10/15/2020; signed with Rays, 2/8/2021)

___

JACOB SHAWN “Jake” MARISNICK

Outfielder

July 24, 2020 – September 18, 2020

This is what they’re putting out there as a playoff contender of sorts in September? This is what gets somebody like Jake Marisnick, who helped the Houston Astros win Rob Manfred’s memorial piece of tin in 2017, to say, “this team’s too good to not make the playoffs”? He said that two nights ago, after the Mets were blitzed by the Orioles, 11-2, the day after the Mets coughed up a comeback to the Phillies, 9-8. The 2020 Mets remind me of what Whitey Herzog said about the Mets coming into 1986 off a pair of bridesmaid finishes: “They think they won the last two years, anyway.” The Mets haven’t lacked for outward displays of confidence. They’ve lacked for wins.

—September 10, 2020

(Free agent, 10/28/2020; signed with Cubs, 2/20/2021)

___

TYLER MORRIS BASHLOR

Relief Pitcher

June 25, 2018 – September 29, 2019

So went the Mets’ chances to be unstoppable once Tyler Bashlor entered the proceedings. I guess Mickey Callaway wasn’t intent on winning that eighth game in a row. The Mets won nine in a row under Mickey Callaway at the outset of his managerial tenure and see where it got them. Bashlor has good stuff, I’m pretty sure, but it’s rarely been deployed in the service of getting outs in non-playoff chasing circumstances. It doesn’t accomplish much in potentially headier times, either. Tyler commenced his outing by giving up a long fly ball that PNC Park held; followed it up with two singles; and climaxed his appearance by releasing a gopher into the atmosphere. First it made contact with the bat of Starling Marte. Then it was never seen again.

—August 3, 2019

(Sold to Pirates, 8/1/2020)

___

EDUARDO MICHELLE NUÑEZ

Infielder

July 25, 2020 – July 26, 2020

The Mets didn’t respond in kind. They, too, got to have an automatic runner on second, and he indeed scored, but nobody else did, which made the final 5-3 for not us. Hard to miss in the bottom of the tenth, amid a tease of a rally, was erstwhile pinch-runner Eduardo Nuñez serving as designated hitter after Luis Rojas had him take Yoenis Cespedes’s place on the basepaths in the eighth. The burst of speed seemed clever then. In the tenth, with the bases loaded and the situation Cespy-made, Yo’s bat was severely missed. Then again, the DH is an abomination, so maybe karma reaps what we sow.

—July 26, 2020

(Free agent, 10/28/2020; currently unsigned

UPDATE: Signed with Fubon Guardians of Chinese Professional Baseball League, 4/7/2021)

___

JACOB ALAN RHAME

Relief Pitcher

September 2, 2017 – August 3, 2019

Rhame may just have residual vertigo from all the times he’s been down and up in 2018. Standard-issue option action aside, Jacob has three times out of five been the Mets’ choice for 26th man on those occasions when the roster temporarily expanded because of makeup doubleheaders and the like. In other words, when it’s Rhame, it’s poured.

—September 5, 2018

(Selected off waivers by Angels, 7/8/2020)

___

BILLY R. HAMILTON

Outfielder

August 5, 2020 – September 3, 2020

For eight pitches, it mattered to me that Jeff McNeil reached base. On the eighth pitch, Jeff McNeil took ball four. At that instant, I was convinced the Mets would win. Before I could fully weigh the detrimental impact of my unspoken thoughts on the course of events in an athletic contest taking place on my television, Billy Hamilton came in to pinch-run for McNeil. Before Chapman could fully process the danger Hamilton’s two legs encompassed to the work of his left arm, Billy was off to second base. Because Chapman threw to first base as Hamilton ran, it can be said, technically, that the pitcher had the runner picked off first. But, no, not really, because Hamilton — whose already indefatigable speed seemed kicked up a notch by the presence of 42, twice Billy’s usual 21, on his back — was pretty easily safe. He was now a runner in scoring position. Most nights, having one of those doesn’t fill a Mets fan’s confidence coffers. But this night was different from most other nights.

—August 29, 2020

(Selected off waivers by Cubs, 9/7/2020; has since signed with White Sox)

___

JUAN OSVALDO LAGARES

Center Fielder

April 23, 2013 – September 29, 2019

August 25, 2020 – August 26, 2020

In the top of the sixthish, the lone semi-convincing Met threat of the nightcap went awry when pinch-runner Juan Lagares — oh, Juan Lagares is back (and wearing No. 87) — was doubled off first base; Luis Guillorme’s sizzling liner was caught by Miami first baseman Lewin Diaz with Juan on his way to second. Diaz was much closer to first base by then, so, yeah, double play.

—August 26, 2020

(Free agent, 8/31/2020; signed with Angels, 2/6/2021)

___

CHASEN DEAN SHREVE

Relief Pitcher

July 27, 2020 – September 27, 2020

Score one for dependability, predictability and well-ingrained habit. On Monday night, score seven for the Mets versus only four for the Red Sox, resulting in our second win of the thus far four-game season. Michael Conforto homered at Fenway Park. So did Pete Alonso. So did Dom Smith. Michael Wacha registered five innings’ worth of outs. Seth Lugo retired the final four batters. Chasen Shreve acquitted himself adequately in middle relief. Jeurys Familia did not, but little harm was done. Not bad for late July, eh?

—July 28, 2020

(Free agent, 12/2/2020; signed with Pirates, 2/7/2021)

___

GUILLERMO HEREDIA (Molina)

Outfielder

September 21, 2020 – September 27, 2020

Guillermo Heredia played center for the Mets Monday, having been called up to replace Jake Marisnick, who has a tight hamstring, and then inserted for Conforto, who also has a tight hamstring. A good, loose hamstring goes a long way in getting a person into the Mets lineup these dwindling days of 2020.

—September 22, 2020

(Selected off waivers by Braves, 2/24/2021)

___

ERASMO JOSE RAMIREZ

Relief Pitcher

September 7, 2020 – September 27, 2020

Each of the previous twenty-three Unicorn Scores in Mets history that has thus far gone uncloned was registered in a ballpark […] with an implied sense of MLB permanence. This one, at Sahlen Field, happened where the Mets will likely never play again after this series. And it included the first Met save credited for the questionably strenuous preservation of a lead of as many as 17 runs. Such a perfectly regulation save was assigned Friday to the ledger of the newest Met (No. 1,110), Erasmo Ramirez. Erasmo indeed came on in relief, indeed went the final three and indeed didn’t surrender the inflated advantage he was assigned to protect. That’s a save in any season, even if nobody ever conceived of a Met reliever saving that large a lead. Way to go, Erasmo — if you’re gonna make history, you might as well make it count like nothing that’s ever been counted before.

—September 13, 2020

(Free agent, 10/28/2020; signed with Tigers 1/19/2021)

___

WILLIAM JARED HUGHES

Relief Pitcher

August 3, 2020 – September 27, 2020

It’s the middle of February at the beginning of July. We’re talking camp. We’re talking a veritable plethora of non-roster pickups. Now loosening limbs under the auspices of the Metropolitan Baseball Club of New York are several fellows who span the familiarity spectrum from very to vaguely: Melky Cabrera, Gordon Beckham, Hunter Strickland, Jared Hughes. If this were the middle of February, we’d know what to make of the odd veteran signing. Now we are assuming this bunch will add depth to our 60-player pool, a phrase that didn’t exist the last time baseball went camping.

—July 2, 2020

(Free agent, 10/28/2020; retired, 2/14/2021)

___

ROBINSON DAVID CHIRINOS

Catcher

September 3, 2020 – September 27, 2020

Somewhere post-Hessman, I made my list. There were lists begun before it. There’ve been lists begun since. Every Mets game is an excuse to update at least a couple of them. Some baseball fans referred to the 2020 regular season as a distraction from worrying about the effects of the pandemic or facing up to existential threats to representative democracy. Me, I had the opportunity to note, among myriad other occurrences, that on September 23 — one night after Heredia took Curtiss deep and one night before Chirinos took Corbin deep — the Mets’ record landed at 25-31. And? And it was the FIRST time the Mets ever sported a record of 25-31 after 56 games…if one can be said to sport a record of 25-31. It’s more something an obsessive type types quickly, clicks close on and keeps mostly to himself. But then I opened it just now and shared it with you here on the remote chance you might find it interesting.

—September 28, 2020

(Free agent, 10/28/2020; signed with Yankees, 2/15/2021)

___

MICHAEL JOSEPH WACHA

Starting Pitcher

July 27, 2020 – September 23, 2020

Thus, when Closing Night 2020 rolled around, it was just another game to watch at home. None of the emotions attendant to a final visit to the ballpark. None of that sense that this is the last time I’m getting on the LIRR to change at Jamaica for Woodside…this is the last time I’m getting on the 7 to Flushing…this is the last time I stop by my brick, the last time I get felt up by security, the last time somebody hands me a nick-nack, the last time… There were no last times like the last 25 times to be had. There were the Mets and Rays, in living color, courtesy of SNY and me paying my cable bill. There was Michael Wacha looking kind of promising for a while until the promise broke.

—September 24, 2020

(Free agent, 10/28/2020; signed with Rays, 12/18/2020)

___

BRAD BRACH

Relief Pitcher

August 11, 2019 – September 27, 2020

The Nationals, like the Mets and every Wild Card wannabe, have their flaws, but between the genuine talent (Rendon, Soto), the certified Met-killing (Suzuki) and now Cabrera imagining the need to get even, they have enough of a critical mass to make a Mets fan antsy. Good thing, then, that Mickey Callaway was able to turn to a Mets fan who clearly recognized what was going on, namely his second reliever, Brad Brach. Brach is a Mets fan from way back. Not one of those locally sourced “I rooted for the New York teams as a kid” diplomatic-answerers who doesn’t want to piss off his new fans by admitting he didn’t care or preferred another nearby team, but somebody who, had he not been preoccupied getting outs for other staffs in recent years, would have recognized Kurt Suzuki kills us. Brad from Freehold put his Mets fan instinct to good use and flied out Brian Dozier to get us out of the sixth still tied.

—August 12, 2019

(Released, 2/16/2021; signed with Royals, 2/22/2021)

___

RENÉ RIVERA

Catcher

April 30, 2016 – August 16, 2017

August 25, 2019 – July 29, 2020

Against the Rockies in the Mets’ series finale, Noah Syndergaard perhaps put too much faith in the powers of a personal catcher. Despite the residual simpatico Noah feels for René Rivera’s core skill set from their splendid 2016 together, the Syndergaard who faced Colorado wasn’t markedly better than the Syndergaard who faced Los Angeles five days earlier or the Syndergaard who took on Philadelphia five days before that, both times with Wilson Ramos behind the plate. Those previous starts loomed as dead-letter days in the history of the 2019 Mets, each of them among the myriad losses that buried us for good (with probably a couple more death blows in between). This Syndergaard start — 5.2 IP, 10 H, 4 ER, 2 BB, 4 SB — was similarly grabbing the shovel from the garage and commencing to dig.

—September 19, 2019

(Free agent, 10/28/2020; currently unsigned

UPDATE: Signed with Cleveland, 4/14/2021)

___

ANDRÉS ALFONSO GIMÉNEZ

Infielder

July 24, 2020 – September 26, 2020

Necessarily tossed overboard in the general direction of Lake Erie were two members in good standing of the SS Mets, two Mets SSes. One was the future not very long ago. One was the future literally last week. Today they are ex-Mets. You make this trade seven days out of every seven, Amed Rosario and Andrés Giménez plus minor leaguers Isaiah Green and Josh Wolf for Lindor and Carrasco, but you don’t do it without an ounce of sentimental regret. I’ll miss Rosario and Giménez like I missed Neil Allen, Hubie Brooks and the package of potential and heritage represented by Preston Wilson (Mookie’s lad). I felt bad that they were no longer Mets. I felt great that Keith Hernandez, Gary Carter and Mike Piazza arrived because they departed. Which is to say I got over their respective departures.

—January 11, 2021

(Traded to Cleveland, 1/7/2021)

___

PAUL STANTON SEWALD

Relief Pitcher

April 8, 2017 – July 26, 2020

The two were about to leave the room, when a dazed Paul Sewald wandered in. He’d never seen this room before, but there were lots of things the third-year Met had never seen. After having been the losing pitcher fourteen times but never the opposite, not even once, since the Mets first promoted him in 2017, Paul was enjoying a new sensation of his own. By pitching a scoreless top of the eleventh, Sewald was in line to be the winning pitcher should the Mets score. Once Nimmo drew the bases-loaded walk that brought Amed Rosario home from third, Paul got the win. “Guys! Guys!” Sewald asked Wheeler and Horwitz excitedly. “Did ya see? I’m a winning pitcher — a winning pitcher at last. I’m one and fourteen, but I got one! I finally got one!” The starter and the alumni affairs chief smiled and nodded, telling the heretofore hapless reliever how happy they were for him. “I was beginning to think this would never happen,” Paul confided. “But it has. Finally.”

—September 25, 2019

(Free agent, 12/2/2020; signed with Mariners, 1/7/2021)

___

JUSTIN JAMES WILSON

Relief Pitcher

March 30, 2019 – September 24, 2020

Teams build bullpens on the foundation of a core belief that starting pitchers can’t be pushed beyond so many total pitches and so many stressful innings. Well, teams try to build such bullpens. The Mets tried. I swear they did. What they wound up with instead was a coupla guys. The coupla guys, Justin Wilson and Seth Lugo, have held the bullpen together essentially by themselves for weeks, most recently the night before. On Saturday, it was deGrom for seven, Lugo for one, Wilson for one. It worked perfectly. Now Callaway would ask it — them — to work perfectly again on no nights’ rest. It didn’t work.

—September 16, 2019

(Free agent, 10/28/2020; signed with Yankees, 2/15/2021)

___

FREDERICK ALFRED “Rick” PORCELLO

Starting Pitcher

July 26, 2020 – September 26, 2020

One night this abbreviated season, I got in the car after my weekly grocery-shopping trip, turned on the game, discovered it was another Porcello start going quickly awry, and muttered some pretty nasty thoughts aloud in the direction of a fella who couldn’t hear me. But on Saturday night, after the sweep in D.C. was complete and the Mets dangled one game above finishing in a last-place tie, Rick Porcello took it upon himself to basically apologize for how crummy he and the rest of Mets played in 2020. It was enough to almost make me take back my previous grumblings. “I’m sorry we couldn’t have done better for you, and given you something to watch during the postseason,” the righty said, noting that he was happy he could at least be a part of giving us folks at home a distraction from all that swirls about us. “I wish I could’ve done better for this ballclub. Unfortunately, we’re out of time. I gave it my all and it wasn’t good enough for us.” Rick concluded by adding, “I love the Mets, I’ve always loved the Mets since I was a kid.” It would figure that someone who realized a lifelong dream of playing for “a team I grew up cheering for” would know exactly what to say to us, a cohort that surely includes him.

—September 27, 2020

(Free agent, 10/28/2020; currently unsigned)

___

WILSON ABRAHAM RAMOS

Catcher

March 29, 2019 – September 27, 2020

For a solid month of 2019 — August 3 to September 3 — Wilson Ramos played in 26 games for the Mets and hit in every one of them. The hitting streak was the best by any Met in the 2010s (second only to Moises Alou’s thirty in franchise annals), and it couldn’t have come at a better moment. The Mets were making a bid for the postseason, and their mostly everyday catcher was batting .430 and slugging .590 as they strove. That span included four games in which Wilson came off the bench to extend the streak or, more accurately, help his team maintain its momentum. You can also factor into his monumental achievement that by August, a catcher is bound to be physically run down at any age; Ramos turned 32 on August 10. Oh, and don’t overlook that not every pitcher appreciated this catcher’s defensive abilities, and by September word leaked that at least one batterymate (Noah Syndergaard) was asking for someone else to handle his workload. Another, however (Jacob deGrom), clinched a Cy Young Award by tossing three scoreless seven-inning starts, each with Wilson behind the plate. By 2019’s end, Ramos completed his first season as a Met with 141 games played and a .288 batting average. Catch that, why don’t you?

—December 11, 2019

(Free agent, 10/28/2020; signed with Tigers, 1/26/2021)

___

GERMAN AMED ROSARIO

Shortstop

August 1, 2017 – September 27, 2020

We’ll leave that for the future, unknown though it may be, and concentrate in the present on the half-inning of our most recent past. The tenth inning. The one against the Indians. The one Amed Rosario, the shortstop who bloomed into a second-half superstar as soon as the ink was dry on the organizational plan to convert him into a last-ditch center fielder, led off with a double to center. Since the beginning of June, Rosario is a .500 hitter. Since August 1, Amed is batting a thousand. I could look up what the numbers actually are, but I’m comfortable with the hyperbole.

—August 22, 2019

(Traded to Cleveland, 1/7/2021)

___

STEVEN JAKOB MATZ

Starting Pitcher

June 28, 2015 – September 27, 2020

He’s a happening. He’s a happening because he brought 130 friends and family from Suffolk County and because he’s been working his way back from Tommy John so long that the general manager who drafted him was Omar Minaya and because his favorite adolescent baseball memory involves Endy Chavez and he’s 24 yet looks 14 and he knows to professionally tip his cap when thunderously applauded and he lived up to every expectation we had for him and he built new expectations along the way and he exceeded those. We who were grumpy from a lack of offense even after Duda’s growth charts flapped victoriously roared without reservation for Steven Matz. We were holding out for a hero. We received a folk hero. He’s proof, as if we needed any more, that the designated hitter rule belongs on the ash heap of history. If, say, Cuddyer as hypothetical DH had gone 3-for-3, we might be curious what kind of hallucinogenics they were using at Blue Smoke, but we wouldn’t otherwise be terribly moved beyond vague approval. But Matz going 3-for-3? The pitcher? Never mind the Colon sideshow. This is a pitcher not just helping his own cause. This is a pitcher defining the cause. Let other pitchers pray for run support. Matz answered everybody’s prayers before they could be formulated.

—June 29, 2015

(Traded to Blue Jays, 1/27/2021)

___

YOENIS CESPEDES (Milanes)

Outfielder

August 1, 2015 – August 2, 2020

Without Cespedes in the lineup, they kept winning and were plenty imposing. With Cespedes, where between one and eight in their standard lineup is the letup for the opposing pitcher? Mike Broadway picked a very bad night to be an understudy to Jake Peavy. Cespedes, though…what a star. In a ten-pitch span dating to the previous Friday in Atlanta, Cespedes came to the plate five times, took six swings, delivered four hits, totaled twelve bases and drove in eleven runs. And that was all while letting a debilitating bruise heal. Amid the twelve-run inning and eventual 13-1 win, Yoenis set two Met records of his own: most RBIs by one batter in one inning (six); and most consecutive games with at least one extra-base hit (nine). The Mets he surpassed in these respective realms were Butch Huskey and Ty Wigginton. I liked Butch Huskey and Ty Wigginton just fine in their day. The days Yoenis Cespedes and these Mets are giving us, though? Every day is Christmas. And every night is New Year’s Eve.

—April 30, 2016

(Placed on restricted list, 8/1/2020; free agent 10/28/2020; currently unsigned)

___

FRED WILPON

Chairman of the Board & Chief Executive Officer

January 24, 1980 – November 6, 2020

[A]nother theme the self-inflicted media onslaught emphasized was the owner of the Mets loves being owner of the Mets. Take it from perennially reliable source Steve Phillips: “I know how important the team is to the Wilpon family.” Yet, for what little it’s worth in the big picture, I don’t necessarily equate that with loving the Mets. I’ve never gotten the feeling Fred Wilpon does, not in the way those of us who don’t get to shove blueprints at an architect and tell him to shut up and just rebuild Ebbets Field do. I’m sure he loves the Mets as a property, and that there’s more to the Mets to him than there is to this or that building in Manhattan, but I also get the feeling his acumen was most acute in tending to inanimate objects.

—May 25, 2011

(Sold franchise to Steve Cohen, 11/6/2020; retains 5% ownership share and serves as chairman emeritus)

by Greg Prince on 25 March 2021 9:51 pm Certain Mets seem to come up semi-regularly in this space. Not necessarily from being great and, I’d like to think, not from my being cute or ironic. Certain Mets just hover in my baseball subconscious and briefly but habitually waft above the rest.

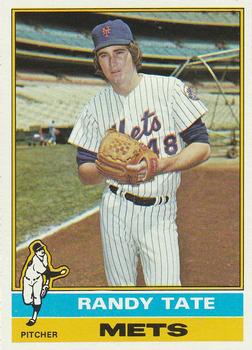

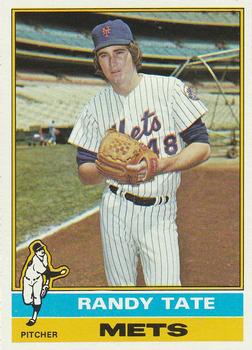

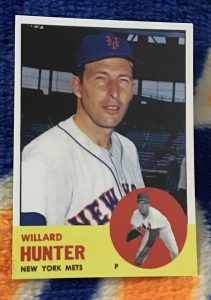

Randy Tate was a certain Met. He pitched for the Mets in 1975. Not before. Not after. I hadn’t heard anything about him in the minor leagues ahead of his major league debut. He appeared at Shea that April, spent the summer, and didn’t pitch there again after that September. Or anywhere else in the bigs. It never occurred to me to strenuously wonder where he went. I figured the Mets had their reasons for elevating Randy Tate when they did and for going in a different direction when they did.

But in 1975, the season I was 12, which is a prime age for forming impressions and attachments, Randy Tate was the Mets’ fourth starter. The rotation was Seaver, Matlack, Koosman, Tate and whoever else was handy. I was already attached to Seaver, Matlack and Koosman. I was impressed that Tate could hang with them.

Randy Tate spent a summer in distinguished company. Randy Tate may not have been in a class with the three pitchers he followed, but for a year he was in their league. Once in a while, he was what you meant when you talked about Met pitching depth. I went to Old Timers Day in late June. Casey Stengel came out in a Roman-style chariot and greeted us, his eternal subjects. Rookie Randy Tate pitched. I watched the Ol’ Perfesser — Casey was 84 — wave, and I watched the latest example of the Youth of America — Randy was 22 — take care of the Phillies for a couple of innings. Then the rains came down and my sister, who was kind enough to bring me in the first place, insisted on leaving, not quite buying my explanation that sometimes it stops raining, a grounds crew dries the field and the teams pick up where they left off. The game resumed while we were on the LIRR to Penn Station, where we’d take another train back to Long Beach. We came home to find Randy Tate on Kiner’s Korner. The rookie had just claimed his first complete game victory.

That was the last time Casey Stengel made an appearance at Shea Stadium. It was also the last time I saw Randy Tate pitch there.

Old Timers Day isn’t what most former 12-year-olds and thereabouts from 1975 Metsopotamia remember Randy Tate for. We go almost immediately to Monday night, August 4, when Randy was going to pitch the first no-hitter in New York Mets history. No kidding, this was gonna be it. Fourteen seasons of Mets baseball and it was already an albatross that we had no no-no. That stupid bird was gonna fly away that night. I could feel it. Bob Murphy could feel it. I listened while in the bathtub. That afternoon my mother took me to the dermatologist in search of relief for the nagging psoriasis on my right knee. The doctor gave me a bottle of tar. Or something with tar in it. Add it to your bath, he said. It had a very strong aroma. I swear I can still smell it, just as I can still hear Murph narrating Tate’s total and complete domination of the Montreal Expos.

The no-hit bid lasted into the top of the eighth. Leadoff hitter Jose Morales struck out, Randy’s dozenth K. We were up, three-nothing. Could this be the night? This had to be the night. I wasn’t a naïve 12-year-old Mets fan, mind you. I’d been at Mets fandom since I was six. No Ned in the third reader as Casey would have said. I wanted to believe Randy Tate would get it done, that our lives wouldn’t be defined by not having a no-hitter for another who knew how many years. This wasn’t Seaver or Matlack or Koosman. This was Randy Tate. This was so crazy it might work.

Except Jim Lyttle, the ex-Yankee, singled to break up the no-hitter, five outs from glory. Murph said the fans at Shea were giving Tate a standing ovation. I hung tight in the tub. The next four batters were all future Mets and three of them destroyed the remnants of the dream I dared to dream for the current Mets. Pepe Mangual walked. Jim Dwyer struck out — Randy’s thirteenth — but Gary Carter singled in Lyttle to end the shutout, and Mike Jorgensen, a former Met as well as a future Met, launched a three-run homer that in retrospect was inevitable. I could hear the heartbreak in Murph’s voice. I could feel the heartbreak while soaking in that slimy black water. Yogi Berra let the kid finish the eighth. Today a rookie who was en route to striking out thirteen over eight wouldn’t see the sixth inning

Tate took the 4-3 loss. I never used the tar concoction again. It was really pretty disgusting.

The next day, Berra managed his last two games for the Mets, a doubleheader sweep, each a seven-zip whitewashing from the Expos. Yogi was fired the day after. Within two months, Casey and Mrs. Payson were gone. And though he couldn’t have known it for sure, Randy Tate was finished as a Met, his career line frozen at 5-13, a 4.45 ERA and 99 batters struck out in 26 games, 23 of them starts. He didn’t immediately leave the organization, instead spending two more years in our minors, pitching for Tidewater in ’76 and Lynchburg in ’77. There’d be an additional season of pro ball in the Pittsburgh chain. After that, you have to visit Tate’s Ultimate Mets Database fan memories page, which is thick with talk of the near no-hitter and the turns his life took in Alabama after baseball.

When I learned tonight through Facebook that Randy Tate, 68, had died from COVID complications, it was again raining on Old Timers Day; it was again tar-drenched in the bathtub; it was again 1975 when a righthander who wasn’t Jacob deGrom wore No. 48 for the Mets and a 12-year-old was thrilled to root for him, even if the 12-year-old knew he’d be forever dismayed that Jim Lyttle broke up what should’ve been the first no-hitter in New York Mets history. Or the second after Seaver got Qualls six years earlier.

With certain Mets, that feeling never goes away.

by Greg Prince on 18 March 2021 4:16 pm One of the rites of Spring is being reminded all in baseball is not as it sounds. For example, sometimes you hear about pitchers going through “dead arm,” and your instinct is to freak out because dead surely sounds like an irreversible condition. But then you’re told, no, “dead arm” is a temporary malady, don’t worry, the arm will come back to life, which it inevitably does. A “sore arm,” which you’d figure is just sore, like you might be after a little too much snow-shoveling or vaccine-getting, is much worse than a dead arm. Unless it, too, is a passing panic, though don’t get a baseball person started on a sore elbow, which is worse than a sore arm, even though an elbow is a component of an arm.

Carlos Carrasco hasn’t pitched in exhibition competition yet this Spring because of elbow soreness. That’s alarming but not an alarm. Carrasco has had elbow soreness before, especially this time of year, and it hasn’t thrown a roadblock into his pitching. Yet it has pushed his timetable back and, though Luis Rojas says his elbow coming along, his right hamstring has been strained, thus it appears unlikely he’ll be ready for Opening Day. (Update: the hamstring has been diagnosed as torn, so Carlos will be a spectator for a while.)

But ready for what on Opening Day? All Carlos would be asked to do on Opening Day is jog to a foul line at Nationals Park and be introduced to a slight murmur of discontent. Jacob deGrom will (knock every piece of wood you have within reach) pitch the Opener for the Mets. Carrasco’s presence on April 1 would be comforting and completist, but from a box score standpoint, unnecessary, unless Cookie is more of a pinch-hitting threat than we’ve been led to believe.

If you’re depth-charting the rotation, you begin with deGrom, then move on somewhat reluctantly to everybody who isn’t deGrom. Ideally, Long Island’s Own Marcus Stroman likely starts the second game, a fully unsore Carrasco is third, and Taijuan Walker is fourth. Or Walker is third. Or Carrasco, hypothetically healthy, is second. Or Walker is second and Stroman, ol No. 0, is third or fourth; how particular can Marcus be about a number if he picked to adorn his uniform a digit synonymous with nothing?

Though certain guys align in certain places in your sports-loving mind, it doesn’t much matter in a vacuum who pitches when after the first game. It doesn’t really matter for the first game except symbolically, though the symbolism of your ace being front and center as a new season begins shouldn’t be underestimated.

What/who we’re leaving out here is someone connected to another rite of Spring: the battle for the fifth starter. There’s almost always “the battle for the fifth starter,” which in the grand sweep of history falls somewhere between the Battle of Gettysburg and the Battle of the Network Stars. Most years the nominal fifth spot in the rotation is open. Once in a while the Mets are so established in their starting pitching that they perceive themselves to be all set, such as when the Mets rolled out Syndergaard, deGrom, Wheeler, Matz and Harvey in sequence in April of 2018…which lasted two entire turns. When you’re sure you’re all set is when you discover you’re not.

The way baseball commences its action — with built-in off days to protect against bad weather in most places; bad weather beyond Opening Day a frequent possibility; and every team that has a legitimate ace wanting to get the most out of its legitimate ace, — generates a related phrase: “They won’t need a fifth starter until…” The Mets have a fifth game on April 6, but if they decide getting the most out of deGrom is paramount and thus use him five days after Opening Day, they won’t need a fifth starter until April 7, the sixth game of the year. Unless it rains in an inconvenient fashion, in which case all bets are off (if, in fact, anybody bets on the identity of fifth starters).

The Mets have three acknowledged fifth-starter candidates in David Peterson, Joey Lucchesi and Jordan Yamamoto. In the unlikelihood Carrasco comes back very soon, he’ll be on track to be the fifth starter the Mets use in 2021 but not exactly “the fifth starter”. Carrasco’s credentials imply he is too highly valued to be “the fifth starter”. “The fifth starter” is a designation in a way being the second, third or fourth starter isn’t. Sort of like we have leadoff hitters and cleanup hitters but nobody really makes much of the batter lurking in the six-hole.

Baseball teams largely went along without fifth starters for a century. The old four-man rotation lingers in the baseball subconscious as an extended “when men were men” moment of inner toughness to which we quit aspiring in our quest to keep arms from deadness and soreness. At some point, the Mets and everybody else will meander into a debate about having six starters. That’s not based on an appraisal of personnel. It’s just what happens every year. You have more than five starters and you worry. You have fewer than five starters and you grow apoplectic, even in this age when relievers starting games for an inning is considered clever. A fifth starter should be the “just right” in a Goldilocks context. Instead, perhaps because of our vestigial reverence for the biggest of the big fours (the ’71 Orioles, the ’93 Braves, the ’11 Phillies), fifth starters are cast into the role that Benjamin Franklin envisioned for the vice president of the United States — “His Superfluous Excellency” — rather than treated as equitably vested 20% partners in any given rotation.

Fifth starters tend to have their utility lopped off come postseason. Remember what the Mets, innovators in the religion of four days’ rest under Gil Hodges and Rube Walker, have always done with their fifth starters in their playoff years? They’ve assigned them to the relief duty. In ’69 we used only three starters. In ’73, George Stone, the fourth starter of his day, got only one start, and you know it wasn’t in the World Series. Rick Aguilera’s robust second half in 1986 (9-4, 2.64 ERA from July 12 forward after a horrid first three months) drew him a seat in the bullpen. Bobby Ojeda’s hedge-trimming made the fifth-starter point moot two years later. Orel Hershiser, Glendon Rusch and Bartolo Colon each went the Aguilera route in their respective postseason Met years of 1999, 2000 and 2015. The Mets barely had four starters to get them through October 2006 and only one postseason game altogether in 2016.

We should be so lucky to have fifth-starter issues in the 2021 postseason. We don’t know if we’ll have our very own postseason this year. We’re reasonably confident we’ll have a “this year,” however — and have it with people! Eventually we’ll have “the fifth starter”. As for who will be our plain old fifth starter, which is to say the fifth starting pitcher the Mets use in a season, that will be up to the elements, injuries and array of unknowables one encounters in trying to deduce too much in advance.

The Mets have played what we’ll call fifty-nine discrete seasons, counting the two 1981s individually. Twenty-three of those seasons incorporated five starting pitchers in the first five games. No off days or contingencies came into play, just one starter after another toeing rubbers and taking aim. It sounds so normal you’d think it was the norm. Recently it kind of has been, with seven of the past twelve fifth games being started by a fifth starter (if not “the fifth starter”). Just last year, which was abnormal as a year could be in every other respect, David Peterson made his season and career debut in 2020’s fifth game, following Messrs. deGrom, Matz, Porcello and Wacha, and that was without making the delayed Opening Day roster. With respect to his current battle with Yamamoto and Lucchesi, you can say Peterson should have an edge from being a seasoned fifth starter already.

Jason Vargas was 2019’s 5/5 man, though if you called him that in the clubhouse, he might threaten to “knock you the fuck out, bro.” Dillon Gee was the fifth starter in the fifth game of 2012 and 2015. In between, in 2014, he was the Opening Day starter, leaving Gee to ponder status whiplash. Hopefully Jay Horwitz got him in touch with Craig Swan, whose Opening Day starts in 1979 and 1980 were bracketed by fifth-game first starts in 1978 and 1982.

Two of your odder-appearing chronological fifth starters to start fifth games were pitchers you automatically associate with starting much sooner. Both cases speak to how injuries and the healing they necessitate can rearrange best-laid plans. In 1992, Dwight Gooden, who started eight Openers as a Met, was coming back from arthroscopic shoulder surgery and needed the extra few days to physically ready himself. Al Leiter, who threw the first Met pitch of 1999, 2001 and 2002, got pushed back after being hit in the head by a line drive toward the end of Spring Training 2004 (during a game in which the Mets and Marlins combined for 34 runs, so we can assume there were lots of line drives). Instead of being that season’s third starter as slated, he waited in line behind not only T#m Gl@v!ne and Steve Trachsel, but emergency starter Dan Wheeler (in for late scratch Scott Erickson) and rookie Tyler Yates. I don’t know about you, but I’d take Leiter ahead of both of those guys. Ahead of Gl@v!ne and Trachsel, too.

Bill Denehy was the first Mets fifth starter to start a fifth game, in 1967. The righty would take seven more starts at Wes Westrum’s discretion before being sent as compensation to the Washington Senators for Westrum’s full-time successor, five-man rotation evangelizer Gil Hodges in the following offseason. Hodges himself used a chronological fifth starter, Don Cardwell, in the fifth Mets game of 1969, a year without a built-in off day following Opening Day.

Given the opportunity to get extra starts out of Tom Seaver early in the 1968, 1970 and 1971 seasons, Hodges didn’t hesitate to push back everybody in sight. The Mets didn’t use a fifth starter in 1968 until their tenth game, when a doubleheader provided a spot for Al Jackson. In 1971, it was classic swingman Ray Sadecki getting his first starting shot also in the tenth game. Cast into a similar “not so fast…” role, fireballer Nolan Ryan had to wait until the ninth game of 1970, April 18, to be the Mets’ fifth starter. Was it worth the wait? Ryan pitched a one-hitter and struck out fifteen, the latter figure poised to stand as the single-game franchise record for fewer than a hundred hours. On April 22, Seaver famously struck out nineteen San Diego Padres, including the last ten in a row. Less famous, but eye-popping to our modern pupils is that the Padre game was the Mets’ thirteenth of the 1970 season, and Seaver was already making his fourth start. (I dare Rojas to try that with deGrom.)

The first fifth starter in Mets history, which is to say the fifth starter the Mets ever used, was Bob Miller…Bob L. Miller, to be exact. Casey Stengel waited until the Mets’ eighth game to get Bob L. Miller into the mix. They were 0-7 and when the manager turned to the righty, after which they were 0-8 and the righty was 0-1. The Mets didn’t have lefty Bob G. Miller to confuse matters until May. Bob G. Miller made no starts. Bob L. Miller made 21 starts in all, fourth-most among the 1962 Mets. He lost that first start and twelve games total that year, neglecting to win until the inaugural season’s final weekend, allowing him to take a 1-12 record to his next stop of Los Angeles, where the now-Dodger won ten games in 1963, thus giving Bob L. Miller every reason to tell the Mets, “It wasn’t me, it was you.”

Sometimes the pitcher who serves as your fifth starter of a given year is a gem yearning to be noticed.

• The 1997 Mets, at 1-3 on their pauseless opening West Coast swing, had nothing to lose when Bobby Valentine handed the ball to journeyman righty Rick Reed. Reed pitched seven scoreless innings and proceeded to install himself as invaluable to the starting rotation for a half-decade to come.

• The second-season Mets of August 1981 were six games deep into their reactivated schedule when they turned for fifth-starter purposes to a 27-year-old longtime minor league submariner who’d been promoted only after the strike. Thus began in earnest the major league career of Terry Leach, who’d rescue the Mets basically every fifth day six years later.

• The fifth starter of 1995 had to wait ten games for his first chance. What did Dave Mlicki do against the Reds on May 6 of this strike-delayed year? He did fine (though his bullpen blew a huge lead), but we don’t recognize Mlicki for how he started in 1995. We recognize Mlicki for how he started one night in 1997, throwing a shutout in the very first Subway Series game, and we don’t let him buy his own drinks for that very reason.

• Fifth starter Harry Parker didn’t get a look from Yogi Berra until the seventh game of 1973. Though his Met future would wind up in the bullpen, it was a good short-term future to begin, as Harry that day won the first of his eight games for the eventual National League champs.

• Unexpectedly deprived of Bill Pulsipher’s services, the 1996 Mets fished around for another starter before coming up with righty Mark Clark of Cleveland on the eve of the new season. The suddenly acquired fifth starter, used to start the campaign’s fifth game, Clark became Dallas Green’s most dependable arm from any direction in ’96, winning fourteen games and recording an ERA under 3.50, the only Met starter to keep his leading indicator so low.

• Mark Bomback had to wait until the dozenth game of 1980 to become Joe Torre’s fifth starter. When 1980 was over, Mark Bomback stood as Joe Torre’s only double-digit winner.

On the other hand, Bill Latham was the fifth starter used in 1985 (the sixth game); he’d have one win on the year and be gone by the next year. Aaron Laffey was the fifth starter used in 2013 (the seventh game); he’d have no decisions and be gone by the next month. Not every fifth starter story is uplifting. But at least Latham and Laffey were chosen before too long. You know who wasn’t? For that answer, we go to the extreme end of the “they won’t need a fifth starter until…” spectrum. It was 1975, the first of six times to date that the Mets went more than ten games before deciding they needed a fifth starter. Berra, as would anybody who could, leaned heavily on Seaver, Jon Matlack and Jerry Koosman. The power trio took fifteen of the season’s first eighteen starts. The three others went to rookie Randy Tate.

Not until the nineteenth game of the year did Yogi opt for a fifth starter, Hank Webb. Righty Webb was regularly talked up, certainly by unbiased Met source Bob Murphy, as a comer in the Seaver mode. His future proved a little more Tate-ish. Tate’s only season in the majors was ’75. Webb at least had sipped coffee during the three previous campaigns, but he didn’t make the Mets to stay until he was given the ball on May 3, 1975, or twenty-five days after Seaver got the season going. Hank etched versus the Expos what we now reflexively refer to as a quality start: seven innings pitched, two earned runs allowed. Pretty good for someone who wasn’t Tom Seaver. Not good enough for a win that day (Woodie Fryman one-hit the Mets), but good enough for Berra to remember Webb’s name. Yogi gave him seven starts total. Yogi’s successor, Roy McMillan, gave Hank eight more. The composite result was a respectable 7-6 record. Alas, under Joe Frazier, Webb was stashed in the bullpen before being sent back to Tidewater. The year after that, Webb was a Dodger for a spell, a Triple-A Albuquerque Duke for much longer.

Let’s go out on a more hopeful note, even if the 1987 Mets didn’t think they’d need hope. The defending world champions were planning to pick up where the 1986 Mets left off, particularly in their rotation. The 1986 Mets had starting pitching so strong that you’ll remember from above Rick Aguilera was deemed unneeded to start in the 1986 postseason. Ah, but just when you’re sure of something, something else come along. On April 1, 1987, less than a week before Opening Day, it was Dwight Gooden’s positive drug test. No, the fates were not kind to the 1987 Mets (save for the opportunity to go 11-1 fate furnished Leach), but at least the schedule gave them a break. Davey Johnson didn’t need a fifth starter until the eighteenth game of the year, and when he finally needed a fifth starter behind Ojeda, Darling, Fernandez and Aggie, he was able to call on merely the steal of the Spring, righthander David Cone. We got Coney in late March for Ed Hearn, and while we’d adored Hearn’s backing up of Gary Carter in 1986, we were told we were receiving in exchange for a caddying catcher a genuine prospect who’d make the pitching-rich Mets pitching-richer.

In his first major league start, against the Astros on April 27, 1987, young Cone lasted five innings and was charged with ten runs, seven earned. Hank Webb could have given Davey a better showing that night…and by then Hank hadn’t pitched professionally since 1979 (for the Miami Amigos of the Inter-American League, where his manager was the very same Johnson). Our hubris kept getting the best of us in 1987. That and everything else. It was a little much to expect this Cone kid to come out of almost nowhere and be the second coming of Gooden, Darling or anybody else.

Of course we know that one start every nineteen games wasn’t Cone’s destiny. By September, he’d be in the rotation full-time. In 1988, he’d win twenty games and be on his way to all kinds of accolades, not to mention a career that would carry into the twenty-first century, when much has changed about pitching. Yet we still check to see how long our team can go without turning to a fifth starter, even when we understand that someday that fifth starter might turn into David Cone.

by Greg Prince on 12 March 2021 4:38 pm On March 11, 2020, as the world was grinding to a halt, I tuned in for the final minutes of the Knicks and Hawks on MSG, essentially the last game in town. I sucked up every remaining bounce of the basketball, understanding that there was about to be no more action of its kind televised into my living room or any room for who knew how long.

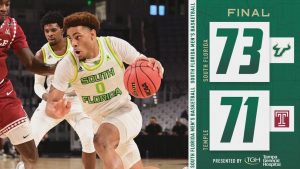

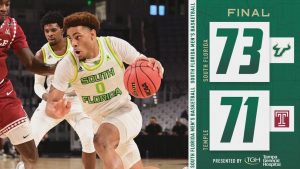

On March 11, 2021, as the world continued to come out of its COVID coma, I looked in on my alma mater, the University of South Florida Bulls, playing its first-round conference tournament game versus Temple. It was a noon start in front of an almost entirely empty arena. The setting was a public health precaution, though that’s also suggests my alma mater’s neutral-site crowd appeal. As for the early tipoff, the Bulls have to bull their way into prime time.

USF built a big lead it almost blew. This is roughly every other USF basketball game I’ve watched since graduating a very long time ago. The other half is USF not having a lead at all. That’s not entirely true, of course. I exaggerate because I root. Rooting is about being convinced your team will someday win but being more convinced that day isn’t today, or in this case, yesterday. But despite trying their damnedest to blow that big lead, the Bulls didn’t. They won by a bucket. I mean we won by a bucket. That’s my pronoun when it comes to my teams. I was pretty excited by the win, and then got back to concentrating on other things.

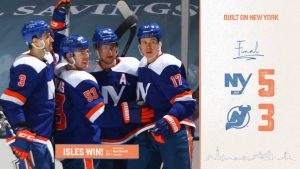

Later, after President Biden spoke to the nation about vaccinations gathering momentum and maybe our country accelerating its return to what we still consider normality, I tuned to the Islanders and Devils. I don’t think I’ve watched more than a few stray minutes of hockey since hockey decided it was safe to drop its pucks again, but I was curious to hear how Nassau Coliseum sounded with a thousand or so fans — health care professionals thanked for their service — reacting to professional sports, the first time the Uniondale barn opened a few of its front doors this season. It was a sound that a TV viewer dares to miss, as long as everybody in the building stays safely distant. Health care professionals probably didn’t need to be reminded to take care.

The Islanders were winning by four. Then they were winning by two, and I wondered what kind of horrible luck I was bringing them. Yet they held on, allowing them to raise their sticks to a chorus of YES-YES-YES-YES, which is the sweetest sound to come out of Long Island since Debbie Gibson first hit the charts.

I turned from the end of the Islanders to the conclusion of the Nets. I’ve been watching the Nets regularly if not religiously. That’s been the case since they moved back to geographic Long Island (OK, Brooklyn) in 2012. The Nets are enough a part of our winter nights that Stephanie knows from Ian Eagle, which is to say he’s not just some sports announcer to her often sports-indifferent ears. He’s part of our extended TV family the way Gary, Keith and Ron are, the way the Belchers from Bob’s Burgers are. The entire Nets telecast is. I’ve lately caught Stephanie blurting out “threeball!” and Googling Kevin Durant. When the NBA delayed its season, it didn’t occur to me to miss the NBA. The NBA is one of those things that seems to go on without the Nets as essential workers.

Ah, but the Nets of today are not the Nets I’ve stuck with never less than nominally since the demise of the ABA. The Nets of today are a superteam, in form and function. It’s shocking to me that when I watch them, I almost expect them to win, like I expected the Mets and Giants to win in 1986. I get nervous thinking like that. I still wait for every Nets lead to dissipate, but I’m doing it with less and less conviction. The Nets of Harden and Irving and, when he’s healthy, Durant, are not the Nets of impending doom, at least not to themselves necessarily. The Nets beat the Celtics going away.

Hopped up on sports satisfaction, I flipped to the final of the women’s conference tournament featuring my alma mater. The Lady Brahmans, as they were known in my day, were the No. 1 seed. They won the regular-season crown. It frankly surprised me that I was aware of this. It didn’t occur to me this happened only because UConn moved back to the Big East, but we’ll take it. USF built an enormous lead over archrival UCF, then went ice cold. This is the basketball I’m used to from the men’s team and the Nets. I tried not to descend into my usual lead-blowing snit. The more I watched, the more I saw college students who looked tired. Why were they playing so late at night, even in Central Time? Other than for television, I guess I just answered my own question.

The USF Bulls in women’s basketball are better than I’ve come to expect from USF Bulls in general. They didn’t fully blow their lead and they are now American Athletic Conference champions. This was one of those moments, like when the men’s team qualifies for the NIT or the USF football team wins a minor bowl game, I sort of want to don my green-and-gold hoodie, run into the street and celebrate in a socially distanced crowd, except nobody — nobody — in my New York suburbs, too far from Tampa geography ever seems to be watching USF. I’ve at least done the hoodie part while running errands after a big win, and nope, nothing. This makes sense, because USF’s big wins are way up the cable dial and USF is not anywhere around where I am. Hell, you wouldn’t find them in South Florida. There’s a reason they’re referred to as South Florida despite being located in the west central portion of their state, but it’s stupid, so I’ll skip it. I did see on social media that within their home region this victory was greeted under the umbrella of the #ChampaBay hashtag, which I have to say is even more stupid than the story behind South Florida not being in South Florida.

Oh, and the Mets won last night, in, as it happens, South Florida. It didn’t count, of course, and it wasn’t televised, and all I witnessed of it were tweeted clips of Jacob deGrom throwing an unhittable strike, Pete Alonso swatting a long home run and Albert Almora, Jr., making a difficult catch. Because this took place in West Palm Beach rather than Port St. Lucie, SNY was incapable of transmitting it. Perhaps they don’t have an extension cord long enough to reach down I-95.

Had it been televised, I might not have watched or thought about anything else. Had it been a regular-season affair, I might not have noticed anything else. It was just Spring Training, but it must be very effective training. Anything that readies deGrom, Alonso and everybody else for success, well, just keep doing that.

It was silly to feel sports-deprived a year ago. Once their absence sunk in, I can’t say I felt that way very much. The virus and how to avoid it was the only game in town. People staying alive was what mattered. Sports not being on TV was ancillary damage. When it trickled back in summer, it seemed unimportant to have it. Even when the Nets and Islanders played bubble playoffs. Even when the Mets played games that counted.

Yet here, last night, was sports again, not exactly in all its glory, surely not as it appeared more than a year ago, but it was entrenched in my life again, it was stoking my less harmful tribal instincts, it fulfilling my sense of identity and, I suppose, it was giving me something to be into and be happy about.

This afternoon, the Bulls had their next game in the men’s tournament. They built a big lead and blew it, losing by one. I was pretty pissed for about an hour. That’s also part of watching sports. Some days are better for having sports. Some days you forget that.

by Greg Prince on 9 March 2021 1:15 pm Here in one place, after ten years from more than eleven years ago and eleven installments, is Faith and Fear’s countdown of The Top 100 Mets of the 2000s, with links to each of the writeups. (An introduction to the series is available here).

Nos. 100-91

100. Luis Castillo

99. Fernando Nieve

98. Cory Sullivan

97. Roberto Alomar

96. Anderson Hernandez

95. Nelson Figueroa

94. David Cone

93. Shawn Estes

92. Eric Valent

91. Robinson Cancel

Nos. 90-81

90. Carlos Gomez

89. Nick Evans

88. Brian Stokes

87. Luis Ayala

86. Mark Guthrie

85. Kris Benson

84. Mo Vaughn

83. Esix Snead

82. Omir Santos

81. Fernando Tatis

Nos. 80-71

80. Jeff Francoeur

79. Ryan Church

78. Bubba Trammell

77. Angel Pagan

76. Dae-Sung Koo

75. Shawn Green

74. Jae Seo

73. Richard Hidalgo

72. Victor Diaz

71. Mike Jacobs

Nos. 70-61

70. Vance Wilson

69. Jason Phillips

68. Kaz Matsui

67. Damion Easley

66. Gary Sheffield

65. Bruce Chen

64. Lastings Milledge

63. Ramon Castro

62. Pat Mahomes

61. Darren Oliver

Nos. 60-51

60. Daniel Murphy

59. Timo Perez

58. Darryl Hamilton

57. Dennis Cook

56. Pedro Astacio

55. Kevin Appier

54. Ty Wigginton

53. Duaner Sanchez

52. Roberto Hernandez

51. Julio Franco

Nos. 50-41

50. Rey Ordoñez

49. Melvin Mora

48. Mike Bordick

47. Chris Woodward

46. Marlon Anderson

45. Rick White

44. Braden Looper

43. Mike Pelfrey

42. Desi Relaford

41. Moises Alou

Nos. 40-31

40. Derek Bell

39. Aaron Heilman

38. Todd Pratt

37. Orlando Hernandez

36. Tsuyoshi Shinjo

35. Oliver Perez

34. John Maine

33. Francisco Rodriguez

32. Mike Cameron

31. Xavier Nady

Nos. 30-21

30. Jose Valentin

29. Lenny Harris

28. Joe McEwing

27. Glendon Rusch

26. Bobby J. Jones

25. Pedro Feliciano

24. Turk Wendell

23. T#m Gl@v!ne

22. Mike Hampton

21. Jay Payton

Nos. 20-11

20. Robin Ventura

19. Todd Zeile

18. Paul Lo Duca

17. Billy Wagner

16. Cliff Floyd

15. Benny Agbayani

14. Rick Reed

13. Endy Chavez

12. John Franco

11. Armando Benitez

Nos. 10-3

10. Steve Trachsel

9. Johan Santana

8. Edgardo Alfonzo

7. Carlos Delgado

6. Pedro Martinez

5. Al Leiter

4. Carlos Beltran

3. Jose Reyes

Nos. 2-1

2. David Wright

1. Mike Piazza

by Greg Prince on 8 March 2021 3:29 pm Welcome to the final chapter of Faith and Fear’s historical countdown of the The Top 100 Mets of the 2000s. A full introduction to what we’ve been doing is available here. These are the more or less best Mets we rooted for as Mets fans during the decade FAFIF came to be. In honor of the 16th anniversary of our February 16, 2005, founding, we thought it would be fun (or at least not too painful) to revisit these guys and recall a little something about them.

Today, given our Mets of the 2000s at No. 2 and No. 1, we recall more than a little.

One era coming, one era going, two eras merging. 2. DAVID WRIGHT, 2004-2009

Also a Met from 2010-2016 & in 2018; missed 2017 due to injury; No. 2 Mets of the 2010s

1. MIKE PIAZZA, 2000-2005

Also a Met from 1998-1999

You can almost see an older David Wright, the version we settled in with during the 2010s, in the role of Randall “Pink” Floyd, quarterback and easygoing big man on campus at Lee High School in Texas in the spring of 1976 in Richard Linklater’s 1993 film Dazed and Confused. Everybody from every clique at Lee likes Randy. Nobody doesn’t like him. No wonder, especially when we see him take under his wing incoming freshman (and Tim Lincecum hairalike) Mitch Kramer. Kramer’s had a bad last day of eighth grade, absorbing the paddling that’s tradition in their neck of the woods from the high school juniors whose ascent to seniordom they mark by leaving marks on unlucky ninth-graders in waiting. When nobody else is around, Randy bucks up Mitch, letting him know, in so many words, that this is just how their high school world turns; that not every newly minted senior at Lee is a jerk; that Mitch is hardly the first freshman to absorb a licking; and that if he acts as if none of the paddling of the swollen ass with paddles bothers him, everything will soon be swell.

“Put some ice on it,” QB1 advises. “After that, there’s nothing a few beers won’t take care of.” Why, Randy himself suffered a freshman beating he recalls as “vicious. Had some pretty cool seniors, though. Like, they’d beat the hell out of you and then get you drunk, that sort of thing.”

In his 2020 memoir The Captain, co-written with Anthony DiComo, Wright lets us know that when he was promoted to the Mets in July 2004, he had some pretty cool seniors. Never mind that he’d been a first-round draft pick (compensation in 2001 for Mike Hampton’s free agent departure to Colorado) nor that he’d just been showcased in MLB’s Futures Game. Mets fans couldn’t wait to step (W)right up and greet their projected next savior from Triple-A, who was clearly on the fast track after tearing up Double-A that same season, batting a combined .341 between Binghamton and Norfolk. Wright, 21, intrinsically knew better than to put any stock in his reputation preceding him to New York. In the high school hierarchy of big league baseball, he was just another frosh: Dave and confused. He admits he didn’t have a clue regarding “what to wear, how to behave, how not to embarrass myself.

“Luckily, the clubhouse had a significant veteran presence to help me figure it all out.”

For a team keen to build around Wright and 2003’s similarly hyped callup Jose Reyes, the 2004 Mets, particularly when things weren’t going swimmingly, could have been mistaken as a storehouse for museum pieces. Cool seniors? Seniors for sure. Sixteen different Mets who played for the club the same year David came up were in at least their tenth major league season. A few had cycled out before his July 21 arrival, but the third base prospect wasn’t kidding about a significant veteran presence. Five of the teammates he joined were in the midst of careers that dated to the 1980s. Eldest statesman John Franco had thrown his first major league pitch twenty years earlier. He’d been around so long that he’d twice faced his current manager, 57-year-old Art Howe.

David couldn’t have been more nervous or, in his wide-eyed way, any happier to learn from so many upper classmen. Joe McEwing (a relative neophyte as Met vets went, with a mere seven or so years of service time) took Wright to Foley’s in Manhattan to celebrate his first game in Queens and then bought him “a nice pair of shoes”. Cliff Floyd footed the bill for the rookie’s suits. They did more than feed and clothe him. They told him how to be in his new surroundings. Franco was quicker with advice than he was with a fastball by then. T#m Gl@v!ne pulled him aside to tell him “you get it,” which David took to mean, “I was respectful to both the clubhouse veterans and the game itself.”

David Wright was already being written up in the New York papers as the future face of a perpetually beleaguered franchise, a status that meant everything to those of us in Mezzanine if not so much in that clubhouse. Looking out for him was all well, good and heartwarming, but he wasn’t exempt from rookie hazing. No paddles. Nothing unseemly (at least not as recorded in his book), but stuff designed to let him know a freshman, no matter how highly he’s touted, is still a freshman. David lapped it up: “I tried to show the guys that I could be one of them — that they could rib me or try to embarrass me, and I could take it all in stride.” The institutionalized teasing included a vet-sanctioned decree that the rook take the mic in the bus and at karaoke bars on road trips and sing, à la Alan Alda as George Plimpton in Paper Lion or the new driver in those old Schaefer Beer commercials.

It was all in good fun, but that didn’t make it any less intimidating. Mike Piazza always sat in the first seat with his big, hulking frame, meaning I’d have to brush his shoulder to get by him. As I sang, he would stare at me with that Piazza scowl I was used to seeing on television.

The words coming out of my mouth might have been Whitney Houston lyrics, but inside, I was thinking: Man, I’m serenading Mike Piazza right now.

Mike Piazza’s shoulders represented a broad boulevard for David Wright to traverse. In the book, David recalls spying Mike “sitting alone at his locker, staring at the ground with a dejected look on his face”. Perhaps with his karaoke performances in mind, David attempted to channel Paul McCartney — take a sad Mike and make it better. Lightheartedly, David began to massage the superstar’s shoulders, cajoling him to tell him, jock to jock, what was bothering him.

“Mike, you all right, buddy?”

“Mike, what’s wrong?”

“Mike, everything okay?”

The popular rookie found the one veteran apparently immune to his innocent charms, admitting, “I was just a happy-go-lucky twenty-one-year-old pestering Mike Piazza, when all he wanted was a few minutes of alone time. Looking back, I’m just fortunate he didn’t punch me in the face.”

***Though our well-honed Met instinct reflexively places them in eras discrete from one another — each inherently attached to different dramas, different triumphs and different heartbreaks — two within the small handful of position players with a claim on having been the greatest in franchise history overlapped, and they did it right in our lap right here. The 2004 Mets who had featured Mike Piazza in his seventh Queens season, fourteenth overall, and David Wright for a little more than two months were the Mets who unwittingly served as the precursor chemical for the blog you’re reading today. Of course Piazza was an instigator of Mets fandom in so many ways from May 23, 1998, forward, so why not this online chronicle, founded on February 16, 2005, and continuing at this address sixteen springs later? I doubt there’s a Faith and Fear without the Bobby Valentine years. I doubt there’s enduring reverence for the Bobby Valentine years without Mike Piazza.

By 2004, the Bobby Valentine years and their endless sense of urgency were two years behind us, replaced by the Art Howe interregnum, the tepid nature of which suggests maybe you shouldn’t always name eras for managers. By 2004, as much as one could sit and rue the passing of better years (a recurring pastime for me in the days of Howe), the Mets fan who was determined to keep going as a Mets fan looked ahead as much as he looked behind. Foremost, we collectively looked to David Wright, a bright young face added to the aging Mets roster that July like a crisp twenty direct from the ATM into your wallet of wrinkled ones.

The record shows David Wright of the immediate and distant future and Mike Piazza mostly of the rapidly receding past started in the same Met lineup 134 times in 2004 and 2005. Six times they homered in the same game. Mike and David weren’t exactly ships that passed in the Met night. A season-and-a-half on the same roster, in the same clubhouse, sharing more than a hundred box scores is not a cup of coffee. It’s at least a couple of thermoses’ worth. You’d think it would be good for a platonic shoulder rub between consenting workplace proximity associates.

We came into this series, The Top 100 Mets of the 2000s, to commemorate the spot in franchise history where we as Faith and Fear came along. Half of the 2000s were done. Half of the 2000s awaited us. There was a little Piazza in our immediate future. There was a load of Wright to come, in the decade already in progress and the one after that. For a moment, as we began, they were together.

Mike’s team.

David’s team.

Our team.

***The same All-Star festivities that included David at the Futures Game also encompassed Mike starting for the National League, catching Roger Clemens (!) at Minute Maid Park. Within a week of the midsummer break ending, the future was clubhousing alongside the present, the latter of whom was slipping inexorably into the Met past. If Piazza was given to moments seeking splendid isolation, you couldn’t blame him. He was elected NL catcher by the fans that year — he’d broken the record for most home runs by a backstop in May — but the management of the franchise he’d been fronting since 1998 had decided he was a first baseman. Neither Mike’s body nor soul was fully on board with the decision.

He tried. He always tried. Lest you forget, Mike Piazza was a 62nd-round draft choice who made himself into the greatest hitter who ever caught, and a catcher of whom he didn’t wish it said was behind the plate solely for his bat. You know who could tell you how hard Mike Piazza worked to remain a viable major league catcher long past the point anybody was going to question his place in the game? David Wright. On the Amazin’ But True podcast last July, David recalled for Jake Brown and Nelson Figueroa that at nineteen in Port St. Lucie, while he was doing his required early-morning work on the minor league side of camp during his very first Spring Training, “I look over, on one of the fields that the major league team used, and Mike Piazza is out there. He’s already solidified himself as probably the greatest-hitting catcher of all time, Hall of Famer, icon, and he’s back there working on his catching and his throwing at like 7:30 in the morning. It just opened my eyes up to, not only is this guy one of the best to ever do it, but he’s constantly working, even though he’s got this résumé.”