The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 18 August 2020 7:29 pm Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

One day in the spring of 1987, I chatted on the phone with my mom.

This wasn’t noteworthy — I was a senior in boarding school, and in the era before cellphones we’d take turns cramming into the cubby that held our dorm’s lone pay phone to check in with parents. But this time my mom had a story to tell me.

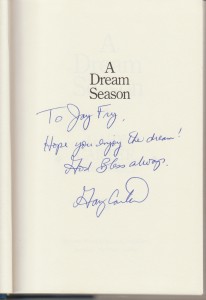

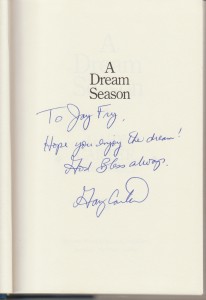

Gary Carter’s book about the ’86 championship, A Dream Season, had just hit stores. She’d heard that Carter would be at Haslam’s Book Store in central St. Petersburg, Fla., and driven over to get me a signed copy. St. Petersburg had been the Mets’ spring-training home since their birth in 1962, and so the town had a certain affection for the team. Knowing this, my mom left plenty of time to wait in the long line she expected.

But there was no line. While St. Petersburg has since become a reasonably interesting town (with its own major-league team, at least for now), back then it was still disparaged — sometimes affectionately, sometimes not — as God’s waiting room. Haslam’s was in the middle of nowhere, the afternoon was hot, and not even the presence of the All-Star catcher of the World Champions of baseball was enough to draw a crowd. There was just Gary Carter, looking bored and a little wan.

My mom felt sorry for him, and so she stayed and chatted for a while — about the Mets and their season (she has always been a huge fan), but also about her sometimes wayward son and his writing ambitions and where he might go to college the next fall.

As this story unfolded over the phone, I had two reactions:

1. Oh God, mom, you didn’t.

2. Please don’t let this story end with another rich athlete being curt or dismissive with a fan. Not when the athlete is Gary Carter and the fan is my mom. Because that really might break my heart.

Of course I had nothing to worry about. Carter couldn’t have been kinder. He signed my book — To Jay Fry, Hope you enjoy the dream! God bless always, Gary Carter — and my mom left, a fan who’d met a baseball hero and come away thinking better of him. Of course I had nothing to worry about. Carter couldn’t have been kinder. He signed my book — To Jay Fry, Hope you enjoy the dream! God bless always, Gary Carter — and my mom left, a fan who’d met a baseball hero and come away thinking better of him.

I remembered that conversation in February 2012, when I heard Carter had died after a yearlong battle with brain cancer. My son Joshua was nine years old, and after I picked him up at school I gave him the news and we talked about Carter on the walk home. Our family had spent that offseason watching Ken Burns’s Baseball, which had led to conversations about athletes, and how it was both tempting and unfair to take their successes or failures on the field and turn them into judgments of them as people. What I was trying to get across was that most athletes, like most people, were neither heroes nor villains, and our stories about them were too simple. We’d talked about Ty Cobb and the horrible things he’d done, but also about how Cobb had been damaged by a cruel and horrifying childhood. And we’d discussed how Barry Bonds could be a cheater and a superstar and a jerk and a sad, even tragic figure all at the same time. I suppose it was my version of editor Stanley Woodward’s famous advice to the great Red Smith: “Don’t god up the players.”

Given all that, as we walked home in the dark it was a relief to be able to talk about Gary Carter. It was a relief to be able to tell my son that I’d never heard anyone speak ill of him as a teammate, husband, father or friend. It was a relief to say that he was by all accounts something simple to describe and unfortunately easy to mock, probably because it’s so hard to achieve: a good man. Not because of what he’d done behind the plate or at bat, but because of how he’d lived his life and how he’d treated others.

Carter was more complex than that, of course. His relentlessly sunny enthusiasm came with a whiff of self-aggrandizement, and he was embarrassingly wrong-footed about politics, with a bad habit of campaigning for managerial jobs that were yet to be vacated. I didn’t talk about that with my nine-year-old, but if I had, I would have said those things didn’t make Carter a bad person, just human. All of our obituaries, if fairly told, will include a but here and a to be sure there and a few things we would have preferred struck from the record.

In the days after Carter’s death, the memories from his teammates were heart-breaking — and raw in a way I’d rarely if ever heard from pro ballplayers. Keith Hernandez — Goofus to Carter’s Gallant, as saluted in our previous A Met For All Seasons, responded with grief so raw that listening to it made me feel like an intruder. But the words that really got me came from a sadder, wiser Darryl Strawberry: “I wish I could have lived my life like Gary Carter.”

That life began in 1954 in Culver City, Calif. Carter grew up a quintessential California kid, a star quarterback and outfielder at Fullerton’s Sunny Hills High. He signed a letter of intent to go to UCLA, where the Bruins wanted him as a QB, but opted to sign with the Montreal Expos after they selected him in the third round of the 1972 draft. The Expos turned him into a catcher, though he also played right field early in his career, and gave him a September callup in 1974. He made his debut against the Mets in the second game of a Sept. 16 doubleheader, grounding out in his first at-bat against Randy Sterling. Carter went 0-for-4 that day, but collected his first hit two days later, a pinch-hit single off Jon Matlack. He kept going from there, hitting .407 in his September cameo and becoming a National League All-Star the next season, the first of 11 such honors.

He was beloved by fans in Montreal, but not by his teammates. They resented his rapport with the media, his ever-present smile and his gift of gab. They made fun of his faith — which he’d discovered with the help of Expo teammate John Boccabella, and never shied from expressing. They sneeringly called him Teeth, and Camera. Even the nickname that stuck, “Kid,” was a put-down, bestowed after Carter had the temerity to run hard in spring-training drills. As Pete Rose had done with the derisive tag “Charlie Hustle,” Carter embraced the insult and turned it into a positive.

In the 1984 offseason, the Expos’ ownership tired of Carter and his big salary and traded him to the Mets for Hubie Brooks, Mike Fitzgerald, Floyd Youmans and Herm Winningham. The Mets were young and exciting but a work in progress, having run out of gas trying to catch the Cubs the year before. Carter was the missing piece they needed — a potent bat in the middle of the order and a mentor behind the plate. He was a brick wall in home-plate collisions, a masterful pitch framer before the concept existed, and a skilled pitcher whisperer when needed.

The view from Cloud Ten His impact was immediate. Introduced to the press, he noted that his right ring finger was reserved for the World Series ring he intended to win with the Mets, which must have driven his detractors in Montreal crazy. On Opening Day, he bashed a 10th-inning homer off Neil Allen to give the Mets a 6-5 win over the Cardinals, and all but invented the curtain call with his jubilant fists-raised celebration. (They hated that in Montreal too — in time they’d hate it all around the National League.)

The Mets would fall just shy of the Cardinals in ’85, but the next year they made good on Davey Johnson‘s promise that “by God, nothing is going to stop us.” Carter was front and center, of course — in the playoffs, he was mired in a seemingly unbreakable slump, and suffered the indignity of Astros reliever Charlie Kerfeld showing him the ball he’d just grounded back to the mound in yet another big spot. Three days later, in the 12th inning, Astros manager Hal Lanier walked Hernandez with one out and the winning run on second to let Kerfeld face Carter and his 1-for-21 streak. Carter lashed a ball up the middle, nearly undressing Kerfeld, to bring home Wally Backman and win the game. As Kerfeld stalked off the mound to stew about it, Carter celebrated by hugging every teammate in range, then threw his arms skyward like Atlas holding up our baseball world. Up in Massachusetts, I was certain I’d just seen a modern-day parable, a lesson that hard work and self-confidence would be rewarded.

In some other, lesser universe, Carter made the last out of the 1986 World Series, ending a meek 1-2-3 inning against Calvin Schiraldi and the Red Sox. But in this universe, he stroked Schiraldi’s fourth pitch into left for a single. Carter was so averse to profanity that he’s sometimes said to have coined the term “f-bomb,” but according to legend he arrived at first base and told coach Bill Robinson that “I’ll be damned if I’m gonna make the last fuckin’ out in this fuckin’ World Series,” a story I simultaneously don’t believe and find delightful. A few improbable minutes later the Mets had won Game 6; two days later, Carter had that ring he’d vowed to wear.

The next year, the mileage started to catch up with him — and 1988, the year he represents in our series, was a slog, with Carter laboring through a three-month pursuit of his 300th homer, a milestone that became a millstone. My last memory of him from ’88 was him dourly packing his catching gear amid the wreckage of Game 7 against the Dodgers, the smile for once stripped from his face. In ’89 he stumbled to a .183 average and in the offseason the unimaginable happened: The Mets released him. He’d play for the Giants and the Dodgers, then return to Montreal for a last go-round, one that let the frustration of his autumn seasons dissipate and drift away. His final at-bat, on Sept. 27, 1992, was baseball perfection — a double just over the head of Andre Dawson, once one of his chief underminers in the Expos’ clubhouse. It drove in Larry Walker with what proved to be the winning run; the standing ovation almost brought down Olympic Stadium.

In the last A Met For All Seasons I posited that there are Gary people and Keith people, and declared that I’m a Keith person. Which I am. But you can declare for the one without diminishing the other. I was naturally drawn to Keith’s ferocity and brains and, OK, the fact that he succeeded despite a long list of flaws and foibles. But I also beamed in response to Gary’s buoyant curtain calls, and I admired his bedrock stoicism, crouching behind the plate night after night in pain and dust.

Carter’s Met teammates rolled their eyes at his faith, but I always sensed that what rankled them most wasn’t his unshakeable faith in a higher power, but his unshakeable faith in himself — and how that compared with their own doubts and shadows. The other Mets respected him to a man, but few of them seemed to like him. But by the time Carter died, something had changed. The remorse his teammates shared was genuine — in finding themselves older and grayer and thicker, they’d come to think differently of square, uncool Gary Carter from California.

I’d never so much as met him, but my feelings had changed too. As I’d grown older and grayer and thicker myself, I’d learned that the person you show yourself to be in dealing with others is the person you really are, and how you’ll be remembered. Living your life like Gary Carter? We should all have such courage of our convictions.

Twenty-five years before he died, Gary Carter was kind to my mother. It was a little thing, but most of our lives are little things, and we determine whether they’re done well or poorly, graciously or indifferently. He wrote God bless always in a book for me, but he was a blessing in his own right. That was true on the field, at a time when baseball meant everything to me, and in time it was true off the field as well. He was a blessing, for me and so many others. His memory still is.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1986: Keith Hernandez

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2019: Dom Smith

by Jason Fry on 18 August 2020 2:09 am A laugher is always welcome as a team trudges through the long march of a baseball season — and, as it turns out, as it sprints through an unexpectedly curtailed one. And a laugher is particularly welcome when that team has recently made you wonder if it will ever play sound baseball again.

The Mets, after being stomped by the Philadelphia Phillies over a lost long weekend, arrived in Miami to play the jury-rigged Marlins, which is my least favorite part of any season. The Marlins are annoying in teal and in barfed-up neon and while wearing home uniforms that inexplicably say MIAMI. They’re annoying in converted football stadiums and when playing under a giant Pachinko machine and when playing in front of nobody in a weirdly silent cavern. They’re annoying when Wayne Huizenga is involved and when Jeffrey Loria is involved and when Derek Jeter is involved. They’re annoying because whatever the specifics, they’re dependably tasteless and tacky and nihilistic and misbegotten and, also, because no matter how rickety and low-rent their current incarnation, they give the Mets fits.

Not Monday night, though. Oh, it didn’t start well — Robert Gsellman looked rusty and ran out of gas in the second, leaving the Mets’ bullpen needing to get 22 outs. But then the Mets got to hitting, in ways that have been in distressingly short supply this year. That was Robinson Cano hitting two balls out, the second an absolute missile into the second deck. And yes, that was Pete Alonso having a big day at the plate, complete with two homers of his own. It’s too early to declare the Polar Bear off the endangered sluggers’ list, not with the frustrating year he’s having, but it was gratifying to see him looking like he was actually enjoying himself out there.

We all were, as the Mets socially distanced themselves from the Marlins on the scoreboard — well, unless you wanted a crisply played game that showcased the beauty of the baseball. If you showed up expecting that, sorry — there was a lot of dopey baserunning, questionable use of challenges and Mark Wegner serving as MLB’s latest walking advertisement for Robot Umps Now. And the game was a dreary slog, finally ending on the wrong side of the four-hour mark when a weary Franklyn Kilome got Jonathan Villar to lift a fly ball to mercifully fieldable right.

Kilome didn’t pitch particularly well but did yeoman duty in sparing the bullpen further harm, if you don’t count Seth Lugo having to warm up. (I bet Lugo would say that counts.) Kilome got the save; Chasen Shreve got the well-deserved win for saving the collective blue and orange bacon by capably relieving Gsellman. Meanwhile, the Marlins were a mess, culminating with poor Logan Forsythe pressed into duty to throw Guillormesque gas in the ninth. (Forsythe didn’t fare as well, surrendering a run.)

The Mets are … an odd club. The starting pitching we figured would be their strength not so long ago has been shredded, but the bullpen looks improved, there are actual defenders available for infield work, and the hitters have been unlucky enough that a simple regression toward the mean ought to bring better results. It would be odd if the Mets slipped into the lower ranks of the playoffs because of their bullpen arms instead of those of their starters. But everything’s odd this year, isn’t it? Why not hope a little oddness could actually be a good thing?

A reminder: Share your tale of Game Six!

by Greg Prince on 17 August 2020 12:49 pm A blink ahead of midnight on October 25, 1986, the lights nearly went out on the New York Mets’ quest for their second world championship, as Dave Henderson launched a home run that clanked off the Newsday sign above the extreme left field fence at Shea Stadium. It was the top of the tenth inning of the sixth game of the World Series. The score was suddenly Red Sox 4 Mets 3. Within the first few minutes of October 26, the Red Sox would add another run to their lead. Given that Boston was ahead three games to two, and the World Series was a best-of-seven affair, you might say darkness was upon us.

Wally Backman led off for the Mets in the bottom of the tenth. You could always count on Wally, yet he popped out.

Keith Hernandez was up next. You could always count on Keith, yet he flied out.

If you couldn’t count on Wally and you couldn’t count on Keith, what could you count on? The Red Sox were up, 5-3. There were two outs. Dark didn’t begin to describe the Metsian mood. The entire epic season of 108 exhilarating wins, a searing NLCS triumph, and the delightfully atonal “Get Metsmerized” record were about to be consigned to the “nice try” ash heap of history. Despite what George Foster had rapped in April, the Mets were not going to qualify as “better than the Red Machine” if they couldn’t make the clock stop, keep the darkness from blanketing the end of 1986 forevermore and, you know, score at least two runs, preferably three.

Just as we reached that unthinkable interval when even the most faithful of fans might have crossed a toe across the border into the land of Giving Up (ahem), Gary Carter singled. Then Kevin Mitchell singled. Then Ray Knight singled, scoring Carter and sending Mitchell to third. Then, with Mookie Wilson batting, Bob Stanley uncorked a wild pitch, allowing Mitchell to race home and Knight to rush to second.

Wilson continued batting. One pitch after another. A plethora of foul balls. A tie in place. Nothing assured.

Then Wilson made contact, producing the slightest of ground balls heading up the first base line.

This is where you come in.

There would be half as many pennants in this corner of my office had it not been for one particular tenth inning. If you were a sentient Mets fan in the first hour of October 26, 1986 (and an anecdotal interpretation of our blog’s demographics suggests that you were), you are invited to tell your story regarding Mookie Wilson, Bill Buckner and the outcome of Game Six. Extending the invitation is Nick Davis, director of the upcoming 30 for 30 multipart documentary commemorating the 35th anniversary of the 1986 World Champion New York Mets and a deep dive into the city and era they so deeply defined. Nick is a Friend of FAFIF, and I can vouch for the dedication he and his crew are putting into this project.

So here’s what Nick is asking:

1) Remember where you were, what you went through, how you felt, how you still feel.

2) Film yourself telling your distinct Tenth Inning Story on a smartphone or laptop, with the camera positioned horizontally, a.k.a. “landscape” mode. Keep the camera steady, keep background noise to a minimum, choose a simple background (avoid windows) and get yourself close to the camera. The Mets were the stars of that Series, but you, after all, are the star of your story.

3) Include everything you remember about the moment and use all the colorful language you consider appropriate. It was an emotional episode. Feel free to let it out.

4) The briefer the better. Three to four minutes to tell your tale, tops.

5) Send the video you’ve created to 86MetsFilm@itv.com. From there, it will be considered for inclusion in a film likely to be a touchstone for baseball and cultural scholars for decades to come. Or at least get downloaded, streamed and repeated a lot.

Nick can answer any other questions you have at the above e-mail address.

“We’ve got the teamwork to make the dream work,” all the Mets (other than erstwhile teammate George Foster) insisted in August of 1986. Be part of the team here and share how the Mets at least once in your life helped make your dream come true.

by Greg Prince on 16 August 2020 5:29 pm I’ve had one conversation with Zack Wheeler in my life. It came after his rookie season, two years after the Giants had traded him to the Mets for two months of Carlos Beltran. When I asked him about that July 2013 game — seven three-hit innings, one run allowed, plus his first double and RBI en route to a fairly easy win over San Francisco — he didn’t mask his spiteful glee from having reminded them who they gave up on when he was merely a minor leaguer. Zack smiled and told me he really wanted to “shove it against ’em”.

I never forgot that remark and I surely remembered it Sunday afternoon. If I were the type to bet on baseball, there’s no way I wouldn’t have put whatever I had available on Zack to keep on shovin’ against teams he used to pitch for.

Wheeler left the Mets as a free agent following the 2019 season. Brodie Van Wagenen and the ownership he represents didn’t exactly try to block the door with any kind of competitive offer. The Phillies lured Zack with a lot of years and a ton of money. It was a sensible deal to make only if you like knowing you’re likely to have a very good starting pitcher on your ballclub for something resembling the long haul.

The Mets, at the moment, are down in the starting pitcher category. Health, slumps, career arcs…none of it suggests a rotation that Wheeler would have trouble cracking let alone helming at this precise moment. Most of whatever the Mets had going for them entering Sunday — on-base streaks for Brandon Nimmo and Michael Conforto, a home run streak for Dom Smith, encouraging outings after rough first innings for Rick Porcello — all opted for a day of rest. Nimmo and Conforto neither hit nor walked or took one for the team. Smith stayed in the yard. Porcello had his usual first-inning stumble (in five first innings this season, Rick is pitching to an ERA of 12.60), seemed to recover (his second-inning ERA is down to 1.80), but eventually got tagged for four earned runs on ten hits in six innings, the tipping-point blow coming from Andrew McCutchen via a tie-breaking two-run homer (Rick’s ERA in all innings currently stands at 5.76).

A couple more runs crossed the Citizens Bank Park plate to give the Phillies six in all. Six on Friday. Six on Saturday. Six on Sunday. That’s 6-6-6 in case you were playing the numbers. Throw in an extra 6 for the quantity of hits the devilishly effective Wheeler scattered over seven innings in the 6-2 Mets loss, and you can draw your own satanic conclusions

by Greg Prince on 16 August 2020 12:58 am In the bottom of the eighth Saturday night, with the Phillies leading by more runs than were worth counting, the Mets employed an extreme shift against Didi Gregorius that sort of worked and sort of didn’t. It sort of did because third baseman J.D. Davis, stationed in right field, fielded the ground ball Gregorius pushed through the infield. It sort of didn’t because Gregorius beat Davis’s throw to Pete Alonso from what amounted to medium right field.

Yeah, I guess it didn’t work.

As SNY ran a couple of replays, Hernandez criticized Davis (or whoever directed Davis to set up where he did) for playing far too deep to get a runner as speedy as Gregorius, which was a reasonable point. Keith then raised an intriguing question, if not necessarily one that could be addressed through defensive heat maps: was what Gregorius just achieved an infield hit? It was, after all, handled by an infielder who threw it to the first baseman a shade late for what would have been scored a 5-3 force. If a batter beats out a would-be 5-3 force, that, intuitively speaking, gets marked an infield hit in ol’ Henry Chadwick’s scorebook.

The MLB app’s play-by-play summary described the action as “Didi Gregorius singles on a ground ball to third baseman J.D. Davis.” Over on the ESPN app’s version of what happened, “Gregorius singled to shallow right” was the call. I’ll have to see what Baseball-Reference has to say in the morning*. According to B-R, Gregorius entered Saturday night’s game with two infield hits for 2020. If his total is twice that when his splits are updated (he had an infield hit in the fifth), we’ll have further evidence that a ball to an infielder standing undeniably in the outfield isn’t exactly what it appears…whatever it appears to be, since I suppose an observer could make a case for either. It was hit into the outfield, but it was hit to an infielder. In the age of the shiftiest of shifts, the intrigue is positioned here and there.

*Sunday morning update: Didi Gregorius is indeed now listed by Baseball-Reference as having four infield hits for 2020, with his eighth-inning at-bat noted as producing a “Single to 3B (Ground Ball)”.

Two pitches into the next Phillie at-bat, Phil Gosselin grounded to Luis Guillorme for the third out of the inning, and the production had to move into commercial, compelling Gary Cohen to follow in the best tradition of Jesse Jackson and rule Keith’s question “moot”. The Mets would come up in the top of the ninth at Citizens Bank Park down, 6-0. Dom Smith would homer for a fourth straight game to make the matter at hand a modestly more appealing/less appalling 6-2. That’s how it ended, with a final that made the game appear closer than it really was.

From the first until the middle of the fifth inning, the game was legitimately close, with Long Island’s Own Steven Matz having dueled Aaron Nola to almost a standstill. Nola had given up nothing but baserunners Met batters couldn’t drive in. Matz had allowed only a solo homer to Jean Segura. What an encouraging progression from the recent Matz habit of falling behind early and plummeting precipitously from there.

Ah, but in the bottom of the fifth the game stopped being as close as it could possibly appear and grew sadly distant. Matz’s inventory of offense-facilitation included a hit; another hit; a walk; a lineout; a bases-loaded walk to Andrew McCutchen; a very deep bases-clearing right-field double to Rhys Hoskins (where no infielder or outfielder could have wrangled it); and another double somewhere in right to Bryce Harper. Presto, it was Phillies 6 Matz 0, Jeurys Familia on his way in from the bullpen. Steven’s ERA now stands at 9.00, but nobody’s better at getting first dibs on the hot water the nights he pitches.

LIOSM appeared equal parts dejected and frustrated through the filter of postgame Zoom, which couldn’t help but elicit empathy for a familiar fella whose difficulties have been more than virtual. “I really do think I improved a lot on my stuff today, commanding the ball,” Matz said, which sounds encouraging coming from a professional who knows more about pitching than you the home audience ever will. “Good pitches” got hit. “Hard-fought” at-bats became bases on balls. Yet once your starter has given up five runs in an inning and your team is not assisted by the other starter giving up any at all, it’s Moot City, whether the game is being telecast from Philadelphia, announced from Flushing, or both. This entire Mets season, at 9-13, has a moot vibe at present. That is, “deprived of practical significance,” for you devotees of “the dictionary defines moot as …”

In practical terms, Gregorius reached first base in the eighth. In practical terms, Dellin Betances left him on first base. In practical terms, neither mattered much because Matz buried the Mets three innings earlier and, Smith’s power surge notwithstanding, the Mets were not coming back. In practical terms, a crummy Steven Matz, layered atop a sore-necked Jacob deGrom, an unstretched Robert Gsellman and whatever other uncertainties circle the rotation next, figures to doom the Mets in a season that isn’t far from over despite having only recently begun. But practical terms don’t really seem all that relevant to a season that pleads not to be taken seriously, even in the realm of the fun and games sports ought to be providing in These Challenging Times.

The Mets are in a virtual tie for last place? Weren’t they just more or less lined up to make the playoffs a couple of nights ago? They were. Maybe they’ll be again in a couple of days. Or not. The Cardinals are back on the field after quarantining for more than two weeks. The Reds are now off it for the same reason the Cardinals were absent. This is not a season to be grabbed by the shoulders, shaken purposefully and told to get real before it’s too late. This is barely a season in any sense of the word except someone said it is and therefore we are conditioned to tune in and treat it as one.

Treat it as you will. Contemplate the philosophical puzzles about trees falling in right field forests and being cleared away by wayward third basemen rather than stress over what’s wrong with Steven Matz if that’s your jam. If the Mets go nowhere, as they appear headed, chalk it up to all of these games being played under shaky, shady circumstances and help yourself to a large bowl of mulligan stew for 2021, knock wood. If Matz gets it together; if Smith keeps smoking; if deGrom can turn to his left and right without debilitating discomfort; if the Mets win three in a row for the first time since the last decade, go with that and call it a roll, a race, a ride, whatever you like. Believe me, I’ll be right there with you (well, six feet from you) in October should we somehow get a crack at a 61st game and then some.

For now, from here, the whole 2020 deal strikes me as moot, save for the parts we choose to define as better than nothing.

by Jason Fry on 14 August 2020 11:15 pm The Phillies played the first half of Friday night’s game like they were recreating a Benny Hill skit. The Mets once again showed resilience, losing a lead and promptly regaining it on back-to-back homers. Luis Guillorme continued to reward the Mets for finally giving him playing time. Walker Lockett — summoned when Jacob deGrom was scratched with neck stiffness — pitched pretty well all concerned, with the glaring exception of one pitch to J.T. Realmuto, the wrong guy to make a mistake to in 2020.

It all went for naught, thanks to two moments where events were poised on a knife’s edge and then came down against the Mets.

In the sixth, with two outs and runners on first and second, Pete Alonso slammed a first-pitch fastball from Blake Parker. The ball sailed on an arc towards center, the deepest part of a not particularly deep park. Gone, I thought. So did Pete. It wasn’t gone. Roman Quinn snagged it just short of the fence. The Phillie fan cutouts kept smiling their cardboard smiles. Inning over.

In the ninth, Seth Lugo got into immediate trouble, surrendering singles to Quinn and Andrew McCutchen. But he fanned Rhys Hoskins and battled Bryce Harper, saddling him with an 0-2 count. His fourth pitch was a slider, low and on the inside edge of the plate. Harper smacked it into right field just in front of Michael Conforto, who fired a perfect strike to Wilson Ramos. Ramos caught it ahead of the plate, slung his hand back, and tagged Quinn’s fingers — about a second and a half after those fingers touched the plate. Ballgame.

There was more than that, of course. There was Billy Hamilton stealing second, then being far too aggressive in trying to advance to third, getting gunned down by an alert Didi Gregorius. There was the parade of Mets leadoff hitters who never came home, despite the Mets being loose in the Phillies’ normally less than dominating bullpen.

It stinks. But then, if you didn’t know baseball was an unfair game by now, I’m not sure what to tell you. It’s cruel and unfair and sometimes darkly comical, with virtue often going unrewarded and sloppiness often going unpunished.

It’s not much comfort, but I suspect this is the type of game that bothers fans more than players. By the time they’re big leaguers, players have been on the short end of such games dozens of times, if not hundreds. They get good at having short memories, at cultivating the ability to wash games like this one away and start anew.

We’re not so good at that. We look back at Alonso’s drive coming up short and Hamilton being too aggressive and Ramos being a touch too slow and we mutter and grumble — and then we look ahead to homer-prone Steven Matz vs. Aaron Nola in a teeny ballpark, and we mutter and grumble some more.

Wash it away. Start anew. If you can. Good luck.

by Jason Fry on 14 August 2020 10:35 am Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

The 1986 Mets laid waste to the National League, closed bars, got arrested, wrecked planes, raised a prodigious amount of hell and opponents’ ire, got into fights, won most of those fights, defeated the Houston Astros in a harrowing six-game series, then defeated the Boston Red Sox in an even more harrowing seven-game set.

It’s annoyingly hard to remember, now that New York is infested by hedge-fund bros with corporate-logo vests and Yankee hats, but in 1986 this was a Mets town. And few teams ever fit their towns better than the ’86 Mets fit New York City. Everyone from everywhere else hated the New York Mets, but the Mets didn’t give a fuck what you thought of them, because what was the point of being from anywhere else?

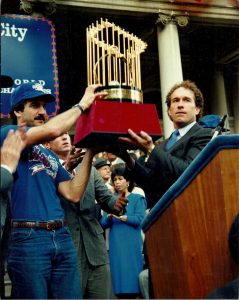

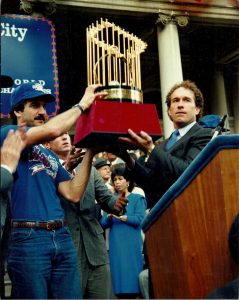

With the Red Sox done and no one left to vanquish, the Mets were given a ticker-tape parade and a ceremony on the steps of City Hall. Photos of the ceremony capture two ’86 Mets — the unquestioned leaders of the club — standing on either side of the World Series trophy they’ve hoisted into the air.

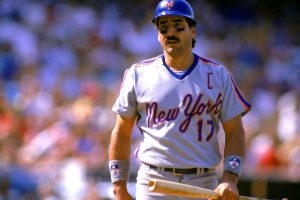

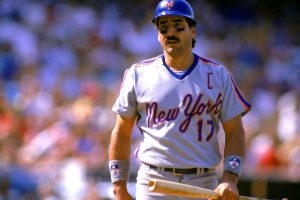

The man on the right is Gary Carter, the Mets’ tough-as-nails catcher and No. 4 hitter, a man with a sunny personality and a deep reservoir of faith. He looks like a kid at a church service — he’s wearing a jacket and tie and is shaven and scrubbed.

The man on the left is Keith Hernandez, the Mets’ tough-as-nails first baseman and No. 3 hitter, a man with a personality full of shadows and a deep reservoir of complications. He looks like shit — he’s unshaven and dressed in a cap, t-shirt and jeans. The surprise is that he somehow managed to find a belt. The man on the left is Keith Hernandez, the Mets’ tough-as-nails first baseman and No. 3 hitter, a man with a personality full of shadows and a deep reservoir of complications. He looks like shit — he’s unshaven and dressed in a cap, t-shirt and jeans. The surprise is that he somehow managed to find a belt.

Both men, as it happened, celebrated the night before. But Carter went home at a reasonable hour (or at least one assumes he did, and it’s a safe assumption), got up, got dressed, and got himself to Shea Stadium in plenty of time for the 10 a.m. police escort to Lower Manhattan and the parade down the Canyon of Heroes. Hernandez stayed up all night boozing it with Bob Ojeda, went home at 7 a.m., woke up at noon, and only made the ceremony because Met fans recognized him and Ojeda and lifted them over a fence. Odds are he’s exuding a radioactive cloud of hangover sweat, and that Carter has looked over at least once and thought, “C’mon, really?”

It’s like Goofus and Gallant from the old Highlights feature, except for one thing: Goofus is there where he’s supposed to be. Gallant did a whole bunch of things that Goofus should have done and maybe now wishes he had done, but they both made the ceremony. They’re both holding up that trophy. And if you know the ’86 Mets, Gallant doing the right thing wouldn’t have meant a damn thing without Goofus as his bookend, doing what had to be done.

That was the Keith Hernandez I knew, the Keith Hernandez I adored, and the Keith Hernandez I wanted to be.

Look, I loved Gary Carter — he was simultaneously a truly decent human being and a ruthless competitor, which gave his successes against the likes of Charlie Kerfeld the moral clarity of a good parable. But I couldn’t imagine being him, or wanting to be him. Carter was straightforward and sunny and religious, and even at 17 I knew I wasn’t any of those things.

Meanwhile, some writer — most likely it was Chris Smith of New York, who wrote a string of wonderful Hernandez features back in the day — called Hernandez the hero of every guy who’s out until 3 a.m. but still gets the job done at work the next day. Keith’s reaction: “I thought that was well put.” That I could understand and take to heart. And I did: When I was younger there were most definitely office days after long nights when I’d bull my way to bleary-eyed success and think, Seinfeld-style, “I’m Keith Hernandez!”

That’s not to diminish Carter. But fundamentally, there are Gary people and Keith people, just like there are Mick people and Keith people and Chuck D. people and Flavor Flav people and Luke people and Han people. And I realized pretty early on that I was a Keith person.

The C is for “complicated.” Next time they show Game 7 of the ’86 Series, stop and watch Hernandez’s crucial at-bat, the one in the sixth inning.

There he is staring out at Bruce Hurst with a combination of a surgeon’s concentration and a gangster’s impatient menace. He looks impossibly small and lithe compared with today’s players — today he’d be a fourth outfielder, maybe. When he was out of uniform his signature mustache struck me as distinguished, but that’s not the impression you got seeing it paired with an 80s mullet and unshaven face — staring out at Hurst, he looks like a pirate, or maybe a rock star.

The first pitch is called a strike; Hernandez reacts with indignant disbelief. Second pitch, bang! He pounces, that oddly long-armed swing uncoiling, and here come Lee Mazzilli and Mookie Wilson to cut Boston’s lead to 3-2. The camera jumps back to Keith on first base. He’s cool for a moment, standing there with Bill Robinson, and then the emotion overflows and he’s not so cool.

A first pump.

A yell.

That’s not enough, so one more of each.

“Yeah!” FUCK YEAH!”

That’s more like it.

We’re not done, though. The next batter is Carter, who hits a little flare that Dwight Evans rolls over in right field, leaving Hernandez caught in no-man’s land. He’s tagged out at second as Wally Backman scores the tying run. Being Keith, he starts hollering at umpire Dale Ford, as if Ford should have developed X-ray vision in anticipation of being blocked out. Ray Knight — Rusty Staub‘s successor as bodyguard/counselor to Hernandez — has to calm him down on his way into the dugout.

In a couple of minutes, you’ve been given a portrait of Keith Hernandez. Cool focus sharing space with fuming impatience, emotions boiling over, a bad idea not suppressed in time. That was Keith. But remember the context: all of that was the window dressing for a huge clutch hit. That was Keith too.

(And the rest? The blitzing through God knows how many watering holes in an all-night celebration? That was most definitely Keith. And so was getting to the parade on time, despite it all.)

All this seems preordained now that Hernandez is a fixture in the Mets booth and a New York icon. But it wasn’t — rather than arrive like a conquering hero, Keith Hernandez crept into town a stunned exile.

In 1986, William Nack penned an essential profile of Hernandez for Sports Illustrated, exploring the demons that drove him, denied him solace and also — cruelly — made him great. The story begins, as such complicated tales often do, with the father. John Hernandez was a first baseman who hit .650 his senior year in high school, good enough to be signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers. Playing under lousy minor-league lights in Georgia, he lost sight of a pitch, which hit him in the head.

His eyesight never recovered, dooming his career. So he taught his sons — Gary and his younger brother Keith — to play baseball. To call the elder Hernandez domineering would be to put it mildly: He’d berate his children for a single poor at-bat and give them written exams about defensive positioning.

Keith was the more promising athlete and tightly wound instead of happy-go-lucky like Gary, so he bore the worst of it. But his father was also an excellent teacher, and the best coach his son would ever have. Which he never let Keith forget — Nack chronicles boom-and-bust cycles of recrimination and rapprochement, with Keith complaining that he can’t stand the thought of his father watching his at-bats via a satellite-TV rig (which Keith bought), then needing him to diagnose a bad habit that’s crept into his swing.

(The story has a melancholy epilogue: John Hernandez died not long after his son’s playing career ended, with their issues largely unresolved.)

Hernandez battled insecurity and loneliness as a Cardinals rookie, overcame it with the help of veterans (Lou Brock and Bob Gibson were vital mentors, the first sympathetic and the second famously not), shared an MVP award, got married, got divorced, developed an infatuation with cocaine, kicked it, wound up in Whitey Herzog‘s doghouse, and was exiled to the hapless Mets in the summer of 1983.

His first reaction was to ask his agent if he had enough money to retire. Fortunately — for the Mets, for all of us, and for Hernandez himself — he didn’t.

Hernandez’s brother told him about the minor-league talent the Mets had in the pipeline. Staub took the new first baseman under his wing and told him that as a single guy he had to live in the city. And something wonderful happened to Keith Hernandez: Forced to become the on-field leader of a team that needed him, he found he relished the role and thrived in it, just as he found he loved New York and all it had to offer.

Instead of exile, he found a place for his best self to blossom. Three years later, he was a World Champion and a Gotham icon. In 1987, the recently departed Pete Hamill wrote that “New Yorkers don’t easily accept ballplayers. They almost always come from somewhere else, itinerants and mercenaries, and most of them are rejected. … Those who are accepted seem to have been part of New York forever. Hernandez is one of them.”

He was then and he is now. Has there ever been a more successful post-career second act in a Met life? One day, the Mets will retire No. 17 for him — and if they’re honest about it, they’ll retire it as much for his career in the booth and his simple existence as they will for the relevant lines in his Baseball Reference entry. Keith’s Mets career, while glorious, was a little too curtailed to merit a retired number in this fan’s opinion, but throw in everything he’s meant to the ballclub and its fanbase since then and he’s in a shoo-in.

In his role as a color guy on SNY, I confess that Hernandez can drive me batty. He’s often caught not paying attention, repeating something Gary Cohen or Ron Darling just said. And he can be disappointingly reactionary about anything new, whether it’s women in on-field roles (hopefully he’s grown out of that one), the shift, or a seemingly innocuous thing such as players carrying scouting reports in their pockets. Would a 15th-century Keith have hated the printing press? Do you have to even ask? It makes me crazy because it’s a tragedy for someone so ferociously smart to be habitually close-minded.

But there’s so much more to Hernandez than that. He’ll also break down a defensive play with a jeweler’s eye, or explain what a hitter should be looking for at the plate with stunning clarity. When he finds a defender’s positioning or a hitter’s approach lacking, you can hear the indignation in his voice, fueled by a certainty that he would have done it properly. You can hear Bob Gibson in there, and John Hernandez, and all the complications one senses Keith Hernandez has yet to untangle. And I never have the slightest doubt that he’s right. He would have done it better. Didn’t I see him demonstrate that hundreds of times? But there’s so much more to Hernandez than that. He’ll also break down a defensive play with a jeweler’s eye, or explain what a hitter should be looking for at the plate with stunning clarity. When he finds a defender’s positioning or a hitter’s approach lacking, you can hear the indignation in his voice, fueled by a certainty that he would have done it properly. You can hear Bob Gibson in there, and John Hernandez, and all the complications one senses Keith Hernandez has yet to untangle. And I never have the slightest doubt that he’s right. He would have done it better. Didn’t I see him demonstrate that hundreds of times?

At some point in any broadcast, I’ll grumble at Keith being snide, dismissive or indignant. But I’m also guaranteed a moment where he’s being enormously entertaining — it might be lamenting the need to put a tent on this particular circus, exasperation at how long this is taking, or some random tale from his endlessly interesting life. And I’ll almost always turn off the TV with a greater appreciation for some fine point of the game. He was smart and impatient and complicated and sometimes his own worst enemy then. He’s the same today. I wouldn’t have him any other way.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2019: Dom Smith

by Jason Fry on 13 August 2020 9:49 pm The Mets face challenges in this 60-game improv season: iffy defense, shredded starting pitching, an uncertain bullpen. An added challenge, for those of us watching from the socially distanced cheap seats, is how quickly it’s all going by.

I don’t buy the each game is equal to four and change thing, because it has nothing to do with how baseball is actually played. But it is more than a little startling to just be getting used to a roster and realize that a third of the season is complete. Baseball isn’t being played on fast-forward, but my baseball emotions feel like someone has that button mashed down. Each little tailspin feels like the team just got eliminated on some soggy matinee in September, and I have to remind myself it isn’t that way at all.

What helps with feelings like these? The same thing that helps with all baseball maladies — having your team win a game and look competent doing it. Funny how that cures all ills.

Thursday afternoon’s game was an entertaining one — some heart-in-the-throat moments, a scary storyline to follow, an unlikely hero, more good things from young players — that went in the win column. It didn’t exactly start well: David Peterson walked Trea Turner, was hurt by a throwing error by Tomas Nido that put the loathsome Adam Eaton on base, and then walked Starlin Castro. Bases loaded, nobody out, and up to the plate came Juan Soto, who may as well be called That Man Again in these parts.

Peterson got Soto to foul off a sinker, got a strike on a changeup, and then erased the most dangerous man in the Washington lineup — and maybe the N.L. East — on a nifty slider. The next hitter, the annoyingly capable Howie Kendrick, grounded out but brought Turner home. Up came Asdrubal Cabrera, who smashed a ball on a line up the left-field gap. Jeff McNeil got there, reached above his head, plowed into the fence, and held up the ball.

It was a great play — shades of Mike Baxter damaging his career to preserve Johan Santana‘s no-hitter — with McNeil so prioritizing hanging onto the ball that while he lay on the warning track I was a little worried he’d concussed himself so thoroughly that the ball would have to be pried out of his glove. (The diagnosis, after he was carted off the field, was a bone contusion, which isn’t great but is about the best medical update one can get in a sentence that also includes “carted off the field.”)

The Mets had avoided disaster — and as they did Wednesday night, they went to work on the Nats. Peterson settled in, ultimately allowing just one hit over five innings. Meanwhile, Dom Smith smashed a solo homer to tie the game, Nido hit a two-run shot to grab the lead, and then Nido sealed the game with a grand slam off Seth Romero, making his big-league debut wearing 96 and the slightly glassy-eyed look you’d expect to find on the face of a young man called into a big-league game after never pitching above the Sally League. Romero spent 2018 with the Hagerstown Suns, whose stadium I’ve been to several times. The difference between coming in for relief there and arriving at Citi Field (even without fans) must be comparable to the difference between singing along to a playlist in your car when no one’s watching and stepping onstage at the Apollo and peering out into the blinding lights.

Romero will have better days; Nido may not. That’s no insult — two homers and six runs batted in is hard to equal when your role is to play day games after night games. Even if he never reaches these heights again, Nido may prove useful in a way a big-league team could use: He’s looked better this year, perhaps aware that most every backup catcher is regarded as a suspect by his ballclub, perhaps annoyed that no one seems to remember he won a batting title in the minors, perhaps a little of both.

Nido’s defense is already good enough for any big-league team; if he can hit even a little, he can retire sometime in the 2030s as a wealthy man. On Thursday he hit a lot more than a little, and it was beautiful to see.

by Greg Prince on 13 August 2020 5:44 am In doing my nightly postgame statistical rounds, I noticed that the score by which the Mets beat the Washington Nationals on Wednesday, 11-6, had been gathering dust for quite some time. Until Wednesday, when the Mets exploded with practically unimaginable amounts of offense and it still seemed barely enough to fend off one particular precocious Nat, the Mets hadn’t won, 11-6, against anybody in slightly more than sixteen years, making it the 22nd-least recent winning score on the Met books. Now it’s the most recent.

Perhaps it appeared the Mets would require sixteen years or at least that many pitchers to get out of the top of the first inning at Citi Field when Robert Gsellman, starting for the first time since the Mets’ final home game three years ago, put two runners on and then discovered one more competitive innovation baseball has introduced since September 27, 2017: the advent of Juan Soto. True, he’d faced the kid in relief a few times, but this had to feel different. This was his whole night set out in front of him, a night Gsellman’d been craving in his starting pitcher heart all those nights he found himself reluctantly warming up in the middle innings. Sixty feet, six inches away was Soto, 21 and regularly evoking mentions of Mel Ott slugging — and not just because they both bear nifty crossword puzzle solutions as last names.

In case Gsellman forgot what it was like to be planted in the bullpen, Soto reminded him, as the home run he swatted flew well over it…and everything else at Citi Field. I’m sure the ball got a decent view of everything below its own stitches, though binoculars were probably required. When the 466-foot journey of Soto’s three-run welcome-back-Bob bomb completed its statistical rounds, the ball could be seen bouncing way in the back of the soft drink-sponsored pavilion far above right field. I think it knocked on the men’s room door to the left of the stand where they usually sell cola.

I’m sure Gsellman contemplated a quick trip to the facilities himself. The only thing that got him out of the first was Soto wasn’t due up again right away. And then, contrary to recent home team custom, he was presented with a lead by his friends in the Mets batting order. If they weren’t his friends already, they should be by now. The Mets’ batters, reputed for their courtesy in not disturbing Met runners in scoring position, learned the benefits of rudeness. Brandon Nimmo skipped the whole “runners on” thing when he led off with a homer against ancient Anibal Sanchez. Sanchez, 36, threw a no-hitter in 2006. It was so long ago that it had been only two years since the Mets had last won an 11-6 game; Soto was 7.

Nimmo, who’s too nice to come off as rude, nonetheless set a useful example for the batters who followed him to the plate, most of them turning impolite toward the opposing pitcher.

After Sanchez hit Michael Conforto, Pete Alonso hit Sanchez, doubling in Conforto. Dom Smith, listed as playing some alien position that has no business in National League baseball, doubled in Alonso. Wunderkind Andrés Giménez, who is somehow six weeks older than Juan Soto, singled in Smith. The Mets and Gsellman were out in front. Gsellman didn’t last but two innings as he reacclimated himself to his old role (“Man, I was so nervous,” he said afterward. “I felt like a little kid.”), but the Mets were generous to his myriad successors, adding a run in the third — which was countered by another Juan-ton act of slugging — and five in the sixth. Michael doubled with two on. Pete homered with Michael on. Dom homered immediately thereafter. The Mets hit with runners in scoring position and hit deep with bases clear of occupants. They collected thirteen hits and put them to excellent use to create eleven runs. Soto could produce only four on his own, with his teammates chipping in just two.

That’s how we got to 11-6 in one game. Why it took sixteen years to get to 11-6 since the last 11-6 Mets win is one of those little mysteries that make doing one’s nightly statistical rounds such an enigmatic delight. Historically, 11-6 hasn’t been a wholly uncommon score for the Mets to win by. From 1962 through 2004, the Mets had beaten an opponent, 11-6, eleven times in regular-season play. Maybe not a “normal” baseball score, but not so crazy that you think you’d need a decade-and-a-half and then some to see it again. Hell, Game Two of the 1969 National League Championship Series, wound up 11-6 for the Mets over the Braves on a day Jerry Koosman didn’t quite have his best stuff, but Messrs. Agee, Garrett, Jones and Shamsky blessedly did. It was the second postseason game the Mets ever played and 11-6 already represented half their postseason wins.

I don’t know why some scores simply fall out of fashion, as if there are tastemakers who determine how much a team wins or loses by and whether the combination can be considered chic enough to gain a measure of mass-market popularity. When the Mets beat the Red Sox, 8-3, a couple of weeks ago, it was their first 8-3 regular-season win since the last day of the 2014 season. There’s nothing remotely Unicorn-ish about an 8-3 score — the Mets had won a regular-season game by an 8-3 score 46 times over the first 53 seasons of the franchise’s history, but then more than five years passed before another 8-3 regular-season win. The Mets did beat the Cubs, 8-3, on October 21, 2015, but that was the clinching game of the NLCS (just the pennant, that’s all), so it doesn’t quite count under this exacting statistical umbrella I’m brandishing. And even if it does, that means it still took more than four years, until July 28, 2020, to produce another 8-3 win. An 8-3 win is a lot closer to “normal” than 11-6, yet it was wholly elusive for quite a spell there.

I’d say, “go figure,” but you can’t. All you can do, if you’re so inclined, is record that it happened.

The previous game the Mets won, 11-6, took place on August 5, 2004. I remember it clearly specifically for having not seen it or heard it. I had business in Washington that Thursday afternoon and was on an Acela back to New York when I was able to tune in on my trusty tiny radio the staticky news of what the Mets had done in their matinee in Milwaukee. Victor Zambrano made his Met debut a victorious one (four earned runs in a five-and-a-third innings, but he left with a large lead); David Wright drove in six runs to raise his career RBI total to ten; and the city I was putting behind me probably couldn’t have cared less that the Mets were romping in Wisconsin. In August of 2004, the Washington Nationals were still the Montreal Expos.

That was the last game I missed altogether in 2004, a fact that sticks with me because when the next season began, I wasn’t just watching or listening for me, but for whoever was reading this blog. I wouldn’t miss another Mets game until August of 2006 and have rarely missed one since. Yet at no time until August of 2020 did an 11-6 Mets win enter the current-affairs segment of our ongoing conversation here. Now it has.

I’ll say it: go figure.

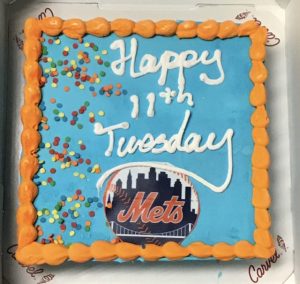

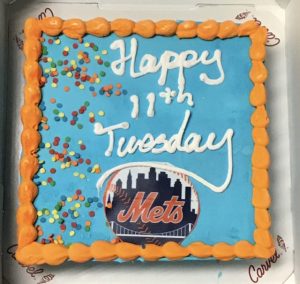

***In the realm of rituals related to keeping track, I’ve been part of a foursome that has attended the first mutually available and amenable Tuesday night game at Citi Field for ten years. This tradition dates back to August 10, 2010, when my wife Stephanie and I met up with Ryder Chasin and his father Rob to see the Mets take on the Rockies. It was our first game together if not our first time together at Citi Field. About a year earlier, the Chasins had gotten in touch with us and invited us to Ryder’s forthcoming Bar Mitzvah, November 14, 2009. Ryder, 12 going on 13, was a Mets Fan Who Liked to Read; his coming-of-age celebration would be at the Acela Club (now known as the Porsche Grill despite Acela rating two product placements in today’s column); and, well, would we like to join them?

Would we? It was too intriguing to pass up, and that was with only knowing Ryder and Rob from one letter apiece. Long, oft-told story short, Stephanie and I attended, we all stayed pals, and we consecrated our Metsian bond with a Tuesday night game the following August. Why Tuesday night? I don’t remember, but it became our thing. Ten Augusts, ten Tuesday nights, the four of us. Ryder, a couple of years the senior of Juan Soto and Andrés Giménez, graduated everything there was to graduate and is now a professional writer himself, 23 going on 24. Like that pitch Gsellman threw to Soto, time really flew.

Who’s gonna argue technicalities with a cake? It landed in August of 2020, when there’d be no going to Citi Field for any of us or anybody else. No going anywhere, for the most part. Our Tuesday night tradition could have been pardoned for pausing in deference to These Challenging Times, but Rob and Ryder thought better of it and did the best they could to make it eleven in a row. Thus, on Tuesday night, August 11, 2020, our friends the Chasins arranged to Zoom Stephanie and me shortly before 7:10 first pitch. Rob even had a specially decorated Carvel cake simultaneously delivered to our address to mark the continuation of our indefatigable occasion. As that element was intended as a surprise, I at first opted not to answer when a gentleman bearing frozen gifts rang, because, geez, I’m on a Zoom here, who the hell is suddenly bothering us? Good thing I was clued in so I could run to the door and accept the incredible gesture. Ice cream cakes in August don’t lend themselves to contact-free delivery.

Stephanie and I spent about two hours on our respective screens with Ryder and Rob, catching up about baseball and whatever else infiltrated our collective consciousness. (I resisted the temptation to blurt to Ryder, “My god, you’re like TOTALLY an adult now!”) Our eyes naturally darted to nearby televisions to keep up with the Mets and Nats, though the game wasn’t much more than an unobtrusive backdrop after a while. Still, it was the reason we’d virtually gathered, which led to a perplexing philosophical quandary.

Did this count?

Everything about baseball is about counting. It’s why we’re watching this short season that in so many ways feels like it shouldn’t be taking place in a pandemic. It counts. The games count. The scores count. Every run. Every run given up. We who can’t miss a game that counts unless we have to be on a train before the advent of apps adhere closely to counting what counts. The 11-6 win on August 12, 2020, counts like the 11-6 win from August 5, 2004 counts. The 11-6 win from October 5, 1969, counts, too, but like the 8-3 win from October 21, 2015, it counts differently. Counting what counts is what separates from the animals who don’t keep count.

I held up to the camera for Ryder’s and Rob’s edification the notebook in which I write down the result of each game I go to. I call it The Log II. The Log was filled with my Shea Stadium games. The Log II covers Citi Field. Every one of our August Tuesday night games are in there. The six wins. The four losses. The starting pitchers. The opponents. It’s all inked in. Despite the spirit of the Zoom and the affection baked into the cake, could I, in all good counting consciousness, pick up my pen and write down the spare but essential details of our eleventh consecutive Tuesday night in August if it wasn’t exactly our eleventh consecutive Tuesday night in August at Citi Field? I don’t count in The Log II games I don’t physically attend.

But The Log II doesn’t track everything about the games I go to. It certainly hasn’t recorded the heart of those ten August Tuesday nights with the Chasins.

Not written down in my spiral-bound steno pad is that we greeted each other heartily outside Citi Field ten times.

That we embraced as people who were close to one another did until 2020.

That we grumbled our way through security; me, mostly.

That once safely within the circular walls of the Jackie Robinson Rotunda, Ryder and I immediately wandered deep into “what’s wrong with the Mets?” (or a couple of times the inverse) territory while Stephanie and Rob presumably talked about other, less pressing matters.

That we decided what we were gonna get to eat and, if it differed, where we were gonna meet so we could eat it together and talk some more between bites.

That one time Rob amazingly managed to get us on the field for batting practice and Ryder snagged autographs from Jordany Valdespin and Justin Turner.

That another time we wound up sitting behind some thin blonde woman who never once looked up at the game because she was too busy tweeting literal Fox News talking points at all who dared argue with the positions she steadily tapped out, spectacularly oblivious to the big league baseball unfolding not too many rows in front of her. Shocked that somebody could care that little for the Mets or their foes, I squinted over her shoulder at her phone and deduced the disinterested filler of this perfectly good ballpark seat was Fox News talking head Kayleigh McEnany. I had never heard of Fox News talking head Kayleigh McEnany until then, but I looked her up when I got home and learned she was dating or maybe already engaged to Met reliever Sean Gilmartin, which I guess explained why she was there. They later married despite her apparent lack of emotional investment in his profession (I understand she holds a government job these days).

That last year Rob furnished a tenth-anniversary scoreboard message for the Mets to include among their various midgame Happy Birthday greetings.

That I’d keep score for a stray half-inning if Ryder was racing to and racing back from the concessions.

That Rob, Ryder, Stephanie and I would conduct a version of musical chairs a couple of times per game so everybody could talk some to everybody else.

That even when the score fell in the Mets’ favor, we were a little sad the game was over because we did this only once a year and now it was done, but we were inevitably cheered that we knew we’d be back out here same time next year, more or less.

Much less, it turned out this year, but the Zoom was the next best thing. As we wound down our video meeting, we discussed whether it counted, if it could in fact enter The Log II. The provisional decision reached was maybe in pencil. It’s not ink, but it’s not nothing.

That was Tuesday. I haven’t written it down yet. I don’t know if I will. Really, I don’t think I have to. We know we kept our thing going. Eleven in a row, just like it says on the cake.

Next year? Twelve in Flushing. I won’t count on it, but I will hope.

by Jason Fry on 12 August 2020 10:30 am Perhaps I should put a SPOILER WARNING on this one, but I received a special media preview of the Mets’ 2020 highlights video, and it’s 23 minutes of Jeff McNeil screaming “FUCK!” after making an out and five minutes of Andres Gimenez smoothly fielding hard grounders.

And you know what? I’m strangely OK with it.

The Mets lost Tuesday night, 2-1, with Max Scherzer outdueling Rick Porcello. The Mets turned in some nifty defensive plays, with Gimenez and possible Wednesday starter Luis Guillorme front and center in the infield, but (shockingly) couldn’t find the big hit in the clutch they desperately needed, and so it goes.

Maybe this is just me bargaining, but I’m in a better place than I would have guessed.

Part of that is having baseball back at all, something I figured wouldn’t happen, and that you could argue shouldn’t happen given the current problems with the Cardinals, not to mention the Marlins having to essentially come up with an entire B-team to keep going. The Mets have been hale if not hearty so far, and even though the results haven’t been there, their presence has made summer feel a bit more normal.

Tonight we sat in a backyard and drank with old friends (socially distanced of course), during which the Nats jumped out to a 1-0 lead and a 2-0 lead. We returned to our rented beach house and saw the Mets draw within 2-1, then turned up the TV so the Mets could be our company during dinner on the deck. Everything was pleasant except the score — this was one of those games that didn’t feel anywhere near as close as it was — and I was happier to have the Mets present but on the short side of the outcome than I would have been to have a night with no baseball at all.

There’s Gimenez, of course, whose fluid fielding and superlative baseball instincts are a reminder of baseball’s balletic perfection. There’s the steady parade of new Mets — the Mets were pummeled mercilessly Monday night, but I still smiled to see Ali Sanchez escape becoming the 10th Mets ghost. Sanchez had the greatest night of his baseball career despite seeing one pitch which became a double play, which makes sense when you consider the alternative. Similarly, it was fun watching Guillorme retire three straight Nats with 63 MPH non-gas, going so far as to ask for the ball from the first batter retired.

Even Marcus Stroman is a part of my unexpected equanimity, somehow. I don’t blame Stroman for opting out — I don’t presume to know anything about what’s going on in someone’s family — any more than I blame him for possibly manipulating his way to free agency through service time, given how routinely baseball teams manipulate service time for their own advantage.

When Stroman arrived last summer, I was happy to see him while dreading what his arrival might mean — I assumed the Mets had imported him as precursor for trading Noah Syndergaard or Zack Wheeler. They kept both Syndergaard and Wheeler for the season, but then let Wheeler become a free agent in the offseason, with nary a hint of interest or a peep of protest, making my prediction ultimately accurate if not timely.

In late July of 2019 the Mets’ rotation was Jacob deGrom, Syndergaard, Wheeler, Steven Matz and Stroman. A little over a year later, it’s been reduced to deGrom and Matz, and the latter has been giving up home runs with frightening frequency. When Stroman opted out, I could all but hear the Mets’ playoff window slamming shut — yes, they have a corps of young and effective hitters, but if Matz has lost his way, where do the arms come from? But rather than blame Stroman for a decision I couldn’t be privy to, I blamed the Mets for letting a potentially great rotation become hollowed out and vulnerable to injury and mischance.

It doesn’t make me happy to contemplate such things. But the ebb and flow of team fortunes are nothing new. And in this weirdo improv season, I’d rather obsess about that ebb and flow than stare at a year of nothing.

Once again, is that bargaining? Maybe it is. But we’re all bargaining this year, constantly reassessing what scares us and how much and what plans we should and shouldn’t make. Baseball has been my faithful companion in years both fruitful and barren; I’m glad to have it again for a year where uncertainty colors each and every day.

|

|

Of course I had nothing to worry about. Carter couldn’t have been kinder. He signed my book — To Jay Fry, Hope you enjoy the dream! God bless always, Gary Carter — and my mom left, a fan who’d met a baseball hero and come away thinking better of him.

Of course I had nothing to worry about. Carter couldn’t have been kinder. He signed my book — To Jay Fry, Hope you enjoy the dream! God bless always, Gary Carter — and my mom left, a fan who’d met a baseball hero and come away thinking better of him.