The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 12 June 2025 7:54 pm All wins are created equal in the standings. Some wins are a little less equal emotionally. Some wins take a back seat to other events surrounding a given game. It doesn’t happen often, but it happens.

Mets fire a manager but win as a going-away present to their suddenly erstwhile skipper? The win doesn’t resonate.

Mets raise a white flag by trading a perfectly good player because their sagging record indicates a diminishing need for perfectly good players the rest of the year? The win gets less of your attention than who we got in exchange for the perfectly good player.

Mets blow a seemingly unblowable lead late but get it back after you’re overwhelmed by so much Sturm und Drang you barely notice that everything turned out OK? Depending on the severity of the nonfatal gag job, the win can feel like an undeserved consolation prize — you’ll take it, but you feel a little skeevy about the whole thing.

Mets suffer an injury while in the midst of everything going well, and go on to win while waiting to announce the nature of the injury? You’re absolutely happy to have the win, especially since you lately find yourself addicted to chronic winning, but the injury rather than the victory rides in the front seat of your thoughts.

The Mets on Thursday afternoon at Citi Field notched one of those back seat wins, topping the Nationals, 4-3. No managers were fired; no players were traded; a lead was nearly blown late but never actually got away, so we’ll let that brush with fallibility slide. Thursday, however, was one of those days when a Met — a key Met, at that — had to leave the game less than healthy, and true solace wasn’t readily attainable from the final posted on the scoreboard.

Oh, we’ll take it. We’ll take Jeff McNeil’s three-run homer in the first and Brandon Nimmo’s solo shot in the fifth and Tyrone Taylor’s Tommie Agee impression in the outfield in the sixth. We won’t overlook, either, that Luisangel Acuña made a very heady play in the top of the ninth to make sure a bullpen meltdown soaring toward Level 7 never reached the stage where you’ll want to avoid locally sourced milk for a generation. When it was over, the Mets do what they do when they win. They gathered in a circle and choreographed a celebratory kick. Having won six in a row en route to mounting, the best record in baseball, they’ve become very practiced in victory celebrations.

Winning is always a kick, even if a strain to the hamstring is tantamount to a kick in the head. We definitely appreciated all the positives that turned the Mets into Rockettes, but we couldn’t and didn’t stop thinking about Kodai Senga, who was humming along with a shutout in the sixth, reducing his microscopic earned run average to a nearly indecipherable dot, when, in the process of covering first base on a grounder to Pete Alonso, had something happen to his right leg. A cramp? A strain? A what? We didn’t know while Senga knelt on the ground nor when he rose and walked off without assistance to exit the field. The last act of his 1.47 ERA season to date was a leap in the air and a step on the bag after hauling in Alonso’s less than ideal toss of CJ Abrams’s relatively routine groundout. Senga said he’d felt something before exerting the extra effort to reel in Pete’s fling. Pete said he felt “awful” about perhaps exacerbating an injury in the making. Carlos Mendoza reported afterward the early diagnosis is hamstring strain. A trip to the IL and the MRI machine, in that order, are prescribed. Everything else is TBD.

It was a 3-1 putout that overshadowed a 4-3 win. The Met rotation with Senga, even as it’s required the insertion of random sixth starters from time to time, is stronger by multitudes than what we deployed 161 of 162 games last year, and last year’s starting pitching was pretty darn good. It would have been better had Kodai been available before and after July 26, his one regular-season outing of 2024, the one that was also going swimmingly, the one that was also interrupted by the covering of first base, the one that also had us wondering what just went wrong. Eleven months ago, it was a left calf strain that negated his comeback from the shoulder injury he endured in Spring. Never mind the DH. Let’s get this man a designated fielder.

The Mets maintain the depth to deal with a starting pitcher missing a thus far indeterminate period of time. Last season’s anchor, Sean Manaea, is rehabbing. One of last winter’s acquisitions, Frankie Montas, is doing the same. Last summer’s insurance policy, Paul Blackburn, is alive and well and on the active roster. Somebody will pitch and, I’m willing to say while we exist in an era of confidence rather than panic, pitch well. Still, the man we’ll be missing is Kodai Senga. We’ve got a lefty ace in David Peterson. We’ve got a stretched-out Clay Holmes proving the Mets were right to see in him someone who belonged at the front rather than the back of a game. We’ve got Griffin Canning emerging successfully from the alchemy of the Met pitching lab. And we’ve got gritty Tylor Megill forever hanging in there. But it was the right arm of Senga that signaled every day in six could be and usually was something extra special. We scrapped for a playoff spot last year. We are cruising as the best team in baseball this year. I’m not gonna say the definitive difference has been having Kodai Senga, but, boy, has it not hurt.

Losing him hurts. Winning without him around at day’s end didn’t feel as good as if he’d kept pitching, kept fielding without incident, kept within kicking distance of the club’s victory huddle. Yet it was still a win. That never hurts. Nor will getting him back.

by Jason Fry on 12 June 2025 7:54 am In the early days of Citi Field, there was an attempt to start a first-inning Yankee Stadium-style roll call. Thankfully wisdom prevailed and the attempt got shelved — that tradition belongs in the Bronx, just like “Sweet Caroline” belongs in Fenway. But there’s no rule that we can’t do it here.

Juan Soto: I heard Soto’s third-inning blast via the audio feed as I was putting away kayaks down in Brooklyn Bridge Park. Howie sounded excited and impressed, and the footage didn’t disappoint once I finally got to see it for myself — a majestic arc of a home run against his original team that came down to the right of the Mets’ bullpen, with a nifty catch by a young fan on the other end.

Brandon Nimmo: We sometimes judge Nimmo’s performances against our memory of him as the table-setter he was a few years ago, a top-of-the-order slash-and-dash hitter who drew walks and stole bases while chipping in ~10 homers a season. He isn’t that player any more, having traded on-base percentage and average for power while moving from center to left. We should move along with him: Two home runs — the first an opposite-field slice that almost looked accidental, the second a more conventional drive pulled to right — will play just fine.

Tyrone Taylor: It took a weirdly long time for the second-line umps to confirm that Taylor had thrown out Luis Garcia Jr. at home in the eighth, preserving David Peterson‘s shut-out and along with it, most likely, his chance at a complete game. Out in center, Taylor looked serene and unruffled, waiting for Chelsea (it’s now Midtown but so what, Chelsea sounds better) to declare that nothing supported the Nats’ oh-why-not challenge of the call. And why wouldn’t Taylor be serene? He’s not tearing the cover off the ball (no one ever is, come to think of it) but he’s playing impeccable defense, and somehow always does something that gets his name in the recap.

Luis Torrens: One of baseball’s pleasures is that it’s primarily a game of individual endeavors, yet one that adds up to collective victory or defeat. In the middle of that, though, are partnerships, duos that have to work in sync. Pitcher and catcher, for one; outfielder and catcher, for another. No Peterson complete game without Torrens thinking along with him, no Peterson shut-out without Torrens’ smooth tag at home. And note that the play didn’t end there — after tagging out Garcia, Torrens lost the ball on the transfer because he was looking to throw behind an unwary Nats runner. The man knows what he’s doing back there and we’re lucky to have him.

Carlos Mendoza: If Ryne Stanek had come out for the ninth, it would have yielded a postgame question or two for Carlos Mendoza about whether Peterson had wanted to go nine and if he could have. But it would have been a momentary, nostalgic aside and not a serious interrogation: The game has changed and it’s safe to say that Tom Seaver‘s franchise complete-game records (21 in 1971, 171 overall) are safe. Mendoza knew Peterson wanted to try, talked through the plan with Torrens, and gave Peterson his chance.

John DeMarisco: Kudos to SNY for staying with the game after the eighth inning was concluded, letting us see Peterson heading out to the mound alone (nice touch, Mets) and letting us hear the crowd’s jubilant welcome for him. That was the kind of moment those of us watching at home generally miss because of business considerations, and have come to assume we’ll miss. The Mets’ broadcast director gave us a chance to see it.

David Peterson: Well of course. Early last year I had a mild fit about “feckless nibblers” in the Mets’ rotation, a criticism that’s pretty much out of date as the pitching braintrust has encouraged Met hurlers to simplify their arsenals and trust their stuff. On Wednesday Peterson was anything but feckless and anything but a nibbler, throwing first-pitch strikes, pitching aggressively and trusting his defense. It wasn’t so long ago that we’d consigned Peterson to the prospect-turned-suspect column, wondering if he’d ever stop getting out of his own way. Time to abandon that idea: His hip is healthy and he’s made great strides in the part of the game that a starting pitcher wins or loses above the neck. Ron Darling did a good job on the broadcast talking about this element of pitching, referring to a long-ago Mets teammate whom he said had better stuff but less conviction. Darling likes to poor-mouth himself as a pitcher so I didn’t pay much attention to the first part; I did spend the better part of an inning on the second part, reviewing old Mets rosters in my head and wondering whom he was talking about.

Us: The Mets are 26-7 at Citi Field, the best home record in the game. (And the inverse of the poor Rockies’ home record, if you were wondering.) That’s overwhelmingly a result of their being really good, but let’s give at least a rounding error’s worth of credit to the big crowds that have come out all year. In the eighth and ninth my eyes were on Peterson, but also on the stands, where a significant percentage of the rooters knew what was at stake and were determined to give Peterson whatever lift they could. Cardinals fans? Bah. Fenway partisans. Meh. Wrigley rooters? Whatever. Mets fans are a wonderful combination of wary and paranoid, defiant and hopeful, history-haunted and dreamily optimistic. They also always know what’s going on.

by Jason Fry on 10 June 2025 11:07 pm Emily and I watched the first couple of innings of Tuesday night’s Mets-Nats tilt somewhat distractedly. First we were down in Dumbo at L&B Spumoni Gardens, a satellite of the classic ur-Brooklyn Sicilian-pizza joint that’s finally open after a long permitting saga. Then we were walking up the hill for home. We’d peeked at SNY, sans sound, during dinner and then switched to Howie as we strolled through Brooklyn Heights.

Somewhere around Cranberry Street a young man turned around as he passed us and asked, “Mets?”

I nodded and he said, “2-0 Nats I think.”

“3-0 now,” I told him, for we’d just heard CJ Abrams double in a run, with the Nats giving the Mets a break by sending Jose Tena home to be thrown out by a good measure. (Off a pitcher who looked less than sharp? With James Wood coming up? Why in the world would you do that?)

“Plenty of time,” I added as our temporary neighbor took in the updated score. “We’ll get ’em.”

“Plenty of time,” he agreed.

And the funny thing is that this wasn’t fannish bravado on either of our parts. I meant it; so did he. It was 3-0, and that wasn’t ideal, but the Mets had eight frames to make up that deficit. Did I know they would do it? Of course not — baseball doesn’t work that way. But I knew they could — and with so much game left, that was sufficient.

These are strange days, when Mets fans are reflexively confident, even bordering on serene. I could get used to it.

Griffin Canning never looked particularly sharp, but he hung around into the sixth; meanwhile the Mets cut that three-run deficit to two and then one before it edged up to two again, courtesy of an Abrams homer hit too high for Brandon Nimmo to pluck from the sky. The Mets looked frustrated by MacKenzie Gore, who used a sharp curveball as a putaway pitch. But they got into the Nats bullpen while Jose Butto and Jose Castillo and newcomer Justin Garza held the fort.

In the eighth, the Nats got a little unlucky. Starling Marte doesn’t always turn in the most dogged ABs, but he refused to chase against Jose Ferrer‘s sinker and worked out a walk. Juan Soto then smoked a slider to right with a lot of English. Robert Hassell III could have played it on a hop but thought he could catch it. Instead it wound up behind him, scoring Marte and sending Soto to second. (Soto would have been on third but didn’t run hard out of the box, something I thought we’d sorted out.)

The Nats called on closer Kyle Finnegan, whose second pitch was a splitter at the bottom of the strike zone that Pete Alonso somehow sliced into left, past Wood. Soto scored; coming into second with the ball already there, Alonso tried the same switch-hands okie-doke that worked in Colorado … which actually worked again, at least until the Polar Bear came off the base and was tagged out.

Still, the Mets had tied it. Edwin Diaz worked a spotless top of the ninth, Finnegan recovered to do the same in his half-inning, and it was time for a little Manfredball.

The Nats got off on the right foot in the tenth before a ball was even put in play, as the speedy Abrams was their ghost runner. Wood moved him to third, but then Reed Garrett erased Nathaniel Lowe on three pitches and got Andres Chaparro to fly out to Nimmo.

It was the Mets’ turn, and if you came back a little late from the john you missed the whole thing: Jeff McNeil smacked the first pitch over the infield to score Luisangel Acuna, with poor Cole Henry getting the loss in appearance that maybe lasted nine seconds and McNeil grappling Steve Gelbs to ensure they both got a victory bath from the cooler.

“This is a thing now?” asked an amused-because-he-has-to-be Gelbs, with McNeil informing him that yeah, it’s a thing.

Plenty of time, we’ll get ’em.

Strange days, but maybe it’s a thing now.

by Greg Prince on 9 June 2025 4:21 pm Maybe you remember The Game-Ending Unassisted Triple Play Game, or TGEUTPG. If a game earns its name from a particular event within, it stands a pretty good chance of maintaining notoriety, with “notoriety” in this case being used correctly.

TGEUTPG concluded with Luis Castillo on second base, Daniel Murphy on first, and Jeff Francoeur batting in the bottom of the ninth inning at Citi Field in one blink and then all of them out the next. Francoeur shot a liner up the middle. The runners took off. Stepping into the picture was Eric Bruntlett, who, unlike the aforementioned players, wasn’t a member of the New York Mets. The second baseman for the Philadelphia Phillies grabbed Francoeur’s liner; stepped on second to erase Castillo; and then tagged an unelusive Murphy. There we had it: an unassisted triple play to end the game at Phillies 9 Mets 7 on August 23, 2009.

The significance of TGEUTPG nearly sixteen years later is apparent only if you keep the table that I keep. Under the table’s heading LAST TIME THE METS WERE THIS MANY GAMES UNDER .500, I have charted the most recent instance that the Mets were precisely one game beneath the break-even point as a franchise; two games beneath the break-even point as a franchise; three games beneath the break-even point as a franchise; and every juncture on down until I can tell you the last time the Mets were 503 games beneath the break-even point as a franchise. Five-hundred three games below .500 is the low-water mark for this exercise. It was reached on September 25, 1983, at Wrigley Field after the Cubs conked the Mets, 11-7. It had been 11-3 heading to the ninth, but George Foster and Gary Rajsich homered; Wally Backman tripled in Brian Giles; and Junior Ortiz doubled home Backman. That’s a helluva rally under most circumstances.

Most circumstances haven’t reflected well on the Mets’ all-time record. Through that Sunday afternoon in Chicago, the Mets had posted 1,493 wins in their nearly 22 years of existence against 1,996 losses. The Mets had been falling from .500 from the end of the ninth inning on April 11, 1962, first without interruption — the Mets were 0-9 after nine games of life — and then as a rule. That will happen when you don’t win more games than you lose in any of the first seven seasons that you play ball.

And even when you begin to get it together in your eighth season, I mean really get it together as the Mets did in their eighth season of 1969, you still face quite a climb upward. Because you don’t win ’em all, you can register only net gains. The Mets netted +38 in their first world championship year of ’69 when they finished out their schedule at 100-62. The Mets netted +54 after going 108-54 in their second world championship year of 1986. Those are impressive gains. But those great years and the very or pretty good years in their proximity couldn’t make up the torrent of ground that was lost early on when the Mets were going 40-120 (-80) and 51-111 (-60) and so on, especially when you eventually cease to be great, very good, or pretty good, and begin to backslide.

As of August 23, 2009, the Mets were in the early stages of what grew into a substantial backslide. That was the first year of Citi Field, the year when everything that could go wrong did go wrong. The franchise had made net gains via annual won-lost records for the preceding four seasons, the final four seasons at Shea: 83-79; 97-65; 88-74; 89-73. It didn’t always result in postseason opportunity (or postseason satisfaction), but things appeared on the right track for the long term.

On May 31, 2009, a Sunday at Citi, the Mets beat the Marlins, 3-2. There were no triple plays, though the Mets turned one DP and weren’t harmed by hitting into two. When the game was over, the Mets’ record sat at 27-20, a good start to what had been a shaky season to that point. Maybe this team was resilient enough to overcome the injuries that had befallen Carlos Delgado and Jose Reyes, among others, not to mention the distant dimensions of their new home. Too many of the longballs the Mets were hitting at Citi weren’t flying over fences. They hadn’t played that well on the road, either, but here they were, seven games above .500, not to mention a half-game out of first place. Maybe everything would work out for the 2009 Mets.

Nothing worked out for the 2009 Mets. That much was evident by August 23. Delgado was out for the year. Reyes was out for the year. Carlos Beltran had missed the previous two months. Even iron man David Wright was in the midst of sitting out a couple of weeks after he took a Matt Cain fastball off his batting helmet. From the game of June 1 to the moment Bruntlett tagged Murphy for the TP (u), the Mets had gone 30-47. The wrong direction continued to beckon for the remainder of 2009, a season that saw the Mets plunge to 70-92, commencing a six-year run of records when the club never reached 80 wins.

If you view Mets baseball as a vast expanse rather than as a string of anecdotes, ending a game by hitting into a triple play, unassisted or otherwise, turns out not to be the most portentous event to occur on August 23, 2009. Losing to the Phillies that day left the Mets, as a franchise, at 3,642-3,956, 314 games below .500. There’d be bad times ahead. Then good times ahead. Then a mix of bad times and good times. Add them all up, and the New York Mets wouldn’t again be as close to .500 overall as they were on August 23, 2009, for almost sixteen years.

But they got there on Sunday, June 8 of the current campaign, in Colorado.

The Mets had been working their way back from this moment for nearly sixteen years. When the Mets completed their season sweep of the Rockies by pummeling their asses with baseball bats, 13-5, it brought the 2025 Mets’ record — the one of most interest in the present day — to 42-24. The Mets lead second-place Philadelphia by 4½ and their other traditional nemesis, fourth-place Atlanta, by fourteen. The Nationals, who are in next at Citi, are the division’s third-place team, and their double-digits in back, too. Everything’s coming up Metsie, which you know if you watched them in Denver this weekend, particularly in the finale, which featured six Met home runs and a four-inning save. Two of the Met homers were off the bat of Pete Alonso, which gave the bat’s user 243 for his career, one more than Wright totaled, or second-most among all Mets ever, leaving him within nine of Darryl Strawberry for ownership of a glittering milestone. Veteran Jeff McNeil also hit two, with next-genners Brett Baty and Francisco Alvarez slugging the others. Juan Soto didn’t go deep, but he did reach base six times (three hits, three walks). Tylor Megill went five innings for the win. Paul Blackburn sopped up the rest to earn his first MLB save.

Even if we allow ourselves to remember the 12-53 Rockies are making the 40-120 Mets of 1962 look like the 108-54 Mets of 1986, it was still an impressive showing by an impressive 2025 Mets team. Five and two on the road trip. Twelve and three over the past two-plus weeks. And, in case you’re wondering, 1,216-1,216 following Francoeur’s liner into Bruntlett’s glove (and 4,858-5,172 since Richie Ashburn stepped in to lead off against Larry Jackson 47 years, four months, and a dozen days before that).

For the first time since the close of business on August 23, 2009, the Mets, as a franchise, are precisely 314 games under the break-even point. The losing that picked up steam as the 2009 Mets rolled downhill has finally been nullified. It’s not as if they’d been on a sixteen-year losing streak, exactly, but on a net basis, despite some legitimate spikes in the right direction, they lost more than they won over the course of 2,431 games, at no point winning more than they lost from August 24, 2009, forward and inclusive.

On the 2,432nd day, the Mets got it all back. They weren’t only clobbering the Rockies on Sunday. They were statistically kicking Francoeur’s ball out of Bruntlett’s glove. The ball is tricking into the outfield! The Phillies are phlummoxed! Castillo scores! Murphy right behind him! Here comes Frenchy!

Technically, the unassisted game-ending triple play remains on the books. Cosmically, the call has been reviewed and overturned.

In that table I keep, certain long-term inflection points have stood out, dates when we can see with hindsight that the Mets definitively stopped losing more than they won, or stopped winning more than they lost. The former is preferable to the latter. Both have happened and made their impact felt.

• Once they got it together in 1969, the Mets as a franchise relentlessly gained ground on their dismal beginnings until one day in June of 1972 when they would plateau without knowing it.

• Then, despite a memorable positive blip down the stretch in 1973, losing overtook winning for the long haul. More losing than winning became the overarching trend from June of ’72 through that September afternoon at Wrigley mentioned above as 1983 was winding down.

• From the ashes of 1983, until July of 1991, the trajectory pointed skyward, like it would pierce the clouds and never end.

• It ended; without warning, one loss became another and the historical progress that buoyed us reversed itself until nadiring in April of 1997.

• A long-term bounceback, encompassing high ups and low downs, brought the Mets to May 31, 2009, and that win against the Marlins when everything seemed fine and dandy.

• Time revealed everything in 2009 to be cruddy and miserable. A ten-season net-negative spiral — with two playoff spots and a pennant tucked within — ensued until the Mets had fallen 381 games below .500 on July 12, 2019.

• It may not have always felt like it on a continual basis these past six years, but the Mets have been on the rise ever since, going 456-389 between July 13, 2019, and June 8, 2025, which brings us to the present.

This has been a franchise in search of an enduring era for quite a while. A good era, of course. There have been good seasons since 2009’s darkness set in. There have also been dreadful seasons to make you forget how good the Mets have managed to be in relatively brief bursts. The composite record doesn’t lie. Across 64 seasons and counting, the Mets as a franchise haven’t sustained a winning record. Ever. They’ve never been at, never mind above, .500 as a franchise. It doesn’t matter within the confines of an outstanding individual season, but over time, it tells you something about what you’re spending your years rooting for and contributes to a sense of wondering what it’s all been for.

We are, this year, rooting for a team at the top of its game, a team continuing to rise, a team poised to shatter the grass ceiling of its checkered past. Its past, as illustrated in its all-time record of 4,858-5,172, indicates how hard it is for the Mets to win more than lose and keep winning more than losing. You never know when the losing will begin to prevail anew. You never want to know.

The best way to avoid knowing is to keep winning like the Mets have been winning.

METS LONG-TERM FRANCHISE UNDER-.500 INFLECTION POINTS

Most recently 1 game below .500: April 11, 1962

(Closest Mets have ever been to .500)

—

Most recently 277 games below .500: September 3, 1966

Most recently 278 games below .500: June 6, 1972

—

Most recently 283 games below .500: July 15, 1972

Most recently 284 games below .500: July 21, 1991

—

Most recently 296 games below .500: August 12, 1991

Most recently 297 games below .500: May 31, 2009

—

Most recently 313 games below .500: August 22, 2009

Most recently 314 games below .500: June 8, 2025

—

Most recently 381 games below .500: July 12, 2019

Most recently 382 games below .500: May 17, 1998

—

Most recently 403 games below .500: April 26, 1997

Most recently 404 games below .500: September 15, 1986

—

Most recently 503 games below .500: September 25, 1983

(Furthest Mets have ever been from .500)

—

NOTE: The longest active span of .500 baseball the Mets have played dates to August 28, 1967. The Mets have played 9,098 games since then and have logged a record of 4,549-4,549, including Sunday’s 13-5 victory over the Colorado Rockies.

by Jason Fry on 8 June 2025 9:27 am There’s a lot one could say about Ronny Mauricio‘s third-inning home run in Denver Saturday night, starting with the fact that it went 456 feet and came down in the third deck.

That’s … a long way. The third deck is a place where fans sit contentedly expecting not to be involved in the proceedings way down there on the field — in the replay from the camera behind home, the spot where the ball came down isn’t even in frame.

It was the longest home run hit by a Met this year … and Mauricio’s teammates, you will recall, include Pete Alonso and Juan Soto. And it’s not the first time Mauricio’s elbowed aside notable personages on the Hitting Superlatives leaderboard: In September 2023, his first big-league plate appearance yielded a 117.3 MPH double at Citi Field, the highest exit velocity recorded for a Met that season.

What struck me was that Mauricio has easy power. He doesn’t look like he’s swinging that hard — he uses his long arms to kind of flick the ball into the air, only to have it come down in another county. There’s a lot still to refine in Mauricio’s game — he chases too much and talk of his defensive versatility is a nice way of saying he’s not ideally suited to any position — but the bat speed and the easy power will carry him a long way.

Mauricio’s drive was the headline, but it had some company as the Mets shoved the Rockies aside: Jared Young and Jeff McNeil also homered, Brandon Nimmo contributed three RBIs, Luis Torrens tallied a pair and Francisco Lindor had three hits and two steals on a broken toe. (Long night for German Marquez, who came into the fifth having given up just one run but then saw everything come crashing down.)

The Rockies, meanwhile, had one of those quietly bad games that contribute to a terrible season without being particularly notable: plays not made, pitches not executed, bases not taken, games not won. Did Clay Holmes show admirable fortitude in allowing nine hits but just one run, or did the Rockies just fail to capitalize? Hey, why not both?

Anyway, the Rockies packed the house and so added bulk to Dick Monfort’s already bulky wallet, which is a Pyrrhic victory. At least they looked better in taking aim at their own feet: Those daiquiri City Connect 2.0s from Friday night are still branded on my retinas.

The Mets moved 17 games over .500, their high-water mark for the season (their high-water mark so far, says the optimist), and expanded their NL East lead over the suddenly flailing, battered Phillies to three and a half games. All good things ahead of one more game with Colorado and then a day off that should give the relief corps (newly expanded with the acquisition of two pitching-lab subjects in Justin Garza and Julian Merryweather) a badly needed breather.

Let’s not get ahead of ourselves, but maybe the Mets too can go a long way.

by Jason Fry on 7 June 2025 1:27 am The Mets played a strange game against the Greater Denver Daiquiri Machine Operators Local nine, who were sure spiffy in uniforms designed to look like the libations they serve so cheerfully. Oh wait, those were the Colorado Rockies, who inexplicably retired the best City Connects in the program and now look like human slushies. Their sub-.250 record is historically bad but my God, so are those uniforms.

The game was really two games in one: six innings of maddening frustration followed by three innings of madness.

The first six innings saw Kodai Senga give up just a solo homer to Mickey Moniak while trying to figure out which pitches he could make work a mile above sea level, though in the fifth he got an assist from Pete Alonso, who made a nifty throw home to nab Ryan Ritter — or at least he did once Chelsea overruled home-plate ump Chris Conroy’s safe call.

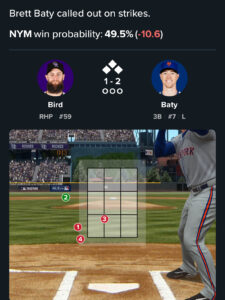

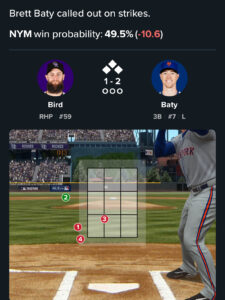

But the game went to the seventh with the Mets down 1-0, as they stubbornly refused to drive in runners in scoring position. The sixth was particularly infuriating: The Mets loaded the bases with nobody out against Antonio Senzatela and then Jake Bird on a pair of walks and a hit by pitch, or perhaps it was a near-HBP sold as one by Tyrone Taylor. But Conroy then added an inch or two to the outside corner, turning Brett Baty‘s AB into a farcical strikeout, and Francisco Alvarez and Ronny Mauricio then struck out against Bird without Conroy putting his thumb on the scale.

Seriously, if you can look at that GameDay snapshot and still not be on Team Robot Umps Now, I don’t know what to tell you. And an ABS system with challenges isn’t the answer — that will just slow games down and add another level of NFL-style bureaucracy to a game that used to be refreshingly free of it. Instead, implement a Hawk-Eye-style system and use it for every pitch, not just a selection of the home-plate ump’s most egregious failures. Every single game has ABs that are turned by umpires getting the strike zone wrong; sometimes that leads to tantrums like the one I’m currently throwing, but most of the time we don’t even notice, because we’ve accepted a certain level of inaccuracy and even sentimentalized it as “the human element.”

Which is nonsense. The human element is indeed a wonderful part of baseball, but it should be discussed when we marvel at clutch hits and heads-up plays and gutsy pitching performances, not when we’re hand-waving away the fact that umpires aren’t good enough at a critical part of their jobs.

Anyway, I was mad. Robot umps now.

Still, let’s not put all this on Conroy. He had nothing to do with Mauricio grounding out in the first or Alonso striking out in the third or Jeff McNeil flying out in the third or Alvarez grounding out in the fourth or Mauricio flying out in the fourth or Alvarez striking out in the sixth or Mauricio striking out in the sixth. The Mets were 2 for 15 with runners in scoring position on the night, that came on the heels of Thursday’s galling failure parade in LA, and it’s wearying to say the least.

But let’s talk about those two successes — and about the madness of the final three innings in Denver.

In the seventh the Mets put runners on first and second with one out, with Alonso digging in against slider specialist Tyler Kinley. Kinley had Alonso pulling off sliders off the outside corner but then missed his location on an 0-2 count, leaving a hanger in the middle of the plate. Alonso didn’t miss it, spanking it up the left-field gap to give the Mets a 2-1 lead.

Huascar Brazoban surrendered a run in the bottom of the seventh to let the Rockies tie it and in the eighth disaster seemed imminent: Ryne Stanek gave up a single to Jordan Beck and a double to Thairo Estrada, with Colorado third-base coach Andy Gonzalez inexplicably throwing up a stop sign as Beck came around third. Stanek then walked Hunter Goodman and had to face Ryan McMahon with the bases loaded and nobody out.

So of course McMahon hit a hard liner down the third-base line, seemingly ticketed for the left-field corner and two RBIs, maybe three. Except it thudded into Baty’s glove at third and he lunged to tag out Beck for an unassisted double play. Stanek then struck out Brenton Doyle and the Mets had somehow escaped the hangman. (A fun moment: a still-amped Stanek hugging Baty in the dugout afterwards.)

In the top of the ninth, Juan Soto singled and Alonso walked with one out against Zach Agnos. With two outs, Carlos Mendoza sent Francisco Lindor to the plate, broken pinkie toe and all. Agnos’s second pitch was a cutter that Lindor served down the right-field line, sending Soto home with Alonso chugging along behind him. Alonso looked like he’d be out by three feet, but pulled an okie-doke on Goodman, switching hands as he reached for the plate and getting in just ahead of the tag. (Conroy got that one right.) Lindor trotted off the field in favor of Luisangel Acuna, to be mobbed by his happy teammates, and Edwin Diaz offered a blissfully drama-free one-two-three inning to secure the win.

A classic? Let’s not overdo it, given the scores of runners left on base and the two-thirds of the game that was grinding and frustrating. But the Mets overcame the Rockies, the home-plate ump and themselves to win, and that’s pretty satisfying.

by Greg Prince on 6 June 2025 11:05 am Sure, it was horrible and painful like it was horrible and painful some 66 hours before, but at least it didn’t happen at one in the morning. So we had that going for us.

Otherwise, Thursday’s West Coast matinee beamed east with something approximating the atrocious ending that marred Tuesday’s late-night implosion. The revised edition encompassed some new wrinkles — Starling Marte getting picked off third; Brett Baty picking up a ball near third but not knowing quite what do with it once he did; Michael Conforto rising from the depths to luxuriate in a moment in the sun at the expense of his former employer — and some old standards. The Dodger bullpen (featuring spurned Unicorn shepherd Jose Ureña) went into shutdown mode. Met runners were stranded as if they’d chartered the S.S. Minnow. A steady lead became a sudden deficit became a loss that stuck deep in the craw.

From the Department of Small Favors. Dodgers 6 Mets 5 twice in three games takes some of the shine off splitting four in L.A., even if it doesn’t reverse the season series result that finished Mets 4 Dodgers 3. A once trivial note is now considered an essential edge. We saw last year what a tiebreaker can do for a team after 162 games. First, of course, there’s the matter of the 162 games. All caveats and superstitions implied, the portion the Mets have played of their full slate indicates the Mets will wind up in the same tournament for which the Dodgers maintain a standing reservation. This early-summer set-to felt more like a showdown between National League titans than a proving ground for us upstarts. We’ve made strides since the Sunday three Junes ago when we crossed our fingers tight and invested our faith within the intestinal fortitude of Adonis Medina. We’ve made strides since October of 2024 when their talent smothered our vibes.

We’ll take our chances most days/nights with a late lead in Los Angeles. We’ll take our chances with a torrent of hits and the likelihood they’ll turn into a sufficient quantity of runs. We’ll take a lump or two while a pinky toe (Lindor’s) or not as bad as it looked hamstring strain (Vientos’s) heals. We’ll move on and hope the craw specialists in Colorado can get our fleeting discontent from California removed without incident. The Rockies, however, just won three in a row in Florida, reminding us anything can happen amid 162 games.

We simply prefer only good happen. When such a state of perfection feels within reach, it’s jarring to remember the impossibility inherent in achieving that ideal. Coulda swept. Shoulda taken no fewer than three of four. High-caliber expectations resume despite two episodes of being brought temporarily low. As a baseball lifestyle, it’s the one to which you aspire.

Winning most of ’em is fantastic. Not winning ’em all will never not suck.

by Jason Fry on 5 June 2025 11:25 am We all love a dramatic game, but there’s nothing whatsoever wrong with winning 6-1 — particularly when that margin of victory comes the night after a gut-punch loss.

Wednesday night’s game was the Griffin Canning and Pete Alonso show, what with Canning’s near-flawless pitching (six innings, three skinny singles allowed) and the Polar Bear homering twice and driving in five.

Canning has never looked better as a Met, which had to be extra sweet considering he’s a California kid, had seen his star fall as a member of the little-brother team in town, and been pummeled in his only other Dodger Stadium start.

Canning kept the Dodgers off-balance all night, with a number of ABs standing out as showcases for his craft. In the first inning, facing Mookie Betts, he put four pitches in more or less the same location, down and in, but kept Betts off-balance by switching between his four-seamer, change-up and slider, culminating in a strikeout.

In the second inning, Canning simply dismantled poor Michael Conforto, who got a big one-year deal from the Dodgers that’s going miserably so far. (The Dodger Stadium crowds have been surprisingly gentle; in New York Conforto would have been booed back to Syracuse or into an asylum by now.)

And then the piece of resistance, as my late grandmother liked to phrase it: Canning vs. Ohtani in the bottom of the fifth. Recall that at this point the Mets led 3-0, which is perilously little against the Dodgers’ carnivorous lineup. Canning started his former teammate off with five straight sliders — a pitch he hadn’t shown him in previous ABs — and you could see the best hitter on the planet trying to regroup. (And possibly wondering, “Where was this Griffin Canning in Anaheim?”) Canning then switched from the outside of the plate to the inside, and from slider to change-up; Ohtani was frozen and had no chance.

Extra credit in the pitching department goes to Jose Castillo, another Mets reclamation project and one that’s yielded excellent results so far. In the seventh Castillo yielded a one-out double to Andy Pages (a dangerous hitter who somehow gets lost in this lineup) and hit Conforto with a pitch, bringing Dalton Rushing up as the tying run. Jeremy Hefner came out to the mound to unplug Castillo and plug him back in; the reliever responded by erasing Rushing and the loathsome Kiké Hernandez, fanning both on six pitches.

And then there was Alonso.

The Mets got off to a fast start against Tony Gonsolin — always welcome but particularly gratifying with the taste of Tuesday’s defeat still in the mouth. Gonsolin hit Francisco Lindor in the foot, then watched Kiké turn a Brandon Nimmo double-play grounder into an error. Nimmo stole second, a Juan Soto groundout brought in Lindor, and then Alonso demolished a first-pitch slider for a 3-0 lead.

That was fun, but the Polar Bear outdid himself in the eighth against luckless newcomer Ryan Loutos, redirecting a middle-middle sinker 447 feet into the pavilion. The Dodgers’ reactions were priceless: Behind the plate Rushing flipped his hands up in consternation; Loutos’ hands went to his knees before the ball cleared the infield; and Freddie Freeman stared into the void as Alonso trotted happily around the bases mugging and gesturing.

That was more than sufficient, making the ninth-inning homer surrendered by Ryne Stanek a cosmetic blemish. The Mets have now claimed the season series regardless of what happens in a couple of hours, and they’ve delivered a critical message we needed to hear after last October: We can play with these guys. Be not afraid.

by Greg Prince on 4 June 2025 1:30 pm Be glad that the first-place Mets compete on the same elite level as the first-place Dodgers.

Be glad that the Mets play close, compelling games versus the defending world champions.

Be glad the Mets can show up at Dodger Stadium and grab a quick 1-0 lead off future Hall of Famer Clayton Kershaw.

Be glad Tylor Megill can shake off a rough four-run first inning and go six without giving up anything else.

Be glad Juan Soto continues his extra-base hit streak.

Be glad Pete Alonso is driving in far more many runs this year than last.

Be glad Brandon Nimmo hustles down the line.

Be glad video replay review is not blind.

Be glad Kershaw isn’t quite in his prime anymore and can be chased before he gets out of the fifth.

Be glad Brandon Waddell is capable of more than soaking up spare innings of lost causes.

Be glad Waddell pitched well enough in the seventh to make one wish he had stayed in for the eighth, therefore saving Reed Garrett for the ninth and leaving the bulk of the recently deployed bullpen be.

Be glad Garrett pitches out of eighth-inning jams, especially when adequately rested.

Be glad Ronny Mauricio is healthy again and knows how to instigate a successful rundown between third and home.

Be glad Luis Torrens has the power to drive a ball to the wall as a pinch-hitter for a pinch-hitter for the designated hitter, a skill that might come in handy under more amenable circumstances.

Be glad Huascar Brazoban maintains the recuperative powers to strike out three consecutive batters after giving up a game-tying leadoff ninth-inning home run.

Be glad Soto and Alonso proved earlier in the game they are capable of markedly better at-bats than those they executed in the tenth.

Artist’s rendering of game-losing play. Be glad Nimmo has the perspective and articulateness to explain in detail and depth how a ball that dropped to the ground a few feet to his right in left — thus ending what instantly became a horrible and painful 6-5 loss — turned distressingly unplayable for an experienced major league outfielder who seemingly makes comparably difficult catches three times per month.

Be glad the Mets play close, compelling games against the Dodgers that would fit well in a postseason rematch between the two combatants.

Be glad this wasn’t a postseason game and therefore doesn’t carry an outsize impact on the Mets’ fortunes.

Be glad this game took place very late at night Eastern Time when relatively few people figured to be alert for its ending and even fewer figured to lie awake thinking about it too much.

Be glad there are more than a hundred games to go.

Be glad there’s another Mets-Dodgers game late tonight.

Be glad the Mets don’t lose in such horrible and painful fashion very often.

by Jason Fry on 3 June 2025 2:37 am It didn’t exactly strike me as the best idea for the Mets to play the Rockies at home, fly across the country and then go toe to toe with the Dodgers the next night, but MLB has an unbroken record of not asking me what I think.

That’s what the Mets did, and at least for once it was worth staying up after midnight, with the two clubs linking up for a taut, thoroughly satisfying game that ended up with the forces of good triumphant … albeit by the thinnest of whiskers.

Things got off to an excellent start, as Francisco Lindor hit the second pitch of the game over the fence for a 1-0 lead, made even sweeter by the fact that he connected off Dustin May, whom I’ve never been able to stand. May’s nimbus of red hair and oddly pale face remind me of Pennywise if that ghoul had taken up pitching instead of eating Maine children, and I recoil instinctively at the sight of him. I also dislike his histrionics — not because baseball ought to be dour and cheerless but because starting pitchers ought to know the karmic wheel that lifts you up this inning may roll over you the next.

The Mets led 1-0 and then 2-0 on a Brandon Nimmo double, with a third run denied them when the ball hopped over the fence for a ground-rule double, mandating that Francisco Alvarez be sent back to third. (I’ve never quite made up my mind whether this is a charming anachronism or a stupid rule that ought to be struck.) Meanwhile Paul Blackburn was razor sharp in his 2025 Mets debut, showing off a curve with a lot more bite than I remember from his brief 2024 tenure.

Blackburn departed after five and the Mets were left to figure out how to find 12 outs against the Dodgers’ relentless lineup. Huascar Brazoban was first up and quickly put the lead in jeopardy, giving up a single and a pair of walks and facing October tormenter Tommy Edman with the bases loaded and two out — and on Edman’s bobblehead night, no less. Brazoban got Edman to chase a changeup off the plate, the Mets had survived the first test, and I earnestly suggested Edman use his bobblehead to do something rude.

Next up in the securing of outs was Max Kranick. Balls were dying in the outfield all night, with Mark Vientos left in disbelief after a solidly struck ball barely reached the warning track and Tyrone Taylor looking like he was out there conducting a survey of the warning track, pulling balls out of the air all along his patrol area. (Taylor is more impressive every day, with his lightning-quick first step on balls to the gap turning doubles into long outs and difficult plays into ones that look routine.) But then Shohei Ohtani connected with a hanging curve offered by Kranick, and this one did not die — in fact, it’s probably coming down about now.

Kranick escaped further harm and Ryne Stanek navigated the eighth, with a scary-looking Max Muncy drive proving all trajectory and no oomph. And so the game came down to Edwin Diaz protecting a one-run lead against Edman and the bottom of the order, with Ohtani up fourth.

Edman singled, dismantling the hope that Ohtani might be left a forlorn spectator; with one out Lindor saved the lead by keeping a Hyeseong Kim grounder on the infield, but that brought Ohtani to the plate with the tying run on third and the winning run on second. Home-plate ump Andy Fletcher completely missed the first pitch, calling an obvious strike a ball; two pitches later Ohtani served a fastball down the left-field line, more than deep enough to tie the game but thankfully not deep enough to end it.

Diaz struck out Teoscar Hernandez to keep the game tied, the kind of development one welcomed provided the Mets somehow won, seeing how midnight was in the rearview mirror already. And in the 10th the Mets struck quickly, with an RBI double from Alvarez followed by an RBI single from Lindor. All hail the Franciscans! But the Mets couldn’t bring in a third run, with Vientos looking like he might have hurt a hamstring coming out of the batter’s box, and Jose Castillo was sent out to defend a two-run lead with the ghost runner poised to cut that lead to one.

Castillo looked a bit nervous, because of the situation or the enemy lineup or both, and it was hard to blame him. He walked Freddie Freeman, then surrendered a single to Andy Pages that cut the lead to 4-3, with Freeman on second.

Dave Roberts, strangely, left Muncy in against the lefty despite the three-batter rule ensuring Castillo had to face one more hitter; Muncy was enticed by a slider below the zone and struck out. Roberts then pinch-hit Will Smith for Michael Conforto (who’d already reached the plate) even though the Mets now could change pitchers.

They did, summoning Jose Butto to face Smith. Butto doesn’t always inspire confidence, but he got Smith on another long drive to nowhere, with Freeman moving over to third. But now Edman was up again. Butto’s fourth pitch was a slider that Edman spanked right back up the middle. If it got through Butto it might have found Luisangel Acuna‘s glove and Acuna might have had time to get Edman, but it’s more likely it would have found the outfield grass, with Freeman home and Pages on third and Edman bobbleheads being lofted happily all over Dodger Stadium and then oh boy.

But it didn’t get through Butto. He made a nifty play on it, tossed it to Pete Alonso and the Mets had won and we could all go to bed. Which your chronicler will now do posthaste.

|

|