The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 30 November 2019 4:18 pm A few years ago, Howie Rose suggested to Josh Lewin that if they were to go down to the field from the broadcast booth at Citi Field and ask the players warming up for that night’s game if they knew what day it was, most would have little idea because, Howie explained, ballplayers never have any idea what day it is, mostly because it doesn’t make any difference to them. Howie’s assertion was supported by Nationals beat writer Jesse Dougherty in the Washington Post this past summer. “The challenge,” Dougherty wrote, “is playing a 162-game schedule, with few breaks, while traveling between cities and time zones. The hotel rooms start to look the same. So do the plane rides and bus trips to the ballpark each day.”

Even though we who are watching have to keep track of the days of our lives, the perception described from the inside of baseball seems to make sense. For ballplayers and those who follow them around, the season is simply one day after another. Or night. The mostly infallible Gary Cohen’s only persistently recurring mistake is regularly referring to yesterday afternoon’s game as “last night,” which drives me a little crazy, but I’ve come to understand that tic, too. There’s a lot of blurring over six months. Wednesday. Thursday. Night. Day. None of it materially affects the outcome of winning and losing.

Besides, whenever Mets baseball is happening, I will most likely bear witness to it.

On Friday night, July 30, 2010, after sleeping through the previous day’s matinee from Flushing, I watched the Mets top the Diamondbacks, 9-6. It was a home game, so it wasn’t a challenge to stay awake. If the Mets were in Arizona, and it was a night game, it might have been. Mountain Standard Time, which isn’t a whole lot different from Pacific Daylight, can make keeping up with the Mets a bit more of a challenge than it is in zones closer to home. Usually not impossible, though. I’d have to be pretty tired to miss an entire Mets game.

For hundreds and hundreds of consecutive regular-season games, I was never quite that tired. Nor was I that distracted or disgusted or otherwise engaged so that every pitch of a given game escaped my notice while those pitches were progressing from the pitcher to the batter or catcher. I had quite a streak going. A handful of times it flirted with an end, but from July 30, 2010, through the eight seasons that followed and into the one beyond it, I always managed to stick an ear into the action just long enough to say, OK, I’ve heard if not seen or gone to today’s or tonight’s game. Streak’s still on. The closest I came to streak snappage occurred on August 18, 2014, when I mysteriously scheduled a Monday afternoon colonoscopy that coincided with a 12:10 first pitch between the Mets and Cubs. Fortunately, the medical people got to the bottom of things that afternoon before the bottom of the ninth of what became my 672nd consecutive game witnessed in one form or another.

My streak intact from that day forward, I wasn’t going to take another chance like that when my next colonoscopy came up. I set it for a Monday morning in May of 2019, with the Mets safely ensconced on the West Coast. As Sean Doolittle told Dougherty, “Every start of a series is a Monday, no matter what.” Actually, sometimes you get a wraparound series that goes Friday to Monday (like that one in August of 2014), but what the Mets were about to embark upon wasn’t one of those. They were indeed starting their next series that Monday, May 6, in San Diego. It was just another night game to the host Padres. It wasn’t going to start any earlier than 7:10 at Petco Park, 10:10 back in New York.

Colonoscopy 2.0 went fine. The procedure is never the issue. The preparation is where they get you. I had to start the prescribed regimen early the Sunday morning before, and that was on the heels of an eighteen-inning game in Milwaukee which felt like it ended five minutes earlier. I missed a bunch of that game from being sleepy. Thanks to Twitter and the MLB At Bat app, I was able retrace some steps I snoozed through and write the whole thing up without resorting to the dreaded WW (Phil Rizzuto’s scorecard notation for Wasn’t Watching). If “I missed ‘x’ number of innings” had seemed like an angle that would have optimally entertained, enlightened and informed you, I probably would have detoured from the main storyline and mentioned it. But an eighteen-inning game doesn’t need necessarily need angles imported from dreamland. Therefore, once I was more or less awake overnight that Saturday into Sunday, I filled in blank portions of the Mets’ 4-3 loss to the Brewers by availing myself of the archives on my iPad; pieced together the irritations of the long evening from commonly tweeted grievances about Angel Hernandez; and wrote up the game, not my fatigue. I figure if re-creations were good enough for Les Keiter in 1959, one posted here at 5:49 AM was good enough for me.

So there was little predawn sleep Sunday morning. Or postdawn. There was barely enough will to make it between colonoscopy prep steps to get to the 2:10 first pitch from Milwaukee. I curled up in my office recliner, watched about an inning-and-a-half of Jason Vargas dueling Zach Davies before conking out. When I awoke, I learned Vargas predictably dropped his pistol first, and the Mets lost, 3-2. I wasn’t writing up this game. I just wanted to be able to say I had seen some of it.

That, on May 5, 2019, was Game No 1,390 in the streak that stretched back to July 30, 2010. Game No. 1,391, live from San Diego, would come the next night. Except it didn’t. Following the aforementioned procedure, I didn’t nap. I was tired, but I was up. As the SNY studio show threw the broadcast to Gary Cohen and Todd Zeile, I was up. While I was up, I decided stretching out on the couch was a good idea. I wasn’t recapping this one, either, so I just had to get to the game’s beginning to satisfy my streak’s requirement. Catching a pitch would do it. Just one pitch. Hell, even if I nodded off, I just had to not stay nodded off for the entirety of the game ahead.

I saw Gary and Todd do their setup. I heard Gary promise they’d be back after this commercial break. During the commercial, I closed my eyes for a minute…

The next thing I saw was the postgame show. The streak that touched every season of this decade was over, bowing out at 1,390 games in a row: 671-719, but no longer counting.

For the record, the first Mets game I missed in nearly nine years was the temporarily infamous Chris Paddack Game. I guess that’s what it’s known as. I didn’t see it or hear it, so how the hell would I know, except for catching up to its details in the minutes thereafter? Apparently, the Padres’ young ace was steamed that Pete Alonso was named the National League Rookie of the Month for April rather than Chris Paddack. This was a private war Paddack was waging, one he brought to the mound this Monday night. Having found all the motivation he needed in a slight that was an issue probably only to Chris Paddack, Chris Paddack struck out 11 batters in seven-and-two-thirds innings, limited the visitors from the East to four hits and, with Craig Stammen, shut out the Mets, 4-0.

Not only did this Paddack fellow whom I’d never heard of throughout what he considered his stellar April exact revenge on his imagined rival, he got me good. Paddack and Stammen required only 2:14 to complete their victory. Had the game meandered like most games meander, I’d have been up and sufficiently at ’em in the wee hours to keep the streak going.

Nope. No dice. I couldn’t even pretend in my head that the Mets and Padres had somehow filtered into my subconscious. The Mets fell on the Coast and it didn’t make a sound to me. The best-laid plans of a man told to lay flat on his stomach the previous morning had gone awry.

I could do only one thing in response. The next night, I started a new streak, still in effect at 127 games. Why wouldn’t have I? Except for May 6, 2019; July 29, 2010; and maybe one game earlier in 2010 when I wasn’t keeping quite such close tabs on my diligence, I’d seen or heard or attended some if not all (but usually all) of every Mets game played in the 2010s. It was — out of some combination of obligation and passion — what I did. The Mets played, I was there for it. The streak was a thing for me in the way the snub was a thing for Chris Paddack. It didn’t really matter, but it added a little spice to what Chris Paddack and I would be doing on a given day or night anyway.

Because I absorbed live virtually every bit of the Mets decade that has just passed — and because I wrote up a whole lot of it as it went on — I feel I’m reasonably qualified to look back in something less than anger at these ten years, the 2010s, and put them in what we’ll loosely call perspective.

You didn’t ask me to, but it’s part of the service.

Not unlike days of the week, decades don’t exactly exist in baseball. There are innings that add up to games. There are games that add up to seasons. There’s a compressed postseason. And that’s basically it as far as determining who wins and who loses. Everything else is a matter of how we opt to organize. “The 2010s” holds no particular meaning for baseball any more than any other decade unless we decide it does. Those stats you occasionally run up against — most home runs hit in the 1950s (Duke Snider); most wins by a pitcher in the 1980s (Jack Morris) — are interesting, but hold no more significance than the most home runs hit in a ten-year span that crosses decade borders…and there’s no particular significance in who did what from, say, 1995 through 2004.

What have of the Mets of the past ten years done for us lately? Technically, everything. But we do get these decades every ten years, and we are stuck with these baseball voids every offseason, so what the hell? Thus, in the days and nights ahead, Faith and Fear in Flushing will bring you The Top 100 Mets of the 2010s, considering the 247 players who played as Mets between April 5, 2010, and September 29, 2019, and ordering what we shall refer to the “best” of them from 100 to 1, countdown (or countup) style.

The parameters aren’t too arduous. Rankings will be based on recollections and research, leaning on impressions and accomplishments more than stone statistical rigor. We’ll take into account what a player did and if it made us as Mets fans sit up and take notice for at least a spell, maybe no longer than a given day or night during the 2010s. Worth noting in this process: thirty Mets from this decade began their Met tenures prior to 2010, but we’re not allotting points based on anything anybody did before this decade began. Also, we’re not actually “allotting points”. Plenty of thought’s gone into this exercise, but there is no discernible Statcast-approved formula at work. Take the rankings as seriously or as frivolously as you like.

I’d love to tell you whittling down 247 players to 100 was a tough task. Honestly, it was more the other way around. Almost everybody seems to rank 30 to 50 places higher than you would intuit before delving into the ten-year roster. Still, I don’t mean to strike a dismissive tone. These 247 players were our guys within these ten years. If you missed no more than a couple of games over this period, you’ve come to think of them as extended family.

I was reminded of their status in our lives (certainly mine) the other night when I found myself watching a Mets Classic: July 20, 2011, Cardinals at Mets, the 157th game of my 1,390-game streak. SNY likes to rerun it all out of proportion to its competitive implications for the home team, I think, because it showcases SNY as much as it does the Mets. It was the first time that the channel sent Gary, Keith and Ron out to the Pepsi Porch to make their call. Two Met home runs would be hit in their direction, including the one that won the game for the Mets in the tenth, but the real fun emanated from interludes like watching Keith Hernandez tipping Orlando the hot dog vendor for his goods and services.

Yet rewatching it, I was taken by the familial aspect of the lineup. Cousin Jose Reyes leading off, leading the league in hitting and peaking as a major leaguer. Cousin Justin Turner batting second, playing second and beginning to show he belonged as a major leaguer. Uncle Carlos Beltran, his bags packed for the trade we understood as inevitable, around in right. Hey, it’s Daniel Murphy before he was fully Daniel Murphy to us! And look, it’s Angel Pagan all over again!

Angel hit the walkoff homer that fell just a little shy of the broadcast position in right, but the real revelation was remembering those nights and days when what Angel and an unproven Lucas Duda and a last-legs Willie Harris and an endlessly slumping and aching Jason Bay and a theoretically developing Josh Thole and that beguiling pre-celebrity knuckleballer R.A. Dickey and everybody else involved did mattered so much to us. Eventually, everyone from Reyes to Murph would morph into ex-Mets, and what the players who took their spots as Mets did would matter just as much to us. The successors to these individual 2011 Mets, whenever they showed up, whether or not their work was classified Classic, became the new members of our baseball family. That’s how being a fan works. You pull for the laundry, sure, but you get attached to those who pull on the shirts and pants of preference every night and day and toss them somewhere near a hamper afterwards. Decades and eras and seasons and games and innings are full of these Mets. You spend most nights and/or days with them half-a-year every year. They add up.

We’ll add up a hundred of them in this space, relive what made them relatively special to us, and maybe do a few other 2010s things as well before we get to 2020. I hope it’s as much fun as watching the Mets has been for these past ten years.

Check that. I hope it’s more fun.

by Greg Prince on 25 November 2019 2:24 am In the beginning, the Mets didn’t have to play youngsters. The Mets were a youngster, a toddler, the bouncing baby of the National League basement. No matter who they featured, the thinking went, they were going to be clumsy, so they might as well be familiar. Hence the 1962 Mets’ early reliance on daily lineups of veterans who’d been through the senior circuit wars of the 1950s: Hodges, Zimmer, Thomas, Bell, Ashburn, Mantilla, Neal, Landrith. Everybody there had played this game…and seen better days in it. “All the memories were in the past tense,” George Vecsey wrote, “and most of the talent was that way, too.”

A year later, it was the beginning of a different story, with eternal spring chicken Casey Stengel touting his Youth of America. Ed Kranepool had debuted the previous September at just seventeen, if you know what I mean. Ol’ Case saw him standing there in St. Pete and invoked a previous phenom who got his feet wet at the Polo Grounds: “Who says you can’t make it when you’re eighteen? Ott made it when he was eighteen.” Mel Ott also played until he was 38 and hit 511 home runs. While Eddie dealt with perfectly reasonable comparisons, it was Ron Hunt, 22, who was poised to become the promising newcomer of 1963. Hunt batted .272, took 13 pitches to his person, finished behind Pete Rose for NL Rookie of the Year honors and was about to be the baby face of the two-year-old franchise as it took its act from Manhattan to Queens in 1964.

There’d be push and pull between the young and the old (baseball old, that is) as the 1960s progressed and the Mets intermittently strove to field promise on a daily basis. As 1965 wound down, and Wes Westrum assumed the managerial reins from the reluctantly retired Stengel, he leaned on not just Kranepool and Hunt — each an All-Star already — but rookies named Ron Swoboda (21), Bud Harrelson (21) and Cleon Jones (23). “We’ve looked at old players for four years,” Westrum reasoned, with another triple-digit sum of defeats staring him in the mirror. “We’ve got nothing to lose giving the kids a chance.”

Come 1966, the Mets would rise above tenth place and lose fewer than a hundred games for the first time in their history. It was about time. It was also about experience. Westrum’s key kids included Roy McMillan, 37; Ken Boyer, 35; Ed Bressoud, 34; and Chuck Hiller, 31. On the other hand, Jerry Grote, the new catcher, was all of 23, and Kranepool, 21, was still getting the hang of voting. Grote and Kranepool, like Swoboda, Jones and Harrelson, would be sticking at Shea Stadium beyond 1966, while those aforementioned veterans would all be gone before 1968.

The same fate that befell Boyer, et al, however, awaited Hunt, who sure appeared destined to star at Shea for years to come. Ron was traded with Jim Hickman to Los Angeles for Tommy Davis. Davis, a two-time batting champ, wasn’t exactly ancient when he took over left field at Shea in 1967, but he had miles on him; like Hunt, an injury struck him in 1965 and, like Hunt, his career never looked quite the same. After one solid year for the tenth-place Mets, Tommy, 28, was swapped to the White Sox for a Tommie — Agee, that is — plus Al Weis. Agee, 25, had very recently been the AL Rookie of the Year.

You never know how the demographics will coalesce on a given diamond or in a given era. The story of 1969, which nobody knew was having its preface penciled in as early as 1962 when Master Melvin’s successor Steady Eddie was taking his first swings, is one of kids coming together to take a division, a league and a world by storm. There’s no overlooking the mentorship and big hits provided by the veterans — Weis, Ed Charles and Donn Clendenon all effectively platooned for Gil Hodges from the other side of 30 — but we revel in the image of the Youth of America in full bloom. The young pitchers obviously mattered momentously, but at the core of the so-called miracle were those position players who were once prospects and who were now becoming champions. They all took the field together on the afternoon of October 16, 1969, and all ran for their lives from a grateful throng a couple of hours later.

Ed—24

Tommie—27

Bud—25

Cleon—27

Ron—25

Jerry—27

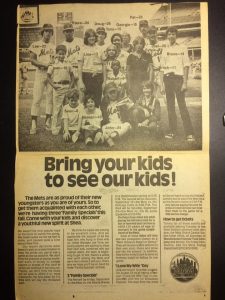

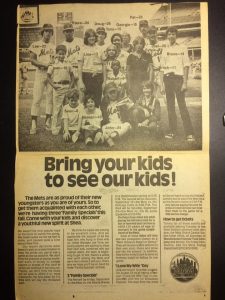

Even when the blossoming is slow to reveal itself, youngsters growing into winners is an ideal we all hope on. In the Mets’ darkest days, the late summer of 1977, the team’s marketing department, such as it was, went there. It went to the kids. It went to Our Kids, as in the Mets begging parents across the Metropolitan Area to “Bring your kids to see our kids!” The unironic newspaper ad copy wanted us to forget that so many of our former kids were no longer our vets, so it preached promise.

The Mets are as proud of their new youngsters as you are of yours. So to get them acquainted with each other, we’re having three “Family Specials” this fall. Come with your kids and discover a youthful new spirit at Shea.

The you gotta be kidding pitch has M. Donald Grant’s nefarious fingerprints all over it, as the ad attempts to explain away “trades we felt we had to make” in the name of keeping prices down. In addition to losing ballgames and fans at a rapid clip in 1977, the Mets were also lagging in prescience: “We don’t think the practice of paying exorbitant sums of money to certain players in excess of that paid to others will continue in the long run.”

Yeah, good luck with that, Don.

The brighter point of the advertising campaign was to claim “the trades are proving to be excellent ones […] under Manager Joe Torre, our young players are starting to show their stuff and, combined with our veteran talent, the team is beginning to gel.” The best of the veteran talent had been shipped off on June 15, but the ad preferred you focus on the youngsters who composed the big picture — literally the big picture at the top of the ad, an intermingling of young Mets and younger Mets fans. The bigger kids were helpfully identified by first name and age.

Lee—22

Steve—24

Doug—26

Pat—25

Joel—25

John—24

Also pictured: Lisa, Tony, Georgie, Bruce, Ivan, Cindy, Robert, Sylvia, Brock, Sean and Noreen, who ranged from six to fifteen. Those were “your kids,” the ones adults buying a full-priced box or reserved seat were invited to bring along for free to those Family Specials. The attraction was “Our Kids”: Mazzilli, Henderson, Flynn, Zachry, Youngblood and Stearns, five of them getting a chance to play every day and one tasked with pitching every fifth day. Unnoted in the invitation, but certainly implicit, was a chance to get another glimpse of Ed Kranepool, by then a Met forever, yet only 32 in people years.

Hard to believe this didn’t work. (Image courtesy of the Will in Central NJ archives.) Did anybody actually bring their kids to see the Mets’ kids because the Mets strongly suggested it would make for a fabulous family outing? According to Baseball-Reference, attendance did not noticeably tick up on the first two promotional dates, while the third was rained out. Attendance kept plummeting in 1978 and 1979, two more years when the one thing the Mets couldn’t advertise was winning baseball. By the time the Mets got good again, none of Our Kids from 1977 had much of anything directly to do with it.

But there would be new kids. There usually are. Come 1984, the kids dotting Met lineups would be named Mookie and Hubie and Wally and Darryl (not to mention a few kid pitchers of note). More such kids would be coming soon, as would be a torrent of paying customers impressed not by slogans and specials but hits and runs. These kids of the early ’80s would blend with some imported elders of renown — including that once-young Mazzilli fellow, reborn in grizzled veteran form for a second Flushing go-round — and the 1986 Mets would create history.

Over the next thirty-odd years, the Mets would attempt to re-create not only that kind of championship result, but that kind of incredible chemistry. The push and pull of young and old continued apace. Sometimes all ages meshed. Other times every Met in sight seemed to be born too soon or have matured too late. With the exception of occasional outliers — Jose Reyes came up at 19 in 2003; Julio Franco hung around until he was 48 in 2007 — you didn’t necessarily notice whether your Mets of any particular year seemed particularly young or especially old.

In 2019, you noticed.

In 2019, the Mets had veterans. In 2019, the Mets had pitching. But mostly in 2019, the Mets had a youthful core throughout the infield and within the outfield. That core defined who the Mets were as a team and what we as Mets fans felt about the team. This is why Faith and Fear in Flushing is presenting its 2019 Nikon Camera Mets Player of the Year award — dedicated annually to the entity or concept that best symbolizes, illustrates or transcends the year in Metsdom — to the latest edition of Our Kids.

Pete—24

Amed—23

J.D. — 26

Jeff—27

Michael—26

Dom—24

Brandon—26

Together, this cluster of seven position players generated an energy and emitted an aura that made rooting for the Mets fun for fans of all ages.

One great big clusterfun.

Funny thing is I don’t think we even realized we are were at the tipping point of a youth movement as 2019 approached. Sure, the game was getting younger and perhaps cheaper from the perspective of clever front offices everywhere; youth was definitely being served, service time manipulation notwithstanding. And sure, our talent pool included three former No. 1 picks; a former prospect who had only a couple of years earlier landed in the upper echelon of everybody’s projections; a slugger who led the minor leagues in homers the year before; an infielder who batted .329 in an extended audition upon his late-July 2018 callup; and a castoff from an organization that mostly developed studs. With hindsight, the pieces were there. It just hadn’t occurred to us to put them together in advance. It probably hadn’t occurred to the Mets, either.

By the end of the season, they were the Mets more than any Mets were. Granted, those seven Met kids — one more than the Bradys, one fewer than the Bradfords — had help throwing their party. Certified veterans Frazier, Cano and Ramos. Pitchers-in-their-prime deGrom, Wheeler and Matz. Journeyman cameoists Gomez, Altherr and another Davis. That’s how teams that win more than they lose work. Yet over 58 seasons of Mets baseball, I’d be hard-pressed to name another reasonably successful edition whose essence was so vastly defined by its youthful core of position players. 1969 had Seaver and Koosman. 1986 had Hernandez and Carter. 1999 and 2000 had more guys who’d been around than hadn’t. 2006 and 2015, too. All of those guys from all of those years were wonderful. The guys we’re talking about from 2019 were different. Wonderful, but different in composition and as a critical mass.

It would be a blast to report that the kids who elevated our mood from the middle of July to the end of September had a 1969-style ending to their season, but we know they didn’t reach October. It would be most photogenic had they all been gathered together and preserved for posterity the way the wishful-thinking class of ’77 had been, yet the seven of them didn’t even congregate in the same box score after May 16. The closest we had to a “Bring your kids…” treatment was a commercial run on SNY for Beanie Night in September. Pete Alonso, Amed Rosario, J.D. Davis, Jeff McNeil and Michael Conforto each wore the pom-pommed winter hat the club was giving away, their smiling faces popping up in boxes like they were Mike Nesmith and the rest of the Monkees, monkeying around like it was 1966. Chances are the Mets kids needed to have the retro concept explained to them (The Monkees having completed its last revival on MTV well before any of these players were born), but whoever came up with the concept certainly captured the zeitgeist of this moment in Met time.

Except Brandon Nimmo and Dom Smith weren’t included. Nimmo had been injured most of the summer and Smith was on the IL. Players who are hurt apparently can’t sell hats. By the time Smith was activated and putting a signature on the season’s conclusion with his walkoff home run of September 29, McNeil was sidelined with a fractured right wrist. Mickey Callaway or whoever dictated lineups to the former manager never thought to cooperate, either, as these seven Mets didn’t once trot out to their positions to start a game. Blame lefty-righty matchups and the stubborn incumbency of a couple of vets who were slow to cede claims to their spots on the field.

Yet when we see 2019 in our memories, once our memories enter the serious past-tense stage, we will see these kids together. We will remember their assorted individual accomplishments, natch, but we will feel what they brought to the Mets. The zeitgeist and zest. The vim and vigor. The exuberance that, like the exuberant, never quit. Shirts ripped from one another in exultation. Repeated declarations of resilience embodied in the actions of the inevitably half-clad resilient. A guy on a scooter racing out to embrace a guy called Scooter. Acronyms updated and hashtagged. A Polar Bear, a Solar Bear and a Squirrel. Second halves that were more than twice as good as their predecessors. Two of the young men officially named All-Stars at midseason; two others named theoretical All-Stars for what they did the rest of the season. Shouts about “that New York swagger” and “that New York attitude” in the wake of another New York win. Youth too young to understand their chances to contend had dwindled to practically nil, while experienced old heads watching from a distance drew overly hasty conclusions that it was not too soon to call it a year. Our Kids were impatient to win, yet demonstrated more patience than we did that they eventually would.

As fans we don’t proof at the door. Did we mind, even amid the “don’t trust anybody over thirty” mindset of 1969, that Weis, Clendenon and Charles were older and established when they arrived among us? Did we care in 1999 that Ventura, Piazza and Olerud, to name three, had all come from elsewhere and were each over thirty when they were joined by Rickey Henderson and Orel Hershiser — 40+ California legends — to put us over the top and get us into the playoffs? Is McNeil, 27, necessarily a kid? Is Conforto, who played in the 2015 World Series, not already a veteran? Wasn’t Davis technically a member of those paragons of virtue, the 2017 Houston Astros, before any of us took full note of what a gift those recent world champions had sent us?

Sometimes not everything can be dated via precise chronology or measured by tenure. Sometimes we just know and we can be comfortable fitting who see fit in those boxes we create. Yes, McNeil, an All-Star in his first full season in the bigs, is one of Our Kids. Yes, Conforto, an All-Star in 2017 like Kranepool was an All-Star in 1965 — because the Mets had to have somebody designated as such — was still coming along as 2019 got going. Yes, Davis, a bit player on a potential dynasty maybe too smart to comprehend all its assets, had to come to New York from Houston to let his freak swag fly…as did Grote 53 years before.

Alonso we had a clue would hit ’em out of the park, though we had no idea he’d hit more than anybody else, wind up speaking on behalf of everybody quite often and winning everything a rookie can win. Rosario we were thinking would have to move to center, but that was before he truly got the hang of short and hit nearly 60 points better in the second half than he did in the first. Nimmo reminded us what the happiest man in baseball looked like when he returned in September, whether it was sprinting to first on walks or doing sponsored self-parody; seriously, check out Brandon’s interpretation of Pete’s #LFGM. And Smith, whose stock plunged the minute his alarm didn’t go off to start Spring Training the year before, couldn’t have been more alert to his opportunity when this year ended (he also outlasted the manager who fined him for sleeping late).

What a difference a spring, a summer and a hint of autumn make. Dom, referring to what made these kids these kids and this team this team the last time this team would be exactly this team, told Steve Gelbs, “This group from Spring Training, we grinded together, we vibed in the locker room and we had a lot of fun. We wanted to change the culture here, we wanted to have fun and we wanted to win ballgames.”

That he said it drenched from a Gatorade bath only lent credence to Dom’s words.

Yes, this was our youthful core. Yes, they were a delight to take in as a unit. Yes, the method by which they evinced enthusiasm for one another could come off as a little anathematic for those who identify as old school, but the Mets are traditionally one step ahead when it comes to being excited for themselves, each other and us. Watch footage of the 1965 Dodgers heartily shaking hands when they won the seventh game of the World Series and compare it to how the Mets greeted one another in similar circumstances four years later. Follow the evolution of the high-five and curtain call as both came to represent the Met way in 1986 and consider how silly the rest of the league sounded when griping that it meant the Mets were arrogant. Search for images of when David Wright (2006) and Daniel Murphy (2015) waved fan-made signs celebrating divisional titles. The 2014 Mets, who didn’t win much, got the most out of every home run, simulating a dugout car wash under the supervision of the very veteran Curtis Granderson.

Your smileage may vary, but with all that ebullience as precedent, the tearing of jerseys and the injection of an extra letter into LGM is simply Met evolution in action. We don’t know what they’ll do for an encore. We just hope their future achievements provide the motivation to go suitably nuts.

We don’t know a whole lot of what will come next. We don’t know that this group will stay together and improve together. We want them to keep blossoming, keep blooming. We want to tell them, “OK, bloomers,” in the best sense possible. In our dreams, we might place Alonso at first, McNeil at second, Rosario at short, Davis at third, Smith in left, Nimmo in center and Conforto in right on March 26 and let them ride.

Yet they’re probably not going to make up seven-ninths of 2020’s Opening Day lineup. There’s a decent chance a segment of the seven won’t be with us next year. Trades of young players do happen, sometimes for the ultimate better. Hunt wasn’t here in 1969, but Agee, one trade removed from Hunt-for-Davis, was. We missed Hubie Brooks after 1984, but we were pretty darn delighted to have Gary Carter in 1985 and ’86. Dom Smith, his efforts at acclimating to left field notwithstanding, doesn’t really have a position, not with Pete Alonso having set up shop at first for, we pray, the next decade or two. J.D. Davis’s versatility isn’t quite as agile as Jeff McNeil’s. The Mets could use a legitimate center fielder, a catcher who every pitcher is comfortable throwing to, a fifth starter and bullpen reinforcements. To be distressingly businesslike about the whole thing, chips are chips. The team of our dreams is yet to be determined. It may or may not include those we came to love in 2019. If it does, we can’t be certain that the blossoming and blooming will continue unabated. We can project everybody’s prime all we want and be no more prescient than M. Donald Grant was about the trajectory of player salaries. We’ve been crossing our fingers and hoping for the best since Ed Kranepool. We don’t usually get Mel Ott.

Still, you’ll take what we’ve been given and build on it if you can. You’ll take more of Alonso going deep dozens of times; of McNeil throwing out a runner at the plate from right; of Davis magically sticking his glove out in left; of Rosario reminding you, oh yeah, he was supposed to be this good; of Conforto once and for all consistent beyond the doubt of all but the most cynical; of Nimmo working counts to perfection; and more of Smith loving being a Met like he did in the minutes after he gave us additional reason to love being Mets fans.

“It wasn’t about me, it was about this team,” Dom told Steve Gelbs after his eleventh-inning three-run home run beat the Braves in Game 162, which was merely his first at-bat in more than two months. “You know, we grinded all year, we fought all year, and we showed so much…”

After he was interrupted by a Gatorade bucket’s contents, he continued: “That just shows the character of the clubhouse. Twenty-five guys who came in every day, we grinded everyday, we worked hard. Obviously we didn’t get to where we wanted to go, but this is the start of something great.”

Again, we can only hope. But why wouldn’t we? After that night Conforto beat the Nationals? After that night Davis beat the Indians? After those nights Nimmo and Alonso waited out opposing pitchers to win via walks? After everything McNeil and Rosario did as their youth morphed into truly valuable experience? After Smith put an exclamation point on the remnants of a stretch run that made us believe the most unlikely of in-season comebacks was possible?

That circle of celebration on September 29, wherein nobody in or soon to be out of uniform was unexcited to be young, old or otherwise and a Met…the home run belonged to Dom, but the vibe that informed the euphoria clearly emanated from the entire youthful core. Dom and Michael and Amed and Pete and Brandon and Jeff and J.D. It felt like the curtain call for what they had brought us in 2019 and a sneak preview of what they might bring us in 2020.

Worst-case scenario, we’ll always have the memories they made.

FAITH AND FEAR’S PREVIOUS NIKON CAMERA METS PLAYERS OF THE YEAR

2005: The WFAN Broadcast Team of Gary Cohen and Howie Rose

2006: Shea Stadium

2007: Uncertainty

2008: The 162-Game Schedule

2009: Two Hands

2010: Realization

2011: Commitment

2012: No-Hitter Nomenclature

2013: Harvey Days

2014: The Dudafly Effect

2015: Precedent — Or The Lack Thereof

2016: The Home Run

2017: The Disabled List

2018: The Last Days of David Wright

Coming soon: The Top 100 Mets of the 2010s.

by Greg Prince on 17 November 2019 2:42 pm Tom Seaver is 75 years old today. We join the multitudes of baseball fans in wishing him a happy birthday and a happy day every day. We miss him. He’s still with us in the most elemental sense, yet we wish he could assert his presence like he did not so long ago.

A ceremonial first pitch.

An inning of erudition in the booth.

A lordly wave of acknowledgement to the sun-soaked masses while taking his shaded seat on stage at Cooperstown.

A story shared about what it was like on the mound; in the clubhouse; in the manager’s office; out to dinner after the crowd went home from Cooperstown.

A quote here or there disapproving of contemporary pitch-counting or talking up the current grape crop in a favored columnist’s copy.

All of this was Tom in the mid-November of his public life, before we realized his immortal’s emeritus phase, which we just assumed would go on and on, was about to go dark. Tom is still with us, but he used to be with us a whole lot more.

As gratifying as it was for 2019 to be graced by a golden-anniversary celebration of the 1969 Mets, you couldn’t in your heart swear it was wholly satisfying. That’s not the fault of those who joined us to celebrate. You loved hearing from Shamsky, from Swoboda, from Gaspar (every right fielder released a book this year) and from everybody else. It was a team effort, both capturing the championship and commemorating it anew. Still, you missed 41. You missed others, too. You wished everybody could have been both alive and well. You yearned for Tom most of all. You couldn’t help it. He’s Tom Seaver. Not was. Is.

He always will be. He always will be 41. Always the Opening Day starter. Always the man whose spot doesn’t get skipped because of rain. Always on call when others are taking an All-Star break. Always the one who expects to be on the mound in the eighth and ninth and the tenth if necessary. Always the one to keep himself in the game because he can handle the bat and run the bases. Always shaking his catcher’s hand for a job well done. Always atop the pitching totals in the Sunday paper. Always the one we look for this time of year, right around his birthday as it happens, to show up in the Cy Young point totals, first or darn close to it. Always a world champion among World Champions.

The greatest of pitchers. The greatest of Mets. Always. Still.

Happy 75th, 41. We are with you.

by Greg Prince on 14 November 2019 1:34 am Every time you turn around these days, some Met is winning some big award. These are good days.

Monday, it was Pete Alonso, National League Rookie of the Year (plus FAFIF’s MVM the next morning). Wednesday, it was Jacob deGrom, National League Cy Young. The latter was a case of Shéajà Vu all over again, of course, as Jacob is a repeat winner. Two years, two Cys.

These are good years, too.

Pete’s award was bestowed one nod shy of unanimous and it was a bit of an outrage. Jake’s second Cy came with exactly the same percent of assent — 29 first-place votes out of 30 —and it was fine. More than fine. Most of the season, the smart money was on Hyun-Jin Ryu of the Dodgers. But then the rest of the season got pitched, and down the stretch, nobody delivered like our Jacob. He was pretty good in the middle, too. Really, except for a short, baffling stretch earlier when batters briefly figured him out, Jake was generally great. Maybe not as great in 2019 as in superstupendous 2018, but greatness eventually reveals its truth.

Remember that game on September 9 when eternally lovable Wilmer Flores came back to town as a Diamondback, winked at deGrom from the batter’s box to start the fifth, and took his former teammate deep? That was adorable. That was also it as far as Jake giving up runs in 2019. Not just that night, but for the rest of the year. His final three starts were each composed of seven shutout innings. His final eight starts (and twelve of his last thirteen) were comprised of seven innings apiece — the contemporary conversion rate for nine. An ERA that brushed uncharacteristically close to 4.00 when May concluded settled in at a spiffy 2.43 when all was Cy’d and done.

The Mets have now collected seven plaques bearing the name of Mr. Young, or as many as any National League franchise since the advent of divisional play. Three went to Tom Seaver, albeit none of them in a row. Doc Gooden earned one in intensely memorable fashion, as did R.A. Dickey. Jacob deGrom has scooped up a pair and stands eligible to add on. Jacob deGrom is also signed long-term to stick around. We can’t say what his future holds, but we can depend on it being here, and we wouldn’t wager against it continuing to yield splendid results. Getting to watch this coolest of customers pitch every five days for the next five years (pending player and club options) should be its own award.

The best pitcher in the league one year. The best pitcher in the league the next year. The years have voted and the Jakes have it, two out of two. Unanimous enough.

by Greg Prince on 12 November 2019 10:41 am This starts as a story of incrementalism in action, or the inaction of incrementalism, and how what had been the case practically forever was suddenly no longer the case at all. To appreciate how spectacular the eventual great leap forward in question was, we shall travel back, as we so often have in 2019, to 1969.

You shouldn’t mind. It was a very good year.

Of all the moments that live on in collective memory from the Mets’ magnificent 1969 season, the top of the seventh inning at Dodger Stadium on September 1 isn’t one of them. Little wonder, in that the game was pretty much a lost cause from the bottom of the first on. After being staked to a 2-0 lead, Jerry Koosman imploded, facing five batters whose efforts resulted in four earned runs. By the end of the first, the Dodgers led, 5-2. Come the seventh, L.A. was ahead, 9-4.

Yet what the second batter in the visitors’ half of the inning did put an end to an era that likely not even the most data-driven Mets fan of that pre-analytics period knew existed. Tommie Agee, up with one out, drove a pitch from Jim Bunning out of the ballpark for his 23rd home run of the season. Everybody who cared about the Mets cared only about making up ground on the Cubs, something the Mets didn’t do in that Labor Day matinee. The eventual 10-6 defeat at the hands of the Dodgers cost the Mets a half-game in the standings, leaving them at 76-55, 4½ back of Chicago with 31 to play. It also lowered Koosman’s won-lost record to 12-9.

You know the Mets wound up winning 100 of 162 games in 1969, so a little math suggests this game was barely a speed bump on the road to ultimate glory. You also know after a half-century of paying attention that Koosman’s final mark fifty years ago was 17-9, thus we can ascertain Jerry’s case of the Mondays had no effect on his pennant-drive performance, except perhaps to motivate him to go 5-0 the rest of the way; each of those five was a complete game victory, three of them were shutouts, and the one on September 8 — in which Kooz brushed back Ron Santo — is a verified legend. Perhaps you know that Agee, who also stole two bases on September 1, hit 26 homers in all in 1969. With the fiftieth anniversary of that golden season in the books, you surely know it was Agee who was brushed back by Bill Hands on the Eighth of September, precipitating Koosman’s response at Santo’s expense.

But what do you know about Agee’s 23rd homer, other than what is mentioned above? Well, know this: When Tommie hit it, it narrowed the gap between the most prodigious home run-hitting seasons by a Met from 12 to 11. Until September 1, 1969, with Agee sitting on 22, Tommie trailed Frank Thomas’s team-record total of 34 by a dozen. Agee had hit No. 22 on August 21, at Shea, versus Ron Bryant of the Giants. He hit No. 21 on August 19 in the bottom of the fourteenth to beat Juan Marichal and San Francisco, 1-0. That one is a legend because it beat a future Hall of Famer, broke up an extraordinarily lengthy dual shutout and added to the mounting evidence that the 1969 Mets were a very serious enterprise.

No. 21 also had the distinction of adding up to the second-most prodigious home run-hitting season by a Met. Agee surpassed Charley Smith’s total of 20 from 1964. Until August 19, 1969, Smith was the runner-up in the then-thin Met record books’ even thinner chapter on dingers. It went Thomas 34; Smith 20; and everybody else 19-or-under. The gap between largest and second-largest quantity had been 14 for five years. When Agee went deep to start September, the difference had dropped beneath 12. We’ve made that clear already.

But why are we dwelling on this? Because of the following:

• When Agee finished 1969 with 26 home runs, the gap between best and second-best single-season Met home run totals was reduced to eight: Thomas 34; Agee 26. That remained the order of things through 1974.

• When Dave Kingman set up shop at Shea in 1975 and popped 36 home runs to establish a new Mets single-season record, the order was overturned and the gap shrank: Kingman 36; Thomas 34.

• A year later, in 1976, Dave topped himself by one: Kingman 37, Kingman 36.

• Six years later, in 1982, Dave tied himself: Kingman 37; Kingman 37.

• After a half-decade pause, a new champ announced his presence with authority. Darryl Strawberry set the new Mets home run mark in 1987 by two: Strawberry 39; Kingman 37 (twice).

• Straw would match his best in 1988, leaving the top two Met home run-hitting seasons as Strawberry 39; Strawberry 39.

• Then, in 1996, emerged a man in full — a catcher named Todd Hundley — to upend the top of this chart: Hundley 41; Strawberry 39 (twice).

• Between 1996 and 1999, something that seemed incredibly unlikely happened. Hundley, the toast of Flushing, was replaced behind the plate by all-world All-Star Mike Piazza. Piazza couldn’t quite usurp Hundley’s most cherished record, but he did take the 2 spot in the single-season home run standings from Darryl, just as he had taken the 2 spot in the lineup card from Todd: Hundley 41; Piazza 40.

• Seven years later, however, it was Piazza who was nudged aside. Carlos Beltran equaled Todd Hundley’s Mets-best total in 2006: Hundley 41; Beltran 41.

For the longest time thereafter, nobody challenged Hundley’s 41 or, for that matter, Beltran’s 41. All that incrementalism that followed in the wake of Agee moving within 11 home runs of Thomas on September 1, 1969…

Thomas by 8 over Agee at the end of 1969;

Kingman by 2 over Thomas at the end of 1975;

Kingman by 1 over himself at the end of 1976;

Kingman tied with himself at the end of 1982;

Strawberry by 2 over Kingman at the end of 1987;

Strawberry tied with himself at the end of 1988;

Hundley by 2 over Strawberry at the end of 1996;

Hundley by 1 over Piazza at the end of 1999;

and Beltran tied with Hundley at the end of 2006

…added up to little in the way of fundamental change at the top of the Mets’ single-season home run leaderboard. The record that was 34 in 1962 inched up to 41 thirty-four seasons later and remained stagnant for twenty-two seasons beyond that. There was, for thirteen years, no daylight between the top two power campaigns in Mets history, and for almost exactly fifty years, the difference between the top and next-to-the-top had never measured a distance as vast as a dozen home runs.

Then along came Pete Alonso.

Pete came, Pete saw, Pete conquered.

Pete came and kept coming.

By the time Pete Alonso finished arriving, he grasped everything within his expansive reach. The last two items that were up grabs in 2019 have just now become Alonso’s as well.

First, as voted on by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America and revealed Monday night, Pete is the National League Jackie Robinson Rookie of the Year, winning the award almost unanimously over a strong freshman slate that, honestly, didn’t seem particularly imposing by comparison to the man known popularly as the Polar Bear. Twenty-nine voters out of thirty listed Alonso atop their ballots; a lone misguided soul strained for a reason to stand apart from his colleagues and placed Pete second (there’s one in every crowd). Lack of unanimity notwithstanding, Alonso is the sixth Met to win the BBWAA’s NL ROY, following in the hallowed footsteps of Tom Seaver in 1967, Jon Matlack in 1972, Darryl Strawberry in 1983, Dwight Gooden in 1984 and Jacob deGrom in 2014.

Second, though not least by our reckoning, Pete Alonso is Faith and Fear in Flushing’s choice for the Richie Ashburn Most Valuable Met award. Pete is the second rookie in the fifteen-year history of the award to earn FAFIF’s official kudos, joining Jacob deGrom, who was so recognized by us five years ago. Pete also breaks deGrom’s recent stranglehold on the Ashburn, an honor the pitcher took home in 2017 and 2018. Alonso is our first position-player MVM since Asdrubal Cabrera in 2016 and the first full-time first baseman to receive the nod.

Pete Alonso, you might have heard, socked 53 home runs in 2019, the most of any major leaguer in the past season; the most of any rookie in any season; and 12 more than any Met before him. Outhomering the field was outstanding. Elbowing aside every erstwhile freshman was appreciated. But the complete renovation he undertook of the Mets annals was utterly astounding.

The Met rookie records are practically all Alonso’s: hits, extra-base hits (he has the overall franchise record there with 85), runs, runs batted in (120, tied for third-most among Mets in general), total bases (348, another team mark), at bats, plate appearances, games played, slugging percentage, on-base percentage…though he only tied Ike Davis and Lee Mazzilli for most first-year bases on balls with 72. The rookie home run record, of course, also belongs to Alonso. It used to be held by Strawberry, with 26. That seemed like a lot in ’83. It seemed like a lot until ’19. Pete surpassed Straw on June 23. Even allowing for Darryl not debuting until May 6 of his rookie year, that represented an awfully quick revision.

Ditto for the team record for home runs by rookies, veterans and everybody in between. Pete blasted his 42nd home run on August 27. That left him more than a month to run up the score on Hundley, Beltran and history. Pete proceeded to use September to generate a lifetime’s worth of dust in which to leave the old mark of 41.

The difference between Alonso’s Mets record of 53 home runs and the version that preceded his isn’t the sole reason he is our Ashburn of the moment, but it illustrates just what a difference maker he was. A difference of 12 home runs between the all-time team standard and the second-highest total, even in a vacuum, is enormous. Mets fans had devoted themselves for fifty-seven years to a cause whose power was more spiritual than actual. Power pitchers we had. Power hitters we graded on a curve. Through 2018, our single-season record was the second-most modest in all of baseball. That figured. We were gobsmacked when Kingman eclipsed Thomas when he got to 35. We were thrilled when Hundley reached and nosed past 40. The first climb took thirteen years, the second required another twenty-one, and nobody took a higher step for the next twenty-two. We resisted the temptation to hold our breath that anybody would ever top Todd. We were conditioned by experience to not peer particularly high.

Alonso changed all that. He gave us a telescope and taught us how to navigate the stars, Ursa Major (“the great bear”) the brightest among them.

What Pete did surely wasn’t accomplished in a vacuum. Inside a year’s time, with zero major league credentials established in advance of Opening Day, Pete asserted himself as the visage of the franchise before anybody had a chance to fret over service time concerns. As a rookie, he made himself the focal point of New York National League baseball. He did it by force of a mighty swing and a mightier personality. He did it naturally. In a sport where youngsters are traditionally instructed to know your place, rook, Alonso saw his place as front and center on a team striving to rise above low expectations and shake free of stubborn mediocrity.

Pete staked out his place and pace early and often. Nine homers in April. Ten more in May. Twenty-eight before the Fourth of July. Almost every one of them stirred the skies. It’s hard to say what was more fun: counting them or watching them. Before the second half kicked in, we were assured we wouldn’t waste our summer prayin’ in vain for a savior to rise from these streets.

By midseason, there was no question the Polar Bear was The Man in Queens. He took his burgeoning reputation to Cleveland for the Home Run Derby in July and increased it exponentially. The 57 home runs he blasted out of Progressive Field may not have counted toward his 162-game total, but geez they made an impression. Winning the Derby in a Mets uniform presented us with a gratifying exhibition achievement. Immediately announcing he’d be donating a significant portion of his million-dollar winnings to the Wounded Warrior Project and the Tunnel to Towers Foundation confirmed we had somebody special swinging for the fences.

Alonso was the head-to-toe package. Especially the toes, as we learned from the story of the special shoes he commissioned for him and his teammates to wear on September 11. It was a brilliantly conceived heartfelt tribute to the first responders who gave their lives eighteen years earlier, to their families who go on without them, “to all the ordinary people who felt a sense of urgency and an admirable call of duty. It’s for all the people that lost their lives and all the people that did so much to help.”

Pete was 24 when he expressed those sentiments after the game with the shoes, a game when MLB, in its infinite wisdom, forbade the Mets from wearing the first-responder caps they wore in observance of a terrible municipal loss from 2001 through 2007. Pete, a six-year-old on 9/11/01 but by no means born yesterday, knew how the Torreadors over on Park Avenue could be about enforcing pointless regulations, so he strategized a workaround, got every one of his teammates on board and paid for a roster’s worth of footwear.

And he’s still 24.

The 24-year-old says thoughtful things, introspective things, hilarious things and pithy things. The briefest of his remarks, articulated in July, as the Mets were finding their competitive footing, was simply “LFGM.” We all capeeshed. LFGM became a hashtag, a rallying cry and the backbeat to a playoff chase surge almost nobody anticipated. Nobody but Pete and his co-workers, perhaps. Directly preceding his four-letter declaration of contention, Pete spelled it out in a tweet:

“Our goal is to make history. We strive every day to be great and nothing less.”

The 2019 Mets flirted with something historic, at one point pulling down fifteen wins in sixteen games and fleetingly turning Citi Field into a summer festival. From wallowing eleven games under to reveling ten games over, they didn’t get quite where wanted them to be, but Pete and his pals took us a lot closer than we dared hope. Before the team got going, Alonso’s rendezvous with destiny had already come into focus. He kept it going and going.

26…27…28…

40…41…42…

50…51…52…all the way to 53.

Now, we are delighted to believe, all the way to next year.

A difference maker in so many ways. A freshmaker in a Mentos kind of way. As valuable as we could have imagined had our imaginations spanned as broad as a Polar Bear’s back, something we got a good look at thanks to those shirt-ripping walkoff celebrations he somehow thought to initiate when he wasn’t thinking up and doing everything else.

Our MVM. Our Em-Vee-Pete.

FAITH AND FEAR’S PREVIOUS RICHIE ASHBURN MOST VALUABLE METS

2005: Pedro Martinez

2006: Carlos Beltran

2007: David Wright

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Pedro Feliciano

2010: R.A. Dickey

2011: Jose Reyes

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Daniel Murphy, Dillon Gee and LaTroy Hawkins

2014: Jacob deGrom

2015: Yoenis Cespedes

2016: Asdrubal Cabrera

2017: Jacob deGrom

2018: Jacob deGrom

Still to come: The Nikon Camera Player of the Year for 2019.

by Greg Prince on 1 November 2019 4:13 pm It’s early 2005 at something nobody’s ever heard of called Faith and Fear in Flushing. We’re blogging for the first time. We have Carlos Beltran coming to camp for the first time. We have the Washington Nationals coming to the National League East for the first time. Beltran was just an Astro. The Nationals were just the Expos. We were just e-mailing each other. Now we’re all starting new adventures.

Faith and Fear watches Carlos Beltran awkwardly approach a leadership role on his brand new team. He’s not an obvious fit as he gets himself acclimated to a new team, a new city, a new situation. The Washington Nationals, meanwhile, morph from their previous identity. They’re pretty good at first, then reverse course and descend into dreadful for several years that coincide with the establishment of a comfort zone for Beltran. He settles in. He hits. He hits with power. He runs. He fields. He throws. That’s the part we see with our own eyes. Whatever he does in the way of leading the team we can only imagine.

Carlos Beltran gets hurt and, as a result, the Mets aren’t very good. The Washington Nationals remain the one team in the NL East that’s worse, but things are about to change. They draft well. They cultivate talent. By the time Beltran heals and leaves, the Nats become good. Good enough to loathe. Not good enough to win it all, but certainly good enough to compete.

Beltran continues to excel as he ages. Wherever he goes, his team benefits. The Nationals stop and start. In 2015, it is the Mets who stop them. In 2016, it is a former Met teammate of Beltran’s, Daniel Murphy, who starts them up. We loathe them some more. Murph can’t lift the Nats all the way, though. Neither can Bryce Harper. Neither can Stephen Strasburg. Neither can anybody for what seems the longest time.

Carlos returns to Houston for one final go-round. He’s not an everyday superstar anymore, but he’s still got skills. He’s definitely a leader. Everybody’s sworn to it since he left the Mets. In 2017, on an Astros club said to be missing only a dash of veteran wisdom to complete its calculated journey from the bottom to the top, it is Beltran who everybody looks up to. With the twenty-year vet mostly sitting on the bench but definitely a factor in the clubhouse, the Houston Astros become world champions.

Two years later, the Astros are in the World Series again. Their opponent is the Washington Nationals. No more Murph. No more Bryce. But Strasburg’s around. And Ryan Zimmerman, who was a National in the first season there were Nationals, has never left. Max Scherzer and Howie Kendrick, two wizened Nats, date their major league service to the previous decade. Scherzer pitched at Shea Stadium on June 11, 2008, in a game where Mike Pelfrey shut out the Arizona Diamondbacks into the ninth inning. The game got away when Willie Randolph took out Pelfrey in favor of Billy Wagner. In extras, the Mets won when Carlos Beltran homered. Five nights later, Pelfrey defeated the Angels in Anaheim. It was Randolph’s last game as Mets manager. His first was Beltran’s first. In the lineup on June 16, 2008, for the home team, batting seventh and playing second, was Kendrick.

It had been a while overall for Zimmerman; for Scherzer; for Kendrick; for Strasburg (he debuted in 2010 to a torrent of hype, yet was informed in 2013 he was not as good as Matt Harvey); for Davey Martinez, the Nationals manager. In his first year as a player, 1986, Martinez pinch-ran for the Cubs in the ninth inning on September 17 at Shea. A couple of outs later, the Mets clinched their most convincing division title. Fifteen years later, Martinez was a Brave, playing in what we’d remember as the second Brian Jordan Game, a game the Mets lost in horrifying fashion as they groped for an unlikely playoff berth. We’d remember it too much in 2019 when the Mets played another Brian Jordan Game in another futile grope. Jordan wasn’t involved this time. Martinez was. He was the Washington Nationals manager.

That was in early September. The 2019 Mets fell away from contention. The 2019 Nats pushed on. Into the Wild Card Game. Into the NLDS. Wondrously into the NLCS — wondrously because they’d never advanced beyond the NLDS as the Nationals. It had become an unwanted signature of their franchise, finally erased on their fifth try. Then they put the NLCS behind them with ease, and for the time, whether as Expos or Nats, they were in the World Series. The Astros had 107 regular-season wins, which earned them home field advantage, which earned them nothing. Six games were split, each in favor of the visitors. The seventh game was in Houston. The Nationals, behind Scherzer pitching five gutty innings after neck spasms shelved him three nights before, hung in against the Astros. They hung in until Zack Greinke, who the Mets and Murph had overcome in the 2015 NLDS to advance toward their own NLCS sweep, was removed in favor of Will Harris. Harris faced Kendrick with a runner on in the seventh. Kendrick made the last out for the Dodgers in 2015. In 2019, he hit a go-ahead home run for the Nats.

The Nationals padded their lead and won the seventh game of the World Series, 6-2. The road team prevailed over and over. The Nationals, comprised of old guys, potential free agents and an impossibly young, impossibly good Juan Soto, became the eleventh National League East representative to win a World Series, marking the end of the fifteenth season and postseason of baseball we’ve blogged at Faith and Fear in Flushing.

As we look ahead to 2020 and our sixteenth season of blogging, we learn that the manager of our New York Mets will be Carlos Beltran, long removed from his playing days as a Met, not so long removed from playing in general. He is universally admired within the game, yet taking on a wholly new role. So are the Washington Nationals. They will be first-time defending world champions, charging out of the visitors dugout at Citi Field on March 26, taking on Carlos Beltran’s Mets.

That’ll be Opening Day, when everything old and new traditionally merge into something else altogether.

by Greg Prince on 21 October 2019 4:51 pm While interviews continue to proceed to determine who will collaborate most collegially with non-uniformed front office personnel in the evolving so as to be unrecognizable to the ghost of John McGraw role of field manager, I have a question not for or about Carlos Beltran, Eduardo Perez, Joe Girardi, Tim Bogar or anybody else still considered a candidate to make us completely forget Mickey Callaway, but regarding another recently vacant skippering position:

Why was Edgardo Alfonzo dismissed as manager of the Brooklyn Cyclones?

Word seeped out last week that Fonzie would not be back in Coney Island to follow up on his New York-Penn League championship-guiding performance — and not because he was being groomed for bigger and better things up the Met chain. No official announcement was made, but the reported phrase of explanation, via Mike Puma of the Post, was Brodie Van Wagenen’s regime wanted to fill the role with one of “its own people”.

Fonzie is a Mets icon. He’s our own people. I’m surprised Brodie the GM of the same organization that has long been graced by the presence of Edgardo Alfonzo hasn’t crossed paths with the man.

My instinct is to be disgusted with the Mets the way I was disgusted with the Mets when they didn’t bother keeping Alfonzo a Met player in December of 2002, but I’ve also been straining to see this from the “its own people” angle. Was there some intangible element Fonzie didn’t bring to managing the Cyclones that the BVW crew values? We know he brought the leadership that resulted in a trophy. Was that just a coincidence? I ask that sincerely. Was Fonzie not developing players while he was winning with them? Is there a burgeoning “Met way” of doing things that Fonzie is somehow viewed as incapable of disseminating? I’m not asking that rhetorically. If Van Wagenen is overseeing a restructuring of the minor leagues and has a certain kind of manager in mind that Edgardo Alfonzo definitively isn’t, then maybe I can squint and see how a change was in order.

Shy of the traditional whisper campaign that usually denigrates whichever Met is suddenly an ex-Met, that’s the best answer I can come up with, and it’s not much. It seems ludicrous on the surface and several layers beneath it. Admittedly, I didn’t hang on every pitch of every Cyclones game in 2019, but I also didn’t pick up on any whispering that the Cyclones were winning in spite of Alfonzo, or that Alfonzo was managing virulently against the desired organizational tide. Did he roll his eyes one too many times during an analytical presentation? Did he toss a printout of projected prospect tendencies to the ground and do to it what Lou Brown did to Roger Dorn’s contract in Major League? Has Fonzie ever done anything to piss off anybody?

If another manager who finally brought an undisputed title to the crown jewel of the Met system had been told he wasn’t going to manage for any Met affiliate next season, I honestly might not have noticed. But this is Fonzie. We know Fonzie. We remember him as one of the most diligent players we ever had. He was fundamentals incarnate, a teammate beyond reproach, a quiet leader in a tumultuous, thrilling era of Mets baseball. It was sad when the business of free agency sent him elsewhere. It was heartwarming to have him back in a dugout under the Met umbrella. Then he adds a flourish to the ideal scenario by winning.

That’s not enough to be this organization’s own people?

Fonzie will stick around as a Mets Ambassador, which seems to involve making community-minded appearances; smiling in the vicinity of Mr. Met; and popping out of the shadows to present casino gift certificates to lucky fans who guess “Edgardo Alfonzo” as the answer to between-innings trivia quizzes. I’ll take Fonzie in that Met capacity over no Met capacity. I’d hate to think there’d be a rift that would keep our all-time second baseman (as named on the 40th and 50th Anniversary teams) away from Flushing. It’s always a downer when you see someone you loved as a player viewed as utterly disposable as an instructor. But it seems a waste of a splendid baseball mind to confine Alfonzo to only ceremonial duties. It’s baffling that a champion be told he’s somehow not the cut of an organization’s jib after just having brought that organization tangible splendor.

He’s Fonzie. C’mon. What gives?

by Greg Prince on 20 October 2019 1:40 pm We don’t cheer the sun coming up. We don’t cheer the grass coming in green. Yet we always cheer the Yankees going away. It’s heartening to know we can still appreciate the given things.

What’s that you say? It wasn’t a given that New York’s junior circuit entry would go away for good in 2019, especially when on Saturday night the sixth game of the American League Championship Series got itself tied in the top of the ninth inning and Game Seven loomed as a genuine possibility? Perhaps. It is baseball, and we are fond of reminding one another that in baseball, especially in baseball’s postseason, anything can happen — especially in a Game Seven and pivotally in a Game Six. What happened in the top of the ninth of Game Six was DJ Lamahieu poking a two-run homer just over the right field fence at Minute Maid Park and knotting the Astros at four, briefly casting into doubt the outcome of who would represent the AL in the World Series and disturbing the ultimate autumnal tranquility we have known and cherished since the unrequested ruckus of November 2009.

But a World Series in the 2010s by definition is a set of baseball games that never includes the New York Yankees. Not in any year between 2010 and 2018 and, as we approached the bottom of the ninth in Houston, not 2019. Not yet, anyway.

Not yet at all. Aroldis Chapman, heretofore untouchable fireballing closer, recorded two quick outs to keep Game Six tied, 4-4. Then he walked George Springer, bringing up Jose Altuve. Jose Altuve is not who you want up if you’re rooting for Aroldis Chapman.

Which none of us was, I’m pretty sure. Thus, we were quite content to see the mightiest mite swing and connect with a Chapman pitch that was next seen banging off a wall well above the high yellow home run line in left-center field. All those pinstripe-inflected lists being hastily updated to add Lamahieu to the ranks of Chambliss, Dent and Boone were just as suddenly subject to a quick Ctrl+Z. Instead, you could ink into legend a game-winning, pennant-clinching, Yankee-vanquishing home run. Astros take Game Six, 6-4; the ALCS, 4-2; and our hearts, for sure.

You’d think after ten consecutive Elimination Days — seven of them in October, four on the doorstep of the Fall Classic — that we contemporary denizens of the 2010s would be used to the Yankees going away. Within the parameters of a decade that has contained ten postseasons, it literally happens every year. But that doesn’t make its annual occurrence any less sweet.

Once Springer crossed home plate on Altuve’s blessed blast, Greater New York’s big-time professional sports championship drought reached 2,812 days, dating back to February 5, 2012, when the Giants snatched Super Bowl XLVI from the Patriots (no offense, Cyclones, Ducks and latter-day Cosmos). Daniel Jones’s and Sam Darnold’s respective right arms represent the next conceivable chance for the New York area to break through on any side of the Hudson. By the time we know for sure they haven’t — though anything can happen in any sport — we’ll be up to eight years without a full-blown celebration going off anywhere around here. Time was the Yankees could be counted on to interrupt fallow periods with a gaudy parade. Some New Yorkers got a kick out of that sort of thing. Many didn’t. We’ll take going kickless.

The 2019 ALCS now belongs to history, having taken its place alongside standouts of the genre like the 1980, 2004, 2010, 2012 and 2017 editions. If you’re a Mets fan who remembers living through prior decades, you understand why this is sometimes how we get our kicks. If you’re a Mets fan who came of baseball age in 2010 or later, you’ve probably figured out through life experience why the rest of us particularly cherish these moments of Sheadenfreude, the very specific Teutonic phrase for Mets fans exulting in the misfortune of teams we detest, especially when they and the bulk of their followers are based uncomfortably nearby.

The World Series is best when part of it takes place in Queens (which it did in this decade once). The World Series is next-best when none of it takes place in the Bronx. This World Series, between the Astros and Nationals, will be just fine. They’ve all been no worse than just fine from 2010 forward. May the 2020s be at least that good.

by Greg Prince on 18 October 2019 3:51 pm The best part about the Nationals sweeping the Cardinals in the NLCS, aside from the Cardinals being swept, is it left us plenty of time to get around to extending congratulations to our division rival on advancing to its first World Series. Washington won its first National(s) League pennant on Tuesday night, a week ahead of their next game. It’s Friday afternoon. As self-appointed representative of senior circuit partisans who know first-hand what it means to have rooted our ballclubs clear into the final set of games of a given season, congratulations already yet!

I’m mostly sincere in expressing good tidings down toward the heretofore flag-deprived fans situated within the general environs of the Tidal Basin. Every National League team’s fans, whatever their typical level of engagement and sophistication, should experience being in a World Series once, provided we can’t be in it every year. Once is fine for the Nationals (since we can’t be in it this year). If they promise not to make a perennial habit out of this, we can continue to cobble together something approximating graciousness clear up to Game One of the upcoming Fall Classic. Because the ALCS is still in progress, we might actually need them to maintain their winning ways. May it not come to that.

As the 21st Century dips toward 80% on its remaining battery life, I suppose it’s gone out of fashion to figuratively tip caps and shake hands and all that when the hands belong to those you spend six months absolutely despising. Was it always like this? I don’t think so, at least not instinctively. There have been 21 National League champions to emerge from the National League East since the division was formed in 1969. Five of those champs have been us. It won’t surprise you to know I rooted for us in 1969, 1973, 1986, 2000 and 2015. The five easiest World Series decisions any of us ever made.

In the other sixteen — fifteen prior to 2019 — I can recall sometimes being very pro-NL East delegation, sometimes being virulently opposed. As with most things in life, it’s depended.

NL EAST TEAMS BESIDES THE METS I ROOTED FOR WHOLEHEARTEDLY IN THE WORLD SERIES

The 1971 Pirates. Roberto Clemente sparkling in twilight. Willie Stargell at the height of his powers. Steve Blass before Steve Blass became a synonym for suddenly losing the ability to find the strike zone. An extraordinarily appealing supporting cast fronted by Manny Sanguillen and Al Oliver. Their charisma transcended any sense of rivalry. I was eight. It didn’t bother me that they finished way ahead of the Mets. The 1971 Mets had already been finished way ahead of by the time the 1971 World Series commenced. I wanted the Bucs to finish ahead of the Orioles, an entity I was still mad at from two years before. When they did, I was quite gratified as a baseball fan who keeps watching baseball despite the absence of his team oughta be.

The 1993 Phillies. This was a one-season infatuation, facilitated by the presence of Lenny Dykstra and the general Krukky demeanor of a team that won in a year when the Mets opted to not compete whatsoever in the National League East. Joe Carter’s home run that won it all for Toronto actually kind of broke my October heart. By 1994, I was over the Phillies and have stayed there ever since.

The 1995 Braves. It’s true. I used to really like the Braves. A couple of times. The early ’80s. The early ’90s. What did those eras have in common? At the time, it was the underdog element attached to an outfit that had been nowhere previously — and the fact that Atlanta’s startling 1982 and 1991 rises from ashes took place in the National League West. In 1995, the second year of three-division alignment (and the first with a postseason), I was still afflicted by residual goodwill for a perfectly amenable arrangement that had been only recently legislated out of existence. Finally, I thought when they beat the Tribe in six, the Braves got what they deserved. We certainly didn’t get what we deserved once it sunk in that they were in the NL East to stay.

The 1997 Marlins. God help me, I don’t know why I latched onto these store-bought Fish for their initial October run, but I did. They had the underdog/interloper aura, which I’m often prone to fall for, but the Marlins mostly purchased it at Neiman Marcus (or, given their South Florida locale, maybe Burdines). The owner, as all owners of the Marlins reliably are, was despicable. The fans materialized overnight. Their lineup featured Bobby Bonilla, for crissake. Yet I fell for them, or at least their quest. Expansion team simpatico. National League East solidarity. Jim Leyland getting to light up a victory cigarette. Who knows why one follows a postseason muse? When they took down the again unfortunate Indians in seven, I applauded. Perhaps the sound of my two hands clapping shook loose Al Leiter and Dennis Cook.

The 2003 Marlins. Different vibe six years later. The Marlins were a true out-of-nowhere team. Dontrelle Willis was a lovable kid. So was Miguel Cabrera. Juan Pierre was a frisky throwback. Josh Beckett had the liveliest of arms. Ivan Rodriguez was in the right place at last. Future 2007 Collapse participants Jeff Conine and Luis Castillo were solid contributors. They outwitted the Giants. They shocked the Cubs. And their World Series opponent made them all the more rootable. It’s been a while since anybody could apply such an adjective to any Marlin unit.

NL EAST TEAMS I ROOTED AGAINST IN THE WORLD SERIES BUT IN RETROSPECT SEEM LIKE WORTHY WINNERS